Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Autism Spectrum Disorder Research Proposal for Improved Social Interactions and Communication Skills

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is characterized by detrimental deficits in social communication and interaction, restrictive and repetitive patterns of behaviors, interest or activities. It is estimated that 70% of children with ASD suffer from uncontrollable behavioral outbursts that increase their peer isolation along with the stress of their caregivers. These uncontrollable and involuntary behaviors are stressful to the individual in many ways. This research study is being conducted to review the benefits of encouraging an increase in organized social activities between people with and without ASD in hopes that some of the uncontrollable behavioral outbursts that previously increased peer isolation will decrease or disappear over experience with organized social activities. Previous research on this study has been thoroughly reviewed and examined in order to gain a crucial understanding of this topic. The research potential from the interview style experiment will assist in future programs with the complete integration of children, adolescents, and young adults into the mainframe of society.

Related Papers

Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders

Nina Linneman

Frontiers in Psychology

M. Teresa Anguera

Andrew Yockey , Amanda Tipkemper

Adolescents with autism spectrum disorders (ASDs) often have difficulty with social interactions. This study aimed to increase social interactions in adolescents with ASD. Teachers developed friendship goals based on social skills outlined in the teaching-family model. Teachers provided reinforcement to students for displaying positive behaviors linked to goals throughout the school day. The current study also examined student, parent, and teacher perceptions of adolescent social interactions using interviews and surveys. During their interviews, adolescents reported that they were often lonely. Parents indicated that their children needed to learn skills to improve peer interactions. Observers used a behavioral system to quantify the types of social interactions displayed by adolescents. After a baseline period, teachers developed an intervention focusing on friendship goals to encourage students to engage in social interactions. The intervention had a limited impact on improving social interactions. The findings for the current study indicated limited improvement in social interactions resulting from the teacher-directed intervention. Parents, adolescents, and teachers highlighted the need for adolescents with ASDs to find ways to utilize social skills to reduce loneliness and improve peer support. Future research investigating the impact of teaching interaction/friendship skills around the students' interests (e.g., sports) may help them learn skills to interact more with peers. Additionally, assessing the impact of individualized planning to improve each adolescent's skills may be more influential in changing social behavior than a system-wide intervention, such as the one implemented in this study.

Focus on autism and other developmental disabilities

Rose Mason , Debra Kamps , Sarah Feldmiller

Jairo Rodríguez-Medina

International Journal of Early Childhood Special Education

ZUHAR RENDE BERMAN

Steven Kapp

Sander Begeer

Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Syeda Sarah Abbas

Exceptionality Education International

Jennifer Ozuna

Barbara Liberi

School Psychology Review

Felice Orlich

Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders

Journal of Educational, Health and Community Psychology

Faqihul Muqoddam

Journal of autism and developmental disorders

Yu-Wei Chen

International Journal of Science & Healthcare Research

Rajeev Ranjan

Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry

Erin Rotheram-Fuller

Developmental Neurorehabilitation

Sophie Goldingay

Psychology in the Schools

Lynn Koegel

Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools

Heather Willis

Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions

Robert Koegel

Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines

Journal ijmr.net.in(UGC Approved)

Autism : the international journal of research and practice

kristen Bottema-beutel

Kathryn Drager

Linda Heitzman-Powell

Cynthia A Waugh

Gary Sasso , Debra Kamps

Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities

Debra Kamps

Erin Fuller

International Journal of Academic Research in Progressive Education and Development

MARLISSA OMAR

Nirit Bauminger Zviely

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

5 Research Topics for Applied Behavior Analysis Students

Featured Programs

- Top 15 Online Applied Behavior Analysis Bachelors Degree and BCaBA Coursework Programs

- Top 25 Best Applied Behavior Analysis Programs

Whether you are in an ABA program right now or would like to be soon, it may be time to start thinking about research topics for your thesis or dissertation. All higher-level ABA courses will require students to have substantial independent research experience, which includes setting up a research experiment or trial, taking data, analyzing data, and suggesting next steps. And this also includes writing a professional paper either to turn in or submit to a scientific journal.

Overall, there will be quite a bit of research and writing that occurs in an ABA program.

If you’re currently in a program, read about these five research topic examples that might pique your curiosity.

1. Industrial Safety

In one classic study from 1987 , researchers examined how creating a token economy might increase safety at dangerous industrial sites. The study rewarded pit-mine workers when they and their colleagues avoided incidents that resulted in personal injury or equipment damage. They also rewarded workers who took extra steps to ensure the safety of others and report incidents. By using applied behavior analysis to incentivize self-motivated conduct modification, the researchers created improvements that persisted for years.

Behavior-Based Safety (BBS) “is an approach to occupational risk management that uses the science of behavior to increase safe behavior and reduce workplace injuries.”

Successful applications of BBS programs adhere to the following key principles ( Geller, 2005) :

- Focus interventions on specific, observable behaviors.

- Look for external factors to understand and improve behavior.

- Use signals to direct behaviors, and use consequences to motivate workers.

- Focus on positive consequences (not a punishment) to motivate behavior.

- Use a science-based approach to test and improve BBS interventions.

- Don’t let scientific theory limit the possibilities for improving BBS interventions.

- Design interventions while considering the feelings and attitudes of workers within the organization.

The field of BBS can always improve, and your contribution to it through research can help. Consider choosing industrial safety and ABA as one of your research topics.

2. Autism Spectrum

Advocates also note that there remains a small but significant portion of autism sufferers who don’t respond to conventional techniques. There’s an ongoing need to study alternative methods and explore why certain approaches don’t work with some individuals. ABA techniques and their relation to autism-spectrum disorders will continue to pose important research questions for some time.

Not only can you conduct your own research (legally and ethically), and study other works of scientific literature, but you can be in the middle of it all like the professionals at the Marcus Autism Center do.

The center at Marcus is one of the most highly-regarded in the field of autism in the United States. They have a behavioral analysis research lab where clinician-researchers with expertise in applied behavior analysis.

According to their site:

“Although this work continues, the Behavior Analysis Research Lab recently expanded its research focus to include randomized clinical trials of behavioral interventions for core symptoms of autism, as well as co-occurring conditions or behaviors, such as elopement (e.g., wandering or running away) and encopresis (e.g., toileting concerns). Our goal is to disseminate the types of interventions and outcomes that can be achieved using ABA-based interventions to broader audiences by studying them in larger group designs.”

Depending on where you live, there may be experiential research opportunities for you as a student to dive into, such as the positions they have open at Marcus.

3. Animal and Human Intelligence

For example, researchers note that in 2010, dogs bit 4.5 million Americans annually, with 20 percent of bites needing medical intervention. They further suggest that ABA can provide a valid framework for understanding why such bites occur and preventing them. Similarly, studies that examine why rats may be able to detect tuberculosis or how service dogs help people involve learning about these creatures’ behaviors.

AAB, or Applied Animal Behavior , is an example of an organization that conducts research, supports animal behaviorists, and promotes the well-being of all animals that work in an applied setting.

The Animal Behavior Society is another example, which is the leading professional organization in the United States that studies animal behavior. They say that animal behaviorists can be educated in a variety of disciplines, including psychology biology, zoology, or animal science.

There is definitely room for more research in the field of animal behavior and its impact on humans.

4. Criminology

One study showed a potential correlation between allowing high-risk students to choose their schools and their likelihood of criminal involvement. While school choice didn’t affect academic achievement, it generally lowered the risk that people would commit crimes later in life.

Criminologists, behavioral psychologists, and forensic psychologists are all hired to work with local law enforcement and even the FBI to determine the motives of criminals along with the societal impacts, generational changes and other trends that might help be more proactive in the future. Mostly, they investigate why people commit crimes.

If you have ever watched a forensics TV show like Crime Scene Investigation (CSI) then you have a good idea of what their job entails. Between criminal profiling, working directly with a team, and investigating and solving cases is what it’s all about.

Experts on applied behavior analysis state:

“Its value to law enforcement investigations and criminal rehabilitation efforts make it an essential tool for any forensic psychologist. Research shows that successful application of applied forensic behavior analysis can lead to lower recidivism rates in convicts and a higher success rate in apprehending criminal suspects.”

Applied behavior analysis students who research these fields could play big roles in advancing societal knowledge.

5. Education

ABA is all around in education––you just cannot escape it! Everything, even academics, revolves around behavior . Whether it is on the county level or the classroom, there are FBAs, BIPs, data collection, positive reinforcement, consequences, token economies, trial and error, behavioral interventions, and much more.

And teachers aren’t the only staff privy to ABA. School social workers, school counselors, behavioral specialists, and paraprofessionals all have access to ABA and can implement strategies based on individual student needs.

