- Member Login

- Library Patron Login

- Get a Free Issue of our Ezine! Claim

Reviews of Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides

Summary | Excerpt | Reading Guide | Reviews | Read-Alikes | Genres & Themes | Author Bio

- Critics' Consensus:

- Readers' Rating:

- First Published:

- Sep 1, 2002, 544 pages

- Sep 2003, 544 pages

- Literary Fiction

- Midwest, USA

- Ind. Mich. Ohio

- Adult Books From Child's Perspective

- Coming of Age

- Adult-YA Crossover Fiction

- Immigrants & Expats

- Physical & Mental Differences

- Publication Information

- Write a Review

- Buy This Book

About This Book

- Reading Guide

Book Summary

To understand why Calliope is not like other girls, she has to uncover a guilty family secret, and the astonishing genetic history that turns Callie into Cal. Lyrical and thrilling, Middlesex is an exhilarating reinvention of the American epic.

Middlesex tells the breathtaking story of Calliope Stephanides, and three generations of the Greek-American Stephanides family, who travel from a tiny village overlooking Mount Olympus in Asia Minor to Prohibition-era Detroit, witnessing its glory days as the Motor City and the race riots of 1967 before moving out to the tree-lined streets of suburban Grosse Pointe, Michigan. To understand why Calliope is not like other girls, she has to uncover a guilty family secret, and the astonishing genetic history that turns Callie into Cal, one of the most audacious and wondrous narrators in contemporary fiction. Lyrical and thrilling, Middlesex is an exhilarating reinvention of the American epic.

The Silver Spoon

I was born twice: first, as a baby girl, on a remarkably smogless Detroit day in January of 1960; and then again, as a teenage boy, in an emergency room near Petoskey, Michigan, in August of 1974. Specialized readers may have come across me in Dr. Peter Luce's study, "Gender Identity in 5-Alpha-Reductase Pseudohermaphrodites," published in the Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology in 1975. Or maybe you've seen my photograph in chapter sixteen of the now sadly outdated Genetics and Heredity. That's me on page 578, standing naked beside a height chart with a black box covering my eyes. My birth certificate lists my name as Calliope Helen Stephanides. My most recent driver's license (from the Federal Republic of Germany) records my first name simply as Cal. I'm a former field hockey goalie, longstanding member of the Save-the-Manatee Foundation, rare attendant at the Greek Orthodox liturgy, and, for most of my adult life, an employee of the U.S. State Department. Like...

Please be aware that this discussion guide will contain spoilers!

- Describing his own conception, Cal writes: "The timing of the thing had to be just so in order for me to become the person I am. Delay the act by an hour and you change the gene selection" (p. 11). Is Cal’s condition a result of chance or of fate? Which of these forces governs the world as Cal sees it?

- Middlesex begins just before Cal’s birth in 1960, then moves backward in time to 1922. Cal is born at the beginning of Part 3, about halfway through the novel. Why did the author choose to structure the story in this way? How does this movement backward and forward in time reflect the larger themes of the work?

- When Tessie and Milton decide to try to influence the sex of their baby, Desdemona disapproves. "God decides what ...

- "Beyond the Book" articles

- Free books to read and review (US only)

- Find books by time period, setting & theme

- Read-alike suggestions by book and author

- Book club discussions

- and much more!

- Just $45 for 12 months or $15 for 3 months.

- More about membership!

Pulitzer Prize 2003

Media Reviews

Reader reviews.

Write your own review!

Read-Alikes

- Genres & Themes

If you liked Middlesex, try these:

The Heart's Invisible Furies

by John Boyne

Published 2018

About this book

More by this author

From the beloved New York Times bestselling author of The Boy In the Striped Pajamas , a sweeping, heartfelt saga about the course of one man's life, beginning and ending in post-war Ireland

Long Black Veil

by Jennifer Finney Boylan

For fans of The Secret History and The Poison Tree , a novel about a woman whose family and identity are threatened by the secrets of her past, from the New York Times bestselling author of She's Not There .

Books with similar themes

Become a Member

BookBrowse Book Club

Members Recommend

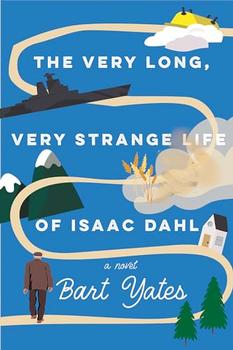

The Very Long, Very Strange Life of Isaac Dahl by Bart Yates

A saga spanning 12 significant days across nearly 100 years in the life of a single man.

.png)

Solve this clue:

It's R C A D

and be entered to win..

Win This Book

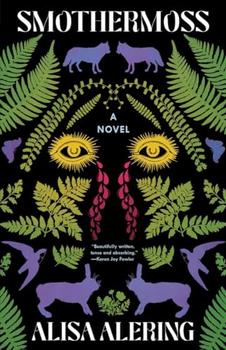

Smothermoss by Alisa Alering

A haunting, imaginative, and twisting tale of two sisters and the menacing, unexplained forces that threaten them and their rural mountain community.

Get the Book Marks Bulletin

Email address:

- Categories Fiction Fantasy Graphic Novels Historical Horror Literary Literature in Translation Mystery, Crime, & Thriller Poetry Romance Speculative Story Collections Non-Fiction Art Biography Criticism Culture Essays Film & TV Graphic Nonfiction Health History Investigative Journalism Memoir Music Nature Politics Religion Science Social Sciences Sports Technology Travel True Crime

August 5 – 9, 2024

- What separates humans from machines?

- Abraham Chang on publishing and aging

- On the history of anti-trans panic in sports

The Literary Edit

Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides Book Review

Towards the end of 2022, I looked at a list I had made last January of all the books I wanted to finish before the year was out. It was something of an ambitious list – but one that I should – and could – have finished, had I been more diligent in my reading. Alas, I wasn’t, and while I read just shy of 90 books in total, as I often lament, I wish I had been more particular in selecting the books I chose to read.

One such book I did manage to tick of the list – and one that had been on my ever-growing reading pile ever since I first read Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides when I lived in Los Angeles – was the author’s second book, and winner of the 2003 Pulitzer Prize, Middlesex. Over the years I’ve collected a handful of copies, and when I headed to Byron with a friend in November, I took it, promising I wouldn’t return to Bondi with a single page unread. And so read it, I did, over one very, very wet week in Byron, during which the sky remained low and looming and grey, and I spent much of the week curled up on the sofa, candles flickering, tea in hand, as I lost myself in Eugenides much-loved modern classic.

Middlesex Book Review

A tale that’s about as different from The Virgin Suicides as it could possibly get, Middlesex is a story of epic proportions that tells the tale of Calliope – a character who was born intersex and raised as a girl – but who, during their adolescence becomes Cal.

It spans almost a century and traces the Stephanides family from battle-torn Greece and Turkey in the 1920s, across an Atlantic voyage, from the street corners of Detroit, through World War II, and out to the suburban haven of Grosse Pointe, Michigan, and offers its readers a rich and complex family drama, straddling multiple generations and exploring everything from incest to immigration to family secrets and what life was like in twentieth-century America.

And while the themes of the novel are wide and varied, at its heart Middlesex is a book about people, and what it is that makes us human. It looks at the idea that we are all years in the making long before we’re born, and ponders the notion that our stories begin way before us in faraway lands, and in communities and countries about which we may never know.

With an endearing and smart narrator, and a cast of unforgettable characters, Middlesex is a story about the trials and tribulations of both childhood and adolescence, and a poignant portrayal of Calliope “Cal” Stephanides, as we discover the humanity of a character one might otherwise find alienated elsewhere.

Middlesex summary

Middlesex tells the breathtaking story of Calliope Stephanides, and three generations of the Greek-American Stephanides family, who travel from a tiny village overlooking Mount Olympus in Asia Minor to Prohibition-era Detroit, witnessing its glory days as the Motor City and the race riots of 1967 before moving out to the tree-lined streets of suburban Grosse Pointe, Michigan. To understand why Calliope is not like other girls, she has to uncover a guilty family secret, and the astonishing genetic history that turns Callie into Cal, one of the most audacious and wondrous narrators in contemporary fiction. Lyrical and thrilling, Middlesex is an exhilarating reinvention of the American epic.

Buy Middlesex from Bookshop.org , Book Depository or Waterstones .

