Study guide

Postgraduate studies in blue resources for the blue economy.

The objective of this Joint International Postgraduate programme is to offer an add-on learning opportunity for students to be prepared for the rapidly evolving demands of the blue economy sector. The Blue Economy can be defined as activities related to oceans, seas and coasts for economic growth, improved livelihoods and jobs.

The Blue Economy can be defined as activities related to oceans, seas and coasts for economic growth, improved livelihoods and jobs. It encompasses a wide range of interlinked established and emerging sectors and is the subject of numerous strategic policy and operational initiatives at local, regional, national and international levels. The EU Blue Economy Report 2020 (EU Commission, 2020) provides an overview of the EU Blue Economy. With a turnover of €750 billion in 2018, the EU blue economy employs ~5 million people. Many EU partners face significant challenges in sectors such as coastal and marine tourism, fisheries, aquaculture and marine food as a result of immediate and medium-term consequences of the coronavirus pandemic. That said, the scale and diversity of the sector also presents a considerable opportunity to respond to immediate and longer-term societal challenges around climate change, sustainability, food security, renewable energy and the UK’s departure from the EU.

In response, the University of Ghent and the Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology have joined forces and developed one of the few programmes specifically aimed at the Blue Economy: Postgraduate Studies in Blue Resources for the Blue Economy. This course is aimed at very diverse profiles, from engineers to people with a financial or legal background. Everyone who has obtained a Master’s degree and is interested in pursuing a career in the Blue Economy can initially enroll in this postgraduate course. People already active in the field and looking to expand their knowledge and skills are also eligible. In addition, this programme offers a very flexible trajectory with a focus on online learning and blended working formats. During the course, contact with the industry is a key element. Students will have the opportunity to come into contact with relevant stakeholders within the industry whilst following workplace-based training. This postgraduate course aims to offer the students all the necessary tools needed to fully prepare for the rapidly evolving demands of the blue economy sector.

The admission requirements depend on your prior education (type of degree, country of issue etc.) or additional experience.

The programme is structured around the following main components:

All students entering the programme will get a shared component dealing with the Blue Economy containing 2 courses.

Emerging issues in the Blue Economy – 3 ECTS : this course will give a broad overview and insights in the different sectors of the Blue Economy in an international context. This course will be organized in a blended way with an on-site opening event in Ostend, Belgium (10-14 January 2022) and a digital group project.

Skills and practices in Blue entrepreneurship – 6 ECTS : this course will introduce students in several skills which are relevant for a Blue entrepreneurial mindset. This set course will be an essential preparation for the next section of the programme.

In the second part of the programme students will on an individual basis get familiar to the roles and professions in the Blue BioEconomy. They will do this via an internship and a follow-up interaction in which they share and evaluate the experiences in a broader context. Components in this module are:

Research or business-internship in the Blue Economy – 20 ECTS : individual internship (in Belgium, Ireland or other country of choice) in a company active in and relevant for the Blue (Bio)Economy. During this internship students will define the skills they wish to learn in close collaboration with the internship site and via a close monitoring system evaluate whether or not they gained this knowledge. People already active in the marine industry also have the option to undertake their internship at their current employer - in agreement with the supervisor and mentor - and engage in an interesting research question/project.

The Blue Economy in Practice – 3 ECTS : this course follows up on the internship and will focus on (1) exchanging the experiences with peers, (2) identify challenges and weaknesses in the internship setting and (3) develop ideas for future developments, collaborations, improvements. This course consists of an on-site closing event in Galway, Ireland (5-8 September 2022).

Transferable skills for the Blue Economy – 6 ECTS : The third part of the study programme allows students to study one or more additional courses from a combined list available from UGent and GMIT. As students will have a diverse background the additional training needs may largely differ. Via an individual skills-gaps analysis will it be possible to identify the individual skills gaps and propose courses which may answer these needs. At least 6 ECTS of courses in total should be taken in this module.

Study programme quality

Quality assurance.

At Ghent University, we strive to educate people who dare to think about the challenges of tomorrow. For that purpose, we provide education that is embedded in six strategic objectives : Think Broadly, Keep Researching, Cultivate Talent, Contribute, Extend Horizons, Opt for Quality. Ghent University continuously focuses on quality assurance and quality culture. The Ghent University's quality assurance system offers information on each study programme’s unique selling points, and on its strengths and weaknesses with regard to quality assurance.

More information:

Ghent University's Education Objectives

Quality Assurance at Ghent University

- Open access

- Published: 17 May 2021

Challenges of the Blue Economy: evidence and research trends

- Rosa María Martínez-Vázquez ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4875-754X 1 ,

- Juan Milán-García 1 &

- Jaime de Pablo Valenciano 1

Environmental Sciences Europe volume 33 , Article number: 61 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

44k Accesses

59 Citations

53 Altmetric

Metrics details

The Blue Economy is a recent field of study that encompasses economic activities that depend on the sea, often associated with other economic sectors, including tourism, maritime transport, energy and fishing. Blue growth supports the sustainable growth of the maritime and marine sectors as the oceans and seas are engines of the global economy and have great potential for growth and innovation. This article undertakes a bibliometric analysis in the terms of Blue Economy (BE), Maritime Economy (MAE), Ocean Economy (OE), Marine Economy (ME), and Blue Growth (BG) to analyze the scientific production of this field of study. Analysis of the authors’ definitions of BE, BG, ME and OE provides interesting relationships divided into sustainability and governance; economics and ecosystem protection; industrial development and localization; and the growth of the ocean economy, with development as the central axis that encompasses them. The main contribution is to find out if there is a link between the BE and the CE through the keyword study.

The results show a significant increase in articles and citations over the last decade. The articles address the importance of different sectors of BE and the interest of governments in promoting it for the development of their national economies. Using bibliometric mapping tools (VOSviewer), it is possible to find possible links between concepts such as CE and BE through the BG and to visualize trending topics for future research. Nascent and future research trends include terms such as small-scale fisheries, aquatic species, biofuel, growth of the coastal BE, internationalization and blue degrowth (BD), the latter approaches aspects of BG from a critical perspective.

Conclusions

In conclusion, it highlights the need for alliances between the sectors that compose BG with the incorporation of the CE in order to achieve a sustainable BE in both developed and developing countries. Through the keyword analysis it is shown that the BG strategy is the bridge between the BE and the CE. The CE presents itself as a promising alternative that could mitigate tensions between stakeholders who support both growth and degrowth positions.

Throughout history, the sea has always been present in the economic activities of all civilizations as a food resource, a means of transportation and commercial trade. In recent years the term Blue Economy (BE) has become a concept closely related to maritime resources and developed economies in the oceans. Its growing expansion and the emerging needs of a circular economy (CE) herald challenges in both new and established treatments and materials [ 30 ]. CE is understood as an economic model oriented towards the elimination of waste generated, efficient use of resources, recycling and recovery [ 79 , 117 ].

The BE aims to promote economic growth, improve life and social inclusion without compromising the oceans’ environmental sustainability and coastal areas since the sea’s resources are limited and their physical conditions have been harmed by human actions [ 40 ].

The first appearance of the term BE dates back to 2009, at the congress of the Senate Committee on Commerce, Science and Transportation of the United States. The importance of the BE for the USA’s overall economy, the excellent business opportunities it provides, and the concerns about climate change are excellent opportunities for new blue jobs in renewable energy [ 19 ]. In that same year, the International Symposium on Blue Economy Initiative for Green Growth in Korea took place, where “ the concept of using ocean resources in a way that respects the environment can evaluate how both business activity models and new technologies satisfy economic and environmental conditions, contributing to the sustainability of these resources ” [ 62 ].

Subsequently, Pauli [ 94 ], a leading proponent of the BE’s economic model, published a book entitled, “The Blue Economy” [ 7 , 16 , 45 , 110 ] which proposed it as a model based on technological innovation to supply products at low cost, promote local job creation and a model that is respectful of the environment and competitive in the markets.

At the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development held in Rio de Janeiro in 2012, the oceans were deemed to be priority areas, with some initial objectives being proposed such as the “sustainable consumption and production patterns”, food security, sustainable energy for all and disaster risk reduction and resilience [ 124 ].

Undoubtedly, ocean resources generate numerous benefits to the world economy and offer essential opportunities for transportation, food production, energy, mineral extraction, biotechnology, human settlement in coastal areas, tourism and recreation, and scientific research [ 64 ].

In academic research, a literature review on the BE also needs to include similar concepts. Lee et al. [ 74 ] state that “ the term BE has been used in different ways and similar terms such as “ocean economy” or “marine economy” are used without clear definitions. ” At the same time, when analyzing other articles that address BE, it was observed that ocean economy (OE), marine economy (ME), and blue growth (BG) were also used as synonyms [ 64 , 121 ]. Table 1 shows some of the definitions of these terms.

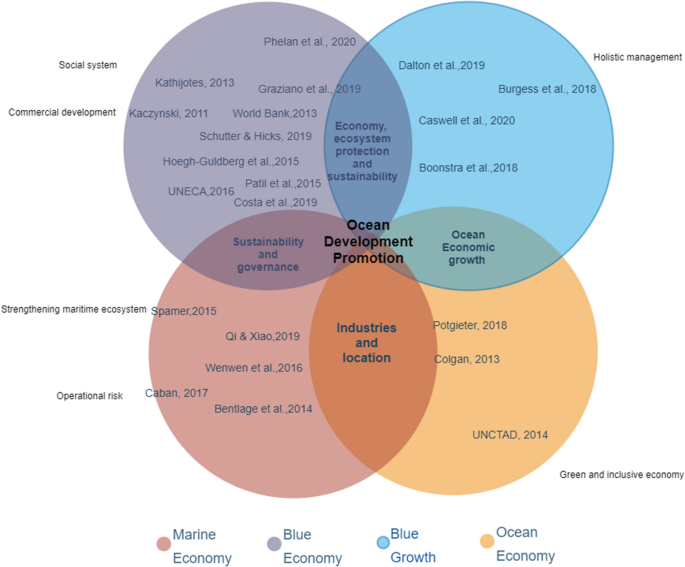

Figure 1 presents an analysis of the similarities and differences of the above definitions, where each color of the circumference represents a concept (BE, BG, ME and OE) and within it the authors are positioned. The most interesting finding arises in the intersections, with the common element for BE and BG being the economy and the protection of marine ecosystems to ensure sustainability, ME and OE share industry development and location, in BE and ME we find governance and sustainability and finally BG and OE cooperate in the growth of the ocean-based economy. In relation to the differences, they are placed outside the quadrant, with aspects pointing to a social and complex system, a green and inclusive economy, as well as the existence of operational risks.