Education techniques rely heavily on applied behavior analysis. Instructors may be tasked with giving consequences to students or devising custom lessons, and these tasks often involve understanding how to incentivize appropriate behavior while motivating learners.

Like other kinds of ABA, applied education research also provides the opportunity for internships and postgraduate residency programs. Because many of this field’s modern foundations lie in education, classroom-based research is a natural fit for students who want to apply their discoveries.

Research Topics for Applied Behavior Analysis Students: Conclusion

Applied behavior analysis is complex, but studying it is extremely rewarding. This field provides students at all educational levels with ample opportunities to contribute to scientific knowledge and better people’s lives in the process. There are almost too many fields to choose from in terms of where you want to lean. Think about your interests, what you have access to in your surrounding area (unless you are willing to move), and consider what type of research will help you move forward in your educational career and beyond. There are ABA programs and careers out there waiting for each of you!

Brittany Cerny

Master of Education (M.Ed.) | Northeastern State University

Behavior and Learning Disorders | Georgia State University

Updated December 2021

- What are the characteristics of a teacher using ABA?

- How Do ABA Graduate Certificates and Masters Programs Differ?

- 30 Best Books on Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA)

- How Long Does it Take to Get My ABA Certificate?

- ABA (Online Master’s)

- ABA (Online Grad Certificate)

- ABA (Online Bachelor’s)

- ABA (Master’s)

- Autism (Online Master’s)

- Ed Psych (Online Master’s)

- 30 Things Parents of Children on the Autism Spectrum Want You to Know

- 30 Best ABA Book Recommendations: Applied Behavior Analysis

- 30 Best Autism Blogs

- 101 Great Resources for Homeschooling Children with Autism

- 10 Most Rewarding Careers for Those Who Want to Work with Children on the Autism Spectrum

- History’s 30 Most Inspiring People on the Autism Spectrum

- 30 Best Children’s Books About the Autism Spectrum

- 30 Best Autism-Friendly Vacations

- 30 Best Book, Movie, and TV Characters on the Autism Spectrum

- 15 Best Comprehensive Homeschool Curricula for Children with Autism 2020

Employer Rankings

- Top 10 Autism Services Employers in Philadelphia

- Top 10 Autism Services Employers in Miami

- Top 10 Autism Services Employers in Houston

- Top 10 Autism Services Employers in Orlando

Dr. Mary Barbera

Research Topics in ABA for Practitioners with Dr. Amber Valentino

As professionals, practitioners, clinicians, and even parents we share a common goal of wanting to make the world a better place for our children, a big way to do this is through research. Dr. Amber Valentino, author of Applied Behavior Analysis Research Made Easy, is on the podcast to discuss the importance as well as logistics of research in the field.

ABA Research Design

Many peer reviewed, published journal requirements involve really drilling down to specific topics and definitive objects of change. This can be an obstacle in the ABA field for practitioners. But this isn’t the end of the line for research. In its truest form, Applied Behavior Analysis research is messy, it’s a combination of big ideas and discussion. Knowledge is one of the biggest barriers in the profession of ABA, more research and more access to research is the solution.

Transfer Trial ABA

I’ve been able to work on several studies and trials with my mentor, Dr. Rick Kubina, that I talk about in this episode. In 2005, I coauthored a peer reviewed journal article, Using Transfer Procedures to Teach Tacts to a Child with Autism. This study was born out of work done with my son Lucas to correct a tact error with greetings. I never published this study because of the mixed procedures but I did present, and all 4 of the subjects learned equally as well with this method and Lucas only learned this way. Just a few years later, I was able to meet a Doctor who did his dissertation on transfer procedures and actually quoted my work on that study. The need for studies and for information is there.

Dr. Valentino is the Chief Clinical Officer for Trumpet Behavioral Health, she is very passionate about advocating for research with practitioners. Her book Applied Behavior Analysis Research Made Easy: A Handbook for Practitioners Conducting Research Post-Certification, is a great read for professionals who want to contribute research to the field, break barriers, and get started. You can find out more about her on the TBH website as well as her personal blog, Behavior-Mom.

Dr. Amber Valentino On The Turn Autism Around Podcast

Dr. Valentino currently serves as the Chief Clinical Officer for Trumpet Behavior Health where she develops workplace culture initiatives, supports clinical services, leads all research and training activities, and builds clinical standards. Her primary clinical and research interests span a variety of topics including verbal behavior, ways to connect the research to practice gap, professional ethics, and effective supervision. Dr. Valentino serves as an Associate Editor for Behavior Analysis in Practice and previously served as an Associate Editor for The Analysis of Verbal Behavior. She is on the editorial board for the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis (JABA) and serves as a frequent reviewer for several behavior analytic journals. She is the author of the book: Applied Behavior Analysis Research Made Easy: A Handbook for Practitioners Conducting Research Post-Certification. She works to support dissemination of behavior analysis to the general parent population through her personal website, behavior-mom.com.

YOU’LL LEARN:

- Why is it important for practitioners to conduct research?

- How can applied research help the field of ABA and autism?

- What are obstacles for practitioners to complete or publish research?

- How to navigate solutions when your study isn’t approved for publishing?

- What are the many ways practitioners can initiate studies and research?

- Do you have to identify a mechanism of change in a study?

- How to access knowledge to conduct research?

- Sign up for a free workshop online for parents & professionals

New Case Study: Online Parent ABA Training and Expressive Language in a Toddler Diagnosed with Autism

- Autism Success Story with Michele C. – Autism Mom, ABA Help for Professionals and Parents

- Autism Case Study with Michele C : From 2 Words to 500 Words with ABA Online Course

- Using Transfer Procedures to Teach Tacts to a Child with Autism

- The Effects of Fluency-Based Autism Training on Emerging Educational Leaders

- The Experiences of “Autism Mothers” who become Behavior Analysts: A Qualitative Study

- Teaching a Child With Autism to Mand for Information Using “How”

- Dr. Rick Kubina: Fluency and Precision Teaching

- Dr. Mark Sundberg – Using VB-MAPP to Assess and Teach Language

- Free Potty Guide

- Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less: McKeown, Greg: 8601407068765: Amazon.com: Books

- Applied Behavior Analysis Research Made Easy – Amazon.com

- Amber Valentino, Chief Clinical Officer – Trumpet Behavioral Health

- Behavior Mom

Dr. Amber Valentino – Turn Autism Around Podcast Transcript

Transcript for Podcast Episode: 165 Research Topics in ABA for Practitioners with Dr. Amber Valentino Hosted by: Dr. Mary Barbera Guest: Dr. Amber Valentino

Mary: You're listening to the Turn Autism Around podcast, episode number one hundred and sixty five. Today we are talking about applied research and how to get research from practice to publication and how to make the world a better place for our kids and our clients. Dr. Amber Valentino is the guest. She serves as chief clinical officer for Trumpet Behavior Health. She's also the author of a brand new book called Applied Behavior Analysis. Research Made Easy. And she works to support dissemination of behavior analysis to the general parent population. And she also has a personal website called Behavior-Mom.com. So you should check that out. The episode is really great. I know when you hear research, you're thinking, Oh, this is going to be boring. It is not boring. I think it's filled with really good, practical information for everyone listening. So let's get to this important episode with Dr. Amber Valentino.

Welcome to the Turn Autism Around podcast for both parents and professionals in the autism world who want to turn things around, be less stressed and lead happier lives. And now your host, Autism Mom, Behavior Analyst, and bestselling author, Dr. Mary Barbera.

Mary: OK, thank you so much Amber for joining us today. I'm super excited to talk to you.

Dr. Valentino: Thank you so much. Overjoyed to be here. Thanks for having me.

Mary: Yeah. So why don't you tell our listeners and I don't know the answer to this? Describe your fall into the autism and ABA world.

Amber Valentino on the Turn Autism Around Pocast

Dr. Valentino: Yeah. So I imagine I have a story that's very similar to other people's story, and that is I was 18 years old. I was a new college freshman and I had a work study job in Ohio and I ran out of money. The work study program sort of capped. I needed a way to pay my bills. So I was searching around campus. This was in the 90s, not to date myself, but I was searching around campus trying to find a job. And I saw this just lovely flier for working with a kid in his home and doing this thing called ABA. And at that time, I was an English major, so I think that I had any interest in children or working with children in any way. But, you know, fast forward, I applied for the job, got the job, and that just started now over a 20 year career and commitment to people with autism and applied behavior analysis. And I just I fell in love with the work then, and I still love it to this day.

