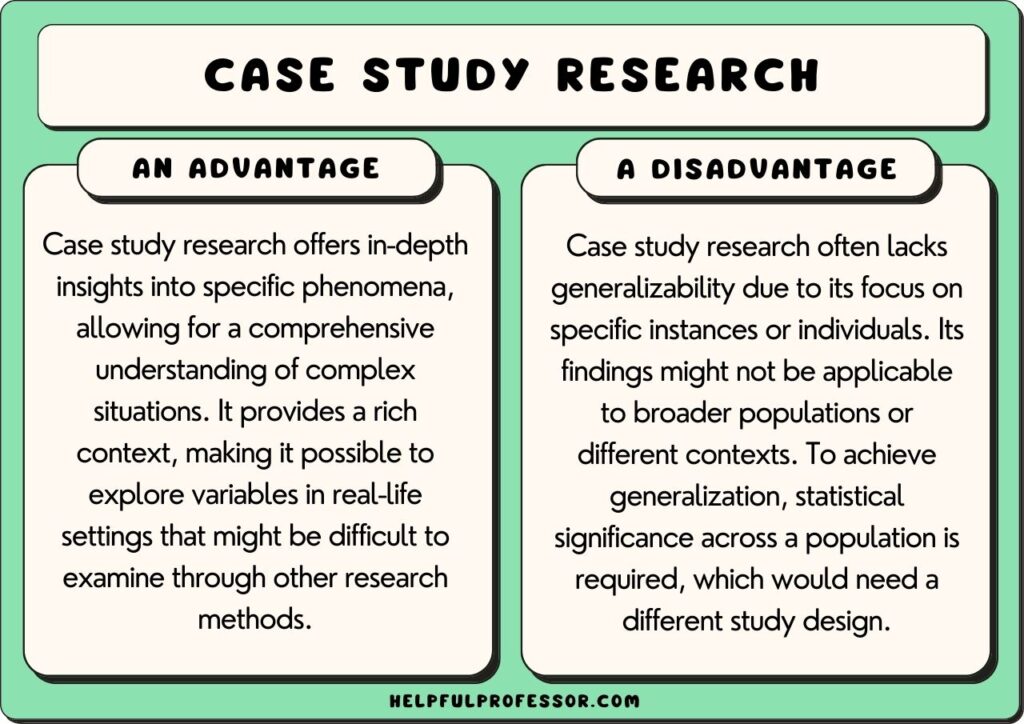

10 Case Study Advantages and Disadvantages

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

Learn about our Editorial Process

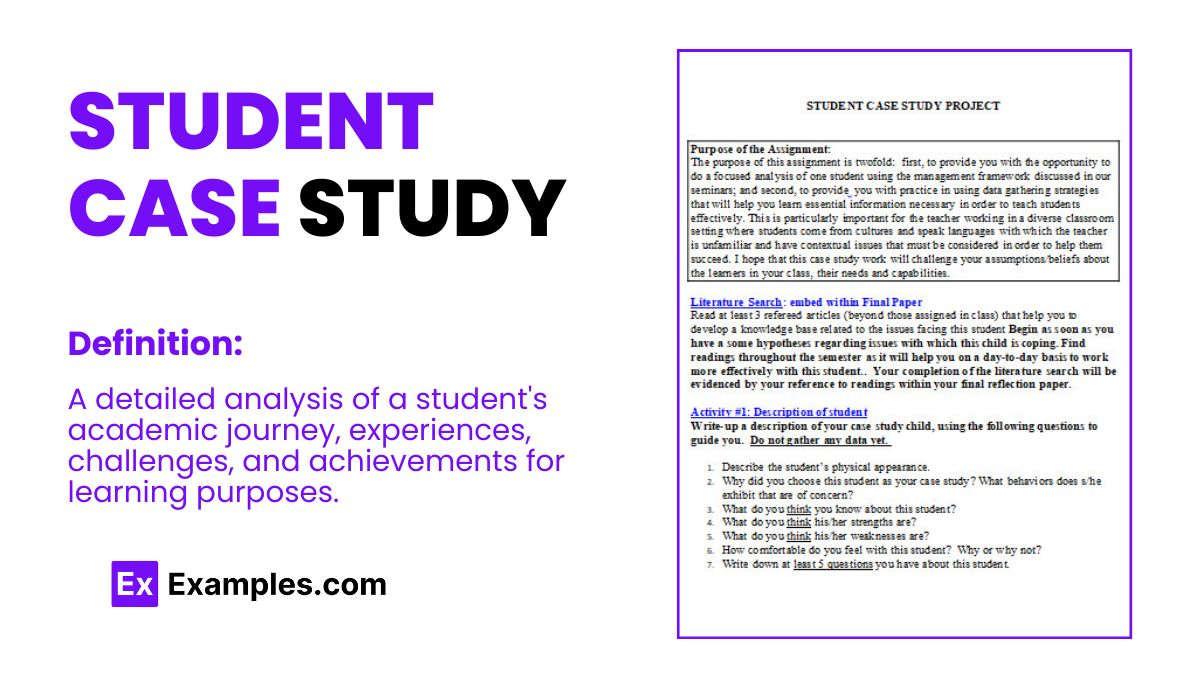

A case study in academic research is a detailed and in-depth examination of a specific instance or event, generally conducted through a qualitative approach to data.

The most common case study definition that I come across is is Robert K. Yin’s (2003, p. 13) quote provided below:

“An empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident.”

Researchers conduct case studies for a number of reasons, such as to explore complex phenomena within their real-life context, to look at a particularly interesting instance of a situation, or to dig deeper into something of interest identified in a wider-scale project.

While case studies render extremely interesting data, they have many limitations and are not suitable for all studies. One key limitation is that a case study’s findings are not usually generalizable to broader populations because one instance cannot be used to infer trends across populations.

Case Study Advantages and Disadvantages

1. in-depth analysis of complex phenomena.

Case study design allows researchers to delve deeply into intricate issues and situations.

By focusing on a specific instance or event, researchers can uncover nuanced details and layers of understanding that might be missed with other research methods, especially large-scale survey studies.

As Lee and Saunders (2017) argue,

“It allows that particular event to be studies in detail so that its unique qualities may be identified.”

This depth of analysis can provide rich insights into the underlying factors and dynamics of the studied phenomenon.

2. Holistic Understanding

Building on the above point, case studies can help us to understand a topic holistically and from multiple angles.

This means the researcher isn’t restricted to just examining a topic by using a pre-determined set of questions, as with questionnaires. Instead, researchers can use qualitative methods to delve into the many different angles, perspectives, and contextual factors related to the case study.

We can turn to Lee and Saunders (2017) again, who notes that case study researchers “develop a deep, holistic understanding of a particular phenomenon” with the intent of deeply understanding the phenomenon.

3. Examination of rare and Unusual Phenomena

We need to use case study methods when we stumble upon “rare and unusual” (Lee & Saunders, 2017) phenomena that would tend to be seen as mere outliers in population studies.

Take, for example, a child genius. A population study of all children of that child’s age would merely see this child as an outlier in the dataset, and this child may even be removed in order to predict overall trends.

So, to truly come to an understanding of this child and get insights into the environmental conditions that led to this child’s remarkable cognitive development, we need to do an in-depth study of this child specifically – so, we’d use a case study.

4. Helps Reveal the Experiences of Marginalzied Groups

Just as rare and unsual cases can be overlooked in population studies, so too can the experiences, beliefs, and perspectives of marginalized groups.

As Lee and Saunders (2017) argue, “case studies are also extremely useful in helping the expression of the voices of people whose interests are often ignored.”

Take, for example, the experiences of minority populations as they navigate healthcare systems. This was for many years a “hidden” phenomenon, not examined by researchers. It took case study designs to truly reveal this phenomenon, which helped to raise practitioners’ awareness of the importance of cultural sensitivity in medicine.

5. Ideal in Situations where Researchers cannot Control the Variables

Experimental designs – where a study takes place in a lab or controlled environment – are excellent for determining cause and effect . But not all studies can take place in controlled environments (Tetnowski, 2015).

When we’re out in the field doing observational studies or similar fieldwork, we don’t have the freedom to isolate dependent and independent variables. We need to use alternate methods.

Case studies are ideal in such situations.

A case study design will allow researchers to deeply immerse themselves in a setting (potentially combining it with methods such as ethnography or researcher observation) in order to see how phenomena take place in real-life settings.

