- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Writing Systems and Their Use

An overview of grapholinguistics.

- Dimitrios Meletis and Christa Dürscheid

- Funded by: Schweizerischer Nationalfonds (SNF)

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: De Gruyter Mouton

- Copyright year: 2022

- Audience: Scholars and Researchers of Linguistics, Semiotics, Psycholinguistics, Sociolinguistics, Anthropology, Cognitive Sciences

- Front matter: 9

- Main content: 317

- Illustrations: 21

- Coloured Illustrations: 4

- Keywords: Writing Systems ; Grapholinguistics ; Literacy ; Orthography

- Published: June 21, 2022

- ISBN: 9783110757835

- Published: July 5, 2022

- ISBN: 9783110757774

A systematic review of automated writing evaluation systems

- Published: 07 July 2022

- Volume 28 , pages 771–795, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Shi Huawei 1 &

- Vahid Aryadoust ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6960-2489 1

2859 Accesses

19 Citations

10 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

A Correction to this article was published on 01 August 2022

This article has been updated

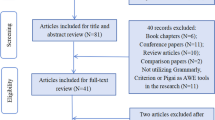

Automated writing evaluation (AWE) systems are developed based on interdisciplinary research and technological advances such as natural language processing, computer sciences, and latent semantic analysis. Despite a steady increase in research publications in this area, the results of AWE investigations are often mixed, and their validity may be questionable. To yield a deeper understanding of the validity of AWE systems, we conducted a systematic review of the empirical AWE research. Using Scopus, we identified 105 published papers on AWE scoring systems and coded them within an argument-based validation framework. The major findings are: (i) AWE scoring research had a rising trend, but was heterogeneous in terms of the language environments, ecological settings, and educational level; (ii) a disproportionate number of studies were carried out on each validity inference, with the evaluation inference receiving the most research attention, and the domain description inference being the neglected one, and (iii) most studies adopted quantitative methods and yielded positive results that backed each inference, while some studies also presented counterevidence. Lack of research on the domain description (i.e., the correspondence between the AWE systems and real-life writing tasks) combined with the heterogeneous contexts indicated that construct representation in the AWE scoring field needs extensive investigation. Implications and directions for future research are also discussed.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Subscribe and save.

- Get 10 units per month

- Download Article/Chapter or eBook

- 1 Unit = 1 Article or 1 Chapter

- Cancel anytime

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Towards automated writing evaluation: A comprehensive review with bibliometric, scientometric, and meta-analytic approaches

Automated writing evaluation systems: A systematic review of Grammarly, Pigai, and Criterion with a perspective on future directions in the age of generative artificial intelligence

Trends in automated writing evaluation systems research for teaching, learning, and assessment: A bibliometric analysis

Data availability.

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as the datasets generated during the current study are proprietary of Scopus. Using the search code discussed in the paper, interested readers who have access to Scopus can replicate the dataset.

Change history

01 august 2022.

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11260-9

The papers included in the review are numbered and listed in a supplementary file which can be found in the Appendix.

* Refers to papers that are also included in the dataset.

Aryadoust, V. (2013). Building a validity argument for a listening test of academic proficiency. Cambridge Scholars Publishing

*Attali, Y. (2015). Reliability-based feature weighting for automated essay scoring [Article]. Applied Psychological Measurement , 39(4), 303-313. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146621614561630

Bennett, R. E., & Bejar, I. I. (1998). Validity and automated scoring: It’s not only the scoring. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 17 (4), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.1998.tb00631.x

Article Google Scholar

Bridgeman, B. (2013). Human ratings and automated essay evaluation. In M. D. Shermis & J. Burstein (Eds.), Handbook of Automated Essay Evaluation: Current Applications and New Directions pp. 243–254. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

*Bridgeman, B., & Ramineni, C. (2017). Design and evaluation of automated writing evaluation models: Relationships with writing in naturalistic settings [Article]. Assessing Writing , 34 , 62-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2017.10.001

*Burstein, J., Elliot, N., & Molloy, H. (2016). Informing automated writing evaluation using the lens of genre: Two studies [Article]. CALICO Journal , 33 (1), 117-141. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.v33i1.26374

Burstein, J., Riordan, B., & McCaffrey, D. (2020). Expanding automated writing evaluation. In D. Yan, A. A. Rupp, & P. Foltz (Eds.), Handbook of automated scoring: Theory into practice (pp. 329–346). Taylor and Francis Group/CRC Press.

Chapter Google Scholar

Chapelle, C., Enright, M., & Jamieson, J. (2008). Building a validity argument for the test of English as a foreign language . Routledge.

Google Scholar

*Cohen, Y., Levi, E., & Ben-Simon, A. (2018). Validating human and automated scoring of essays against “True” scores. Applied Measurement in Education , 31(3), 241–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/08957347.2018.1464450

Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52 (4), 281–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040957

Deane, P. (2013). On the relation between automated essay scoring and modern views of the writing construct. Assessing Writing, 18 (1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2012.10.002

Dursun, A., & Li, Z. (2021). A systematic review of argument-based validation studies in the field of Language Testing (2000–2018). In C. Chapelle & E. Voss (Eds.), Validity argument in language testing: Case studies of validation research (Cambridge Applied Linguistics) (pp. 45–70). Cambridge University Press.

Ericsson, P. F., & Haswell, R. (Eds.). (2006). Machine scoring of student essays: Truth and consequences . Utah State University Press.

Enright, M. K., & Quinlan, T. (2010). Complementing human judgment of essays written by English language learners with e-rater® scoring [Article]. Language Testing, 27 (3), 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532210363144

Fan, J., & Yan, X. (2020). Assessing speaking proficiency: A narrative review of speaking assessment research within the argument-based validation framework. Frontiers in Psychology, 11 , 330. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00330

*Gerard, L. F., & Linn, M. C. (2016). Using automated scores of student essays to support teacher guidance in classroom inquiry. Journal of Science Teacher Education , 27(1), 111-129. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-016-9455-6

*Grimes, D., & Warschauer, M. (2010). Utility in a fallible tool: A multi-site case study of automated writing evaluation. Journal of Technology, Learning, and Assessment, 8(6), 1–44. Retrieved from http://www.jtla.org

Hockly, N. (2018). Automated writing evaluation. ELT Journal, 73 (1), 82–88. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccy044

Im, G. H., Shin, D., & Cheng, L. (2019). Critical review of validation models and practices in language testing: Their limitations and future directions for validation research. Language Testing in Asia, 9 (1), 14.

*James, C. L. (2008). Electronic scoring of essays: Does topic matter? Assessing Writing , 13(2), 80-92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2008.05.001

Kane, M. (2013). Validating the Interpretations and uses of test scores. Journal of Educational Measurement, 50 (1), 1–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12000

Keith, T. Z. (2003). Validity and automated essay scoring systems. In M. D. Shermis & J. Burstein (Eds.), Automated essay scoring: A cross-disciplinary perspective (pp. 147–168). Erlbaum.

*Klobucar, A., Elliot, N., Deess, P., Rudniy, O., & Joshi, K. (2013). Automated scoring in context: Rapid assessment for placed students. Assessing Writing , 18(1), 62–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2012.10.001

Lamprianou, I., Tsagari, D., & Kyriakou, N. (2020). The longitudinal stability of rating characteristics in an EFL examination: Methodological and substantive considerations. Language Testing . https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532220940960

Lee, Y. W., Gentile, C., & Kantor, R. (2010). Toward automated multi-trait scoring ofessays: Investigating links among holistic, analytic, and text feature scores [Article]. Applied Linguistics, 31 (3), 391–417. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amp040 .

*Li, J., Link, S., & Hegelheimer, V. (2015). Rethinking the role of automated writing evaluation (AWE) feedback in ESL writing instruction. Journal of Second Language Writing , 27, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2014.10.004

Li, S., & Wang, H. (2018). Traditional literature review and research synthesis. In A. Phakiti, P. De Costa, L. Plonsky, & S. Starfield (Eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of applied linguistics research methodology (pp. 123–144). Palgrave-MacMillan.

Liu, S., & Kunnan, A. J. (2016). Investigating the application of automated writing evaluation to Chinese undergraduate English majors: A case study of WritetoLearn. CALICO Journal, 33 (1), 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1558/cj.v33i1.26380 .

