An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Drinking Water Quality and Human Health: An Editorial

Patrick levallois.

1 Direction de la santé environnementale et de la toxicologie, Institut national de la santé publique du Québec, QC G1V 5B3, Canada

2 Département de médecine sociale et préventive, Faculté de médecine, Université Laval, Québec, QC G1V 0A6, Canada

Cristina M. Villanueva

3 ISGlobal, 08003 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected]

4 Universitat Pompeu Fabra (UPF), 08002 Barcelona, Spain

5 Consortium for Biomedical Research in Epidemiology and Public Health (CIBERESP), Carlos III Institute of Health, 28029 Madrid, Spain

6 IMIM (Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute), 08003 Barcelona, Spain

Drinking water quality is paramount for public health. Despite improvements in recent decades, access to good quality drinking water remains a critical issue. The World Health Organization estimates that almost 10% of the population in the world do not have access to improved drinking water sources [ 1 ], and one of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals is to ensure universal access to water and sanitation by 2030 [ 2 ]. Among other diseases, waterborne infections cause diarrhea, which kills nearly one million people every year. Most are children under the age of five [ 1 ]. At the same time, chemical pollution is an ongoing concern, particularly in industrialized countries and increasingly in low and medium income countries (LMICs). Exposure to chemicals in drinking water may lead to a range of chronic diseases (e.g., cancer and cardiovascular disease), adverse reproductive outcomes and effects on children’s health (e.g., neurodevelopment), among other health effects [ 3 ].

Although drinking water quality is regulated and monitored in many countries, increasing knowledge leads to the need for reviewing standards and guidelines on a nearly permanent basis, both for regulated and newly identified contaminants. Drinking water standards are mostly based on animal toxicity data, and more robust epidemiologic studies with an accurate exposure assessment are rare. The current risk assessment paradigm dealing mostly with one-by-one chemicals dismisses potential synergisms or interactions from exposures to mixtures of contaminants, particularly at the low-exposure range. Thus, evidence is needed on exposure and health effects of mixtures of contaminants in drinking water [ 4 ].

In a special issue on “Drinking Water Quality and Human Health” IJERPH [ 5 ], 20 papers were recently published on different topics related to drinking water. Eight papers were on microbiological contamination, 11 papers on chemical contamination, and one on radioactivity. Five of the eight papers were on microbiology and the one on radioactivity concerned developing countries, but none on chemical quality. In fact, all the papers on chemical contamination were from industrialized countries, illustrating that microbial quality is still the priority in LMICs. However, chemical pollution from a diversity of sources may also affect these settings and research will be necessary in the future.

Concerning microbiological contamination, one paper deals with the quality of well water in Maryland, USA [ 6 ], and it confirms the frequent contamination by fecal indicators and recommends continuous monitoring of such unregulated water. Another paper did a review of Vibrio pathogens, which are an ongoing concern in rural sub-Saharan Africa [ 7 ]. Two papers focus on the importance of global primary prevention. One investigated the effectiveness of Water Safety Plans (WSP) implemented in 12 countries of the Asia-Pacific region [ 8 ]. The other evaluated the lack of intervention to improve Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) in Nigerian communities and its effect on the frequency of common childhood diseases (mainly diarrhea) in children [ 9 ]. The efficacies of two types of intervention were also presented. One was a cost-effective household treatment in a village in South Africa [ 10 ], the other a community intervention in mid-western Nepal [ 11 ]. Finally, two epidemiological studies were conducted in industrialized countries. A time-series study evaluated the association between general indicators of drinking water quality (mainly turbidity) and the occurrence of gastroenteritis in 17 urban sites in the USA and Europe. [ 12 ] The other evaluated the performance of an algorithm to predict the occurrence of waterborne disease outbreaks in France [ 13 ].

On the eleven papers on chemical contamination, three focused on the descriptive characteristics of the contamination: one on nitrite seasonality in Finland [ 14 ], the second on geogenic cation (Na, K, Mg, and Ca) stability in Denmark [ 15 ] and the third on historical variation of THM concentrations in french water networks [ 16 ]. Another paper focused on fluoride exposure assessments using biomonitoring data in the Canadian population [ 17 ]. The other papers targeted the health effects associated with drinking water contamination. An extensive up-to-date review was provided regarding the health effects of nitrate [ 18 ]. A more limited review was on heterogeneity in studies on cancer and disinfection by-products [ 19 ]. A thorough epidemiological study on adverse birth outcomes and atrazine exposure in Ohio found a small link with lower birth weight [ 20 ]. Another more geographical study, found a link between some characteristics of drinking water in Taiwan and chronic kidney diseases [ 21 ]. Finally, the other papers discuss the methods of deriving drinking water standards. One focuses on manganese in Quebec, Canada [ 22 ], another on the screening values for pharmaceuticals in drinking water, in Minnesota, USA [ 23 ]. The latter developed the methodology used in Minnesota to derive guidelines—taking the enhanced exposure of young babies to water chemicals into particular consideration [ 24 ]. Finally, the paper on radioactivity presented a description of Polonium 210 water contamination in Malaysia [ 25 ].

In conclusion, despite several constraints (e.g., time schedule, fees, etc.), co-editors were satisfied to gather 20 papers by worldwide teams on such important topics. Our small experience demonstrates the variety and importance of microbiological and chemical contamination of drinking water and their possible health effects.

Acknowledgments

Authors want to acknowledge the important work of the IJERPH staff and of numbers of anonymous reviewers.

Author Contributions

P.L. wrote a first draft of the editorial and approved the final version. C.M.V. did a critical review and added important complementary information to finalize this editorial.

This editorial work received no special funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Essay on Water Quality

Students are often asked to write an essay on Water Quality in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Water Quality

What is water quality.

Water quality tells us how clean or dirty water is. It is important because it affects the health of people, animals, and plants. Clean water is safe to drink and supports life.

Why Water Quality Matters

Good water quality is crucial for our health. Drinking dirty water can make us very sick. It also matters for fish and other water animals to live.

Things That Pollute Water

Many things can make water dirty. Chemicals from factories, waste from homes, and oil spills are big problems. These pollutants harm water quality.

Keeping Water Clean

To keep water clean, we should not throw trash or chemicals into water. Everyone can help by being careful about what goes down the drain.

250 Words Essay on Water Quality

Water quality: the foundation of life, water is the elixir of life, sustaining all living organisms on our planet. its quality directly impacts our health and well-being. good water quality ensures clean drinking water, healthy ecosystems, and thriving communities., sources of water pollution, numerous factors contribute to water pollution. industrial waste, agricultural runoff, sewage discharge, and littering are major culprits. these pollutants contaminate water sources, making them unsafe for consumption and damaging aquatic life., consequences of poor water quality, poor water quality leads to a range of health issues, including waterborne diseases like cholera, typhoid, and dysentery. contaminated water also affects aquatic ecosystems, leading to biodiversity loss and disrupting the food chain. additionally, it hinders economic activities like fishing and tourism, which rely on clean water., water treatment and conservation, to ensure access to clean water, water treatment facilities employ various methods like filtration, disinfection, and reverse osmosis. these processes remove impurities and harmful substances, making water safe for consumption. water conservation practices such as rainwater harvesting, leak detection, and efficient irrigation techniques help reduce demand and preserve water resources., individual and collective action, improving water quality requires collective efforts. as individuals, we can reduce our water footprint by taking shorter showers, fixing leaky faucets, and using water-saving appliances. additionally, supporting policies that promote water conservation, pollution control, and sustainable development is crucial. in conclusion, water quality is paramount to life on earth. by understanding the sources of pollution, its consequences, and the importance of water treatment and conservation, we can work together to protect this vital resource and ensure a healthy future for generations to come., 500 words essay on water quality.

Various human activities contribute to water pollution, contaminating our precious water sources. Industrial waste, agricultural runoff, sewage discharge, and littering are major culprits. These pollutants, when released into water bodies, can cause severe damage to aquatic ecosystems and pose health risks to humans.

