Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

What’s It Like To Be a Teacher in America Today?

3. problems students are facing at public k-12 schools, table of contents.

- Problems students are facing

- A look inside the classroom

- How teachers are experiencing their jobs

- How teachers view the education system

- Satisfaction with specific aspects of the job

- Do teachers feel trusted to do their job well?

- Likelihood that teachers will change jobs

- Would teachers recommend teaching as a profession?

- Reasons it’s so hard to get everything done during the workday

- Staffing issues

- Balancing work and personal life

- How teachers experience their jobs

- Lasting impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

- Major problems at school

- Discipline practices

- Policies around cellphone use

- Verbal abuse and physical violence from students

- Addressing behavioral and mental health challenges

- Teachers’ interactions with parents

- K-12 education and political parties

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

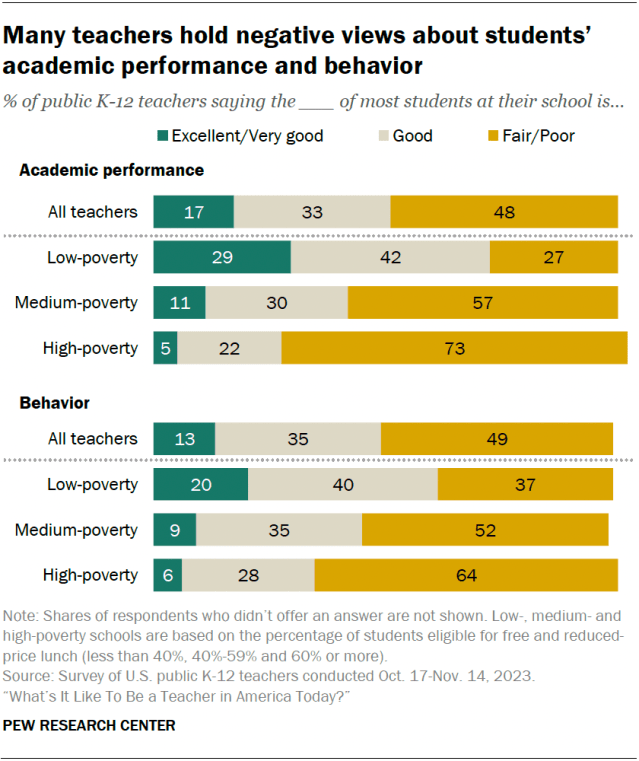

We asked teachers about how students are doing at their school. Overall, many teachers hold negative views about students’ academic performance and behavior.

- 48% say the academic performance of most students at their school is fair or poor; a third say it’s good and only 17% say it’s excellent or very good.

- 49% say students’ behavior at their school is fair or poor; 35% say it’s good and 13% rate it as excellent or very good.

Teachers in elementary, middle and high schools give similar answers when asked about students’ academic performance. But when it comes to students’ behavior, elementary and middle school teachers are more likely than high school teachers to say it’s fair or poor (51% and 54%, respectively, vs. 43%).

Teachers from high-poverty schools are more likely than those in medium- and low-poverty schools to say the academic performance and behavior of most students at their school are fair or poor.

The differences between high- and low-poverty schools are particularly striking. Most teachers from high-poverty schools say the academic performance (73%) and behavior (64%) of most students at their school are fair or poor. Much smaller shares of teachers from low-poverty schools say the same (27% for academic performance and 37% for behavior).

In turn, teachers from low-poverty schools are far more likely than those from high-poverty schools to say the academic performance and behavior of most students at their school are excellent or very good.

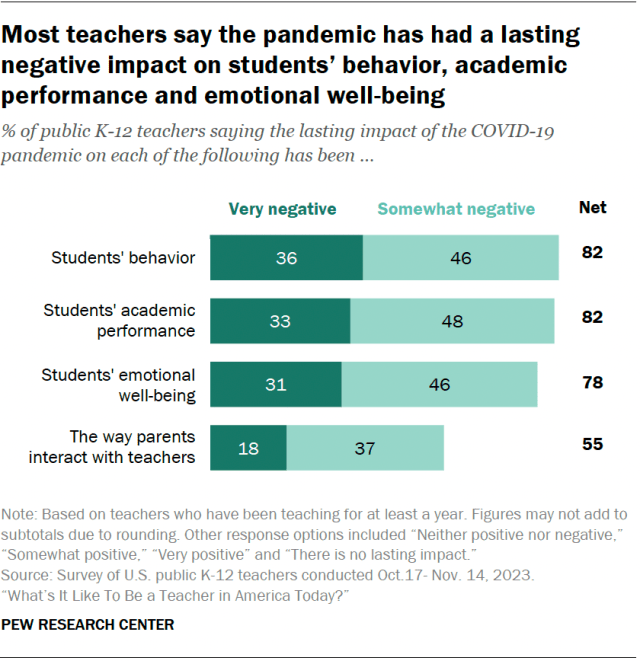

Among those who have been teaching for at least a year, about eight-in-ten teachers say the lasting impact of the pandemic on students’ behavior, academic performance and emotional well-being has been very or somewhat negative. This includes about a third or more saying that the lasting impact has been very negative in each area.

Shares ranging from 11% to 15% of teachers say the pandemic has had no lasting impact on these aspects of students’ lives, or that the impact has been neither positive nor negative. Only about 5% say that the pandemic has had a positive lasting impact on these things.

A smaller majority of teachers (55%) say the pandemic has had a negative impact on the way parents interact with teachers, with 18% saying its lasting impact has been very negative.

These results are mostly consistent across teachers of different grade levels and school poverty levels.

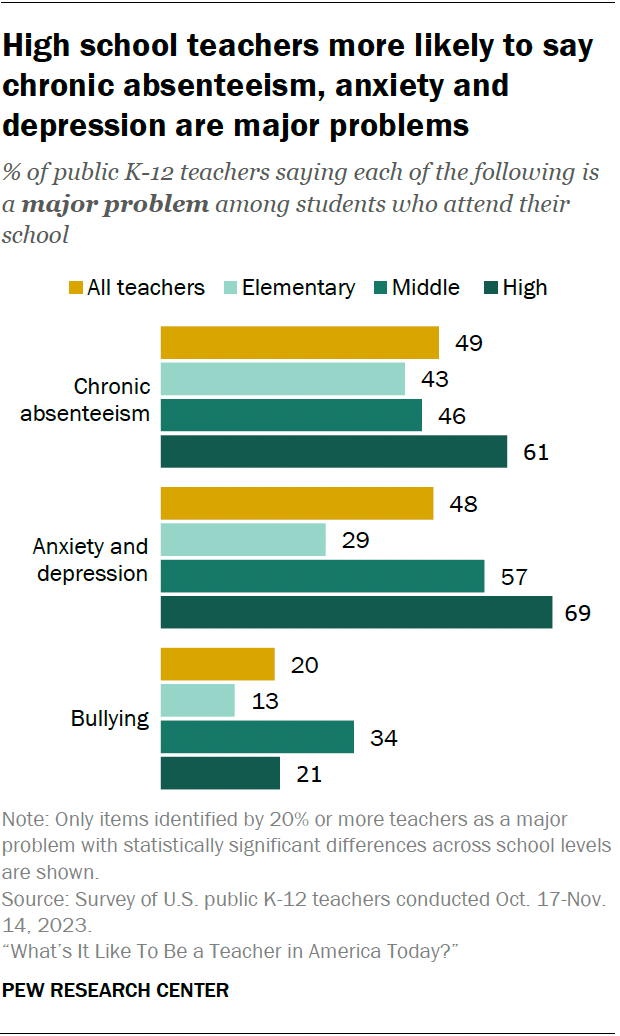

When we asked teachers about a range of problems that may affect students who attend their school, the following issues top the list:

- Poverty (53% say this is a major problem at their school)

- Chronic absenteeism – that is, students missing a substantial number of school days (49%)

- Anxiety and depression (48%)

One-in-five say bullying is a major problem among students at their school. Smaller shares of teachers point to drug use (14%), school fights (12%), alcohol use (4%) and gangs (3%).

Differences by school level

Similar shares of teachers across grade levels say poverty is a major problem at their school, but other problems are more common in middle or high schools:

- 61% of high school teachers say chronic absenteeism is a major problem at their school, compared with 43% of elementary school teachers and 46% of middle school teachers.

