What this handout is about

This handout will provide a broad overview of gathering and using evidence. It will help you decide what counts as evidence, put evidence to work in your writing, and determine whether you have enough evidence. It will also offer links to additional resources.

Introduction

Many papers that you write in college will require you to make an argument ; this means that you must take a position on the subject you are discussing and support that position with evidence. It’s important that you use the right kind of evidence, that you use it effectively, and that you have an appropriate amount of it. If, for example, your philosophy professor didn’t like it that you used a survey of public opinion as your primary evidence in your ethics paper, you need to find out more about what philosophers count as good evidence. If your instructor has told you that you need more analysis, suggested that you’re “just listing” points or giving a “laundry list,” or asked you how certain points are related to your argument, it may mean that you can do more to fully incorporate your evidence into your argument. Comments like “for example?,” “proof?,” “go deeper,” or “expand” in the margins of your graded paper suggest that you may need more evidence. Let’s take a look at each of these issues—understanding what counts as evidence, using evidence in your argument, and deciding whether you need more evidence.

What counts as evidence?

Before you begin gathering information for possible use as evidence in your argument, you need to be sure that you understand the purpose of your assignment. If you are working on a project for a class, look carefully at the assignment prompt. It may give you clues about what sorts of evidence you will need. Does the instructor mention any particular books you should use in writing your paper or the names of any authors who have written about your topic? How long should your paper be (longer works may require more, or more varied, evidence)? What themes or topics come up in the text of the prompt? Our handout on understanding writing assignments can help you interpret your assignment. It’s also a good idea to think over what has been said about the assignment in class and to talk with your instructor if you need clarification or guidance.

What matters to instructors?

Instructors in different academic fields expect different kinds of arguments and evidence—your chemistry paper might include graphs, charts, statistics, and other quantitative data as evidence, whereas your English paper might include passages from a novel, examples of recurring symbols, or discussions of characterization in the novel. Consider what kinds of sources and evidence you have seen in course readings and lectures. You may wish to see whether the Writing Center has a handout regarding the specific academic field you’re working in—for example, literature , sociology , or history .

What are primary and secondary sources?

A note on terminology: many researchers distinguish between primary and secondary sources of evidence (in this case, “primary” means “first” or “original,” not “most important”). Primary sources include original documents, photographs, interviews, and so forth. Secondary sources present information that has already been processed or interpreted by someone else. For example, if you are writing a paper about the movie “The Matrix,” the movie itself, an interview with the director, and production photos could serve as primary sources of evidence. A movie review from a magazine or a collection of essays about the film would be secondary sources. Depending on the context, the same item could be either a primary or a secondary source: if I am writing about people’s relationships with animals, a collection of stories about animals might be a secondary source; if I am writing about how editors gather diverse stories into collections, the same book might now function as a primary source.

Where can I find evidence?

Here are some examples of sources of information and tips about how to use them in gathering evidence. Ask your instructor if you aren’t sure whether a certain source would be appropriate for your paper.

Print and electronic sources

Books, journals, websites, newspapers, magazines, and documentary films are some of the most common sources of evidence for academic writing. Our handout on evaluating print sources will help you choose your print sources wisely, and the library has a tutorial on evaluating both print sources and websites. A librarian can help you find sources that are appropriate for the type of assignment you are completing. Just visit the reference desk at Davis or the Undergraduate Library or chat with a librarian online (the library’s IM screen name is undergradref).

Observation

Sometimes you can directly observe the thing you are interested in, by watching, listening to, touching, tasting, or smelling it. For example, if you were asked to write about Mozart’s music, you could listen to it; if your topic was how businesses attract traffic, you might go and look at window displays at the mall.

An interview is a good way to collect information that you can’t find through any other type of research. An interview can provide an expert’s opinion, biographical or first-hand experiences, and suggestions for further research.

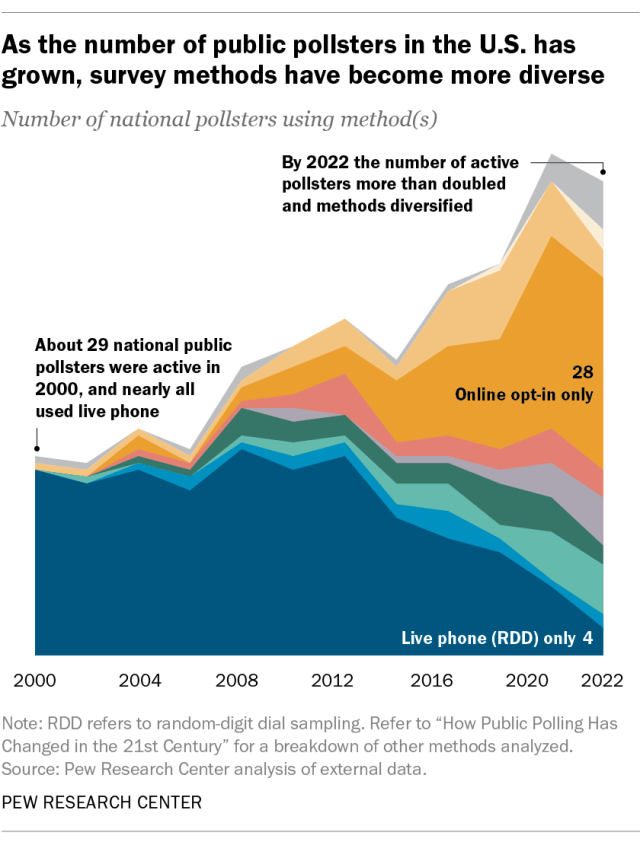

Surveys allow you to find out some of what a group of people thinks about a topic. Designing an effective survey and interpreting the data you get can be challenging, so it’s a good idea to check with your instructor before creating or administering a survey.

Experiments

Experimental data serve as the primary form of scientific evidence. For scientific experiments, you should follow the specific guidelines of the discipline you are studying. For writing in other fields, more informal experiments might be acceptable as evidence. For example, if you want to prove that food choices in a cafeteria are affected by gender norms, you might ask classmates to undermine those norms on purpose and observe how others react. What would happen if a football player were eating dinner with his teammates and he brought a small salad and diet drink to the table, all the while murmuring about his waistline and wondering how many fat grams the salad dressing contained?

Personal experience

Using your own experiences can be a powerful way to appeal to your readers. You should, however, use personal experience only when it is appropriate to your topic, your writing goals, and your audience. Personal experience should not be your only form of evidence in most papers, and some disciplines frown on using personal experience at all. For example, a story about the microscope you received as a Christmas gift when you were nine years old is probably not applicable to your biology lab report.

Using evidence in an argument

Does evidence speak for itself.

Absolutely not. After you introduce evidence into your writing, you must say why and how this evidence supports your argument. In other words, you have to explain the significance of the evidence and its function in your paper. What turns a fact or piece of information into evidence is the connection it has with a larger claim or argument: evidence is always evidence for or against something, and you have to make that link clear.

As writers, we sometimes assume that our readers already know what we are talking about; we may be wary of elaborating too much because we think the point is obvious. But readers can’t read our minds: although they may be familiar with many of the ideas we are discussing, they don’t know what we are trying to do with those ideas unless we indicate it through explanations, organization, transitions, and so forth. Try to spell out the connections that you were making in your mind when you chose your evidence, decided where to place it in your paper, and drew conclusions based on it. Remember, you can always cut prose from your paper later if you decide that you are stating the obvious.

Here are some questions you can ask yourself about a particular bit of evidence:

- OK, I’ve just stated this point, but so what? Why is it interesting? Why should anyone care?

- What does this information imply?

- What are the consequences of thinking this way or looking at a problem this way?

- I’ve just described what something is like or how I see it, but why is it like that?

- I’ve just said that something happens—so how does it happen? How does it come to be the way it is?

- Why is this information important? Why does it matter?

- How is this idea related to my thesis? What connections exist between them? Does it support my thesis? If so, how does it do that?

- Can I give an example to illustrate this point?

Answering these questions may help you explain how your evidence is related to your overall argument.

How can I incorporate evidence into my paper?

There are many ways to present your evidence. Often, your evidence will be included as text in the body of your paper, as a quotation, paraphrase, or summary. Sometimes you might include graphs, charts, or tables; excerpts from an interview; or photographs or illustrations with accompanying captions.