Messick, S. (1989). Validity. In R. L. Linn (Ed.), Educational measurement (3rd ed., pp. 13–103). American Council on Education and Macmillan.

Mislevy, R. (2020). An evidentiary-reasoning perspective on automated scoring: Commentary on part I. In D. Yan, A. A. Rupp, & P. Foltz (Eds.), Handbook of automated scoring: Theory into practice (pp. 151–167). Taylor and Francis Group/CRC Press.

National Council of Teachers of English. (2013). NCTE position statement on machine scoring. https://ncte.org/statement/machine_scoring/

Phakiti, A., De Costa, P., Plonsky, L., & Starfield, S. (2018). Applied linguistics research: Current issues, methods, and trends. In A. Phakiti, P. De Costa, L. Plonsky, & S. Starfield (Eds.) The Palgrave Handbook of Applied Linguistics Research Methodology pp. 5–29. Palgrave-MacMillan

*Perelman, L. (2014). When "the state of the art" is counting words. Assessing Writing , 21, 104-111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2014.05.001

*Powers, D. E., Burstein, J. C., Chodorow, M., Fowles, M. E., & Kukich, K. (2002a). Stumping e-rater: challenging the validity of automated essay scoring. Computers in Human Behavior , 18(2), 103–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0747-5632(01)00052-8

*Powers, D. E., Burstein, J. C., Chodorow, M. S., Fowles, M. E., & Kukich, K. (2002b). Comparing the validity of automated and human scoring of essays. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 26(4), 407-425. https://doi.org/10.1092/UP3H-M3TE-Q290-QJ2T

*Qian, L., Zhao, Y., & Cheng, Y. (2020). Evaluating China’s Automated Essay Scoring System iWrite [Article]. Journal of Educational Computing Research , 58(4), 771-790. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735633119881472

Ramesh, D., & Sanampudi, S. K. (2021). An automated essay scoring systems: A systematic literature review. Artificial Intelligence Review, 55 (3), 2495–2527. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10462-021-10068-2

Ramineni, C., & Williamson, D. M. (2013). Automated essay scoring: Psychometricguidelines and practices. Assessing Writing, 18 (1), 25–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2012.10.004 .

*Ramineni, C., & Williamson, D. (2018). Understanding mean score differences between the e-rater® automated scoring engine and humans for demographically based groups in the GRE® General Test. ETS Research Report Series , 2018(1), 1-31. https://doi.org/10.1002/ets2.12192

*Reilly, E. D., Stafford, R. E., Williams, K. M., & Corliss, S. B. (2014). Evaluating the validity and applicability of automated essay scoring in two massive open online courses. International Review of Research in Open and Distance Learning , 15(5), 83–98. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v15i5.1857

Reilly, E. D., Williams, K. M., Stafford, R. E., Corliss, S. B., Walkow, J. C., & Kidwell, D. K. (2016). Global times call for global measures: Investigating automated essay scoring in linguisticallydiverse MOOCs. Online Learning Journal, 20 (2). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v20i2.638 ; https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v15i5.1857

Riazi, M., Shi, L., & Haggerty, J. (2018). Analysis of the empirical research in the journal of second language writing at its 25th year (1992–2016). Journal of Second Language Writing, 41 , 41–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jslw.2018.07.002

Richardson, M. & Clesham, R. (2021) ‘Rise of the machines? The evolving role of AI technologies in high-stakes assessment’. London Review of Education , 19 (1), 9, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.14324/LRE.19.1.09

Rotou, O., & Rupp, A. A. (2020). Evaluations of Automated Scoring Systems inPractice. ETS Research Report Series, 2020 (1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/ets2.12293 .

Sarkis-Onofre, R., Catalá-López, F., Aromataris, E., & Lockwood, C. (2021). How to properly use the PRISMA Statement. Systematic Reviews , 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-021-01671-z

Sawaki, Y., & Xi, X. (2019). Univariate generalizability theory in language assessment. In V. Aryadoust & M. Raquel (Eds.), Quantitative data analysis for language assessment (Vol. 1, pp. 30–53). Routledge.

Schotten, M., Aisati, M., Meester, W. J. N., Steigninga, S., & Ross, C. A. (2018). A brief history of Scopus: The world’s largest abstract and citation database of scientific literature. In F. J. Cantu-Ortiz (Ed.), Research analytics: Boosting university productivity and competitiveness through Scientometrics (pp. 33–57). Taylor & Francis.

*Shermis, M. D. (2014). State-of-the-art automated essay scoring: Competition, results, and future directions from a United States demonstration. Assessing Writing , 20, 53-76.

Shermis, M. D. (2020). International application of Automated Scoring. In D. Yan, A. A. Rupp, & P. Foltz (Eds.), Handbook of automated scoring: Theory into practice (pp. 113–132). Taylor and Francis Group/CRC Press.

Shermis, M. D., & Burstein, J. (2003). Introduction. In M. D. Shermis & J. Burstein (Eds.), Automated essay scoring: A cross-disciplinary perspective (pp. xiii–xvi). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Shermis, M. D., Burstein, J., & Bursky, S. A. (2013). Introduction to automated essay evaluation. In M. D. Shermis & J. Burstein (Eds.), Handbook of automated essay evaluation: Current applications and new directions (pp. 1–15). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Shermis, M., Burstein, J., Elliot, N., Miel, S., & Foltz, P. (2016). Automated writing evaluation: A growing body of knowledge. In C. MacArthur, S. Graham, & J. Fitzgerald (Eds.), Handbook of writing research (pp. 395–409). Guilford Press.

Shin, J., & Gierl, M. J. (2020). More efficient processes for creating automated essayscoring frameworks: A demonstration of two algorithms. Language Testing, 38 (2), 247–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532220937830 .

Stevenson, M., & Phakiti, A. (2014). The effects of computer-generated feedback on the quality of writing. Assessing Writing, 19 , 51–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2013.11.007

Stevenson, M. (2016). A critical interpretative synthesis: The integration ofAutomated Writing Evaluation into classroom writing instruction. Computers and Composition, 42, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2016.05.001 .

Stevenson, M., & Phakiti, A. (2019). Automated feedback and second language writing. In K. Hyland & F. Hyland (Eds.), Feedback in second language writing: Contexts and issues (pp. 125–142). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108635547.009

Toulmin, S. E. (2003). The uses of argument (Updated). Cambridge University Press.

Book Google Scholar

*Tsai, M. H. (2012). The consistency between human raters and an automated essay scoring system in Grading High School Students' English writing. Action in Teacher Education , 34(4), 328-335. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2012.717033

Vojak, C., Kline, S., Cope, B., McCarthey, S., & Kalantzis, M. (2011). New spaces and old places: An analysis of writing assessment software. Computers and Composition, 28 (2), 97–111.

*Vajjala, S. (2018). Automated assessment of non-native learner essays: Investigating the role of linguistic features [Article]. International Journal of Artificial Intelligence in Education, 28(1), 79-105. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40593-017-0142-3

Ware, P. (2011). Computer-generated feedback on student writing. TESOL Quarterly, 45 (4), 769–774. https://doi.org/10.5054/tq.2011.272525

Warschauer, M., & Ware, P. (2006). Automated writing evaluation: Defining the classroom research agenda. Language Teaching Research, 10 (2), 157–180. https://doi.org/10.1191/1362168806lr190oa

Weigle, S. C. (2013a). English as a second language writing and automated essay evaluation. In M. D. Shermis & J. Burstein (Eds.), Handbook of automated essay evaluation: Current applications and new directions (pp. 36–54). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

Weigle, S. C. (2013b). English language learners and automated scoring of essays: Critical considerations. Assessing Writing, 18 (1), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2012.10.006

*Wilson, J. (2017). Associated effects of automated essay evaluation software on growth in writing quality for students with and without disabilities. Reading and Writing , 30(4), 691-718. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-016-9695-z

Williamson, D., Xi, X., & Breyer, F. (2012). A Framework for evaluation and use of automated scoring. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 31 (1), 2–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.2011.00223.x

Xi, X. (2010). Automated scoring and feedback systems: Where are we and where are we heading? Language Testing, 27 (3), 291–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532210364643

Zheng, Y., & Yu, S. (2019). What has been assessed in writing and how? Empirical evidence from Assessing Writing (2000–2018). Assessing Writing, 42 , 100421. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asw.2019.100421

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

National Institute of Education, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, Singapore

Shi Huawei & Vahid Aryadoust

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Vahid Aryadoust .