Mary: Yeah, that is a very common pathway. I think, you know, almost all of the professionals I've interviewed have started that way.

Dr. Valentino: So, yeah, and it was, you know, I was listening to one of your other podcasts and you were talking about how around that time there really was no managed care at all. There was no support in that caught me thinking of my own experience. And at the time, you know, in Ohio and I mean everywhere, these families just paid out of pocket. So this family was paying me out of pocket for my time and all of the therapists 40 hours a week for their young son. They were flying a consultant in from Wisconsin to work with them. And it was interesting to listen to your experience and just to remember where we are and where we are today with services. And there's still a lot of work to be done, but certainly cares a lot more accessible now than it was then.

Mary: Yeah, definitely. OK, so you wrote a book and I just found out about it. I reached out to you for this interview and you were nice enough to send me an electronic copy of the book, so I don't have it to hold up at this moment. But it's called Applied Behavior Analysis: Research Made Easy a Handbook for Practitioners Conducting Research Post Certification.

Dr. Valentino: It's a mouthful.

Mary: Yeah, I'm you know, ABA Research Made Easy, that's easy. So why did you write this book and how did you get into the whole research world?

ABA Research Made Easy:

Dr. Valentino: Oh, awesome. Well, I'll answer the second question first, because that kind of leads into how I wrote this book. You know, I've always been a practitioner, I've always wanted to be a practitioner, and I have always wanted to help families. And so I early in my career was fortunate to be in a position where I applied research was kind of a thing. It was it was a thing people did. And I got integrated early in my career and did some applied studies, published some, but made it made a pretty significant career change about a decade ago. And at that time, I thought, Well, I'm not really going to do research anymore. I'm taking a job as a clinician. I'm going to have a caseload and work with families and provide supervision and all that good stuff. And that was the case for a few months. And then a wonderful mentor of mine, Dr. Linda LeBlanc, who was at Trumpet Behavioral Health at that time, really showed me that you can be a practitioner and you can do applied research and you can be both. And so I opened the door to seeing research in a different way and just continued on that path and was able to do some really good work with my clients. That was systematic and had good experimental control and had a story to tell. And so over the years, I've been able to to publish that, which has been which has been wonderful.

Mary: Yeah. So I I know I've seen Dr. Linda LeBlanc present at conferences and I know her great work. I've read a lot of her research studies. I haven't had her on the show yet, so I will definitely be...

Dr. Valentino: Next guest. Yeah, yeah.

Mary: So your book came out and then recently came out just at the end of the year.

Dr. Valentino: It recently came out. Yeah, so. So the second part of that was how did I write a book? It's really funny. I was not planning to write a book. I don't know that a lot of people are right. It certainly was a distant goal for me. I thought someday I'd like to write a book and it's kind of funny. The new Harbinger publications contacted me and said, Would you like to write a book and I was very pregnant with my son, and I said, no, I don't want to write a book, that's crazy. But, you know, I sat back and thought about it and I said, Well, if not now when, you know, this might be the opportunity. And so I signed the contract the day before my son was due. And you know, it's funny. When we first started working together, we actually didn't have a topic. They kind of contacted me on what we saw, how they got my name. But we were talking about supervision, ethics, you some of the publications that I, I have done and I threw this one in here because we had published a study. My colleague doctor just wanted go, and I had published a study about barriers to for practitioners in conducting research. And I said, Oh, this might be kind of cool. And the publisher did their research and examined it a little bit and said, We think this is the topic. And, you know, and then it was born. And so I feel blessed that the opportunity came my way. And several years later, here we are. We have it in print and it's available for people to buy.

Mary: Yeah. So I know we're going to talk about your research studies and my research studies that I publish because I have also been in the autism world for over two decades, and I am very interested in research that really makes a difference. And I get super frustrated when people, you know, are trying to reference 1995 study on some specific a little thing and trying to justify, you know, procedures that just don't make sense anymore. But let's start with and I was able to read a good chunk of your book, maybe half or three quarters of your book, which was great and I would highly recommend it. So the first few chapters you talk about why we as practitioners should do research. And so why? Why should people listening? And we have a lot of parents listening and we are going to pull it back to be practical and kind of have you thinking about you and your team and and just how you can benefit from knowing about research and looking into it and encouraging your professionals who are working with your child to also do research? So so why should we as practitioners do research?

Dr. Valentino: Yeah, it's such a great question and so great. I think I have a whole chapter dedicated to that in the book. You know, behavior analysis is really unique in that the methods that researchers use to examine basic and applied topics are the same methods that practitioners use to figure out if their interventions are effective. And so there are a whole host of reasons, but the first one that comes to mind and the one that's really at the forefront is that it makes you a better practitioner. Right. So all of those things that we do from a research perspective, we have good treatment integrity we have inner observer agreement. We have a good experimental control. Those things aren't just good for a research study, they're good for your client, they're good for effective intervention and evaluating the impact of your services. And so I like to give this analogy, and I like to say, well, you know, let's say you implement an intervention with a child and you simply just do an AB design, right? So you have baseline and then you go in intervention and you say it, that's it. It works, and you want to start to disseminate that. And so you're about to invest a whole lot of time and effort into training people to implement this intervention. Will you want to make sure that that intervention is actually the thing that caused the change, right? So a reversal, whatever design that you have is going to help you make sure that that investment is going to be worth it both for a client. But then it also happens to be good for research study as well. So. So the benefits to practitioners, even if you're study or your case never gets published, you're still doing really good clinical work, which I think is the take home message and super important.

Mary: Yeah, I know early on from 2003 to 2010, I was the lead behavior analyst for the Pennsylvania Verbal Behavior Project, which is now known as the Patten ABA Supports Initiative. But in that in part of that, it was a whole it was a whole big project is still is going strong many, many years later. But part of that was we wanted to not only train behavior analysts and kind of home grow, if you will, behavior analysts, but we wanted to show that our interventions were effective because we were getting lots of money from a state government agency. And so we wanted to show that what we were doing was better than what was previously done for kids in public school autism classrooms. And so part of the initiative was was actually requiring behavior analyst. To set up a little research studies and to have real designs and have inter observer agreement and then to meet once or twice a year or to to actually present those those publications and. And I think when you when you do research and I have done research and we're going to talk about your research and my research, but when you do research and you, you publish it or you present it, you do tend to think differently then. Yeah. After that, you're like, Wow, you know? Yeah. One one example. And I think people in my audience will relate to this is is one of the case studies I remember was trying to see if teaching kids to answer questions like an intraverbal response. If that was better with a tact, a label to enterable transfer or if that was better as an echoic to interverbral transfer and just. Kicking out these these questions to ask, you know, we had lists of questions and we were trying to figure out like what to ask, and I remember one question was where are prisoners kept? And I was like, Oh my God, that is so confusing, because you would need to know, you know, a prison is synonymous with a jail. You would need to know the past tense of keeping is kept. You would need to know, you know, all of this abstract language. It makes you realize how complicated languages. And so when you are really picking out, you know these things in it, it makes you really think differently.

Dr. Valentino: Oh, it really does in such a good example. And you know, the other part of that is that when you're conducting research, you're also reading. Right. And so if you want to dig in and kind of figure out what questions haven't been answered in the literature yet, a huge part of that is reading and being knowledgeable on a topic and knowing what's out there already just naturally makes you a better practitioner. So there's this whole process of reading and formulating a question and digging in like you described that we just we all benefit our clients benefit and you benefit as a practitioner by by engaging in it. It's that even if nothing comes of it in terms of a publication or a presentation, there's still a process there that's extraordinarily valuable.

Mary: Yeah. So you talk in your book about two big research gaps. Can you tell us what they are? Yeah.

Dr. Valentino: So I think about the research to practice gap as being pretty bi directional, right? So if you just do a Google search for research to practice Gap, it's present in all disciplines. All disciplines have this in a human resources. You know, every discipline identifies this. And so it's it's the same for behavior analysis. And so there's sort of two ways this can go. The first is that obviously there is research that's being published that is sort of delayed or doesn't hit the practitioner population as quickly as it could. So there's best practices out there, but practitioners just don't know about them because they're not keeping in contact with the literature and not aware of of best practices. And I talk a little bit about ways to overcome those in my book. I mean, obviously a big part of that is is reading, but I think we need to break down the barriers associated with accessing literature, which is huge. But the part that my book is really focused on is the opposite, which is practitioners who are out there coming up with research questions every day, asking really wonderful questions and answering them and doing so in the context of their clinical practice. But that population could really be informing the literature and help to resolve that research practice gap in a way that is informed by what clients are experiencing and what issues that they have. So that's really what the book is about, that sort of second part of the gap and how practitioners can contribute back to the research literature.

