Research report guide: Definition, types, and tips

Last updated

5 March 2024

Reviewed by

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

From successful product launches or software releases to planning major business decisions, research reports serve many vital functions. They can summarize evidence and deliver insights and recommendations to save companies time and resources. They can reveal the most value-adding actions a company should take.

However, poorly constructed reports can have the opposite effect! Taking the time to learn established research-reporting rules and approaches will equip you with in-demand skills. You’ll be able to capture and communicate information applicable to numerous situations and industries, adding another string to your resume bow.

- What are research reports?

A research report is a collection of contextual data, gathered through organized research, that provides new insights into a particular challenge (which, for this article, is business-related). Research reports are a time-tested method for distilling large amounts of data into a narrow band of focus.

Their effectiveness often hinges on whether the report provides:

Strong, well-researched evidence

Comprehensive analysis

Well-considered conclusions and recommendations

Though the topic possibilities are endless, an effective research report keeps a laser-like focus on the specific questions or objectives the researcher believes are key to achieving success. Many research reports begin as research proposals, which usually include the need for a report to capture the findings of the study and recommend a course of action.

A description of the research method used, e.g., qualitative, quantitative, or other

Statistical analysis

Causal (or explanatory) research (i.e., research identifying relationships between two variables)

Inductive research, also known as ‘theory-building’

Deductive research, such as that used to test theories

Action research, where the research is actively used to drive change

- Importance of a research report

Research reports can unify and direct a company's focus toward the most appropriate strategic action. Of course, spending resources on a report takes up some of the company's human and financial resources. Choosing when a report is called for is a matter of judgment and experience.

Some development models used heavily in the engineering world, such as Waterfall development, are notorious for over-relying on research reports. With Waterfall development, there is a linear progression through each step of a project, and each stage is precisely documented and reported on before moving to the next.

The pace of the business world is faster than the speed at which your authors can produce and disseminate reports. So how do companies strike the right balance between creating and acting on research reports?

The answer lies, again, in the report's defined objectives. By paring down your most pressing interests and those of your stakeholders, your research and reporting skills will be the lenses that keep your company's priorities in constant focus.

Honing your company's primary objectives can save significant amounts of time and align research and reporting efforts with ever-greater precision.

Some examples of well-designed research objectives are:

Proving whether or not a product or service meets customer expectations

Demonstrating the value of a service, product, or business process to your stakeholders and investors

Improving business decision-making when faced with a lack of time or other constraints

Clarifying the relationship between a critical cause and effect for problematic business processes

Prioritizing the development of a backlog of products or product features

Comparing business or production strategies

Evaluating past decisions and predicting future outcomes

- Features of a research report

Research reports generally require a research design phase, where the report author(s) determine the most important elements the report must contain.

Just as there are various kinds of research, there are many types of reports.

Here are the standard elements of almost any research-reporting format:

Report summary. A broad but comprehensive overview of what readers will learn in the full report. Summaries are usually no more than one or two paragraphs and address all key elements of the report. Think of the key takeaways your primary stakeholders will want to know if they don’t have time to read the full document.

Introduction. Include a brief background of the topic, the type of research, and the research sample. Consider the primary goal of the report, who is most affected, and how far along the company is in meeting its objectives.

Methods. A description of how the researcher carried out data collection, analysis, and final interpretations of the data. Include the reasons for choosing a particular method. The methods section should strike a balance between clearly presenting the approach taken to gather data and discussing how it is designed to achieve the report's objectives.

Data analysis. This section contains interpretations that lead readers through the results relevant to the report's thesis. If there were unexpected results, include here a discussion on why that might be. Charts, calculations, statistics, and other supporting information also belong here (or, if lengthy, as an appendix). This should be the most detailed section of the research report, with references for further study. Present the information in a logical order, whether chronologically or in order of importance to the report's objectives.

Conclusion. This should be written with sound reasoning, often containing useful recommendations. The conclusion must be backed by a continuous thread of logic throughout the report.

- How to write a research paper

With a clear outline and robust pool of research, a research paper can start to write itself, but what's a good way to start a research report?

Research report examples are often the quickest way to gain inspiration for your report. Look for the types of research reports most relevant to your industry and consider which makes the most sense for your data and goals.

The research report outline will help you organize the elements of your report. One of the most time-tested report outlines is the IMRaD structure:

Introduction

...and Discussion

Pay close attention to the most well-established research reporting format in your industry, and consider your tone and language from your audience's perspective. Learn the key terms inside and out; incorrect jargon could easily harm the perceived authority of your research paper.

Along with a foundation in high-quality research and razor-sharp analysis, the most effective research reports will also demonstrate well-developed:

Internal logic

Narrative flow

Conclusions and recommendations

Readability, striking a balance between simple phrasing and technical insight

How to gather research data for your report

The validity of research data is critical. Because the research phase usually occurs well before the writing phase, you normally have plenty of time to vet your data.

However, research reports could involve ongoing research, where report authors (sometimes the researchers themselves) write portions of the report alongside ongoing research.

One such research-report example would be an R&D department that knows its primary stakeholders are eager to learn about a lengthy work in progress and any potentially important outcomes.

However you choose to manage the research and reporting, your data must meet robust quality standards before you can rely on it. Vet any research with the following questions in mind:

Does it use statistically valid analysis methods?

Do the researchers clearly explain their research, analysis, and sampling methods?

Did the researchers provide any caveats or advice on how to interpret their data?

Have you gathered the data yourself or were you in close contact with those who did?

Is the source biased?

Usually, flawed research methods become more apparent the further you get through a research report.

It's perfectly natural for good research to raise new questions, but the reader should have no uncertainty about what the data represents. There should be no doubt about matters such as:

Whether the sampling or analysis methods were based on sound and consistent logic

What the research samples are and where they came from

The accuracy of any statistical functions or equations

Validation of testing and measuring processes

When does a report require design validation?

A robust design validation process is often a gold standard in highly technical research reports. Design validation ensures the objects of a study are measured accurately, which lends more weight to your report and makes it valuable to more specialized industries.

Product development and engineering projects are the most common research-report examples that typically involve a design validation process. Depending on the scope and complexity of your research, you might face additional steps to validate your data and research procedures.

If you’re including design validation in the report (or report proposal), explain and justify your data-collection processes. Good design validation builds greater trust in a research report and lends more weight to its conclusions.

Choosing the right analysis method

Just as the quality of your report depends on properly validated research, a useful conclusion requires the most contextually relevant analysis method. This means comparing different statistical methods and choosing the one that makes the most sense for your research.

Most broadly, research analysis comes down to quantitative or qualitative methods (respectively: measurable by a number vs subjectively qualified values). There are also mixed research methods, which bridge the need for merging hard data with qualified assessments and still reach a cohesive set of conclusions.

Some of the most common analysis methods in research reports include:

Significance testing (aka hypothesis analysis), which compares test and control groups to determine how likely the data was the result of random chance.