(Resource: own compilation)

Comparative analysis between authors’ definitions

The central point is ocean development promotion as a sign of progress and economic, political, social and cultural growth without losing the focus on sustainability.

It is important to highlight that the concept of BE gives rise to two conflicts of interest. On the one hand, those linked to economic growth and development, and on the other, those linked with safeguarding and protecting the ocean’s resources. Kathijotes [ 67 ] states that the objective of BE models is to transfer resources from scarcity to abundance and address the issues that cause environmental problems.

For this reason, it is necessary to propose solutions that take advantage of all available opportunities and analyze the threats to the OE. Lee et al. [ 74 ] link the BE and the UN sustainable development goals (SDGs) and conclude that the objectives that are linked to the BE are: underwater life (14), land ecosystems (15); peace, justice, and stable institutions (16) and alliances to achieve the objectives (17). Linking BE with SDGs is challenging on the basis that the common element of both is in objective 14 [ 59 , 88 , 130 ]. In relation to hot spots, firstly, the starting point for achieving the SDGs is not homogeneous, with large differences between developed and developing countries [ 58 , 61 ] due to the economic, political, social, cultural and environmental context [ 51 ]. Secondly, there are areas of conflict mainly around divergent views on the legitimacy of different sectors as components of BE, in particular carbon-intensive industries such as oil and gas and the emerging deep-sea mining industry [ 131 ], as well as large fisheries versus those coastal areas where artisanal fisheries are in danger of extinction [ 109 ].

Furthermore, the increase in human activity, in the form of new or intensified uses, such as the generation of renewable marine energy, exert greater influence and cause conflicts between BE sectors [ 56 ].

In 2012 the European Union implemented its BG strategy and established subsectors within the field of the BE [ 41 , 96 ]. The BG Strategy breaks down the BE into five main sectors: Biotechnology, Renewable Energy, Coastal and Maritime Tourism, Aquaculture and Mineral Resources, and integrates other sectors such as fishing, transportation, offshore oil and gas extraction, and ship construction and repair.

Biotechnology presents excellent opportunities to produce natural products with possible applications in the food and pharmaceutical sectors [ 105 , 119 ]. It is a recent and developing sector that is part of the bioeconomy, the latter developing and using renewable biological resources from the land and sea. For example, the cultivation of seaweed is expected to provide sustainable biomass that facilitates the development of the marine bioeconomy through BG [ 43 ] and is considered an industrial benchmark for achieving a competitive, circular, and sustainable economy that is less dependent on fossil carbon [ 9 ].

Renewable wind energy from marine sources and the conversion of thermal energy from the ocean is increasingly present at the global ocean level [ 126 , 129 ]. Novel hybrid robust/stochastic approaches are used to participate in the electricity market, including renewable energy procurement through large consumer purchases that respond to the energy demands of wind turbines voyer (WT), photovoltaic systems (PV), bilateral contracts (BCs), and micro-turbines (MTs), and energy storage systems (ESS) [ 1 ]. Other strategies focus on the optimal programming of electrical energy consumption in multiple cooling systems [ 108 ] or models based on heat and energy centers [ 70 ].

Tourism has played a decisive role in developing many island economies, triggering other activities to obtain local economic returns. Similarly, aquaculture and fisheries have contributed to the economic development of certain regions without jeopardizing access to essential resources such as small-scale fisheries [ 15 , 39 , 109 ]. The exploitation and extraction of offshore oil and gas is a reality in many economies around the world wherein nations must weigh the economic benefits against the negative impact it may have on living marine resources [ 78 , 92 , 131 ].

Globally, shipping is the primary means of supplying raw materials, consumer goods, and energy, becoming a facilitator of world trade and contributing to economic growth and employment, both at sea and on land [ 81 ]. In addition, the shipbuilding industry provides real added value to numerous coastal communities [ 114 ].

Through bibliometric analysis, this study’s main objective is to explore the evolution of worldwide scientific production on BE between 1979 and 2020. The purpose is also to identify those concepts that are related to BE in order to subsequently carry out the study of keywords and establish future research trends.

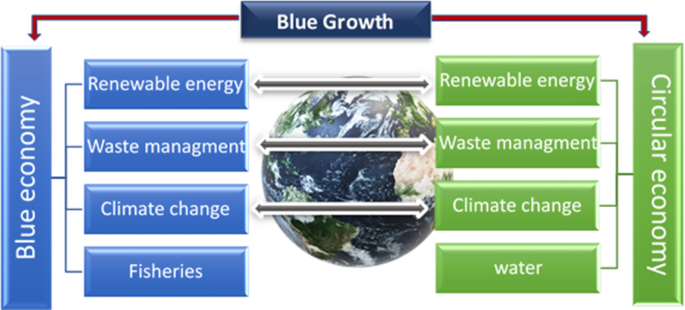

Its main contribution is the assimilation of the BE into the CE since both are key to supporting BG and guaranteeing the sustainability of economic activities developed within the blue context. BE encompasses activities related to renewable energy use, waste management, climate change, fisheries and tourism, where the concept of economic circulation (based on recycling, extension, redistribution and manufacturing) can be integrated, moving from a linear economy to an economy that makes the most of waste through circular flow [ 60 , 112 , 133 ]. Analyzing the possible connections, we start from the study carried out by Ruiz-Real et al. [ 107 ], referring to the analysis of the global dynamics of the CE, where trend words related to renewable energy, climate change and waste management are located, finding an explicit link with almost all of the activities promoted by the BE shown in Fig. 2 . Furthermore, although there is no visible link on the fisheries and water issue in the BE and CE, it should be mentioned that fisheries depend on water, as their life cycle depends on this natural environment and both its conditions (quality, temperature, salinity) and its proper management influence the sustainability and conservation of marine species [ 36 , 106 ].

Analysis of relationships between BE and CE

An important aspect relates to the conflict between the interest groups of BD versus the economic development proposed by both the BE and the BG. Thus, the CE presents itself as a mediator between growth, economic development and employment while extending resource availability and reducing environmental and social pressures.

Methodology

Bibliometry offers useful results from the authors’ production in a field of research, trends, the most cited articles, and the concentration of documents in impact journals [ 63 ].

The first step was to select the terms through a prior review of those economies linked to the seas and oceans, with BE, BG, ME, and OE being the most representative terms.

The next step involved locating and extracting data on all the documents in the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection that contain the terms established in the search criteria in order to visualize the behavior of scientific production over time, providing high-quality data and a complete description that facilitates data processing and for the broad recognition it has obtained in the scientific community [ 89 , 98 ]. For this study, the WoS database was selected. This database is widely recognized for gathering reliable and multidisciplinary research, with studies recommending its use due to the high proportion of exclusive journals [ 83 ].

A similar search query was carried out on the Scopus database using the same criteria to guarantee the data’s completeness. The results were similar to those obtained from WoS [ 44 , 53 , 80 ].

The data was then processed to analyze the number of articles published per year, the number of citations, and their h-index. Bibliometric analysis, the study of the scientific activity of authors, has been used to prepare this article and has been used in various areas.

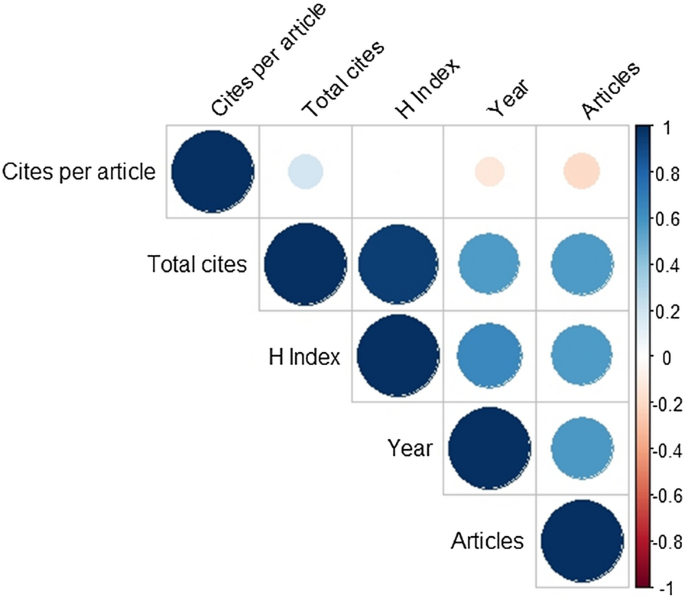

Figure 3 depicts the descriptive statistical analysis of the main variables: cites per article, total cites, h-index, year, and articles. The matrix indicates the correlation between them (the closer to 1, the stronger the correlation; if the values are closer to − 1, there is an inverse correlation between variables, while if there is a zero value, there is no correlation). In the present case, the articles variable is highly correlated with the total of citations, h-index, and years. In contrast, there is an inverse correlation with the variable cites per article and year.