6. Supports the generation of new theories or hypotheses

While large-scale quantitative studies such as cross-sectional designs and population surveys are excellent at testing theories and hypotheses on a large scale, they need a hypothesis to start off with!

This is where case studies – in the form of grounded research – come in. Often, a case study doesn’t start with a hypothesis. Instead, it ends with a hypothesis based upon the findings within a singular setting.

The deep analysis allows for hypotheses to emerge, which can then be taken to larger-scale studies in order to conduct further, more generalizable, testing of the hypothesis or theory.

7. Reveals the Unexpected

When a largescale quantitative research project has a clear hypothesis that it will test, it often becomes very rigid and has tunnel-vision on just exploring the hypothesis.

Of course, a structured scientific examination of the effects of specific interventions targeted at specific variables is extermely valuable.

But narrowly-focused studies often fail to shine a spotlight on unexpected and emergent data. Here, case studies come in very useful. Oftentimes, researchers set their eyes on a phenomenon and, when examining it closely with case studies, identify data and come to conclusions that are unprecedented, unforeseen, and outright surprising.

As Lars Meier (2009, p. 975) marvels, “where else can we become a part of foreign social worlds and have the chance to become aware of the unexpected?”

Disadvantages

1. not usually generalizable.

Case studies are not generalizable because they tend not to look at a broad enough corpus of data to be able to infer that there is a trend across a population.

As Yang (2022) argues, “by definition, case studies can make no claims to be typical.”

Case studies focus on one specific instance of a phenomenon. They explore the context, nuances, and situational factors that have come to bear on the case study. This is really useful for bringing to light important, new, and surprising information, as I’ve already covered.

But , it’s not often useful for generating data that has validity beyond the specific case study being examined.

2. Subjectivity in interpretation

Case studies usually (but not always) use qualitative data which helps to get deep into a topic and explain it in human terms, finding insights unattainable by quantitative data.

But qualitative data in case studies relies heavily on researcher interpretation. While researchers can be trained and work hard to focus on minimizing subjectivity (through methods like triangulation), it often emerges – some might argue it’s innevitable in qualitative studies.

So, a criticism of case studies could be that they’re more prone to subjectivity – and researchers need to take strides to address this in their studies.

3. Difficulty in replicating results

Case study research is often non-replicable because the study takes place in complex real-world settings where variables are not controlled.

So, when returning to a setting to re-do or attempt to replicate a study, we often find that the variables have changed to such an extent that replication is difficult. Furthermore, new researchers (with new subjective eyes) may catch things that the other readers overlooked.

Replication is even harder when researchers attempt to replicate a case study design in a new setting or with different participants.

Comprehension Quiz for Students

Question 1: What benefit do case studies offer when exploring the experiences of marginalized groups?

a) They provide generalizable data. b) They help express the voices of often-ignored individuals. c) They control all variables for the study. d) They always start with a clear hypothesis.

Question 2: Why might case studies be considered ideal for situations where researchers cannot control all variables?

a) They provide a structured scientific examination. b) They allow for generalizability across populations. c) They focus on one specific instance of a phenomenon. d) They allow for deep immersion in real-life settings.

Question 3: What is a primary disadvantage of case studies in terms of data applicability?

a) They always focus on the unexpected. b) They are not usually generalizable. c) They support the generation of new theories. d) They provide a holistic understanding.

Question 4: Why might case studies be considered more prone to subjectivity?

a) They always use quantitative data. b) They heavily rely on researcher interpretation, especially with qualitative data. c) They are always replicable. d) They look at a broad corpus of data.

Question 5: In what situations are experimental designs, such as those conducted in labs, most valuable?

a) When there’s a need to study rare and unusual phenomena. b) When a holistic understanding is required. c) When determining cause-and-effect relationships. d) When the study focuses on marginalized groups.

Question 6: Why is replication challenging in case study research?

a) Because they always use qualitative data. b) Because they tend to focus on a broad corpus of data. c) Due to the changing variables in complex real-world settings. d) Because they always start with a hypothesis.

Lee, B., & Saunders, M. N. K. (2017). Conducting Case Study Research for Business and Management Students. SAGE Publications.

Meir, L. (2009). Feasting on the Benefits of Case Study Research. In Mills, A. J., Wiebe, E., & Durepos, G. (Eds.). Encyclopedia of Case Study Research (Vol. 2). London: SAGE Publications.

Tetnowski, J. (2015). Qualitative case study research design. Perspectives on fluency and fluency disorders , 25 (1), 39-45. ( Source )

Yang, S. L. (2022). The War on Corruption in China: Local Reform and Innovation . Taylor & Francis.

Yin, R. (2003). Case Study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 10 Reasons you’re Perpetually Single

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 20 Montessori Toddler Bedrooms (Design Inspiration)

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 21 Montessori Homeschool Setups

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd-2/ 101 Hidden Talents Examples

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

- Nitin Nohria

Seven meta-skills that stick even if the cases fade from memory.

It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills in students. This article explains the importance of seven such skills: preparation, discernment, bias recognition, judgement, collaboration, curiosity, and self-confidence.

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

- Nitin Nohria is the George F. Baker Jr. and Distinguished Service University Professor. He served as the 10th dean of Harvard Business School, from 2010 to 2020.

Partner Center

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

Your content has been saved!

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

- Business Essentials

- Leadership & Management

- Credential of Leadership, Impact, and Management in Business (CLIMB)

- Entrepreneurship & Innovation

- Digital Transformation

- Finance & Accounting

- Business in Society

- For Organizations

- Support Portal

- Media Coverage

- Founding Donors

- Leadership Team

- Harvard Business School →

- HBS Online →

- Business Insights →

Business Insights

Harvard Business School Online's Business Insights Blog provides the career insights you need to achieve your goals and gain confidence in your business skills.

- Career Development

- Communication

- Decision-Making

- Earning Your MBA

- Negotiation

- News & Events

- Productivity

- Staff Spotlight

- Student Profiles

- Work-Life Balance

- AI Essentials for Business

- Alternative Investments

- Business Analytics

- Business Strategy

- Business and Climate Change

- Creating Brand Value

- Design Thinking and Innovation

- Digital Marketing Strategy

- Disruptive Strategy

- Economics for Managers

- Entrepreneurship Essentials

- Financial Accounting

- Global Business

- Launching Tech Ventures

- Leadership Principles

- Leadership, Ethics, and Corporate Accountability

- Leading Change and Organizational Renewal

- Leading with Finance

- Management Essentials

- Negotiation Mastery

- Organizational Leadership

- Power and Influence for Positive Impact

- Strategy Execution

- Sustainable Business Strategy

- Sustainable Investing

- Winning with Digital Platforms

5 Benefits of Learning Through the Case Study Method

- 28 Nov 2023

While several factors make HBS Online unique —including a global Community and real-world outcomes —active learning through the case study method rises to the top.

In a 2023 City Square Associates survey, 74 percent of HBS Online learners who also took a course from another provider said HBS Online’s case method and real-world examples were better by comparison.

Here’s a primer on the case method, five benefits you could gain, and how to experience it for yourself.

Access your free e-book today.

What Is the Harvard Business School Case Study Method?

The case study method , or case method , is a learning technique in which you’re presented with a real-world business challenge and asked how you’d solve it. After working through it yourself and with peers, you’re told how the scenario played out.

HBS pioneered the case method in 1922. Shortly before, in 1921, the first case was written.

“How do you go into an ambiguous situation and get to the bottom of it?” says HBS Professor Jan Rivkin, former senior associate dean and chair of HBS's master of business administration (MBA) program, in a video about the case method . “That skill—the skill of figuring out a course of inquiry to choose a course of action—that skill is as relevant today as it was in 1921.”

Originally developed for the in-person MBA classroom, HBS Online adapted the case method into an engaging, interactive online learning experience in 2014.

In HBS Online courses , you learn about each case from the business professional who experienced it. After reviewing their videos, you’re prompted to take their perspective and explain how you’d handle their situation.

You then get to read peers’ responses, “star” them, and comment to further the discussion. Afterward, you learn how the professional handled it and their key takeaways.

Learn more about HBS Online's approach to the case method in the video below, and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more.

HBS Online’s adaptation of the case method incorporates the famed HBS “cold call,” in which you’re called on at random to make a decision without time to prepare.

