- USF Research

- USF Libraries

Digital Commons @ USF > College of Arts and Sciences > Women's and Gender Studies > Theses and Dissertations

Women's and Gender Studies Theses and Dissertations

Theses/dissertations from 2023 2023.

Social Media and Women Empowerment in Nigeria: A Study of the #BreakTheBias Campaign on Facebook , Deborah Osaro Omontese

Theses/Dissertations from 2022 2022

Going Flat: Challenging Gender, Stigma, and Cure through Lesbian Breast Cancer Experience , Beth Gaines

Incorrect Athlete, Incorrect Woman: IOC Gender Regulations and the Boundaries of Womanhood in Professional Sports , Sabeehah Ravat

Transnational Perspectives on the #MeToo and Anti-Base Movements in Japan , Alisha Romano

Theses/Dissertations from 2021 2021

Criminalizing LGBTQ+ Jamaicans: Social, Legal, and Colonial Influences on Homophobic Policy , Zoe C. Knowles

Dismantling Hegemony through Inclusive Sexual Health Education , Lauren Wright

Theses/Dissertations from 2020 2020

Transfat Representation , Jessica "Fyn" Asay

Theses/Dissertations from 2019 2019

Ain't I a Woman, Too? Depictions of Toxic Femininity, Transmisogynoir, and Violence on STAR , Sunahtah D. Jones

“The Most Muscular Woman I Have Ever Seen”: Bev FrancisPerformance of Gender in Pumping Iron II: The Women , Cera R. Shain

"Roll" Models: Fat Sexuality and Its Representations in Pornographic Imagery , Leah Marie Turner

Theses/Dissertations from 2018 2018

Reproducing Intersex Trouble: An Analysis of the M.C. Case in the Media , Jamie M. Lane

Race and Gender in (Re)integration of Victim-Survivors of CSEC in a Community Advocacy Context , Joshlyn Lawhorn

Penalizing Pregnancy: A Feminist Legal Studies Analysis of Purvi Patel's Criminalization , Abby Schneller

A Queer and Crip Grotesque: Katherine Dunn's , Megan Wiedeman

Theses/Dissertations from 2017 2017

"Mothers like Us Think Differently": Mothers' Negotiations of Virginity in Contemporary Turkey , Asli Aygunes

Surveilling Hate/Obscuring Racism?: Hate Group Surveillance and the Southern Poverty Law Center's "Hate Map" , Mary McKelvie

“Ya I have a disability, but that’s only one part of me”: Formative Experiences of Young Women with Physical Disabilities , Victoria Peer

Resistance from Within: Domestic violence and rape crisis centers that serve Black/African American populations , Jessica Marie Pinto

(Dis)Enchanted: (Re)constructing Love and Creating Community in the , Shannon A. Suddeth

Theses/Dissertations from 2016 2016

"The Afro that Ate Kentucky": Appalachian Racial Formation, Lived Experience, and Intersectional Feminist Interventions , Sandra Louise Carpenter

“Even Five Years Ago this Would Have Been Impossible:” Health Care Providers’ Perspectives on Trans* Health Care , Richard S. Henry

Tough Guy, Sensitive Vas: Analyzing Masculinity, Male Contraceptives & the Sexual Division of Labor , Kaeleen Kosmo

Theses/Dissertations from 2015 2015

Let’s Move! Biocitizens and the Fat Kids on the Block , Mary Catherine Dickman

Interpretations of Educational Experiences of Women in Chitral, Pakistan , Rakshinda Shah

Theses/Dissertations from 2014 2014

Incredi-bull-ly Inclusive?: Assessing the Climate on a College Campus , Aubrey Lynne Hall

Her-Storicizing Baldness: Situating Women's Experiences with Baldness from Skin and Hair Disorders , Kasie Holmes

In the (Radical) Pursuit of Self-Care: Feminist Participatory Action Research with Victim Advocates , Robyn L. Homer

Theses/Dissertations from 2013 2013

Significance is Bliss: A Global Feminist Analysis of the Liberian Truth and Reconciliation Commission and its Privileging of Americo-Liberian over Indigenous Liberian Women's Voices , Morgan Lea Eubank

Monsters Under the Bed: An Analysis of Torture Scenes in Three Pixar Films , Heidi Tilney Kramer

Theses/Dissertations from 2012 2012

Can You Believe She Did THAT?!:Breaking the Codes of "Good" Mothering in 1970s Horror Films , Jessica Michelle Collard

Don't Blame It on My Ovaries: Exploring the Lived Experience of Women with Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome and the Creation of Discourse , Jennifer Lynn Ellerman

Valanced Voices: Student Experiences with Learning Disabilities & Differences , Zoe DuPree Fine

An Interactive Guide to Self-Discovery for Women , Elaine J. Taylor

Selling the Third Wave: The Commodification and Consumption of the Flat Track Roller Girl , Mary Catherine Whitlock

Theses/Dissertations from 2010 2010

Beyond Survival: An Exploration of Narrative Healing and Forgiveness in Healing from Rape , Heather Curry

Theses/Dissertations from 2009 2009

Gender Trouble In Northern Ireland: An Examination Of Gender And Bodies Within The 1970s And 1980s Provisional Irish Republican Army In Northern Ireland , Jennifer Earles

"You're going to Hollywood"!: Gender and race surveillance and accountability in American Idol contestant's performances , Amanda LeBlanc

From the academy to the streets: Documenting the healing power of black feminist creative expression , Tunisia L. Riley

Developing Feminist Activist Pedagogy: A Case Study Approach in the Women's Studies Department at the University of South Florida , Stacy Tessier

Women in Wargasm: The Politics of Womenís Liberation in the Weather Underground Organization , Cyrana B. Wyker

Theses/Dissertations from 2008 2008

Opportunities for Spiritual Awakening and Growth in Mothering , Melissa J. Albee

A Constant Struggle: Renegotiating Identity in the Aftermath of Rape , Jo Aine Clarke

I am Warrior Woman, Hear Me Roar: The Challenge and Reproduction of Heteronormativity in Speculative Television Programs , Leisa Anne Clark

Theses/Dissertations from 2007 2007

Reforming Dance Pedagogy: A Feminist Perspective on the Art of Performance and Dance Education , Jennifer Clement

Narratives of lesbian transformation: Coming out stories of women who transition from heterosexual marriage to lesbian identity , Clare F. Walsh

The Conundrum of Women’s Studies as Institutional: New Niches, Undergraduate Concerns, and the Move Towards Contemporary Feminist Theory and Action , Rebecca K. Willman

Theses/Dissertations from 2006 2006

A Feminist Perspective on the Precautionary Principle and the Problem of Endocrine Disruptors under Neoliberal Globalization Policies , Erica Hesch Anstey

Asymptotes and metaphors: Teaching feminist theory , Michael Eugene Gipson

Postcolonial Herstory: The Novels of Assia Djebar (Algeria) and Oksana Zabuzhko (Ukraine): A Comparative Analysis , Oksana Lutsyshyna

Theses/Dissertations from 2005 2005

Loving Loving? Problematizing Pedagogies of Care and Chéla Sandoval’s Love as a Hermeneutic , Allison Brimmer

Exploring Women’s Complex Relationship with Political Violence: A Study of the Weathermen, Radical Feminism and the New Left , Lindsey Blake Churchill

The Voices of Sex Workers (prostitutes?) and the Dilemma of Feminist Discourse , Justine L. Kessler

Reconstructing Women's Identities: The Phenomenon Of Cosmetic Surgery In The United States , Cara L. Okopny

Fantastic Visions: On the Necessity of Feminist Utopian Narrative , Tracie Anne Welser

Theses/Dissertations from 2004 2004

The Politics of Being an Egg “Donor” and Shifting Notions of Reproductive Freedom , Elizabeth A. Dedrick

Women, Domestic Abuse, And Dreams: Analyzing Dreams To Uncover Hidden Traumas And Unacknowledged Strengths , Mindy Stokes

Theses/Dissertations from 2001 2001

Safe at Home: Agoraphobia and the Discourse on Women’s Place , Suzie Siegel

Theses/Dissertations from 2000 2000

Women, Environment and Development: Sub-Saharan Africa and Latin America , Evaline Tiondi

Advanced Search

- Email Notifications and RSS

- All Collections

- USF Faculty Publications

- Open Access Journals

- Conferences and Events

- Theses and Dissertations

- Textbooks Collection

Useful Links

- Women's and Gender Studies Department Homepage

- Rights Information

- SelectedWorks

- Submit Research

Home | About | Help | My Account | Accessibility Statement | Language and Diversity Statements

Privacy Copyright

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

43 What Are Feminist Criticism, Postfeminist Criticism, and Queer Theory?

Learning Objectives

- Use a variety of approaches to texts to support interpretations (CLO 1.2)

- Using a literary theory, choose appropriate elements of literature (formal, content, or context) to focus on in support of an interpretation (CLO 2.3)

- Be exposed to a variety of critical strategies through literary theory lenses, such as formalism/New Criticism, reader-response, structuralism, deconstruction, historical and cultural approaches (New Historicism, postcolonial, Marxism), psychological approaches, feminism, and queer theory (CLO 4.1)

- Understand how context impacts the reading of a text, and how different contexts can bring about different readings (CLO 4.3)

- Demonstrate awareness of critical approaches by pairing them with texts in productive and illuminating ways (CLO 5.5)

- Demonstrate through discussion and/or writing how textual interpretation can change given the context from which one reads (CLO 6.2)

- Understand that interpretation is inherently political, and that it reveals assumptions and expectations about value, truth, and the human experience (CLO 7.1)

Feminist Criticism

Feminist criticism is a critical approach to literature that seeks to understand how gender and sexuality shape the meaning and representation of literary texts. While feminist criticism has its roots in the 1800s (First Wave), it became a critical force in the early 1970s (Second Wave) as part of the broader feminist movement and continues to be an important and influential approach to literary analysis.