When you quote, you are reproducing another writer’s words exactly as they appear on the page. Here are some tips to help you decide when to use quotations:

- Quote if you can’t say it any better and the author’s words are particularly brilliant, witty, edgy, distinctive, a good illustration of a point you’re making, or otherwise interesting.

- Quote if you are using a particularly authoritative source and you need the author’s expertise to back up your point.

- Quote if you are analyzing diction, tone, or a writer’s use of a specific word or phrase.

- Quote if you are taking a position that relies on the reader’s understanding exactly what another writer says about the topic.

Be sure to introduce each quotation you use, and always cite your sources. See our handout on quotations for more details on when to quote and how to format quotations.

Like all pieces of evidence, a quotation can’t speak for itself. If you end a paragraph with a quotation, that may be a sign that you have neglected to discuss the importance of the quotation in terms of your argument. It’s important to avoid “plop quotations,” that is, quotations that are just dropped into your paper without any introduction, discussion, or follow-up.

Paraphrasing

When you paraphrase, you take a specific section of a text and put it into your own words. Putting it into your own words doesn’t mean just changing or rearranging a few of the author’s words: to paraphrase well and avoid plagiarism, try setting your source aside and restating the sentence or paragraph you have just read, as though you were describing it to another person. Paraphrasing is different than summary because a paraphrase focuses on a particular, fairly short bit of text (like a phrase, sentence, or paragraph). You’ll need to indicate when you are paraphrasing someone else’s text by citing your source correctly, just as you would with a quotation.

When might you want to paraphrase?

- Paraphrase when you want to introduce a writer’s position, but their original words aren’t special enough to quote.

- Paraphrase when you are supporting a particular point and need to draw on a certain place in a text that supports your point—for example, when one paragraph in a source is especially relevant.

- Paraphrase when you want to present a writer’s view on a topic that differs from your position or that of another writer; you can then refute writer’s specific points in your own words after you paraphrase.

- Paraphrase when you want to comment on a particular example that another writer uses.

- Paraphrase when you need to present information that’s unlikely to be questioned.

When you summarize, you are offering an overview of an entire text, or at least a lengthy section of a text. Summary is useful when you are providing background information, grounding your own argument, or mentioning a source as a counter-argument. A summary is less nuanced than paraphrased material. It can be the most effective way to incorporate a large number of sources when you don’t have a lot of space. When you are summarizing someone else’s argument or ideas, be sure this is clear to the reader and cite your source appropriately.

Statistics, data, charts, graphs, photographs, illustrations

Sometimes the best evidence for your argument is a hard fact or visual representation of a fact. This type of evidence can be a solid backbone for your argument, but you still need to create context for your reader and draw the connections you want them to make. Remember that statistics, data, charts, graph, photographs, and illustrations are all open to interpretation. Guide the reader through the interpretation process. Again, always, cite the origin of your evidence if you didn’t produce the material you are using yourself.

Do I need more evidence?

Let’s say that you’ve identified some appropriate sources, found some evidence, explained to the reader how it fits into your overall argument, incorporated it into your draft effectively, and cited your sources. How do you tell whether you’ve got enough evidence and whether it’s working well in the service of a strong argument or analysis? Here are some techniques you can use to review your draft and assess your use of evidence.

Make a reverse outline

A reverse outline is a great technique for helping you see how each paragraph contributes to proving your thesis. When you make a reverse outline, you record the main ideas in each paragraph in a shorter (outline-like) form so that you can see at a glance what is in your paper. The reverse outline is helpful in at least three ways. First, it lets you see where you have dealt with too many topics in one paragraph (in general, you should have one main idea per paragraph). Second, the reverse outline can help you see where you need more evidence to prove your point or more analysis of that evidence. Third, the reverse outline can help you write your topic sentences: once you have decided what you want each paragraph to be about, you can write topic sentences that explain the topics of the paragraphs and state the relationship of each topic to the overall thesis of the paper.

For tips on making a reverse outline, see our handout on organization .

Color code your paper

You will need three highlighters or colored pencils for this exercise. Use one color to highlight general assertions. These will typically be the topic sentences in your paper. Next, use another color to highlight the specific evidence you provide for each assertion (including quotations, paraphrased or summarized material, statistics, examples, and your own ideas). Lastly, use another color to highlight analysis of your evidence. Which assertions are key to your overall argument? Which ones are especially contestable? How much evidence do you have for each assertion? How much analysis? In general, you should have at least as much analysis as you do evidence, or your paper runs the risk of being more summary than argument. The more controversial an assertion is, the more evidence you may need to provide in order to persuade your reader.

Play devil’s advocate, act like a child, or doubt everything

This technique may be easiest to use with a partner. Ask your friend to take on one of the roles above, then read your paper aloud to them. After each section, pause and let your friend interrogate you. If your friend is playing devil’s advocate, they will always take the opposing viewpoint and force you to keep defending yourself. If your friend is acting like a child, they will question every sentence, even seemingly self-explanatory ones. If your friend is a doubter, they won’t believe anything you say. Justifying your position verbally or explaining yourself will force you to strengthen the evidence in your paper. If you already have enough evidence but haven’t connected it clearly enough to your main argument, explaining to your friend how the evidence is relevant or what it proves may help you to do so.

Common questions and additional resources

- I have a general topic in mind; how can I develop it so I’ll know what evidence I need? And how can I get ideas for more evidence? See our handout on brainstorming .

- Who can help me find evidence on my topic? Check out UNC Libraries .

- I’m writing for a specific purpose; how can I tell what kind of evidence my audience wants? See our handouts on audience , writing for specific disciplines , and particular writing assignments .

- How should I read materials to gather evidence? See our handout on reading to write .

- How can I make a good argument? Check out our handouts on argument and thesis statements .

- How do I tell if my paragraphs and my paper are well-organized? Review our handouts on paragraph development , transitions , and reorganizing drafts .

- How do I quote my sources and incorporate those quotes into my text? Our handouts on quotations and avoiding plagiarism offer useful tips.

- How do I cite my evidence? See the UNC Libraries citation tutorial .

- I think that I’m giving evidence, but my instructor says I’m using too much summary. How can I tell? Check out our handout on using summary wisely.

- I want to use personal experience as evidence, but can I say “I”? We have a handout on when to use “I.”

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and John J. Ruszkiewicz. 2016. Everything’s an Argument , 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Miller, Richard E., and Kurt Spellmeyer. 2016. The New Humanities Reader , 5th ed. Boston: Cengage.

University of Maryland. 2019. “Research Using Primary Sources.” Research Guides. Last updated October 28, 2019. https://lib.guides.umd.edu/researchusingprimarysources .

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

It's Lit Teaching

High School English and TPT Seller Resources

- Creative Writing

- Teachers Pay Teachers Tips

- Shop My Teaching Resources!

- Sell on TPT

Claim, Evidence, Reasoning: What You Need to Know

Has an instructional coach or administrator told you to start using a claim, evidence, and reasoning (or C-E-R) framework for writing in your classroom?

Maybe you need to closely adhere to the Common Core State Standards but aren’t quite sure where to begin.

If you’re like me, your whole school may be committing to using a C-E-R language in all classes to build consistency and teacher equity for students.

Regardless, here you are wondering, what the heck is claim, evidence, and reasoning anyway ? In this post, I aim to break it down for you.

There are plenty of science examples out there, but that is not my specialty. For this post, I’ll focus on my subject area, high school English, but know that the C-E-R framework can be applied to multiple content areas.

If you’d like to teach the C-E-R writing framework to your students, I have a whole bundle of resources right here.

C-E-R (Claim, Evidence, Reasoning) Writing Overview

C-E-R writing is a framework that consists of three parts: Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning. Science classes use it frequently, but it works well in any content area. In fact, my entire school uses it–down to the gym classes!

A C-E-R writing framework works especially well for teachers adhering to the Common Core State Standards. The words “claim”, “evidence”, and “reasoning” are directly from the standards themselves.

C-E-R writing works especially well for argumentative or persuasive writing, but also holds true for research-based writing.