Further reading

I loved Jeffrey Eugenides short story, Bronze , published in the New Yorker.

Jeffrey Eugenides author bio

Jeffrey Kent Eugenides is an American Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist and short story writer of Greek and Irish extraction.

Eugenides was born in Detroit, Michigan, of Greek and Irish descent. He attended Grosse Pointe’s private University Liggett School. He took his undergraduate degree at Brown University, graduating in 1983. He later earned an M.A. in Creative Writing from Stanford University.

In 1986 he received the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Nicholl Fellowship for his story “Here Comes Winston, Full of the Holy Spirit”. His 1993 novel, The Virgin Suicides, gained mainstream interest with the 1999 film adaptation directed by Sofia Coppola. The novel was reissued in 2009.

Other Jeffrey Eugenides books

His other novels include The Virgin Suicides and The Marriage Plot.

Love this post? Click here to subscribe.

This post contains affiliate links, which means I receive a small commission, at no extra cost to you, if you make a purchase using this link.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

- Bibliotherapy Sessions

- In the press

- Disclaimer + privacy policy

- Work with me

- The BBC Big Read

- The 1001 Books to Read Before You Die

- Desert Island Books

- Books by Destination

- Beautiful Bookstores

- Literary Travel

- Stylish Stays

- The Journal

- The Bondi Literary Salon

307 E Lake St. Petoskey, MI 49770 | 231-347-1180 | H ours

Middlesex: A Novel (Paperback)

Staff Reviews

For those who can appreciate good literature, this is a tenderly written story, spanning three generations of a Greek American family. I especially enjoyed the rich storytelling about the history of Detroit.

- Description

- About the Author

- Reviews & Media

Middlesex is the winner of the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. A dazzling triumph from the bestselling author of The Virgin Suicides --the astonishing tale of a gene that passes down through three generations of a Greek-American family and flowers in the body of a teenage girl. "I was born twice: first, as a baby girl, on a remarkably smogless Detroit day of January 1960; and then again, as a teenage boy, in an emergency room near Petoskey, Michigan, in August of l974. . . My birth certificate lists my name as Calliope Helen Stephanides. My most recent driver's license...records my first name simply as Cal." So begins the breathtaking story of Calliope Stephanides and three generations of the Greek-American Stephanides family who travel from a tiny village overlooking Mount Olympus in Asia Minor to Prohibition-era Detroit, witnessing its glory days as the Motor City, and the race riots of l967, before they move out to the tree-lined streets of suburban Grosse Pointe, Michigan. To understand why Calliope is not like other girls, she has to uncover a guilty family secret and the astonishing genetic history that turns Callie into Cal, one of the most audacious and wondrous narrators in contemporary fiction. Lyrical and thrilling, Jeffrey Eugenides's Middlesex is an exhilarating reinvention of the American epic.

- Fiction / Literary

- Fiction / World Literature / American / 21st Century

- Paperback (Spanish) (July 25th, 2012): $19.95

- Paperback (French) (June 2nd, 2004): $28.95

- Paperback (September 1st, 2003): $15.00

“Part Tristram Shandy, part Ishmael, part Holden Caulfield, Cal is a wonderfully engaging narrator. . . A deeply affecting portrait of one family's tumultuous engagement with the American twentieth century.” — The New York Times “Expansive and radiantly generous. . . Deliriously American.” — The New York Times Book Review (cover review) “A towering achievement. . . . [Eugenides] has emerged as the great American writer that many of us suspected him of being.” — Los Angeles Times Book Review (cover review) “A big, cheeky, splendid novel. . . it goes places few narrators would dare to tread. . . lyrical and fine.” — The Boston Globe “An epic. . . This feast of a novel is thrilling in the scope of its imagination and surprising in its tenderness.” — People “Unprecedented, astounding. . . . The most reliably American story there is: A son of immigrants finally finds love after growing up feeling like a freak.” — San Francisco Chronicle Book Review “Middlesex is about a hermaphrodite in the way that Thomas Wolfe's Look Homeward, Angel is about a teenage boy. . . A novel of chance, family, sex, surgery, and America, it contains multitudes.” — Men's Journal “Wildly imaginative. . . frequently hilarious and touching.” — USA Today

Please beware of fraud schemes by third parties falsely using our company and imprint names to solicit money and personal information. Learn More .

Book details

Author: Jeffrey Eugenides

Award Winner

- National Books Critics Circle Awards - Nominee

- Ambassador Book Award - Winner

- Audie Award Winner

- Great Lakes Book Award - Winner

- Pulitzer Prize Winner

- Lambda Literary Award - Nominee

- National Book Critics Circle Award - Nominee

- National Book Critics Circle Awards - Nominee

- International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award - Nominee

