Our websites may use cookies to personalize and enhance your experience. By continuing without changing your cookie settings, you agree to this collection. For more information, please see our University Websites Privacy Notice .

Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning

- Case Based Learning

What is the case method?

In case-based learning, students learn to interact with and manipulate basic foundational knowledge by working with situations resembling specific real-world scenarios.

How does it work?

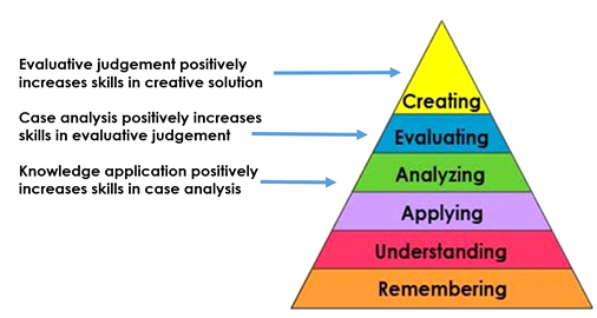

Case studies encourage students to use critical thinking skills to identify and narrow an issue, develop and evaluate alternatives, and offer a solution. In fact, Nkhoma (2016), who studied the value of developing case-based learning activities based on Bloom’s Taxonomy of thinking skills, suggests that this approach encourages deep learning through critical thinking:

Sherfield (2004) confirms this, asserting that working through case studies can begin to build and expand these six critical thinking strategies:

- Emotional restraint

- Questioning

- Distinguishing fact from fiction

- Searching for ambiguity

What makes a good case?

Case-based learning can focus on anything from a one-sentence physics word problem to a textbook-sized nursing case or a semester-long case in a law course. Though we often assume that a case is a “problem,” Ellet (2007) suggests that most cases entail one of four types of situations:

- Evaluations

- What are the facts you know about the case?

- What are some logical assumptions you can make about the case?

- What are the problems involved in the case as you see it?

- What is the root problem (the main issue)?

- What do you estimate is the cause of the root problem?

- What are the reasons that the root problem exists?

- What is the solution to the problem?

- Are there any moral or ethical considerations to your solution?

- What are the real-world implications for this case?

- How might the lives of the people in the case study be changed because of your proposed solution?

- Where in your world (campus/town/country) might a problem like this occur?

- Where could someone get help with this problem?

- What personal advice would you give to the person or people concerned?

Adapted from Sherfield’s Case Studies for the First Year (2004)

Some faculty buy prepared cases from publishers, but many create their own based on their unique course needs. When introducing case-based learning to students, be sure to offer a series of guidelines or questions to prompt deep thinking. One option is to provide a scenario followed by questions; for example, questions designed for a first year experience problem might include these:

Before you begin, take a look at what others are doing with cases in your field. Pre-made case studies are available from various publishers, and you can find case-study templates online.

- Choose scenarios carefully

- Tell a story from beginning to end, including many details

- Create real-life characters and use quotes when possible

- Write clearly and concisely and format the writing simply

- Ask students to reflect on their learning—perhaps identifying connections between the lesson and specific course learning outcomes—after working a case

Additional Resources

- Barnes, Louis B. et al. Teaching and the Case Method , 3 rd (1994). Harvard, 1994.

- Campoy, Renee. Case Study Analysis in the Classroom: Becoming a Reflective Teacher . Sage Publications, 2005.

- Ellet, William. The Case Study Handbook . Harvard, 2007.

- Herreid, Clyde Freeman, ed. Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . NSTA, 2007.

- Herreid, Clyde Freeman, et al. Science Stories: Using Case Studies to Teach Critical Thinking . NSTA, 2012.

- Nkhoma, M., Lam, et al. Developing case-based learning activities based on the revised Bloom’s Taxonomy . Proceedings of Informing Science & IT Education Conference (In SITE) 2016, 85-93. 2016.

- Rolls, Geoff. Classic Case Studies in Psychology , 3 rd Hodder Education, Bookpoint, 2014.

- Sherfield, Robert M., et al. Case Studies for the First Year . Pearson, 2004.

- Shulman, Judith H., ed. Case Methods in Teacher Education . Teacher’s College, 1992.

Quick Links

- Developing Learning Objectives

- Creating Your Syllabus

- Active Learning

- Service Learning

- Critical Thinking and other Higher-Order Thinking Skills

- Group and Team Based Learning

- Integrating Technology in the Classroom

- Effective PowerPoint Design

- Hybrid and Hybrid Limited Course Design

- Online Course Design

Consult with our CETL Professionals

Consultation services are available to all UConn faculty at all campuses at no charge.

Centre for Teaching and Learning

- Instructors

- Instructional Strategies

Case-Based Learning

What is case-based learning.

Using a case-based approach engages students in discussion of specific scenarios that resemble or typically are real-world examples. This method is learner-centered with intense interaction between participants as they build their knowledge and work together as a group to examine the case. The instructor's role is that of a facilitator while the students collaboratively analyze and address problems and resolve questions that have no single right answer.

Clyde Freeman Herreid provides eleven basic rules for case-based learning.

- Tells a story.

- Focuses on an interest-arousing issue.

- Set in the past five years

- Creates empathy with the central characters.

- Includes quotations. There is no better way to understand a situation and to gain empathy for the characters

- Relevant to the reader.

- Must have pedagogic utility.

- Conflict provoking.

- Decision forcing.

- Has generality.

Why Use Case-Based Learning?

To provide students with a relevant opportunity to see theory in practice. Real world or authentic contexts expose students to viewpoints from multiple sources and see why people may want different outcomes. Students can also see how a decision will impact different participants, both positively and negatively.

