- Privacy Policy

Home » Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Research Design – Types, Methods and Examples

Table of Contents

Research Design

Definition:

Research design refers to the overall strategy or plan for conducting a research study. It outlines the methods and procedures that will be used to collect and analyze data, as well as the goals and objectives of the study. Research design is important because it guides the entire research process and ensures that the study is conducted in a systematic and rigorous manner.

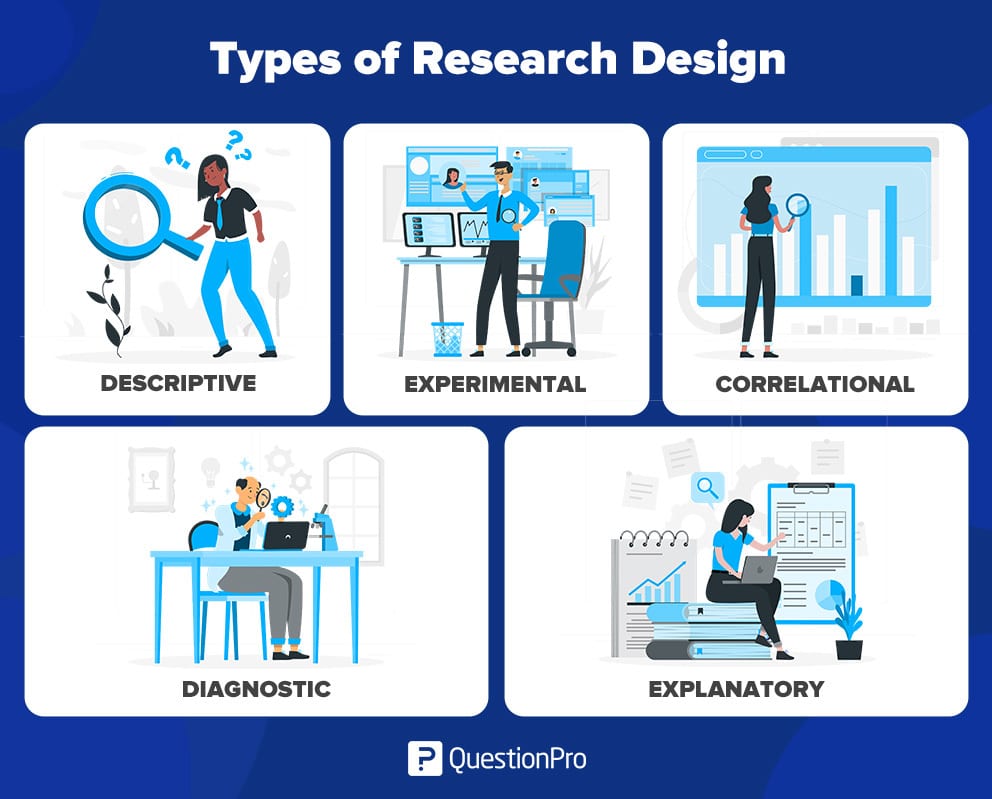

Types of Research Design

Types of Research Design are as follows:

Descriptive Research Design

This type of research design is used to describe a phenomenon or situation. It involves collecting data through surveys, questionnaires, interviews, and observations. The aim of descriptive research is to provide an accurate and detailed portrayal of a particular group, event, or situation. It can be useful in identifying patterns, trends, and relationships in the data.

Correlational Research Design

Correlational research design is used to determine if there is a relationship between two or more variables. This type of research design involves collecting data from participants and analyzing the relationship between the variables using statistical methods. The aim of correlational research is to identify the strength and direction of the relationship between the variables.

Experimental Research Design

Experimental research design is used to investigate cause-and-effect relationships between variables. This type of research design involves manipulating one variable and measuring the effect on another variable. It usually involves randomly assigning participants to groups and manipulating an independent variable to determine its effect on a dependent variable. The aim of experimental research is to establish causality.

Quasi-experimental Research Design

Quasi-experimental research design is similar to experimental research design, but it lacks one or more of the features of a true experiment. For example, there may not be random assignment to groups or a control group. This type of research design is used when it is not feasible or ethical to conduct a true experiment.

Case Study Research Design

Case study research design is used to investigate a single case or a small number of cases in depth. It involves collecting data through various methods, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis. The aim of case study research is to provide an in-depth understanding of a particular case or situation.

Longitudinal Research Design

Longitudinal research design is used to study changes in a particular phenomenon over time. It involves collecting data at multiple time points and analyzing the changes that occur. The aim of longitudinal research is to provide insights into the development, growth, or decline of a particular phenomenon over time.

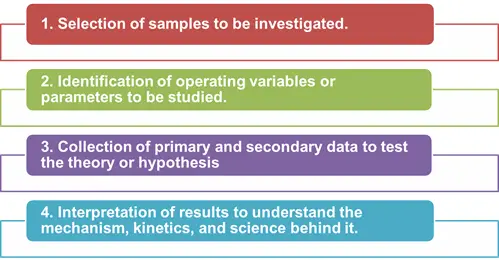

Structure of Research Design

The format of a research design typically includes the following sections:

- Introduction : This section provides an overview of the research problem, the research questions, and the importance of the study. It also includes a brief literature review that summarizes previous research on the topic and identifies gaps in the existing knowledge.

- Research Questions or Hypotheses: This section identifies the specific research questions or hypotheses that the study will address. These questions should be clear, specific, and testable.

- Research Methods : This section describes the methods that will be used to collect and analyze data. It includes details about the study design, the sampling strategy, the data collection instruments, and the data analysis techniques.

- Data Collection: This section describes how the data will be collected, including the sample size, data collection procedures, and any ethical considerations.

- Data Analysis: This section describes how the data will be analyzed, including the statistical techniques that will be used to test the research questions or hypotheses.

- Results : This section presents the findings of the study, including descriptive statistics and statistical tests.

- Discussion and Conclusion : This section summarizes the key findings of the study, interprets the results, and discusses the implications of the findings. It also includes recommendations for future research.

- References : This section lists the sources cited in the research design.

Example of Research Design

An Example of Research Design could be:

Research question: Does the use of social media affect the academic performance of high school students?

Research design:

- Research approach : The research approach will be quantitative as it involves collecting numerical data to test the hypothesis.

- Research design : The research design will be a quasi-experimental design, with a pretest-posttest control group design.

- Sample : The sample will be 200 high school students from two schools, with 100 students in the experimental group and 100 students in the control group.

- Data collection : The data will be collected through surveys administered to the students at the beginning and end of the academic year. The surveys will include questions about their social media usage and academic performance.

- Data analysis : The data collected will be analyzed using statistical software. The mean scores of the experimental and control groups will be compared to determine whether there is a significant difference in academic performance between the two groups.

- Limitations : The limitations of the study will be acknowledged, including the fact that social media usage can vary greatly among individuals, and the study only focuses on two schools, which may not be representative of the entire population.

- Ethical considerations: Ethical considerations will be taken into account, such as obtaining informed consent from the participants and ensuring their anonymity and confidentiality.

