11 Meaningful Texts about Native American History and Heritage

Allie Liotta

Check out this diverse collection of texts for grades 3–12 about Indigenous cultures and experiences across the United States.

Studying Native American history and heritage in the classroom is a great way to teach students about the traditions and cultures of Indigenous peoples across the United States. Reading a variety of texts about Native experiences helps expose students to different perspectives and opens doors to other cultures.

This diverse collection of texts for grades 3–12 includes short stories by Native American authors, primary sources, informational texts, and more.

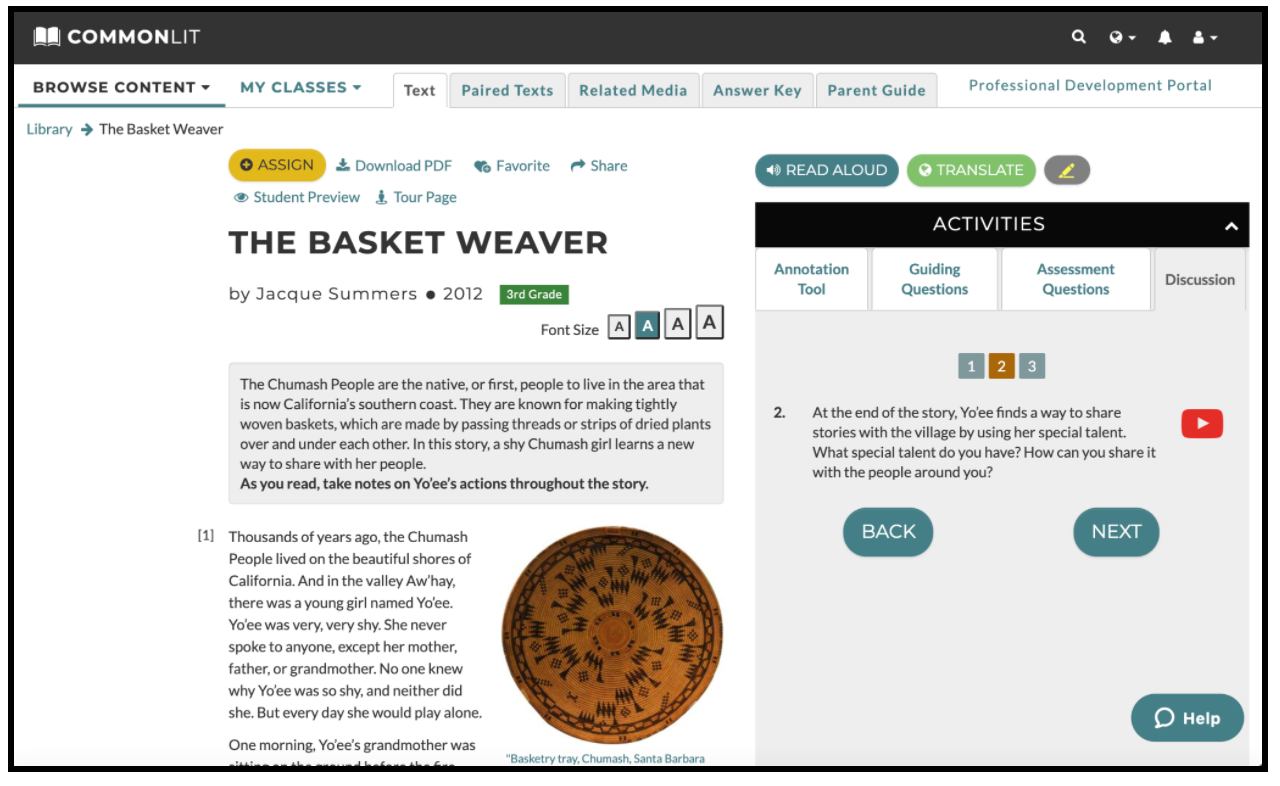

“ The Basket Weaver ” by Jacque Summers (3rd Grade)

In this short story, a shy Chumash girl named Yo’ee learns a new way to share her voice with her community. The Chumash people, from what is now California’s southern coast, are known for making tightly woven baskets. In the story, Yo’ee learns to tell stories through her intricate weaving. Reading this text is a great way to start a conversation about the value of different talents.

“ Fun and Games ” by Kelsie Ingham (4th Grade)

In this informational text, Kelsie Ingham discusses the different games that Native American children played in the past. Sports like shinny and tug-of-war taught important life skills, like hunting and teamwork. Many popular games today come from traditional Native American sports. Elementary students will love learning about Native American children’s games and can compare and contrast them to the games they play at recess or at the park.

“ Heartbeat of Mother Earth ” by CR Willing McManis (5th Grade)

In this informational text, CR Willing McManis describes the origins of pow wows and what takes place during modern ceremonies. Today, pow wows can be small or large, but all include drumming, dancing, crafts, and food. Students will enjoy learning about the details of these celebrations and can discuss how the ceremonies strengthen Native American communities.

“ I Am Offering This Poem ” by Jimmy Santiago Baca (6th Grade)

In this poem by Jimmy Santiago Baca, an award-winning writer of Apache and Chicano descent, the speaker offers his words to the reader as a token of his love. The warm imagery in this poem draws on Baca’s cultural heritage. This text can be used to start a meaningful conversation with students about the ways love changes people.

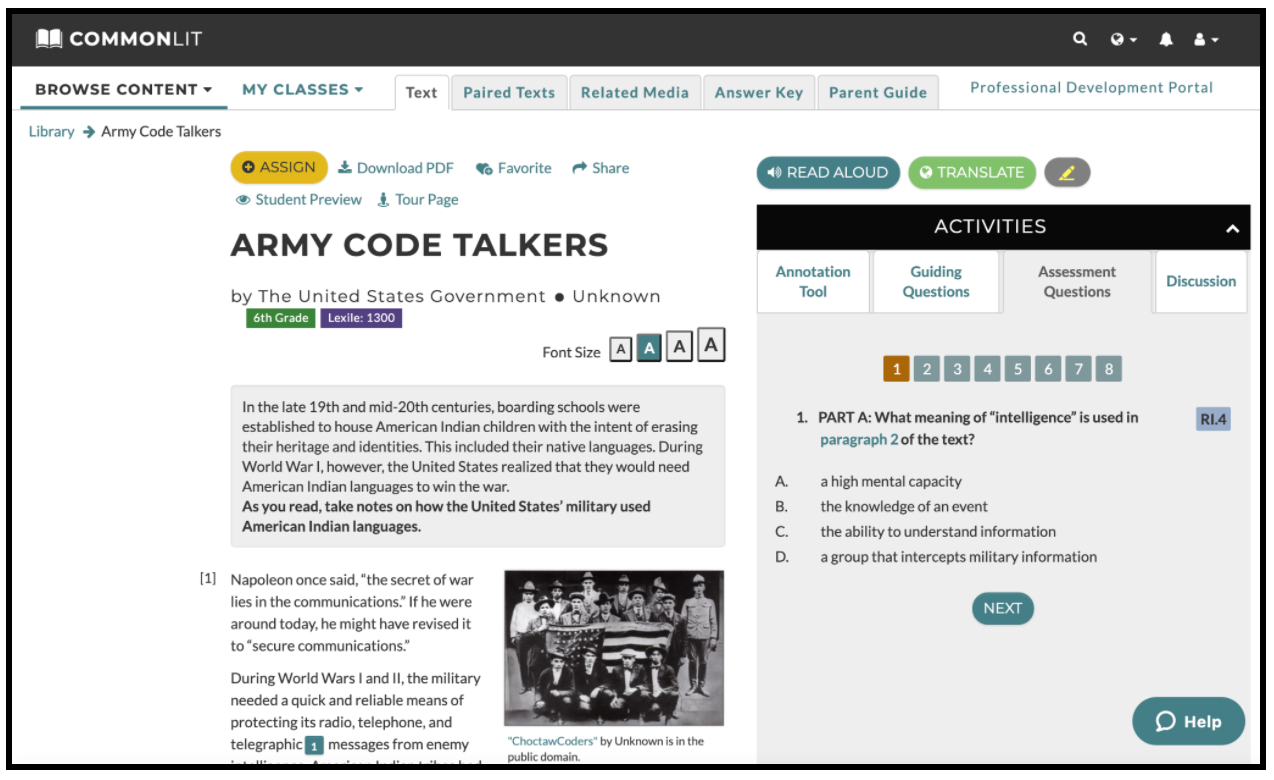

“ Army Code Talkers ” by the United States Government (6th Grade)

In this article, the author discusses the contributions of Native American “code talkers” during World War I and World War II. The United States military used American Indian languages to transmit secure messages related to troop movements and tactical plans. This text provides students with an interesting opportunity to discuss Native American contributions during wartime and the government’s treatment of Native Americans at different points in history.

