Understanding the Four Functions of Behavior: A Comprehensive Guide

- by Rainbow Therapy

- August 31, 2023

Escape/Avoidance: Seeking Relief from Demands

Attention-seeking: craving social interaction, access to tangible items: obtaining desired objects, automatic reinforcement: internal satisfaction, functional assessment and intervention: a holistic approach.

- Functional Assessment:

- Individualized Interventions:

- Positive Behavior Support:

- Skill Building:

- Collaboration and Training:

- Continuous Monitoring:

- Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA) and the Four Functions:

- Ethical Considerations:

- Real-Life Applications:

- Case Studies: Illustrating the Four Functions in Action:

Case Study 1: Escape/Avoidance Function

Case study 2: attention-seeking function, case study 3: access to tangible items function, case study 4: automatic reinforcement function, recent posts.

- The Impact of Autism on Learning

- Autism and IQ: What’s the Connection?

- How to Reduce Impulsive Behavior in Autism

- Is Short Attention Span a Sign of Autism?

- Does Autism Cause Obsession?

Recent Comments

- September 2024

- August 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- ABA Therapy

- Autism and Mental Health

- Autism and School

- Autism Causes

- Autism Comorbidities

- Autism Daily Living

- autism diagnosis

- Autism Interventions

- Autism Sensory Issues

- Autism Statistics

- Autism Support

- Autism Tools

- communication

- Parents' Guide

- Uncategorized

Understanding the Four Functions of Behavior: A Comprehensive Guide

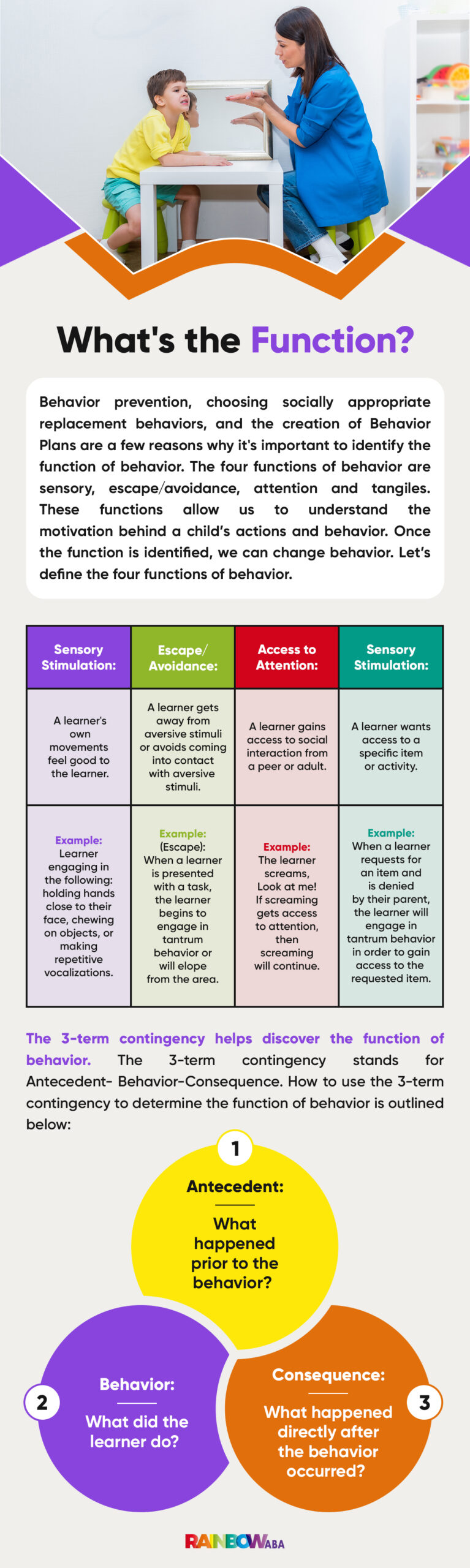

Ever wonder why people act the way they do? Understanding the four functions of behavior can shed light on this mystery. These functions—attention, escape, access to tangibles, and sensory stimulation—serve as the primary reasons behind most human actions. Grasping these concepts can help you navigate social interactions and improve communication.

Whether you’re a parent, teacher, or simply curious about human behavior, knowing these functions can offer invaluable insights. By identifying the root causes of actions, you can address issues more effectively and foster healthier relationships. Let’s dive into the fascinating world of behavior and uncover what drives us all.

Key Takeaways

- Understanding Behavior: The four primary functions of behavior—attention, escape, access to tangibles, and sensory stimulation—help explain why people act the way they do.

- Application in Education: Recognizing these functions allows teachers to develop strategies that address disruptive behaviors, improving classroom management and learning outcomes.

- Parenting Insights: Knowing these behavioral functions enables parents to understand and respond more effectively to their child’s actions, fostering healthier family dynamics.

- Workplace Interactions: In professional settings, understanding these functions can improve employee interactions and help identify the root causes of workplace challenges.

- Therapeutic Interventions: Therapists leverage these functions to design effective behavior modification plans, especially for individuals with developmental disorders.

Understanding the Four Functions of Behavior

Understanding the four functions of behavior is crucial for interpreting human actions. These functions include attention, escape, access to tangibles, and sensory stimulation.

Explanation of Behavior Functions

- Attention : The attention function addresses actions performed to gain social attention or reactions from others. For instance, children might cry or shout to get their parents’ attention.

- Escape : The escape function pertains to behaviors aimed at avoiding or escaping from unpleasant situations or demands. A student, for example, may feign illness to avoid a test.

- Access to Tangibles : This function involves actions taken to gain access to physical items or preferred activities. An example is a child performing chores to earn extra screen time.

- Sensory Stimulation : Sensory stimulation encompasses behaviors driven by the inherent pleasure or sensory feedback they provide. Examples include nail biting or humming.

- Educational Environments : Recognizing these functions helps teachers tailor strategies to address disruptive classroom behaviors effectively, enhancing learning outcomes.

- Parenting : Knowledge of behavioral functions assists parents in understanding why their child behaves a certain way, promoting better responses to tantrums and non-compliance.

- Workplace : In professional settings, understanding these functions aids in improving employee interactions and identifying root causes of workplace challenges.

- Therapeutic Interventions : Therapists use this knowledge to design effective behavior modification plans, particularly for individuals with developmental disorders.

Understanding these functions in various settings optimizes interactions and fosters positive behaviors.

The Function of Escape

Escape-driven behavior functions to help individuals avoid unpleasant situations. By identifying this function, you can develop effective strategies to address and modify these behaviors.

How Escape Influences Behavior

Escape influences behavior by motivating individuals to avoid tasks, environments, or interactions they find stressful or aversive. This behavior often manifests in avoidance tactics such as task refusal, running away, or distraction-seeking activities. For instance, a student may exhibit escape behavior by pretending to be sick to avoid a difficult test or class. Recognizing these behaviors provides insight into the underlying causes and helps in formulating targeted interventions.

Practical Examples and Strategies

Understanding practical examples of escape behavior is essential for effective intervention. In an educational setting, a student might continuously ask to use the restroom to avoid a challenging assignment. In the workplace, an employee could procrastinate on a project to evade the pressure of a tight deadline.

Implementing strategies to combat escape behavior involves altering the environment or the task to reduce aversiveness. Offering support, breaking tasks into manageable steps, and incorporating positive reinforcement for task completion can mitigate escape responses. For example, a teacher might provide additional assistance or modify a difficult assignment to make it more accessible, thereby reducing the student’s desire to escape.