Effects of Water Pollution

Polluted water has numerous detrimental effects. It can cause a range of waterborne diseases, such as diarrhea, typhoid, and cholera, when consumed. Additionally, it harms aquatic life, leading to a decline in biodiversity and disruption of the food chain. Water pollution also affects the aesthetics of water bodies, making them unpleasant for recreational activities like swimming and fishing.

Importance of Water Quality

Maintaining good water quality is essential for several reasons. It ensures safe drinking water, preventing waterborne diseases and promoting public health. Healthy water bodies support thriving aquatic ecosystems, providing habitat for diverse plants and animals. Clean water is also vital for various economic activities, including agriculture, fishing, and tourism, contributing to sustainable livelihoods.

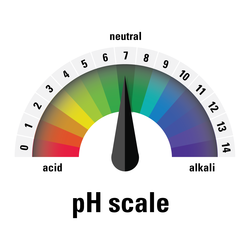

Water Quality Monitoring

Monitoring water quality is crucial for assessing its health and taking appropriate action to protect it. Regular testing for various parameters, such as pH, dissolved oxygen, and the presence of pollutants, helps identify potential problems and track water quality trends over time. This information is essential for developing effective water management and pollution control strategies.

Water Conservation and Preservation

Conserving water and preventing pollution are critical steps in maintaining water quality. Reducing water consumption, using water-efficient appliances, and fixing leaky faucets can help conserve precious water resources. Additionally, implementing pollution control measures, such as wastewater treatment plants and proper waste disposal systems, helps minimize the discharge of pollutants into water bodies.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 11 April 2022

Water quality assessment and evaluation of human health risk of drinking water from source to point of use at Thulamela municipality, Limpopo Province

- N. Luvhimbi 1 ,

- T. G. Tshitangano 1 ,

- J. T. Mabunda 1 ,

- F. C. Olaniyi 1 &

- J. N. Edokpayi 2

Scientific Reports volume 12 , Article number: 6059 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

24k Accesses

33 Citations

78 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Environmental sciences

- Risk factors

Water quality has been linked to health outcomes across the world. This study evaluated the physico-chemical and bacteriological quality of drinking water supplied by the municipality from source to the point of use at Thulamela municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa; assessed the community practices regarding collection and storage of water and determined the human health risks associated with consumption of the water. Assessment of water quality was carried out on 114 samples. Questionnaires were used to determine the community’s practices of water transportation from source to the point-of-use and storage activities. Many of the households reported constant water supply interruptions and the majority (92.2%) do not treat their water before use. While E. coli and total coliform were not detected in the water samples at source (dam), most of the samples from the street taps and at the point of use (household storage containers) were found to be contaminated with high levels of E. coli and total coliform. The levels of E. coli and total coliform detected during the wet season were higher than the levels detected during the dry season. Trace metals’ levels in the drinking water samples were within permissible range of both the South African National Standards and World Health Organisation. The calculated non-carcinogenic effects using hazard quotient toxicity potential and cumulative hazard index of drinking water through ingestion and dermal pathways were less than unity, implying that consumption of the water could pose no significant non-carcinogenic health risk. Intermittent interruption in municipal water supply and certain water transportation and storage practices by community members increase the risk of water contamination. We recommend a more consistent supply of treated municipal water in Limpopo province and training of residents on hygienic practices of transportation and storage of drinking water from the source to the point of use.

Similar content being viewed by others

Access to basic drinking water services, safe water storage, and household water treatment practice in rural communities of northwest Ethiopia

Assessment of groundwater quality for human consumption and its health risks in the Middle Magdalena Valley, Colombia

Ecological and health risk assessment of trace metals in water collected from Haripur gas blowout area of Bangladesh

Introduction.

Water is among the major essential resources for the sustenance of humans, agriculture and industry. Social and economic progress are based and sustained upon this pre-eminent resource 1 . Availability and easy access to safe and quality water is a fundamental human right 2 and availability of clean water and sanitation for all has been listed as one of the goals to be achieved by the year 2030 for sustainable development by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) 3 .

The physical, chemical, biological and aesthetic properties of water are the parameters used to describe its quality and determine its capability for a variety of uses including the protection of human health and the aquatic ecosystem. Most of these properties are influenced by constituents that are either dissolved or suspended in water and water quality can be influenced by both natural processes and human activities 4 , 5 . The capacity of a population to safeguard sustainable access to adequate quantities and acceptable quality of water for sustaining livelihoods of human well-being and socioeconomic growth; as well as ensuring protection against pollution and water related disasters; and for conserving ecosystems in a climate of peace and political balance is regarded to as water security 6 .

Although the world’s multitudes have access to water, in numerous places, the available water is seldom safe for human drinking and not obtainable in sufficient quantities to meet basic health needs 7 . The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that about 1.1 billion people globally drink unsafe water and most diarrheal diseases in the world (88%) is attributed to unsafe water, poor sanitation and unhygienic practices. In addition, the water supply sector is facing enormous challenges due to climate change, global warming and urbanization. Insufficient quantity and poor quality of water have serious impact on sustainable development, especially in developing countries 8 .

The quality of water supplied by the municipality is to be measured against the national standards for drinking water developed by the federal governments and other relevant bodies 9 . These standards considered some attributes to be of primary importance to the quality of drinking water, while others are considered to be of secondary importance. Generally, the guidelines for drinking water quality recommend that faecal indicator bacteria (FIB), especially Escherichia coli ( E. coli ) or thermo tolerant coliform (TTC), should not be found in any 100 mL of drinking water sample 8 .

Despite the availability of these standards and guidelines, numerous WHO and United Nations International Children Emergency Fund (UNICEF) reports have documented faecal contamination of drinking water sources, including enhanced sources of drinking water like the pipe water, especially in low-income countries 10 . Water-related diseases remain the primary cause of a high mortality rate for children under the age of five years worldwide. These problems are specifically seen in rural areas of developing countries. In addition, emerging contaminants and disinfection by-products have been associated with chronic health problems for people in both developed and developing countries 11 . Efforts by governmental and non-governmental organizations to ensure water security and safety in recent years have failed in many areas due to a lack of sustainability of water supply infrastructures 12 .

Water quality, especially regarding the microbiological content, can be compromised during collection, transport, and home storage. Possible sources of drinking water contamination are open field defecation, animal wastes, economic activities (agricultural, industrial and businesses), wastes from residential areas as well as flooding. Any water source, especially is vulnerable to such contamination 13 . Thus, access to a safe source alone does not ensure the quality of water that is consumed, and a good water source alone does not automatically translate to full health benefits in the absence of improved water storage and sanitation 14 . In developing countries, it has been observed that drinking-water frequently becomes re-contaminated following its collection and during storage in homes 15 .

Previous studies in developing countries have identified a progressive contamination of drinking water samples with E. coli and total coliforms from source to the point of use in the households, especially as a result of using dirty containers for collection and storage processes 16 , 17 , 18 . Also, the type of water treatment method employed at household levels, the type of container used to store drinking water, the number of days of water storage, inadequate knowledge and a lack of personal and domestic hygiene have all been linked with levels of water contamination in households 19 , 20 .

In South Africa, many communities have access to treated water supplied by the government. However, the water is more likely to be piped into individual households in the urban than rural areas. In many rural communities, the water is provided through the street taps and residents have to collect from those taps and transport the water to their households. Also, water supply interruptions are frequently experienced in rural communities, hence, the need for long-term water storage. A previous study of water quality in South Africa reported better quality of water at source than the water samples obtained from the household storage containers, showing that water could be contaminated in the process of transporting it from source to the point of use 21 .

This study was conducted in a rural community at Thulamela Municipality, Limpopo province, South Africa, to describe the community’s drinking water handling practices from source to the point of use in the households and evaluate the quality of the water from source (the reservoir), main distribution systems (street taps), yard connections (household taps) and at the point of use (household storage containers). Water quality assessment was done by assessing the microbial contamination and trace metal concentrations, and the possible health risks due to exposure of humans to the harmful pathogens and trace metals in the drinking water were determined.