How to Write Research Design

Writing a research design involves planning and outlining the methodology and approach that will be used to answer a research question or hypothesis. Here are some steps to help you write a research design:

- Define the research question or hypothesis : Before beginning your research design, you should clearly define your research question or hypothesis. This will guide your research design and help you select appropriate methods.

- Select a research design: There are many different research designs to choose from, including experimental, survey, case study, and qualitative designs. Choose a design that best fits your research question and objectives.

- Develop a sampling plan : If your research involves collecting data from a sample, you will need to develop a sampling plan. This should outline how you will select participants and how many participants you will include.

- Define variables: Clearly define the variables you will be measuring or manipulating in your study. This will help ensure that your results are meaningful and relevant to your research question.

- Choose data collection methods : Decide on the data collection methods you will use to gather information. This may include surveys, interviews, observations, experiments, or secondary data sources.

- Create a data analysis plan: Develop a plan for analyzing your data, including the statistical or qualitative techniques you will use.

- Consider ethical concerns : Finally, be sure to consider any ethical concerns related to your research, such as participant confidentiality or potential harm.

When to Write Research Design

Research design should be written before conducting any research study. It is an important planning phase that outlines the research methodology, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques that will be used to investigate a research question or problem. The research design helps to ensure that the research is conducted in a systematic and logical manner, and that the data collected is relevant and reliable.

Ideally, the research design should be developed as early as possible in the research process, before any data is collected. This allows the researcher to carefully consider the research question, identify the most appropriate research methodology, and plan the data collection and analysis procedures in advance. By doing so, the research can be conducted in a more efficient and effective manner, and the results are more likely to be valid and reliable.

Purpose of Research Design

The purpose of research design is to plan and structure a research study in a way that enables the researcher to achieve the desired research goals with accuracy, validity, and reliability. Research design is the blueprint or the framework for conducting a study that outlines the methods, procedures, techniques, and tools for data collection and analysis.

Some of the key purposes of research design include:

- Providing a clear and concise plan of action for the research study.

- Ensuring that the research is conducted ethically and with rigor.

- Maximizing the accuracy and reliability of the research findings.

- Minimizing the possibility of errors, biases, or confounding variables.

- Ensuring that the research is feasible, practical, and cost-effective.

- Determining the appropriate research methodology to answer the research question(s).

- Identifying the sample size, sampling method, and data collection techniques.

- Determining the data analysis method and statistical tests to be used.

- Facilitating the replication of the study by other researchers.

- Enhancing the validity and generalizability of the research findings.

Applications of Research Design

There are numerous applications of research design in various fields, some of which are:

- Social sciences: In fields such as psychology, sociology, and anthropology, research design is used to investigate human behavior and social phenomena. Researchers use various research designs, such as experimental, quasi-experimental, and correlational designs, to study different aspects of social behavior.

- Education : Research design is essential in the field of education to investigate the effectiveness of different teaching methods and learning strategies. Researchers use various designs such as experimental, quasi-experimental, and case study designs to understand how students learn and how to improve teaching practices.

- Health sciences : In the health sciences, research design is used to investigate the causes, prevention, and treatment of diseases. Researchers use various designs, such as randomized controlled trials, cohort studies, and case-control studies, to study different aspects of health and healthcare.

- Business : Research design is used in the field of business to investigate consumer behavior, marketing strategies, and the impact of different business practices. Researchers use various designs, such as survey research, experimental research, and case studies, to study different aspects of the business world.

- Engineering : In the field of engineering, research design is used to investigate the development and implementation of new technologies. Researchers use various designs, such as experimental research and case studies, to study the effectiveness of new technologies and to identify areas for improvement.

Advantages of Research Design

Here are some advantages of research design:

- Systematic and organized approach : A well-designed research plan ensures that the research is conducted in a systematic and organized manner, which makes it easier to manage and analyze the data.

- Clear objectives: The research design helps to clarify the objectives of the study, which makes it easier to identify the variables that need to be measured, and the methods that need to be used to collect and analyze data.

- Minimizes bias: A well-designed research plan minimizes the chances of bias, by ensuring that the data is collected and analyzed objectively, and that the results are not influenced by the researcher’s personal biases or preferences.

- Efficient use of resources: A well-designed research plan helps to ensure that the resources (time, money, and personnel) are used efficiently and effectively, by focusing on the most important variables and methods.

- Replicability: A well-designed research plan makes it easier for other researchers to replicate the study, which enhances the credibility and reliability of the findings.

- Validity: A well-designed research plan helps to ensure that the findings are valid, by ensuring that the methods used to collect and analyze data are appropriate for the research question.

- Generalizability : A well-designed research plan helps to ensure that the findings can be generalized to other populations, settings, or situations, which increases the external validity of the study.

Research Design Vs Research Methodology

| Research Design | Research Methodology |

|---|---|

| The plan and structure for conducting research that outlines the procedures to be followed to collect and analyze data. | The set of principles, techniques, and tools used to carry out the research plan and achieve research objectives. |

| Describes the overall approach and strategy used to conduct research, including the type of data to be collected, the sources of data, and the methods for collecting and analyzing data. | Refers to the techniques and methods used to gather, analyze and interpret data, including sampling techniques, data collection methods, and data analysis techniques. |

| Helps to ensure that the research is conducted in a systematic, rigorous, and valid way, so that the results are reliable and can be used to make sound conclusions. | Includes a set of procedures and tools that enable researchers to collect and analyze data in a consistent and valid manner, regardless of the research design used. |

| Common research designs include experimental, quasi-experimental, correlational, and descriptive studies. | Common research methodologies include qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods approaches. |

| Determines the overall structure of the research project and sets the stage for the selection of appropriate research methodologies. | Guides the researcher in selecting the most appropriate research methods based on the research question, research design, and other contextual factors. |

| Helps to ensure that the research project is feasible, relevant, and ethical. | Helps to ensure that the data collected is accurate, valid, and reliable, and that the research findings can be interpreted and generalized to the population of interest. |

About the author

Muhammad Hassan

Researcher, Academic Writer, Web developer

You may also like

Limitations in Research – Types, Examples and...

Significance of the Study – Examples and Writing...

What is a Hypothesis – Types, Examples and...

Dissertation vs Thesis – Key Differences

APA Research Paper Format – Example, Sample and...

APA Table of Contents – Format and Example

Leave a comment x.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Research Design 101

Everything You Need To Get Started (With Examples)

By: Derek Jansen (MBA) | Reviewers: Eunice Rautenbach (DTech) & Kerryn Warren (PhD) | April 2023

Navigating the world of research can be daunting, especially if you’re a first-time researcher. One concept you’re bound to run into fairly early in your research journey is that of “ research design ”. Here, we’ll guide you through the basics using practical examples , so that you can approach your research with confidence.

Overview: Research Design 101

What is research design.

- Research design types for quantitative studies

- Video explainer : quantitative research design

- Research design types for qualitative studies

- Video explainer : qualitative research design

- How to choose a research design

- Key takeaways

Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project , from its conception to the final data analysis. A good research design serves as the blueprint for how you, as the researcher, will collect and analyse data while ensuring consistency, reliability and validity throughout your study.