Regression analysis , to establish relationships between variables, control for extraneous variables , and support correlation analysis.

Correlation analysis (aka bivariate testing), a method to identify and determine the strength of linear relationships between variables. It’s effective for detecting patterns from complex data, but care must be exercised to not confuse correlation with causation.

With any analysis method, it's important to justify which method you chose in the report. You should also provide estimates of the statistical accuracy (e.g., the p-value or confidence level of quantifiable data) of any data analysis.

This requires a commitment to the report's primary aim. For instance, this may be achieving a certain level of customer satisfaction by analyzing the cause and effect of changes to how service is delivered. Even better, use statistical analysis to calculate which change is most positively correlated with improved levels of customer satisfaction.

- Tips for writing research reports

There's endless good advice for writing effective research reports, and it almost all depends on the subjective aims of the people behind the report. Due to the wide variety of research reports, the best tips will be unique to each author's purpose.

Consider the following research report tips in any order, and take note of the ones most relevant to you:

No matter how in depth or detailed your report might be, provide a well-considered, succinct summary. At the very least, give your readers a quick and effective way to get up to speed.

Pare down your target audience (e.g., other researchers, employees, laypersons, etc.), and adjust your voice for their background knowledge and interest levels

For all but the most open-ended research, clarify your objectives, both for yourself and within the report.

Leverage your team members’ talents to fill in any knowledge gaps you might have. Your team is only as good as the sum of its parts.

Justify why your research proposal’s topic will endure long enough to derive value from the finished report.

Consolidate all research and analysis functions onto a single user-friendly platform. There's no reason to settle for less than developer-grade tools suitable for non-developers.

What's the format of a research report?

The research-reporting format is how the report is structured—a framework the authors use to organize their data, conclusions, arguments, and recommendations. The format heavily determines how the report's outline develops, because the format dictates the overall structure and order of information (based on the report's goals and research objectives).

What's the purpose of a research-report outline?

A good report outline gives form and substance to the report's objectives, presenting the results in a readable, engaging way. For any research-report format, the outline should create momentum along a chain of logic that builds up to a conclusion or interpretation.

What's the difference between a research essay and a research report?

There are several key differences between research reports and essays:

Research report:

Ordered into separate sections

More commercial in nature

Often includes infographics

Heavily descriptive

More self-referential

Usually provides recommendations

Research essay

Does not rely on research report formatting

More academically minded

Normally text-only

Less detailed

Omits discussion of methods

Usually non-prescriptive

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 6 February 2023

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 April 2023

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Research Report: Definition, Types + [Writing Guide]

One of the reasons for carrying out research is to add to the existing body of knowledge. Therefore, when conducting research, you need to document your processes and findings in a research report.

With a research report, it is easy to outline the findings of your systematic investigation and any gaps needing further inquiry. Knowing how to create a detailed research report will prove useful when you need to conduct research.

What is a Research Report?

A research report is a well-crafted document that outlines the processes, data, and findings of a systematic investigation. It is an important document that serves as a first-hand account of the research process, and it is typically considered an objective and accurate source of information.

In many ways, a research report can be considered as a summary of the research process that clearly highlights findings, recommendations, and other important details. Reading a well-written research report should provide you with all the information you need about the core areas of the research process.

Features of a Research Report

So how do you recognize a research report when you see one? Here are some of the basic features that define a research report.

- It is a detailed presentation of research processes and findings, and it usually includes tables and graphs.

- It is written in a formal language.

- A research report is usually written in the third person.

- It is informative and based on first-hand verifiable information.

- It is formally structured with headings, sections, and bullet points.

- It always includes recommendations for future actions.

Types of Research Report

The research report is classified based on two things; nature of research and target audience.

Nature of Research

- Qualitative Research Report

This is the type of report written for qualitative research . It outlines the methods, processes, and findings of a qualitative method of systematic investigation. In educational research, a qualitative research report provides an opportunity for one to apply his or her knowledge and develop skills in planning and executing qualitative research projects.

A qualitative research report is usually descriptive in nature. Hence, in addition to presenting details of the research process, you must also create a descriptive narrative of the information.

- Quantitative Research Report

A quantitative research report is a type of research report that is written for quantitative research. Quantitative research is a type of systematic investigation that pays attention to numerical or statistical values in a bid to find answers to research questions.

In this type of research report, the researcher presents quantitative data to support the research process and findings. Unlike a qualitative research report that is mainly descriptive, a quantitative research report works with numbers; that is, it is numerical in nature.

Target Audience

Also, a research report can be said to be technical or popular based on the target audience. If you’re dealing with a general audience, you would need to present a popular research report, and if you’re dealing with a specialized audience, you would submit a technical report.

- Technical Research Report

A technical research report is a detailed document that you present after carrying out industry-based research. This report is highly specialized because it provides information for a technical audience; that is, individuals with above-average knowledge in the field of study.

In a technical research report, the researcher is expected to provide specific information about the research process, including statistical analyses and sampling methods. Also, the use of language is highly specialized and filled with jargon.

Examples of technical research reports include legal and medical research reports.

- Popular Research Report

A popular research report is one for a general audience; that is, for individuals who do not necessarily have any knowledge in the field of study. A popular research report aims to make information accessible to everyone.

It is written in very simple language, which makes it easy to understand the findings and recommendations. Examples of popular research reports are the information contained in newspapers and magazines.

Importance of a Research Report

- Knowledge Transfer: As already stated above, one of the reasons for carrying out research is to contribute to the existing body of knowledge, and this is made possible with a research report. A research report serves as a means to effectively communicate the findings of a systematic investigation to all and sundry.

- Identification of Knowledge Gaps: With a research report, you’d be able to identify knowledge gaps for further inquiry. A research report shows what has been done while hinting at other areas needing systematic investigation.

- In market research, a research report would help you understand the market needs and peculiarities at a glance.

- A research report allows you to present information in a precise and concise manner.

- It is time-efficient and practical because, in a research report, you do not have to spend time detailing the findings of your research work in person. You can easily send out the report via email and have stakeholders look at it.

Guide to Writing a Research Report

A lot of detail goes into writing a research report, and getting familiar with the different requirements would help you create the ideal research report. A research report is usually broken down into multiple sections, which allows for a concise presentation of information.

Structure and Example of a Research Report

This is the title of your systematic investigation. Your title should be concise and point to the aims, objectives, and findings of a research report.

- Table of Contents

This is like a compass that makes it easier for readers to navigate the research report.

An abstract is an overview that highlights all important aspects of the research including the research method, data collection process, and research findings. Think of an abstract as a summary of your research report that presents pertinent information in a concise manner.

An abstract is always brief; typically 100-150 words and goes straight to the point. The focus of your research abstract should be the 5Ws and 1H format – What, Where, Why, When, Who and How.

- Introduction

Here, the researcher highlights the aims and objectives of the systematic investigation as well as the problem which the systematic investigation sets out to solve. When writing the report introduction, it is also essential to indicate whether the purposes of the research were achieved or would require more work.