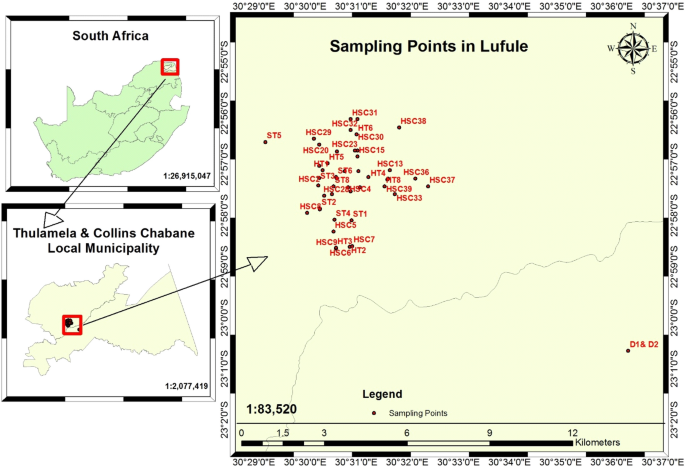

The study was conducted at Lufule village in Thulamela municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa. The municipality is situated in the eastern subtropical region of the province. The province is generally hot and humid and it receives much of its rainfall during summer (October–March) 22 . Lufule village is made up of 386 households and a total population of 1, 617 residents 23 . The study area includes Nandoni Dam (main reservoir) which acquires its raw water from Luvuvhu river that flows through Mutoti and Ha-Budeli villages just a few kilometers away from Thohoyandou town. Nandoni dam is where purification process takes place to ensure that the water meets the standards set for drinking water. This dam is the main source of water around the municipality, and it is the one which supplies water to selected areas around the dam, including Lufule village. Water samples for analysis were collected from the dam (D), street taps (ST), household taps (HT) and household storage containers (HSC) (Fig. 1 ).

Map of the study area showing water samples’ collection areas.

Research design

This study adopted a quantitative design comprising of field survey and water analysis.

Field survey

The survey was done to identify the selected households and their shared source of drinking water (street taps). The village was divided into 10 quadrants for sampling purposes. From each quadrant, 6 households were randomly selected where questionnaires were distributed and household water samples were also collected for analysis.

Quantitative data collection

A structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was employed for data collection in the selected households. The population of Lufule village residents aged 15–69 years is 1, 026 (Census, 2011). About 10% of the adult population (~ 103) was selected to complete the questionnaires to represent the entire population. However, a total of 120 questionnaires were distributed, to take care of those which might be lacking vital information and therefore would not qualify to be analysed. Adults between the ages of 18 and 69 years were randomly selected to complete the questionnaire which includes questions concerning demographic and socio-economic statuses of the respondents, water use practices, sanitation, hygiene practices as well as perception of water quality and health. The face validity of the instrument was ensured by experts in the Department of Public Health, University of Venda, who reviewed questionnaire and confirmed that the items measure the concepts of interest relevant to the study 24 . Respondents were given time to go through the questionnaire and the researcher was present to clear any misunderstanding that may arise.

Water sampling

Permission to collect water samples from the reservoir tank at the Nandoni water treatment plant and households was obtained from the plant manager and the households’ heads respectively. Two sampling sites were identified at the dam, from where a water sample each was collected during the dry and the wet season. Similarly, 8 sampling sites were identified from the street and household taps, while 60 sampling sites were targeted for the household storage containers. However, only 39 household sites were accessible for sample collection, due to unavailability of the residents at the times of the researcher’s visit. Thus, water samples were collected from a total of 57 sites. Samples were collected from each of the sites during the dry (12th–20th April, 2019) and wet seasons (9th–12th December, 2019) between the hours of 08h00 and 14h30. A total of 114 samples were collected during the sampling period: 4 from the reservoir, 16 from street taps, 16 from household taps and 78 from households’ storage systems. Water samples were collected in 500 mL sterile polyethylene bottles. After collection, the containers were transported to the laboratory on ice in a cooler box. Each of the samples was tested for physico-chemical parameters, microbial parameters and trace metals’ concentration.

Physicochemical parameters’ analysis

Onsite analysis of temperature, pH, Electrical conductivity (EC) and Total Dissolved Solids (TDS) were performed immediately after sampling using a multimeter (model HI “HANNA” instruments), following the standards protocols and methods of American Public Health Association (APHA) 25 . The instrument was calibrated in accordance with the manufacturer’s guideline before taking the measurements. The value of each sample was taken after submerging the probe in the water and held for a couple of minutes to achieve a reliable reading. After measurement of each sample, the probe was rinsed with de-ionized water to avoid cross contamination among different samples.

ICP-OES and ICP-MS analyses of major and trace elements

An inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrophotometer (ICP-OES) was used to analyse the major metals (Calcium (Ca), Sodium (Na), Potassium (K) and Magnesium (Mg)) in the water samples while inductively coupled plasma mass spectrophotometer (ICP-MS) was used to analyze the trace metals. The instrument was standardized with a multi-element calibration standard IV for ICP for Copper (Cu), Manganese (Mn), Iron (Fe), Chromium (Cr), Cadmium (Cd), Arsenic (As), Nickel (Ni), Zinc (Zn), Lead (Pb) and Cobalt (Co) and analytical precision was checked by frequently analysing the standards as well as blanks. ICP multi Standard solution of 1000 ppm for K, Ca, Mg and Na was prepared with NH 4 OAC for analysis to verify the accuracy of the calibration of the instrument and quantification of selected metals before sample analysis, as well as throughout the analysis to monitor drift.

Microbiological water quality analysis

Analysis of microbial parameters was conducted within 6 h of collection as recommended by APHA 25 . Viable Total coliform and E. coli were quantified in each sample using the IDEXX technique approved by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA). Colilert media was added to 100 mL sample and mixed until dissolved completely. The solution was poured into an IDEXX Quanti-Tray/2000 and sealed using the Quanti-Tray sealer 26 . The samples were incubated at 35 °C for 24 h. Trays were scanned using a fluorescent UV lamp to count fluorescent wells positive for E. coli concentration and counted with the most probable number (MPN) table provided by the manufacturer 27 .

Health risk assessment

Risk assessment have been estimated for ingestion and dermal pathways. Exposure pathway to water for ingestion and dermal routes are calculated using Eqs. ( 1 ) and ( 2 ) below:

where Exp ing : exposure dose through ingestion of water (mg/kg/day); BW: average body weight (70 kg for adults; 15 kg for children); Exp derm : exposure dose through dermal absorption (mg/kg/day); C water : average concentration of the estimated metals in water (μg/L); IR: ingestion rate in this study (2.0 L/day for adults; 1.0 L/day for children); ED: exposure duration (70 years for adults; and 6 years for children);AT: averaging time (25,550 days for an adult; 2190 days for a child); EF: exposure frequency (365 days/year) SA: exposed skin area (18.000 cm 2 for adults; 6600 cm 2 for children); K p : dermal permeability coefficient in water, (cm/h), 0.001 for Cu, Mn, Fe and Cd, while 0.0006 for Zn; 0.002 for Cr and 0.004 for Pb; ET: exposure time (0.58 h/ day for adults; 1 h/day for children) and CF: unit conversion factor (0.001 L/cm 3 ) 28 .

The hazard quotient (HQ) of non-carcinogenic risk by ingestion pathway can be determined by Eq. ( 3 )

where RfD ing is ingestion toxicity reference dose (mg/kg/day). An HQ under 1 is assumed to be safe and taken as significant non-carcinogenic, but HQ value above 1 may indicate a major potential health concern associated with over-exposure of humans to the contaminants 28 .

The total non-carcinogenic risk is represented by hazard index (HI). HI < 1 means the non-carcinogenic risk is acceptable, while HI > 1 indicates the risk is beyond the acceptable level 29 . The HI of a given pollutant through multiple pathways can be calculated by summing the hazard quotients by Eq. ( 4 ) below.

Carcinogenic risks for ingestion pathway is calculated by Eq. ( 5 ). For the selected metals in the study, carcinogenic risk (CR ing ) can be defined as the probability that an individual will develop cancer during his lifetime due to exposure under specific scenarios 30 .

where CRing is carcinogenic risk via ingestion route and SF ing is the carcinogenic slope factor.