- 69% of high school teachers and 57% of middle school teachers say anxiety and depression are a major problem, compared with 29% of elementary school teachers.

- 34% of middle school teachers say bullying is a major problem, compared with 13% of elementary school teachers and 21% of high school teachers.

Not surprisingly, drug use, school fights, alcohol use and gangs are more likely to be viewed as major problems by secondary school teachers than by those teaching in elementary schools.

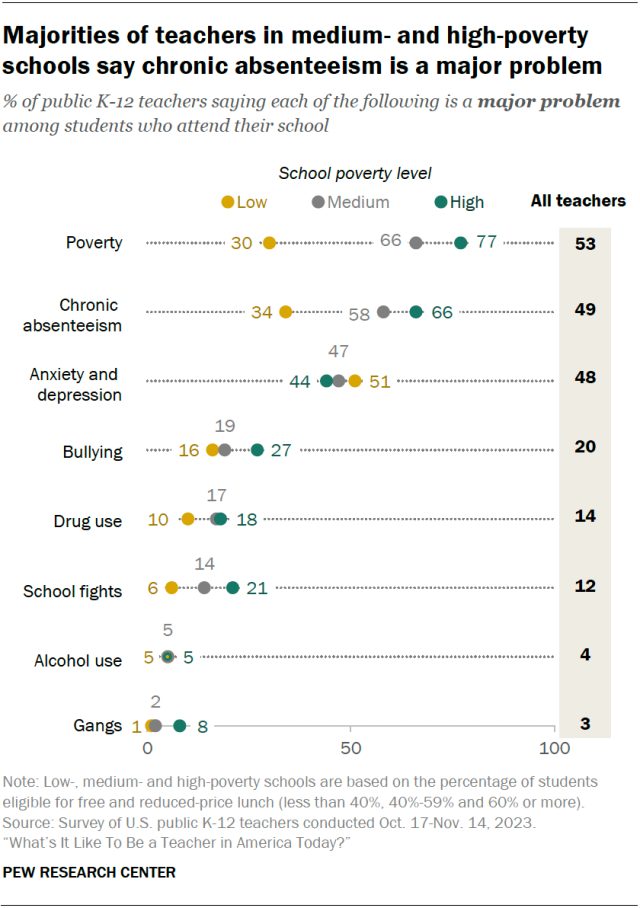

Differences by poverty level

Teachers’ views on problems students face at their school also vary by school poverty level.

Majorities of teachers in high- and medium-poverty schools say chronic absenteeism is a major problem where they teach (66% and 58%, respectively). A much smaller share of teachers in low-poverty schools say this (34%).

Bullying, school fights and gangs are viewed as major problems by larger shares of teachers in high-poverty schools than in medium- and low-poverty schools.

When it comes to anxiety and depression, a slightly larger share of teachers in low-poverty schools (51%) than in high-poverty schools (44%) say these are a major problem among students where they teach.

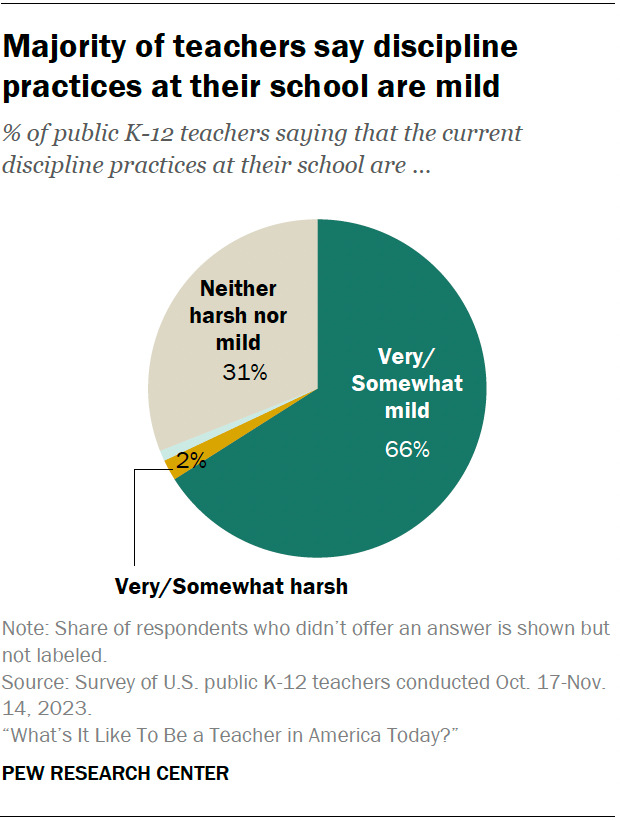

About two-thirds of teachers (66%) say that the current discipline practices at their school are very or somewhat mild – including 27% who say they’re very mild. Only 2% say the discipline practices at their school are very or somewhat harsh, while 31% say they are neither harsh nor mild.

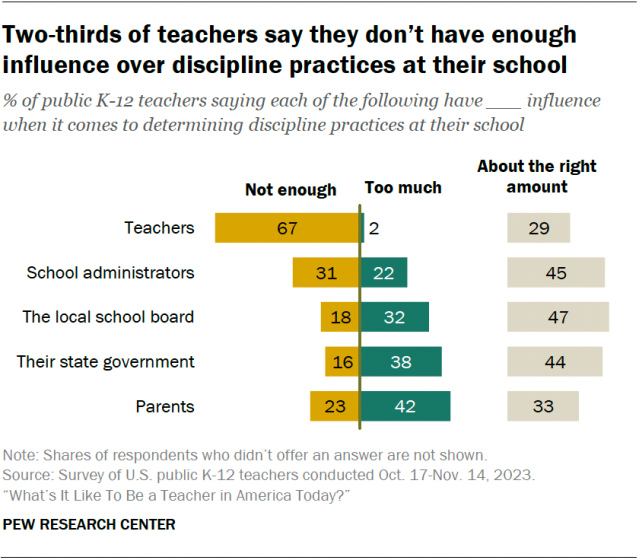

We also asked teachers about the amount of influence different groups have when it comes to determining discipline practices at their school.

- 67% say teachers themselves don’t have enough influence. Very few (2%) say teachers have too much influence, and 29% say their influence is about right.

- 31% of teachers say school administrators don’t have enough influence, 22% say they have too much, and 45% say their influence is about right.

- On balance, teachers are more likely to say parents, their state government and the local school board have too much influence rather than not enough influence in determining discipline practices at their school. Still, substantial shares say these groups have about the right amount of influence.

Teachers from low- and medium-poverty schools (46% each) are more likely than those in high-poverty schools (36%) to say parents have too much influence over discipline practices.

In turn, teachers from high-poverty schools (34%) are more likely than those from low- and medium-poverty schools (17% and 18%, respectively) to say that parents don’t have enough influence.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Education & Politics

72% of U.S. high school teachers say cellphone distraction is a major problem in the classroom

U.s. public, private and charter schools in 5 charts, is college worth it, half of latinas say hispanic women’s situation has improved in the past decade and expect more gains, a quarter of u.s. teachers say ai tools do more harm than good in k-12 education, most popular, report materials.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan, nonadvocacy fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It does not take policy positions. The Center conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, computational social science research and other data-driven research. Pew Research Center is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts , its primary funder.

© 2024 Pew Research Center

The global education crisis – even more severe than previously estimated

Ellinore carroll, joão pedro azevedo, jessica bergmann, matt brossard, gwang- chol chang, borhene chakroun, marie-helene cloutier, suguru mizunoya, nicolas reuge, halsey rogers.

In our recent The State of the Global Education Crisis: A Path to Recovery report (produced jointly by UNESCO, UNICEF, and the World Bank), we sounded the alarm: this generation of students now risks losing $17 trillion in lifetime earnings in present value, or about 14 percent of today’s global GDP, because of COVID-19-related school closures and economic shocks. This new projection far exceeds the $10 trillion estimate released in 2020 and reveals that the impact of the pandemic is more severe than previously thought .

The pandemic and school closures not only jeopardized children’s health and safety with domestic violence and child labor increasing, but also impacted student learning substantially. The report indicates that in low- and middle-income countries, the share of children living in Learning Poverty – already above 50 percent before the pandemic – could reach 70 percent largely as a result of the long school closures and the relative ineffectiveness of remote learning.

Unless action is taken, learning losses may continue to accumulate once children are back in school, endangering future learning.