“ The Medicine Bag ” by Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve (7th Grade)

In this short story by Sioux author Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve, Martin’s dying grandpa visits with the intention of passing down a traditional medicine bag. Martin is embarrassed by his grandpa’s appearance and the dirty medicine bag. By the end of the story, he comes to understand the importance of the history and culture they share. Middle school students will relate to Martin’s desire for belonging and how it leads to complicated feelings about his family.

“ Chief Powhatan’s Address to Captain John Smith ” by Chief Powhatan (8th Grade)

In this speech, Chief Powhatan of the Powhatan tribe addresses Captain John Smith, a leader of Jamestown, Virginia. Chief Powhatan seeks to curb the violence and promote peace between the English settlers and his tribe. This primary source provides a powerful opportunity for students to analyze the relationships between Indigenous peoples and colonists in the 1600s.

“ How Native Students Can Succeed in College: ‘Be As Tough As The Land That Made You’ ” by Claudio Sanchez (8th Grade)

In this informational text, Claudio Sanchez examines the challenges that Native American teenagers face when seeking higher education and how a program called College Horizons helps prepare them to overcome obstacles. College Horizons holds retreats to help Native American students connect to their cultures and get ready for college life. Middle school students will relate to the Native students’ exploration of their identities and desire for belonging.

“ American Indian School a Far Cry from the Past ” by Charla Bear (9th Grade)

In this informational text, Charla Bear discusses an off-reservation boarding school, Sherman Indian High School, and the various opinions people have about it. Some students feel confined within Sherman’s rigorous structure, while others value the chance to learn about other Indigenous cultures and escape the challenges that face their families on reservations. This text provides an interesting opportunity for students to examine the modern ramifications of Native American removal and assimilation.

“ Red Cloud’s Speech after Wounded Knee ” by Chief Red Cloud (10th Grade)

In this speech, given after the Wounded Knee Massacre, Chief Red Cloud of the Oglala Lakota tribe sheds light on the plight of Native American peoples living on reservations. Red Cloud was a lifelong proponent of peace. In this speech, he argues that those who were killed at Wounded Knee were not violent, but rather wanted to communicate their suffering and get help. This text would be a great primary source to integrate into a history lesson or a unit on persuasive speeches.

“ UN Explores Native American Rights in U.S. ” by Michel Martin (11th Grade)

In this text, Michel Martin interviews S. James Anaya about the report he wrote for the United Nations regarding the rights of Native Americans. Anaya’s Apache and Purepecha ancestry inspired him to dedicate his law career to the issues facing Indigenous peoples. In the interview, Anaya suggests ways the government can better support Native communities. Students will be moved by Anaya’s dedication to uplifting Indigenous peoples in the United States.

To read more engaging texts about Native American history and heritage, you can explore our Native American History and Authors text set !

If you’re interested in learning all about CommonLit’s free digital literacy program, join one of our upcoming webinars !

Chat with CommonLit

CommonLit’s team will reach out with more information on our school and district partnerships.

NORTHERN PLAINS HISTORY AND CULTURES

How do native people and nations experience belonging.

lesson information

Apsáalooke (Crow), Arikara, Dakota (Sioux), Hidatsa, Lakota (Sioux), Mandan, Nakota (Sioux), Northern Cheyenne

Geography, Government and Civics, History, Social Studies

Great Plains, northern plains, plains, Plains Indians, Crow, Cheyenne, Northern Cheyenne, Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold, Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara, Lakota, Dakota, Nakota, Oceti Sakowin, homelands, kinship systems, kinship, Native Nation, tribal nation, tribal governments, cultures, culture, history, relationships, extended family, community, rights, responsibilities, values, traditions, beliefs, elders, sovereignty

Plains, North America

essential understandings

There is no single American Indian culture or language.

For millennia, American Indians have shaped and been shaped by their culture and environment. Elders in each generation teach the next generation their values, traditions, and beliefs through their own tribal languages, social practices, arts, music, ceremonies, and customs.

Kinship and extended family relationships have always been and continue to be essential in the shaping of American Indian cultures.

The story of American Indians in the Western Hemisphere is intricately intertwined with places and environments. Native knowledge systems resulted from long-term occupation of tribal homelands, and observation and interaction with places. American Indians understood and valued the relationship between local environments and cultural traditions, and recognized that human beings are part of the environment.

American Indian institutions, societies, and organizations defined people's relationships and roles, and managed responsibilities in every aspect of life.

Native kinship systems were influential in shaping people's roles and interactions among other individuals, groups, and institutions.

Today, American Indian governments uphold tribal sovereignty and promote tribal culture and well-being.

Today, tribal governments operate under self-chosen traditional or constitution based governmental structures. Based on treaties, laws, and court decisions, they operate as sovereign nations within the United States, enacting and enforcing laws and managing judicial systems, social well-being, natural resources, and economic, educational, and other programs for their members. Tribal governments are also responsible for the interactions with American federal, state, and municipal governments.

Long before European colonization, American Indians had developed a variety of complex systems of government that embodied important principles of effective rule. American Indian governments and leaders interacted, recognized each other's sovereignty, practiced diplomacy, built strategic alliances, waged wars and negotiated peace accords.

academic standards

HEAR FROM THE EXPERT:

Julie Cajune Educator from the Salish Nation

Northern Plains Nations: Belonging to Place, Family, and Nation

One third of the United States is classified as the Great Plains. Although that term usually evokes an image of an expansive area of flat land, in fact, the Great Plains are much more varied than that. Among the large regions of tall grasslands are numerous forested mountain ranges, such as the Black Hills and the Bear Paw Mountains. The Great Plains landscape also includes rolling hills that slope to river corridors lined with groves of cottonwood and box elder trees. This enormous expanse of land was once home to immense herds of bison that were essential to the lives and economies of Native peoples. Sadly, bison were nearly eliminated during the era of westward movement that was fueled by the idea of Manifest Destiny.

Many Native Nations still call the Great Plains home. Some of these nations have inhabited the plains since time immemorial. Others established their homelands on the plains more recently, as their tribal territories shifted over time. This module focuses on the Oceti Sakowin (Sioux Nation), Northern Cheyenne, Crow, Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Native nations, each of which continues to call the northern portion of the Great Plains their home. These sovereign nations live in the Great Plains among the stories and collective memories of their ancestors and relatives.

The histories of plains Native Nations extend far beyond the reservation borders of today. Sacred and important sites, of which many are ancient, speak to a relationship that these Native peoples have with the land. After living within these sacred landscapes for many generations, they have developed a deep sense of belonging to place.

Underscoring the importance of place is the knowledge that plains Native people have of their role within their family and community. Native kinship systems provide a network of care and support that extends beyond the immediate family. This network of relationships and relatives guarantees that each member of the community has an extended family in which one's belonging is continually reinforced.

Native people also belong to their tribal Nations as citizens, and that citizenship carries with it certain rights and responsibilities. Each nation's customs, values, and traditions inform an individual's role as a tribal citizen.

Over the centuries, many things have changed on the Great Plains. However, Native culture is persistent and strong; we invite you to explore this module and to learn how Native identity continues to be shaped by relationships with land, family, and nation.

What Gives Native Nations a Sense of Belonging to the Land?

How do kinship systems work to create a feeling of belonging, what are the rights and responsibilities of belonging to a native nation, connecting to native histories, cultures, and traditions: the intertribal buffalo council.

- Related Resources

The National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) expresses gratitude to the people of the American Indian Nations whose histories, cultures, and contemporary lives are represented on these pages.

The NMAI extends special thanks to members of the Northern Plains—region team whose thoughtful collaboration and extraordinary expertise made these inquiry-based lessons possible.