To require students to analyze data in order to reach a conclusion. Since many assignments are open-ended, students can practice choosing appropriate analytic techniques as well. Instructors who use case-based learning say that their students are more engaged, interested, and involved in the class.

To develop analytic, communicative and collaborative skills along with content knowledge. In their effort to find solutions and reach decisions through discussion, students sort out factual data, apply analytic tools, articulate issues, reflect on their relevant experiences, and draw conclusions they can relate to new situations. In the process, they acquire substantive knowledge and develop analytic, collaborative, and communication skills.

Many faculty also use case studies in their curriculum to teach content, connect students with real life data, or provide opportunities for students to put themselves in the decision maker's shoes.

Teaching Strategies for Case-Based Learning

By bringing real world problems into student learning, cases invite active participation and innovative solutions to problems as they work together to reach a judgment, decision, recommendation, prediction or other concrete outcome.

The Campus Instructional Consulting unit at Indiana University has created a great resource for case-based learning. The following is from their website which we have permission to use.

Formats for Cases

- “Finished” cases based on facts: for analysis only, since the solution is indicated or alternate solutions are suggested.

- “Unfinished” open-ended cases: the results are not yet clear (either because the case has not come to a factual conclusion in real life, or because the instructor has eliminated the final facts.) Students must predict, make choices and offer suggestions that will affect the outcome.

- Fictional cases: entirely written by the instructor—can be open-ended or finished. Cautionary note: the case must be both complex enough to mimic reality, yet not have so many “red herrings” as to obscure the goal of the exercise.

- Original documents: news articles, reports with data and statistics, summaries, excerpts from historical writings, artifacts, literary passages, video and audio recordings, ethnographies, etc. With the right questions, these can become problem-solving opportunities. Comparison between two original documents related to the same topic or theme is a strong strategy for encouraging both analysis and synthesis. This gives the opportunity for presenting more than one side of an argument, making the conflicts more complex.

Managing a Case Assignment

- Design discussions for small groups. 3-6 students are an ideal group size for setting up a discussion on a case.

- Design the narrative or situation such that it requires participants to reach a judgment, decision, recommendation, prediction or other concrete outcome. If possible, require each group to reach a consensus on the decision requested.

- Structure the discussion. The instructor should provide a series of written questions to guide small group discussion. Pay careful attention to the sequencing of the questions. Early questions might ask participants to make observations about the facts of the case. Later questions could ask for comparisons, contrasts, and analyses of competing observations or hypotheses. Final questions might ask students to take a position on the matter. The purpose of these questions is to stimulate, guide or prod (but not dictate) participants’ observations and analyses. The questions should be impossible to answer with a simple yes or no.

- Debrief the discussion to compare group responses. Help the whole class interprets and understand the implications of their solutions.

- Allow groups to work without instructor interference. The instructor must be comfortable with ambiguity and with adopting the non-traditional roles of witness and resource, rather than authority.

Designing Case Study Questions

Cases can be more or less “directed” by the kinds of questions asked. These kinds of questions can be appended to any case, or could be a handout for participants unfamiliar with case studies on how to approach one.

- What is the situation—what do you actually know about it from reading the case? (Distinguishes between fact and assumptions under critical understanding)

- What issues are at stake? (Opportunity for linking to theoretical readings)

- What questions do you have—what information do you still need? Where/how could you find it?

- What problem(s) need to be solved? (Opportunity to discuss communication versus conflict, gaps between assumptions, sides of the argument)

- What are all the possible options? What are the pros/cons of each option?

- What are the underlying assumptions for [person X] in the case—where do you see them?

- What criteria should you use when choosing an option? What does that mean about your assumptions?

Managing Discussion and Debate Effectively

- Delay the problem-solving part until the rest of the discussion has had time to develop. Start with expository questions to clarify the facts, then move to analysis, and finally to evaluation, judgment, and recommendations.

- Shift points of view: “Now that we’ve seen it from [W’s] standpoint, what’s happening here from [Y’s] standpoint?” What evidence would support Y’s position? What are the dynamics between the two positions?

- Shift levels of abstraction: if the answer to the question above is “It’s just a bad situation for her,” quotations help: When [Y] says “_____,” what are her assumptions? Or seek more concrete explanations: Why does she hold this point of view?”

- Ask for benefits/disadvantages of a position; for all sides.

- Shift time frame— not just to “What’s next?” but also to “How could this situation have been different?” What could have been done earlier to head off this conflict and turn it into a productive conversation? Is it too late to fix this? What are possible leverage points for a more productive discussion? What good can come of the existing situation?

- Shift to another context: We see how a person who thinks X would see the situation. How would a person who thinks Y see it? We see what happened in the Johannesburg news, how could this be handled in [your town/province]? How might [insert person, organization] address this problem?

- Follow-up questions: “What do you mean by ___?” Or, “Could you clarify what you said about ___?” (even if it was a pretty clear statement—this gives students time for thinking, developing different views, and exploration in more depth). Or “How would you square that observation with what [name of person] pointed out?”

- Point out and acknowledge differences in discussion— “that’s an interesting difference from what Sam just said, Sarah. Let’s look at where the differences lie.” (let sides clarify their points before moving on).

Herreid, C. F. (2007). Start with a story: The case study method of teaching college science. NSTA Press.

- Online Articles

- Websites and Case Studies

Select Books available through the Queen's Library

Crosling, G. & Webb, G. (2002). Supporting Student Learning: Case Studies, Experience and Practice from Higher Education. London: Kogan Page

Edwards, H., Smith, B., & Webb, G. (Eds.) (2001). Lecturing: Case Studies, Experience and Practice. London: Kogan Page.