Figure 1. Countries must accelerate learning recovery

Severe learning losses and worsening inequalities in education

Results from global simulations of the effect of school closures on learning are now being corroborated by country estimates of actual learning losses. Evidence from Brazil , rural Pakistan , rural India , South Africa , and Mexico , among others, shows substantial losses in math and reading. In some low- and middle-income countries, on average, learning losses are roughly proportional to the length of the closures—meaning that each month of school closures led to a full month of learning losses (Figure 1, selected LMICs and HICs presents an average effect of 100% and 43%, respectively), despite the best efforts of decision makers, educators, and families to maintain continuity of learning.

However, the extent of learning loss varies substantially across countries and within countries by subject, students’ socioeconomic status, gender, and age or grade level (Figure 1 illustrates this point, note the large standard deviation, a measure which shows data are spread out far from the mean). For example, results from two states in Mexico show significant learning losses in reading and in math for students aged 10-15. The estimated learning losses were greater in math than reading, and they disproportionately affected younger learners, students from low-income backgrounds, and girls.

Figure 2. The average learning loss standardized by the length of the school closure was close to 100% in Low- and Middle-Income countries, and 43% in High-Income countries, with a standard deviation of 74% and 30%, respectively.

While most countries have yet to measure learning losses, data from several countries, combined with more extensive evidence on unequal access to remote learning and at-home support, shows the crisis has exacerbated inequalities in education globally.

- Children from low-income households, children with disabilities, and girls were less likely to access remote learning due to limited availability of electricity, connectivity, devices, accessible technologies as well as discrimination and social and gender norms.

- Younger students had less access to age-appropriate remote learning and were more affected by learning loss than older students. Pre-school-age children, who are at a pivotal stage for learning and development, faced a double disadvantage as they were often left out of remote learning and school reopening plans.

- Learning losses were greater for students of lower socioeconomic status in various countries, including Ghana , Mexico , and Pakistan .

- While the gendered impact of school closures on learning is still emerging, initial evidence points to larger learning losses among girls, including in South Africa and Mexico .

As a result, these children risk missing out on much of the boost that schools and learning can provide to their well-being and life chances. The learning recovery response must therefore target support to those that need it most, to prevent growing inequalities in education.

Beyond learning, growing evidence shows the negative effects school closures have had on students’ mental health and well-being, health and nutrition, and protection, reinforcing the vital role schools play in providing comprehensive support and services to students.

Critical and Urgent Need to Focus on Learning Recovery

How should decision makers and the international community respond to the growing global education crisis?

Reopening schools and keeping them open must be the top priority, globally. While nearly every country in the world offered remote learning opportunities for students, the quality and reach of such initiatives varied, and in most cases, they offered a poor substitute for in-person instruction. Stemming and reversing learning losses, especially for the most vulnerable students, requires in-person schooling. Decision makers need to reassure parents and caregivers that with adequate safety measures, such as social distancing, masking, and improved ventilation, global evidence shows that children can resume in-person schooling safely.

But just reopening schools with a business-as-usual approach won’t reverse learning losses. Countries need to create Learning Recovery Programs . Three lines of action will be crucial:

- Consolidating the curriculum – to help teachers prioritize essential material that students have missed while out of school, even if the content is usually covered in earlier grades, to ensure the curriculum is aligned to students’ learning levels. As an example, Tanzania consolidated its curriculum for grade 1 and 2 in 2015, reducing the number of subjects taught and increasing time on ensuring the acquisition of foundational numeracy and literacy.

- Extending instructional time – by extending the school day, modifying the academic calendar to make the school year longer, or by offering summer school for all students or those in need. In Mexico , the Ministry of Public Education announced planned extensions to the academic calendar to help recovery. In Madagascar , the government scaled up an existing two-month summer “catch-up” program for students who reintegrate into school after having left the system.

- Improving the efficiency of learning – by supporting teachers to apply structured pedagogy and targeted instruction. A structured pedagogy intervention in Kenya using teachers guides with lesson plans has proven to be highly effective. Targeted instruction, or aligning instruction to students’ learning level, has been successfully implemented at scale in Cote D’Ivoire .

Finally, the report emphasizes the need for adequate funding. As of June 2021, the education and training sector had been allocated less than 3 percent of global stimulus packages. Much more funding will be needed for immediate learning recovery if countries are to avert the long-term damage to productivity and inclusion that they now face.

Learning Recovery as a Springboard to an Accelerated Learning Trajectory

Accelerating learning recovery has benefits that go well beyond short-term gains: it can give children the necessary foundations for a lifetime of learning, and it can help countries increase the efficiency, equity, and resilience of schooling. This can be achieved if countries build on investments made and lessons learned during the crisis—most notably, with a focus on six areas:

- Assessing student learning so instruction can be targeted to students’ learning levels and specific needs.

- Investing in digital learning opportunities for all students, ensuring that technology is fit for purpose and focused on enhancing human interactions.

- Reinforcing support that leverages the role of parents, families, and communities in children’s learning.

- Ensuring that teachers are supported and have access to practical, high-quality professional development opportunities, teaching guides and learning materials.

- Increasing the share of education in the national budget allocation of stimulus packages and tying it to investments mentioned above that can accelerate learning.

- Investing in evidence building - in particular, implementation research, to understand what works and how to scale what works to the system level.

It is time to shift from crisis response to learning recovery. We must make sure that investments and actions for learning recovery lay the foundations for more efficient, equitable, and resilient education systems—systems that truly deliver learning and well-being for all children and youth. Only then can we ensure learning continuity in the face of future disruption.

The report was produced as part of the Mission: Recovering Education 2021 , through which the World Bank , UNESCO , and UNICEF are focused on three priorities: bringing all children back to schools, recovering learning losses, and preparing and supporting teachers.

Get updates from Education for Global Development

Thank you for choosing to be part of the Education for Global Development community!

Your subscription is now active. The latest blog posts and blog-related announcements will be delivered directly to your email inbox. You may unsubscribe at any time.

Young Professional

Lead Economist

Education Researcher – UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti

Chief, Education – UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti

Chief of Education Policy Section, Division of Policies and Lifelong Learning Systems, UNESCO Education Sector

Director, Division for Policies and Lifelong Learning Systems, UNESCO Education Sector

Senior Economist

Senior Advisor, Statistics and Monitoring (Education) – UNICEF New York HQ

Senior Adviser Education, UNICEF Headquarters

Lead Economist, Education Global Practice

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

Education 2030: topics and issues

The debates included the following sessions:

Providing meaningful learning opportunities to out-of-school children

In this session a panel of experts explored the changes needed in countries which have large out-of-school children populations as well as examples from countries which are ‘in the final mile’. “T hey are all different, they don’t fit into one box ” said Mary Joy Pigozzi, Director of Educate A Child (EAC). Ms Pigozzi emphasized the need for attention to children who are displaced, conflict affected, working children, and so on. Mr Albert Montivans, Head of Education Indicators and Data Analysis at UNESCO Institute for Statistics added: “ one of the priorities is to better the disadvantaged ”.

The session was also attended by the Minister of Education, Haiti, Nesmy Manigat, the CEO of Global Partnership for Education Alice Albright, and the Director-General in the Romanian Ministry of Education, Liliana Preoteasa. The panelists raised their voices on ‘inclusion’, ‘partnership’, ‘financing’, and ‘sustainable planning’ in order to pull youngsters into the schooling system. The session concluded with further food for thought from Mr Nesmy Manigat, the Minister of Education,Haiti: “ Let’s also talk about the children who are in school, yet they do not learn. Teach them what the meaning of school is - what do we need to do in school and not only focus on the policies ”.

Mobilizing Business to Realize the 2030 Education Agenda

Representatives from business and education organizations gathered at a parallel session on mobilizing business to realize the 2030 agenda. Chaired by Justin van Fleet, Chief of Staff for the UN Special Envoy for Global Education, the session established a business case to invest in education and focused on how business can coordinate action with other stakeholders. The lively discussion saw questions from the floor around ICT’s, but also issues of trust; with a representative from the Philippines asking the panel whether business cares about education or is simply benefiting from it. The President of Lego Education, Mr Jacob Kragh, said there was a sincere objective from the company “ to pursue the benefit of the children and make sure they get the chance to be the best they can in life ”. He said that " taking over education was by no means the objective of the private sector ", and reiterated the importance of working closely with governments and the public sector. Panelists also included Vikas Pota from GEMS Education, Martina Roth from Intel Corporation and Jouko Sarvi from the Asian Development Bank.

