Choose Your Test

- Search Blogs By Category

- College Admissions

- AP and IB Exams

- GPA and Coursework

The Best US History Regents Review Guide 2020

General Education

Taking US History in preparation for the Regents test? The next US History Regents exam dates are Wednesday, January 22nd and Thursday, June 18th, both at 9:15am. Will you be prepared?

You may have heard the test is undergoing some significant changes. In this guide, we explain everything you need to know about the newly-revised US History Regents exam, from what the format will look like to which topics it'll cover. We also include official sample questions of every question type you'll see on this test and break down exactly what your answers to each of them should include.

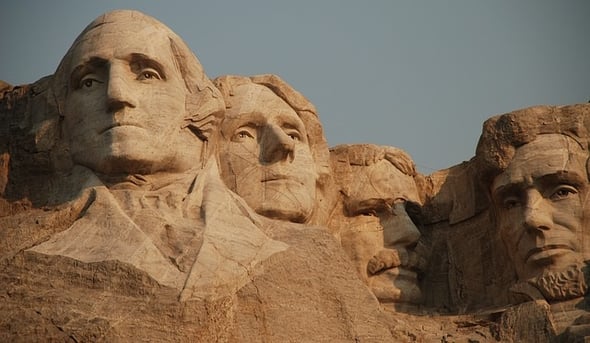

What Is the Format of the US History Regents Exam?

Beginning in 2020, the US History Regents exam will have a new format. Previously, the test consisted of 50 multiple-choice questions with long essays, but now it will have a mix of multiple choice, short answer, short essay, and long essay questions (schools can choose to use the old version of the exam through June 2021). Here's the format of the new test, along with how it's scored:

| 28 | Multiple choice | 1 | No | 28 | |

| 2 | Short essay | 5 | Yes | 10 | |

| 7 | 6 short answer 1 Civic Literacy essay | 1 per short answer, 5 for the essay | Only for the long essay | 11 | |

In Part 2, there will be two sets of paired documents (always primary sources). For each pair of documents, students will answer with a short essay (about two to three paragraphs, no introduction or conclusion).

For the first pair of documents, students will need to describe the historical context of the documents and explain how the two documents relate to each other. For the second pair, students will again describe the historical context of the documents then explain how audience, bias, purpose, or point of view affect the reliability of each document.

Part A: Students will be given a set of documents focused on a civil or constitutional issue, and they'll need to respond to a set of six short-answer questions about them.

Part B: Using the same set of documents as Part A, students will write a full-length essay (the Civic Literacy essay) that answers the following prompt:

- Describe the historical circumstances surrounding a constitutional or civic issue.

- Explain efforts by individuals, groups, and/or governments to address this constitutional or civic issue.

- Discuss the extent to which these efforts were successful OR discuss the impact of the efforts on the United States and/or American society.

What Topics Does the US History Regents Exam Cover?

Even though the format of the US History Regents test is changing, the topics the exam focuses on are pretty much staying the same. New Visions for Public Schools recommends teachers base their US History class around the following ten units:

As you can see, the US History Regents exam can cover pretty much any major topic/era/conflict in US History from the colonial period to present day, so make sure you have a good grasp of each topic during your US History Regents review.

What Will Questions Look Like on the US History Regents Exam?

Because the US History Regents exam is being revamped for 2020, all the old released exams (with answer explanations) are out-of-date. They can still be useful study tools, but you'll need to remember that they won't be the same as the test you'll be taking.

Fortunately, the New York State Education Department has released a partial sample exam so you can see what the new version of the US History Regents exam will be like. In this section, we go over a sample question for each of the four question types you'll see on the test and explain how to answer it.

Multiple-Choice Sample Question

Base your answers to questions 1 through 3 on the letter below and on your knowledge of social studies.

| . . . For myself, I was escorted through Packingtown by a young lawyer who was brought up in the district, had worked as a boy in Armour's plant, and knew more or less intimately every foreman, "spotter," and watchman about the place. I saw with my own eyes hams, which had spoiled in pickle, being pumped full of chemicals to destroy the odor. I saw waste ends of smoked beef stored in barrels in a cellar, in a condition of filth which I could not describe in a letter. I saw rooms in which sausage meat was stored, with poisoned rats lying about, and the dung of rats covering them. I saw hogs which had died of cholera in shipment, being loaded into box cars to be taken to a place called Globe, in Indiana, to be rendered into lard. Finally, I found a physician, Dr. William K. Jaques, 4316 Woodland avenue, Chicago, who holds the chair of bacteriology in the Illinois State University, and was in charge of the city inspection of meat during 1902-3, who told me he had seen beef carcasses, bearing the inspectors' tags of condemnation, left upon open platforms and carted away at night, to be sold in the city. . . . — Letter from Upton Sinclair to President Theodore Roosevelt, March 10, 1906 |

- Upton Sinclair wrote this letter to President Theodore Roosevelt to inform the president about

1. excessive federal regulation of meatpacking plants 2. unhealthy practices in the meatpacking plants 3. raising wages for meatpacking workers 4. state laws regulating the meatpacking industry

There will be 28 multiple-choice questions on the exam, and they'll all reference "stimuli" such as this example's excerpt of a letter from Upton Sinclair to Theodore Roosevelt. This means you'll never need to pull an answer out of thin air (you'll always have information from the stimulus to refer to), but you will still need a solid knowledge of US history to do well.

To answer these questions, first read the stimulus carefully but still efficiently. In this example, Sinclair is describing a place called "Packingtown," and it seems to be pretty gross. He mentions rotting meat, dead rats, infected animals, etc.

Once you have a solid idea of what the stimulus is about, read the answer choices (some students may prefer to read through the answer choices before reading the stimulus; try both to see which you prefer).

Option 1 doesn't seem correct because there definitely doesn't seem to be much regulation occurring in the meatpacking plant. Option 2 seems possible because things do seem very unhealthy there. Option 3 is incorrect because Sinclair mentions nothing about wages, and similarly for option 4, there is nothing about state laws in the letter.

Option 2 is the correct answer. Because of the stimulus (the letter), you don't need to know everything about the history of industrialization in the US and how its rampant growth had the tendency to cause serious health/social/moral etc. problems, but having an overview of it at least can help you answer questions like these faster and with more confidence.

Short Essay

This Short Essay Question is based on the accompanying documents and is designed to test your ability to work with historical documents. Each Short Essay Question set will consist of two documents. Some of these documents have been edited for the purposes of this question. Keep in mind that the language and images used in a document may reflect the historical context of the time in which it was created.

Task: Read and analyze the following documents, applying your social studies knowledge and skills to write a short essay of two or three paragraphs in which you:

| between the events and/or ideas found in these documents (Cause and Effect, Similarity/Difference, Turning Point) |

In developing your short essay answer of two or three paragraphs, be sure to keep these explanations in mind:

Describe means "to illustrate something in words or tell about it"

Historical Context refers to "the relevant historical circumstances surrounding or connecting the events, ideas, or developments in these documents"

Identify means "to put a name to or to name"

Explain means "to make plain or understandable; to give reasons for or causes of; to show the logical development or relationship of"

Types of Relationships :

Cause refers to "something that contributes to the occurrence of an event, the rise of an idea, or the bringing about of a development"

Effect refers to "what happens as a consequence (result, impact, outcome) of an event, an idea, or a development"

Similarity tells how "something is alike or the same as something else"

Difference tells how "something is not alike or not the same as something else"