Ellington, H. & Earl, S. (1998). Using Games, Simulations and Interactive Case Studies. Birmingham: Staff and Educational Development Association

Wassermann, S. (1994). Introduction to Case Method Teaching: A Guide to the Galaxy. New York: Teachers College Press, Columbia University.

Bieron, J. & Dinan, F. (1999). Case Studies Across a Science Curriculum. Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry, Canisius College in Buffalo, NY.

Walters. M. R. (1999). Case-stimulated learning within endocrine physiology lectures: An approach applicable to other disciplines. Advances in Physiology Education, 276, 74-78.

Websites and Online Case Collections

The Center for Teaching Excellence at the University of Medicine and Dentistry in New Jersey offers a wide variety of references including 21 links to case repositories in the Health Sciences.

The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science provides an award-winning library of over 410 cases and case materials while promoting the development and dissemination of innovative materials and sound educational practices for case teaching in the sciences.

Houghton and Mifflin provide an excellent resource for students including on analyzing and writing the case.

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Related Articles

The Learning Zone Model

Learning Styles

Cognitive Load Theory

The Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition

Understanding Learning Styles

Article • 10 min read

Case Study-Based Learning

Enhancing learning through immediate application.

Written by the Mind Tools Content Team

If you've ever tried to learn a new concept, you probably appreciate that "knowing" is different from "doing." When you have an opportunity to apply your knowledge, the lesson typically becomes much more real.

Adults often learn differently from children, and we have different motivations for learning. Typically, we learn new skills because we want to. We recognize the need to learn and grow, and we usually need – or want – to apply our newfound knowledge soon after we've learned it.

A popular theory of adult learning is andragogy (the art and science of leading man, or adults), as opposed to the better-known pedagogy (the art and science of leading children). Malcolm Knowles , a professor of adult education, was considered the father of andragogy, which is based on four key observations of adult learners:

- Adults learn best if they know why they're learning something.

- Adults often learn best through experience.

- Adults tend to view learning as an opportunity to solve problems.

- Adults learn best when the topic is relevant to them and immediately applicable.

This means that you'll get the best results with adults when they're fully involved in the learning experience. Give an adult an opportunity to practice and work with a new skill, and you have a solid foundation for high-quality learning that the person will likely retain over time.

So, how can you best use these adult learning principles in your training and development efforts? Case studies provide an excellent way of practicing and applying new concepts. As such, they're very useful tools in adult learning, and it's important to understand how to get the maximum value from them.

What Is a Case Study?

Case studies are a form of problem-based learning, where you present a situation that needs a resolution. A typical business case study is a detailed account, or story, of what happened in a particular company, industry, or project over a set period of time.

The learner is given details about the situation, often in a historical context. The key players are introduced. Objectives and challenges are outlined. This is followed by specific examples and data, which the learner then uses to analyze the situation, determine what happened, and make recommendations.

The depth of a case depends on the lesson being taught. A case study can be two pages, 20 pages, or more. A good case study makes the reader think critically about the information presented, and then develop a thorough assessment of the situation, leading to a well-thought-out solution or recommendation.

Why Use a Case Study?

Case studies are a great way to improve a learning experience, because they get the learner involved, and encourage immediate use of newly acquired skills.

They differ from lectures or assigned readings because they require participation and deliberate application of a broad range of skills. For example, if you study financial analysis through straightforward learning methods, you may have to calculate and understand a long list of financial ratios (don't worry if you don't know what these are). Likewise, you may be given a set of financial statements to complete a ratio analysis. But until you put the exercise into context, you may not really know why you're doing the analysis.

With a case study, however, you might explore whether a bank should provide financing to a borrower, or whether a company is about to make a good acquisition. Suddenly, the act of calculating ratios becomes secondary – it's more important to understand what the ratios tell you. This is how case studies can make the difference between knowing what to do, and knowing how, when, and why to do it.

Then, what really separates case studies from other practical forms of learning – like scenarios and simulations – is the ability to compare the learner's recommendations with what actually happened. When you know what really happened, it's much easier to evaluate the "correctness" of the answers given.

When to Use a Case Study

As you can see, case studies are powerful and effective training tools. They also work best with practical, applied training, so make sure you use them appropriately.

Remember these tips:

- Case studies tend to focus on why and how to apply a skill or concept, not on remembering facts and details. Use case studies when understanding the concept is more important than memorizing correct responses.

- Case studies are great team-building opportunities. When a team gets together to solve a case, they'll have to work through different opinions, methods, and perspectives.

- Use case studies to build problem-solving skills, particularly those that are valuable when applied, but are likely to be used infrequently. This helps people get practice with these skills that they might not otherwise get.

- Case studies can be used to evaluate past problem solving. People can be asked what they'd do in that situation, and think about what could have been done differently.

Ensuring Maximum Value From Case Studies

The first thing to remember is that you already need to have enough theoretical knowledge to handle the questions and challenges in the case study. Otherwise, it can be like trying to solve a puzzle with some of the pieces missing.

Here are some additional tips for how to approach a case study. Depending on the exact nature of the case, some tips will be more relevant than others.

- Read the case at least three times before you start any analysis. Case studies usually have lots of details, and it's easy to miss something in your first, or even second, reading.

- Once you're thoroughly familiar with the case, note the facts. Identify which are relevant to the tasks you've been assigned. In a good case study, there are often many more facts than you need for your analysis.