“Learning came to life!” said Sheneka Balogun , chief administration officer and chief of staff at LeMoyne-Owen College, of her experience taking the Credential of Readiness (CORe) program . “The videos from the professors, the interactive cold calls where you were randomly selected to participate, and the case studies that enhanced and often captured the essence of objectives and learning goals were all embedded in each module. This made learning fun, engaging, and student-friendly.”

If you’re considering taking a course that leverages the case study method, here are five benefits you could experience.

5 Benefits of Learning Through Case Studies

1. take new perspectives.

The case method prompts you to consider a scenario from another person’s perspective. To work through the situation and come up with a solution, you must consider their circumstances, limitations, risk tolerance, stakeholders, resources, and potential consequences to assess how to respond.

Taking on new perspectives not only can help you navigate your own challenges but also others’. Putting yourself in someone else’s situation to understand their motivations and needs can go a long way when collaborating with stakeholders.

2. Hone Your Decision-Making Skills

Another skill you can build is the ability to make decisions effectively . The case study method forces you to use limited information to decide how to handle a problem—just like in the real world.

Throughout your career, you’ll need to make difficult decisions with incomplete or imperfect information—and sometimes, you won’t feel qualified to do so. Learning through the case method allows you to practice this skill in a low-stakes environment. When facing a real challenge, you’ll be better prepared to think quickly, collaborate with others, and present and defend your solution.

3. Become More Open-Minded

As you collaborate with peers on responses, it becomes clear that not everyone solves problems the same way. Exposing yourself to various approaches and perspectives can help you become a more open-minded professional.

When you’re part of a diverse group of learners from around the world, your experiences, cultures, and backgrounds contribute to a range of opinions on each case.

On the HBS Online course platform, you’re prompted to view and comment on others’ responses, and discussion is encouraged. This practice of considering others’ perspectives can make you more receptive in your career.

“You’d be surprised at how much you can learn from your peers,” said Ratnaditya Jonnalagadda , a software engineer who took CORe.

In addition to interacting with peers in the course platform, Jonnalagadda was part of the HBS Online Community , where he networked with other professionals and continued discussions sparked by course content.

“You get to understand your peers better, and students share examples of businesses implementing a concept from a module you just learned,” Jonnalagadda said. “It’s a very good way to cement the concepts in one's mind.”

4. Enhance Your Curiosity

One byproduct of taking on different perspectives is that it enables you to picture yourself in various roles, industries, and business functions.

“Each case offers an opportunity for students to see what resonates with them, what excites them, what bores them, which role they could imagine inhabiting in their careers,” says former HBS Dean Nitin Nohria in the Harvard Business Review . “Cases stimulate curiosity about the range of opportunities in the world and the many ways that students can make a difference as leaders.”

Through the case method, you can “try on” roles you may not have considered and feel more prepared to change or advance your career .

5. Build Your Self-Confidence

Finally, learning through the case study method can build your confidence. Each time you assume a business leader’s perspective, aim to solve a new challenge, and express and defend your opinions and decisions to peers, you prepare to do the same in your career.

According to a 2022 City Square Associates survey , 84 percent of HBS Online learners report feeling more confident making business decisions after taking a course.

“Self-confidence is difficult to teach or coach, but the case study method seems to instill it in people,” Nohria says in the Harvard Business Review . “There may well be other ways of learning these meta-skills, such as the repeated experience gained through practice or guidance from a gifted coach. However, under the direction of a masterful teacher, the case method can engage students and help them develop powerful meta-skills like no other form of teaching.”

How to Experience the Case Study Method

If the case method seems like a good fit for your learning style, experience it for yourself by taking an HBS Online course. Offerings span eight subject areas, including:

- Business essentials

- Leadership and management

- Entrepreneurship and innovation

- Digital transformation

- Finance and accounting

- Business in society

No matter which course or credential program you choose, you’ll examine case studies from real business professionals, work through their challenges alongside peers, and gain valuable insights to apply to your career.

Are you interested in discovering how HBS Online can help advance your career? Explore our course catalog and download our free guide —complete with interactive workbook sections—to determine if online learning is right for you and which course to take.

About the Author

Using Case Studies to Teach

Why Use Cases?

Many students are more inductive than deductive reasoners, which means that they learn better from examples than from logical development starting with basic principles. The use of case studies can therefore be a very effective classroom technique.

Case studies are have long been used in business schools, law schools, medical schools and the social sciences, but they can be used in any discipline when instructors want students to explore how what they have learned applies to real world situations. Cases come in many formats, from a simple “What would you do in this situation?” question to a detailed description of a situation with accompanying data to analyze. Whether to use a simple scenario-type case or a complex detailed one depends on your course objectives.

Most case assignments require students to answer an open-ended question or develop a solution to an open-ended problem with multiple potential solutions. Requirements can range from a one-paragraph answer to a fully developed group action plan, proposal or decision.

Common Case Elements

Most “full-blown” cases have these common elements:

- A decision-maker who is grappling with some question or problem that needs to be solved.

- A description of the problem’s context (a law, an industry, a family).

- Supporting data, which can range from data tables to links to URLs, quoted statements or testimony, supporting documents, images, video, or audio.

Case assignments can be done individually or in teams so that the students can brainstorm solutions and share the work load.

The following discussion of this topic incorporates material presented by Robb Dixon of the School of Management and Rob Schadt of the School of Public Health at CEIT workshops. Professor Dixon also provided some written comments that the discussion incorporates.

Advantages to the use of case studies in class

A major advantage of teaching with case studies is that the students are actively engaged in figuring out the principles by abstracting from the examples. This develops their skills in:

- Problem solving

- Analytical tools, quantitative and/or qualitative, depending on the case

- Decision making in complex situations

- Coping with ambiguities

Guidelines for using case studies in class

In the most straightforward application, the presentation of the case study establishes a framework for analysis. It is helpful if the statement of the case provides enough information for the students to figure out solutions and then to identify how to apply those solutions in other similar situations. Instructors may choose to use several cases so that students can identify both the similarities and differences among the cases.

Depending on the course objectives, the instructor may encourage students to follow a systematic approach to their analysis. For example:

- What is the issue?

- What is the goal of the analysis?

- What is the context of the problem?

- What key facts should be considered?

- What alternatives are available to the decision-maker?

- What would you recommend — and why?

An innovative approach to case analysis might be to have students role-play the part of the people involved in the case. This not only actively engages students, but forces them to really understand the perspectives of the case characters. Videos or even field trips showing the venue in which the case is situated can help students to visualize the situation that they need to analyze.

Accompanying Readings

Case studies can be especially effective if they are paired with a reading assignment that introduces or explains a concept or analytical method that applies to the case. The amount of emphasis placed on the use of the reading during the case discussion depends on the complexity of the concept or method. If it is straightforward, the focus of the discussion can be placed on the use of the analytical results. If the method is more complex, the instructor may need to walk students through its application and the interpretation of the results.

Leading the Case Discussion and Evaluating Performance

Decision cases are more interesting than descriptive ones. In order to start the discussion in class, the instructor can start with an easy, noncontroversial question that all the students should be able to answer readily. However, some of the best case discussions start by forcing the students to take a stand. Some instructors will ask a student to do a formal “open” of the case, outlining his or her entire analysis. Others may choose to guide discussion with questions that move students from problem identification to solutions. A skilled instructor steers questions and discussion to keep the class on track and moving at a reasonable pace.

In order to motivate the students to complete the assignment before class as well as to stimulate attentiveness during the class, the instructor should grade the participation—quantity and especially quality—during the discussion of the case. This might be a simple check, check-plus, check-minus or zero. The instructor should involve as many students as possible. In order to engage all the students, the instructor can divide them into groups, give each group several minutes to discuss how to answer a question related to the case, and then ask a randomly selected person in each group to present the group’s answer and reasoning. Random selection can be accomplished through rolling of dice, shuffled index cards, each with one student’s name, a spinning wheel, etc.

Tips on the Penn State U. website: https://sites.psu.edu/pedagogicalpractices/case-studies/

If you are interested in using this technique in a science course, there is a good website on use of case studies in the sciences at the National Science Teaching Association.

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

Explore more.