Understanding different types of research designs is essential as helps ensure that your approach is suitable given your research aims, objectives and questions , as well as the resources you have available to you. Without a clear big-picture view of how you’ll design your research, you run the risk of potentially making misaligned choices in terms of your methodology – especially your sampling , data collection and data analysis decisions.

The problem with defining research design…

One of the reasons students struggle with a clear definition of research design is because the term is used very loosely across the internet, and even within academia.

Some sources claim that the three research design types are qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods , which isn’t quite accurate (these just refer to the type of data that you’ll collect and analyse). Other sources state that research design refers to the sum of all your design choices, suggesting it’s more like a research methodology . Others run off on other less common tangents. No wonder there’s confusion!

In this article, we’ll clear up the confusion. We’ll explain the most common research design types for both qualitative and quantitative research projects, whether that is for a full dissertation or thesis, or a smaller research paper or article.

Research Design: Quantitative Studies

Quantitative research involves collecting and analysing data in a numerical form. Broadly speaking, there are four types of quantitative research designs: descriptive , correlational , experimental , and quasi-experimental .

Descriptive Research Design

As the name suggests, descriptive research design focuses on describing existing conditions, behaviours, or characteristics by systematically gathering information without manipulating any variables. In other words, there is no intervention on the researcher’s part – only data collection.

For example, if you’re studying smartphone addiction among adolescents in your community, you could deploy a survey to a sample of teens asking them to rate their agreement with certain statements that relate to smartphone addiction. The collected data would then provide insight regarding how widespread the issue may be – in other words, it would describe the situation.

The key defining attribute of this type of research design is that it purely describes the situation . In other words, descriptive research design does not explore potential relationships between different variables or the causes that may underlie those relationships. Therefore, descriptive research is useful for generating insight into a research problem by describing its characteristics . By doing so, it can provide valuable insights and is often used as a precursor to other research design types.

Correlational Research Design

Correlational design is a popular choice for researchers aiming to identify and measure the relationship between two or more variables without manipulating them . In other words, this type of research design is useful when you want to know whether a change in one thing tends to be accompanied by a change in another thing.

For example, if you wanted to explore the relationship between exercise frequency and overall health, you could use a correlational design to help you achieve this. In this case, you might gather data on participants’ exercise habits, as well as records of their health indicators like blood pressure, heart rate, or body mass index. Thereafter, you’d use a statistical test to assess whether there’s a relationship between the two variables (exercise frequency and health).

As you can see, correlational research design is useful when you want to explore potential relationships between variables that cannot be manipulated or controlled for ethical, practical, or logistical reasons. It is particularly helpful in terms of developing predictions , and given that it doesn’t involve the manipulation of variables, it can be implemented at a large scale more easily than experimental designs (which will look at next).

That said, it’s important to keep in mind that correlational research design has limitations – most notably that it cannot be used to establish causality . In other words, correlation does not equal causation . To establish causality, you’ll need to move into the realm of experimental design, coming up next…

Need a helping hand?

Experimental Research Design

Experimental research design is used to determine if there is a causal relationship between two or more variables . With this type of research design, you, as the researcher, manipulate one variable (the independent variable) while controlling others (dependent variables). Doing so allows you to observe the effect of the former on the latter and draw conclusions about potential causality.

For example, if you wanted to measure if/how different types of fertiliser affect plant growth, you could set up several groups of plants, with each group receiving a different type of fertiliser, as well as one with no fertiliser at all. You could then measure how much each plant group grew (on average) over time and compare the results from the different groups to see which fertiliser was most effective.

Overall, experimental research design provides researchers with a powerful way to identify and measure causal relationships (and the direction of causality) between variables. However, developing a rigorous experimental design can be challenging as it’s not always easy to control all the variables in a study. This often results in smaller sample sizes , which can reduce the statistical power and generalisability of the results.

Moreover, experimental research design requires random assignment . This means that the researcher needs to assign participants to different groups or conditions in a way that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to any group (note that this is not the same as random sampling ). Doing so helps reduce the potential for bias and confounding variables . This need for random assignment can lead to ethics-related issues . For example, withholding a potentially beneficial medical treatment from a control group may be considered unethical in certain situations.

Quasi-Experimental Research Design

Quasi-experimental research design is used when the research aims involve identifying causal relations , but one cannot (or doesn’t want to) randomly assign participants to different groups (for practical or ethical reasons). Instead, with a quasi-experimental research design, the researcher relies on existing groups or pre-existing conditions to form groups for comparison.

For example, if you were studying the effects of a new teaching method on student achievement in a particular school district, you may be unable to randomly assign students to either group and instead have to choose classes or schools that already use different teaching methods. This way, you still achieve separate groups, without having to assign participants to specific groups yourself.

Naturally, quasi-experimental research designs have limitations when compared to experimental designs. Given that participant assignment is not random, it’s more difficult to confidently establish causality between variables, and, as a researcher, you have less control over other variables that may impact findings.

All that said, quasi-experimental designs can still be valuable in research contexts where random assignment is not possible and can often be undertaken on a much larger scale than experimental research, thus increasing the statistical power of the results. What’s important is that you, as the researcher, understand the limitations of the design and conduct your quasi-experiment as rigorously as possible, paying careful attention to any potential confounding variables .

Research Design: Qualitative Studies

There are many different research design types when it comes to qualitative studies, but here we’ll narrow our focus to explore the “Big 4”. Specifically, we’ll look at phenomenological design, grounded theory design, ethnographic design, and case study design.

Phenomenological Research Design

Phenomenological design involves exploring the meaning of lived experiences and how they are perceived by individuals. This type of research design seeks to understand people’s perspectives , emotions, and behaviours in specific situations. Here, the aim for researchers is to uncover the essence of human experience without making any assumptions or imposing preconceived ideas on their subjects.

For example, you could adopt a phenomenological design to study why cancer survivors have such varied perceptions of their lives after overcoming their disease. This could be achieved by interviewing survivors and then analysing the data using a qualitative analysis method such as thematic analysis to identify commonalities and differences.

Phenomenological research design typically involves in-depth interviews or open-ended questionnaires to collect rich, detailed data about participants’ subjective experiences. This richness is one of the key strengths of phenomenological research design but, naturally, it also has limitations. These include potential biases in data collection and interpretation and the lack of generalisability of findings to broader populations.

Grounded Theory Research Design

Grounded theory (also referred to as “GT”) aims to develop theories by continuously and iteratively analysing and comparing data collected from a relatively large number of participants in a study. It takes an inductive (bottom-up) approach, with a focus on letting the data “speak for itself”, without being influenced by preexisting theories or the researcher’s preconceptions.

As an example, let’s assume your research aims involved understanding how people cope with chronic pain from a specific medical condition, with a view to developing a theory around this. In this case, grounded theory design would allow you to explore this concept thoroughly without preconceptions about what coping mechanisms might exist. You may find that some patients prefer cognitive-behavioural therapy (CBT) while others prefer to rely on herbal remedies. Based on multiple, iterative rounds of analysis, you could then develop a theory in this regard, derived directly from the data (as opposed to other preexisting theories and models).

Grounded theory typically involves collecting data through interviews or observations and then analysing it to identify patterns and themes that emerge from the data. These emerging ideas are then validated by collecting more data until a saturation point is reached (i.e., no new information can be squeezed from the data). From that base, a theory can then be developed .