Ethics declarations

Human and animal rights and informed consent.

The study does NOT include any human participants and/or animals. According to the Research Ethics Committee of Nanyang Technological University, where there are no human or animal subjects in the study, no ethical approval is required. As a result, no informed consent was necessary in the study.

Conflict of interest

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Supplementary file1 (DOCX 46 KB)

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Huawei, S., Aryadoust, V. A systematic review of automated writing evaluation systems. Educ Inf Technol 28 , 771–795 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11200-7

Download citation

Received : 13 February 2022

Accepted : 28 June 2022

Published : 07 July 2022

Issue Date : January 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-022-11200-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Automated writing evaluation; argument-based validation; automated essay scoring

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Writing Systems Research: A new journal for a developing field

2009, Writing Systems Research

Related Papers

Int J Amer Linguist

Terry Joyce

Revised AWLL11 programme + abstracts

Language in Society

Edward J Vajda

Rebecca Treiman

An understanding of the nature of writing is an important foundation for studies of how people read and how they learn to read. This chapter discusses the characteristics of modern writing systems with a view toward providing that foundation. We consider both the appearance of writing systems and how they function. All writing represents the words of a language according to a set of rules. However, important properties of a language often go unrepresented in writing. Change and variation in the spoken language result in complex links to speech. Redundancies in language and writing mean that readers can often get by without taking in all of the visual information. These redundancies also mean that readers must often supplement the visual information that they do take in with knowledge about the language and about the world.

David Roberts , Terry Joyce

Jyotsna Vaid

Dimitrios Meletis

According to Weingarten (2011), writing systems are defined as ordered pairs of languagesL and scriptsS, e.g. English WS(EnglishL, LatinS), where graphematic rules relate linguistic units (phonemes, morphemes, etc.) to units of scripts. An orthography, on the other hand, is an external standardization of the possibilities of such a system that (often arbitrarily) selects normatively correct spellings, rendering e.g. <fox> correct and <*foks> incorrect. Starting with Neef (2015), a multimodular model of writing systems has been proposed that includes language systems and graphematics as necessary modules, with orthography as an optional module. Aspects related to the material substance, embodied by scripts, are mostly neglected. Building on these advances in grapholinguistics, the present contribution attempts to further the theoretical understanding of writing systems by achieving two things: (1) It modifies Neef’s alphabetocentric model to account for all types of writing systems. The result is a new model that underlines the universal mechanisms that are the basis for all written language. In this context, not only the modules of script and graphematics are generalized, but the universality of the central units ‘graph’ and ‘grapheme’ and their parallelism with other linguistic units (mainly ‘phone’ and ‘phoneme’, cf. Lockwood 2001) must also be addressed. (2) This process of generalization leads to the second aim of the talk: to critically reflect on general models such as the proposed when considering the rich diversity of writing systems (for the same question concerning languages, see Evans and Levinson 2009). Questions that arise are: What is the point of the high level of abstraction needed for such models – and what can they explain? Do the benefits they offer outweigh the shortcomings? In addition to the grapheme, the module of orthography will serve as an example to illustrate the tensions between universality and diversity. How can orthography be defined in such diverse systems as Chinese, German, Thai, Arabic, etc.? If there is a common denominator, what is it? Is it of theoretical value? To close the talk, the focus will shift from the linguistics of writing systems to the psychological and cognitive aspects: When considering for example models of reading, are universal models (cf. Frost 2012) helpful or do they distort the reality of processing diverse systems? Is there cognitive unity in written diversity? Evans, Nicholas, and Levison, Stephen C. 2009. “The myth of language universals: Language diversity and its importance for cognitive science.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 32:429-492. Frost, Ram. 2012. “Towards a universal model of reading.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 35:263-329. Lockwood, David G. 2001. “Phoneme and grapheme – How parallel can they be?” LACUS Forum 27:307-316. Neef, Martin. 2015. “Writing systems as modular objects: proposals for theory design in grapholinguistics.” Open Linguistics 1:708-721. Weingarten, Rüdiger. 2011. “Comparative graphematics.” Written Language & Literacy 14:12-38.

Language in Society, vol. 26 no. 3 pp 436-39

J. Marshall Unger

Co-authored with John DeFrancis

Writing is an utterly multifaceted subject. This is echoed by the interdisciplinarity of grapholinguistics, a young field of study invested in all questions pertaining to writing. As one of the modalities of language, writing is undeniably a linguistic subject. However, the most dominant paradigms of linguistics initially neglected questions of writing; thus, the systematic study of those questions had a delayed start and is, to this day, not as well-established as other linguistic subfields. Against this background, it is astonishing how fine-grained grapholinguistic, and especially gra¬phe¬matic, research has become. It must be noted, however, that this research is influenced largely by structuralism and thus focuses on the (static) description of writing as a system, neglecting questions of its use in the process. By contrast, use comes to the forefront in psycholinguistic and sociolinguistic approaches to writing. Phenomena studied by psycholinguistics include processes of reading and writing, literacy acquisition, and disorders of reading and written expression, while the sociolinguistic study of writing has focused, among other things, on the social functions of writing (and its various registers), practices of literacy, and, crucially, ideologies associated with writing. In practice, systematic, psycholinguistic, and sociolinguistic aspects interact and together shape both how writing is structured and how it is used (and how these two factors, in turn, affect each other). To reflect reality in grapholinguistic theory, the systematic, psycholinguistic, and sociolinguistic perspectives should converge. Notably, exchange between these perspectives and the scholars who adopt them has been scarce. Arguably, for the sake of writing as a subject, such exchange is necessary and will likely uncover many (new) questions that have yet to be negotiated. This workshop seeks to make this exchange possible. In featuring talks from international experts covering all three mentioned perspectives, a full(er) picture of the study of writing is expected to emerge. Scholars are invited to present their research in their field of expertise, focusing also on what it can contribute to an overall theory of writing and indicating possible important interfaces with the other perspectives. This will hopefully generate stimulating discussion(s) about the current state and, most importantly, the future of grapholinguistics and a theory of writing.

Zeitschrift für Sprachwissenschaft

In essence, typologies of writing systems seek to classify the world’s diverse writing systems in principled ways. However, against backdrops of early, misguided assumptions (Gelb 1969 [1952]) and stubborn term confusions, most proposals have focused primarily on the dominant levels of representational mapping (i. e., morphemic, syllabic, or phonemic), despite their shortcomings as idealizations (Joyce 2016, forthcoming; Joyce and Borgwaldt 2011; Meletis 2018). In advocating for exploring a more diverse range of criteria, either as alternatives or complementary factors, this paper outlines a promising framework for organizing typology criteria (Meletis 2018; 2020), which consists of three broad categories; namely, (a) linguistic fit, (b) processing fit and (c) sociocultural fit. Linguistic fit concerns the match between a language and its writing system and, thus, relates closely to the traditional criterion of representational mapping. Processing fit pertains to the physiological a...

Loading Preview

Sorry, preview is currently unavailable. You can download the paper by clicking the button above.

RELATED PAPERS

Bene Bassetti , Jyotsna Vaid

Francisco Miguel Valada

COMPTES RENDUS / BOOK REVIEWS

Kevin Tuite

Dimitrios Meletis , Terry Joyce

Dimitrios Meletis , Christa Dürscheid

Journal of Near Eastern Studies

Alexandre Tokovinine

Bene Bassetti

Writing Development in Struggling Learners

Liliana Tolchinsky

Jan Blommaert

Eleanor Dickey

Reading and Writing

Victoria Molfese

Nina Gasviani

Piers Kelly

International Journal of Linguistics

Edoardo Scarpanti

Proceedings of the NAACL HLT 2010 Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Writing: Writing Processes and Authoring Aids}

Steven L Thorne

Gordon Whittaker

Elaine R Silliman

Barbara Turchetta

Written Language & Literacy

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Writing Systems Research

Subject Area and Category

- Linguistics and Language

Taylor and Francis Ltd.

