A Guide To Some Of Brian Doyle's Best Works

Brian Doyle was one of Oregon's most prolific authors. His 28 published works span a variety of topics, from essays on the Pacific Islands and spirituality to novels which featured non-human characters.

Oregon Art Beat

Related: Oregon Author Brian Doyle Dies At 60

Award-winning Oregon Author Brian Doyle died at his home Saturday after a months-long battle with cancer. Doyle, 60, was a prolific author of essays and novels on a variety of subjects. His 28 published works put him in a category of extraordinarily prolific writers. Once he got started, there was no stopping him. He sometimes published two, three, even four books in one year. A fearlessly inventive storyteller with a confident prose style, Doyle published novels, essays, short stories and more. One gets the sense Doyle’s writing process opened door after door in a sprawling mansion of ideas. Here are a few titles to get you started.

"God is Love: Essays from Portland Magazine" (editor, December 2002)

An instructive survey of voices and ideas that galvanized and influenced Doyle, these are among the essays he curated as editor of the University of Portland’s flagship alumni magazine — a post he held for 26 years. Andre Dubus, Barry Lopez, Cynthia Ozick, Terry Tempest Williams, and others weigh in. You’ll find struggle here, but also celebrations of everyday sacraments of family and community that lay so close to Doyle’s heart. Publishers Weekly writes, “This collection reads like a mesmerizing love song to the complex and sometimes unwieldy religion of Christianity.”

"Mink River" (October 2010)

A lovingly-imagined Oregon coastal town of Neawanaka is the tapestry in which Doyle invents a cast of fascinating characters, celebrating the unsung dramas of life in a faded timber town. Author David James Duncan, who was good friends with Doyle, praises its “hauntings and shadows, shards of dark and bright, usurpations by wonder, lust, blarney, yearning, are coast-mythic in flavor but entirely bardic at heart. I've read no Northwest novel remotely like it and enjoyed few novels more.”

"The Plover" (March 2015)

Hobo sailor Declan O’Donnell’s sails solo across the Pacific, fighting a losing battle to maintain a sense of solitude. Doyle gives us an irresistible cast, including the goofy, cantankerous Declan, a mysterious child snared in the grip of grief, pirates, Polynesian bureaucrats, and more. Doyle’s longtime friend Hob Osterlund writes, “Brian has a magic ability to understand animal voices, worries, loves, fears and appetites. Somehow, word by word, run-on sentence by run-on sentence, we all come to love each other more, all because of this one man's passion for small honest stories.”

"Children and Other Wild Animals" (October 2014)

An exercise in Doyle’s great range, these stories chronicle encounters with all manner of species. Some work was previously unpublished; other essays appeared first in “The Sun,” “Utne Reader,” “High Country News,” and “Best American Essays.” The Iowa Review took the occasion of this book to proclaim Doyle “a Townes Van Zandt of essayists known by those in the know.”

"Martin Marten" (April 2016)

Interwoven stories from the lives of two youngsters living on the slopes of Mount Hood: a young teenager named Dave who is on the cusp of leaving his bucolic forest life behind, and Martin, a pine marten ( martens are weasel-like mammals ) on his own adventure. When this novel took the YA prize at the 2016 Oregon Book Awards, judge Deb Caletti wrote, "Doyle has crafted a classic — a timeless book that lets a reader disappear into a full and gentle world."

“Chicago, A Novel” (March 2017)

One part coming-of-age tale, one part love note to one of America's great cities. Kirkus Reviews writes , "Page follows page of evocative writing as Doyle celebrates 'the shopkeepers and cops and nuns and bus drivers and carpenters and teachers who composed the small vibrant villages that collectively were the real Chicago.'"

“The Adventures of John Carson in Several Quarters of the World: A Novel of Robert Louis Stevenson” (March 2017)

A fascinating premise: Doyle imagines a young Robert Louis Stevenson killing time in San Francisco, captivated by a seasoned sailor’s tales of traveling the world. In doing so he contemplates the power of stories and the legacy of one of the world’s great literary lights. Jenny Davidson, writing for The New York Times Book Review, declares, “I doubt Doyle would object to my suggestion that for those who don’t already know Stevenson, his own stories will be a better place to start than this book. But Doyle offers a salutary reminder of the greatness of the tales spun by Hawthorne, Kipling, Conrad, Stevenson and others of that ilk, and I was won over despite myself by his loving reconstruction of an era of storytelling now lost.”

OPB’s First Look newsletter

Streaming Now

Wait, Wait...Don't Tell Me!

Advertisement

Supported by

Brian Doyle Noticed the Little Things. His Book Reminds Us We Should Too.

- Share full article

- Apple Books

- Barnes and Noble

- Books-A-Million

When you purchase an independently reviewed book through our site, we earn an affiliate commission.

By Margaret Renkl

- Dec. 3, 2019

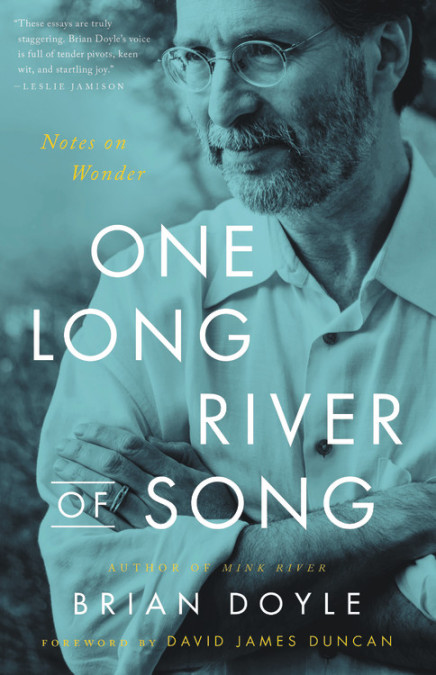

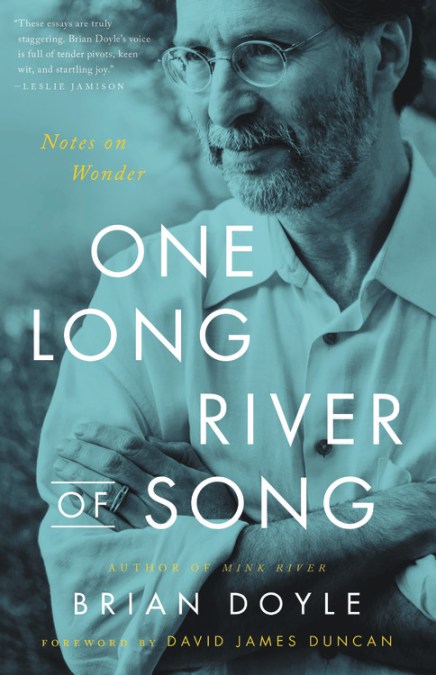

ONE LONG RIVER OF SONG Notes on Wonder By Brian Doyle

If you are in love with language, here is how you will read Brian Doyle’s posthumous collection of essays: by underlining sentences and double-underlining other sentences; by sometimes shading in the space between the two sets of lines so as to create a kind of D.I.Y. bolded font; by marking whole astonishing paragraphs with a squiggly line in the margin, and by highlighting many of those squiggle-marked sections with a star to identify the best of the astonishing lines therein; by circling particularly original or apt phrases, like “this blistering perfect terrible world” and “the chalky exhausted shiver of my soul” and “the most arrant glib foolish nonsense and frippery”; and, finally, by dog-earing whole pages, and then whole essays, because there is not enough ink in the world to do justice to such annotations, slim as this book is and so full of white space, too.

Brian Doyle died in 2017 at 60 of complications from a brain tumor. He left behind seven novels, six collections of poems and 13 essay collections. The whole time he was writing, he was also working full time as the editor of Portland Magazine.

[ This collection was one of our most anticipated books of December. See the full list . ]

It’s an amazing creative output, but Doyle was never famous. In 2012 The Iowa Review called him “a writer’s writer , unknown to the best-seller or even the good-seller lists, a Townes Van Zandt of essayists, known by those in the know .” If there is a God — and Doyle fervently believed there is — “One Long River of Song” will change all that. This book is what Van Zandt’s greatest hits would look like had he lived to be 60, and if every song on the record hit the bar set by “ Pancho and Lefty .”