Data analysis

Data obtained from the survey were analysed using Microsoft Excel and presented as descriptive statistics in the form of tables and graphs. The experimental data obtained was compared with the South African National Standards (SANS) 31 and Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF) 32 guidelines for domestic water use.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethical clearance for this study was granted by the University of Venda Health, Safety and Research Ethics’ Committee (SHS/19/PH/14/1104). Permission to conduct the study was obtained from the Department of Water affairs, Limpopo province, Vhembe district Municipality and the selected households. Respondents were duly informed about the study and informed consent was obtained from all of them. The basic ethical principles of voluntary participation, informed consent, anonymity and confidentiality of respondents were duly complied with during data collection, analysis and reporting.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

A total of 120 questionnaires were distributed but only 115 were completed, making a good response rate of 95%. The socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents are presented in Table 1 .

Household water supply

Many households (68.7%) had their primary water source from the municipality piped into their yards, but only 5.2% have the water flowing within their houses. The others have to fetch water at their neighbours’ yards or use the public taps on the streets. When the primary water supply is interrupted (i.e. when there is no water flowing through the pipes within the houses, yards or the public taps due to water rationing activities by the municipality, leakage of water distribution pipes, vandalization of pipes during road maintenance, etc.), the interruption usually lasts between a week or two, during which the respondents resort to other alternative sources. A return trip to the secondary source of water usually takes between 10 and 30 min for more than half of the respondents (53.0%) (Table 2 ).

Water storage and treatment practices at the household

Household water was most frequently stored in plastic buckets (n = 78, 67.8%), but ceramic vessels, metal buckets and other containers are also used for water storage (Fig. 2 ). Most households reported that their drinking water containers were covered (n = 111, 96.5%). More than half (53.9%) of the respondents used cups with handles to collect water from the storage containers whereas 37.4% used cups with no handles. Only 7.8% households reported that they treat their water before use mainly by boiling. Approximately 82.6% of respondent are of the opinion that one cannot get sick from drinking water and only 17.4% knew the risks that come with untreated water, and cited diarrhoea, schistosomiasis, cholera, fever, vomiting, ear infections, malnutrition, rash, flu and malaria as specific illnesses associated with water. Despite these perceptions, the majority (76.5%) were satisfied with their current water source. The few (23.5%) who were not satisfied cited poor quality, uncleanness, cloudiness, bad odour and taste in the water as reasons for their dissatisfaction (Table 3 ).

Examples of household water storage containers, some with lids and others without lids (photo from fieldwork).

Sanitation practices at the household level

More than half of the respondents (67%) use pit toilets, whereas only 26.1% use the flush to septic tank system, most of the toilets (93.9%) have a concrete floor. About 76.5% of households do not have designated place to wash their hands, however, all respondents indicated that they always wash their hands with soap or any of its other alternatives before preparing meals and after using the toilet (Table 4 ).

Water samples analysis

The water samples analyses comprise of microbial analysis, physico-chemical analysis and trace metals' parameters.

Microbial analysis

The samples from the reservoir during dry and wet season had 0 MPN/100 mL of total coliform and E. coli and were within the recommended limits of WHO and SANS for drinking water. During the wet season, seven out of the eight water samples collected from the street taps were contaminated with total coliform, while four of the samples taken from the same source were contaminated with total coliform during the dry season. Water samples from street taps 3 and 7 (ST 3 and ST7) were contaminated with total coliform during both seasons, however, the total coliform counts during the wet season were more than the counts during the dry season. None of the samples was contaminated with E. coli during the dry season, however, 2 samples from the street taps (ST3 & ST6) were found to be contaminated with E. coli during the wet season. Samples from household taps showed a similar trend with the street taps—with all samples being contaminated with total coliform during the wet season. Though 7 of the 8 samples taken from the household taps were contaminated with total coliform during the dry season, the samples from the same sources showed a higher level of total coliform in the wet season, with almost all the samples showing contamination at maximum detection levels of more than 2000 MPN/100 mL, except one sample (HT8) which showed a higher level of contamination with total coliform during the dry compared with the wet season. Only one sample (HT4) was found to be contaminated with E. coli during both dry and wet season. This shows that total coliform contamination levels are higher during the wet season than the dry season (Table 5 ).

Water samples from household storage containers (HSC) showed a higher level of total coliform during the wet season than the dry season and more samples were contaminated with E. coli during the wet season also (Table 6 ). A higher level of contamination was recorded for the HSCs compared to the street and household taps.

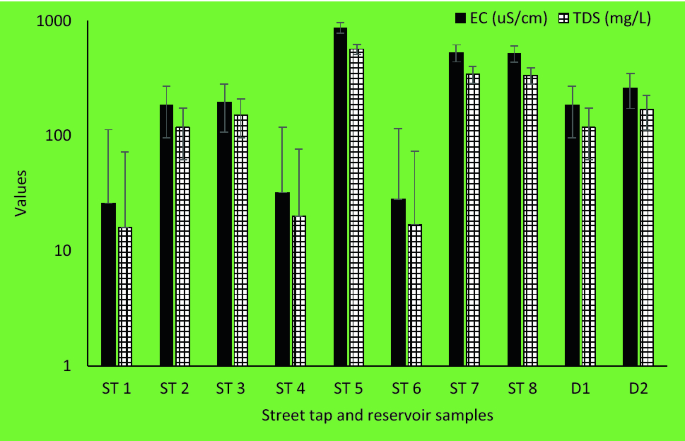

Physico-chemical analysis

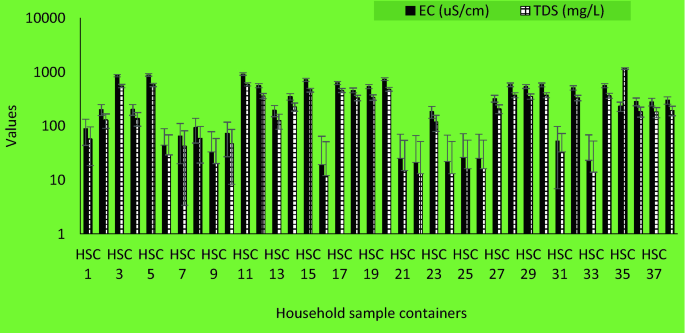

In the reservoir samples, the pH value ranged from 8.37 to 8.45, EC ranged between 183 and 259 µS/cm whereas TDS varied between 118 and 168 mg/L. Similarly, in the street tap samples, pH value ranged from 7.28 and 9.33, EC ranged between 26 and 867 µS/cm whereas TDS varied between 16 and 562 mg/L (Fig. 3 ).

EC and TDS levels for the street taps and reservoir samples.

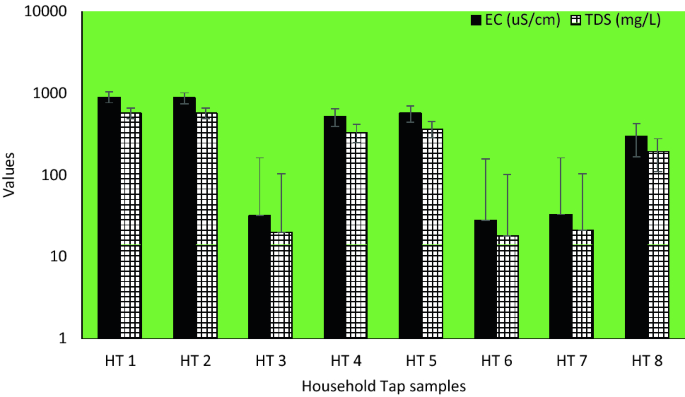

In the household taps, pH value ranged from 7.70–9.98, EC range between 28–895 µS/cm and TDS varied between 18 and 572 mg/L (Fig. 4 ).

EC and TDS levels for household taps.

In household storage container samples, the pH value ranges from 7.67–9.77, EC ranged between 19–903 µS/cm and TDS values ranged from 12–1148 mg/L (Fig. 5 ).

EC and TDS levels for household storage container samples.

Analysis of cations and trace metals in water

To detect the cations’ and trace metals’ concentrations in the water samples, representative samples from each of the sources were selected for analysis. The concentration of Calcium ranged between 2.14 and 31.65 mg/L, Potassium concentration ranged from 0.14 to 1.85 mg/L, Magnesium concentration varied from 1.32 to 16.59 mg/L, Sodium ranged from 0.18 to 12.96 mg/L (Table 7 ).