Publication type

17586801, 1758681X

Information

The set of journals have been ranked according to their SJR and divided into four equal groups, four quartiles. Q1 (green) comprises the quarter of the journals with the highest values, Q2 (yellow) the second highest values, Q3 (orange) the third highest values and Q4 (red) the lowest values.

| Category | Year | Quartile |

|---|---|---|

| Linguistics and Language | 2010 | Q4 |

| Linguistics and Language | 2011 | Q2 |

| Linguistics and Language | 2012 | Q2 |

| Linguistics and Language | 2013 | Q2 |

| Linguistics and Language | 2014 | Q1 |

| Linguistics and Language | 2015 | Q2 |

| Linguistics and Language | 2016 | Q1 |

| Linguistics and Language | 2017 | Q1 |

| Linguistics and Language | 2018 | Q1 |

| Linguistics and Language | 2019 | Q2 |

| Linguistics and Language | 2020 | Q2 |

| Linguistics and Language | 2021 | Q1 |

| Linguistics and Language | 2022 | Q2 |

| Linguistics and Language | 2023 | Q2 |

The SJR is a size-independent prestige indicator that ranks journals by their 'average prestige per article'. It is based on the idea that 'all citations are not created equal'. SJR is a measure of scientific influence of journals that accounts for both the number of citations received by a journal and the importance or prestige of the journals where such citations come from It measures the scientific influence of the average article in a journal, it expresses how central to the global scientific discussion an average article of the journal is.

| Year | SJR |

|---|---|

| 2010 | 0.105 |

| 2011 | 0.418 |

| 2012 | 0.400 |

| 2013 | 0.248 |

| 2014 | 0.601 |

| 2015 | 0.214 |

| 2016 | 0.420 |

| 2017 | 0.573 |

| 2018 | 0.628 |

| 2019 | 0.206 |

| 2020 | 0.277 |

| 2021 | 0.379 |

| 2022 | 0.168 |

| 2023 | 0.192 |

Evolution of the number of published documents. All types of documents are considered, including citable and non citable documents.

| Year | Documents |

|---|---|

| 2009 | 5 |

| 2010 | 5 |

| 2011 | 12 |

| 2012 | 16 |

| 2013 | 12 |

| 2014 | 15 |

| 2015 | 16 |

| 2016 | 13 |

| 2017 | 9 |

| 2018 | 8 |

| 2019 | 3 |

| 2020 | 2 |

| 2021 | 0 |

| 2022 | 0 |

| 2023 | 0 |

This indicator counts the number of citations received by documents from a journal and divides them by the total number of documents published in that journal. The chart shows the evolution of the average number of times documents published in a journal in the past two, three and four years have been cited in the current year. The two years line is equivalent to journal impact factor ™ (Thomson Reuters) metric.

| Cites per document | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2009 | 0.000 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2010 | 0.200 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2011 | 1.400 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2012 | 1.091 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2013 | 0.789 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2014 | 1.444 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2015 | 0.782 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2016 | 0.661 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2017 | 1.286 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2018 | 1.075 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2019 | 0.783 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2020 | 0.788 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2021 | 1.364 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2022 | 1.462 |

| Cites / Doc. (4 years) | 2023 | 1.800 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2009 | 0.000 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2010 | 0.200 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2011 | 1.400 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2012 | 1.091 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2013 | 0.576 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2014 | 1.050 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2015 | 0.674 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2016 | 0.698 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2017 | 1.136 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2018 | 1.026 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2019 | 0.700 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2020 | 0.550 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2021 | 1.308 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2022 | 1.200 |

| Cites / Doc. (3 years) | 2023 | 1.000 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2009 | 0.000 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2010 | 0.200 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2011 | 1.400 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2012 | 0.706 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2013 | 0.500 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2014 | 0.714 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2015 | 0.444 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2016 | 0.613 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2017 | 0.828 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2018 | 1.136 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2019 | 0.588 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2020 | 0.364 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2021 | 1.600 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2022 | 0.000 |

| Cites / Doc. (2 years) | 2023 | 0.000 |

Evolution of the total number of citations and journal's self-citations received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. Journal Self-citation is defined as the number of citation from a journal citing article to articles published by the same journal.

| Cites | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Self Cites | 2009 | 0 |

| Self Cites | 2010 | 0 |

| Self Cites | 2011 | 1 |

| Self Cites | 2012 | 2 |

| Self Cites | 2013 | 1 |

| Self Cites | 2014 | 8 |

| Self Cites | 2015 | 2 |

| Self Cites | 2016 | 7 |

| Self Cites | 2017 | 8 |

| Self Cites | 2018 | 4 |

| Self Cites | 2019 | 2 |

| Self Cites | 2020 | 0 |

| Self Cites | 2021 | 0 |

| Self Cites | 2022 | 0 |

| Self Cites | 2023 | 0 |

| Total Cites | 2009 | 0 |

| Total Cites | 2010 | 1 |

| Total Cites | 2011 | 14 |

| Total Cites | 2012 | 24 |

| Total Cites | 2013 | 19 |

| Total Cites | 2014 | 42 |

| Total Cites | 2015 | 29 |

| Total Cites | 2016 | 30 |

| Total Cites | 2017 | 50 |

| Total Cites | 2018 | 39 |

| Total Cites | 2019 | 21 |

| Total Cites | 2020 | 11 |

| Total Cites | 2021 | 17 |

| Total Cites | 2022 | 6 |

| Total Cites | 2023 | 2 |

Evolution of the number of total citation per document and external citation per document (i.e. journal self-citations removed) received by a journal's published documents during the three previous years. External citations are calculated by subtracting the number of self-citations from the total number of citations received by the journal’s documents.

| Cites | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| External Cites per document | 2009 | 0 |

| External Cites per document | 2010 | 0.200 |

| External Cites per document | 2011 | 1.300 |

| External Cites per document | 2012 | 1.000 |

| External Cites per document | 2013 | 0.545 |

| External Cites per document | 2014 | 0.850 |

| External Cites per document | 2015 | 0.628 |

| External Cites per document | 2016 | 0.535 |

| External Cites per document | 2017 | 0.955 |

| External Cites per document | 2018 | 0.921 |

| External Cites per document | 2019 | 0.633 |

| External Cites per document | 2020 | 0.550 |

| External Cites per document | 2021 | 1.308 |

| External Cites per document | 2022 | 1.200 |

| External Cites per document | 2023 | 1.000 |

| Cites per document | 2009 | 0.000 |

| Cites per document | 2010 | 0.200 |

| Cites per document | 2011 | 1.400 |

| Cites per document | 2012 | 1.091 |

| Cites per document | 2013 | 0.576 |

| Cites per document | 2014 | 1.050 |

| Cites per document | 2015 | 0.674 |

| Cites per document | 2016 | 0.698 |

| Cites per document | 2017 | 1.136 |

| Cites per document | 2018 | 1.026 |

| Cites per document | 2019 | 0.700 |

| Cites per document | 2020 | 0.550 |

| Cites per document | 2021 | 1.308 |

| Cites per document | 2022 | 1.200 |

| Cites per document | 2023 | 1.000 |

International Collaboration accounts for the articles that have been produced by researchers from several countries. The chart shows the ratio of a journal's documents signed by researchers from more than one country; that is including more than one country address.

| Year | International Collaboration |

|---|---|

| 2009 | 20.00 |

| 2010 | 20.00 |

| 2011 | 25.00 |

| 2012 | 31.25 |

| 2013 | 8.33 |

| 2014 | 26.67 |

| 2015 | 18.75 |

| 2016 | 23.08 |

| 2017 | 11.11 |

| 2018 | 25.00 |

| 2019 | 33.33 |

| 2020 | 0.00 |

| 2021 | 0 |

| 2022 | 0 |

| 2023 | 0 |

Not every article in a journal is considered primary research and therefore "citable", this chart shows the ratio of a journal's articles including substantial research (research articles, conference papers and reviews) in three year windows vs. those documents other than research articles, reviews and conference papers.