Doyle was a practicing Catholic who wrote frequently about his faith, but this book carries not a whiff of sanctity or orthodoxy. The God of “One Long River of Song” is a kindergartner wearing a stegosaurus hat, a United States postal worker with preternatural patience (“God was manning the counter from 1 to 5, as he does every blessed day”), the “coherent mercy” that cannot be apprehended but may be perceived by way of “the music in and through and under all things.”

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

An introduction to the brave, joyful, and prolific work of Brian Doyle

A Book of Uncommon Prayer: 100 Celebrations of the Miracle & Muddle of the Ordinary

Mink River: A Novel

A Shimmer of Something: Lean Stories of Spiritual Substance

Grace Notes: true stories about sins, sons, shrines, silence, marriage, homework, jail, miracles, dads, legs, basketball, the sinewy grace of women, bullets, music, infirmaries, the power of powerlessness, the ubiquity of prayers, & some other matters

Martin Marten: A Novel

One Long River of Song: Notes on Wonder

Brian doyle: a complete bibliography.

About the author

Jeffrey munroe, you may also like.

What we’re reading this month: August 2024

Ethan and Maya Hawke hope ‘Wildcat’ will attract truth-seekers

Maggie Rogers’ ‘Don’t Forget Me’ keeps dreaming

Add comment, what’s trending.

A reflection for the nineteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time

What is the prophecy of St. Malachy?

For this sister, an accident led to a deeper understanding of Christ

Brian Doyle’s diverse essays reflect his love affair with words . . . and God

Reviewed by Sister Mary Core, OSB

As I read “One Long River of Song,” a collection of Brian Doyle’s many essays, I wished I had personally known this man who had a “love affair” with words. In this one book alone, Doyle spews out every emotion imaginable, while writing in a style uniquely his own.

The title is so right, for each essay rolls along like water rippling over the rocks of a mountain spring: bright, bubbly, singing, raging and rushing forward, and filled with life ! Doyle plays with the words, as in: “extraordinary ordinary succinct ancient naked stunning perfect simple ferocious love.” (page 12) As if, “one word won’t do, so here are 10 more.”

His diverse essays on 9-11 (Leap) and on a one-armed doll (Joey’s Doll’s Other Arm) both become, as do all his essays, a forum to speak of love and goodness and the mystery of God.

THE HAND OF GOD IN EVERYTHING

Doyle is an unabashed Catholic, whose writing is a cross between Sacred Scripture, the Catechism, poetry, the ripple of a mountain stream and the hum of a busy, bumble bee.

Brian Doyle sees in everything — the hand of God. Each essay beckons the reader to look more deeply into the mystery of life. Each essay, often based on a simple, everyday occurrence, is viewed like a multi-faceted gem with a plethora of truths to tell.

Brian Doyle was a consummate storyteller who had an ability, a marvelous gift, for turning a word or words into magic. In the essay “His Last Game,” a simple drive to the pharmacy becomes an account of all that is experienced along the way as well as experiences of years past.

A very short and powerful essay called “100th Street” recalls the gratitude and respect we all felt for those who put their lives on the line on 9/11.

A trip to the Post Office in “God Again” is an encounter with God in the guise of the patient Postal Worker behind the counter.

And then there are the few short lines of “Joey” which speak of a loving son putting on his father’s socks during his illness with “The Thing.”

ESSAYS THAT OPEN HEARTS, MINDS

In these often riveting essays Brian Doyle was able to write of family and friends, of nature, of human nature, of things small and insignificant, as well as large and looming. Each essay drew me in and left me feeling full.

Because it is a book of essays, I could read and savor a one-page story, — or linger over a much longer discourse on his children. No matter the length, each essay was on its own, a piece of wisdom, a period of laughter, a sobering thought, a delight to read, an “ah-ha” moment.

Brian Doyle was a relatively unknown author. His style of writing was unique and reflected his love of life, the written word, and his deeply rooted faith. Doyle said he loved to “catch and share” stories. “What could be holier and cooler than that?” he told The Oregonian. “Stories change lives; stories save lives. . . . They crack open hearts, they open minds.”

“One Long River of Song” did that for me. I hope it will do that for you.

Brian Doyle died before “One Long River of Song” was published. He passed away in May of 2017 from brain cancer. The book, a compilation of his many essays, was published in 2019 by his wife, Mary Miller Doyle.

I believe, over time, Brian Doyle’s writing will become more well-known and beloved. It is sad that his gift as a “tinker of words” ended too soon. “One Long River of Song” was my first encounter with the writings of Brian Doyle. It will not be my last.

MORE FROM BRIAN DOYLE

Other publications by Brian Doyle include:

- Doyle, Brian J. The grail: a year ambling & shambling through an Oregon vineyard in pursuit of the best pinot noir wine in the whole wild world. Corvallis: Oregon State Univ. Press, 2006.

- Mink River . New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2010.

- Bin Laden’s bald spot & other stories. Pasadena, Calif.: Red Hen Press, 2011.

- The wet engine: exploring the mad wild miracle of the heart. Corvallis: Oregon State Univ. Press, 2012.

- Children & other wild animals . Corvallis: Oregon State Univ. Press, 2014.

- Martin Marten. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015.

- The Plover . New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2015.

- Chicago . New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2016.

- The adventures of John Carson in several quarters of the world: a novel of Robert Louis Stevenson . New York: St. Martin’s, 2017.

Sister Mary Core, OSB

SISTER MARY CORE, OSB, is a member of the Sisters of St. Benedict of St. Mary Monastery in Rock Island. She leads a woman’s book club for St. Maria Goretti Parish, Coal Valley, and Mary, Our Lady of Peace Parish in Orion.

JOIN THE DISCUSSION! Want to discuss this book or others with fellow reading enthusiasts? Join The Catholic Post’s Book Club on Facebook or on Instagram !

Welcome to Eureka Street

- INTERNATIONAL

ARTS AND CULTURE

- Eureka Street Plus

- Environment

- Faith Doing Justice

The Storycatcher - 17 of the best of Brian Doyle

- 30 May 2017

Brian Doyle, editor of Portland Magazine at the University of Portland, author most recently of the essay collection Grace Notes, and a long time contributor to Eureka Street, died early Saturday morning 27 May 2017 following complications related to a cancerous brain tumour, at the age of 60. Here we present, in no particular order, a collection of some of Brian's best pieces from the past 12 years.

When we were 17 and 18, the thought of joining the Navy was both fascinating and chilling, for the war in Vietnam was still seething, and all of us had registered for the draft, as required by law. We crowded around a television one night in March to watch the draft lottery, and some had crowed when their numbers were drawn near the end, and others like me were stunned and frightened when our numbers were drawn early. All the rest of my life I will remember hearing my number called first among all my friends, and the way they turned to me with complicated messages written on their faces, and the way one boy laughed and started to rag me and then stopped as abruptly as if someone had punched him, which maybe someone had.

Also I did for years take my lovely bride for granted, more than a little; I did think that being married meant that she would never leave me and I could drift into a gentle selfishness that she would have to endure because she had sworn in a church before many witnesses to be true in good times and bad, in sickness and health, to love and honour you all the days of my life, I carry those words in my wallet; but I did not look at them enough and contemplate them and mull over them and take them deep into my salty heart and consider what they asked me to do and be, and there came dark years, and I was in no small part responsible for their bleakness and pain.

Subscriber login

Looking for thought provoking articles? Subscribe to Eureka Street and join the conversation.

| Public articles |

| Eureka Street weekly newsletter |

| Eureka Street Plus |

| Essays |

| Weekly talking points |

| Events |

| Book reviews |

| Roundtables |

| Archives |

Passwords must be at least 8 characters, contain upper and lower case letters, and a numeric value.

Eureka Street uses the Stripe payment gateway to process payments. The terms and conditions upon which Stripe processes payments and their privacy policy are available here .

Please note: The 40-day free-trial subscription is a limited time offer and expires 31/3/24. Subscribers will have 40 days of free access to Eureka Street content from the date they subscribe. You can cancel your subscription within that 40-day period without charge. After the 40-day free trial subscription period is over, you will be debited the $90 annual subscription amount. Our terms and conditions of membership still apply.