Correlation matrix of main variables

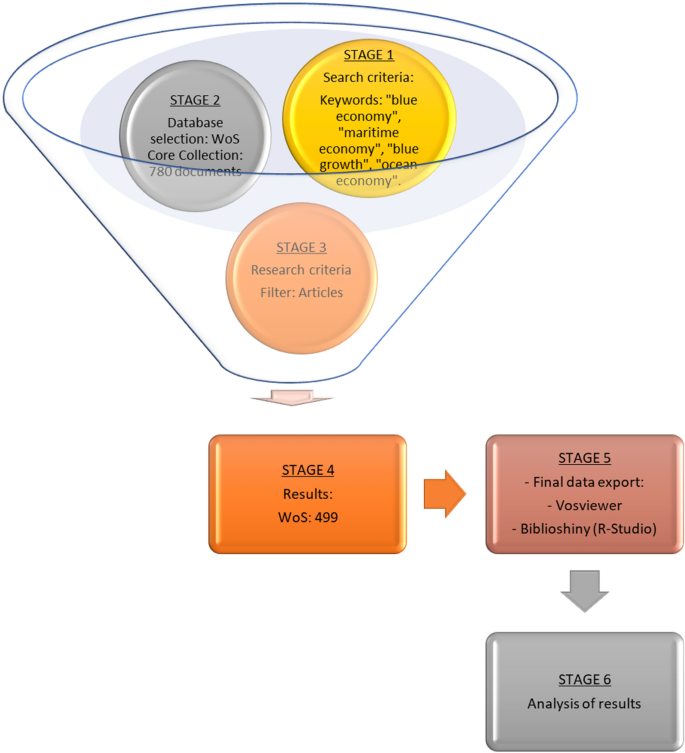

In this work, the number of articles, citations, citations per article, and h-index, the most relevant countries, institutions, and authors are studied. The keywords are also taken into account in order to discover new lines of research. A database search has been carried out, filtering by topic in the title, the abstract, author keywords, and Keywords Plus. The search for the keywords was carried out using the terms: “blue economy” or “ocean economy” or “blue growth” or “maritime economy” or “marine economy.” In the next stage, 780 results were obtained, from which articles were filtered, leaving 499 articles to be processed and analyzed in the fourth stage. The results were then filtered to include only articles as many of them have been published in journals with an impact factor in Journal Citation Reports (JCR). This indicator is highly regarded and valued by organizations that evaluate research activity, guaranteeing a strict review process and high-quality results [ 32 , 47 , 82 ].

Lastly, once the document search was filtered to include only articles, the data were exported and processed using two tools: Vosviewer and Biblioshiny. In this way, clusters can be created by downloading information from the Web of Science database.

The VOSviewer program offers the basic functionality necessary to visualize bibliometric networks, citation links between publications, collaboration between researchers, and co-occurrence links between scientific terms [ 128 ]. According to a logical bibliometric workflow, the Bibliometrix tool, developed in the statistical and graphical language R, is also used to add weight to the study. R is highly extensible as it uses a functional, object-oriented programming language, and therefore it is relatively easy to automate parsing and create new functions. It is utilized to create graphs for three metrics at different levels: sources, authors, and documents, and analyzing knowledge structures at the conceptual, intellectual and social level [ 5 ] (Fig. 4 ).

(Source: own compilation based on WoS)

The data collection process

Descriptive analysis

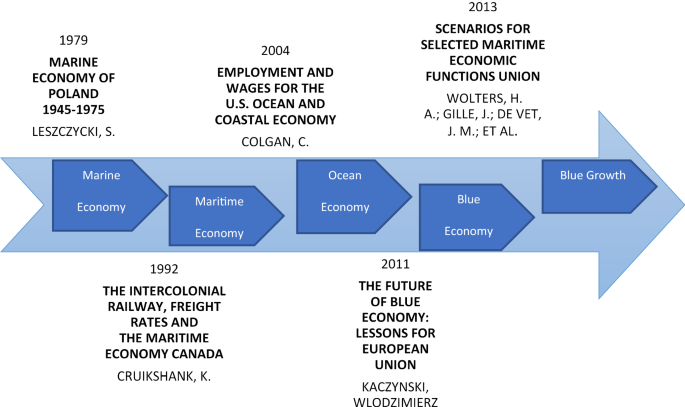

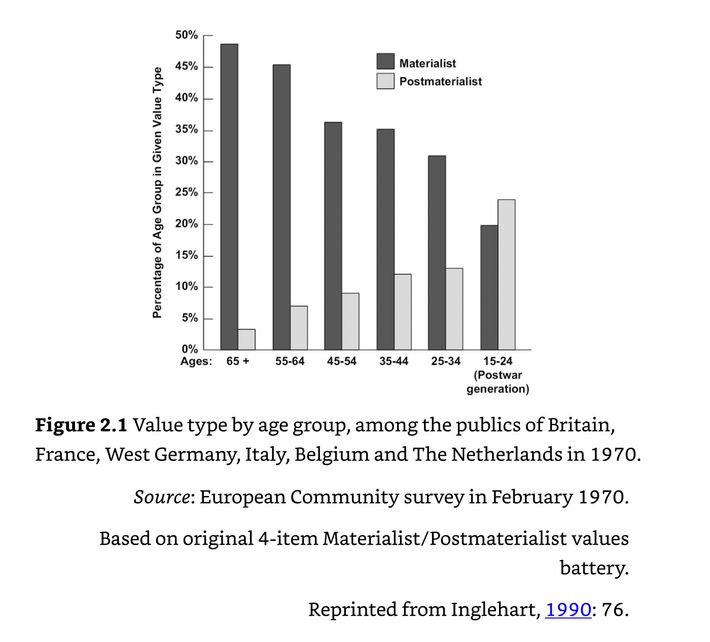

Figure 5 represents a descriptive analysis of the terms ME, OE, BE, and BG, making a note of the chronological order of the articles when these concepts first appeared.

(Source: own compilation based on WoS data)

Timeline of first published articles related to BE, BG, ME, and OE

The first mention of ME appeared in 1979 in the article entitled “ Marine Economy of Poland 1945–1975 ”. It addressed the growth of two port complexes located on the Polish Baltic Sea coast, Gdansk-Gdynia and Szczecin-Swinoujscie, pointing to the important economic activities in the area such as the export of coal and coke, ships, minerals, cereals, gypsum, rolled steel products, wood, cement, and food. It also pointed to tourism development along the coastal regions that required environmental protection [ 75 ]. Later, in 1992, the article “ The Intercolonial Railway, Freight Rates and The Maritime Economy in Canada ” stated that this infrastructure was a crucial piece in the history of MAE development and a transport link between the maritime islands and the center from Canada [ 31 ].

In 2004 the article “ Employment and Wages for the U.S. Ocean and Coastal Economy ” was published on the subject of OE and performed a preliminary analysis of the United States’ coastal and ocean economy between 1990 and 2001 to prepare coherent national estimates of economic values, based on economic and other measures related to the coasts and the oceans [ 27 ].

The article “ The Future of Blue Economy: Lessons for European Union ” marked the beginning of research on BE and made some preliminary considerations about the growing convergence of economic, social, technical, and environmental factors that contributed to generating new opportunities in the world’s oceans. Furthermore, thanks to the cooperation between European ocean industries and government institutions, together with the training of various experts, they became the epicenter of applying the European BE at sea [ 64 ].

In 2013 the BG Strategy, “ Scenarios for Selected Maritime Economic Functions Union ,” appeared and examined the usages of the scenarios of the BG project. It aimed to develop the maritime dimension of the Europe 2020 strategy, with a 15-year horizon (2025–2030). In this regard, the scenarios were understood and developed in two ways: the micro-future scenarios and the general scenarios [ 136 ].

Scientific production analysis

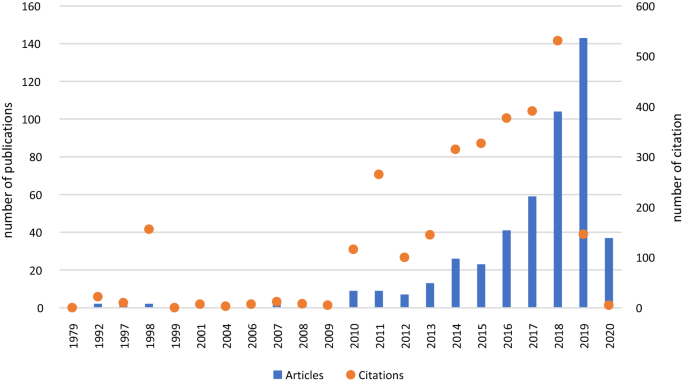

Table 2 shows the evolution of scientific production in the period (2020–1979) by the number of articles, citations, citations per article (average), and the annual h-index.

In 2010, there was an increase in the number of articles and citations resulting from the article, “ The importance of estimating the contribution of the oceans to national economies ” by Kildow and McIlgorm [ 71 ]. The authors stated that the oceans were in trouble and experienced changes that could compromise life on both the sea and the land, affecting the economy and the environment.

The year 2018 stands out for the number of citations, reaching its maximum value of 531 (Fig. 6 ). The most cited article, “ Blue growth: savior or ocean grabbing? ” questions political proposals and places them within the framework of the broader debates on the neo-liberalization of nature [ 8 ]. Other authors with a high number of citations address BG, tracing its roots to the conceptualization of sustainable development under the title “ What is blue growth? The semantics of “Sustainable Development” of marine environments ” [ 37 ]. The authors further manifest the complexity of ocean systems, combined with data and capacity constraints, demanding a pragmatic management approach [ 17 ].