| Documents | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Non-citable documents | 2009 | 0 |

| Non-citable documents | 2010 | 1 |

| Non-citable documents | 2011 | 1 |

| Non-citable documents | 2012 | 1 |

| Non-citable documents | 2013 | 1 |

| Non-citable documents | 2014 | 1 |

| Non-citable documents | 2015 | 1 |

| Non-citable documents | 2016 | 0 |

| Non-citable documents | 2017 | 0 |

| Non-citable documents | 2018 | 0 |

| Non-citable documents | 2019 | 0 |

| Non-citable documents | 2020 | 0 |

| Non-citable documents | 2021 | 0 |

| Non-citable documents | 2022 | 0 |

| Non-citable documents | 2023 | 0 |

| Citable documents | 2009 | 0 |

| Citable documents | 2010 | 4 |

| Citable documents | 2011 | 9 |

| Citable documents | 2012 | 21 |

| Citable documents | 2013 | 32 |

| Citable documents | 2014 | 39 |

| Citable documents | 2015 | 42 |

| Citable documents | 2016 | 43 |

| Citable documents | 2017 | 44 |

| Citable documents | 2018 | 38 |

| Citable documents | 2019 | 30 |

| Citable documents | 2020 | 20 |

| Citable documents | 2021 | 13 |

| Citable documents | 2022 | 5 |

| Citable documents | 2023 | 2 |

Ratio of a journal's items, grouped in three years windows, that have been cited at least once vs. those not cited during the following year.

| Documents | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Uncited documents | 2009 | 0 |

| Uncited documents | 2010 | 4 |

| Uncited documents | 2011 | 3 |

| Uncited documents | 2012 | 10 |

| Uncited documents | 2013 | 23 |

| Uncited documents | 2014 | 23 |

| Uncited documents | 2015 | 28 |

| Uncited documents | 2016 | 24 |

| Uncited documents | 2017 | 21 |

| Uncited documents | 2018 | 20 |

| Uncited documents | 2019 | 19 |

| Uncited documents | 2020 | 11 |

| Uncited documents | 2021 | 5 |

| Uncited documents | 2022 | 3 |

| Uncited documents | 2023 | 0 |

| Cited documents | 2009 | 0 |

| Cited documents | 2010 | 1 |

| Cited documents | 2011 | 7 |

| Cited documents | 2012 | 12 |

| Cited documents | 2013 | 10 |

| Cited documents | 2014 | 17 |

| Cited documents | 2015 | 15 |

| Cited documents | 2016 | 19 |

| Cited documents | 2017 | 23 |

| Cited documents | 2018 | 18 |

| Cited documents | 2019 | 11 |

| Cited documents | 2020 | 9 |

| Cited documents | 2021 | 8 |

| Cited documents | 2022 | 2 |

| Cited documents | 2023 | 2 |

Evolution of the percentage of female authors.

| Year | Female Percent |

|---|---|

| 2009 | 0.00 |

| 2010 | 57.14 |

| 2011 | 51.85 |

| 2012 | 55.17 |

| 2013 | 70.59 |

| 2014 | 55.17 |

| 2015 | 76.47 |

| 2016 | 57.69 |

| 2017 | 58.33 |

| 2018 | 60.71 |

| 2019 | 77.78 |

| 2020 | 100.00 |

| 2021 | 0.00 |

| 2022 | 0.00 |

| 2023 | 0.00 |

Evolution of the number of documents cited by public policy documents according to Overton database.

| Documents | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Overton | 2009 | 0 |

| Overton | 2010 | 2 |

| Overton | 2011 | 2 |

| Overton | 2012 | 0 |

| Overton | 2013 | 0 |

| Overton | 2014 | 2 |

| Overton | 2015 | 3 |

| Overton | 2016 | 0 |

| Overton | 2017 | 0 |

| Overton | 2018 | 1 |

| Overton | 2019 | 0 |

| Overton | 2020 | 0 |

| Overton | 2021 | 0 |

| Overton | 2022 | 0 |

| Overton | 2023 | 0 |

Evoution of the number of documents related to Sustainable Development Goals defined by United Nations. Available from 2018 onwards.

| Documents | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| SDG | 2018 | 1 |

| SDG | 2019 | 1 |

| SDG | 2020 | 0 |

| SDG | 2021 | 0 |

| SDG | 2022 | 0 |

| SDG | 2023 | 0 |

Leave a comment

Name * Required

Email (will not be published) * Required

* Required Cancel

The users of Scimago Journal & Country Rank have the possibility to dialogue through comments linked to a specific journal. The purpose is to have a forum in which general doubts about the processes of publication in the journal, experiences and other issues derived from the publication of papers are resolved. For topics on particular articles, maintain the dialogue through the usual channels with your editor.

Follow us on @ScimagoJR Scimago Lab , Copyright 2007-2024. Data Source: Scopus®

Cookie settings

Cookie Policy

Legal Notice

Privacy Policy

- Library of Congress

- Research Guides

Mangyan Bamboo Collection from Mindoro, Philippines, circa 1900-1939, at the Library of Congress

Background information on the mangyan.

- Introduction

- Transcriptions, Transliterations, and Translations

- List of Bamboo Items in the Collection

- Accompanying Documents and Publications

- Using the Library of Congress

Asian Studies : Ask a Librarian

Have a question? Need assistance? Use our online form to ask a librarian for help.

The term “Mangyan” is an umbrella term that refers to several indigenous communities on the island of Mindoro in the Philippines. There are eight recognized groups: Iraya, Alangan, Tadyawan, Tawbuid, Bangon, Buhid, Hanunuo, and Ratagnon. While these groups are often referred to as “Mangyan,” they speak different languages, and only one of the ethnic groups—Hanunuo—refers to itself as Mangyan. “Hanunuo” is an exonym for both the ethnic group and the language, and is often tagged onto “Mangyan” to form “Hanunuo Mangyan.” “Hanunuo” means “truly, real,” or “genuine.” Hanunuo Mangyans tend to drop the descriptor “hanunuo” within their communities, and refer to themselves and their language as “Mangyan.”

Of the eight groups of Mangyan listed above, only the Hanunuo and the Buhid from the southern part of Mindoro Island have attested writing systems. Both writing systems, called “Surat Hanunuo Mangyan” and “Surat Buhid Mangyan” respectively are thought to be of Indic origin, and perhaps introduced into Mangyan culture from what is now Indonesia around the 12th or 13th centuries. The Hanunuo Mangyan and Southern Buhid have similar syllabic scripts due to their geographical proximity. The Northern Buhid, on the other hand, have their own syllabary. These syllabaries, that date back to pre-Spanish times (before the early 1500s), are one of the few pre-Spanish writing systems that survived Spanish rule, and enabled the Mangyan peoples to preserve a rich literary tradition.

One of the most widely loved Mangyan literary forms is the song poem. There are three distinct classes of song-poems: ambahan , urukay , and adahiyo . The ambahan is a poem with 7 syllables per line with the last syllable of each line rhyming with the others. Ambahan are composed anonymously and still immensely popular. They cover a wide range of subjects such as birds, plants, and natural phenomena. The composers use the symbolism of these subjects to express their desires, deal with embarrassing situations, and in courting, among other things. Ambahan are often recited during large gatherings and there is no musical accompaniment. Those who participate in ambahan sessions often go back and forth in exchanges that highlight the improvisational skills of the poet. In addition to public settings, ambahan are also recited in more private surroundings for pleasure. The Library’s Mangyan bamboo collection contains 22 ambahan (Set 1).

Another poetic form is the urukay . Urukay consist of lines of eight syllables and have uniform end-rhymes. The word urukay probably comes from the neighboring island of Panay where it means “merrymaking.” The language of the Mangyan urukay is old Hiligaynon-Bisaya and is no longer understood by most Mangyan singers today. Urukay was probably acquired by the Mangyans from early contacts with Bisayans. Usually, urukay is less popular with younger audiences and confined to the older generation of Mangyan. They are sung to the accompaniment of a guitar.

The adahiyo is the third kind of poem in the Mangyan literary tradition. The term comes from the Spanish adagio or “adage.” The adahiyo usually has six syllables to a line but without a fixed final syllable rhyming scheme. This literary form is not widely performed among the Mangyan and might have been acquired through contacts with Tagalogs who settled in Mindoro. The adahiyo is recited without the accompaniment of music, and contains many adapted Spanish words and Catholic religious terms.

As is evident, the Mangyan have a rich literary tradition with a long history. Despite its deep roots, most of the extant historical examples of Mangyan writing are no more than a century old. This is because Mangyan writing was carved on bamboo, a material that deteriorates quickly in the local, tropical climate. The Library of Congress’s Mangyan bamboo collection—which dates to between ca. 1904-1939, thus preserves a link between the current living tradition of Mangyan writing and literature and its past.