The museum also thanks the following staff and other contributors for their work in the creation of these lessons:

Museum Director: Kevin Gover (Pawnee)

Producer and Writer: Edwin Schupman (Muscogee)

Content Manager, Developer, and Lead Writer: Colleen Call Smith

Developer and Lead Writer: MaryBeth Yerdon

Northern Plains–Region Team:

Julie Cajune (Salish), Lead Writer

Tammy Elser, Ed.D., Educator

George Price, Ph.D. (Assonet Wampanoag, Massachuset, and Choctaw), Scholar

Edward Charles Valandra, Ph.D. (Sicangu Lakota), Scholar, Cultural Expert

Additional Writer/Lesson Developer

Daniel Fischer, NMAI

Paraphrasing

Martha Davidson

Researchers

Erin Beasley, NMAI

Jessica Phippen, NMAI

Sue Davis, NMAI

Mark Hirsch, Ph.D., NMAI

Joe Horse Capture (A'aninin), NMAI

Carrie Loretto (Zuni, Acoma, San Felipe Pueblo), NMAI Teacher-In-Residence, New Mexico

Stacey Mann

Michelle Nelin-Maruani, NMAI Teacher-In-Residence, South Dakota

Vilma Ortiz-Sanchez, NMAI

Christopher Robinson, NMAI Teacher-In-Residence, Kentucky

Kathy Swan, Ph.D., University of Kentucky and C3Teachers.org

Community Interviews:

Rylee Arlee (Bitterroot Salish)

Grant Bulltail (Crow Tribe of Montana)

Elizabeth Cook-Lynn (Crow Creek Sioux)

Shaniya Decker (Salish/Turtle Mountain/Assiniboine)

Calvin Grinnell (Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold)

Marilyn Hudson (Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold)

Jacob Hugs (Salish)

Arrianna Henry (Salish/Kootenai)

Joshua Hugs (Salish/Crow)

Joey Kipp (Salish/Muscogee)

Peter Matt (Salish/Lakota/Dakota Sioux)

Jon Matt (Salish)

Wacey McClure (Salish/Dakota Sioux)

Robert Miller, Ph.D. (Eastern Shawnee Tribe of Oklahoma)

Darrin Old Coyote (Crow Tribe of Montana)

Anthony Prairie Bear (Northern Cheyenne)

Mildred Red Cherries (Northern Cheyenne)

Gail Small (Northern Cheyenne)

Mark Wandering Medicine (Northern Cheyenne)

Charmaine White Face (Oglala Lakota)

Frankie Wright (Confederated Salish/Kootenai)

Loren Yellow Bird Sr. (Arikara/Hidatsa)

Aerial footage by Foresight Aerial Photography

Mark Christal, NMAI

Dan Davis, NMAI

Doug McMains, NMAI

David Chang

Rebecca Estes, NMAI

Laurie Swindull, NMAI

Jason Wigfield

Cheryl Wilson, NMAI

Deanna Wood, NMAI

Interactivity Concepts and Design

Interactive Mechanics

Christine Gordon

Anne Litchfield

Rights and Permissions

Wendy Hurlock-Baker, NMAI

Colleen Call Smith, NMAI

MaryBeth Yerdon, NMAI

Jerrell Cassady, Ph.D., Research Design Studio at Ball State University

Teacher Testing

Anna Baldwin, Arlee High School, Arlee, MT

Julie Bell, Washington-Lee High School, Arlington, VA

Tim Biggs, St. Ignatius High School, St. Ignatius, MT

Dianna Bisbee, AIM Bryant Program, Alexandria, VA

Daniel Gagliano, Cesar Chavez Public Charter School, Washington, DC

Sean Gholso, Douglas High School, Rapid City, SD

Lierdre Galloway, River Hill High School, Clarksville, MD

David Herrick, Stevens High School, Rapid City, SD

Bo Ingalsbe, Falls Church High School, Falls Church, VA

Angela Johnson, River Hill High School, Clarksville, MD

Mellissa Kelly, Glasgow Middle School, Lincolnia, VA

Beth Monarch, Stonewall Jackson High School, Manassas, VA

Christina Mullen, The Nora School, Silver Spring, MD

Casey Olson, Columbus High School, Columbus, MT

Bridgett Paddock, Skyview High School, Billings, MT

Wendy Tyree, Skyview High School, Billings, MT

Carmen Wright, Prince George Community College, Academy of Health Sciences, Largo, MD

Voice Talent

Studio Center, Virginia Beach, VA

Edwin Schupman (Muscogee), NMAI

Mandy Van Heuvelen (Lakota), NMAI

Contract Management

Pam Woodis (Jicarilla Apache), NMAI

Special thanks to:

Bernard Quetchenbach: For the generous gift of photographs to support these lessons.

Desi Rodriquez-Lonebear (Northern Cheyenne): For the generous gift of family photographs to support these lessons.

Gail Small (Northern Cheyenne): For generous support in coordinating interviews with community members of the Northern Cheyenne Nation.

Sharon Small: For the generous gift of family photographs to support these lessons.

Dick Walton: For the generous gift of photographs to support these lessons.

Tim Bernards, Little Big Horn Tribal College

Reno Charette (Crow)

Shane Doyle (Crow)

Silas Hagarty

Alberta Iron Cloud (Oglala Sioux)

Tim McCleary, Little Big Horn Tribal College

George Reed Jr. (Crow), Crow Culture Committee

Matt Remle (Hunkpapa Lakota)

Ruth Ann Swaney (Three Affiliated Tribes of Fort Berthold)

Lisa Whitecloud (Dakota)

Joe Whittle (Caddo and Delaware)

Graphic Illustrations

Weshoyot Alvitre

The National Museum of the American Indian gratefully acknowledges the generous support of the Margaret A. Cargill Foundation in the development of these educational resources.

- Northern Plains History and Cultures Introduction

- Native Nations Belonging to the Land

- Kinship Creates a Feeling of Belonging

- Rights and Responsibilities Belonging to Native Nation

- How do Native People and Nations Experience Belonging?

- InterTribal Buffalo Council

How Native Americans shape the American experience

November’s designated as native american heritage month. but anthropology associate professor brian mckenna reminds his students in campus’ indians of north america course that we benefit from the knowledge of this country’s indigenous people all year long..

This article was originally published on November 12, 2019.

Standing in front of a full classroom, Anthropology Associate Professor Brian McKenna speaks about Native American contributions to community structure, medicine, government systems, agriculture and environment. Students seem a bit surprised.

McKenna continues: And the names of more than half of our states.

“States, cities, communities. So many of our places have native origins,” he says. “I think destroying who or what was on the land and then naming the spot after what was once there is the American way. Think of apartments with names like Deer Park Run. No one sees deer there because the construction pushed them away or destroyed their food sources. But it does sound really nice.”

McKenna talks honestly, with a bit of dark humor. And his class appreciates him for it. Their hands are constantly raised with questions and contributions to the discussion. And he gets students to relate to the material he includes in his lectures.

Since we all can’t sit in his classroom — there are only about 40 desks, after all — here are some of McKenna’s course take-a-ways.

When it comes to the environment, Native Americans can teach us.

“Most of us are concerned about climate change and what’s left of our resources. But Native Americans are way ahead of us on this. The Native Americans lived here 20,000 years without messing it up. The Iroquois have the seventh generation principle, which dictates that decisions that are made today should lead to protecting the land for seven generations into the future. And American Indians are the ones we see fighting to preserve what is left; look at the Dakota Access pipeline protests and the Enbridge pipeline actions Up North. If we really want to stop or reverse the damage that’s been done, they have examples we can follow.”

Sixty percent of our consumed foods have Indian origins.

“Like fries? I’m Irish, but my history can’t take credit for the potato. That’s the Peruvian Indians and the Incas. How about chocolate? That’s the Mayans. Fall foods like squash and beans? The Native Americans have a long tradition with those foods and the New England colonists learned from them. And if you have a drink on your desk, remember that there wouldn’t be a soda industry without the coca leaves from the Indians of Bolivia. Corn? You already know. Unfortunately, that one’s led to the capitalistic creation of corn syrup. But that’s what I call the Indian’s revenge.”

Much of our prescription knowledge comes from Native American medicine.

Look in your medicine cabinet. If you have aspirin in there to help with a headache, know it comes from the willow bark of the poplar tree. Don’t thank Bayer; thank an Indian. They had 20,000 years to get to know their land and have so much knowledge of botanical medicinal properties. The early American explorers were known to write it down and take it back to Europe with them. Dogwood reduces fever. Trillium eases the pain of childbirth. A small amount of Curare — not too much, it’s poisonous — stops lockjaw cramping. UM-Dearborn Emeritus Professor Daniel Moerman published a Native American Ethnobotany Book and put it online . Type in a symptom and you can find what Natives Americans — thousands of years ago and today — use for relief. It’s a reminder that we are walking over and past medicine all of the time.

If you like the idea behind our Constitution, thank the Iroquois.

“There are leaders who helped form our government who aren’t traditionally mentioned in World History. When the original 13 colonies were busy fighting each other, Onondaga leader Canassatego encouraged them to unite and shared the Iroquois Great Law of Peace as an example on how to do this. Benjamin Franklin printed Canassatego’s words and invited the Iroquois Grand Council of Chiefs to speak to the Continental Congress in 1776. It’s where we got our checks and balances, two branches for passing laws, the impeachment process and more. Our government is descended from theirs — Congress officially recognizes this now. It’s too bad we didn’t include their seventh generation principle.”