Trace metals’ analysis

The minimum and maximum concentrations of trace metals (Al, Mn, Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Zn, As and Pb) present in water samples from selected street taps, household taps and household storage containers are presented in Table 8 .

Hazard quotient (HQ) and carcinogenic risk assessment

Table 9 presents the exposure dosage and hazard quotient (HQ) for ingestion and dermal pathway for metals. The HQ ing and HQ derm for all analyzed trace metals in both children and adults were less than one unit, indicating that there are no potential non-carcinogenic health risks associated with consumption of the water. Table 10 presents the total Hazard Quotient and Health risk index (HI) for trace metals in the water samples, showing that residents of the study area are not susceptible to non-cancer risks due to exposure to trace metals in drinking water. Table 11 presents the cancer risk associated with the levels of Ni, As and Pb in the drinking water samples. The table shows that only the maximum levels of lead had the highest chance of cancer risks for both adults and children.

This study provides information about the quality of drinking water in a selected rural community of Thulamela municipality of Limpopo province, South Africa, taking into consideration the physicochemical, microbiological and trace metals’ parameters of the treated water supplied to the village by the government, through the municipality. Many participants in the study have their primary source of water piped into their yards, while very few have water in their houses. This implies that getting water for household use would involve collecting the water from the yard and then into the storage containers. Those who do not have the taps in their yards have to collect water from the neighbours’ yards or the street taps. This observation is not restricted to the study area, as a similar situation has been observed in other rural communities of Limpopo Province 21 . This need to pass water through multiple containers before the point of use increases the risk of contamination.

Residents of the study area, just like residents of other settlements in Thulamela Municipality 21 , store their drinking water in plastic buckets, ceramic vessels, jerry cans and other containers. Almost all the respondents (96.5%) claim that their water storage vessels are covered and that their drinking water usually stays for less than a week in the storage containers (87.8%). Covering of water storage containers reduces the risk of water contamination from dust or other airborne particles. However, intermittent interruption of municipal water supply lasting for a week or more in the study area and the consequent use of alternative sources of water predispose the residents to various health risks as intermittent interruption in water supply has been linked to higher chances of contamination in the distribution systems, compared with continuous supply; in addition, the alternative sources of water may not be of a good quality as the treated municipal water 33 , 34 , yet, more than half of the respondents in this study (53%) use water directly from source without any form of treatment. This is because many residents in rural communities of Limpopo province believe that the water they drink is of good quality and thus do not need any further treatment 21 . The few who treat their water before drinking mostly use the boiling method. While boiling and other home-based interventions like solar disinfection of water have been reported to improve the quality of drinking water; drinking vessels, like cups, have also been implicated in water re-contamination of treated water at the point of use 16 and most respondents (91.3%) in this study admittedly use cups to collect water from the storage containers. The risk of contamination is even increased when cups without handles are used, where there is a higher chance that the water collector would touch the water in the container with his/her fingers. The Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that containers for drinking water should be fitted with a small opening with a cover or a spigot, through which water can be collected while the container remains closed, without dipping any potentially contaminated object into the container 35 . However, it is noteworthy that all the respondents claim to always wash their hands with soap (or its equivalents) and water after using the toilets, a constant practice of hand washing after using the toilet has been associated with a reduced risk of water contamination with E. coli 19 .

Treated water from the dam tested negative for both total coliform and E. coli hence complied with regulatory standards of SANS 31 and WHO 8 . The results could probably be due to the use of chlorine as a disinfectant in the treatment plant. Using disinfectants, pathogenic bacteria from the water can be killed and water made safe for the user. Similar studies have also reported that treated water in urban water treatment plants contains no total coliforms and E. coli 36 . In contrast, treated water sources in rural areas have been reported to have considerable levels of total coliform and E. coli 37 . The reason alluded to this include lack of disinfectant, no residual chlorine in the treated water, high prevalence of open defecation and unhygienic practices in proximity to water sources 38 .

From the water samples collected from the street taps, 62.5% were found to be contaminated with total coliform during the dry season, while the percentage rose to 87.5% during the wet season. The street tap which is about 13 km from the reservoir recorded high levels of total coliform ranging from 1.0 -2000 MPN/100 mL with most of the sites exceeding the WHO guidelines of 10 MPN/100 mL 8 . In both seasons, all the samples tested negative for E. coli , this complies with the WHO guideline of 0 MPN/100 mL. While the water leaving the treatment plant met bacteriological standards, the detection of coliform bacteria in the distribution lines suggest that the water is contaminated in the distribution networks. This could be due to the adherence of bacteria onto biofilms or accidental point source contamination by broken pipes, installation and repair works 39 . Furthermore, the water samples from households’ storage containers were contaminated by total coliform (73% and 85%) and E. coli (10.4% and 13.2%) during the dry and wet season, respectively. Microbiological contamination of household water stored in containers could be due to unhygienic practices occurring between the collection point and the point-of-use 40 , 41 .

Generally, higher levels of contamination were recorded in the wet season than in the dry season. The wet season in Thulamela Municipality is often characterized with increased temperature which could lead to favourable condition for microbial growth. Also, the treatment plant usually makes use of the same amount of chlorine for water purification during both seasons, even though influent water would be of a higher turbidity during the wet season, hence reducing the levels of residual chlorine 42 .

The pH of the analyzed samples from the study area ranged from 7.15 to 9.92. Most of the samples were within the values recommended by SANS (5 to 9.7) and comparable to results from previous similar studies 31 , 43 . Also, the electrical conductivity of all water samples from this study ranged from 28 µS/cm to 903 µS/cm which complied with the recommended value of SANS: < 1700 µS/cm 31 . The presence of dissolved solids such as calcium, chloride, and magnesium in water samples is responsible for its electrical conductivity 44 .

Total dissolved solids are the inorganic salts and small amounts of organic substance, which are present as solution in water 45 . Water has the ability to dissolve a wide range of inorganic and some organic minerals or salts such as potassium, calcium, sodium, bicarbonates, chlorides, magnesium, sulphates, etc. These minerals produced unwanted taste and colour in water 46 . A high TDS value indicates that water is highly mineralised. The recommended TDS value set for drinking water quality is ≤ 1200 mg/L 31 . In this study, the TDS values ranged from 18 mg/L to 572 mg/L. Hence, the TDS of all the household’s storage samples complied with the guidelines and consistent with previous studies 47 .

The analysis of magnesium (1.32 to 16.59 mg/L) and calcium (2.14 to 31.65 mg/L) concentrations showed that they were within the permissible range recommended for drinking water by SANS 31 and WHO 8 . All living organisms depend on magnesium in all types of cells, body tissues and organs for variety of functions while calcium is very important for human cell physiology and bones. Similar studies in Ethiopia and Turkey also showed acceptable levels of these metals in drinking water 46 , 48 . Likewise, the levels of potassium (0.14 to 1.85 mg/L) and sodium (0.18 to 12.96 mg/L) were within the permissible limit of WHO and SANS and may not cause health related problems. Sodium is essential in humans for the regulation of body fluid and electrolytes, and for proper functioning of the nerves and muscles, however, excessive sodium in the body can increase the risk of developing a high blood pressure, cardiovascular diseases and kidney damage 49 , 50 . Potassium is very important for protein synthesis and carbohydrate metabolism, thus, it is very important for normal growth and body building in humans, but, excessive quantity of potassium in the body (hyperkalemia) is characterized with irritability, decreased urine production and cardiac arrest 51 .

Metals like copper (Cu), cobalt (Co) and zinc (Zn) are essential requirements for normal body growth and functions of living organisms, however, in high concentrations, they are considered highly toxic for human and aquatic life 42 . Elevated trace metal(loids) concentrations could deteriorate water quality and pose significant health risks to the public due to their toxicity, persistence, and bio accumulative nature 52 . In this study, the concentrations of Manganese, Cobalt, Nickel and Copper all complied with the recommended concentration by SANS for domestic water use.