Note that these are academic forms of writing. You wouldn’t, for instance, probably use claims, evidence, or reasoning in a creative writing class or with a narrative or poetry unit.

While C-E-R may seem formulaic at first, it does come from a natural flow of solid arguments. Any attempt at persuasion must take a stance, support it with logic, and make a case.

The formulaic nature of C-E-R writing makes it a helpful writing scaffold for students who struggle to organize their ideas or generate them in the first place.

The claim sets the tone for the rest of the writing.

It is the argument, the stance, or the main idea of the writing that is to follow. Some may say that in C-E-R writing, the claim is the most important piece.

I have found that the placement and length of the claim will vary according to the length of the writing.

For a paragraph, I feel the claim makes a great topic sentence and thus, should be the first sentence. The body of the paragraph then will aim to support the topic sentence (or claim).

In a standard five-paragraph essay , the first introductory paragraph may build to the claim: the thesis. The body paragraphs then will each contain a sub-claim so-to-speak that supports the overarching claim or thesis.

Claims, while logical, should present an arguable stance on a topic.

I often have to remind my students that if they are writing in response to a question, restating the question in the form of a sentence and adding their answer is an easy way to write a claim.

A Claim Example for an English Class

Let’s use a Shakespearian example. A popular essay topic when reading Romeo and Juliet poses the following question: who is to blame for the deaths of Romeo and Juliet?

A claim that answers this question might read:

“Friar Laurence is most to blame for Romeo and Juliet’s deaths.”

This claim is strong for multiple reasons. First, it is direct. There’s no question about what the rest of the writing will be about or will be attempting to support. Second, this claim is arguable –not provable–but also logical. The idea can be supported by examples from the text.

A claim is not a fact. Evidence should support it, which we’ll discuss in a moment, but ultimately, it should not be something that can be proven .

The next step in the C-E-R writing framework is evidence.

Evidence is the logic, proof, or support that you have for your claim. I mentioned earlier that your claim, while arguable, should be rooted in logic. Evidence is where you present the logic you used to arrive at your claim.

This can take a variety of forms: research, facts, observations, lab experiments, or even quotes from interviews or authorities.

For literary analysis, evidence should generally be textual in nature.

That is, the evidence should be rooted–if not directly quoted from–in the text. For example, the writer may want to use quotes, paraphrasing, or a summary of events from the text.

I encourage my students to use word-for-word textual evidence quoted and cited from the text directly. This creates evidence with which it is difficult to argue.

An Evidence Example for an English Class

If we continue with the Romeo and Juliet example, we could support our previous claim that Friar Laurence is most to blame for the couple’s death by presenting several pieces of evidence from the play.

Our evidence may then read as follows:

“ In the play, Friar Laurence says to Juliet, ‘Take thou this vial, being then in bed/ And this distilled liquor drink thou off;/ …The roses in thy lips and cheeks shall fade/ … And in this borrow’d likeness of shrunk death/ Thou shalt continue two and forty hours,/And then awake as from a pleasant sleep ’ (4.1.93-106).”

This is strong evidence because the text proves it. This quote comes directly from Shakespeare; you can’t argue with it.

It is also on-topic. it shows a piece of the play that supports the idea that Friar Laurence is most to blame for Romeo and Juliet’s deaths.

For claim, evidence, and reasoning writing, the strength of the argument depends on its evidence.

Grab a FREE Copy of Must-Have Classroom Library Title!

Sign-up for a FREE copy of my must-have titles for your classroom library and regular updates to It’s Lit Teaching! Insiders get the scoop on new blog posts, teaching resources, and the occasional pep talk!

Marketing Permissions

I just want to make sure you’re cool with the things I may send you!

By clicking below to submit this form, you acknowledge that the information you provide will be processed in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

You have successfully joined our subscriber list.

Reasoning is the thinking behind the evidence that led to the claim. It should explain the evidence if necessary, and then connect it to the claim.

In a one paragraph response, I usually recommend that students break down their reasoning into three sentences:

Personally, this is where my students struggle the most. They have a hard time understanding how to explain the evidence or connect it to their claim because it’s obvious to them.

- Explain or summarize the evidence that was just used

- Explain or show how this evidence supports the claim

- Finish with a conclusion sentence

If your students, like mine, struggle with crafting reasoning, I recommend giving them sentence starters like “This shows that…” or “This quote proves that….”

I also go over different ways to approach writing conclusion sentences, as my students often struggle in ending their writing.

(If you’d like help breaking this down for your students, my C-E-R Slideshow covers reasoning–including what to include and three different ways to write a conclusion sentence.)

A Reasoning Example for An English Class

For our Romeo and Juliet example, it may read something like this:

“This quote shows that Friar Laurence is the originator of the plan for the two lovers to fake their deaths. Had he not posed this plan, Romeo could not have mistaken Juliet for dead. Thus, he would never have committed suicide, nor Juliet. As the adult in the situation, Friar Laurence should have acted less rashly and helped the couple find a more suitable solution to their problems.”

This reasoning is strong for several reasons.

First, note the transition in the beginning. It discusses the textual evidence–the quote presented earlier–directly and explains what is happening in the quote.

Next, it walks the reader step-by-step through the writer’s rationale about the evidence that led her to believe the claim. Even if the reader does not agree with the reader’s claim, he or she must concede that the writer has a point.

You may have noticed that in this example, the reasoning tends to be longer than either the claim or the evidence. The length of the reasoning will vary according to the assignment, but I have found that good reasoning does tend to be the bulk of C-E-R writing.

Get Started with Claim, Evidence, and Reasoning Today!

And there you have it! An overview of the C-E-R writing framework. No doubt, you can see how this framework can easily be applied to a myriad of assignments in any content area.

If you need help getting started in using the C-E-R writing framework in your English class, I have a few resources in my Teachers Pay Teachers store that can help you. Check them out! Start with a FREE student guide to claim, evidence, and reasoning!

- Free Interview Course

Home > Blog > Essay Writing Guide – Using Evidence In Your Arguments

Essay Writing Guide – Using Evidence In Your Arguments

Essay Writing Guide – Introduction

If you want to write a good essay, you need strong evidence to support your ideas. No matter how good your ideas are, you need to support them with evidence. Strong evidence is vital for achieving high grades in essay-based assessments. If you make a claim, you must always give evidence for it. In this essay writing guide, we’re going to take a look at how to incorporate evidence into your argument.

Essay Writing Guide – What is Evidence?

One dictionary defines evidence as follows:

“The available body of facts or information indicating whether a belief or proposition is true or valid.”

This means that evidence is material which can be used to support an argument, claim, belief, or proposition. For example, fossils and bones are evidence to support the accepted theory that dinosaurs once walked the earth.

Essay Writing Guide – Different Kinds of Evidence

The definition of evidence that we’ve given is quite broad. In essence, any kind of facts or information can be regarded as evidence. The thing to make note of is that not all evidence is good evidence! What determines whether evidence is good or bad will depend on the subject you’re writing an essay for. This is because different academic disciplines, such as History and English Literature, care more about different types of evidence. Let’s take a look at different kinds of evidence now.

- Sciences such as Physics, Biology, Chemistry and Psychology, value peer-reviewed results of scientific studies.This means that, when making scientific arguments, you need to find results from well-received studies to support your argument.

- In contrast, History accepts a wider range of kinds of evidence. Historical statistics are welcome, but historical interpretation is also important.Strong theories written by historians can be used to support your own argument.

- In a subject such as English Literature, evidence will usually come in the form of quotations. For example, you might be asked to discuss the themes of a play.

To support your argument, you should find relevant quotations from the play. Like History, interpretations are also accepted as evidence. Try to find writers in the field of literary criticism which present theories about the play, book, or poem that you’re writing about.

Essay Writing Guide – How to Use Evidence in an Essay

When writing an essay, it is essential that you provide evidence. As we’ve discussed, evidence takes many forms. Make sure your type of evidence is appropriate for the subject you’re writing about.

So, if you’re writing a Psychology essay, don’t fill it with historical interpretation. Hard facts are necessary to sell your hypothesis in a scientific essay. Likewise, don’t bring hard statistics into an English Literature essay. This subject is all about interpretation, and so scientific studies won’t be particularly useful.

Evidence is always used to support a point that you’re trying to make.