The Function of Attention

Behavior seeking attention operates to gain interaction or acknowledgment from others. Attention-seeking behaviors, reinforcing the connection, play a significant role in driving actions.

Attention-Seeking Behaviors

Attention-seeking behaviors aim to attract others’ focus. Instances include interrupting conversations, making loud noises, or exhibiting exaggerated emotions. Children might throw tantrums or act out in classrooms. In workplaces, employees might interrupt meetings or excessively seek validation. Recognizing these behaviors helps in addressing them effectively.

Effective Interventions

Effective interventions provide alternatives to attention-seeking behaviors. Establish clear expectations and consistent responses to manage such behaviors. Praise appropriate behaviors to reinforce positive actions. Providing scheduled attention times aids in reducing disruptive behaviors. Additionally, teaching self-regulation skills empowers individuals to seek attention appropriately. Incorporating these strategies creates a balanced approach to managing attention-driven behaviors.

The Function of Tangibles

The function of tangibles drives individuals to seek physical items or activities. Understanding this function helps you address specific behaviors effectively.

Behavior Driven by Tangible Rewards

Behavior driven by tangible rewards seeks to gain access to desired items or activities, like toys, snacks, or tech devices. Children might act out to receive a favorite toy, while adults might work extra hours for a bonus. This behavior often manifests as persistent requests or actions to obtain the sought-after item. Recognizing tangible-reward-driven behavior aids in creating targeted interventions.

Management Techniques in Education and Parenting

Education and parenting benefit from structured techniques to manage tangible-reward-driven behavior. Implementing clear, consistent rules regarding access to items can reduce undesirable behaviors. Reward systems, like token economies, motivate positive actions. For instance, you reward a child with a token each time they complete a task, which they can exchange for a preferred item. Engaging children in setting goals around receiving tangible rewards fosters a sense of ownership and accountability. Redirecting efforts toward appropriate methods of obtaining the desired items also encourages positive behavior.

The Function of Sensory Stimulation

The function of sensory stimulation involves behaviors driven by the need for sensory feedback. These actions fulfill internal sensory needs rather than external demands or social interactions.

Identifying Sensory Behaviors

Sensory behaviors manifest in actions aimed at achieving specific sensory input. Examples include hand-flapping, rocking, or humming. You can observe these behaviors across various environments, from classrooms to homes, especially among individuals seeking self-regulation or comfort. In evaluating sensory behaviors, note the repetitive nature and the absence of external stimuli influence, focusing instead on the internal sensory gratification they provide.

Coping Mechanisms and Support

Supporting individuals with sensory-driven behaviors requires tailored strategies. Create environments that offer sensory alternatives, like fidget toys or weighted blankets, to replace inappropriate behaviors. Teach self-regulation techniques to help them manage sensory needs independently. Providing a sensory-friendly space can reduce stress and improve focus, promoting a balanced approach to meeting sensory needs. Implementing these support strategies fosters a supportive atmosphere that respects individual sensory preferences and enhances overall well-being.

Understanding the four functions of behavior—attention, escape, access to tangibles, and sensory stimulation—provides valuable insights into why people act the way they do. By recognizing these underlying motivations, you can better navigate social dynamics and address behavioral challenges effectively. Whether you’re a parent, teacher, or professional, applying targeted strategies can promote positive behaviors and improve interactions. Embracing this knowledge enhances your ability to foster healthier relationships and create supportive environments tailored to individual needs.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the four functions of behavior.

The four functions of behavior are attention, escape, access to tangibles, and sensory stimulation. These functions help understand what drives human actions and interactions.

How does understanding behavior functions benefit parents and teachers?

Understanding behavior functions allows parents and teachers to effectively address challenges, enhance communication, and promote positive behaviors, leading to improved social dynamics and healthier relationships.

What is escape-driven behavior?

Escape-driven behavior is when individuals try to avoid unpleasant situations, tasks, or interactions. This can include actions like task refusal or seeking distractions.

Can you provide an example of escape behavior?

An example of escape behavior is a student asking to use the restroom to avoid a difficult assignment. This tactic helps them evade stressful tasks.

How can escape behavior be managed?

Managing escape behavior involves modifying the environment or tasks to be less aversive, providing support, breaking tasks into smaller steps, and offering positive reinforcement for completing tasks.

What are attention-seeking behaviors?

Attention-seeking behaviors are actions aimed at attracting interaction or acknowledgment from others, such as interrupting conversations or exaggerating emotions.

How can attention-seeking behaviors be addressed?

Effective strategies include setting clear expectations, providing consistent responses, praising appropriate behaviors, scheduling attention times, and teaching self-regulation skills.

What motivates behavior driven by access to tangibles?

Behavior driven by access to tangibles is motivated by the desire for physical items or activities, such as toys, snacks, or tech devices.

How can tangible-reward-driven behaviors be managed?

Managing these behaviors involves implementing clear, consistent rules about item access, using reward systems like token economies, and encouraging positive actions to foster ownership and accountability.

What is sensory-driven behavior?

Sensory-driven behavior involves actions aimed at achieving specific sensory input, fulfilling internal sensory needs rather than external demands or social interactions.

How can individuals with sensory-driven behaviors be supported?

Support can include creating sensory-friendly environments, offering sensory alternatives, teaching self-regulation techniques, and providing a supportive atmosphere that respects individual sensory preferences.

Related Posts

504 plan florida (3 bonus tips for students), 504 plan eligibility (important points for students).

Sign up for FREE Professional Development!

- Published on May 20, 2020

- | Blog

- | by Andrea Banks

How to Better Understand the Four Functions of Behavior

There’s a reason why we act how we act. Our behaviors make sense and have functions, even if that isn’t always clear.

If a child is behaving in an unfavorable way, it’s because the behavior is meeting a specific need.

Learning about the four functions of behavior is important for teaching children and becoming a better educator. Keep reading to understand what the functions are so that you can learn how to modify the behavior in the future.

Understanding That Behaviors Occur for a Reason

Before we break down the 4 functions of behavior, it’s important to have the context behind it. ABA or Applied Behavior Analysts often use this concept to identify why a person is continuing to engage in a behavior, believing that behavior typically serves a function or purpose for the individual.

This is basically referring to the idea that there’s a reason why a behavior is occurring. It can be difficult to understand why an adult or child is engaging in a behavior, especially if it’s something negative like aggression or self-injury, but the underlying function will help explain it.

Behavior can also serve more than a single function at one time. A child might act out in order to gain attention from a teacher, and out of frustration for being required to complete an academic task.

Understanding the function also helps to guide a treatment plan if problematic behaviors are occurring. So what are the ABA four functions of behavior?

1. Social Attention

The first function is social attention or attention-seeking. The goal of attention-seeking behavior is to gain the attention of a nearby adult or another child.

For example, a child might whine in order to get attention from their parents. They may also engage in certain behaviors to get others to laugh with them or play with them, or they may just want people to look at them.

They may not always be seeking positive attention. The child might be behaving in a certain way to elicit anger or scolding from their parent or teacher.

Not all behaviors seek to gain something like attention-seeking. When a child engages in an escape behavior, he or she is trying to get away from something or avoid it altogether.

For example, in a home setting, a child might run away if they don’t want to take a bath. If a child is misbehaving in the classroom by putting their head down on the desk when presented with an assignment, they are attempting to escape the work.