Aluminum concentration in the drinking water samples ranged from 1.25—13.46 µg/L. All analysed samples complied with the recommended concentration of ≤ 300 µg/L for domestic water use 31 . The recorded levels of Al in water from this study should not pose any health risk. At a high concentration, aluminium affects the nervous system, and it is linked to several diseases, such as Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases 53 . Iron (Fe) is an essential element for human health, required for the production of protein haemoglobin, which carries oxygen from our lungs to the other parts of the body. Insufficient or excess levels of iron can have negative effect on body functions 54 . The recommended concentration of iron in drinking water is ≤ 2000 µg/L 31 . In this study, the concentration of iron in the samples ranged from 0.96 to 73.53 µg/L. Similar results were reported by Jamshaid et al. in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province 55 . A high concentration of Fe in water can give water a metallic taste, even though it is still safe to drink 56 .

The levels of Pb, As and Zn were in the range of 0.02–0.57 µg/L, 0.02–0.17 µg/L, and 2.54–194.96 µg/L, respectively whereas Cr was not detected in the samples collected. The levels recorded complied with the SANS 31 and WHO 8 guidelines for drinking water. Similar results were reported by Mohod and Dhote 57 . Lead is not desirable in drinking water because it is carcinogenic and can cause growth impairment in children 41 . Inorganic arsenic is a confirmed carcinogen and is the most significant chemical contaminant in drinking-water globally 44 . Zinc deficiency can cause loss of appetite, decreased sense of taste and smell, slow wound healing and skin sores 58 . Cr is desirable at low concentration but can be harmful if present in elevated levels.

The hazard quotient (HQ) takes into consideration the oral toxicity reference dose for a trace metal that humans can be exposed to 59 . Health related risk associated with the exposure through ingestion depends on the weight, age and volume of water consumed by an individual. HQ ing and HQ derm for all analyzed trace metals in both children and adults were less than one unit (Table 9 ), indicating that there are no potential non-carcinogenic health risks associated with the consumption of the water from the study area either by children or adults. The calculated average cumulative health risk index (HI) for children and adult was 3.88E-02 and 1.78E-02, respectively. HQ across metals serve as a conservative assessment tool to estimate high-end risk rather than low end-risk in order to protect the public. This served as a screen value to determine whether there is major significant health risk 60 . The results in this study signifies that the population of the investigated area are not susceptible to non-cancer risks due to exposure to trace metals in drinking water. Similar observation has been reported by Bamuwamye et al. after investigating human health risk assessment of trace metals in Kampala (Uganda) drinking water 61 . It should be noted that the hazard index values for children were higher than that of adult, suggesting that children were more susceptible to non-carcinogenic risk from the trace metals.

Drinking water with trace metals such as Pb, As, Cr and Cd could potentially enhance the risk of cancer in human beings 62 , 63 . Long term exposure to low amounts of toxic metals might, consequently, result in many types of cancers. Using As, Ni and Pb carcinogens, the total exposure risks of the residents in Table 11 . For trace metals, an acceptable carcinogenic risk value of less than 1 × 10 −6 is considered as insignificant and the cancer risk can be neglected; while an acceptable carcinogenic risk value of above 1 × 10 –4 is considered as harmful and the cancer risk is worrisome. Amongst the studied trace metals, only the maximum levels of lead for both adults and children had the highest chance of cancer risks (1.93E−03 and 4.46E−03) while Arsenic and Nickel have no chance of cancer risk with values of 3.34E−06; 7.72E−06 and 2.24E−05; 5.18E−05, in both adults and children respectively. The only cancer risk to residents of the studied area could be from the cumulative ingestion of lead in their drinking water. The levels of Pb recorded in this study complied to the SANS guideline value for safe drinking water. While the levels of Pb from the dam and the street pipes were relatively low, higher levels where recorded at household taps and storage containers and this may be due to the kind of storage containers and pipes used in those households. Generally, the water supply is of low Pb levels which should not pose any health risk to the consumers. However, the residents in rural areas should be properly educated on the kind of materials to be used for safe storage of water which should not pose an additional health burden. The likelihood of cancer risk was only associated with the consumption of the highest levels of Pb reported for a life time for adults (set at 70 years) and 6 years for children. Consistent consumption of water from the same source throughout an adult’s lifetime is unlikely as residents in those communities may change their locations at some points, hence reducing the possible risk associated with consistent exposure to the same levels of Pb.

Conclusions

The study shows that as distance increases from the treatment reservoir to distribution points, the cross-contamination rate also increases, therefore, good hygienic practices is required while transporting, storing and using water. Unhygienic handling practices at any point between collection and use contribute to the deterioration of drinking water quality.

The physicochemical, bacteriological quality and trace metals’ concentration of water samples from treated source, street taps and household storage containers were majorly within the permissible range of both WHO and SANS drinking water standards. HQ for both children and adults were less than unity, showing that the drinking water poses less significance health threat to both children and adults. Amongst the studied trace metals, only the maximum level of lead for both adults and children has the highest chance of cancer risks.

We recommend that appropriate measures should be taken to maintain residual free chlorine at the distribution points, supply of municipal treated water should be more consistent in all the rural communities of Thulamela municipality, Limpopo province and residents should be trained on hygienic practices of transportation and storage of drinking water from the source to the point of use.

Data availability

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the first author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

American Public Health Association

Centres for Disease Control and Prevention

Department of Water Affairs and Forestry

Electrical conductivity

Health risk index

Hazard quotient

Household storage containers

Household taps

Inductively coupled plasma mass spectrophotometer

Inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrophotometer

Most probable number

South African National Standards

Street taps

Total Dissolved Solids

United Nations General Assembly

United Nations International Children Emergency Fund

United States Environmental Protection Agency

World Health Organization

Taiwo, A.M., Olujimi, O.O., Bamgbose, O. & Arowolo, T.A. Surface water quality monitoring in Nigeria: Situational analysis and future management strategy. In Water Quality Monitoring and Assessment (ed. Voudouris, K) 301–320 (IntechOpen, 2012).

Corcoran, E., et al. Sick water? The central role of wastewater management in sustainable development: A rapid response assessment. United Nations Enviromental Programme UN-HABITAT, GRID-Arendal. https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/9156 (2010).

United Nations, The 2030 Agenda and the Sustainable Development Goals: An opportunity for Latin America and the Caribbean (LC/G.2681-P/Rev.3), Santiago (2018).

Hubert, E. & Wolkersdorfer, C. Establishing a conversion factor between electrical conductivity and total dissolved solids in South African mine waters. Water S.A. 41 , 490–500 (2015).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Department of Water Affairs (DWA). Groundwater Strategy. Department of Water Affairs: Pretoria, South Africa. 64 (2010).

Lu, Y., Nakicenovic, N., Visbeck, M. & Stevance, A. S. Policy: Five priorities for the UN sustainable development goals. Nature 520 , 432–433 (2015).

Article ADS PubMed Google Scholar

Shaheed, A., Orgil, J., Montgomery, M. A., Jeuland, M. A. & Brown, J. Why, “improved” water sources are not always safe. Bull. World Health Organ. 92 , 283–289 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

WHO. Guidelines for Drinking Water Quality 4th Edn (World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 2011). http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44584/1/9789241548151_eng.pdf .

Patil, P. N., Sawant, D. V. & Deshmukh, R. N. Physico-chemical parameters for testing of water—a review. Int. J. Environ. Sci. 3 , 1194–1207 (2012).

CAS Google Scholar

Bain, R. et al. Fecal contamination of drinking-water in low-and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 11 , e1001644 (2014).

Younos, T. & Grady, C.A. Potable water, emerging global problems and solutions. In The Handbook of Environmental Chemistry 30 (2014).

Tigabu, A. D., Nicholson, C. F., Collick, A. S. & Steenhuis, T. S. Determinants of household participation in the management of rural water supply systems: A case from Ethiopia. Water Policy. 15 , 985–1000 (2013).

Article Google Scholar

Oljira, G. Investigation of drinking water quality from source to point of distribution: The case of Gimbi Town, in Oromia Regional State of Ethiopia (2015).