- So, you make your point first. This is the claim of your argument: “Dinosaurs walked the earth tens of millions of years ago.”

- Once you’ve made your point, move on to your evidence: “Fossils found in Central America show that creatures used to live there.”

- Then you need to link the evidence back to your point by explaining it: “We can use radiocarbon dating to estimate how old the fossils are. Some of these fossils are over a hundred million years old.”

Essay Writing Guide – Key Phrases for Introducing Evidence

When incorporating evidence into an essay, you need to make sure it flows well. Try using some of these key phrases in your essay to help you introduce your evidence:

“The evidence clearly reveals…” “Analysis of the data suggests…” “This graph shows that…” “As shown by the information…” “This claim is supported by several authors, including…” “There seems to be a consensus regarding this…” “Popular opinion supports this idea…” “Popular opinion does not support this idea…” “Most experts agree…” “According to this study, we can deduce that…” “Over many years, this interpretation has developed…”

Essay Writing Guide – Key Phrases for Explaining Evidence

Once you’ve given your evidence, you need to be able explain it. Try using these phrases when explaining evidence in your essay:

“This means that…” “This evidence supports the claim that…” “This evidence supports this proposition because…” “It’s clear then, that this argument is supported by the evidence. This is because…” “If this evidence is true, then…” “This interpretation clearly supports the view that…” “This evidence suggests that…”

Essay Writing Guide – Key Phrases for Linking Evidence

Finally, you need to link your proposition, evidence, and explanation back to your main argument. Here are some phrases you can use to do this:

“Therefore, this analysis supports the central thesis of this essay…” “If followed to its logical conclusion, then this claim plays in favour of this essay’s core argument…” “The evidence and analysis presented here shows that…” “Due to this, it seems plausible that…” “In summary, it is shown that…” “While there are still many other ideas to consider, this proposition alone supports the view that…”

Essay Writing Guide – Key Phrases for Opposing Evidence

While most of the evidence you provide will support your argument, some essays will require you to examine counter-examples and evidence which opposes your central idea. So, make sure you clearly show that this evidence doesn’t damage your argument with the following phrases:

“While this evidence appears compelling, it doesn’t apply to these circumstances because…” “This counter-argument fails to acknowledge the following points: …” “While this is a popular counter-argument, it isn’t relevant to the focus of this essay, and therefore will not be discussed further.” “This claim relies on the premise that _____. The focus now will be to demonstrate that this premise is false.” “While this data appears to contradict the argument of this essay, this isn’t the case because…”

Essay Writing Guide – Key Phrases for Moving on to the Next Point

Eventually, you’ll need to move on to your next point. Here are some key phrases you can use to move from one point to another so that your essay flows better:

“Now that this claim has been suitably supported, the focus needs to shift to…” “The truth of this proposition has been clarified. Therefore, it is now appropriate to move to the next key argument in this essay: …” “This conclusion naturally leads to the next claim that…” “While this is compelling evidence, it is still not enough to logically reach the conclusion of this argument. It’s important to now discuss…” “While this theme is prominent in the text, others must also be considered, such as…” (Most relevant for English Literature essays)

Essay Writing Guide – Handy Phrases for Discussing Evidence

Finally, here are a few phrases that you can make use of to flesh out your arguments so that they read better:

“According to…” “Also…” “As well as…” “Based on…” “Clearly…” “Closely…” “Confirmed by…” “Evidently…” “For example…” “For instance…” “In addition…” “Therefore…” “This indicates that…” “This suggests…”

Essay Writing Guide – Conclusion

Whenever you make a new claim, support it with evidence. Evidence takes many different forms – find evidence that is appropriate to your subject or topic.

Start by introducing your argument. Then, give evidence. After that, explain your evidence. Finally, link your evidence back to your central argument.

Evidence is the fuel for your argument. Make sure you have enough of it to get you across the finish line!

Andy Bosworth

One thought on “ essay writing guide – using evidence in your arguments ”.

Clearly explained.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Free Aptitude Tests

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

Developing Evidence-Based Arguments from Texts

About this Strategy Guide

This guide provides teachers with strategies for helping students understand the differences between persuasive writing and evidence-based argumentation. Students become familiar with the basic components of an argument and then develop their understanding by analyzing evidence-based arguments about texts. Students then generate evidence-based arguments of texts using a variety of resources. Links to related resources and additional classroom strategies are also provided.

Research Basis

Strategy in practice, related resources.

Hillocks (2010) contends that argument is “at the heart of critical thinking and academic discourse, the kind of writing students need to know for success in college” (p. 25). He points out that “many teachers begin to teach some version of argument with the writing of a thesis statement, [but] in reality, good argument begins with looking at the data that are likely to become the evidence in an argument and that give rise to a thesis statement or major claim” (p. 26). Students need an understanding of the components of argument and the process through which careful examination of textual evidence becomes the beginnings of a claim about text.

- Begin by helping students understand the differences between persuasive writing and evidence-based argumentation: persuasion and argument share the goal of asserting a claim and trying to convince a reader or audience of its validity, but persuasion relies on a broader range of possible support. While argumentation tends to focus on logic supported by verifiable examples and facts, persuasion can use unverifiable personal anecdotes and a more apparent emotional appeal to make its case. Additionally, in persuasion, the claim usually comes first; then the persuader builds a case to convince a particular audience to think or feel the same way. Evidence-based argument builds the case for its claim out of available evidence. Solid understanding of the material at hand, therefore, is necessary in order to argue effectively. This printable resource provides further examples of the differences between persuasive and argumentative writing.

- One way to help students see this distinction is to offer a topic and two stances on it: one persuasive and one argumentative. Trying to convince your friend to see a particular movie with you is likely persuasion. Sure, you may use some evidence from the movie to back up your claim, but you may also threaten to get upset with him or her if he or she refuses—or you may offer to buy the popcorn if he or she agrees to go. Making the argument for why a movie is better (or worse) than the book it’s based on would be more argumentative, relying on analysis of examples from both works to build a case. Consider using resources from the ReadWriteThink lesson plan Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda: Analyzing World War II Posters

- The claim (that typically answers the question: “What do I think?”)

- The reasons (that typically answer the question: “Why do I think this?”)

- The evidence (that typically answers the question: “How do I know this is the case?”).

- Deepen students’ understanding of the components of argument by analyzing evidence-based arguments about texts. Project, for example, this essay on Gertrude in Hamlet and ask students to identify the claim, reasons, and evidence. Ask students to clarify what makes this kind of text an argument as opposed to persuasion. What might a persuasive take on the character of Gertrude sound like? (You may also wish to point out the absence of a counterargument in this example. Challenge students to offer one.)

- Point out that even though the claim comes first in the sample essay, the writer of the essay likely did not start there. Rather, he or she arrived at the claim as a result of careful reading of and thinking about the text. Share with students that evidence-based writing about texts always begins with close reading. See Close Reading of Literary Texts strategy guide for additional information.

- Guide students through the process of generating an evidence-based argument of a text by using the Designing an Evidence-based Argument Handout. Decide on an area of focus (such as the development of a particular character) and using a short text, jot down details or phrases related to that focus in the first space on the chart. After reading and some time for discussion of the character, have students look at the evidence and notice any patterns. Record these in the second space. Work with the students to narrow the patterns to a manageable list and re-read the text, this time looking for more instances of the pattern that you may have missed before you were looking for it. Add these references to the list.

- Use the evidence and patterns to formulate a claim in the last box. Point out to students that most texts can support multiple (sometimes even competing) claims, so they are not looking for the “one right thing” to say about the text, but they should strive to say something that has plenty of evidence to support it, but is not immediately self-evident. Claims can also be more or less complex, such as an outright claim (The character is X trait) as opposed to a complex claim (Although the character is X trait, he is also Y trait). For examples of development of a claim (a thesis is a type of claim), see the Developing a Thesis Handout for additional guidance on this point.

- Modeling Academic Writing Through Scholarly Article Presentations

- And I Quote

- Have students use the Evidence-Based Argument Checklist to revise and strengthen their writing.

More Ideas to Try

- This Strategy Guide focuses on making claims about text, with a focus on literary interpretation. The basic tenets of the guide, however, can apply to argumentation in multiple disciplines—e.g., a response to a Document-Based Question in social science, a lab report in science.

