Policymaking Process

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

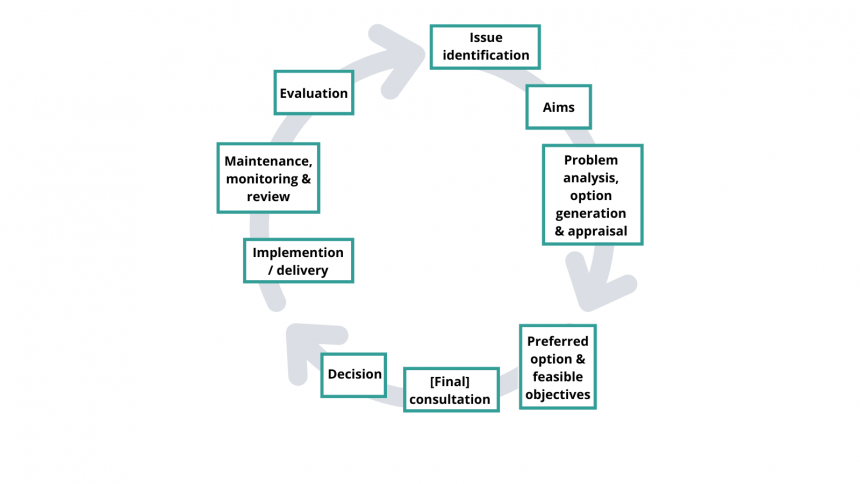

Agenda setting, formulation, decision-making, implementation, reference list.

US$ 20, 000 for a ticket, US$ 50, 000 to access smaller discussion units away from the main conference, and US$ 60, 000 for accommodation on the lower side. That is the cost of attending the ongoing 43 rd World Economic Forum popularly referred to as Davos 2011.

Global leaders in various fields; industry, academia, civil society, government, and the media converge at the Swiss Ski resort during the annual meeting to reflect on, rethink, strategize, explore, find solutions to, and develop policies that shape world agenda. The meeting is one of the occasions when policymaking is a core business of the day. The art of policymaking is a common practice amongst leaders in many organizations whether public or private.

According to the American Heritage Dictionary (2006), “policy making is; high development more particularly of official government policy’’. Officials in government institutions do develop public policies in order to provide solutions to public issues by means of a political process. Although policymaking is normally a long tedious demanding process, all the steps involved are actually necessary for desirable results to be archived. Policy making conforms to the steps discussed below for a better yield.

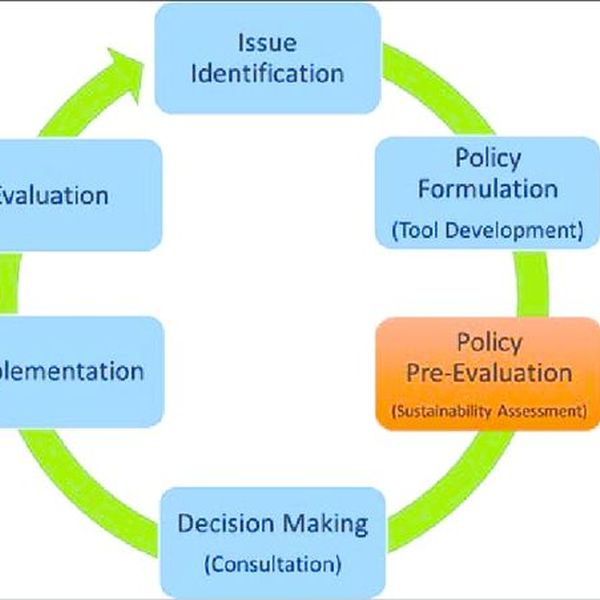

This is the initial step into policy making where an issue of concern and/or to be evaluated by the government is brought up. The issue may be tabled by the government or citizens during consultations with government officials. Such consultations are necessary as individuals can advise on issues affecting them which officials may be oblivious of. If various matters come up to be addressed at this stage, prioritization is done in order to select what to first handle when all cases cannot be addressed at that particular juncture.

Politicians, public officials, and elites should be accountable for their actions to the public and not pursue their personal interests without any constraints. Governments, and any other institutions for that matter involved in decision making process should be transparent and accessible to the public. Any concerns raised by stakeholders are factored in the process and they are offered a chance to freely challenge the decision making process.

After setting the agenda described above, possible solutions are then elaborated at this stage. Public demand is taken into account in formulating a solution to the issue and possible available options are carefully weighed out.

Special interest groups such as those whose concerns lie with the environment, business, and human rights, among others are consulted in the formulation process, caution is however taken not to divert from the main objective of the policy for their own purpose. It is understood that since many conflicting interests are involved, there is no one correct solution to the agenda as complex issues need to be solved in a versatile environment characterized by uncertainty.

After all considerations in the formulating process, a final decision is taken by the government amongst the possible solutions floated. There are several possibilities in this decision-making. The government can go ahead with its proposal to the solution, use other counterproposals made by stakeholders, or compromise between the two. The decision can also be to take no action in which case the status quo is maintained.

With the final decision made, government officials possibly together with all the stakeholders translate the policy to a concrete action plan by use of substantive policy tools. An entirely new routine sometimes arise from the made decision. In some cases, new regulations are mandated and enforcement procedures developed to allow for the implementation of the policy.

This is the final stage of a policy making process. According to Lindblom (1968), evaluation is, “the systematic assessment and acquisition of information so as to provide useful feedback about some object”. This can be performed by government officials or other parties concern with the policy once implemented.

Formal means of evaluation like data analysis, or informal ones involving citizens’ reaction are deployed in evaluating the policy. Of concern during the evaluation process include among others: the effectiveness and net impact of the policy- that is, a revelation of failures, successes or need for any modifications to be made. In the event of a problem with a particular policy, the policy-making steps begin again.

Commitment to consultations and information is important in enhancing active participation at all levels and should be embraced. This should be taken in good time; at initial stages of policy making process to gather numerous possible solutions and required information. Clarifications on the public’s limit of access to information, citizen’s rights as pertaining to the policy, and procedures for feedback are made.

Adequate material and human resources are allocated to implementing the policy in addition to cross government and public coordination so as to enhance feedback and implementation. Together with promoting active citizenship and evaluation of a policy, transparent, amenable, external scrutiny of a policy making process leads to accountability.

In a nutshell, implementation of all the above steps results in: strengthened public trust in their officials, meeting of societal challenges, and improvement of the quality of a policy.

Editors of The American Heritage dictionaries. (2006). The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language , 4 th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Lindblom, C. (1968). The policy making process . Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Role of the American Constitution in America’s Political Process

- Public Policy Administration in Modern Society

- Christianity Role in American Policymaking

- The Process of Formulating Policy

- Nurse Participation in Policy-Making

- Bill AB 119 by Dave Jones

- Courtroom Observation

- The US Congress, Presidency and Bureaucracy

- Should Illegal Immigrants be Deported?

- Zimbabwe “blood diamonds” dispute breaks out at U.N.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, July 31). Policymaking Process. https://ivypanda.com/essays/policy-making/

"Policymaking Process." IvyPanda , 31 July 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/policy-making/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'Policymaking Process'. 31 July.

IvyPanda . 2018. "Policymaking Process." July 31, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/policy-making/.

1. IvyPanda . "Policymaking Process." July 31, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/policy-making/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Policymaking Process." July 31, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/policy-making/.

IvyPanda uses cookies and similar technologies to enhance your experience, enabling functionalities such as:

- Basic site functions

- Ensuring secure, safe transactions

- Secure account login

- Remembering account, browser, and regional preferences

- Remembering privacy and security settings

- Analyzing site traffic and usage

- Personalized search, content, and recommendations

- Displaying relevant, targeted ads on and off IvyPanda

Please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy for detailed information.