- If the case contains large amounts of data, analyze this data for relevant trends. For example, have sales dropped steadily, or was there an unexpected high or low point?

- If the case involves a description of a company's history, find the key events, and consider how they may have impacted the current situation.

- Consider using techniques like SWOT analysis and Porter's Five Forces Analysis to understand the organization's strategic position.

- Stay with the facts when you draw conclusions. These include facts given in the case as well as established facts about the environmental context. Don't rely on personal opinions when you put together your answers.

Writing a Case Study

You may have to write a case study yourself. These are complex documents that take a while to research and compile. The quality of the case study influences the quality of the analysis. Here are some tips if you want to write your own:

- Write your case study as a structured story. The goal is to capture an interesting situation or challenge and then bring it to life with words and information. You want the reader to feel a part of what's happening.

- Present information so that a "right" answer isn't obvious. The goal is to develop the learner's ability to analyze and assess, not necessarily to make the same decision as the people in the actual case.

- Do background research to fully understand what happened and why. You may need to talk to key stakeholders to get their perspectives as well.

- Determine the key challenge. What needs to be resolved? The case study should focus on one main question or issue.

- Define the context. Talk about significant events leading up to the situation. What organizational factors are important for understanding the problem and assessing what should be done? Include cultural factors where possible.

- Identify key decision makers and stakeholders. Describe their roles and perspectives, as well as their motivations and interests.

- Make sure that you provide the right data to allow people to reach appropriate conclusions.

- Make sure that you have permission to use any information you include.

A typical case study structure includes these elements:

- Executive summary. Define the objective, and state the key challenge.

- Opening paragraph. Capture the reader's interest.

- Scope. Describe the background, context, approach, and issues involved.

- Presentation of facts. Develop an objective picture of what's happening.

- Description of key issues. Present viewpoints, decisions, and interests of key parties.

Because case studies have proved to be such effective teaching tools, many are already written. Some excellent sources of free cases are The Times 100 , CasePlace.org , and Schroeder & Schroeder Inc . You can often search for cases by topic or industry. These cases are expertly prepared, based mostly on real situations, and used extensively in business schools to teach management concepts.

Case studies are a great way to improve learning and training. They provide learners with an opportunity to solve a problem by applying what they know.

There are no unpleasant consequences for getting it "wrong," and cases give learners a much better understanding of what they really know and what they need to practice.

Case studies can be used in many ways, as team-building tools, and for skill development. You can write your own case study, but a large number are already prepared. Given the enormous benefits of practical learning applications like this, case studies are definitely something to consider adding to your next training session.

Knowles, M. (1973). 'The Adult Learner: A Neglected Species [online].' Available here .

This premium resource is exclusive to Mind Tools Members.

To continue, you will need to either login or join Mind Tools.

Our members enjoy unparalleled access to thousands of training resources, covering a wide range of topics, all designed to help you develop your management and leadership skills

Already a member? Login now

Expense your annual subscription

Joining Mind Tools benefits you AND your organization - so why not ask your manager to expense your annual subscription? With 20% off until end October, it's a win-win!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Key Management Skills

Most Popular

Latest Updates

The Psychological Contract

How Good Is Your Problem Solving?

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Mindtools member newsletter october 17, 2024.

Time for the Great Re-engagement?

Mindtools Member Newsletter October 24, 2024

Recognizing Team Needs

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Meeting your team's unspoken expectations

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

Member Newsletter

Introducing the Management Skills Framework

Transparent Communication

Social Sensitivity

Self-Awareness and Self-Regulation

Team Goal Setting

Recognition

Inclusivity

Active Listening

- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Resources and Guides

Case Method Teaching and Learning

What is the case method? How can the case method be used to engage learners? What are some strategies for getting started? This guide helps instructors answer these questions by providing an overview of the case method while highlighting learner-centered and digitally-enhanced approaches to teaching with the case method. The guide also offers tips to instructors as they get started with the case method and additional references and resources.

On this page:

What is case method teaching.

- Case Method at Columbia

Why use the Case Method?

Case method teaching approaches, how do i get started.

- Additional Resources

The CTL is here to help!

For support with implementing a case method approach in your course, email [email protected] to schedule your 1-1 consultation .

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2019). Case Method Teaching and Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved from [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/case-method/

Case method 1 teaching is an active form of instruction that focuses on a case and involves students learning by doing 2 3 . Cases are real or invented stories 4 that include “an educational message” or recount events, problems, dilemmas, theoretical or conceptual issue that requires analysis and/or decision-making.

Case-based teaching simulates real world situations and asks students to actively grapple with complex problems 5 6 This method of instruction is used across disciplines to promote learning, and is common in law, business, medicine, among other fields. See Table 1 below for a few types of cases and the learning they promote.

Table 1: Types of cases and the learning they promote.

For a more complete list, see Case Types & Teaching Methods: A Classification Scheme from the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science.

Back to Top

Case Method Teaching and Learning at Columbia

The case method is actively used in classrooms across Columbia, at the Morningside campus in the School of International and Public Affairs (SIPA), the School of Business, Arts and Sciences, among others, and at Columbia University Irving Medical campus.

Faculty Spotlight:

Professor Mary Ann Price on Using Case Study Method to Place Pre-Med Students in Real-Life Scenarios

Read more

Professor De Pinho on Using the Case Method in the Mailman Core

Case method teaching has been found to improve student learning, to increase students’ perception of learning gains, and to meet learning objectives 8 9 . Faculty have noted the instructional benefits of cases including greater student engagement in their learning 10 , deeper student understanding of concepts, stronger critical thinking skills, and an ability to make connections across content areas and view an issue from multiple perspectives 11 .