- For every argumentative claim that students develop for a text, have them try writing a persuasive claim about the text to continue building an understanding of their difference.

- After students have drafted an evidence-based argument, ask them to choose an alternative claim or a counterclaim to be sure their original claim is argumentative.

- Have students use the Evidence-Based Argument checklist to offer feedback to one another.

- Lesson Plans

- Professional Library

- Student Interactives

- Strategy Guides

Students prepare an already published scholarly article for presentation, with an emphasis on identification of the author's thesis and argument structure.

While drafting a literary analysis essay (or another type of argument) of their own, students work in pairs to investigate advice for writing conclusions and to analyze conclusions of sample essays. They then draft two conclusions for their essay, select one, and reflect on what they have learned through the process.

The Essay Map is an interactive graphic organizer that enables students to organize and outline their ideas for an informational, definitional, or descriptive essay.

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- How to write an essay outline | Guidelines & examples

How to Write an Essay Outline | Guidelines & Examples

Published on August 14, 2020 by Jack Caulfield . Revised on July 23, 2023.

An essay outline is a way of planning the structure of your essay before you start writing. It involves writing quick summary sentences or phrases for every point you will cover in each paragraph , giving you a picture of how your argument will unfold.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

Organizing your material, presentation of the outline, examples of essay outlines, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about essay outlines.

At the stage where you’re writing an essay outline, your ideas are probably still not fully formed. You should know your topic and have already done some preliminary research to find relevant sources , but now you need to shape your ideas into a structured argument.

Creating categories

Look over any information, quotes and ideas you’ve noted down from your research and consider the central point you want to make in the essay—this will be the basis of your thesis statement . Once you have an idea of your overall argument, you can begin to organize your material in a way that serves that argument.

Try to arrange your material into categories related to different aspects of your argument. If you’re writing about a literary text, you might group your ideas into themes; in a history essay, it might be several key trends or turning points from the period you’re discussing.

Three main themes or subjects is a common structure for essays. Depending on the length of the essay, you could split the themes into three body paragraphs, or three longer sections with several paragraphs covering each theme.

As you create the outline, look critically at your categories and points: Are any of them irrelevant or redundant? Make sure every topic you cover is clearly related to your thesis statement.

Order of information

When you have your material organized into several categories, consider what order they should appear in.

Your essay will always begin and end with an introduction and conclusion , but the organization of the body is up to you.

Consider these questions to order your material:

- Is there an obvious starting point for your argument?

- Is there one subject that provides an easy transition into another?

- Do some points need to be set up by discussing other points first?

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Within each paragraph, you’ll discuss a single idea related to your overall topic or argument, using several points of evidence or analysis to do so.

In your outline, you present these points as a few short numbered sentences or phrases.They can be split into sub-points when more detail is needed.

The template below shows how you might structure an outline for a five-paragraph essay.

- Thesis statement

- First piece of evidence

- Second piece of evidence

- Summary/synthesis

- Importance of topic

- Strong closing statement

You can choose whether to write your outline in full sentences or short phrases. Be consistent in your choice; don’t randomly write some points as full sentences and others as short phrases.

Examples of outlines for different types of essays are presented below: an argumentative, expository, and literary analysis essay.

Argumentative essay outline

This outline is for a short argumentative essay evaluating the internet’s impact on education. It uses short phrases to summarize each point.

Its body is split into three paragraphs, each presenting arguments about a different aspect of the internet’s effects on education.

- Importance of the internet

- Concerns about internet use

- Thesis statement: Internet use a net positive

- Data exploring this effect

- Analysis indicating it is overstated

- Students’ reading levels over time

- Why this data is questionable

- Video media

- Interactive media

- Speed and simplicity of online research

- Questions about reliability (transitioning into next topic)

- Evidence indicating its ubiquity

- Claims that it discourages engagement with academic writing

- Evidence that Wikipedia warns students not to cite it

- Argument that it introduces students to citation

- Summary of key points

- Value of digital education for students

- Need for optimism to embrace advantages of the internet

Expository essay outline

This is the outline for an expository essay describing how the invention of the printing press affected life and politics in Europe.

The paragraphs are still summarized in short phrases here, but individual points are described with full sentences.

- Claim that the printing press marks the end of the Middle Ages.

- Provide background on the low levels of literacy before the printing press.

- Present the thesis statement: The invention of the printing press increased circulation of information in Europe, paving the way for the Reformation.

- Discuss the very high levels of illiteracy in medieval Europe.

- Describe how literacy and thus knowledge and education were mainly the domain of religious and political elites.

- Indicate how this discouraged political and religious change.

- Describe the invention of the printing press in 1440 by Johannes Gutenberg.

- Show the implications of the new technology for book production.

- Describe the rapid spread of the technology and the printing of the Gutenberg Bible.

- Link to the Reformation.

- Discuss the trend for translating the Bible into vernacular languages during the years following the printing press’s invention.

- Describe Luther’s own translation of the Bible during the Reformation.

- Sketch out the large-scale effects the Reformation would have on religion and politics.

- Summarize the history described.

- Stress the significance of the printing press to the events of this period.

Literary analysis essay outline

The literary analysis essay outlined below discusses the role of theater in Jane Austen’s novel Mansfield Park .

The body of the essay is divided into three different themes, each of which is explored through examples from the book.

- Describe the theatricality of Austen’s works

- Outline the role theater plays in Mansfield Park

- Introduce the research question : How does Austen use theater to express the characters’ morality in Mansfield Park ?

- Discuss Austen’s depiction of the performance at the end of the first volume

- Discuss how Sir Bertram reacts to the acting scheme

- Introduce Austen’s use of stage direction–like details during dialogue

- Explore how these are deployed to show the characters’ self-absorption

- Discuss Austen’s description of Maria and Julia’s relationship as polite but affectionless

- Compare Mrs. Norris’s self-conceit as charitable despite her idleness

- Summarize the three themes: The acting scheme, stage directions, and the performance of morals

- Answer the research question

- Indicate areas for further study

If you want to know more about AI tools , college essays , or fallacies make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples or go directly to our tools!

- Ad hominem fallacy

- Post hoc fallacy

- Appeal to authority fallacy

- False cause fallacy

- Sunk cost fallacy

College essays

- Choosing Essay Topic

- Write a College Essay

- Write a Diversity Essay

- College Essay Format & Structure

- Comparing and Contrasting in an Essay

(AI) Tools

- Grammar Checker

- Paraphrasing Tool

- Text Summarizer

- AI Detector

- Plagiarism Checker

- Citation Generator

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

You will sometimes be asked to hand in an essay outline before you start writing your essay . Your supervisor wants to see that you have a clear idea of your structure so that writing will go smoothly.

Even when you do not have to hand it in, writing an essay outline is an important part of the writing process . It’s a good idea to write one (as informally as you like) to clarify your structure for yourself whenever you are working on an essay.

If you have to hand in your essay outline , you may be given specific guidelines stating whether you have to use full sentences. If you’re not sure, ask your supervisor.

When writing an essay outline for yourself, the choice is yours. Some students find it helpful to write out their ideas in full sentences, while others prefer to summarize them in short phrases.

You should try to follow your outline as you write your essay . However, if your ideas change or it becomes clear that your structure could be better, it’s okay to depart from your essay outline . Just make sure you know why you’re doing so.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Caulfield, J. (2023, July 23). How to Write an Essay Outline | Guidelines & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved August 29, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/academic-essay/essay-outline/

Is this article helpful?

Jack Caulfield

Other students also liked, how to create a structured research paper outline | example, a step-by-step guide to the writing process, how to write an argumentative essay | examples & tips, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Welcome to the new OASIS website! We have academic skills, library skills, math and statistics support, and writing resources all together in one new home.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Using Evidence: Analysis

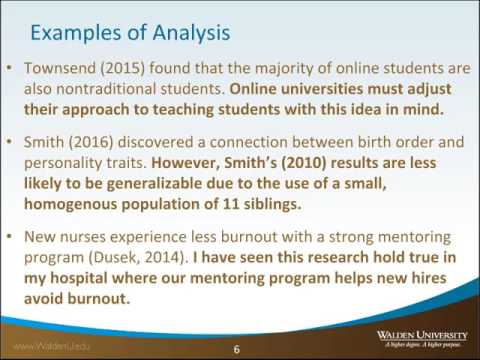

Beyond introducing and integrating your paraphrases and quotations, you also need to analyze the evidence in your paragraphs. Analysis is your opportunity to contextualize and explain the evidence for your reader. Your analysis might tell the reader why the evidence is important, what it means, or how it connects to other ideas in your writing.