Feminist critics explore the ways in which literature reflects and reinforces gender roles and expectations, as well as the ways in which it can challenge and subvert them. They examine the representation of female characters and the ways in which they are portrayed in relation to male characters, as well as the representation of gender and sexuality more broadly. With feminist criticism, we may consider both the woman as writer and the written woman.

As with New Historicism and Cultural Studies criticism, one of the key principles of feminist criticism is the idea that literature is not a neutral or objective reflection of reality, but rather, literary texts are shaped by the social and cultural context in which they are produced. Feminist critics are interested in gender stereotypes, exploring how literature reflects and reinforces patriarchal power structures and how it can be used to challenge and transform these structures.

Postfeminist Criticism

Postfeminist criticism is a critical approach to literature that emerged in the 1990s and 2000s as a response to earlier feminist literary criticism. It acknowledges the gains of feminism in terms of women’s rights and gender equality, but also recognizes that these gains have been uneven and that new forms of gender inequality have emerged.

The “post” in postfeminist can be understood like the “post” in post-structuralism or postcolonialism. Postfeminist critics are interested in exploring the ways in which gender and sexuality are constructed and represented in literature, but they also pay attention to the ways in which other factors such as race, class, and age intersect with gender to shape experiences and identities. They seek to move beyond the binary categories of male/female and masculine/feminine, and to explore the ways in which gender identity and expression are fluid and varied.

Postfeminist criticism also pays attention to the ways in which contemporary culture, including literature and popular media, reflects and shapes attitudes towards gender and sexuality. It explores the ways in which these representations can be empowering or constraining and seeks to identify and challenge problematic representations of gender and sexuality.

One of the key principles of postfeminist criticism is the importance of diversity and inclusivity. Postfeminist critics are interested in exploring the experiences of individuals who have been marginalized or excluded by traditional feminist discourse, including women of color, queer and trans individuals, and working-class women. If you are familiar with t he American Dirt controversy, where Oprah’s book pick was widely criticized because the author was a white woman, is an example of this type of approach.

Queer Theory

Queer theory is a critical approach to literature and culture that seeks to challenge and destabilize dominant assumptions about gender and sexuality. It emerged in the 1990s as a response to the limitations of traditional gay and lesbian studies, which tended to focus on issues of identity and representation within a binary understanding of gender and sexuality. According to Jennifer Miller,

“The film theorist Teresa de Lauretis (figure 1.1) coined the term at a University of California, Santa Cruz, conference about lesbian and gay sexualities in February 1990…. In her introduction to the special issue, de Lauretis outlines the central features of queer theory, sketching the field in broad strokes that have held up remarkably well.”

While queer theory was formalized as a critical approach in 1990, scholars built on earlier ideas from Michel Foucault’s History of Sexuality, as well as the works of Judith Butler, Eve Sedgewick, and others.

Queer theory is interested in exploring the ways in which gender and sexuality are constructed and performative, rather than innate or essential. As with feminist and postfeminist criticism, queer theory seeks to expose the ways in which these constructions are shaped by social, cultural, and historical factors, but additionally, queer theory seeks to challenge the rigid binaries of heterosexuality and homosexuality. Queer theory also emphasizes the importance of intersectionality, or the ways in which gender and sexuality intersect with other forms of identity such as race, class, and ability. It seeks to uncover the complex and nuanced ways in which multiple forms of oppression and privilege intersect.

Queer theory focuses on the importance of resistance and subversion. Scholars are interested in exploring the ways in which marginalized individuals and communities have resisted and subverted the dominant culture’s norms and values, observing how these acts of resistance and subversion can be empowering and transformative.

Scholarship: Examples from Feminist, Postfeminist, and Queer Theory Critics

Feminist criticism could technically be considered to be as old as writing. Since Sappho of Lesbos wrote her famous lyrics, women authors have been an active and important part of their cultures’ literary traditions. Why, then, are we sometimes not as familiar with the works of women authors? One of the earliest feminist critics is the French existentialist philosopher and writer Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986). In her important book, The Second Sex, she lays the groundwork for feminist literary criticism by considering how in most societies, “man” is normal, and “woman” is “the Other.” You may have heard this famous quote: “One is not born a woman but becomes one.” (French: “On ne naît pas femme, on le devient”). This phrase encapsulates the essential feminist idea that “woman” is a social construct.

Feminist: Excerpt from Introduction to The Second Sex (1949), translated by H.M. Parshley

If her functioning as a female is not enough to define woman, if we decline also to explain her through ‘the eternal feminine’, and if nevertheless we admit, provisionally, that women do exist, then we must face the question “what is a woman”? To state the question is, to me, to suggest, at once, a preliminary answer. The fact that I ask it is in itself significant. A man would never set out to write a book on the peculiar situation of the human male. But if I wish to define myself, I must first of all say: ‘I am a woman’; on this truth must be based all further discussion. A man never begins by presenting himself as an individual of a certain sex; it goes without saying that he is a man. The terms masculine and feminine are used symmetrically only as a matter of form, as on legal papers. In actuality the relation of the two sexes is not quite like that of two electrical poles, for man represents both the positive and the neutral, as is indicated by the common use of man to designate human beings in general; whereas woman represents only the negative, defined by limiting criteria, without reciprocity. In the midst of an abstract discussion it is vexing to hear a man say: ‘You think thus and so because you are a woman’; but I know that my only defence is to reply: ‘I think thus and so because it is true,’ thereby removing my subjective self from the argument. It would be out of the question to reply: ‘And you think the contrary because you are a man’, for it is understood that the fact of being a man is no peculiarity. A man is in the right in being a man; it is the woman who is in the wrong. It amounts to this: just as for the ancients there was an absolute vertical with reference to which the oblique was defined, so there is an absolute human type, the masculine. Woman has ovaries, a uterus: these peculiarities imprison her in her subjectivity, circumscribe her within the limits of her own nature. It is often said that she thinks with her glands. Man superbly ignores the fact that his anatomy also includes glands, such as the testicles, and that they secrete 3 hormones. He thinks of his body as a direct and normal connection with the world, which he believes he apprehends objectively, whereas he regards the body of woman as a hindrance, a prison, weighed down by everything peculiar to it. ‘The female is a female by virtue of a certain lack of qualities,’ said Aristotle; ‘we should regard the female nature as afflicted with a natural defectiveness.’ And St Thomas for his part pronounced woman to be an ‘imperfect man’, an ‘incidental’ being. This is symbolised in Genesis where Eve is depicted as made from what Bossuet called ‘a supernumerary bone’ of Adam. Thus humanity is male and man defines woman not in herself but as relative to him; she is not regarded as an autonomous being. Michelet writes: ‘Woman, the relative being …’ And Benda is most positive in his Rapport d’Uriel: ‘The body of man makes sense in itself quite apart from that of woman, whereas the latter seems wanting in significance by itself … Man can think of himself without woman. She cannot think of herself without man.’ And she is simply what man decrees; thus she is called ‘the sex’, by which is meant that she appears essentially to the male as a sexual being. For him she is sex – absolute sex, no less. She is defined and differentiated with reference to man and not he with reference to her; she is the incidental, the inessential as opposed to the essential. He is the Subject, he is the Absolute – she is the Other.’ The category of the Other is as primordial as consciousness itself. In the most primitive societies, in the most ancient mythologies, one finds the expression of a duality – that of the Self and the Other. This duality was not originally attached to the division of the sexes; it was not dependent upon any empirical facts. It is revealed in such works as that of Granet on Chinese thought and those of Dumézil on the East Indies and Rome. The feminine element was at first no more involved in such pairs as Varuna-Mitra, Uranus-Zeus, Sun-Moon, and Day-Night than it was in the contrasts between Good and Evil, lucky and unlucky auspices, right and left, God and Lucifer. Otherness is a fundamental category of human thought. Thus it is that no group ever sets itself up as the One without at once setting up the Other over against itself. If three travellers chance to occupy the same compartment, that is enough to make vaguely hostile ‘others’ out of all the rest of the passengers on the train. In small-town eyes all persons not belonging to the village are ‘strangers’ and suspect; to the native of a country all who inhabit other countries are ‘foreigners’; Jews are ‘different’ for the anti-Semite, Negroes are ‘inferior’ for American racists, aborigines are ‘natives’ for colonists, proletarians are the ‘lower class’ for the privileged. Excerpt from The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir (translated by H.M. Parshley) is licensed All Rights Reserved and is used here under Fair Use exception.