Through case-based learning, students are the ones asking questions about the case, doing the problem-solving, interacting with and learning from their peers, “unpacking” the case, analyzing the case, and summarizing the case. They learn how to work with limited information and ambiguity, think in professional or disciplinary ways, and ask themselves “what would I do if I were in this specific situation?”

The case method bridges theory to practice, and promotes the development of skills including: communication, active listening, critical thinking, decision-making, and metacognitive skills 12 , as students apply course content knowledge, reflect on what they know and their approach to analyzing, and make sense of a case.

Though the case method has historical roots as an instructor-centered approach that uses the Socratic dialogue and cold-calling, it is possible to take a more learner-centered approach in which students take on roles and tasks traditionally left to the instructor.

Cases are often used as “vehicles for classroom discussion” 13 . Students should be encouraged to take ownership of their learning from a case. Discussion-based approaches engage students in thinking and communicating about a case. Instructors can set up a case activity in which students are the ones doing the work of “asking questions, summarizing content, generating hypotheses, proposing theories, or offering critical analyses” 14 .

The role of the instructor is to share a case or ask students to share or create a case to use in class, set expectations, provide instructions, and assign students roles in the discussion. Student roles in a case discussion can include:

- discussion “starters” get the conversation started with a question or posing the questions that their peers came up with;

- facilitators listen actively, validate the contributions of peers, ask follow-up questions, draw connections, refocus the conversation as needed;

- recorders take-notes of the main points of the discussion, record on the board, upload to CourseWorks, or type and project on the screen; and

- discussion “wrappers” lead a summary of the main points of the discussion.

Prior to the case discussion, instructors can model case analysis and the types of questions students should ask, co-create discussion guidelines with students, and ask for students to submit discussion questions. During the discussion, the instructor can keep time, intervene as necessary (however the students should be doing the talking), and pause the discussion for a debrief and to ask students to reflect on what and how they learned from the case activity.

Note: case discussions can be enhanced using technology. Live discussions can occur via video-conferencing (e.g., using Zoom ) or asynchronous discussions can occur using the Discussions tool in CourseWorks (Canvas) .

Table 2 includes a few interactive case method approaches. Regardless of the approach selected, it is important to create a learning environment in which students feel comfortable participating in a case activity and learning from one another. See below for tips on supporting student in how to learn from a case in the “getting started” section and how to create a supportive learning environment in the Guide for Inclusive Teaching at Columbia .

Table 2. Strategies for Engaging Students in Case-Based Learning

Approaches to case teaching should be informed by course learning objectives, and can be adapted for small, large, hybrid, and online classes. Instructional technology can be used in various ways to deliver, facilitate, and assess the case method. For instance, an online module can be created in CourseWorks (Canvas) to structure the delivery of the case, allow students to work at their own pace, engage all learners, even those reluctant to speak up in class, and assess understanding of a case and student learning. Modules can include text, embedded media (e.g., using Panopto or Mediathread ) curated by the instructor, online discussion, and assessments. Students can be asked to read a case and/or watch a short video, respond to quiz questions and receive immediate feedback, post questions to a discussion, and share resources.

For more information about options for incorporating educational technology to your course, please contact your Learning Designer .

To ensure that students are learning from the case approach, ask them to pause and reflect on what and how they learned from the case. Time to reflect builds your students’ metacognition, and when these reflections are collected they provides you with insights about the effectiveness of your approach in promoting student learning.

Well designed case-based learning experiences: 1) motivate student involvement, 2) have students doing the work, 3) help students develop knowledge and skills, and 4) have students learning from each other.

Designing a case-based learning experience should center around the learning objectives for a course. The following points focus on intentional design.

Identify learning objectives, determine scope, and anticipate challenges.

- Why use the case method in your course? How will it promote student learning differently than other approaches?

- What are the learning objectives that need to be met by the case method? What knowledge should students apply and skills should they practice?

- What is the scope of the case? (a brief activity in a single class session to a semester-long case-based course; if new to case method, start small with a single case).

- What challenges do you anticipate (e.g., student preparation and prior experiences with case learning, discomfort with discussion, peer-to-peer learning, managing discussion) and how will you plan for these in your design?

- If you are asking students to use transferable skills for the case method (e.g., teamwork, digital literacy) make them explicit.

Determine how you will know if the learning objectives were met and develop a plan for evaluating the effectiveness of the case method to inform future case teaching.

- What assessments and criteria will you use to evaluate student work or participation in case discussion?

- How will you evaluate the effectiveness of the case method? What feedback will you collect from students?

- How might you leverage technology for assessment purposes? For example, could you quiz students about the case online before class, accept assignment submissions online, use audience response systems (e.g., PollEverywhere) for formative assessment during class?

Select an existing case, create your own, or encourage students to bring course-relevant cases, and prepare for its delivery

- Where will the case method fit into the course learning sequence?

- Is the case at the appropriate level of complexity? Is it inclusive, culturally relevant, and relatable to students?

- What materials and preparation will be needed to present the case to students? (e.g., readings, audiovisual materials, set up a module in CourseWorks).

Plan for the case discussion and an active role for students

- What will your role be in facilitating case-based learning? How will you model case analysis for your students? (e.g., present a short case and demo your approach and the process of case learning) (Davis, 2009).

- What discussion guidelines will you use that include your students’ input?

- How will you encourage students to ask and answer questions, summarize their work, take notes, and debrief the case?

- If students will be working in groups, how will groups form? What size will the groups be? What instructions will they be given? How will you ensure that everyone participates? What will they need to submit? Can technology be leveraged for any of these areas?