Note that analysis often leads to synthesis , an extension and more complicated form of analysis. See our synthesis page for more information.

Example 1 of Analysis

Without analysis.

Embryonic stem cell research uses the stem cells from an embryo, causing much ethical debate in the scientific and political communities (Robinson, 2011). "Politicians don't know science" (James, 2010, p. 24). Academic discussion of both should continue (Robinson, 2011).

With Analysis (Added in Bold)

Embryonic stem cell research uses the stem cells from an embryo, causing much ethical debate in the scientific and political communities (Robinson, 2011). However, many politicians use the issue to stir up unnecessary emotion on both sides of the issues. James (2010) explained that "politicians don't know science," (p. 24) so scientists should not be listening to politics. Instead, Robinson (2011) suggested that academic discussion of both embryonic and adult stem cell research should continue in order for scientists to best utilize their resources while being mindful of ethical challenges.

Note that in the first example, the reader cannot know how the quotation fits into the paragraph. Also, note that the word both was unclear. In the revision, however, that the writer clearly (a) explained the quotations as well as the source material, (b) introduced the information sufficiently, and (c) integrated the ideas into the paragraph.

Example 2 of Analysis

Trow (1939) measured the effects of emotional responses on learning and found that student memorization dropped greatly with the introduction of a clock. Errors increased even more when intellectual inferiority regarding grades became a factor (Trow, 1939). The group that was allowed to learn free of restrictions from grades and time limits performed better on all tasks (Trow, 1939).

In this example, the author has successfully paraphrased the key findings from a study. However, there is no conclusion being drawn about those findings. Readers have a difficult time processing the evidence without some sort of ending explanation, an answer to the question so what? So what about this study? Why does it even matter?

Trow (1939) measured the effects of emotional responses on learning and found that student memorization dropped greatly with the introduction of a clock. Errors increased even more when intellectual inferiority regarding grades became a factor (Trow, 1939). The group that was allowed to learn free of restrictions from grades and time limits performed better on all tasks (Trow, 1939). Therefore, negative learning environments and students' emotional reactions can indeed hinder achievement.

Here the meaning becomes clear. The study’s findings support the claim the reader is making: that school environment affects achievement.

Analysis Video Playlist

Note that these videos were created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Quotation

- Next Page: Synthesis

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Cost of Attendance

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- Skip to main content

Join All-Access Reading…Doors Are Open! Click Here

- All-Access Login

- Freebie Library

- Search this website

Teaching with Jennifer Findley

Upper Elementary Teaching Blog

Text Evidence Activities and Strategies – Tips for Teaching Students to Find Text Evidence

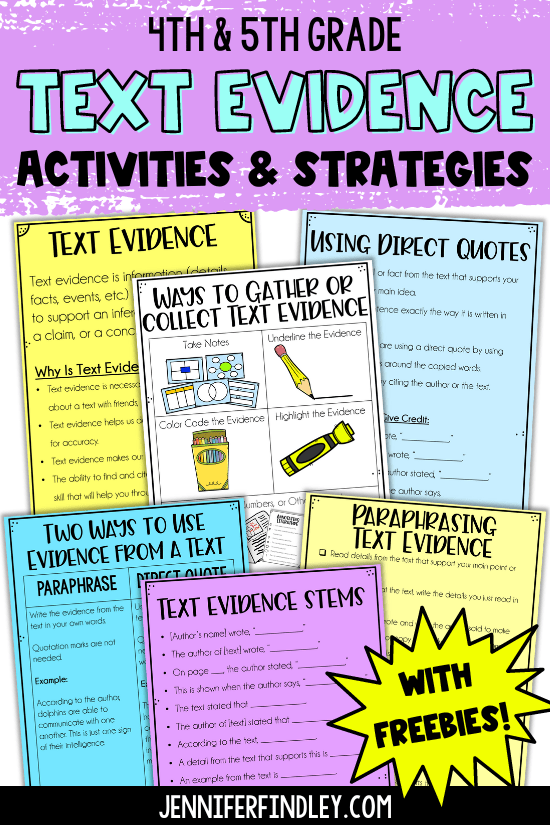

Teaching students to answer constructed response questions correctly and with sufficient text evidence can be quite the feat. A good starting point is to use an acronym such as RACE to help guide the students. But, that is just one part of instruction. The most difficult part is teaching students to find text evidence and then cite it appropriately to fully support their answer or analysis. This post will share my recommended text evidence activities, tips, and strategies (including several free resources).

What is Text Evidence?

Table of Contents

Text evidence is information (facts, details, quotes) from a fiction or nonfiction text that is used to support an inference, claim, opinion, or answer.

Students are often required to include text evidence to support their answers to constructed response questions and extended essays. Text evidence is also important to use when having discussions about texts. It helps back up the student’s thoughts on the text they are reading.

Tips Teaching Students to Find Text Evidence

1. introduce with read alouds and simple activities, teaching text evidence through read alouds.

I like to start introducing the skill of collecting text evidence early on in the year with relevant read alouds.

When reading a picture book or chapter book, give your students a focus question or task and then have them collect evidence by writing it on post-it notes throughout the read aloud.

Here are some examples that are easily adaptable to most read alouds.

Example Prompts for First Reads

- Find evidence of a theme used by the author to teach the reader a lesson.

- Find evidence of the text structure used by the author.

- Find evidence of the character traits displayed by the main character(s).

- Find evidence of the author’s opinion/viewpoint/perspective of the topic.

- Find evidence of the point of view/perspective used to tell the story.

Example Prompts for Second Reads

- Find evidence that the main character is XYZ (sad, greedy, brave, honest, etc.).

- Find evidence that the setting is XYZ (important to the story, the desert, a school, etc.).

- Find evidence that the animal is XYZ (beneficial to humans/ecosystem, harmful, endangered, etc).

This can be a new read aloud or even a familiar read aloud. Familiar read alouds are excellent for digging back into a text to specifically look for evidence to support a point, conclusion, or inference.

After gathering the text evidence, we discuss the evidence we found with partners and then as a class. You could keep this simple with just a class discussion or elevate it by listing the evidence on a chart, ranking the evidence from strongest to weakest, or having the students record their thoughts in a constructed response. For more tips on helping students with constructed response reading questions, click here.

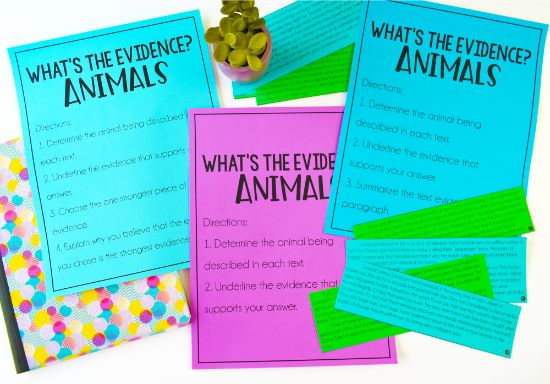

Teaching Text Evidence Through Simple Activities

After introducing the skill of finding relevant text evidence with read alouds, I like to use another text evidence activity that has the students reading texts and finding evidence to support one inference. For this, I use my “What’s the Text Evidence?” reading activities .

To complete the activities , the students will read texts (eight texts per set). They will use text evidence to determine the animal, career, or location (depending on the set) being described. They will then underline or summarize the text evidence that helped them infer.

This activity is a perfect next step because it is both non-threatening and engaging for students.

2. Teach the Importance of Finding Textual Evidence

I also really want to make sure my student understand why they are searching and citing evidence. We discuss how evidence helps in a few ways:

- Text evidence is necessary to support discussions about a text with friends, classmates, or teachers.

- Providing text evidence helps us double check our own answers for accuracy.