As you can see, grounded theory is ideally suited to studies where the research aims involve theory generation , especially in under-researched areas. Keep in mind though that this type of research design can be quite time-intensive , given the need for multiple rounds of data collection and analysis.

Ethnographic Research Design

Ethnographic design involves observing and studying a culture-sharing group of people in their natural setting to gain insight into their behaviours, beliefs, and values. The focus here is on observing participants in their natural environment (as opposed to a controlled environment). This typically involves the researcher spending an extended period of time with the participants in their environment, carefully observing and taking field notes .

All of this is not to say that ethnographic research design relies purely on observation. On the contrary, this design typically also involves in-depth interviews to explore participants’ views, beliefs, etc. However, unobtrusive observation is a core component of the ethnographic approach.

As an example, an ethnographer may study how different communities celebrate traditional festivals or how individuals from different generations interact with technology differently. This may involve a lengthy period of observation, combined with in-depth interviews to further explore specific areas of interest that emerge as a result of the observations that the researcher has made.

As you can probably imagine, ethnographic research design has the ability to provide rich, contextually embedded insights into the socio-cultural dynamics of human behaviour within a natural, uncontrived setting. Naturally, however, it does come with its own set of challenges, including researcher bias (since the researcher can become quite immersed in the group), participant confidentiality and, predictably, ethical complexities . All of these need to be carefully managed if you choose to adopt this type of research design.

Case Study Design

With case study research design, you, as the researcher, investigate a single individual (or a single group of individuals) to gain an in-depth understanding of their experiences, behaviours or outcomes. Unlike other research designs that are aimed at larger sample sizes, case studies offer a deep dive into the specific circumstances surrounding a person, group of people, event or phenomenon, generally within a bounded setting or context .

As an example, a case study design could be used to explore the factors influencing the success of a specific small business. This would involve diving deeply into the organisation to explore and understand what makes it tick – from marketing to HR to finance. In terms of data collection, this could include interviews with staff and management, review of policy documents and financial statements, surveying customers, etc.

While the above example is focused squarely on one organisation, it’s worth noting that case study research designs can have different variation s, including single-case, multiple-case and longitudinal designs. As you can see in the example, a single-case design involves intensely examining a single entity to understand its unique characteristics and complexities. Conversely, in a multiple-case design , multiple cases are compared and contrasted to identify patterns and commonalities. Lastly, in a longitudinal case design , a single case or multiple cases are studied over an extended period of time to understand how factors develop over time.

As you can see, a case study research design is particularly useful where a deep and contextualised understanding of a specific phenomenon or issue is desired. However, this strength is also its weakness. In other words, you can’t generalise the findings from a case study to the broader population. So, keep this in mind if you’re considering going the case study route.

How To Choose A Research Design

Having worked through all of these potential research designs, you’d be forgiven for feeling a little overwhelmed and wondering, “ But how do I decide which research design to use? ”. While we could write an entire post covering that alone, here are a few factors to consider that will help you choose a suitable research design for your study.

Data type: The first determining factor is naturally the type of data you plan to be collecting – i.e., qualitative or quantitative. This may sound obvious, but we have to be clear about this – don’t try to use a quantitative research design on qualitative data (or vice versa)!

Research aim(s) and question(s): As with all methodological decisions, your research aim and research questions will heavily influence your research design. For example, if your research aims involve developing a theory from qualitative data, grounded theory would be a strong option. Similarly, if your research aims involve identifying and measuring relationships between variables, one of the experimental designs would likely be a better option.

Time: It’s essential that you consider any time constraints you have, as this will impact the type of research design you can choose. For example, if you’ve only got a month to complete your project, a lengthy design such as ethnography wouldn’t be a good fit.

Resources: Take into account the resources realistically available to you, as these need to factor into your research design choice. For example, if you require highly specialised lab equipment to execute an experimental design, you need to be sure that you’ll have access to that before you make a decision.

Keep in mind that when it comes to research, it’s important to manage your risks and play as conservatively as possible. If your entire project relies on you achieving a huge sample, having access to niche equipment or holding interviews with very difficult-to-reach participants, you’re creating risks that could kill your project. So, be sure to think through your choices carefully and make sure that you have backup plans for any existential risks. Remember that a relatively simple methodology executed well generally will typically earn better marks than a highly-complex methodology executed poorly.

Recap: Key Takeaways

We’ve covered a lot of ground here. Let’s recap by looking at the key takeaways:

- Research design refers to the overall plan, structure or strategy that guides a research project, from its conception to the final analysis of data.

- Research designs for quantitative studies include descriptive , correlational , experimental and quasi-experimenta l designs.

- Research designs for qualitative studies include phenomenological , grounded theory , ethnographic and case study designs.

- When choosing a research design, you need to consider a variety of factors, including the type of data you’ll be working with, your research aims and questions, your time and the resources available to you.

If you need a helping hand with your research design (or any other aspect of your research), check out our private coaching services .

Psst... there’s more!

This post was based on one of our popular Research Bootcamps . If you're working on a research project, you'll definitely want to check this out ...

11 Comments

Is there any blog article explaining more on Case study research design? Is there a Case study write-up template? Thank you.

Thanks this was quite valuable to clarify such an important concept.

Thanks for this simplified explanations. it is quite very helpful.

This was really helpful. thanks

Thank you for your explanation. I think case study research design and the use of secondary data in researches needs to be talked about more in your videos and articles because there a lot of case studies research design tailored projects out there.

Please is there any template for a case study research design whose data type is a secondary data on your repository?

This post is very clear, comprehensive and has been very helpful to me. It has cleared the confusion I had in regard to research design and methodology.

This post is helpful, easy to understand, and deconstructs what a research design is. Thanks

This post is really helpful.

how to cite this page

Thank you very much for the post. It is wonderful and has cleared many worries in my mind regarding research designs. I really appreciate .

how can I put this blog as my reference(APA style) in bibliography part?

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research Research Tools and Apps

Research Design: What it is, Elements & Types

Can you imagine doing research without a plan? Probably not. When we discuss a strategy to collect, study, and evaluate data, we talk about research design. This design addresses problems and creates a consistent and logical model for data analysis. Let’s learn more about it.

What is Research Design?

Research design is the framework of research methods and techniques chosen by a researcher to conduct a study. The design allows researchers to sharpen the research methods suitable for the subject matter and set up their studies for success.

Creating a research topic explains the type of research (experimental, survey research , correlational , semi-experimental, review) and its sub-type (experimental design, research problem , descriptive case-study).

There are three main types of designs for research:

- Data collection

- Measurement

- Data Analysis

The research problem an organization faces will determine the design, not vice-versa. The design phase of a study determines which tools to use and how they are used.

The Process of Research Design

The research design process is a systematic and structured approach to conducting research. The process is essential to ensure that the study is valid, reliable, and produces meaningful results.

- Consider your aims and approaches: Determine the research questions and objectives, and identify the theoretical framework and methodology for the study.

- Choose a type of Research Design: Select the appropriate research design, such as experimental, correlational, survey, case study, or ethnographic, based on the research questions and objectives.