It’s possible that escape behaviors are a result of lacking motivation for performing the task or that the task is too difficult. When trying to understand why a child might be engaging in escape behaviors, it can be helpful to take a step back and provide easier tasks to help them slowly understand the work.

3. Seeking Access to Tangibles or Activities

The third function of a behavior is seeking access to tangibles or activities. This is referring to the concept that some children engage in behavior so that they can gain access to a desired item or activity.

This behavior is the opposite of escape since the child is doing something in order to get what he or she wants.

For example, the child might scream or cry at a store so that the adult will buy them the toy they want. It can also be seen more positively if a child is getting dressed or doing their chores quickly so that they can go play.

4. Sensory Stimulation

This behavior is referring to stimulating the senses, or self-stimulating. This behavior functions to give the child some kind of internal sensation that pleases them or removes an internal sensation they don’t like.

A simple example of this is scratching. A child might scratch their skin due to bug bites or sunburn to relieve the feeling of itching.

This will certainly vary depending on the child. One child might enjoy and feel sensory stimulation from fast sports, but another child might rock back and forth to de-stimulate his or her senses.

How Function and Reinforcement Work

We’ve already reviewed that behavior occurs because of the function that it’s serving the child. It’s important to also understand how these behaviors serve to reinforce or maintain an outcome. Behavior can be understood in terms of both function and reinforcement.

In general, behaviors serve two functions. A behavior is an attempt to get something or an attempt to get away from something. So when a behavior works to get something for the child, it’s called positive reinforcement.

The opposite is also true. If a behavior works to get the child away from something or have something be taken away, it’s referred to as negative reinforcement.

Understanding Positive and Negative Reinforcement

It’s helpful to break down positive and negative reinforcement further to better understand them. Both types of reinforcement can be understood in terms of social and automatic reinforcement.

Social positive reinforcement happens when behavior gets the child something through the actions of another. For example, a child might ask her mother for a cup of juice. The action is required by the mother for the positive reinforcement of the juice.

Automatic positive reinforcement happens without needing anyone else. So the child is able to get what they want on their own. For example, a child is pouring her own cup of juice.

The opposite of both of these concepts are social negative reinforcement and automatic negative reinforcement. The goal of social negative reinforcement is to get the child away from something or have something be taken away through the actions of someone else. So for example, a child might ask for their mother to take the fruit off their plate.

Similarly, the goal of automatic negative reinforcement is to get something away from the child through their own actions. The child might push vegetables or fruit off their plate if they don’t desire them.

Positive and negative reinforcement further explain the functions of behavior.

The Four Functions of Behavior Help to Educators Understand Children

A behavior occurs for a reason. Learning the four functions of behavior will help you to understand a child’s motivation behind actions or behaviors within the classroom.

Plus, grasping both positive and negative reinforcement will paint the full picture of why a child is acting a certain way.

Click here to register for our webinar and learn more about managing behavior.

Modernize your District's Behavior Management with research-based best-practices.

Related posts.

6620 Acorn Dr Oklahoma City, OK 73151

Contact Us 888-542-4265 [email protected]

About Us Blog Webinars Free PD Newsletter Application Login Privacy Policy

Overview Behavior Management Plans Functional Behavior Assessments Strategies Reporting Professional Development Product Training Resources Support SEL Skills

Streamlining Behavior Interventions Positive Behavior Intervention & Supports Restorative Practices Significant Disproportionality Bullying Prevention Family & Community Engagement

Understanding behavior as communication: A teacher’s guide

By Amanda Morin

Expert reviewed by Kristin J. Carothers, PhD

Think of the last time a student called out in class, pushed in line, or withdrew by putting their head down on their desk. What was their behavior telling you?

In most cases, behavior is a sign they may not have the skills to tell you what they need. Sometimes, students may not even know what they need. What are your students trying to communicate? What do they need, and how can you help?

Respond to students, not their behaviors

First, know that when students act out, those actions can bring about emotions in teachers and other adults. Given all of the pressures placed on teachers, you may already feel stressed or emotional. It’s normal to take students’ behaviors personally because of your own feelings and needs in the moment.

One way to reframe your thinking is to respond to the student, not the behavior. Start by considering the life experiences that students bring to the classroom.

Some students who learn and think differently have negative past experiences with teachers and school. Others may come from cultures in which speaking up for their needs in front of the whole class isn’t appropriate.

Students who have food insecurity may push others out of the way at lunchtime to make sure they get something to eat. Students who have experienced trauma can often be wary of others. They may be hypervigilant and prone to what looks like overreactions to simple things. Keeping these experiences in mind can help you respond to the reasons for student behavior and not simply react to or correct the behavior itself.

What student behavior is telling you

Figuring out the function of, or the reasons behind, a behavior is critical for finding an appropriate response or support. Knowing the function can also help you find ways to prevent behavior issues in the future.

Learning for Justice (formerly Teaching Tolerance), an organization that provides resources for educators to create civil and inclusive school communities, offers the acronym EATS to highlight some possible functions of behavior. EATS stands for E scape, A ttention, T angible gains, and S ensory needs. Here’s a breakdown of what that means:

Escape: Some students use behavior to avoid a task, demand, situation, or even person they find difficult. Escape behavior can also be quiet, like students who ask to use the bathroom every time it’s their turn to read.

Example: Sofia, who struggles with reading, often breaks the rules during her language arts class. She refuses to take out her book during silent reading time. She eventually throws it to the floor, calls the teacher a name, and gets sent to the office.

What her behavior is saying: Sofia is communicating that she’s struggling with reading and would rather get into trouble than be asked to do a task that is challenging for her without the support she needs.

Attention: Some students behave in ways that are designed to gain attention. They may feel unsure about when or whether they’ll get your attention otherwise. Attention-seeking can play out in positive behaviors as well, such as when students work hard on a task to get your approval.

Example: Nevaeh is what you might call a clingy student. She really wants to show how hard she worked on her math. She puts up her hand and calls the teacher’s name over and over. When she doesn’t get a response, she walks across the room, taps the teacher’s arm, and yanks on her sleeve.

What her behavior is saying: Nevaeh is trying to tell you that she’s unsure about her strengths. She’s communicating that she needs your approval to be sure she’s done a good job on her math.

Tangible gains: Some student behavior is aimed at getting what they want, when they want it. This type of behavior is very common for students who struggle with impulsivity or flexible thinking.

Example: Joseph often talks back to his teacher and comes off as disrespectful. He misses or ignores his teacher’s hand gestures to lower his voice. Joseph gets agitated when he’s told to stop. He argues that he’s just trying to get answers to his questions. He believes the teacher should respond to him right away.

What his behavior is saying: Joseph is communicating that he needs more information to understand the lesson. From past experiences, he may have learned to talk or question the teacher continuously until he receives a response. His behavior represents trouble with communication skills. That means there’s an opportunity to teach the social skill of waiting to talk. In not responding to the teacher’s subtle cues to stop talking, he’s not simply being belligerent. He’s showing that he needs explicit help learning to respond to cues appropriately to have his needs met.

Sensory needs: Students’ brains are constantly taking in information from their senses. For some, processing that stream of input is a struggle . “Sensory seekers” underreact to sensory input or need more of it to function. “Sensory avoiders” overreact to sensory input. They may become overwhelmed and hyperactive. Those behaviors become problematic when they are disruptive or interfere with learning.

Example: Ethan tends to be “hands on” with other students. It’s particularly a problem when he’s standing in line. He complains that he feels crowded. He may push other students out of the way.