After class ends and students have filtered out of the room , McKenna — an environmental journalist and medical anthropologist — explains how an Irish man from Philadelphia became so involved with Native American culture. He says it began with a chance meeting with a member of the American Indian Movement (AIM) as a teen in the mid-1970s while traveling across America.

“Basically, I was dropped into history.”

While staying with a newly made friend in South Dakota, McKenna met a Native American from the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. The man — McKenna pauses and thinks about giving a pseudonym, then decides anonymity is best — was a body double for a leader of AIM. McKenna recalled how much he admired the man’s bravery in standing up against police brutality and systemic poverty in extreme circumstances. He relayed how this experience sparked his curiosity about the history and culture of American Indians.

“The courage I saw really was life changing. After getting to know some members of the Pine Ridge reservation, I was shocked at the level of ignorance about the American Indian Movement during that time. I wanted to do what I could to dispel myths and bring awareness,” says McKenna, who’s spent time during his career working with American Indian Health and Family Services in Detroit and at National Public Radio’s Fresh Air with Terry Gross .

Years later, McKenna is surrounded by engaged students who, just like he was, are curious about Native American history and want to build community with native peoples. McKenna’s taught the course — created by Emeritus Professor Daniel Moerman in 1974 — for 15 years.

Not only does McKenna teach, he encourages the students to interact with tribal communities — noted alumna Kay McGowan, a writer of the United Nations’ Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, is a frequent guest speaker; students also do a project where they are encouraged to get to know Native culture first-hand.

“For the class project, students have the opportunity to reach out to a first nation. “I’ve recently had a student document the repatriation of ancestral remains from U-M. He went to the Saginaw Chippewa’s Recommitment to the Earth ceremony in Mount Pleasant. Other students have attended powwows or visited a Native American museum. I want our students to learn from native people directly,” McKenna says.

“And I update my course every time I teach it. For example, I’m using David Treuer’s 2019 “The Heart of Wounded Knee” right now. Treuer graduated from U-M with an anthropology degree. I want to make sure I’m relating to my students of today about issues the Native Americans are facing today. People evolve so my course can’t stay stagnant.”

But there is something that remains the same: Native American influence on shaping American culture.

So, in honor of the month — and Governor Whitmer’s recent decision to replace Columbus Day with Indigenous Peoples’ Day — McKenna wants to create awareness of cultural appropriation and have us appreciate American Indian contributions that enhance our lives all year round.

Related News

Helping underrepresented kids see themselves through stories

Plan a trip to the lake

‘Education is the equalizer’

Current news.

"An experience that I'll never forget'

How to reel in phish

ENCYCLOPEDIC ENTRY

Native americans in colonial america.

Native Americans resisted the efforts of the Europeans to gain more land and control during the colonial period, but they struggled to do so against a sea of problems, including new diseases, the slave trade, and an ever-growing European population.

Geography, Human Geography, Social Studies, U.S. History

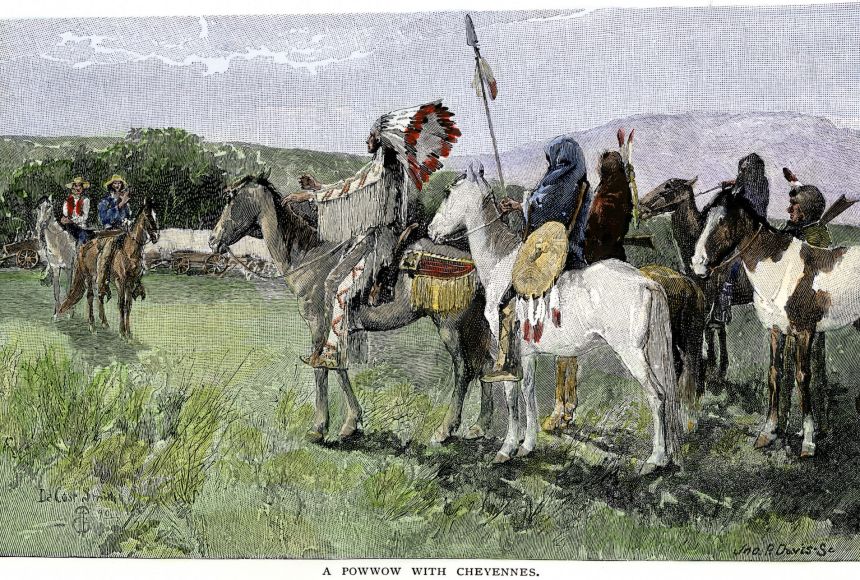

Diplomacy between Cheyenne and Settlers

Whether through diplomacy, war, or even alliances, Native American efforts to resist European encroachment further into their lands were often unsuccessful in the colonial era.

Photograph of woodcut by North Wind Picture Archives

During the colonial period, Native Americans had a complicated relationship with European settlers. They resisted the efforts of the Europeans to gain more of their land and control through both warfare and diplomacy . But problems arose for the Native Americans, which held them back from their goal, including new diseases, the slave trade , and the ever-growing European population in North America. In the 17th century, as European nations scrambled to claim the already occupied land in the “New World,” some leaders formed alliances with Native American nations to fight foreign powers. Some famous alliances were formed during the French and Indian War of 1754–1763. The English allied with the Iroquois Confederacy, while the Algonquian-speaking tribes joined forces with the French and the Spanish. The English won the war, and claimed all of the land east of the Mississippi River. The English-allied Native Americans were given part of that land, which they hoped would end European expansion —but unfortunately only delayed it. Europeans continued to enter the country following the French and Indian War, and they continued their aggression against Native Americans. Another consequence of allying with Europeans was that Native Americans were often fighting neighboring tribes. This caused rifts that kept some Native American tribes from working together to stop European takeover. Native Americans were also vulnerable during the colonial era because they had never been exposed to European diseases, like smallpox , so they didn’t have any immunity to the disease, as some Europeans did. European settlers brought these new diseases with them when they settled, and the illnesses decimated the Native Americans—by some estimates killing as much as 90 percent of their population. Though many epidemics happened prior to the colonial era in the 1500s, several large epidemics occurred in the 17th and 18th centuries among various Native American populations. With the population sick and decreasing, it became more and more difficult to mount an opposition to European expansion. Another aspect of the colonial era that made the Native Americans vulnerable was the slave trade. As a result of the wars between the European nations, Native Americans allied with the losing side were often indentured or enslaved. There were even Native Americans shipped out of colonies like South Carolina into slavery in other places, like Canada. These problems that arose for the Native Americans would only get worse in the 19th century, leading to greater confinement and the extermination of Native people. Unfortunately, the colonial era was neither the start nor the end of the long, dark history of treatment of Native Americans in the United States.

Media Credits

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Production Managers

Program specialists, last updated.

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

Smithsonian Voices

From the Smithsonian Museums

SMITHSONIAN EDUCATION

Transforming Teaching and Learning About Native Americans

An ongoing goal of the National Museum of the American Indian is to change the narrative of Native Americans in U.S.’s schools.

Maria Marable-Bunch

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/blogging/featured/NMAI1.png)

Remember those oversized and heavy history textbooks we labored to carry and studied as middle and high school students? Do you recall whose stories or histories were or were not included in these books? We learned about the founding fathers and a skewed sampling of great American heroes, but did we study the historical stories or perspectives of women, African Americans, Native Americans, and many other oppressed Americans? Those oversized textbooks often failed to include a more complete American story. They didn’t provide us with the critical knowledge and perspective we needed to better understand our country’s history and gain an understanding and appreciation of our differences. Today, textbooks are still written with the missing voices or perspectives of many Americans, especially Native Americans.

In 2012, the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) conducted a content analysis of American Indian subject matter featured in U.S. textbooks. This study found little evidence that these textbooks included any substantial information about important Native American history, culture, and contemporary life. There certainly was no integration of Native perspectives into the larger narrative of American history. Resources for classroom teachers were often incorrect, incomplete, or denigrating to Native children about their histories. It was clear that a majority of K–12 students and teachers lacked knowledge, understanding, and access to authentic resources about Native Americans. Based on this study, the museum committed to creating an online resource that would address these deficiencies. Native Knowledge 360 ° ( NK360 °) was created out of a desire to provide accurate resources on Native American history and culture to K–12 educators. NK360 ° would provide lesson plans, student activities, videos, and documents to tell a more comprehensive story and to challenge common assumptions about Native peoples. The museum’s ultimate goal for NK360 ° was to transform teaching and learning about Native peoples.