- (Selected for) Oprah's Book Club

- Audible.com 100 Audible Essentials

- ALA Stonewall Book Award - Honor Book

MIDDLESEX (chapter 1) THE SILVER SPOON I was born twice: first, as a baby girl, on a remarkably smogless Detroit day in January of 1960; and then again, as a teenage boy, in an emergency room near Petoskey, Michigan, in August of 1974. Specialized readers may have come across me in Dr. Peter Luce's study, "Gender Identity in 5-Alpha-Reductase Pseudohermaphrodites," published in the Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology in 1975. Or maybe you've seen my photograph in chapter sixteen of the now sadly outdated Genetics and Heredity . That's me on page 578, standing naked beside a height chart with a black box covering my eyes. My birth certificate lists my name as Calliope Helen Stephanides. My most recent driver's license (from the Federal Republic of Germany) records my first name simply as Cal. I'm a former field hockey goalie, long-standing member of the Save-the-Manatee Foundation, rare attendant at the Greek Orthodox liturgy, and, for most of my adult life, an employee of the U.S. State Department. Like Tiresias, I was first one thing and then the other. I've been ridiculed by classmates, guinea-pigged by doctors, palpated by specialists, and researched by the March of Dimes. A redheaded girl from Grosse Pointe fell in love with me, not knowing what I was. (Her brother liked me, too.) An army tank led me into urban battle once; a swimming pool turned me into myth; I've left my body in order to occupy others--and all this happened before I turned sixteen. But now, at the age of forty-one, I feel another birth coming on. After decades of neglect, I find myself thinking about departed great-aunts and -uncles, long-lost grandfathers, unknown fifth cousins, or, in the case of an inbred family like mine, all those things in one. And so before it's too late I want to get it down for good: this roller-coaster ride of a single gene through time. Sing now, O Muse, of the recessive mutation on my fifth chromosome! Sing how it bloomed two and a half centuries ago on the slopes of Mount Olympus, while the goats bleated and the olives dropped. Sing how it passed down through nine generations, gathering invisibly within the polluted pool of the Stephanides family. And sing how Providence, in the guise of a massacre, sent the gene flying again; how it blew like a seed across the sea to America, where it drifted through our industrial rains until it fell to earth in the fertile soil of my mother's own midwestern womb. Sorry if I get a little Homeric at times. That's genetic, too. Three months before I was born, in the aftermath of one of our elaborate Sunday dinners, my grandmother Desdemona Stephanides ordered my brother to get her silkworm box. Chapter Eleven had been heading toward the kitchen for a second helping of rice pudding when she blocked his way. At fifty-seven, with her short, squat figure and intimidating hairnet, my grandmother was perfectly designed for blocking people's paths. Behind her in the kitchen, the day's large female contingent had congregated, laughing and whispering. Intrigued, Chapter Eleven leaned sideways to see what was going on, but Desdemona reached out and firmly pinched his cheek. Having regained his attention, she sketched a rectangle in the air and pointed at the ceiling. Then, through her ill-fitting dentures, she said, "Go for yia yia , dolly mou ." Chapter Eleven knew what to do. He ran across the hall into the living room. On all fours he scrambled up the formal staircase to the second floor. He raced past the bedrooms along the upstairs corridor. At the far end was a nearly invisible door, wallpapered over like the entrance to a secret passageway. Chapter Eleven located the tiny doorknob level with his head and, using all his strength, pulled it open. Another set of stairs lay behind it. For a long moment my brother stared hesitantly into the darkness above, before climbing, very slowly now, up to the attic where my grandparents lived. In sneakers he passed beneath the twelve damply newspapered birdcages suspended from the rafters. With a brave face he immersed himself in the sour odor of the parakeets, and in my grandparents' own particular aroma, a mixture of mothballs and hashish. He negotiated his way past my grandfather's book-piled desk and his collection of rebetika records. Finally, bumping into the leather ottoman and the circular coffee table made of brass, he found my grandparents' bed and, under it, the silkworm box. Carved from olivewood, a little bigger than a shoe box, it had a tin lid perforated by tiny airholes and inset with the icon of an unrecognizable saint. The saint's face had been rubbed off, but the fingers of his right hand were raised to bless a short, purple, terrifically self-confident-looking mulberry tree. After gazing awhile at this vivid botanical presence, Chapter Eleven pulled the box from under the bed and opened it. Inside were the two wedding crowns made from rope and, coiled like snakes, the two long braids of hair, each tied with a crumbling black ribbon. He poked one of the braids with his index finger. Just then a parakeet squawked, making my brother jump, and he closed the box, tucked it under his arm, and carried it downstairs to Desdemona. She was still waiting in the doorway. Taking the silkworm box out of his hands, she turned back into the kitchen. At this point Chapter Eleven was granted a view of the room, where all the women now fell silent. They moved aside to let Desdemona pass and there, in the middle of the linoleum, was my mother. Tessie Stephanides was leaning back in a kitchen chair, pinned beneath the immense, drum-tight globe of her pregnant belly. She had a happy, helpless expression on her face, which was flushed and hot. Desdemona set the silkworm box on the kitchen table and opened the lid. She reached under the wedding crowns and the hair braids to come up with something Chapter Eleven hadn't seen: a silver spoon. She tied a piece of string to the spoon's handle. Then, stooping forward, she dangled the spoon over my mother's swollen belly. And, by extension, over me. Up until now Desdemona had had a perfect record: twenty-three correct guesses. She'd known that Tessie was going to be Tessie. She'd predicted the sex of my brother and of all the babies of her friends at church. The only children whose genders she hadn't divined were her own, because it was bad luck for a mother to plumb the mysteries of her own womb. Fearlessly, however, she plumbed my mother's. After some initial hesitation, the spoon swung north to south, which meant that I was going to be a boy. Splay-legged in the chair, my mother tried to smile. She didn't want a boy. She had one already. In fact, she was so certain I was going to be a girl that she'd picked out only one name for me: Calliope. But when my grandmother shouted in Greek, "A boy!" the cry went around the room, and out into the hall, and across the hall into the living room where the men were arguing politics. And my mother, hearing it repeated so many times, began to believe it might be true. As soon as the cry reached my father, however, he marched into the kitchen to tell his mother that, this time at least, her spoon was wrong. "And how you know so much?" Desdemona asked him. To which he replied what many Americans of his generation would have: "It's science, Ma." Ever since they had decided to have another child--the diner was doing well and Chapter Eleven was long out of diapers--Milton and Tessie had been in agreement that they wanted a daughter. Chapter Eleven had just turned five years old. He'd recently found a dead bird in the yard, bringing it into the house to show his mother. He liked shooting things, hammering things, smashing things, and wrestling with his father. In such a masculine household, Tessie had begun to feel like the odd woman out and saw herself in ten years' time imprisoned in a world of hubcaps and hernias. My mother pictured a daughter as a counterinsurgent: a fellow lover of lapdogs, a seconder of proposals to attend the Ice Capades. In the spring of 1959, when discussions of my fertilization got under way, my mother couldn't foresee that women would soon be burning their brassieres by the thousand. Hers were padded, stiff, fire-retardant. As much as Tessie loved her son, she knew there were certain things she'd be able to share only with a daughter. On his morning drive to work, my father had been seeing visions of an irresistibly sweet, dark-eyed little girl. She sat on the seat beside him--mostly during stoplights--directing questions at his patient, all-knowing ear. "What do you call that thing, Daddy?" "That? That's the Cadillac seal." "What's the Cadillac seal?" "Well, a long time ago, there was a French explorer named Cadillac, and he was the one who discovered Detroit. And that seal was his family seal, from France." "What's France?" "France is a country in Europe." "What's Europe?" "It's a continent, which is like a great big piece of land, way, way bigger than a country. But Cadillacs don't come from Europe anymore, kukla . They come from right here in the good old U.S.A." The light turned green and he drove on. But my prototype lingered. She was there at the next light and the next. So pleasant was her company that my father, a man loaded with initiative, decided to see what he could do to turn his vision into reality. Thus: for some time now, in the living room where the men discussed politics, they had also been discussing the velocity of sperm. Peter Tatakis, "Uncle Pete," as we called him, was a leading member of the debating society that formed every week on our black love seats. A lifelong bachelor, he had no family in America and so had become attached to ours. Every Sunday he arrived in his wine-dark Buick, a tall, prune-faced, sad-seeming man with an incongruously vital head of wavy hair. He was not interested in children. A proponent of the Great Books series--which he had read twice--Uncle Pete was engaged with serious thought and Italian opera. He had a passion, in history, for Edward Gibbon, and, in literature, for the journals of Madame de Staël. He liked to quote that witty lady's opinion on the German language, which held that German wasn't good for conversation because you had to wait to the end of the sentence for the verb, and so couldn't interrupt. Uncle Pete had wanted to become a doctor, but the "catastrophe" had ended that dream. In the United States, he'd put himself through two years of chiropractic school, and now ran a small office in Birmingham with a human skeleton he was still paying for in installments. In those days, chiropractors had a somewhat dubious reputation. People didn't come to Uncle Pete to free up their kundalini. He cracked necks, straightened spines, and made custom arch supports out of foam rubber. Still, he was the closest thing to a doctor we had in the house on those Sunday afternoons. As a young man he'd had half his stomach surgically removed, and now after dinner always drank a Pepsi-Cola to help digest his meal. The soft drink had been named for the digestive enzyme pepsin, he sagely told us, and so was suited to the task. It was this kind of knowledge that led my father to trust what Uncle Pete said when it came to the reproductive timetable. His head on a throw