What his behavior is saying: Ethan is trying to let you know that he’s overwhelmed by being so close to other students. He is literally moving them out of his personal space, which may be a larger area than is typical for others.

Harness the power of collaboration

It can be hard to figure out the function of a student’s behavior, especially when there are learning and thinking differences at play. Most schools have a collaborative teacher assistance team that can help you understand student behaviors. Those teams are typically made up of special and general education teachers, as well as other professionals, like a school psychologist or a counselor.

Talk with the team about whether an observation by a member of the team or a formal functional behavioral assessment (FBA) is necessary to gather data. This information can lead to a more in-depth look at the reasons behind the student’s behavior.

When you work together to understand the behavior, you’ll be better prepared to help students identify what they need and how to communicate that more appropriately.

Explore related topics

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

16.2 Sociological Perspectives on Education

Learning objectives.

- List the major functions of education.

- Explain the problems that conflict theory sees in education.

- Describe how symbolic interactionism understands education.

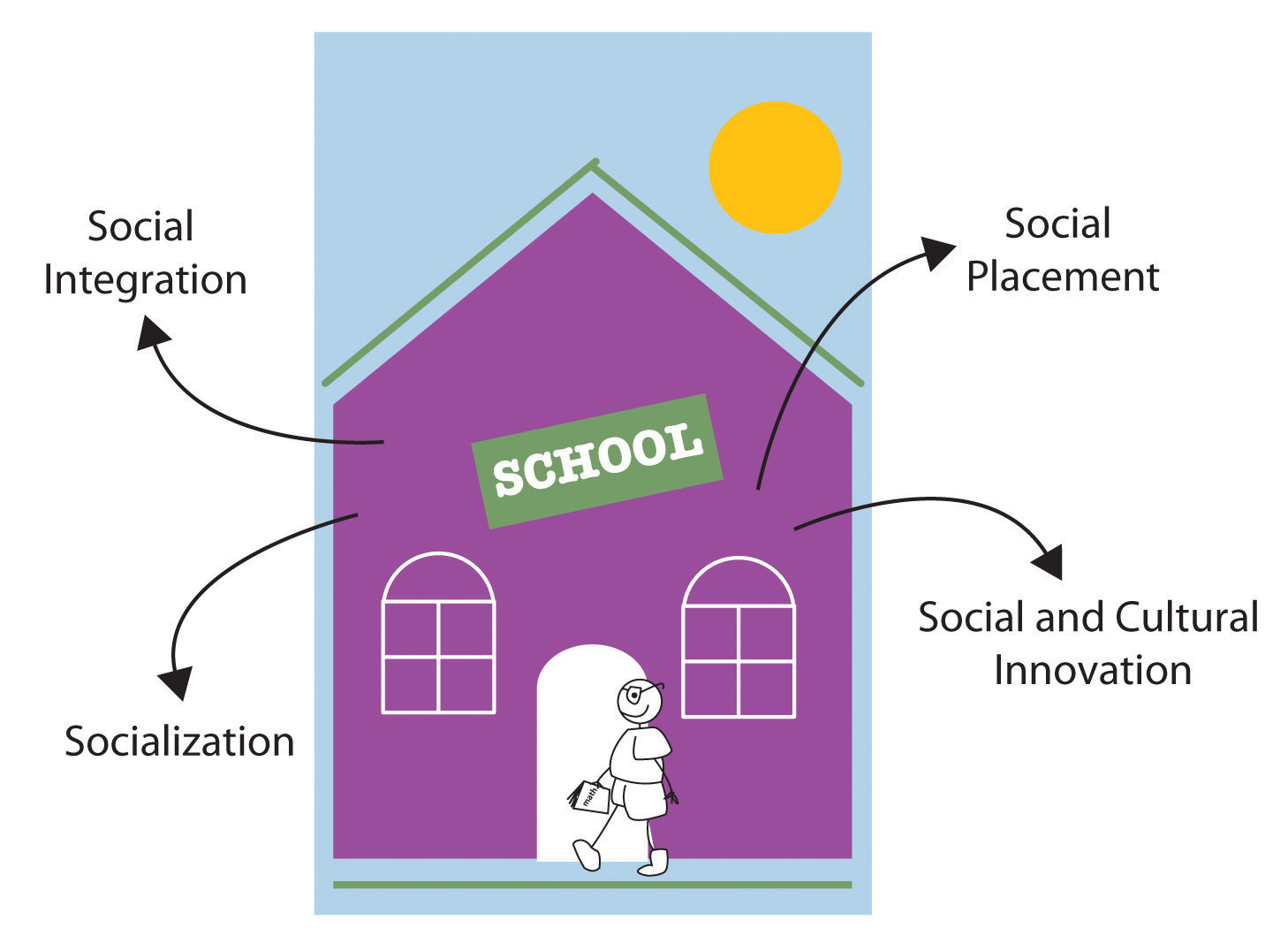

The major sociological perspectives on education fall nicely into the functional, conflict, and symbolic interactionist approaches (Ballantine & Hammack, 2009). Table 16.1 “Theory Snapshot” summarizes what these approaches say.

Table 16.1 Theory Snapshot

| Theoretical perspective | Major assumptions |

|---|---|

| Functionalism | Education serves several functions for society. These include (a) socialization, (b) social integration, (c) social placement, and (d) social and cultural innovation. Latent functions include child care, the establishment of peer relationships, and lowering unemployment by keeping high school students out of the full-time labor force. |

| Conflict theory | Education promotes social inequality through the use of tracking and standardized testing and the impact of its “hidden curriculum.” Schools differ widely in their funding and learning conditions, and this type of inequality leads to learning disparities that reinforce social inequality. |

| Symbolic interactionism | This perspective focuses on social interaction in the classroom, on the playground, and in other school venues. Specific research finds that social interaction in schools affects the development of gender roles and that teachers’ expectations of pupils’ intellectual abilities affect how much pupils learn. |

The Functions of Education

Functional theory stresses the functions that education serves in fulfilling a society’s various needs. Perhaps the most important function of education is socialization . If children need to learn the norms, values, and skills they need to function in society, then education is a primary vehicle for such learning. Schools teach the three Rs, as we all know, but they also teach many of the society’s norms and values. In the United States, these norms and values include respect for authority, patriotism (remember the Pledge of Allegiance?), punctuality, individualism, and competition. Regarding these last two values, American students from an early age compete as individuals over grades and other rewards. The situation is quite the opposite in Japan, where, as we saw in Chapter 4 “Socialization” , children learn the traditional Japanese values of harmony and group belonging from their schooling (Schneider & Silverman, 2010). They learn to value their membership in their homeroom, or kumi , and are evaluated more on their kumi ’s performance than on their own individual performance. How well a Japanese child’s kumi does is more important than how well the child does as an individual.

A second function of education is social integration . For a society to work, functionalists say, people must subscribe to a common set of beliefs and values. As we saw, the development of such common views was a goal of the system of free, compulsory education that developed in the 19th century. Thousands of immigrant children in the United States today are learning English, U.S. history, and other subjects that help prepare them for the workforce and integrate them into American life. Such integration is a major goal of the English-only movement, whose advocates say that only English should be used to teach children whose native tongue is Spanish, Vietnamese, or whatever other language their parents speak at home. Critics of this movement say it slows down these children’s education and weakens their ethnic identity (Schildkraut, 2005).

A third function of education is social placement . Beginning in grade school, students are identified by teachers and other school officials either as bright and motivated or as less bright and even educationally challenged. Depending on how they are identified, children are taught at the level that is thought to suit them best. In this way they are prepared in the most appropriate way possible for their later station in life. Whether this process works as well as it should is an important issue, and we explore it further when we discuss school tracking shortly.