- Providing text evidence makes our answers valid and reliable.

- The ability to find and cite text evidence is a life-long skill that will help students throughout school and in their career choice.

Notice how I don’t mention the state test. This is intentional. I want the students to see the purpose beyond a test.

We typically discuss this early on when introducing text evidence and I try and sprinkle it in as it comes up throughout the year. This keeps it from seeming like chore and unnecessary busy work.

***Click here to grab the free printable shown (you can find it on page 2 of the PDF). You can use it to guide your instruction or to craft a text evidence anchor chart.

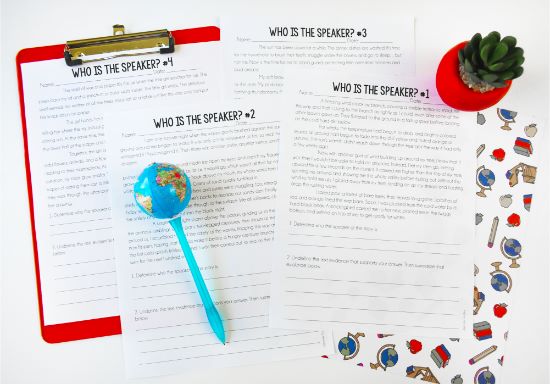

3. Require Text Evidence in Discussions

One easy way to help your students master text evidence is by requiring they use it in discussions. This can be whole class discussions or peer-to-peer discussions.

A very simple way to do this is using the stem:

I know…because…

Post the stem and remind your students to use this to defend and back up their answers.

As your students become comfortable with using evidence to back up their answers, add more sentence stems or sentence starters for your students to choose from.

However, I like to begin with the easiest one possible for my students while they are getting comfortable with including text evidence in their text discussions. More about the other sentence stems you can offer your students later in this post.

A great activity for discussing text evidence is my “Who is the Speaker?” Printables.

- To complete the printables, the students will read a half-page text from an unknown speaker/narrator. The students will use text evidence to determine who the speaker of the text is. They will also underline and summarize the text evidence that supports their answers.

- I like to partner my students up and give each one a different printable. They have to convince their partner of who the speaker of their text is by using text evidence.

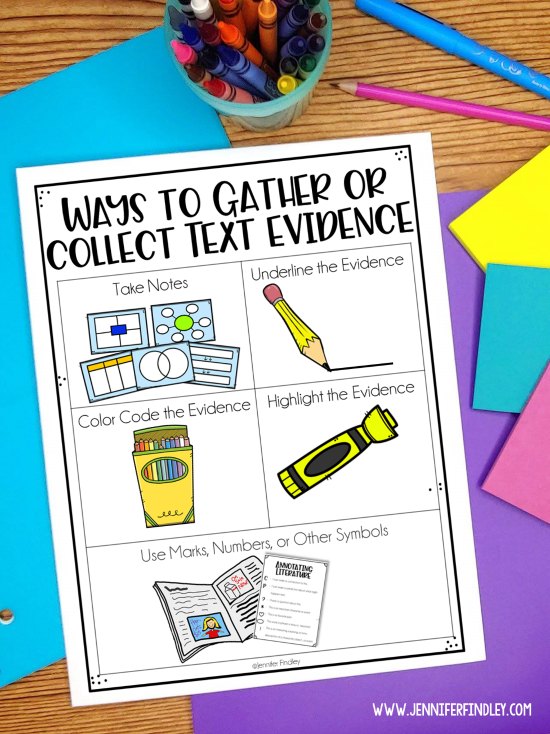

4. Teach Students Multiple Ways of Gathering Evidence

Another practical real-world skill involving evidence is modeling, teaching, and practicing multiple ways of gathering evidence.

Here are some examples:

- Taking notes

- Underlining

- Color coding —> For ready-to-use text evidence activities with color coding embedded, click here.

- Highlighting

- Using marks, numbers, or other symbols

***Click here to grab a printable version of the chart shown to help your students learn the ways they can gather or collect text evidence. You can find it on page 3 of the PDF.

After introducing and modeling the different ways to gather evidence, my students then chose the way that works best for them.

Also, you want to ensure they have practice finding text evidence while:

- Listening to a read aloud

- Reading a book

- Researching on the internet

To provide direct and explicit practice in this area, I use two resources:

1. Find the Evidence Printables

- To complete the text evidence printables, the students will read a grade level text (mix of fiction and nonfiction). They will then read to see what evidence they are looking for. They will reread the text, find required text evidence, and underline/highlight/or record it.

2. Find the Evidence Task Cards

- This is a similar activity but in task card format. To complete the task cards, the students will read the directions to see what specific text evidence they are looking for. They will then read the text and find that text evidence (again in whatever method of gathering you recommend or they choose). Finally, they will summarize the evidence.

Want to try these for FREE? Enter your information below to have 11 unique Text Evidence Task Cards sent to your email!

FREE Find the Evidence Task Cards

Join my email list to get the Find the Evidence Task Cards for FREE!

Success! Now check your email to grab your task cards!

There was an error submitting your subscription. Please try again.

Explicitly Teach Students How to Cite Text Evidence

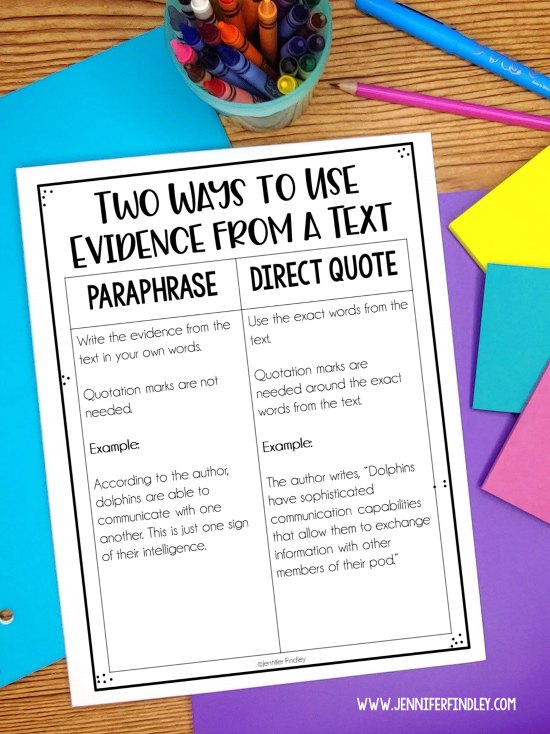

1. teach students to paraphrase evidence and use direct quotes.

Make sure that you explicitly teach the different ways to cite evidence from the text: quoting and paraphrasing. I do teach both types but, honestly, I prefer to have my students paraphrase the evidence in their own words. This keeps them from plagiarizing and having an answer that is not their original thoughts. With that being said, quoting directly from a text may be a requirement in your state, so I recommend looking into that.

***Click here to download the printables I use to guide my instruction on the different ways to cite text evidence. These can be found on pages 4-6 of the free download.

The Find the Evidence task cards mentioned in the above section work perfectly for practicing citing text evidence because the students’ jobs are to only find the relevant evidence and then summarize it.

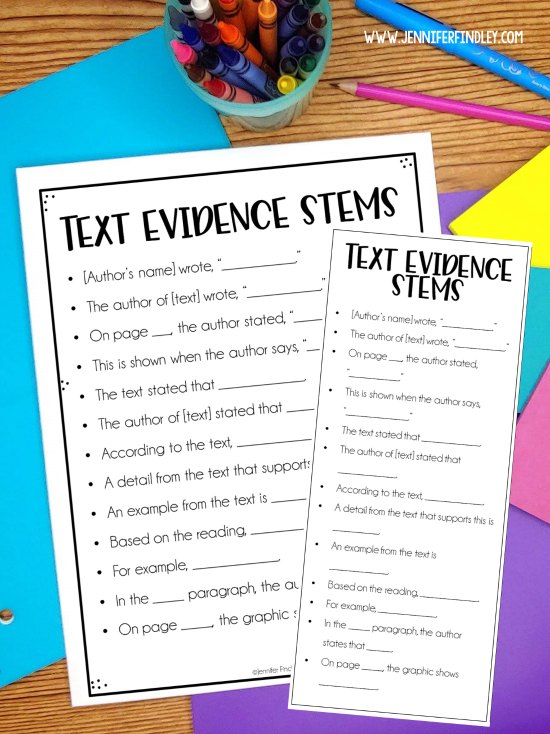

2. Provide Sentence Stems

Once your students have become more comfortable with pulling text evidence into their writing and discussions, it is time to provide them with more advanced options for bringing in that evidence.