In the introduction section, the researcher specifies the research problem and also outlines the significance of the systematic investigation. Also, the researcher is expected to outline any jargons and terminologies that are contained in the research.

- Literature Review

A literature review is a written survey of existing knowledge in the field of study. In other words, it is the section where you provide an overview and analysis of different research works that are relevant to your systematic investigation.

It highlights existing research knowledge and areas needing further investigation, which your research has sought to fill. At this stage, you can also hint at your research hypothesis and its possible implications for the existing body of knowledge in your field of study.

- An Account of Investigation

This is a detailed account of the research process, including the methodology, sample, and research subjects. Here, you are expected to provide in-depth information on the research process including the data collection and analysis procedures.

In a quantitative research report, you’d need to provide information surveys, questionnaires and other quantitative data collection methods used in your research. In a qualitative research report, you are expected to describe the qualitative data collection methods used in your research including interviews and focus groups.

In this section, you are expected to present the results of the systematic investigation.

This section further explains the findings of the research, earlier outlined. Here, you are expected to present a justification for each outcome and show whether the results are in line with your hypotheses or if other research studies have come up with similar results.

- Conclusions

This is a summary of all the information in the report. It also outlines the significance of the entire study.

- References and Appendices

This section contains a list of all the primary and secondary research sources.

Tips for Writing a Research Report

- Define the Context for the Report

As is obtainable when writing an essay, defining the context for your research report would help you create a detailed yet concise document. This is why you need to create an outline before writing so that you do not miss out on anything.

- Define your Audience

Writing with your audience in mind is essential as it determines the tone of the report. If you’re writing for a general audience, you would want to present the information in a simple and relatable manner. For a specialized audience, you would need to make use of technical and field-specific terms.

- Include Significant Findings

The idea of a research report is to present some sort of abridged version of your systematic investigation. In your report, you should exclude irrelevant information while highlighting only important data and findings.

- Include Illustrations

Your research report should include illustrations and other visual representations of your data. Graphs, pie charts, and relevant images lend additional credibility to your systematic investigation.

- Choose the Right Title

A good research report title is brief, precise, and contains keywords from your research. It should provide a clear idea of your systematic investigation so that readers can grasp the entire focus of your research from the title.

- Proofread the Report

Before publishing the document, ensure that you give it a second look to authenticate the information. If you can, get someone else to go through the report, too, and you can also run it through proofreading and editing software.

How to Gather Research Data for Your Report

- Understand the Problem

Every research aims at solving a specific problem or set of problems, and this should be at the back of your mind when writing your research report. Understanding the problem would help you to filter the information you have and include only important data in your report.

- Know what your report seeks to achieve

This is somewhat similar to the point above because, in some way, the aim of your research report is intertwined with the objectives of your systematic investigation. Identifying the primary purpose of writing a research report would help you to identify and present the required information accordingly.

- Identify your audience

Knowing your target audience plays a crucial role in data collection for a research report. If your research report is specifically for an organization, you would want to present industry-specific information or show how the research findings are relevant to the work that the company does.

- Create Surveys/Questionnaires

A survey is a research method that is used to gather data from a specific group of people through a set of questions. It can be either quantitative or qualitative.

A survey is usually made up of structured questions, and it can be administered online or offline. However, an online survey is a more effective method of research data collection because it helps you save time and gather data with ease.

You can seamlessly create an online questionnaire for your research on Formplus . With the multiple sharing options available in the builder, you would be able to administer your survey to respondents in little or no time.

Formplus also has a report summary too l that you can use to create custom visual reports for your research.

Step-by-step guide on how to create an online questionnaire using Formplus

- Sign into Formplus

In the Formplus builder, you can easily create different online questionnaires for your research by dragging and dropping preferred fields into your form. To access the Formplus builder, you will need to create an account on Formplus.

Once you do this, sign in to your account and click on Create new form to begin.

- Edit Form Title : Click on the field provided to input your form title, for example, “Research Questionnaire.”

- Edit Form : Click on the edit icon to edit the form.

- Add Fields : Drag and drop preferred form fields into your form in the Formplus builder inputs column. There are several field input options for questionnaires in the Formplus builder.

- Edit fields

- Click on “Save”

- Form Customization: With the form customization options in the form builder, you can easily change the outlook of your form and make it more unique and personalized. Formplus allows you to change your form theme, add background images, and even change the font according to your needs.

- Multiple Sharing Options: Formplus offers various form-sharing options, which enables you to share your questionnaire with respondents easily. You can use the direct social media sharing buttons to share your form link to your organization’s social media pages. You can also send out your survey form as email invitations to your research subjects too. If you wish, you can share your form’s QR code or embed it on your organization’s website for easy access.

Conclusion

Always remember that a research report is just as important as the actual systematic investigation because it plays a vital role in communicating research findings to everyone else. This is why you must take care to create a concise document summarizing the process of conducting any research.

In this article, we’ve outlined essential tips to help you create a research report. When writing your report, you should always have the audience at the back of your mind, as this would set the tone for the document.

Connect to Formplus, Get Started Now - It's Free!

- ethnographic research survey

- research report

- research report survey

- busayo.longe

You may also like:

Assessment Tools: Types, Examples & Importance

In this article, you’ll learn about different assessment tools to help you evaluate performance in various contexts

How to Write a Problem Statement for your Research

Learn how to write problem statements before commencing any research effort. Learn about its structure and explore examples

21 Chrome Extensions for Academic Researchers in 2022

In this article, we will discuss a number of chrome extensions you can use to make your research process even seamless

Ethnographic Research: Types, Methods + [Question Examples]

Simple guide on ethnographic research, it types, methods, examples and advantages. Also highlights how to conduct an ethnographic...

Formplus - For Seamless Data Collection

Collect data the right way with a versatile data collection tool. try formplus and transform your work productivity today..

- Academic Skills

- Reading, writing and referencing

Research reports

This resource will help you identify the common elements and basic format of a research report.

Research reports generally follow a similar structure and have common elements, each with a particular purpose. Learn more about each of these elements below.

Common elements of reports

Your title should be brief, topic-specific, and informative, clearly indicating the purpose and scope of your study. Include key words in your title so that search engines can easily access your work. For example: Measurement of water around Station Pier.

An abstract is a concise summary that helps readers to quickly assess the content and direction of your paper. It should be brief, written in a single paragraph and cover: the scope and purpose of your report; an overview of methodology; a summary of the main findings or results; principal conclusions or significance of the findings; and recommendations made.

The information in the abstract must be presented in the same order as it is in your report. The abstract is usually written last when you have developed your arguments and synthesised the results.

The introduction creates the context for your research. It should provide sufficient background to allow the reader to understand and evaluate your study without needing to refer to previous publications. After reading the introduction your reader should understand exactly what your research is about, what you plan to do, why you are undertaking this research and which methods you have used. Introductions generally include:

- The rationale for the present study. Why are you interested in this topic? Why is this topic worth investigating?