In parallel, Argentina’s Minister of Education, Alberto Sileoni, was joined by UNESCO Director, David Atchoarena, and UN Special Advisor on Post-2015 Development Planning, Amina Mohammed, at a session on Global and regional coordination and monitoring mechanisms. The session dealt with the importance of having robust mechanisms for coordination and monitoring. Session participants looked at how global and regional mechanisms for education should work alongside the new mechanisms for the overall Sustainable Development Goal, with Mr Atchoarena pointing out that the focus on ‘country-level’ monitoring and review was much stronger in the new education agenda.

Effective Governance and Accountability

In this group session, the panelists suggested the right direction for contemporary national education governance. Namely the key policies and strategies to construct a pragmatic governance framework that is both regulatory and collaborative were suggested throughout the discussion.

The chair, Mr. Gwang-Jo Kim, Director of UNESCO’s regional office in Bangkok, Thailand, posed three questions before the discussion: How can we define the term “effective governance”. What would be the role of the private sector and how to balance between autonomy resulting from decentralization, and accountability. The panels and the participants engaged in a lively debate: “ Governance should focus on dialogue between communities in society so that private sector can become stakeholders to invest in education ,” stated the Minister of Education, Bolivia, Roberto Aguilar, as an answer to the second question. He also gave an example from his country where education campaigns are usually funded by private institutions, saying it is social responsibility for private entities to participate actively in the effective governance framework.

The Minster of Education, Democratic Republic of Congo,Maker Mwangu Famba, said the core elements of effective governance were transparency and responsibility.

How does education contribute to sustainable development post 2015?

Sustainable development is not just about technological solutions, political regulation or financial instruments alone. The realization of the transformative power of education and the importance of cross-sectoral approaches need to be taken into account. This was the message given by Ms Amina Mohammed, Special Advisor to the UN Secretary-General on Post 2015 Development Planning, as she said that education was not simply about learning, it is about empowerment and key in the sustainable development agenda. In this session, the panel members discussed how education can address global challenges, in particular how education contributes to addressing climate change and health issues and poverty reduction.

Education is one of the most powerful tools for people to be informed about diseases, take preventative measures, recognize signs of illness early and be informed to use health care services, the speakers highlighted. Mr Mark Brown, the Minister of Finance in Cook Islands, said that current knowledge as well as new knowledge should reach not only school children but also adults, as they are the educators.

The growing interaction between education and climate change cannot be neglected, Ms Kandia Camara, Minister of National Education, Cote d’lvoire, said: “ There are school programs to teach healthy lifestyles and the importance of forests ,” actions are being taken to ensure climate-safe and climate-friendly school environments.

Furthermore, Mr Renato Janine Ribeiro, Minister of Education in Brazil, expressed the difficulty of eradicating poverty, “the challenge we face is ‘hunger, they live in places that are very difficult to access”, he said. Hence, geographic placement poses as a barrier to accessibility. Yet, in order to mitigate the problem with a collective effort, he asserted that Brazil would be happy to share its valuable experience on education for sustainable development with any country in order to bolster efforts.

Towards the end of the session, the CEO of the Campaign for Popular Education, Bangladesh, Ms Rasheda Choudhury, firmly stated: “ The two nonnegotiable principles are: first, education is a fundamental human right and second, it is the state’s responsibility to provide education to their every single citizen ”.

Other recent news

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

For this ring, I thee sue

Speech is never totally free

EVs fight warming but are costly. So why aren’t we driving $10,000 Chinese imports?

Bridget Long, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, addresses the impact of the COVID-19 crisis in the field of education.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Post-pandemic challenges for schools

Harvard Staff Writer

Ed School dean says flexibility, more hours key to avoid learning loss

With the closing of schools, the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed many of the injustices facing schoolchildren across the country, from inadequate internet access to housing instability to food insecurity. The Gazette interviewed Bridget Long, A.M. ’97, Ph.D. ’00, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education and Saris Professor of Education and Economics, regarding her views on the impact the public health crisis has had on schools, the lessons learned from the pandemic, and the challenges ahead.

Bridget Long

GAZETTE: The pandemic exposed many inequities that already existed in the education landscape. Which ones concern you the most?

LONG: Persistent inequities in education have always been a concern, but with the speed and magnitude of the changes brought on by the pandemic, it underscored several major problems. First of all, we often think about education as being solely an academic enterprise, but our schools really do so much more. Immediately, we saw children and families struggling with basic needs, such as access to food and health care, which our schools provide but all of a sudden were removed. We also shifted our focus, once we had to be in lockdown, to the differences in students’ home environments, whether it was lack of access to technology and the other commitments and demands on their time in terms of family situations, space, basic needs, and so forth. The focus had to shift from leveling the playing field within school or within college to instead what are the differences in inequities inside students’ homes and neighborhoods and the differences in the quality and rigor and supports available to students of different backgrounds. All of this was just exacerbated with the pandemic. There are concerns about learning loss and how that will vary across different income groups, communities, and neighborhoods. But there are also concerns about trauma and the mental health strain of the pandemic and how the strain of racial injustice and political turmoil has also been experienced — no doubt differently by different parts of population. And all of that has impacted students’ well-being and academic performance. The inequities we have long seen have become worse this year.

GAZETTE: Now that those inequities have been exposed, what can leaders in education do to navigate those issues? Are there any specific lessons learned?

LONG: Something that many educators already understood is that one size does not fit all. This is why education is so complex and why it has been so challenging to bring about improvements because there’s no silver bullet. The solution depends on the individual, the community, and the classroom.

At first, the public health crisis underscored that we needed to meet students where they are. This has been a long-held lesson among experienced education professionals, but it became even more important. In many respects, it butted up against some of our systems, which tried to come up with across-the-board approaches when instead what we needed was a bit of nimbleness depending on the context of the particular school or classroom and the individual needs of students.

Where you have seen some success and progress is where principals and teachers have been proactive and creative in how they can meet the needs of their students. What’s underneath all of this, regardless of whether we’re face-to-face or on technology, is the importance of people and personal connections. Education is a labor-intensive industry. Technology can help us in many respects to supplement or complement what we do, but the key has always been individual personal connection. Some teachers have been able to connect with their students, whether by phone or on Zoom, or schools, where they put concerted effort into doing outreach in the community to check on families to make sure they had basic needs. Some schools were able to understand what challenges their students were facing and were somewhat flexible and proactive to address those challenges, especially if they already had strong parental engagement. That’s where you have continued to see progress and growth.

“In many respects, this crisis forced the entire field to rethink our teaching in a way that I don’t know has happened before.”

GAZETTE: You spoke about concerns about learning loss. What can we do to avoid a lost year?

LONG: One of the difficulties is that the experience has differed tremendously. For some students, their parents have been able to supplement or their schools have been able to react. The hope is that they will not lose much learning time, while other students effectively haven’t been in school for almost a year; they have lost quite a bit of ground. As a teacher, you can imagine your students come back to school, and all of a sudden, students of the same chronological age are actually in very different places, depending on their individual family situation and what accommodations were able to be made. I think there’s a great deal we can do to try to address that. First of all, we have to have some understanding of what gains students have made as well as things they haven’t learned yet. That means taking a moment to see where a student is in their learning. The second thing is to make sure we’re capturing the lessons learned from this pandemic by identifying places where teachers and schools used a combination of technology, outreach, personal instruction, and tutors and mentors, and helped students make progress in their learning. We need to share those lessons more broadly so that other districts can see examples that have worked.

As we look ahead, I think it will take extending learning time to close the gaps. Schools will have to decide whether that is after school, weekends, or summer, and whether or not that’s going to involve the teachers themselves, or if it’s going to be using the best tools that are out there, such as videos and technology platforms that students and families use themselves. There has already been talk by some districts of extending the school year into summer or having summer-camp-type programs to give students additional time to work through some of the material.

The other important piece is partnerships. Schools oftentimes work with members of the community or nonprofit organizations, and that’s a really important layer in our system. After-school programs, enrichment programs, tutors, and mentors are essential, and we really want to continue with that expanded sense of capacity and partnership. It’s going to have an impact on all of us if we lose a generation, or if this generation goes backwards in terms of their learning. It certainly is in all of our best interests to try to contribute to the solution.