Certain technologies we use are essential for critical functions such as security and site integrity, account authentication, security and privacy preferences, internal site usage and maintenance data, and ensuring the site operates correctly for browsing and transactions.

Cookies and similar technologies are used to enhance your experience by:

- Remembering general and regional preferences

- Personalizing content, search, recommendations, and offers

Some functions, such as personalized recommendations, account preferences, or localization, may not work correctly without these technologies. For more details, please refer to IvyPanda's Cookies Policy .

To enable personalized advertising (such as interest-based ads), we may share your data with our marketing and advertising partners using cookies and other technologies. These partners may have their own information collected about you. Turning off the personalized advertising setting won't stop you from seeing IvyPanda ads, but it may make the ads you see less relevant or more repetitive.

Personalized advertising may be considered a "sale" or "sharing" of the information under California and other state privacy laws, and you may have the right to opt out. Turning off personalized advertising allows you to exercise your right to opt out. Learn more in IvyPanda's Cookies Policy and Privacy Policy .

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 How is Policy Made?

Katherine Knutson; Samantha Vang; and Brenda De Rosas Lazaro

Wondering why some text is in blue? Click here for more information.

4.0 Where is policy made?

This chapter provides an overview of the policymaking process…it’s the “nutsy-boltsy” chapter, as one of my former public policy students would say. [1] Ideally, this chapter would be as simple as describing how a bill becomes a law, but the reality is much more complex because policymaking occurs in multiple venues. My goal in this chapter is to provide you with a broad view of how policymaking happens in each of these venues, but it will definitely oversimplify the process.

We’ll start this chapter by describing the legislative process for policymaking at the federal level, which is similar to what happens in state legislatures. The executive branch is also responsible for quite a bit of policymaking, both through executive actions by the president and through the creation of regulations by the bureaucracy. Again, we’ll focus on the federal level, though there are similarities at the state level. Finally, we’ll discuss the policymaking that comes from the judiciary.

Legislative policymaking

Congress is the place to start when it comes to understanding federal policymaking if, for no other reason than the Constitution clearly states that all legislative powers are the prerogative of Congress (Article I, Section I). Ideas for new policy are written (by a team of non-partisan lawyers who work in the Office of the Legislative Counsel in either the House or Senate) into documents called bills. Bills are introduced in the House or Senate by a member of that chamber. Ideas for bills can come from anywhere, but only a Representative can introduce a bill into the House and only a Senator can introduce a bill into the Senate. Once a bill is introduced, it is given a number. Bills introduced in the House have the letters H.R. before the number. Bills introduced in the Senate have the letter S. before the number. In addition to bill s , which represent a proposal to create, amend, or remove policy language, members of Congress might also introduce a resolution , which are used to express ideas, set internal rules for Congress, or propose constitutional amendments.

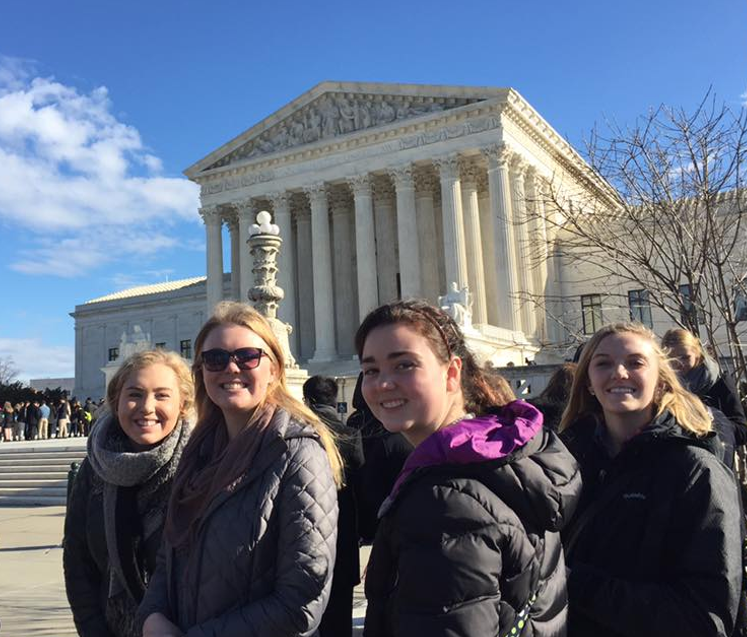

Figure 4.1: Gustavus students meet with Minnesota Representative Tim Walz in his office in Washington, D.C. in January 2017

The Senator or Representative who introduces the bill or resolution is called the sponsor . Other members can cosponsor the bill if they would like to support it. Members can only sponsor or cosponsor a bill that is introduced in their chamber (i.e. a Senator can sponsor or cosponsor a Senate bill but cannot sponsor or cosponsor a House bill). Identifying sponsors and cosponsors is important because it provides clues about support for a measure. For example, some bills are cosponsored only by members of one political party, while others have bipartisan support.

After a bill or resolution is introduced in a chamber and given a number, it is assigned to a committee for consideration based on the topics of the bill or resolution. Each committee has a jurisdiction , or set of topics it oversees, although there is some overlap between committees. The House has twenty standing committees and the Senate has sixteen standing committees. While some of the committees line up between the two chambers (both have an Armed Services Committee and a Judiciary Committee, for example), the overlap is not perfect. The House has an Agriculture Committee while the Senate has an Agriculture, Nutrition, and Forestry Committee. These small differences can make it even more challenging when the two chambers are trying to pass legislative language that needs to be identical. In both chambers it is possible to refer a bill to more than one committee. This is called making a multiple referral .

Committees are a critical gatekeeping part of the process. In theory, the committee’s job is to study the bill, deliberate over it, and make a recommendation, but in practice, a committee is where most bills and resolutions go to die. This is because committees are not required to do anything with the bills and resolutions referred to them and because committee chairs have quite a bit of power to prevent action on a bill they oppose. Each committee has a professional staff (two thirds of which are selected by the majority party and one third of which is selected by the minority party) that helps it review the proposals before it. Committees are further subdivided into subcommittee s based on the topic of the legislation.

When a committee or subcommittee wants to act on a proposal, they will seek out additional information. They may ask the Government Accountability Office to provide additional information about the proposal. The Congressional Budget Office might provide an estimate of the costs. The committee or subcommittee might hold a hearing in which they invite people to provide testimony and answer questions from committee members.

When the committee or subcommittee feels it has enough information to act, the next step is to hold a markup hearing . During a markup, the committee or subcommittee will move line by line through the proposal, making changes, called amendments. If the proposal has been assigned to a subcommittee, a majority of members of the subcommittee need to approve of moving the proposal back to the full committee. Then the full committee votes about whether to approve the proposal and send it on to the full chamber. The committee can report the bill favorably (meaning they support its passage), adversely (meaning they oppose its passage), or without recommendation. Since committees aren’t required to act on a bill, they don’t often report bills that they don’t support.

If the committee made changes to the proposal, those changes are reported as a single amendment. If they made a lot of changes, the committee might just write and report an entirely new bill that includes all the changes (called a “clean” bill). When a committee reports a bill, it also creates a written report to go along with the bill. The committee report explains the purpose of the bill and outlines the reasons the committee supports it (and, when applicable, why the minority opposes it). The report also explains exactly how the proposal will change existing law. The committee’s report gives insight into Congress’ intentions for the proposal and so it is used by bureaucratic agencies and the courts when they are interpreting the bill’s purpose and meaning.