pillow, his shoes off, Madama Butterfly softly playing on my parents' stereo, Uncle Pete explained that, under the microscope, sperm carrying male chromosomes had been observed to swim faster than those carrying female chromosomes. This assertion generated immediate merriment among the restaurant owners and fur finishers assembled in our living room. My father, however, adopted the pose of his favorite piece of sculpture, The Thinker , a miniature of which sat across the room on the telephone table. Though the topic had been brought up in the open-forum atmosphere of those postprandial Sundays, it was clear that, notwithstanding the impersonal tone of the discussion, the sperm they were talking about was my father's. Uncle Pete made it clear: to have a girl baby, a couple should "have sexual congress twenty-four hours prior to ovulation." That way, the swift male sperm would rush in and die off. The female sperm, sluggish but more reliable, would arrive just as the egg dropped. My father had trouble persuading my mother to go along with the scheme. Tessie Zizmo had been a virgin when she married Milton Stephanides at the age of twenty-two. Their engagement, which coincided with the Second World War, had been a chaste affair. My mother was proud of the way she'd managed to simultaneously kindle and snuff my father's flame, keeping him at a low burn for the duration of a global cataclysm. This hadn't been all that difficult, however, since she was in Detroit and Milton was in Annapolis at the U.S. Naval Academy. For more than a year Tessie lit candles at the Greek church for her fiancé, while Milton gazed at her photographs pinned over his bunk. He liked to pose Tessie in the manner of the movie magazines, standing sideways, one high heel raised on a step, an expanse of black stocking visible. My mother looks surprisingly pliable in those old snapshots, as though she liked nothing better than to have her man in uniform arrange her against the porches and lampposts of their humble neighborhood. She didn't surrender until after Japan had. Then, from their wedding night onward (according to what my brother told my covered ears), my parents made love regularly and enjoyably. When it came to having children, however, my mother had her own ideas. It was her belief that an embryo could sense the amount of love with which it had been created. For this reason, my father's suggestion didn't sit well with her. "What do you think this is, Milt, the Olympics?" "We were just speaking theoretically," said my father. "What does Uncle Pete know about having babies?" "He read this particular article in Scientific American ," Milton said. And to bolster his case: "He's a subscriber." "Listen, if my back went out, I'd go to Uncle Pete. If I had flat feet like you do, I'd go. But that's it." "This has all been verified. Under the microscope. The male sperms are faster." "I bet they're stupider, too." "Go on. Malign the male sperms all you want. Feel free. We don't want a male sperm. What we want is a good old, slow, reliable female sperm." "Even if it's true, it's still ridiculous. I can't just do it like clockwork, Milt." "It'll be harder on me than you." "I don't want to hear it." "I thought you wanted a daughter." "I do." "Well," said my father, "this is how we can get one." Tessie laughed the suggestion off. But behind her sarcasm was a serious moral reservation. To tamper with something as mysterious and miraculous as the birth of a child was an act of hubris. In the first place, Tessie didn't believe you could do it. Even if you could, she didn't believe you should try. Of course, a narrator in my position (prefetal at the time) can't be entirely sure about any of this. I can only explain the scientific mania that overtook my father during that spring of '59 as a symptom of the belief in progress that was infecting everyone back then. Remember, Sputnik had been launched only two years earlier. Polio, which had kept my parents quarantined indoors during the summers of their childhood, had been conquered by the Salk vaccine. People had no idea that viruses were cleverer than human beings, and thought they'd soon be a thing of the past. In that optimistic, postwar America, which I caught the tail end of, everybody was the master of his own destiny, so it only followed that my father would try to be the master of his. A few days after he had broached his plan to Tessie, Milton came home one evening with a present. It was a jewelry box tied with a ribbon. "What's this for?" Tessie asked suspiciously. "What do you mean, what is it for?" "It's not my birthday. It's not our anniversary. So why are you giving me a present?" "Do I have to have a reason to give you a present? Go on. Open it." Tessie crumpled up one corner of her mouth, unconvinced. But it was difficult to hold a jewelry box in your hand without opening it. So finally she slipped off the ribbon and snapped the box open. Inside, on black velvet, was a thermometer. "A thermometer," said my mother. "That's not just any thermometer," said Milton. "I had to go to three different pharmacies to find one of these." "A luxury model, huh?" "That's right," said Milton. "That's what you call a basal thermometer. It reads the temperature down to a tenth of a degree ." He raised his eyebrows. "Normal thermometers only read every two tenths. This one does it every tenth. Try it out. Put it in your mouth." "I don't have a fever," said Tessie. "This isn't about a fever. You use it to find out what your base temperature is. It's more accurate and precise than a regular fever-type thermometer." "Next time bring me a necklace." But Milton persisted: "Your body temperature's changing all the time, Tess. You may not notice, but it is. You're in constant flux, temperature-wise. Say, for instance"--a little cough--"you happen to be ovulating. Then your temperature goes up. Six tenths of a degree, in most case scenarios. Now," my father went on, gaining steam, not noticing that his wife was frowning, "if we were to implement the system we talked about the other day--just for instance, say--what you'd do is, first , establish your base temperature . It might not be ninety-eight point six. Everybody's a little different. That's another thing I learned from Uncle Pete. Anyway, once you established your base temperature, then you'd look for that six-tenths-degree rise. And that's when, if we were to go through with this, that's when we'd know to, you know, mix the cocktail." My mother said nothing. She only put the thermometer into the box, closed it, and handed it back to her husband. "Okay," he said. "Fine. Suit yourself. We may get another boy. Number two. If that's the way you want it, that's the way it'll be." "I'm not so sure we're going to have anything at the moment," replied my mother. Meanwhile, in the greenroom to the world, I waited. Not even a gleam in my father's eye yet (he was staring gloomily at the thermometer case in his lap). Now my mother gets up from the so-called love seat. She heads for the stairway, holding a hand to her forehead, and the likelihood of my ever coming to be seems more and more remote. Now my father gets up to make his rounds, turning out lights, locking doors. As he climbs the stairway, there's hope for me again. The timing of the thing had to be just so in order for me to become the person I am. Delay the act by an hour and you change the gene selection. My conception was still weeks away, but already my parents had begun their slow collision into each other. In our upstairs hallway, the Acropolis night-light is burning, a gift from Jackie Halas, who owns a souvenir shop. My mother is at her vanity when my father enters the bedroom. With two fingers she rubs Noxzema into her face, wiping it off with a tissue. My father had only to say an affectionate word and she would have forgiven him. Not me but somebody like me might have been made that night. An infinite number of possible selves crowded the threshold, me among them but with no guaranteed ticket, the hours moving slowly, the planets in the heavens circling at their usual pace, weather coming into it, too, because my mother was afraid of thunderstorms and would have cuddled against my father had it rained that night. But, no, clear skies held out, as did my parents' stubbornness. The bedroom light went out. They stayed on their own sides of the bed. At last, from my mother, "Night." And from my father, "See you in the morning." The moments that led up to me fell into place as though decreed. Which, I guess, is why I think about them so much. The following Sunday, my mother took Desdemona and my brother to church. My father never went along, having become an apostate at the age of eight over the exorbitant price of votive candles. Likewise, my grandfather preferred to spend his mornings working on a modern Greek translation of the "restored" poems of Sappho. For the next seven years, despite repeated strokes, my grandfather worked at a small desk, piecing together the legendary fragments into a larger mosaic, adding a stanza here, a coda there, soldering an anapest or an iamb. In the evenings he played his bordello music and smoked a hookah pipe. In 1959, Assumption Greek Orthodox Church was located on Charlevoix. It was there that I would be baptized less than a year later and would be brought up in the Orthodox faith. Assumption, with its revolving chief priests, each sent to us via the Patriarchate in Constantinople, each arriving in the full beard of his authority, the embroidered vestments of his sanctity, but each wearying after a time--six months was the rule--because of the squabbling of the congregation, the personal attacks on the way he sang, the constant need to shush the parishioners who treated the church like the bleachers at Tiger Stadium, and, finally, the effort of delivering a sermon each week twice, first in Greek and then again in English. Assumption, with its spirited coffee hours, its bad foundation and roof leaks, its strenuous ethnic festivals, its catechism classes where our heritage was briefly kept alive in us before being allowed to die in the great diaspora. Tessie and company advanced down the central aisle, past the sand-filled trays of votive candles. Above, as big as a float in the Macy's Thanksgiving Day Parade, was the Christ Pantocrator. He curved across the dome like space itself. Unlike the suffering, earthbound Christs depicted at eye level on the church walls, our Christ Pantocrator was clearly transcendent, all-powerful, heaven-bestriding. He was reaching down to the apostles above the altar to present the four rolled-up sheepskins of the Gospels. And my mother, who tried all her life to believe in God without ever quite succeeding, looked up at him for guidance. The Christ Pantocrator's eyes flickered in the dim light. They seemed to suck Tessie upward. Through the swirling incense, the Savior's eyes glowed like televisions flashing scenes of recent events . . . First there was Desdemona the week before, giving advice to her daughter-in-law. "Why you want more children, Tessie?" she had asked with studied nonchalance. Bending to look in the oven, hiding the alarm on her face (an alarm that would go unexplained for another sixteen years), Desdemona waved the idea away. "More children, more trouble . . ." Next there was Dr. Philobosian, our elderly family physician. With