GAZETTE: Many parents gained renewed appreciation of the work teachers do. Do you think the pandemic would lead to a reappraisal of the profession?

LONG: Certainly, in the beginning, there was so much more appreciation for what teachers do. As parents needed to start doing homeschooling, there was a new understanding of just how difficult teaching is. Imagine having a classroom with different personalities, different strengths and assets, and also different weaknesses, and somehow being nimble enough to continue that class moving forward. As time has gone on, I worry a little bit about the level of contentiousness in some communities as schools haven’t reopened. There is the balancing act between caring for children’s learning and the fact that we have to make sure that the adults are safe and supported. You hear stories of teachers trying to teach from home while they are also homeschooling their own children. I would hope that coming out of this would be an appreciation of the amazing things teachers do in the classroom, as well as also some acknowledgement that these are people who are also living through a devastating pandemic with all the stress and strain that every individual is going through.

One other point is that given that we know that teachers do more than just academics, we need to make sure our teachers are trained to be able to provide social emotional support to students. As some of the students come back into the classroom, we need to acknowledge that they may be dealing with devastating losses, or the frustration of being kept inside, or the violence that is happening in their homes and neighborhoods. It’s very hard to learn if you’re first dealing with those kinds of issues. Our teachers already do so much, and we need to support them more and provide even more training to help them address that wide-ranging set of challenges their students may be facing even before they can get to the learning part.

“Something that many educators already understood is that one size does not fit all. This is why education is so complex and why it has been so challenging to bring about improvements because there’s no silver bullet.”

GAZETTE: Are there any silver linings in education brought on by the pandemic?

LONG: The first one is when we all needed to pivot last spring, and especially this fall, many educators took a moment to pause and reflect on their learning goals and priorities. There was a great deal of discussion, both in K‒12 and higher education, to think carefully and deliberately about the ways in which we could make sure our teaching was engaging and active and how we could bring in different voices and perspectives. In many respects, this crisis forced the entire field to rethink our teaching in a way that I don’t know has happened before. The second silver lining is the innovation and creativity. Because there wasn’t necessarily one right answer, you saw a lot of experimentation. We have seen an explosion of different approaches to teaching, and many more people got involved in that process, not just some small 10 percent of the teaching force. We’ve identified new ways of engaging with our students, and we’ve also increased the capacity of our educators to be able to deliver new ways of engagement. From this process, my hope is that we’ll walk away with even more tools and approaches to how we engage our students, so that we can then make choices about what to do face-to-face, how to use technology, and what to do in more of an asynchronous sort of way. But key to this is being able to share those lessons learned with others, how you were able to still maintain connection, how you were better able to teach certain material, and perhaps even build better relationships with parents and families during this process. Just the innovation, experimentation, and growth of instructors in many places has been very positive in so many respects.

GAZETTE: In which ways do you think the education system should be transformed after this year? How should it be rebuilt?

LONG: First, we’ve all had to understand that education and schools are not a spot on a map. They are actually communities; they have to include families, nonprofit organizations, and community-based organizations. For a university in particular, it’s not just about coming to campus; it’s actually about the people coming together, and how they are involved in learning from each other. It’s great to push on this reconceptualization and to be clear that education is an exchange of information, of perspective, of content, and making connections, regardless of the age of the student. The crisis has also forced us to go back to some of the fundamentals of what do we need students to learn, and how are we going to accomplish those goals. That has been a very important discussion for education. And the third part is realizing that education is not a one-size-fits-all. The best educators use multiple methods and approaches to be able to connect with their students, to be able to present material, and to provide support. That’s always been the case. How do we meet students where they are? That framing is one that I hope will not go away because all students have the potential to learn, and it’s a matter of how to personalize the learning experience to meet their needs, how we notice and provide supports to help learners who are struggling. That really is at the core of education, and I hope that we will take away that lesson as we look ahead.

GAZETTE: What do you think the role of higher education should be in this new educational landscape?

LONG: Higher education has an incredibly important role, and in particular given the economic recession. Traditionally, this is when many more people go into higher education to learn new skills, given what’s happening in the labor market. We have yet to see what the long-term impact is going to be, but in the short term, one thing we’ve noticed is that college enrollments are down. That’s very alarming and may have to do with how suddenly and how quickly the pandemic affected society. The first thing that higher education is going to have to think about is increasing proactive outreach — how to connect with potential students and how to help them get into programs that are going to give them skills necessary for this changing economy. Unfortunately, they’ll be doing this in a context where students are going to have greater needs, and where it’s not quite clear if funding from state and local governments is going to be declining. That’s the challenge that higher education will have to face. While it’s an amazing instrument in helping individuals further their skills or retool their skills, we need to make investments and make sure individuals can actually access the training available in our colleges and universities.

More like this

With revamped master’s program, School of Education faces fresh challenges

Seeded amid the many surprises of COVID times, some unexpected positives

Dental students fill the gap in online learning

GAZETTE: What are your hopes for the Biden administration in the area of education?

LONG: Government has a very important role in education, but it has to be balanced with the importance of local control and the fact that the context of every community is slightly different. Certainly, as we’ve been in the middle of a public health crisis, this has been incredibly challenging for schools. Schools had been trying to continue providing food and health care and connect with their students and, all of a sudden, they had to become experts in public health and buildings. This is something that falls under the purview of the federal government. Having access to the best doctors, the best public health officials, and people who think about buildings, and how to make things safe, the government needs to put that information together to give guidance to schools, principals, and teachers. It’s the government that can say, “Here are the risks, and here are the things you can do to mitigate those risks. Here are the conditions that are necessary for buildings. Here is what we know in terms of preventing spread, and here is what we know about the impact on children of different ages, and how we can protect the adults.” That kind of guidance would be incredibly helpful, as you have all of these individual school districts trying to sort through complex information and what the science says and how it applies to their particular context. Guidance is No. 1.

No. 2 is data. It’s very important having some understanding about where we stand in terms of learning loss, what we need to prioritize, and what areas of the country perhaps need more help than others. The other key component is to gauge what lessons have been learned and share the best practices across all school districts. The idea is to use the federal government as a central information bank with proactive outreach to schools. Government also plays a critical role in funding the research that will document the lessons from this pandemic.

It’s going to be incredibly helpful to have a more active federal government. As we have a better sense about where our students are the most vulnerable, and what are the kinds of high-impact practices that would be most beneficial, it’s going to be critical having the funding to support those kinds of investments because they will most certainly pay off. That possibility, I’m much more optimistic about now.

This interview has been condensed and edited for length and clarity

Share this article

You might like.

Unhappy suitor wants $70,000 engagement gift back. Now court must decide whether

Cass Sunstein suggests universities look to First Amendment as they struggle to craft rules in wake of disruptive protests

Experts say tension between trade, green-tech policies hampers climate change advances; more targeted response needed

Harvard releases race data for Class of 2028

Cohort is first to be impacted by Supreme Court’s admissions ruling

Parkinson’s may take a ‘gut-first’ path

Damage to upper GI lining linked to future risk of Parkinson’s disease, says new study

Professor tailored AI tutor to physics course. Engagement doubled.

Preliminary findings inspire other large Harvard classes to test approach this fall

Along with Stanford news and stories, show me:

- Student information

- Faculty/Staff information

We want to provide announcements, events, leadership messages and resources that are relevant to you. Your selection is stored in a browser cookie which you can remove at any time using “Clear all personalization” below.

Image credit: Claire Scully

New advances in technology are upending education, from the recent debut of new artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots like ChatGPT to the growing accessibility of virtual-reality tools that expand the boundaries of the classroom. For educators, at the heart of it all is the hope that every learner gets an equal chance to develop the skills they need to succeed. But that promise is not without its pitfalls.

“Technology is a game-changer for education – it offers the prospect of universal access to high-quality learning experiences, and it creates fundamentally new ways of teaching,” said Dan Schwartz, dean of Stanford Graduate School of Education (GSE), who is also a professor of educational technology at the GSE and faculty director of the Stanford Accelerator for Learning . “But there are a lot of ways we teach that aren’t great, and a big fear with AI in particular is that we just get more efficient at teaching badly. This is a moment to pay attention, to do things differently.”

For K-12 schools, this year also marks the end of the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief (ESSER) funding program, which has provided pandemic recovery funds that many districts used to invest in educational software and systems. With these funds running out in September 2024, schools are trying to determine their best use of technology as they face the prospect of diminishing resources.