Click here to download the printable I give my students (and the bookmark version). These are on pages 7 and 8 of the PDF.

3. Teach the Power of 3 (Three Pieces of Text Evidence)

I teach my students the power of 3. This means that they try to provide three pieces of evidence to support their answers. We do talk about how sometimes three pieces of evidence may not be available. However, teaching the power of 3 and that the more evidence you provide, the more difficult it is to refute the answer, keeps students searching for more relevant evidence to use.

**Click here to download the graphic organizer (and another option) shown that will help your students organize their three pieces of evidence. The organizers can be found on pages 9 and 10 of the PDF.

Teaching Students to Explain Text Evidence

The final step is teaching students to explain their text evidence. This is by far the trickiest skill in the entire text evidence process. It’s both difficult to teach and tricky for students to master. This is one reason I recommend waiting until your students have mastered the above skills before even tackling this part.

Here are some strategies I use to help my student understand what it means to explain their evidence, why it is important, and to keep them from just restating their evidence.

1. First, I introduce explaining evidence using a detective analogy. We talk about how detectives collect all of the important and relevant evidence for a case. But they don’t just plop the evidence down on their bosses’ desks. They have to explain how the evidence they collected proves his or her case. You could also use a lawyer/judge analogy for this as well.

2. Next, I provide simple sentence stems to both help my students explain their evidence and reinforce the importance of explaining it to begin with. I do a lot of modeling with this step. It is definitely not a “give them the list and forget about it” strategy. The stems are also very basic and simple for a reason. I want them to understand the purpose of explaining evidence and the difference between explaining it and just restating it. Eventually, the students will move away from this and use varied language (though sometimes this does require more modeling and support from me).

*** Click here to grab the free set of sentence stems posters to help your students explain their evidence.

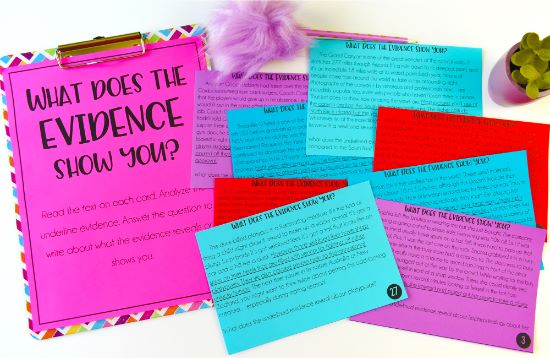

One text evidence activity that really helps with the skill of explaining text evidence is my “What Does the Text Evidence Reveal?” Task Cards .

For this activity, the students will read a text (mix of fiction and nonfiction). They will analyze the underlined evidence. They will then answer the question, which requires them to write about what the evidence reveals or shows them. This activity is perfect because it allows them to focus explicitly on explaining the text evidence and what it shows.

Want ALL of the Text Evidence Activities Featured on this Post?

Each activity is linked in the section that includes it, but I wanted to make sure that you saw that I have a money saving bundle of all of my text evidence activities. Click here or on the image below to check it out and read more.

Shop This Post

Text Evidence Activities | Citing Text Evidence

Share the knowledge, reader interactions.

April 18, 2020 at 11:09 am

Thank you so much!!!

June 17, 2020 at 2:50 pm

Hi Jennifer,

I love your activities and strategies to help students cite evidence from the text. I am excited to try some of them with my students because I haven’t found a method that is as effective as I would like it to be. I use RACE most often because it is easy for them to remember, but I felt like it isn’t enough. The ways you expanded on that method are great and I will definitely be using them.

One question I have that I’m hoping you have some advice or guidance on is about getting students to realize the importance of citing evidence. I frequently find myself in situations with students where they are either citing the wrong information because they don’t look back through the text or they don’t think they need to justify their thinking. I was wondering if this is something you face or have faced and if you have any suggestions for how to overcome it.

Using the methods you talk about here are definitely going to help with their motivation and engagement, but I am worried that I will still have similar problems. Any help would be greatly appreciated!

August 13, 2020 at 2:04 am

thank you veru much for he free material , for sure I will use it on my online classes. thanks you are really kind

July 26, 2023 at 11:00 pm

I am so overjoyed with excitement to find such overwhelming amount of strategies and hands on activities I can use starting day one of school. Where have you been all summer! I’m glad I still have a few days left of freedom, but I am going to spend them printing and organizing these great ideas. Thank you

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

TEACHING READING JUST GOT EASIER WITH ALL-ACCESS

Join All-Access Reading to get immediate access to the reading resources you need to:

- teach your reading skills

- support and grow your readers

- engage your students

- prepare them for testing

- and so much more!

You may also love these freebies!

Math Posters

Reading Posters

Morphology Posters

Grammar Posters

Welcome Friends!

I’m Jennifer Findley: a teacher, mother, and avid reader. I believe that with the right resources, mindset, and strategies, all students can achieve at high levels and learn to love learning. My goal is to provide resources and strategies to inspire you and help make this belief a reality for your students.

All Subjects

Argument Essay: Evidence

8 min read • june 18, 2024

Stephanie Kirk

We aren’t sure where it started, but many teachers use REHUGO to help students find evidence on the Argument FRQ . This acronym provides a quick check that can help you build logical evidence that supports your claim .

- R - Reading - Something you have read, fiction or nonfiction, that connects the given topic.

- E - Entertainment - A movie or song with dialogue or lyrics that present related ideas.

- H - History - An event, document, speech, or person from history that aligns with the given topic.

- U - Universal Truths - A common maxim or socially-accepted quote people tend to accept as truth.

- G - Government - A national or international current event or governmental situation related to the topic.

- O - Observations - Any cultural, technical, or societal trend that relates to the topic.

Suggested Guided Questions for the Argument FRQ

Now that you have a better understanding of the Argument FRQ’s expectations and scoring, let’s visit a sample prompt and add a few guided questions that you can use to help plan your own writings.

| In his book Canadian journalist Malcolm Gladwell (born 1963) writes: “To assume the best about another is the trait that has created modern society. Those occasions when our trusting nature gets violated are tragic. But the alternative—to abandon trust as a defense against predation and deception—is worse.”Write an essay that argues your position on the importance of . |

Guided Question 1: What does the prompt say? 📝

- Why do I do this? Understanding the concept or idea presented by the prompt is vital to planning a response that thoroughly addresses the prompt and stays on topic throughout. This is where you are going to BAT the PROMPT .

- Background : Gladwell asserts that society should trust each other in order to continue to be productive. Assuming the best about each other presents a better outcome than assuming the worst about each other.

- Advice : The new stable prompt wording does not give much advice, but you should revisit advice you learned in class or from us as Fiveable -- things like using Toulmin to plan your response and planning modes of development that help progress your reasoning.

- Task : Write an essay giving your position about the importance of trust. Specifically, is Gladwell right or wrong? And why? 🎥 Watch: AP Lang - Argumentation, Part I: It's a Trap!

Rhetorical Situation : When writing for AP Lang, it is important to consider the rhetorical situation and write in a manner that demonstrates an understanding of all elements of that situation.

- Context - the historical, social, and cultural movements in the time of the text

- Exigence - the urgency that leads to an action

- Purpose - the goal the speaker wants to achieve and the desired audience movement

- Persona - the “mask” shown to his/her audience

Guided Question 2: What do I think? 💡

Why do I do this? Taking a moment to brainstorm ideas can help organize thoughts and build an outline that you can revisit if you lose your train of thought in the stress of timed writing.

What does it look like? This might just be stream-of-consciousness in your head, cloud diagrams, or even bulleted notes on the side of your prompt, but it needs to end with a clear position statement you can use for your thesis statement . For example: Trust is important. It does suck to get betrayed though but having a positive outlook creates positive results. Thinking the worst makes people act negatively because they project in a way that leads toward the worst response. ⬇️