While the Mangyan script is still not widely known, its preservation has received a boost in the last few decades. In 1997, the Mangyan script was declared as a National Cultural Treasure by the government of the Philippines and the following year, it was inscribed in the Memory of the World Registers of UNESCO (United Nations Scientific and Cultural Organization).

The work of Antoon Postma—a Dutch scholar who originally went to Mindoro as a Society of the Divine Word or SVD missionary in 1958 and lived among the Mangyan for more than half a century—inspired the establishment of the Mangyan Heritage Center, a non-profit organization based in Calapan City. The Mangyan Heritage Center continues to promote and keep alive the cultural heritage of the indigenous peoples of Mindoro through digital collections, recordings, and publications on the Mangyan as well as through programs to revive Mangyan syllabic scripts and ambahan .

At the Library of Congress, in addition to the Mangyan bamboo collection, users can also listen to recordings of ambahan donated by the Mangyan Heritage Center onsite.

Rare Materials Notice

Further reading.

The following titles link to either fuller bibliographic information in the Library of Congress Online Catalog or to the Library of Congress E-Resources Online Catalog. Links to additional online content are included when available.

Conklin, Harold. Hanunóo-English vocabulary . Berkeley: University of California Press, 1953.

Delgado Fansler, Lolita, Quintin V. Pastrana, Raena E. Abella, and Emily Catapang, eds. Bamboo whispers : poetry of the Mangyan . Makati City, Philippines: Bookmark, Inc., Calapan City, Oriental Mindoro, Philippines: Mangyan Heritage Center, Inc., 2017.

Gardner, Fletcher. “Three Contemporary Incised Bamboo Manuscripts from Hampangan Mangyan, Mindoro, P. I.,” Journal of the American Oriental Society , Dec., 1939, Vol. 59, No. 4, pp. 496-502.

Gardner, Fletcher and Ildefonso Maliwanag. Indic writings of the Mindoro-Palawan axis , 3 vols., San Antonio, Texas: Witte Memorial Museum, 1939-1940.

Postma, Antoon. Annotated Mangyan bibliography (1570-1988) : with index . Panaytayan, Mansalay, Oriental Mindoro, Philippines: Mangyan Assistance and Research Center, 1988.

Postma, Antoon. "Mangyan folklore," Philippine Quarterly of Culture and Society , March-June 1977, Vol. 5, No. 1/2, Philippine Cultural Minorities II, pp. 38-53.

Postma, Antoon. Treasure of a minority : the ambahan, a poetic expression of the Mangyans of Southern Mindoro, Philippines . Manila: Arnoldus Press, 1981.

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Provenance >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 11:51 AM

- URL: https://guides.loc.gov/mangyan-bamboo-collection

The Development of Blended Learning Model Combined With Project-Based Learning Model in Indonesian Students’ Scientific Writing

- Santi Oktarina Sriwijaya University

This research aims to describe the practicality of the blended learning model combined with the project-based learning model when Indonesian students write scientific papers. This research employs the research and development method but focuses only on the small group testing stage. The subjects of this research are students taking scientific writing courses in the study program of Indonesian Language and Literature Education, Indonesia. The data were collected through tests, a questionnaire, and an interview and analyzed by means of qualitative and quantitative techniques. The research results show that in general, this learning model is practical to be used in learning scientific writing. Furthermore, the post-test results show significantly higher scores than those of the pre-test results in students' scientific writing (34.59). Additionally, based on the results of the questionnaire distributed to students, all components of the blended learning model combined with the project-based learning model that have been developed, namely the learning structure, reaction principles, social systems, and support systems are considered by students to be appropriate and very appropriate. However, the results of the interview reveal that there are weaknesses in the learning model being developed. These weaknesses will be addressed so that its effectiveness is well tested in the next stage, namely the large group test.

Author Biography

Santi oktarina, sriwijaya university.

Indonesian Language and Literature Education Study Program

Adedoyin, O. B., & Soykan, E. (2020). Covid-19 pandemic and online learning: the challenges and opportunities. Interactive Learning Environments, 0(0), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2020.1813180

Akhadiah, S. (2015). Bahasa sebagai sarana komunikasi ilmiah [Languages as a means of scientific communication]. Paedea.

Alebaikan, R., & Troudi, S. (2010). Blended learning in Saudi universities: Challenges and perspectives. ALT-J: Research in Learning Technology, 18(1), 49–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687761003657614

Alipour, P. (2020). A comparative study of online vs. blended learning on vocabulary development among intermediate EFL learners. Cogent Education, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2020.1857489

AlRouji, O. (2020). The effectiveness of blended learning in enhancing Saudi students’ competence in paragraph writing. English Language Teaching, 13(9), 72. https://doi.org/10.5539/elt.v13n9p72

Alston, C. L., Monte-Sano, C., Schleppegrell, M., & Harn, K. (2021). Teaching models of disciplinary argumentation in middle school social studies: A framework for supporting writing development. Journal of Writing Research, 13(2), 285–321. https://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2021.13.02.04

Aminah, M. (2021). English learning using blended learning and missing pieces activities methods. Jurnal Scientia, 10(1), 150–157. Retrieved February 12, 2024, from http://infor.seaninstitute.org/index.php/pendidikan/article/view/274

Arfandi, A., & Samsudin, M. A. (2021). Peran guru profesional sebagai fasilitator dan komunikator dalam kegiatan belajar mengajar [The role of professional teachers as facilitators and communicators in teaching and learning activities]. Edupedia : Jurnal Studi Pendidikan Dan Pedagogi Islam, 5(2), 37–45. https://doi.org/10.35316/edupedia.v5i2.1200

Argawati, N. O., & Suryani, L. (2020). Project-based learning in teaching writing: the implementation and students opinion. English Review: Journal of English Education, 8(2), 55. Retrieved February 2, 2024, from https://doi.org/10.25134/erjee.v8i2.2120

Arrends, R. (1997). Classroom instructional management. The McGraw-Hill Company.

Arta, G. J., Ratminingsih, N. M., & Hery Santosa, M. (2019). The effectiveness of blended learning strategy on students’ writing competency of the tenth grade students. JPI (Jurnal Pendidikan Indonesia), 8(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.23887/jpi-undiksha.v8i1.13501

Balqis, K., Purnomo, M. E., & Oktarina, S. (2021). Learning media for writing fantasy story text based on scientific plus using adobe flash. Jurnal Ilmiah Sekolah Dasar, 5(3), 387. https://doi.org/10.23887/jisd.v5i3.35635

Belda-Medina, J. (2021). ICTs and project-based learning (pbl) in EFL: Pre-service teachers’ attitudes and digital skills. International Journal of Applied Linguistics and English Literature, 10(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.ijalel.v.10n.1p.63

Burhanuddin. (2021). Efektivitas penerapan model pembelajaran blended learning terhadap kemampuan menulis artikel ilmiah [The effectiveness of the blended learning model implementation on the ability to write scientific articles]. EKSPOSE: Jurnal Penelitian Hukum Dan Pendidikan, 20(2), 1280–1287.

Chen, P. S. D., Lambert, A. D., & Guidry, K. R. (2010). Engaging online learners: The impact of Web-based learning technology on college student engagement. Computers and Education, 54(4), 1222–1232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2009.11.008

Cilliers, E. J. (2017). The challenge of teaching generation Z.. International Journal of Social Sciences, 3(1), 188–198. https://doi.org/10.20319/pijss.2017.31.188198

Dakhi, O., Jama, J., Irfan, D., Ambiyar, & Ishak. (2020). Blended learning: a 21St century learning model at college. International Journal of Multiscience, 1(7), 50–65.

Darmuki, A., Hariyadi, A., & Hidayati, N. A. (2021). Peningkatan kemampuan menulis karya ilmiah menggunakan media video faststone di masa pandemi covid-19 [Increasing scientific paper writing ability using faststone video media during the covid-19 pandemic]. Jurnal Educatio FKIP UNMA, 7(2), 389–397. https://doi.org/10.31949/educatio.v7i2.1027

Dhawan, S. (2020). Online Learning: A Panacea in the Time of COVID-19 Crisis. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239520934018

Eryilmaza, A., & Yesilyurt, Y. E. (2022). How to Measure and Increase Second Language Writing Motivation. LEARN Journal: Language Education and Acquisition Research Network, 15(2), 922–945.