- Case Teaching

- Perspectives

D uring my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

Alumni responses varied but tended to follow a pattern. Almost no one referred to a specific business concept they learned. Many mentioned close friendships or the classmate who became a business or life partner. Most often, though, alumni highlighted a personal quality or skill such as “increased self-confidence” or “the ability to advocate for a point of view” or “knowing how to work closely with others to solve problems.” And when I asked how they developed these capabilities, they inevitably mentioned the magic of the case method.

Harvard Business School pioneered the use of case studies to teach management in 1921. As we commemorate 100 years of case teaching, much has been written about the effectiveness of this method. I agree with many of these observations. Cases expose students to real business dilemmas and decisions. Cases teach students to size up business problems quickly while considering the broader organizational, industry, and societal context. Students recall concepts better when they are set in a case, much as people remember words better when used in context. Cases teach students how to apply theory in practice and how to induce theory from practice. The case method cultivates the capacity for critical analysis, judgment, decision-making, and action.

“Cases teach students how to apply theory in practice and how to induce theory from practice. The case method cultivates the capacity for critical analysis, judgment, decision-making, and action.”

There is a word that aptly captures the broader set of capabilities our alumni reported they learned from the case method. That word is meta-skills, and these meta-skills are a benefit of case study instruction that those who’ve never been exposed to the method may undervalue.

Educators define meta-skills as a group of long-lasting abilities that allow someone to learn new things more quickly. When parents encourage a child to learn to play a musical instrument, for instance, beyond the hope of instilling musical skills (which some children will master and others may not), they may also appreciate the benefit the child derives from deliberate, consistent practice. This meta-skill is valuable for learning many other things beyond music.

In the same vein, let me suggest seven vital meta-skills students gain from the case method:

1. Preparation

There is no place for students to hide in the moments before the famed “ cold call ”—when the teacher can ask any student at random to open the case discussion. Decades after they graduate, students will vividly remember cold calls when they or someone else froze with fear, or when they rose to nail the case even in the face of a fierce grilling by the professor.

The case method creates high-powered incentives for students to prepare. Students typically spend several hours reading, highlighting, and debating cases before class, sometimes alone and sometimes in groups. The number of cases to be prepared can be overwhelming by design.

Learning to be prepared—to read materials in advance, prioritize, identify the key issues, and have an initial point of view—is a meta-skill that helps people succeed in a broad range of professions and work situations. We have all seen how the prepared person, who knows what they are talking about, can gain the trust and confidence of others in a business meeting. The habits of preparing for a case discussion can transform a student into that person.

2. Discernment

Many cases are long. A typical case may include history, industry background, a cast of characters, dialogue, financial statements, source documents, or other exhibits. Some material may be digressive or inessential. Cases often have holes—critical pieces of information that are missing.

The case method forces students to identify and focus on what’s essential, ignore the noise, skim when possible, and concentrate on what matters, meta-skills required for every busy executive confronted with the paradox of simultaneous information overload and information paucity. As one alumnus pithily put it, “The case method helped me learn how to separate the wheat from the chaff.”

“The case method forces students to identify and focus on what’s essential, ignore the noise, skim when possible, and concentrate on what matters.”

3. Bias Recognition

Students often have an initial reaction to a case stemming from their background or earlier work and life experiences. For instance, people who have worked in finance may be biased to view cases through a financial lens. However, effective general managers must understand and empathize with various stakeholders, and if someone has a natural tendency to favor one viewpoint over another, discussing dozens of cases will help reveal that bias. Armed with this self-understanding, students can correct that bias or learn to listen more carefully to classmates whose different viewpoints may help them see beyond their own biases.

Recognizing and correcting personal bias can be an invaluable meta-skill in business settings when leaders inevitably have to work with people from different functions, backgrounds, and perspectives.

4. Judgment

Cases put students into the role of the case protagonist and force them to make and defend a decision. The format leaves room for nuanced discussion, but not for waffling: Teachers push students to choose an option, knowing full well that there is rarely one correct answer.

Indeed, most cases are meant to stimulate a discussion rather than highlight effective or ineffective management practice. Across the cases they study, students get feedback from their classmates and their teachers about when their decisions are more or less compelling. It enables them to develop the judgment of making decisions under uncertainty, communicating that decision to others, and gaining their buy-in—all essential leadership skills. Leaders earn respect for their judgment. It is something students in the case method get lots of practice honing.

5. Collaboration

It is better to make business decisions after extended give-and-take, debate, and deliberation. As in any team sport, people get better at working collaboratively with practice. Discussing cases in small study groups, and then in the classroom, helps students practice the meta-skill of collaborating with others. Our alumni often say they came away from the case method with better skills to participate in meetings and lead them.

Orchestrating a good collaborative discussion in which everyone contributes, every viewpoint is carefully considered, and yet a thoughtful decision is made in the end is the arc of any good case discussion. Although teachers play the primary role in this collaborative process during their time at the school, it is an art that students of the case method internalize and get better at when they get to lead discussions.

6. Curiosity

Cases expose students to lots of different situations and roles. Across cases, they get to assume the role of entrepreneur, investor, functional leader, or CEO in a range of different industries and sectors. Each case offers an opportunity for students to see what resonates with them, what excites them, what bores them, and which roles they could imagine inhabiting in their careers.

Cases stimulate curiosity about the range of opportunities in the world and the many ways that students can make a difference as leaders. This curiosity serves them well throughout their lives. It makes them more agile, more adaptive, and more open to doing a wider range of things in their careers.

“Cases stimulate curiosity about the range of opportunities in the world and the many ways that students can make a difference as leaders.”

7. Self-Confidence

Students must inhabit roles during a case study that far outstrip their prior experience or capability, often as leaders of teams or entire organizations in unfamiliar settings. “What would you do if you were the case protagonist?” is the most common question in a case discussion. Even though they are imaginary and temporary, these “stretch” assignments increase students' self-confidence that they can rise to the challenge.

In our program, students can study 500 cases over two years, and the range of roles they are asked to assume increases the range of situations they believe they can tackle. Speaking up in front of 90 classmates feels risky at first, but students become more comfortable taking that risk over time. Knowing that they can hold their own in a highly curated group of competitive peers enhances student confidence. Often, alumni describe how discussing cases made them feel prepared for much bigger roles or challenges than they’d imagined they could handle before their MBA studies. Self-confidence is difficult to teach or coach, but the case study method seems to instill it in people.

The Lifelong Benefits of Case Method Instruction

There may well be other ways of learning these meta-skills, such as the repeated experience gained through practice or guidance from a gifted coach. However, under the direction of a masterful teacher, the case method can engage students and help them develop powerful meta-skills like no other form of teaching. This quickly became apparent when case teaching was introduced in 1921—and it’s even truer today.

For educators and students, recognizing the value of these meta-skills can offer perspective on the broader goals of their work together. Returning to the example of music lessons, it may be natural for a music teacher or their students to judge success by a simple measure: Does the student learn to play the instrument well? But when everyone involved recognizes the broader meta-skills that instrumental instruction can instill—and that even those who bumble their way through Bach may still derive lifelong benefits from their instruction—it may lead to a deeper appreciation of this work.

For recruiters and employers, recognizing the long-lasting set of benefits that accrue from studying via the case method can be a valuable perspective in assessing candidates and plotting their potential career trajectories.

And while we must certainly use the case method’s centennial to imagine yet more powerful ways of educating students in the future, let us be sure to assess these innovations for the meta-skills they might instill as much as the subject matter mastery they might enable.

This article was originally posted by HBR.org .

Nitin Nohria is the former dean of Harvard Business School.

Related Articles

We use cookies to understand how you use our site and to improve your experience, including personalizing content. Learn More . By continuing to use our site, you accept our use of cookies and revised Privacy Policy .

"Own Your Knowledge" expand_more

We want students to create their own meanings from their experiences both in and beyond class. Lecture and readings are important, of course. But they are not the best way to own knowledge. Connecting theories, knowledge, and practices you hear from the class to your lived experiences begins with an authentic question that matters to you. Simply, what do you care about? And why does it matter to you? It does echo the first principle of the ten. Then, how do you proceed to the next steps? You engage in the inquiry cycle originally drawn from John Dewey.

Once you come up with an essential question that connects with your life, you can investigate through multiple methods, sources, and media. Any tangible products can derive from investigation––the tangible product in our class will be your case study. Note that your creation is inseparable from other steps, especially discussion and reflections. You need to discuss meanings and lessons of your creation with others and then go back to previous steps, namely investigation and creation, and tinker with your creation.