Turning Point is "a major event, idea, or historical development that brings about significant change. It can be local, regional, national, or global"

| Mr. President, would you mind commenting on the strategic importance of Indochina for the free world? I think there has been, across the country, some lack of understanding on just what it means to us. You have, of course, both the specific and the general when you talk about such things. First of all, you have the specific value of a locality in its production of materials that the world needs. Then you have the possibility that many human beings pass under a dictatorship that is inimical [hostile] to the free world. Finally, you have broader considerations that might follow what you would call the "falling domino" principle. You have a row of dominoes set up, you knock over the first one, and what will happen to the last one is the certainty that it will go over very quickly. So you could have a beginning of a disintegration that would have the most profound influences. . . . |

| Source: Press Conference with President Dwight Eisenhower, April 7, 1954 |

| Joint Resolution To promote the maintenance of international peace and security in southeast Asia. Whereas naval units of the Communist regime in Vietnam, in violation of the principles of the Charter of the United Nations and of international law, have deliberately and repeatedly attacked United States naval vessels lawfully present in international waters, and have thereby created a serious threat to international peace; and Whereas these attackers are part of deliberate and systematic campaign of aggression that the Communist regime in North Vietnam has been waging against its neighbors and the nations joined with them in the collective defense of their freedom; and Whereas the United States is assisting the peoples of southeast Asia to protest their freedom and has no territorial, military or political ambitions in that area, but desires only that these people should be left in peace to work out their destinies in their own way: Now, therefore be it , That the Congress approves and supports the determination of the President, as Commander in Chief, to take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression. . . . |

| Source: Tonkin Gulf Resolution in Congress, August 7, 1964 |

It's important to read the instructions accompanying the documents so you know exactly how to answer the short essays. This example is from the first short essay question, so along with explaining the historical context of the documents, you'll also need to explain the relationship between the documents (for the second short essay question, you'll need to explain biases). Your options for the types of relationships are:

- cause and effect,

- similarity/difference

- turning point

You'll only choose one of these relationships. Key words are explained in the instructions, which we recommend you read through carefully now so you don't waste time doing it on test day. The instructions above are the exact instructions you'll see on your own exam.

Next, read through the two documents, jotting down some brief notes if you like. Document 1 is an excerpt from a press conference where President Eisenhower discusses the importance of Indochina, namely the goods it produces, the danger of a dictatorship to the free world, and the potential of Indochina causing other countries in the region to become communist as well.

Document 2 is an excerpt from the Tonkin Gulf Resolution. It mentions an attack on the US Navy by the communist regime in Vietnam, and it states that while the US desires that there be peace in the region and is reluctant to get involved, Congress approves the President of the United States to "take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States and to prevent further aggression."

Your response should be no more than three paragraphs. For the first paragraph, we recommend discussing the historical context of the two documents. This is where your history knowledge comes in. If you have a strong grasp of the history of this time period, you can discuss how France's colonial reign in Indochina (present-day Vietnam) ended in 1954, which led to a communist regime in the north and a pro-Western democracy in the south. Eisenhower didn't want to get directly involved in Vietnam, but he subscribed to the "domino theory" (Document 1) and believed that if Vietnam became fully communist, other countries in Southeast Asia would as well. Therefore, he supplied the south with money and weapons, which helped cause the outbreak of the Vietnam War.

After Eisenhower, the US had limited involvement in the Vietnam War, but the Gulf of Tonkin incident, where US and North Vietnam ships confronted each other and exchanged fire, led to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution (Document 2) and gave President Lyndon B. Johnson powers to send US military forces to Vietnam without an official declaration of war. This led to a large escalation of the US's involvement in Vietnam.

You don't need to know every detail mentioned above, but having a solid knowledge of key US events (like its involvement in the Vietnam War) will help you place documents in their correct historical context.

For the next one to two paragraphs of your response, discuss the relationship of the documents. It's not really a cause and effect relationship, since it wasn't Eisenhower's domino theory that led directly to the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, but you could discuss the similarities and differences between the two documents (they're similar because they both show a fear of the entire region becoming communist and a US desire for peace in the area, but they're different because the first is a much more hands-off approach while the second shows significant involvement). You could also argue it's a turning point relationship because the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution was the turning point in the US's involvement in the Vietnam War. Up to that point, the US was primarily hands-off (as shown in Document 1). Typically, the relationship you choose is less important than your ability to support your argument with facts and analysis.

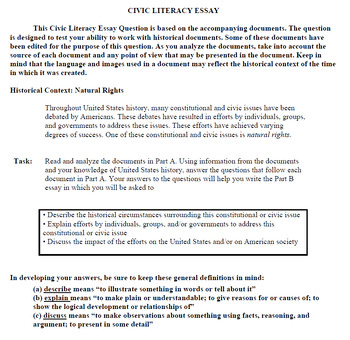

Short Answers and Civic Literacy Essay

This Civic Literacy essay is based on the accompanying documents. The question is designed to test your ability to work with historical documents. Some of these documents have been edited for the purpose of this question. As you analyze the documents, take into account the source of each document and any point of view that may be presented in the document. Keep in mind that the language and images used in a document may reflect the historical context of the time in which it was created.

Historical Context: African American Civil Rights

Throughout United States history, many constitutional and civic issues have been debated by Americans. These debates have resulted in efforts by individuals, groups, and governments to address these issues. These efforts have achieved varying degrees of success. One of these constitutional and civic issues is African American civil rights.

Task: Read and analyze the documents. Using information from the documents and your knowledge of United States history, write an essay in which you

Discuss means "to make observations about something using facts, reasoning, and argument; to present in some detail"

Document 1a

| . . . Before the Civil War, blacks could vote in only a handful of northern states, and black officeholding was virtually unheard of. (The first African American to hold elective office appears to have been John M. Langston, chosen as township clerk in Brownhelm, Ohio, in 1855.) But during Reconstruction perhaps two thousand African Americans held public office, from justice of the peace to governor and United States senator. Thousands more headed Union Leagues and local branches of the Republican Party, edited newspapers, and in other ways influenced the political process. African Americans did not "control" Reconstruction politics, as their opponents frequently charged. But the advent of black suffrage and officeholding after the war represented a fundamental shift in power in southern life. It marked the culmination of both the constitutional revolution embodied in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth amendments, and the broad grassroots mobilization of the black community. . . . |

| Source: Eric Foner, Forever Free: The Story of Emancipation and Reconstruction, Alfred A. Knopf, 2005 |

Document 1b

| . . . Although 1890 to 2000 is a relatively short span of time, these eleven decades comprise a critical period in American history. The collapse of Reconstruction after the Civil War led to the establishment of white supremacy in the Southern states, a system of domination and exploitation that most whites, in the North as well as the South, expected to last indefinitely. In 1900, despite the nation's formal commitment to racial equality as expressed in the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, racial discrimination remained a basic organizing principle of American society. In the South, racial discrimination, reinforced by racial segregation, became official state policy. In the North discrimination and segregation also became widely sanctioned customs that amounted to, in effect, semiofficial policy. The federal government practiced racial segregation in the armed services, discriminated against blacks in the civil service, and generally condoned, by its actions if not its words, white supremacy. . . . |

| Source: Adam Fairclough, Better Day Coming: Blacks and Equality 1890–2000, Viking, 2001 |

- Based on these documents, state one way the end of Reconstruction affected African Americans.

| . . . By 1905 those African Americans who stayed in the former Confederacy found themselves virtually banished from local elections, but that didn't mean that they weren't political actors. In his famous 1895 Atlanta Exposition speech, Tuskegee College president Booker T. Washington recommended vocational training rather than classical education for African Americans. The former slave implied that black southerners would not seek social integration, but he did demand that southern factories hire black people: "The opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera-house." He looked forward to the near future when the African American third of the southern population would produce and share in one-third of its industrial bounty. . . . The northern-born black sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois positioned himself as Washington's nemesis [opponent]. A graduate of Tennessee's Fisk University, Du Bois was the first African American to earn a Harvard Ph.D. He believed that Washington had conceded too much and said so in his 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk. Any man, he insisted, should be able to have a classical education. Moreover, accepting segregation meant abdicating all civil rights by acknowledging that black people were not equal to whites. "The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line." Du Bois warned. In 1905 he founded the Niagara Movement, the forerunner of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), which was begun in 1909 to fight for political and civil rights. . . . |

| Source: Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore & Thomas J. Sugrue, These United States: A Nation in the Making 1890 to the Present, W. W. Norton & Company, 2015 |