How do you feel about de Beauvoir’s conception of woman as “Other”? How are her approaches to gender similar to what we have learned about deconstruction and New Historicism? Could feminist criticism, like Marxist, postcolonial, and ethnic studies criticism, also be thought of as having “power” as its central concern?

Let’s move on to postfeminist criticism. When you think of Emily Dickinson, sadomasochism is probably the last thing that comes to mind, unless you’re postfeminist scholar and critic Camille Paglia . No stranger to culture wars, Paglia has often courted controversy; a 2012 New York Times article noted that “ [a]nyone who has been following the body count of the culture wars over the past decades knows Paglia.” Paglia continues to write and publish both scholarship and popular works. Her fourth essay collection, Provocations: Collected Essays on Art, Feminism, Politics, Sex, and Education , was published by Pantheon in 2018.

This excerpt from her 1990 book Sexual Personae , which drew on her doctoral dissertation research, demonstrates Paglia’s creative and confrontational approach to scholarship.

Postfeminist: Excerpt from “Amherst’s Madame de Sade” in Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson by Camille Paglia (1990)

Consciousness in Dickinson takes the form of a body tormented in every limb. Her sadomasochistic metaphors are Blake’s Universal Man hammering on himself, like the auctioneering Jesus. Her suffering personae make up the gorged superself of Romanticism. I argued that modern sadomasochism is a limitation of the will and that for a Romantic like the mastectomy-obsessed Kleist it represents a reduction of self. A conventional feminist critique of Emily Dickinson’s life would see her hemmed in on all sides by respectability and paternalism, impediments to her genius. But a study of Romanticism shows that post-Enlightenment poets are struggling with the absence of limits, with the gross inflation of solipsistic imagination. Hence Dickinson’s most uncontrolled encounter is with the serpent of her antisocial self, who breaks out like the Aeolian winds let out of their bag. Dickinson does wage guerrilla warfare with society. Her fractures, cripplings, impalements, and amputations are Dionysian disorderings of the stable structures of the Apollonian lawgivers. God, or the idea of God, is the “One,” without whom the “Many” of nature fly apart. Hence God’s death condemns the world to Decadent disintegration. Dickinson’s Late Romantic love of the apocalyptic parallels Decadent European taste for salon paintings of the fall of Babylon or Rome. Her Dionysian cataclysms demolish Victorian proprieties. Like Blake, she couples the miniature and grandiose, great disjunctions of scale whose yawing swings release tremendous poetic energy. The least palatable principle of the Dionysian, I have stressed, is not sex but violence, which Rousseau, Wordsworth, and Emerson exclude from their view of nature. Dickinson, like Sade, draws the reader into ascending degrees of complicity, from eroticism to rape, mutilation, and murder. With Emily Brontë, she uncovers the aggression repressed by humanism. Hence Dickinson is the creator of Sadean poems but also the creator of sadists, the readers whom she smears with her lamb’s blood. Like the Passover angel, she stains the lintels of the bourgeois home with her bloody vision. “There’s been a Death, in the Opposite House,” she announces with a satisfaction completely overlooked by the Wordsworthian reader (389). But merely because poet and modern society are in conflict does not mean art necessarily gains by “freedom.” It is a sentimental error to think Emily Dickinson the victim of male obstructionism. Without her struggle with God and father, there would have been no poetry. There are two reasons for this. First, Romanticism’s overexpanded self requires artificial restraints. Dickinson finds these limitations in sadomasochistic nature and reproduces them in her dual style. Without such a discipline, the Romantic poet cannot take a single step, for the sterile vastness of modern freedom is like gravity-free outer space, in which one cannot walk or run. Second, women do not rise to supreme achievement unless they are under powerful internal compulsion. Dickinson was a woman of abnormal will. Her poetry profits from the enormous disparity between that will and the feminine social persona to which she fell heir at birth. But her sadism is not anger, the a posteriori response to social injustice. It is hostility, an a priori Achillean intolerance for the existence of others, the female version of Romantic solipsism. Excerpt from Sexual Personae by Camille Paglia is licensed All Rights Reserved and is used here under Fair Use exception.

It’s important to note that these critical approaches can be applied to works from any time period, as the title of Paglia’s book makes clear. In this sense, post-feminist scholarship is similar to deconstruction and borrows many of its methods. After reading this passage, do you feel the same way about Emily Dickinson’s poetry? How does Paglia’s postfeminist approach differ from Simone de Beauvoir’s approach to feminism?

Our final reading is from Judith Butler , who is considered both a feminist scholar and a foundational queer theorist. Their 1990 book Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity is considered an essential queer theory text. Expanding on the ideas about gender and performativity, Bodies that Matter (2011) deconstructs the binary sex/gender distinctions that we see in the works of earlier feminist scholars such as Simone de Beauvoir.

Queer Theory: Excerpt from “Introduction,” Bodies that Matter by Judith Butler (2011)

Why should our bodies end at the skin, or include at best other beings encapsulated by skin? -Donna Haraway, A Manifesto for Cyborgs If one really thinks about the body as such, there is no possible outline of the body as such. There are thinkings of the systematicity of the body, there are value codings of the body. The body, as such, cannot be thought, and I certainly cannot approach it. -Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, “In a Word,” interview with Ellen Rooney There is no nature, only the effects of nature: denaturalization or naturalization. -Jacques Derrida, Donner le Temps Is there a way to link the question of the materiality of the body to the performativity of gender? And how does the category of “sex” figure within such a relationship? Consider first that sexual difference is often invoked as an issue of material differences. Sexual difference, however, is never simply a function of material differences that are not in some way both marked and formed by discursive practices. Further, to claim that sexual differences are indissociable from discursive demarcations is not the same as claiming that discourse causes sexual difference. The category “sex” is, from the start, normative; it is what Foucault has called a “regulatory ideal.” In this sense, then, “sex” not only functions as a norm but also is part of a regulatory practice that produces the bodies it governs, that is, whose regulatory force is made clear as a kind of productive power, the power to produce-demarcate, circulate, differentiate-the bodies it controls. Thus, “sex” is a regulatory ideal whose materialization is compelled, and this materialization takes place (or fails to take place) through certain highly regulated practices. In other words, “sex” is an ideal construct that is forcibly materialized through time. It is not a simple fact or static condition of a body, but a process whereby regulatory norms materialize “sex” and achieve this materialization through a forcible reiteration of those norms. That this reiteration is necessary is a sign that materialization is never quite complete, that bodies never quite comply with the norms by which their materialization is impelled. Indeed, it is the instabilities, the possibilities for rematerialization, opened up by this process that mark one domain in which the force of the regulatory law can be turned against itself to spawn rearticulations that call into question the hegemonic force of that very regulatory law. But how, then, does the notion of gender performativity relate to this conception of materialization? In the first instance, performativity must be understood not as a singular or deliberate “act” but, rather, as the reiterative and citational practice by which discourse produces the effects that it names. What will, I hope, become clear in what follows is that the regulatory norms of “sex” work in a performative fashion to constitute the materiality of bodies and, more specifically, to materialize the body’s sex, to materialize sexual difference in the service of the consolidation of the heterosexual imperative. In this sense, what constitutes the fixity of the body, its contours, its movements, will be fully material, but materiality will be rethought as the effect of power, as power’s most productive effect. And there will be no way to understand “gender” as a cultural construct which is imposed upon the surface of matter, understood either as “the body” or its given sex. Rather, once “sex” itself is understood in its normativity, the materiality of the body will not be thinkable apart from the materializatiqn of that regulatory norm. “Sex” is, thus, not simply what one has, or a static description of what one is: it will be one of the norms by which the “one” becomes viable at all, that which qualifies a body for life within the domain of cultural intelligibility. At stake in such a reformulation of the materiality of bodies will be the following: (1) the recasting of the matter of bodies as the effect of a dynamic of power, such that the matter of bodies will be indissociable from the regulatory norms that govern their materialization and the signification of those material effects; (2) the understanding of performativity not as the act by which a subject brings into being what she/he names, but, rather, as that reiterative power of dis.course to produce the phenomena that it regulates and constrains; (3) the construal of “sex” no longer as a bodily given on which the construct of gender is artificially imposed, but as a cultural norm which governs the materialization of bodies; (4) a rethinking of the process by which a bodily norm is assumed, appropriated, taken on as not, strictly speaking, undergone by a subject, but rather that the subject, the speaking “I,” is formed by virtue of having gone through such a process of assuming a sex; and (5) a linking of this process of “assuming” a sex with the question of identification, and with the discursive means by which the heterosexual imperative enables certain sexed identifications and forecloses and/ or disavows other identifications. This exclusionary matrix by which subjects are formed thus requires the simultaneous production of a domain of abject beings, those who are not yet “subjects” but who form the constitutive outside to the domain of the subject. The abject designates here precisely those “unlivable” and “uninhabitable” zones of so cial life, which are nevertheless densely populated by those who do not enjoy the status of the subject, but whose living under the sign of the “unlivable” is required to circumscribe the domain of the subject. This zone of uninhabitability will constitute the defining limit of the subject’s domain; it will constitute that site of dreadful identification against which-and by virtue of which-the domain of the subject will circumscribe its own claim to autonomy and to life. In this sense, then, the subject is constituted through the force of exclusion and abjection, one which produces a constitutive outside to the subject, an abjected outside, which is, after all, “inside” the subject as its own founding repudiation. The forming of a subject requires an identification with the normative phantasm of”sex,” and this identification takes place through a repudiation that produces a domain of abjection, a repudiation without which the subject cannot emerge. This is a repudiation that creates the valence of “abjection” and its status for the subject as a threatening spectre. Further, the materialization of a given sex will centrally concern the regulation of identificatory practices such that the identification with the abjection of sex will be persistently disavowed. And yet, this disavowed abjection will threaten to expose the self-grounding presumptions of the sexed subject, grounded as that subject is in repudiation whose consequences it cannot fully control. The task will be to consider this threat and disruption not as a permanent contestation of social norms condemned to the pathos of perpetual failure, but rather as a critical resource in the struggle to rearticulate the very terms of symbolic legitimacy and intelligibility. Lastly, the mobilization of the categories of sex within political discourse will be haunted in some ways by the very instabilities that the categories effectively produce and foreclose. Although the political discourses that mobilize identity categories tend to cultivate identifications in the service of a political goal, it may be that the persistence of disidentification is equally crucial to the rearticulation of democratic contestation. Indeed, it may be precisely through practices which underscore disidentification with those regulatory norms by which sexual difference is materialized that both feminists and queer politics are mobilized. Such collective disidentifications can facilitate a reconceptualization of which bodies matter, and which bodies are yet to emerge as critical matters of concern. Excerpt from Bodies that Matter by Judith Butler is licensed All Rights Reserved and is used here under Fair Use exception.

