Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

Key facts about the abortion debate in America

The U.S. Supreme Court’s June 2022 ruling to overturn Roe v. Wade – the decision that had guaranteed a constitutional right to an abortion for nearly 50 years – has shifted the legal battle over abortion to the states, with some prohibiting the procedure and others moving to safeguard it.

As the nation’s post-Roe chapter begins, here are key facts about Americans’ views on abortion, based on two Pew Research Center polls: one conducted from June 25-July 4 , just after this year’s high court ruling, and one conducted in March , before an earlier leaked draft of the opinion became public.

This analysis primarily draws from two Pew Research Center surveys, one surveying 10,441 U.S. adults conducted March 7-13, 2022, and another surveying 6,174 U.S. adults conducted June 27-July 4, 2022. Here are the questions used for the March survey , along with responses, and the questions used for the survey from June and July , along with responses.

Everyone who took part in these surveys is a member of the Center’s American Trends Panel (ATP), an online survey panel that is recruited through national, random sampling of residential addresses. This way nearly all U.S. adults have a chance of selection. The survey is weighted to be representative of the U.S. adult population by gender, race, ethnicity, partisan affiliation, education and other categories. Read more about the ATP’s methodology .

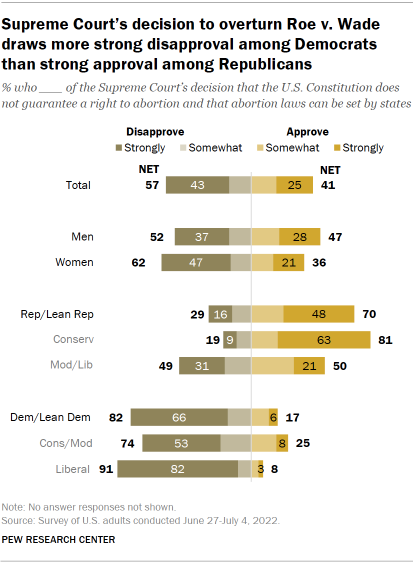

A majority of the U.S. public disapproves of the Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe. About six-in-ten adults (57%) disapprove of the court’s decision that the U.S. Constitution does not guarantee a right to abortion and that abortion laws can be set by states, including 43% who strongly disapprove, according to the summer survey. About four-in-ten (41%) approve, including 25% who strongly approve.

About eight-in-ten Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (82%) disapprove of the court’s decision, including nearly two-thirds (66%) who strongly disapprove. Most Republicans and GOP leaners (70%) approve , including 48% who strongly approve.

Most women (62%) disapprove of the decision to end the federal right to an abortion. More than twice as many women strongly disapprove of the court’s decision (47%) as strongly approve of it (21%). Opinion among men is more divided: 52% disapprove (37% strongly), while 47% approve (28% strongly).

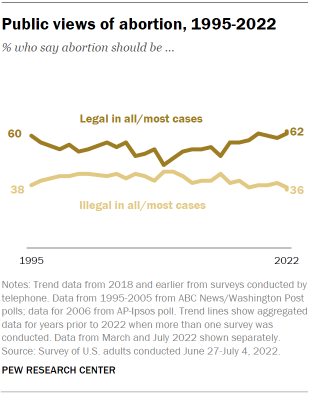

About six-in-ten Americans (62%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, according to the summer survey – little changed since the March survey conducted just before the ruling. That includes 29% of Americans who say it should be legal in all cases and 33% who say it should be legal in most cases. About a third of U.S. adults (36%) say abortion should be illegal in all (8%) or most (28%) cases.

Generally, Americans’ views of whether abortion should be legal remained relatively unchanged in the past few years , though support fluctuated somewhat in previous decades.

Relatively few Americans take an absolutist view on the legality of abortion – either supporting or opposing it at all times, regardless of circumstances. The March survey found that support or opposition to abortion varies substantially depending on such circumstances as when an abortion takes place during a pregnancy, whether the pregnancy is life-threatening or whether a baby would have severe health problems.

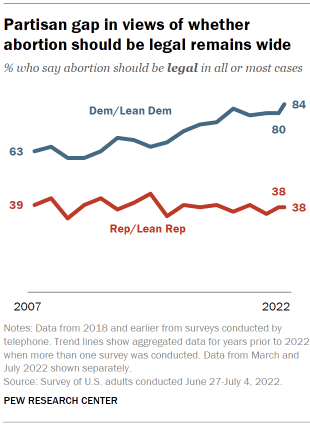

While Republicans’ and Democrats’ views on the legality of abortion have long differed, the 46 percentage point partisan gap today is considerably larger than it was in the recent past, according to the survey conducted after the court’s ruling. The wider gap has been largely driven by Democrats: Today, 84% of Democrats say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, up from 72% in 2016 and 63% in 2007. Republicans’ views have shown far less change over time: Currently, 38% of Republicans say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, nearly identical to the 39% who said this in 2007.

However, the partisan divisions over whether abortion should generally be legal tell only part of the story. According to the March survey, sizable shares of Democrats favor restrictions on abortion under certain circumstances, while majorities of Republicans favor abortion being legal in some situations , such as in cases of rape or when the pregnancy is life-threatening.

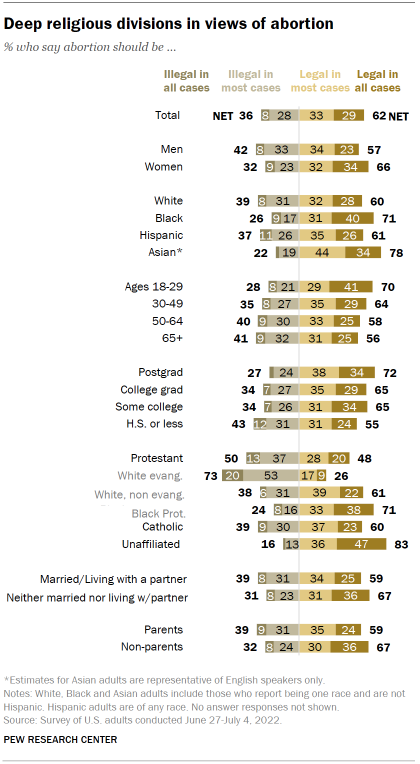

There are wide religious divides in views of whether abortion should be legal , the summer survey found. An overwhelming share of religiously unaffiliated adults (83%) say abortion should be legal in all or most cases, as do six-in-ten Catholics. Protestants are divided in their views: 48% say it should be legal in all or most cases, while 50% say it should be illegal in all or most cases. Majorities of Black Protestants (71%) and White non-evangelical Protestants (61%) take the position that abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while about three-quarters of White evangelicals (73%) say it should be illegal in all (20%) or most cases (53%).

In the March survey, 72% of White evangelicals said that the statement “human life begins at conception, so a fetus is a person with rights” reflected their views extremely or very well . That’s much greater than the share of White non-evangelical Protestants (32%), Black Protestants (38%) and Catholics (44%) who said the same. Overall, 38% of Americans said that statement matched their views extremely or very well.

Catholics, meanwhile, are divided along religious and political lines in their attitudes about abortion, according to the same survey. Catholics who attend Mass regularly are among the country’s strongest opponents of abortion being legal, and they are also more likely than those who attend less frequently to believe that life begins at conception and that a fetus has rights. Catholic Republicans, meanwhile, are far more conservative on a range of abortion questions than are Catholic Democrats.

Women (66%) are more likely than men (57%) to say abortion should be legal in most or all cases, according to the survey conducted after the court’s ruling.

More than half of U.S. adults – including 60% of women and 51% of men – said in March that women should have a greater say than men in setting abortion policy . Just 3% of U.S. adults said men should have more influence over abortion policy than women, with the remainder (39%) saying women and men should have equal say.

The March survey also found that by some measures, women report being closer to the abortion issue than men . For example, women were more likely than men to say they had given “a lot” of thought to issues around abortion prior to taking the survey (40% vs. 30%). They were also considerably more likely than men to say they personally knew someone (such as a close friend, family member or themselves) who had had an abortion (66% vs. 51%) – a gender gap that was evident across age groups, political parties and religious groups.