- Have you considered students of varied cognitive and physical abilities and how they might participate in the activities/discussions, including those that involve technology?

Student preparation and expectations

- How will you communicate about the case method approach to your students? When will you articulate the purpose of case-based learning and expectations of student engagement? What information about case-based learning and expectations will be included in the syllabus?

- What preparation and/or assignment(s) will students complete in order to learn from the case? (e.g., read the case prior to class, watch a case video prior to class, post to a CourseWorks discussion, submit a brief memo, complete a short writing assignment to check students’ understanding of a case, take on a specific role, prepare to present a critique during in-class discussion).

Andersen, E. and Schiano, B. (2014). Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide . Harvard Business Press.

Bonney, K. M. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains†. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 16 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v16i1.846

Davis, B.G. (2009). Chapter 24: Case Studies. In Tools for Teaching. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Garvin, D.A. (2003). Making the Case: Professional Education for the world of practice. Harvard Magazine. September-October 2003, Volume 106, Number 1, 56-107.

Golich, V.L. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. International Studies Perspectives. 1, 11-29.

Golich, V.L.; Boyer, M; Franko, P.; and Lamy, S. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. Pew Case Studies in International Affairs. Institute for the Study of Diplomacy.

Heath, J. (2015). Teaching & Writing Cases: A Practical Guide. The Case Center, UK.

Herreid, C.F. (2011). Case Study Teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. No. 128, Winder 2011, 31 – 40.

Herreid, C.F. (2007). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . National Science Teachers Association. Available as an ebook through Columbia Libraries.

Herreid, C.F. (2006). “Clicker” Cases: Introducing Case Study Teaching Into Large Classrooms. Journal of College Science Teaching. Oct 2006, 36(2). https://search.proquest.com/docview/200323718?pq-origsite=gscholar

Krain, M. (2016). Putting the Learning in Case Learning? The Effects of Case-Based Approaches on Student Knowledge, Attitudes, and Engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 27(2), 131-153.

Lundberg, K.O. (Ed.). (2011). Our Digital Future: Boardrooms and Newsrooms. Knight Case Studies Initiative.

Popil, I. (2011). Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Education Today, 31(2), 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.06.002

Schiano, B. and Andersen, E. (2017). Teaching with Cases Online . Harvard Business Publishing.

Thistlethwaite, JE; Davies, D.; Ekeocha, S.; Kidd, J.M.; MacDougall, C.; Matthews, P.; Purkis, J.; Clay D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education: A BEME systematic review . Medical Teacher. 2012; 34(6): e421-44.

Yadav, A.; Lundeberg, M.; DeSchryver, M.; Dirkin, K.; Schiller, N.A.; Maier, K. and Herreid, C.F. (2007). Teaching Science with Case Studies: A National Survey of Faculty Perceptions of the Benefits and Challenges of Using Cases. Journal of College Science Teaching; Sept/Oct 2007; 37(1).

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Additional resources

Teaching with Cases , Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

Features “what is a teaching case?” video that defines a teaching case, and provides documents to help students prepare for case learning, Common case teaching challenges and solutions, tips for teaching with cases.

Promoting excellence and innovation in case method teaching: Teaching by the Case Method , Christensen Center for Teaching & Learning. Harvard Business School.

National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science . University of Buffalo.

A collection of peer-reviewed STEM cases to teach scientific concepts and content, promote process skills and critical thinking. The Center welcomes case submissions. Case classification scheme of case types and teaching methods:

- Different types of cases: analysis case, dilemma/decision case, directed case, interrupted case, clicker case, a flipped case, a laboratory case.

- Different types of teaching methods: problem-based learning, discussion, debate, intimate debate, public hearing, trial, jigsaw, role-play.

Columbia Resources

Resources available to support your use of case method: The University hosts a number of case collections including: the Case Consortium (a collection of free cases in the fields of journalism, public policy, public health, and other disciplines that include teaching and learning resources; SIPA’s Picker Case Collection (audiovisual case studies on public sector innovation, filmed around the world and involving SIPA student teams in producing the cases); and Columbia Business School CaseWorks , which develops teaching cases and materials for use in Columbia Business School classrooms.

Center for Teaching and Learning

The Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) offers a variety of programs and services for instructors at Columbia. The CTL can provide customized support as you plan to use the case method approach through implementation. Schedule a one-on-one consultation.

Office of the Provost

The Hybrid Learning Course Redesign grant program from the Office of the Provost provides support for faculty who are developing innovative and technology-enhanced pedagogy and learning strategies in the classroom. In addition to funding, faculty awardees receive support from CTL staff as they redesign, deliver, and evaluate their hybrid courses.

The Start Small! Mini-Grant provides support to faculty who are interested in experimenting with one new pedagogical strategy or tool. Faculty awardees receive funds and CTL support for a one-semester period.

Explore our teaching resources.

- Blended Learning

- Contemplative Pedagogy

- Inclusive Teaching Guide

- FAQ for Teaching Assistants

- Metacognition

CTL resources and technology for you.