- According to this document, what is one way Booker T. Washington and W. E. B. Du Bois disagreed about how African Americans should achieve equality?

| . . . In 1950 Reverend Oliver Brown of Topeka, Kansas, was incensed that his young daughters could not attend the Sumner Elementary School, an all-white public school close to their home. Instead, they had to walk nearly a mile through a dangerous railroad switchyard to reach a bus that would take them to an inferior all-black school. In the early 1950s, this sort of school segregation was commonplace in the South and certain border states. By law, all-black schools (and other segregated public facilities) were supposed to be as well-funded as whites'—but they rarely were. States typically spent twice as much money per student in white schools. Classrooms in black schools were overcrowded and dilapidated. In 1951 NAACP lead counsel Thurgood Marshall filed suit on behalf of Oliver Brown. By fall 1952, the Brown case and four other school desegregation cases had made their way to the U.S. Supreme Court, all under the case name Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka. Marshall argued that the Supreme Court should overturn the "separate but equal" ruling of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which had legitimized segregation. Marshall believed that even if states spent an equal amount of money on black schools, the segregated system would still be unfair because the stigma of segregation damaged black students psychologically. . . . |

| Source: Beth Bailey, et al, The Fifties Chronicles, Legacy, 2008 |

- According to this document, what is one reason Thurgood Marshall argued that the "separate but equal" ruling of Plessy v. Ferguson should be overturned?

Document 4a

|

|

| Source: Greensboro News & Record, February 2, 1960 |

Document 4b

| . . . At lunch counters in other cities, protesters encountered hostile reactions from outraged white patrons. Sit-in demonstrators were assaulted with verbal abuse, hot coffee, lit cigarettes, and worse. Invariably, it was the young protesters who ended up arrested for "creating a disturbance." Nevertheless, by fall 1961 the movement could claim substantial victories among many targeted cities. . . . |

| Source: David Farber, et al, The Sixties Chronicles, Legacy, 2004 |

- Based on these documents, state one result of the sit-in at the Greensboro Woolworth.

| . . . The direct action protests of the 1960s paid dividends. In 1964 and 1965, the Johnson administration orchestrated the passing of the two most significant civil rights bills since Reconstruction. The Birmingham protests and the March on Washington had convinced President Kennedy to forge ahead with a civil rights bill in 1963. But his assassination on November 22, 1963, left the passage of the bill in question. President Johnson, who to that point had an unfavorable record concerning civil rights, had come to believe in the importance of federal protection for African Americans and deftly tied the civil rights bill to the memory of Kennedy. . . . Despite passage of this far-reaching bill, African Americans still faced barriers to their right to vote. While the Civil Rights Act of 1964 addressed voting rights, it did not eliminate many of the tactics recalcitrant [stubborn] southerners used to keep blacks from the polls, such as violence, economic intimidation, and literacy tests. But the Freedom Summer protests in Mississippi and the Selma-to-Montgomery march the following year led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Johnson had already begun work on a bill before the Selma march, and he again urged Congress to pass it. On March 15, 1965, he addressed both houses of Congress. . . . |

| Source: Henry Louis Gates Jr., 1513–2008, Alfred A. Knopf, 2011 |

- According to Henry Louis Gates Jr., what was one result of the 1960s civil rights protests?

| . . . When the clock ticked off the last minute of 1969 and African Americans took stock of the last few years, they thought not only about the changes they had witnessed but also about the ones they still hoped to see. They knew they were the caretakers of King's dream of living in a nation where character was more important than color. And they knew they had to take charge of their community. After all, the civil rights and Black Power eras had forged change through community action. Although many blacks may have sensed that all progress was tempered by the social, economic, and political realities of a government and a white public often resistant to change, they could not ignore the power of their own past actions. America in 1969 was not the America of 1960 or 1965. At the end of the decade, a chorus could be heard rising from the black community proclaiming, "We changed the world.". . . . |

| Source: Robin D. G. Kelley and Earl Lewis, eds., To Make our World Anew: Vol. Two: A History of African Americans Since 1880, Oxford University Press, 2000 |

- Based on this document, state one impact of the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

Start by reading the instructions, then the documents themselves. There are eight of them, all focused on African American civil rights. The short answers and the civic literacy essay use the same documents. We recommend answering the short answer questions first, then completing your essay.

A short answer question follows each document or set of documents. These are straightforward questions than can be answered in 1-2 sentences. Question 1 asks, "Based on these documents, state one way the end of Reconstruction affected African Americans."

Reading through documents 1a and 1b, there are many potential answers. Choose one (don't try to choose more than one to get more points; it won't help and you'll just lose time you could be spending on other questions) for your response. Using information from document 1a, a potential answer could be, "After Reconstruction, African Americans were able to hold many elected positions. This made it possible for them to influence politics and public life more than they had ever been able to before."

Your Civic Literacy essay will be a standard five-paragraph essay, with an introduction, thesis statement, and a conclusion. You'll need to use many of the documents to answer the three bullet points laid out in the instructions. We recommend one paragraph per bullet point. For each paragraph, you'll need to use your knowledge of US history AND information directly from the documents to make your case.

As with the short essay, we recommended devoting a paragraph to each of the bullet points. In the first paragraph, you should discuss how the documents fit into the larger narrative of African American civil rights. You could discuss the effects of Reconstruction, how the industrialization of the North affected blacks, segregation and its impacts, key events in the Civil Rights movement such as the bus boycott in Montgomery and the March on Washington, etc. The key is to use your own knowledge of US history while also discussing the documents and how they tie in.

For the second paragraph, you'll discuss efforts to address African American civil rights. Here you can talk about groups, such as the NAACP (Document 3), specific people such as W.E.B. Du Bois (Document 2), and/or major events, such as the passing of the Civil Rights Act (Document 5).

In the third paragraph, you'll discuss how successful the effort to increase African American civil rights was. Again, use both the documents and your own knowledge to discuss setbacks faced and victories achieved. Your overall opinion will reflect your thesis statement you included at the end of your introductory paragraph. As with the other essays, it matters less what you conclude than how well you are able to support your argument.

3 Tips for Your US History Regents Review

In order to earn a Regents Diploma, you'll need to pass at least one of the social science regents. Here are some tips for passing the US Regents exam.

#1: Focus on Broad Themes, Not Tiny Details

With the revamp of the US History exam, there is much less focus on memorization and basic fact recall. Every question on the exam, including multiple choice, will have a document or excerpt referred to in the questions, so you'll never need to pull an answer out of thin air.

Because you'll never see a question like, "What year did Alabama become a state?" don't waste your time trying to memorize a lot of dates. It's good to have a general idea of when key events occurred, like WWII or the Gilded Age, but i t's much more important that you understand, say, the causes and consequences of WWII rather than the dates of specific battles. The exam tests your knowledge of major themes and changes in US history, so focus on that during your US History Regents review over rote memorization.

#2: Don't Write More Than You Need To

You only need to write one full-length essay for the US History Regents exam, and it's for the final question of the test (the Civic Literacy essay). All other questions (besides multiple choice) only require a few sentences or a few paragraphs.

Don't be tempted to go beyond these guidelines in an attempt to get more points. If a question asks for one example, only give one example; giving more won't get you any additional points, and it'll cause you to lose valuable time. For the two short essay questions, only write three paragraphs each, maximum. The short response questions only require a sentence or two. The questions are carefully designed so that they can be fully answered by responses of this length, so don't feel pressured to write more in an attempt to get a higher score. Quality is much more important than quantity here.