To produce this unique educational resource, staff collaborated with the National Council for the Social Studies (NCSS) to develop a framework called Native Knowledge 360° Essential Understandings . This framework built on the ten themes of NCSS national curriculum standards: culture; time, continuity, and change; people, places, and environments; individual development and identity; individuals, groups, and institutions; power, authority, and governance; productions, distribution, and consumption; science, technology, and society; global connections; and civic ideals and practices. The NK360° Essential Understandings framework, developed in collaboration with Native communities, national and state education agencies, and educators, adapted these key concepts to reflect the rich and diverse cultures, histories, and contemporary lives of Native Peoples. The Understandings reflect a multitude of untold stories about American Indians that can deepen and expand the teaching of history, geography, civics, economics, science, engineering. In 2018, the museum launched the NK360° national education initiative.

A number of factors influence our decisions about which topics we select. Foremost, we listen to teachers in conversations and though evaluation processes to determine what they need and will use. We also analyze learning standards and curricula to find out the topics that schools are required to teach . The initial teaching modules designed for grades 4–12 highlight histories of the Northern Plains Treaties , Pacific Northwest History and Culture , Pacific Northwest Fish Wars , and Inka Road Innovations . The museum recently released American Indian Removal and The “Sale” of Manhattan , each created in collaboration with tribal communities. Several lessons are also available in Native languages and Spanish . The format ranges from simple lesson plans to modules that are taught over several class sessions. Included are teacher instructions, student activities, document images, and videos of Native people sharing their stories. Teachers, accessing this information, hear the voices of contemporary Native Americans talking about their community and the importance of their history.

To introduce educators to these resources, the museum hosts teacher professional development programs that reach across the country and globally, modeling the content and pedagogical approach. The museum hosted a free webinar series for educators on July 21–23, 2020. The three-part series was geared towards 4th through 12th grade teachers. Participants learned about the problematic narratives of Native American history and discussed strategies to help students use primary sources to inform a better understanding of the Native American experience. Over 2,500 teachers attended the virtual institutes worldwide—that's almost 60,000 students that will benefit in the 2020–21 school year alone.

To produce and disseminate the resources, the museum also reaches out to state and local education officials. The museum introduces these officials to its education resources, demonstrating how NK360° can supplement existing curricula and inform developing history and social studies standards. For example, the state of Washington adopted NK360° to supplement its state curriculum guidance.

NK360 ° has also gained the interest of early childhood educators, and we are currently exploring formats that will address the education of young children about Native cultures through literature and objects from the museum’s collection.

As I reflect on the goals and impact of this unique online resource, I like to think of it as paving the way for our schools’ curricula, textbooks, and teaching materials to become more reflective and inclusive of the cultures of all children, giving voice to multiple historical and cultural perspectives to build appreciation and understanding of others’ histories and cultures.

Explore NK360 ° and our school and public programs (also produced using the Essential Understandings ) on our website at www.americanindian.si.edu/nk360 .

Maria Marable-Bunch | READ MORE

Maria Marable-Bunch is the Associate Director for Museum Learning and Programs at the National Museum of the American Indian. Her career in museum education spans over 25 years having worked in museums ranging from history, art, and science. She is also a practicing fine art artist.

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Native American History

Native American history spans an array of diverse groups and leaders, including Sitting Bull, Crazy Horse and Tecumseh, and events like the Trail of Tears, the French and Indian War and the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

Native American History Timeline

Long before Christopher Columbus stepped foot on what would come to be known as the Americas, the expansive territory was inhabited by Native Americans. Throughout the 16th and 17th centuries, as more explorers sought to colonize their land, Native Americans responded in various stages, from cooperation to indignation to revolt. After siding with the French […]

Native American Cultures

The Arctic The Arctic culture area, a cold, flat, treeless region (actually a frozen desert) near the Arctic Circle in present‑day Alaska, Canada and Greenland, was home to the Inuit and the Aleut. Both groups spoke, and continue to speak, dialects descended from what scholars call the Eskimo‑Aleut language family. Because it is such an […]

American Indian Movement (AIM)

The American Indian Movement (AIM), founded in 1968, became the driving force behind the Indigenous civil rights movement.

Trail of Tears

The Trail of Tears was the deadly route Native Americans were forced to follow when they were pushed off their ancestral lands and into Oklahoma by the Indian Removal Act of 1830.

Battle of the Little Bighorn

In 1876, General Custer and members of several Plains Indian tribes, including Crazy Horse and Chief Gall, battled in eastern Montana in what would become known as Custer’s Last Stand.

The buffalo was an essential part of Native American life, used in everything from religious rituals to teepee construction.

Proclamation of 1763

Explore 5 facts about the Proclamation of 1763, a decree originally enacted to calm the tension between Native Americans and colonials, but became one of the earliest causes of the American Revolution.

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War saw two European imperialists go head‑to‑head over territory and marked the debut of the soldier who would become America’s first president.

Why the War of 1812 Was a Turning Point for Native Americans

The conflict was their last, best chance for outside military help to protect their homelands from westward expansion.

How a Cherokee Leader Ensured His People’s Language Survived

Sequoyah spent 12 years working on a writing system for his nation’s language.

How Native American Code Talkers Pioneered a New Type of Military Intelligence

An overheard conversation between two Choctaw Indian soldiers serving in World War I led to a code that confounded German forces.

How Boarding Schools Tried to ‘Kill the Indian’ Through Assimilation

Native American tribes are still seeking the return of their children.

This Day in History

American Indian Movement (AIM) is founded

Deb haaland sworn in as first indigenous cabinet secretary, supreme court rules in mcgirt v. oklahoma, indian reorganization act is signed into law, maria tallchief debuts in “firebird” as the first‑ever american prima ballerina, dr. susan la flesche picotte becomes the first native american woman to graduate from medical school.

- Utility Menu

Pluralism Project Archive

Native american religious and cultural freedom: an introductory essay (2005).

I. No Word for Religion: The Distinctive Contours of Native American Religions

A. Fundamental Diversity We often refer to Native American religion or spirituality in the singular, but there is a fundamental diversity concerning Native American religious traditions. In the United States, there are more than five hundred recognized different tribes , speaking more than two hundred different indigenous languages, party to nearly four hundred different treaties , and courted by missionaries of each branch of Christianity. With traditional ways of life lived on a variety of landscapes, riverscapes, and seascapes, stereotypical images of buffalo-chasing nomads of the Plains cannot suffice to represent the people of Acoma, still raising corn and still occupying their mesa-top pueblo in what only relatively recently has come to be called New Mexico, for more than a thousand years; or the Tlingit people of what is now Southeast Alaska whose world was transformed by Raven, and whose lives revolve around the sea and the salmon. Perhaps it is ironic that it is their shared history of dispossession, colonization, and Christian missions that is most obviously common among different Native peoples. If “Indian” was a misnomer owing to European explorers’ geographical wishful thinking, so too in a sense is “Native American,”a term that elides the differences among peoples of “North America” into an identity apparently shared by none at the time the continents they shared were named for a European explorer. But the labels deployed by explorers and colonizers became an organizing tool for the resistance of the colonized. As distinctive Native people came to see their stock rise and fall together under “Indian Policy,” they resourcefully added that Native or Indian identity, including many of its symbolic and religious emblems, to their own tribal identities. A number of prophets arose with compelling visions through which the sacred called peoples practicing different religions and speaking different languages into new identities at once religious and civil. Prophetic new religious movements, adoption and adaptation of Christian affiliation, and revitalized commitments to tribal specific ceremonial complexes and belief systems alike marked religious responses to colonialism and Christian missions. And religion was at the heart of negotiating these changes. “More than colonialism pushed,” Joel Martin has memorably written, “the sacred pulled Native people into new religious worlds.”(Martin) Despite centuries of hostile and assimilative policies often designed to dismantle the structures of indigenous communities, language, and belief systems, the late twentieth century marked a period of remarkable revitalization and renewal of Native traditions. Built on centuries of resistance as well as strategic accommodations, Native communities from the 1960s on have vigorously pressed their claims to religious self-determination.

B. "Way of Life, not Religion" In all their diversity, people from different Native nations hasten to point out that their respective languages include no word for “religion”, and maintain an emphatic distinction between ways of life in which economy, politics, medicine, art, agriculture, etc., are ideally integrated into a spiritually-informed whole. As Native communities try to continue their traditions in the context of a modern American society that conceives of these as discrete segments of human thought and activity, it has not been easy for Native communities to accomplish this kind of integration. Nor has it been easy to to persuade others of, for example, the spiritual importance of what could be construed as an economic activity, such as fishing or whaling.