Social and cultural innovation is a fourth function of education. Our scientists cannot make important scientific discoveries and our artists and thinkers cannot come up with great works of art, poetry, and prose unless they have first been educated in the many subjects they need to know for their chosen path.

Figure 16.1 The Functions of Education

Schools ideally perform many important functions in modern society. These include socialization, social integration, social placement, and social and cultural innovation.

Education also involves several latent functions, functions that are by-products of going to school and receiving an education rather than a direct effect of the education itself. One of these is child care . Once a child starts kindergarten and then first grade, for several hours a day the child is taken care of for free. The establishment of peer relationships is another latent function of schooling. Most of us met many of our friends while we were in school at whatever grade level, and some of those friendships endure the rest of our lives. A final latent function of education is that it keeps millions of high school students out of the full-time labor force . This fact keeps the unemployment rate lower than it would be if they were in the labor force.

Education and Inequality

Conflict theory does not dispute most of the functions just described. However, it does give some of them a different slant and talks about various ways in which education perpetuates social inequality (Hill, Macrine, & Gabbard, 2010; Liston, 1990). One example involves the function of social placement. As most schools track their students starting in grade school, the students thought by their teachers to be bright are placed in the faster tracks (especially in reading and arithmetic), while the slower students are placed in the slower tracks; in high school, three common tracks are the college track, vocational track, and general track.

Such tracking does have its advantages; it helps ensure that bright students learn as much as their abilities allow them, and it helps ensure that slower students are not taught over their heads. But, conflict theorists say, tracking also helps perpetuate social inequality by locking students into faster and lower tracks. Worse yet, several studies show that students’ social class and race and ethnicity affect the track into which they are placed, even though their intellectual abilities and potential should be the only things that matter: white, middle-class students are more likely to be tracked “up,” while poorer students and students of color are more likely to be tracked “down.” Once they are tracked, students learn more if they are tracked up and less if they are tracked down. The latter tend to lose self-esteem and begin to think they have little academic ability and thus do worse in school because they were tracked down. In this way, tracking is thought to be good for those tracked up and bad for those tracked down. Conflict theorists thus say that tracking perpetuates social inequality based on social class and race and ethnicity (Ansalone, 2006; Oakes, 2005).

Social inequality is also perpetuated through the widespread use of standardized tests. Critics say these tests continue to be culturally biased, as they include questions whose answers are most likely to be known by white, middle-class students, whose backgrounds have afforded them various experiences that help them answer the questions. They also say that scores on standardized tests reflect students’ socioeconomic status and experiences in addition to their academic abilities. To the extent this critique is true, standardized tests perpetuate social inequality (Grodsky, Warren, & Felts, 2008).

As we will see, schools in the United States also differ mightily in their resources, learning conditions, and other aspects, all of which affect how much students can learn in them. Simply put, schools are unequal, and their very inequality helps perpetuate inequality in the larger society. Children going to the worst schools in urban areas face many more obstacles to their learning than those going to well-funded schools in suburban areas. Their lack of learning helps ensure they remain trapped in poverty and its related problems.

Conflict theorists also say that schooling teaches a hidden curriculum , by which they mean a set of values and beliefs that support the status quo, including the existing social hierarchy (Booher-Jennings, 2008) (see Chapter 4 “Socialization” ). Although no one plots this behind closed doors, our schoolchildren learn patriotic values and respect for authority from the books they read and from various classroom activities.

Symbolic Interactionism and School Behavior

Symbolic interactionist studies of education examine social interaction in the classroom, on the playground, and in other school venues. These studies help us understand what happens in the schools themselves, but they also help us understand how what occurs in school is relevant for the larger society. Some studies, for example, show how children’s playground activities reinforce gender-role socialization. Girls tend to play more cooperative games, while boys play more competitive sports (Thorne, 1993) (see Chapter 11 “Gender and Gender Inequality” ).

Another body of research shows that teachers’ views about students can affect how much the students learn. When teachers think students are smart, they tend to spend more time with them, to call on them, and to praise them when they give the right answer. Not surprisingly these students learn more because of their teachers’ behavior. But when teachers think students are less bright, they tend to spend less time with them and act in a way that leads the students to learn less. One of the first studies to find this example of a self-fulfilling prophecy was conducted by Robert Rosenthal and Lenore Jacobson (1968). They tested a group of students at the beginning of the school year and told their teachers which students were bright and which were not. They tested the students again at the end of the school year; not surprisingly the bright students had learned more during the year than the less bright ones. But it turned out that the researchers had randomly decided which students would be designated bright and less bright. Because the “bright” students learned more during the school year without actually being brighter at the beginning, their teachers’ behavior must have been the reason. In fact, their teachers did spend more time with them and praised them more often than was true for the “less bright” students. To the extent this type of self-fulfilling prophecy occurs, it helps us understand why tracking is bad for the students tracked down.

Research guided by the symbolic interactionist perspective suggests that teachers’ expectations may influence how much their students learn. When teachers expect little of their students, their students tend to learn less.

ijiwaru jimbo – Pre-school colour pack – CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Other research focuses on how teachers treat girls and boys. Several studies from the 1970s through the 1990s found that teachers call on boys more often and praise them more often (American Association of University Women Educational Foundation, 1998; Jones & Dindia, 2004). Teachers did not do this consciously, but their behavior nonetheless sent an implicit message to girls that math and science are not for girls and that they are not suited to do well in these subjects. This body of research stimulated efforts to educate teachers about the ways in which they may unwittingly send these messages and about strategies they could use to promote greater interest and achievement by girls in math and science (Battey, Kafai, Nixon, & Kao, 2007).

Key Takeaways

- According to the functional perspective, education helps socialize children and prepare them for their eventual entrance into the larger society as adults.

- The conflict perspective emphasizes that education reinforces inequality in the larger society.

- The symbolic interactionist perspective focuses on social interaction in the classroom, on school playgrounds, and at other school-related venues. Social interaction contributes to gender-role socialization, and teachers’ expectations may affect their students’ performance.

For Your Review

- Review how the functionalist, conflict, and symbolic interactionist perspectives understand and explain education. Which of these three approaches do you most prefer? Why?

American Association of University Women Educational Foundation. (1998). Gender gaps: Where schools still fail our children . Washington, DC: American Association of University Women Educational Foundation.

Ansalone, G. (2006). Tracking: A return to Jim Crow. Race, Gender & Class, 13 , 1–2.

Ballantine, J. H., & Hammack, F. M. (2009). The sociology of education: A systematic analysis (6th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Battey, D., Kafai, Y., Nixon, A. S., & Kao, L. L. (2007). Professional development for teachers on gender equity in the sciences: Initiating the conversation. Teachers College Record, 109 (1), 221–243.

Booher-Jennings, J. (2008). Learning to label: Socialisation, gender, and the hidden curriculum of high-stakes testing. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29 , 149–160.

Grodsky, E., Warren, J. R., & Felts, E. (2008). Testing and social stratification in American education. Annual Review of Sociology, 34 (1), 385–404.

Hill, D., Macrine, S., & Gabbard, D. (Eds.). (2010). Capitalist education: Globalisation and the politics of inequality . New York, NY: Routledge; Liston, D. P. (1990). Capitalist schools: Explanation and ethics in radical studies of schooling . New York, NY: Routledge.