#3: Search the Documents for Clues

As mentioned above, all questions on this test are document-based, and those documents will hold lots of key information in them. Even ones that at first glance don't seem to show a lot, like a poster or photograph, can contain many key details if you have a general idea of what was going on at that point in history. The caption or explanation beneath each document is also often critical to fully understanding it. In your essays and short answers, remember to always refer back to the information you get from these documents to help support your answers.

What's Next?

Taking other Regents exams ? We have guides to the Chemistry , Earth Science , and Living Environment Regents , as well as the Algebra 1 , Algebra 2 , and Geometry Regents .

Need more information on Colonial America? Become an expert by reading our guide to the 13 colonies.

The Platt Amendment was written during another key time in American history. Learn all about this important document, and how it is still influencing Guantanamo Bay, by reading our complete guide to the Platt Amendment .

Trending Now

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

ACT vs. SAT: Which Test Should You Take?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Get Your Free

Find Your Target SAT Score

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect SAT Score, by an Expert Full Scorer

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading and Writing

How to Improve Your Low SAT Score

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading and Writing

Find Your Target ACT Score

Complete Official Free ACT Practice Tests

How to Get a Perfect ACT Score, by a 36 Full Scorer

Get a 36 on ACT English

Get a 36 on ACT Math

Get a 36 on ACT Reading

Get a 36 on ACT Science

How to Improve Your Low ACT Score

Get a 24 on ACT English

Get a 24 on ACT Math

Get a 24 on ACT Reading

Get a 24 on ACT Science

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

- Board of Regents

- Business Portal

- Contact NYSED

New York State Education Department

- Commissioner

- USNY Affiliates

- Organization Chart

- Building Tours

- Program Offices

- Rules & Regulations

- Office of Counsel

- Office of State Review

- Freedom of Information (FOIL)

- Governmental Relations

- Adult Education

- Bilingual Education & World Languages

- Career & Technical Education

- Cultural Education

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Early Learning

- Educator Quality

- Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)

- Graduation Measures

- Higher Education

- High School Equivalency

- Indigenous Education

- My Brother's Keeper

Office of the Professions

- P-12 Education

- Special Education

- Vocational Rehabilitation

- Career and Technical Education

- Educational Design and Technology

- Standards and Instruction

- Office of State Assessment

- Computer-Based Testing

- Exam Schedules

- Grades 3-8 Tests

- Regents Exams

- New York State Alternate Assessment (NYSAA)

- English as a Second Language Tests

- Test Security

- Teaching Assistants

- Pupil Personnel Services Staff

- School Administrators

- Professionals

- Career Schools

- Fingerprinting

- Accountability

- Audit Services

- Budget Coordination

- Chief Financial Office

- Child Nutrition

- Facilities Planning

- Ed Management Services

- Pupil Transportation Services

- Religious and Independent School Support

- SEDREF Query

- Public Data

- Data Privacy and Security

- Information & Reporting

High School Regents Examinations

- August 2024 Examinations General Information

- Past Regents Examinations

- Archive: Regents Examination Schedules

- High School Administrator's Manual

- January 2024 Regents Examination Scoring Information

- June 2024 Regents Examination Scoring Information

- Testing Materials for Duplication by Schools

- English Language Arts

- Next Generation Algebra I Reference Sheet

- Life Science: Biology

- Earth and Space Sciences

- Science Reference Tables (1996 Learning Standards)

United States History and Government

- Global History and Geography II

- High School Field Testing

- Test Guides and Samplers

- Technical Information and Reports

General Information

- Information Booklet for Scoring the Regents Examination in United States History and Government

- Frequently Asked Questions on Cancellation of Regents Examination in United States History and Government - Revised, 6/17/22

- Cancellation of the Regents Examination in United States History and Government for June 2022

- Educator Guide to the Regents Examination in United States History and Government - Updated, July 2023

- Memo: January 2022 Regents Examination in United States History and Government Diploma Requirement Exemption

- Timeline for Regents Examination in United States History and Government and Regents Examination in United States History and Government

- Regents Examination in United States History and Government Essay Booklet - For June 2023 and beyond

- Prototypes for Regents Examination in United States History and Government

- Regents Examination in United States History and Government Test Design - Updated, 3/4/19

- Performance Level Descriptors (PLDs) for United States History and Government

Part 1: Multiple-Choice Questions

- Part I: Task Models for Stimulus Based Multiple-Choice Question

Part II: Stimulus-Based Short Essay Questions: Sample Student Papers

The links below lead to sample student papers for the Part II Stimulus-Based Short Essay Questions for both Set 1 and Set 2. They include an anchor paper and a practice paper at each score point on a 5-point rubric. These materials were created to provide further understanding of the Part II Stimulus-Based Short Essay Questions and rubrics for scoring actual student papers. Each set includes Scoring Worksheets A and B, which can be used for training in conjunction with the practice papers. The 5-point scoring rubric has been specifically designed for use with these Stimulus-Based Short Essay Questions.

Part III: Civic Literacy Essay Question

The link below leads to sample student papers for the Part III Civic Literacy Essay Question. It includes Part IIIA and Part IIIB of a new Civic Literacy Essay Question along with rubrics for both parts and an anchor paper and practice paper at each score point on a 5-point rubric. These materials were created to provide further understanding of the Part III Civic Literacy Essay Question and rubric for scoring actual student papers. Also included are Scoring Worksheets A and B, which can be used for training in conjunction with the practice papers. The 5-point scoring rubric is the same rubric used to score the Document-Based Question essay on the current United States History and Government Regents Examination.

- Part III: Civic Literacy Essay Question Sample Student Papers

Get the Latest Updates!

Subscribe to receive news and updates from the New York State Education Department.

Popular Topics

- Charter Schools

- High School Equivalency Test

- Next Generation Learning Standards

- Professional Licenses & Certification

- Reports & Data

- School Climate

- School Report Cards

- Teacher Certification

- Vocational Services

- Find a school report card

- Find assessment results

- Find high school graduation rates

- Find information about grants

- Get information about learning standards

- Get information about my teacher certification

- Obtain vocational services

- Serve legal papers

- Verify a licensed professional

- File an appeal to the Commissioner

Quick Links

- About the New York State Education Department

- About the University of the State of New York (USNY)

- Business Portal for School Administrators

- Employment Opportunities

- FOIL (Freedom of Information Law)

- Incorporation for Education Corporations

- NYS Archives

- NYS Library

- NYSED Online Services

- Public Broadcasting

Media Center

- Newsletters

- Video Gallery

- X (Formerly Twitter)

New York State Education Building

89 Washington Avenue

Albany, NY 12234

NYSED General Information: (518) 474-3852

ACCES-VR: 1-800-222-JOBS (5627)

High School Equivalency: (518) 474-5906

New York State Archives: (518) 474-6926

New York State Library: (518) 474-5355

New York State Museum: (518) 474-5877

Office of Higher Education: (518) 486-3633

Office of the Professions: (518) 474-3817

P-12 Education: (518) 474-3862

EMAIL CONTACTS

Adult Education & Vocational Services

New York State Archives

New York State Library

New York State Museum

Office of Higher Education

Office of Education Policy (P-20)

© 2015 - 2024 New York State Education Department

Diversity & Access | Accessibility | Internet Privacy Policy | Disclaimer | Terms of Use

Ida B. Wells and the Campaign against Lynching

Written by: bill of rights institute, by the end of this section, you will:.

- Explain how various factors contributed to continuity and change in the “New South” from 1877 to 1898

Suggested Sequencing

Use this Narrative with the Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) Narrative and the Ida B. Wells, “Lynch Law,” 1893. Primary Source to have students discuss the issues that African Americans faced after Reconstruction and through the beginning of the twentieth century.