You can see in Butler’s work how deconstruction plays a role in queer theory approaches to texts. What do you think of her approach to sexuality and gender? Which bodies matter? Why is this question important for literary scholars, and how can we use literary texts to answer the question?

In our next section, we’ll look at some ways that these theories can be used to analyze literary texts.

Using Feminist, Postfeminist, and Queer Theory as a Critical Approach

As you can see from the introduction and the examples of scholarship that we read, there’s some overlap in the concepts of these three critical approaches. One of the first choices you have to make when working with a text is deciding which theory to use. Below I’ve outlined some ideas that you might explore.

- Character Analysis: Examine the portrayal of characters, paying attention to how gender roles and stereotypes shape their identities. Consider the agency, autonomy, and representation of both male and female characters, and analyze how their interactions contribute to or challenge traditional gender norms.

- Theme Exploration: Investigate themes related to gender, power dynamics, and patriarchy within the text. Explore how the narrative addresses issues such as sexism, women’s rights, and the construction of femininity and masculinity. Consider how the themes may reflect or critique societal attitudes towards gender.

- Language and Symbolism: Analyze the language used in the text, including the representation of gender through linguistic choices. Examine symbols and metaphors related to gender and sexuality. Identify instances of language that may reinforce or subvert traditional gender roles, and explore how these linguistic elements contribute to the overall meaning of the work.

- Authorial Intent and Context: Investigate the author’s background, motivations, and societal context. Consider how the author’s personal experiences and the cultural milieu may have influenced their portrayal of gender. Analyze the author’s stance on feminist issues and whether the text aligns with or challenges feminist principles.

- Intersectionality: Take an intersectional approach by considering how factors such as race, class, sexuality, and other identity markers intersect with gender in the text. Explore how different forms of oppression and privilege intersect, shaping the experiences of characters and influencing the overall thematic landscape of the literary work.

Postfeminist

- Interrogating Postfeminist Tropes: Examine the text for elements that align with or challenge postfeminist tropes, such as the notion of individual empowerment, choice feminism, or the idea that traditional gender roles are no longer relevant. Analyze how the narrative engages with or subverts these postfeminist ideals.

- Exploring Ambiguities and Contradictions: Investigate contradictions and ambiguities within the text regarding gender and sexuality. Postfeminist criticism often acknowledges the complexities of contemporary gender dynamics, so analyze instances where the text may present conflicting perspectives on issues like agency, equality, and empowerment.

- Media and Pop Culture Influences: Consider the influence of media and popular culture on the text. Postfeminist criticism often examines how cultural narratives and media representations of gender impact literature. Analyze how the text responds to or reflects contemporary media portrayals of gender roles and expectations.

- Global and Cultural Perspectives: Take a global and cultural perspective by exploring how the text addresses postfeminist ideas in different cultural contexts. Analyze how the narrative engages with issues of globalization, intersectionality, and diverse cultural perspectives on gender and feminism.

- Temporal Considerations: Examine how the temporal setting of the text influences its engagement with postfeminist ideas. Consider whether the narrative reflects a specific historical moment or if it transcends temporal boundaries. Analyze how societal shifts over time may be reflected in the text’s treatment of gender issues.

- Deconstructing Norms and Binaries: Utilize Queer Theory to deconstruct traditional norms and binaries related to gender and sexuality within the text. Explore how the narrative challenges or reinforces heteronormative assumptions, and analyze characters or relationships that subvert or resist conventional categories.

- Examining Queer Identities: Focus on the exploration and representation of queer identities within the text. Consider how characters navigate and express their sexualities and gender identities. Analyze the nuances of queer experiences and the ways in which the text contributes to a more expansive understanding of LGBTQ+ identities.

- Language and Subversion: Analyze the language used in the text with a Queer Theory lens. Examine linguistic choices that challenge or reinforce societal norms related to gender and sexuality. Explore how the text employs language to subvert or resist heteronormative structures.

- Queer Time and Space: Consider how the concept of queer time and space is represented in the text. Queer Theory often explores non-linear or non-normative temporalities and spatialities. Analyze how the narrative disrupts conventional timelines or spatial arrangements to create alternative queer realities.

- Intersectionality within Queer Narratives: Take an intersectional approach within the framework of Queer Theory. Analyze how factors such as race, class, and ethnicity intersect with queer identities in the text. Explore the intersections of different marginalized identities to understand the complexities of lived experiences.

Applying Gender Criticisms to Literary Texts

As with our other critical approaches, we will start with a close reading of the poem below (we’ll do this together in class or as part of the recorded lecture for this chapter). In your close reading, you’ll focus on gender, stereotypes, the patriarchy, heteronormative writing, etc. With feminist, postfeminist, and queer theory criticism, you might look to outside sources, especially if you are considering the author’s gender identity or sexuality, or you might bring your own knowledge and lived experience to the text.

The poem below was written by Mary Robinson, an early Romantic English poet. Though her works were quite popular when she was alive, you may not have heard of her. However, you’re probably familiar with her male contemporaries William Blake, William Wordsworth, Lord Byron, John Keats, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, or Percy Bysshe Shelley.

Keep in mind that reading this poem is thus itself a feminist act. When we choose to include historical voices of woman that were previously excluded, we are doing feminist criticism.

“January, 1795”

BY MARY ROBINSON

Pavement slipp’ry, people sneezing, Lords in ermine, beggars freezing; Titled gluttons dainties carving, Genius in a garret starving.

Lofty mansions, warm and spacious; Courtiers cringing and voracious; Misers scarce the wretched heeding; Gallant soldiers fighting, bleeding.

Wives who laugh at passive spouses; Theatres, and meeting-houses; Balls, where simp’ring misses languish; Hospitals, and groans of anguish.

Arts and sciences bewailing; Commerce drooping, credit failing; Placemen mocking subjects loyal; Separations, weddings royal.