C. Oral Tradition and Indigenous Languages Traversing the diversity of Native North American peoples, too, is the primacy of oral tradition. Although a range of writing systems obtained existed prior to contact with Europeans, and although a variety of writing systems emerged from the crucible of that contact, notably the Cherokee syllabary created by Sequoyah and, later, the phonetic transcription of indigenous languages by linguists, Native communities have maintained living traditions with remarkable care through orality. At first glance, from the point of view of a profoundly literate tradition, this might seem little to brag about, but the structure of orality enables a kind of fluidity of continuity and change that has clearly enabled Native traditions to sustain, and even enlarge, themselves in spite of European American efforts to eradicate their languages, cultures, and traditions. In this colonizing context, because oral traditions can function to ensure that knowledge is shared with those deemed worthy of it, orality has proved to be a particular resource to Native elders and their communities, especially with regard to maintaining proper protocols around sacred knowledge. So a commitment to orality can be said to have underwritten artful survival amid the pressures of colonization. It has also rendered Native traditions particularly vulnerable to exploitation. Although Native communities continue to privilege the kinds of knowledge kept in lineages of oral tradition, courts have only haltingly recognized the evidentiary value of oral traditions. Because the communal knowledge of oral traditions is not well served by the protections of intellectual property in western law, corporations and their shareholders have profited from indigenous knowledge, especially ethnobotanical and pharmacological knowledge with few encumbrances or legal contracts. Orality has also rendered Native traditions vulnerable to erosion. Today, in a trend that linguists point out is global, Native American languages in particular are to an alarming degree endangered languages. In danger of being lost are entire ways of perceiving the world, from which we can learn to live more sustainable, balanced, lives in an ecocidal age.

D. "Religious" Regard for the Land In this latter respect of being not only economically land-based but culturally land-oriented, Native religious traditions also demonstrate a consistency across their fundamental diversity. In God is Red ,Vine Deloria, Jr. famously argued that Native religious traditions are oriented fundamentally in space, and thus difficult to understand in religious terms belonging properly tothe time-oriented traditions of Christianity and Judaism. Such a worldview is ensconced in the idioms, if not structures, of many spoken Native languages, but living well on particular landscapes has not come naturally to Native peoples, as romanticized images of noble savages born to move silently through the woods would suggest. For Native peoples, living in balance with particular landscapes has been the fruit of hard work as well as a product of worldview, a matter of ethical living in worlds where non human life has moral standing and disciplined attention to ritual protocol. Still, even though certain places on landscapes have been sacred in the customary sense of being wholly distinct from the profane and its activity, many places sacred to Native peoples have been sources of material as well as spiritual sustenance. As with sacred places, so too with many sacred practices of living on landscapes. In the reckoning of Native peoples, pursuits like harvesting wild rice, spearing fish or hunting certain animals can be at once religious and economic in ways that have been difficult for Western courts to acknowledge. Places and practices have often had both sacred and instrumental value. Thus, certain cultural freedoms are to be seen in the same manner as religious freedoms. And thus, it has not been easy for Native peoples who have no word for “religion” to find comparable protections for religious freedom, and it is to that troubled history we now turn.

II. History of Native American Religious and Cultural Freedom

A. Overview That sacred Native lifeways have only partly corresponded to the modern Western language of “religion,” the free exercise of which is ostensibly protected by the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution , has not stopped Native communities from seeking protection of their freedom to exercise and benefit from those lifeways. In the days of treaty making, formally closed by Congress in 1871, and in subsequent years of negotiated agreements, Native communities often stipulated protections of certain places and practices, as did Lakota leaders in the Fort Laramie Treaty when they specifically exempted the Paha Sapa, subsequently called the Black Hills from land cessions, or by Ojibwe leaders in the 1837 treaty, when they expressly retained “usufruct” rights to hunt, fish, and gather on lands otherwise ceded to the U.S. in the treaty. But these and other treaty agreements have been honored neither by American citizens nor the United States government. Native communities have struggled to secure their rights and interests within the legal and political system of the United States despite working in an English language and in a legal language that does not easily give voice to Native regard for sacred places, practices, and lifeways. Although certain Native people have appealed to international courts and communities for recourse, much of the material considered in this website concerns Native communities’ efforts in the twentieth and twenty-first century to protect such interests and freedoms within the legal and political universe of the United States.

B. Timeline 1871 End of Treaty Making Congress legislates that no more treaties are to be made with tribes and claims “plenary power” over Indians as wards of U.S. government. 1887-1934 Formal U.S. Indian policy of assimilation dissolves communal property, promotes English only boarding school education, and includes informal and formalized regulation and prohibition of Native American ceremonies. At the same time, concern with “vanishing Indians” and their cultures drives a large scale effort to collect Native material culture for museum preservation and display. 1906 American Antiquities Act Ostensibly protects “national” treasures on public lands from pilfering, but construes Native American artifacts and human remains on federal land as “archeological resources,” federal property useful for science. 1921 Bureau of Indian Affairs Continuing an administrative trajectory begun in the 1880's, the Indian Bureau authorized its field agents to use force and imprisonment to halt religious practices deemed inimical to assimilation. 1923 Bureau of Indian Affairs The federal government tries to promote assimilation by instructing superintendents and Indian agents to supress Native dances, prohibiting some and limiting others to specified times. 1924 Pueblos make appeal for religious freedom protection The Council of All the New Mexico Pueblos appeals to the public for First Amendment protection from Indian policies suppressing ceremonial dances. 1924 Indian Citizenship Act Although uneven policies had recognized certain Indian individuals as citizens, all Native Americans are declared citizens by Congressional legislation. 1928 Meriam Report Declares federal assimilation policy a failure 1934 Indian Reorganization Act Officially reaffirms legality and importance of Native communities’ religious, cultural, and linguistic traditions. 1946 Indian Claims Commission Federal Commission created to put to rest the host of Native treaty land claims against the United States with monetary settlements. 1970 Return of Blue Lake to Taos Pueblo After a long struggle to win support by President Nixon and Congress, New Mexico’s Taos Pueblo secures the return of a sacred lake, and sets a precedent that threatened many federal lands with similar claims, though regulations are tightened. Taos Pueblo still struggles to safeguard airspace over the lake. 1972 Portions of Mount Adams returned to Yakama Nation Portions of Washington State’s Mount Adams, sacred to the Yakama people, was returned to that tribe by congressional legislation and executive decision. 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act Specifies Native American Church, and other native American religious practices as fitting within religious freedom. Government agencies to take into account adverse impacts on native religious freedom resulting from decisions made, but with no enforcement mechanism, tribes were left with little recourse. 1988 Lyng v. Northwest Indian Cemetery Protective Association Three Calif. Tribes try to block logging road in federal lands near sacred Mt. Shasta Supreme Court sides w/Lyng, against tribes. Court also finds that AIRFA contains no legal teeth for enforcement. 1990 Employment Division, Department of Human Resources v. Smith Oregon fires two native chemical dependency counselors for Peyote use. They are denied unemployment compensation. They sue. Supreme Court 6-3 sides w/Oregon in a major shift in approach to religious freedom. Scalia, for majority: Laws made that are neutral to religion, even if they result in a burden on religious exercise, are not unconstitutional. Dissent identifies this more precisely as a violation of specific congressional intent to clarify and protect Native American religious freedoms 1990 Native American Graves and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) Mandates return of human remains, associated burial items, ceremonial objects, and "cultural patrimony” from museum collections receiving federal money to identifiable source tribes. Requires archeologists to secure approval from tribes before digging. 1990 “Traditional Cultural Properties” Designation created under Historic Preservation Act enables Native communities to seek protection of significant places and landscapes under the National Historic Preservation Act. 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act Concerning Free Exercise Claims, the burden should be upon the government to prove “compelling state interest” in laws 1994 Amendments to A.I.R.F.A Identifies Peyote use as sacramental and protected by U.S., despite state issues (all regs must be made in consultation with reps of traditional Indian religions. 1996 President Clinton's Executive Order (13006/7) on Native American Sacred Sites Clarifies Native American Sacred Sites to be taken seriously by government officials. 1997 City of Bourne v. Flores Supreme Court declares Religious Freedom Restoration Act unconstitutional 2000 Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) Protects religious institutions' rights to make full use of their lands and properties "to fulfill their missions." Also designed to protect the rights of inmates to practice religious traditions. RLUIPA has notably been used in a number of hair-length and free-practice cases for Native inmates, a number of which are ongoing (see: Greybuffalo v. Frank).