Mary: Sure, sounds good. So when I was reading your book, there was a reference to a research study you had published on manding for information. And I know you have lots of publications like how many peer reviewed journal articles have you published? Do you know?

Dr. Valentino’s Publications:

Dr. Valentino: Oh gosh, I haven't looked in a while. It's probably somewhere in the 30 40 range. It's not. It's not huge. It's it's it's the, I would say, doublings of a busy, busy practitioner. But yeah, I've managed to stay pretty productive over the years.

Mary: Awesome. Yeah. Why don't you tell us about the manding for information study? What kind of design, was it? And then...

Dr. Valentino: Sure, absolutely. And I know this is something very near and dear to your heart, and you probably know that the mand for information repertoire is a critical one. It's super, super important for kids to learn it. To me, it's this one of these critical skills that helps the child learn naturally from their environment. Right. So if they're told to do something but they don't know how to do it and they can ask somebody, How do I do that? And then obviously follow the instructions you just you're in a different space, language wise than you are if you don't have that skill.

Mary: And I'm thinking before we explain the study, there's probably a lot of people that don't know what a mand for information please do.

Dr. Valentino: Yeah. Or do you want me to go ahead? Go ahead? Oh yeah, yeah. So a man is just another word for a request. And the most often you heard the hear the word mand associated with those early requests, so juice, candy, cookie. These are all those meaningful things that a person maybe wants in their life. But as that repertoire gets more sophisticated, people can start to request. Ah, man, four different things and one of those things being information, so when we talk about man's information, we're talking about what people might traditionally consider wage questions. So why did you do that? What is that? Where did you go? The thing that makes this a difficult topic of study is that the man is a verbal operant part of language that is controlled by something very unique and that is the motivating operation. And so in order to teach somebody to ask a question, you have to do so under the right conditions. You have to make sure that they're motivated in the demand for information literature. You have to make sure that they're motivated for that information, which is actually conceptually a very difficult thing to do and set up, right. So I have several studies on manding for information, and I will do a shout out to my previous supervisor, Dr. Alex Schillingsberg, who really is at the forefront of this body of literature. She's published a time and in fact, several of my publications are with her as first author in me somewhere else in the line. But the most recent mand for information study that I published was the first one that I'm aware of that taught kids to ask why? So up into that point, we had not had any studies that demonstrated how to teach that. And it makes sense because it's a little bit more complicated to teach somebody to ask why they they have to be motivated for information, but in a very unique way. And so we had a handful of clients in a clinic that needed this as a goal. They had learned other forms of manding for information. And so it was published in the Journal of Civil Behavior a couple of years ago. We did it, set multiple baseline design and looked at just some creativity in the conditions that would enable us to make sure that the kids were asking why under the right conditions, that is when they were motivated to have that answer versus when, when they were not. So yeah, some of those study very applied, though something we would have done even if it weren't a research study. We still need to teach them why, and we still need to do it under the right conditions.

Mary: Yeah, yeah, that's great. And we can put that in the show notes your show notes are going to be at MaryBarbera.com/165. So you can go there, you can send people there. You can watch this video and then look at all the show notes, which is great. And the one thing I will add is if you're listening and your child is not talking or just requesting with sign language or requesting vocally, just, you know, a handful of things, you're a far way away from teaching. Why? And so we usually get items insight as your first mands, which is kind of combined, as a tact. And then there's bands for actions like open up and those sorts of things. Then there's madns for help mands. Yes and no, which is super complicated. Man's for attention, which is what we consider joint control, which is complicated like you can't prompt. And in my case, Lucas, when he was little, you can't promote mom, look at the cow when he has no, you know, no interest in the cow, no interest in sharing that. So what you can get is a lot of weird language that gets shaped up if you're trying to teach, you know why. For instance, when the child doesn't even have mands for attention appropriately, so you can really get messy language. And as part of my Verbal Behavior Bundle course, I have a whole lesson on how to teach the first three what, where and which. Now they don't have to be the first three, but they tend to be easiest to teach. So I have videos to show people how to do that, but each child is different and their motivations are different. And so you really have to know ABA well to be able to pull off teaching mands for information. And some kids just develop it naturally and then you're great. But for the kids that don't, it's a fine line between teaching rote language and weird language and teaching appropriate language. And it so research studies like you're describing Amber are awesome.

Dr. Valentino: Yeah, it's really interesting when you look back at the mand for information literature, and it wasn't called that. So when you look back historically, I mean, people didn't know they were navigating this and figuring it out, but it very much taught those mands under faulty stimulus control, meaning they would basically change the topography of the mand to get a kid to ask for candy. So it would be like, What is it? And or they hold a piece of candy and he'd say, Tell them, say what is it? And then kid would say, What is it? And they'd give the candy? Right? So in order for that was effective, they would be able to show that it was effective. But they really just taught the kid that what they were holding up was, what is it? That's the new label now instead of candy. So in order to end, you've seen that evolve over the years, but in order to teach it effectively, you have to have something that obviously the child doesn't know what it is and then teach the child to ask. And then that, of course, can lead later to something reinforcing. But that's very much the early studies was just changing the topography of a basic mand to what is it? And it was effective. But as we've evolved, we've changed the way we set up those experiments. Yeah, yeah.

Applied Research:

Mary: Yes. No is also an area that can get messed up very quickly. And I know I I didn't publish a yes no case study, but I did one. I presented one. I have a whole lesson within the verbal behavior bundle on how to teach. Yes, no and I consider myself, you know, pretty expert at teaching. Yes and no. And there's really there's a wide open gap. At least there was last time I logged on on how to teach yes and no. So these are these are all good topics and very much related to the content in my courses, in both of my books. Let's talk before we move on to different kinds of research. I do want to talk about the two peer reviewed journal articles that I published. One is using transfer procedures to teach tacts to a child with autism, and that was. I coauthored that in 2005 with my mentor, Dr. Rick Kubina, now. I also interviewed him on the podcast and we talked about the article so we can link that in the show notes. So we don't have to go in-depth. But you know, I came up with that study idea actually, because Lucas went to a private ABA school for a year and a half. Otherwise, he was in public school his whole life. But he went there and he would have errors when when his therapists to come home and go to school said by Lucas, he would say by Hayley, which was this teacher's name at the time, because she was the only one practicing greetings with her name. And but I knew because I was a new BCBA and I lived and worked with Lucas his whole life that I knew that was a tacting error. Like, he knew all 16 kids in his typical preschool class because we used pictures and quote unquote drilled him with these names. And we also taught him greetings with video modeling. So I knew that he had if he knew the tact, he would have the greeting. So I knew there was a tact error. So I asked the school to send me pictures. They were on a three week break. At the end, he learned all the pictures, all the people's names, and went back and generalized it immediately to greetings. So I called up recombined and I said. Here's a great study, I mean, this is people's names. Greetings, I mean, how functional and applied is this? It's a great site. We should publish it. And he as a researcher, so Mary, you can't just publish stuff like this set up this study. And I had just taken my exam and he's like, We can't publish that, but we can set up a study to publish something to to show he's like, What did you do as the intervention? I'm like, We drilled. And then he really challenged me like, No, what exactly did you do? And it was a mixture of receptive to tact transfers and echoic to tact transfers. But the literature up until that point, there really wasn't any peer reviewed journal articles studies on it. But what there was was Dr. Mark Sundberg, who's also been on a podcast. We can link in the show notes in his Ables book at the time, right? in the big book. I forget what the title of that was, but the main book he talked about teaching everything as echoic to tact transfers, hold up a pen and say, This is a pen. What is it? pen? But Lucas would just zone out. He would echo you and he would zone out. So if it wasn't part receptive? It wasn't going to work for Lucas. He would just zone out, he would never learn it. But if if you combine a touch, Amber, touch Susie Touch and then who's this called Touch Amber, wh's this? Amber. Then he would get it, and I would also use partial echoics. So Rick Kubina to be in to help me set up a study with tax that he didn't know. And we did a multiple baseline. And Jack Michael, Dr. Jack Michael, rest in peace to our grandfather verbal behavior. He was the editor of the analysis, The Verbal Behavior, and I emailed him. He's just like, Where are you? Where did you come from? My mom? Mean lying. Like, you know, it was truly applied Research well, that

Dr. Valentino: That is a beautiful example. What you just described is what I hope every practitioner does, which is I found this really great thing and it worked. And maybe you can't exactly define why it worked and how or how it worked. Or maybe you can. But to go down this path of being able to describe that and demonstrate it, that's huge. And that's a huge contribution. And practitioners are doing this every day. They're doing what you've described every day, but they're just not thinking about it like you were thinking about it and Rick kind of coached you along to say, Let's investigate.