In the end, you and your audience––now your instructors and peers but beyond that down the road––are all invited to a broad vista to “look back” at the whole inquiry process and generate further meanings together. These five steps, of course, are neither linear nor discrete. Rather, they are embedded in one another. The point here is that this inquiry cycle can break down your inquiry processes––typically complicated and less articulate––into small pieces and monitor your own meaning making experiences. In completing this process you claim the ownership of knowledge. Please see the related posts: “ The YPP Action Frame with Inquiry-Based Learning II: "Small Inquiry" and "Big Inquiry" ” and “ The YPP Action Frame with Inquiry-Based Learning I: An Inquiry Cycle ” from the YPP Action Frame site .

[Case Study] How Students Conduct Case Studies expand_more

Team up with your peers (2 or 3 students in one group) to conduct a case study. What kind of case study? You could start by writing a captivating story around the case. We will discuss several real world cases during class, and you can imagine emulating one of them. The case study can be situated in particular theories and perspectives we discuss in class. The cases we address there are quite lengthy, but you are not necessarily required to write such a long paper. What matters most is the content and message you want to deliver through the case; this project is an exercise both to express your creativity and practice research skills. It is broken into small pieces ( P1, P2, P3-1, P3-2, and P3-3 ) to help you complete the end project (P4) effectively.

[Case Study] P0 expand_more

P0 [Not Graded]. Please consult with Chaebong ( [email protected] ) regarding the case selection by September 29, 2016.

[Case Study] P1 expand_more

P1. “Why it matters to me/us”

- The case can be any group, any organization, or any single person in connection with a large theme of the course: Youth, media, and participatory politics. Be creative and flexible in choosing your case.

- Introduce the case , explaining why the case matters to you, what you want to talk about in the case, spelling out main issues you would want to explore.

- You are welcome to challenge the existing viewpoints and values, as well as defending them. For instance, we see the three values––equity, efficacy, and self-protection––as “timeless but not dogmatic” (quoted from Tom Hayden’s reflection about the Port Huron Statement at 50 (Links to an external site.) ). If you find other ideas and values pertain to your own case, please bring them to our class through your own inquiry-cycle.

- Who would you want to talk with you?

- What would you observe?

- What existing data would you want to explore?

- How do we analyze them?

- What is your position in the case?

- Due: Week 5 (A 6 to 8 page statement, or longer if desired)

- Please talk with Chaebong beforehand

[Case Study] P3 (P3-1, P3-2, and P3-3) expand_more

P3-1. Presentation: Week 12

P3-2. Add Discussions and Conclusion based on feedback from the presentation

P3-3. Individual reflection note. This portion is spared for individual reflection about the collaborative research-learning activities. As members on the same team, you share a common ground for the case, but that does not necessarily mean that you share exact thoughts with others. Thus, this individual reflection paper gives you an opportunity to flesh out your own thought or ideas around your case or your collaborative thinking activities.

[Case Study] P4 expand_more

Compile P1 to P3-3

Submit by due date: By 5 pm on December 17, 2016

Featured Posts

Grade 8 Civics Workbook Available Online!

Student-Led Civics Workbook

10 Questions Primer

Facing History and Ourselves with 10 Questions for Young Changemakers –– Student Activism

Facing History with the YPP Action Frame––Focusing on Eyes on the Prize: Ain’t Scared of Your Jails

Danielle Allen on Civic Agency in a Digital Age

Blog posts by month

November 2016 (1)

October 2016 (2)

August 2016 (2)

June 2016 (1)

April 2016 (3)

5 Key Benefits of a Case-Based Learning Approach

dans

There are many methodologies and approaches to learning that span all levels and forms of education. Case-based learning is gaining traction as an approach to learning that has many benefits for students.

This method uses collaborative discussions around real-world case studies to not only improve learning outcomes, but also help students develop a number of invaluable, transferable skills .

What is a Case-Based Learning Approach?

Case-based learning centres around the use of concrete examples or case studies. Students will examine the case study as a group, building their knowledge while putting their analytical skills into practice by assessing the problem and coming up with potential solutions . Often, the discussion is driven by the group members, with the instructor or tutor acting as a facilitator .

This method frequently makes use of real-world examples, or may rely on detailed models that closely resemble an actual case. For example, business students may study the history of real companies and how they overcame key challenges or barriers to growth. Alternatively, they could be called upon to analyse fictional companies in accurate scenarios.

Instructors may use various types of case studies, such as:

- Intrinsic case studies seek to understand a unique brand or subject, and how it is affected by its environment.

- Exploratory case studies use individual examples to explore broader issues.

- Explanatory case studies seek to hone in on the cause, and sometimes the effects, of a particular event.

- Descriptive case studies seek to tell a story and, unlike other types of case studies, may include a conclusion with quantifiable results.

Benefits of a Case-Based Learning Approach

Case-based learning is very common in medical education, but it is being increasingly adopted in other fields thanks to its numerous advantages.

It Promotes Critical Thinking

A key part of the case-based learning method is examining and assessing real or fictitious case studies. In doing so, students have the opportunity to hone their critical thinking skills.

Critical thinking is a crucial skill that is highly advantageous in a range of roles across various sectors and is one of skills in most demand by employers . In essence, it is the ability to address problems and come up with better solutions: a skill that is essential in just about any context.

Through case-based learning, students can practise their critical thinking on real-world examples, preparing them to apply the same approach in a professional setting after they graduate.

It Exposes Students to Different Approaches

Through discussing real-life cases and examples in a group setting, students gain exposure to other points of view and perspectives. By working together as a group, students will consider different aspects of a problem, come up with new solutions, and be able to think outside the box.

Perhaps even more importantly, they get to know other thought processes and methods for approaching a problem. This insight can be incredibly useful and help students to further develop their own critical thinking process.

It Helps Students Develop Collaboration Skills

Case-based learning typically requires students to critically assess case studies as a group, and discuss the challenges, solutions, and lessons they can draw from the example. This process involves a high degree of collaboration and communication, so helps students to practise and develop a range of skills necessary for productive teamwork. These skills include clearly communicating their point of view, listening to others’ opinions, disagreeing in a productive way, and dealing with conflict. All of these are invaluable skills in virtually any professional setting.

It Fosters Self-Reflection

How we view situations and the conclusions we reach are often heavily influenced by our own experiences and biases. Being able to reflect on your own thought processes and identify these biases can help you to more objectively assess problems and come up with better solutions.

The case-based learning method encourages students to break down situations, and dive deeper into their own assessments and opinions. This can be extremely useful in fostering meta-cognition, the ability to critically assess your own thought process, allowing you to identify any gaps in your thinking and develop stronger solutions to problems.

It Strengthens Relationships

Finally, by working together to solve case studies, students participating in case-based learning will develop stronger relationships with their peers. A closer student cohort can have a wide range of advantages, from better learning outcomes to group support and future networking opportunities.

Additionally, as part of studying real-world cases, learners may have the opportunity to work with professionals and industry leaders. This gives rise to further, invaluable learning and networking opportunities.

Optimise Your Learning with EDHEC

EDHEC online programs are all based on a case-based learning approach, allowing students to develop their collaboration and critical thinking skills, while expanding their knowledge through case studies related to the reality of businesses.

Our online courses use a combination of the latest technology and innovative training methods to deliver the highest standards of education to a global student cohort.

Explore our online programs to learn more about our case-based learning methods.

Subscribe to our newsletter BOOST, to receive our career tips and business insights every month.

Related articles

Back to school at 40? Why it’s worth investing in executive education as a mature student

Studying at an established online institution like EDHEC is ideal for mature students, offering a learning environment that is perfectly suited to busy professionals.

The impact of Data in the pharmaceutical industry: a conversation with Erdem Cinar, online Master’s student at EDHEC

As data grows in importance, companies can no longer ignore the benefits of analytical tools.

EDHEC Business School Wins FOME 2023 Learning Design Innovation Awards

EDHEC Business School is proud to announce its first place at FOME 2023 Learning Design Innovation Awards, highlighting the school's commitment to pushing the boundaries of education and embracing innovative pedagogy.

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Value of Case-Based Learning within STEM Courses: Is It the Method or Is It the Student?

Ashley rhodes, abigail wilson, timothy rozell.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

*Address correspondence to: Ashley Rhodes ( [email protected] ).