- Identify your population and sampling method: Determine the target population and sample size, and choose the sampling method, such as random , stratified random sampling , or convenience sampling.

- Choose your data collection methods: Decide on the data collection methods , such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments, and select the appropriate instruments or tools for collecting data.

- Plan your data collection procedures: Develop a plan for data collection, including the timeframe, location, and personnel involved, and ensure ethical considerations.

- Decide on your data analysis strategies: Select the appropriate data analysis techniques, such as statistical analysis , content analysis, or discourse analysis, and plan how to interpret the results.

The process of research design is a critical step in conducting research. By following the steps of research design, researchers can ensure that their study is well-planned, ethical, and rigorous.

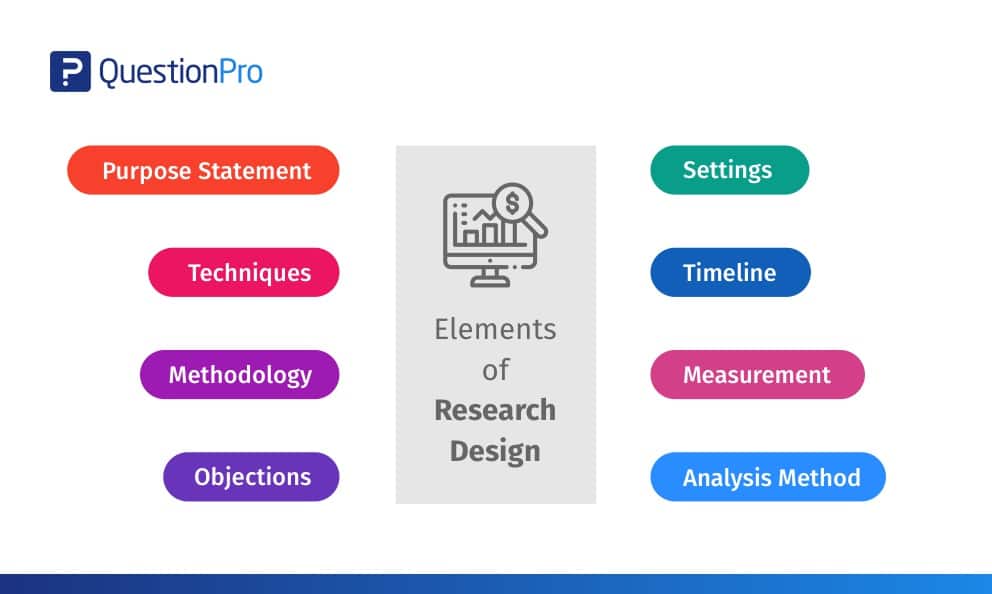

Research Design Elements

Impactful research usually creates a minimum bias in data and increases trust in the accuracy of collected data. A design that produces the slightest margin of error in experimental research is generally considered the desired outcome. The essential elements are:

- Accurate purpose statement

- Techniques to be implemented for collecting and analyzing research

- The method applied for analyzing collected details

- Type of research methodology

- Probable objections to research

- Settings for the research study

- Measurement of analysis

Characteristics of Research Design

A proper design sets your study up for success. Successful research studies provide insights that are accurate and unbiased. You’ll need to create a survey that meets all of the main characteristics of a design. There are four key characteristics:

- Neutrality: When you set up your study, you may have to make assumptions about the data you expect to collect. The results projected in the research should be free from research bias and neutral. Understand opinions about the final evaluated scores and conclusions from multiple individuals and consider those who agree with the results.

- Reliability: With regularly conducted research, the researcher expects similar results every time. You’ll only be able to reach the desired results if your design is reliable. Your plan should indicate how to form research questions to ensure the standard of results.

- Validity: There are multiple measuring tools available. However, the only correct measuring tools are those which help a researcher in gauging results according to the objective of the research. The questionnaire developed from this design will then be valid.

- Generalization: The outcome of your design should apply to a population and not just a restricted sample . A generalized method implies that your survey can be conducted on any part of a population with similar accuracy.

The above factors affect how respondents answer the research questions, so they should balance all the above characteristics in a good design. If you want, you can also learn about Selection Bias through our blog.

Research Design Types

A researcher must clearly understand the various types to select which model to implement for a study. Like the research itself, the design of your analysis can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative.

Qualitative research

Qualitative research determines relationships between collected data and observations based on mathematical calculations. Statistical methods can prove or disprove theories related to a naturally existing phenomenon. Researchers rely on qualitative observation research methods that conclude “why” a particular theory exists and “what” respondents have to say about it.

Quantitative research

Quantitative research is for cases where statistical conclusions to collect actionable insights are essential. Numbers provide a better perspective for making critical business decisions. Quantitative research methods are necessary for the growth of any organization. Insights drawn from complex numerical data and analysis prove to be highly effective when making decisions about the business’s future.

Qualitative Research vs Quantitative Research

Here is a chart that highlights the major differences between qualitative and quantitative research:

| Qualitative Research | Quantitative Research |

|---|---|

| Focus on explaining and understanding experiences and perspectives. | Focus on quantifying and measuring phenomena. |

| Use of non-numerical data, such as words, images, and observations. | Use of numerical data, such as statistics and surveys. |

| Usually uses small sample sizes. | Usually uses larger sample sizes. |

| Typically emphasizes in-depth exploration and interpretation. | Typically emphasizes precision and objectivity. |

| Data analysis involves interpretation and narrative analysis. | Data analysis involves statistical analysis and hypothesis testing. |

| Results are presented descriptively. | Results are presented numerically and statistically. |

In summary or analysis , the step of qualitative research is more exploratory and focuses on understanding the subjective experiences of individuals, while quantitative research is more focused on objective data and statistical analysis.

You can further break down the types of research design into five categories:

1. Descriptive: In a descriptive composition, a researcher is solely interested in describing the situation or case under their research study. It is a theory-based design method created by gathering, analyzing, and presenting collected data. This allows a researcher to provide insights into the why and how of research. Descriptive design helps others better understand the need for the research. If the problem statement is not clear, you can conduct exploratory research.

2. Experimental: Experimental research establishes a relationship between the cause and effect of a situation. It is a causal research design where one observes the impact caused by the independent variable on the dependent variable. For example, one monitors the influence of an independent variable such as a price on a dependent variable such as customer satisfaction or brand loyalty. It is an efficient research method as it contributes to solving a problem.

The independent variables are manipulated to monitor the change it has on the dependent variable. Social sciences often use it to observe human behavior by analyzing two groups. Researchers can have participants change their actions and study how the people around them react to understand social psychology better.

3. Correlational research: Correlational research is a non-experimental research technique. It helps researchers establish a relationship between two closely connected variables. There is no assumption while evaluating a relationship between two other variables, and statistical analysis techniques calculate the relationship between them. This type of research requires two different groups.

A correlation coefficient determines the correlation between two variables whose values range between -1 and +1. If the correlation coefficient is towards +1, it indicates a positive relationship between the variables, and -1 means a negative relationship between the two variables.

4. Diagnostic research: In diagnostic design, the researcher is looking to evaluate the underlying cause of a specific topic or phenomenon. This method helps one learn more about the factors that create troublesome situations.