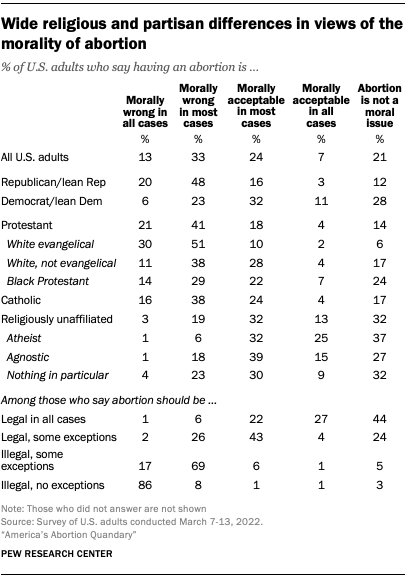

Relatively few Americans view the morality of abortion in stark terms , the March survey found. Overall, just 7% of all U.S. adults say having an abortion is morally acceptable in all cases, and 13% say it is morally wrong in all cases. A third say that having an abortion is morally wrong in most cases, while about a quarter (24%) say it is morally acceptable in most cases. An additional 21% do not consider having an abortion a moral issue.

Among Republicans, most (68%) say that having an abortion is morally wrong either in most (48%) or all cases (20%). Only about three-in-ten Democrats (29%) hold a similar view. Instead, about four-in-ten Democrats say having an abortion is morally acceptable in most (32%) or all (11%) cases, while an additional 28% say it is not a moral issue.

White evangelical Protestants overwhelmingly say having an abortion is morally wrong in most (51%) or all cases (30%). A slim majority of Catholics (53%) also view having an abortion as morally wrong, but many also say it is morally acceptable in most (24%) or all cases (4%), or that it is not a moral issue (17%). Among religiously unaffiliated Americans, about three-quarters see having an abortion as morally acceptable (45%) or not a moral issue (32%).

- Religion & Abortion

Carrie Blazina is a former digital producer at Pew Research Center .

Cultural Issues and the 2024 Election

Support for legal abortion is widespread in many places, especially in europe, public opinion on abortion, americans overwhelmingly say access to ivf is a good thing, broad public support for legal abortion persists 2 years after dobbs, most popular.

901 E St. NW, Suite 300 Washington, DC 20004 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

© 2024 Pew Research Center

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How the Right to Legal Abortion Changed the Arc of All Women’s Lives

I’ve never had an abortion. In this, I am like most American women. A frequently quoted statistic from a recent study by the Guttmacher Institute, which reports that one in four women will have an abortion before the age of forty-five, may strike you as high, but it means that a large majority of women never need to end a pregnancy. (Indeed, the abortion rate has been declining for decades, although it’s disputed how much of that decrease is due to better birth control, and wider use of it, and how much to restrictions that have made abortions much harder to get.) Now that the Supreme Court seems likely to overturn Roe v. Wade sometime in the next few years—Alabama has passed a near-total ban on abortion, and Ohio, Georgia, Kentucky, Mississippi, and Missouri have passed “heartbeat” bills that, in effect, ban abortion later than six weeks of pregnancy, and any of these laws, or similar ones, could prove the catalyst—I wonder if women who have never needed to undergo the procedure, and perhaps believe that they never will, realize the many ways that the legal right to abortion has undergirded their lives.

Legal abortion means that the law recognizes a woman as a person. It says that she belongs to herself. Most obviously, it means that a woman has a safe recourse if she becomes pregnant as a result of being raped. (Believe it or not, in some states, the law allows a rapist to sue for custody or visitation rights.) It means that doctors no longer need to deny treatment to pregnant women with certain serious conditions—cancer, heart disease, kidney disease—until after they’ve given birth, by which time their health may have deteriorated irretrievably. And it means that non-Catholic hospitals can treat a woman promptly if she is having a miscarriage. (If she goes to a Catholic hospital, she may have to wait until the embryo or fetus dies. In one hospital, in Ireland, such a delay led to the death of a woman named Savita Halappanavar, who contracted septicemia. Her case spurred a movement to repeal that country’s constitutional amendment banning abortion.)

The legalization of abortion, though, has had broader and more subtle effects than limiting damage in these grave but relatively uncommon scenarios. The revolutionary advances made in the social status of American women during the nineteen-seventies are generally attributed to the availability of oral contraception, which came on the market in 1960. But, according to a 2017 study by the economist Caitlin Knowles Myers, “The Power of Abortion Policy: Re-Examining the Effects of Young Women’s Access to Reproductive Control,” published in the Journal of Political Economy , the effects of the Pill were offset by the fact that more teens and women were having sex, and so birth-control failure affected more people. Complicating the conventional wisdom that oral contraception made sex risk-free for all, the Pill was also not easy for many women to get. Restrictive laws in some states barred it for unmarried women and for women under the age of twenty-one. The Roe decision, in 1973, afforded thousands upon thousands of teen-agers a chance to avoid early marriage and motherhood. Myers writes, “Policies governing access to the pill had little if any effect on the average probabilities of marrying and giving birth at a young age. In contrast, policy environments in which abortion was legal and readily accessible by young women are estimated to have caused a 34 percent reduction in first births, a 19 percent reduction in first marriages, and a 63 percent reduction in ‘shotgun marriages’ prior to age 19.”

Access to legal abortion, whether as a backup to birth control or not, meant that women, like men, could have a sexual life without risking their future. A woman could plan her life without having to consider that it could be derailed by a single sperm. She could dream bigger dreams. Under the old rules, inculcated from girlhood, if a woman got pregnant at a young age, she married her boyfriend; and, expecting early marriage and kids, she wouldn’t have invested too heavily in her education in any case, and she would have chosen work that she could drop in and out of as family demands required.

In 1970, the average age of first-time American mothers was younger than twenty-two. Today, more women postpone marriage until they are ready for it. (Early marriages are notoriously unstable, so, if you’re glad that the divorce rate is down, you can, in part, thank Roe.) Women can also postpone childbearing until they are prepared for it, which takes some serious doing in a country that lacks paid parental leave and affordable childcare, and where discrimination against pregnant women and mothers is still widespread. For all the hand-wringing about lower birth rates, most women— eighty-six per cent of them —still become mothers. They just do it later, and have fewer children.

Most women don’t enter fields that require years of graduate-school education, but all women have benefitted from having larger numbers of women in those fields. It was female lawyers, for example, who brought cases that opened up good blue-collar jobs to women. Without more women obtaining law degrees, would men still be shaping all our legislation? Without the large numbers of women who have entered the medical professions, would psychiatrists still be telling women that they suffered from penis envy and were masochistic by nature? Would women still routinely undergo unnecessary hysterectomies? Without increased numbers of women in academia, and without the new field of women’s studies, would children still be taught, as I was, that, a hundred years ago this month, Woodrow Wilson “gave” women the vote? There has been a revolution in every field, and the women in those fields have led it.

It is frequently pointed out that the states passing abortion restrictions and bans are states where women’s status remains particularly low. Take Alabama. According to one study , by almost every index—pay, workforce participation, percentage of single mothers living in poverty, mortality due to conditions such as heart disease and stroke—the state scores among the worst for women. Children don’t fare much better: according to U.S. News rankings , Alabama is the worst state for education. It also has one of the nation’s highest rates of infant mortality (only half the counties have even one ob-gyn), and it has refused to expand Medicaid, either through the Affordable Care Act or on its own. Only four women sit in Alabama’s thirty-five-member State Senate, and none of them voted for the ban. Maybe that’s why an amendment to the bill proposed by State Senator Linda Coleman-Madison was voted down. It would have provided prenatal care and medical care for a woman and child in cases where the new law prevents the woman from obtaining an abortion. Interestingly, the law allows in-vitro fertilization, a procedure that often results in the discarding of fertilized eggs. As Clyde Chambliss, the bill’s chief sponsor in the state senate, put it, “The egg in the lab doesn’t apply. It’s not in a woman. She’s not pregnant.” In other words, life only begins at conception if there’s a woman’s body to control.