Evolution in the number of publications and citations

The most cited articles closely related to the terms “BE, BG, ME, and OE,” in addition to the authors, journal, date of publication, and total citations, are listed in Table 3 . Of note is the article by Silver et al. [ 118 ], with 89 citations, which addresses how BE became operational and how it was articulated in four factors: oceans as natural capital, good business, the integral part of the Pacific Small Island Developing States (SIDS) and small-scale fisheries livelihoods. The second-ranked article by Kildow and McIlgorm [ 71 ] addresses the importance of knowing the oceans so that governments can have proactive behaviors in response to the demands of the population and nature in coastal and ocean environments. The third-ranked article, “ BG: savior or ocean grabbing? ”, critically addresses the political proposals, which fail to envision the problems of the environment and climate change.

The remaining articles address the marine sector’s role in the national economy, the concept of BG in the marine environment, the integrated maritime policy, and platforms for harvesting marine renewable energy.

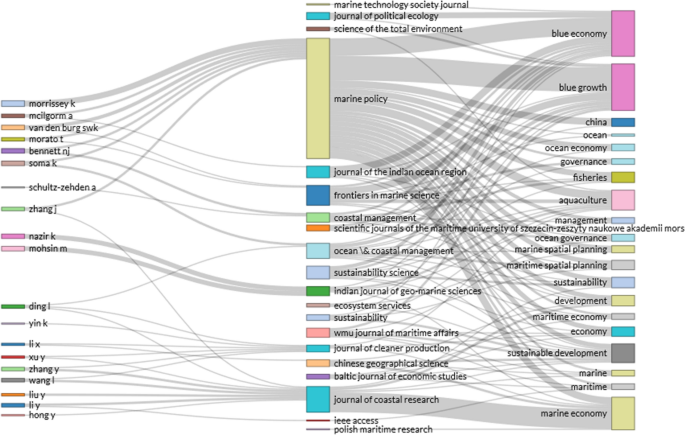

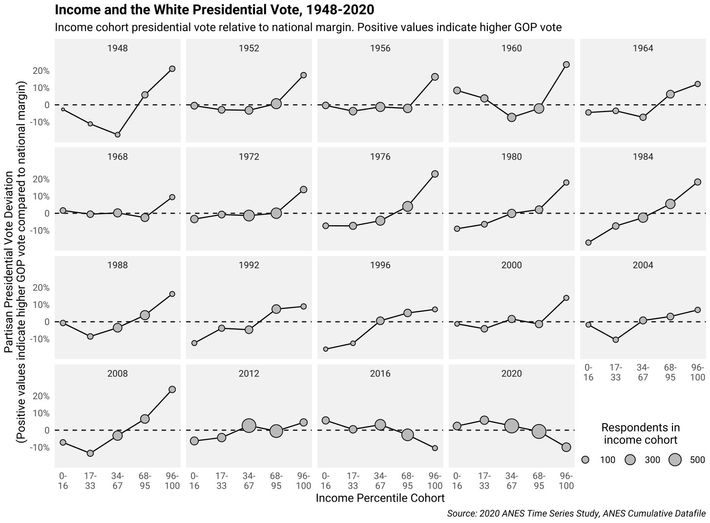

Figure 7 depicts the authors and their links to scientific journals and the most representative keywords. In this instance, Morrissey, McIlgorm, Van der Burg, Morato, Bennett, and Soma have published the greatest volume of articles in Marine Policy , the scientific journal with the highest impact and the greatest number of relevant keywords.

(Source: own compilation using biblioshiny)

Relationships between top authors, journals, and keywords

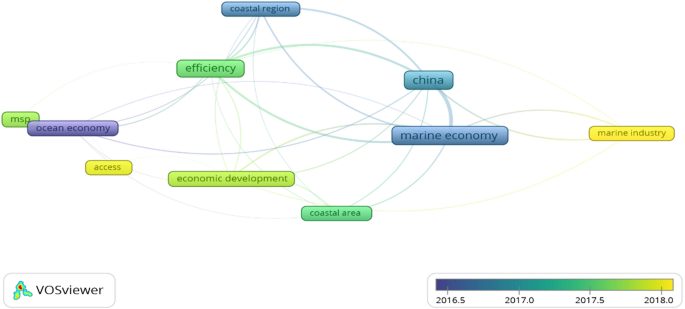

Analysis of keywords

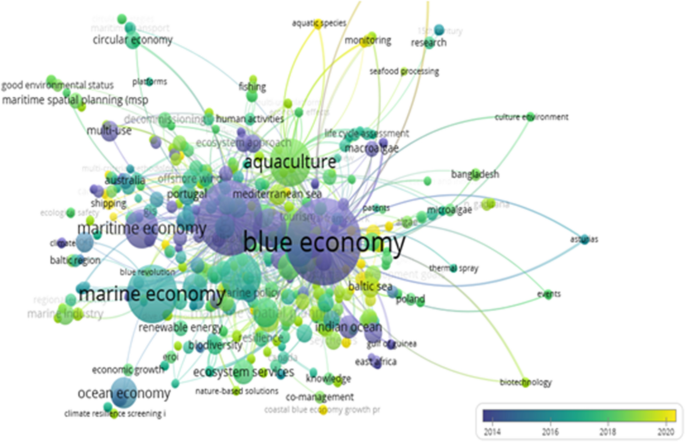

The keywords used in the article titles and abstracts are then analyzed according to their relevance and co-occurrence to create a co-occurrence map of all the terms used in the 499 selected articles (Fig. 8 ), using Vosviewer software. The minimum number of occurrences of a selected term is set at 25. Of the 12,858 terms found, 133 met the threshold and were included in the final analysis. From these results, a relevance score was calculated. The title and abstract fields were used to extract data. To extract the highest number of terms from the publications, the labels of the structured abstracts and the copyright statements are included.

Trends in keywords used in title and abstract

An analysis of the results reveals that the most productive period, between 2016 and 2020, has produced the most relevant terms. The ten most relevant terms are linked to maritime spatial planning, China, ME, OE, economic development, efficiency, and coastal areas. The most current terms have to do with the marine industry and access. In this sense, due to the boom in emerging marine industries and the support of nation states for marine technology, many Chinese universities have added specialties related to marine technology [ 76 , 134 ]. This industry has become a significant growth engine for China’s economic development [ 77 ]. Access refers to the exploitation of marine resources, coastal and fishing resources, spatial access to coastal communities, and the rights and property related to marine governance [ 2 , 11 , 69 , 109 ].

An analysis of the keywords identifies the most used terms and the most current trends related to the new areas of the concepts studied. The trend analysis depicted in Fig. 9 uses a color scale that goes from blue to yellow and categorizes the terms used in this field of study from the least to the most innovative in the period studied. Trends linked to concepts such as small-scale fishing, degrowth, aquatic species, biofuel, growth of the coastal BE, and internationalization are observed. These recent trends arising from the BE address the need to connect human and industrial activities that obtain their inputs from the sea by creating cooperative alliances at an international level, promoting sectors such as fishing, tourism, and energy. In addition, BE favors environmental sustainability since it uses renewable energy.

Trend analysis based on WoS data

The growth of the coastal BE can be linked to the government of Taiwan [ 20 , 116 , 141 ], which proposes a growth program for the coastal BE at the national level to promote ocean-related industries based on sustainable development by integrating different theoretical frameworks, methodological approaches, modeling and management of ecosystem frameworks. In general, farming the sea is based on artificial technologies and it is argued that by developing marine fish farming, it is possible to contribute to the transformation of capture fisheries by integrating the concept of BE [ 24 ]. As for the term BD is understood as the need to address the dominance of the BG by seeking greater integration between society and the oceans [ 38 ]. This requires the withdrawal of specific activities currently in the hands of large corporations, ending the exploitation of localized production. It aims the decommodification of labor and the recovery of the common goods to protect diversity. It is therefore necessary to make visible the risks of strategies based on economic development by suggesting a rethinking of the BE [ 52 , 65 ]. In this sense, the decrease is intended to criticize the traditional ideas of growth and sustainability by promoting an equitable reduction in production and consumption, along with a socially transformative vision [ 22 ]. The role of biofuels in the BE is gaining momentum. The research of Kaşdoğan [ 66 ] examines algae-based biofuel production systems designed on the high seas and integrated with wastewater treatment and carbon dioxide absorption processes to revitalize faith in biofuels in the BE.

Past research has addressed aspects of OE and ME from the perspective of the economic activities derived from the sea, specifically food catches, commercial transport, and the maritime industry [ 10 , 68 ]. Subsequently, the sustainability approach within the MAE was included [ 140 ] along with the specific characteristics, the type of risk, and the uncertain areas of this economy [ 35 , 46 , 111 ] and the continued development of integrated marine policies [ 21 , 34 ].

Despite the tremendous potential of ensuring the oceans’ sustainability, the growth of the BE presents some challenges. One of the most obvious obstacles is the lack of common and agreed-upon goals of BG. For some, BG revolves around maximizing economic growth derived from marine and aquatic resources [ 14 , 57 ]. However, for others, it means maximizing “inclusive” economic growth derived from marine and aquatic resources [ 37 , 54 , 101 , 120 ]. A real example of inclusion is in the Pacific Small Island Developing States (SIDS), which, like many developing countries, the issues of oceans, climate change, and energy are essential to poverty eradication. It is impossible to suppress poverty unless the health of ocean ecosystems is guaranteed and preserved as they are essential for food security, livelihoods, and economic [ 6 ]. Following the sustainability approach, the CE is building a strong emphasis on becoming a model that brings significant social, economic and environmental benefits [ 26 ].

The concepts of the “BE” and “BG” have been grouped together in a conceptual framework and are used as political discourse throughout the world as a way of representing the possible contribution to human well-being that both aquatic and marine spaces can make. Different interpretations of the concept of the BE are recognized. It is the very diverse definitions that generate a certain imprecision that allows the BE to encompass divergent visions and ideologies [ 25 ].

Fernández-Macho et al. [ 42 ] express the need to promote the BE to foster the progress and growth of maritime sectors, which can and should be sustainable. In this context, the development of integrated maritime policies is based on the belief that maritime zones can achieve higher growth rates, pointing out that the European Atlantic Arc could contribute to this BG.