Authors who can’t earn a dinner; Many a subtle rogue a winner; Fugitives for shelter seeking; Misers hoarding, tradesmen breaking.

Taste and talents quite deserted; All the laws of truth perverted; Arrogance o’er merit soaring; Merit silently deploring.

Ladies gambling night and morning; Fools the works of genius scorning; Ancient dames for girls mistaken, Youthful damsels quite forsaken.

Some in luxury delighting; More in talking than in fighting; Lovers old, and beaux decrepid; Lordlings empty and insipid.

Poets, painters, and musicians; Lawyers, doctors, politicians: Pamphlets, newspapers, and odes, Seeking fame by diff’rent roads.

Gallant souls with empty purses; Gen’rals only fit for nurses; School-boys, smit with martial spirit, Taking place of vet’ran merit.

Honest men who can’t get places, Knaves who shew unblushing faces; Ruin hasten’d, peace retarded; Candor spurn’d, and art rewarded.

“January, 1795” by Mary Robinson is in the Public Domain.

Questions (Feminist and Postfeminist Criticism)

- What evidence of gender stereotypes can you find in the text?

- What evidence of patriarchy and power structure do you see? How is this evidence supported by historical context? Consider, for example, the 1794 contemporary poem “London” by William Blake. These two poems have similar themes. How does the male poet Blake’s treatment of this theme compare with the female poet Mary Robinson’s work? How have these two works and authors differed in their critical reception?

- Who is the likely contemporary audience for Mary Robinson’s poetry? Who is the audience today? What about the audience during the 1940s and 50s, when New Criticism was popular? How would these three audiences view feminism, patriarchy, and gender roles differently?

- Do a search for Mary Robinson’s work in JSTOR. Then do a search for William Blake. How do the two authors compare in terms of scholarship produced on their work? Do you see anything significant about the dates of the scholarship? The authors? The critical lenses that are applied?

- Do you see any contradictions and ambiguities within the text regarding gender and sexuality? What about evidence for subversion of traditional gender roles?

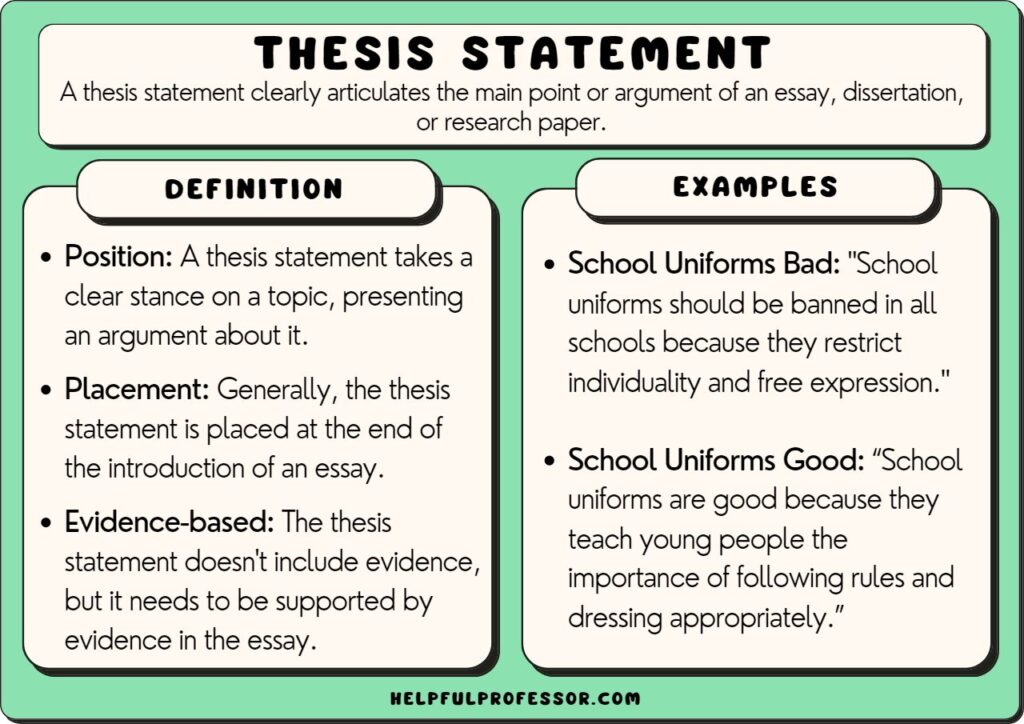

Example of a feminist thesis statement: While William Blake’s “London” and Mary Robinson’s “January, 1795” share similar themes with similar levels of artistry, Robinson’s work and critical reception demonstrates the effects of 18th-century patriarchal power structures that kept even the most brilliant women in their place.

Example of a postfeminist thesis statement: Mary Robinson’s “January, 1975” slyly subverts gender norms and expectations with a brilliance that transcends the confines of traditional eighteenth century gender roles.

To practice queer theory, let’s turn to a more contemporary text. “The Eyepatch” by transgender author and scholar Cassandra Arc follows a gender-neutral protagonist as they navigate an ambiguous space. This short story questions who sees and who is seen in heteronormative spaces, as well as exploring what it means to see yourself as queer.

“The Eyepatch”

The lightning didn’t kill me, though it should’ve. The bolt pierced my eyes, gifted curse from Zeus or Typhon or God. I remember waking up in that hospital, everything was black. I felt bandages, pain, fire. I tried to sit up, but a hand gently pushed me back into the bed. I heard the shuffling of feet and the sound of scrubs rubbing against each other. I smelled the pungent disinfectant in the air. I heard the slow methodical beep of a heart rate monitor. That incessant blip-blip-blip was my heart rate. I heard the thunder of my heart beating to the same methodical rhythm. A metronome to a wordless melody of ignorance, an elegy to blindness.

I wasn’t awake long. They put me back to sleep. To salvage my face. My burned face, my charred face. I should’ve died. The next time I woke the bandages were gone. I could see the doctors, but I couldn’t see me. They wouldn’t let me see me, told me they would fix my face, make it look good again. I didn’t trust them. The doctors thought their faces were pretty. They weren’t. I asked to see my face. They wouldn’t let me. I’m lucky to be alive, that’s what they said. I’m lucky I can see.

But some things I can’t see. They left the eyepatch on my left eye. Told me the left eye would never work again. My right eye can’t see everything. It sees the doctors, their heads swathed in sterile caps, their wrinkled noses, their empty eyes. It sees the nurses, their exhaustion, their bitterness. It sees the bleak beige walls and the tiny tinny television hanging in the corner by the laminated wood door. It sees the plastic bag of fluid hanging from the metal rack on wheels, the plastic instruments and the fluorescent light panel above my head. But it can’t see my mom, it can’t see my sister. It can’t see myself. They never believe me.

My mom comes to visit me on the third day I’m awake. I hear her enter, smell her usual perfume, lilac with a hint of dirt and rain. I feel her hand hold mine, warmth and comfort and kindness. My right eye can’t see her. She came from the garden to see me, to make sure I’m okay. My right eye can’t see my mom. The doctors don’t believe me. My mom believes me.

The doctors pull her away from me. They say they need to fix my face. She can see me tomorrow. I smell the anesthesia and hear the spurt of the needle as they test to make sure no air bubbles formed in the syringe. I hear my mom crying. She assures me she’ll come back tomorrow. I can’t see her tears. They put me back to sleep.

In my dreams I can see them, my mother and sister. There is no eyepatch on my left eye; it can see them, and it can see me, reflected in the water. We swim across the pond to the island with the tree in the center. The reeds grow tall along the banks. The water smells of fish shit and moss. the reflection is murky except for the shallow blue eyes.

The reflection is broken by a ripple. My sister swims to me, wraps her arms around me, then splashes water directly into my face. Some droplets stick to my forehead and nose, like beads of cold sweat. She giggles, a grin emerges on her freckled face. Her wet blonde hair has strands of moss hanging from it. I smile back and with a quick flick of my wrist she too is drenched. I feel peace from the water. My mother calls us to shore. Storm clouds, she says. The lightning might kill you. That’s what she said then. I didn’t believe her. Thunder echoes like the heartbeat of the sky.

The doctors wake me up. They have thunder too. I cannot see them, can’t see anything. Bandages surround my face. My face is fixed. That’s what they claim. I didn’t see anything wrong before. They wouldn’t let me see me. It’s a miracle. I’m lucky to be alive. I don’t believe them. They apologize for not being able to fix my eye.

My sister comes with my mom today. I can’t see her. She believes me, reminds me about the lightning. It could’ve killed me. When she learns I can’t see her, she cackles. She says she’ll have fun when I come home. She asks when I’ll come home.