- Key terms and definitions.

- An outline of the research questions and hypotheses; the assumptions or propositions that your research will test.

Not all research reports have a separate literature review section. In shorter research reports, the review is usually part of the Introduction.

A literature review is a critical survey of recent relevant research in a particular field. The review should be a selection of carefully organised, focused and relevant literature that develops a narrative ‘story’ about your topic. Your review should answer key questions about the literature:

- What is the current state of knowledge on the topic?

- What differences in approaches / methodologies are there?

- Where are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

- What further research is needed? The review may identify a gap in the literature which provides a rationale for your study and supports your research questions and methodology.

The review is not just a summary of all you have read. Rather, it must develop an argument or a point of view that supports your chosen methodology and research questions.

The purpose of this section is to detail how you conducted your research so that others can understand and replicate your approach.

You need to briefly describe the subjects (if appropriate), any equipment or materials used and the approach taken. If the research method or method of data analysis is commonly used within your field of study, then simply reference the procedure. If, however, your methods are new or controversial then you need to describe them in more detail and provide a rationale for your approach. The methodology is written in the past tense and should be as concise as possible.

This section is a concise, factual summary of your findings, listed under headings appropriate to your research questions. It’s common to use tables and graphics. Raw data or details about the method of statistical analysis used should be included in the Appendices.

Present your results in a consistent manner. For example, if you present the first group of results as percentages, it will be confusing for the reader and difficult to make comparisons of data if later results are presented as fractions or as decimal values.

In general, you won’t discuss your results here. Any analysis of your results usually occurs in the Discussion section.

Notes on visual data representation:

- Graphs and tables may be used to reveal trends in your data, but they must be explained and referred to in adjacent accompanying text.

- Figures and tables do not simply repeat information given in the text: they summarise, amplify or complement it.

- Graphs are always referred to as ‘Figures’, and both axes must be clearly labelled.

- Tables must be numbered, and they must be able to stand-alone or make sense without your reader needing to read all of the accompanying text.

The Discussion responds to the hypothesis or research question. This section is where you interpret your results, account for your findings and explain their significance within the context of other research. Consider the adequacy of your sampling techniques, the scope and long-term implications of your study, any problems with data collection or analysis and any assumptions on which your study was based. This is also the place to discuss any disappointing results and address limitations.

Checklist for the discussion

- To what extent was each hypothesis supported?

- To what extent are your findings validated or supported by other research?

- Were there unexpected variables that affected your results?

- On reflection, was your research method appropriate?

- Can you account for any differences between your results and other studies?

Conclusions in research reports are generally fairly short and should follow on naturally from points raised in the Discussion. In this section you should discuss the significance of your findings. To what extent and in what ways are your findings useful or conclusive? Is further research required? If so, based on your research experience, what suggestions could you make about improvements to the scope or methodology of future studies?

Also, consider the practical implications of your results and any recommendations you could make. For example, if your research is on reading strategies in the primary school classroom, what are the implications of your results for the classroom teacher? What recommendations could you make for teachers?

A Reference List contains all the resources you have cited in your work, while a Bibliography is a wider list containing all the resources you have consulted (but not necessarily cited) in the preparation of your work. It is important to check which of these is required, and the preferred format, style of references and presentation requirements of your own department.

Appendices (singular ‘Appendix’) provide supporting material to your project. Examples of such materials include:

- Relevant letters to participants and organisations (e.g. regarding the ethics or conduct of the project).

- Background reports.

- Detailed calculations.

Different types of data are presented in separate appendices. Each appendix must be titled, labelled with a number or letter, and referred to in the body of the report.

Appendices are placed at the end of a report, and the contents are generally not included in the word count.

Fi nal ti p

While there are many common elements to research reports, it’s always best to double check the exact requirements for your task. You may find that you don’t need some sections, can combine others or have specific requirements about referencing, formatting or word limits.

Looking for one-on-one advice?

Get tailored advice from an Academic Skills Adviser by booking an Individual appointment, or get quick feedback from one of our Academic Writing Mentors via email through our Writing advice service.

Go to Student appointments

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

- QuestionPro

- Solutions Industries Gaming Automotive Sports and events Education Government Travel & Hospitality Financial Services Healthcare Cannabis Technology Use Case AskWhy Communities Audience Contactless surveys Mobile LivePolls Member Experience GDPR Positive People Science 360 Feedback Surveys

- Resources Blog eBooks Survey Templates Case Studies Training Help center

Home Market Research

Research Reports: Definition and How to Write Them

Reports are usually spread across a vast horizon of topics but are focused on communicating information about a particular topic and a niche target market. The primary motive of research reports is to convey integral details about a study for marketers to consider while designing new strategies.

Certain events, facts, and other information based on incidents need to be relayed to the people in charge, and creating research reports is the most effective communication tool. Ideal research reports are extremely accurate in the offered information with a clear objective and conclusion. These reports should have a clean and structured format to relay information effectively.

What are Research Reports?

Research reports are recorded data prepared by researchers or statisticians after analyzing the information gathered by conducting organized research, typically in the form of surveys or qualitative methods .

A research report is a reliable source to recount details about a conducted research. It is most often considered to be a true testimony of all the work done to garner specificities of research.

The various sections of a research report are:

- Background/Introduction

- Implemented Methods

- Results based on Analysis

- Deliberation

Learn more: Quantitative Research

Components of Research Reports

Research is imperative for launching a new product/service or a new feature. The markets today are extremely volatile and competitive due to new entrants every day who may or may not provide effective products. An organization needs to make the right decisions at the right time to be relevant in such a market with updated products that suffice customer demands.

The details of a research report may change with the purpose of research but the main components of a report will remain constant. The research approach of the market researcher also influences the style of writing reports. Here are seven main components of a productive research report:

- Research Report Summary: The entire objective along with the overview of research are to be included in a summary which is a couple of paragraphs in length. All the multiple components of the research are explained in brief under the report summary. It should be interesting enough to capture all the key elements of the report.

- Research Introduction: There always is a primary goal that the researcher is trying to achieve through a report. In the introduction section, he/she can cover answers related to this goal and establish a thesis which will be included to strive and answer it in detail. This section should answer an integral question: “What is the current situation of the goal?”. After the research design was conducted, did the organization conclude the goal successfully or they are still a work in progress – provide such details in the introduction part of the research report.

- Research Methodology: This is the most important section of the report where all the important information lies. The readers can gain data for the topic along with analyzing the quality of provided content and the research can also be approved by other market researchers . Thus, this section needs to be highly informative with each aspect of research discussed in detail. Information needs to be expressed in chronological order according to its priority and importance. Researchers should include references in case they gained information from existing techniques.

- Research Results: A short description of the results along with calculations conducted to achieve the goal will form this section of results. Usually, the exposition after data analysis is carried out in the discussion part of the report.