Once a bill or resolution has been reported from committee, it is ready for the full chamber to act and so it gets added to the bottom of the legislative agenda, called the calendar. There are a lot of items on the legislative calendar and only so much time for debate and voting, so both chambers have ways of prioritizing the policies on which they want to act. In the House, this is done through the Rules Committee , which sets special rules for debating proposals. The House (and the Rules Committee) is strongly controlled by the majority party because it operates mostly on the principle of majority rule. If the majority party wants to act on a proposal in the House, it is relatively easy for them to do so. The Rules Committee will issue a rule that moves an item up on the calendar and outlines the plan for debate and voting. The Rules Committee can make it so that only the committee’s amendments are allowed and can limit the total time available for debate.

In the Senate, the majority party does not have quite as much power, unless they control at least 3/5ths of the seats. This is because the Senate has a rule that allows for individual senators to speak for as long as they wish about any topic of their choice ( filibuster ). Ending a filibuster requires a vote by 3/5ths of senators, or 60 Senators. The threat of a filibuster means that the Senate doesn’t often debate proposals unless there is some agreement by both parties to do so.

The process of debating the proposals in both chambers is fairly complicated, but it’s not necessary to understand all the ins and outs of parliamentary procedure for our purposes. It is important to know that both chambers might amend the proposal during the floor debate and voting process. Members of Congress may make floor speeches during the debate period to articulate their position. The Congressional Record contains a v erbatim record of the text of floor debates and other activity that happens on the floor. Occasionally a member of Congress will ask that remarks be inserted into the Congressional Record, meaning that they didn’t actually speak the remarks on the floor of the chamber.

If the proposal gets to the point of a vote, it could be a recorded vote , which provides a list of which people voted for and against the proposal. It could also be done as a voice vote , in which case we would know that the bill passed or failed but not by how much or by who. A proposal can also be passed by unanimous consent , which means that no official vote was taken but no one spoke up to oppose its passage.

In order for a proposal to become law, it must pass both chambers in exactly identical form. It shouldn’t be hard to see that this is a very difficult requirement because the process is happening in different venues and is controlled by different actors in each venue. Surprisingly, however, many bills do emerge identically and this is usually because one chamber waits for the other to pass the bill first and then adopts identical language. It doesn’t matter which chamber begins the process, except when it comes to bills to raise revenue, which must originate in the House according to the Constitution (Article I, Section 7).

The one constraint in timing is that both chambers start over every two years in a new congress after new members are elected. Elections are held in the fall of even years and the new congress begins in January of odd years and runs for two years. Any proposals that haven’t moved through the system by the end of a two-year period have to start again from the beginning in the next congress.

If the bills passed by each chamber aren’t identical, the two chambers can work out differences informally (called ping ponging) by making amendments or they can arrange for a formal conference committee , in which representatives from both chambers try to work out an agreement between the two proposals. If changes are made through either of these techniques, the final language needs to go back to the two chambers for final approval.

Figure 4.2: The textbook version of the legislative process

To complicate matters a little more, there are really two separate tracks for policymaking. The first track is the authorization process. Authorizing bills reflect Congress’ support for the idea of the policy. Essentially Congress says, “yes, we want to create this policy.” But the authorizing process doesn’t confer any money toward the policy. This happens through the appropriations process , where Congress approves spending money on policies they have authorized. Congress can authorize whatever it wants, but until money is appropriated, there is no way to move the proposal into action. So, the proposals need to survive the process not once, but twice (once as authorizing legislation and once as appropriations legislation) in order to have a chance of success.

But that’s not the end. Bills and joint resolutions that aren’t constitutional amendments require executive action. The passed bill or joint resolution is sent to the President. The president has three possible options. First, the president can sign the bill into law. Second, the president can veto , or formally oppose, the bill. If the president vetoes the bill, Congress can try to override the presidential veto. This requires a vote of 2/3rds in both chambers and is very difficult to achieve; only 5% of presidential vetoes have been overridden. Third, the president can do nothing. If there are more than ten days left in the current congress (not counting Sundays), the bill will become law without the president’s signature. If there are fewer than ten days left in the current congress, the bill dies in what is called a pocket veto . This puts some pressure on Congress to act ahead of this ten day window if they anticipate a possible veto.

So that’s the legislative process. Except that in a lot of cases, it doesn’t work this way at all. Recent changes have led to what Barbara Sinclair calls “unorthodox lawmaking”, which bypasses many of the processes outlined in this traditional model. [2] One of the biggest ways in which lawmaking has become unorthodox is the use of omnibus bills. An omnibus bill is a massive bill that packages a lot of smaller bills together. This is especially common in the appropriations process, but it can happen for authorizing bills as well. Another unorthodox method is for party leaders to negotiate a proposal bypassing committees and then substitute that proposal for existing language.

Following the legislative process can provide a lot of information about a proposal. The website congress.gov allows researchers to search for bills and resolutions introduced since 1973. In addition to providing the full text of the proposal, you can find information about sponsors and cosponsors, committee referrals, debates, and voting. You can also locate committee reports on this website, which explain the proposal and provide information about the arguments for and against the proposal.

Most state legislatures operate using a similar process. Every state but Nebraska has a bicameral legislature and requires proposals to be passed in both chambers. [3] State legislatures use committees to handle the workload and governors have the opportunity to veto legislation.

Executive policymaking

When Congress passes legislation, it often sacrifices detail in an effort to win enough votes for passage, leaving bureaucratic agencies, boards, and commissions the task of sorting out the details required for implementation. In fact, many laws specifically require agencies to develop the strategy for achieving the goals outlined in the law. In other cases, Congress has delegated authority to an agency over a certain type of activity within society. In any case, an agency cannot issue a rule or regulation unless it has been granted the authority to do so by a law passed by Congress. Every rule and regulation that gets passed will include language that identifies its statutory authority, or the specific law that authorizes the agency to act.

The Administrative Procedure Act (APA) outlines the guidelines for how agencies must go about the work of developing the rules needed to implement legislation or to regulate the aspect of activity over which it has been given authority . This process is called rule making. Proposed and finalized rules and regulations are published in the Federal Register and later cataloged according to subject matter in the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR).

In discussing this topic, both scholars and practitioners use the terms rule and regulation somewhat interchangeably, though there is a subtle difference. The text of the APA specifically defines the term “rule” but it doesn’t define “regulation” even though the text of the law refers to regulations quite often. The difference between the terms seems to come down to how the courts have interpreted the actions of federal agencies. [4] Legislative (also known as substantive) rules are also called regulations. A regulation is a statement issued by a government agency, board, or commission that has the force and effect of a law passed by Congress. The APA requires that agencies give the public the “opportunity to participate in the rule making through submission of written data, views, or arguments.” [5] Regulations must go through this notice-and-comment rulemaking process.

In contrast, interpretive rules do not require notice-and-comment and can be issued without public input. Interpretive rules do not have the force of law but explain the agency’s interpretation of laws or regulations. Technical corrections to rules also are allowed without the notice-and-comment process.

Let’s take a minute to dive into rulemaking , the process of creating rules and regulations. [6] An agency might begin this process after receiving new legislation passed by Congress or it might begin it in response to an emerging problem, recommendation from other agencies or the public, or an order from the president or court. Before it begins to develop a rule, an agency might gather information or even announce its plans to begin the process by posting an “Advance Notice of Proposed Rulemaking” in the Federal Register. Doing this invites interested parties to provide comments about whether a rule is necessary even before the agency begins to draft the rule.

Once an agency decides that a rule is needed, bureaucrats within the agency draft the proposed rule. In addition to detailing the rule itself, federal laws require that they also explain the legal basis for the rule, the rationale for the rule and the data and evidence that was used to develop the rule. Other laws passed by Congress require agencies to estimate the costs and benefits of the proposed rule, estimate the paperwork burden it will place on the public, and analyze the proposed rule’s impact on small business and state and local governments.