Here, Schwartz and other Stanford education scholars weigh in on some of the technology trends taking center stage in the classroom this year.

AI in the classroom

In 2023, the big story in technology and education was generative AI, following the introduction of ChatGPT and other chatbots that produce text seemingly written by a human in response to a question or prompt. Educators immediately worried that students would use the chatbot to cheat by trying to pass its writing off as their own. As schools move to adopt policies around students’ use of the tool, many are also beginning to explore potential opportunities – for example, to generate reading assignments or coach students during the writing process.

AI can also help automate tasks like grading and lesson planning, freeing teachers to do the human work that drew them into the profession in the first place, said Victor Lee, an associate professor at the GSE and faculty lead for the AI + Education initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning. “I’m heartened to see some movement toward creating AI tools that make teachers’ lives better – not to replace them, but to give them the time to do the work that only teachers are able to do,” he said. “I hope to see more on that front.”

He also emphasized the need to teach students now to begin questioning and critiquing the development and use of AI. “AI is not going away,” said Lee, who is also director of CRAFT (Classroom-Ready Resources about AI for Teaching), which provides free resources to help teach AI literacy to high school students across subject areas. “We need to teach students how to understand and think critically about this technology.”

Immersive environments

The use of immersive technologies like augmented reality, virtual reality, and mixed reality is also expected to surge in the classroom, especially as new high-profile devices integrating these realities hit the marketplace in 2024.

The educational possibilities now go beyond putting on a headset and experiencing life in a distant location. With new technologies, students can create their own local interactive 360-degree scenarios, using just a cell phone or inexpensive camera and simple online tools.

“This is an area that’s really going to explode over the next couple of years,” said Kristen Pilner Blair, director of research for the Digital Learning initiative at the Stanford Accelerator for Learning, which runs a program exploring the use of virtual field trips to promote learning. “Students can learn about the effects of climate change, say, by virtually experiencing the impact on a particular environment. But they can also become creators, documenting and sharing immersive media that shows the effects where they live.”

Integrating AI into virtual simulations could also soon take the experience to another level, Schwartz said. “If your VR experience brings me to a redwood tree, you could have a window pop up that allows me to ask questions about the tree, and AI can deliver the answers.”

Gamification

Another trend expected to intensify this year is the gamification of learning activities, often featuring dynamic videos with interactive elements to engage and hold students’ attention.

“Gamification is a good motivator, because one key aspect is reward, which is very powerful,” said Schwartz. The downside? Rewards are specific to the activity at hand, which may not extend to learning more generally. “If I get rewarded for doing math in a space-age video game, it doesn’t mean I’m going to be motivated to do math anywhere else.”

Gamification sometimes tries to make “chocolate-covered broccoli,” Schwartz said, by adding art and rewards to make speeded response tasks involving single-answer, factual questions more fun. He hopes to see more creative play patterns that give students points for rethinking an approach or adapting their strategy, rather than only rewarding them for quickly producing a correct response.

Data-gathering and analysis

The growing use of technology in schools is producing massive amounts of data on students’ activities in the classroom and online. “We’re now able to capture moment-to-moment data, every keystroke a kid makes,” said Schwartz – data that can reveal areas of struggle and different learning opportunities, from solving a math problem to approaching a writing assignment.

But outside of research settings, he said, that type of granular data – now owned by tech companies – is more likely used to refine the design of the software than to provide teachers with actionable information.

The promise of personalized learning is being able to generate content aligned with students’ interests and skill levels, and making lessons more accessible for multilingual learners and students with disabilities. Realizing that promise requires that educators can make sense of the data that’s being collected, said Schwartz – and while advances in AI are making it easier to identify patterns and findings, the data also needs to be in a system and form educators can access and analyze for decision-making. Developing a usable infrastructure for that data, Schwartz said, is an important next step.

With the accumulation of student data comes privacy concerns: How is the data being collected? Are there regulations or guidelines around its use in decision-making? What steps are being taken to prevent unauthorized access? In 2023 K-12 schools experienced a rise in cyberattacks, underscoring the need to implement strong systems to safeguard student data.

Technology is “requiring people to check their assumptions about education,” said Schwartz, noting that AI in particular is very efficient at replicating biases and automating the way things have been done in the past, including poor models of instruction. “But it’s also opening up new possibilities for students producing material, and for being able to identify children who are not average so we can customize toward them. It’s an opportunity to think of entirely new ways of teaching – this is the path I hope to see.”

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Here’s where Trump and Harris stand on 6 education issues

Cory Turner

How the candidates differ on their views and policies on education

Presidential candidates Kamala Harris and Donald Trump will face off in a debate on Tuesday. LA Johnson/NPR hide caption

As presidential candidates, Kamala Harris and Donald Trump don’t have a lot in common when it comes to their views on education.

Trump has said America’s public schools “have been taken over by the radical Left maniacs,” and that he wants to close the U.S. Department of Education.

2024 Election

Stop stressing about the polls. watch these four indicators in the election.

Harris has vowed to keep the department open.

Democrats are for free, universal preschool for all 4-year-olds.

Republicans are for universal school choice, where parents have the power — and the public dollars — to enroll their children in any school they want, whether it’s public or private.

6 takeaways from Harris' interview on CNN

The list goes on.

Ahead of the candidates’ only scheduled debate, in Philadelphia on Tuesday, we’ve put together a handy primer of their education views.

1. On closing the U.S. Department of Education

Trump, in an interview on X , told Elon Musk that, if elected, “I want to close up the Department of Education, move education back to the states.”

Harris didn’t talk much about education in her DNC speech , but she did parry Trump’s plan: “We are not going to let him eliminate the Department of Education that funds our public schools.”

A quick explanatory comma about that funding: Most public school funding comes from states and local communities. But the department does administer two large funding streams, now more than $30 billion, that Congress codified into law decades ago to help schools educate 1.) children with disabilities and 2.) kids living in low-income communities.

'I'll be voting no.' Trump clarifies his stance on the abortion amendment in Florida

It’s not clear if Trump’s desire to close the department would also mean disrupting this funding.

Project 2025, a blueprint for the next Republican presidency that included input from Trump loyalists, recommends closing the department, turning both funding streams into no-strings-attached grants and phasing out the low-income support dollars within 10 years.

But the Trump campaign has disavowed Project 2025. NPR asked the campaign to clarify its position on funding for children with disabilities and kids living in low-income communities, and press secretary Karoline Leavitt responded: “ President Trump will ensure a great education for every child by returning our education system to the states where it belongs.”

Biden administration adds Title IX protections for LGBTQ students, assault victims

The Education Department debate isn’t just financial. It’s also symbolic.

Trump and some Republicans believe, fundamentally, that education should only be a local and state concern, as there’s no mention of a federal role in education in the U.S. Constitution. To them the department is the poster child for government overreach, which is why Republicans have been calling for the department’s dissolution ever since it was created in 1979.

Where Republicans see local control of education as an inherently good thing, allowing schools to better reflect the values of their communities, Harris and many Democrats also see inequity in some districts’ inability (and sometimes unwillingness) to serve marginalized students.

Congress created those funding streams to help level the playing field and to give the department the ability to hold districts accountable when they fall short on civil rights. Harris has previously backed increasing funding for low-income students and children with disabilities.

Disagreements aside, can the department be shut down?

How schools (but not necessarily education) became central to the Republican primary

Not by the president, no. It was created by Congress, and only Congress can close it. Some House Republicans have tried , but there’s simply not enough support, not just among Democrats but Republicans, too. Public surveys show even a majority of Republicans believe the U.S. government should be spending more, not less, on education.

Keep in mind, eight years ago then-presidential candidate Donald Trump suggested he might try to close the Education Department. He then got his chance as president — with Republican control of Congress — but never forced the issue.

2. On sex-based discrimination in schools, aka Title IX

In April, the Biden-Harris administration expanded protections against sex discrimination in schools to include sexual orientation and gender identity. Meaning, among other things, it believes students should be allowed to use the bathroom that corresponds with their gender identity.

The Promise And Peril Of School Vouchers

This is not a change in federal law. That requires Congress. It’s a change in interpretation of the law, known as Title IX, courtesy of new regulations from the U.S. Department of Education.