Mary: If I wouldn't have had Rick Kubina and Dr. Jack Michael was like, We are publishing this. And in fact, he sent it to our reviewer and it was late. It was like, I mean, I had no idea when things were due or anything. He's just like, This is really good. And he's like, the reviewer said, no, because, you know, it was a mixture of an echoic. And, you know, I did set a timer and I did have intra observer agreement. So it wasn't like completely, you know, winging it. But I didn't know how much a part of the receptive was important. But I knew. And they also the reviewers, like they didn't know if it was like a Mary/Lucas thing.

Dr. Valentino: Mm-Hmm.

Mary: So he basically Dr. Michael just said in the discussion, You say you don't know how much of this further research is needs to be done splitting out receptive to tact and echoic to tact and a mixture. So what I did was I developed an alternating treatment design and used for different students. And I never published that, but I did present that, and all four of them learned equally as well with the mix procedure. And Lucas only learned that way.

Dr. Valentino: Yeah, that's awesome. And I think that a lot of times practitioners might come into the situation like you did, where there's still a question about what the mechanism of change was or what exactly. And they think, well, I couldn't publish it then. Well, people published studies all the time where they don't know exactly what the mechanism of change was or they can't pinpoint something, exactly, but that's what research is all about. And as long as you can pinpoint that and discussion sections are great for that, you say we did it, but this is not exactly how we set up the study, but the next one should look like this. That's beautiful, and that's acceptable. And that's what research is all about. And in fact, that's really what applied research is all about in and in its truest form, applied research. Really, it's a little bit messy, and that's OK. Yeah.

Mary: Then later, I think it was 2007 or 2008. I was at the ABAI conference and there was analysis of verbal behavior had just come out and people were like, Mary, this this study is quoting your work like this. And I ended up meeting the guy. His name is Dr Chris Flou, and he did his whole doctoral dissertation on transfer procedures using the Barbora and could be in the 2005 study. He's like, I feel like I typed that a zillion times, but there's been multiple studies on transfer procedures. Even I the the is where our prisoners cap. I mean, that was all based on my original study and trying to figure out which transfer procedures work best. So we'll link that in the show notes, you know, sorry to go on it. I feel like I'm I want to get your expertize. But at the same time, how real this need is, and these examples in my world are just so prevalent.

Dr. Valentino: I think it's perfect, and I think it really is exemplifying what I try and talk about in the book that process that you went through. So I'm happy that you went off on a tangent to talk about it a little bit more in depth.

Mary: Well, I want to get into the obstacles one more or actually two more things I'm going to link in, the show notes. One is a qualitative study that I did when I was going for my doctoral dissertation, I did a qualitative research design study, and so I published the experiences of autism mothers who become behavioral analysts, a qualitative study which we can link in the show notes that was 2007. And then in 2011, I published my dissertation. I didn't publish it as an actual study, but we can link that in the show notes as well that time fluency based procedures. But I do want to get into the obstacles for publication, which you have several chapters as well as additional things. But what do you think are the main obstacles for people to publish research or even to do research?

Obstacles for Practitioners Publishing Research:

Dr. Valentino: Yeah, it's a good question. And exactly there's a whole chapter dedicated to this. So in the book, I differentiate between obstacles and barriers, and I consider obstacles to be sort of the things that you need as an individual to address, like how do you overcome these personally and individually? And then barriers I consider to be more institutional right, where you need help from other people to get over that barrier and to overcome it. And so, you know, the obstacles that are I write about in my book and this section, I should note, just as a side sidebar is based on a research study, my colleague, Dr. Jessica Quantico and I published in Behavior Analysis and Practice, which was a survey about this very topic. What are the obstacles and barriers that you face as a practitioner? And so I use that article and that survey data to talk about some of these things in the book. But you know, one of the reported obstacles that people struggle with is lack of knowledge. They're just scared that they don't know enough and that they are going to make a mistake or do something wrong. And so what I try and encourage in the book is for people just to to know that they do have the knowledge by the very basis of you having to be CPA. You have learned this now. You might not be thinking about experimental design in an applied way. You might not be thinking about it in a way that lends itself to a research study right now. But the skills are very easily acquired because you already have the foundation. So I just try and minimize people's fears in that regard like you're it's OK, you're going to be fine, it's going to be OK. And then one other obstacle that comes up a lot and this is much like anything we want to do in life this time. And so people obviously report, that's great. Amber, I love that I don't have the time and so much luck with anything you want to do in life. I usually try and encourage people to realize that they're never going to wake up one day and suddenly have a ton of free time. I think we're all just waiting for the next moment. Well, when I get a new job or I change, I move to a new city or my kid gets a little older, I'll have time. You'll never have that in. So you have to make it. You have to make the time you have to say, I'm going to commit in some way. And maybe that commitment is only 30 minutes or an hour or a week. But that's a commitment and get going. And as I was preparing for this interview, it's interesting. I was looking back at my own research publications and I graphed them like, grab me number of your read publications per year just as a self-monitoring to see how productive I am. And it's funny to look back because the year that was the most productive for me was the year that I was carrying nearly a full caseload. So I was seeing clients. I had no research as part of my job. And so I think about that and I read about that in the book that the times that you feel like you don't have the the time is probably the time when you should start so that you can convince yourself that you can indeed do it. And so the whole book is really geared toward that population. You know, those BCBAs wake up in the morning, they do an observation in a school. They go supervise an r.b.g. They go to a center and they have a meeting. They go back to another school. You know that their days are just packed. They're not sitting in an office all day. And how you can integrate it. And so, so so obstacles of big ideas, time and then some of the institutional barriers, lack of opportunities and then limited access to literature are probably two of the big ones. And I try and recommend ways for people to overcome those. I do recommend being involved in an organization that can support you. So I'm very proud at Trumpet Behavioral Health that we have a lot of supports around this. We have access to literature, free access to literature. We really cultivate a space where people can learn and read and commit to this in a way where you might have to make those. You might have to make those opportunities and get those opportunities yourself. But it's it's very doable.

Mary: Yeah, yeah, that's great. So I think one of the barriers for me is. You know, when you're doing research. People really want to have control and study one little thing like transfer procedures to teach tact, you know, like break it down to one slice, a small slice. And for me, I have a four step approach that I've created over the years based on my my background as a registered nurse, as a mom, as a BCBA, as an advocate, as a researcher with a Ph.D.. And so I want to get the word out to help kids with the whole thing, you know? So it's not even just the time. It's like, I can't slice out one little minuscule thing and I get frustrated when applied research is just not, you know, well, it's too big. It's, you know, even within the transfer study that got published thanks to Rick Kubina and Jack Michael, you know, advocating for it. There's big issues like with my toddler course, for instance, we use, you know, a shoebox, for instance, and then we say Banana, Banana, Banana as we hand the child a picture of a banana that he puts in the box. So if he says nana or banana, it's part mand because he wants the item to put in the box. It's part tact because you can see it is part echoic and its listener responding and attention and everything like that. That is multiple control, there's a lot of variables. You know, we're training online, we have no control over what people are actually doing. But I know my methods work. So it's like, how do we get from massive testimonials and transformation? And people are saying, even within trumpet, you know, I'm sure you have success stories and things that are work, you know? But it's like having the, you know, setting up the study. And, you know, even even, you know, like my example of Lucas tacting the people's names and stuff like that like that actually would have been a more applicable study to names and, you know, to greetings generalizing the greetings. But it's like it's too late. It's already you already made the progress. And there's just so many millions of people that need my stuff that I just not that I've given up on research, but has said it is. It's not just the time, it's like we're in a hurry to help people. And I know in your situation you're the same. So like, do you talk about that in your book?

Dr. Valentino Yeah, that that's a really great analysis. I appreciate that you thought about it and you're right. You know, single subject design in particular has this level of specificity to it that, you know, people are trying to replicate your procedures and determine the exact mechanism for change which has its space and has its importance. And so I think anytime we can do that, particularly when we're doing that with early learners, we should do it. We should demonstrate that and that makes a contribution. But you know, as you were talking, I also started to consider and I talk about this in my book, that he rallies tend to talk to themselves a lot. We tend to publish in our own journals. We tend to speak our own language and there is a space for that and I've done a lot of that in my career. But there's also a lot of different avenues for different types of research, right? And so maybe what you're called to or other practitioners are called to is more outcome kind of studies, right? Or treatment package kind of evaluations. And there's a space for that. It may not be a particular behavior analytical journal. Or maybe it's in a completely different profession altogether, but there's a lot of really great behavior analysts who have sort of expanded their scope and done things that were different, that were bigger outcomes, larger outcomes, evaluating bigger treatment packages. And Pat is a really good example of this right who who wrote the book, the book's forward. A lot of his stuff is more mainstream, and it's out to psychologists and folks that aren't necessarily looking at single subject design as the only way that you can demonstrate something. Or that is a space where you can demonstrate a particular thing, but there are all sorts of avenues. So I would encourage practitioners to certainly do the small, single subject design, demonstrate when you can and when there's that level of specificity involved. But to think outside of the box in terms of audiences and maybe what you're trying to do is evaluate a bigger treatment package and some bigger picture outcomes with lots of kids that there's certainly an audience for that and certainly an outlet for that.