- Craft and Criticism

- Fiction and Poetry

- News and Culture

- Lit Hub Radio

- Reading Lists

- Literary Criticism

- Craft and Advice

- In Conversation

- On Translation

- Short Story

- From the Novel

- Bookstores and Libraries

- Film and TV

- Art and Photography

- Freeman’s

- The Virtual Book Channel

- Behind the Mic

- Beyond the Page

- The Cosmic Library

- The Critic and Her Publics

- Emergence Magazine

- Fiction/Non/Fiction

- First Draft: A Dialogue on Writing

- The History of Literature

- I’m a Writer But

- Lit Century

- Tor Presents: Voyage Into Genre

- Windham-Campbell Prizes Podcast

- Write-minded

- The Best of the Decade

- Best Reviewed Books

- BookMarks Daily Giveaway

- The Daily Thrill

- CrimeReads Daily Giveaway

On Brian Doyle’s Mystical, Genre-Exploding Work

David james duncan remembers the late great writer who tried to "stare god in the eye".

My great friend Brian Doyle—”BD” to me for a quarter century, so pardon my addiction to calling him that still—was always an unusually fast and proficient writer. But from the 2010 publication of his first novel, Mink River, until his fatal brain-tumor diagnosis late in 2016, he caught fire. During that period he published two collections of short stories, four collections of the prose/poem hybrids he dubbed “proems,” seven collections of the power-packed short memoirs, epiphanies, and reflections he too reductively called simply “essays,” and five more novels. Over the same span he edited Portland magazine, under BD’s tenure the most heavily awarded alumni magazine in the country as he helped resurrect, for Americans, the ancient and invaluable genre we now call “spiritual writing.”

It strains my sense of the possible to add that BD was simultaneously giving public readings and talks by the dozens, writing recommendation letters, visiting grade schools, high schools, colleges, and book groups to regale what amounted to thousands of people of all ages, writing rivers of the more entertaining emails on the planet, and privately mentoring, entertaining, and consoling more people than we will ever know. Like any good man or woman dedicated to compassion in a post-fact, post-democratic corporate state, he also kept busy annoying the hell out of a few worthy enemies. I can’t resist adding that the typing portion of all these achievements was accomplished with precisely two fingers. I challenge the world’s pianists to see what they can do with the same two fingers.

Brian’s nonfiction appeared in scores of America’s finest magazines, won four Pushcart Prizes, and was regularly reprinted in every major nonfiction anthology in the country—including seven times in Best American Essays. His writing won many more honors than I have space to list here. But the responses from other writers, many of them renowned, are so remarkable I must include a few.

The great Ian Frazier said that Brian “wrote more powerfully about faith than anyone in his generation.” The peripatetic and contemplative Pico Iyer: “Almost nobody has written with the joy, the galloping energy, the quiet love of conscience and family and what’s best in us, the living optimism.” Renowned albatross savior Hob Osterlund: “He knew the strength of women without reduction, without fear or pretense, without the need to saint.” The late Mary Oliver on his essays: “They were all favorites.” (And for a Catholic writer to have his work chosen for Best American Essays by Mary Oliver and by the famous atheist Christopher Hitchens bespeaks BD’s extreme range of appeal.) “We love him,” writes philosopher and earth defender Kathleen Dean Moore:

Brian gets fan mail, sure, but also love letters. . . . People love his work, but more than that, they truly love him. We love him because he spreads his arms and lets us into his amazing mind and boundless heart. . . .The moments he shares with us sing of adoration for all the whistling, sobbing, surging creation. . .[and] by opening our hearts without breaking them he answers our deepest yearning for meaning. Which is joy. Which is gratitude.

How in heaven’s name did one man win such strikingly intimate praise? I would suggest that the extreme intimacy of his nonfiction was not only delightful but highly contagious. BD saw his stories as “diving boards, not news reports.” He was interested less in “ostensible fact and nominal accuracy” than in “the bends and layers and implications and insinuations and shimmers of memory.” Within those shimmers, he said, were “the seeds of stories to which other people can connect.”

A far less subtle feature of Brian’s sentence-making: when he intuited the approaching roar of a whitewater rapid in his imagination, he paddled steady on, refusing to portage round even the wildest water. The prose that resulted made timid readers feel as though they’d been thrown into a kayak and sent careering down a literary equivalent of Idaho’s Payette River during spring runoff.

But sentences that alarm the timid by awakening them to the wilder possibilities of language are heightened , not inept. BD played fast and loose with sentence length, rhythms, grammar, alliteration, and diction to disburden a heart and mind burgeoning with empathy, quickness, joy, wit, and love of “the sinuous riverine lewd amused pop and song of the American language.” Calling a foul on such phrases is like disallowing certain three-point shots of BD’s Golden State Warrior hero, Steph Curry, because they were launched so ridiculously far from the basket. If the ball goes through the hoop and if the sentence sings, both of them count, and I’m giving BD himself the last word on this matter, his ten exclamation points included:

From: Doyle, Brian

Subject: a ha!!!!!!!!!!

Date: January 2, 2015 at 11:34:43 AM MST

To: David Duncan

Have you ever paid attention to Tolstoy’s language? Enormous sentences, one clause piled on top of another. Do not think this is accidental, that it is a flaw. It is art, and it is achieved through hard work.

–Anton Chekhov

Brian Doyle lived the pleasure of bearing daily witness to quiet glories hidden in people, places, and creatures of little or no size, renown, or commercial value, and he brought inimitably playful or soaring or aching or heartfelt language to his tellings. When he finished a nonfiction gem he stacked it in his study until he had built up a modest but serviceable book manuscript, which he mailed off without fuss, usually to very small religious publishers.

Many of BD’s friends, myself included, felt that by scattering his best nonfiction through thirteen modest volumes over the years, he prevented his nonfiction from winning the national repute it deserved. This, coupled with his financial fears for his family after his tumor was diagnosed, is why, shortly after his first devastating brain surgery, I asked BD’s permission to consolidate, in a single volume, the kind of nonfiction that earned the extreme praise I’ve quoted from friends, fans, and editors of magazines, with all proceeds to go to his family. Brian did not say yes. He said, “Sweet Jesus, YES! . . . Take whatever you want and tell whatever stories you want.”

With that blessing in hand, I set about assembling a collection with two magnificent co-editors: the editor-in-chief of Orion magazine, H. Emerson (Chip) Blake, and the writer Kathleen (Katie) Yale. BD’s nonfiction appeared more than any other writer’s in Orion , and Chip and I had worked together on my Orion writing for years. Katie also worked for Orion, including on many of the BD pieces, and she knew his work more widely and deeply than Chip and I did, making her the perfect guide in our efforts. To commune with our friend on this project became a joy to all three of us.

Speaking of my own friendship with Brian: when we met 25 years ago we each experienced, without overtly acknowledging it, a flame in each of us that we could always find burning in the other; a flame we both held to be inextinguishable. We recognized our shared willingness to speak of almost anything we perceived as spiritual truth.

We also loved, during our afternoon work doldrums, to share stuff and nonsense of no redeeming social or spiritual value whatsoever. In response, for instance, to a random baseball note from me about how terrifying it must have been for batters to face the six-foot-ten-inch pitcher Randy Johnson, whose wingspan was so wide and fastball so fast he seemed to reach out and set his pitches in the catcher’s mitt by hand, BD instantly replied that Johnson towered atop a mound “like a stork on acid,” whereas Roger Clemens, since our topic was terror, “ hulked on the mound, like a supersized wolverine with hemorrhoids.” I received 530 such emails and 200 snail-mail notes and missives from BD in our last two years alone, and sent back close to the same. We shot “riverine lewd amused pops and songs” back and forth the way tournament table tennis players exchange shots: for the high-speed joy of it.

That joy was so important to us both that, a few weeks after BD’s death, it felt perfectly natural to sit down and write him yet another letter. In this one I recalled an exchange, via our usual email ping-pong, in which we marveled that the bodies of trees are built by their downward hunger for earth and water and by their upward yearning for light. How wonderful, we agreed, that these paradoxical aims, instead of tearing a tree in two or causing it to die of indecision, cause it to grow tall and strong. And just as wonderful, I wrote to my flown friend, is how, “during the tree’s afterlife, its former hunger and yearning transmogrifies into the enduring structural integrity known as wood. Wood is a tree’s life history become something so solid that we can hold it in our hands. This is not just some lonely cry or mournful eulogy. Right here in the world where every living thing dies, a fallen tree’s integrity remains so literal that if a luthier adds strings to it, we can turn the departed tree’s sun-yearning and thirst-quenching into the sounds we call live music. And if a seeming lunatic smashes wood’s integrity to a pulp, then makes that pulp into paper, our ink can bring to life stories that multitudes can perform like symphonies in the sanctums of their very own depths and heights.”