Indifference to women and children isn’t an oversight. This is why calls for better sex education and wider access to birth control are non-starters, even though they have helped lower the rate of unwanted pregnancies, which is the cause of abortion. The point isn’t to prevent unwanted pregnancy. (States with strong anti-abortion laws have some of the highest rates of teen pregnancy in the country; Alabama is among them.) The point is to roll back modernity for women.

So, if women who have never had an abortion, and don’t expect to, think that the new restrictions and bans won’t affect them, they are wrong. The new laws will fall most heavily on poor women, disproportionately on women of color, who have the highest abortion rates and will be hard-pressed to travel to distant clinics.

But without legal, accessible abortion, the assumptions that have shaped all women’s lives in the past few decades—including that they, not a torn condom or a missed pill or a rapist, will decide what happens to their bodies and their futures—will change. Women and their daughters will have a harder time, and there will be plenty of people who will say that they were foolish to think that it could be otherwise.

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- Games & Quizzes

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Our editors will review what you’ve submitted and determine whether to revise the article.

- WebMD - Abortion

- National Women's Law Center - Roe v. Wade and the Right to Abortion

- eMedicineHealth - Abortion

- NHS - Abortion

- National Center for Biotechnology Information - Abortion

- Merck Manual - Consumer Version - Abortion

- abortion - Student Encyclopedia (Ages 11 and up)

Recent News

abortion , the expulsion of a fetus from the uterus before it has reached the stage of viability (in human beings, usually about the 20th week of gestation). An abortion may occur spontaneously, in which case it is also called a miscarriage , or it may be brought on purposefully, in which case it is often called an induced abortion.

Spontaneous abortions, or miscarriages, occur for many reasons, including disease, trauma, genetic defect, or biochemical incompatibility of mother and fetus. Occasionally a fetus dies in the uterus but fails to be expelled, a condition termed a missed abortion.

Induced abortions may be performed for reasons that fall into four general categories: to preserve the life or physical or mental well-being of the mother; to prevent the completion of a pregnancy that has resulted from rape or incest; to prevent the birth of a child with serious deformity, mental deficiency , or genetic abnormality; or to prevent a birth for social or economic reasons (such as the extreme youth of the pregnant female or the sorely strained resources of the family unit). By some definitions, abortions that are performed to preserve the well-being of the female or in cases of rape or incest are therapeutic, or justifiable, abortions.

Numerous medical techniques exist for performing abortions. During the first trimester (up to about 12 weeks after conception), endometrial aspiration , suction, or curettage may be used to remove the contents of the uterus. In endometrial aspiration, a thin flexible tube is inserted up the cervical canal (the neck of the womb) and then sucks out the lining of the uterus (the endometrium) by means of an electric pump.

In the related but slightly more onerous procedure known as dilatation and evacuation (also called suction curettage or vacuum curettage), the cervical canal is enlarged by the insertion of a series of metal dilators while the patient is under anesthesia , after which a rigid suction tube is inserted into the uterus to evacuate its contents. When, in place of suction, a thin metal tool called a curette is used to scrape (rather than vacuum out) the contents of the uterus, the procedure is called dilatation and curettage. When combined with dilatation, both evacuation and curettage can be used up to about the 16th week of pregnancy.

From 12 to 19 weeks the injection of a saline solution may be used to trigger uterine contractions; alternatively, the administration of prostaglandins by injection, suppository, or other method may be used to induce contractions, but these substances may cause severe side effects. Hysterotomy, the surgical removal of the uterine contents, may be used during the second trimester or later. In general, the more advanced the pregnancy, the greater the risk to the female of mortality or serious complications following an abortion.

In the late 20th century a new method of induced abortion was discovered that uses the drug RU-486 (mifepristone), an artificial steroid that is closely related to the contraceptive hormone norethnidrone. RU-486 works by blocking the action of the hormone progesterone, which is needed to support the development of a fertilized egg. When ingested within weeks of conception , RU-486 effectively triggers the menstrual cycle and flushes the fertilized egg out of the uterus. RU-486 is typically used in combination with another drug, misoprostol, which softens the cervix and induces uterine contractions. By 2020 the two-drug combination, commonly referred to as a “medication abortion” or the “abortion pill,” accounted for more than half of all abortions in the United States .

Whether and to what extent induced abortions should be permitted, encouraged, or severely repressed is a social issue that has divided theologians, philosophers, and legislators for centuries. Abortion was apparently a common and socially accepted method of family limitation in the Greco-Roman world. Although Christian theologians early and vehemently condemned abortion, the application of severe criminal sanctions to deter its practice became common only in the 19th century. In the 20th century such sanctions were modified in one way or another in various countries, beginning with the Soviet Union in 1920, with Scandinavian countries in the 1930s, and with Japan and several eastern European countries in the 1950s. In some countries the unavailability of birth control devices was a factor in the acceptance of abortion. In the late 20th century China used abortion on a large scale as part of its population control policy. In the early 21st century some jurisdictions with large Roman Catholic populations, such as Portugal and Mexico City , decriminalized abortion despite strong opposition from the church, while others, such as Nicaragua, increased restrictions on it.

A broad social movement for the relaxation or elimination of restrictions on abortion resulted in the passing of liberalized legislation in several states in the United States during the 1960s. The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Roe v. Wade (1973) that unduly restrictive state regulation of abortion was unconstitutional, in effect legalizing abortion for any reason for women in the first three months of pregnancy. A countermovement for the restoration of strict control over the circumstances under which abortions might be permitted soon sprang up, and the issue became entangled in social and political conflict. In rulings in 1989 ( Webster v. Reproductive Health Services ) and 1992 ( Planned Parenthood v. Casey ), a more conservative Supreme Court upheld the legality of new state restrictions on abortion, though it proved unwilling to overturn Roe v. Wade itself. In 2007 the Court also upheld a federal ban on a rarely used abortion method known as intact dilation and evacuation. In a later ruling, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization (2022), the Court overturned both Roe and Casey , holding that there is no constitutional right to abortion. Following the Court’s decision in Dobbs , several states adopted new (or reinstated old) abortion restrictions or banned the procedure altogether.

In April 2023 a federal district court judge in Texas issued an order effectively invalidating the federal Food and Drug Administration ’s (FDA) approval of RU-486 in 2000. An approximately simultaneous order by a federal district court judge in Washington state prohibited the FDA from further limiting access to RU-486 in 17 states and the District of Columbia . Shortly after the two rulings, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit temporarily blocked the Texas judge’s finding that RU-486 had been improperly approved but declined to reverse his separate stays of measures that the FDA had taken since 2016 to make RU-486 accessible to more patients, including extending the period during which the drug could be used from 7 to 10 weeks of pregnancy and permitting the drug to be mailed to patients rather than administered at an in-person visit with a doctor. The administration of Pres. Joe Biden then submitted an emergency appeal to the Supreme Court, asking that it temporarily uphold the FDA’s approval of RU-486 and its measures since 2016 to make the drug more accessible. One week later the Supreme Court granted the administration’s request. In December 2023, following the Fifth Circuit’s decision in August upholding the district court’s invalidation of the FDA’s accessibility measures since 2016, the Supreme Court agreed to review the case, Food and Drug Administration v. Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine , the first major abortion-related case on its docket since Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization . On June 13, 2024, the Court unanimously reversed and remanded the Fifth’s Circuit’s decision, holding that the original plaintiffs in the case—a group of pro-life medical associations and several individual doctors—lacked standing to sue .

The public debate of the abortion issue has demonstrated the enormous difficulties experienced by political institutions in grappling with the complex and ambiguous ethical problems raised by the question of abortion. Opponents of abortion, or of abortion for any reason other than to save the life of the mother, argue that there is no rational basis for distinguishing the fetus from a newborn infant; each is totally dependent and potentially a member of society, and each possesses a degree of humanity. Proponents of liberalized regulation of abortion hold that only a woman herself, rather than the state, has the right to manage her pregnancy and that the alternative to legal, medically supervised abortion is illegal and demonstrably dangerous, if not deadly, abortion.