Clasen, T., Haller, L., Walker, D., Bartram, J. & Cairncross, S. Cost-effectiveness of water quality interventions for preventing diarrhoeal disease in developing countries. J. Water Health 5 , 599–608 (2007).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Too, J. K., Sang, W. K., Ng’ang’a, Z. & Ngayo, M. O. Fecal contamination of drinking water in Kericho District, Western Kenya: Role of source and household water handling and hygiene practices. J. Water Health 14 , 662–671 (2016).

Rufener, S., Mausezahl, D., Mosler, H. & Weingartner, R. Quality of drinking-water at source and point-of-consumption—drinking cup as a high potential recontamination risk: A field Study in Bolivia. J. Health Popul. Nutri. 28 , 34–41 (2010).

Google Scholar

Nsubuga, F. N. W., Namutebi, E. N. & Nsubuga-ssenfuma, M. Water resources of Uganda: An assessment and review. Water Resour. Prot. 6 , 1297–1315 (2014).

Rawway, M., Kamel, M. S. & Abdul-raouf, U. M. Microbial and physico-chemical assessment of water quality of the river Nile at Assiut Governorate (Upper Egypt). J. Ecol. Health Environ. 4 , 7–14 (2016).

Agensi, A., Tibyangye, J., Tamale, A., Agwu, E. & Amongi C. Contamination potentials of household water handling and storage practices in Kirundo Subcounty, Kisoro District, Uganda. J. Environ. Public Health. Article ID 7932193, 8 pages (2019).

Mahmud, Z. H. et al. Occurrence of Escherichia coli and faecal coliforms in drinking water at source and household point-of-use in Rohingya camps, Bangladesh. Gut Pathog. 11 , 52. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-019-0333-6 (2019).

Edokpayi, J. N. et al. Challenges to sustainable safe drinking water: A case study of water quality and use across seasons in rural communities in Limpopo Province, South Africa. Water 10 , 159 (2018).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Musyoki, A., Thifhulufhelwi, R. & Murungweni, F. M. The impact of and responses to flooding in Thulamela Municipality, Limpopo Province, South Africa, Jàmbá. J. Disaster Risk Stud. 8 , 1–10 (2016).

Census 2011. Main Place: Lufule. Accessed from Census 2011: Main Place: Lufule (adrianfrith.com) on 30/01/2022.

Bolarinwa, O. A. Principles and methods of validity and reliability testing of questionnaires used in social and health science researches. Niger. Postgrad. Med. J. 22 , 195–201 (2015).

Association, A. P. H. Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Waste Water 16th edn. (American Public Health Association, Washington, 1992).

Bernardes, C., Bernardes, R., Zimmer, C. & Dorea, C. C. A simple off-grid incubator for microbiological water quality analysis. Water 12 , 240 (2020).

Rich CR, Sellers JM, Taylor HB, IDEXX Laboratories Inc. Chemical reagent test slide. U.S. Patent Application 29/218,589. (2006).

Naveedullah, et al. Concentrations and human health risk assessment of selected heavy metals in surface water of siling reservoir watershed in Zhejiang Province, China. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 23 , 801–811 (2014).

Wu, J. & Sun, Z. Evaluation of shallow groundwater contamination and associated human health risk in an alluvial plain impacted by agricultural and industrial activities, mid-west China. Expos. Health. 8 , 311–329 (2016).

Wu, L., Zhang, X. & Ju, H. Amperometric glucose sensor based on catalytic reduction of dissolved oxygen at soluble carbon nanofiber. Biosens. Bioelectron. 23 , 479–484 (2007).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

South African National Standard (SANS). 241-1: Drinking Water, Part 1: Microbiological, Physical, Aesthetic and Chemical Determinants. 241-2: 2015 Drinking Water, Part 2: Application of SANS 241-1 (2015).

Department of Water Affairs and Forestry (DWAF). South African Water Quality Guidelines (second edition). Volume 1: Domestic Use, (1996).

Drake, M.J. & Stimpfl, M. Water matters. In Lunar and Planetary Science Conference , Vol. 38, 1179 (2007).

Kumpel, E. & Nelson, K. L. Intermittent water supply: prevalence, practice, and microbial water quality. Environ. Sci. Technol. 50 , 542–553 (2016).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The safe water system: Safe storage of drinking water. Accessed from CDC Fact Sheet on 30/01/2022 (2012).

Hashmi, I., Farooq, S. & Qaiser, S. Chlorination and water quality monitoring within a public drinking water supply in Rawalpindi Cantt (Westridge and Tench) area, Pakistan. Environ. Monit. Assess. 158 , 393–403 (2009).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Onyango, A. E., Okoth, M. W., Kunyanga, C. N. & Aliwa, B. O. Microbiological quality and contamination level of water sources in Isiolo country in Kenya. J. Environ. Public Health . 2018 , 2139867 (2018).

Gwimbi, P., George, M. & Ramphalile, M. Bacterial contamination of drinking water sources in rural villages of Mohale Basin, Lesotho: Exposures through neighbourhood sanitation and hygiene practices. Environ. Health Prev. Med. 24 , 33 (2019).

Karikari, A. Y. & Ampofo, J. A. Chlorine treatment effectiveness and physico-chemical and bacteriological characteristics of treated water supplies in distribution networks of Accra-Tema Metropolis, Ghana. Appl. Water Sci. 3 , 535–543 (2013).

Article ADS CAS Google Scholar

Thompson, T., Sobsey, M. & Bartram, J. Providing clean water, keeping water clean: An integrated approach. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 13 , S89–S94 (2003).

Cronin, A. A., Breslin, N., Gibson, J. & Pedley, S. Monitoring source and domestic water quality in parallel with sanitary risk identification in Northern Mozambique to Prioritise protection interventions. J. Water Health 4 , 333–345 (2006).

Edokpayi, J. N., Enitan, A. M., Mutileni, N. & Odiyo, J. O. Evaluation of water quality and human risk assessment due to heavy metals in groundwater around Muledane area of Vhembe District, Limpopo Province, South Africa. Chem. Cent. J. 12 , 2 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Edimeh, P. O., Eneji, I. S., Oketunde, O. F. & Sha’Ato, R. Physico-chemical parameters and some heavy metals content of Rivers Inachalo and Niger in Idah, Kogi State. J. Chem. Soc. Nigeria 36 , 95–101 (2011).

Rahmanian, N., et al . Analysis of physiochemical parameters to evaluate the drinking water quality in the State of Perak, Malaysia. J. Chem. 1–10. Article ID 716125 (2015).

WHO/FAO. Diet, Nutrition, and the Prevention of Chronic Diseases (World Health Organisation, Geneva, 2003).

Meride, Y. & Ayenew, B. Drinking water quality assessment and its effects on resident’s health in Wondo genet campus, Ethiopia. Environ. Syst. Res. 5 , 1 (2016).

Mapoma, H. W. & Xie, X. Basement and alluvial aquifers of Malawi: An overview of groundwater quality and policies. Afr. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 8 , 190–202 (2014).

Soylak, M., Aydin, F., Saracoglu, S., Elci, L. & Dogan, M. Chemical analysis of drinking water samples from Yozgat. Turkey Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 11 , 151–156 (2002).

Munteanu, C. & Iliuta, A. The role of sodium in the body. Balneo Res. J. 2 , 70–74 (2011).

Strazzullo, P. & Leclercq, C. Sodium. Adv. Nutr. 5 , 188–190 (2014).

Pohl, H. R., Wheeler, J. S. & Murray, H. E. Sodium and potassium in health and disease. Met. Ions Life Sci. 13 , 29–47 (2013).

Muhammad, S., Shah, M. T. & Khan, S. Health risk assessment of heavy metals and their source apportionment in drinking water of Kohistan region, northern Pakistan. Microchem. J. 98 , 334–343 (2011).

Inan-Eroglu, E. & Ayaz, A. Is aluminum exposure a risk factor for neurological disorders?. J. Res. Med. Sci. 23 , 51 (2018).

Milman, N. Prepartum anaemia: Prevention and treatment. Ann. Hematol. 87 , 949–959 (2008).