ancient diplomas behind him, the old doctor gave his verdict. "Nonsense. Male sperm swim faster? Listen. The first person who saw sperm under a microscope was Leeuwenhoek. Do you know what they looked like to him? Like worms . . ." And then Desdemona was back, taking a different angle: "God decides what baby is. Not you . . ." These scenes ran through my mother's mind during the interminable Sunday service. The congregation stood and sat. In the front pew, my cousins, Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, and Cleopatra, fidgeted. Father Mike emerged from behind the icon screen and swung his censer. My mother tried to pray, but it was no use. She barely survived until coffee hour. From the tender age of twelve, my mother had been unable to start her day without the aid of at least two cups of immoderately strong, tar-black, unsweetened coffee, a taste for which she had picked up from the tugboat captains and zooty bachelors who filled the boardinghouse where she had grown up. As a high school girl, standing five foot one inch tall, she had sat next to auto workers at the corner diner, having coffee before her first class. While they scanned the racing forms, Tessie finished her civics homework. Now, in the church basement, she told Chapter Eleven to run off and play with the other children while she got a cup of coffee to restore herself. She was on her second cup when a soft, womanly voice sighed in her ear. "Good morning, Tessie." It was her brother-in-law, Father Michael Antoniou. "Hi, Father Mike. Beautiful service today," Tessie said, and immediately regretted it. Father Mike was the assistant priest at Assumption. When the last priest had left, harangued back to Athens after a mere three months, the family had hoped that Father Mike might be promoted. But in the end another new, foreign-born priest, Father Gregorios, had been given the post. Aunt Zo, who never missed a chance to lament her marriage, had said at dinner in her comedienne's voice, "My husband. Always the bridesmaid and never the bride." By complimenting the service, Tessie hadn't intended to compliment Father Greg. The situation was made still more delicate by the fact that, years ago, Tessie and Michael Antoniou had been engaged to be married. Now she was married to Milton and Father Mike was married to Milton's sister. Tessie had come down to clear her head and have her coffee and already the day was getting out of hand. Father Mike didn't appear to notice the slight, however. He stood smiling, his eyes gentle above the roaring waterfall of his beard. A sweet-natured man, Father Mike was popular with church widows. They liked to crowd around him, offering him cookies and bathing in his beatific essence. Part of this essence came from Father Mike's perfect contentment at being only five foot four. His shortness had a charitable aspect to it, as though he had given away his height. He seemed to have forgiven Tessie for breaking off their engagement years ago, but it was always there in the air between them, like the talcum powder that sometimes puffed out of his clerical collar. Smiling, carefully holding his coffee cup and saucer, Father Mike asked, "So, Tessie, how are things at home?" My mother knew, of course, that as a weekly Sunday guest at our house, Father Mike was fully informed about the thermometer scheme. Looking in his eyes, she thought she detected a glint of amusement. "You're coming over to the house today," she said carelessly. "You can see for yourself." "I'm looking forward to it," said Father Mike. "We always have such interesting discussions at your house." Tessie examined Father Mike's eyes again but now they seemed full of genuine warmth. And then something happened to take her attention away from Father Mike completely. Across the room, Chapter Eleven had stood on a chair to reach the tap of the coffee urn. He was trying to fill a coffee cup, but once he got the tap open he couldn't get it closed. Scalding coffee poured out across the table. The hot liquid splattered a girl who was standing nearby. The girl jumped back. Her mouth opened, but no sound came out. With great speed my mother ran across the room and whisked the girl into the ladies' room. No one remembers the girl's name. She didn't belong to any of the regular parishioners. She wasn't even Greek. She appeared at church that one day and never again, and seems to have existed for the sole purpose of changing my mother's mind. In the bathroom the girl held her steaming shirt away from her body while Tessie brought damp towels. "Are you okay, honey? Did you get burned?" "He's very clumsy, that boy," the girl said. "He can be. He gets into everything." "Boys can be very obstreperous." Tessie smiled. "You have quite a vocabulary." At this compliment the girl broke into a big smile. " 'Obstreperous' is my favorite word. My brother is very obstreperous. Last month my favorite word was 'turgid.' But you can't use 'turgid' that much. Not that many things are turgid, when you think about it." "You're right about that," said Tessie, laughing. "But obstreperous is all over the place." "I couldn't agree with you more," said the girl. Two weeks later. Easter Sunday, 1959. Our religion's adherence to the Julian calendar has once again left us out of sync with the neighborhood. Two Sundays ago, my brother watched as the other kids on the block hunted multicolored eggs in nearby bushes. He saw his friends eating the heads off chocolate bunnies and tossing handfuls of jelly beans into cavity-rich mouths. (Standing at the window, my brother wanted more than anything to believe in an American God who got resurrected on the right day.) Only yesterday was Chapter Eleven finally allowed to dye his own eggs, and then only in one color: red. All over the house red eggs gleam in lengthening, solstice rays. Red eggs fill bowls on the dining room table. They hang from string pouches over doorways. They crowd the mantel and are baked into loaves of cruciform tsoureki . But now it is late afternoon; dinner is over. And my brother is smiling. Because now comes the one part of Greek Easter he prefers to egg hunts and jelly beans: the egg-cracking game. Everyone gathers around the dining table. Biting his lip, Chapter Eleven selects an egg from the bowl, studies it, returns it. He selects another. "This looks like a good one," Milton says, choosing his own egg. "Built like a Brinks truck." Milton holds his egg up. Chapter Eleven prepares to attack. When suddenly my mother taps my father on the back. "Just a minute, Tessie. We're cracking eggs here." She taps him harder. "What?" "My temperature." She pauses. "It's up six tenths." She has been using the thermometer. This is the first my father has heard of it. "Now?" my father whispers. "Jesus, Tessie, are you sure?" "No, I'm not sure. You told me to watch for any rise in my temperature and I'm telling you I'm up six tenths of a degree." And, lowering her voice, "Plus it's been thirteen days since my last you know what." "Come on, Dad," Chapter Eleven pleads. "Time out," Milton says. He puts his egg in the ashtray. "That's my egg. Nobody touch it until I come back." Upstairs, in the master bedroom, my parents accomplish the act. A child's natural decorum makes me refrain from imagining the scene in much detail. Only this: when they're done, as if topping off the tank, my father says, "That should do it." It turns out he's right. In May, Tessie learns she's pregnant, and the waiting begins. By six weeks, I have eyes and ears. By seven, nostrils, even lips. My genitals begin to form. Fetal hormones, taking chromosomal cues, inhibit Müllerian structures, promote Wolffian ducts. My twenty-three paired chromosomes have linked up and crossed over, spinning their roulette wheel, as my papou puts his hand on my mother's belly and says, "Lucky two!" Arrayed in their regiments, my genes carry out their orders. All except two, a pair of miscreants--or revolutionaries, depending on your view--hiding out on chromosome number 5. Together, they siphon off an enzyme, which stops the production of a certain hormone, which complicates my life. In the living room, the men have stopped talking about politics and instead lay bets on whether Milt's new kid will be a boy or a girl. My father is confident. Twenty-four hours after the deed, my mother's body temperature rose another two tenths, confirming ovulation. By then the male sperm had given up, exhausted. The female sperm, like tortoises, won the race. (At which point Tessie handed Milton the thermometer and told him she never wanted to see it again.) All this led up to the day Desdemona dangled a utensil over my mother's belly. The sonogram didn't exist at the time; the spoon was the next best thing. Desdemona crouched. The kitchen grew silent. The other women bit their lower lips, watching, waiting. For the first minute, the spoon didn't move at all. Desdemona's hand shook and, after long seconds had passed, Aunt Lina steadied it. The spoon twirled; I kicked; my mother cried out. And then, slowly, moved by a wind no one felt, in that unearthly Ouija-board way, the silver spoon began to move, to swing, at first in a small circle but each orbit growing gradually more elliptical until the path flattened into a straight line pointing from oven to banquette. North to south, in other words. Desdemona cried, "Koros!" And the room erupted with shouts of "Koros, koros." That night, my father said, "Twenty-three in a row means she's bound for a fall. This time, she's wrong. Trust me." "I don't mind if it's a boy," my mother said. "I really don't. As long as it's healthy, ten fingers, ten toes." "What's this 'it.' That's my daughter you're talking about." I was born a week after New Year's, on January 8, 1960. In the waiting room, supplied only with pink-ribboned cigars, my father cried out, "Bingo!" I was a girl. Nineteen inches long. Seven pounds four ounces. That same January 8, my grandfather suffered the first of his thirteen strokes. Awakened by my parents rushing off to the hospital, he'd gotten out of bed and gone downstairs to make himself a cup of coffee. An hour later, Desdemona found him lying on the kitchen floor. Though his mental faculties remained intact, that morning, as I let out my first cry at Women's Hospital, my papou lost the ability to speak. According to Desdemona, my grandfather collapsed right after overturning his coffee cup to read his fortune in the grounds. When he heard the news of my sex, Uncle Pete refused to accept any congratulations. There was no magic involved. "Besides," he joked, "Milt did all the work." Desdemona became grim. Her American-born son had been proven right and, with this fresh defeat, the old country, in which she still tried to live despite its being four thousand miles and thirty-eight years away, receded one more notch. My arrival marked the end of her baby-guessing and the start of her husband's long decline. Though the silkworm box reappeared now and then, the spoon was no longer among its treasures. I was extracted, spanked, and hosed off, in that order. They wrapped me in a blanket and put me on display among six other infants, four boys, two girls, all of them, unlike me, correctly tagged. This can't be true but I remember it: sparks slowly filling a dark screen. Someone had switched on my eyes. MIDDLESEX Copyright © 2002 by Jeffrey Eugenides