Learn more: Quantitative Data

- Research Discussion: The results are discussed in extreme detail in this section along with a comparative analysis of reports that could probably exist in the same domain. Any abnormality uncovered during research will be deliberated in the discussion section. While writing research reports, the researcher will have to connect the dots on how the results will be applicable in the real world.

- Research References and Conclusion: Conclude all the research findings along with mentioning each and every author, article or any content piece from where references were taken.

Learn more: Qualitative Observation

15 Tips for Writing Research Reports

Writing research reports in the manner can lead to all the efforts going down the drain. Here are 15 tips for writing impactful research reports:

- Prepare the context before starting to write and start from the basics: This was always taught to us in school – be well-prepared before taking a plunge into new topics. The order of survey questions might not be the ideal or most effective order for writing research reports. The idea is to start with a broader topic and work towards a more specific one and focus on a conclusion or support, which a research should support with the facts. The most difficult thing to do in reporting, without a doubt is to start. Start with the title, the introduction, then document the first discoveries and continue from that. Once the marketers have the information well documented, they can write a general conclusion.

- Keep the target audience in mind while selecting a format that is clear, logical and obvious to them: Will the research reports be presented to decision makers or other researchers? What are the general perceptions around that topic? This requires more care and diligence. A researcher will need a significant amount of information to start writing the research report. Be consistent with the wording, the numbering of the annexes and so on. Follow the approved format of the company for the delivery of research reports and demonstrate the integrity of the project with the objectives of the company.

- Have a clear research objective: A researcher should read the entire proposal again, and make sure that the data they provide contributes to the objectives that were raised from the beginning. Remember that speculations are for conversations, not for research reports, if a researcher speculates, they directly question their own research.

- Establish a working model: Each study must have an internal logic, which will have to be established in the report and in the evidence. The researchers’ worst nightmare is to be required to write research reports and realize that key questions were not included.

Learn more: Quantitative Observation

- Gather all the information about the research topic. Who are the competitors of our customers? Talk to other researchers who have studied the subject of research, know the language of the industry. Misuse of the terms can discourage the readers of research reports from reading further.

- Read aloud while writing. While reading the report, if the researcher hears something inappropriate, for example, if they stumble over the words when reading them, surely the reader will too. If the researcher can’t put an idea in a single sentence, then it is very long and they must change it so that the idea is clear to everyone.

- Check grammar and spelling. Without a doubt, good practices help to understand the report. Use verbs in the present tense. Consider using the present tense, which makes the results sound more immediate. Find new words and other ways of saying things. Have fun with the language whenever possible.

- Discuss only the discoveries that are significant. If some data are not really significant, do not mention them. Remember that not everything is truly important or essential within research reports.

Learn more: Qualitative Data

- Try and stick to the survey questions. For example, do not say that the people surveyed “were worried” about an research issue , when there are different degrees of concern.

- The graphs must be clear enough so that they understand themselves. Do not let graphs lead the reader to make mistakes: give them a title, include the indications, the size of the sample, and the correct wording of the question.

- Be clear with messages. A researcher should always write every section of the report with an accuracy of details and language.

- Be creative with titles – Particularly in segmentation studies choose names “that give life to research”. Such names can survive for a long time after the initial investigation.

- Create an effective conclusion: The conclusion in the research reports is the most difficult to write, but it is an incredible opportunity to excel. Make a precise summary. Sometimes it helps to start the conclusion with something specific, then it describes the most important part of the study, and finally, it provides the implications of the conclusions.

- Get a couple more pair of eyes to read the report. Writers have trouble detecting their own mistakes. But they are responsible for what is presented. Ensure it has been approved by colleagues or friends before sending the find draft out.

Learn more: Market Research and Analysis

MORE LIKE THIS

Life@QuestionPro: Thomas Maiwald-Immer’s Experience

Aug 9, 2024

Top 13 Reporting Tools to Transform Your Data Insights & More

Aug 8, 2024

Employee Satisfaction: How to Boost Your Workplace Happiness?

Aug 7, 2024

Jotform vs Formstack: Which Form Builder Should You Choose?

Other categories.

- Academic Research

- Artificial Intelligence

- Assessments

- Brand Awareness

- Case Studies

- Communities

- Consumer Insights

- Customer effort score

- Customer Engagement

- Customer Experience

- Customer Loyalty

- Customer Research

- Customer Satisfaction

- Employee Benefits

- Employee Engagement

- Employee Retention

- Friday Five

- General Data Protection Regulation

- Insights Hub

- Life@QuestionPro

- Market Research

- Mobile diaries

- Mobile Surveys

- New Features

- Online Communities

- Question Types

- Questionnaire

- QuestionPro Products

- Release Notes

- Research Tools and Apps

- Revenue at Risk

- Survey Templates

- Training Tips

- Tuesday CX Thoughts (TCXT)

- Uncategorized

- What’s Coming Up

- Workforce Intelligence

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Section 1- Evidence-based practice (EBP)

Chapter 6: Components of a Research Report

Components of a research report.

Partido, B.B.

Elements of research report

| Introduction | What is the issue? |

| Methods | What methods have been used to investigate the issue? |

| Results | What was found? |

| Discussion | What are the implications of the findings? |

The research report contains four main areas:

- Introduction – What is the issue? What is known? What is not known? What are you trying to find out? This sections ends with the purpose and specific aims of the study.

- Methods – The recipe for the study. If someone wanted to perform the same study, what information would they need? How will you answer your research question? This part usually contains subheadings: Participants, Instruments, Procedures, Data Analysis,

- Results – What was found? This is organized by specific aims and provides the results of the statistical analysis.

- Discussion – How do the results fit in with the existing literature? What were the limitations and areas of future research?

Formalized Curiosity for Knowledge and Innovation Copyright © by partido1. All Rights Reserved.

Uncomplicated Reviews of Educational Research Methods

- Writing a Research Report

.pdf version of this page

This review covers the basic elements of a research report. This is a general guide for what you will see in journal articles or dissertations. This format assumes a mixed methods study, but you can leave out either quantitative or qualitative sections if you only used a single methodology.

This review is divided into sections for easy reference. There are five MAJOR parts of a Research Report:

1. Introduction 2. Review of Literature 3. Methods 4. Results 5. Discussion

As a general guide, the Introduction, Review of Literature, and Methods should be about 1/3 of your paper, Discussion 1/3, then Results 1/3.

Section 1 : Cover Sheet (APA format cover sheet) optional, if required.

Section 2: Abstract (a basic summary of the report, including sample, treatment, design, results, and implications) (≤ 150 words) optional, if required.

Section 3 : Introduction (1-3 paragraphs) • Basic introduction • Supportive statistics (can be from periodicals) • Statement of Purpose • Statement of Significance

Section 4 : Research question(s) or hypotheses • An overall research question (optional) • A quantitative-based (hypotheses) • A qualitative-based (research questions) Note: You will generally have more than one, especially if using hypotheses.