Jamshaid, M., Khan, A. A., Ahmed, K. & Saleem, M. Heavy metal in drinking water its effect on human health and its treatment techniques—a review. Int. J. Biosci. 12 , 223–240 (2018).

Tagliabue, A., Aumont, O. & Bopp, L. The impact of different external sources of iron on the global carbon cycle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 41 , 920–926 (2014).

Mohod, C. V. & Dhote, J. Review of heavy metals in drinking water and their effect on human health. Int. J. Innov. Res. Technol. Sci. Eng. 2 , 2992–2996 (2013).

Bhowmik, D., Chiranjib, K. P. & Kumar, S. A potential medicinal importance of zinc in human health and chronic. Int. J. Pharm. 1 , 05–11 (2010).

Mahmud, M. A. et al. Low temperature processed ZnO thin film as electron transport layer for efficient perovskite solar cells. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells. 159 , 251–264 (2017).

Rajan, S. & Ishak, N. S. Estimation of target hazard quotients and potential health risks for metals by consumption of shrimp ( Litopenaeus vannamei ) in Selangor, Malaysia. Sains Malays. 46 , 1825–1830 (2017).

Bamuwamye, M. et al. Human health risk assessment of heavy metals in Kampala (Uganda) drinking water. J. Food Res. 6 , 6–16 (2017).

Saleh, H. N. et al. Carcinogenic and non-carcinogenic risk assessment of heavy metals in groundwater wells in Neyshabur Plain, Iran. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 190 , 251–261 (2019).

Tani, F. H. & Barrington, S. Zinc and copper uptake by plants under two transpiration rates Part II Buckwheat ( Fagopyrum esculentum L.). Environ. Pollut. 138 , 548–558 (2005).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the University of Venda Health, Safety and Research Ethics’ Committee, the Department of Water affairs, Limpopo province and Vhembe district Municipality for granting the permission to conduct this study. We also thank all the respondents from the selected households in Lufule community.

The study was funded by the Research and Publication Committee of the University of Venda (Grant number: SHS/19/PH/14/1104).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Public Health, School of Health Sciences, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, 0950, South Africa

N. Luvhimbi, T. G. Tshitangano, J. T. Mabunda & F. C. Olaniyi

Department of Hydrology and Water Resources, School of Environmental Sciences, University of Venda, Thohoyandou, 0950, South Africa

J. N. Edokpayi

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

L.N. and J.N.E. conceptualized the study, L.N. collected and analysed the data, T.G.T., J.T. M., and J.N.E. supervised the data collection and analysis. F.C.O. drafted the original manuscript, J.N.E. reviewed and edited the original manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to F. C. Olaniyi .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Luvhimbi, N., Tshitangano, T.G., Mabunda, J.T. et al. Water quality assessment and evaluation of human health risk of drinking water from source to point of use at Thulamela municipality, Limpopo Province. Sci Rep 12 , 6059 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10092-4

Download citation

Received : 02 December 2021

Accepted : 30 March 2022

Published : 11 April 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-10092-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

- Boris Lora-Ariza

- Adriana Piña

- Leonardo David Donado

Scientific Reports (2024)

Characterization of Natural Zeolite and Determination of its Ion-exchange Potential for Selected Metal Ions in Water

- G. M. Wangi

- P. W. Olupot

- R. Kulabako

Environmental Processes (2023)

Relations between personal exposure to elevated concentrations of arsenic in water and soil and blood arsenic levels amongst people living in rural areas in Limpopo, South Africa

- Thandi Kapwata

- Caradee Y. Wright

- Angela Mathee

Environmental Science and Pollution Research (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Water Inequality

Lack of safe drinking water and adequate sanitation effects countries around the globe.

Anthropology, Biology, Health, Conservation, Geography, Human Geography, Social Studies

Water Bucket Woman

A woman carries buckets full of water in a small village in northern India.

Photograph by Sean Gallagher

More than 70 percent of Earth’s surface is covered in water, yet lack of access to clean water is one of the most pressing challenges of our time. As of 2015, 29 percent of people globally suffer from lack of access to safely managed drinking water. More than double that number are at risk for water contamination from improper wastewater management. Poor water quality affects various aspects of society, from the spread of disease to crop growth to infant mortality. In some regions of the world, lack of sanitation infrastructure , water treatment facilities, or sanitary latrines lead to dire clean water crises. In several countries around the world, a major contributor to water contamination is open defecation—the practice of using fields, forests, lakes, rivers, or other natural, open areas to deposit feces. Almost one billion people worldwide still practice open defecation rather than using a toilet. It is particularly common in South Asian countries like India and Nepal, where it is practiced by about 32 percent of people in the region. A landlocked country in the Himalayas, Nepal has access to clean water from mountain rivers, but over 20 percent of the population lives below the poverty line. In a disturbing study, 75 percent of drinking water samples from schools in Nepal were contaminated with fecal bacteria. While open defecation is most common in rural communities, it still occurs in areas with sanitation access, indicating a need for awareness campaigns to teach the dangers of the practice. Moreover, pollution from open defecation is further complicated by contamination from natural disasters such as recurring floods. In sub-Saharan Africa, the proportion of the population practicing open defecation is slightly smaller—around 23 percent—but 40 percent of the population lacks safe drinking water. Moreover, the gender inequality in this region is more prominent than in South Asia. In sub-Saharan Africa, more than 25 percent of the population must walk 30 minutes or more to collect water, a burden that falls on women and girls the vast majority of the time. This trend of women tasked with the responsibility of water collection spans many developing nations and takes critical quality time away from income generation, child care, and household chores. Moreover, Africa has a high risk for desertification , which will reduce the availability of fresh water even further, and increase the threat of water inequality in the future. While South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa represent the largest percentage of people that lack access to safe drinking water, the water crisis is not limited to these areas, nor is it limited to developing countries. For example, the Arctic nations are deemed developed, but several suffer from water and sanitation challenges. Alaska in the United States, Russia, and Greenland all contain rural areas that lack safe in-house water and sanitation facilities. Some people living in these areas must not only carry their own water into their homes, they must also remove human waste themselves, collecting it and hauling it out of the home. The process is time consuming and risks contamination of household surfaces and drinking water. Furthermore, hauling water into homes is physically demanding, and storage capacity is limited, so households often function on inadequate water supplies. Several studies have connected these water-quality constraints with high disease rates in Arctic communities. Even in the United States and many nations in Europe, where advanced wastewater treatment facilities and expansive pipelines supply quality water to both cities and rural areas, poor system maintenance, infrastructure failures, and natural disasters reveal the very serious effects of poor water quality (even short-term) on developed nations. In a recent example, drinking water in Flint, Michigan, was inadequately treated beginning in 2014, and residents bathed in, cooked with, and drank water with toxic lead levels. Additionally, some communities in the contiguous United States chronically lack clean water and sanitation. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), in the Navajo Nation, the largest Native American reservation in the United States, almost 8,000 homes lack access to safe drinking water, and 7,500 have insufficient sewer facilities. Luckily, global organizations are committed to addressing the water-quality crisis. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development from the United Nations tackles water inequality within one of its seventeen priority goals, to “ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all.” This initiative is a continuation of the United Nations’ Millennium Development Goals from the 2000s, which also included goals to reduce the portion of the population that lacked access to infrastructure for quality water and sanitation. These goals have resulted in access to improved sources of drinking water for more than 90 percent of the world—and the 2030 Agenda seeks to continue to improve these numbers alongside greater strides in the area of sanitation. National Geographic Explorers are also committed to global water equality and are combatting these issues with diverse methods. Explorer Sasha Kramer is helping to implement sustainable sanitation practices in Haiti by recycling human waste into soil. Explorer Ashley Murray develops economically advantageous approaches to improving water quality in Ghana, exploring next-generation technologies and new business models to make waste management profitable. Explorer Alexandra Cousteau, granddaughter of the late and legendary Jacques Cousteau, uses storytelling and digital assets to educate people around the globe about the importance of water quality. Moreover, complementing these examples and the many other Explorer-driven efforts dedicated to improving water quality, Explorer Feliciano dos Santos uses music to educate remote villages in Mozambique about the importance of sanitation and hygiene.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

January 26, 2024

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.