Most activities related to the economic exploitation of the maritime environment carried out by humans do not conform to the notions of a “BE” since this economic exploitation does not often focus on a sustainable maritime environment [ 104 ]. Conflicts between sectors can emerge due to the nature of the resource itself (as it is a limited resource), its use and the commitment to develop efficient management of ocean resources, for example tourism versus offshore hydrocarbon extraction [ 72 ] or even within the same sector, with differences between the fishing fleet, fish farms and small-scale artisanal fisheries. Therefore, it is important to generate synergies between the different sectors that make up the BE in order to contribute to the economic development of the area and achieve the SDGs together, this being a local challenge (bottom-up strategy). Decisions could influence the sustainable growth of the BE in highly contested regions because both companies and political authorities are influenced by economic interests and by stakeholders that have power in decision-making. This could result in sustainable growth having a stronger influence than the effects of climate change, making it a more flexible and adaptable approach to policymaking that considers changing economic, social, and environmental realities [ 56 ].

Coastal communities are directly affected by the BE and the effective management of ocean resources for BG. Although the term ocean economics is often promoted as something new, there are historical analogies that can provide insights for contemporary planning and implementation of BG [ 99 ]. In this sense, thanks to the use and treatment of raw materials of marine origin, such as macroalgae, their multiple uses are essential for the efficient recovery of marine biomass [ 100 ].

While the protection of marine areas is considered a fundamental part of mitigating climate change, on a practical level, its success is overshadowed by the current expansion of offshore drilling for oil and gas [ 15 ]. The prospects for growth in the OE are promising because ocean industries address issues such as food security, energy security, and climate change [ 139 ]. On the other hand, there are discrepancies regarding the legitimacy of the different sectors that make up the BE, specifically the industries with high carbon intensity and the emerging seabed mining industry [ 132 ]. Numerous authors warn of the danger of privatizing ocean spaces through the BE [ 13 , 15 , 109 , 132 ].

Due to the current transformation of the oceans as places of integral industrialization, it is necessary to reflect on the experiences obtained from fishing and fisheries policies to understand and intervene in modernization processes and practices [ 4 ].

Another aspect to consider is climate change. Due to the negative consequences for coastal populations caused by rising sea levels, it is vital to develop defensive infrastructures. Since the turn of the century, the loss of landmass in the Greenland ice sheet has been accelerating [ 127 ]. It is a topic of great interest for both scientific research and public policy as sea level rise is influenced by regional and local factors, with coastal areas suffering the consequences of sea-level rise [ 3 , 49 , 50 , 91 , 115 , 123 ].

Changes in the balance of surface mass, relative to changes in solid ice discharge, are vitally important across the Arctic areas and will continue in the future [ 84 ]. For example, the Netherlands, a region crisscrossed by large rivers such as the Rhine, Meuse, and Scheldt, is protected by a network of levees. Approximately 59% of its territory is at risk of flooding, 26% is under the sea level and 29% can flood if the rivers overflow. According to the commission that manages the Delta Plan, which addresses the threat of water, a temperature increase of two degrees in the North Sea could mean a rise of between 1 and 2 m.

Scientific studies about New York City reveal that the sea level could rise by 2 m by 2100, endangering the survival of Manhattan, a threat for which the city is already taking measures [ 90 ]. In Florida, the effects of climate change are likely to include flooding associated with rising sea levels, increased invasive species, damage to coral reefs, and increasing frequency of damaging hurricanes. Tide levels along the US eastern seaboard of the United States during the past century were spatially variable, with the relative sea level rising more rapidly along the Mid-Atlantic Bay than along the Bay of the South Atlantic and the Gulf of Maine [ 97 ]. Other authors [ 73 ] state that rising sea levels, tides, extreme weather conditions, high temperatures, and ocean acidification present serious problems that could affect shipping, shipbuilding, the fishing industry, and coastal tourism and even compromise human health and labor-intensive production activities, such as the sea salt industry, sea fishing and the use of seawater.

In our view, there is a need to encourage international cooperation with countries with a lower HDI in aspects related to the BE, CE and BG through the transfer of knowledge, skills, experiences and technologies that will contribute to achieving the SDGs, bringing significant benefits to both the community and the environment.

The BE presents significant challenges at an economic, social, and environmental level, which is why the BG strategy is presented as the key piece of the puzzle to guarantee environmental sustainability and efficient management of the seas and oceans’ resources. In this context, the SDGs imply that economic development is both inclusive and respectful of the environment, and it is necessary to find a balance between economic, social and environmental spaces. For example, one cannot consider eradicating poverty without guaranteeing the health of ocean ecosystems that are fundamental to food security, livelihoods, and economic development. Therefore, it is urgent to set goals with objectives and indicators that demand productive, healthy, and resilient oceans.

As analyzed, BE is a recent term rooted in sustainable development, so it needs more time for it to be adopted by all economic agents, politicians, and society in general. Thanks to the BG Strategy, it is possible to continue with economic activities arising from the seas and oceans in a more sustainable way that reduces the direct and indirect effects of its execution and minimize the negative impact on the ecosystem.

Regarding scientific production related to these concepts, there is a noticeable growing trend in the number of articles published in journals with high impact factors, especially in the last decade, which is evidence of a growing interest in investigating these terms and this novel field. Although in practice, the BE has always been present in the economic activity and the political agenda of all the countries of the world.

Analysis of keyword trends shows the need to protect coastal areas and traditional activities against the marine industry. These include the urgent transformation of large farms, waste treatment, and a commitment to cleaner energy that respects maritime ecosystems. The oceans are recognized as being essential to sustaining life on Earth, and the overexploitation of their resources jeopardizes their ability to continue to provide food, economic benefits, and environmental services to society. Another critical issue is the role that community ecotourism plays within the dynamics of the BE since marine and coastal tourism constitutes one of the largest and fastest-growing segments of tourism. There are sustainability problems related to the marine tourism sector, especially in protected areas, which could be reduced if the BG strategy is further promoted.

The main conclusion of this research is that BE poses some fundamental conflicts of interest. On the one hand, some studies support growth and development, while others prioritize the protection of ocean resources. Thus, it is essential to harness resources and promoting renewable energies with the resources offered by the oceans and seas, create alliances with different stakeholders, unite efforts, and find common elements to continue with the BG, taking into account each community’s problems and constituting a significant global challenge.

One of the limitations of this study is the difficulty in measuring the impacts of economic activity and therefore quantifying the environmental impacts. Therefore, it would be interesting to carry out studies that can provide solid arguments to support it [ 85 , 122 ].

Possible future lines of research on the BE could focus on incorporating this model of the CE since few articles have addressed this aspect jointly. The relationship between BE and CE should go beyond addressing the issue of global marine waste, renewable energy and climate change but rather be an integrated part of the BG strategy, the circular BG strategy in a broader sense: new components and more respectful treatments, less polluting marine minerals, sustainable management and the equitable distribution of marine resources. Regarding the political agenda, there should be specific lines of financing that support research into the CE and sectors of the BE. Together, the two must be integrated to achieve more efficient and sustainable results.

New researchers, experts, public institutions, and private companies who wish to understand the roots of the BE and its evolution over time may find this article useful to design and develop strategies that lead to its efficient management, preservation, and sustainability.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on request.

Abbreviations

Bilateral contracts

- Blue Economy

Blue degrowth

- Blue growth

Circular economy

Energy storage systems

Human Development Index

- Maritime economy

- Marine economy

Micro-turbines

- Ocean economy

Photovoltaic systems

Sustainable development goals

Wind turbines

Abedinia O, Zareinejad M, Doranehgard MH, Fathi G, Ghadimi N (2019) Optimal offering and bidding strategies of renewable energy based large consumer using a novel hybrid robust-stochastic approach. J Clean Prod 215:878–889

Article Google Scholar

Andriamahefazafy M, Bailey M, Sinan H, Kull CA (2020) The paradox of sustainable tuna fisheries in the Western Indian Ocean: between visions of blue economy and realities of accumulation. Sustain Sci 15(1):75–89

Antonioli F, Falco GD, Presti VL, Moretti L, Scardino G, Anzidei M, Bonaldo D, Carniel S, Leoni G, Furlani S, Marsico A (2020) Relative sea-level rise and potential submersion risk for 2100 on 16 Coastal Plains of the Mediterranean Sea. Water 12(8):2173

Arbo P, Knol M, Linke S, Martin KS (2018) The transformation of the oceans and the future of marine social science. Marit Stud 17(3):295–304

Aria M, Cuccurullo C (2017) bibliometrix: an R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. J Informetr 11(4):959–975

Assevero V.A., Chitre S.P. (2012) Rio 20—an analysis of the zero draft and the final outcome document “the future we want.” SSRN 2177316. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2177316

Balboa CH, Somonte MD (2014) Economía circular como marco para el ecodiseño: el modelo ECO-3. Informador técnico 78(1):82–90

Google Scholar

Barbesgaard M (2018) Blue growth: savior or ocean grabbing? J Peasant Stud 45(1):130–149

Bell J, Paula L, Dodd T, Németh S, Nanou C, Mega V, Campos P (2018) EU ambition to build the world’s leading bioeconomy—uncertain times demand innovative and sustainable solutions. New Biotechnol 40:25–30

Article CAS Google Scholar

Benevolo F (1999) The Italian maritime economy in the Mediterranean area. In: World transport research: selected proceedings of the 8th world conference on transport research world conference on Transport Research Society, vol 1. Antwerp, Belgium. From 1998-7-12 to 1998-7-17

Bennett NJ, Kaplan-Hallam M, Augustine G, Ban N, Belhabib D, Brueckner-Irwin I, Charles A, Couture J, Eger S, Fanning L, Foley P (2018) Coastal and indigenous community access to marine resources and the ocean: a policy imperative for Canada. Mar Policy 87:186–193