I don’t know when I’ll come home. The doctors don’t know. I should’ve died. They want to keep me. My mother wants to take me. They shout at each other. My sister holds my left hand. I can’t see her hand, or mine.

The doctors remove the bandages. They show me a mirror. I see behind me, but I don’t see me . I see the eyepatch float. When I try to remove it the doctors stop me. My eye is too damaged. They tell me to never remove the eyepatch. They hold up a vase. My mom brought me flowers. I can’t see the flowers. They don’t believe me. Their voices are angry. Stop being childish, they say. I lie and say I see the flowers.

Once one of the nurses I can’t see, he brought me food from outside. I saw the bag float in the room. I heard his footsteps. He handed me the brown paper bag and told me to enjoy. He sounded old. I felt a band of metal on his left-hand ring finger when I took the bag. The smell of chicken nuggets and French fries pierced the stale aroma of bleach and disinfectant. I heard the edge of the bed creak, the cushion indented slightly. The invisible nurse told wild tales of dragons and monsters while I ate. He didn’t know when I’ll be home. He watered invisible flowers before leaving. I fell back asleep.

In my dreams I’m still swimming. The sun is blocked by clouds. Drops of rain hit my hair. Mother calls from the cabin on the shore. My sister runs out of the water, her leg kicks water into my eyes. I’m blinded for a moment. I don’t leave. I stay in the water, dropping my eyes level with the water. They both hear the thunder. I don’t hear the thunder. They both see the lightning.

All I feel is heat. I’m blind. The lightning should’ve killed me. The lightning in my eyes, lucky to be alive. My sister screams for help. Smell the ozone. Pungent and sweet. I don’t scream, I can’t scream. I’m dead. I’m alive. The lightning killed me. I can’t see my mom. I can’t see my sister. I can’t see the flowers. The lightning saved me. I can see the doctors, I can see the nurses, I can see the hospital.

The lightning killed me, that’s what they said. They brought me back with lightning, pads of metal, artificial energy. My eye is broken, the one the lightning struck. Three minutes. That’s what they told me. Three minutes of death. My face was burned. I can’t see it. They fixed it.

The doctors worried my body was broken too. The lightning still might kill me. They say I need to move, I need to walk. Lightning causes paralysis, or weakness. They bring in a special doctor. I can’t see this doctor. The other doctors leave. The invisible doctor takes me to a room for walking practice. I think I walk just fine. They hold me anyway. Crutches line the walls, pairs of metal handrails take up the center, and exercise equipment sits off to the right side. The invisible doctor lets go and I fall. My hands are too slow to catch me. My face hits one of the many black foam squares that make up the floor. I turn my head left and see the eyepatch almost fall off in the mirror on the wall. For a second, I think I see me, but I can’t see me. The invisible doctor fixes it and helps me to my feet. They tell me to be like a tree, that I’ll be okay. That I’ll be able to walk again soon. They tell me when I can walk I will go home. I place my hands on the rails. The metal is cold. The doctor yelps in shock and withdraws their hand; it was just static. My arms are weak but they hold me. My legs move slowly, but I can’t walk without the rails.

The invisible doctor takes me back after a while. They tell me I did good work. It’s a miracle I can still move. They tell me lightning takes people’s movement. The lightning should’ve killed me. That’s what they say. They tell me strength should come back to me. Lightning steals that too. Lightning can’t keep strength like it keeps movement.

My mom comes back again. She brings me the manatee, Juno. I can see Juno. Soft gray fabric, small black plastic eyes. I hold her tightly in my arms. Mom wants me home. The doctors still won’t let her take me. Juno will keep me safe, that’s what she said. She brings me homework too, and videos of teachers explaining how the world works. I can see them. I can’t see my mom.

I miss the smell of earth when my mom leaves. I want to smell her garden again. To swim in the pond and feel the moss brush against my skin. I want to feel the peace of the water and hear the crickets sing their lullaby. The invisible doctor tells me I will. They tell me I need to steal my strength from the lightning. They take me back to that room for walking. I only need one hand to guide me now. They tell me I’ll go home soon. They tell me I’m stronger than lightning. I still can’t see them.

Back in my room I learn about lightning. It’s hotter than the sun. I remember the heat I felt and wonder if that’s how it feels to touch the surface of a star. The video says that direct strikes are usually fatal. I’m lucky to be alive. I hold Juno tightly.

It takes a month to steal my strength back from the lightning. I walk without holding the rails. The invisible doctor applauds me and tells me I’m ready to go home. They call my mom. I still can’t see my mom.

I can’t see the trees with my right eye, my good eye. I know where they should be by the shaded patches of dirt in the ground. I can see the grass, the road, the dirt covered green Volvo Station wagon, Mom’s car. My sister shouts for joy and runs toward me. I fall to the ground. Her arms squeeze Juno into my chest. I can’t see my sister.

Mom drives me to the cabin. I can see the towering buildings of the city. In the reflection of the tinted glass, I see the station wagon. The eyepatch floats in the window right above Juno’s head. Mom tells me about what she’ll make for dinner. She killed one of the chickens and plucked carrots and celery from the ground. Soup gives strength. That’s what she said. She reminds me that I’m lucky to be alive.

I can’t see the reeds. Mom stops the car in front of the cabin. I can’t see the cabin, nor the rustic wood threshold. Mom helps me across it. The hand-carved wooden table is invisible, but I can see the small electric stove. I smell the soup, hear the water boil, guide my hand along the wood of the narrow hallway to help me walk. I can’t see my bedroom, nor the bed alcove carved into the wall. My mattress floats in the air as if by magic. I can see the plastic desk my mom bought me for school, and the lightbulb in the ceiling. I see wires in invisible walls.

My sister wants to play. She tugs on my arm. I set Juno into the bed alcove and feel my way back to the main room. Mom reminds me to be careful. She tells my sister to be gentle. She reminds us both that I can’t take off my eyepatch. We both take off our shoes.

My sister guides me to the shore. I enjoy the sensation of dirt beneath my feet and the occasional pain of a rock. We move slowly, some of my strength still belongs to the lightning. She runs in. I can’t see the pond. I can’t see the moss in the pond. I can’t see my sister. My sister asks about the eyepatch. She wants to know why I can’t take it off. I don’t know. She asks about my eye. The dark one. The one filled with abyss. The right eye. She asks why it’s dark. I don’t know. I put my foot in the invisible water. My sister jumps out. Something shocked her. She thinks I shocked her. She gets back in.

I stay close to the shore I can’t see. I don’t want to drown. I don’t want my eyes near the water. There are no storm clouds today. I fiddle with moss between my toes. Mom calls us in for dinner. My sister runs ahead. I try walking on my own. I trip over a tree root that I couldn’t see. I fall and hit my chin on the ground. The eyepatch slides up a bit. I quickly push it back down before it can come off. I can’t take off my eyepatch.

My mom hears the thud and comes running. She helps me to my feet, guides me back to the cabin, and sits me at the table. She brings me a bowl of soup, tells me I need to be careful. She wants me to stay alive. I sip the soup and listen to her sing while she cleans the soup pot. I can’t see my mom.

When I sleep, I dream of before. Before the lightning stole my left eye. Before it stole my strength. I dream of the pond. I dream of the old willow tree on the island. Its dark drooping branches blossoming every spring. The leaves fall on the pond. Nature’s Navy of little boats. The tree is stronger than lightning. I am the tree. I want to see the tree again.

My sister tells me she’ll guide me to the island. I refuse. I can’t see the tree, or the water. My eyes would have to be close to it. The eyepatch might come off. I spend the day holding Juno. My mom brings me a sandwich and sits with me a while. I only know she’s there from the sound of her bouncing leg. She’s nervous. She doesn’t smell of the garden yet. She won’t smell of the garden today. I want to smell of the garden, but I can’t see the garden.

In the evening I sit outside the cabin and listen to the crickets. I’m lucky to be alive. The lightning didn’t kill me. I scratch at an itch under the eyepatch. I feel a shock in my hand and pull it back. I smell the ozone on my fingertip. In my mind I’m in the water again. I remember the heat, the pain. My mom comes running when I scream. She puts Juno in my arms. I feel safe again. I am stronger than the lightning. The lightning didn’t kill me.

While I sleep I am the tree, standing tall, guarding my island. The lightning wants to take it. It strikes at the water around me, burning my Navy of leaves. Once it struck me, but the rain extinguished its flames. I grew back stronger. My Navy rebuilt. The lightning always comes back. I am always stronger.

My sister and I play in the lake. I go out deeper today. My legs can tell how deep I am. We go to the tree. The lightning couldn’t steal the ability to swim. I follow the sound of my sister’s splashing. We push through invisible reeds, I feel the plants surround me. My sister holds my hand and guides me through the canopy of branches. I feel the incomplete ships of Nature’s Navy brush against my face. She puts my hand against the tree. I guide my hand along it until I find the once charred wood where lightning burned it. The lightning should’ve killed us.