Received 2019 Oct 18; Revised 2020 Jun 8; Accepted 2020 Jun 23.

This article is distributed by The American Society for Cell Biology under license from the author(s). It is available to the public under an Attribution–Noncommercial–Share Alike 3.0 Unported Creative Commons License.

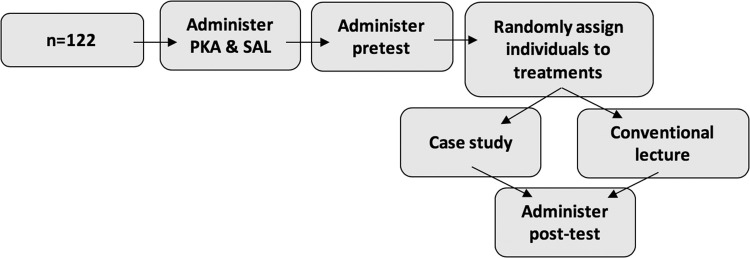

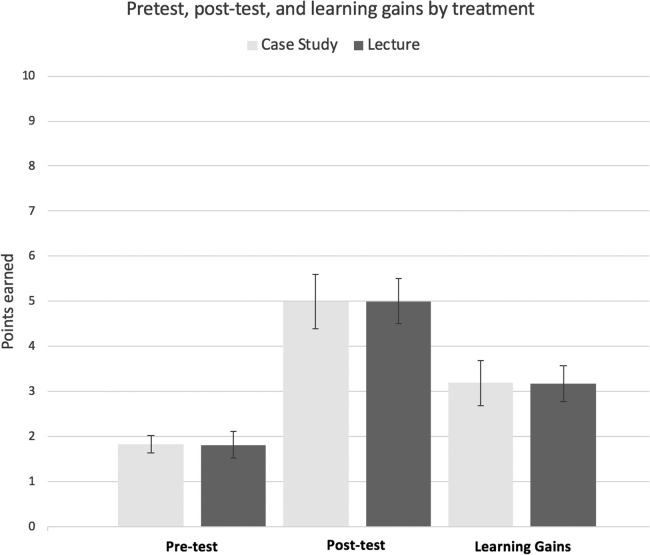

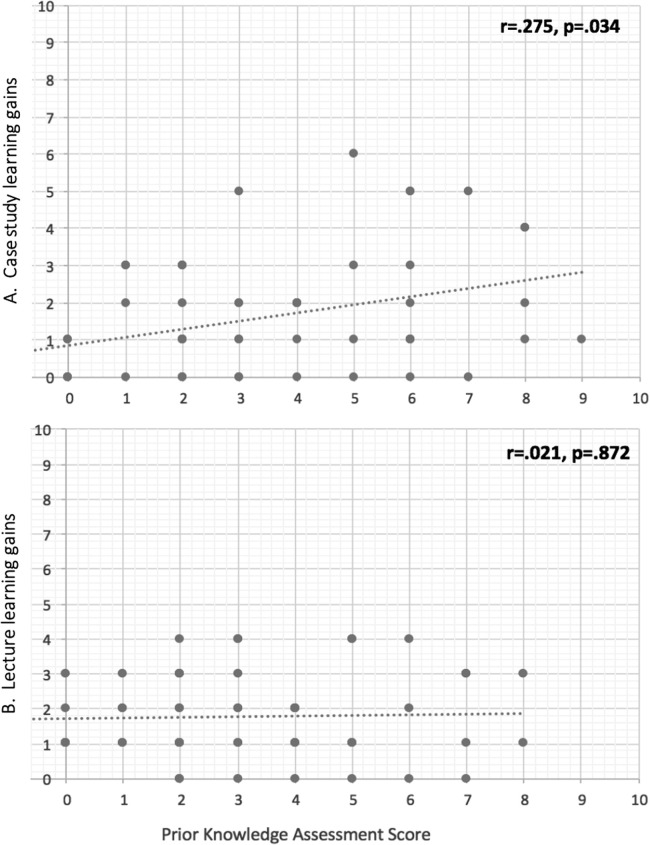

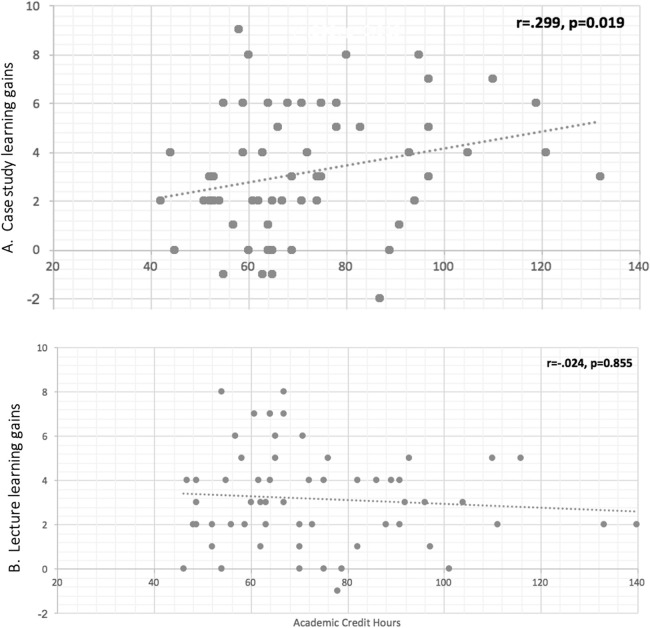

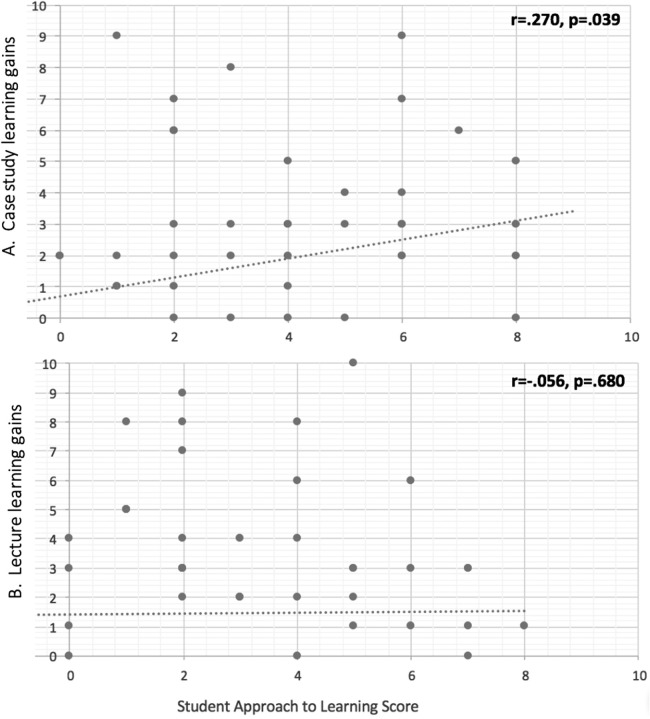

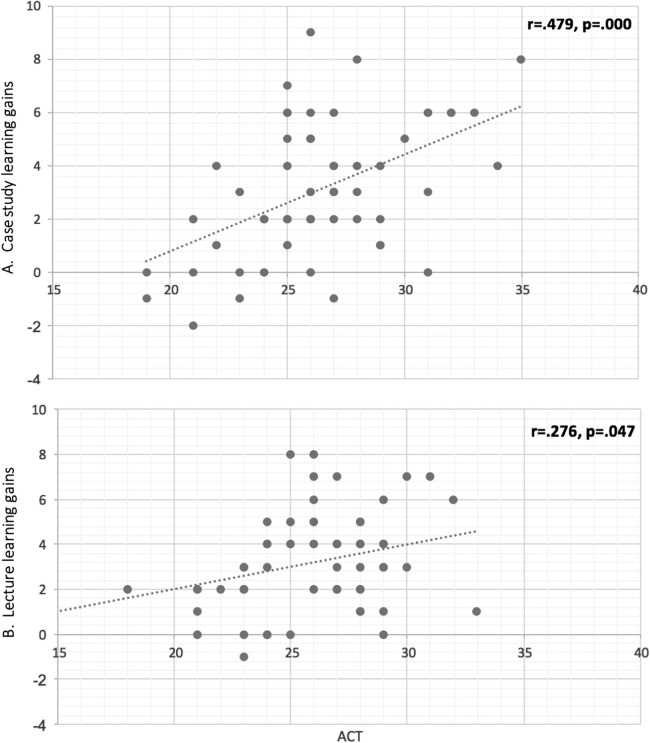

Undergraduate attrition from science, technology, engineering, and mathematics is well documented and generally intensifies during intermediate years of college. Many contributing factors exist; however, a mismatch between timing of certain pedagogical approaches, such as case-based learning, and the level of students’ cognitive abilities plays a crucial role. Using cognitive load theory as a foundation, we examined relationships between case-based learning versus a traditional lecture and learning gains of undergraduates within an intermediate physiology course. We hypothesized instruction via a case study would provide greater learning benefits over a traditional lecture, with gains possibly tempered by student characteristics like academic preparation, as measured by ACT scores, and academic age, as measured by credit hours completed. Results were surprising. Case-based learning did not guarantee improved learning gains compared with a traditional lecture for all equally. Students with lower ACT scores or fewer credit hours completed had lower learning gains with a case study compared with a traditional lecture. As suggested by cognitive load theory, the amount of extraneous load potentially presented by case-based learning might overwhelm the cognitive abilities of inexperienced students.