III. Contemporary Attempts to Seek Protection Against the backdrop, Native concerns of religious and cultural freedoms can be distinguished in at least the following ways.

- Issues of access to, control over, and integrity of sacred lands

- Free exercise of religion in public correctional and educational institutions

- Free Exercise of “religious” and cultural practices prohibited by other realms of law: Controlled Substance Law, Endangered Species Law, Fish and Wildlife Law

- Repatriation of Human Remains held in museums and scientific institutions

- Repatriation of Sacred Objects/Cultural Patrimony in museums and scientific institutions

- Protection of Sacred and Other Cultural Knowledge from exploitation and unilateral appropriation (see Lakota Elder’s declaration).

In their attempts to press claims for religious and cultural self-determination and for the integrity of sacred lands and species, Native communities have identified a number of arenas for seeking protection in the courts, in legislatures, in administrative and regulatory decision-making, and through private market transactions and negotiated agreements. And, although appeals to international law and human rights protocols have had few results, Native communities bring their cases to the court of world opinion as well. It should be noted that Native communities frequently pursue their religious and cultural interests on a number of fronts simultaneously. Because Native traditions do not fit neatly into the category of “religion” as it has come to be demarcated in legal and political languages, their attempts have been various to promote those interests in those languages of power, and sometimes involve difficult strategic decisions that often involve as many costs as benefits. For example, seeking protection of a sacred site through historic preservation regulations does not mean to establish Native American rights over access to and control of sacred places, but it can be appealing in light of the courts’ recently narrowing interpretation of constitutional claims to the free exercise of religion. Even in the relative heyday of constitutional protection of the religious freedom of minority traditions, many Native elders and others were understandably hesitant to relinquish sacred knowledge to the public record in an effort to protect religious and cultural freedoms, much less reduce Native lifeways to the modern Western terms of religion. Vine Deloria, Jr. has argued that given the courts’ decisions in the 1980s and 1990s, especially in the Lyng and Smith cases, efforts by Native people to protect religious and cultural interests under the First Amendment did as much harm as good to those interests by fixing them in written documents and subjecting them to public, often hostile, scrutiny.

A. First Amendment Since the 1790s, the First Amendment to the Constitution has held that “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” The former of the amendment’s two clauses, referred to as the “establishment clause” guards against government sponsorship of particular religious positions. The latter, known as the “free exercise” clause, protects the rights of religious minorites from government interference. But just what these clauses have been understood to mean, and how much they are to be weighed against other rights and protections, such as that of private property, has been the subject of considerable debate in constitutional law over the years. Ironically, apart from matters of church property disposition, it was not until the 1940s that the Supreme Court began to offer its clarification of these constitutional protections. As concerns free exercise jurisprudence, under Chief Justices Warren and Burger in the 1960s and 1970s, the Supreme Court had expanded free exercise protection and its accommodations considerably, though in retrospect too few Native communities were sufficiently organized or capitalized, or perhaps even motivated, given their chastened experience of the narrow possibilities of protection under U.S. law, to press their claims before the courts. Those communities who did pursue such interests experienced first hand the difficulty of trying to squeeze communal Native traditions, construals of sacred land, and practices at once economic and sacred into the conceptual box of religion and an individual’s right to its free exercise. By the time more Native communities pursued their claims under the free exercise clause in the 1980s and 1990s, however, the political and judicial climate around such matters had changed considerably. One can argue it has been no coincidence that the two, arguably three, landmark Supreme Court cases restricting the scope of free exercise protection under the Rehnquist Court were cases involving Native American traditions. This may be because the Court agrees to hear only a fraction of the cases referred to it. In Bowen v. Roy 476 U.S. 693 (1986) , the High Court held against a Native person refusing on religious grounds to a social security number necessary for food stamp eligibility. With even greater consequence for subsequent protections of sacred lands under the constitution, in Lyng v. Northwest Cemetery Protective Association 485 U.S. 439 (1988) , the High Court reversed lower court rulings which had blocked the construction of a timber road through high country sacred to California’s Yurok, Karok and Tolowa communities. In a scathing dissent, Harry Blackmun argued that the majority had fundamentally misunderstood the idioms of Native religions and the centrality of sacred lands. Writing for the majority, though, Sandra Day O’Connor’s opinion recognized the sincerity of Native religious claims to sacred lands while devaluing those claims vis a vis other competing goods, especially in this case, the state’s rights to administer “what is, after all, its land.” The decision also codified an interpretation of Congress’s legislative protections in the 1978 American Indian Religious Freedom Act as only advisory in nature. As of course happens in the U.S. judical system, such decisions of the High Court set new precedents that not only shape the decisions of lower courts, but that have a chilling effect on the number of costly suits brought into the system by Native communities. What the Lyng decision began to do with respect to sacred land protection, was finished off with respect to restricting free exercise more broadly in the Rehnquist Court’s 1990 decision in Employment Division, State of Oregon v. Smith 484 U.S. 872 (1990) . Despite nearly a century of specific protections of Peyotism, in an unemployment compensation case involving two Oregon substance abuse counselors who had been fired because they had been found to be Peyote ingesting members of the Native American Church , a religious organization founded to secure first amendment protection in the first place, the court found that the state’s right to enforce its controlled substance laws outweighed the free exercise rights of Peyotists. Writing for the majority, Justice Scalia’s opinion reframed the entire structure of free exercise jurisprudence, holding as constitutional laws that do not intentionally and expressly deny free exercise rights even if they have the effect of the same. A host of minority religious communities, civil liberties organizations, and liberal Christian groups were alarmed at the precedent set in Smith. A subsequent legislative attempt to override the Supreme Court, the Religious Freedom Restoration Act , passed by Congress and signed into law in 1993 by President Clinton was found unconstitutional in City of Bourne v. Flores (1997) , as the High Court claimed its constitutional primacy as interpreter of the constitution.

i. Sacred Lands In light of the ruling in Lyng v. Northwest Cemetery Protective Association (1988) discussed immediately above, there have been few subsequent attempts to seek comparable protection of sacred lands, whether that be access to, control of, or integrity of sacred places. That said, three cases leading up to the 1988 Supreme Court decision were heard at the level of federal circuit courts of appeal, and are worthy of note for the judicial history of appeals to First Amendment protection for sacred lands. In Sequoyah v. Tennessee Valley Authority , 19800 620 F.2d 1159 (6th Cir. 1980) , the court remained unconvinced by claims that a proposed dam's flooding of non-reservation lands sacred to the Cherokee violate the free excersice clause. That same year, in Badoni v. Higginson , 638 F. 2d 172 (10th Cir. 1980) , a different Circuit Court held against Navajo claims about unconstitutional federal management of water levels at a am desecrating Rainbow Arch in Utah. Three years later, in Fools Crow v. Gullet , 760 F. 2d 856 (8th Cir. 1983), cert. Denied, 464 U.S.977 (1983) , the Eighth Circuit found unconvincing Lakota claims to constitutional protections to a vision quest site against measures involving a South Dakota state park on the site.

ii. Free Exercise Because few policies and laws that have the effect of infringing on Native American religious and cultural freedoms are expressly intended to undermine those freedoms, the High Court’s Smith decision discouraged the number of suits brought forward by Native communities under constitutional free exercise protection since 1990, but a number of noteworthy cases predated the 1990 Smith decision, and a number of subsequent free exercise claims have plied the terrain of free exercise in correctional institutions. Employment Division, State of Oregon v. Smith (1990)

- Prison:Sweatlodge Case Study

- Eagle Feathers: U.S. v. Dion

- Hunting for Ceremonial Purposes: Frank v. Alaska

iii. No Establishment As the history of First Amendment jurisprudence generaly shows (Flowers), free exercise protections bump up against establishment clause jurisprudence that protects the public from government endorsement of particular traditions. Still, it is perhaps ironic that modest protections of religious freedoms of tiny minorities of Native communities have undergone constitutional challenges as violating the establishment clause. At issue is the arguable line between what has been understood in jurisprudence as governmental accommodations enabling the free exercise of minority religions and government endorsement of those traditions. The issue has emerged in a number of challenges to federal administrative policies by the National Park Service and National Forest Service such as the voluntary ban on climbing during the ceremonially significant month of June on what the Lakota and others consider Bear Lodge at Devil’s Tower National Monument . It should be noted that the Mountain States Legal Foundation is funded in part by mining, timbering, and recreational industries with significant money interests in the disposition of federal lands in the west. In light of courts' findings on these Native claims to constitutional protection under the First Amendment, Native communities have taken steps in a number of other strategic directions to secure their religious and cultural freedoms.