This design has three parts of the research:

- Inception of the issue

- Diagnosis of the issue

- Solution for the issue

5. Explanatory research : Explanatory design uses a researcher’s ideas and thoughts on a subject to further explore their theories. The study explains unexplored aspects of a subject and details the research questions’ what, how, and why.

Benefits of Research Design

There are several benefits of having a well-designed research plan. Including:

- Clarity of research objectives: Research design provides a clear understanding of the research objectives and the desired outcomes.

- Increased validity and reliability: To ensure the validity and reliability of results, research design help to minimize the risk of bias and helps to control extraneous variables.

- Improved data collection: Research design helps to ensure that the proper data is collected and data is collected systematically and consistently.

- Better data analysis: Research design helps ensure that the collected data can be analyzed effectively, providing meaningful insights and conclusions.

- Improved communication: A well-designed research helps ensure the results are clean and influential within the research team and external stakeholders.

- Efficient use of resources: reducing the risk of waste and maximizing the impact of the research, research design helps to ensure that resources are used efficiently.

A well-designed research plan is essential for successful research, providing clear and meaningful insights and ensuring that resources are practical.

QuestionPro offers a comprehensive solution for researchers looking to conduct research. With its user-friendly interface, robust data collection and analysis tools, and the ability to integrate results from multiple sources, QuestionPro provides a versatile platform for designing and executing research projects.

Our robust suite of research tools provides you with all you need to derive research results. Our online survey platform includes custom point-and-click logic and advanced question types. Uncover the insights that matter the most.

LEARN MORE FREE TRIAL

MORE LIKE THIS

Jotform vs SurveyMonkey: Which Is Best in 2024

Aug 15, 2024

360 Degree Feedback Spider Chart is Back!

Aug 14, 2024

Jotform vs Wufoo: Comparison of Features and Prices

Aug 13, 2024

Product or Service: Which is More Important? — Tuesday CX Thoughts

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Educational resources and simple solutions for your research journey

What is Research Design? Understand Types of Research Design, with Examples

Have you been wondering “ what is research design ?” or “what are some research design examples ?” Are you unsure about the research design elements or which of the different types of research design best suit your study? Don’t worry! In this article, we’ve got you covered!

Table of Contents

What is research design?

Have you been wondering “ what is research design ?” or “what are some research design examples ?” Don’t worry! In this article, we’ve got you covered!

A research design is the plan or framework used to conduct a research study. It involves outlining the overall approach and methods that will be used to collect and analyze data in order to answer research questions or test hypotheses. A well-designed research study should have a clear and well-defined research question, a detailed plan for collecting data, and a method for analyzing and interpreting the results. A well-thought-out research design addresses all these features.

Research design elements

Research design elements include the following:

- Clear purpose: The research question or hypothesis must be clearly defined and focused.

- Sampling: This includes decisions about sample size, sampling method, and criteria for inclusion or exclusion. The approach varies for different research design types .

- Data collection: This research design element involves the process of gathering data or information from the study participants or sources. It includes decisions about what data to collect, how to collect it, and the tools or instruments that will be used.

- Data analysis: All research design types require analysis and interpretation of the data collected. This research design element includes decisions about the statistical tests or methods that will be used to analyze the data, as well as any potential confounding variables or biases that may need to be addressed.

- Type of research methodology: This includes decisions about the overall approach for the study.

- Time frame: An important research design element is the time frame, which includes decisions about the duration of the study, the timeline for data collection and analysis, and follow-up periods.

- Ethical considerations: The research design must include decisions about ethical considerations such as informed consent, confidentiality, and participant protection.

- Resources: A good research design takes into account decisions about the budget, staffing, and other resources needed to carry out the study.

The elements of research design should be carefully planned and executed to ensure the validity and reliability of the study findings. Let’s go deeper into the concepts of research design .

Characteristics of research design

Some basic characteristics of research design are common to different research design types . These characteristics of research design are as follows:

- Neutrality : Right from the study assumptions to setting up the study, a neutral stance must be maintained, free of pre-conceived notions. The researcher’s expectations or beliefs should not color the findings or interpretation of the findings. Accordingly, a good research design should address potential sources of bias and confounding factors to be able to yield unbiased and neutral results.

- Reliability : Reliability is one of the characteristics of research design that refers to consistency in measurement over repeated measures and fewer random errors. A reliable research design must allow for results to be consistent, with few errors due to chance.

- Validity : Validity refers to the minimization of nonrandom (systematic) errors. A good research design must employ measurement tools that ensure validity of the results.

- Generalizability: The outcome of the research design should be applicable to a larger population and not just a small sample . A generalized method means the study can be conducted on any part of a population with similar accuracy.

- Flexibility: A research design should allow for changes to be made to the research plan as needed, based on the data collected and the outcomes of the study

A well-planned research design is critical for conducting a scientifically rigorous study that will generate neutral, reliable, valid, and generalizable results. At the same time, it should allow some level of flexibility.

Different types of research design

A research design is essential to systematically investigate, understand, and interpret phenomena of interest. Let’s look at different types of research design and research design examples .

Broadly, research design types can be divided into qualitative and quantitative research.

Qualitative research is subjective and exploratory. It determines relationships between collected data and observations. It is usually carried out through interviews with open-ended questions, observations that are described in words, etc.

Quantitative research is objective and employs statistical approaches. It establishes the cause-and-effect relationship among variables using different statistical and computational methods. This type of research is usually done using surveys and experiments.

Qualitative research vs. Quantitative research

| Deals with subjective aspects, e.g., experiences, beliefs, perspectives, and concepts. | Measures different types of variables and describes frequencies, averages, correlations, etc. |

| Deals with non-numerical data, such as words, images, and observations. | Tests hypotheses about relationships between variables. Results are presented numerically and statistically. |

| In qualitative research design, data are collected via direct observations, interviews, focus groups, and naturally occurring data. Methods for conducting qualitative research are grounded theory, thematic analysis, and discourse analysis.

| Quantitative research design is empirical. Data collection methods involved are experiments, surveys, and observations expressed in numbers. The research design categories under this are descriptive, experimental, correlational, diagnostic, and explanatory. |

| Data analysis involves interpretation and narrative analysis. | Data analysis involves statistical analysis and hypothesis testing. |

| The reasoning used to synthesize data is inductive.

| The reasoning used to synthesize data is deductive.

|

| Typically used in fields such as sociology, linguistics, and anthropology. | Typically used in fields such as economics, ecology, statistics, and medicine. |

| Example: Focus group discussions with women farmers about climate change perception.

| Example: Testing the effectiveness of a new treatment for insomnia. |

Qualitative research design types and qualitative research design examples

The following will familiarize you with the research design categories in qualitative research:

- Grounded theory: This design is used to investigate research questions that have not previously been studied in depth. Also referred to as exploratory design , it creates sequential guidelines, offers strategies for inquiry, and makes data collection and analysis more efficient in qualitative research.

Example: A researcher wants to study how people adopt a certain app. The researcher collects data through interviews and then analyzes the data to look for patterns. These patterns are used to develop a theory about how people adopt that app.