The Hastings Center

- Bioethics and Policy—A History Daniel Callahan

- The Hastings Center Bioethics Timeline

- Abortion Bonnie Steinbock

- Aging Daniel Callahan

- Brain Injury: Neuroscience and Neuroethics Joseph J. Fins

- Clinical Trials Christine Grady, RN, PhD

- Climate Change David B. Resnik

- Conflict of Interest in Biomedical Research and Clinical Practice Josephine Johnston, Bethany Brumbaugh

- Conscience Clauses, Health Care Providers, and Parents Nancy Berlinger

- Disaster Planning and Public Health Bruce Jennings

- End-of-Life Care Kathy L. Cerminara, Alan Meisel

- Enhancing Humans Cristina J. Kapustij, Mark S. Frankel

- Environment, Ethics, and Human Health David B. Resnik, Christopher J. Portier

- Family Caregiving Carol Levine

- Genomics, Behavior, and Social Outcomes Daphne O. Martschenko, Lucas J. Matthews

- Law Enforcement and Genetic Data James W. Hazel, Ellen Wright Clayton

- Medical Aid-in-Dying Timothy E. Quill, Bernard Sussman

- Nature, Human Nature, and Biotechnology Gregory E. Kaebnick

- Neonatal Care Jennifer McGuirl, Alan R. Fleischman

- Newborn Screening Mary Ann Baily

- Organ Transplantation Arthur Caplan, Brendan Parent

- Pandemics: The Ethics of Mandatory and Voluntary Interventions

- Public Health Ethics and Law Lawrence O. Gostin, Lindsay F. Wiley

- Quality Improvement Methods in Health Care Mary Ann Baily

- Racism and Health Equity Keisha Ray

- Research in Resource-Poor Countries Voo Teck Chuan, G. Owen Schaefer

- Sports Enhancement Thomas H. Murray

- Stem Cells Insoo Hyun

- Torture: The Bioethics Perspective Steven H. Miles

From Bioethics Briefings

- Abortion remains controversial.

- In recent years, several states, including Texas and Oklahoma, have passed abortion bans early in pregnancy.

- For nearly 50 years, there was a Constitutional right to abortion in the United States, established by the Supreme Court in Roe v. Wade in 1973

- The Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade in June 2022, eliminating the Constitutional right to abortion.

- A central ethical question in the abortion debate is over the moral status of the fetus.

- Opinions range from the belief that the fetus is a human being with full moral status and rights from conception to the belief that a fetus has no rights, even if it is human in a biological sense. Most Americans’ beliefs fall somewhere in the middle.

- Moral philosophers from various perspectives provide nuanced examinations of the abortion question that go beyond the standard political breakdowns.

Framing the Issue

Abortion has been one of the most divisive and emotionally charged issues in American politics. At one end of the debate are those who regard abortion as murder, a despicable and heinous crime. At the other end of the spectrum are those who regard any attempt to restrict abortion as an egregious violation of women’s rights to make their own decisions about their bodies and what is best for them and their families. Most Americans are somewhere in the middle.

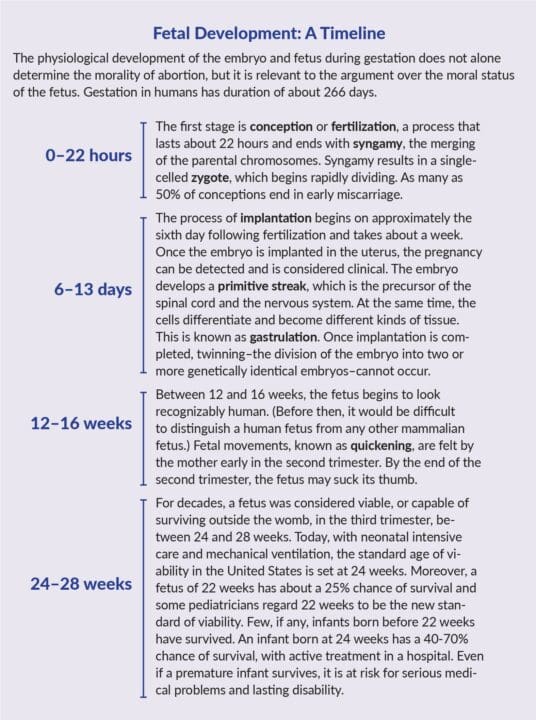

A central philosophical question in the abortion debate concerns the moral status of the embryo and fetus. If the fetus is a person, with the same right to life as any human being who has been born, it would seem that very few, if any, abortions could be justified, because it is not morally permissible to kill children because they are unwanted or illegitimate or disabled. However, the morality of abortion is not settled so straightforwardly. Even if one accepts the argument that the fetus is a person, it does not automatically follow that it has a right to the use of the pregnant woman’s body. Thus, the morality of abortion depends not only on the moral status of the fetus, but also on whether the pregnant woman has an obligation to continue to gestate the fetus.

Ethical Considerations Around Abortion

Public opinion on abortion falls into three camps—conservative, liberal, and moderate (or gradualist)—each of which draws on both science and ethical thinking.

Conservative

Conservative opposition to abortion stems from the conviction that the fetus is a human being, with the same rights as any born human being, from the beginning of pregnancy onward. Some conservative groups—such as the Catholic Church—consider the fetus to be a human being with full moral rights even earlier than the beginning of pregnancy, which occurs when the embryo implants in the uterus. The Church regards the embryo as a full human being from conception (the conjoining of sperm and egg). This is because at conception the embryo receives its own unique genetic code, distinct from that of its mother or father. Therefore, Catholic doctrine regards conception, not implantation, as the beginning of the life of a human being.

Although conservatives concede that the fetus changes dramatically during gestation, they do not accept these changes as relevant to moral standing. Conservatives argue that there is no stage of development at which we can say, now we have a human being, whereas a day or a week or a month earlier we did not. Any attempt to place the onset of humanity at a particular moment—whether it be when brain waves appear, or when the fetus begins to look human, or when quickening, sentience, or viability occur —is bound to be arbitrary because all of these stages will occur if the fetus is allowed to grow and develop.

A secular antiabortion argument given by Don Marquis in 1989 differs from the traditional conservative view in that it is not based on the fetus’s being human, thus avoiding the charge of “speciesism.” Rather, Marquis argues that abortion is wrong for the same reason that killing anyone is wrong—namely, that killing deprives its victim of a valuable future, what he calls “a future like ours.” It is possible that some nonhumans (some animals or aliens) have a future like ours. If so, then killing them is also wrong.

This raises two questions about what it is to have a future like ours. First, what precisely is involved in this notion? Does it essentially belong to rational, future-oriented, plan-making beings? If so, then killing most nonhuman animals would not be wrong, but neither would killing those who are severely developmentally disabled. Second, at what point does the life of a being with a future like ours start? Marquis assumes that we are essentially human animals, so our lives start with the beginning of our organisms. But Jeff McMahan denies this, arguing that we are essentially embodied minds, and not human organisms. On McMahan’s view, our lives do not start until our organism becomes conscious, probably some time in the second trimester. Early abortion, on his view, does not kill someone with a future like ours, but rather prevents that individual from coming into existence – in much the way contraception does.

The pro-choice position on abortion is often referred to as the liberal view. Mary Anne Warren provides a classic statement of the liberal view. Warren does not dispute the conservative’s claim that the fetus is biologically human, but she denies that biological humanity is either necessary or sufficient for personhood and a right to life. She argues that basing moral standing on species membership is arbitrary, and maintains that it is the killing of persons , not humans, that is wrong. Indeed, Warren thinks that the conservative is guilty of a logical mistake: confusing biological humans and persons. Persons are beings with certain psychological traits, including sentience, consciousness, the capacity for rational thought, and the ability to use language. There may be some nonhuman persons (e.g., some animals, extraterrestrial aliens), and there may be biological humans that are not persons, including early gestation fetuses, who have no person-making characteristics. By the end of the second trimester, fetuses are probably sentient, but even late gestation fetuses are less personlike than most mammals who are not considered to be persons.