Bentlage M, Wiese A, Brandt A, Thierstein A, Witlox F (2014) Revealing relevant proximities knowledge networks in the maritime economy in a spatial, functional, and relational perspective. Raumforsch Raumordn 72(4):275–291

Bogadóttir R (2020) Blue growth and its discontents in the Faroe Islands: an island perspective on blue (de)growth, sustainability, and environmental justice. Sustain Sci 15:103–115. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00763-z

Boonstra WJ, Valman M, Björkvik E (2018) A sea of many colours—how relevant is blue growth for capture fisheries in the Global North, and vice versa? Mar Policy 87:340–349

Brent ZW, Barbesgaard M, Pedersen C (2020) The blue fix: what’s driving blue growth? Sustain Sci 15(1):31–43

Bueger C (2015) What is maritime security? Mar Policy 53:159–164

Burgess MG, Clemence M, McDermott GR, Costello C, Gaines SD (2018) Five rules for pragmatic blue growth. Mar Policy 87:331–339

Caban J, Brumerčík F, Vrábel J, Ignaciuk P, Misztal W, Marczuk A (2017) Safety of maritime transport in the Baltic Sea. In: MATEC web of conferences, vol 134. https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201713400003

Cantwell M (2009) The blue economy: the role of the Oceans in our Nation’s Economic Future. U.S. Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation United States Senate One Hundred Eleventh Congress. Government Printing Office, Washington, 9 June 2009

Cao W, Wong MH (2007) Current status of coastal zone issues and management in China: a review. Environ Int 33(7):985–992

Carpenter A (2012) The EU and marine environmental policy: a leader in protecting the marine environment? J Contemp Eur Res 8(2):248–267

Carver R (2020) Lessons for blue degrowth from Namibia’s emerging blue economy. Sustain Sci 15(1):131–143

Caswell BA, Klein ES, Alleway HK, Ball JE, Botero J, Cardinale M, Thurstan RH (2020) Something old, something new: historical perspectives provide lessons for blue growth agendas. Fish Fish. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12460

Chen JL, Hsu K, Chuang CT (2020) How do fishery resources enhance the development of coastal fishing communities: lessons learned from a community-based sea farming project in Taiwan. Ocean Coast Manag 184:105015

Childs JR, Hicks CC (2019) Securing the blue: political ecologies of the blue economy in Africa. J Political Ecol 26(1):323–340

Clube RK, Tennant M (2020) The circular economy and human needs satisfaction: promising the radical, delivering the familiar. Ecol Econ 177:106772

Colgan CS (2004) Employment and wages for the US ocean and coastal economy. Mon Labor Rev 127:24

Colgan CS (2013) The ocean economy of the United States: measurement, distribution, & trends. Ocean Coast Manag 71:334–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2012.08.018

Costa JAV, de Freitas BCB, Lisboa CR, Santos TD, de Fraga Brusch LR, de Morais MG (2019) Microalgal biorefinery from CO 2 and the effects under the blue economy. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 99:58–65

Cristiani P (2017) New challenges for materials in the blue economy perspective. Metall Italiana 7–8:7–10

Cruikshank K (1992) The intercolonial railway, freight rates, and the maritime economy. Acadiensis 22(1):87–110

Dahl D, Fischer E, Johar G, Morwitz V (2015) The evolution of JCR: a view through the eyes of its editors. J Consum Res 42(1):1–4

Dalton G, Bardócz T, Blanch M, Campbell D, Johnson K, Lawrence G, Lilas T, Friis-Madsen E, Neumann F, Nikitas N, Ortega ST (2019) Feasibility of investment in blue growth multiple-use of space and multi-use platform projects; results of a novel assessment approach and case studies. Renew Sustain Energy Rev 107:338–359

De Vivero JLS, Mateos JCR (2012) The Spanish approach to marine spatial planning. Marine strategy framework directive vs EU integrated maritime policy. Mar Policy 36(1):18–27

Di Q, Han Z, Liu G, Chang H (2007) Carrying capacity of marine region in Liaoning Province. Chin Geogra Sci 17(3):229–235

Ehlers P (2016) Blue growth and ocean governance—how to balance the use and the protection of the seas. WMU J Marit Aff 15(2):187–203

Eikeset AM, Mazzarella AB, Davíðsdóttir B, Klinger DH, Levin SA, Rovenskaya E, Stenseth NC (2018) What is blue growth? The semantics of “sustainable development” of marine environments. Mar Policy 87:177–179

Ertör I, Hadjimichael M (2020) Blue degrowth and the politics of the sea: rethinking the blue economy. Sustain Sci 15(1):1–10

Ertör-Akyazi P (2020) Contesting growth in marine capture fisheries: the case of small-scale fishing cooperatives in Istanbul. Sustain Sci 15(1):45–62

European Commission (2020) The EU blue economy report. 2020. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg. https://doi.org/10.2771/073370

European Commission (EC) (2014) Study on Blue Growth and Maritime Policy within the EU North Sea Region and the English Channel. Ecorys, 7 March 2014 https://ec.europa.eu/assets/mare/infographics . Accessed Dec 2019

Fernández-Macho J, Murillas A, Ansuategi A, Escapa M, Gallastegui C, González P, Prellezo R, Virto J (2015) Measuring the maritime economy: Spain in the European Atlantic Arc. Mar Policy 60:49–61

Froehlich HE, Afflerbach JC, Frazier M, Halpern BS (2019) Blue growth potential to mitigate climate change through seaweed offsetting. Curr Biol 29(18):3087–3093

Gao H, Ding X, Wu S (2020) Exploring the domain of open innovation: bibliometric and content analyses. J Clean Prod 275:122580

Geissdoerfer M, Savaget P, Bocken NM, Hultink EJ (2017) The circular economy—a new sustainability paradigm? J Clean Prod 143:757–768

Gogoberidze G (2008) Comprehensive estimation of marine economy and resource potential of coastal regions. In: 2008 IEEE/OES US/EU-Baltic international symposium. IEEE, pp 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1109/BALTIC.2008.4625489

Gong R, Xue J, Zhao L, Zolotova O, Ji X, Xu Y (2019) A bibliometric analysis of green supply chain management based on the Web of Science (WOS) platform. Sustainability 11(12):3459

Graziano M, Alexander KA, Liesch M, Lema E, Torres JA (2019) Understanding an emerging economic discourse through regional analysis: blue economy clusters in the US Great Lakes basin. Appl Geogr 105:111–123

Gregory JM, Church JA, Boer GJ, Dixon KW, Flato GM, Jackett DR, Lowe JA, O’farrell SP, Roeckner E, Russell GL, Stouffer RJ, Winton M (2001) Comparison of results from several AOGCMs for global and regional sea-level change 1900–2100. Clim Dyn 18(3–4):225–240

Gregory JM, Griffies SM, Hughes CW, Lowe JA, Church JA, Fukimori I et al (2019) Concepts and terminology for sea level: mean, variability and change, both local and global. Surv Geophys 40(6):1251–1289

Guzel AE, Arslan U, Acaravci A (2021) The impact of economic, social, and political globalization and democracy on life expectancy in low-income countries: are sustainable development goals contradictory? Environ Dev Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-021-01225-2

Hadjimichael M (2018) A call for a blue degrowth: unravelling the European Union’s fisheries and maritime policies. Mar Policy 94:158–164

Harzing AW, Alakangas S (2016) Google Scholar, Scopus, and the Web of Science: a longitudinal and cross-disciplinary comparison. Scientometrics 106(2):787–804

Hay Mele B, Russo L, D’Alelio D (2019) Combining marine ecology and economy to roadmap the integrated coastal management: a systematic literature review. Sustainability 11(16):4393

Hoegh-Guldberg O, Beal D, Chaudhry T, Elhaj H, Abdullat A, Etessy P et al (2015) Reviving the ocean economy: the case for action. WWF International, Geneva

Hoerterer C, Schupp MF, Benkens A, Nickiewicz D, Krause G, Buck BH (2020) Stakeholder perspectives on opportunities and challenges in achieving sustainable growth of the blue economy in a changing climate. Front Mar Sci 6:795

Holma M, Lindroos M, Romakkaniemi A, Oinonen S (2019) Comparing economic and biological management objectives in the commercial Baltic salmon fisheries. Mar Policy 100:207–214

Hopwood B, Mellor M, O’Brien G (2005) Sustainable development: mapping different approaches. Sustain Dev 13(1):38–52

Hossain MS, Chowdhury SR, Sharifuzzaman SM (2017) Blue economic development in Bangladesh: a policy guide for marine fisheries and aquaculture. Institute of Marine Sciences and Fisheries, University of Chittagong, Bangladesh

Iustin-Emanuel A, Alexandru T (2014) From circular economy to blue economy. Manag Strateg J 26(4):197–203

Jabbari M, Motlagh MS, Ashrafi K, Abdoli G (2019) Differentiating countries based on the sustainable development proximities using the SDG indicators. Environ Dev Sustain 22:1–19

Joroff M, (2009). The Blue Economy: Sustainable industrialization of the oceans [at] Proceedings. In International Symposium on Blue Economy Initiative for Green Growth, Massachussets Institute of Technology and Korean Maritime Institute, Seoul, Korea, May 7, 2009, pp 173–181

Junquera B, Mitre M (2007) Value of bibliometric analysis for research policy: a case study of Spanish research into innovation and technology management. Scientometrics 71(3):443–454

Kaczynski W (2011) The future of the blue economy: lessons for the European Union. Found Manag 3(1):21–32

Kallis G, Kostakis V, Lange S, Muraca B, Paulson S, Schmelzer M (2018) Research on degrowth. Annu Rev Environ Resour 43:291–316