More recently (beginning in the 1980s), agencies have begun using a process called negotiated rulemaking in which the agency invites interested actors, such as interest groups representing affected interests, to shape the initial proposal. The goal of negotiated rulemaking was to make the process less adversarial by bringing interested actors to the table sooner in the process and, hopefully, avoiding lawsuits after the final rule was issued. Unfortunately, preliminary research suggests that this alternative process hasn’t had the desired effect in reducing legal challenges. [7]

Before it is shared publicly, the rule is reviewed by the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA, pronounced “oh-eye-ruh”), which is housed within the Office of Management and Budget within the Executive Office of the President. Once the proposed rule receives approval from the administration, the proposal is shared publicly as a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on the Federal Register.

At this stage, members of the public are invited to provide written feedback on the proposal through the website regulations.gov , which makes it easy for the public to find and comment on proposed rules. Interest groups are especially active in this phase as they provide detailed arguments regarding the proposed rule, but anyone is invited to provide feedback. The window for public comment is usually set at 30-60 days. Agencies can also hold public hearings during this public comment period.

Here’s an example of a proposed rule that would change how the federal government collects information about race and ethnicity that, as of January 27, 2023 was open for public comment: https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2023/01/27/2023-01635/initial-proposals-for-updating-ombs-race-and-ethnicity-statistical-standards.

Proposed Rule 2023-01635

Following the public comment period, the agency must review all of the feedback that it gathered and then decide whether to modify the proposal, move forward with it, or withdraw the proposal. An agency is not allowed to make a decision based on the number of comments in favor or opposed to the proposal, but rather the arguments and evidence raised in the public comment period. The agency must be able to explain how the proposed rule will help solve the problem or accomplish the goals it identified. If the agency plans to move forward with the proposed rule, they must address any significant critiques raised in public comments. Once again, the OIRA gets an opportunity to review the proposed regulation in its new form.

Finally, the agency publishes a Final Rule in the Federal Register. A final rule includes a section that describes the problem that the rule is addressing and identifies the specific statute that gives it authority to act. In addition to publication in the Federal Register, the new rule is sent to Congress and to the Government Accountability Office for review. At this point, the House and Senate can pass a joint resolution of disapproval if they do not support the rule. This joint resolution requires the president’s signature to void the rule. Congress has 60 days to review new rules. [8]

After publishing the rule, agencies develop even more rules, called interpretive rules, to help provide guidance about how the rule will be enforced and to help the public understand the regulation. These interpretive rules don’t require a notice-and-comment period and they may or may not be published in the Federal Register.

Once the rule is finalized, the door is open to legal challenges. Individuals or organizations (government or nongovernment) can challenge the rule by arguing that it violates a provision of the Constitution, goes beyond the statutory authority granted to the agency, violated the Administrative Procedure Act (by not having following the notice-and-comment period, for example), or was “arbitrary, capricious, or an abuse of discretion”. [9] For example, several judges used this standard to block proposed rules from the Trump administration in 2019 regarding restrictions against giving federal money to agencies that perform or promote abortion. Courts have the option of upholding the rule or vacating the rule , which means that they declare the rule void or unenforceable. A court may vacate a rule temporarily while it reviews the complaint in order to stop the new rule from going into effect. In the abortion cases I mentioned, the judges issued preliminary injunctions which created a temporary hold on implementing the new regulation until a court could fully review the regulation.

While a lot of the focus on the bureaucracy’s power of policymaking is centered on the rulemaking process, policies get set every day on the ground by actors that Michael Lipsky called, street-level bureaucrats . [10] Lipsky points to government workers like police officers, social workers, and teachers who are responsible for delivering government services and who, in the course of their day-to-day activities make decisions that “add up to…agency policy.” [11] Street-level bureaucrats gain this policymaking power because they are able to use discretion in making decisions and because they have a great deal of autonomy.

To give an example, speeding is against the law, but a police officer, who is often patrolling alone in their vehicle, makes an independent decision about whether to pull someone over who is traveling five miles over the speed limit. Frank Baumgartner, Derek Epp, and Kelsey Shoub explore this very topic in a book that analyzes over 20 million traffic stops made in North Carolina over the course of a decade. Baumgartner et al. find that “powerful disparities exist in how the police interact with drivers depending on their outward identities: race, gender, and age in particular.” [12] Similarly, Lipsky argued that “the poorer people are, the greater the influence street-level bureaucrats tend to have over them.” [13]

The policymaking that happens through street-level bureaucrats is less of a process and more of a practice. It happens without much of a plan and is more visible as we look back at the pattern of behavior that has emerged over time. As Baumgartner et al.’s research shows us, because it generally targets particular groups of people (like Black drivers), it can be largely invisible to other groups who are not targeted (White drivers).

Before we talk more about the policymaking that comes through the courts, there is one more source of executive policymaking to discuss and that is the policymaking power of the president.

Though the Constitution describes the president’s power as executive, most presidents have found ways to expand their influence over policymaking in both formal and informal ways. There is little in the Constitution that gives presidents legislative powers over domestic matters aside from the ability to sign or veto legislation. Presidents have more power over foreign and military affairs through their position as commander in chief and through their power to negotiate treaties (which still require ratification by the Senate). However, presidents have used the “take care clause” (Article 2, Section 3) to carve out a larger role in domestic policymaking through the use of executive orders and memoranda.

An executive order is a statement issued by a president that creates or modifies laws or the procedures of the federal government independently of congressional action. Executive orders aren’t technically legislation and they don’t require the approval of Congress even though they can result in a major change to policy. Executive orders are numbered consecutively and published in the Federal Register like regulations, but unlike regulations, there is no review process. Congress can pass legislation to counter an executive order, a new president can overturn an existing executive order, and executive orders are subject to judicial review. [14]

All presidents have used executive orders, and some have used them as a tool for major changes. For example, President Harry Truman used an executive order to desegregate the military and President Ronald Reagan used an executive order to prevent family planning clinics that receive federal money from informing clients about abortion options. Executive Order 9066 forcibly placed over 100,000 men, women, and children of Japanese ancestry (most of whom were U.S. citizens) into internment camps during World War II. [15]

Presidents also issue proclamations, which are similar in nature to a simple or concurrent resolution passed by Congress in that they express a sentiment of the president but don’t create new policy.

Finally, in recent years (beginning in earnest with President Ronald Reagan), presidents have taken to issuing signing statements. Signing statements are written documents that are issued when presidents sign new policies into law. They identify portions of the law that the president believes violates the Constitution and that the president will not enforce. [16] Signing statements are controversial, but presidents use them because they are not allowed to veto only a portion of a bill.

The delegation of legislative power to the president and the bureaucracy is controversial. Libertarians have opposed the so-called administrative state since it emerged as part of the New Deal. Opposition grew in the 1970s and 80s, with opponents arguing that it is unconstitutional for Congress to delegate power to administrative agencies. This position was upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 2022 case West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency , which restricted the Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to regulate emissions without explicit guidance from Congress. [17] The decision has potential implications for many other regulations issued by other agencies if similar claims are made that the agency lacks explicit congressional authority to act.

Judicial policymaking

Although courts do not like to think of themselves as making policy, their decisions certainly have that effect. Judicial rulings define policy, compel action, and stimulate additional policymaking. G. Alan Tarr identifies several forms of judicial policymaking: constitutional, remedial, statutory interpretation, oversight of administrative activity, and cumulative. [18]

Figure 4.3: Gustavus students wait in line to hear oral arguments at the U.S. Supreme Court in January 2017. No cameras, including those belonging to the media, are allowed in the courtroom during oral arguments.

The process of judicial review is complex because most of the provisions under consideration are not entirely clear. Take, for example, the constitution’s protection in the Fourth Amendment against unreasonable searches and seizures. The constitution doesn’t specify what counts as “unreasonable” or even what counts as a “search”. Legislatures create policies to define these concepts, but the ultimate interpretation of whether a policy violates the constitution comes down to the courts.