It’s a great solace to me to imagine how many readers have done exactly that with Brian’s stories, and how many more will have that experience in this book.

In a tribute in Christian Century , Jonathan Hiskes quotes Brian calling his writing “the attempt to stare God in the eye.” As BD’s spiritual intimate over his last six years, I feel this touches the very heart of his aim. Brian’s work, Hiskes writes,

was a mystical project born of both joy and desperation.… The whirling adjectives, aphorisms, metaphors and paradoxes were his method of using every tool he could to excavate the rich seams of the examined life. He wanted more than to stare God in the eye. He wanted to tell God a few things, and listen too. I picture him as a songwriter-king dancing before his Lord, pouring out words, intermingling praise, grief, fury and laughter. The audacity makes me cringe. Then it draws me in.

Me too. Brian was a born cultural Catholic who cheerfully observed the rites of his inherited tradition. He also, sometimes audaciously, challenged his tradition, and he and I often whispered of our reverence for certain anything-but-orthodox humans and mystical texts. Three such for him were His Holiness the Dalai Lama, Thomas à Kempis’s The Imitation of Christ , and the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas , in which Jesus’s mysticism is so overt it’s impossible for the Church to apply it to imperialistic ends. Three such for me are the excommunicated mystical genius Meister Eckhart, the thirteenth-century Zen master Eihei Dogen, and that same Gospel of Thomas .

During his final years, BD bravely bore intimations of an early departure from this life. During the same years he experienced ever more frequent visitations of what I can only call epiphanic joys. In the last lines of his last book, Eight Whopping Lies and Other Stories of Bruised Grace , BD summons his combined desperation and joy when he does not merely quote but lives à Kempis’s recommended imitation, making Jesus’s words in the Gospel of Thomas his own, praying to become, as a posthumous mystery, an unending prayer for his family. What greater gift can a mortal father possibly offer?

“We’re only here for a minute,” Brian once reminded us. “We’re here for a little window. And to use that time to catch and share shards of light and laughter and grace seems to me the great story.” How supreme he was at telling that story, and what a marvelous companion he was to so many. “I want to write to you like I’m speaking to you,” he said. “I would sing my books if I could.”

I say he could, and he did.

Watching Brian’s heart songs pour out, relishing his whitewater sentences, too, I witnessed a daring writer and friend embodying the sublime paradox that Dogen described in these words: “The path of water is not noticed by water, it is realized by water. . . .To study the way is to study the self, to study the self is to forget the self, to forget the self is to awaken into the ten thousand things.” As much as any man or woman I’ve ever known, Brian James Patrick Doyle reveled in the act of awakening into the ten thousand things.

__________________________________

Brian Doyle’s One Long River of Song: Notes on Wonder is out now from Little Brown.

- Share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Google+ (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Tumblr (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pocket (Opens in new window)

David James Duncan

Previous article, next article, support lit hub..

Join our community of readers.

to the Lithub Daily

Popular posts.

Follow us on Twitter

26 Books From the Last Decade that More People Should Read

- RSS - Posts

Literary Hub

Created by Grove Atlantic and Electric Literature

Sign Up For Our Newsletters

How to Pitch Lit Hub

Advertisers: Contact Us

Privacy Policy

Support Lit Hub - Become A Member

Become a Lit Hub Supporting Member : Because Books Matter

For the past decade, Literary Hub has brought you the best of the book world for free—no paywall. But our future relies on you. In return for a donation, you’ll get an ad-free reading experience , exclusive editors’ picks, book giveaways, and our coveted Joan Didion Lit Hub tote bag . Most importantly, you’ll keep independent book coverage alive and thriving on the internet.

Become a member for as low as $5/month

The works of Brian Doyle remind us of the unique holiness of children and childhood

Every so often, a person carries a childlike stance of openness and vulnerability to wonder into adulthood. Brian Doyle, who died in 2017 after a short battle with cancer, was one such blessed anomaly in the literary landscape. Doyle worked (or better, played) with a variety of forms. He wrote essays, prose poems, adult novels, articles (including over a dozen pieces for America ), even a young adult novel. His writing stands apart in many ways, not the least of which is its focus on children . Doyle's work hums with an undercurrent that honors children and invites the reader to adopt their posture of innocence.

The typical toddler can squat for an interminable period of time, never tiring, quads not burning, lactic acid not building, no need for a fitness instructor to count down the seconds until he can stand upright again. The observatory stance is the child’s resting posture, a superpower second only to his or her sense of wonder at the veins of a leaf, the eyes of a toad, the stretch of a worm after the rain. Writing from this perspective, Doyle understood stories to be “ prayers of terrific power ,” and his readings are punctuated by “Amens.”

The writing of Brian Doyle, who died in 2017, hummed with an undercurrent that honors children and invites the reader to adopt their posture of innocence.

Born into a large Irish Catholic family in New York City, Brian James Patrick Doyle “ was soaked in stories from the start .” His father was a journalist and executive director of the Catholic Press Association; his mother was a gifted storyteller. Doyle adored his family, and his six brothers and one sister appear often in his essays. His prose poem (what Doyle called a “proem”) “The Tender Next Minute” invites the reader to return with him to the breath-stealing delight of a pause in chase. Doyle writes that he is in a hedge with two of his brothers for an instant “that I want to sing/ Here for a moment”: “we were smiling/ And thrilled and frightened and sunlight rippled through/ The tiny yellow flowers of the bushes.…/ You were there too, remember, in your childhood cave.”

For Doyle, childhood is delight, awe, power, joy and above all, grace. How can adults not spend time and creative energy remembering and celebrating it? Even contemplating roughhousing with his brothers conjures a pose of adoration:

[Y]ou would think the accumulated violence would have bred dislike or bitterness or vengeful urges, but I report with amazement that it did not.… Remember the crash of bodies, and the grapple in the grass, and the laughing pile on the rug, for that was the thrum of our love.

Doyle’s humble tears testify to his appreciation of the family he raised with his wife, Mary—especially because for a time that family seemed out of reach. He describes his first prayers as a father as the tears he cried when he and his wife were “told by a doctor, bluntly and directly and inarguably, that we would not be graced by children.” Doyle writes in his essay “Yes” of that in-between time: “For there were many nights before my children came to me on magic wooden boats from seas unknown that I wished desperately for them, that I cried because they had not yet come.”

For Doyle, childhood is delight, awe, power, joy and above all, grace. How can adults not spend time and creative energy remembering and celebrating it?

Once they had a daughter and twin sons, again he found himself crying every couple of weeks “for what seems like no reason at all; and I know it is because we were blessed with children, three of them, three long wild prayers; and they are the greatest gifts a profligate Mercy ever granted shuffling muddled me.” Doyle’s fatherly love and joy shine throughout his work in every form. Here is a man who understood the beauty, the irreplaceability, the gift of even the shortest life, and who stood in awe and humility before this grace without ceasing.

Liam, one of Doyle’s sons, was born with a heart one chamber short, requiring surgeries at 5 and 18 months and likely a heart transplant a few decades thereafter, all of which became the subject matter for Doyle’s book, The Wet Engine: Exploring the Mad Wild Miracle of the Heart . Of the times after these first two successful surgeries, Doyle writes, “But the days pass in their swirl and whirl and swing and song, and every day he doesn’t die again, and that knocks me out.”

Coupled with his reverence for childhood, the struggle to have children and the prospect of losing one of his children so young manifests itself in Doyle’s work as a witness to children’s unique holiness. In “Weal,” he writes, “But the most miraculous of all our gifts is children; without them we would laugh less, we would be bereft of innocence, we would lose hope, we would shrivel and vanish, with no one to remember what we so wished to be.”

And so a child stands at the fore of Mink River , Doyle’s first novel. The novel is the story of a town, or of a family, or perhaps of a town that is a family. A boy named Daniel has a bicycle accident and shatters the bones in both his legs. Doyle’s experience with Liam is filtered through lines from Daniel’s father, Owen: “His legs are all smashed. His knees are all smashed. My little boy.... He’s all smashed.” Daniel’s family and community rally around him. Not only does Daniel survive, but he encourages Owen to travel back to his native Ireland and reconcile with his own mother. Daniel is broken for a time, then leads his father to a richer, more loving life.