Kaşdoğan D (2020) Designing sustainability in blues: the limits of technospatial growth imaginaries. Sustain Sci 15:145–160. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11625-019-00766-w

Kathijotes N (2013) Keynote: blue economy-environmental and behavioural aspects towards sustainable coastal development. Procedia Soc Behav Sci 101:7–13

Keefer DK, DeFrance SD, Moseley ME, Richardson JB, Satterlee DR, Day-Lewis A (1998) Early maritime economy and EL Niño events at Quebrada Tacahuay, Peru. Science 281(5384):1833–1835

Kerr S, Colton J, Johnson K, Wright G (2015) Rights and ownership in sea country: implications of marine renewable energy for indigenous and local communities. Mar Policy 52:108–115

Khodaei H, Hajiali M, Darvishan A, Sepehr M, Ghadimi N (2018) Fuzzy-based heat and power hub models for cost-emission operation of an industrial consumer using compromise programming. Appl Therm Eng 137:395–405

Kildow JT, McIlgorm A (2010) The importance of estimating the contribution of the oceans to national economies. Mar Policy 34(3):367–374

Klinger DH, Eikeset AM, Davíðsdóttir B, Winter AM, Watson JR (2018) The mechanics of blue growth: management of oceanic natural resource use with multiple, interacting sectors. Mar Policy 87:356–362

Kong H, Yang W, Wu Q (2016) Research on the sensitivity of the marine industry to climate change. Advances in energy and environment research. Taylor & Francis Group, London

Lee K, Noh J, Khim JS (2020) The blue economy and the United Nations’ sustainable development goals: challenges and opportunities. Environ Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2020.105528

Leszczycki S (1979) Marine economy of Poland 1945–1975. Mitteilungen Der Osterreichischen Geographischen Gesellschaft 121(2):256–270

Li W (2019) Interaction mode of marine economic management talents cultivation and marine industry. J Coast Res 94(sp1):577–580

Li Y, Zhang S (2019) Relationship between environmental information disclosure and cost of equity of listed companies in China’s marine industry. In: Li L, Wan X, Huang X (eds) Recent developments in practices and research on coastal regions: transportation, environment, and economy, special issue no. 98. Coastal Education and Research Foundation, Inc., Coconut Creek, pp 42–45

Lodge M, Johnson D, Le Gurun G, Wengler M, Weaver P, Gunn V (2014) Seabed mining: International Seabed Authority environmental management plan for the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. A partnership approach. Mar Policy 49:66–72

Mah A (2021) Future-proofing capitalism: the paradox of the circular economy for plastics. Glob Environ Politics 21(2):121–142

Martín-Martín A, Orduna-Malea E, Thelwall M, López-Cózar ED (2018) Google Scholar, Web of Science, and Scopus: a systematic comparison of citations in 252 subject categories. J Informetr 12(4):1160–1177

McKinley E, Aller-Rojas O, Hattam C, Germond-Duret C, San Martín IV, Hopkins CR, Aponte H, Potts T (2019) Charting the course for a blue economy in Peru: a research agenda. Environ Dev Sustain 21(5):2253–2275

Milán-García J, Uribe-Toril J, Ruiz-Real JL, de Pablo Valenciano J (2019) Sustainable local development: an overview of the state of knowledge. Resources 8(1):31

Mongeon P, Paul-Hus A (2016) The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: a comparative analysis. Scientometrics 106(1):213–228

Moon T, Ahlstrom A, Goelzer H et al (2018) Rising oceans guaranteed: arctic land ice loss and sea level rise. Curr Clim Change Rep 4:211–222. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40641-018-0107-0

Moore F, Lamond J, Appleby T (2016) Assessing the significance of the economic impact of Marine Conservation Zones in the Irish Sea upon the fisheries sector and regional economy in northern Ireland. Mar Policy 74:136–142

Morrissey K, O’Donoghue C (2013) The role of the marine sector in the Irish national economy: an input–output analysis. Mar Policy 37:230–238

Morrissey K, O’Donoghue C, Hynes S (2011) Quantifying the value of multi-sectoral marine commercial activity in Ireland. Mar Policy 35(5):721–727

Ntona M, Morgera E (2018) Connecting SDG 14 with the other sustainable development goals through marine spatial planning. Mar Policy 93:214–222

Odriozola-Fernández I, Berbegal-Mirabent J, Merigó-Lindahl JM (2019) Open innovation in small and medium enterprises: a bibliometric analysis. J Organ Change Manag. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-12-2017-0491

Oppenheimer M, Glavovic B, Hinkel J, van de Wal R, Magnan AK, Abd‐Elgawad A, Cai R, Cifuentes‐Jara M, Deconto RM, Ghosh T, Hay J, Isla F, Marzeion B, Meyssignac B, Sebesvari Z (2019) Sea level rise and implications for low lying islands, coasts and communities. In: Pörtner HO et al (eds) IPCC special report on the Ocean and cryosphere in a changing climate

Palmer MD, Gregory JM, Bagge M, Calvert D, Hagedoorn JM, Howard T, Klemann V, Lowe JA, Roberts CD, Slangen AB, Spada G (2020) Exploring the drivers of global and local sea-level change over the 21st century and beyond. Earth’s Future 8(9):e2019EF001413

Papageorgiou M, Kyvelou S (2018) Aspects of marine spatial planning and governance: adapting to the transboundary nature and the special conditions of the sea. Eur J Environ Sci 8(1):31–37

Patil P, Virdin J, Diez SM, Roberts J, Singh A (2016) Toward a blue economy: a promise for sustainable growth in the Caribbean. Report No. AUS16344. World Bank, Washington, D.C. https://doi.org/10.1596/25061

Pauli G (2010) The blue economy: 10 years, 100 innovations, 1000 million jobs. Paradigm Publication

Phelan A, Ruhanen L, Mair J (2020) Ecosystem services approach for community-based ecotourism: towards an equitable and sustainable blue economy. J Sustain Tour 28:1–21

Philipp R, Prause G, Meyer C (2020) Blue growth potential in the South Baltic Sea region. Transp Telecommun 21:69–83. https://doi.org/10.2478/ttj-2020-0006

Piecuch CG, Huybers P, Hay CC et al (2018) Origin of spatial variation in US East Coast sea-level trends during 1900–2017. Nature 564:400–404. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0787-6

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Podsakoff NP, Bachrach DG (2008) Scholarly influence in the field of management: a bibliometric analysis of the determinants of university and author impact in the past quarter century. J Manag 34(4):641–720

Potgieter T (2018) Oceans economy, blue economy, and security: notes on the South African potential and developments. J Indian Ocean Region 14(1):49–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/19480881.2018.1410962

Prabhu MS, Israel A, Palatnik RR et al (2020) Integrated biorefinery process for sustainable fractionation of Ulva ohnoi (Chlorophyta): process optimization and revenue analysis. J Appl Phycol 32:2271–2282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10811-020-02044-0

Pudzis E, Adlers A, Pukite I, Geipele S, Zeltins N (2018) Identification of maritime technology development mechanisms in the context of Latvian smart specialisation and blue growth. Latvian J Phys 55(4):57–69. https://doi.org/10.2478/lpts-2018-0029

Qi X, Xiao W (2019) Identifying the evolutionary path of maritime industries from the perspective of supernetwork. J Coast Res 97(sp1):131–135

Raakjaer J, Van Leeuwen J, van Tatenhove J, Hadjimichael M (2014) Ecosystem-based marine management in European regional seas calls for nested governance structures and coordination—a policy brief. Mar Policy 50:373–381

Rayner R, Jolly C, Gouldman CC (2019) Ocean observing and the blue economy. Front Mar Sci 6:330

Rotter A, Bacu A, Barbier M, Bertoni F, Bones AM, Cancela ML, Dailianis T (2020) A new network for the advancement of marine biotechnology in Europe and beyond. Front Mar Sci 7:278

Rountrey AN, Coulson PG, Meeuwig JJ, Meekan M (2014) Water temperature and fish growth: otoliths predict growth patterns of a marine fish in a changing climate. Glob Change Biol 20(8):2450–2458

Ruiz-Real JL, Uribe-Toril J, De Pablo Valenciano J, Gázquez-Abad JC (2018) Worldwide research on circular economy and environment: a bibliometric analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(12):2699

Saeedi M, Moradi M, Hosseini M, Emamifar A, Ghadimi N (2019) Robust optimization based optimal chiller loading under cooling demand uncertainty. Appl Therm Eng 148:1081–1091

Said A, MacMillan D (2020) ‘Re-grabbing’marine resources: a blue degrowth agenda for the resurgence of small-scale fisheries in Malta. Sustain Sci 15(1):91–102

Sakhuja V (2015) Harnessing the blue economy. Indian Foreign Aff J 10(1):39

Salmonowicz H (2007) Maritime economy—system, feature, range and tendency of changes. 12 Sci J Marit Univ Szczecin 12:157–172

Sariatli F (2017) Linear economy versus circular economy: a comparative and analyzer study for optimization of economy for sustainability. Visegrad J Bioecon Sustain Dev 6(1):31–34

Schutter MS, Hicks CC (2019) Networking the blue economy in Seychelles: pioneers, resistance, and the power of influence. J Political Ecol 26(1):425–447

Sdoukopoulos E, Tsafonias G, Perra VM, Boile M, Lago LF (2019) Identifying skill shortages and education and training gaps for the shipbuilding industry in Europe. In: Sustainable development and innovations in marine technologies: proceedings of the 18th international congress of the Maritime Association of the Mediterranean (IMAM 2019), September 9–11, 2019, Varna, Bulgaria. CRC Press, p 458

Shennan I (1986) Flandrian sea-level changes in the Fenland. II: tendencies of sea-level movement, altitudinal changes, and local and regional factors. J Quat Sci 1(2):155–179