- Overview of all CTL Resources and Technology

- The origins of this method can be traced to Harvard University where in 1870 the Law School began using cases to teach students how to think like lawyers using real court decisions. This was followed by the Business School in 1920 (Garvin, 2003). These professional schools recognized that lecture mode of instruction was insufficient to teach critical professional skills, and that active learning would better prepare learners for their professional lives. ↩

- Golich, V.L. (2000). The ABCs of Case Teaching. International Studies Perspectives. 1, 11-29. ↩

- Herreid, C.F. (2007). Start with a Story: The Case Study Method of Teaching College Science . National Science Teachers Association. Available as an ebook through Columbia Libraries. ↩

- Davis, B.G. (2009). Chapter 24: Case Studies. In Tools for Teaching. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass. ↩

- Andersen, E. and Schiano, B. (2014). Teaching with Cases: A Practical Guide . Harvard Business Press. ↩

- Lundberg, K.O. (Ed.). (2011). Our Digital Future: Boardrooms and Newsrooms. Knight Case Studies Initiative. ↩

- Heath, J. (2015). Teaching & Writing Cases: A Practical Guide. The Case Center, UK. ↩

- Bonney, K. M. (2015). Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains†. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education , 16 (1), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v16i1.846 ↩

- Krain, M. (2016). Putting the Learning in Case Learning? The Effects of Case-Based Approaches on Student Knowledge, Attitudes, and Engagement. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching. 27(2), 131-153. ↩

- Thistlethwaite, JE; Davies, D.; Ekeocha, S.; Kidd, J.M.; MacDougall, C.; Matthews, P.; Purkis, J.; Clay D. (2012). The effectiveness of case-based learning in health professional education: A BEME systematic review . Medical Teacher. 2012; 34(6): e421-44. ↩

- Yadav, A.; Lundeberg, M.; DeSchryver, M.; Dirkin, K.; Schiller, N.A.; Maier, K. and Herreid, C.F. (2007). Teaching Science with Case Studies: A National Survey of Faculty Perceptions of the Benefits and Challenges of Using Cases. Journal of College Science Teaching; Sept/Oct 2007; 37(1). ↩

- Popil, I. (2011). Promotion of critical thinking by using case studies as teaching method. Nurse Education Today, 31(2), 204–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2010.06.002 ↩

- Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice. Second Edition. Jossey-Bass. ↩

- Herreid, C.F. (2006). “Clicker” Cases: Introducing Case Study Teaching Into Large Classrooms. Journal of College Science Teaching. Oct 2006, 36(2). https://search.proquest.com/docview/200323718?pq-origsite=gscholar ↩

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

Case-Based Learning

This guide explores what case studies are, the value of using case studies as teaching tools, and how to implement them in your teaching.

What are case studies?

Case studies are stories that are used as a teaching tool to show the application of a theory or concept to real situations. Dependent on the goal they are meant to fulfill, cases can be fact-driven and deductive where there is a correct answer, or they can be context driven where multiple solutions are possible. Various disciplines have employed case studies, including humanities, social sciences, sciences, engineering, law, business, and medicine. Good cases generally have the following features: they tell a good story, are recent, include dialogue, create empathy with the main characters, are relevant to the reader, serve a teaching function, require a dilemma to be solved, and have generality.

How to use cases for teaching and learning

Instructors can create their own cases or can find cases that already exist. The following are some things to keep in mind when creating a case:

- What do you want students to learn from the discussion of the case?

- What do they already know that applies to the case?

- What are the issues that may be raised in discussion?

- How will the case and discussion be introduced?

- What preparation is expected of students? (Do they need to read the case ahead of time? Do research? Write anything?)

- What directions do you need to provide students regarding what they are supposed to do and accomplish?

- Do you need to divide students into groups or will they discuss as the whole class?

- Are you going to use role-playing or facilitators or record keepers? If so, how?

- What are the opening questions?

- How much time is needed for students to discuss the case?

- What concepts are to be applied/extracted during the discussion?

- How will you evaluate students?

To find other cases that already exist, try the following websites (if you know of other examples, please let us know and we will add them to this resource) :

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science , University of Buffalo. SUNY-Buffalo maintains this set of links to other case studies on the web in disciplines ranging from engineering and ethics to sociology and business

- A Journal of Teaching Cases in Public Administration and Public Policy, University of Washington

- The American Anthropological Association’s Handbook on Ethical Issues in Anthropology , Chapter 3: Cases & Solutions provides cases in a format that asks the reader to solve each dilemma and includes the solutions used by the actual anthropologists. Comments by anthropologists who disagreed with the “solution” are also provided.

Additional information

- Teaching with Cases , Harvard Kennedy School

- World Association for Case Method Research and Application

- Case-Based Teaching & Problem-Based Learning , UMich

- What is Case-Based Learning , Queens University

You may also be interested in:

Project-based learning, game-based learning & gamification, experiential learning resources for faculty: introduction, partnerships in experiential learning: faq, designing experiential learning projects, experiential learning for graduate students, student engagement part 2: ensuring deep learning, assessment for experiential learning.

What the Case Study Method Really Teaches

by Nitin Nohria

Summary .

During my decade as dean of Harvard Business School, I spent hundreds of hours talking with our alumni. To enliven these conversations, I relied on a favorite question: “What was the most important thing you learned from your time in our MBA program?”

Partner Center

Making Learning Relevant With Case Studies

The open-ended problems presented in case studies give students work that feels connected to their lives.

Your content has been saved!

To prepare students for jobs that haven’t been created yet, we need to teach them how to be great problem solvers so that they’ll be ready for anything. One way to do this is by teaching content and skills using real-world case studies, a learning model that’s focused on reflection during the problem-solving process. It’s similar to project-based learning, but PBL is more focused on students creating a product.

Case studies have been used for years by businesses, law and medical schools, physicians on rounds, and artists critiquing work. Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work.

You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students:

- How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria?

- How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste? (Or, if you want to be more complex, how can our school reduce its carbon footprint?)

- How can we improve school attendance?