In 1971, Judith Thomson gave a completely different pro-choice argument from the classic liberal one, in which she maintained that even if the personhood of the fetus were granted, for the sake of the argument, this would not settle the morality of abortion because the fetus’s right to life does not necessarily give it a right to use the pregnant woman’s body. No one, Thomson says, has the right to use your body unless you give him permission—not even if he needs it for life itself. At least in the case of rape, the pregnant woman has not given the fetus the right to use her body. (Thus, Thomson’s argument, somewhat ironically for an article entitled “A Defense of Abortion,” provides those who are generally anti-choice with a rationale for making an exception in the case of rape, as do many pro-lifers—though not the Catholic Church.) Thomson maintains that whether a woman has a moral obligation to allow a fetus to remain in her body is a separate question from whether the fetus is a person with a right to life, and depends instead on the amount of sacrifice or burden it imposes on her.

In 2003, Margaret Little argued that while abortion is not murder, neither is it necessarily moral. A pregnant woman and her fetus are not strangers; she is biologically its mother which provides her with some reason to protect its life. However, she may have duties of care to others, such as her existing children, which would be more difficult to fulfill if she has another child. The typical abortion patient is already a mother, single, and low-income or poor. Although Little does not regard the fetus as a person, it is a “burgeoning human life,” and as such is worthy of respect. But abortion does not necessarily conflict with respect for human life. Many women regard bringing a child into the world when they are not able to care for it properly as itself disrespectful of human life.

The moderate, or gradualist, agrees with the classic liberal that an early fetus, much less a one-celled zygote, is not a person, but agrees with the conservative that the late-gestation fetus merits some moral concern because it is virtually identical to a born infant. Thus, the moderate thinks that early abortions are morally better than late ones and that the reasons for having one should be stronger as the pregnancy progresses. A reason that might justify an early abortion, such as not wanting to become a mother, would not justify an abortion in the seventh month to the moderate.

Fetal Development Timeline (pdf)

The Legal Perspective

In Roe v. Wade , the Supreme Court based its finding of a woman’s constitutional right to abortion prior to fetal viability on two factors: the legal status of the fetus and the woman’s right to privacy. Concluding that outside of abortion law, the unborn had never been treated as full legal persons, the Court then looked to see if there were any state interests compelling enough to override a woman’s right to make this momentous personal decision for herself. It decided that there were none at all in the first trimester of pregnancy. In the second trimester, the state’s interest in protecting maternal health allows for some restrictions, so long as these are actually related to maternal health and not the protection of the life of the fetus. The state’s interest in protecting potential life becomes “compelling,” and trumps the woman’s right to privacy only after the fetus becomes viable, which in 1973 was somewhere between 24 and 28 weeks. Today, some premature infants are being saved as early as 22 weeks. However, it appears that, absent development of an artificial placenta, 22 weeks represents an absolute lower limit on viability. After viability, states may prohibit abortion altogether if they choose, unless continuing the pregnancy would threaten the woman’s life or health.

Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey (1992) pitted the Justices who wanted to reverse Roe against those who wished to preserve it. Neither side prevailed and the result was a compromise written by Justices O’Connor, Kennedy, and Souter. It upheld Roe’s central finding, that women have a constitutionally protected right to choose abortion, prior to viability, while rejecting the trimester framework. Casey held that the State’s profound interest in protecting potential life existed at all stages of pregnancy, not just after viability. States may enact procedures and rules reflecting its preference for childbirth over abortion, so long as these rules and procedures do not constitute an “undue burden” on the woman’s choice.

The Court interpreted the undue burden standard as permitting a requirement that required doctors to provide information about the abortion procedure, the relative risks of abortion and childbirth, embryonic and fetal development, and available resources should the woman choose to carry to term, provided the information given to the woman is truthful and not misleading. This qualification has not always been followed. In several states, doctors are required to tell women seeking abortions that having an abortion increases their risk of breast cancer. While not exactly a lie, this is certainly misleading. Having a full term pregnancy can reduce the risk of breast cancer, but having an abortion does not increase a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer. The Court also upheld a waiting period of 24 hours, as its intent is to make the abortion decision more informed and deliberate. Yet the actual effect of waiting periods is often to make abortion access much more difficult, especially in places where women have to travel long distances to find an abortion provider.

After attempts to overturn Roe failed, a new strategy of restricting abortions was developed. This strategy included outlawing particular methods of abortion, such as partial-birth abortion, imposing time limits based on claims of fetal sentience, and imposing restrictions on clinics and doctors who perform abortions in the name of protecting maternal health.

Fetal Sentience

In 2010, Nebraska banned all abortion after 20 weeks, on the ground that the fetus at that stage can feel pain. Subsequently, more than a third of states passed similar laws. In 2015, the Pain-Capable Unborn Child Protection Act passed the House of Representatives; the motion to consider the bill in the Senate was withdrawn. The bill prohibited a physician from performing an abortion after 20 weeks, except where necessary to save the life of a pregnant woman (excluding psychological or emotional conditions) or in cases of rape or incest against a minor.

Are 20-week old fetuses sentient? This claim is rejected by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, which says it knows of no legitimate scientific information that supports the claim that a 20-week old fetus can feel pain. Other researchers think that while we do not know when fetuses become sentient, it might occur as early as 17 weeks. Utah became the first state to require doctors to give anesthesia to women having an abortion at 20 weeks or later. The law, which went into effect in May 2016, would not apply to women having abortions needed to save their lives, or in cases of rape or incest. An obstetrician-gynecologist in Utah, who spends half of a Saturday each month in an abortion clinic, protested, “You’re asking me to invent a procedure that doesn’t have any research to back it up. You want me to experiment on my patients.”

Protecting Women’s Health

Casey allowed states to restrict abortions based on a concern for women’s health, so long as the restrictions did not impose an undue burden on the choice. A key issue raised by the Supreme Court case Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, decided in 2016, was how judges should evaluate such health-justified restrictions. The case concerned a 2013 Texas law that required any physician performing an abortion to have admitting privileges at a hospital not further than 30 miles from the abortion facility, and required any abortion facility to meet the minimum standards for ambulatory surgical centers. The District Court said that the law was unconstitutional because of its impact on access to abortion in Texas. Many abortion facilities would be unable to meet these requirements and would be forced to close, thereby severely limiting access to abortion. Moreover, the law’s provisions were unnecessary to protect women’s health. Abortion is an extremely safe medical procedure with very low rates of complications and virtually no deaths. In fact, although childbirth is 14 times more likely than abortion to result in death, Texas law allows a midwife to oversee childbirth in the patient’s own home. Thus, the new law was a solution to which there was no problem.

The Fifth Circuit reversed the District Court decision. One of its more startling claims was that states are entitled to impose health-justified restrictions, which are not subject to judicial review. In a 5-3 decision, the Supreme Court roundly rejected this claim. Writing for the majority, Justice Breyer said, “. . . the Court, when determining the constitutionality of laws regulating abortion procedures, has placed considerable weight upon evidence and argument presented in judicial procedures.” In other words, states may not simply assert that the restrictions are necessary, but must have factual evidence to show that they are. Moreover, the Court has an independent constitutional duty to review factual findings where constitutional rights are at stake.

Despite new restrictions on abortion, the core principle of Roe and Casey– that the right to abortion is protected by the Constitution — was upheld. But that was soon to change.

The Change in the Composition of the Supreme Court

Between 1991 and 2020, five Justices openly hostile to abortion (Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito, Neil Gorsuch, Brett Kavanaugh, and Amy Barrett) were appointed to the Court, making the 6-3 decision to reverse Roe possible.