Likewise, in The Plover , the follow-up to Mink River , Declan’s friend “had been wounded by a storm, this guy, his little daughter hit by a bus driver when she was five years old waiting for the kindergarten bus, and his light was dimmed, and by now no one thought he would ever get it back.” The girl, Pipa, seems broken and incommunicative on the outside, but within she lives vibrantly: she can speak to animals and she is far more aware of the state and size of her soul than her father or Declan. She, too, offers the adults in her life hope and a measure of redemption.

With what some might call a uniquely Catholic point of view and others would recognize as simply a matter of common sense, Doyle draws unborn children characters with the same indisputable dignity as those out of the womb. Setting a scene of a young family, Doyle writes, “On Saturday Sara and Michael and the girls, three of them if you count the one in Sara’s womb, have breakfast together.” Later, another expectant mother loses a baby, and though the child’s mother can’t bestow a name on this child, the narrator does: Inch. The child is

born into the river…on and on he tumbles and whirls…his heart hammering, his arms and legs milling wildly, his eyes open, his mouth open…but as he nears the sea he fails, he fades…and just as he is startled by salt for the first and last time in the eleven minutes of his life he closes his eyes, puts his thumb in his mouth, and enters the ancient endless patient ocean, where all stories end, where all stories are born.

Doyle handles an otherwise unseen scene with grace; he observes the child with great love and compassion. To love children is to love life, and to love life is to honor death.

Doyle’s writing has the potential to stir this generation and the next to put down their smartphones and gape at every life with childlike wonder.

Near the end of the novel, a police officer, Michael, is recognized for his heroic sacrifice in apprehending a man who sexually assaulted his daughter. The governor awards Michael a medal, saying, “I have seen much, and now that my own service is about to end, I can be frank about what is important, as opposed to what we say is important. Children are important, and serving each other is important…and everything else is not as important.” How natural it is to imagine such language coming from Doyle himself.

Indeed, the protagonist of Chicago , modeled on a younger Doyle, relates an anecdote of a child lost and another found, a story that “above all others stays with me still,” given by the seasoned street officer, Matthew. Matthew sees the child, Muirin, every other day, “and you will too, if you keep your eyes peeled. Next time I see him I will point him out.” Should we learn to look with Doyle’s eyes, we won’t need Matthew’s gesturing; we will recognize the holiness, the mystery, the power in children for ourselves.

Doyle passed away in May 2017 at age 60, just six months after being diagnosed with a brain tumor. When asked how friends, fans and fellow writers could help him, his response was simple: “Be tender and laugh.” His greatest fear was not being able to support his family any longer; a crowd-funded campaign set up by a family friend helped ease his mind. He is remembered for his “fervor for storytelling and his unqualified joy in writing.”

Doyle’s writing has the potential to stir this generation and the next to put down their smartphones (unless they’re using them to read Doyle) and gape at every life with childlike wonder, to pause and see the more magnificent thing, the more tremendous gift toward which each tiny miracle points.

Lindsay Schlegel is a freelance writer and editor whose work has appeared in Verily, CatholicMom.com, Aleteia, Radiant, Vigil and more. She is the author of Don't Forget to Say Thank You: And Other Parenting Lessons That Brought Me Closer to God and co-author of T he Road to Hope: Responding to the Crisis of Addiction .

Most popular

Your source for jobs, books, retreats, and much more.

The latest from america

Brian Doyle’s literary moment continues with a new collection of his essays and epiphanies

- Published: Nov. 24, 2019, 11:00 a.m.

The late Lake Oswego author Brian Doyle. Oregonian file photo

- Scott F. Parker | For The Oregonian/OregonLive

For a handful of years before his death from brain cancer in 2017, Brian Doyle had been enjoying an extended literary moment.

It was a rare disappointment in the middle years of this decade to pick up a favorite literary magazine — whether The Sun or Orion or The American Scholar — and not open to a new poem or essay of Doyle’s. His name achieved elite status in the barroom confabulations of graduate writing students across the country. Meanwhile, in Oregon, not a book club in the state neglected to excite itself over his novels “ Mink River ” and “ Martin Marten .” That, anyway, is what it felt like to witness Doyle’s moment.

Thankfully, with the publication of “ One Long River of Song : Notes on Wonder for the Spiritual and Nonspiritual Alike” (Little, Brown and Co., 272 pages, $27), the moment remains ongoing.

Doyle’s longtime friend David James Duncan and two of his former editors, H. Emerson Blake and Kathleen Yale, have gathered some of Doyle’s most beloved short pieces alongside more obscure works to give readers a representative sampling of, not to mention a great introduction to, the range and quality of his writing.

Author David James Duncan, a longtime friend of Brian Doyle's, wrote the introduction to this new collection. Little, Brown and Co.

The first pleasure of reading Doyle lies in being swept away by the deft melding of his two most distinctive qualities, his sentences and his sensibility. How he loved sentences. And how he loved the world. Form and content never fit more hand in glove than in Doyle’s paratactic pilings on. Flip to any page in the book and you’re likely to encounter a sentence like, “I would kill the god who sentenced him to such awful pain, I would stab him in the heart like he stabbed my son, I would shove my fury in his face like a fist, but I know in my own broken heart that this same god made my magic boys, shaped their apple faces and coyote eyes, put joy in the eager suck of their mouths.” If the seams of his sentences sometimes burst, it’s because his heart does, too.

Some readers, inevitably, will agree with the letter writer who advised Doyle, “Breaking all the rules of syntax, apparently deliberately, does not constitute art.” But many more will respond that while his sentences are sometimes too much (and some of them are as long as this review), it would be a shame if they weren’t.

Doyle’s essays, by contrast, are often as short as the sentences are long. A typical Doyle essay begins with a memory or an anecdote or an idea, from which his mind then runs thought to thought until it collapses — often just a page or two later — in epiphany. I don’t know a writer who more reliably or with such seeming ease plucks genuine epiphanies fresh from the ether. The ubiquity of these is testament to Doyle’s craft or, perhaps, the quality of his attention, as Duncan suggests in the book’s foreword: “As much as any man or woman I’ve ever known, Brian James Patrick Doyle reveled in the act of awakening into the ten thousand things.”

“One Long River of Song” demonstrates what Doyle’s writing has always demonstrated, that when you find the courage to pay attention and be open to love, you can trust that “doing your chosen work with creativity and diligence will shiver people far beyond your ken.”

Celebration of Brian Doyle and book launch for “One Long River of Song”

When: 7 p.m. Tuesday, Dec. 3.

Where: Broadway Books, 1714 N.E. Broadway.

Admission: Free.

If you purchase a product or register for an account through a link on our site, we may receive compensation. By using this site, you consent to our User Agreement and agree that your clicks, interactions, and personal information may be collected, recorded, and/or stored by us and social media and other third-party partners in accordance with our Privacy Policy.

August 11, 2024

published by phi beta kappa

Print or web publication.

Originally published in Winter 2001

A couple leaped from the south tower, hand in hand. They reached for each other and their hands met and they jumped. Jennifer Brickhouse saw them falling, hand in hand.

Many people jumped. Perhaps hundreds. No one knows. They struck the pavement with such force that there was a pink mist in the air.

The mayor reported the mist.

A kindergarten boy who saw people falling in flames told his teacher that the birds were on fire. She ran with him on her shoulders out of the ashes.

Tiffany Keeling saw fireballs falling that she later realized were people. Jennifer Griffin saw people falling and wept as she told the story. Niko Winstral saw people free-falling backwards with their hands out, as if they were parachuting. Joe Duncan on his roof on Duane Street looked up and saw people jumping. Henry Weintraub saw people “leaping as they flew out.” John Carson saw six people fall, “falling over themselves, falling, they were somersaulting.” Steve Miller saw people jumping from a thousand feet in the air. Kirk Kjeldsen saw people flailing on the way down, people lining up and jumping, “too many people falling.” Jane Tedder saw people leaping and the sight haunts her at night. Steve Tamas counted fourteen people jumping and then he stopped counting. Stuart DeHann saw one woman’s dress billowing as she fell, and he saw a shirtless man falling end over end, and he too saw the couple leaping hand in hand.

Several pedestrians were killed by people falling from the sky. A fireman was killed by a body falling from the sky.