Available in Digital Audio!

Buy This Book From:

About this book.

Middlesex is the winner of the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. A dazzling triumph from the bestselling author of The Virgin Suicides --the astonishing...

Book Details

Middlesex is the winner of the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. A dazzling triumph from the bestselling author of The Virgin Suicides --the astonishing tale of a gene that passes down through three generations of a Greek-American family and flowers in the body of a teenage girl. "I was born twice: first, as a baby girl, on a remarkably smogless Detroit day of January 1960; and then again, as a teenage boy, in an emergency room near Petoskey, Michigan, in August of l974. . . My birth certificate lists my name as Calliope Helen Stephanides. My most recent driver's license...records my first name simply as Cal." So begins the breathtaking story of Calliope Stephanides and three generations of the Greek-American Stephanides family who travel from a tiny village overlooking Mount Olympus in Asia Minor to Prohibition-era Detroit, witnessing its glory days as the Motor City, and the race riots of l967, before they move out to the tree-lined streets of suburban Grosse Pointe, Michigan. To understand why Calliope is not like other girls, she has to uncover a guilty family secret and the astonishing genetic history that turns Callie into Cal, one of the most audacious and wondrous narrators in contemporary fiction. Lyrical and thrilling, Jeffrey Eugenides's Middlesex is an exhilarating reinvention of the American epic.

Imprint Publisher

9780312427733

Reading Guide

Reading Guides for Middlesex

Get the Guide

Reading Group Guide

In the news.

“Part Tristram Shandy, part Ishmael, part Holden Caulfield, Cal is a wonderfully engaging narrator. . . A deeply affecting portrait of one family's tumultuous engagement with the American twentieth century.” — The New York Times “Expansive and radiantly generous. . . Deliriously American.” — The New York Times Book Review (cover review) “A towering achievement. . . . [Eugenides] has emerged as the great American writer that many of us suspected him of being.” — Los Angeles Times Book Review (cover review) “A big, cheeky, splendid novel. . . it goes places few narrators would dare to tread. . . lyrical and fine.” — The Boston Globe “An epic. . . This feast of a novel is thrilling in the scope of its imagination and surprising in its tenderness.” — People “Unprecedented, astounding. . . . The most reliably American story there is: A son of immigrants finally finds love after growing up feeling like a freak.” — San Francisco Chronicle Book Review “Middlesex is about a hermaphrodite in the way that Thomas Wolfe's Look Homeward, Angel is about a teenage boy. . . A novel of chance, family, sex, surgery, and America, it contains multitudes.” — Men's Journal “Wildly imaginative. . . frequently hilarious and touching.” — USA Today

About the Creators

The Book Report Network

- Bookreporter

- ReadingGroupGuides

- AuthorsOnTheWeb

Sign up for our newsletters!

Find a Guide

For book groups, what's your book group reading this month, favorite monthly lists & picks, most requested guides of 2023, when no discussion guide available, starting a reading group, running a book group, choosing what to read, tips for book clubs, books about reading groups, coming soon, new in paperback, write to us, frequently asked questions.

- Request a Guide

Advertise with Us

Add your guide, you are here:.

Cal Stephanides, the amiable narrator of MIDDLESEX, Jeffrey Eugenides' big, beguiling treat of a second novel, is born with externally deceptive genitalia. He's raised as a girl until a heart-wrenching psychological identity shift at the hormone-drenched age of 15. This is potentially trendy talk-show-topic material, but rather than setting his sights on the torment of gender confusion, Eugenides uses Cal's double-visioned life experience as an opportunity to display a generous, good-humored empathy toward all of his novel's characters, male and female. By dint of his wide-angled perspective, Cal serves readers not as a lens on the hermaphroditic, but as a prism of the humane.

Eugenides grounds Cal's life story in the context of the sprawling Stephanides family history, a Greek-American immigrant saga that brings Cal's paternal grandparents to urban Detroit in the wake of the burning of Smyrna by the Turks in 1922 and leads all the way to the present day. Readers meet four generations of Cal's consistently funny family; there are entrepreneurs, charlatans, housewives, hippies, homosexuals, and religious leaders, all linked by matrimony and genetics and love. There are births, courtships, weddings, scandals, and secrets.

While MIDDLESEX is marked as very much a 2002-model novel by its main character's peculiar duality and some highly self-conscious storytelling techniques (a Citizen Kane style summary of the whole book in its opening passage, commentaries made directly to the reader, an audacious --- but successful --- blend of first-person and omniscient narration), many of its charms are decidedly old-fashioned. MIDDLESEX is a cleverly post-modernized successor to the likes of Howard Fast's THE IMMIGRANTS series, engrossing multi-generational bestsellers that were popular in the Nixon era, when Cal Stephanides and Jeffrey Eugenides were growing up.

Even the most eccentric subplots of MIDDLESEX (a Muslim temple scam, a tension-fraught car chase, the invention of hot dogs that flex like biceps) are imbued with a tender, familial warmth that leads the reader to accept them with relative ease. Likewise, given the slightest chance, Cal, nee Callie, will win the affection and acceptance of readers who might instinctively shy away from a novel centered on such a character.

Eugenides manages to tuck a strange personal tale into the capaciousness of a traditional commercial epic, much as Cal's pseudo-penis is hidden away in his labial folds.

Unlike Gore Vidal's brilliantly abrasive gender-bending in his notorious MYRA BRECKINRIDGE and MYRON, or Chris Bohjalian's issue-oriented melodrama in the recent TRANS-SISTER RADIO, Eugenides opts for a sweetly comic --- and ultimately more persuasive --- approach to confounding sexual identities. Bypassing in-your-face gender politics, Eugenides focuses on undeniable in-your-bloodline realities, the "roller-coaster ride of a single gene through time."

"Sing now, O Muse, of the recessive mutation on my fifth chromosome!" joshes Cal, in mock Homeric style, as he launches into his epic family narrative, "…Sing how it passed through nine generations…how it blew like a seed across the sea to America…until it fell to earth in the fertile soil of my mother's own midwestern womb." Eugenides slyly reminds us that, however unique each of us may be, we are also entangled in genetic history's grand warp and weft.

While genetic history provides MIDDLESEX its subtext, American history is its backdrop. Eugenides aligns moments in the Stephanides' lives with keystone episodes in national development. When Grandfather Lefty arrives in Detroit he is briefly employed at the Ford Motor Company, where, thanks to impeccable research and virtuosic descriptive passages, Eugenides deftly etches the dehumanizing aspect of assembly line work. He also riffs on its long-term societal effects, wittily applying a bit of Darwinian terminology to keep his big themes bubbling beneath the surface:

"At first, workers rebelled. They quit in droves, unable to accustom their bodies to the new pace of the age. Since then, however, the adaptation has passed down: we've all inherited it to some degree, so that we plug right into joysticks and remotes, to repetitive motions of 100 kinds."

The Detroit race riots of 1967, white flight to the suburbs, the social divisiveness of the Nixon era, and the so-called sexual revolution all feed into Eugenides' impressively casual plotting, making MIDDLESEX believable despite occasional moments of too-fantastic absurdity (Cal's older brother is inexplicably named Chapter 11, a priest concocts a kidnapping scheme, Cal joins a burlesque show). One is able to soar with Eugenides' wilder flights of imagination, because he builds such a concrete world of perfect period detail: young Callie's 1972 medicine cabinet is stocked with "pink Daisy razors…a spray can of Psssssst instant shampoo…a tube of Dr. Pepper Lipsmacker…my Crazy Curl hair iron…and a shaker of Love's Baby Soft body powder."

There are moments as well when Eugenides captures the pulse of an era in his dialogue. Consider Chapter 11's explanation of his refusal to use deodorant during his hippie phase:

"I'm a human…This is what humans smell like."

He also turns down a family vacation to their ancestral hometown in Greece arguing that "Tourism is just another form of colonialism."

The most awkward spot in MIDDLESEX comes at the most awkward period of young Callie's life. At age 15 she begins to question her gender and sexuality after developing a crush on a female friend whose brother simultaneously lusts for Callie. As Jeffrey Eugenides proved in his debut novel, THE VIRGIN SUICIDES, he has a keen sense for the mysterious emotions of teenage attraction, the sometimes inseparable blend of the sexual and the romantic. Once again, here, he limns his characters' feelings with great precision. But because the main character is Callie --- and because we have long understood exactly what makes her feelings particularly exquisite --- the book's pace flags a bit as we await her discovery of what we already know.