In March 1892, trouble erupted in Memphis, Tennessee. That spring was supposed to bring a celebratory mood to the city that had just built the first bridge across the Mississippi south of the Ohio River. The bridge was intended to attract a railroad and enhance commerce. Instead, the city plunged into a violent racial episode that represented the realities of the lives of African Americans living in the segregated South.

A racially mixed group of boys was gambling at a local general store for white patrons when tensions flared and a father of one of the white boys whipped a black child. The owner of the general store, W.H. Barrett, went to a nearby competing grocery and violently confronted an African American clerk named Calvin McDowell and pistol-whipped him. McDowell fought back and bloodied Barrett. As a result, a white judge issued an arrest warrant for McDowell.

Deputies led a white mob to serve the warrant and confronted a large band of armed black men at the grocery store. Shots were fired and three deputies and some of the civilians were wounded in the exchange of gunfire. The deputies took a dozen African Americans into custody. Angry whites went on a rampage and rounded up dozens more African American men while ransacking their homes.

Because of the common practice in the South of white mobs seizing black men in jail and murdering them, the African American Tennessee Rifles state militia company surrounded the jail. They had to depart, however, when a white judge ordered them disarmed. The black men in the jail were left defenseless.

In the middle of the night, a white mob descended upon the jail and dragged out McDowell and two other black men named Thomas Moss and Will Stewart. All three were taken to a field where they were shot. Their bodies were mutilated and they were left to rot. Because African Americans did not enjoy due process of law or equal justice in the south, no indictments were issued for the murders.

Among the outraged African Americans who lived in Memphis at the time was journalist Ida B. Wells, who was in New York when the murders occurred. She had been born a slave in 1862 during the Civil War, and afterward her family became active in the Republican Party and the Freedman’s Aid Society. Wells was known for standing up to the humiliations of segregation.

Ida B. Wells was a pioneer in the fight for African American civil rights. The photo is from about 1893.

In May 1884, Wells had boarded a train to Nashville with a first-class ticket, but she was told that she had to sit in the car reserved for African Americans. She refused and was forcibly removed from the train. She took her case to court, winning $500 before the Tennessee Supreme Court overturned the verdict. After this ordeal, she began to write about the discrimination and racism that African Americans faced. She also began to speak out against the deplorable conditions of the segregated school where she taught, resulting in her losing her job.

Wells had been a close friend of Tom Moss and was infuriated by the senseless murders. When she returned to Memphis, she penned an inflammatory editorial in the local newspaper, the Free Press , that confronted whites directly about lynching. She described ten lynchings that had taken place that week across the South in Arkansas, Alabama, Georgia, and Louisiana. In the editorial, she wrote, “This is what opened my eyes to what lynching really was: an excuse to get rid of Negroes who were acquiring wealth and property and thus keep the race terrorized.”

Lynching had most often occurred in the West because some places lacked the protections of law and order, so mobs sometimes resorted to violence. The practice became widespread in the South in the 1890s, with between 80 and 160 African Americans lynched annually. White mobs often accused black men of raping white women and then proceeded to torture, hang, castrate, burn, and dismember the accused. Lynchings became public spectacles, with local whites forming large crowds to watch the brutality. Many whites believed these gruesome murders preserved the social order even as they grossly violated the natural and constitutional rights of African Americans.

Wells’s editorial made her a target of a white mob that destroyed the press and threatened her, forcing her to flee to New York City. She launched a campaign to publicize the horrors of lynching and began writing and lecturing about it across the country. She wrote two pamphlets, entitled A Red Record: Lynchings in the United States and Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases . In those works, she catalogued 241 lynchings. She exploded the myth that lynchings were carried out in retribution for black men’ raping white women, because the overwhelming majority of sexual relationships were consensual or merely a product of fear in white imaginations. She asserted that lynching was “that last relic of barbarism and slavery.”

Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness

In our resource history is presented through a series of narratives, primary sources, and point-counterpoint debates that invites students to participate in the ongoing conversation about the American experiment.

Civic Literacy Essay Natural Civil Rights US History 1

Description

NYS US History Regents Style Civic Literacy on Natural Rights / Civil Rights

Includes primary source documents and accompanying questions concerning the following topics:

1. John Locke and natural rights

2. Treatment of Native Americans

3. Colonial taxes/Boston Tea Party

4. Women's suffrage

5. Thurgood Marshal and civil rights

Questions & Answers

- We're hiring

- Help & FAQ

- Privacy policy

- Student privacy

- Terms of service

- Tell us what you think

- Student Opportunities

About Hoover

Located on the campus of Stanford University and in Washington, DC, the Hoover Institution is the nation’s preeminent research center dedicated to generating policy ideas that promote economic prosperity, national security, and democratic governance.

- The Hoover Story

- Hoover Timeline & History

- Mission Statement

- Vision of the Institution Today

- Key Focus Areas

- About our Fellows

- Research Programs

- Annual Reports

- Hoover in DC

- Fellowship Opportunities

- Visit Hoover

- David and Joan Traitel Building & Rental Information

- Newsletter Subscriptions

- Connect With Us

Hoover scholars form the Institution’s core and create breakthrough ideas aligned with our mission and ideals. What sets Hoover apart from all other policy organizations is its status as a center of scholarly excellence, its locus as a forum of scholarly discussion of public policy, and its ability to bring the conclusions of this scholarship to a public audience.

- Peter Berkowitz

- Ross Levine

- Michael McFaul

- Timothy Garton Ash

- China's Global Sharp Power Project

- Economic Policy Group

- History Working Group

- Hoover Education Success Initiative

- National Security Task Force

- National Security, Technology & Law Working Group

- Middle East and the Islamic World Working Group

- Military History/Contemporary Conflict Working Group

- Renewing Indigenous Economies Project

- State & Local Governance

- Strengthening US-India Relations

- Technology, Economics, and Governance Working Group

- Taiwan in the Indo-Pacific Region

Books by Hoover Fellows

Economics Working Papers

Hoover Education Success Initiative | The Papers

- Hoover Fellows Program

- National Fellows Program

- Student Fellowship Program

- Veteran Fellowship Program

- Congressional Fellowship Program

- Media Fellowship Program

- Silas Palmer Fellowship

- Economic Fellowship Program

Throughout our over one-hundred-year history, our work has directly led to policies that have produced greater freedom, democracy, and opportunity in the United States and the world.

- Determining America’s Role in the World

- Answering Challenges to Advanced Economies

- Empowering State and Local Governance

- Revitalizing History

- Confronting and Competing with China

- Revitalizing American Institutions

- Reforming K-12 Education

- Understanding Public Opinion

- Understanding the Effects of Technology on Economics and Governance

- Energy & Environment

- Health Care

- Immigration

- International Affairs

- Key Countries / Regions

- Law & Policy

- Politics & Public Opinion

- Science & Technology

- Security & Defense

- State & Local

- Books by Fellows

- Published Works by Fellows

- Working Papers

- Congressional Testimony

- Hoover Press

- PERIODICALS

- The Caravan

- China's Global Sharp Power

- Economic Policy

- History Lab

- Hoover Education

- Global Policy & Strategy

- Middle East and the Islamic World

- Military History & Contemporary Conflict

- Renewing Indigenous Economies

- State and Local Governance

- Technology, Economics, and Governance

Hoover scholars offer analysis of current policy challenges and provide solutions on how America can advance freedom, peace, and prosperity.

- China Global Sharp Power Weekly Alert

- Email newsletters

- Hoover Daily Report

- Subscription to Email Alerts

- Periodicals

- California on Your Mind

- Defining Ideas

- Hoover Digest

- Video Series

- Uncommon Knowledge

- Battlegrounds

- GoodFellows

- Hoover Events

- Capital Conversations

- Hoover Book Club

- AUDIO PODCASTS

- Matters of Policy & Politics

- Economics, Applied

- Free Speech Unmuted

- Secrets of Statecraft

- Capitalism and Freedom in the 21st Century

- Libertarian

- Library & Archives

Support Hoover

Learn more about joining the community of supporters and scholars working together to advance Hoover’s mission and values.