But he reached for her hand and she reached for his hand and they leaped out the window holding hands.

The day of the Lord will come as a thief in the night, in which the heavens shall pass away with a great noise, wrote John the Apostle, and the elements shall melt with a fervent heat, the earth also and the works that are therein shall be burned up.

I try to whisper prayers for the sudden dead and the harrowed families of the dead and the screaming souls of the murderers but I keep coming back to his hand and her hand nestled in each other with such extraordinary ordinary succinct ancient naked stunning perfect simple ferocious love.

There is no fear in love, wrote John, but perfect love casteth out fear, because fear hath torment .

Their hands reaching and joining are the most powerful prayer I can imagine, the most eloquent, the most graceful. It is everything that we are capable of against horror and loss and death. It is what makes me believe that we are not craven fools and charlatans to believe in God, to believe that human beings have greatness and holiness within them like seeds that open only under great fires, to believe that some unimaginable essence of who we are persists past the dissolution of what we were, to believe against such evil hourly evidence that love is why we are here.

Their passing away was thought an affliction, and their going forth from us utter destruction , says the Book of Wisdom, but they are in peace. They shall shine, and shall dart about as sparks through stubble.

No one knows who they were: husband and wife, lovers, dear friends, colleagues, strangers thrown together at the window there at the lip of hell. Maybe they didn’t even reach for each other consciously, maybe it was instinctive, a reflex, as they both decided at the same time to take two running steps and jump out the shattered window but they did reach for each other, and they held on tight, and leaped, and fell endlessly into the smoking canyon, at two hundred miles an hour, falling so far and so fast that they would have blacked out before they hit the pavement near Liberty Street so hard that there was a pink mist in the air.

I trust I shall shortly see thee , John wrote, and we shall speak face to face.

Jennifer Brickhouse saw them holding hands, and Stuart DeHann saw them holding hands, and I hold on to that.

Brian Doyle , an essayist and novelist, died on May 27, 2017. To read Epiphanies, his longtime blog for the Scholar , please go here.

● NEWSLETTER

Brian Doyle’s One Long River of Song: Notes on Wonder

Reviewed by Ana Maria Spagna

Little, Brown & Co. | 2019 | 217 pages

Setting aside his fine novels and book-length nonfiction, Doyle was an essayist first, and he was underappreciated for far too long, even as his essays—hundreds of them—appeared regularly in Orion, The Atlantic, Harper’s, The Sun, and American Scholar , plus in more Best of anthologies than you can cram on three shelves, not to mention in his monthly editor’s column in Portland magazine.

Editors Katie Yale and David James Duncan have culled through all of Doyle’s essays to gather more than 80 for the posthumous collection One Long River of Song: Notes on Wonder , which was published in December 2019. As a testament to its popularity, by mid-January 2020 the book had already gone through three printings.

What strikes me at first about this book is a familiar irony: as an uncontested master of the I-centered genre of personal essay, Doyle’s gaze turns insistently outward. These pages feature musings on, among other topics, sturgeon, fishers, raptors, otters, hummingbirds, brothers, sisters, sons and daughters, parents, and strangers who are not-strangers—all of us, any of us.

In “The Old Methodist Church on Vashon Island,” Doyle describes how he experienced attendees at book signings:

I have Learned that mostly they do not want my scribble as Much as they want to say something to me. So often What they say is quiet and haunting and just Enough of their deepest self that you both just stand There startled and quiet for an instant with that story Between you like it slid out without any forethought; A sort of jailbreak…

Hear the voice? Earnest, plainspoken, folksy even. He tosses in “mostly” and “just” and “sort of” and “so often” and “you.” Always “you.” He dances around the personal pronoun, exposing his deepest thoughts as “yours” and getting away with it.

Not that Doyle avoids center stage. When he does step up, playful and exuberant as ever, he’s unabashedly critical and self-critical. “Mea Culpa” begins with the bald admission, “I laughed at gay people. I did. I snickered at their crew cuts and sashay and flagrancy,” and ends, simply, with “Never again.”

“Brian Doyle Interviews Brian Doyle,” which is not about Brian Doyle at all, lists more than 100 writers with unvarnished opinions. John Updike, he argues, was a better literary critic than Edmund Wilson, who “couldn’t hold Updike’s jock when it comes to literary essays.” Mostly this essay is a praise song, a litany of names like a litany of saints. Doyle, after all, wore his Catholicism on his sleeve as proudly as his love of literature.

Doyle embraced big abstractions—love, grace, grief, faith, hope, and God—in a way that was sincere but never cloying. These essays are “for the spiritual and nonspiritual alike.” They are thoughtful, but not cerebral; funny but not wry. You’ll find nothing arrogant , a word he abhors, and much that’s gentle , a word he loves. You do not have to read Doyle long to make a list of words he abhors and words he adores.

Doyle’s agile prose, his rapacious humanity, never strays far from the body. In the essay, “Illuminos,” he celebrates physicality: “One child held on to my left pinky finger everywhere we went. Never any other finger and never the right pinky but only the left pinky and never my whole hand.” And onward through a paragraph of embodied hand-holding and later, trouser-tugging. By the time he gets to his punchline, that children are “agents of an unimaginable love,” he’s earned his pronouncement with these precise gestures, all tenderness in motion. (Consider, too, the embodiment of love in the crescendo of the last paragraph of “Joyas Voladoras”: “the brush of your mother’s papery ancient hand in the thicket of your hair…” Try to read that one without tearing up.)

The organization—the reticulation—of the essays is another great delight of One Long River of Song. There’s no separation of essays about animals from those about books or children or cowardice or humility or the human heart. They run like a river, around rocks; they separate and merge. “Irreconcilable Dissonance,” about how divorce informs every marriage, sits five short pages from “Raptorous,” an ode to raptors that is indeed rapturous. The pithy “Twenty Things the Dog Ate” is tucked a mere eight pages from “On Not Beating Cancer.”

No matter the essay, no matter the order, the sensibility is the same. Just as water in a river is the same. And blood coursing through a beating heart? Same. Even as he approaches the unfathomable. No one wrote more poignantly about 9/11 than Brian Doyle did in “Leap.” Then comes Sandy Hook, 20 children and six of their teachers shot dead, and we get “Dawn and Mary.” For a writer whose work brimmed with joy, his best known—and arguably his best —essays are about tragedy. In the end, Doyle’s grace outpaces his wisdom or humor or wordplay.

There are essays missing here, of course, some that I adore like “How We Wrestle Is Who We Are” from Orion and “Imagining Foxes” from Brevity . Some seem brand new, though I’d convinced myself I’d read them all. (Some he’d sent to me—as he did to all his many friends—as appendums to businessy emails. He’d finish a curt correspondence with “Thought you’d get a giggle out of this” and attach a couple of gems.)

But this collection, almost impossibly, feels whole . It begins with “Joyas Voladoras,” as beautiful an essay as exists in the English language, and ends with “Last Prayer,” in which Doyle hopes to meet his late friend Peter in the afterlife and, moreover, to find him reincarnated as an otter. Why? Because “Otters rule. And so: Amen.”

And so. We have to let Brian go, we’ve had to, and it’s excruciating. I feared reading the book would be excruciating, too. But it’s not. His essays are a gift to me, to you—the big “you” to whom he always reached out, grinning, another of his favorite words. Be grateful for otters and fishers and moles and children. And the words he left us.

Great review – an astounding essay collection, and person, and writer.

Well, this review is a gift, too. One master of the form writing with great beauty and insight about the work of another. Thank you.

Comments are closed.

Terrain.org is the first online literary journal of place, publishing award-winning literature, art, editorials, and community case studies since 1998.

In Terrain.org

- ARTerrain Galleries

- Unsprawl Case Studies

- Soundscapes Podcast

- Older Issues

- Latest News

- About Terrain.org

- Our Editors

- Teach Terrain.org

- Dear America

- Submit to Terrain.org

- Terrain Publishing

- Terrain.org on Bookshop

- Donate to Terrain.org

- Skip to main content

The University of Portland Magazine

Brian Doyle

Brian Doyle is an essayist, author, and editor of Portland Magazine at the University of Portland – “the best spiritual magazine in the country,” according to Annie Dillard.