Evans, J. C., Yip, H., Chan, K., Armatas, C., & Tse, A. (2020). Blended learning in higher education: professional development in a Hong Kong university. Higher Education Research and Development, 39(4), 643–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1685943

Firmadani, F. (2020). Media pembelajaran berbasis teknologi sebagai inovasi pembelajaran era revolusi industri 4.0 [Technology-based learning media as a learning innovation in the fourth industrial revolution era]. Prosiding Konferensi Pendidikan Nasional, 2(1), 93–97. Retrieved January 1, 2024, from http://ejurnal.mercubuana-yogya.ac.id/index.php/Prosiding_KoPeN/article/view/1084/660

Gall, Meedith D, Gall, Joice P. & Borg, W. E. (2007). Educational research (Introduction). Pearson Education, Inc.

Guillén-Gámez, F. D., Lugones, A., Mayorga-Fernández, M. J., & Wang, S. (2019). ICT use by pre-service foreign language teachers according to gender, age, and motivation. Cogent Education, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2019.1574693

Hidayati, D., Novianti, H., Khansa, M., Slamet, J., & Suryati, N. (2023). Effectiveness project-based learning in ESP class: viewed from Indonesian students’ learning outcomes. International Journal of Information and Education Technology, 13(3), 558–565. https://doi.org/10.18178/ijiet.2023.13.3.1839

Hosseinpour, N., Biria, R., & Rezvani, E. (2019). Promoting academic writing proficiency of Iranian EFL learners through blended learning. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 20(4), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.17718/TOJDE.640525

Jeanjaroonsri, R. (2023). Thai EFL learners’ use and perceptions of mobile technologies for writing. LEARN Journal: Language Education and Acquisition Research Network, 16(1), 169–193.

Joyce, B, Weil, M & Calhoun, E. (2009). Model of teaching. Pearson Education, Inc.

Maros, M., Korenkova, M., Fila, M., Levicky, M., & Schoberova, M. (2021). Project-based learning and its effectiveness: evidence from Slovakia. Interactive Learning Environments, 0(0), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2021.1954036

Miller, E. C., Reigh, E., Berland, L., & Krajcik, J. (2021). Supporting equity in virtual science instruction through project-based learning: opportunities and challenges in the era of covid-19. Journal of Science Teacher Education, 32(6), 642–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/1046560X.2021.1873549

Mohammad, R. (2018). The use of technology in English language learning. International Journal of Research in English Education (IJREE), 3(2), 115–125. Retrieved January 10, 2024, from http://ijreeonline.com/

Oktarina, santi, Emzir, dan Z. R. (2017). Analysis of learning model requirements writing academic based on-learning moodle. International Journal of Language Education and Cultural Review, 3(2), 94--105. https://doi.org/htpp//doi.org/10.21009/IJLECR.032.08

Oktarina, S. (2021). Students’ responses towards e-learning schoology content on creative writing learning during the covid-19 pandemic. English Review: Journal of English Education, 10(1), 195–198. Retrieved January 18, 2024, from https://journal.uniku.ac.id/index.php/ERJEE

Oktarina, S. (2023). Mobile learning based-creative writing in senior high. Jurnal Pedagogi & Pembelajaran. 6(2), 299–307.

Oktarina, S., Emzir, E., & Rafli, Z. (2018). Students and lecturers perception on academic writing instruction. English Review: Journal of English Education, 6(2), 69. https://doi.org/10.25134/erjee.v6i2.1256

Oktarina, S., Indrawati, S., & Slamet, A. (2022). Students’ and lecturers’ perceptions toward interactive multimedia in teaching academic writing. Al-Ishlah: Jurnal Pendidikan. 6(2), 377–384.

Oktarina, S., Indrawati, S., & Slamet, A. (2023). Needs analysis for blended learning models and project-based learning to increase student creativity and productivity in writing scientific papers. Al-Ishlah: Jurnal Pendidikan, 15(2020), 4537–4545. https://doi.org/10.35445/alishlah.v15i4.3187

Oshima, A. dan A. H. (2007). Introduction to academic writing. Pearson Education, Inc.

Piamsai, C. (2020). The effect of scaffolding on non-proficient EFL learners’ performance in an academic writing class. LEARN Journal: Language Education and Acquisition Research Network, 13(2), 288–305.

Rama, R., Sumarni, S., & Oktarina, S. (2023). Analisis kebutuhan pengembangan video interaktif berpadukan metode blended learning materi menulis cerpen sekolah dasar [A need analysis for developing interactive videos combined with blended learning method for elementary school students to learn short story writing material]. Jurnal Pendidikan Dasar Perkhasa, 9(2), 585–593.

Sakran. (2021). Meningkatkan nilai tugas proyek bahasa Indonesia melalui kegiatan project based learning [Increasing the value of Indonesian language project assignments through project based learning activities]. Jurnal Edukasi Saintifik, 1(1), 51–59.

Sari, R. T., & Angreni, S. (2018). Penerapan model pembelajaran project based learning (PjBL: Upaya Peningkatan kreativitas mahasiswa [The implementation of the project-based learning (PjBL) learning model to increase students' creativity]. Jurnal VARIDIKA, 30(1), 79–83. https://doi.org/10.23917/varidika.v30i1.6548

So, L., & Lee, C. H. (2013). A case study on the effects of an L2 writing instructional model for blended learning in higher education. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 12(4), 1–10.

Soleh, D. (2021). Penggunaan model pembelajaran project based learning melalui google classroom dalam pembelajaran menulis teks prosedur [Using the project-based learning model via google classroom in the learning of procedure text writing]. Ideguru: Jurnal Karya Ilmiah Guru, 6(2), 137–143. https://doi.org/10.51169/ideguru.v6i2.239

Turmudi, D. (2020). Utilizing a web-based technology in blended EFL academic writing classes for university students. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 1517(1). https://doi.org/10.1088/1742-6596/1517/1/012063

Yuliansyah, A., & Mutiara Ayu. (2021). The Implementation of project-based assignment in online learning during COVID-19. Journal of English Language Teaching and Learning (JELTL), 2(1), 32–38. Retrieved January 25, 2024, from http://jim.teknokrat.ac.id/index.php/english-language-teaching/index

Zhang, M., & Chen, S. (2022). Modeling dichotomous technology use among university EFL teachers in China: The roles of TPACK, affective and evaluative attitudes towards technology. Cogent Education, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2021.2013396

Copyright © 2015-2024 ACADEMY PUBLICATION — All Rights Reserved

How to cite ChatGPT

Use discount code STYLEBLOG15 for 15% off APA Style print products with free shipping in the United States.

We, the APA Style team, are not robots. We can all pass a CAPTCHA test , and we know our roles in a Turing test . And, like so many nonrobot human beings this year, we’ve spent a fair amount of time reading, learning, and thinking about issues related to large language models, artificial intelligence (AI), AI-generated text, and specifically ChatGPT . We’ve also been gathering opinions and feedback about the use and citation of ChatGPT. Thank you to everyone who has contributed and shared ideas, opinions, research, and feedback.

In this post, I discuss situations where students and researchers use ChatGPT to create text and to facilitate their research, not to write the full text of their paper or manuscript. We know instructors have differing opinions about how or even whether students should use ChatGPT, and we’ll be continuing to collect feedback about instructor and student questions. As always, defer to instructor guidelines when writing student papers. For more about guidelines and policies about student and author use of ChatGPT, see the last section of this post.

Quoting or reproducing the text created by ChatGPT in your paper

If you’ve used ChatGPT or other AI tools in your research, describe how you used the tool in your Method section or in a comparable section of your paper. For literature reviews or other types of essays or response or reaction papers, you might describe how you used the tool in your introduction. In your text, provide the prompt you used and then any portion of the relevant text that was generated in response.

Unfortunately, the results of a ChatGPT “chat” are not retrievable by other readers, and although nonretrievable data or quotations in APA Style papers are usually cited as personal communications , with ChatGPT-generated text there is no person communicating. Quoting ChatGPT’s text from a chat session is therefore more like sharing an algorithm’s output; thus, credit the author of the algorithm with a reference list entry and the corresponding in-text citation.