My sister and I sit under the tree for a while. I feel the bugs occasionally crawl across my hands. She rests her shoulder on mine. I’m lucky to be alive. The lightning didn’t kill us.

We walk back to the shore. I feel the water, and one of Nature’s boats brush against my foot and look down. I still can’t see the water. I can’t see myself. I can see the Navy. The floating leaves atop the tranquil pond. The tears begin to fall. My sister asks why the tears from beneath the eyepatch are white as ash. I wish I knew.

The crickets sing again that evening. Tonight, they sing the ballad of the tree. Loud and harmonic. I whisper my thanks into the wind. The crickets whistle back. They believe me.

In the morning I wake up before anyone else. I shuffle through the halls and out to the porch to listen to the morning bird song. I let my head weave side to side in tune with their melody. I dance across invisible dirt. A laugh escapes my lips. I jump into invisible water. I sail with Nature’s Navy to the tree.

My soul sits atop resilient roots. Hands find the burned wood, where the lightning almost killed it. I bring the left hand to the eyepatch, where the lightning almost killed me. The wind blows through the leaves. Splashes echo from the opposite shore, sounds of someone swimming. Thunder echoes from my stomach, I rise to return home. Gallivanting down the invisible slope back towards my invisible home.

I trip across a root near the water. The eyepatch sinks beneath the surface of the lake. I yank my head back. The eyepatch slips off. My left hand covers my eye. A shock forces me to pull it away. The eyelid flutters opened. I see the lightning. Nature’s Navy set ablaze by my gaze. My eye touches the sun again as the lightning leaves. The tree set ablaze by my gaze. The crickets echo a lament. The birds resound a harmonizing elegy. The drooping branches fall lower, as if bowing. I bow in return. The splashing water calms.

My left eye sees the water, sees the earth, sees myself. Authentic and whole. It observes my leaves of joy, fingers stretched in shallows. My left eye witnesses my roots of kindness, feet planted on solid shores. It beholds the resilience of my trunk, a beautiful body. The eyepatch floats in the water. I perceive my eyes again, the dark one and the white. my black and white tears drift across the surface of water. Someone shuffles the dirt behind me. I turn with a smile on my face.

Cassandra Arc is an autistic trans woman living in Portland, Oregon. In her writing she likes to focus on themes of healing, gender identity issues, and nature as a means of understanding authenticity. This story was originally published in the Talking River Review and is reprinted here by permission of the author (All Rights Reserved).

- Who is the narrator of this story? What do we know about their gender? How do we know this? What does the lightning signify?

- What does the eyepatch represent? When the narrator says, “I see behind me, but I don’t see me,” what does this mean? What ideas about social constructs are present in this narrative, and how does the story subvert those social constructs?

- How do characters navigate and express their gender identities in the text? Does the story expand your understanding of the queer experience? In what ways? What do you think about the way some things can’t be seen and some things can in the story? How might this experience relate to being queer?

- How are time and space treated in this story?

- How does the story subvert or resist conventional categories?

Example of a queer theory thesis statement: In “The Eyepatch” by Cassandra Arc, the binary oppositions of light, darkness, sight, and blindness are used to subvert heteronormative structures, deconstructing artificially constructed binaries to capture the experience of being in the closet and the explosive nature of coming out.

Limitations of Gender Criticisms

While these approaches offer interesting and important insights into the ways that gender and sexuality exist in texts, they also have some limitations. Here are some potential drawbacks:

- Essentialism: Feminist theory may sometimes be criticized for essentializing gender experiences, assuming a universal women’s experience that overlooks the diversity of women’s lives.

- Neglect of Other Identities: The focus on gender in feminist theory may overshadow other intersecting identities such as race, class, and sexuality, limiting the analysis of how these factors contribute to oppression or privilege.

- Overlooking Male Perspectives: In some instances, feminist theory may be perceived as neglecting the examination of male characters or perspectives, potentially reinforcing gender binaries rather than deconstructing them.

- Historical and Cultural Context: Feminist theory, while valuable, may not always adequately address the historical and cultural contexts of literary works, potentially overlooking shifts in societal attitudes towards gender over time.

- Oversimplification of Feminist Goals: Post-feminist criticism may be criticized for oversimplifying or prematurely declaring the achievement of feminist goals, potentially obscuring persistent gender inequalities.

- Individualism and Choice Feminism: The emphasis on individual empowerment in post-feminist criticism, often associated with choice feminism, may overlook systemic issues and structural inequalities that continue to affect women’s lives.

- Lack of Intersectionality: Post-feminist approaches may sometimes neglect intersectionality, overlooking the interconnectedness of gender with race, class, and other identity factors, which can limit a comprehensive understanding of oppression.

- Commodification of Feminism: Critics argue that post-feminism can lead to the commodification of feminist ideals, with feminist imagery and language used for commercial purposes, potentially diluting the transformative goals of feminism.

- Complexity and Jargon: Queer Theory can be complex and may use specialized language, making it challenging for some readers to engage with and understand, potentially creating barriers to entry for students and scholars.

- Overemphasis on Textual Deconstruction: Critics argue that Queer Theory may sometimes prioritize textual deconstruction over concrete political action, leading to concerns about the practical impact of this theoretical approach on real-world LGBTQ+ issues.

- Challenges in Application: Queer Theory’s emphasis on fluidity and resistance to fixed categories can make it challenging to apply consistently, as it may resist clear definitions and frameworks, making it more subjective in its interpretation.

- Limited Representation: While Queer Theory aims to deconstruct norms, some critics argue that it may still primarily focus on certain aspects of queer experiences, potentially neglecting the diversity within the LGBTQ+ spectrum and reinforcing certain stereotypes.

Gender Scholars

- Simone de Beauvoir (1908-1986): A French existentialist philosopher and writer, de Beauvoir is best known for her groundbreaking work “The Second Sex,” which explored the oppression of women and laid the groundwork for feminist literary theory.

- Virginia Woolf (1882-1941): A celebrated English writer, Woolf is known for her novels such as “Mrs. Dalloway” and “Orlando.” Her works often engaged with feminist themes and issues of gender identity.

- bell hooks (1952-2021): An American author, feminist, and social activist, hooks wrote extensively on issues of race, class, and gender. Her works, such as “Ain’t I a Woman” and “The Feminist Theory from Margin to Center,” are essential in feminist scholarship.

- Adrienne Rich (1929-2012): An American poet and essayist, Rich’s poetry and prose explored themes of feminism, identity, and social justice. Her collection of essays, “Of Woman Born,” is a notable work in feminist literary criticism.

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak: An Indian-American literary theorist and philosopher, Spivak is known for her work in postcolonialism and deconstruction. Her essay “Can the Subaltern Speak?” is a key text in postcolonial and feminist studies.

- Susan Faludi: An American journalist and author, Faludi’s work often explores issues related to gender and feminism. Her book “Backlash: The Undeclared War Against American Women” critically examines the societal responses to feminism.

- Camille Paglia: An American cultural critic and author, Paglia is known for her provocative views on gender and sexuality. Her work, including “Sexual Personae,” challenges conventional feminist perspectives.

- Rosalind Gill: A British cultural and media studies scholar, Gill has written extensively on gender, media, and postfeminism. Her work explores the intersection of popular culture and contemporary feminist thought.

- Laura Kipnis: An American cultural critic and essayist, Kipnis has written on topics related to gender, sexuality, and contemporary culture. Her book “Against Love: A Polemic” challenges conventional ideas about love and relationships.

- Judith Butler: A foundational figure in both feminist and queer theory, Judith Butler has made profound contributions to the understanding of gender and sexuality. Their work Gender Trouble has been influential in shaping queer theoretical discourse.

- Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick: An influential scholar in queer studies, Sedgwick’s works, such as Epistemology of the Closet , have contributed to the understanding of queer identities and the impact of societal norms on the construction of sexuality.

- Michel Foucault: Although not exclusively a queer theorist, Foucault’s ideas on power, knowledge, and sexuality laid the groundwork for many aspects of queer theory. His works, including The History of Sexuality, are foundational in queer studies.

- Teresa de Lauretis: An Italian-American scholar, de Lauretis has contributed significantly to feminist and queer theory. Her work Queer Theory: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities explores the complexities of sexuality and identity.

- Jack Halberstam: A gender and queer studies scholar, Halberstam’s works, including Female Masculinity and In a Queer Time and Place, engage with issues of gender nonconformity and the temporalities of queer experience.

- Annamarie Jagose: A New Zealand-born scholar, Jagose has written extensively on queer theory. Her book Queer Theory: An Introduction provides a comprehensive overview of key concepts within the field.