- Thematic analysis: This design is used to compare the data collected in past research to find similar themes in qualitative research.

Example: A researcher examines an interview transcript to identify common themes, say, topics or patterns emerging repeatedly.

- Discourse analysis : This research design deals with language or social contexts used in data gathering in qualitative research.

Example: Identifying ideological frameworks and viewpoints of writers of a series of policies.

Quantitative research design types and quantitative research design examples

Note the following research design categories in quantitative research:

- Descriptive research design : This quantitative research design is applied where the aim is to identify characteristics, frequencies, trends, and categories. It may not often begin with a hypothesis. The basis of this research type is a description of an identified variable. This research design type describes the “what,” “when,” “where,” or “how” of phenomena (but not the “why”).

Example: A study on the different income levels of people who use nutritional supplements regularly.

- Correlational research design : Correlation reflects the strength and/or direction of the relationship among variables. The direction of a correlation can be positive or negative. Correlational research design helps researchers establish a relationship between two variables without the researcher controlling any of them.

Example : An example of correlational research design could be studying the correlation between time spent watching crime shows and aggressive behavior in teenagers.

- Diagnostic research design : In diagnostic design, the researcher aims to understand the underlying cause of a specific topic or phenomenon (usually an area of improvement) and find the most effective solution. In simpler terms, a researcher seeks an accurate “diagnosis” of a problem and identifies a solution.

Example : A researcher analyzing customer feedback and reviews to identify areas where an app can be improved.

- Explanatory research design : In explanatory research design , a researcher uses their ideas and thoughts on a topic to explore their theories in more depth. This design is used to explore a phenomenon when limited information is available. It can help increase current understanding of unexplored aspects of a subject. It is thus a kind of “starting point” for future research.

Example : Formulating hypotheses to guide future studies on delaying school start times for better mental health in teenagers.

- Causal research design : This can be considered a type of explanatory research. Causal research design seeks to define a cause and effect in its data. The researcher does not use a randomly chosen control group but naturally or pre-existing groupings. Importantly, the researcher does not manipulate the independent variable.

Example : Comparing school dropout levels and possible bullying events.

- Experimental research design : This research design is used to study causal relationships . One or more independent variables are manipulated, and their effect on one or more dependent variables is measured.

Example: Determining the efficacy of a new vaccine plan for influenza.

Benefits of research design

T here are numerous benefits of research design . These are as follows:

- Clear direction: Among the benefits of research design , the main one is providing direction to the research and guiding the choice of clear objectives, which help the researcher to focus on the specific research questions or hypotheses they want to investigate.

- Control: Through a proper research design , researchers can control variables, identify potential confounding factors, and use randomization to minimize bias and increase the reliability of their findings.

- Replication: Research designs provide the opportunity for replication. This helps to confirm the findings of a study and ensures that the results are not due to chance or other factors. Thus, a well-chosen research design also eliminates bias and errors.

- Validity: A research design ensures the validity of the research, i.e., whether the results truly reflect the phenomenon being investigated.

- Reliability: Benefits of research design also include reducing inaccuracies and ensuring the reliability of the research (i.e., consistency of the research results over time, across different samples, and under different conditions).

- Efficiency: A strong research design helps increase the efficiency of the research process. Researchers can use a variety of designs to investigate their research questions, choose the most appropriate research design for their study, and use statistical analysis to make the most of their data. By effectively describing the data necessary for an adequate test of the hypotheses and explaining how such data will be obtained, research design saves a researcher’s time.

Overall, an appropriately chosen and executed research design helps researchers to conduct high-quality research, draw meaningful conclusions, and contribute to the advancement of knowledge in their field.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) on Research Design

Q: What are th e main types of research design?

Broadly speaking there are two basic types of research design –

qualitative and quantitative research. Qualitative research is subjective and exploratory; it determines relationships between collected data and observations. It is usually carried out through interviews with open-ended questions, observations that are described in words, etc. Quantitative research , on the other hand, is more objective and employs statistical approaches. It establishes the cause-and-effect relationship among variables using different statistical and computational methods. This type of research design is usually done using surveys and experiments.

Q: How do I choose the appropriate research design for my study?

Choosing the appropriate research design for your study requires careful consideration of various factors. Start by clarifying your research objectives and the type of data you need to collect. Determine whether your study is exploratory, descriptive, or experimental in nature. Consider the availability of resources, time constraints, and the feasibility of implementing the different research designs. Review existing literature to identify similar studies and their research designs, which can serve as a guide. Ultimately, the chosen research design should align with your research questions, provide the necessary data to answer them, and be feasible given your own specific requirements/constraints.

Q: Can research design be modified during the course of a study?

Yes, research design can be modified during the course of a study based on emerging insights, practical constraints, or unforeseen circumstances. Research is an iterative process and, as new data is collected and analyzed, it may become necessary to adjust or refine the research design. However, any modifications should be made judiciously and with careful consideration of their impact on the study’s integrity and validity. It is advisable to document any changes made to the research design, along with a clear rationale for the modifications, in order to maintain transparency and allow for proper interpretation of the results.

Q: How can I ensure the validity and reliability of my research design?

Validity refers to the accuracy and meaningfulness of your study’s findings, while reliability relates to the consistency and stability of the measurements or observations. To enhance validity, carefully define your research variables, use established measurement scales or protocols, and collect data through appropriate methods. Consider conducting a pilot study to identify and address any potential issues before full implementation. To enhance reliability, use standardized procedures, conduct inter-rater or test-retest reliability checks, and employ appropriate statistical techniques for data analysis. It is also essential to document and report your methodology clearly, allowing for replication and scrutiny by other researchers.

Editage All Access is a subscription-based platform that unifies the best AI tools and services designed to speed up, simplify, and streamline every step of a researcher’s journey. The Editage All Access Pack is a one-of-a-kind subscription that unlocks full access to an AI writing assistant, literature recommender, journal finder, scientific illustration tool, and exclusive discounts on professional publication services from Editage.

Based on 22+ years of experience in academia, Editage All Access empowers researchers to put their best research forward and move closer to success. Explore our top AI Tools pack, AI Tools + Publication Services pack, or Build Your Own Plan. Find everything a researcher needs to succeed, all in one place – Get All Access now starting at just $14 a month !

Related Posts

What are the Best Research Funding Sources

Inductive vs. Deductive Research Approach

What is Research Design? Characteristics, Types, Process, & Examples

Link Copied

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on LinkedIn

Your search has come to an end!

Ever felt like a hamster on a research wheel fast, spinning with a million questions but going nowhere? You've got your topic; you're brimming with curiosity, but... what next? So, forget the research rut and get your papers! This ultimate guide to "what is research design?" will have you navigating your project like a pro, uncovering answers and avoiding dead ends. Know the features of good research design, what you mean by research design, elements of research design, and more.

What is Research Design?

Before starting with the topic, do you know what is research design? Research design is the structure of research methods and techniques selected to conduct a study. It refines the methods suited to the subject and ensures a successful setup. Defining a research topic clarifies the type of research (experimental, survey research, correlational, semi-experimental, review) and its sub-type (experimental design, research problem, descriptive case-study).