Courts also engage in remedial policymaking. This means that when constitutional violations are found, the courts often create guidelines for remedying the situation. The goal in these orders is not to make up for past damages but rather to change behavior in the future. A court might, for example, order a police department to change its practices for conducting traffic stops in response to a pattern of discriminatory behavior.

In addition to questions involving the constitutionality of laws, courts are involved in the interpretation of statutes (laws). A law might be unclear or it might conflict with another law. It may be difficult to decide whether a law applies to a new situation that wasn’t anticipated by those who wrote the original law. In these cases, courts play a role in determining what the law means and how it should be applied, which sets policy.

Courts also provide oversight of administrative activity, or the actions taken by bureaucrats. Cases arise when individuals or institutions claim that an agency has acted above and beyond what statute allows. The claim here is that the agency has violated the law rather than the constitution and it is up to the courts to determine whether the claim has merit. The inverse is also true; an individual or institution can claim that an agency has failed to act when the law requires them to do so. Again, the courts play a role in reaching a conclusion about these claims.

Finally, as Tarr points out, even when an individual case might seem minor and inconsequential, the cumulative effect of decisions can impact the direction of public policy. Courts rely heavily on precedent , or the decisions reached in prior cases. Judges rely on precedent for new cases, which means that past rulings can shape current and future decisions.

In acting as policymakers, judges operate within a unique environment. Unlike legislative or executive policymakers, judges generally cannot choose which issues they address. Those with legal standing, or a legal reason to bring a case before a court, bring cases before judges to one of the federal district courts or state trial courts. Only the Supreme Court has control over which cases it hears, and still it is constrained to hear only the cases that are appealed to it.

At the first level of the court system, criminal and civil trials sometimes use juries. Criminal trials involve a person being accused of committing a crime against society as a whole and so the case is brought by the government against the person accused of the crime. A criminal trial can result in a financial penalty, incarceration, or even death. A civil trial involves a dispute between two individuals or organizations. A civil trial can only result in a financial penalty. In these trials, the jury is presented with evidence and witnesses and then makes a decision. The judge helps to clarify the relevant law and provides instructions to the jury as to how to interpret the law, but ultimately, the decision is left to the jury. The job of the judge at this level is to ensure that the process is fair and follows guidelines established by law and the Constitution.

In practice, though, very few cases in the legal system end up in a jury trial. At the federal level, fewer than 2% of cases result in a jury trial. [19] The main factor that accounts for this low number in criminal cases is mandatory minimum sentencing, which provides incentive for defendants to accept a plea deal , which means that the defendant pleads guilty in exchange for a lighter sentence. When a plea deal is reached, the judge has the authority to approve or reject the agreement and also has some discretion in sentencing. In civil cases, mandatory arbitration and caps on monetary awards for pain and suffering make it more difficult and less appealing to take a case to trial.

In civil cases, either party can appeal the decision to a higher court. In criminal cases, the defendant can appeal if they lose the case. [20] Appealing a case involves more than just being disappointed in the outcome; it requires making a claim that there were errors in the procedure at the lower level or in the judge’s interpretation of the law. At the federal level, appealed cases go to the circuit court. At the state level, appealed cases either go to an appellate court or to the state supreme court, depending on the structure of the state’s judicial system. In reality, most decisions are not appealed. At the federal level, only 15% of district court cases are appealed. [21]

Appellate court judges do not retry the case or review new evidence or witnesses. Instead, they review the original case to see if any mistakes were made in the process or in how the law was interpreted. Appellate courts use legal briefs submitted by the two parties and occasionally they will hold oral arguments featuring lawyers from the two parties. At the federal level, appellate courts usually review cases as a group of three judges, called a panel. [22] The appellate judges will deliberate and then issue a written decision, called an opinion, that explains the court’s rationale. Very few cases are overturned at this level or sent back to the original court for review or retrial. In fact, sometimes the appellate court will uphold the ruling even if they find the trial judge made an error if they think the error was minor or did not affect the outcome. When a federal appellate court issues a ruling, that ruling becomes precedent for all of the district courts within the geographic area covered by the appellate court.

The U.S. Supreme Court is the final court of appeals and it hears cases coming from both the federal court system and from the state supreme courts. Unlike other courts, the Supreme Court gets to choose which cases it hears from among those that are appealed to it. It takes four Justices to agree to hear a case. The Supreme Court reviews written arguments (briefs) that are prepared in advance, but unlike at the appellate level, the Court almost always holds oral arguments for the case. During oral arguments, each party is given 30 minutes to make their case. The justices interrupt often with questions for the lawyers. Following the oral arguments, the justices meet in person to discuss the case. The Chief Justice will assign one justice to write a majority opinion. Other justices might choose to write a dissenting opinion if they disagree with the majority position or a concurring opinion if they agree with the majority but for different reasons.

When the U.S. Supreme Court issues its rulings, the decisions become precedent that cover the entire country, essentially setting a new federal policy.

Direct policymaking

In some states, the public is given the power to create policies through ballot measures. The initiative process allows individual citizens or groups to propose a new law and, in some cases, a constitutional amendment, which is then voted on by citizens in an election. A referendum is when a state legislature passes a law but places it on the ballot for voters to either uphold or repeal. 24 states have an initiative process and 23 states have a referendum process. Every state but Delaware requires citizens to vote on changes to the state’s constitution.

The role for public participation in policymaking through initiatives, referendum, and constitutional amendments developed during the populist and progressive movements of the early 1900s. Reformers attacked the power held by economic elites and demanded political reforms that would help level the playing field for average citizens. In addition to advocating for policy changes like a ban on child labor, improved living conditions in urban areas, and an income tax system, Progressives advocated for political reforms like use of a secret ballot (Australian ballot) and avenues for direct public influence over policy and politics–the initiative, referendum, and recall. These movements were especially successful in the west and midwest, which is why many of those states have direct policymaking processes while many east coast states do not.

Activists have used the initiative process to enact all kinds of public policies, from ending Affirmative Action to allowing same-sex marriage. The National Conference of State Legislatures keeps a database of all of the ballot measures since the late 1800s. Interest groups, in particular, have used the initiative process to achieve their policy goals, spending millions of dollars to get measures on the ballot and to influence voters. In 2020, the average cost of getting an initiative on the ballot was $2.1 million!

There is no initiative or referendum process at the federal level. Changes to the U.S. Constitution require that the House and Senate both pass a joint resolution by a 2/3rds vote. Then the measure is sent to the states where 3/4ths of the states must ratify the proposed amendment either through a state constitutional convention or through the state legislature.

Minnesota does not have an initiative or referendum process. Changes to Minnesota’s constitution happen when a majority of each chamber in the legislature pass a proposed constitutional amendment. That amendment goes before voters in the next general election. Passage requires a majority of all of the people who vote in the election, so if someone casts a ballot but doesn’t make a selection on the proposed constitutional amendment, it counts as a vote against the proposal.

4.1 How are venues chosen?

Sometimes actors have very little choice as to which venue to pursue. If an issue affects a particular state, it is likely that the issue will be taken up by a state legislature, executive, or judiciary. If a question involves federal regulation, the federal bureaucracy is the appropriate venue. Sometimes, however, actors have options and they will operate strategically to push their issue into a more favorable venue..

Remember back to our discussion of the Punctuated Equilibrium Theory and the technique of venue shopping . Policy actors strategically seek out venues that might be more favorable to their desired outcome. Venue shopping allows the policy actors to shift the debate to a context in which it will be easier for them to draw the attention of the policy makers and to work with policymakers who are sympathetic to the cause.

As this chapter demonstrates, there are a lot of different paths for policymaking. Policy is made by legislatures, executives, bureaucrats, judges, and the public. It is also made at the federal, state, and local levels. Each of these processes is distinct and you could spend a lifetime learning the nuances of a single venue. Hopefully, this chapter has provided you with enough of an overview to appreciate the complexity while also understanding the basic processes.