- Leo Bersani: An American literary theorist, Bersani’s work often intersects with queer theory. His explorations of intimacy, desire, and the complexities of same-sex relationships have been influential in queer studies.

Further Reading

- Aravind, Athulya. Transformations of Sappho: Late 18th Century to 1900. Senior Thesis written for Department of English, Northeastern University. https://www.sfu.ca/~decaste/OISE/page2/files/deBeauvoirIntro.pdf This is a wonderful example of a student-written feminist approach to English Romantic poetry.

- Banet-Weiser, Sarah, Rosalind Gill, and Catherine Rottenberg. “Postfeminism, Popular Feminism and Neoliberal Feminism? Sarah Banet-Weiser, Rosalind Gill and Catherine Rottenberg in Conversation.” Feminist Theory 21.1 (2020): 3-24.

- Butler, Judith. Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of Sex . Taylor & Francis, 2011.

- Butler, Judith. Gender Trouble . Routledge, 2002.

- de Beauvoir, Simone. The Second Sex. Trans. H.M. Parshley. 1956.

- De Lauretis, Teresa. “Eccentric Subjects: Feminist Theory and Historical Consciousness.” Feminist Studies 16.1 (1990): 115-150.

- Gill, Rosalind. “Postfeminist Media Culture: Elements of a Sensibility.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 10.2 (2007): 147-166.

- Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction. Trans. Robert Hurley. Vintage, 1990.

- Foucault, Michel. The History of Sexuality, Vol. 2: The Use of Pleasure . Vintage, 2012.

- Halberstam, Jack. Trans: A Quick and Quirky Account of Gender Variability . Vol. 3. Univ of California Press, 2017.

- hooks, bell. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center . Pluto Press, 2000.

- hooks, bell. “Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness.” Women, Knowledge, and Reality . Routledge, 2015. 48-55.

- Jagose, Annamarie. Queer Theory: An Introduction . NYU Press, 1996.

- Miller, Jennifer. “Thirty Years of Queer Theory.” In Introduction to LGBTQ+ Studies: A Multidisciplinary Approach. Pressbooks. https://milnepublishing.geneseo.edu/introlgbtqstudies/chapter/thirty-years-of-queer-theory/

- Paglia, Camille. Sexual Personae: Art and Decadence from Nefertiti to Emily Dickinson . Yale University Press, 1990.

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Touching Feeling: Affect, Pedagogy, Performativity . Duke University Press, 2003.

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. Epistemology of the Closet . Univ of California Press, 2008.

- Spivak, Gayatri Chakravorty. The Spivak Reader: Selected works of Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak . Psychology Press, 1996.

Critical Worlds Copyright © 2024 by Liza Long is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- Utility Menu

Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality

- Mailing List

- Past Thesis Topics

| Year | ||

|

| ||

| 2024 | Government | |

| 2024 | History and Literature | |

| 2024 | Government | |

| 2024 | English | |

| 2024 | Detransition, Baby Nevada | English |

| 2024 | History and Science | |

| 2024 | History and Science | |

|

| ||

| 2023 | ||

| 2023 | Classics | |

| 2023 | Government | |

| 2023 | History & Literature | |

| 2023 | Century Imperial Russia | History & Literature |

| 2023 | | Social Studies |

| 2023 | | Social Studies |

| 2023 | Social Studies | |

| 2023 | Social Studies | |

| 2023 | : | Sociology |

| 2023 |

| Sociology |

| 2023 | Theater, Dance & Media | |

| 2023 | Theater, Dance & Media | |

| 2022 |

| |

| 2022 | African and African-American Studies | |

| 2022 | African and African-American Studies | |

| 2022 | Government | |

| 2022 | Government | |

| 2022 | History | |

| 2022 | History and Literature | |

| 2022 | History and Science | |

| 2022 | Social Studies | |

| 2022 | Social Studies | |

| 2022 | Social Studies | |

| 2021 | Gender Codes: Exploring Malaysia’s Gender Parity in Computer Science | Computer Science |

| 2021 | The Voice of Technology: Understanding The Work Of Feminine Voice Assistants and the Feminization of the Interface | Computer Science |

| 2021 | Whose Voices, Whose Values? Environmental Policy Effects Ofextra-Community Sovereignty Advocacy | Environmental Science and Public Policy |

| 2021 | “Felons, Not Families”: The Construction of Immigrant Criminality in Obama-Era Policies and Discourses, 2011-2016 | History and Literature |

| 2021 | Seeing Beyond the Binary: The Photographic Construction of Queer Identity in Interwar Paris and Berlin | History and Literature |

| 2021 | Iconic Market Women: The Unsung Heroines of Post-Colonial Ghana (1960s-1990s) | History and Literature: Ethnic Studies |

| 2021 | From Stove Polish to the She-E-O: The Historical Relationship Between the American Feminist Movement and Consumer Culture | Social Studies |

| 2021 | “Interstitial Existence,” De-Personification, and Black Women’s Resistance to Police Brutality | Social Studies |

| 2021 | #Metoo Meets #Blm: Understanding Black Feminist Anti-Violence Activism in the United States | Social Studies |

| 2021 | "Why Won’t Anyone Fight For Us?”: A Contemporary Class Analysis of the Positions and Politics of H-1b and H-4 Visa Holders | Social Studies |

| 2020 | A Feminist Scientific Exploration of Minority Stress and Eating Pathology in Transgender Adolescents | |

| 2020 | From Decolonization to LGBTQ + Liberation: LGBTQ+ Activism, Colonial History and National Identity in Guyana | |

| 2020 | La Pocha, Sin Raíces / Spoiled Fruit, Without Roots: A Genealogy of Tejana Borderland Imaginaries | Anthropology |

| 2020 | Capturing Authenticity in Indian Transmasculine Identity: Design of a Novel Penile Prosthesis | Biomedical Engineering |

| 2020 | More Than Missing: Analyzing Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women Policy Trajectories in the United States and Canada, 2015-2019 | Government |

| 2020 | “Almost Perfect”: The Cleansing and Erasure of Undocumented and Queer Identities through Performance of Model Families and Citizensh | History & Literature |

| 2020 | "He Needs a New Belt:” Queerness, Homonationalism, and the Racial and Sexual Dimensions of Passing in Israeli Cinema | History & Literature |

| 2020 | Our Healthy Bodies, Our Healthy Selves: Community Women's Health Centers as Collaborative Sites of Politics, Education, and Care | History of Science |

| 2020 | “No Way to Speak of Myself”: Lived and Literary Resistance to Gender in French | Romance Languages and Literatures |

| 2020 | Through Eastern European Eyes and Under the Western Gaze: The (Un)Feminist Face of the Russo-Ukrainian War | Slavic Languages and Literatures |

| 2020 | Subversion and Subordination: The Materialization of the YouTube Beauty Community in Everyday Reality | Social Studies |

| 2019 | Mirror, Mirror, On The Wall, Why Can’t I See Myself At All?: A Close Reading of Children’s Picture Books Featuring Gender Expansive Children of Color | African and African-American Studies |

| 2019 | Dilating Health, Healthcare, and Well-Being: Experiences of LGBTQ+ Thai People | Biomedical Engineering |

| 2019 | The Consociationalist Culprit: Explaining Women’s Lack of Political Representation in Northern Ireland | Government |

| 2019 | Queering the Political Sphere: Play, Performance, and Civil Society with the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence in San Francisco, 1979-1999 | Government |

| 2019 | Playing With Power: Kink, Race, and Desire | History and Literature |

| 2019 | “Take Root:” Community Formation at the San Francisco Chinatown Branch Public Library, 1970s-1990s | History and Literature |

| 2018 | Fetal Tomfoolery: Comedy, Activism, and Reproductive Justice in the Pro-Abortion Work of the Lady Parts Justice League |

|

| 2018 | And They're Saying It's Because of the Internet: An Exploration of Sexuality Urban Legends Online | Folklore and Mythology |

| 2018 | (In)visibly Queer: Assessing Disparities in the Adjudication of U.S. LGBTQ Asylum Cases | Government |

| 2017 | Enough for Today |

|

| 2017 | Radical Appropriations: A Cultural History and Critical Theorization of Cultural Appropriation in Drag Performance | |

| 2017 | Surviving Safe Spaces: Exploring Survivor Narratives and Community-Based Responses to LGBTQ Intimate Partner Violence | |

| 2017 | “The Cruelest of All Pains”: Birth, Compassion, and the Female Body in | English |

| 2017 | Virtually Normal? How “Initiation” Shapes the Pursuit of Modern Gay Relationships | Social Studies |

| 2017 | How Stigma Impacts Mental Health: The Minority Stress Model and Unwed Mothers in South Korea | Sociology |