Jones, S. M., & Dindia, K. (2004). A meta-analystic perspective on sex equity in the classroom. Review of Educational Research, 74 , 443–471.

Oakes, J. (2005). Keeping track: How schools structure inequality (2nd ed.). New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom . New York, NY: Holt.

Schildkraut, D. J. (2005). Press “one” for English: Language policy, public opinion, and American identity . Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Schneider, L., & Silverman, A. (2010). Global sociology: Introducing five contemporary societies (5th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Thorne, B. (1993). Gender play: Girls and boys in school . New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Sociology Copyright © 2016 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

NEW!! Podcast is Live! Listen to the Misfit Behaviorists Now!

The 4 Functions of Behavior

- September 9, 2022

- No Comments

What are the functions of behavior?

Everything we do has a reason behind it, right? In special education , ABA , and counseling settings, we are often asked to address challenging behavior—behavior that impedes the learning of the student or that of others. Whether you have a reluctant learner , you're working on an FBA , or simply want to be proactive in your teaching strategies, thinking about behavior functions is where to start!

One way to analyze challenging behavior is start with the WHY… the FUNCTION of the behavior. It's not the ONLY thing we do, but it's a BIG thing, so let's dive in.

Form does not equal Function

First, a word. Many times in my career, I received requests for behavioral support for a student which typically included information about what the student was DOING that was disrupting the class or setting. From the standpoint of a behavior analyst, I'm much less interested in what a behavior looked like as I am about why it's happening in the first place.

“I could be yelling because I want your attention, or I could be yelling because I want that cookie, or I could be yelling because my tummy hurts.”

This is why we talk so much about function. Learning what the student is saying with their behavior will better guide us in our decision of what strategies to try and also why we focus so much on communication! So when we ask lots of questions about what was happening before a behavior and what happened after a behavior, this is why.

TWO functions of behavior

We will expand more on this, but if you really hone in on the functions of behavior, you can refine it to just two things: something you want, and something you don't want. We're either trying to get something or avoid something in about everything we do. For the most part, however, we talk about the 4 functions of behavior…

What are the FOUR functions of behavior?

The most common categories that functions of behavior fall into are: Access, Attention, Escape, and Sensory. You'll hear them called different things from different organizations, and they've evolved over time. You may also hear “control” and “medical” as possible functions, but those 4 functions are the most accepted and referred to in all the literature, so I'll focus on those.

Some Data Collection Ideas for You...

Functions of behavior -- access or tangible, "i want something".

This could be items, activities, food, whatever.

Examples : Jacob is shopping with mom. Jacob sees a candy bar. Jacob cries and pulls on mom. Mom gives Jacob the candy bar. Jacob stops crying.

Janie hits another child at recess because she wants the ball.

Jude drops to the floor because he wanted to be line leader.

Jamie continues to go to a job they don't like because it pays well.

Strategies to consider:

- Teach “Can I have?”

- First this, then you can have…

- Not now, but …

- Not this, but …

Functions of Behavior -- Escape or Avoid

"i don't want something".

Get me out of here; Stop that, I don’t like it; I’m not doing that.

Escape = getting away from something the student doesn’t like

Avoidance = getting away from something the student doesn’t like BEFORE it actually happens

Examples: Jacob is shopping with mom. Mom wants Jacob to walk. Jacob pulls on mom’s hand and then sits down on the floor. Mom picks him up and puts him in the cart.

Janie crosses her arms and slumps in chair during math time.

Jude runs to the corner when his OT comes to get him.

Jamie doesn't take their boyfriend's call after a big fight.

Strategies to consider:

- Teach “I don't want” or “I need a break”

- Do this much, then break

- I know, but we need to because…

- Let's find something different to do

Functions of Behavior -- Attention or Connection

"i need someone".

I need your attention and I’ll get it if it’s positive or negative. I am lacking positive connections in my life, so I will engage in a behavior to try to fill that void.

It is common for challenging behavior to occur for attention if we are only paying attention when students are behaving “correctly.”

Examples : Jacob is shopping with mom. Mom is concentrating on her list. Jacob begins to cry and pull on mom. Mom turns to Jacob and kisses on his face. Jacob stops crying.

Janie makes farting noises in class, and the other students laugh.

Jude breaks his pencil everyday. When he does, the teacher always comes over to bring him a new one.

Uh, just about everyone on TikTok. 🙂

- Teach “Can I have a minute/chat?”

- First this, then we can…

- We can … [when], and I'm so excited to spend that time with you then!

- Opportunities to “shine”

Functions of Behavior -- Sensory or Automatic

"i have an internal need".

I have an internal need that needs to be met.

In this case, reinforcement is not environmental or delivered by another person, it is internal, a physical consequence for the individual. We all have these!

- Scratching a bug bite

- Reading a book

- Eating good food

The most common in autism include repetitive motor movements (e.g., toe walking, flapping, body rocking, humming, pacing), perseverative thoughts, actions, and verbals (e.g., talking about the same subject, making same noises), visual stimulations (e.g., string flicking, staring at lights, turning things on/off to see them, and restricted food preferences.

***A note here about self-stimulatory behavior (or “stimming”). There is NOTHING wrong with stimming! It's often a way for someone to self-regulate or reduce anxiety. As long as it's not dangerous or impeding (significantly) someone's learning or the learning of others, it's all good! Let the person regulate themself. 🙂

Examples : Jacob is shopping with mom. Jacob sees a candy bar. Jacob picks up the candy bar and flicks the paper in front of his eyes. Mom can’t get him to leave it alone and eventually gives Jacob the candy bar, and he continues to play with the paper.

Janie covers her ears when walking into class every day.

Jude cries for no known reason but appears to be holding his tummy.

Jamie isn't able to maintain a personal relationship because they can't kick their addiction to porn.

- Teach “I need …”

- Teach when and where

- Teach/provide alternatives that meets same need

Multi-faceted

While we try to find “the” function of a behavior when we're looking to change it, it's almost never that simple, is it? Behaviors can be complex and intricate.

The most common dual-function I have observed in my career is a behavior that is triggered by the need to escape or avoid something, and then maintained by the attention the behavior has evoked in others. So a student may start ripping paper and breaking pencils in class because they don't want to do the math, but then the students are watching, and when the teacher has to step in, the student is also getting all that attention for the behavior! Makes it tricky to address!

In the end, we just have to do our best to get to know our students, build solid relationships with them, set up an environment for their success, and then do our best to address the primary function. In the case of the math, we can make sure the NEXT time we provide supports and reinforcement opportunities to the student beforehand with the intention to prevent the need to express their displeasure by taking it out on the paper and pencils in the first place.

Find Function-Based Social Stories here:

Sign up for the newsletter to get weekly freebies and more, check us out on teacherspayteacher.com.

Share this post on:

Connect with me on Instagram

CONNECT WITH ME

Get free resources.

Sign up for the newsletter and get weekly tips, tricks, freebies and more!

Recent Posts

- 5 Reasons to Use Daily Behavior Charts and Positive Reinforcement Systems in a Behavior Classroom

- 5 Tips to Make an IEP Meeting Run Smoothly

- How to Improve Communication with Families Through Daily Reports in Special Education

- Creating Task Analysis Visuals: The Key to Independence in Life Skills Classrooms

- Potty Training Tips for Children with Autism: You’re not Alone!