Mary: Yeah, yeah. So one of the obstacles to is is getting things accepted for publication. I know I had pretty good luck with, you know, the two studies that I published without a lot of revisions and that sort of thing, but recently actually Rick Kubina and I also wrote up a case study recently and within a month, I actually we wrote it up about a year ago or over a year ago, and it doesn't have as good of a design. Well, it was retrospective, so it kind of like it happened. What happened was Michelle C., who's in podcast Seventy Eight. We can link that on the show notes, and she's actually her latest update podcast is going to be 164. So one week ago, her updated podcast is going to happen, as well as the publication of a case study with Michelle C's daughter, Elena. And so we can link all that in the show notes. But what happened was Elena was diagnosed with autism in February of 2020 and with mom, who is a high school teacher by training, who just had a second baby, was at home and was trying to get the diagnosis and into ABA quickly. Her daughter was, you know, had two words as she would scream, she would scratch herself open wounds. That's how bad she would tantrum at times. And the world shut down and the world shut down to the point where she got no services, no Zoom services, nothing. And she found my online course. And within thirty three days and part of my online courses, baseline language assessment, you know, writing down. So she actually had an excel sheet with two words in one hour. And then at the end of the course, we say the same thing get a language assessment. And at that point, she had in one hour one hundred eighty words and phrases, prepositions, contractions, miraculous turnaround, which Michelle talks about in podcast 78. And she also then, you know, because she was posting in the group like, Oh my god, I have all this. I'm like, I need to talk to you. So before I hit, I asked her if I could record it and just kind of pretend it was a podcast. I had no idea what she was going to say. And in that podcast, she was talking about how she had a standardized language test from right before the diagnosis at a zero to three month level. You know, one of the lowest the lowest test was zero three months, probably functioning at more of a nine month low level for language. And then right after she took the course, she again got the test. And at that point, Alan was only 26 months old and her standardized speech test, one of them was a high of 30 months. So. That to me, as somebody like I have had this before, where the VB map really correlates with a standardized assessment that matches like a 30 month low level or something. Meanwhile, you know, I don't think we do enough of that where we're pulling in other standardized tests to show progress. And one of the good things about that case study, which we can link in the show notes, is all the variables were gone. Like she didn't have any services. She didn't leave the house. Her mom was the only person. She was just going by the videos. She wasn't even asking for help. Nobody looked at the videos. Nobody gave her any feedback, which can only certainly help. So, you know, at some point, then Rick Kubina and I just decided we're going to publish this as a white paper because we do think it's important to get out there. So is it would you have any advice for practitioners in that situation where, you know, should you just present it, you know, on your own?

Dr. Valentino/b> Yeah, absolutely. You know, I'll send you the reference afterwards. But Gina Green wrote an article around like the two thousand eight time frame where she she published a traditional case study in in traditional kind of psychology research. There is such a thing as a case study that is not single subject design per se, but is a very detailed and documented history of somebody who's hit somebody's diagnosis, their symptoms, and then a very detailed description of the intervention that took place. And so what you just described to me was a traditional case study that absolutely could be published. And the really great thing about Gina Green's paper is she talks about how these case studies are very important for people to publish. Because, as you probably know, one of the criticisms of ABA is there haven't been any large scale, randomized clinical controlled trials of ABA, and managed care companies are starting to highlight this and talk about it. And her point, and this was beyond, you know, this is before that the discussions that we're having today. But was the more of these case studies that we can publish, the more we can demonstrate the effectiveness of our intervention. And that has been historically how interventions have been demonstrated to be effective is with these single case studies. So I absolutely think there's an avenue for that. And again, it takes thinking outside of the ABA world and the traditional publications outlets and exploring where people might have published something very similar. And so there's that. And then I also really encourage practitioners to not always see publication as the end goal, at least in its traditional form, and that there's all sorts of ways to disseminate information, you know, white paper that you just described is beautiful newsletters and presenting at conferences and sharing information that way. And so with dissemination and sharing is really at the heart of your motivation. That doesn't always have to be in the form of a peer reviewed publication. You can look at these other ways to contribute to the field, the profession and the literature. It may not always fit that perfect experimental control box, and those are absolutely valuable, and they mean something to somebody and to the right audience are going to absolutely have an impact them and let you share that example.

Mary: Yeah. And when you said about, you know, you published a survey results, you know, I'd love to link that in the show notes as well because, you know, I have a free potty guide, for instance, which is 20 pages. And there really isn't the literature that there needs to be on potty training, especially kids with autism. And so I was looking at that the other day. We can link that in the show notes, and I had done a survey in 2013, which is highlighted in the potty guide. And it shows that, you know, typically developing kids are potty trained by three a usually and definitely by four and only 50 percent of kids with autism are were potty trained. I mean, this is like 300 people in 2013, but I'm thinking, you know, now with my audience, I mean, I could do surveys all day long. And that's the other thing is you can also partner with agencies or schools or, you know, I might even in the future, open up a whole research arm of my turn autism around courses and community. I'm very open to people taking anything and researching it because I know the interventions work and maybe some of them don't. Maybe some of them need to be tweaked. I'm sure that with coaching on top of the online, we could make massive improvements. But you know, I think one of the great things about you, Amber, is like presenting publication doesn't have to be the goal. We just want to get the best procedures out to the world as quickly as possible. And I think you are an example to show that we can collaborate, we can work together to, you know, really make the world a better place.

Dr. Valentino: Thank you so much, you and I. I think what you just described is the other piece of advice I would give practitioners is to not only think about different outlets, but think about different ways. So survey studies are beautiful, especially. We don't know a lot about a topic. So I published a little bit in the supervision space and a lot of my my studies have been a surprise because we don't know a whole lot about supervision and behavior analysis. And so that's a great way to get some meat under a topic that will probably facilitate single subject research later down the line and get things going. But survey studies are beautiful. There's also different outlets, too, like literature reviews and recommended practice papers. Then there's different ways to contribute that don't always involve these manipulations of a variable with one particular client which has its base, and I've done a fair share of. But if you open up the possibilities to these both those different types of writing and different types of contributions, and then you open up to outside of the behavioral analytic world. You don't have to force yourself into something you aren't interested in or doesn't work for the work you're doing. You can take what you're doing. You just have to find the right audience and the right outlet in the right way to do it. And that's really what I want practitioners to do. And at the heart of the book, I really try and help them through.

More on Dr. Amber Valentino:

Mary: Cool. So the book is called Apply Behavior Analysis Research Made Easy. It's available on Amazon and home. How can people follow your work?

Dr. Valentino: Oh goodness, I do have a LinkedIn page, so that's probably the best place to find me and trumpet behavioral health, TBH.com, constantly talking about the work that we're doing and trying to disseminate and share the excellent clinical work that we're doing. So that's my that's my home, that's my work home trumpet. So you certainly can find me there.

Mary: Awesome. Well, we will put a bunch of these documents in the show notes. I think it'll be a really valuable resource for for practitioners, especially and even for parents. Before I let you go, I'd like to end with a question. You know, part of my podcast goals is is not to just help the kids, but also help the parents and practitioners listening be less stressed and lead happier lives. So do you have any self-care tips or stress management tools that you use?

Dr. Valentino: I do, so I will recommend a book, not a behavioral analytic book. It's called Essentialism, and it's by an author named Greg McCowan. I can send you the details if you want to put it in the notes. I have that book. Yeah, you have the book. So I read that book right before I became a mom, and it really helped me narrow the things in my life down to what was critically important. And I think in this profession, it's so easy to do a lot and those things are important and they're good. But there there comes a point in your life, and maybe you're not a behavior analyst. If you're somebody in another profession or doing something else where you have to look at your life and you have to say, Am I doing the most important and meaningful things in my life and the things that don't really fit with my mission statement for my life have to go, and I'll I'll never forget the day. The first day I said, notice somebody who asked me to volunteer for something and I was shaking like, Oh my gosh, what's going to happen? They were fine with it. I recommended some somebody else and it was fine. And so self-care tip is to don't do things that aren't essential to your life, do the things that are meaningful for you, that are important to you and get rid of the other stuff. And that's how you get. There's no more extra time in the day, but that's how you'll get more time to focus on the things that you really care about. But I think a lot of times we just don't. We don't think to do that, but we should read that book if you have it, and I'm glad you have it too. It's a really great one. Yeah.