Trump and many Republicans see this expanded interpretation of Title IX as Democrats imposing liberalism on schools. In a recent call with reporters, representatives of the Trump campaign and the RNC repeatedly derided what they called Harris’ “radical gender ideology.”

The expanded child tax credit briefly slashed child poverty. Here's what else it did

If this sounds all-too-familiar, that’s because this is an old fight. In 2016, the Obama administration issued guidance to schools , telling them that students should be allowed to use the bathroom facilities that correspond with their gender identity.

In early 2017, the nascent Trump administration quickly moved in the opposite direction, abandoning that interpretation of the law.

Protesting these latest Biden administration provisions, roughly half of all states have sued the department, and the courts have blocked the Education Department from enforcing the regulations in those states. Trump has said, if re-elected, he would roll back the rule, just as he did the old Obama-era guidance.

3. On school choice

We’re using “choice” here broadly because many of Trump’s education proposals shoot from the same root: That parents should have total or near-total control over their child’s education.

First, he’s calling for universal school choice. This would, in theory, take public dollars normally spent on a child’s public education and give them directly to parents to spend at whatever school they want, whether it’s public, private or homeschooling at the kitchen table.

Report: Last year ended with a surge in book bans

He has also called for a Parental Bill of Rights and for school principals to be hired — and fired — by parents. “If any principal is not getting the job done, the parents should be able to vote to fire them and select someone who will. This will be the ultimate form of local control,” Trump said in July.

Trump also wants to make it easier to fire “bad” teachers, by ending tenure protections, and to reward strong teachers with merit pay. “If we have pink-haired Communists teaching our kids, we have a major problem. When I am president, we will put PARENTS back in charge and give them the final say,” he said.

It’s difficult to imagine how a second Trump administration could implement these ideas around school choice or principal and teacher retention, though, as the U.S. government has limited power to influence state and school district policy.

Democrats, on the other hand, made clear in their 2024 platform that they’re against any effort that could weaken the nation’s public schools. “We oppose the use of private-school vouchers, tuition tax credits, opportunity scholarships, and other schemes that divert taxpayer-funded resources away from public education. Public tax dollars should never be used to discriminate.”

That’s likely a reference to the fact that, in some state voucher programs, a private school is allowed to reject children with disabilities if it doesn’t believe it has the staff or resources to meet their needs. Federal law requires that schools that receive federal funding provide kids with disabilities a free and appropriate public education.

The Student Loan Restart

What the supreme court's rejection of student loan relief means for borrowers.

In a letter to Harris , some two-dozen grassroots education groups urged her not to choose Pennsylvania Gov. Josh Shapiro to be her running mate, because of his previous support for private-school vouchers . She ultimately chose Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz, a former public school teacher and coach.

Harris has been an outspoken supporter of public education and has been courting educators’ support. In a speech to the American Federation of Teachers, she told the crowd, “We need you so desperately right now,” and called it “the most noble of work, teaching other people’s children.”

As part of her presidential bid in 2019, Harris proposed a $300 billion plan to raise teacher pay. Though she has not revived the plan, she did tell the AFT, “God knows we don’t pay you enough.”

4. On early childhood education and support

Harris and Democrats have talked as much, if not more, about early childhood education and childcare than they have about K-12 policies. Harris has proposed expanding the Child Tax Credit after a brief, pandemic-era expansion dramatically cut child poverty , and she pitched an even larger boost of up to $6,000 for newborns.

The Democrats’ 2024 platform also includes support for free, universal preschool for 4-year-olds, something the Biden-Harris administration had previously championed but was forced to abandon in negotiations with Congress.

Finally, there’s Head Start, the federally-funded program that provides child care and early learning for children from low-income families. The Biden-Harris administration has been a staunch supporter of Head Start, which serves children from birth to age 5. In her DNC speech , Harris promised not to let Trump “end programs like Head Start that provide preschool and child care.”

Harris was likely referring, again, to Project 2025 , which alleges Head Start is “fraught with scandal and abuse” and recommends eliminating it entirely. Congressional funding for Head Start rose during the Trump administration, in spite of the White House calling for modest cuts .

NPR asked the Trump campaign to clarify its position on Head Start funding. Press Secretary Karoline Leavitt responded: “By returning our education system back to the states, our early childhood education system will thrive because parents will have more say in their child’s education and good teachers will be rewarded.”

5. On banning books and “divisive concepts”

Between July and December 2023, PEN America recorded more than 4,300 instances of school book bans, a big uptick from the previous year.

Of the books that were targeted in the 2021-’22 and ‘22-’23 school years, the nonprofit found that 37% grappled with race and racism and included characters of color, and 36% included LGBTQ+ characters and themes.

Trump has been an unabashed champion of efforts to limit how schools approach issues of race and gender. In 2020, he created the 1776 Commission , which lamented that “many students are now taught in school to hate their own country, and to believe that the men and women who built it were not heroes, but rather villains.”

Since then, some states have passed laws curtailing what teachers can and cannot say in the classroom when it comes to matters of race and gender. And in July, as part of his Plan To Save American Education , Trump pledged to “cut federal funding for any school or program pushing Critical Race Theory, gender ideology, or other inappropriate racial, sexual, or political content,” though it’s not clear how or if he could do that.

Kamala Harris used her speech before the American Federation of Teachers to blast Trump.

“While you teach students about our nation’s past,” she told the crowd of teachers, “these extremists attack the freedom to learn and acknowledge our nation’s true and full history, including book bans. Book bans in this year of our Lord 2024.”

6. On college affordability

The Biden-Harris administration went all-in on federal student loan forgiveness. Some of its plans worked , but the administration has so far failed to convince the courts that its most ambitious efforts at loan forgiveness are legal.

That may explain why, on the campaign trail, Harris isn’t talking much about future loan forgiveness, or making new promises. Instead, she’s largely backward-looking.

“Our administration has forgiven student loan debt for nearly 5 million Americans,” Harris told the American Federation of Teachers gathering, emphasizing that many of those Americans are teachers who received Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF).

As a senator and vice president, Harris has also supported efforts to make community college free, a commitment echoed in the 2024 Democratic party platform .

As for Trump, as president he previously tried to eliminate PSLF , and he and his running mate, Ohio Sen. JD Vance, have both spoken out against broad loan forgiveness.

In 2023, after the Supreme Court blocked Biden’s first big effort, Trump celebrated : “President Biden is not allowed to wipe out hundreds and hundreds of billions, probably trillions, of dollars in student loan debt, which would have been very unfair to the millions and millions of people who have paid their debt through hard work and diligence.”

The 2024 Republican party platform pledges , “to reduce the cost of Higher Education, Republicans will support the creation of additional, drastically more affordable alternatives to a traditional four-year College degree.”

Last year, Trump unveiled plans for an online college alternative he’s calling The American Academy: “We will take the billions and billions of dollars that we will collect by taxing, fining, and suing excessively large private university endowments, and we will then use that money to endow a new institution… Its mission will be to make a truly world-class education available to every American, free of charge, and do it without adding a single dime to the federal debt.”

Considering more than 70 million American students are enrolled in school, from K-12 to college , let’s hope the candidates get a chance to debate their ideas and their differences on Tuesday.

- presidential elections

- public schools

- higher education

- Donal Trump

- Kamala Harris

Peter DeWitt's

Finding common ground.

A former K-5 public school principal turned author, presenter, and leadership coach, Peter DeWitt provides insights and advice for education leaders. Former superintendent Michael Nelson is a frequent contributor. Read more from this blog .

12 Critical Issues Facing Education in 2020

- Share article

Education has many critical issues; although if you watch the nightly news or 24/7 news channels, you will most likely see very little when it comes to education. Our political climate has taken over the news, and it seems as though education once again takes a back seat to important political events as well as salacious stories about reality-television stars. It sometimes make me wonder how much education is valued?

Every year around this time, I highlight some critical issues facing education. It’s not that I am trying to rush the holiday season by posting it well before the 1 st of the new year. It’s actually that I believe we should have a critical look at the issues we face in education, and create some dialogue and action around these issues, and talk about them sooner than later.

Clearly, the fact that we are entering into 2020 means we need to look at some of these issues with hindsight because we have seen them before. Have the issues of the past changed or do they continue to impact our lives? As with any list, you will notice one missing that you believe should be added. Please feel free to use social media or the comment box at the end of this blog to add the ones you believe should be there.