What is MyHoover?

MyHoover delivers a personalized experience at Hoover.org . In a few easy steps, create an account and receive the most recent analysis from Hoover fellows tailored to your specific policy interests.

Watch this video for an overview of MyHoover.

Log In to MyHoover

Forgot Password

Don't have an account? Sign up

Have questions? Contact us

- Support the Mission of the Hoover Institution

- Subscribe to the Hoover Daily Report

- Follow Hoover on Social Media

Make a Gift

Your gift helps advance ideas that promote a free society.

- About Hoover Institution

- Meet Our Fellows

- Focus Areas

- Research Teams

- Library & Archives

Library & archives

Events, news & press.

Birmingham, 1963: Three Witnesses to the Struggle for Civil Rights

Mary Bush, Freeman Hrabowski, and Condoleezza Rice grew up and were classmates together in segregated Birmingham, Alabama, in the late 1950s and early ’60s. We reunited them for a conversation in Birmingham’s Westminster Presbyterian Church, where Rice’s father was pastor during that period.

Birmingham, 1963: Three Witnesses To The Struggle For Civil Rights

Mary Bush, Freeman Hrabowski, and Condoleezza Rice grew up and were classmates together in segregated Birmingham, Alabama, in the late 1950s and early ’60s. We reunited them for a conversation in Birmingham’s Westminster Presbyterian Church, where Rice’s father was pastor during that period. The three lifelong friends recount what life was like for Blacks in Jim Crow Alabama and the deep bonds that formed in the Black community at the time in order to support one another and to give the children a good education. They also recall the events they saw—and in some cases participated in—during the spring, summer, and fall of 1963, when Birmingham was racked with racial violence, witnessed marches and protests led by Dr. Martin Luther King, and was shocked by the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church. The latter event resulted in the deaths of four little girls, whom all three knew. The show concludes with a visit to a statue of Martin Luther King Jr. erected in Kelly Ingram Park—where in 1963 Birmingham’s commissioner for public safety Bull Connor ordered that fire hoses and attack dogs be used on protestors. There, Condoleezza Rice discusses Dr. King’s legacy and his impact on her life.

To view the full transcript of this episode, read below:

Peter Robinson: In Birmingham, Alabama, 60 years ago, black students, some still in elementary school, marched for an end to segregation. They were met with police dogs, fire hoses, and handcuffs. Today, three people who can remember those events because they themselves were students right here in Birmingham. Businesswoman, Mary Bush, University President, Freeman Hrabowski, and former Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice. On Uncommon Knowledge now.

- [George Corley Wallace] And so my friends, they did not die in vain. God still has a way of ringing good out of evil, and history has proven over and over again that unmerited suffering is redemptive. ♪ Freedom ♪ ♪ Freedom ♪ ♪ Freedom, freedom ♪

Peter Robinson: Welcome to Uncommon Knowledge. I'm Peter Robinson. Mary Bush grew up in segregated Birmingham, then went on to a career in finance and business that saw her earn an MBA from the University of Chicago, work at Citibank in Chase Manhattan, serve in the Treasury Department during the Reagan administration, sit on the boards of companies, including Marriott and Texaco, and found Bush International, the consulting firm, which she now serves as President. Freeman Hrabowski III grew up right across the street from Mary Bush. He went on to a career in academia earning a doctorate in higher education, administration, and statistics from the University of Illinois. Beginning in 1992, Dr. Hrabowski served as President of the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, one of the 12 universities in the University of Maryland system. During his tenure, UMBC became the number one producer in the nation of African Americans who went on to complete STEM PhDs. Dr. Hrabowski stepped down as president of UMBC just last year. Condoleezza Rice grew up here in Birmingham, in the same neighborhood as Mary Bush and Freeman Hrabowski. She went on to earn a doctorate in international relations from the University of Denver. She then went on to a career at Stanford University that saw her rise to Provost and that she interrupted to serve during the administration of George W. Bush as National Security Advisor and Secretary of State. Secretary Rice now serves as Director of the Hoover Institution, the Public Policy Center at Stanford. We're gathered in Birmingham today in the Westminster Presbyterian Church, where the pastor in the 1960s was the Reverend John Wesley Rice Jr., Condie's father. I've only been here a day and a half, but it seems to fall to me to welcome the three of you back to your hometown in Birmingham. The spring of 1963, April 3rd, a local civil rights organization, the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights, led by Birmingham's own Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth is joined by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr's Southern Christian Leadership Conference in conducting sit-ins at downtown lunch counters. April 6th, Reverend Shuttlesworth leads a march on City Hall. More than 30 protesters are arrested. April 11, Dr. King is served with an injunction against boycotting, trespassing, or encouraging such acts. April 12th, Dr. King, Reverend Shuttlesworth, and others lead a march protesting the injunction. They're arrested. April 14th, Easter Sunday, a thousand protestors attempt to march on City Hall, police block their way arresting more than 30. April 19, the New York Post publishes excerpts of a document that Dr. King, using fragments of newspapers, has composed in what would soon become known as the Letter from Birmingham Jail. Dr. King writes, quote, "I cannot sit idly by in Atlanta and not be concerned about what happens in Birmingham. We are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Anyone who lives in the United States can never be considered an outsider." May 2nd, young blacks begin leaving school to march. They walk in groups of 10 to 50 across Kelly Ingram Park, the City Square, intending to protest at City Hall just a few blocks away. They never reach City Hall. The Birmingham Commissioner of Public Safety, Bull Connor, orders his men to assault the students with fire hoses and police dogs. Many of the young people are injured. More than a thousand are arrested. May 10th, a settlement is reached under the terms of the Birmingham Truce, Dr. King, Reverend Shuttlesworth and other civil rights leaders agree to end the protests, Birmingham business leaders promise in turn that within 90 days they will desegregate businesses and public facilities. For the most part, they keep their word and official segregation in Birmingham, unofficial segregation would continue for a long time, but official segregation in Birmingham comes, for the most part, to an end. That's not by any means the means of the story. And we'll continue to what happened afterwards. But for now, let me ask you about those events. What is now referred to often as the Children's Crusade. You're the last generation who experienced the Old South and the Civil Rights Movement that rose against it. Mary Bush, you were only in your teens, but if I understand this correctly, you heard Dr. King speak.

Mary Bush: I did.

Peter Robinson: Tell us about what he was like, what it meant to this town when he came here.

Mary Bush: The time that I heard Dr. King speak was at my church, Sixth Avenue Baptist Church.

- [Martin Luther King] That the federal government not put a cent in this city unless it decides to face the realities of desegregation.

Mary Bush: The church was absolutely packed. My parents and I went, and it was really a momentous event because here was Martin Luther King who had become, well-known for his civil rights activities.

Peter Robinson: He was a famous figure coming to town.

Mary Bush: He was a famous figure coming to town. So it made a huge impression on me. One, to hear him speak and to talk about freedom. When the children's marches were organized, I very much wanted to participate. But I had a father who when he said something, he meant it. He said, no, you cannot go. However, I will tell you one other part of the story. As you probably know, my friend, Freeman Hrabowski, did participate. It's a very interesting story as to how he got to do it, which maybe he'll tell you. But he was arrested, and I came home from somewhere one day, and my father is in our front yard, and there are tears strolling down his face. And I said, Daddy, what's wrong? And he said, Freeman has been arrested. Well, you see, Freeman was like his child too.

Peter Robinson: Freeman lived across the street.

Mary Bush: He lived right across the street from me. So my father was in much distress because he didn't know what was going to happen to Freeman because this was a city that reacted to people trying to get their freedom in very violent ways.