Mary: All right. Well, it's been an absolute pleasure talking to you. Dr. Amber Valentino and this will be podcast number 165. So thanks so much for your time.

Dr. Valentino: Yes, thank you. It was a joy.

Mary: If you're a parent or an autism professional and enjoy listening to this podcast, you have to come check out my online course and community where we take all of this material and we apply it. You'll learn life changing strategies to get your child or clients to reach their fullest potential. Join me for a free online workshop at MaryBarbera.com/workshop, where you can learn how to avoid common mistakes. You can see videos of me working with kids with and without autism. And you can learn more about joining my online course and community at a very special discount. Once again, go to MaryBarbera.com/workshop. For all the details, I hope to see you there.

Sign up to receive email updates

Enter your name and email address below and I'll send you periodic updates about the podcast.

FREE ONLINE WORKSHOP!

Most popular posts.

Enter your first name and email address below to claim your free videos.

Wait! Before you go further, in order to give you the right product to best fit your needs, please tell us more about yourself.

Enter your first name and email address below to claim your free resources.

Enter your first name and email address below to claim your free guide.

Using Single Subject Experimental Designs

What are the Characteristics of Single Subject Experimental Designs?

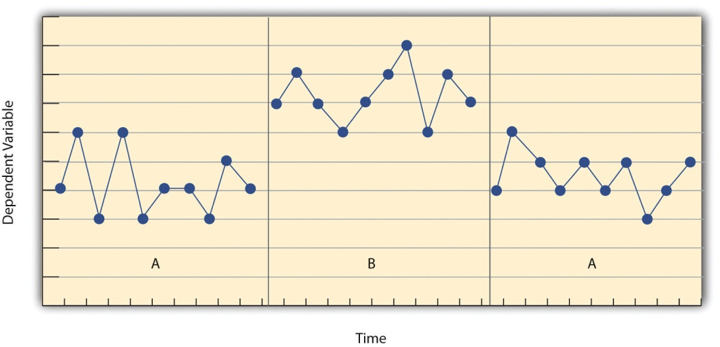

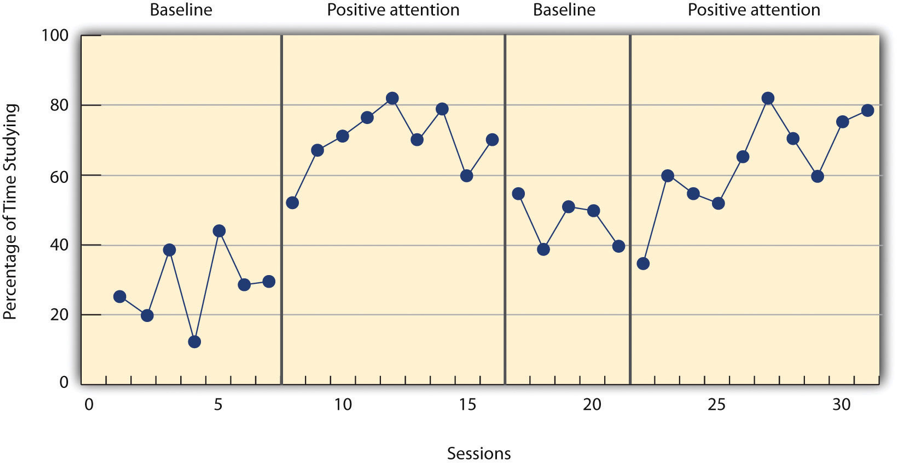

Single-subject designs are the staple of applied behavior analysis research. Those preparing for the BCBA exam or the BCaBA exam must know single subject terms and definitions. When choosing a single-subject experimental design, ABA researchers are looking for certain characteristics that fit their study. First, individuals serve as their own control in single subject research. In other words, the results of each condition are compared to the participant’s own data. If 3 people participate in the study, each will act as their own control. Second, researchers are trying to predict, verify, and replicate the outcomes of their intervention. Prediction, replication, and verification are essential to single-subject design research and help prove experimental control. Prediction: the hypothesis related to what the outcome will be when measured Verification : showing that baseline data would remain consistent if the independent variable was not manipulated Replication: repeating the independent variable manipulation to show similar results across multiple phases Some experimental designs like withdrawal designs are better suited for demonstrating experimental control than others, but each design has its place. We will now look at the different types of single subject experimental designs and the core features of each.

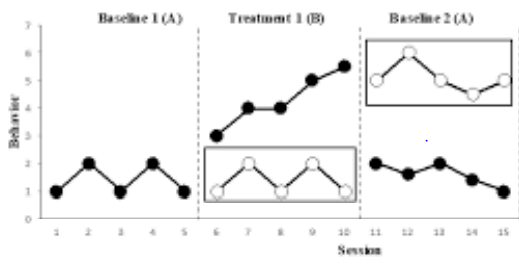

Reversal Design/Withdrawal Design/A-B-A

Arguably the simplest single subject design, the reversal/withdrawal design is excellent at identifying experimental control. First, baseline data is recorded. Then, an intervention is introduced and the effects are recorded. Finally, the intervention is withdrawn and the experiment returns to baseline. The researcher or researchers then visually analyze the changes from baseline to intervention and determine whether or not experimental control was established. Prediction, verification, and replication are also clearly demonstrated in the withdrawal design. Below is a simple example of this A-B-A design.

Advantages: Demonstrate experimental control Disadvantages: Ethical concerns, some behaviors cannot be reversed, not great for high-risk or dangerous behaviors

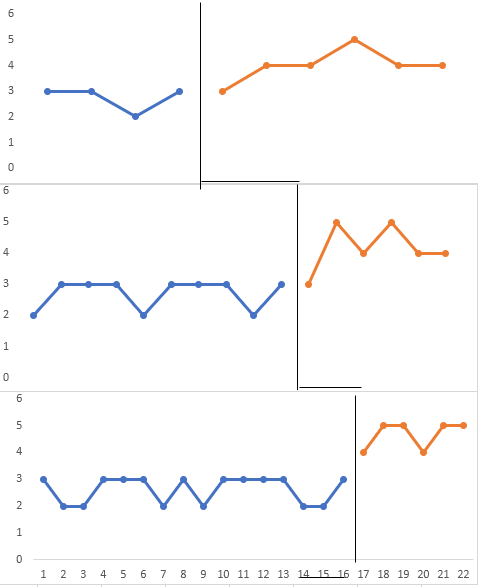

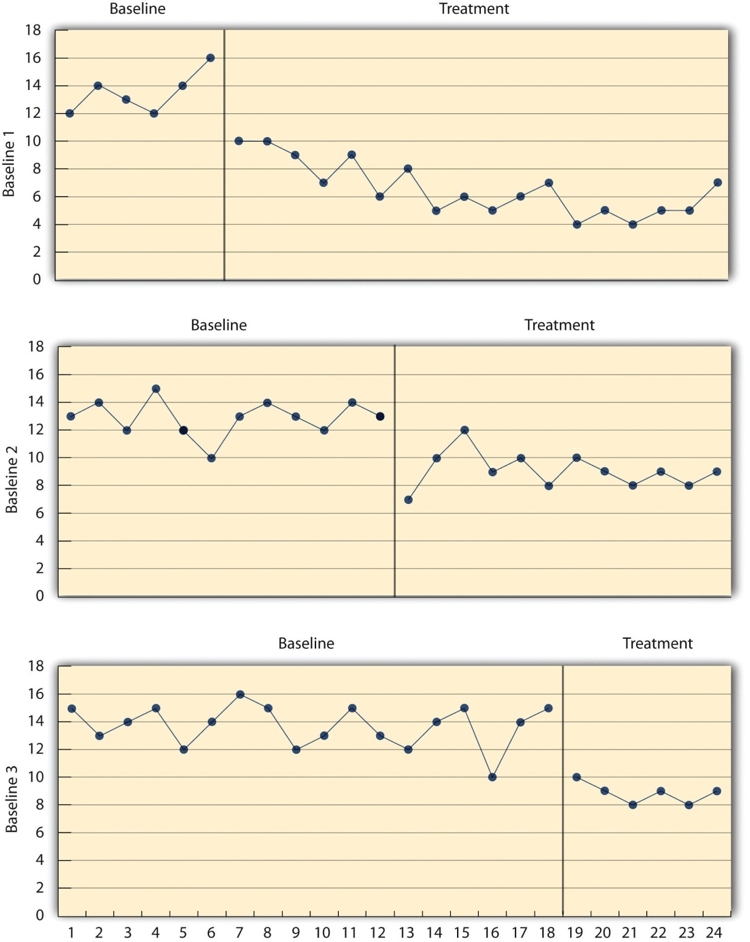

Multiple Baseline Design/Multiple Probe Design

Multiple baseline designs are used when researchers need to measure across participants, behaviors, or settings. For instance, if you wanted to examine the effects of an independent variable in a classroom, in a home setting, and in a clinical setting, you might use a multiple baseline across settings design. Multiple baseline designs typically involve 3-5 subjects, settings, or behaviors. An intervention is introduced into each segment one at a time while baseline continues in the other conditions. Below is a rough example of what a multiple baseline design typically looks like:

Multiple probe designs are identical to multiple baseline designs except baseline is not continuous. Instead, data is taken only sporadically during the baseline condition. You may use this if time and resources are limited, or you do not anticipate baseline changing. Advantages: No withdrawal needed, examine multiple dependent variables at a time Disadvantages : Sometimes difficult to demonstrate experimental control

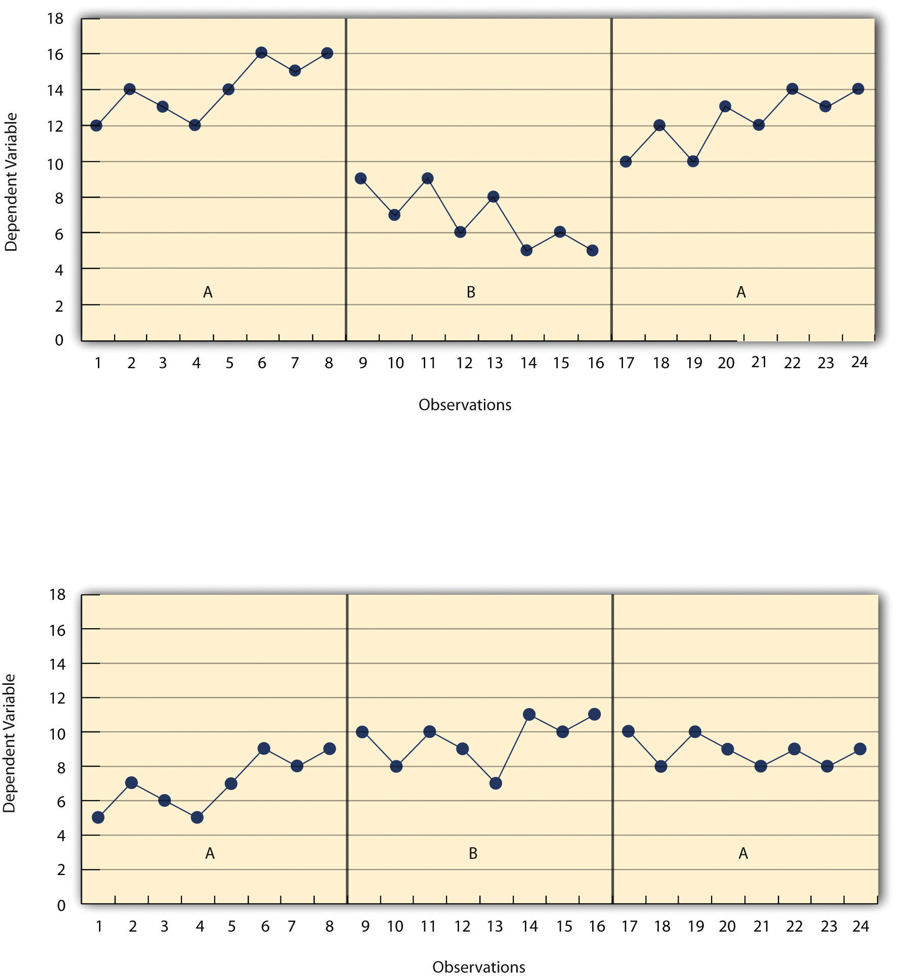

Alternating Treatment Design

The alternating treatment design involves rapid/semirandom alternating conditions taking place all in the same phase. There are equal opportunities for conditions to be present during measurement. Conditions are alternated rapidly and randomly to test multiple conditions at once.

Advantages: No withdrawal, multiple independent variables can be tried rapidly Disadvantages : The multiple treatment effect can impact measurement

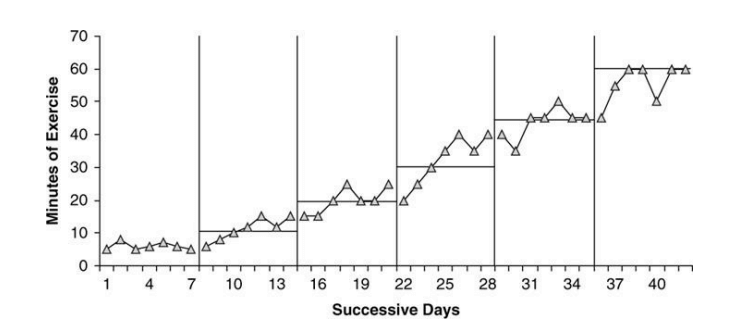

Changing Criterion Design

The changing criterion design is great for reducing or increasing behaviors. The behavior should already be in the subject’s repertoire when using changing criterion designs. Reducing smoking or increasing exercise are two common examples of the changing criterion design. With the changing criterion design, treatment is delivered in a series of ascending or descending phases. The criterion that the subject is expected to meet is changed for each phase. You can reverse a phase of a changing criterion design in an attempt to demonstrate experimental control.

Summary of Single Subject Experimental Designs

Single subject designs are popular in both social sciences and in applied behavior analysis. As always, your research question and purpose should dictate your design choice. You will need to know experimental design and the details behind single subject design for the BCBA exam and the BCaBA exam. For BCBA exam study materials check out our BCBA exam prep. For a full breakdown of the BCBA fifth edition task list, check out our YouTube :

- USF Research

- USF Libraries

Digital Commons @ USF > College of Behavioral and Community Sciences > Child and Family Studies > Applied Behavior Analysis > Theses and Dissertations

Applied Behavior Analysis Theses and Dissertations

Theses/dissertations from 2009 2009.

It is Time to Play! Peer Implemented Pivotal Response Training with a Child with Autism during Recess , Leigh Anne Sams

Theses/Dissertations from 2008 2008

The Evaluation of a Commercially-Available Abduction Prevention Program , Kimberly V. Beck

Expert Video Modeling with Video Feedback to Enhance Gymnastics Skills , Eva Boyer

Behavior Contracting with Dependent Runaway Youth , Jessica Colon

Can Using One Trainer Solely to Deliver Prompts and Feedback During Role Plays Increase Correct Performance of Parenting Skills in a Behavioral Parent Training Program? , Michael M. Cripe

Evaluation of a Functional Treatment for Binge Eating Associated with Bulimia Nervosa , Tamela Cheri DeWeese-Giddings

Teaching Functional Skills to Individuals with Developmental Disabilities Using Video Prompting , Julie A. Horn

Evaluation of a Standardized Protocol for Parent Training in Positive Behavior Support Using a Multiple Baseline Design , Robin Lane

Publicly Posted Feedback with Goal Setting to Improve Tennis Performance , Gretchen Mathews

Improving Staff Performance by Enhancing Staff Training Procedures and Organizational Behavior Management Procedures , Dennis Martin McClelland Jr.

Supporting Teachers and Children During In-Class Transitions: The Power of Prevention , Sarah M. Mele

Effects of Supervisor’s Presence on Staff Response to Tactile Prompts and Self-Monitoring in a Group Home Setting , Judy M. Mowery

Social Skills Training with Typically Developing Adolescents: Measurement of Skill Acquisition , Jessica Anne Thompson

Theses/Dissertations from 2007 2007

Evaluating the effects of a reinforcement system for students participating in the Fast Forword language program , Catherine C. Wilcox

Theses/Dissertations from 2006 2006

The Acquisition of Functional Sign Language by Non-Hearing Impaired Infants , Kerri Haley-Garrett

Response Cards in the Elementary School Classroom: Effects on Student and Teacher Behavior , Shannon McKallip-Moss

The Effects of a Parent Training Course on Coercive Interactions Between Parents and Children , Lezlee Powell