After this brief lull, though, MIDDLESEX zooms through its immensely satisfying final 130 pages. When Callie is brought to New York to discuss her mixed gender with professional specialists, Eugenides --- once again thanks to clearly thorough research --- deftly navigates a broad, fascinating, but potentially confusing field of medicine (For a more in-depth but also marvelously readable study of intersexed children, see John Colapinto's nonfiction AS NATURE MADE HIM: The Boy Who Was Raised As A Girl.) Eugenides also uses his closing chapters to pull the characters of Tessie and Milton, Cal's parents, out from the broad panorama of family tapestry, providing readers with insightful close-up looks at their confusion and their unquestioning love of their child. To top it all off, right when you'd be perfectly happy to have MIDDLESEX wax to a humorously philosophical close, Eugenides delivers a slam-bang cinematic set-piece that shocks and soothes all at once.

Old-fashioned and new-fangled, loaded with smarts but not afraid of sentiment, MIDDLESEX is a joy to read.

Reviewed by Jim Gladstone on September 16, 2002

Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides

- Publication Date: September 16, 2002

- Genres: Fiction

- Paperback: 529 pages

- Publisher: Picador

- ISBN-10: 0312422156

- ISBN-13: 9780312422158

- How to Add a Guide

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Newsletters

Copyright © 2024 The Book Report, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Politics and Prose Bookstore 202-364-1919 Hours and Locations

Search form

- Advanced Search

Middlesex: A Novel (Paperback)

- Description

- About the Author

- Reviews & Media

Middlesex is the winner of the 2003 Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. A dazzling triumph from the bestselling author of The Virgin Suicides --the astonishing tale of a gene that passes down through three generations of a Greek-American family and flowers in the body of a teenage girl. "I was born twice: first, as a baby girl, on a remarkably smogless Detroit day of January 1960; and then again, as a teenage boy, in an emergency room near Petoskey, Michigan, in August of l974. . . My birth certificate lists my name as Calliope Helen Stephanides. My most recent driver's license...records my first name simply as Cal." So begins the breathtaking story of Calliope Stephanides and three generations of the Greek-American Stephanides family who travel from a tiny village overlooking Mount Olympus in Asia Minor to Prohibition-era Detroit, witnessing its glory days as the Motor City, and the race riots of l967, before they move out to the tree-lined streets of suburban Grosse Pointe, Michigan. To understand why Calliope is not like other girls, she has to uncover a guilty family secret and the astonishing genetic history that turns Callie into Cal, one of the most audacious and wondrous narrators in contemporary fiction. Lyrical and thrilling, Jeffrey Eugenides's Middlesex is an exhilarating reinvention of the American epic.

- Fiction / Literary

- Fiction / World Literature / American / 21st Century

“Part Tristram Shandy, part Ishmael, part Holden Caulfield, Cal is a wonderfully engaging narrator. . . A deeply affecting portrait of one family's tumultuous engagement with the American twentieth century.” — The New York Times “Expansive and radiantly generous. . . Deliriously American.” — The New York Times Book Review (cover review) “A towering achievement. . . . [Eugenides] has emerged as the great American writer that many of us suspected him of being.” — Los Angeles Times Book Review (cover review) “A big, cheeky, splendid novel. . . it goes places few narrators would dare to tread. . . lyrical and fine.” — The Boston Globe “An epic. . . This feast of a novel is thrilling in the scope of its imagination and surprising in its tenderness.” — People “Unprecedented, astounding. . . . The most reliably American story there is: A son of immigrants finally finds love after growing up feeling like a freak.” — San Francisco Chronicle Book Review “Middlesex is about a hermaphrodite in the way that Thomas Wolfe's Look Homeward, Angel is about a teenage boy. . . A novel of chance, family, sex, surgery, and America, it contains multitudes.” — Men's Journal “Wildly imaginative. . . frequently hilarious and touching.” — USA Today

|

|

Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides

general information | review summaries | our review | links | about the author

| Availability: | |

- Return to top of the page -

B+ : broad canvas, often very entertaining, but not entirely satisfactory as a whole

See our review for fuller assessment.