Although there are many different venues for policymaking, the legislature is the primary place where policymaking should happen…at least according to the U.S. and state constitutions, so we’re going to end this chapter focused on the same institution we started with. I’ve mentioned several types of writing in this chapter (bills, resolutions, committee reports, rules, public comments, opinions) and as we close out this chapter, we’re going to focus on one genre in particular that is important to legislatures.

4.2 What is legislative testimony?

Legislative testimony is written or spoken information that is presented to a legislative committee or subcommittee during their discussion of proposed legislation. It is provided by interest group leaders, legislators, bureaucrats, and the general public for the purpose of informing and persuading legislators. Legislative testimony can be short (only a page or a few minutes) or it can be long (dozens of pages or hours) depending on the situation.

The primary audience for legislative testimony are legislators, in particular, the legislators serving on the committee or subcommittee holding the hearing. Sometimes the primary purpose of the testimony is to inform, but often the primary purpose is to persuade legislators. You can probably picture someone giving legislative testimony in front of a congressional committee, but this also happens at the state level and at local levels of government. The format for speaking at a school board meeting is strikingly similar to speaking in front of congress, though on a smaller scale.

Figure 4.4: Emily Falk ‘22 (speaking, in black) testifies about the Minnesota State Grant in front of the Senate Higher Education Policy and Finance Committee in March 2020

At the highest levels of government, a cabinet secretary might be called to provide testimony to a congressional committee about a particular scandal or a state bureaucrat might be asked to inform a legislative committee about the details of a particular policy. Preparing for these scenarios is beyond the scope of this book. Instead, we’re going to focus on the type of legislative testimony that often comes from interest group leaders and members of the public.

Legislative committees and subcommittees often hold hearings where members of the public and interest groups are invited to provide testimony. Additionally, interest groups and members of the public can send a written copy of testimony to members of the committee.

Preparing effective legislative testimony begins with understanding both the issue and the audience. Knowing something about the issue is important because the committee wants to learn something from the people who testify. This does not mean that you need to be a policy expert in order to testify; in fact, having personal experience with the issue can sometimes be even more powerful than simply knowing a lot about it. Once you know what the topic of the hearing is, you should learn more about the proposed policy and think about your personal connections to the topic. In your testimony, you want to be sure you are communicating accurate information about the topic and that you are giving the legislators a reason to listen to you, either because of your extensive knowledge or because of your compelling personal experience. You also need to think about who you are going to be speaking with. Is the committee friendly to your position? Is the bill’s sponsor on the committee? Has the committee supported similar provisions in the past? Is this a relatively new issue for the committee or have they been dealing with it for a long time?

Now that you know more about the context and audience, you’ll need to consider your position. Unless you are a specialist brought in to provide technical expertise, you are probably going to be speaking to the committee with the goal of persuading them to adopt your position on the proposal. This means that you must have a clear sense of what your position is and that you can articulate that position clearly and support it with empirical and/or anecdotal evidence (using both is best!).

Once you have gathered information about the issue, the proposal, and the committee, and have thought about what you want to say about the topic, you are ready to start writing your legislative testimony. The format of legislative testimony is a cross between a letter, a memo, and a speech.

The top of the page of legislative testimony often looks like a memo format with date, to, from, and subject lines.

The first paragraph is very similar to a legislative letter. The opening line of the testimony should always recognize and thank the chair and ranking member (the top person from the minority party) of the committee. The first paragraph should introduce the speaker. If you are affiliated with an interest group, that is a place to introduce the interest group. This is a good place to explain why you are testifying on this issue. Within the first paragraph you should also clearly state your position on the issue. The goal is that your audience doesn’t have to guess who you are or what you want because you’ve stated it all so clearly.

The body of the testimony is where you will outline your position and present your evidence. Because you are usually speaking legislative testimony, it can be helpful to use some speech writing techniques like signposting. Signposting is when you are very explicit about transitioning between main ideas. For example, you might say something like, “there are three main reasons why this is an important proposal to pass now. First…Second…Third…” This helps your listener follow along with your argument. This is especially true if you are presenting a lot of empirical information. If your evidence is more anecdotal–based on your personal experience–it doesn’t work as well to use signposting, but you can still put some time and effort into thinking about how to most clearly tell your story. It can be most effective if you can combine anecdotal evidence with empirical evidence. Perhaps you have personally experienced something, but you also know that X% of the population has also experienced this thing. Combining empirical and anecdotal evidence puts a face to the statistics.

At the end of your testimony, it is important to restate your position and thank the committee (again) for their time.

Once you have written your testimony, you have options for delivery. You could read the testimony directly from your document. You could also use the document to create a keyword outline and deliver your testimony more extemporaneously. Whichever method you choose, remember that you are likely operating within time limits set by the committee. It is very important that you stay within those time limits, so you should practice your testimony ahead of time to make sure that it fits.

After you’ve given your testimony, members of the committee may ask you questions. The most important thing to remember during this stage is that you should never make up an answer that you don’t know. It’s fine if they ask you a question to which you don’t know the answer; just admit that you don’t know and say that you will find out and get back to them. Then be sure to follow up with them. If there are other witnesses who are providing testimony in the same hearing, it is important to listen to their testimony and the questions they are asked too. That will help you be aware of places where you are in agreement and places where you differ so that you can clarify that for the committee.

Finally, if you aren’t able to provide your testimony in person, you can always send a copy of your testimony to the committee.

Take a look at this sample legislative testimony. Can you spot the stylistic markers that make it a good testimony? Who delivered it and to whom was it delivered? What argument do they make and did they support it with empirical or anecdotal evidence or a mixture of both?

Figure 4.5: Sample legislative testimony by Brenda DeRosas Lazaro ’22. Following graduation from Gustavus, Brenda worked on a legislative campaign and then was hired as a Legislative Assistant at the Minnesota Senate.

Brenda De Rosas Lazaro

Testimony to the House Committee for Higher Education Finance and Policy

January 20, 2020

Madam Chair and members of the committee,

I would like to start off by thanking you for this opportunity to speak to you today.

I am a junior first-generation immigrant and college student at Gustavus Adolphus College. I am majoring in Political Science with a minor in Public Health. I was raised in Albert Lea Minnesota, with two hardworking parents and two younger sisters one aged 12 and other 16.

I am here today to speak on behalf of not only my fellow Gusties, but to provide perspective from some of the most underrepresented groups- immigrants, those of low socioeconomic status, and students of color.

The Minnesota State Grant has provided me the opportunity to access higher education at a great institution like Gustavus. The continuation and expansion of the Minnesota state Grant and financing for higher education institutions are the start of an effort to close the opportunity gap that underprivileged students face.

It is especially important now during the COVID-19 pandemic that we provided the resources for students to attend these institutions to continue to cultivate well rounded citizens who not only fight for themselves but for others.

COVID-19 has disproportionately affected persons of color, by two-fold. Unfortunately, this past May my family experienced COVID first-hand. My mother contracted COVID a week before her birthday. Our community of undocumented, low-income families were taking food off their own table to place it on ours. My mother was recovering for over a month after her intense face to face with COVID-19.

I didn’t know if I was going to be able to pay for books, tuition or even basic necessities come fall. This is a challenge many college students faced this past year because as undergraduate students, our places of employment were not considered essential, our hours were cut, or we were out of work all together.

Fortunately, the Gustavus faculty and staff were willing to help and led me toward the correct resources and lend a helping hand. And for that I have nothing but gratitude.

Attending a four-year private college seemed impossible but Gustavus made it possible for me to be standing here with new goals and aspirations.

Their help wasn’t just in these trying times were learning from home was the new norm, but when the integrity of the DACA program was under attack they were there to grant their full support.