He is the author of 13 books, among them the novel Mink River and the spiritual essay collections Grace Notes , Leaping , and Epiphanies & Elegies . His work has appeared in The Atlantic Monthly , Harper’s , Orion , The American Scholar , The Sun , and The New York Times , and his essays have been reprinted in the annual Best American Essays , Best American Science & Nature Writing , and Best American Spiritual Writing anthologies.to Annie Dillard. Portland Magazine is annually ranked among the ten best university magazines in America, and in 2005 won the Sibley Award from Newsweek magazine as the finest university magazine in the country.

His greatest accomplishments are that a riveting woman said yup when he mumbled a marriage proposal, and that the Coherent Mercy then sent them three lanky snotty sneery testy sweet brilliant nutty muttering children in skin boats from the sea of the stars. All else pales.

“Joyas Voladoras” by Brian Doyle. Summary and Symbolism Analysis Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Joyas Voladoras Essay: Introduction

The symbolism of brian doyle’s hummingbird, joyas voladoras: the symbolism of the whale, joyas voladoras: summary.

The “Joyas Voladoras” essay by Brian Doyle speaks of hummingbirds and hearts, the life of whales, and the life of man. That’s a profound reflection on life, death, and the experiences in between. In other words, the essay examines the similarity of every creature on Earth. In this paper, I make an analysis of the piece of literature, describe its main ideas, identify the author’s purpose, and share my impressions about Joyas Voladoras.

When reading the essay, one cannot help but be immersed in the distinct imagery created by the writer. In Joyas Voladoras, Brian Doyle elaborates on the fierceness of life embodied in hummingbirds and creates a sharp image of a small beating heart for the reader, a heart producing billion heartbeats infinitesimally but strongly, faster even than our own.

He elaborates both scientifically and metaphorically. At the same time, he structures this particular piece of prose in such a way that people who read it should not concentrate on the scientific, for that is all that they will see. Instead, they should examine the essay in terms of the metaphoric.

After literary analysis it is clear that “Joyas Voladoras” is filled with metaphorical symbolism. Let’s take as an example the following phrase in one of the paragraphs: “ the animals with the largest hearts in the world generally travel in pairs .” While scientific in appearance, it is a metaphor for love in which the essay states that people with love in their hearts are never alone.

Even references made by Doyle to the Hummingbird are another metaphoric symbolism of the abruptness of love and the value which we should place on it. Basing on the various metaphorical symbols seen throughout Joyas Voladoras, one can say that the text symbolizes different kinds of love in the world and the way they are experienced.

If one would pose a question of how to interpret the different animals portrayed in “Joyas Voladoras” essay as various aspects of love, then the Doyle’s Hummingbird could be symbolic of the concept of Eros or “erotic love.” This type of love is more commonly associated with the first stages of a relationship wherein love is based on physical traits, intense passion, and sudden affection. The intensity of the Hummingbird’s beating heart is symbolic of the passionate energy of love based on Eros.

The description of a “flying jewel” attributed to the Hummingbird is similar to how the love, based on Eros, is considered to be flashy and noticeable. Identical to a hummingbird love based on Eros alone does not last, it burns brightly just like the life of a hummingbird yet in a short time fizzles out.

Brian Doyle’s “Joyas Voladoras” has the purpose to state that this particular love is the worst kind to have since he symbolizes the people who are addicted to this type of love as experiencing emotional turmoil and heartache, as expressed by the heart of the Hummingbird slowing down when it comes to rest.

The line “if they do not soon find that which is sweet, their hearts grow cold, and they cease to be” is actually symbolic of the way in which people who prefer Eros love are actually addicted to the concept of loving and being loved forever moving from lover to lover, just like a hummingbird moves from flower to flower.

The symbolic nature of the Whale as a type of love for Doyle takes the form of Philos, namely a kind of love which is based on the friendship between two people. While the phrase “the animals with the largest hearts in the world generally travel in pairs” is indicative of Philos love, other aspects of this particular type of love are also apparent.

An analysis of the type of grammar used by Doyle in describing the Hummingbird and the Whale shows that, for the Hummingbird, Doyle uses action gerund words which utilize the word “and” rather than a comma.

The result of such grammatical usage is thus an almost breathless mannerism in which readers read the parts detailing the life of a hummingbird. This is symbolic of the breathless nature of erotic love wherein those who ascribe to it find themselves flitting from action to action without heed or care.

On the other hand, when describing the blue Whale, Doyle utilizes exceedingly long sentences and traditional words interspaced with commas, which have the effect of slowing down the reader. This is intentional on the part of the author since Philo’s type of love is a form of love that begins after a long and prosperous friendship.

It is a type of love that builds up over time, creating strong affection, emotions, and a feeling of longing to be with that person. The nature of the size of whale hearts is symbolic of the intense emotions and love that build up over time, resulting in a type of relationship where two people stay together for a lifetime.

What is the main idea of “Joyas Voladoras”? Based on what has been presented in this paper, it can be seen that one aspect of the essay “Joyas Voladoras” by Brian Doyle is that it uses symbolism to express the concepts of Eros and Philos. While the paper possess other forms of symbolism, these particular aspects were chosen since they help to relay the message of the author that there are different types of love out there, each having its unique characteristics.

In summary, it is due to viewing the essay in this particular way that the continuous use of the word “heart” can thus be interpreted as symbolic of people continuously searching for love with the author warning in the ending of the possible pain that comes with this search.

Doyle, B. (2012, June 12). Joyas Voladoras . The American Scholar. Web.

- Without Conscience: The Disturbing World of the Psychopaths among Us

- Walt Whitman: Life of an American Poet

- Anthrax: Breathless in the Midwest

- Childhood Memories in Doyle's, Griffin's, Foer's Works

- The 10-1 approach on discussing the path to live a true life

- "Tripp Lake" by Lauren Slater

- The Lottery Literary Analysis – Summary & Analytical Essay

- It’s Just the Way the Game Is Played”: The Move from Adulthood. An Interpretation of Benjamin Percy’s Story “Refresh, Refresh

- Learning to Stereotype: The Lifelong Romance

- Conflicting Motives in “Hippocrates”

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, May 31). “Joyas Voladoras” by Brian Doyle. Summary and Symbolism Analysis. https://ivypanda.com/essays/joyas-voladoras/

"“Joyas Voladoras” by Brian Doyle. Summary and Symbolism Analysis." IvyPanda , 31 May 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/joyas-voladoras/.

IvyPanda . (2018) '“Joyas Voladoras” by Brian Doyle. Summary and Symbolism Analysis'. 31 May.

IvyPanda . 2018. "“Joyas Voladoras” by Brian Doyle. Summary and Symbolism Analysis." May 31, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/joyas-voladoras/.

1. IvyPanda . "“Joyas Voladoras” by Brian Doyle. Summary and Symbolism Analysis." May 31, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/joyas-voladoras/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "“Joyas Voladoras” by Brian Doyle. Summary and Symbolism Analysis." May 31, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/joyas-voladoras/.

Brian Doyle

Brian Doyle (1956-2017) was the longtime editor of Portland Magazine at the University of Portland, in Oregon. He was the author of six collections of essays, two nonfiction books, two collections of “proems,” the short story collection Bin Laden’s Bald Spot , the novella Cat’s Foot , and the novels Mink River , The Plover , and Martin Marten . He is also the editor of several anthologies, including Ho`olaule`a , a collection of writing about the Pacific islands. Doyle’s books have seven times been finalists for the Oregon Book Award, and his essays have appeared in The Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s, Orion , The American Scholar , The Sun, The Georgia Review , and in newspapers and magazines around the world, including The New York Times , The Times of London , and The Age (in Australia). His essays have also been reprinted in the annual Best American Essays , Best American Science & Nature Writing, and Best American Spiritual Writing anthologies. Among various honors for his work is a Catholic Book Award, three Pushcart Prizes, the John Burroughs Award for Nature Essays, Foreword Reviews’ Novel of the Year award in 2011, and the Award in Literature from the American Academy of Arts and Letters in 2008 (previous recipients include Saul Bellow, Kurt Vonnegut, Flannery O’Connor, and Mary Oliver).”

Contributions from Brian Doyle

Their Irrepressible Innocence

9 Places to Pee in the Great Outdoors

21 Laws of Nature as Interpreted by My Children

20 Things the Dog Ate

The Greatest Nature Essay Ever

Brian doyle’s reading list.

How We Wrestle Is Who We Are

How to Live in Your Car

Welcome to orion's new website.