B. Treaty Rights In addition to constitutional protections of religious free exercise, 370 distinct treaty agreements signed prior to 1871, and a number of subsequent “agreements” are in play as possible umbrellas of protection of Native American religious and cultural freedoms. In light of the narrowing of free exercise protections in Lyng and Smith , and in light of the Court’s general broadening of treaty right protections in the mid to late twentieth century, treaty rights have been identified as preferable, if not wholly reliable, protections of religious and cultural freedoms. Makah Whaling Mille Lacs Case

C. Intellectual Property Law Native communities have occasionally sought protection of and control over indigenous medicinal, botanical, ceremonial and other kinds of cultural knowledge under legal structures designed to protect intellectual property and trademark. Although some scholars as committed to guarding the public commons of ideas against privatizing corporate interests as they are to working against the exploitation of indigenous knowledge have warned about the consequences of litigation under Western intellectual property standards (Brown), the challenges of such exploitation are many and varied, from concerns about corporate patenting claims to medicinal and agricultural knowledge obtained from Native elders and teachers to protecting sacred species like wild rice from anticipated devastation by genetically modified related plants (see White Earth Land Recovery Project for an example of this protection of wild rice to logos ( Washington Redskins controversy ) and images involving the sacred Zia pueblo sun symbol and Southwest Airlines to challenges to corporate profit-making from derogatory representations of Indians ( Crazy Horse Liquor case ).

D. Other Statutory Law A variety of legislative efforts have had either the express purpose or general effect of providing protections of Native American religious and cultural freedoms. Some, like the Taos Pueblo Blue Lake legislation, initiated protection of sacred lands and practices of particular communities through very specific legislative recourse. Others, like the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act , enacted broad protections of Native American religious and cultural freedom [link to Troost case]. Culminating many years of activism, if not without controversy even in Native communities, Congress passed the American Indian Religious Freedom Act , signed into law in 1978 and amended in 1993, in order to recognize the often difficult fit between Native traditions and constitutional protections of the freedom of “religion” and ostensibly to safeguard such interests from state interference. Though much heralded for its symbolic value, the act was determined by the courts (most notably in the Lyng decision upon review of the congressional record to be only advisory in nature, lacking a specific “cause for action” that would give it legal teeth. To answer the Supreme Court's narrowing of the scope of free exercise protections in Lyng and in the 1990 Smith decision, Congress passed in 2000 the Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) restoring to governments the substantial burden of showing a "compelling interest" in land use decisions or administrative policies that exacted a burden on the free exercise of religion and requiring them to show that they had exhausted other possibilities that would be less burdensome on the free exercise of religion. Two other notable legislative initiatives that have created statutory protections for a range of Native community religious and cultural interests are the 1966 National Historic Preservation Act and the Native American Language Act legislation beginning to recognize the significance and urgency of the protection and promotion of indigenous languages, if not supporting such initiatives with significant appropriations. AIRFA 1978 NAGPRA 1990 [see item h. below] Native American Language Act Religious Land Use and Institutionalized Persons Act (RLUIPA) 2000 National Historic Preservation Act [see item g below]

E. Administrative and Regulatory Policy and Law As implied in a number of instances above, many governmental decisions affecting Native American religious and cultural freedom occur at the level of regulation and the administrative policy of local, state, and federal governments, and as a consequence are less visible to those not locally or immediately affected.

F. Federal Recognition The United States officially recognizes over 500 distinct Native communities, but there remain numerous Native communities who know clearly who they are but who remain formally unrecognized by the United States, even when they receive recognition by states or localities. In the 1930s, when Congress created the structure of tribal governments under the Indian Reorganization Act, many Native communities, including treaty signatories, chose not to enroll themselves in the recognition process, often because their experience with the United States was characterized more by unwanted intervention than by clear benefits. But the capacity and charge of officially recognized tribal governments grew with the Great Society programs in the 1960s and in particular with an official U.S. policy of Indian self-determination enacted through such laws as the 1975 Indian Self Determination and Education Act , which enabled tribal governments to act as contractors for government educational and social service programs. Decades later, the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act formally recognized the authority of recognized tribal governments to engage in casino gaming in cooperation with the states. Currently, Native communities that remain unrecognized are not authorized to benefit from such programs and policies, and as a consequence numerous Native communities have stepped forward to apply for federal recognition in a lengthy, laborious, and highly-charged political process overseen by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Office of Federal Acknowledgment . Some communities, like Michigan’s Little Traverse Band of Odawa have pursued recognition directly through congressional legislation. As it relates to concerns of Native American religious and cultural freedom, more is at stake than the possibility to negotiate with states for the opening of casinos. Federal recognition gives Native communities a kind of legal standing to pursue other interests with more legal and political resources at their disposal. Communities lacking this standing, for example, are not formally included in the considerations of the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (item H. below).

G. Historic Preservation Because protections under the National Historic Preservation Act have begun to serve as a remedy for protection of lands of religious and cultural significance to Native communities, in light of first amendment jurisprudence since Lyng , it bears further mention here. Native communities seeking protections through Historic Preservation determinations are not expressly protecting Native religious freedom, nor recognizing exclusive access to, or control of sacred places, since the legislation rests on the importance to the American public at large of sites of historic and cultural value, but in light of free exercise jurisprudence since Lyng , historic preservation has offered relatively generous, if not exclusive, protection. The National Historic Preservation Act as such offered protection on the National Register of Historic Places, for the scholarly, especially archeological, value of certain Native sites, but in 1990, a new designation of “traditional cultural properties” enabled Native communities and others to seek historic preservation protections for properties associated “wit cultural practices or beliefs of a living community that (a) are rooted in that community’s history, and (b) are important in maintaining the continuing cultural identity of the community.” The designation could include most communities, but were implicitly geared to enable communities outside the American mainstream, perhaps especially Native American communities, to seek protection of culturally important and sacred sites without expressly making overt appeals to religious freedom. (King 6) This enabled those seeking recognition on the National Register to skirt a previous regulatory “religious exclusion” that discouraged inclusion of “properties owned by religious institutions or used for religious purposes” by expressly recognizing that Native communities don’t distinguish rigidly between “religion and the rest of culture” (King 260). As a consequence, this venue of cultural resource management has served Native interests in sacred lands better than others, but it remains subject to review and change. Further it does not guarantee protection; it only creates a designation within the arduous process of making application to the National Register of Historic Places. Pilot Knob Nine Mile Canyon

H. Repatriation/Protection of Human Remains, Burial Items, and Sacred Objects Culminating centuries of struggle to protect the integrity of the dead and material items of religious and cultural significance, Native communities witnessed the creation of an important process for protection under the 1990 Native American Graves and Repatriation Act . The act required museums and other institutions in the United States receiving federal monies to share with relevant Native tribes inventories of their collections of Native human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of “cultural patrimony” (that is objects that were acquired from individuals, but which had belonged not to individuals, but entire communities), and to return them on request to lineal descendants or federally recognized tribes (or Native Hawaiian organizations) in those cases where museums can determine cultural affiliation, or as often happens, in the absence of sufficiently detailed museum data, to a tribe that can prove its cultural affiliation. The law also specifies that affiliated tribes own these items if they are discovered in the future on federal or tribal lands. Finally, the law also prohibits almost every sort of trafficking in Native American human remains, burial objects, sacred objects, and items of cultural patrimony. Thus established, the process has given rise to a number of ambiguities. For example, the law’s definition of terms gives rise to some difficulties. For example, “sacred objects” pertain to objects “needed for traditional Native American religions by their present day adherents.” Even if they are needed for the renewal of old ceremonies, there must be present day adherents. (Trope and Echo Hawk, 143). What constitutes “Cultural affiliation” has also given rise to ambiguity and conflict, especially given conflicting worldviews. As has been seen in the case of Kennewick Man the “relationship of shared group identity” determined scientifically by an archeologist may or may not correspond to a Native community’s understanding of its relation to the dead on its land. Even what constitutes a “real” can be at issue, as was seen in the case of Zuni Pueblo’s concern for the return of “replicas” of sacred Ahayu:da figures made by boy scouts. To the Zuni, these contained sacred information that was itself proprietary (Ferguson, Anyon, and Lad, 253). Disputes have arisen, even between different Native communities claiming cultural affiliation, and they are adjudicated through a NAGPRA Review Committee , convened of three representatives from Native communities, three from museum and scientific organizations, and one person appointed from a list jointly submitted by the other six.