Section 5: Review of Literature ▪ Should be organized by subheadings ▪ Should adequately support your study using supporting, related, and/or refuting evidence ▪ Is a synthesis, not a collection of individual summaries

Section 6: Methods ▪ Procedure: Describe data gathering or participant recruitment, including IRB approval ▪ Sample: Describe the sample or dataset, including basic demographics ▪ Setting: Describe the setting, if applicable (generally only in qualitative designs) ▪ Treatment: If applicable, describe, in detail, how you implemented the treatment ▪ Instrument: Describe, in detail, how you implemented the instrument; Describe the reliability and validity associated with the instrument ▪ Data Analysis: Describe type of procedure (t-test, interviews, etc.) and software (if used)

Section 7: Results ▪ Restate Research Question 1 (Quantitative) ▪ Describe results ▪ Restate Research Question 2 (Qualitative) ▪ Describe results

Section 8: Discussion ▪ Restate Overall Research Question ▪ Describe how the results, when taken together, answer the overall question ▪ ***Describe how the results confirm or contrast the literature you reviewed

Section 9: Recommendations (if applicable, generally related to practice)

Section 10: Limitations ▪ Discuss, in several sentences, the limitations of this study. ▪ Research Design (overall, then info about the limitations of each separately) ▪ Sample ▪ Instrument/s ▪ Other limitations

Section 11: Conclusion (A brief closing summary)

Section 12: References (APA format)

Share this:

About research rundowns.

Research Rundowns was made possible by support from the Dewar College of Education at Valdosta State University .

- Experimental Design

- What is Educational Research?

- Writing Research Questions

- Mixed Methods Research Designs

- Qualitative Coding & Analysis

- Qualitative Research Design

- Correlation

- Effect Size

- Instrument, Validity, Reliability

- Mean & Standard Deviation

- Significance Testing (t-tests)

- Steps 1-4: Finding Research

- Steps 5-6: Analyzing & Organizing

- Steps 7-9: Citing & Writing

Create a free website or blog at WordPress.com.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Research Report Meaning, Characteristics and Types

Table of contents:-, research report meaning, characteristics of good research report, key characteristics of research report, types of research report, stages in preparation of research report, characteristics of a good report.

A research report is a document that conveys the outcomes of a study or investigation. Its purpose is to communicate the research’s findings, conclusions, and implications to a particular audience. This report aims to offer a comprehensive and unbiased overview of the research process, methodology, and results.

Once the researcher has completed data collection , data processing, developing and testing hypotheses, and interpretation of responses, the next important phase in research is the preparation of the research report. A research report is essential for the communication of research findings to its potential users.

The research report must be free from personal bias, external influences, and subjective factors. i.e., it must be free from one’s liking and disliking. The research report must be prepared to meet impersonal needs.

What is Research Report?

According to Lancaster, “A report is a statement of collected and considered facts, so drawn-ups to give clear and concise information to persons who are not already in possession of the full facts of the subject matter of the report”.

When researchers communicate their results in writing, they create a research report. It includes the research methodology, approaches, data collection precautions, research findings, and recommendations for solving related problems. Managers can put this result into action for more effective decision making .

Generally, top management places a higher emphasis on obtaining the research outcome rather than delving into the research procedure. Hence, the research report acts as a presentation that highlights the procedure and methodology adopted by the researcher.

The research report presents the complete procedure in a comprehensive way that in turn helps the management in making crucial decisions. Creating a research report adheres to a specific format, sequence, and writing style.

Enhance the effectiveness of a research report by incorporating various charts, graphs, diagrams, tables, etc. By using different representation techniques, researchers can convince the audience as well as the management in an effective way.

Characteristics of a good research report are listed below:

- Clarity and Completeness

- Reliability

- Comprehensibility and Readability

- Logical Content

The following paragraphs outline the characteristics of a good research report.

1) Accuracy

Report information must be accurate and based on facts, credible sources and data to establish reliability and trustworthiness. It should not be biased by the personal feelings of the writer. The information presented must be as precise as possible.

2) Simplicity

The language of a research report should be as simple as possible to ensure easy understanding. A good report communicates its message clearly and without ambiguity through its language.

It is a document of practical utility; therefore, it should be grammatically accurate, brief, and easily understood.

Jargon and technical words should be avoided when writing the report. Even in a technical report, there should be restricted use of technical terms if it is to be presented to laymen.

3) Clarity and Completeness

The report must be straightforward, lucid, and comprehensive in every aspect. Ambiguity should be avoided at all costs. Clarity is achieved through the strategic and practical organization of information. Report writers should divide their report into short paragraphs with headings and insert other suitable signposts to enhance clarity. They should:

- Approach their task systematically,

- Clarify their purpose,

- Define their sources,

- State their findings and

- Make necessary recommendations.

A report should concisely convey the key points without unnecessary length, ensuring that the reader’s patience is not lost and ideas are not confused. Many times, people lack the time to read lengthy reports.

However, a report must also be complete. Sometimes, it is important to have a detailed discussion about the facts. A report is not an essay; therefore, points should be added to it.

5) Appearance

A report requires a visually appealing presentation and, whenever feasible, should be attention-grabbing. An effective report depends on the arrangement, organization, format, layout, typography, printing quality, and paper choice. Big companies often produce very attractive and colourful Annual Reports to showcase their achievements and financial performance.

6) Comprehensibility and Readability

Reports should be clear and straightforward for easy understanding. The style of presentation and the choice of words should be attractive to readers. The writer must present the facts in elegant and grammatically correct English so that the reader is compelled to read the report from beginning to end.

Only then does a report serve its purpose. A report written by different individuals on the same subject matter can vary depending on the intended audience.

7) Reliability

Reports should be reliable and should not create an erroneous impression in the minds of readers due to oversight or neglect. The facts presented in a report should be pertinent.

Every fact in a report must align with the central purpose, but it is also vital to ensure that all pertinent information is included.

Irrelevant facts can make a report confusing, and the exclusion of relevant facts can render it incomplete and likely to mislead.

Report writing should not incur unnecessary expenses. Cost-effective methods should be used to maintain a consistent level of quality when communicating the content.

9) Timelines

Reports can be valuable and practical when they reach the readers promptly. Any delay in the submission of reports renders the preparation of reports futile and sometimes obsolete.

10) Logical Content

The points mentioned in a report should be arranged in a step-by-step logical sequence and not haphazardly. Distinctive points should have self-explanatory headings and sub-headings. The scientific accuracy of facts is very essential for a report.

Planning is necessary before a report is prepared, as reports invariably lead to decision-making, and inaccurate facts may result in unsuccessful decisions.