The change in the Court’s composition emboldened several states to pass abortion bans much earlier than viability. One of the most restrictive, signed into law by Texas Governor Greg Abbott in May 2021, prohibits abortions after a fetal heartbeat is detected, usually after six weeks of pregnancy. About a year later, Oklahoma adopted a similar restriction and made illegal abortion a felony punishable by up to 10 years in prison. A bill introduced in Louisiana (House Bill 813) in May 2022 allowed criminal charges for murder to be brought against those who perform or have abortions. Its sponsor, Republican Danny McCormick, justified the bill by saying, “it is actually very simple: Abortion is murder.” Louisiana Right to Life did not support the bill, since their policy is that “abortion-vulnerable women” should not be treated as criminals. The group also called the bill unnecessary since Louisiana already had a trigger law that would outlaw abortion, except when necessary to save the life of the mother, if Roe were overturned. An amended version of HB 813, which removed the language about charging women having abortions with murder and exempted birth control from being outlawed, did pass the House.

Overturning Roe and Casey

Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health (June 2022) . The case concerned a Mississippi law banning all abortions after 15 weeks gestational age except in medical emergencies and in the case of severe fetal abnormality. Characterizing the decisions in Roe and Casey as “egregiously wrong,” the majority held that:

“. . . Roe and Casey must be overruled. The Constitution makes no reference to abortion, and no such right is implicitly protected by any constitutional provision, including the one on which the defenders of Roe and Casey now chiefly rely — the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. That provision has been held to guarantee some rights that are not mentioned in the Constitution, but any such right must be “deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition” and “implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.”

With the overturning of Roe and Casey , the matter of abortion has been returned to the states. Most abortions are banned in 14 states, while protected by state law or constitution in 21 states. (For updates, see Kaiser Health News Abortion Policy Tracker .) Abortion providers and advocates have challenged abortion bans in many states as violating the state constitution or another state law.

In his concurrence, Chief Justice Roberts said that while he agreed with the majority’s conclusion to uphold Mississippi’s law, he would have preferred a narrower approach based on the principle of judicial restraint. Instead of “repudiating a constitutional right we have not only previously recognized, but also expressly reaffirmed applying the doctrine of stare decisis “, the Court could simply have rejected viability as the point at which the state’s interest in protecting potential life outweighed the woman’s right to terminate her pregnancy, and upheld Mississippi’s right to ban abortions after 15 weeks. The majority rejected this approach, in part because it “would only put off the day when we would be forced to confront the question we now decide. The turmoil wrought by Roe and Casey would be prolonged. It is far better–for this Court and the country–to face up to the real issue without further delay.”

Abortion After Dobbs

The claim that Dobbs will end the turmoil over abortion is dubious. Abortion rights activists have challenged trigger bans in a dozen states. Some have already been rejected by judges, but other cases continue. Most of the legal challenges nationwide seek to establish that state constitutions protect a right to abortion. President Biden has signed an executive order designed to ensure access to abortion medication and emergency contraception, leaving the details up to the secretary of health and human services.

Court cases have challenged the availability of medication abortion . Another issue likely to result in lawsuits is whether states can prevent their residents from traveling to other states to have abortions. Nor are legal battles necessarily limited to the states. Some anti-abortion activists are pushing for a federal ban on abortion, while some pro-choice advocates are pushing for a federal law to protect the right to abortion. Neither side has the 60 votes necessary, but that could change in the future.

The Supreme Court expressly noted that its opinion “is not based on any view about if and when prenatal life is entitled to any of the rights enjoyed after birth.” That leaves open the question whether states may confer legal personhood on embryos. May they punish women who have abortions under their homicide statutes, even executing them in death penalty states?

The extreme conservative position, taken by the official teachings of the Roman Catholic Church, regards even abortions necessary to save the life of the pregnant woman as illicit, since it is forbidden to kill one innocent human being in order to save the life of another. As of July 2022, all of the state anti-abortion laws and proposed laws make an exception for “medical emergencies,” but nothing in Dobbs requires states to make this exception. Moreover, the determination of what counts as a medical emergency can be extremely subjective. A pregnant woman may develop a condition that might be, but is not definitely, life-threatening. May a doctor perform an abortion in that case? Five women in Texas have filed a lawsuit saying that they were denied medically necessary abortions. Joined by two ob-gyns, they are seeking to clarify when abortion is permissible under state law.

Questions abound. How close to death must a woman be for doctors to act? Will doctors be willing to take the risk of possible jail time if they make a call that is later questioned?

Complications can arise in any pregnancy, but the inability to get an abortion for medical reasons is likely to impose particular burdens on pregnant patients with chronic illnesses and disabilities, including psychiatric conditions, diabetes, and heart conditions. Pregnancy may take years off their lives, but this would not be enough for them to get an abortion in states that provide an exemption only in the case of a “medical emergency” that “necessitate[s] the immediate performance or inducement of an abortion.”

Thus, Dobbs is likely to have a deleterious impact on the ability of doctors to care properly for their pregnant patients, as well as for some women who are not pregnant. The AMA condemned the decision as “an egregious allowance of government intrusion into the medical examination room, a direct attack on the practice of medicine and the patient-physician relationship, and a brazen violation of patients’ rights to evidence-based reproductive health services.” In the weeks after the Dobbs decision, there were reports of profound changes in other medical care, including for ectopic pregnancies and for women with lupus, which is treated with a medicine that can cause miscarriage.

There are no exceptions for pregnancies that result from rape or incest in Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Kentucky, Louisiana, Missouri, Oklahoma, Ohio, South Dakota, Tennessee, or Texas. The rationale is that it is unjust to end a pregnancy because its father is a rapist. Those who favor exceptions for rape and incest regard it as equally unjust to force women to continue a pregnancy for which they have no responsibility.

The Impact of Dobbs Beyond Abortion

The loss of abortion rights is real and of great concern to many Americans, not only because of the impact this will have on the lives of women and their families, but also because a rejection of the constitutional right to privacy and substantive due process could have effects beyond abortion. On the face of it, the analysis in Dobbs applies to other rights that the Supreme Court has upheld, including the right of both married and unmarried couples to use contraceptives ( Griswold v. Connecticut , 1965, and Eisenstadt v. Baird , 1972), the right to marry a person of a different race ( Loving v. Virginia , 1967), the right to engage in private, consensual sexual acts ( Lawrence v. Texas , 2003), and the right to marry a person of the same sex ( Obergefell v. Hodges , 2015). None of these rights are mentioned in the Constitution, nor are they deeply rooted in this Nation’s history and tradition. This means, in the words of the dissenters (Breyer, Sotomayor, and Kagan) that “one of two things must be true. Either the majority does not really believe in its own reasoning. Or if it does, all rights that have no history stretching back to the mid-19th century are insecure. Either the mass of the majority’s opinion is hypocrisy, or additional constitutional rights are under threat. It is one or the other.”

The majority insisted that its decision “concerns the constitutional right to abortion and no other right. Nothing in this opinion should be understood to cast doubt on precedents that do not concern abortion.” But if other precedents fail the test for determining constitutional rights provided in Dobbs , why aren’t these cases also wrongly decided?

Same-Sex Marriage

In his separate concurring opinion, Justice Thomas forthrightly accepted this implication, saying, “in future cases, we should reconsider all of this Court’s substantive due process precedents, including Griswold , Lawrence , and Obergefell .” Thomas, unsurprisingly, did not mention Loving , perhaps because he assumes that discrimination based on race is prohibited by the Fourteenth Amendment’s guarantee of equal protection. The dissenters, however, note that the right to marry someone of a different race was not protected at the time of the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment any more than the rights to abortion, contraception, to engage in private, consensual acts, or to marry a person of the same sex.

While anti-miscegenation laws are unlikely to garner much public support, the same may not be true for LGBTQ rights protected by Lawrence and Obergefell . Some far-right Republicans have expressed an interest in ending same-sex marriage . Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton has said that he would defend the state’s defunct sodomy law if the Supreme Court were to follow Thomas’s suggestion and revisit Lawrence .

Contraception, IVF

It seems unlikely that there would be much enthusiasm in the states for banning contraceptives in general, although some conservatives might favor rolling back the sexual revolution that stemmed from the Pill. Presumably, that would satisfy the rational-basis test that the Court identified as the standard for abortion restrictions or prohibition. Moreover, some forms of contraception, such as IUDs, that prevent a fertilized egg from implanting, might be prohibited under laws like Oklahoma’s that define persons as human beings from conception onwards.

IVF could also be adversely affected by Dobbs , because of the routine practice of discarding embryos. This occurs for two reasons. First, the creation of excess embryos enables fertility doctors to implant only one or two embryos per cycle, and to freeze the remainders for future use. This protects women from having to go through the onerous process of egg retrieval in future pregnancies. Freezing embryos has also facilitated single embryo transfer for good-prognosis patients, which has resulted in fewer twins and higher-multiple births, which are riskier for both mothers and babies than singleton births.

Second, it is now routine in IVF to test embryos for chromosomal defects and to discard affected embryos. This improves the chances for a successful pregnancy since embryos with chromosomal defects are less likely to implant and to miscarry. At this point, embryos created in labs are not explicitly targeted by state laws that ban abortion. Trigger laws in most states are aimed at preventing the termination of pregnancy, not regulating IVF embryos. That could change. A spokeswoman for Students for Life Action, a large national anti-abortion group, says that they are looking at IVF : “Protecting life from the very beginning is our ultimate goal, and in this new legal environment we are researching issues like IVF, especially considering a business model that, by design, ends most of the lives conceived in a lab.” Ironically, laws intended to prevent the termination of pregnancies might deprive infertile couples from having a successful pregnancy.

On February 16, 2024, the Supreme Court of Alabama held that frozen embryos are children with respect to Alabama’s wrongful-death statutes. Some have claimed that this will disallow the discard of embryos by IVF clinics, but that is not obvious. Wrongful-death suits must demonstrate negligence, not simply causing death. Nevertheless, the implications of the court’s decision are unclear, creating anxiety among IVF providers and patients. The University of Alabama health system is pausing in vitro fertilization treatments while considering the implications of the court’s decision.

Care for Miscarrying Patients

Another area of concern is the medical care given to women with wanted pregnancies who miscarry. In what is known as a “missed miscarriage,” the fetus dies in the womb but is not expelled from the woman’s body. In an “incomplete miscarriage,” not all of the fetal tissue is expelled. These situations can cause infection that poses a threat to the woman’s life. The medical options are waiting and hoping that the woman miscarries naturally or intervening medically with either a surgical procedure (D&C) or abortion medication to remove the fetus or fetal tissue. Because these interventions are also used in abortion procedures, outlawing abortion could have a chilling effect on what doctors are willing to do.

In states with abortion bans, there are reports of doctors declining to perform any procedure that could be seen as an illegal abortion. In some cases, women have had to wait to miscarry, which could take weeks. Not only does this impose added emotional stress on women who have lost a wanted pregnancy, but it could even cost their lives. This happened in Ireland in 2012. Savita Halappanavar, 17 weeks pregnant, was admitted to hospital after a miscarriage was deemed inevitable. When she did not miscarry after her water broke, she discussed having a termination with the attending physician. This was denied because Irish law at the time forbade abortion if a heartbeat was still detectable. While they waited for the fetus’s heart to stop, Savita developed sepsis and died. The case was instrumental in getting abortion legalized in Ireland.

So far, no woman in the U.S. has died as a result of restrictive abortion laws, but some have come close. An ob-gyn in San Antonio, Tx., had to wait until the fetal heartbeat stopped to treat a miscarrying patient who had developed a dangerous womb infection. The delay caused complications which required her to have surgery, lose multiple liters of blood, and be put on a breathing machine. Texas law essentially requires doctors to commit malpractice.

Landmark cases like Quinlan (1976) and Cruzan (1990) relied on a constitutional right of privacy and substantive due process. The rejection by the Court of these principles could threaten well-established rights of patients to refuse life-saving care and to stipulate their wishes in that regard in advance directives.

At this point, it is impossible to predict all of the effects of overturning Roe and Casey . This much is clear: the battle over abortion rights is far from over.

Bonnie Steinbock , PhD, a Hastings Center fellow, is professor emeritus of philosophy at The University at Albany/State University of New York.

- Symposium: Seeking Reproductive Justice in the Next 50 Years. The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 51 (Fall 2023): 455.

- Linda Greenhouse and Reva Siegel, “Casey and the Clinic Closings: When ‘Protecting Health’ Obstructs Choice,” Yale Law Review 125 (2016): 1428-1531.

- Bonnie Steinbock, Life Before Birth: The Moral and Legal Status of Embryos and Fetuses, 2nd edition (Oxford University Press, 2011).

- Ronald Dworkin, “The Court and Abortion: Worse Than You Think,” New York Review of Books, May 31, 2007.

- Margaret Olivia Little, “The Morality of Abortion,” in Christopher Wellman and R.G. Frey, eds., A Companion to Applied Ethics (Blackwell Publishing, 2003).

- David Boonin, A Defense of Abortion (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

- Jeff McMahan, The Ethics of Killing: Problems at the Margins of Life (Oxford University Press, 2002).

- Susan Dwyer and Joel Feinberg, eds. The Problem of Abortion (Wadsworth Publishing Co., 1996).

- Sidney Callahan and Daniel Callahan, eds. Abortion: Understanding Differences (Plenum, 1984).

- Kristin Luker, Abortion and the Politics of Motherhood (University of California Press, 1984).

- Don Marquis, “Why Abortion Is Immoral,” Journal of Philosophy, April 1984.

- Donald H. Regan, "Rewriting Roe v. Wade." Michigan Law Review, August 1979.

- Mary Anne Warren, “On the Moral and Legal Status of Abortion,” The Monist, January 1973.

- Judith Thomson, “A Defense of Abortion,” Philosophy and Public Affairs, Winter 1971.

- Ethics and Abortion Resources from The Hastings Center

- Bonnie Steinbock, PhD Hastings Center Fellow and professor emeritus of philosophy at The University at Albany/State University of New York [email protected]

- Thomas H. Murray, PhD President Emeritus and Fellow, The Hastings Center [email protected]

- Maggie Little, BPhil, PhD Director, The Kennedy Institute of Ethics; Hastings Center Fellow [email protected]

- What Is Bioethics?

- For the Media

- Hastings Center News

- Diversity, Equity, & Inclusion

- Hastings Center Report

- Focus Areas

- Ethics & Human Research

- Bioethics Careers & Education

- Hastings Bioethics Forum

- FAQs on Human Genomics

- Bioethics Briefings

- Books by Hastings Scholars

- Special Reports

- Ways To Give

- Why We Give

- Gift Planning

Upcoming Events

Previous events, receive our newsletter.

- Terms of Use

Greater Good Science Center • Magazine • In Action • In Education

Four Ways Access to Abortion Improves Women’s Well-Being

Last month, the Supreme Court repealed Roe v. Wade , taking away a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion. Already, several states have used that ruling to enact state laws banning abortion. In some cases, receiving an abortion or providing one, even in cases of rape or incest, is a crime punishable by imprisonment or hefty fines.

Though people may argue over whether this ruling is sound or not, it likely spells disaster for women’s health and well-being. That’s because research suggests women who have the right to choose whether or not to give birth are happier, healthier, and more economically stable than those who don’t. And their children benefit, too, by having a mother who can afford to nurture and provide for them better.

How do we know this? Mostly from data coming out of the “ Turnaway Study ”—a long-term, prospective study that followed hundreds of women seeking abortions at different clinics around the country who were either given an abortion or denied one (because of gestation limits for an abortion). By comparing the well-being of these women—who except for receiving an abortion or not were very similar to one another—researchers could more accurately assess the impacts of losing abortion rights.

Here are some of the findings from that important study (and others) about the benefits of receiving an abortion when you want one.