When prompted with “Is the left brain right brain divide real or a metaphor?” the ChatGPT-generated text indicated that although the two brain hemispheres are somewhat specialized, “the notation that people can be characterized as ‘left-brained’ or ‘right-brained’ is considered to be an oversimplification and a popular myth” (OpenAI, 2023).

OpenAI. (2023). ChatGPT (Mar 14 version) [Large language model]. https://chat.openai.com/chat

You may also put the full text of long responses from ChatGPT in an appendix of your paper or in online supplemental materials, so readers have access to the exact text that was generated. It is particularly important to document the exact text created because ChatGPT will generate a unique response in each chat session, even if given the same prompt. If you create appendices or supplemental materials, remember that each should be called out at least once in the body of your APA Style paper.

When given a follow-up prompt of “What is a more accurate representation?” the ChatGPT-generated text indicated that “different brain regions work together to support various cognitive processes” and “the functional specialization of different regions can change in response to experience and environmental factors” (OpenAI, 2023; see Appendix A for the full transcript).

Creating a reference to ChatGPT or other AI models and software

The in-text citations and references above are adapted from the reference template for software in Section 10.10 of the Publication Manual (American Psychological Association, 2020, Chapter 10). Although here we focus on ChatGPT, because these guidelines are based on the software template, they can be adapted to note the use of other large language models (e.g., Bard), algorithms, and similar software.

The reference and in-text citations for ChatGPT are formatted as follows:

- Parenthetical citation: (OpenAI, 2023)

- Narrative citation: OpenAI (2023)

Let’s break that reference down and look at the four elements (author, date, title, and source):

Author: The author of the model is OpenAI.

Date: The date is the year of the version you used. Following the template in Section 10.10, you need to include only the year, not the exact date. The version number provides the specific date information a reader might need.

Title: The name of the model is “ChatGPT,” so that serves as the title and is italicized in your reference, as shown in the template. Although OpenAI labels unique iterations (i.e., ChatGPT-3, ChatGPT-4), they are using “ChatGPT” as the general name of the model, with updates identified with version numbers.

The version number is included after the title in parentheses. The format for the version number in ChatGPT references includes the date because that is how OpenAI is labeling the versions. Different large language models or software might use different version numbering; use the version number in the format the author or publisher provides, which may be a numbering system (e.g., Version 2.0) or other methods.

Bracketed text is used in references for additional descriptions when they are needed to help a reader understand what’s being cited. References for a number of common sources, such as journal articles and books, do not include bracketed descriptions, but things outside of the typical peer-reviewed system often do. In the case of a reference for ChatGPT, provide the descriptor “Large language model” in square brackets. OpenAI describes ChatGPT-4 as a “large multimodal model,” so that description may be provided instead if you are using ChatGPT-4. Later versions and software or models from other companies may need different descriptions, based on how the publishers describe the model. The goal of the bracketed text is to briefly describe the kind of model to your reader.

Source: When the publisher name and the author name are the same, do not repeat the publisher name in the source element of the reference, and move directly to the URL. This is the case for ChatGPT. The URL for ChatGPT is https://chat.openai.com/chat . For other models or products for which you may create a reference, use the URL that links as directly as possible to the source (i.e., the page where you can access the model, not the publisher’s homepage).

Other questions about citing ChatGPT

You may have noticed the confidence with which ChatGPT described the ideas of brain lateralization and how the brain operates, without citing any sources. I asked for a list of sources to support those claims and ChatGPT provided five references—four of which I was able to find online. The fifth does not seem to be a real article; the digital object identifier given for that reference belongs to a different article, and I was not able to find any article with the authors, date, title, and source details that ChatGPT provided. Authors using ChatGPT or similar AI tools for research should consider making this scrutiny of the primary sources a standard process. If the sources are real, accurate, and relevant, it may be better to read those original sources to learn from that research and paraphrase or quote from those articles, as applicable, than to use the model’s interpretation of them.

We’ve also received a number of other questions about ChatGPT. Should students be allowed to use it? What guidelines should instructors create for students using AI? Does using AI-generated text constitute plagiarism? Should authors who use ChatGPT credit ChatGPT or OpenAI in their byline? What are the copyright implications ?

On these questions, researchers, editors, instructors, and others are actively debating and creating parameters and guidelines. Many of you have sent us feedback, and we encourage you to continue to do so in the comments below. We will also study the policies and procedures being established by instructors, publishers, and academic institutions, with a goal of creating guidelines that reflect the many real-world applications of AI-generated text.

For questions about manuscript byline credit, plagiarism, and related ChatGPT and AI topics, the APA Style team is seeking the recommendations of APA Journals editors. APA Style guidelines based on those recommendations will be posted on this blog and on the APA Style site later this year.

Update: APA Journals has published policies on the use of generative AI in scholarly materials .

We, the APA Style team humans, appreciate your patience as we navigate these unique challenges and new ways of thinking about how authors, researchers, and students learn, write, and work with new technologies.

American Psychological Association. (2020). Publication manual of the American Psychological Association (7th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1037/0000165-000

Related and recent

Comments are disabled due to your privacy settings. To re-enable, please adjust your cookie preferences.

APA Style Monthly

Subscribe to the APA Style Monthly newsletter to get tips, updates, and resources delivered directly to your inbox.

Welcome! Thank you for subscribing.

APA Style Guidelines

Browse APA Style writing guidelines by category

- Abbreviations

- Bias-Free Language

- Capitalization

- In-Text Citations

- Italics and Quotation Marks

- Paper Format

- Punctuation

- Research and Publication

- Spelling and Hyphenation

- Tables and Figures

Full index of topics

COVID-19 vaccines: Get the facts

Looking to get the facts about COVID-19 vaccines? Here's what you need to know about the different vaccines and the benefits of getting vaccinated.

As the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) continues to cause illness, you might have questions about COVID-19 vaccines. Find out about the different types of COVID-19 vaccines, how they work, the possible side effects, and the benefits for you and your family.

COVID-19 vaccine benefits

What are the benefits of getting a covid-19 vaccine.

Staying up to date with a COVID-19 vaccine can:

- Help prevent serious illness and death due to COVID-19 for both children and adults.

- Help prevent you from needing to go to the hospital due to COVID-19 .

- Be a less risky way to protect yourself compared to getting sick with the virus that causes COVID-19.

- Lower long-term risk for cardiovascular complications after COVID-19.

Factors that can affect how well you're protected after a vaccine can include your age, if you've had COVID-19 before or if you have medical conditions such as cancer.

How well a COVID-19 vaccine protects you also depends on timing, such as when you got the shot. And your level of protection depends on how the virus that causes COVID-19 changes and what variants the vaccine protects against.

Talk to your healthcare team about how you can stay up to date with COVID-19 vaccines.

Should I get the COVID-19 vaccine even if I've already had COVID-19?

Yes. Catching the virus that causes COVID-19 or getting a COVID-19 vaccination gives you protection, also called immunity, from the virus. But over time, that protection seems to fade. The COVID-19 vaccine can boost your body's protection.

Also, the virus that causes COVID-19 can change, also called mutate. Vaccination with the most up-to-date variant that is spreading or expected to spread helps keep you from getting sick again.

Researchers continue to study what happens when someone has COVID-19 a second time. Later infections are generally milder than the first infection. But severe illness can still happen. Serious illness is more likely among people older than age 65, people with more than four medical conditions and people with weakened immune systems.

Safety and side effects of COVID-19 vaccines

What covid-19 vaccines have been authorized or approved.

The COVID-19 vaccines available in the United States are:

- 2023-2024 Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine, available for people age 6 months and older.

- 2023-2024 Moderna COVID-19 vaccine, available for people age 6 months and older.

- 2023-2024 Novavax COVID-19 vaccine, available for people age 12 years and older.

These vaccines have U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) emergency use authorization or approval.

In December 2020, the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine two-dose series was found to be both safe and effective in preventing COVID-19 infection in people age 18 and older. This data helped predict how well the vaccines would work for younger people. The effectiveness varied by age.

The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine is approved under the name Comirnaty for people age 12 and older. The FDA authorized the vaccine for people age 6 months to 11 years. The number of shots in this vaccination series varies based on a person's age and COVID-19 vaccination history.