QUICK LINKS

© 2022 aba in school – all rights reserved – privacy policy – terms and conditions – designed by kelsey romine

The Four Functions of Behavior Explained

There is a certain image that comes to mind when thinking of a child with autism who exhibits severe problem behavior. It conjures images of physical aggression, screaming, spitting, scratching and a child unwilling to budge an inch. Many people have seen parents in public places, such as supermarkets or restaurants, attempt to reason with a child in the middle of a tantrum. From the outside looking in, it may appear as though the child is behaving irrationally. It is likely though, that this behavior has a very specific and rational purpose. In other words, there is a function to this behavior.

In the case of a child with autism having a tantrum in a supermarket, the function is likely access to a toy or candy that the child desires to obtain. In the case of a child screaming in a restaurant, the function could be to escape to a more desirable location or activity. For a child in a special education class constantly interrupting the teacher while they are trying to deliver the lesson, it could be the individual attention that these outbursts achieve from the teacher or other students in the class. It could also be the case that this behavior provides its own reward, such as with hand flapping or repetitive loud vocalizations. Understanding the function of a behavior is crucial if a parent or teacher wishes to find a permanent solution.

With that in mind, here are the four main functions of behavior explained:

Access to Tangible Items

Achieving access to a desired toy or food is a common function of problem behaviors in children with or without autism. In the case of the child having a tantrum in the middle of a supermarket, it may be instructive to watch how the situation resolves itself. Often, it will end with the parent giving in and buying the toy or candy that provoked the tantrum in the first place. The next time the family is in the supermarket, can you guess what will happen if the child is denied a toy? The child is simply using the easiest and most effective method to obtain the object of their desire. To put it into perspective, access to tangible items is the reason most of us get out of bed and drive to work in the morning. The tangible item may be different (paying the rent, buying groceries, paying for children's tuition) but the function is the same.

There are a couple of critically important steps if a parent or teacher wishes to eliminate problem behaviors such as physical aggression, that occur with the goal of achieving tangible items. First, the behavior needs to stop resulting in the delivery of the tangible item. If this item is a toy, that toy cannot be delivered during or immediately after the problem behavior. Second, a replacement behavior needs to be taught. Generally, this will be some form of communication. If fully vocal, teach the child to ask nicely for the object. If the child is lower functioning, sign language or a picture exchange system may be more appropriate. Third, offer an alternative route to the object of desire, if possible. For instance, have the child earn a pre-determined amount of tokens before they can have the tangible item. These tokens could be earned by doing chores, completing class assignments, or simply not engaging in tantrums for a period of time.

Escape is another common function of behavior. In a typically functioning adult's life, this could take the form of doing the dishes to avoid making an unpleasant phone call. For a child with a developmental disability, it could take the form of physical aggression or running away. Simply getting to avoid the undesirable activity provides the reward for this behavior. Unfortunately for a parent or a teacher, the child's desire to avoid the activity may be in direct conflict with the parent's desire to have a pleasant meal at a restaurant or a teacher's desire to have their student work quietly on their assignment.

The most effective way to reduce escape-maintained problem behavior is to prevent the behavior from allowing the child to escape. This could take the form of moving the child into an area of the class where they cannot disrupt the other students but requiring them to still complete the assignment that provoked the behavior. In situations where the problem behavior is severe, such as with physical aggression or self-injurious behavior, this may be more difficult or impossible. In those situations, stopping the dangerous behavior should be the first priority. This usually will mean blocking the child as gently as possible to prevent them from harming themselves or others. In all cases of escape-maintained behavior, a replacement behavior should be taught to the child as soon as possible. This could mean teaching the child to appropriately communicate their desire to avoid the activity in question. Once they can effectively do this, they should be allowed to escape the behavior initially. Over time, though, there should be a plan put in place to reduce the amount of time that an appropriate request to avoid an activity will allow the child to escape. Reinforcement (or reward) should also be provided for successful completion of the activity.

Attention is one of the more interesting functions of behavior. That is because it doesn't always matter whether the attention achieved is positive or negative. Yelling at a child may be just as desirable to them as praise. When a teacher yells at a disruptive student to be quiet and get to work, they may be providing the child the very thing that they want most. While the teacher thinks they are punishing the child, they could actually be making the problem behavior more likely to occur again in the future. Think about people on the internet making offensive comments on message boards or social networking sites. Do they stop when another commenter tells them they are being offensive and to knock it off? Often, it will just elicit more comments from the person. The form of the attention doesn't matter as much as the fact that it is attention.

As with the behavior functions of access to tangible items and escape, the most important thing to remember about reducing attention-seeking behavior is making sure it stops resulting in any form of attention. This could involve isolating a disruptive student in another part of the class or encouraging the other students not to provide attention to the student's outbursts. In addition, provide positive outlets for this student to achieve the attention they desire. This could involve rewarding them with time at the end of class to make funny sounds or jokes to the class, provided they behave appropriately for the lessons taught during class.

Sometimes behavior provides its own reward. When a person with developmental disabilities makes repetitive movements with their hands or repeats sounds over and over, there may be no function beyond the pleasure that the behavior itself provides. These are said to be automatically reinforcing behaviors. These behaviors can sometimes be severe, like when a child repeatedly bites their hand to the point where it is breaking the skin. They can also be fairly minor, such as a person twirling their hair or repetitively tapping their shoe.

Behaviors with an automatic function can be some of the more difficult behaviors to intervene on. That is because it is very difficult to eliminate the reward for a behavior, when the reward occurs at the same time that the behavior does. There are, however, some methods that can be successful. One, a replacement behavior can sometimes be taught. For instance, if a child bites down on their hand during class, a nontoxic toy could be provided to them to bite down on that would allow them the same sensation, but without causing their hand to be damaged. Two, the behavior can be blocked from occurring. If a child hits a wall repeatedly with their hand, they can be simply moved away from the wall so they cannot reach it. Third, the behavior can be made less rewarding. In the case of the child that bites down on their hand, a bad tasting spray could be applied to their hand that would make biting down on it less pleasurable. It is important to remember, though, that with severe behaviors like these, a behavioral specialist should be consulted before beginning any intervention.

RELATED - Four Terms for Translating Behavioral Jargon

- Recent Posts

- The Four Functions of Behavior Explained - February 20, 2018

- 4 Terms for Translating Behavioral Jargon - July 26, 2017

Topics & Categories

- Teacher Daily

- Creative Teacher

- Froogle Teacher

- Language Arts

- Teacher Talk

Degree Programs

- Associate’s Degree

- Bachelor’s Degree

- Master’s Degree

- Doctorate PhD/EdD Degree

- View All Degree Programs

Teacher Resources

- Online Teaching Degrees

- How to Become a Teacher

- Teaching Careers

- Lesson Plans For Teachers

- Teaching Scholarships & Grants

- Best Teacher Discounts

- Teacher Tools and Resources

- Our Mission

What Is Education For?

Read an excerpt from a new book by Sir Ken Robinson and Kate Robinson, which calls for redesigning education for the future.

What is education for? As it happens, people differ sharply on this question. It is what is known as an “essentially contested concept.” Like “democracy” and “justice,” “education” means different things to different people. Various factors can contribute to a person’s understanding of the purpose of education, including their background and circumstances. It is also inflected by how they view related issues such as ethnicity, gender, and social class. Still, not having an agreed-upon definition of education doesn’t mean we can’t discuss it or do anything about it.

We just need to be clear on terms. There are a few terms that are often confused or used interchangeably—“learning,” “education,” “training,” and “school”—but there are important differences between them. Learning is the process of acquiring new skills and understanding. Education is an organized system of learning. Training is a type of education that is focused on learning specific skills. A school is a community of learners: a group that comes together to learn with and from each other. It is vital that we differentiate these terms: children love to learn, they do it naturally; many have a hard time with education, and some have big problems with school.