1. Better mental health

Many women are made to feel guilty about seeking an abortion; at times, the circumstances surrounding their choice can involve stress and negative emotions. Does getting the abortion hurt their mental health? Not in most cases. In general, women who get a desired abortion tend to have better mental health—even in the short term—than their peers who are denied one.

In one study , researchers compared women who received an abortion to those who were turned away and found that they had less anxiety, higher self-esteem, and greater life satisfaction one week post-abortion. As time went on, the two groups converged and both fared similarly in terms of their psychological well-being. But it’s clear that getting an abortion had no ill effects, and provided some short-term advantages, for a woman’s mental health.

In another study , researchers looked at the psychological well-being of first-time parents and found no evidence that having had an abortion negatively impacted a woman’s mental health or that it affected her sense of efficacy in raising her children. On the other hand, women who gave birth to an unwanted child (before Roe v. Wade allowed women to have legal abortions) were shown to be more depressed in middle age than women who’d had a wanted childbirth, planned or otherwise.

Of course, that’s not to say that women never suffer emotionally when having an abortion. Someone who really wants to be a mother, but is making the decision to end her pregnancy for economic or health reasons, would likely feel grief.

However, the research to date shows that there is no inherent psychological downside of getting an abortion if you want one—while the opposite may be true for being denied one. That is why the American Psychological Association issued a statement against the court’s ruling.

2. Better physical health

While some have argued that abortions have health risks, those pale in comparison to giving birth. Legal, medically supervised abortions are relatively safe for women. If we don’t keep them that way, women may seek to abort unwanted pregnancies on their own, putting themselves at greater risk for health complications.

One study found that women who wanted an abortion and were able to get one had better overall health five years later than a comparison group of women who were denied an abortion. About 20% of them reported that their health was only fair or poor compared to 27% of women giving birth, and they had fewer chronic headaches, migraines, and joint pain, too. As demographers estimate , a ban on abortions will likely have dire consequences for a large number of women, with the poor and less educated suffering most.

3. More economic stability and less poverty

The two most common reasons women choose to get an abortion are economic instability (they can’t afford to care for a child right now) and poor timing (it might interfere with their educational or career goals). Given that, it makes sense that women who can get an abortion may have better incomes and more stability in their lives. Research bears this out.

As one study showed, having a child later in adulthood substantially increases earned wages for women, especially if they’re college-educated. But the ability of a woman to choose to delay motherhood is affected by whether or not she can obtain an abortion if she wants one, obviously—which suggests that women who have access to abortions also have an economic advantage.

Greater Good Resources for Women’s Well-Being

Articles that aim to help women take care of themselves and each other, make a living, raise children, and work for equality.

The negative effects of not having reproductive freedom were supported by a study published by the National Bureau of Economic Research. In the study, researchers found that “women who were denied an abortion experience a large increase in financial distress that is sustained for several years.” Some of the economic fallout of being denied an abortion included an increased risk of lingering debt, evictions, bankruptcies, and poor credit ratings.

This means women who received an abortion fared better economically and were better able to stay out of poverty, not only helping themselves, but their other children , as well.

4. Women with access to abortions have healthier children

When a woman has access to an abortion for an unwanted pregnancy, she is better able to care for the other children she has (or eventually has).

In one study published in JAMA Pediatrics , researchers compared babies born to a woman denied an abortion (called an “index” baby) to babies born to a woman after she was able to procure an abortion for an earlier pregnancy (“subsequent” babies). Findings showed that mothers were less able to bond with index children than with subsequent children.

In addition, studies found that the existing children of a woman seeking an abortion fared better developmentally six months to 4.5 years later if the woman was given (versus denied) an abortion. This means that the children living with a less-stressed mother demonstrated some combination of better fine motor, gross motor, receptive language, expressive language, self-soothing, and social-emotional skills than children born to a woman denied an abortion. The children were also less likely to live below the poverty line.

Of course, some of these benefits of having access to abortion would be even more pronounced if we lived in a country where there was support for a woman’s right to choose their own reproductive destiny. When countries have better access to abortion, maternal deaths decline , which certainly benefits those women’s children, while abortion rates do not change much (or may even be higher) if abortion is illegal.

If the United States truly wants to protect women and their children, research suggests that they should look to countries whose governments provide universal social welfare programs that benefit families—things like free, widely available prenatal care, health care, parental leave, and child care for working mothers, regardless of their ability to pay. If we had similar policies here, it might not only help those children who are wanted, but also help those who aren’t.

About the Author

Jill Suttie

Jill Suttie, Psy.D. , is Greater Good ’s former book review editor and now serves as a staff writer and contributing editor for the magazine. She received her doctorate of psychology from the University of San Francisco in 1998 and was a psychologist in private practice before coming to Greater Good .

You May Also Enjoy

Working Parents Are Angry. But What Can We Do?

How to Address Gender Inequality in Health Care

Which Workplace Policies Help Parents the Most?

How Women Can Use Their Anger for Good

Greater Good Resources for Women’s Well-Being

What We Can Learn About Happiness from Iceland

Can you explain what "pro-choice" and "pro-life" means?

May 2, 2024 2 min read

By Holly @ Planned Parenthood

Someone asked us: Can you explain what pro-choice means and pro-life means? When my family talks about abortion I think they’re saying “pro-choice” and “pro-life” wrong, but I’m not sure.

Many years ago, "pro-life" and "pro-choice" were terms people came up with to describe themselves as being against abortion access and for abortion access. And you may hear these outdated labels still used today. But neither accurately describes those who oppose abortion, or people who believe that decisions about abortion should be made by the person who is actually pregnant — not the government.

Generally, people who identified as “pro-choice” believed that people have the right to control their own bodies, and everyone should be able to decide when and whether to have children.

People who want abortion to be illegal and inaccessible are often called “pro-life.” The truth is, a majority of Americans believe abortion should be legal and accessible, and that politicians shouldn’t make other people’s personal health care decisions. There are plenty of people in that majority who feel abortion wouldn’t be the right decision for them personally, but do not want to stop others from making a different decision.

“Pro-choice” and “pro-life” labels don’t reflect the complexity of how most people actually think and feel about abortion. Some people and organizations, including Planned Parenthood, don’t use these terms anymore.

Planned Parenthood believes that decisions about whether to choose adoption, end a pregnancy, or parent should be made by a pregnant person with the counsel of their family, their faith, and their nurse or doctor. Politicians should not be involved in anyone’s personal medical decisions about their reproductive health or pregnancy.

Tags: Abortion , Reproductive Rights , anti choice , pro-choice , pro-life

Explore more on

This website uses cookies.

Planned Parenthood cares about your data privacy. We and our third-party vendors use cookies and other tools to collect, store, monitor, and analyze information about your interaction with our site to improve performance, analyze your use of our sites and assist in our marketing efforts. You may opt out of the use of these cookies and other tools at any time by visiting Cookie Settings . By clicking “Allow All Cookies” you consent to our collection and use of such data, and our Terms of Use . For more information, see our Privacy Notice .

Cookie Settings

Planned Parenthood cares about your data privacy. We and our third-party vendors, use cookies, pixels, and other tracking technologies to collect, store, monitor, and process certain information about you when you access and use our services, read our emails, or otherwise engage with us. The information collected might relate to you, your preferences, or your device. We use that information to make the site work, analyze performance and traffic on our website, to provide a more personalized web experience, and assist in our marketing efforts. We also share information with our social media, advertising, and analytics partners. You can change your default settings according to your preference. You cannot opt-out of required cookies when utilizing our site; this includes necessary cookies that help our site to function (such as remembering your cookie preference settings). For more information, please see our Privacy Notice .

We use online advertising to promote our mission and help constituents find our services. Marketing pixels help us measure the success of our campaigns.

Performance

We use qualitative data, including session replay, to learn about your user experience and improve our products and services.

We use web analytics to help us understand user engagement with our website, trends, and overall reach of our products.

Fact sheets

- Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Observatory

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

Ask the expert: 10 questions on safe abortion care

How safe is abortion?