Peter Robinson: So Freeman, Mary's father said, no, you're not marching.

Freeman Hrabowski: Right.

Peter Robinson: Did you get your parent's permission? Did you march in spite? Let me explain the question.

Freeman Hrabowski: Yeah.

Peter Robinson: It's easy, looking back on these events 60 years ago, to think that the black community rose as one. Well, you were united, but there were hard decisions to make every day.

Peter Robinson: There was violence all around this notion of children marching was not easy. Dr. King himself resisted it for a number of days before deciding it had to be done. So how did you and your family address that? You were how old at this stage?

Freeman Hrabowski: I was 12.

Peter Robinson: 12 years old.

Peter Robinson: You were still a child.

Freeman Hrabowski: Yeah. But I was in the ninth grade. I was about to go to the 10th grade. I had skipped a couple of grades. And I should tell you that most people saw Dr. King as a, certainly a hero, but he was also a troublemaker. He was gonna change things. People don't realize that, in that it was uncomfortable. People were worried, particularly people who were maybe buying houses. The word had gone around that, my goodness, banks could pull mortgages. Right. People were saying, we don't know what's gonna happen. It wasn't like everybody was saying, this is the right thing to do. When you look back on it, it seems like this was all a good idea. No, people were very confused about what to do and about sending children out. So it was n't a given that, oh, this is the right thing to do. They were proud of the idea, we are doing something. But no, we went home. I didn't want to go to church anyway. Who wants to go to church in the middle of the week? I was a rebellious kid. And they placated me by letting me take my math. I love math. Reverend Rice knew I love math. So I'm sitting in the back doing my math, and this man at the lectern says, if the children participate, they'll go to better schools. Now, we loved our teachers, but we always had been told the white schools were better. We wanted to see what that was all about. And I wanted to see if they were as smart as people said they were. 'Cause I knew I was smart, because to me, smart meant you could work hard. Right. And you could solve the math problems. So I'm doing my algebra, and this guy says this, and I look up and it, of course, it's Dr. King. And here's the point. I went home and I said, I want to go. And they said, what? Absolutely not.

Peter Robinson: Same reaction Mary got.

Freeman Hrabowski: Absolutely not. And I said to my parents, in typical Freeman form, you guys are hypocrites. You made me go, I listened and now you say no. And what will your parents say? Go to your room because you are not supposed to tell your parents they're hypocrites. Right. And so I was punished. They sent me to my room. The next morning they came in, they had not slept. They prayed all night. I knew I was in trouble. And they said to me, with real distress on their faces, it wasn't that we didn't trust you, we don't trust the people who will be over you, because if you march, you're going to jail. But we're gonna put you in God's hands. Now, my students say, doc, you must have been really brave. I was not a brave child. If a fight broke out at school, Freeman was running the other way. The only thing I'd ever attacked in my life was a math problem. You get that. Right? But I did want a better education. My teachers were wonderful. We did not have the resources. We didn't understand what great education might be. We didn't understand what it might be. But I did go, and it was a horrific experience. They treated us like slaves, like animals. Too many kids, stinky, not enough bathrooms.

Peter Robinson: This is in prison?

Freeman Hrabowski: Yeah, in the jail.

Peter Robinson: So what was it like when you were marching?

Freeman Hrabowski: It was both inspiring and frightening.

Peter Robinson: These are hard questions to ask.

Freeman Hrabowski: Yeah. Yeah.

Peter Robinson: I don't know if you noticed this, but I'm white. That makes it very, very, very uncomfortable. But I keep thinking-

Freeman Hrabowski: And we in Birmingham, Alabama. Alright.

Peter Robinson: And here we are in Birmingham. But what was it like to have an encounter with a white person? What was it like not to be able to go to a certain store or during this event, to have an encounter with the police and you knew they were going to be against you just because you were black? Do you avoid them? Do you shrink from it? How does this work?

Freeman Hrabowski: It's interesting that Dr. King's-

Peter Robinson: It's gone now, but you remember.

Freeman Hrabowski: No, no. All the people. And the two things I would say, we are all from privilege in that we had these wonderful parents, working mothers and fathers and of faith. We were going to church all the time. Sixth Avenue Baptist, Westminster. And her father, Reverend Rice, our beloved Reverend Rice, Reverend Porter, dear friends, and Reverend Rice was our youth fellowship advisor, he was amazing, Presbyterian, who would come to Sixth Avenue. We would have these wonderful conversations about what it meant to be teenagers. Right. And talking about ideas in our Honor Society. He was an advisor to our Honor Society. Right. And he was an intellectual. And we would have these, so in our community, we could talk about ideas. And yet we, you tell me about you all, but I've never talked to anybody white.

Peter Robinson: You never did?

Condoleezza Rice: No. The only time I remember a white person was we went to visit Santa Claus.

Freeman Hrabowski: Oh yeah.

Condoleezza Rice: And I was five.

Condoleezza Rice: You would go down to Pissits or down to Lovemans to visit Santa Claus. And this particular Santa Claus was taking all the little black children and holding them out here. He was taking little white children and putting them on his knee. Now you knew my father. My father said to my mother, Angelina, if he does that to Condoleezza, I'm gonna pull all that stuff off of him and show him to be the cracker that he is. So there we're sitting there, I'm five, daddy, Santa Claus, daddy, Santa Claus. What a way to meet Santa Claus.

Freeman Hrabowski: That's Reverend Rice.

Condoleezza Rice: So I think somehow Santa Claus could see my father, who was six three and a football player. And when it came time, Santa Claus took me and he put me on his knee said, nice little girl. So that was the only, but to your question, is the only white person I'd ever seen.

Freeman Hrabowski: Context, yeah.

Condoleezza Rice: Yeah.

Freeman Hrabowski: Yeah, yeah.

Peter Robinson: Before we depart, we'll return to it in a moment. But before we depart from those events in 1963, your father, as we've heard, was a beloved figure.

Condoleezza Rice: Yes.

Peter Robinson: He was reverend in this church, the black community was, as I've looked, it's about a hundred thousand people. It strikes me that the pastors, the ministers must have known each other.

Condoleezza Rice: They did, yeah.

Peter Robinson: So your father knew Reverend Shuttlesworth.

Condoleezza Rice: They were good friends.

Peter Robinson: Good friends.

Condoleezza Rice: Yes. Yes.

Peter Robinson: And of course, you were a very little girl. But do you remember at the time these tensions, it's fascinating to me to think, once you think it, it seems obvious, but the assumption that there's this uprising of righteousness and peaceful, nonviolent protest. But, of course, it was more complicated than that. Dr. King was an outsider. This notion of putting children in harm's way. Do you remember your father talking about that at home?

Condoleezza Rice: I do remember my father talking about it. I was little. I'm a little younger than these two. And I remember a couple of things about it. I remember my father saying to my mother who was sitting, standing in our little hallway: Angelina, I'm not gonna go down there and pretend to be nonviolent, because if a policeman takes a billy club to me, I'm gonna try to kill him. And my daughter will be an orphan. Because my father actually didn't believe in the nonviolent part. Do you know who one of my father's great friends was? Stokely Carmichael.

Peter Robinson: Really?

Condoleezza Rice: Yes. He somehow found that more confrontational side, something that he admired. And so when the children's march came along, it was a lot like Mary and Freeman's parents. My father said, why would you send children into Bull Connor's henchman? Why would you do that? I wouldn't let my daughter go. And he was very much against the children's march. But when all his students were all carted off to jail, he came down and he walked around. He had good relationship with the police. They let him walk around and he would call parents and say, I saw your daughter. She's fine. I saw your son.

Peter Robinson: And repeat, more than a thousand kids.

Condoleezza Rice: Yeah, yeah.

Peter Robinson: Were jailed.