INTRODUCTION

Increasing the number of students completing a postsecondary degree within the science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields is crucial for building and maintaining a strong workforce, yet loss of students from these fields during their undergraduate years continues to be problematic ( President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, 2012 ; Graham et al. , 2013 ; Freeman et al. , 2014 ; Vilorio, 2014 ; Chen, 2015 ). Attrition from STEM fields may be caused by a number of complex factors that challenge both educators and students alike. For example, attrition has been linked to large classroom sizes; rapid pace of information delivery; a competitive atmosphere; uninspiring pedagogy that is seemingly irrelevant to the lives of students, causing a loss of interest; inability to see presented information as a cohesive whole; or simply feeling that they do not belong in STEM ( Jozefowicz, 1994 ; Herreid et al. , 2012 ; President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology [PCAST], 2012 ; Graham et al. , 2013 ; Freeman et al. , 2014 ; Scott et al. , 2017 ; Fisher et al. , 2019 ). However, it is also possible that a mismatch in the timing of pedagogical tools used and the individual learning needs of students could also cause attrition from STEM fields. For example, Wood (2009) suggested that superior [SIC] students will progress from introductory to upper-level courses during their undergraduate years regardless of the teaching method used. However, students considered to be less academically oriented or self-motivated who leave STEM fields early in their college careers might do so because the curricular methods used are often seen as nothing more than a large collection of disconnected facts that rarely have much relevance to their daily lives and will soon be forgotten ( Wood, 2009 ). Wood (2009) concluded that, for this group of students, the issue lies not in what we teach but in how we teach. This conclusion is both encouraging and yet perhaps a little puzzling for educators, many of whom go to great lengths to help all students within their courses succeed. While some suggestions for helping to alleviate the dissonance between academic preparation and success within STEM courses have been made, they sometimes appear ambiguous or perhaps too complex for educators to tackle. For example, improving student preparation during junior high and high school could translate to better success in college ( Ejiwale, 2013 ). Additionally, improving STEM instructor preparation at multiple levels could be helpful ( Goldhaber and Brewer, 1998 ; Ingersoll and Perda, 2010 ; PCAST, 2012 ). Also, adding more engaging activities within STEM courses could be beneficial for helping underprepared students see connections between in-class learning and real-life applications ( Villanueva and Hand, 2011 ; Kennedy and Odell, 2014 ).

In contrast to some of these more open-ended suggestions, one solution that has been promoted for increasing student success in STEM is the use of active-learning approaches such as case-based learning ( Lundeberg, 2008 ; Kaddoura, 2011 ; McRae, 2012 ; Herreid and Schiller, 2013 ; Greenwald and Quitadamo, 2014 ; Stains et al. , 2018 ). Case-based learning encourages students to use techniques that help them integrate, synthesize, and apply newly learned information to a broader context, both to help them see the value of what they are learning and to foster critical-thinking skills ( Jozefowicz, 1994 ; Graham et al. , 2013 ; Greenwald and Quitadamo, 2014 ).

Case-based learning can take many forms but generally relies upon the use of a case study that describes a specific situation or clinical case and requires students to work through the information to generate solutions and solve problems ( Herreid, 2006 ; Wood, 2009 ; Popil, 2011 ; Savery, 2015 ; McLean, 2016 ). Case studies can vary substantially in length, format, delivery, and the type of media included. Cases may emphasize problem solving, debates, flexible thinking, development of alternative strategies, and even the use of skepticism ( Herreid, 2004 ). Implementing cases within courses can also vary, but according to Herreid (1998) , four major classifications exist in regard to what students do: participate in small-group activities, participate in discussions, listen to a lecture, or work alone completing an individual assignment. Thus, when or how a case study is delivered to students, the responsibilities of students, interactions between students, and even case study assignments that entail students working individually or in groups all vary ( Popil, 2011 ; Thistlethwaite et al. , 2012 ).

Comparing case-based learning to more traditional forms of learning has resulted in reports of increased learning gains ( Kaddoura, 2011 ; Bonney, 2015 ), decreased learning gains ( Andrews et al. , 2011 ; Thistlethwaite et al. , 2012 ), and no significant changes ( Dochy et al. , 2003 ; Halstead and Billings, 2005 ; Hoag et al. , 2005 ; Terry, 2007 ; Kulak and Newton, 2014 ). Some researchers have also reported that case-based learning is effective, but only if supported by supplementary didactic lectures that structured student understanding of the material ( Cliff, 2006 ; Baeten et al. , 2013 ), or that case-based learning improved student attitudes but not always student learning ( Wilke, 2003 ). This disparity could be caused by several factors. For example, it is not currently known how much background knowledge or preparation students should have before they can effectively engage with case-based activities ( McLean, 2016 ), when and how instructors should deliver these activities ( Lundeberg, 2008 ), and how much instructor guidance is required ( McRae, 2012 ).

It is possible that the existing uncertainty regarding who exactly benefits from case-based learning in comparison to other teaching methods could be due to the number of studies primarily relying upon survey data to make conclusions as to the value of this approach ( Cliff and Wright, 1996 ; Knight et al. , 2008 ; McLean, 2016 ; Kaur et al. , 2019 ) and the number of studies that did not use a control and thus lacked a true experimental design ( Greenwald, and Quitadamo, 2014 ; Kulak and Newton, 2014 ). Furthermore, few authors have specifically investigated the utility and potential benefits of case-based learning in regard to certain undergraduate student characteristics or provided clear guidance regarding when and how to use case-based learning within undergraduate courses ( Lundeberg, 2008 ; Kulak and Newton, 2014 ; McLean, 2016 ). Thus, we believe our overarching research question is important when using case-based learning within undergraduate STEM courses: For whom is it useful?

Theoretical Framework

Cognitive load theory (CLT) serves as the foundation for this research, as it provides guidance for investigating relationships between instructional design and student learning gains ( Paas et al. , 2003a ). According to CLT, cognitive processes, and thus learning, are impacted by three types of cognitive loads: extraneous load, intrinsic load, and germane load. These loads are additive and must be appropriately managed for optimal learning, but how they are managed differs based on student characteristics such as previous academic experiences, prior knowledge, and learning preferences. For example, extraneous loads, defined as superfluous information that does not directly relate to learning objectives, should be minimized wherever possible. This is especially true for novice learners, whose ability to take in new information can quickly be overloaded, even when completing common tasks such as searching for and applying information to solve a problem ( Paas et al. , 2003a ). In contrast, intrinsic loads, defined as the degree of difficulty inherent to a discipline, can be more difficult for instructors to manage. Intrinsic load must be supported by appropriately scaffolding information, but should never be minimized, as simplification could give an artificial impression of the discipline and potentially erode the ability to critically think about the information in future contexts ( Paas et al. , 2003a ). However, the degree of scaffolding required is unique for each learner; thus, designing a curriculum or even an individual activity that appropriately manages intrinsic load becomes difficult, especially in large courses with diverse enrollment. According to Paas et al. (2003a ), the key to successfully managing intrinsic load is to consider element interactivity, or the number of interacting items, that must be simultaneously managed to understand a concept. If this number is high, which is often the case within STEM courses, then additional instructional support is often required; for novices, the recommendation is to omit all but the most essential interacting elements. Germane loads, defined as the amount of effort a learner is willing to expend to understand a concept, can be positively impacted by instructional design, but only if the needs of the learner are matched and supported by the way in which information is presented. For example, learners who have little background in a subject, and thus underdeveloped abilities to synthesize and use new information, benefit from instructional tools that present information directly and do not require searching for or synthesis of abstract ideas, while the opposite is true for learners who have prior and positive experiences with the subject ( Paas et al. , 2003a , b ; Sweller et al. , 2011 ; Young et al. , 2014 ).