How to cite ChatGPT

Use discount code STYLEBLOG15 for 15% off APA Style print products with free shipping in the United States.

We, the APA Style team, are not robots. We can all pass a CAPTCHA test , and we know our roles in a Turing test . And, like so many nonrobot human beings this year, we’ve spent a fair amount of time reading, learning, and thinking about issues related to large language models, artificial intelligence (AI), AI-generated text, and specifically ChatGPT . We’ve also been gathering opinions and feedback about the use and citation of ChatGPT. Thank you to everyone who has contributed and shared ideas, opinions, research, and feedback.

In this post, I discuss situations where students and researchers use ChatGPT to create text and to facilitate their research, not to write the full text of their paper or manuscript. We know instructors have differing opinions about how or even whether students should use ChatGPT, and we’ll be continuing to collect feedback about instructor and student questions. As always, defer to instructor guidelines when writing student papers. For more about guidelines and policies about student and author use of ChatGPT, see the last section of this post.

Quoting or reproducing the text created by ChatGPT in your paper

If you’ve used ChatGPT or other AI tools in your research, describe how you used the tool in your Method section or in a comparable section of your paper. For literature reviews or other types of essays or response or reaction papers, you might describe how you used the tool in your introduction. In your text, provide the prompt you used and then any portion of the relevant text that was generated in response.

Unfortunately, the results of a ChatGPT “chat” are not retrievable by other readers, and although nonretrievable data or quotations in APA Style papers are usually cited as personal communications , with ChatGPT-generated text there is no person communicating. Quoting ChatGPT’s text from a chat session is therefore more like sharing an algorithm’s output; thus, credit the author of the algorithm with a reference list entry and the corresponding in-text citation.

When prompted with “Is the left brain right brain divide real or a metaphor?” the ChatGPT-generated text indicated that although the two brain hemispheres are somewhat specialized, “the notation that people can be characterized as ‘left-brained’ or ‘right-brained’ is considered to be an oversimplification and a popular myth” (OpenAI, 2023).

OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT (Mar 14 version) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat

You may also put the full text of long responses from ChatGPT in an appendix of your paper or in online supplemental materials, so readers have access to the exact text that was generated. It is particularly important to document the exact text created because ChatGPT will generate a unique response in each chat session, even if given the same prompt. If you create appendices or supplemental materials, remember that each should be called out at least once in the body of your APA Style paper.

When given a follow-up prompt of “What is a more accurate representation?” the ChatGPT-generated text indicated that “different brain regions work together to support various cognitive processes” and “the functional specialization of different regions can change in response to experience and environmental factors” (OpenAI, 2023; see Appendix A for the full transcript).

Creating a reference to ChatGPT or other AI models and software

The in-text citations and references above are adapted from the reference template for software in Section 10.10 of the Publication Manual (American Psychological Association, 2020, Chapter 10). Although here we focus on ChatGPT, because these guidelines are based on the software template, they can be adapted to note the use of other large language models (e.g., Bard), algorithms, and similar software.

The reference and in-text citations for ChatGPT are formatted as follows:

- Parenthetical citation: (OpenAI, 2023)

- Narrative citation: OpenAI (2023)

Let’s break that reference down and look at the four elements (author, date, title, and source):

Author: The author of the model is OpenAI.

Date: The date is the year of the version you used. Following the template in Section 10.10, you need to include only the year, not the exact date. The version number provides the specific date information a reader might need.

Title: The name of the model is “ChatGPT,” so that serves as the title and is italicized in your reference, as shown in the template. Although OpenAI labels unique iterations (i.e., ChatGPT-3, ChatGPT-4), they are using “ChatGPT” as the general name of the model, with updates identified with version numbers.

The version number is included after the title in parentheses. The format for the version number in ChatGPT references includes the date because that is how OpenAI is labeling the versions. Different large language models or software might use different version numbering; use the version number in the format the author or publisher provides, which may be a numbering system (e.g., Version 2.0) or other methods.

Bracketed text is used in references for additional descriptions when they are needed to help a reader understand what’s being cited. References for a number of common sources, such as journal articles and books, do not include bracketed descriptions, but things outside of the typical peer-reviewed system often do. In the case of a reference for ChatGPT, provide the descriptor “Large language model” in square brackets. OpenAI describes ChatGPT-4 as a “large multimodal model,” so that description may be provided instead if you are using ChatGPT-4. Later versions and software or models from other companies may need different descriptions, based on how the publishers describe the model. The goal of the bracketed text is to briefly describe the kind of model to your reader.

Source: When the publisher name and the author name are the same, do not repeat the publisher name in the source element of the reference, and move directly to the URL. This is the case for ChatGPT. The URL for ChatGPT is https://chat.openai.com/chat . For other models or products for which you may create a reference, use the URL that links as directly as possible to the source (i.e., the page where you can access the model, not the publisher’s homepage).

Other questions about citing ChatGPT

You may have noticed the confidence with which ChatGPT described the ideas of brain lateralization and how the brain operates, without citing any sources. I asked for a list of sources to support those claims and ChatGPT provided five references—four of which I was able to find online. The fifth does not seem to be a real article; the digital object identifier given for that reference belongs to a different article, and I was not able to find any article with the authors, date, title, and source details that ChatGPT provided. Authors using ChatGPT or similar AI tools for research should consider making this scrutiny of the primary sources a standard process. If the sources are real, accurate, and relevant, it may be better to read those original sources to learn from that research and paraphrase or quote from those articles, as applicable, than to use the model’s interpretation of them.

We’ve also received a number of other questions about ChatGPT. Should students be allowed to use it? What guidelines should instructors create for students using AI? Does using AI-generated text constitute plagiarism? Should authors who use ChatGPT credit ChatGPT or OpenAI in their byline? What are the copyright implications ?

On these questions, researchers, editors, instructors, and others are actively debating and creating parameters and guidelines. Many of you have sent us feedback, and we encourage you to continue to do so in the comments below. We will also study the policies and procedures being established by instructors, publishers, and academic institutions, with a goal of creating guidelines that reflect the many real-world applications of AI-generated text.

For questions about manuscript byline credit, plagiarism, and related ChatGPT and AI topics, the APA Style team is seeking the recommendations of APA Journals editors. APA Style guidelines based on those recommendations will be posted on this blog and on the APA Style site later this year.

Update: APA Journals has published policies on the use of generative AI in scholarly materials .

We, the APA Style team humans, appreciate your patience as we navigate these unique challenges and new ways of thinking about how authors, researchers, and students learn, write, and work with new technologies.

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1037/0000165-000

Related and recent

Comments are disabled due to your privacy settings. To re-enable, please adjust your cookie preferences.

APA Style Monthly

Subscribe to the APA Style Monthly newsletter to get tips, updates, and resources delivered directly to your inbox.

Welcome! Thank you for subscribing.

APA Style Guidelines

Browse APA Style writing guidelines by category

- Abbreviations

- Bias-Free Language

- Capitalization

- In-Text Citations

- Italics and Quotation Marks

- Paper Format

- Punctuation

- Research and Publication

- Spelling and Hyphenation

- Tables and Figures

Full index of topics

Follow to get new release updates, special offers (including promotional offers) and improved recommendations.

Brian Doyle

About the author.

Brian Doyle (born in New York in 1956) is the editor of Portland Magazine at the University of Portland, in Oregon. He is the author of many books, among them the novels Mink River (set in Oregon), The Plover (in the South Seas), Martin Marten (on Oregon's Wy'east mountain, foolishly often called Mount Hood), and Chicago (take a guess). Among his other books are the story collection Bin Laden's Bald Spot, the nonfiction books The Grail and The Wet Engine, and many books of essays and poems. Brian James Patrick Doyle of New Yawk is cheerfully NOT the great Canadian novelist Brian Doyle, nor the astrophysicist Brian Doyle, nor the former Yankee baseball player Brian Doyle, nor even the terrific actor Brian Doyle-Murray. He is, let's say, the ambling shambling Oregon writer Brian Doyle, and happy to be so.

Most popular

Customers also bought items by

- About Amazon

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell products on Amazon

- Sell on Amazon Business

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Become an Affiliate

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Host an Amazon Hub

- › See More Make Money with Us

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Amazon and COVID-19

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Royals superstar Witt, Rockies standout Doyle named Players of the Month

Brian Murphy