Shih YC (2017) Coastal management and implementation in Taiwan. J Coast Zone Manag 19(4):1–7

Shojaei A, Ketabi R, Razkenari M, Hakim H, Wang J (2021) Enabling a circular economy in the built environment sector through blockchain technology. J Clean Prod 294:126352

Silver JJ, Gray NJ, Campbell LM, Fairbanks LW, Gruby RL (2015) Blue economy and competing discourses in international oceans governance. J Environ Dev 24(2):135–160

Skrzeszewska K, Beran IM (2016) Is ignorance of potential career paths a disincentive for starting a career in the maritime sectors? In: Economic and social development: book of proceedings, p 577

Soma K, Van den Burg SW, Hoefnagel EW, Stuiver M, van der Heide CM (2018) Social innovation—a future pathway for blue growth? Mar Policy 87:363–370

Spamer J (2015) Riding the African blue economy wave: a South African perspective. In: 2015 4th international conference on advanced logistics and transport (ICALT). IEEE, pp 59–64. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICAdLT.2015.7136591

Surís-Regueiro JC, Garza-Gil MD, Varela-Lafuente MM (2013) Marine economy: a proposal for its definition in the European Union. Mar Policy 42:111–124

Suursaar Ü, Kullas T, Otsmann M (2002) A model study of the sea level variations in the Gulf of Riga and the Väinameri Sea. Cont Shelf Res 22(14):2001–2019

UNCTAD (2014) The state of commodity dependence 2014. United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, Geneva

UNECA (2016) Africa’s blue economy: a policy handbook. UN Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA), Addis Ababa

Van den Burg SWK, Aguilar-Manjarrez J, Jenness J, Torrie M (2019) Assessment of the geographical potential for co-use of marine space, based on operational boundaries for blue growth sectors. Mar Policy 100:43–57

Van Dijk AIJM, Renzullo LJ, Wada Y, Tregoning P (2014) A global water cycle reanalysis (2003–2012) merging satellite gravimetry and altimetry observations with a hydrological multi-model ensemble. Hydrol Earth Syst Sci 18(8):2955

Van Eck NJ, Waltman L (2011) Text mining and visualization using VOSviewer. arXiv preprint. arXiv:1109.2058

Vedachalam N, Ramesh S, Umapathy A, Ramadass GA (2016) Importance of gas hydrates for India and characterization of methane gas dissociation in the Krishna–Godavari basin reservoir. Mar Technol Soc J 50(6):58–68

Virto LR (2018) A preliminary assessment of the indicators for sustainable development goal (SDG) 14 “conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development.” Mar Policy 98:47–57

Voyer M, Quirk G, McIlgorm A, Azmi K (2018) Shades of blue: what do competing interpretations of the blue economy mean for oceans’ governance? J Environ Plan Policy Manag 20(5):595–616

Voyer M, Schofield C, Azmi K, Warner R, McIlgorm A, Quirk G (2018) Maritime security and the blue economy: intersections and interdependencies in the Indian Ocean. J Indian Ocean Region 14(1):28–48

Walcher D, Leube M (2017) Circular economy by co-creation. In: Preparing designers and decision makers for upcoming transformations Salzburg University of Applied Sciences/Design and product management submitted 20th April 2017 to the 15th international open and user innovation conference, Innsbruck- http://ouisociety.org

Wenwen X, Bingxin Z, Lili W (2016) Marine industrial cluster structure and its coupling relationship with urban development: a case pf Shandong Province. Polish Marit Res 23(s1):115–122

Winder GM, Le Heron R (2017) Assembling a blue economy moment? Geographic engagement with globalizing biological-economic relations in multi-use marine environments. Dialogues Hum Geogr 7(1):3–26

Wolters HA, Gille J, De Vet JM, Molemaker RJ (2013) Scenarios for selected maritime economic functions. Eur J Futures Res 1(1):11

World Bank (2013) Fish to 2030—prospects for fisheries and aquaculture. World Bank Report Number 83177-GLB. Washington, DC

Zanuttigh B, Angelelli E, Kortenhaus A, Koca K, Krontira Y, Koundouri P (2016) A methodology for multi-criteria design of multi-use offshore platforms for marine renewable energy harvesting. Renew Energy 85:1271–1289

Zghyer R, Ostnes R, Halse KH (2019) Is full-autonomy the way to go towards maximizing the ocean potentials? TransNav Int J Mar Navig Saf Sea Transp 13(1):33–42

Zhang YG, Dong LJ, Yang J, Wang SY, Song XR (2004) Sustainable development of marine economy in China. Chin Geogra Sci 14(4):308–313

Zhou X, Zhao X, Zhang S, Lin J (2019) Marine ranching construction and management in East China Sea: programs for sustainable fishery and aquaculture. Water 11(6):1237

Download references

Acknowledgements

This article has been carried out with the support of the Campus of International Excellence of the Sea (CEIMAR).

This research received no external funding.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Almería, Ctra. De Sacramento, s/n, 04120, Almería, Spain

Rosa María Martínez-Vázquez, Juan Milán-García & Jaime de Pablo Valenciano

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

Conceptualization: RMMV, JMG and JDPV; methodology: RMMV, JMG and JDPV; software: RMMV, JMG and JDPV; validation: RMMV, JMG and JDPV; formal analysis: RMMV, JMG and JDPV; investigation: RMMV, JMG and JDPV; resources: RMMV, JMG and JDPV; writing—original draft preparation: RMMV, JMG and JDPV. All authors have agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rosa María Martínez-Vázquez .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Competing interests.

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Martínez-Vázquez, R.M., Milán-García, J. & de Pablo Valenciano, J. Challenges of the Blue Economy: evidence and research trends. Environ Sci Eur 33 , 61 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-021-00502-1

Download citation

Received : 05 February 2021

Accepted : 08 May 2021

Published : 17 May 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-021-00502-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Bibliometric analysis

The Blue Economy - Sustainability, Innovation, and our Ocean

Course Description

Earth's defining feature is the ocean and it is the reason that life exists. It produces oxygen, absorbs carbon dioxide, and contributes to freshwater renewal. The ocean provides important goods and services to all of society, connecting countries and cultures while supporting ecosystems that cross national boundaries. It is a major part of the world economy, with more nations looking to the ocean to enhance livelihoods and wellbeing, particularly coastal communities and island nations. Some nations are looking at their large lakes and rivers to do the same.

The concept of the blue economy is a loosely defined development model that builds on that of the green economy and encompasses a range of activities and policy aspirations that vary globally. These aspirations are influenced by economic growth and socio-ecological sustainability priorities. Equitable, just, and sustainable blue economy frameworks will require innovative governance and practice across all levels of society. This course will explore the key components of the blue economy and link these to practical examples.

Course Contents

Week 1: Introduction to the Blue Economy 1.1 Course orientation 1.2 What is the blue economy? 1.3 The key principles of the blue economy

Week 2: Innovation and the Blue Economy 2.1 Coastal and ocean industries 2.2 Blue economy stakeholders 2.3 Blue economy innovations

Week 3: The Blue Economy in Practice 3.1 Blue economy knowledge support 3.2 National blue economy strategies

Week 4: Understanding Ecosystem Services 4.1 Introduction to ecosystem services 4.2 Our reliance on ecosystem services 4.3 Ecosystem threats

Week 5: Ecosystem Services and Global Ocean Economies 5.1 Valuing ecosystem services 5.2 The fundamental techniques used to value natural resources and ecosystem services 5.3 Natural capital and the blue economy

Why should you do this course?

The benefits of developing a sustainable blue economy are not only relevant to coastal and ocean nations, but also to landlocked countries who indirectly benefit from (and impact) the resources and services provided by the ocean. Additionally, this course is well aligned with the UN's Sustainable Development Goal #14 - Life Below Water, focused on conservation and sustainable use of the oceans, seas and marine resources, as well as many more of the SDGs.

Over five weeks, you'll discover the potential that the blue economy has to drive innovative ocean engagement. Through discussion forums with experts, videos and readings, you'll get to interact and collaborate with other learners. Our self-assessment model means you only take quizzes when you're ready. You will also receive a certificate upon completion to verify your achievement. If you spend 4-5 hours of your time per week on this course, you should be able to complete it in five weeks.

Target audience

The course is designed as an introductory course to attract participants from various backgrounds, both technical and non-technical. The integrated, cross-sectoral nature of the blue economy provides opportunity for new knowledge to be developed, regardless of how much or how little you may know.

Outcomes of this Course

Upon completion of this course, you should be able to:

- Discuss the blue economy, its priorities and some of the challenges in operationalising a blue economy.

- Identify ocean sectors that form part of the ocean economy and those that have the potential to build a sustainable ocean economy.

- Recognise the importance of natural capital and ecosystem services to the blue economy.

Certificates

Two levels of certification are available.

Certificates of Participation will be awarded to participants who pass two quizzes with 70% or more and contribute to at least two forum discussions.

Certificates of Completion will be awarded to those who meet the requirements for a Certificate of Participation as well as completing a final Position Statement.

Course Team

LEAD INSTRUCTOR

Kelly Hoareau has over 15 years' experience in environmental, sustainability and leadership roles, with first-hand experience of working in Africa and with various small island developing states and coastal nations, across marine and terrestrial ecosystems. She is the former and founding Director of the University of Seychelles’ James Michel Blue Economy Research Institute and a co-founder and management committee member of UniSey’s Island Biodiversity Conservation centre. She is currently working full time on her PhD which explores the role that knowledge systems play in supporting a more sustainable blue economy.

Affiliations: Blue Economy Cooperative Research Centre; Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies; Centre for Marine Socioecology, University of Tasmania, Australia. James Michel Blue Economy Research Institute and Island Biodiversity Conservation centre, University of Seychelles, Seychelles.

Other Information

Level: Introductory

Prerequisites: None

Language: English