Related Articles:

- nature of marketing

- difference between questionnaire and schedule

- features of marginal costing

- placement in hrm

- limitations of marginal costing

- nature of leadership

- difference between advertising and personal selling

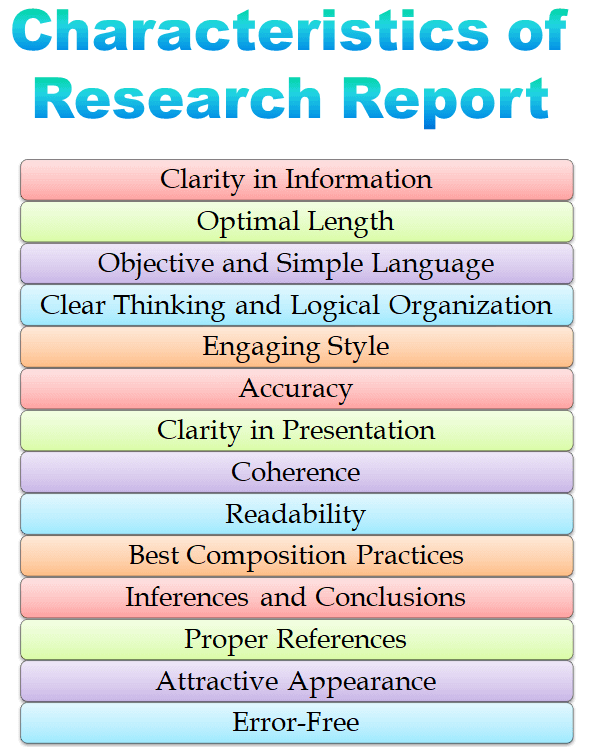

A research report serves as a means of communicating research findings to the readers effectively.

- Clarity in Information

- Optimal Length

- Objective and Simple Language

- Clear Thinking and Logical Organization

- Engaging Style

- Clarity in Presentation

- Readability

- Best Composition Practices

- Inferences and Conclusions

- Proper References

- Attractive Appearance

i) Clarity in Information

A well-defined research report must define the what, why, who, whom, when, where, and how of the research study. It must help the readers to understand the focus of the information presented.

ii) Optimal Length

The report should strike a balance, being sufficiently brief and appropriately extended. It should cover the subject matter adequately while maintaining the reader’s interest.

iii) Objective and Simple Language

The report should be written in an objective style, employing simple language. Correctness, precision, and clarity should be prioritized, avoiding wordiness, indirection, and pompous language.

iv) Clear Thinking and Logical Organization

An excellent report integrates clear thinking, logical organization, and sound interpretation of the research findings.

v) Engaging Style

It should not be dull; instead, it should captivate and sustain the reader’s interest.

vi) Accuracy

Accuracy is paramount. The report must present facts objectively, eschewing exaggerations and superlatives.

vii) Clarity in Presentation

Presentation clarity is achieved through familiar words, unambiguous statements, and explicit definitions of new concepts or terms.

viii) Coherence

The logical flow of ideas and a coherent sequence of sentences contribute to a smooth continuity of thought.

ix) Readability

Even technical reports should be easily understandable. Translate technicalities into reader-friendly language.

x) Best Composition Practices

Follow best composition practices, ensuring readability through proper paragraphing, short sentences, and the use of illustrations, examples, section headings, charts, graphs, and diagrams.

xi) Inferences and Conclusions

Draw sound inferences and conclusions from statistical tables without repeating them in verbal form.

xii) Proper References

Footnote references should be correctly formatted, and the bibliography should be reasonably complete.

xiii) Attractive Appearance

The report should be visually appealing, maintaining a neat and clean appearance, whether typed or printed.

xiv) Error-Free

The report should be free from all types of mistakes, including language, factual, spelling, and calculation errors.

In striving for these qualities, the researcher enhances the overall quality of the report.

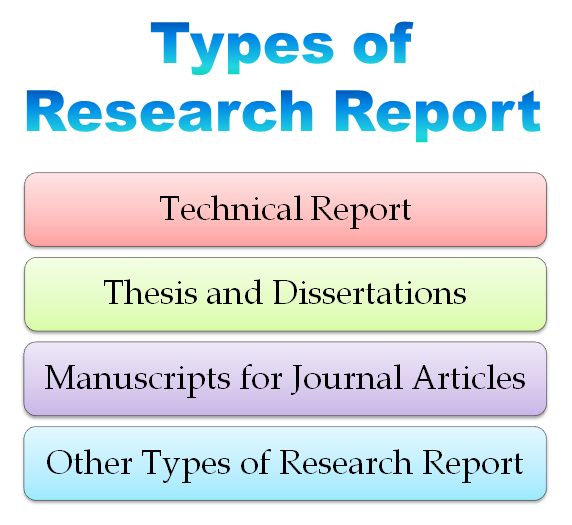

Research reports are of the following types:

- Technical Report

- Manuscripts for Journal Articles

- Thesis and Dissertations

- Other Types of Research Report

1) Technical Report

Technical reports are reports which contain detailed information about the research problem and its findings. These reports are typically subject to review by individuals interested in research methodology. Such reports include detailed descriptions of used methods for research design such as universe selection , sample preparation, designing questionnaire , identifying potential data sources, etc. These reports provide a complete description of every step, method, and tool used. When crafting technical reports, we assume that users possess knowledge of research methodology, which is why the language used in these reports is technical. Technical reports are valuable in situations where there is a need for statistical analysis of collected data. Researchers also employ it in conducting a series of research studies, where they can repetitively use the methodology.

2) Manuscripts for Journal Articles

When authors prepare a report with a particular layout or design for publishing in an academic or scientific journal, it becomes a “manuscript for journal articles”. Journal articles are a concise and complete presentation of a particular research study. While technical reports present a detailed description of all the activities in research, journal articles are known for presenting only a few critical areas or findings of a study. The readers or audience of journal articles include other researchers, management and executives, strategic analysts and the general public, interested in the topic.

In general, a manuscript for a journal article typically ranges from 10 to 30 pages in length. Sometimes there is a page or word limit for preparing the report. Authors primarily submit manuscripts for journal articles online, although they occasionally send paper copies through regular mail.

3) Thesis and Dissertations

Students working towards a Master’s, PhD, or another higher degree generally produce a thesis or dissertation, which is a form of research report. Like other normal research reports, the thesis or dissertation usually describes the design, tools or methods and results of the student’s research in detail.

These reports typically include a detailed section called the literature review, which encompasses relevant literature and previous studies on the topic. Firstly, the work or research of the student is analysed by a professional researcher or an expert in that particular research field, and then the thesis is written under the guidance of a professional supervisor. Dissertations and theses usually span approximately 120 to 300 pages in length.

Generally, the university or institution decides the length of the dissertation or thesis. A distinctive feature of a thesis or a dissertation is that it is quite economical, as it requires few printed and bound copies of the report. Sometimes electronic copies are required to be submitted along with the hard copy of the thesis or dissertations. Compact discs (CDs) are used to generate the electronic copy.