Condoleezza Rice: Yeah. Not too far from here. The jail was not too far from here.

Freeman Hrabowski: And he was wonderful. When I came back, just two, three parts of the story to show you.

Peter Robinson: Please, please.

Freeman Hrabowski: First of all, the reason they allowed me to go was that I challenged my mother. My mother had led a protest in 1948.

Freeman Hrabowski: For the equalization of teacher salaries and was fired for that. And she was always proud of that in another county. And one of her best friends was the mother of Angela Davis.

Freeman Hrabowski: Yeah. And my mother and Angela Davis' mother taught together over the years. And my mother taught Angela Davis and her sister, and my mother, and Angela Davis's mother taught me. And they had this great sisterhood about fighting for justice. Alright. And I reminded, I said, mother, you fought for justice. She said, but I was an adult. And I said, but you taught me to think. And they did allow me to go. It was amazing. About her father, when we did get back to school, he and George Bell gave me special attention to see how I was psychologically. And he said to me, remember, you are an A student. You are an A student. He wanted me to remember that. He wanted me to remember how to define myself. It was very important. Just as Mr. Bell, who was the uncle of Alma Vivian Powell, General Powell's wife.

Mary Bush: There's something else.

Condoleezza Rice: That's right, yeah.

Mary Bush: Something else you need to know about Dr. Bell. He was the principal of the Allemen High School, we mentioned earlier that Freeman and I both went to, Dr. Bell was an amazing man. He was very much about excellence. He would come to our classes, he would give the students extra problems to solve, but he was also a disciplinarian. So even the really big guys who might have a tendency to act out were coward by Dr. Bell because he has this-

Condoleezza Rice: He was a tiny guy.

Mary Bush: Booming voice. And he was a tiny man. But we loved him because he was all about hard work and excellence, and always striving to be the best you could be. So when my class was going into its senior year, Dr. Bell was about to retire, and we literally begged him not to retire. This shows you one, how close the principals, the ministers that we've talked about, the teachers were to the students. So it was our parents, who really pushed us about hard work, excellence, and the value of education. But it was also our teachers and our principals.

Condoleezza Rice: You have to be twice as good. Right?

Mary Bush: Twice as good. Twice as good.

Peter Robinson: So, I find this so striking that here you are in the Jim Crow South and you've got parents who are wonderful parents.

Mary Bush: Yes.

Peter Robinson: And schools that are good schools.

Condoleezza Rice: And good teachers.

Peter Robinson: And good teachers, dedicated. I mean, honestly, truly, I hear you describe the circumstances in which you grew up. And I wouldn't hesitate, would not, now my children are older now, but I'd have dropped my children.

Peter Robinson: In black Birmingham like that because of the education, the self-confidence.

Condoleezza Rice: But let me-

Peter Robinson: So what am I missing here?

Condoleezza Rice: Let me step back a little bit because I wanna say two things. First of all, about the principles. To be a principal in a school in Birmingham Was like being a God.

Mary Bush: Exactly.

Condoleezza Rice: We admire-

Peter Robinson: The revered position.

Condoleezza Rice: Revered position So Alma Powell's father, Mr. R.C. Johnson was the principal of Parker High, which was the largest black school. And her uncle was the principal of Alleman High, which was the second largest. When Mr. W.W. Whetstone, who was the principal of our elementary school, died. His funeral was like that for the Head of State, because teachers were revered, principals were revered. But there was a dark underbelly to that, which is that if you were an educated black person, you really only had a couple of good options. And teaching was the best option. And so it was a sense of a lack of opportunity for black professionals that led to the best and brightest going into teaching. In another time-

Peter Robinson: So that funeral, everybody understood this is a man who holds a position of importance to us, but he's also the best we have produced.

Condoleezza Rice: The best we have produced

Peter Robinson: The best of our community. I see.

Condoleezza Rice: And if you were a teacher, you were really highly regarded and in another generation or two, people would have other options. And some would take them.

Freeman Hrabowski: With few exceptions, who became physicians and lawyers.

Condoleezza Rice: The few, you had a couple of lawyers, a few businessmen.

Mary Bush: I call this the best minds. We got the best minds because just as Condie said the generation before us, our parents and teachers, they didn't have the other opportunities. The doors were not open. So they became teachers and we were the wonderful blessed recipients of that.

Peter Robinson: I see.

Freeman Hrabowski: But I want to go back because you talk about your children coming here, it depends on what background your children would've had. Because again, I wanna say this, we were so privileged, they gave us the piano lessons, and we had books in the house.

Condoleezza Rice: French lessons.

Freeman Hrabowski: And French lessons, all of that.

Mary Bush: The symphony.

Mary Bush: Which we couldn't go to, they did it at home.

Freeman Hrabowski: Yeah. We couldn't go into the museum, but my mother would get the pamphlets, and we would read stuff on the outside. And so my parents sent me to Massachusetts to get extra education and to see what it would be like to be in classes with white kids in the summers and I saw the difference between the Southern education and the education of New England. And I saw the superiority in Massachusetts, you see, in chemistry, in literature. And here's the point, clearly the money that they were putting into education in New England would make that education there far superior to any education in public schools for black or white in Alabama. And you see it in the standardized test scores for children in general. As I look at, as I study test scores, whatever level. Alright, number one. Number two, when you look beyond the well-educated families as we were from the working families. All right? When you look at poor children, white and black, here or in America, but in Alabama. And you see what happens to those children. Back then and today, the future is not bright. That's the challenge.

Condoleezza Rice: But Freeman, I wanna challenge you on one thing and agree with you on another, I'm not sure it was superior, right?

Peter Robinson: The New England education?

Condoleezza Rice: The New England education, because I'm not sure I could have turned out better if I'd gone to school in New England or that you could, or that Mary could. And I look at Amelia Rutledge and I look at Cheryl McCarthy.

Freeman Hrabowski: For the best, for the very best.

Condoleezza Rice: But we weren't actually elite. We were kind of professional class, middle-class. There was a more elite black community that lived over past Smithfield. All right.

Freeman Hrabowski: But I'm particularly looking at math and science.

Freeman Hrabowski: I'm looking at math and science. All right. I'm looking at chemistry, I'm looking at those areas and I'm looking at, for example, what was covered in chemistry in Massachusetts and what was covered here. And then I looked at what happened when I took some courses at the university here at the white university compared to there, it was superior, as a mathematician, I'm saying.

Condoleezza Rice: All that I'm saying is the resources may have been superior.

Freeman Hrabowski: Yeah. The resources.

Condoleezza Rice: I'm not sure that the instruction was. And I am gonna tell you why, because I then went to Denver and I went to one of the best high schools in Denver, St. Mary's Academy. When we arrived in Denver, I went to St. Mary's Academy 'cause my parents who were educators said the Denver Public schools are not as good as the schools that you went to in Birmingham.

Freeman Hrabowski: Well, let's say this.

Condoleezza Rice: So they made that choice.

Freeman Hrabowski: I love the fact that we can disagree like that.

Freeman Hrabowski: Because we also disagree on philosophies of other things. And that lemme just say that, listen, let's go there too. Let's go there too. And I always say middle-class Birmingham may love each other in many ways, but politically and stuff, we have some differences here. We have agreed to disagree.

Condoleezza Rice: But I wanna-

Freeman Hrabowski: But lemme tell you my part as mathematician, standardized test scores. All you need to do is look at standardized test scores in Massachusetts compared to Alabama.

Freeman Hrabowski: And my point is made QED.

Freeman Hrabowski: Mathematically, right.

Condoleezza Rice: No, well, I don't know about standardized test scores. I know where you ended up. But let me go back to a point, the place where I agree, but I wanna extend the story.

Freeman Hrabowski: Go ahead.

Condoleezza Rice: All right. So it is absolutely true that if you were poor.

Freeman Hrabowski: Yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah, yeah.