After graduating next year, I intend to work for a non-profit organization that focuses on immigration, public service, and policy to build experience for graduate study in Political Science or Public Health. I hope to help those in my communities, so they don’t have to endure as much as I did.

I do not stand before you for my personal gain, I stand before you for the 12- and 16-year-old that live with my parents with dreams of making history like our new madam vice president did today.

My parents brought me here in pursuit of the American Dream and their daughter speaking to the Minnesota House Committee for Higher Education Finance and Policy is father then they had hoped for and I would like to thank all of you for the opportunity to speak on behalf of first-generation students like myself and to bring the voice of my mother and father to you.

And finally, I would also like to thank you for your efforts and concerns in higher education and the equity thereof. Because without your efforts my dreams would have remained just that, dreams.

4.3 Why do you write?

Figure 4.6: Representative Samantha Vang ‘16

I was born and raised in North Minneapolis to Hmong refugees and am now a long-time resident in Brooklyn Center. I’m a first generation graduate with a Bachelor of Arts in Political Science and Communications Studies from Gustavus Adolphus. Shortly after I graduated college, I ran for Minnesota House of Representatives and became the first Hmong woman to be elected in the MN State House and the second youngest female ever to be elected at the age of 24. I became Chair of the first ever legislative Minnesota Asian Pacific caucus and then Chair of the legislative People of Color Indigenous (POCI) caucus and carried the caucus during a racial reckoning, a civil unrest of George Floyd and Daunte Wright that occurred right in my city. Now I am entering my 3rd term as a State Representative and Chair of the Agriculture Finance and Policy committee.

When I was a recent graduate and first ran for office, it was one of the hardest decisions I had ever made to date. To see myself in a position of power as a young woman of color took tremendous effort from me and my own support system to simply have the confidence to put my name in the hat. I had a hard time seeing myself in that role and asked myself who am I to think I can be responsible for 40,000 people? To see myself in a position of power as a young woman of color took tremendous effort from me and my own support system to simply have the confidence to put my name in the hat. During that time, I was at my lowest point mentally. I had no job, little money, but my community, my campaign team, and my family took my hand and we never looked back. When it’s hard to believe in yourself, it is the people around you who will carry you through. I am so thankful that I’ve been surrounded by people who love and care for me and the community we continue to serve everyday.

As an elected official at the Minnesota legislature, our main task is to bring bills into law. We are also responsible for setting the budget of the state where we make budget decisions on where taxpayer dollars should or should not be spent. There’s also many other things we do on a daily basis, but those are our main constitutional duties. One of the tasks I enjoy doing is providing constituent services. It can range from hearing concerns from constituents, such as expediting a driver’s license renewal, or any requests constituents have for us at the state.

I do a lot of writing from emails to communicate with constituents and staff to media releases with the public. A lot of the time we have staff to help us during any writing process such as turning an idea into a bill or communicating with the public. When I do speeches or prepare for committee hearings, I often write my own.

When I am preparing for a speech, and if I have the time, I will try to prepare a couple of days in advance. I will do some research about the type of event and what type of audience will be in attendance. I like to hand write in a journal first, free flowing initial thoughts into a basic template of introduction, main, and conclusion. I don’t like to speak for very long, so my style is often concise. I will write the main talking point and later add on more detailed sentences. Once I finish with my first draft, I like to wait another day to have a fresh look on the draft and make edits or add additional thoughts. Once I finish with my first draft, I like to wait another day to have a fresh look on the draft and make edits or add additional thoughts. I do all of this in handwriting in a work journal I keep. I don’t make many drafts, probably most I make is 2 and then I rehearse to memorize the speech.

Before I present a bill that I’ve sponsored before a committee, I prepare notes, talking points, and sometimes include background research to provide context and the significance of the bill. I also prepare remarks that may answer members of the committee who may oppose or have concerns. I will also have testifiers who will speak in support of the bill and they usually prepare their own remarks.

I wish I had a different mindset about me as a writer in the beginning so I would have more experience on how to make my writing voice effective. I grew up insecure in writing since English is a second language and my vocabulary was limited. It didn’t excel until my college years. My mindset was more concerned with always trying to sound like any other good writer, but not about me as a writer on how to best convey my thoughts to the reader. Part of my journey as a writer was learning about my style and accepting that it’s okay to speak in the way that I speak because as it turns out, people actually understand me as the writer better that way.

4.4 What comes next?

Now that we have a basic understanding of the policymaking process as it moves through the legislative, executive, and judicial branches, it is time to turn to one of the most important questions addressed in this book: why does policy look this way? The next chapter will dig into the question of policy design, focusing on the selection of policy tools and causal stories. I’ll introduce the Social Construction Theory of Target Populations, which provides a theoretical explanation of policy design.

Questions for discussion

- What policymaking process are you most familiar with? How did you learn about it? What policymaking process are you least familiar with? What questions do you still have about how it works?

- Should the executive branch play any formal role in actually making policy? What are the arguments for and against executive branch participation in policymaking?

- Should the judicial branch play any formal role in actually making policy? What are the arguments for and against judicial branch participation in policymaking?

- Should Minnesota adopt an initiative process? Should the federal government adopt an initiative process?

Administrative Procedure Act : This law outlines the guidelines for how agencies must go about the work of developing the rules needed to implement legislation or to regulate the aspect of activity over which it has been given authority.

Appropriations process : The process by which Congress approves spending money on policies they have authorized.

Authorizing bills : Bills that create, modify, or end a policy.

Bill : A legislative proposal to create, amend, or remove policy language.

Civil trial : A legal hearing that involves a dispute between two individuals or organizations. Penalties for a civil trial are financial only and don’t result in a criminal conviction.

Committee : A formal group of legislators who have jurisdiction over a specific policy topic. Committees study and debate bills, hold hearings to learn more about them, propose modifications to bills, and make a recommendation to the full chamber.

Committee report : A document produced by a committee that explains the purpose of a bill and outlines the reasons the committee supports it (and, when applicable, why the minority opposes it) and how it will change existing law.

Concurrent resolution : (designated H. Con. Res. in the House and S. Con. Res in the Senate) Used to change rules that apply to both chambers of Congress or express the sentiments of both chambers.

Conference committee : A committee that includes representatives from both chambers (House and Senate) with the goal of reaching an agreement between the two versions of the bill. Any agreement reached by a conference committee must be ratified by a majority vote in both chambers.

Congressional Record : A verbatim record of debates and other activity that happens on the floor. In Congress, members can insert text into the Congressional Record, which makes it look like they made a speech on the floor of the chamber even when they didn’t.

Cosponsor : One or more members of the legislature that formally express support for a bill by adding their name to the bill as a cosponsor.

Criminal trials : These trials involve a person being accused of committing a crime against society as a whole and so the case is brought by the government (via a prosecutor) against the person accused of the crime.

Executive order : A statement issued by a president that creates or modifies laws or the procedures of the federal government independently of congressional action.

Filibuster : Occurs when one or more members of the Senate prolong debate on proposed legislation to delay or prevent a decision.

Final Rule : Published in the Federal Register as a codification of an agency’s interpretation of how to best implement a policy. A final rule includes a section that describes the problem that the rule is addressing and identifies the specific statute that gives it authority to act.

Hearing : A meeting held by a congressional committee in which they invite people to provide testimony and answer questions from committee members.

Initiative process : Allows individual citizens or groups to propose a new law and, in some cases, a constitutional amendment, which is then voted on by citizens in an election.

Interpretive rules : This type of rules do not require notice-and-comment and can be issued without public input. Interpretive rules do not have the force of law but explain the agency’s interpretation of laws or regulations.

Joint resolution : (designated H.J. Res. in the House and S.J. Res. in the Senate) Similar to a bill. Joint resolutions can be used to appropriate money for a particular purpose, requiring approval by both chambers of Congress and the president. They can also be used to propose amendments to the Constitution.