Conceptual Framework

Using CLT as a theoretical framework, we explored potential relationships between comprehension of complex information that had a high intrinsic load, the experience of learners based upon individual characteristics such as level of academic preparation, and two distinct instructional formats that varied in amount of extrinsic load yet contained the same content. One instructional format included the use of an interactive case study that was designed to engage students with a story and scaffold their nascent understanding of the information presented by chunking information into manageable sections, each one containing explanatory text, interactive graphics, and critical-thinking questions. While carefully designed and aligned with suggestions on case study development, this format did carry a higher extrinsic load due to the number of interacting elements that had to be considered in order to understand the information.

The second instructional format represented a more traditional teaching method and included a didactic lecture using bulleted PowerPoint slides that also included the same graphics presented within the case study; however, the lecture format was devoid of interactive activities and questions and involved only a lecture during which students mostly listened but were allowed to ask questions at any time. This format had a lower extrinsic load due to the decreased number of interacting elements that needed to be considered at any given time to understand the information.

These two instructional formats were used within a large, intermediate-level undergraduate physiology course with a diverse student body that varied in age and academic preparation. However, all were majoring in a STEM discipline, and many aspired to matriculate into a professional school upon graduation. Thus, while variation did exist within the population, we believe it is an accurate portrayal of the natural variation found within most large STEM courses at this level.

To examine the utility of case-based learning and the benefits it may provide in regard to specific student characteristics in comparison to a more conventional format of learning, we investigated the following two research questions:

Compared with a conventional learning format such as a traditional lecture, how do student learning gains differ when using a case study?

How do student characteristics such as general academic preparation and credit hours completed relate to learning gains derived from the use a case study?

Setting and Participants

This study took place at a large, midwestern, land-grant university with an admissions acceptance rate of 94%. Participants were recruited from an intermediate (300 level at a university in which undergraduate courses start at 100 and go through 600) physiology course offered within a biology department. During the semester in which the study was conducted, the course was open to all students who had completed introductory biology and chemistry courses and received a “B” or better in both. Furthermore, this course was an 8 credit-hour course that included several components such as lecture, laboratory, and cadaver dissection; thus, most students were very committed to learning, as their grades would have had a significant impact on their overall grade point averages. Applications of course material on exams and quizzes tended to be focused on human health and applications to allied health professions. The average ACT score of students was 26.6. Of the 134 students enrolled, all chose to participate, although only 122 completed all portions of the study due to absences. The final distribution of students completing all components of the study represented a mixture of 34 sophomores, 59 juniors, and 29 seniors. Information related to gender and ethnicity was not tracked.

Participation in the study was voluntary, and all activities were approved by our Institutional Review Board (IRB protocol no. 7028). Students were awarded a small amount of extra credit for participating. Students were provided the option of an alternative assignment if they did not want to participate; however, none selected this option.

Development of Case Study and Conventional Lecture Treatments

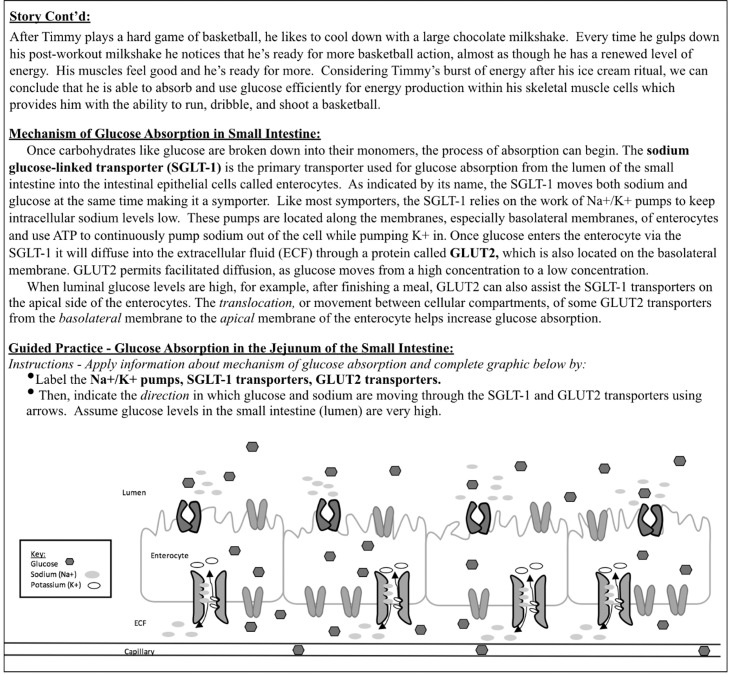

Both the case study and conventional lecture were created by the authors to specifically deliver information about insulin resistance and its progression to type II diabetes. Not only do these topics encompass suggestions by Michael et al. (2017) about pertinent concepts that should be taught within undergraduate physiology courses, such as flow-down gradients between blood and interstitial fluid and details of cell membranes, but they also align well with suggestions made by Allen et al. (1996) regarding topic selection for the design of critical-thinking activities. The case study was created using a design-based research process that entailed four iterations. Each iteration was reviewed by graduate teaching assistants as well as three STEM instructors. After each iteration, feedback was used to revise and improve the case study. The final iteration of the case study authored by Wilson et al. (2017) was peer reviewed and published by the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science.

The case study included a short story about an individual who, through diet and lack of exercise, proceeded through the stages of insulin resistance and pre-diabetes and eventually developed type II diabetes. Immediately following each section about this individual’s story, accompanying informational text as well as interactive figures and graphics describing the physiology of what was occurring were presented. The story, text, and graphics were presented in small sections, a strategy known as chunking, which is encouraged when presenting complex information that has multiple interacting elements ( Mayer and Moreno, 2003 ). The interactive figures and graphics, which displayed the same information presented within the text, required students to apply what they had just read to complete them as described by carefully written instructions. And finally, critical-thinking questions were placed at the end of each section or chunk, and students were asked to think about what they had just learned before moving to the next section. Figure 1 provides a sample of the case study design features.

Typical features of the case study design. This particular portion was taken midway through the case study after students had been presented with information about the basics of carbohydrate breakdown in the digestive system. Specific features related to chunking and scaffolding include a short story, a small amount of explanatory text, and instructions explaining how to interact with a graphical feature designed to help students visualize the information. Additionally, the explanatory text and visuals were placed very close to each other, and vocabulary used in the explanatory text matched vocabulary used in the visual in order to reduce cognitive load.

Students in the lecture treatment, which consisted of a traditional lecture with PowerPoint slides and accompanying handouts of the slides, received the same physiological information presented in the case study. For example, the lecture and handouts included static versions of the figures and graphics found in the case study, and these were described directly to students by the instructor. This presentation was also subjected to four iterations of review and improvement by graduate students and other STEM instructors. Thus, the major differences between the case study and conventional lecture treatment groups were that students in the latter group were not presented with a story or required to complete activities associated with the graphics. In short, the conventional lecture contained little to no extraneous information.

Implementation of Treatments

Both treatments were administered during regularly scheduled lab periods within a single week of the semester and before any presentation of glucose homeostasis by the primary instructor in either lecture or lab. At the beginning of each treatment, the same instructor provided a brief overview of the activities and goals. For the case study group, this also included instructions on how to work through the case and specifically how to interact with the graphics. This instructor was the lead author of the case study and conventional lecture treatment and was also a lab instructor for the course; thus, comfort level with techniques, delivery, students, and content was high.

Students in both treatments were instructed to work alone, as one of our main objectives was to correlate student characteristics such as academic preparation and experience with learning gains when extrinsic load was varied between treatments. Thus, we purposefully did not allow students to work in groups, as this would have made our data difficult to interpret in regard to individual student gains. However, students in both treatments were told several times they could ask the instructor questions at any time while working through the case study or listening to the lecture.

Experimental Design