| Source | Rating | Date | Reviewer |

|---|---|---|---|

| . | 9/2002 | Stewart O'Nan | |

| A | 5/10/2002 | Kathryn Hughes | |

| The Economist | D | 5/10/2002 | . |

| . | 11/9/2003 | André Clavel | |

| . | 9/5/2003 | Hubert Spiegel | |

| A | 5/10/2002 | Mark Lawson | |

| . | 19/10/2002 | Julie Wheelwright | |

| London Rev. of Books | . | 3/10/2002 | Daniel Soar |

| The LA Times | A+ | 1/9/2002 | Jeff Turrentine |

| The Nation | . | 14/10/2002 | Keith Gessen |

| The New Criterion | A | 11/2002 | Max Watman |

| The New Republic | B+ | 7/10/2002 | James Wood |

| . | 9/9/2002 | John Homans | |

| A- | 9/9/2002 | Adam Begley | |

| . | 7/11/2002 | Daniel Mendelsohn | |

| The NY Times | A | 3/9/2002 | Michiko Kakutani |

| The NY Times Book Rev. | A | 15/9/2002 | Laura Miller |

| Newsweek | B- | 23/9/2002 | David Gates |

| A | 5/9/2002 | Andrew O'Hehir | |

| A+ | 22/9/2002 | David Kipen | |

| . | 5/10/2002 | Sebastian Smee | |

| A- | 13/10/2002 | Caroline Moore | |

| . | 28/9/2003 | Sam Gilpin | |

| . | 12/10/2002 | James Ley | |

| B- | 23/9/2002 | Richard Lacayo | |

| The Times | . | 25/9/2002 | Rachel Holmes |

| TLS | . | 4/10/2002 | Paul Quinn |

| . | 15/9/2002 | Lisa Zeidner | |

| Die Welt | . | 10/5/2003 | Wieland Freund |

| . | (21/2003) | Ulrich Greiner |

Review Consensus : No consensus, though most quite enthusiastic From the Reviews : " Middlesex is consistently whimsical in its scene-setting and use of language, but despite its vaudeville exchanges and niftily isolated punch lines, it's rarely out-and-out funny. The narration is baldly self-conscious in its cleverness. (...) (I)t's off proportionally, both section-to-section and overall, its two halves at odds, each interesting at times but neither truly satisfying, despite Eugenides's prodigious talent. Like Cal, it's damned by its own abundance, not quite sure what it wants to be." - Stewart O'Nan, The Atlantic Monthly "This might have resulted in a clumsy pastiche or a confused mess. But Eugenides combines a rigorous understanding of his sources (which include everything from Sophocles to Jeanette Winterson) with a wry and sprightly voice that is entirely original. The result is a masterful dissection and reassembling of the American Dream into a shape you will not quite have seen anywhere before." - Kathryn Hughes, Daily Telegraph "Like a boy trying on his father's suit, Middlesex is a small-fry in a big jacket. (...) Indeed, the prose in Middlesex is oppressively perky, with a plague of exclamation marks. (...) (T)he historical material feels stale and second-hand." - The Economist "Damit der Roman �ber der Fülle seiner Gegenstände nicht aus allen Nähten platzt und der Leser sich nicht schon nach zweihundert Seiten fühlt, wie ein Reiter, der aus dem Sattel gehoben wurde und nun von einem durchgegangenen Gaul mitgeschleift wird, hat der Autor gewisse Vorsichtsmaßnahmen ergriffen. Zu ihrer Vorbereitung waren beinahe acht Jahre nötig, so lange hat Eugenides nach eigenem Bekunden an Middlesex gearbeitet. Die Mühe hat sich gelohnt." - Hubert Spiegel, Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung "Finding new ways of telling the story, though, is clearly central to Eugenides' project as a novelist. (...) Eugenides continues to be the Joyce of the personal pronoun. The narrative tone -- best characterised as a sardonic empathy -- has possible progenitors in Muriel Spark and John Irving, but bears the individual imprint of Greek America." - Mark Lawson, The Guardian "Eugenides is good on period detail, providing brooding, bold sketches of the family barricaded in their home during the Detroit race riots of 1967, the decline of Nixon, the reverberations of the Turkish invasion of northern Cyprus. (...) Middlesex reminds us that those who fit awkwardly outside science's categories of sex, desire and gender have much to teach." - Julie Wheelwright, The Independent " Middlesex , in its magnificent circumambulation and in its suggestive gender-based possibilities, seems to promise strangeness, but it doesn't make good on its Olympian opening. All the book's magic -- if magic is what we hoped for -- is present in the seed of its idea. Anything wilder is prohibited by Cal's impeccable conservatism" - Daniel Soar, London Review of Books "Eugenides has had nearly a decade to relax, and the happy result is a novel that's as warm, expansive and generous as its predecessor wasn't. (...) Among many things, Middlesex is the author's love letter to a city that could probably use a few more. (...) Middlesex isn't just a respectable sophomore effort; it's a towering achievement, and it can now be stated unequivocally that Eugenides' initial triumph wasn't a one-off or a fluke. He has emerged as the great American writer that many of us suspected him of being." - Jeff Turrentine, The Los Angeles Times "(T)he novel is no country for reasonable men, and Middlesex often ends up reading like a compromise between divergent viewpoints, a move toward a sort of consensus novel, which, like the consensus historiography of the 1950s, would mute the fragmentation and bitterness of American society. (...) With its heart so clearly in the right place, its taste and intelligence so handsome, Middlesex is a book that's almost impossible to dislike even as you're bored by it; but if sexless, bloodless, realist Cal is the alternative it proposes, I'm with the phallocrats." - Keith Gessen, The Nation "On my first read, I felt Middlesex sometimes dull. I have come to realize that, considering its topic, dullness is a kind of genius. Think of the prurient possibilities here, the license to think of nothing but sex. A little boredom is welcome." - Max Watman, New Criterion " Middlesex , Jeffrey Eugenides's big, messy, intermittently amusing new novel, seems to make a similar jangling sound as it comes down the pike, top-heavy as it is with every reference that could possibly be relevant to the Greek experience in America. (...) Middlesex is a melting pot in which anything and everything -- stylistically, historically, genitally -- can be put to some use. But it's like a game of cards where everything's wild. The book is eventful, unpredictable, eager to entertain, but missing the tension a more disciplined approach would have provided." - John Homans, New York "Horrific events occur, cruel truths are discovered, passions build and crash, but Mr. Eugenides keeps the tone light -- almost, at times, breezy. Middlesex sweeps the reader along with easy grace and charm, tactfully concealing intelligence, sophistication and the ache of earned wisdom beneath bushels of inventive storytelling." - Adam Begley, The New York Observer "And yet Einheit is what Middlesex itself ultimately lacks. (...) The failure of the author to provide an authentic voice and personality for his creature presages larger intellectual failings." - Daniel Mendelsohn, The New York Review of Books "Part Tristram Shandy, part Ishmael, part Holden Caulfield, Cal (...) is a wonderfully engaging narrator (.....) But it's his emotional wisdom, his nuanced insight into his characters' inner lives, that lends this book its cumulative power. He has not only followed up on a precocious debut with a broader and more ambitious book, but in doing so, he has also delivered a deeply affecting portrait of one family's tumultuous engagement with the American 20th century." - Michiko Kakutani, The New York Times "Eugenides pitches a big tent, but one of the delights of Middlesex is how soundly it's constructed, with motifs and characters weaving through the novel's various episodes, pulling it tight. (...) (T)he novel's patron saint is Walt Whitman, and it has some of the shagginess of that poet's verse to go along with the exuberance. But mostly it is a colossal act of curiosity, of imagination and of love." - Laura Miller, The New York Times Book Review "Certainly, although his novel is blemished by elements of didacticism and prolixity, and he is not without the postmodern urge to turn clouds of suggestion into storms of fact, Eugenides has a simple confidence in his Greek material that disarms his vices." - James Wood, The New Republic "(I)ngenious, entertaining and -- I hate to say it -- ultimately not-so-moving (.....) Middlesex does as well as any book I know at melding self-conscious artifice and real-world history (.....) Cal eludes us. He/she is more a construct than a character, apparently existing to make a point about gender (.....) Will he/she get the girl/boy ? If you end up giving a Smyrna fig, you're a better man/woman than I am." - David Gates, Newsweek " Middlesex begins as a generous, tragicomic family chronicle of immigration and assimilation, becomes along the way a social novel about Detroit, perhaps the most symbolic of American cities, and incorporates a heartbreaking tale of growing up awkward and lonely in '70s suburbia. It's a big, affectionate and often hilarious book" - Andrew O'Hehir, Salon "Jeffrey Eugenides' unprecedented, astounding new novel, Middlesex . (...) And what language, what prose! Lots of novelists write beautifully about diurnal, mundane things, and Eugenides can do that with the best of them. But his rarer power resides in the ability to craft scenes whose freshness of incident matches their freshness of description. (...) Any book that can make a reader actively want to visit Detroit must have one honey of a tiger in its tank." - David Kipen, San Francisco Chronicle "(A)t over 500 pages, it�s too long. There are other problems, too. Although the writing is good, it is not uniformly so. Eugenides� style flits between the heartfelt (...), and the trashily journalistic (...), often several times within the same paragraph. But what is most grating is the narrator�s apparent need to wreck otherwise beautiful passages with irritating little infusions of self-consciousness. (...) (A) charming, witty, but ultimately disappointing example of the dangers of putting it all in, relating everything, smothering whole lives in blizzards of words." - Sebastian Smee, The Spectator "Jeffrey Eugenides's second novel is richly readable, but does not lie easy upon the imaginative digestion. (...) With so much to enjoy and admire, it seems churlish to carp. Yet the novel reminded me of a magnificently over-ripe Stilton. (...) What I did not like was the rind. Eugenides has some difficulty in holding together this sprawling, three-generational narrative" - Caroline Moore, Sunday Telegraph "The originality of Eugenides�s novel lies in the brilliance with which he enters into his protagonist�s mind and body, creating a sympathetic and utterly credible hero-cum-heroine." - Sam Gilpin, Sunday Times "Around the central fact of Cal's genetics, Eugenides builds a narrative flexible enough to take in broader questions of race and sex (or rather ethnicity and gender), while maintaining its focus on what is essentially an affectionate and immensely appealing family portrait." - James Ley, Sydney Morning Herald "Some of this footloose book is charming. Most of it is middling." - Richard Lacayo, Time "Not since Michel Foucault�s Herculine Barbin two decades ago has there been such a sustained first person narration about the coming of age of a hermaphrodite as offered by Jeffrey Eugenides� second novel, Middlesex ." - Rachel Holmes, The Times "Eugenides is a child of the era of deconstruction: difference is valued above identity. (...) That Eugenides manages to move us without sinking into sentiment shows how successfully he has avoided the tentacles of irony which grip so many writers of his generation." - Paul Quinn, Times Literary Supplement "The background material is capably handled and engaging enough, especially if you have special interest in either the history of Detroit or Greek immigrant culture. Eugenides can't always reliably distinguish a telling detail from a tedious one. (...) If Middlesex seems top-heavy on the gnarled family tree and skimpy on the fascinating blow-by-blow of Cal's burgeoning sexuality, be assured that Eugenides intends the uneasy balance." - Lisa Zeidner, The Washington Post "Literatur aus dem "melting pot": Jeffrey Eugenides' Roman Middlesex scheint das schlussendliche Wunderwerk der Anverwandlung im Prozess der Rückbesinnung auf die Tradition." - Wieland Freund, Die Welt "Der Roman könnte ebenso gut doppelt wie halb so dick sein, es würde ihm weder schaden noch nützen. (...) Er ist eben, wie man auf Deutsch sagt, ein Zwitter. Und zwitterhaft ist auch dieser Roman. Man kann viel aus ihm lernen, man langweilt sich selten. Er braust auf breiten Reifen und mit erstaunlicher Kraft durch ein pittoreskes Gel�nde. Letztlich ist es eine Sache des Geschmacks" - Ulrich Greiner, Die Zeit Please note that these ratings solely represent the complete review 's biased interpretation and subjective opinion of the actual reviews and do not claim to accurately reflect or represent the views of the reviewers. Similarly the illustrative quotes chosen here are merely those the complete review subjectively believes represent the tenor and judgment of the review as a whole. We acknowledge (and remind and warn you) that they may, in fact, be entirely unrepresentative of the actual reviews by any other measure.

The complete review 's Review :