There are three main types of designs for research:

1. Data Collection

2. Measurement

3. Data Analysis

Elements of Research Design

Now that you know what is research design, it is important to know the elements and components of research design. Impactful research minimises bias and enhances data accuracy. Designs with minimal error margins are ideal. Key elements include:

1. Accurate purpose statement

2. Techniques for data collection and analysis

3. Methods for data analysis

4. Type of research methodology

5. Probable objections to research

6. Research settings

7. Timeline

8. Measurement of analysis

Got a hang of research, now book yout student accommodation with one click!

Book through amber today!

Characteristics of Research Design

Research design has several key characteristics that contribute to the validity, reliability, and overall success of a research study. To know the answer for what is research design, it is important to know the characteristics. These are-

1. Reliability

A reliable research design ensures that each study’s results are accurate and can be replicated. This means that if the research is conducted again under the same conditions, it should yield similar results.

2. Validity

A valid research design uses appropriate measuring tools to gauge the results according to the research objective. This ensures that the data collected and the conclusions drawn are relevant and accurately reflect the phenomenon being studied.

3. Neutrality

A neutral research design ensures that the assumptions made at the beginning of the research are free from bias. This means that the data collected throughout the research is based on these unbiased assumptions.

4. Generalizability

A good research design draws an outcome that can be applied to a large set of people and is not limited to the sample size or the research group.

Research Design Process

What is research design? A good research helps you do a really good study that gives fair, trustworthy, and useful results. But it's also good to have a bit of wiggle room for changes. If you’re wondering how to conduct a research in just 5 mins , here's a breakdown and examples to work even better.

1. Consider Aims and Approaches

Define the research questions and objectives, and establish the theoretical framework and methodology.

2. Choose a Type of Research Design

Select the suitable research design, such as experimental, correlational, survey, case study, or ethnographic, according to the research questions and objectives.

3. Identify Population and Sampling Method

Determine the target population and sample size, and select the sampling method, like random, stratified random sampling, or convenience sampling.

4. Choose Data Collection Methods

Decide on the data collection methods, such as surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments, and choose the appropriate instruments for data collection.

5. Plan Data Collection Procedures

Create a plan for data collection, detailing the timeframe, location, and personnel involved, while ensuring ethical considerations are met.

6. Decide on Data Analysis Strategies

Select the appropriate data analysis techniques, like statistical analysis, content analysis, or discourse analysis, and plan the interpretation of the results.

What are the Types of Research Design?

A researcher must grasp various types to decide which model to use for a study. There are different research designs that can be broadly classified into quantitative and qualitative.

Qualitative Research

Qualitative research identifies relationships between collected data and observations through mathematical calculations. Statistical methods validate or refute theories about natural phenomena. This research method answers "why" a theory exists and explores respondents' perspectives.

Quantitative Research

Quantitative research is essential when statistical conclusions are needed to gather actionable insights. Numbers provide clarity for critical business decisions. This method is crucial for organizational growth, with insights from complex numerical data guiding future business decisions.

Qualitative Research vs Quantitative Research

While researching, it is important to know the difference between qualitative and quantitative research. Here's a quick difference between the two:

| Aspect | Qualitative Research | Quantitative Research |

|---|---|---|

| Data Type | Non-numerical data such as words, images, and sounds. | Numerical data that can be measured and expressed in numerical terms. |

| Purpose | To understand concepts, thoughts, or experiences. | To test hypotheses, identify patterns, and make predictions. |

| Data Collection | Common methods include interviews with open-ended questions, observations described in words, and literature reviews. | Common methods include surveys with closed-ended questions, experiments, and observations recorded as numbers. |

| Data Analysis | Data is analyzed using grounded theory or thematic analysis. | Data is analyzed using statistical methods. |

| Outcome | Produces rich and detailed descriptions of the phenomenon being studied, and uncovers new insights and meanings. | Produces objective, empirical data that can be measured. |

The research types can be further divided into 5 categories:

1. Descriptive Research

Descriptive research design focuses on detailing a situation or case. It's a theory-driven method that involves gathering, analysing, and presenting data. This approach offers insights into the reasons and mechanisms behind a research subject, enhancing understanding of the research's importance. When the problem statement is unclear, exploratory research can be conducted.

2. Experimental Research

Experimental research design investigates cause-and-effect relationships. It’s a causal design where the impact of an independent variable on a dependent variable is observed. For example, the effect of price on customer satisfaction. This method efficiently addresses problems by manipulating independent variables to see their effect on dependent variables. Often used in social sciences, it involves analysing human behaviour by studying changes in one group's actions and their impact on another group.

3. Correlational Research

Correlational research design is a non-experimental technique that identifies relationships between closely linked variables. It uses statistical analysis to determine these relationships without assumptions. This method requires two different groups. A correlation coefficient between -1 and +1 indicates the strength and direction of the relationship, with +1 showing a positive correlation and -1 a negative correlation.

4. Diagnostic Research

Diagnostic research design aims to identify the underlying causes of specific issues. This method delves into factors creating problematic situations and has three phases:

- Issue inception

- Issue diagnosis

- Issue resolution

5. Explanatory Research

Explanatory research design builds on a researcher’s ideas to explore theories further. It seeks to explain the unexplored aspects of a subject, addressing the what, how, and why of research questions.

Benefits of Research Design

After learning about what is research design and the process, it is important to know the key benefits of a well-structured research design:

1. Minimises Risk of Errors: A good research design minimises the risk of errors and reduces inaccuracy. It ensures that the study is carried out in the right direction and that all the team members are on the same page.

2. Efficient Use of Resources: It facilitates a concrete research plan for the efficient use of time and resources. It helps the researcher better complete all the tasks, even with limited resources.

3. Provides Direction: The purpose of the research design is to enable the researcher to proceed in the right direction without deviating from the tasks. It helps to identify the major and minor tasks of the study.

4. Ensures Validity and Reliability: A well-designed research enhances the validity and reliability of the findings and allows for the replication of studies by other researchers. The main advantage of a good research design is that it provides accuracy, reliability, consistency, and legitimacy to the research.

5. Facilitates Problem-Solving: A researcher can easily frame the objectives of the research work based on the design of experiments (research design). A good research design helps the researcher find the best solution for the research problems.

6. Better Documentation: It helps in better documentation of the various activities while the project work is going on.

That's it! You've explored all the answers for what is research design in research? Remember, it's not just about picking a fancy method – it's about choosing the perfect tool to answer your burning questions. By carefully considering your goals and resources, you can design a research plan that gathers reliable information and helps you reach clear conclusions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the key components of a research design, how can i choose the best research design for my study, what are some common pitfalls in research design, and how can they be avoided, how does research design impact the validity and reliability of a study, what ethical considerations should be taken into account in research design.

Your ideal student home & a flight ticket awaits

Follow us on :

Related Posts

.jpg)

10 Things You Should Do Before Starting University

10 Hardest Engineering Degrees In the World In 2024

.webp)

US Grading System In 2024: A Comprehensive Guide

amber © 2024. All rights reserved.

4.8/5 on Trustpilot

Rated as "Excellent" • 4800+ Reviews by students

Rated as "Excellent" • 4800+ Reviews by Students

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents