- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

The Philosophy of Digital Art

The philosophy of digital art is the philosophical study of art that crucially relies on computer processing in its production or presentation. There are many kinds of digital art, including digital cinema and video, digital photography and painting, electronic music, literary works generated by so-called “chatbots”, NFT art, net art, and video games. For the full range of digital art kinds, the aim is to identify their essential features, ground their proper appreciation, and situate our understanding of them in relation to pre-existing debates in aesthetics. This first-order inquiry cannot proceed without acknowledgment of the enormous interdisciplinary and popular interest in digital media. Claims are frequently made about fundamental shifts in the way we classify, evaluate, and engage with art now that computers seem to be involved in every kind of cultural production. The so-called “digital condition” (Kittler 1999) is characterized by a loss of trust in the image, a new way of experiencing the world as indeterminate and fragmentary, and a breakdown of traditional boundaries between artist and audience, artwork and artistic process. If we are looking for evidence of the digital condition, we need to understand its conceptual structure. Here’s where the philosopher comes in.

Although technology-based art is viewed as the “final avant-garde of the twentieth-century” (Rush 2005), and digital art has been part of the mainstream art world since the late 1990s (Paul 2008), the philosophy of digital art is still an emerging subfield. Three seminal monographs, one on videogames (Tavinor 2009), one on digital cinema (Gaut 2010), and one on computer art (Lopes 2010), have been invaluable in laying the groundwork concerning philosophical questions about art and computer technology. Since these publications, further philosophical attention has been given to the digital arts, including the first published volume to focus on the aesthetics of videogames (see Robson & Tavinor, eds., 2018). It can be challenging for philosophers to keep up with the rapid rate at which digital technology develops. But a number of recent articles on Artificial Intelligence (AI) in the arts show that philosophers are well aware of and ready to meet this challenge (Atencia-Linares and Artiga 2022; Millière 2022; Moruzzi 2022; Roberts and Krueger 2022). The body of philosophical work on AI art will no doubt continue to grow, as will bodies of work on virtual reality in art and Internet art. With this growth, we can expect to to learn a great deal more about the extent and character of the digital cultural revolution.

1.1 The Digital Art World

1.2 the analog-digital distinction, 1.3 digital art: production, 1.4 digital art: presentation, 2. digital images, 3. appreciating artworks in digital media, 4.1 defining interactive works, 4.2 display variability, 4.3 interactivity and creativity, 5. locative art, other internet resources, related entries, 1. what is digital art.

In its broadest extant sense, “digital art” refers to art that relies on computer-based digital encoding, or on the electronic storage and processing of information in different formats—text, numbers, images, sounds—in a common binary code. The ways in which art-making can incorporate computer-based digital encoding are extremely diverse. A digital photograph may be the product of a manipulated sample of visual information captured with a digital camera from a “live” scene or captured with a scanner from a traditional celluloid photograph. Music can be recorded and then manipulated digitally or created digitally with specialized computer software. And a film is now the product of an extremely complex sequence of choices between analog and digital processes at the stages of image and sound capture or composition, image and sound editing, color correction or sound mastering, special effects production, and display or projection.

The complexity of the digital cinema workflow draws attention to a further difference concerning whether reliance on the digital is restricted to the way an artwork is made or extends to the display of the work. A work may be made on a computer—say, a musical work composed with Sibelius or a play written in Microsoft Word—and yet meant for apprehension in a non-digital format—say, performance on traditional musical instruments or enactment on stage. Similarly, a film could be captured and edited digitally before being printed on traditional 35mm photochemical film for projection in theaters. By contrast, works that are purely digital include a film made and projected digitally—for example, Dune (2021), a piece of music composed and played back electronically—for example, the electroacoustic works of Gottfried Michael Koenig (see Other Internet Resources ), and a work of ASCII art—an image made up from the 95 printable characters defined by the ASCII standard of 1963 and displayed on a computer monitor.

An example of ASCII art:

More recent kinds of purely digital art include Instagram art and Chatbot fiction. An example of the former is Land of Arca (2023), which is made up of narrative images created by AI and then curated by the Instagram account’s owner, IRK. An example of the latter is any of the myriad science fiction short stories with which several literary magazines were recently deluged.

Each of the examples above incorporates a computational process, to some degree, in the presentation of the work. In many ways, works belonging to digital media stand in stark contrast to those made by completely analog means.

The classical account of the analog-digital distinction is found in Nelson Goodman’s Languages of Art (1976). In fact Goodman’s account remains practically the only general account of the distinction. While David Lewis (1971) raises a series of objections to Goodman, Lewis’ alternative account applies only to the representation of numbers. And while John Haugeland (1981) returns to the general distinction, he effectively qualifies and re-frames Goodman’s account in order to overcome Lewis’s and other potential objections. A few philosophers interested in clarifying the concepts employed by cognitive scientists have recognized the need for a general account of the analog-digital distinction (e.g., Dretske 1981; Blachowicz 1997; Katz 2008; Maley 2011). But in this context, as well, Goodman’s account is the essential point of reference. In some ways, this is surprising or at least striking: As Haugeland points out, the digital is a “mundane engineering notion” (1981: 217). Yet the philosophical context in which the notion receives its fullest analysis is that of aesthetics. As is well-known, Goodman’s interests in this context center on the role of musical notation in fixing the identity of musical works. But a musical notation is also a standard example of a digital system.

On Goodman’s broad, structuralist way of thinking, representational systems in general consist of sets of possible physical objects that count as token representations. Objects are grouped under syntactic and semantic types, and interesting differences between kinds of representational system track differences in the way syntactic and semantic types relate to one another. Digital systems are distinguished by being differentiated as opposed to dense . The condition of syntactic differentiation is met when the differences between classes of token representations are limited such that it is possible for users of the system always to tell that a token belongs to at most one class. The condition of semantic differentiation is met when the extension of each type, or the class of referents corresponding to a class of token representations, differs in limited ways from the extension of any other type; so that users of the system can always tell that a referent belongs to at most one extension. Goodman provides the following example of a simple digital computer, a system that meets the conditions of both syntactic and semantic differentiation: Say we have an instrument reporting on the number of dimes dropped into a toy bank with a capacity for holding 50 dimes, where the count is reported by an Arabic numeral on a small display (Goodman 1976: 159). In this system, the syntactic types are just the numbers 0–50, which have as their instances the discrete displays, at different times, of the corresponding Arabic numerals. Both the conditions of syntactic and semantic differentiation are met because the relevant differences between instances of different numbers are both highly circumscribed and conspicuous. This means that users of the system can be expected to be able to read the display, or determine which number is instantiated on the display (syntactic differentiation) and which numerical value, or how many coins, is thereby being indicated (semantic differentiation).

Analog representation fails to be differentiated because it is dense. With an ordering of types such that between any two types, there is a third, it is impossible to determine instantiation of at most one type. Not every case involving a failure of finite differentiation is a case of density but, in practice, most are. With a traditional thermometer, for example, heights of mercury that differ to any degree count as distinct syntactic types and the kinds of things that can differ semantically. Similarly, for pictures distinguished according to regions of color, for any two pictures, no matter how closely similar, one can always find a third more similar to each of them than they are to each other. Density is a feature of any system that measures continuously varying values. That is, as long as the system in question is designed so that any difference in magnitude indicates a difference in type.

Returning to the digital, some commentators have questioned whether Goodman’s condition of (syntactic and semantic) finite differentiation is sufficient to distinguish the kind of representation in question (Haugeland 1981; Lewis 1971). John Haugeland, for example, argues that there can be differentiated schemes without the “copyability” feature that defines the practical significance of digital systems. Haugeland’s solution is to require the practical and not just the theoretical possibility of a system’s users determining type membership. In fact, however, Goodman himself would likely accept this modification. In a later work, Goodman explicitly states that finite differentiation must make it possible to determine type membership “by means available and appropriate to the given user of the given scheme” (Goodman and Elgin 1988: 125).

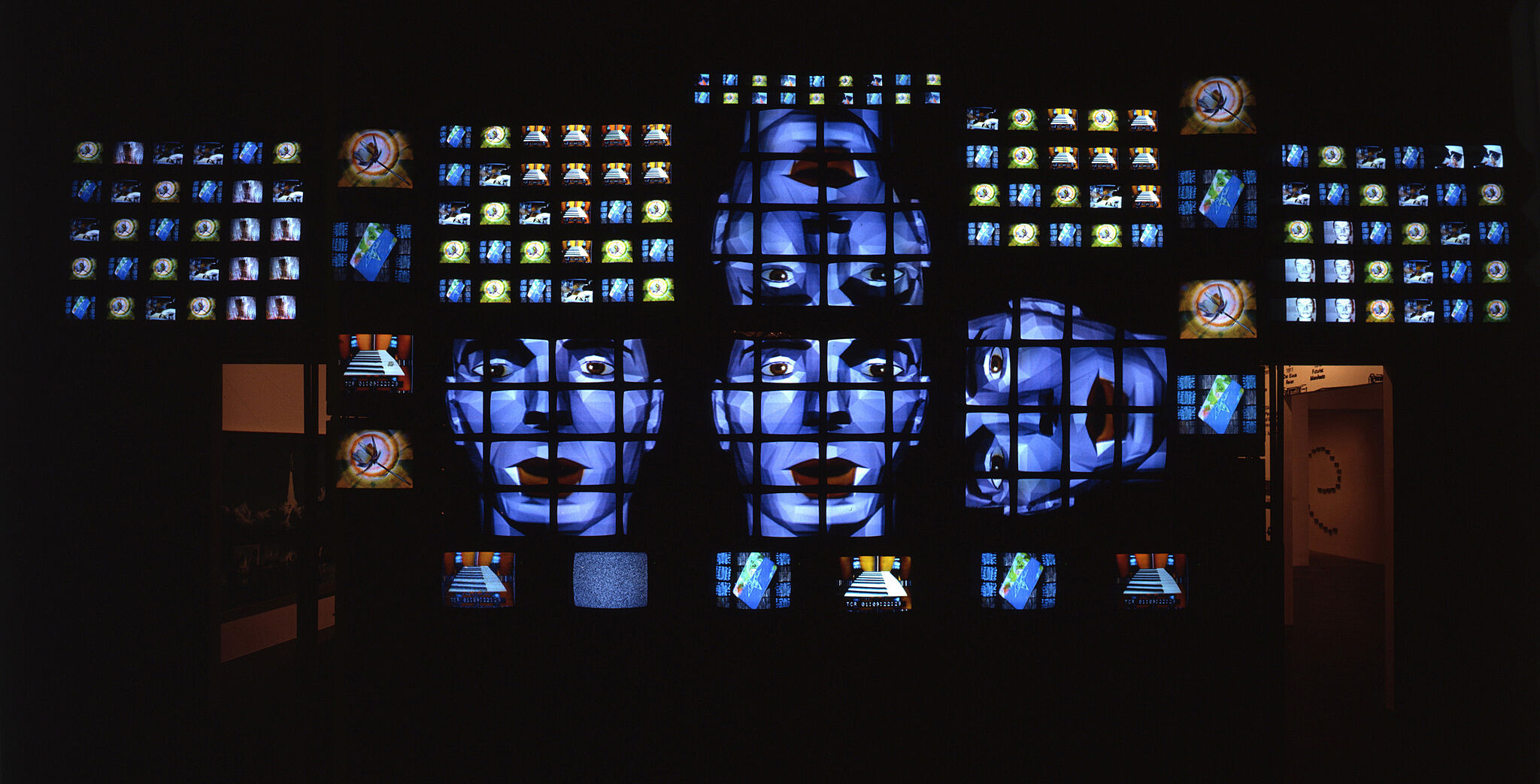

Whether or not a work of digital art is a work of representational art, and even with the most abstract works of digital art, there are layers of representation involved in the complex processes of their production and presentation. Most of these layers, and arguably the most important ones, are digital. Where there are analog systems involved, digital translation makes possible the realization of the values of the final work. This is perhaps best seen with paradigmatic cases of digital art. Consider the following two relatively early works:

- Craig Kalpakjian, Corridor , 1995. Computer-generated animation on laser video disc, in the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. The video leads us slowly down an empty office hallway that is slightly curved and evenly lit, with pale, blank walls and opaque glass windows.

- Cory Arcangel and Paul B. Davis, Landscape Study #4 , 2002. Installation. A “reverse-engineered” video game that aims to transpose our everyday surroundings onto a video game platform. The work “plays” on a Nintendo gaming system and displays a continuously scrolling landscape with the blocky, minimalist graphics of the Mario Bros. game.

The first of these works involves digital moving imagery that is entirely generated by a computer program. At the same time, the video looks like it was or could have been recorded in an actual office setting. The particular significance of the work depends on the viewer being aware of its digital composition while at the same time being struck by its photorealistic familiarity. According to the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (SF MoMA),

Kalpakjian thus reveals the complete artificiality of the built environments we inhabit, and their aesthetic distance from more humanistic forms. (SF MoMA n.d.)

The second work involves imagery that was initially captured digitally. Arcangel & Davis began by taking 360-degree photographs of Buffalo, New York. They scanned and modified the photographs on their computer so that the images could be coded according to the graphics capabilities of the Nintendo gaming system, and in order to give the images the distinctive look and feel of the Mario Bros. game. Arcangel & Davis then programmed the landscape imagery to scroll continuously across a TV screen, as in the Mario Bros. game. Finally, Arcangel & Davis melted the chips in a Super Mario cartridge, replacing them with their self-manufactured chips so that their landscape “game” could be run on any Nintendo system. As well as all the ways in which Arcangel & Davis’s work relies on both the technology and aesthetics of videogames, there are clearly ways in which it deliberately removes or blocks certain key features or capacities of videogames, perhaps most notably their robust interactivity. Playing a videogame essentially involves the prescribed creation of new display instances of a work. But we do not “play” Landscape Study #4 , and its imagery is fixed by the artist. The kind of interactivity typical of videogames can also be found in artworks made without computers (see Lopes 2010: 49). But this type of interactivity is most closely associated with digital art because complex interactivity is so much easier to achieve with the use of computers. This suggests a high degree of self-consciousness in Arcangel & Davis’s decision to block the interactivity of their reverse-engineered videogame. From the perspective of the philosophy of digital art, such a decision highlights the need for further discussion of the link between the nature of the digital and the nature of interactivity.

What is it about the ways in which the works by Arcangel & Davis, and by Kalpakjian, are produced that makes them digital in an appreciatively relevant sense? Computer imaging depends on the inherent programmability and automation of digital computers. Digital image capture depends on sampling and subsequently on the near-instantaneous processes of discrete coding. None of this would be possible without a series of linked systems each with finitely differentiated settings.

At the most basic level, the myriad transistors in a computer are essentially tiny digital schemes, each with two types: the “on” and “off” settings of the transistor-capacitor switch. The settings are discrete and distinguishable, as are their compliance classes, of 1s and 0s. The ubiquity of binary code in computer processing is a consequence of the fact that a digital computer is essentially a vast collection of on-off switches. A particular sequence of 1s and 0s realized at a particular time in virtue of the requisite arrangement of transistors is a binary instance of a particular number, interchangeable with all other instances of the same number and not interchangeable with any instances of different numbers. The difference between instances of one number and instances of other numbers is strictly limited to the difference in the ordering of 1s and 0s. In other words, Goodman’s condition of finite differentiation is clearly met. In turn, the numbers can refer to other values, including the light-intensity values of an image. A computation simply involves the generation of output strings of binary digits from input strings, in accordance with a general rule that depends on the properties of the strings (Piccinini 2008). The modern (digital) computer encodes both input data and assembly languages as sequences of binary digits, or bits, and allows for the internal storage of instructions. This makes the computer essentially programmable in the sense that it can be modified to compute new functions simply by being fed an appropriate arrangement of bits.

A program is a list of instructions, and instructions are strings of digits. The modern digital computer has components that serve to copy and store programs inside the machine, and to supply instructions to the computer’s processing units for implementation in the appropriate order. The outputs of a system can be dependent on specific inputs often in tandem with the conditional if-then statements. This is what is involved in a computer executing conditional branching instructions such that it can monitor and respond to its own intermediate computational states and even modify instructions based on its own processes. Such modifications are dictated by an algorithm—the program’s set of rules and operations. It is the digital computer’s capacity for branching, due to its digital programmability, that allows for the kinds of higher-level automation involved in the use of imaging applications and sequential image-generation. Our artists, Kalpakjian, and Arcangel & Davis, do not have to enter the strings of digits for every basic operation of the computer that underlies the complex operations involved in describing and manipulating images. If they did have to do this, they would never finish making their artworks. Rather, artists can rely on open-source code, libraries, or commercial software that automatically and instantaneously supplies the lines of code required for the execution of their artistic decisions.

The imaging software with which Kalpakjian works allows him to generate architectural interiors in rich detail. Arcangel & Davis do not require as much from their imaging software given that they are manipulating previously captured and scanned images. The process of scanning the photographs, just like the process involved in digital photography, involves sampling and quantization of a visual source; assigning an integer, from a finite range, to the average light-intensity measured across each small area of source-space corresponding to a cell in a grid. This process involves averaging and rounding up values, and it involves measurement, or sampling, of light intensities at (spatially and temporally) discrete intervals. Some, indeed many, of the differences in light intensity across the source image or scene (and at different times, in the case of moving imagery) are thereby dropped by the process of digital image-capture. Among some media theorists, this fact has led to deep suspicion of the digitally recorded image, prompting the feeling that the digital image is always a poor substitute for the analog. Current digital technologies for image-capture and display have such high rates of sampling frequency and resolution that the values dropped in quantization are well below the threshold of human perception. At the same time, Arcangel & Davis’s Landscape Study #4 reminds us that digital artists may choose to exploit visible pixellation for particular artistic ends.

A digitally recorded image need not appear any less richly detailed or varied in color than an analog image. All the same, in the terms of D. N. Rodowick, whereas the analog photograph is an “isomorphic transcription” of its subject, a digital photograph is a “data-output”, with a symbolically-mediated link to its subject (Rodowick 2007: 117–8). This ontological divide—described by William J. Mitchell as a “sudden and decisive rupture” in the history of photography (1994: 59), is then assumed to have aesthetic implications: Rodowick insists that the “discontinuities” in digital information “produce perceptual or aesthetic effects”. Despite this insistence, however, Rodowick goes on to acknowledge that, with enough resolution, “a digital photograph can simulate the look of a continuously produced analogical image”. This concession would seem to work against any attempt to identify the aesthetic effects of pixellation, even if “the pixel grid remains in the logical structure of the image” (Rodowick 2007: 119). But if we are to interpret Rodowick charitably, he could be implying that ontology at least partly determines appropriate appreciation; even if a digital photograph can look just like an analog photograph, its (known) digital status affects which of its perceptible features are aesthetically relevant and how we appropriately engage with them.

The media theorists’ worry about the impoverished digital image primarily refers to the production of digital images with its reliance on sampling and quantization. But there are also analogous worries about the digital presentation of images, worries about deep structural changes to analog images once they are displayed digitally—for example, on a liquid crystal display (LCD) screen or when projected digitally on a flat surface. Of course one could simply be interested in investigating these structural changes without being particularly worried about them. This shall be our approach.

The traditional method of film reel projection has been a remarkably stable and entrenched technology, remaining largely unchanged for over a century. But digital projection has almost taken over, particularly in conjunction with the networked distribution of films. Although films’ audiences may not be able to see the difference on screen between analog and digital projection, their expectations are changing—for example, about what can go wrong in the presentation of a film. A deeper assumption that has not changed, one that is almost universal among film scholars, is that films fundamentally depend on an illusion. Cinema is the art of moving images and thus its very existence depends on our being tricked into seeing a rapid succession of static images as a persistent moving image. In the philosophy of film, there is a small debate about the status of cinematic motion—whether it really is an illusion as commonly assumed. An analysis of digital projection technology reveals new complexities in this debate but ultimately provides additional reasons to stick with the popular illusionist view.

Traditional and digital projection methods could not seem more different: the former involves running a flexible film strip through a mechanical projector; the latter involves a complex array of micromirrors on semiconductor chips, which, in combination with a prism and a lamp, generate projectable images from binary code. Nevertheless, both are methods for generating the impression of a continuously illuminated, persistent moving image from a sequence of static images. Compared with traditional projection, however, digital projection includes an extra step, whereby the images in the static sequence are generated from flashes of light. In order to generate each image in the digital projector, a light beam from a high-powered lamp is separated by a prism into its color components of red, blue, and green. Each color beam then hits a different Digital Micromirror Device (DMD), which is a semiconductor chip covered with more than a million tiny, hinged mirrors. Based on the information encoded in the video signal, the DMDs selectively turn over some of the tiny mirrors to reflect the colored lights. Most of the tiny mirrors are flipped thousands of times a second in order to create the gradations of light and dark making up a monochromatic, pixellated image—a mirror that is flipped on a greater proportion of the time will reflect more light and so will form a brighter pixel than a mirror that is not flipped on for so long. Each DMD reflects a monochromatic image back to the prism, which then recombines the colors to form the projected, full-color image. This image—if it were held for long enough on the screen—would be perceived as static. In order then to produce the impression of motion in the projected, full-color image, the underlying memory array of the DMDs has to update rapidly so that all the micromirrors are released simultaneously and allowed to move into a new “address state”, providing new patterns of light modulation for successive images.

The two-stage process of digital projection, by which the moving image is created from a succession of static images that are themselves created by motion, draws attention to the metaphysical complexity of the question of how movies move. In particular, one is unlikely to determine the status of the impression of motion that makes possible the art of cinema unless one can determine the status of the imagery that is seen to move. Given that motion involves an object occupying contiguous spatial locations in successive moments of time, a moving object must be re-identifiable over time. A moving image in a film, arising as it does out of the rapid display of a succession of still images, is not obviously a persistent object that can be seen to move. Then again, perhaps it is enough that ordinary viewers identify an image—say of a moving train— as the same image, for the moving image to persist (Currie 1996). Alternatively, the moving image could be thought to persist as a second-order physical entity constituted by a sequence of flashing lights (Ponech 2006).

The second proposal immediately runs into trouble with digital projection. If the traditionally projected moving image exists as a series of flashes of light, in digital projection, other “intermediate” objects must be granted existence—for example, the stable point of light consisting of the rate of flashes, and gaps between them, of a single micromirror on the DMD. At the same time, the moving image itself must be stripped of its existence since it does not consist of flashes of light. This is due to the fact that, in digital projection, there are no gaps between frames and so no underlying, imperceptible alternation of light and dark. This leaves the realist in the awkward position of claiming that the moving image goes in and out of existence with the switch between analog and digital projection technologies.

The first proposal, on which cinematic motion is a secondary quality, threatens to destroy the distinction between the apparent and the illusory. It suggests a way of reinterpreting any case of perceptual illusion as a case involving the ascription of secondary qualities. That is, unless it can be shown that there are independent means of checking that we are mistaken about genuine illusions. But even if this can be shown, a problem remains: While there may not be an independent check for the motion of an image, there is likewise no independent check for a genuine illusion of color. Given the contrived conditions of film viewing, there is more reason to think of cinematic motion as akin to an illusory, than to a genuine, experience of color. With the introduction of digital projection, the conditions are arguably even more contrived. For it is not just movement in the image but the image itself that is constituted by rapid flashes of light. And the technology involved is far less accessible than that of a traditional mechanical projector in the sense that one cannot, just by looking at the projection device, see (roughly) how it works. In this way, an analysis of digital movie projection serves to reinforce the traditional assumption that cinema is an art of illusion. In addition, however, the analysis suggests that the illusion at the heart of cinema is particularly impenetrable—akin to an illusion of color, and thus an illusion of a mere appearance that cannot be checked (Thomson-Jones 2013).

With digital movie projection, we begin to see the importance of understanding the technology of display for understanding the nature of digital art. Another way we see its importance is in relation to images displayed on LCD screens. According to Goodman, images are essentially analog. Nevertheless, there seems to be a way for engineers to circumvent the essential analogicity of pictorial schemes by using digital technologies for encoded subphenomenal discrimination. Arguably, finite differentiation can be imposed on the scheme of all possible images displayed on high-resolution LCD screens. As we shall see, this has far-reaching implications for the ways in which we think about and properly appreciate image-based art.

Both in his earlier and in his later work in aesthetics, Goodman commits to “a special relation” between the analog and the pictorial, one that is seen when we compare “the presystematic notions of description and picture in a given culture”. Given two schemes, S and S′ , where S consists of all descriptions or predicates in a language such as English, and S′ consists of all pictures, if we were told only of the structures of S and S′ , we could distinguish the pictorial scheme by its being analog (Goodman and Elgin 1988: 130). The special relation remains, Goodman claims, despite the possibility of a digital sub-scheme made up of black and white grid patterns all of which happen to be pictures. In such a scheme, the differences between patterned types that matter for the scheme’s being digital do not include all of the differences that matter for distinguishing pictorial types. Pictures are distinguished by color, shape, and size, which vary continuously; any variation in color, shape, or size potentially results in a different picture. When we impose limits on the differences that matter for distinguishing one grid pattern in the scheme from another, we are not interpreting the grid patterns as pictures; if we were to do so, we would have to treat them as members of a syntactically dense, or analog, scheme.

Goodman’s insight about grid patterns and pictures suggests an immediate difficulty for explaining the digital status of images displayed on LCD screens: Clearly it will not be sufficient to point out that such images are pixellated, and therefore made up of small identical building blocks that impose a lower limit on the differences between display-instances. Remember that pictures are defined by color, shape, and size, which vary continuously. This means there is going to be vagueness at the limits of types – even though the physical pixels of an LCD screen are such that there are gaps between the possible shapes, sizes, and colors that the screen can instantiate; and, there are a finite number of shapes, sizes, and colors that the screen can instantiate. Any means of discretely carving up the property spaces of color, shape, and size has to involve grouping into types what are in fact (subphenomenally) distinct shapes, sizes, and colors, some of which may differ less from adjacent properties grouped into other types. This makes it impossible always to determine unique class membership; hence, finite differentiation fails.

Pixellation alone, no matter the resolution, cannot account for images displayed on LCD screens belonging to a digital scheme; digital images qua images thus remain stubbornly analog. But perhaps a closer analysis of digital imaging technology can show that finite differentiation is met after all. Current technologies for sampling and instantiating light intensities group objective colors well below the level of phenomenal discrimination. For example, in the standard “Truecolor” system, a display pixel has three 8-bit subpixels, each of which emits a different visible wavelength with an intensity from a range of 256 values, yielding over 16 million objective colors. Such a large number of available colors gives the impression of a color continuum when, in fact, digital sampling technology has been used to carve up the objective color space into a disjoint series of wavelength intensities. On the one hand, from the fact that display pixels can be lit at intensities between and indiscriminable from adjacent discriminable intensities, it seems to follow that finite differentiation fails. On the other hand, precisely because digital technology involves microtechnology and metrology for subphenomenal discrimination between colors, the light intensity groupings that are expressed numerically as red-blue-green triplets (in, say, the Truecolor system) can be narrower than the objective color types that contribute to the resultant image scheme. The key is keeping the variations in the essentially analog properties of color, shape, and size small enough so that they cannot accumulate to the point of making a difference to image perception (Zeimbekis 2012). The types in the scheme of digital images are technologically segmented, transitive groupings of the same color-, shape-, and size-experiences. The carving out of a transitive sub-set of magnitudes has to occur relative to the needs of the users of the system. In the case of digital color, the types are classes of light intensities sufficient to cause the same color experience for normal human perceivers. The replicability of digital images is made possible by the gap between the discriminatory limits of the human visual system and the discriminatory limits of digital sampling technology.

Digital images can be replicated insofar as they are digital and thus finitely differentiated. They are finitely differentiated because they rely on subphenomenal sampling and display technology. In practical terms, replication depends on the use of binary code, even though this is not in fact what makes images qua images digital. Of course binary code representations are themselves part of a digital scheme. But the role of binary code in image-instantiation is just one of consistent preservation; preservation for long enough to permit reproduction. Despite the inherent replicability of digital images, it does not appear to follow automatically that artworks involving these images are multiples.

The SF MoMA is in possession of the original of Kalpakjian’s work, Corridor ; they control access to the video imagery. At present, the work is not available to be viewed: it cannot be viewed on-line as part of a digital archive or collection, nor is it currently on view in the physical space of the museum. The image sequence comprising the work could be multiply instantiated and widely distributed, but in fact it is not, nor is it meant to be. Similarly with Arcangel & Davis’s work, Landscape Study #4 : This work is described as an installation, meant to be exhibited in a physical gallery alongside an arrangement of printed stills, with a television connected to a Nintendo Entertainment System. Again, the image sequence displayed on the television could be multiply instantiated and widely distributed, but it is not, nor is it meant to be. Clips and copies of the landscape imagery are available on-line, but these do not instantiate parts of the work itself. By contrast, works of net art are instantiated whenever they are accessed by someone on-line.

There are many kinds of net art, including various forms of experimental on-line literature, conceptual browser art, and works drawing on software and computer gaming conventions. Extensive on-line collections of visual and audiovisual net art are rigorously curated and at the same time immediately accessible to ordinary Internet users. When it comes to the conventions of access and presentation, the contrast is striking between works of net art and works like those by Kalpakjian, and Arcangel & Davis. Perhaps a digital artwork comprising multiply instantiable images need not itself be multiply instantiable. At this point, the philosophy of digital art joins an ongoing debate about the ontology of art.

On the question of whether artworks are all the same kind of thing or many different kinds of things, ontological pluralism is often taken to be implied by the primary role of the artist in “sanctioning” features of their work (Irvin 2005, 2008; Thomasson 2010). A sanction can consist simply in, say, the painting of a canvas by a self-professed artist and the subsequent display of the work in a gallery. The artist has sanctioned those features of the work that make it a traditional painting. But what was once largely implicit is now often explicit: many contemporary works of art are defined by a set of instructions for their presentation (e.g., aspect ratio, resolution). We can find plenty of examples of non-digital works that are defined by a set of instructions, such as Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ Untitled (Portrait of Ross in L.A.) (1991). This work is given to a gallery to display by way of nothing more than a set of instructions for constructing and maintaining a pile of candies. Whether non-digital or digital, the instructions determine what is part of the work and what is not, and whether the work is singular or multiply instantiable. As a result, the instructions guide appropriate interpretation of the work. On this view, ontology precedes interpretation: we cannot properly and fully appreciate a work, for the work that it is, without a prior determination of what it comprises. This is a matter of contention, however. On another way of thinking, artworks just are objects of interpretation, and there is no artwork whose boundaries can be identified before we begin interpretation (Davies 2004).

The issue of the relation between ontology and interpretation is a complex and difficult one, but progress can be made on the issue through an examination of digital art practices. This is particularly in light of the high degree of self-consciousness with which many digital artists and digital art curators specify the features of digital art works. It is a common practice, for example, when archiving net art, to have artists fill out a questionnaire in order to specify which features of a work are crucial for its preservation—whether features of appearance, timing and motion, interactivity potentials and methods, linking to other sites, or hardware and software. When a work of net art is individuated by its imagery, say, the artist has chosen to make the inherent replicability of digital imagery part of the work. That this is a choice is suggested by the existence of singular works of digital visual art, like the examples discussed above. The question of whether the works by Kalpakjian, and Arcangel & Davis can function allographically requires further investigation (see D’Cruz and Magnus 2014). But if they can so function, the artist’s presentation instructions have a primary role to play in fixing, not just the art form (installation, movie, conceptual work, etc.) but the basic structure of the work – for example, in determining whether the work is singular and thus identical with a certain kind of physical display or multiple with no original display. Where interactive digital works are concerned, individuation is determined by a set of algorithms. An algorithmic account of interactive digital art suggests that, although the code is important for adequate instantiation of the work, it is the algorithm that specifies the crucial features of the work (Lopes 2010; Tavinor 2011; Moser 2018). Since the code is, ontologically speaking, less relevant than the algorithm, this account makes allowances for the variability that may be found in the code when an instance of a program is run on different kinds of devices.

Reflection on the kinds and significance of choices available to an artist contributes to a full appreciation of the artist’s work. For any artwork, appreciation begins with recognition of its status as a work , the product of artistic activity of some kind, and thus something to be appreciated as the achievement of an artist or group of artists. Most commonly, this achievement is understood in terms of the aesthetically significant effects achieved by an artist with certain kinds of tools and materials and in light of certain appreciative conventions. In other words, the achievement is always relative to an artistic medium. Returning to the case of an artist choosing what to do about the inherent replicability of digital imagery, another way of thinking about this choice is in terms of the artist recognizing the limits and capacities of their chosen medium. Images conveyed digitally are always replicable and so when an artist aims to convey artistic content through digital imagery, they either have to accept the inevitable multiplicity of their works or resist the tendency of the medium and somehow specify the work’s singularity in presentation. At a more fine-grained level, our appreciation of particular effects—of color and composition, expression, narrative structure, and so on—depends on the effects themselves but also on background acknowledgment of their degree of difficulty or innovation in the relevant medium. The production of digital art relies on the computer automation of many of the tasks, both manual and cognitive, traditionally involved in making art. The effects achieved by computer automation cannot be assessed in the same way as those achieved by traditional “hands-on” artistic methods. The terms of our appreciation, therefore, need to be adjusted in the digital age. This is certainly compatible with the continued relevance of medium-based appreciation, as long as we can make sense of digital media as artistic media (Binkley 1998). But there is a strong tendency in film and media studies to assume that the medium has absolutely no role to play in the appreciation of digital art.

Summing up this view, it supposedly follows from the fact that modern (digital) computers encode every kind of information in the same way—i.e., as a sequence of binary digits—that a digital artwork is no longer defined by its mode of presentation, whether in images, moving images, sound patterns, or text. A work’s display is rendered merely contingent by the fact that it is generated from a common code. By adding a particular instruction to the code sequence specifying a work, imagery associated with that work could be instantaneously converted into sounds or text, or just into different imagery. This possibility alone supposedly renders meaningless all talk of an artwork being in a particular medium and being properly appreciated in terms of that medium (Kittler 1999; Doane 2007).

Given the considerable effects of digital technology on artistic production, it is perhaps understandable that some commentators are inclined toward a radical overhauling of art theoretical concepts. But their arguments in support of such an overhaul are, at best, incomplete. We see this once we cite some important continuities between ways of making and thinking about art in the analog age and in the digital age. It has always been the case, for example, that “any medium can be translated into any other” (Kittler 1999: 1): Without using a computer, someone could manually devise a set of rules (an algorithm) for the translation of image values, say, into sounds or text. Moreover, a common storage and transmission means for (moving) imagery and sound is not unique to digital technology: As Doron Galili points out (2011), electronic image transmission going back to the late nineteenth century—in other words, precursors of the TV—relies on the conversion of both images and sound into electronic pulses.

Apart from these important continuities, the media theorist’s inference from translatability to medium-free art simply does not hold. That we could set about “translating” the imagery of Seven Samurai into a symphony does not mean that the original artwork lacks a medium; it is a film, after all, and as such, it has to be in the medium of moving images. The symphonic translation of Seven Samurai is not the same work as the 1954 film by Akira Kurosawa. This reminds us that, in deciding whether there is a digital medium, we must not reduce the medium to the artist’s materials, for it also matters how the artist uses those materials. Nor must we limit the constitutive materials of a medium to physical materials. The case of literature shows that neither the materials of an art form, nor their modes of manipulation, need be physical. The medium of literature is neither paper and ink nor abstract lexical symbols, but letters and words used in certain ways. There are, of course, many different ways of physically storing and transmitting literary works, including by the printed page, in audio recordings, and by memory (human or computer). But from the fact that David Copperfield can be preserved in many different formats, it does not follow that this novel is any less decisively a novel and, as such, in the medium of literature.

Just as with a literary work, the preservation and transmission of digital works in different formats depends on the use of a common code, but a binary numeric code rather than a lexical one. As we have seen, words and their literary uses constitute the medium of literature. In the same way, binary code, along with the information it implements, and its artistic uses constitute the medium of digital art. This allows for the possibility that the digital medium contains various sub-media, or “nested” media (Gaut 2010). For instance, within the medium of digital art, the medium of digital visual art comprises artistic uses of computer code specifically to create images. In technical terms, such uses can be referred to as (artistic) “bitmapping”, given that a computer ultimately stores all images (2D and 3D vector) as bitmaps, which are code sequences specifying the integers assigned to light intensity measurements in a pixel grid. The medium of bitmapping is thus distinguished by a kind of digital technology, but the kind used to produce just those items belonging to the traditional medium of images.

Once the notion of digital media is revealed to be no more confused or mysterious than the familiar notion of literary media, its irreducible role in appreciation becomes apparent. To take just one example, proper appreciation of films in the digital age depends on recognizing that digital filmmaking tools do not just make traditional filmmaking easier; they also present new creative possibilities and challenges. Given the maturity and mass-art status of the cinematic art form, it is easy to take for granted the medium of moving imagery; we may think we know exactly what its limits are, and we may even think we have seen everything that can be done with it. The digital medium is different, however, and digital cinema is in both the medium of moving imagery and the digital medium.

At first glance, it might seem odd to speak of “challenges” or “limits” in relation to digital processes, which allow for instantaneous and endless modification with increasingly user-friendly applications and devices. The high degree of automation in the process of capturing an image with a digital video camera, along with increasingly high image resolution and memory capacity, could make it seem as though digital images are too easily achieved to be interesting. Then there are the practically endless possibilities for “correcting” the captured image with applications like Photoshop. When we take a photo or video on our smartphones, an AI program automatically optimizes focus, contrast, and detail. Digital sound recording is likewise increasingly automated, increasingly fine-grained, and reliant on ever-larger computer memory capacities. Modifying and mastering recorded sound with digital editing software allows for an unlimited testing of options. In digital film editing, sequence changes are instantaneous and entirely reversible—quite unlike when the editing process involved the physical cutting and splicing of a film (image or sound) strip. Digital tools thus allow filmmakers to focus (almost) purely on the look and sound of the movie without having to worry about the technical difficulty or finality of implementation.

Rather than dismissing all digital works as too easily achieved to be interesting, medium-based appreciation requires that we consider the digital on its own terms. This means we must allow for the possibility that certain kinds of increased technical efficiency can bring new creative risks. For example, even though committing to certain editorial decisions does not entail irreversible alterations to a filmstrip, arriving at those decisions involves sifting through and eliminating far more options, a process which can easily become overwhelming and therefore more error-ridden. When we properly appreciate a digital film, part of what we need to appreciate is the significance of any scene or sequence looking just the way it does when it could have, so easily, looked many other ways. Similarly, when we properly appreciate an interactive digital installation or videogame, we are, in part, appreciating certain representations, functions, and capabilities of the input-output system, made possible by digital media. This is undeniably a form of medium-based appreciation and the medium to which we appeal is digital. It is only when we think of a digital film as in a digital medium that we can appreciate it as a particular response to the creative problem, introduced by coding, of finalizing selections from a vast array of equally and instantly available options.

The case of digital cinema is perhaps a useful starting point for work in the philosophy of digital art. Digital cinema is a multi-media art form, after all, involving 2D and 3D moving images as well as sound. It also has the potential for robust interactivity, whereby audiences select story events or otherwise modify a film screening in prescribed ways (Gaut 2010: 224–43). Many of the digital tools developed by the film and video game industries are now available more widely to artists interested in making other forms of digital art, including net art, digital sound installations, and virtual reality art (Grau 2003; Chalmers 2017; Tavinor 2019). In terms of how the use of these tools affects proper appreciation, there are important continuities between the filmmaking context and the wider digital art world. In addition, the philosophy of film is a well-established subfield in aesthetics, one that engages with both film theory and cognitive science in order to explicate the nature of film as a mass art (Thomson-Jones 2014, Other Internet Resources). For many of the standard topics in the philosophy of film, interesting and important questions arise when we extend the discussion from analog to digital cinema. There is a question, for example, about the kinds and significance of realism that can be achieved with traditional celluloid film as compared with manipulated digital imagery (Gaut 2010: 60–97). The philosophy of film can provide some of the initial terms of analysis for artworks in a broad range of digital media. At the same time, it is important to approach each of the digital arts on their own terms under the assumption that the digital is an artistically significant category.

4. Interactivity

More and more, contemporary artists are taking advantage of the dynamic and responsive capabilities of digital media to make art interactive. The experimental online literature, conceptual browser art, and videogames mentioned above all require user interactivity, but they do so to varying degrees. Therefore, if interactivity plays a distinctive role in the digital arts, there are good reasons to analyse the nature of these works more deeply.

Not all digital works are interactive, and not all interactive works are digital. However, since computers are inherently interactive, much of the early philosophical literature on interactivity arose from the emergence of computer art (also see Smuts 2009; Lopes 2001; Saltz 1997). The distinctive character of interactive digital art is best considered in tandem with the work’s ontology.

Before analyzing interactivity any further, first, consider the following description of the digital installation “Universe of Water Particles on a Rock where People Gather” (henceforth, “Rock where People Gather”) by TeamLab:

“Rock where People Gather” is reproduced in a virtual three-dimensional space. Water is simulated to fall onto the rock, and the flow of the water draws the shape of the waterfall. The water is represented by a continuum of numerous water particles and the interaction between the particles is then calculated. Lines are drawn in relation to the behavior of the water particles. The lines are then “flattened” using what TeamLab considers to be “ultrasubjective” space. When a person stands on the rock or touches the waterfall, they too become like a rock that changes the flow of water. The flow of water continues to transform in real time due to the interaction of people. Previous visual states can never be replicated, and will never reoccur (TeamLab 2018).

“Rock where People Gather” illustrates that interactive works permit us to appreciate both the work and the properties brought about by the interactions. To define these characteristics of interactive art, Dominic Lopes states, “A work of art is interactive just in case it prescribes that the actions of its users help generate its display” (Lopes 2010:36, original emphasis). The display is anything that is instanced in a work, or the perceptual properties that come about via interactivity. Users help generate these features making interactive works distinctive. However, at this point, one could imagine reading the chapters of, let us say, a digitized copy of The Brothers Karamazov in random order, thereby changing what properties get instanced from the original work. Does this example qualify as interactive art in the Lopesian sense? Although some stories, such as choose-your-own-adventure books, allow readers to shuffle the narrative arc, most traditional stories do not; if the randomized Karamazov example is interactive, it is only so in the weakest sense of the term because users are not prescribed to change the properties as described. Another way to think about these differences returns us to a work’s structure. Readers who decide to roguishly randomize a story merely change how they access a work’s structure simply because the medium does not prohibit it, whereas readers of choose-your-own-adventure books and other interactive works can change the work’s structure in a prescribed manner (Lopes 2001:68).

That users are responsible for generating certain features of an interactive work means that their displays, unlike those of non-interactive works, can occur in a couple of different ways (Lopes 2010: 37-38). The less standard of the two occurs when the displays of an interactive work are generated in a succession of states over a period of time, but where none of the displays can be revisited. One such example is Telegarden , a temporary work of computer art that users accessed from a networked computer. The work was comprised of a table with an attached mechanical arm that dispensed water and food for the plants via the users’ inputs. As one may imagine, the garden took shape in a variety of ways over the span of its exhibition, but each state of the garden, or its succession of display states, could not be repeated. Although not common, videogames can also exhibit this kind of display variability. Consider the experimental game, Cube . For a limited time, players could explore a large cube and its nested smaller cubes while racing to be the first to reach the center. As with Telegarden , players generated different properties of the game displays by interacting with it, but once a new display was generated, the previous ones were gone.

The more standard of the two variable structures for interactive works are displays that can be repeated, such as most net art and videogames that can be accessed many times, from multiple locations, to generate different displays. Although repeatable works are more common (at least with videogames if not museum-housed works), more needs to be said about the changing properties of these works and how the repeatability trait distinguishes interactive digital works from non-interactive digital images.

If the display properties of digital images can vary from instance to instance due to even slightly different settings on different devices (e.g., brightness, resolution, intensity), then the aesthetic and structural differences of many works could be misconstrued as interactive. Since the example just given is not an interactive work of art, it is worth looking more closely at what is going on with non-interactive repeatable works versus interactive repeatable ones. Consider traditional performance works such as works of theater and music. Each performance might differ to a slight degree due to different performers and other varying conditions of the environment, and these may certainly affect our aesthetic experiences each time. However, those changes, in principle, do not reshape the structure of the performed play or song. In the same way, the subtle changes made with a digitally displayed image do not change the structure of the image-based work. Compare those slight artistic or aesthetic variations to the display variability of interactive works. For example, many videogames permit players to choose which route to take, quests to accept, characters to kill or save, personalities to adopt, and the like. These sorts of in-game player choices are not merely generating features such as varying the brightness or resolution, nor are they as straightforwardly interactive as a game of chess that ends in a win or a loss. Rather, the degree of variability permits multiple endings. Again for comparison, while traditional tragedies will always end on a tragic note, some highly variable works can end either on a tragic note or on one that is not at all tragic.

To articulate the above more clearly, Dominic Preston says,

for any given artwork, each possible set of structural and aesthetic properties F is a display type of that artwork. (Preston 2014: 271, original emphasis).

From the above, we can briefly infer the following scenarios: works like digital photographs are ontologically similar to plays and music because they consist of one prescribed display type. While the display type might permit multiple displays (duplicates, performances, instances, etc.) consisting of subtle variances between the particular tokens, there is still a single correct display that should be maintained or achieved. Works that instance a succession of states such as Telegarden and Cube consist of multiple potential display types where only one display type is instantiated at any given time. Now, compare such works with those like videogames that present us with the strong degrees of display variability mentioned earlier. Because some repeatable works can end drastically differently from one “playthrough” to the next, there is no singular, correct display. Instead, these sorts of works consist of both multiple display types and multiple displays, which means users will generate one of the possible display types (and their displays) each time they repeat the work.

According to Katherine Thomson-Jones (2021), there is a problem with Preston’s claim that interactive artworks — at least ones that are digital — have multiple display types, as well as multiple displays. This is because the digital is inherently replicable and replicability requires a transmissible display — a single display type that can have multiple, interchangeable instances. This seems to introduce a problem of incompatibility: How can we have an image whose instances still count as instances of the same image-based work when those instances, in virtue of users’ actions, look very different from one another? There are various ways one might overcome this problem — for example, by distinguishing between the display of an image and the display of an artwork that incorporates the image in question. Preston’s distinction between display and display type can continue to play a role here. While the concept of interactivity with high variability is mostly applicable to videogames, one can imagine interactive digital installations, net art, and table-top roleplaying games to which it also applies.

It is important to reiterate that the strong interactivity just described is not restricted to the digital. Whilst interactivity is a standard feature of many contemporary digital works, and the responsiveness of such works is remarkable, non-digital appreciative categories can also exploit a similar degree of display variability. For example, literature, theater, and tabletop role-playing games can be strongly interactive in ways similar to many digital artworks. What is unique about all such works are the ways in which things like immersion, agency, identity, and fiction, to list a few features, are impacted by interactivity, due to the user’s role in the work (for more, see Robinson & Tavinor 2018; Patridge 2017; Meskin & Robson 2016).

A noteworthy point about the concepts presented above is that they are all conceived with the norms of traditional art and art practices in mind, meaning, works of art that are predominantly object-based. However, as described, interactive digital works can be said to have a “behavior” based on prescribed interactions. While traditional artworks typically emphasize a work that is complete prior to audience engagement, interactive works emphasize the moment-to-moment unfolding of the works by way of audience engagement. One recent approach to the ontology of art suggests that interactive works (among other kinds) are better conceived on a process-based, rather than on an object-based, model (Nguyen 2020). A key difference between the two models is that the former focuses on the user’s actions and experiences or “inward aesthetics”, while the latter focuses on the “outward” aesthetic features of the self-contained object (Nguyen 2020: 25). While a process-based account prioritizes the internalizability of a user’s actions, it does not completely give up the idea of an artistic object. Rather, it renders the object’s significance secondary insofar as any appreciation for a work’s objecthood is in service to the activities it permits (Nguyen 2020: 20).

Just as the case of digital art can enrich our understanding of interactivity, so it can enrich our understanding of artistic creativity and creative attribution. This is in part because the issues of interactivity and creativity are closely related. In making a work that is strongly interactive, an artist cedes to the user a certain amount of control in determining the look, sound, or structure of the work’s display(s). This raises a question about the user’s opportunities to be creative — to engage in creative interactions with a work — and how these opportunities can be supported or constrained by the artist’s design. In order to answer this question, we need to unpack the notion of creative control. In addition, we need to consider how creativity can be attributed to multiple agents involved at different stages of a work’s production. As it turns out, the case of AI art is particularly useful when considering the conditions of creativity and creative collaboration.

There is already a robust debate about the nature of creativity as it occurs in many different areas of human activity (see, e.g., Gaut & Kieran, eds., 2018; Paul & Kaufman, eds., 2014) There is a case to be made, however, that this debate can be enriched by drawing on work in the philosophy of AI. In everyday life, sophisticated AI systems are now being used for all kinds of purposes: We rely on these systems when we use Internet search engines, play strategic videogames, accept purchasing recommendations from online retailers, and check for viruses on our computers. In addition, we can use AI to generate new images and text, some of which can be incorporated into works of art. One can type a series of prompts into a chatbot like ChatGPT in order to generate a new screenplay in a certain genre. Similarly, one can assemble a set of images on which to train an “artbot” like MidJourney in order to generate paintings, drawings, or what look like photographs. It is common to attribute creative agency to the person who purposively initiates, and then monitors, the program used to generate the images or text that make up a work of AI art. A question remains, however, as to whether this should be the sole creative attribution when AI is involved. Some artists describe the AI system with which they work as a creative “partner”, and not just a sophisticated artistic tool. This is particularly the case with recent artworks that rely on “Deep Learning” (DL) to generate images or text in a remarkably independent way. Both chatbots and artbots rely on deep learning to categorize huge datasets (images or text) according to previously undetected patterns. To do this, a DL system must give itself new instructions — ones that depart from the initial instructions of the program — for the kind of image or text segment, and for the particular image or text segment, to be produced.

Among AI artists, the ones who write their own DL programs are the most likely to describe AI as a creative partner rather than just a creative tool. This seems particularly fitting when there is a synchronous collaboration between the artist and their DL system. For example, the works of Sougwen Chun are the result of Chun drawing alongside and in response to the actions of a mechanical drawing arm that is controlled by Chun’s custom-made program, D.O.U.G. (short for “Drawing Operations Unity Generation X ”). Chun and D.O.U.G. take turns adding to a single drawing. During this process, it is harder than one might think to say what makes the difference such that Chun is a creative agent, engaged in a creative drawing process, and D.O.U.G. is not. This is the case even though it is Chun alone who comes up with the idea for the work and initiates the drawing program.

As Margaret Boden has argued (2014), when philosophers deny the possibility of a computer ever being creative, they tend to underestimate the capacities of computers to produce items that are genuinely new as well as valuable in some domain. Still, many creativity theorists argue that novelty and value are insufficient for creativity; a third condition is needed, one concerning the manner of production. In order for something novel and valuable to count as creative, it must have been produced in a way that is agent-driven. The agency condition can be filled out, or broken down, in a variety of ways. At its core, however, the notion of agency is generally assumed to be opposed to the notion of having been ‘programmed’, or simply instructed, to perform certain tasks in a “mechanical”, or blind, fashion. Thus, the most basic objection to the possibility of creative computers is that they can only do what they are programmed to do, according to the intentions of a human agent. This objection needs clarification, however, since no set of rules completely determines the actions involved in following that set of rules. Since the advent of DL and other kinds of generative algorithm, it is possible for a computer program to change itself, to detect independent phenomena other than the ones that it was designed to detect, and to mimic spontaneity through randomness. Is this an instance of creative rule-following? If it is, we might expand our notion of creative collaboration. Perhaps creative collaboration is found, not just between human beings, but also between human beings and machines. In so far as the machines in question support strong interactivity, a work of digital art might involve three-part collaborations between human artists, human users, and AI.

Digital media can also be used for the purpose of connecting physical locations to virtual ones by using locative media. The phrase “locative art” is traced to Karlis Kalnins who applied the phrase to experimental projects coming from Locative Media Lab, a collective of international researchers and practitioners working with locative media. (Galloway & Ward 2005 ). Since the term “locative” is connected to location, site-specificity plays a significant role in our appreciation of locative works. Unlike with non-digital cases, however, site-specificity in locative art is both physical and virtual. The general concept is this: locative-specific media connect physical spaces with virtual ones, the perceptual features of which are generated from a digital device by human interactions. We often experience locative media in our ordinary and daily lives through navigation systems like Google Maps or Waze, and also creatively through augmented reality apps like Pokemon Go, AR graffiti (an app that allows users to visualize what their graffiti will look like in situ ), architectural simulators, and more. These are location-based works, often called locative projects or locative art, that use locative media. While locative technology has been around for decades, it is a relatively new subcategory to be recognized within the arts. Even so, locative art is more broadly acknowledged in the fields of technology, games, and sociology.

To understand the many ways locative media might be used for artistic practice, consider the following three examples.

- What Was There (2010–2023) was a website that allows users to type in the coordinates of their current location (via their digital device) to see how certain geographical locations look throughout history. By typing a specific address into the application, the user experiences the physical location in front of them and represented images and facts of that location as they appeared in the past, from the same vantage point. Data on the site relies on regular citizens to upload historic images and connect them to specific locations, making them accessible to others; the greater the participation the richer the experience when navigating a particular place. Not only can guests gain a deeper connection to their specific localized places, but such applications motivate people to explore and appreciate locations outside of their normal destinations.

- The Transborder Immigrant Tool has been used in a number of artworks and exhibitions.

The Transborder Immigrant Tool, devised by Electronic Disturbance Theater 2.0/b.a.n.g. lab, was a mobile phone application intended to guide individuals who were making their way to the United States through the deserts of the U.S./Mexico borderlands to water. The application delivered poetry to its users in an effort to assist in their emotional and mental well-being while offering information about survival during the dangerous journey. The creators of The Transborder Immigrant Tool considered it to be a performance intervention that included the app itself, its API, public reactions, and an ensuing government investigation. By the time TBT was ready for distribution in 2011, the border crossing had become more dangerous, presenting the risk that carrying a TBT phone might put users in danger. While the project was never distributed to its intended users, it still succeeded in confounding systems of political control, creating a call to action that resonated internationally, and using poetry to “dissolve” the US-Mexico border (Electronic Disturbance Theater 2.0 et al 2007).

- KlingKlangKlong is played with smartphones that translate the players’ locations into sound. This is achieved in a straightforward manner: By moving through the physical space, the players simultaneously move on the surface of a virtual sequencer. One dimension (usually the latitude of the player) corresponds to pitch, the other dimension (longitude) is mapped to the time-position on the sequencer. The interface allows a manual switch to other audio parameters, although this feature is experimental. Each device receives the location and state changes of the currently active players almost instantly. The devices are connected by a central server, which also sets the boundaries of the playing field and manages the virtual players.

KlingKlangKlong serves as an experimental arrangement to explore the idea of playful (social) systems, a construction where human and virtual subsystems play with each other. In addition to the human participants, it therefore deploys a number of virtual players (»Virtuals«). Humans and Virtuals meet each other in mixed reality, a concept that was realized in early locative games. The commonly created soundtrack is the primary medium of communication between the players. Musical structures may temporarily arise through synchronized movements or be destroyed by any player’s intervention (Straeubig & Quack 2016).

In each of these examples, users synchronize geographical locations with virtual ones, granting mobility for users while also further challenging the paradigm of museum-driven works and art appreciation. The interactivity described in section 4 factors significantly into each of these projects, but also of importance are the social, economic, environmental, and political implications that factor in the design, development, and use of such works. Most of these projects are intended to bring about positive change, one way or another, by using locative media and by borrowing certain gaming mechanics for the purpose of engagement and interactivity. In fact, much of what is written about locative art is from fields within digital media studies on the media’s ‘playable’ qualities (avoiding the idea that artists are trying to merely gamify public spaces).

On the playable nature of locative art, Miguel Sicart says,

the data produced and used in smart cities should not necessarily be presented as a utility for citizens. It should be presented as a prop for play, as games but also as the source for toys and playgrounds. Data-rich cities can become playable cities, and, by becoming such, they can become more human, more inclusive spaces (Ackermann: 2016, 27).

Once again, the process-oriented and performative nature of locative works is central to appreciating the spaces they create. In connection with the playability of locative media, locative projects are also modifiable and typically intended to be hackable by the public in the communities where they are displayed. While the terms “hacker” and “hacking” may carry negative connotations, in its original conception, the practice of hacking was meant to improve upon existing computer programs, acknowledging the achievements of both the original creator and subsequent revisionists (Levy:1984). It is in this vein that locative projects are usually intended to change and improve over time given how users “play” with the data and inputs. In other words, local communities can play with these projects and even modify them, making locative works as relevant and reflective of the community as possible.

The above suggests that locative projects often have broader goals than mere entertainment. Although often intended to motivate play and playful attitudes, which, as indicated in the examples above can occur to varying degrees, the goal-oriented nature of locative works often makes the kind of play involved a “serious” kind. Serious play occurs when the enjoyment and pleasure that come from play do not just comprise entertainment but also serve some meritorious, real-world goal. A work can be said to support serious play even when users are not aware of the social or political goals of the work.

The customizable nature of locative media lends itself well to the altruistic aims of many locative artists. However, inclusivity, climate protection, social change, and any other desired effect of locative projects requires a given community to have sufficient funds for, access to, and user-knowledge about digital locative technology. This concern can also be understood, not just in terms of community requirements, but also in terms of technological requirements, for successful locative art. One way of putting it is as follows:

For any technological device to be “aware” of its context—physical or otherwise—it has to be able to locate, classify, collect, store, and use “relevant” information, as well as to identify and discard or ignore “irrelevant” information (Galloway & Ward 2005).

There are numerous political and economic factors affecting access to local and global spaces. With locative art, these factors are concerning for both ethical and artistic reasons.

- Ackermann, Judith, Andreas Rauscher, Andreas and Daniel Stein, 2016, Introduction: Playin’ the city. Artistic and Scientific Approaches to Playful Urban Arts . Navigationen-Zeitschrift für Medien-und Kulturwissenschaften, 16(1), pp.7-23.

- Atencia-Linares, Paloma and Marc Artiga, 2022, “Deepfakes, shallow graves: On the epistemic robustness of photography and videos in the era of deepfakes”, Synthese , 200, article 518.

- Binkley, Timothy, 1998, “Digital Media”, in Encyclopedia of Aesthetics , M. Kelly (ed.), New York: Oxford University Press.

- Blachowicz, James, 1997, “Analog Representation Beyond Mental Imagery”, Journal of Philosophy , 94(2): 55–84.

- Boden, Margaret A., 2010, Creativity and Art: Three Roads to Surprise , Oxford: Oxford University.

- Chalmers, David, 2017, “The Virtual and the Real”, Disputatio , 9(46): 309–352.

- Currie, Gregory, 1996, “Film, Reality, and Illusion”, in Post Theory: Reconstructing Film Studies , D. Bordwell and N. Carroll (eds.), Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 325–44.

- Davies, David, 2004, Art as Performance , Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- D’Cruz, Jason and P.D. Magnus, 2014, “Are Digital Images Allographic?” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism , 72(4): 417–27.

- Doane, Mary Ann, 2007, “Indexicality: Trace and Sign”, differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies , 18(1): 1–6.

- Dretske, Fred I., 1981, “Sensation and Perception”, in Knowledge and the Flow of Information , Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Electronic Disturbance Theater 2.0/b.a.n.g. lab, 2007-ongoing, “Transborder Immigrant Tool”, in Net Art Anthology [available online ].

- Galili, Doron, 2011, “The Post Medium Condition, circa 1895”, presented at the Second International Colloquium of the Permanent Seminar on the History of Film Theory: The Impact of Technological Innovations on the Theory and Historiography of Cinema, Montréal.

- Galloway, Anne and Matt Ward, 2005, “Locative Media as Socialising and Spatialising Practices: Learning from Archaeology”, Leonardo Electronic Almanac .

- Gaut, Berys, 2009, “Digital Cinema”, in The Routledge Companion to Philosophy and Film , P. Livingston and C. Plantinga (eds.), New York: Routledge, pp. 75–85.

- –––, 2010, A Philosophy of Cinematic Art , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gaut, Berys and Matthew Kieran (eds.), 2018, Creativity and Philosophy , New York: Oxford University Press.

- Goodman, Nelson, 1976, Languages of Art: An Approach to a Theory of Symbols , Indianapolis/Cambridge: Hackett Publishing Co.