4) Other Types of Research Report

Along with the above-mentioned types, there are some other types of research reports, which are as follows:

- Popular Report

- Interim Report

- Summary Report

- Research Abstract

i) Popular Report

A popular report is prepared for the use of administrators, executives, or managers. It is simple and attractive in the form of a report. Clear and concise statements are used with less technical or statistical terms. Data representation is kept very simple through minimal use of graphs and charts. It has a different format than that of a technical one by liberally using margins and blank spaces. The style of writing a popular report is journalistic and precise. It is written to facilitate reading rapidly and comprehending quickly.

ii) Interim Report

An interim report is a kind of report which is prepared to show the sponsors, the progress of research work before the final presentation of the report. It is prepared when there is a certain time gap between the data collection and presentation. In this scenario, the completed portion of data analysis along with its findings is described in a particular interim report.

iii) Summary Report

This type of report is related to the interest of the general public. The findings of such a report are helpful for the decision making of general users. The language used for preparing a summary report is comprehensive and simple. The inclusion of numerous graphs and tables enhances the report’s overall clarity and comprehension. The main focus of this report is on the objectives, findings, and implications of the research issue.

iv) Research Abstract

The research abstract is a short presentation of the technical report. All the elements of a particular technical report, such as the research problem, objectives, sampling techniques, etc., are described in the research abstract but the description is concise and easy.

Research reports result from meticulous and deliberate work. Consequently, the preparation of the information can be delineated into the following key stages:

1) Logical Understanding and Subject Analysis: This stage involves a comprehensive grasp and analysis of the subject matter.

2) Planning/Designing the Final Outline: In this phase, the final outline of the report is meticulously planned and designed.

3) Write-Up/Preparation of Rough Draft: The report takes shape during this stage through the composition of a rough draft.

4) Polishing/Finalization of the Research Report: The final stage encompasses refining and polishing the report to achieve its ultimate form.

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Logical understanding and subject analysis.

This initial stage focuses on the subject’s development, which can be achieved through two approaches:

- Logical development and

- Chronological development

Logical development relies on mental connections and associations between different aspects facilitated by rational analysis. Typically, this involves progressing from simple to complex elements. In contrast, chronological development follows a sequence of time or events, with instructions or descriptions often adhering to chronological order.

Designing the Final Outline of the Research Report

This marks the second stage in report writing. Once the subject matter is comprehended, the subsequent step involves structuring the report, arranging its components, and outlining them. This stage is also referred to as the planning and organization stage. While ideas may flow through the author’s mind, they must create a plan, sketch, or design. These are necessary for achieving a harmonious succession to become more accessible, and the author may be unsure where to commence or conclude. Effective communication of research results hinges not only on language but predominantly on the meticulous planning and organization of the report.

Preparation of the Rough Draft

The third stage involves the writing and drafting of the report. This phase is pivotal for the researcher as they translate their research study into written form, articulating what they have accomplished and how they intend to convey it.

The clarity in communication and reporting during this stage is influenced by several factors, including the audience, the technical complexity of the problem, the researcher’s grasp of facts and techniques, their proficiency in the language (communication skills), the completeness of notes and documentation, and the availability of analyzed results.

Depending on these factors, some authors may produce the report with just one or two drafts. In contrast, others, with less command over language and a lack of clarity about the problem and subject matter, may require more time and multiple drafts (first draft, second draft, third draft, fourth draft, etc.).

Finalization of the Research Report

This marks the last stage, potentially the most challenging phase in all formal writing. Constructing the structure is relatively easy, but refining and adding the finishing touches require considerable time. Consider, for instance, the construction of a house. The work progresses swiftly up to the roofing (structure) stage, but the final touches and completion demand a significant amount of time.

The rough draft, whether it is the second draft or the n th draft, must undergo rewriting and polishing to meet the requirements. The meticulous revision of the rough draft is what distinguishes a mediocre piece of writing from a good one. During the polishing and finalization phase, it is crucial to scrutinize the report for weaknesses in the logical development of the subject and the cohesion of its presentation. Additionally, attention should be given to the mechanics of writing, including language, usage, grammar, spelling, and punctuation.

Good research possesses certain characteristics, which are as follows:

- Empirical Basis

- Logical Approach

- Systematic Nature

- Replicability

- Validity and Verifiability

- Theory and Principle Development

1. Empirical Basis: It implies that any conclusion drawn is grounded in hardcore evidence collected from real-life experiences and observations. This foundation provides external validity to research results.

2. Logical Approach: Good research is logical, guided by the rules of reasoning and analytical processes of induction (general to specific) and deduction (particular to the public). Logical reasoning is integral to making research feasible and meaningful in decision-making.

3. Systematic Nature: Good research is systematic, which adheres to a structured set of rules, following specific steps in a defined sequence. Systematic research encourages creative thinking while avoiding reliance on guesswork and intuition to reach conclusions.

4. Replicability: Scientific research designs, procedures, and results should be replicable. This ensures that anyone apart from the original researcher can assess their validity. Researchers can use or replicate results obtained by others, making the procedures and outcomes of the research both replicable and transmittable.

5. Validity and Verifiability: Good research involves precise observation and accurate description. The researcher selects reliable and valid instruments for data collection, employing statistical measures to portray results accurately. The conclusions drawn are correct and verifiable by both the researcher and others.

6. Theory and Principle Development: It contributes to formulating theories and principles, aiding accurate predictions about the variables under study. By making sound generalizations based on observed samples, researchers extend their findings beyond immediate situations, objects, or groups, formulating generalizations or theories about these factors.

1. What are the key characteristics of research report?

You May Also Like:

Scope of Business Research

Data Collection

Questionnaire

Difference between questionnaire and schedule

Measurement

Data Processing

Nature of Research

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Research Report

- Post last modified: 11 January 2022

- Reading time: 25 mins read

- Post category: Research Methodology

What is Research Report?

Research reporting is the oral or written presentation of the findings in such detail and form as to be readily understood and assessed by the society, economy or particularly by the researchers.

As earlier said that it is the final stage of the research process and its purpose is to convey to interested persons the whole result of the study. Report writing is common to both academic and managerial situations. In academics, a research report is prepared for comprehensive and application-oriented learning. In businesses or organisations, reports are used for the basis of decision making.

Table of Content

- 1 What is Research Report?

- 2 Research Report Definition

- 3.1 Preliminary Part

- 3.2 Introduction of the Report

- 3.3 Review of Literature

- 3.4 The Research Methodology

- 3.5 Results

- 3.6 Concluding Remarks

- 3.7 Bibliography

- 4 Significance of Report Writing

- 5 Qualities of Good Report

- 6.1 Analysis of the subject matter

- 6.2 Research outline

- 6.3 Preparation of rough draft

- 6.4 Rewriting and polishing

- 6.5 Writing the final draft

- 7 Precautions for Writing Research Reports

- 8.1.1 Technical Report

- 8.1.2 Popular Report

- 8.2.1 Written Report

- 8.2.2 Oral Report

Research Report Definition

According to C. A. Brown , “A report is a communication from someone who has information to someone who wants to use that information.”