Judicial review : The power of the U.S. Supreme Court to determine whether an action taken by the government is consistent with the U.S. Constitution.

Jurisdiction : The set of topics that a committee oversees.

Markup hearing : A hearing in which a legislative committee or subcommittee will move line by line through the proposal, making changes, called amendments.

Multiple referral : The process of sending a bill to more than one committee at a time for review.

Omnibus bill : A massive bill that packages a lot of smaller bills together.

Plea deal : An agreement between a person accused of a crime and the prosecutor in which the defendant pleads guilty in exchange for a lighter sentence.

Pocket veto : When there are less than ten days left in a current congress but the President does not sign or veto the bill, the bill does not go into effect. This is called a pocket veto because the President did not have to take proactive action to veto the bill but rather just put it in his pocket to die.

Precedent : Making a judicial decision so that it conforms to decisions reached in prior similar cases.

Recorded vote : When a chamber of Congress records the names of people who voted for and against a proposal.

Referendum : A process in some states in which a state legislature passes a law but places it on the ballot for voters to either uphold or repeal.

Regulation : A statement issued by a government agency, board, or commission that has the force and effect of a law passed by Congress.

Resolution : Similar to a bill but used to express ideas, set internal rules for Congress, or propose constitutional amendments.

Rulemaking : The process of creating rules and regulations by bureaucratic agencies as they work to implement laws passed by Congress.

Rules Committee : A committee in the House of Representatives that establishes the guidelines for debating proposals in the House.

Signing statements : Written documents that are issued when presidents sign new policies into law. Presidents sometimes use these to call out aspects of the law that they disagree with and plan to ignore in the enforcement process.

Simple resolution : (designated H. Res. in the House and S. Res. in the Senate) Used to express the sentiment of one chamber.

Sponsor : The Senator or Representative who introduces a bill or resolution.

Street level bureaucrats : The government employees who work on the front lines of providing direct services.

Subcommittee s: A subsection of a committee that focuses on an even more specific aspect of the policy area. Like committees, subcommittees can hold hearings and propose amendments. Any decisions made by a subcommittee must be approved by the full committee.

Testimony : Written or spoken information that is presented to a legislative committee or subcommittee during their discussion of proposed legislation.

Unanimous consent : The Senate requires approval from all members to act, and so it operates under a series of unanimous consent agreements to conduct its business. Unless a Senator objects, the Senate continues with its business. A Senator who strongly objects might consider starting a filibuster.

Vacating the rule : A declaration by a judge that an administrative rule is void or unenforceable.

Venue shopping : The process of proactively seeking out a more favorable venue for political action.

Veto : An action taken by a President to oppose a bill passed by Congress.

Voice vote : A vote taken in Congress in which members express their support or opposition to the proposal verbally without recording how individual members voted.

Additional Resources

Federal Statutes: A Beginner’s Guide https://guides.loc.gov/federal-statutes

Legislative Histories of Selected U.S. Laws on the Internet: Free Sources https://www.llsdc.org/legislative-histories-laws-on-the-internet-free-sources

How to Trace Federal Regulations: A Beginner’s Guide https://guides.loc.gov/trace-federal-regulations

Access proposed regulations and submit comments: https://www.regulations.gov/

Thanks for reading this chapter. The book in which this chapter sits is a work in progress and I welcome feedback and suggestions for improvement. If you notice incorrect or out of date information, please let me know using the feedback form linked below. If something was particularly helpful to you, I’d also love to hear about it. If you are a faculty member or public policy practitioner who is interested in collaborating on this project, you can also use this feedback form to contact me. ~Kate

Feedback form: https://forms.gle/LKBykHHRLe2kNW2AA

- Eric (Halvorson) Fowler ‘13 is now a Senior Policy Associate for an advocacy group called Fresh Energy that advocates for Minnesota to transition to clean energy sources. ↵

- Barbara Sinclair, Unorthodox Lawmaking ↵

- Nebraska did have a bicameral legislature at one point, but it changed to a unicameral system in 1937 because lawmakers thought it would save the state money and be more representative of the people. You can read more about it here if you are interested: https://nebraskalegislature.gov/education/lesson3.php#:~:text=Critical Thinking Exercise-,U.S. Sen.,than a two-house legislature. ↵

- Brian Wolfman and Bradley Girard, Argument preview: The Administrative Procedure Act, notice-and-comment rule making, and “interpretive” rules, SCOTUSblog (Nov. 26, 2014, 10:13 AM), https://www.scotusblog.com/2014/11/argument-previewthe-administrative-procedure-act-notice-and-comment-rule-making-and-interpretive-rules/ ↵

- “Administrative Procedure Act,” National Archives and Records Administration (National Archives and Records Administration), January 25, 2023, https://www.archives.gov/federal-register/laws/administrative-procedure/553.html. ↵

- Information in this section is drawn from several sources: Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, https://www.reginfo.gov/public/jsp/Utilities/faq.jsp; Office of the Federal Register, A Guide to the Rulemaking Process https://www.federalregister.gov/uploads/2011/01/the_rulemaking_process.pdf; ↵

- Coglianese, Cary, “Assessing Consensus: The Promise and Performance of Negotiated Rulemaking” (1997). Duke Law Journa l, Vol. 46, Pg. 1255, 1997, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=10430 ↵

- Congressional Research Service, “The Congressional Review Act (CRA): Frequently Asked Questions” https://sgp.fas.org/crs/misc/R43992.pdf ↵

- “The Rulemaking Process - Federal Register,” accessed 1AD, https://www.federalregister.gov/uploads/2011/01/the_rulemaking_process.pdf, 11. ↵

- Michael Lipsky, Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1980). ↵

- Michael Lipsky, Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1980), 3. ↵

- Frank R. Baumgartner, Derek A. Epp, and Kelsey Shoub, Suspect Citizens: What 20 Million Traffic Stops Tell Us About Policing and Race (United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press, 2018), 2. ↵

- Michael Lipsky, Street-Level Bureaucracy: Dilemmas of the Individual in Public Services (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1980), 6. ↵

- Congressional Research Service, Executive Orders: An Introduction, March 29, 2021,https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46738; American Bar Association, “What is an Executive Order?, January 25, 2001, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_education/publications/teaching-legal-docs/what-is-an-executive-order-/ ↵

- History.com Editors, “Japanese Internment Camps,” History.com (A&E Television Networks, October 29, 2009), https://www.history.com/topics/world-war-ii/japanese-american-relocation#:~:text=Japanese internment camps were established,be incarcerated in isolated camps. ↵

- Congressional Research Service, Todd Garvey, “Presidential Signing Statements: Constitutional and Institutional Implications” January 4, 2012, https://sgp.fas.org/crs/natsec/RL33667.pdf ↵

- “Supreme Court of the United States,” accessed January 25, 2023, https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/21pdf/20-1530_n758.pdf. ↵

- G. Alan Tarr, Judicial Process and Judicial Policymaking , 7th edition (New York: Routledge, 2019). Tarr also identifies common-law policymaking, but this form of judicial decisions is not as relevant to the policymaking process. ↵

- Emanuella Evans, “Jury Trials are Disappearing. Here’s Why”, Injustice Watch , February 17, 2921. https://www.injusticewatch.org/news/2021/disappearing-jury-trials-study/ ↵

- The prosecutors won’t appeal a loss because of the Constitution’s prohibition on double jeopardy, or being tried twice for the same crime. ↵

- G. Alan Tarr, Judicial Process and Judicial Policymaking , 7th edition (New York: Routledge, 2019). ↵

- Occasionally, all of the judges from an appellate court will review the case. This is called an en banc session. ↵

A legislative proposal to create, amend, or remove policy language.