- Columbia University in the City of New York

- Office of Teaching, Learning, and Innovation

- University Policies

- Columbia Online

- Academic Calendar

- Resources and Technology

- Instructional Technologies

- Teaching in All Modalities

Designing Assignments for Learning

The rapid shift to remote teaching and learning meant that many instructors reimagined their assessment practices. Whether adapting existing assignments or creatively designing new opportunities for their students to learn, instructors focused on helping students make meaning and demonstrate their learning outside of the traditional, face-to-face classroom setting. This resource distills the elements of assignment design that are important to carry forward as we continue to seek better ways of assessing learning and build on our innovative assignment designs.

On this page:

Rethinking traditional tests, quizzes, and exams.

- Examples from the Columbia University Classroom

- Tips for Designing Assignments for Learning

Reflect On Your Assignment Design

Connect with the ctl.

- Resources and References

Cite this resource: Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2021). Designing Assignments for Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved [today’s date] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/teaching-with-technology/teaching-online/designing-assignments/

Traditional assessments tend to reveal whether students can recognize, recall, or replicate what was learned out of context, and tend to focus on students providing correct responses (Wiggins, 1990). In contrast, authentic assignments, which are course assessments, engage students in higher order thinking, as they grapple with real or simulated challenges that help them prepare for their professional lives, and draw on the course knowledge learned and the skills acquired to create justifiable answers, performances or products (Wiggins, 1990). An authentic assessment provides opportunities for students to practice, consult resources, learn from feedback, and refine their performances and products accordingly (Wiggins 1990, 1998, 2014).

Authentic assignments ask students to “do” the subject with an audience in mind and apply their learning in a new situation. Examples of authentic assignments include asking students to:

- Write for a real audience (e.g., a memo, a policy brief, letter to the editor, a grant proposal, reports, building a website) and/or publication;

- Solve problem sets that have real world application;

- Design projects that address a real world problem;

- Engage in a community-partnered research project;

- Create an exhibit, performance, or conference presentation ;

- Compile and reflect on their work through a portfolio/e-portfolio.

Noteworthy elements of authentic designs are that instructors scaffold the assignment, and play an active role in preparing students for the tasks assigned, while students are intentionally asked to reflect on the process and product of their work thus building their metacognitive skills (Herrington and Oliver, 2000; Ashford-Rowe, Herrington and Brown, 2013; Frey, Schmitt, and Allen, 2012).

It’s worth noting here that authentic assessments can initially be time consuming to design, implement, and grade. They are critiqued for being challenging to use across course contexts and for grading reliability issues (Maclellan, 2004). Despite these challenges, authentic assessments are recognized as beneficial to student learning (Svinicki, 2004) as they are learner-centered (Weimer, 2013), promote academic integrity (McLaughlin, L. and Ricevuto, 2021; Sotiriadou et al., 2019; Schroeder, 2021) and motivate students to learn (Ambrose et al., 2010). The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning is always available to consult with faculty who are considering authentic assessment designs and to discuss challenges and affordances.

Examples from the Columbia University Classroom

Columbia instructors have experimented with alternative ways of assessing student learning from oral exams to technology-enhanced assignments. Below are a few examples of authentic assignments in various teaching contexts across Columbia University.

- E-portfolios: Statia Cook shares her experiences with an ePorfolio assignment in her co-taught Frontiers of Science course (a submission to the Voices of Hybrid and Online Teaching and Learning initiative); CUIMC use of ePortfolios ;

- Case studies: Columbia instructors have engaged their students in authentic ways through case studies drawing on the Case Consortium at Columbia University. Read and watch a faculty spotlight to learn how Professor Mary Ann Price uses the case method to place pre-med students in real-life scenarios;

- Simulations: students at CUIMC engage in simulations to develop their professional skills in The Mary & Michael Jaharis Simulation Center in the Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and the Helene Fuld Health Trust Simulation Center in the Columbia School of Nursing;

- Experiential learning: instructors have drawn on New York City as a learning laboratory such as Barnard’s NYC as Lab webpage which highlights courses that engage students in NYC;

- Design projects that address real world problems: Yevgeniy Yesilevskiy on the Engineering design projects completed using lab kits during remote learning. Watch Dr. Yesilevskiy talk about his teaching and read the Columbia News article .

- Writing assignments: Lia Marshall and her teaching associate Aparna Balasundaram reflect on their “non-disposable or renewable assignments” to prepare social work students for their professional lives as they write for a real audience; and Hannah Weaver spoke about a sandbox assignment used in her Core Literature Humanities course at the 2021 Celebration of Teaching and Learning Symposium . Watch Dr. Weaver share her experiences.

Tips for Designing Assignments for Learning

While designing an effective authentic assignment may seem like a daunting task, the following tips can be used as a starting point. See the Resources section for frameworks and tools that may be useful in this effort.

Align the assignment with your course learning objectives

Identify the kind of thinking that is important in your course, the knowledge students will apply, and the skills they will practice using through the assignment. What kind of thinking will students be asked to do for the assignment? What will students learn by completing this assignment? How will the assignment help students achieve the desired course learning outcomes? For more information on course learning objectives, see the CTL’s Course Design Essentials self-paced course and watch the video on Articulating Learning Objectives .

Identify an authentic meaning-making task

For meaning-making to occur, students need to understand the relevance of the assignment to the course and beyond (Ambrose et al., 2010). To Bean (2011) a “meaning-making” or “meaning-constructing” task has two dimensions: 1) it presents students with an authentic disciplinary problem or asks students to formulate their own problems, both of which engage them in active critical thinking, and 2) the problem is placed in “a context that gives students a role or purpose, a targeted audience, and a genre.” (Bean, 2011: 97-98).

An authentic task gives students a realistic challenge to grapple with, a role to take on that allows them to “rehearse for the complex ambiguities” of life, provides resources and supports to draw on, and requires students to justify their work and the process they used to inform their solution (Wiggins, 1990). Note that if students find an assignment interesting or relevant, they will see value in completing it.

Consider the kind of activities in the real world that use the knowledge and skills that are the focus of your course. How is this knowledge and these skills applied to answer real-world questions to solve real-world problems? (Herrington et al., 2010: 22). What do professionals or academics in your discipline do on a regular basis? What does it mean to think like a biologist, statistician, historian, social scientist? How might your assignment ask students to draw on current events, issues, or problems that relate to the course and are of interest to them? How might your assignment tap into student motivation and engage them in the kinds of thinking they can apply to better understand the world around them? (Ambrose et al., 2010).

Determine the evaluation criteria and create a rubric

To ensure equitable and consistent grading of assignments across students, make transparent the criteria you will use to evaluate student work. The criteria should focus on the knowledge and skills that are central to the assignment. Build on the criteria identified, create a rubric that makes explicit the expectations of deliverables and share this rubric with your students so they can use it as they work on the assignment. For more information on rubrics, see the CTL’s resource Incorporating Rubrics into Your Grading and Feedback Practices , and explore the Association of American Colleges & Universities VALUE Rubrics (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education).

Build in metacognition

Ask students to reflect on what and how they learned from the assignment. Help students uncover personal relevance of the assignment, find intrinsic value in their work, and deepen their motivation by asking them to reflect on their process and their assignment deliverable. Sample prompts might include: what did you learn from this assignment? How might you draw on the knowledge and skills you used on this assignment in the future? See Ambrose et al., 2010 for more strategies that support motivation and the CTL’s resource on Metacognition ).

Provide students with opportunities to practice

Design your assignment to be a learning experience and prepare students for success on the assignment. If students can reasonably expect to be successful on an assignment when they put in the required effort ,with the support and guidance of the instructor, they are more likely to engage in the behaviors necessary for learning (Ambrose et al., 2010). Ensure student success by actively teaching the knowledge and skills of the course (e.g., how to problem solve, how to write for a particular audience), modeling the desired thinking, and creating learning activities that build up to a graded assignment. Provide opportunities for students to practice using the knowledge and skills they will need for the assignment, whether through low-stakes in-class activities or homework activities that include opportunities to receive and incorporate formative feedback. For more information on providing feedback, see the CTL resource Feedback for Learning .

Communicate about the assignment

Share the purpose, task, audience, expectations, and criteria for the assignment. Students may have expectations about assessments and how they will be graded that is informed by their prior experiences completing high-stakes assessments, so be transparent. Tell your students why you are asking them to do this assignment, what skills they will be using, how it aligns with the course learning outcomes, and why it is relevant to their learning and their professional lives (i.e., how practitioners / professionals use the knowledge and skills in your course in real world contexts and for what purposes). Finally, verify that students understand what they need to do to complete the assignment. This can be done by asking students to respond to poll questions about different parts of the assignment, a “scavenger hunt” of the assignment instructions–giving students questions to answer about the assignment and having them work in small groups to answer the questions, or by having students share back what they think is expected of them.

Plan to iterate and to keep the focus on learning

Draw on multiple sources of data to help make decisions about what changes are needed to the assignment, the assignment instructions, and/or rubric to ensure that it contributes to student learning. Explore assignment performance data. As Deandra Little reminds us: “a really good assignment, which is a really good assessment, also teaches you something or tells the instructor something. As much as it tells you what students are learning, it’s also telling you what they aren’t learning.” ( Teaching in Higher Ed podcast episode 337 ). Assignment bottlenecks–where students get stuck or struggle–can be good indicators that students need further support or opportunities to practice prior to completing an assignment. This awareness can inform teaching decisions.

Triangulate the performance data by collecting student feedback, and noting your own reflections about what worked well and what did not. Revise the assignment instructions, rubric, and teaching practices accordingly. Consider how you might better align your assignment with your course objectives and/or provide more opportunities for students to practice using the knowledge and skills that they will rely on for the assignment. Additionally, keep in mind societal, disciplinary, and technological changes as you tweak your assignments for future use.

Now is a great time to reflect on your practices and experiences with assignment design and think critically about your approach. Take a closer look at an existing assignment. Questions to consider include: What is this assignment meant to do? What purpose does it serve? Why do you ask students to do this assignment? How are they prepared to complete the assignment? Does the assignment assess the kind of learning that you really want? What would help students learn from this assignment?

Using the tips in the previous section: How can the assignment be tweaked to be more authentic and meaningful to students?

As you plan forward for post-pandemic teaching and reflect on your practices and reimagine your course design, you may find the following CTL resources helpful: Reflecting On Your Experiences with Remote Teaching , Transition to In-Person Teaching , and Course Design Support .

The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL) is here to help!

For assistance with assignment design, rubric design, or any other teaching and learning need, please request a consultation by emailing [email protected] .

Transparency in Learning and Teaching (TILT) framework for assignments. The TILT Examples and Resources page ( https://tilthighered.com/tiltexamplesandresources ) includes example assignments from across disciplines, as well as a transparent assignment template and a checklist for designing transparent assignments . Each emphasizes the importance of articulating to students the purpose of the assignment or activity, the what and how of the task, and specifying the criteria that will be used to assess students.

Association of American Colleges & Universities (AAC&U) offers VALUE ADD (Assignment Design and Diagnostic) tools ( https://www.aacu.org/value-add-tools ) to help with the creation of clear and effective assignments that align with the desired learning outcomes and associated VALUE rubrics (Valid Assessment of Learning in Undergraduate Education). VALUE ADD encourages instructors to explicitly state assignment information such as the purpose of the assignment, what skills students will be using, how it aligns with course learning outcomes, the assignment type, the audience and context for the assignment, clear evaluation criteria, desired formatting, and expectations for completion whether individual or in a group.

Villarroel et al. (2017) propose a blueprint for building authentic assessments which includes four steps: 1) consider the workplace context, 2) design the authentic assessment; 3) learn and apply standards for judgement; and 4) give feedback.

References

Ambrose, S. A., Bridges, M. W., & DiPietro, M. (2010). Chapter 3: What Factors Motivate Students to Learn? In How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching . Jossey-Bass.

Ashford-Rowe, K., Herrington, J., and Brown, C. (2013). Establishing the critical elements that determine authentic assessment. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 39(2), 205-222, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2013.819566 .

Bean, J.C. (2011). Engaging Ideas: The Professor’s Guide to Integrating Writing, Critical Thinking, and Active Learning in the Classroom . Second Edition. Jossey-Bass.

Frey, B. B, Schmitt, V. L., and Allen, J. P. (2012). Defining Authentic Classroom Assessment. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. 17(2). DOI: https://doi.org/10.7275/sxbs-0829

Herrington, J., Reeves, T. C., and Oliver, R. (2010). A Guide to Authentic e-Learning . Routledge.

Herrington, J. and Oliver, R. (2000). An instructional design framework for authentic learning environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 48(3), 23-48.

Litchfield, B. C. and Dempsey, J. V. (2015). Authentic Assessment of Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 142 (Summer 2015), 65-80.

Maclellan, E. (2004). How convincing is alternative assessment for use in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 29(3), June 2004. DOI: 10.1080/0260293042000188267

McLaughlin, L. and Ricevuto, J. (2021). Assessments in a Virtual Environment: You Won’t Need that Lockdown Browser! Faculty Focus. June 2, 2021.

Mueller, J. (2005). The Authentic Assessment Toolbox: Enhancing Student Learning through Online Faculty Development . MERLOT Journal of Online Learning and Teaching. 1(1). July 2005. Mueller’s Authentic Assessment Toolbox is available online.

Schroeder, R. (2021). Vaccinate Against Cheating With Authentic Assessment . Inside Higher Ed. (February 26, 2021).

Sotiriadou, P., Logan, D., Daly, A., and Guest, R. (2019). The role of authentic assessment to preserve academic integrity and promote skills development and employability. Studies in Higher Education. 45(111), 2132-2148. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1582015

Stachowiak, B. (Host). (November 25, 2020). Authentic Assignments with Deandra Little. (Episode 337). In Teaching in Higher Ed . https://teachinginhighered.com/podcast/authentic-assignments/

Svinicki, M. D. (2004). Authentic Assessment: Testing in Reality. New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 100 (Winter 2004): 23-29.

Villarroel, V., Bloxham, S, Bruna, D., Bruna, C., and Herrera-Seda, C. (2017). Authentic assessment: creating a blueprint for course design. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education. 43(5), 840-854. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2017.1412396

Weimer, M. (2013). Learner-Centered Teaching: Five Key Changes to Practice . Second Edition. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Wiggins, G. (2014). Authenticity in assessment, (re-)defined and explained. Retrieved from https://grantwiggins.wordpress.com/2014/01/26/authenticity-in-assessment-re-defined-and-explained/

Wiggins, G. (1998). Teaching to the (Authentic) Test. Educational Leadership . April 1989. 41-47.

Wiggins, Grant (1990). The Case for Authentic Assessment . Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation , 2(2).

Wondering how AI tools might play a role in your course assignments?

See the CTL’s resource “Considerations for AI Tools in the Classroom.”

This website uses cookies to identify users, improve the user experience and requires cookies to work. By continuing to use this website, you consent to Columbia University's use of cookies and similar technologies, in accordance with the Columbia University Website Cookie Notice .

Transparent Assignment Design

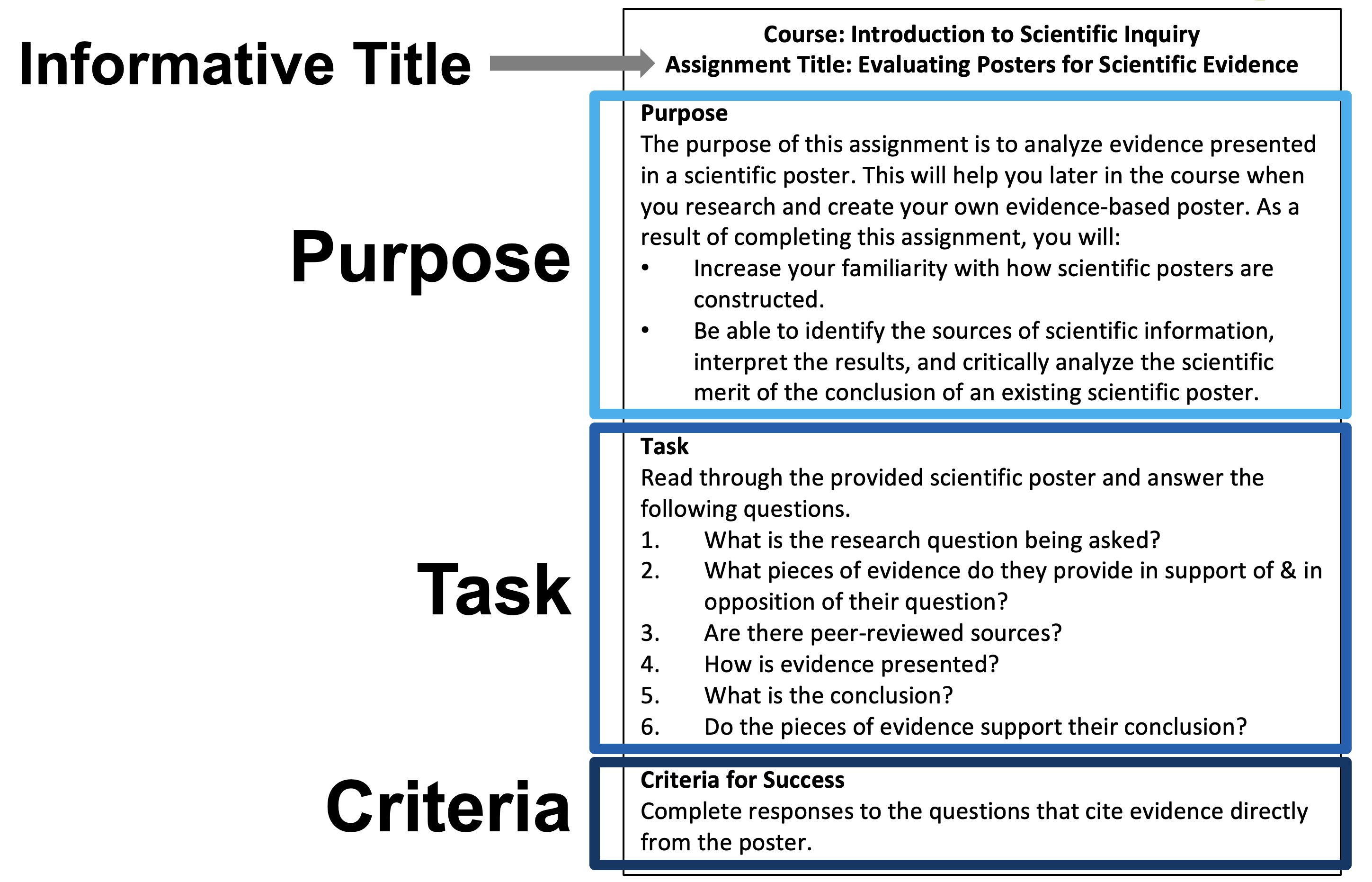

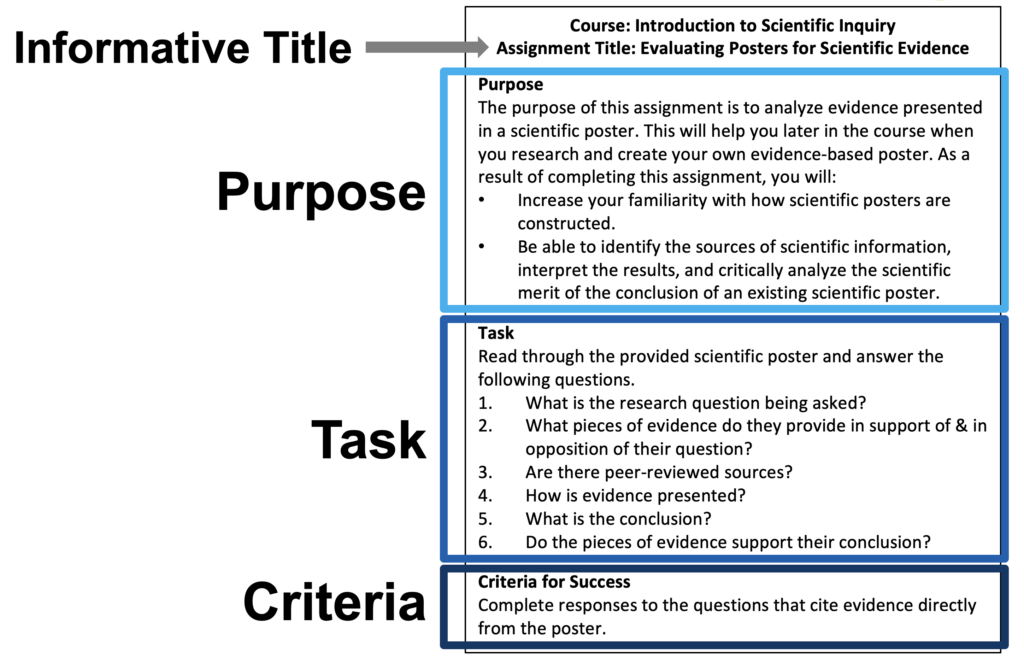

When we communicate how and why students are learning course content in certain ways, we are being transparent about the methods we use for teaching and learning. The goal of Transparent Assignment Design is to “to make learning processes explicit and equally accessible for all students” (Winkelmes et al., 2019, p. 1). This involves sharing three critical pieces of information with students:

Purpose : Describe why students are completing an assignment and what knowledge and skills they will gain from this experience. Additionally, explain how this knowledge and skill set are relevant and will help the students in the future.

Task : Explain the steps students will take to complete the assignment.

Criteria and Examples : Show the students what successful submissions look like (e.g., provide a checklist or rubric and real-world examples).

The figure below illustrates an example of an assignment that has incorporated Transparent Assignment Design.

Additional examples in a variety of disciplines can be found on the TILT Higher Ed website.

Providing a full picture of a specific assignment, complete with the purpose, task, and criteria and examples, can equip students to do their best work. Research shows that Transparent Assignment Design benefits learning for all students, but it is especially beneficial to students in traditionally underrepresented groups, such as those who are non-white, low-income, first-generation, or struggling with general college success. In a 2014-2016 Association of American Colleges & Universities study, students self-reported an increase in academic confidence, sense of belonging, and acquisition of employer-valued skills in courses that were considered more transparent (Winkelmes et al., 2016).

CATLR Tips:

- Start with an informative title! The title should give students a preview of the purpose of the assignment. For example, an assignment title such as “Scientific Evidence” can be renamed “Evaluating Posters for Scientific Evidence.”

- Indicate the due date (date and time, including time zone) and how the students should submit (e.g., through the Assignments section on Canvas).

- Prior to distributing an assignment to students, ask a colleague to review it. Specifically, ask if they can identify the purpose, task, and criteria.

- Provide multiple examples that illustrate successful submissions in order to avoid students thinking there is one “correct” way to complete the assignment.

References:

Transparency in Learning and Teaching (TILT) Higher Ed. (n.d.). TILT higher ed examples and resources. https://tilthighered.com/tiltexamplesandresources

Winkelmes, M. A., Bernacki, M., Butler, J., Zochowski, M., Golanics, J., & Weavil, K. H. (2016). A teaching intervention that increases underserved college students’ success. Peer Review , 18 (1/2), 31-36.

Winkelmes, M. A., Boye, A., & Tapp, S. (2019). Transparent design in higher education teaching and leadership: A guide to implementing the transparency framework institution-wide to improve learning and retention. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

- CTLI Newsletter

- Designing a Course

- Inclusive & Anti-Oppressive Pedagogy

- Building Community

- Active Learning Strategies

- Grading for Growth

- Guides & Templates

- Classroom Technology

- Educational Apps

- Generative AI

- Using Technology Purposefully

- Upcoming Events

- Archive & Recordings

- Book Groups

- Faculty Learning Community

- Thank an Educator Program

- University Resources

- CTLI Consultations

- New VTSU Faculty – Getting Started

- Center for Teaching & Learning Innovation Staff

- Advisory Committee

- Newsletter Archive

- CTLI News Blog

Transparent Assignment Design

The goal of Transparent Assignment Design is to “to make learning processes explicit and equally accessible for all students” (Winkelmes et al., 2019, p. 1). The development of a transparent assignment involves providing students with clarity on the purpose of the assignment, the tasks required, and criteria for success as shown in the figure below. The inclusion of these elements as well as the provision of examples can be beneficial in enabling your students to do their best work!

Example A: Sociology

Example B: Science 101

Example C: Psychology

Example D: Communications

Authors of Examples A-D describe the outcomes of their assignment revisions

Example E: Biology

Discussion Questions (about Examples A-E)

Example F: Library research Assignment

Example G: Criminal Justice In-Class activity

Example H: Criminal Justice Assignment

Example I: Political Science Assignment

Example J: Criteria for Math Writing

Example K – Environmental History

Example L – Calculus

Example M – Algebra

Example N – Finance

Transparent Assignments Promote Equitable Opportunities for Students’ Success Video Recording

Transparent Assignment Design Faculty Workshop Video Recording

- Transparent Assignment Template for instructors (Word Document download)

- Checklist for Designing Transparent Assignments

- Assignment Cues to use when designing an assignment (adapted from Bloom’s Taxonomy) for faculty

- Transparent Equitable Learning Readiness Assessment for Teachers

- Transparent Assignment Template for students (to help students learn to parse assignments also to frame a conversation to gather feedback from your students about how to make assignments more transparent and relevant for them)

- Measuring Transparency: A Learning-focused Assignment Rubric (Palmer, M., Gravett, E., LaFleur, J.)

- Transparent Equitable Learning Framework for Students (to frame a conversation with students about how to make the purposes, tasks and criteria for class activities transparent and relevant for them)

- Howard, Tiffiany, Mary-Ann Winkelmes, and Marya Shegog. “ Transparency Teaching in the Virtual Classroom: Assessing the Opportunities and Challenges of Integrating Transparency Teaching Methods with Online Learning.” Journal of Political Science Education, June 2019.

- Ou, J. (2018, June), Board 75 : Work in Progress: A Study of Transparent Assignments and Their Impact on Students in an Introductory Circuit Course Paper presented at 2018 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition , Salt Lake City, Utah.

- Palmer, M. S., Gravett, E. O., & LaFleur, J. (2018). Measuring transparency: A learning‐focused assignment rubric. To Improve the Academy, 37(2), 173-187. doi:10.1002/tia2.20083

- Winkelmes, M., Allison Boye and Suzanne Tapp, ed.s. (2019). Transparent Design in Higher Education Teaching and Leadership. Stylus Publishing.

- Humphreys, K., Winkelmes, M.A., Gianoutsos, D., Mendenhall, A., Fields, L.A., Farrar, E., Bowles-Terry, M., Juneau-Butler, G., Sully, G., Gittens, S. Cheek, D. (forthcoming 2018). Campus-wide Collaboration on Transparency in Faculty Development at a Minority-Serving Research University. In Winkelmes, Boye, Tapp, (Eds.), Transparent Design in Higher Education Teaching and Leadership.

- Copeland, D.E., Winkelmes, M., & Gunawan, K. (2018). Helping students by using transparent writing assignments. In T.L. Kuther (Ed.), Integrating Writing into the College Classroom: Strategies for Promoting Student Skills, 26-37. Retrieved from the Society for the Teaching of Psychology website.

- Winkelmes, Mary-Ann, Matthew Bernacki, Jeffrey Butler, Michelle Zochowski, Jennifer Golanics, and Kathryn Harriss Weavil. “A Teaching Intervention that Increases Underserved College Students’ Success.”Peer Review (Winter/Spring 2016).

- Transparency and Problem-Centered Learning. (Winter/Spring 2016) Peer Review vol.18, no. 1/2.b

- Winkelmes, Mary-Ann. Small Teaching Changes, Big Learning Benefits.” ACUE Community ‘Q’ Blog, December, 2016.

- Winkelmes, Mary-Ann. “Helping Faculty Use Assessment Data to Provide More Equitable Learning Experiences.” NILOA Guest Viewpoints. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois and Indiana University, National Institute for Learning Outcomes Assessment, March 17, 2016.

- Gianoutsos, Daniel, and Mary-Ann Winkelmes.“Navigating with Transparency: Enhancing Underserved Student Success through Transparent Learning and Teaching in the Classroom and Beyond.” Proceedings of the Pennsylvania Association of Developmental Educators (Spring 2016).

- Sodoma, Brian.“The End of Busy Work.” UNLV Magazine 24,1 (Spring 2016): 16-19.

- Cook, Lisa and Daniel Fusch. One Easy Way Faculty Can Improve Student Success.” Academic Impressions (March 10, 2016).

- Head, Alison and Kirsten Hosteller. “Mary-Ann Winkelmes: Transparency in Teaching and Learning,” Project Information Literacy, Smart Talk Interview, no. 25. Creative Commons License 3.0 : 2 September 2015.

- Winkelmes, Mary-Ann, et al. David E. Copeland, Ed Jorgensen, Alison Sloat, Anna Smedley, Peter Pizor, Katharine Johnson, and Sharon Jalene. “Benefits (some unexpected) of Transparent Assignment Design.” National Teaching and Learning Forum, 24, 4 (May 2015), 4-6.

- Winkelmes, Mary-Ann. “Equity of Access and Equity of Experience in Higher Education.” National Teaching and Learning Forum, 24, 2 (February 2015), 1-4.

- Cohen, Dov, Emily Kim, Jacinth Tan, Mary-Ann Winkelmes, “A Note-Restructuring Intervention Increases Students’ Exam Scores.” College Teaching vol. 61, no. 3 (2013): 95-99.

- Winkelmes, Mary-Ann.”Transparency in Teaching: Faculty Share Data and Improve Students’ Learning.” Liberal Education Association of American Colleges and Universities (Spring 2013).

- Winkelmes, Mary-Ann. “Transparency in Learning and Teaching: Faculty and students benefit directly from a shared focus on learning and teaching processes.” NEA Higher Education Advocate (January 2013): 6 – 9.

- Bhavsar, Victoria Mundy. (2020). A Transparent Assignment to Encourage Reading for a Flipped Course, College Teaching, 68:1, 33-44, DOI: 10.1080/87567555.2019.1696740

- Bowles-Terry, Melissa, John C. Watts, Pat Hawthorne, and Patricia Iannuzzi. “ Collaborating with Teaching Faculty on Transparent Assignment Design .” In Creative Instructional Design: Practical Applications for Librarians, edited by Brandon K. West, Kimberly D. Hoffman, and Michelle Costello, 291–311. Atlanta: American Library Association, 2017.

- Leuzinger, Ryne and Grallo, Jacqui, “ Reaching First- Generation and Underrepresented Students through Transparent Assignment Design .” (2019). Library Faculty Publications and Presentations. 11. https://digitalcommons.csumb.edu/lib_fac/11

- Fuchs, Beth, “ Pointing a Telescope Toward the Night Sky: Transparency and Intentionality as Teaching Techniques ” (2018). Library Presentations. 188. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/libraries_present/188

- Ferarri, Franca; Salis, Andreas; Stroumbakis, Kostas; Traver, Amy; and Zhelecheva, Tanya, “ Transparent Problem-Based Learning Across the Disciplines in the Community College Context: Issues and Impacts ” (2015).NERA Conference Proceedings 2015. 9. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/nera-2015/9

- Milman, Natalie B. Tips for Success: The Online Instructor’s (Short) Guide to Making Assignment Descriptions More Transparent . Distance Learning. Greenwich Vol. 15, Iss. 4, (2018): 65-67. 3

- Winkelmes, M. (2023). Introduction to Transparency in Learning and Teaching. Perspectives In Learning, 20 (1). Retrieved from https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/pil/vol20/iss1/2

- Brown, J., et al. (2023). Perspectives in Learning: TILT Special Issue, 20 (1). Retrieved from https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/pil/vol20/iss1/

- Winkelmes, M. (2022). “Assessment in Class Meetings: Transparency Reduces Systemic Inequities.” In Henning, G. W., Jankowski, N. A., Montenegro, E., Baker, G. R., & Lundquist, A. E. (Eds.). (2022). Reframing Assessment to Center Equity: Theories, Models, and Practices. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Citation : TILT Higher Ed © 2009-2023 by Mary-Ann Winkelmes . Retrieved from https://tilthighered.com/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License .

Ohio State nav bar

The Ohio State University

- BuckeyeLink

- Find People

- Search Ohio State

AI Teaching Strategies: Transparent Assignment Design

The rise of generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools like ChatGPT, Google Bard, and Jasper Chat raises many questions about the ways we teach and the ways students learn. While some of these questions concern how we can use AI to accomplish learning goals and whether or not that is advisable, others relate to how we can facilitate critical analysis of AI itself.

The wide variety of questions about AI and the rapidly changing landscape of available tools can make it hard for educators to know where to start when designing an assignment. When confronted with new technologies—and the new teaching challenges they present—we can often turn to existing evidence-based practices for the guidance we seek.

This guide will apply the Transparency in Learning and Teaching (TILT) framework to "un-complicate" planning an assignment that uses AI, providing guiding questions for you to consider along the way.

The result should be an assignment that supports you and your students to approach the use of AI in a more thoughtful, productive, and ethical manner.

Plan your assignment.

The TILT framework offers a straightforward approach to assignment design that has been shown to improve academic confidence and success, sense of belonging, and metacognitive awareness by making the learning process clear to students (Winkelmes et al., 2016). The TILT process centers around deciding—and then communicating—three key components of your assignment: 1) purpose, 2) tasks, and 3) criteria for success.

Step 1: Define your purpose.

To make effective use of any new technology, it is important to reflect on our reasons for incorporating it into our courses. In the first step of TILT, we think about what we want students to gain from an assignment and how we will communicate that purpose to students.

The SAMR model , a useful tool for thinking about educational technology use in our courses, lays out four tiers of technology integration. The tiers, roughly in order of their sophistication and transformative power, are S ubstitution, A ugmentation, M odification, and R edefinition. Each tier may suggest different approaches to consider when integrating AI into teaching and learning activities.

Questions to consider:

- Do you intend to use AI as a substitution, augmentation, modification, or redefinition of an existing teaching practice or educational technology?

- What are your learning goals and expected learning outcomes?

- Do you want students to understand the limitations of AI or to experience its applications in the field?

- Do you want students to reflect on the ethical implications of AI use?

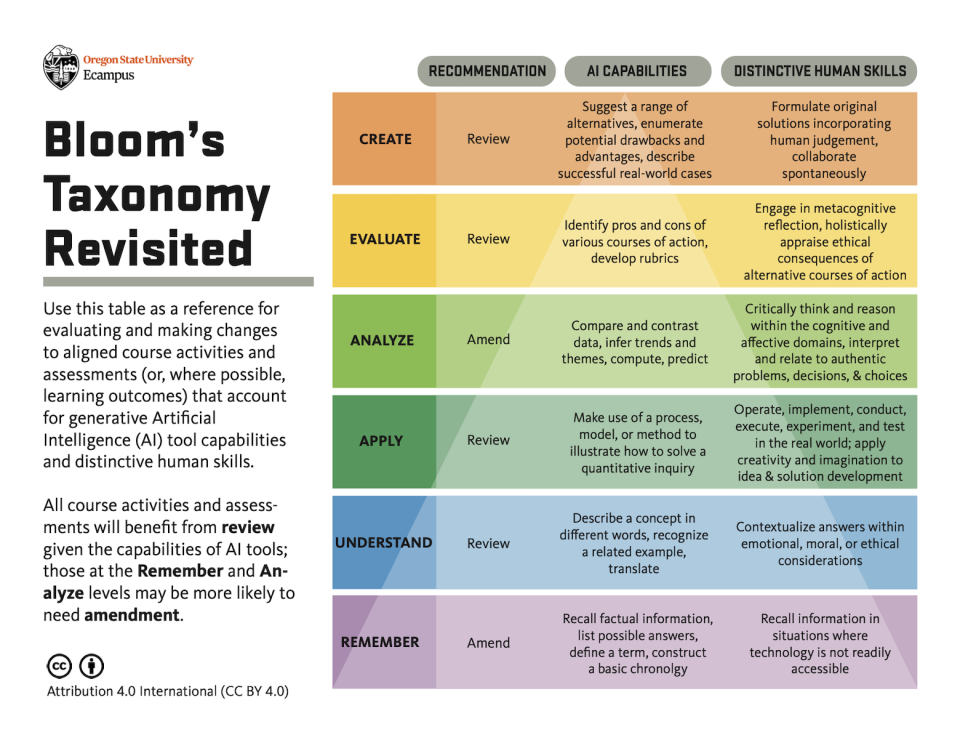

Bloom’s Taxonomy is another useful tool for defining your assignment’s purpose and your learning goals and outcomes.

This downloadable Bloom’s Taxonomy Revisited resource , created by Oregon State University, highlights the differences between AI capabilities and distinctive human skills at each Bloom's level, indicating the types of assignments you should review or change in light of AI. Bloom's Taxonomy Revisited is licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

Access a transcript of the graphic .

Step 2: Define the tasks involved.

In the next step of TILT, you list the steps students will take when completing the assignment. In what order should they do specific tasks, what do they need to be aware of to perform each task well, and what mistakes should they avoid? Outlining each step is especially important if you’re asking students to use generative AI in a limited manner. For example, if you want them to begin with generative AI but then revise, refine, or expand upon its output, make clear which steps should involve their own thinking and work as opposed to AI’s thinking and work.

- Are you designing this assignment as a single, one-time task or as a longitudinal task that builds over time or across curricular and co-curricular contexts? For longitudinal tasks consider the experiential learning cycle (Kolb, 1984) . In Kolb’s cycle, learners have a concrete experience followed by reflective observation, abstract conceptualization, and active experimentation. For example, students could record their generative AI prompts, the results, a reflection on the results, and the next prompt they used to get improved output. In subsequent tasks students could expand upon or revise the AI output into a final product. Requiring students to provide a record of their reflections, prompts, and results can create an “AI audit trail,” making the task and learning more transparent.

- What resources and tools are permitted or required for students to complete the tasks involved with the assignment? Make clear which steps should involve their own thinking (versus AI-generated output, for example), required course materials, and if references are required. Include any ancillary resources students will need to accomplish tasks, such as guidelines on how to cite AI , in APA 7.0 for example.

- How will you offer students flexibility and choice? As of this time, most generative AI tools have not been approved for use by Ohio State, meaning they have not been vetted for security, privacy, or accessibility issues . It is known that many platforms are not compatible with screen readers, and there are outstanding questions as to what these tools do with user data. Students may have understandable apprehensions about using these tools or encounter barriers to doing so successfully. So while there may be value in giving students first-hand experience with using AI, it’s important to give them the choice to opt out. As you outline your assignment tasks, plan how to provide alternative options to complete them. Could you provide AI output you’ve generated for students to work with, demonstrate use of the tool during class, or allow use of another tool that enables students to meet the same learning outcomes.

Microsoft Copilot is currently the only generative AI tool that has been vetted and approved for use at Ohio State. As of February 2024, the Office of Technology and Digital Innovation (OTDI) has enabled it for use by students, faculty, and staff. Copilot is an AI chatbot that draws from public online data, but with additional security measures in place. For example, conversations within the tool aren’t stored. Learn more and stay tuned for further information about Copilot in the classroom.

- What are your expectations for academic integrity? This is a helpful step for clarifying your academic integrity guidelines for this assignment, around AI use specifically as well as for other resources and tools. The standard Academic Integrity Icons in the table below can help you call out what is permissible and what is prohibited. If any steps for completing the assignment require (or expressly prohibit) AI tools, be as clear as possible in highlighting which ones, as well as why and how AI use is (or is not) permitted.

| Permitted | Not permitted | Potential Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| [is] [is ] permitted. | ||

| [is] [is ] permitted. | ||

| [is] [is ] permitted. | ||

| for the assignment [is] [is ] permitted and encouraged. | ||

| on the assignment [is] [is ] permitted. | ||

| for the assignment [is] [is ] permitted. |

Promoting academic integrity

While inappropriate use of AI may constitute academic misconduct, it can be muddy for students to parse out what is permitted or prohibited across their courses and across various use cases. Fortunately, there are existing approaches to supporting academic integrity that apply to AI as well as to any other tool. Discuss academic integrity openly with students, early in the term and before each assignment. Purposefully design your assignments to promote integrity by using real-world formats and audiences, grading the process as well as the product, incorporating personal reflection tasks, and more.

Learn about taking a proactive, rather than punitive, approach to academic integrity in A Positive Approach to Academic Integrity.

Step 3: Define criteria for success.

An important feature of transparent assignments is that they make clear to students how their work will be evaluated. During this TILT step, you will define criteria for a successful submission—consider creating a rubric to clarify these expectations for students and simplify your grading process. If you intend to use AI as a substitute or augmentation for another technology, you might be able to use an existing rubric with little or no change. However, if AI use is modifying or redefining the assignment tasks, a new grading rubric will likely be needed.

- How will you grade this assignment? What key criteria will you assess?

- What indicators will show each criterion has been met?

- What qualities distinguish a successful submission from one that needs improvement?

- Will you grade students on the product only or on aspects of the process as well? For example, if you have included a reflection task as part of the assignment, you might include that as a component of the final grade.

Alongside your rubric, it is helpful to prepare examples of successful (and even unsuccessful) submissions to provide more tangible guidance to students. In addition to samples of the final product, you could share examples of effective AI prompts, reflections tasks, and AI citations. Examples may be drawn from previous student work or models that you have mocked up, and they can be annotated to highlight notable elements related to assignment criteria.

Present and discuss your assignment.

As clear as we strive to be in our assignment planning and prompts, there may be gaps or confusing elements we have overlooked. Explicitly going over your assignment instructions—including the purpose, key tasks, and criteria—will ensure students are equipped with the background and knowledge they need to perform well. These discussions also offer space for students to ask questions and air unanticipated concerns, which is particularly important given the potential hesitance some may have around using AI tools.

- How will this assignment help students learn key course content, contribute to the development of important skills such as critical thinking, or support them to meet your learning goals and outcomes?

- How might students apply the knowledge and skills acquired in their future coursework or careers?

- In what ways will the assignment further students’ understanding and experience around generative AI tools, and why does that matter?

- What questions or barriers do you anticipate students might encounter when using AI for this assignment?

As noted above, many students are unaware of the accessibility, security, privacy, and copyright concerns associated with AI, or of other pitfalls they might encounter working with AI tools. Openly discussing AI’s limitations and the inaccuracies and biases it can create and replicate will support students to anticipate barriers to success on the assignment, increase their digital literacy, and make them more informed and discerning users of technology.

Explore available resources It can feel daunting to know where to look for AI-related assignment ideas, or who to consult if you have questions. Though generative AI is still on the rise, a growing number of useful resources are being developed across the teaching and learning community. Consult our other Teaching Topics, including AI Considerations for Teaching and Learning , and explore other recommended resources such as the Learning with AI Toolkit and Exploring AI Pedagogy: A Community Collection of Teaching Reflections.

If you need further support to review or develop assignment or course plans in light of AI, visit our Help forms to request a teaching consultation .

Using the Transparent Assignment Template

Sample assignment: ai-generated lesson plan.

In many respects, the rise of generative AI has reinforced existing best practices for assignment design—craft a clear and detailed assignment prompt, articulate academic integrity expectations, increase engagement and motivation through authentic and inclusive assessments. But AI has also encouraged us to think differently about how we approach the tasks we ask students to undertake, and how we can better support them through that process. While it can feel daunting to re-envision or reformat our assignments, AI presents us with opportunities to cultivate the types of learning and growth we value, to help students see that value, and to grow their critical thinking and digital literacy skills.

Using the Transparency in Learning and Teaching (TILT) framework to plan assignments that involve generative AI can help you clarify expectations for students and take a more intentional, productive, and ethical approach to AI use in your course.

- Step 1: Define your purpose. Think about what you want students to gain from this assignment. What are your learning goals and outcomes? Do you want students to understand the limitations of AI, see its applications in your field, or reflect on its ethical implications? The SAMR model and Bloom's Taxonomy are useful references when defining your purpose for using (or not using) AI on an assignment.

- Step 2: Define the tasks involved. L ist the steps students will take to complete the assignment. What resources and tools will they need? How will students reflect upon their learning as they proceed through each task? What are your expectations for academic integrity?

- Step 3: Define criteria for success. Make clear to students your expectations for success on the assignment. Create a rubric to call out key criteria and simplify your grading process. Will you grade the product only, or parts of the process as well? What qualities indicate an effective submission? Consider sharing tangible models or examples of assignment submissions.

Finally, it is time to make your assignment guidelines and expectations transparent to students. Walk through the instructions explicitly—including the purpose, key tasks, and criteria—to ensure they are prepared to perform well.

- Checklist for Designing Transparent Assignments

- TILT Higher Ed Information and Resources

Winkelmes, M. (2013). Transparency in Teaching: Faculty Share Data and Improve Students’ Learning. Liberal Education 99 (2).

Wilkelmes, M. (2013). Transparent Assignment Design Template for Teachers. TiLT Higher Ed: Transparency in Learning and Teaching. https://tilthighered.com/assets/pdffiles/Transparent%20Assignment%20Templates.pdf

Winkelmes, M., Bernacki, M., Butler, J., Zochowski, M., Golanics, J., Weavil, K. (2016). A Teaching Intervention that Increases Underserved College Students’ Success. Peer Review.

Related Teaching Topics

Ai considerations for teaching and learning, ai teaching strategies: having conversations with students, designing assessments of student learning, search for resources.

- Join Our Listserv

- Request a Consult

- Search Penn's Online Offerings

- Assignment Design: Is AI In or Out?

Generative AI

- Rachel Hoke

This page provides examples for designing AI out of or into your assignments. These ideas are intended to provide a starting point as you consider how assignment design can limit or encourage certain uses of AI to help students learn. CETLI is available to consult with you about ways you might design AI out of or into your assignments.

Considerations for Crafting Assignments

- Connect to your goals. Assignments support the learning goals of your course, and decisions about how students may or may not use AI should be based on these goals.

- Designing ‘in’ doesn’t mean ‘all in’. Incorporating certain uses of AI into an assignment doesn’t mean you have to allow all uses, especially those that would interfere with learning.

- Communicate to students . Think about how you will explain the assignment’s purpose and benefits to your students, including the rationale for your guidelines on AI use.

Design Out: Limit AI Use

Very few assignments are truly AI-proof, but some designs are more resistant to student AI use than others. Along with designing assignments in ways that deter the use of AI, inform students about your course AI policies regarding what is and is not acceptable as well as the potential consequences for violating these terms.

Assignments that ask students to refer to something highly specific to your course or not easily searchable online will make it difficult for AI to generate a response. Examples include asking students to:

- Summarize, discuss, question, or otherwise respond to content from an in-class activity, a specific part of your lecture, or a classmate’s discussion comments.

- Relate course content to issues that have local context or personal relevance. The more recent and specific the topic, the more poorly AI will perform.

- Respond to visual or multimedia material as part of their assignment. AI has difficulty processing non-text information.

Find opportunities for students to present, discuss their work, and respond to questions from others. To field questions live requires students to demonstrate their understanding of the topic, and the skill of talking succinctly about one’s work and research is valuable for students in many disciplines. You might ask students to:

- Create an “elevator pitch” for a research idea and submit it as a short video, then watch and respond to peers’ ideas.

- Give an in-class presentation with Q&A that supplements submitted written work.

- Meet with you or your TA to discuss their ideas and receive constructive feedback before or after completing the assignment.

This strategy allows students to show how they have thought about the work that they’ve done and places value on their awareness of their learning. For instance, students might:

- Briefly write about a source or approach they considered but decided not to use and why.

- Discuss a personal connection they made to the learning material.

- Submit a reflection on how the knowledge or skills gained from the assignment apply to their professional practice.

Consider asking students to show the stages of their work or submit assignments in phases, so you can review the development of their ideas or work over time. Explaining the value of the thinking students will do in taking on the work themselves can help deter students’ dependence on AI. Additionally, this strategy helps keep students on track so they do not fall behind and feel pressure to use AI inappropriately. For materials handed in with the final product, it can give you a way to refer back to their process. You may ask students to:

- Submit an outline, list of sources, discussion of a single piece of data, explanation of their approach, or first draft before the final product.

- Meet briefly with an instructor to discuss their approach or work in progress.

- Submit the notes they have taken on sources to prepare their paper, presentation, or project.

Prior to beginning an exam or submitting an assignment, you may ask students to confirm that they have followed the policies regarding academic integrity and AI. This can be particularly helpful for an assignment with different AI guidelines than others in your course. You might:

- Ask students to affirm a statement that all submitted work is their own.

- Ask students to confirm their understanding of your generative AI policy at the start of the assignment.

If you decide to limit student’s use of AI in their work:

- Communicate the policy early, often and in a variety of ways.

- Be Transparent. Clearly explain the reasoning behind your decision to limit or exclude the use of AI in the assignment, focusing on how the assignment relates to the course’s learning objectives and how the use of AI limits the intended learning outcomes.

Design In: Encourage AI Use

You may find that assignments that draw upon generative AI can help your students develop the thinking and skills that are valuable in your field. Careful planning is important to ensure that the designed use of AI furthers your objectives and benefits students. Become familiar with the tasks that AI does and does not do well, and explore how careful prompting can influence its output. These examples represent only a small fraction of potential uses and aim to provide a starting point for considering assignments you might adapt for your courses.

Consider using AI tools to generate original content for students to analyze. You might ask students to:

- Compare multiple versions of an AI-generated approach to problem-solving based on the same task.

- Analyze case studies generated by AI.

- Determine and implement strategies for fact-checking AI-generated assertions to examine the value of information sources.

Generative AI may support students as they take on more advanced thinking by offering help and feedback in real time. For instance, students can:

- Input a provided prompt that guides AI to act as a tutor on an assignment. Prompts can lead the AI tutor to review material, answer questions, and help students use problem-solving strategies to find a solution.

- Ask AI to support the writing process by having it review an essay and provide feedback with explicit instructions to help identify weaknesses in an argument. Consider asking students to turn in the transcript of their discussion with the AI as part of the assignment.

- Use AI for coaching (guidance) through complex tasks like helping students without coding skills create code to analyze materials when the learning goal is data analysis rather than coding.

To support students in learning how to test their ideas, to understand what is arguable, or to practice voicing ideas with feedback, generative AI can be prompted to participate in a conversation. You might ask students to:

- Instruct AI to respond as someone unfamiliar with the course material and engage in a dialogue explaining a concept to the AI.

- Find common ground in a discussion of a controversial issue by asking AI to take a counterposition in the debate. The student could question the AI’s contradictions or identify oversimplifications while focusing on defining their own position.

- Engage with AI as it role-plays a persona like a stakeholder in a case study or a patient in a clinical conversation.

Students can engage with AI as a thought partner at the start or end stages of a project, without allowing AI to do everything. The parts of the task AI does and the parts students should do will depend on the type of learning you want them to accomplish. You might ask students to:

- Use AI to draft an initial hypothesis. Then, the student gathers, synthesizes, and cites evidence that supports or refutes the argument. Finally, the student submits the original AI output along with their finished product.

- Brainstorm with AI, using the tool to generate many possible positions or projects. Students decide which one to pursue and why.

- Develop an initial draft of code on their own, ask AI for assistance to revise or debug, and evaluate the effectiveness of AI in improving the final product.

The specific prompts a user gives to an AI tool strongly determine the quality of its output. Learning to write effective prompts can help students use AI to its fullest potential. Students might:

- Prompt AI to generate responses on a topic the student knows a lot about and evaluate how different prompt characteristics impact the quality and accuracy of AI responses.

- Research applications of prompt engineering that are emerging in their field or discipline.

- Create custom instructions for AI to help with a specific, challenging task. Share their results with peers and evaluate the effectiveness of each others’ results.

If you allow students to utilize AI in their work:

- Make it clear that students are responsible for any inaccuracies in content or citations generated by AI, and that they should own whatever positions they take in submissions.

- Set and communicate clear expectations for when and how AI contributions must be acknowledged or cited.

- Consider barriers that prevent equitable access to high-quality AI tools . S tudents may also have varying levels of AI knowledge and experience us ing the tools. CETLI can assist you in developing an inclusive plan to ensure students can complete the assignment.

If students may use AI with proper attribution, APA , MLA , and Chicago styles each offer recommendations for how to cite AI-generated contributions.

Harvard’s metaLAB AI Pedagogy Project provides additional sample assignments designed to incorporate AI, which are free to use, share, or adapt with appropriate attribution.

CETLI Can Help

CETLI staff are available to discuss ideas or concerns related to generative AI and your teaching, and we can work with your program or department to facilitate conversations about this technology. Contact CETLI to learn more .

- Course Policies & Communication

- Feature Stories: AI in the Classroom

More Resources

- Supporting Your Students

- Inclusive & Equitable Teaching

- Teaching with Technology

- Generative AI & Your Teaching

- Structured Active In-class Learning (SAIL)

- Syllabus Language & Policies

- Academic Integrity

- Course Evaluations

- Teaching Online

- Course Roster, Classroom & Calendar Info

- Policies Concerning Student-Faculty Interactions

- For New Faculty

- Teaching Grants for Faculty

Eberly Center

Teaching excellence & educational innovation, creating assignments.

Here are some general suggestions and questions to consider when creating assignments. There are also many other resources in print and on the web that provide examples of interesting, discipline-specific assignment ideas.

Consider your learning objectives.

What do you want students to learn in your course? What could they do that would show you that they have learned it? To determine assignments that truly serve your course objectives, it is useful to write out your objectives in this form: I want my students to be able to ____. Use active, measurable verbs as you complete that sentence (e.g., compare theories, discuss ramifications, recommend strategies), and your learning objectives will point you towards suitable assignments.

Design assignments that are interesting and challenging.

This is the fun side of assignment design. Consider how to focus students’ thinking in ways that are creative, challenging, and motivating. Think beyond the conventional assignment type! For example, one American historian requires students to write diary entries for a hypothetical Nebraska farmwoman in the 1890s. By specifying that students’ diary entries must demonstrate the breadth of their historical knowledge (e.g., gender, economics, technology, diet, family structure), the instructor gets students to exercise their imaginations while also accomplishing the learning objectives of the course (Walvoord & Anderson, 1989, p. 25).

Double-check alignment.

After creating your assignments, go back to your learning objectives and make sure there is still a good match between what you want students to learn and what you are asking them to do. If you find a mismatch, you will need to adjust either the assignments or the learning objectives. For instance, if your goal is for students to be able to analyze and evaluate texts, but your assignments only ask them to summarize texts, you would need to add an analytical and evaluative dimension to some assignments or rethink your learning objectives.

Name assignments accurately.

Students can be misled by assignments that are named inappropriately. For example, if you want students to analyze a product’s strengths and weaknesses but you call the assignment a “product description,” students may focus all their energies on the descriptive, not the critical, elements of the task. Thus, it is important to ensure that the titles of your assignments communicate their intention accurately to students.

Consider sequencing.

Think about how to order your assignments so that they build skills in a logical sequence. Ideally, assignments that require the most synthesis of skills and knowledge should come later in the semester, preceded by smaller assignments that build these skills incrementally. For example, if an instructor’s final assignment is a research project that requires students to evaluate a technological solution to an environmental problem, earlier assignments should reinforce component skills, including the ability to identify and discuss key environmental issues, apply evaluative criteria, and find appropriate research sources.

Think about scheduling.

Consider your intended assignments in relation to the academic calendar and decide how they can be reasonably spaced throughout the semester, taking into account holidays and key campus events. Consider how long it will take students to complete all parts of the assignment (e.g., planning, library research, reading, coordinating groups, writing, integrating the contributions of team members, developing a presentation), and be sure to allow sufficient time between assignments.

Check feasibility.

Is the workload you have in mind reasonable for your students? Is the grading burden manageable for you? Sometimes there are ways to reduce workload (whether for you or for students) without compromising learning objectives. For example, if a primary objective in assigning a project is for students to identify an interesting engineering problem and do some preliminary research on it, it might be reasonable to require students to submit a project proposal and annotated bibliography rather than a fully developed report. If your learning objectives are clear, you will see where corners can be cut without sacrificing educational quality.

Articulate the task description clearly.

If an assignment is vague, students may interpret it any number of ways – and not necessarily how you intended. Thus, it is critical to clearly and unambiguously identify the task students are to do (e.g., design a website to help high school students locate environmental resources, create an annotated bibliography of readings on apartheid). It can be helpful to differentiate the central task (what students are supposed to produce) from other advice and information you provide in your assignment description.

Establish clear performance criteria.

Different instructors apply different criteria when grading student work, so it’s important that you clearly articulate to students what your criteria are. To do so, think about the best student work you have seen on similar tasks and try to identify the specific characteristics that made it excellent, such as clarity of thought, originality, logical organization, or use of a wide range of sources. Then identify the characteristics of the worst student work you have seen, such as shaky evidence, weak organizational structure, or lack of focus. Identifying these characteristics can help you consciously articulate the criteria you already apply. It is important to communicate these criteria to students, whether in your assignment description or as a separate rubric or scoring guide . Clearly articulated performance criteria can prevent unnecessary confusion about your expectations while also setting a high standard for students to meet.

Specify the intended audience.

Students make assumptions about the audience they are addressing in papers and presentations, which influences how they pitch their message. For example, students may assume that, since the instructor is their primary audience, they do not need to define discipline-specific terms or concepts. These assumptions may not match the instructor’s expectations. Thus, it is important on assignments to specify the intended audience http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/pop10e.cfm (e.g., undergraduates with no biology background, a potential funder who does not know engineering).

Specify the purpose of the assignment.

If students are unclear about the goals or purpose of the assignment, they may make unnecessary mistakes. For example, if students believe an assignment is focused on summarizing research as opposed to evaluating it, they may seriously miscalculate the task and put their energies in the wrong place. The same is true they think the goal of an economics problem set is to find the correct answer, rather than demonstrate a clear chain of economic reasoning. Consequently, it is important to make your objectives for the assignment clear to students.

Specify the parameters.

If you have specific parameters in mind for the assignment (e.g., length, size, formatting, citation conventions) you should be sure to specify them in your assignment description. Otherwise, students may misapply conventions and formats they learned in other courses that are not appropriate for yours.

A Checklist for Designing Assignments

Here is a set of questions you can ask yourself when creating an assignment.

- Provided a written description of the assignment (in the syllabus or in a separate document)?

- Specified the purpose of the assignment?

- Indicated the intended audience?

- Articulated the instructions in precise and unambiguous language?

- Provided information about the appropriate format and presentation (e.g., page length, typed, cover sheet, bibliography)?

- Indicated special instructions, such as a particular citation style or headings?

- Specified the due date and the consequences for missing it?

- Articulated performance criteria clearly?

- Indicated the assignment’s point value or percentage of the course grade?

- Provided students (where appropriate) with models or samples?

Adapted from the WAC Clearinghouse at http://wac.colostate.edu/intro/pop10e.cfm .

CONTACT US to talk with an Eberly colleague in person!

- Faculty Support

- Graduate Student Support

- Canvas @ Carnegie Mellon

- Quick Links

- Assignment Design

- Office of the Provost and EVP

- Teaching and Learning

- Faculty Collaborative for Teaching Innovation

- Digital Resources for Teaching (DRT)

Sections: General Principles of Assignment Design Additional Resources

General Principles of Assignment Design

Assignments: Make Them Effective, Engaging, and Equitable. At their best, assignments are one of the most important learning experiences for students in a course. Students grapple with course content, deepen their understanding, form new ideas, connections, and questions, and show how they are achieving the course or program learning outcomes. Assignments can also affirm students' social identities, interests, and abilities in ways that foster belonging and academic success.

Characteristics of Effective, Engaging, and Equitable Assignments

- Address the central learning outcomes/objectives of your courses. This ensures the relevancy of the assignment (students won’t wonder why they’re doing it) and provides you with an assessment of student learning that tells you about the progress your students are making.

- Interesting and challenging . What assignments are most memorable to you? Chances are they asked you to apply knowledge to an interesting problem or to do it in a creative way. Assignments can be seen as more relevant when they connect to a real world problem or situation, or when students imagine they are presenting the information to a real world audience (e.g., policy makers), or when they can bring in some aspect of their own experience. Assignments can also be contextualized to reflect the values or priorities of the institution.

- Purpose: Why are you asking students to do the assignment? How does it connect with course learning objectives and support broader skill development that students can draw upon well after your class is over? Often the purpose is very clear to us but we don’t always spell it out for our students.

- Tasks: What steps will students need to take to complete the assignment successfully? Laying this out helps students organize what they need to do and when.

- Criteria for Success: What does excellence look like? This can be described through text or a rubric that aligns expectations with the key elements of the assignment.

- Utility value: How can you make adjustments that allow students to perceive the assignment has more value, either professionally, academically, or personally?

- Inclusive content: Is the assignment equally accessible to all students? If examples are drawn from the dominant culture, they are less accessible to students from other cultures. Structuring assignments so that content is equally familiar to all students reduces educational equity gaps by limiting the effects of prior knowledge and privilege.

- Flexibility and variety: Consider how much flexibility and variety you’re offering in your assignments. This allows students to show what they have learned regardless of their academic strengths or familiarity with particular assignment types. Can students choose among different formats for how they’ll present their assignment (paper, podcast or infographic); is there variety in formats across all the course assignments? Multi-modal assignments allow students to represent what they know in various ways and are therefore more equitable by design.

- Support assignments with instructional activities. Planning learning activities that support students’ best work on their assignments is another critical component. This can include having students read model articles in the style in which you are asking them to prepare their own assignment, discuss or apply the rubric to a sample paper, or break the assignment into smaller pieces so that students can get feedback from you or peers on how they are progressing. Another way to support students is to make clear the role of tools like ChatGPT: if it’s used, how can students use it effectively and responsibly? More generally, all major assignments provide opportunities for important discussions about academic integrity and its relevance to work in one’s discipline, higher education, and personal development.

- Provide opportunities for feedback and revision (especially if high-stakes) . Students may receive feedback on their progress or drafts in a variety of ways: peer, faculty, or a library partner. The Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning identifies four characteristics of effective feedback: Targeted and Concise; Focused; Action-Oriented; and Timely.

For assignments that ask students to write in the style of a particular discipline and draw upon research, SCU’s Success in Writing, Information, and Research Literacy (SWIRL) project has developed guidance for faculty in assignment design and instruction to improve student writing and critical use of information.

You can download the WRITE assignment design tool and learn more at the SWIRL website. Members of the SWIRL team welcome individual consultations with faculty on assignment design. You are welcome to contact them for feedback on any assignment you’re designing.

Additional Resources:

Columbia Center for Teaching and Learning (2021). Feedback for Learning. Columbia University. Retrieved [February 26, 2024] from https://ctl.columbia.edu/resources-and-technology/resources/feedback-for-learning/

Hobbs H. T., Singer-Freeman K. E., Robinson C. (2021). Considering the effects of assignment choices on equity gaps. Research and Practice in Assessment, 16 (1), 49–62.

SWIRL : For assignments that ask students to write in the style of a particular discipline and draw upon research, SCU’s Success in Writing, Information, and Research Literacy (SWIRL) project has developed guidance for faculty in assignment design and instruction to improve student writing and critical use of information. You can download the WRITE assignment design tool and learn more at the SWIRL website.

Transparency in Higher Education Project: Examples and Resources. Copyright © 2009-2023 M.A. Winkelmes. Retrieved [February 26, 2024] from https://tilthighered.com/tiltexamplesandresources

Winkelmes, M., Boye, A., & Tapp, S. (Eds.). (2019). Transparent design in higher education teaching and leadership. Stylus Publishing.

Page authors: Chris Bachen

Last updated: March 5, 2024

Assignment Design Checklist

Use this very simple checklist to assess your assignment design.

- What is the assignment asking students to do?

- Does what the assignment asks match the author’s purposes (given the nature of the class, etc.)?

- Is there a discernible central question or task?

- Is the assignment clear?

- Are there words or phrases that might be confusing or unclear to the intended audience?

- Is the assignment itself separate from thought questions or process suggestions?

Format and Organization:

- Look at the layout on the page. Is there a long narrative of unbroken text?

- A long series of questions?

- How is it organized?

- Do the layout and order help the audience understand the assignment?

- Can it be broken into steps or paragraphs?

- Are suggestions separated from the assignment itself?

- If the assignment is a major essay, are there any steps or process work assigned along the way to the final draft?

Adapted from Gail Offen-Brown, College Writing 300, UC Berkeley, Fall 2005

- Professional

- International

Select a product below:

- Connect Math Hosted by ALEKS

- My Bookshelf (eBook Access)

Sign in to Shop:

My Account Details

- My Information

- Security & Login

- Order History

- My Digital Products

Log In to My PreK-12 Platform

- AP/Honors & Electives

- my.mheducation.com

- Open Learning Platform

Log In to My Higher Ed Platform

- Connect Math Hosted by Aleks

Business and Economics

Accounting Business Communication Business Law Business Mathematics Business Statistics & Analytics Computer & Information Technology Decision Sciences & Operations Management Economics Finance Keyboarding Introduction to Business Insurance & Real Estate Management Information Systems Management Marketing

Humanities, Social Science and Language

American Government Anthropology Art Career Development Communication Criminal Justice Developmental English Education Film Composition Health and Human Performance

History Humanities Music Philosophy and Religion Psychology Sociology Student Success Theater World Languages

Science, Engineering and Math

Agriculture & Forestry Anatomy & Physiology Astronomy & Physical Science Biology - Majors Biology - Non-Majors Chemistry Cell/Molecular Biology & Genetics Earth & Environmental Science Ecology Engineering/Computer Science Engineering Technologies - Trade & Tech Health Professions Mathematics Microbiology Nutrition Physics Plants & Animals

Digital Products

Connect® Course management , reporting , and student learning tools backed by great support .

McGraw Hill GO Greenlight learning with the new eBook+

ALEKS® Personalize learning and assessment

ALEKS® Placement, Preparation, and Learning Achieve accurate math placement

SIMnet Ignite mastery of MS Office and IT skills

McGraw Hill eBook & ReadAnywhere App Get learning that fits anytime, anywhere

Sharpen: Study App A reliable study app for students

Virtual Labs Flexible, realistic science simulations

Inclusive Access Reduce costs and increase success

LMS Integration Log in and sync up

Math Placement Achieve accurate math placement

Content Collections powered by Create® Curate and deliver your ideal content

Custom Courseware Solutions Teach your course your way

Professional Services Collaborate to optimize outcomes

Remote Proctoring Validate online exams even offsite

Institutional Solutions Increase engagement, lower costs, and improve access for your students

General Help & Support Info Customer Service & Tech Support contact information

Online Technical Support Center FAQs, articles, chat, email or phone support

Support At Every Step Instructor tools, training and resources for ALEKS , Connect & SIMnet

Instructor Sample Requests Get step by step instructions for requesting an evaluation, exam, or desk copy

Platform System Check System status in real time

Creative Ways to Design Assignments for Student Success

There are many creative ways in which teachers can design assignments to support student success..

There are many creative ways in which teachers can design assignments to support student success. We can do this while simultaneously not getting bogged down with the various obstructions that keep students from both completing and learning from the assignments. For me, assignments fall into two categories: those that are graded automatically, such as SmartBook® readings and quizzes in Connect®; and those that I need to grade by hand, such as writing assignments.

For those of us teaching large, introductory classes, most of our assignments are graded automatically, which is great for our time management. But our students will ultimately deliver a plethora of colorful excuses as to why they were not completed and why extensions are warranted. How do we give them a little leeway to make the semester run more smoothly, so there are fewer worries about a reading that was missed or a quiz that went by too quickly? Here are a few tactics I use.

Automatically graded assignments:

Multiple assignment attempts

- This eases the mental pressure of a timed assignment and covers computer mishaps or human error on the first attempt.

- You can deduct points for every attempt taken if you are worried about students taking advantage.

Automatically dropped assignments

- Within a subset or set of assignments, automatically drop a few from grading. This can take care of all excuses for missing an assignment.

- Additionally, you can give a little grade boost to those who complete all their assignments (over a certain grade).

Due dates

- Consider staggering due dates during the week instead of making them all due on Sunday night.