12 Issues Facing Education

These issues are not ranked in order of importance. I actually developed a list of about 20 critical issues but wanted to narrow it down to 12. They range from issues that impact our lives in negative ways to issues that impact our lives in positive ways, and I wanted to provide a list of issues I feel educators will believe are in their control.

I have spent the better part of 2019 on the road traveling across the U.S., Canada, Europe, the U.K., and Australia. The issues that are highlighted below have come up in most of those countries, but they will be particularly important for those of us living in the U.S. There are a couple that seem to be specifically a U.S. issue, and that will be obvious to you when you see them.

Health & Wellness - Research shows that many of our students are stressed out , anxiety-filled, and at their breaking point. Teachers and leaders are experiencing those same issues. Whether it’s due to social media, being overscheduled, or the impact of high-stakes testing and pressure to perform, this needs to be the year where mindfulness becomes even more important than it was in 2019. Whether it’s using mindfulness apps and programs or the implementation of double recess in elementary school and frequent brain beaks throughout the day, it’s time schools are given the autonomy to help students find more balance.

Literacy - We have too many students not reading with proficiency, and therefore, at risk of missing out on the opportunity to reach their full potential. For decades there have been debates about whole language and phonics while our students still lag behind. It’s time to put a deep focus on teaching literacy with a balanced approach.

School Leadership - Many school leaders enter into the position with high hopes of having a deep impact but are not always prepared for what they find. School leadership has the potential to be awesome. And when I mention school leadership, I am also referring to department chairs, PLC leads, or grade-level leaders. Unfortunately, not all leaders feel prepared for the position. Leadership is about understanding how to get people to work together, having a deep understanding of learning, and building the capacity of everyone around them. This means that university programs, feeder programs, and present leaders who coach those who want to be leaders, need to find ways to expose potential leaders to all of the goodness, as well as the hardships, that come with the position.

Our Perception of Students - For the last year I have been involved in some interesting dialogue in schools. One of the areas of concern is the perception educators (i.e. leaders, teachers, etc.) have of their students. Sometimes we lower our expectations of students because of the background they come from, and other times we hold unreachable expectations because we believe our students are too coddled. And even worse, I have heard educators talk about certain students in very negative ways, with a clear bias that must get in the way of how they teach those students. Let 2020 be a year when we focus on our perception of students and address those biases that may bleed into our teaching and leading.

Cultures of Equity - I learned a long time ago that the history I learned about in my K-12 education was a white-washed version of it all. There is more than one side to those stories, and we need all of them for a deeper understanding of the world. Read this powerful guest blog by Michael Fullan and John Malloy for a deeper look into cultures of equity.

Additionally, we have an achievement gap with some marginalized populations (i.e., African American boys), and have other marginalized populations (i.e., LGBTQ) who do not feel safe in school. Isn’t school supposed to be a safe place where every student reaches their full potential?

Students and the schools they attend need to be provided with equitable resources, and we know that is not happening yet. My go-to resource is always Rethinking Schools .

District Office/Building-Level Relationships - There are too many school districts with a major disconnection between the district office and building level leaders. 2020 needs to be the year when more district offices find a balance between the top-down initaitives that take place, and creating more space to engage in dialogue with building leaders and teachers. School districts will likely never improve if people are constantly told what to do and not given the opportunity to share the creative side that probably got them hired in the first place.

Politics - It’s an election year. Get ready for the wave of everything that comes with it. Negative campaigns and bad behavior by adults at the same time we tell students to be respectful to each other. It’s important for us to open up this dialogue in our classrooms, and talk about how to respectfully agree or disagree. Additionally, we have to wonder how the campaigns and ultimate presidential decision will impact education because the last few education secretaries have not given us all that much to cheer about.

Our Perception of Teachers - Over the last few decades there has been a concerted effort to make teachers look as though they chose teaching because they could not do anything else. Whether it be in political rhetoric or through the media and television programs, our dialogue has not been kind, and it has led to a negative perception of teachers. This rhetoric has not only been harmful to school climates, it has turned some teachers into passive participants in their own profession. Teachers are educated, hardworking professionals who are trying to help meet the academic and social-emotional needs of their students, which is not always easy.

Vaping - Many of the middle and high schools in the U.S. that I am working with are experiencing too many students who vape, and some of those students are doing it in class. In fact, this NBC story shows that there has been a major spike in the use of vaping among adolescents. Additionally This story shows that vaping is a major health crisis , and it will take parents, schools, and society to put a dent in it.

Time on Task vs. Student Engagement - For too long we have agreed upon words like “Time on task,” which often equates to students being passive in their own learning. It’s time we focus on student engagement, which allows us to go from surface to deep level learning and on to transfer level learning. It also helps balance the power in the room between adults and students.

Teachers With guns - I need to be honest with you; this one was not easy to add to the list, and it is very much a U.S. issue. I recently saw this story on NBC Nightly News with Lester Holt that focused on teachers in Utah being trained to shoot guns in case of an active shooter in their school. This is a story that we will see more of in 2020.

Climate Change - Whether it’s because they were inspired by Greta Thunberg (Time Person of the Year) or the years of hearing about climate change in school and at home, young people will continue to rise up and make climate change a critical issue in 2020. We saw thousands of students strike this year and that will surely rise after Thunberg’s latest recognition.

In the End - It’s always interesting to reflect on the year and begin compiling a list of critical issues. I know it can be daunting to look at, and begin to see where we fit into all of this, but I have always believed that education is about taking on some of this crucial issues and turning them around to make them better. Anyone who gets into teaching needs to believe that they can improve the educational experience for their students, and these are just a few places to start.

Peter DeWitt, Ed.D. is the author of several books including Coach It Further: Using the Art of Coaching to Improve School Leadership (Corwin Press. 2018), and Instructional Leadership: Creating Practice Out Of Theory (Corwin Press. 2020). Connect with him on Twitter , Instagram or through his YouTube station .

Photo courtesy of Getty Images.

The opinions expressed in Peter DeWitt’s Finding Common Ground are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Titans present unique challenge for Caleb Williams as he tries to accomplish rare feat in Week 1

Caleb williams can join a small group of quarterbacks with a win in week 1, by josh schrock, bears insider • published september 4, 2024 • updated on september 4, 2024 at 5:13 pm.

LAKE FOREST, Ill. -- All eyes will be on Bears quarterback Caleb Williams on Sunday when the No. 1 overall pick makes his official NFL debut against the Tennessee Titans at Soldier Field.

Expectations for the 2022 Heisman Trophy winner are stratospheric as he begins his NFL career and hopeful march toward stardom. Both Williams and the Bears know there will be adversity during his rookie season. Even the best rookie quarterbacks suffer body blows from NFL defenses. The key is understanding how to rebound when you get knocked back.

"Understanding that the situation I’m in, bad things are going to happen every once in a while," Williams said Wednesday at Halas Hall. "You’re going to throw a pick. You’re going to fumble. Whether it’s me, whether it’s the team, whether it’s we’re going to jump offsides, we’re going to do a bunch of things. When those moments of adversity strike, it’s more about encouraging, it’s more about understanding that we can get out of this situation and not bringing more negativity to the situation that comes up.

Stay in the game with the latest updates on your beloved Chicago sports teams! Sign up here for our All Access Daily newsletter.

"I think the communication and information part and also just understanding that there’s going to be a lot more times - obviously you can’t be doing it every single drive or every single play - but there’s going to be a lot more times throughout the games or practices where there’s going to be a lot more good than bad. You just can’t let the bad outweigh the good."

On Sunday, Williams will look to become the first quarterback drafted No. 1 overall to win a season opener since David Carr in 2002. Since Carr's win over the Dallas Cowboys, No. 1 overall picks are 0-8-1 in season-openers, with Kyler Murray and the Arizona Cardinals getting a tie in 2019.

Quarterbacks taken No. 1 overall are 0-14-1 in their first career starts since Carr won in 2002. That number includes the likes of Carson Palmer and Baker Mayfield who were drafted No. 1 overall but did not start the season-opener in their rookie year.

Palmer sat for his entire rookie campaign but lost his first career start in 2004. Mayfield started his rookie season behind Tyrod Taylor before eventually taking over as starter after Taylor suffered an injury. Mayfield entered in the middle of a Week 3 game against the New York Jets and led the Browns to a win. But his first-career start came one week later in a loss to the Oakland Raiders.