- How can we reduce the number of people who get sick at school during cold and flu season?

Addressing questions like these leads students to identify topics they need to learn more about. In researching the first question, for example, students may see that they need to research food chains and nutrition. Students often ask, reasonably, why they need to learn something, or when they’ll use their knowledge in the future. Learning is most successful for students when the content and skills they’re studying are relevant, and case studies offer one way to create that sense of relevance.

Teaching With Case Studies

Ultimately, a case study is simply an interesting problem with many correct answers. What does case study work look like in classrooms? Teachers generally start by having students read the case or watch a video that summarizes the case. Students then work in small groups or individually to solve the case study. Teachers set milestones defining what students should accomplish to help them manage their time.

During the case study learning process, student assessment of learning should be focused on reflection. Arthur L. Costa and Bena Kallick’s Learning and Leading With Habits of Mind gives several examples of what this reflection can look like in a classroom:

Journaling: At the end of each work period, have students write an entry summarizing what they worked on, what worked well, what didn’t, and why. Sentence starters and clear rubrics or guidelines will help students be successful. At the end of a case study project, as Costa and Kallick write, it’s helpful to have students “select significant learnings, envision how they could apply these learnings to future situations, and commit to an action plan to consciously modify their behaviors.”

Interviews: While working on a case study, students can interview each other about their progress and learning. Teachers can interview students individually or in small groups to assess their learning process and their progress.

Student discussion: Discussions can be unstructured—students can talk about what they worked on that day in a think-pair-share or as a full class—or structured, using Socratic seminars or fishbowl discussions. If your class is tackling a case study in small groups, create a second set of small groups with a representative from each of the case study groups so that the groups can share their learning.

4 Tips for Setting Up a Case Study

1. Identify a problem to investigate: This should be something accessible and relevant to students’ lives. The problem should also be challenging and complex enough to yield multiple solutions with many layers.

2. Give context: Think of this step as a movie preview or book summary. Hook the learners to help them understand just enough about the problem to want to learn more.

3. Have a clear rubric: Giving structure to your definition of quality group work and products will lead to stronger end products. You may be able to have your learners help build these definitions.

4. Provide structures for presenting solutions: The amount of scaffolding you build in depends on your students’ skill level and development. A case study product can be something like several pieces of evidence of students collaborating to solve the case study, and ultimately presenting their solution with a detailed slide deck or an essay—you can scaffold this by providing specified headings for the sections of the essay.

Problem-Based Teaching Resources

There are many high-quality, peer-reviewed resources that are open source and easily accessible online.

- The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science at the University at Buffalo built an online collection of more than 800 cases that cover topics ranging from biochemistry to economics. There are resources for middle and high school students.

- Models of Excellence , a project maintained by EL Education and the Harvard Graduate School of Education, has examples of great problem- and project-based tasks—and corresponding exemplary student work—for grades pre-K to 12.

- The Interdisciplinary Journal of Problem-Based Learning at Purdue University is an open-source journal that publishes examples of problem-based learning in K–12 and post-secondary classrooms.

- The Tech Edvocate has a list of websites and tools related to problem-based learning.

In their book Problems as Possibilities , Linda Torp and Sara Sage write that at the elementary school level, students particularly appreciate how they feel that they are taken seriously when solving case studies. At the middle school level, “researchers stress the importance of relating middle school curriculum to issues of student concern and interest.” And high schoolers, they write, find the case study method “beneficial in preparing them for their future.”

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

Case-based learning (CBL) is an established approach used across disciplines where students apply their knowledge to real-world scenarios, promoting higher levels of cognition (see Bloom’s Taxonomy). In CBL classrooms, students typically work in groups on case studies, stories involving one or more characters and/or scenarios.

In case-based learning, students learn to interact with and manipulate basic foundational knowledge by working with situations resembling specific real-world scenarios. How does it work? Case studies encourage students to use critical thinking skills to identify and narrow an issue, develop and evaluate alternatives, and offer a solution.

Using a case-based approach engages students in discussion of specific scenarios that resemble or typically are real-world examples. This method is learner-centered with intense interaction between participants as they build their knowledge and work together as a group to examine the case.

Case Study-Based Learning. Enhancing Learning Through Immediate Application. MTCT. Written by the Mind Tools Content Team. This premium resource is exclusive to Mind Tools Members. To continue, you will need to either login or join Mind Tools.

Case-based teaching simulates real world situations and asks students to actively grapple with complex problems 5 6 This method of instruction is used across disciplines to promote learning, and is common in law, business, medicine, among other fields. See Table 1 below for a few types of cases and the learning they promote.

Case studies are stories that are used as a teaching tool to show the application of a theory or concept to real situations. Dependent on the goal they are meant to fulfill, cases can be fact-driven and deductive where there is a correct answer, or they can be context driven where multiple solutions are possible.

Summary. It’s been 100 years since Harvard Business School began using the case study method. Beyond teaching specific subject matter, the case study method excels in instilling meta-skills...

Like other forms of problem-based learning, case studies can be accessible for every age group, both in one subject and in interdisciplinary work. You can get started with case studies by tackling relatable questions like these with your students: How can we limit food waste in the cafeteria? How can we get our school to recycle and compost waste?

Case-based learning (CBL) is a strategy for engaging students in real life complex scenarios. Case studies, which are central to case-based learning, have long been used in business, law, and the social sciences, but can be used in any discipline.

In this paper, first, we will present the connection between the pedagogy and teacher education; second, we will introduce the theoretical framework with implications for the instructional model; then, we will present some examples of learning experiences that should be included in a constructivist case-based learning environment with the propos...