There are many assumptions of compulsory education. One is that young people need to know, understand, and be able to do certain things that they most likely would not if they were left to their own devices. What these things are and how best to ensure students learn them are complicated and often controversial issues. Another assumption is that compulsory education is a preparation for what will come afterward, like getting a good job or going on to higher education.

So, what does it mean to be educated now? Well, I believe that education should expand our consciousness, capabilities, sensitivities, and cultural understanding. It should enlarge our worldview. As we all live in two worlds—the world within you that exists only because you do, and the world around you—the core purpose of education is to enable students to understand both worlds. In today’s climate, there is also a new and urgent challenge: to provide forms of education that engage young people with the global-economic issues of environmental well-being.

This core purpose of education can be broken down into four basic purposes.

Education should enable young people to engage with the world within them as well as the world around them. In Western cultures, there is a firm distinction between the two worlds, between thinking and feeling, objectivity and subjectivity. This distinction is misguided. There is a deep correlation between our experience of the world around us and how we feel. As we explored in the previous chapters, all individuals have unique strengths and weaknesses, outlooks and personalities. Students do not come in standard physical shapes, nor do their abilities and personalities. They all have their own aptitudes and dispositions and different ways of understanding things. Education is therefore deeply personal. It is about cultivating the minds and hearts of living people. Engaging them as individuals is at the heart of raising achievement.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights emphasizes that “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights,” and that “Education shall be directed to the full development of the human personality and to the strengthening of respect for human rights and fundamental freedoms.” Many of the deepest problems in current systems of education result from losing sight of this basic principle.

Schools should enable students to understand their own cultures and to respect the diversity of others. There are various definitions of culture, but in this context the most appropriate is “the values and forms of behavior that characterize different social groups.” To put it more bluntly, it is “the way we do things around here.” Education is one of the ways that communities pass on their values from one generation to the next. For some, education is a way of preserving a culture against outside influences. For others, it is a way of promoting cultural tolerance. As the world becomes more crowded and connected, it is becoming more complex culturally. Living respectfully with diversity is not just an ethical choice, it is a practical imperative.

There should be three cultural priorities for schools: to help students understand their own cultures, to understand other cultures, and to promote a sense of cultural tolerance and coexistence. The lives of all communities can be hugely enriched by celebrating their own cultures and the practices and traditions of other cultures.

Education should enable students to become economically responsible and independent. This is one of the reasons governments take such a keen interest in education: they know that an educated workforce is essential to creating economic prosperity. Leaders of the Industrial Revolution knew that education was critical to creating the types of workforce they required, too. But the world of work has changed so profoundly since then, and continues to do so at an ever-quickening pace. We know that many of the jobs of previous decades are disappearing and being rapidly replaced by contemporary counterparts. It is almost impossible to predict the direction of advancing technologies, and where they will take us.

How can schools prepare students to navigate this ever-changing economic landscape? They must connect students with their unique talents and interests, dissolve the division between academic and vocational programs, and foster practical partnerships between schools and the world of work, so that young people can experience working environments as part of their education, not simply when it is time for them to enter the labor market.

Education should enable young people to become active and compassionate citizens. We live in densely woven social systems. The benefits we derive from them depend on our working together to sustain them. The empowerment of individuals has to be balanced by practicing the values and responsibilities of collective life, and of democracy in particular. Our freedoms in democratic societies are not automatic. They come from centuries of struggle against tyranny and autocracy and those who foment sectarianism, hatred, and fear. Those struggles are far from over. As John Dewey observed, “Democracy has to be born anew every generation, and education is its midwife.”

For a democratic society to function, it depends upon the majority of its people to be active within the democratic process. In many democracies, this is increasingly not the case. Schools should engage students in becoming active, and proactive, democratic participants. An academic civics course will scratch the surface, but to nurture a deeply rooted respect for democracy, it is essential to give young people real-life democratic experiences long before they come of age to vote.

Eight Core Competencies

The conventional curriculum is based on a collection of separate subjects. These are prioritized according to beliefs around the limited understanding of intelligence we discussed in the previous chapter, as well as what is deemed to be important later in life. The idea of “subjects” suggests that each subject, whether mathematics, science, art, or language, stands completely separate from all the other subjects. This is problematic. Mathematics, for example, is not defined only by propositional knowledge; it is a combination of types of knowledge, including concepts, processes, and methods as well as propositional knowledge. This is also true of science, art, and languages, and of all other subjects. It is therefore much more useful to focus on the concept of disciplines rather than subjects.

Disciplines are fluid; they constantly merge and collaborate. In focusing on disciplines rather than subjects we can also explore the concept of interdisciplinary learning. This is a much more holistic approach that mirrors real life more closely—it is rare that activities outside of school are as clearly segregated as conventional curriculums suggest. A journalist writing an article, for example, must be able to call upon skills of conversation, deductive reasoning, literacy, and social sciences. A surgeon must understand the academic concept of the patient’s condition, as well as the practical application of the appropriate procedure. At least, we would certainly hope this is the case should we find ourselves being wheeled into surgery.

The concept of disciplines brings us to a better starting point when planning the curriculum, which is to ask what students should know and be able to do as a result of their education. The four purposes above suggest eight core competencies that, if properly integrated into education, will equip students who leave school to engage in the economic, cultural, social, and personal challenges they will inevitably face in their lives. These competencies are curiosity, creativity, criticism, communication, collaboration, compassion, composure, and citizenship. Rather than be triggered by age, they should be interwoven from the beginning of a student’s educational journey and nurtured throughout.

From Imagine If: Creating a Future for Us All by Sir Ken Robinson, Ph.D and Kate Robinson, published by Penguin Books, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2022 by the Estate of Sir Kenneth Robinson and Kate Robinson.

COMMENTS

Understanding behavior functions allows educators and therapists to implement effective strategies like positive reinforcement and behavior contracts, tailoring interventions to meet specific needs and enhance behavior management.

Behavior analysts often categorize behavior into four primary functions: escape/avoidance, attention-seeking, access to tangible items, and automatic reinforcement. These functions provide a framework for understanding why individuals engage in specific behaviors.

Discover the four essential functions of behavior—attention, escape, access to tangibles, and sensory stimulation—and learn how they drive human actions.

Learning the four functions of behavior will help you to understand a child’s motivation behind actions or behaviors within the classroom. Plus, grasping both positive and negative reinforcement will paint the full picture of why a child is acting a certain way.

Figuring out the function of, or the reasons behind, a behavior is critical for finding an appropriate response or support. Knowing the function can also help you find ways to prevent behavior issues in the future.

Learning Objectives. List the major functions of education. Explain the problems that conflict theory sees in education. Describe how symbolic interactionism understands education. The major sociological perspectives on education fall nicely into the functional, conflict, and symbolic interactionist approaches (Ballantine & Hammack, 2009).

What are the four functions of behavior including access, escape, attention, and sensory. What they mean in ABA and special education and how to address them.

Understanding the function of a behavior is crucial if a parent or teacher wishes to find a permanent solution. With that in mind, here are the four main functions of behavior explained: Access to Tangible Items

Education is one of the ways that communities pass on their values from one generation to the next. For some, education is a way of preserving a culture against outside influences. For others, it is a way of promoting cultural tolerance.

Explore the 4 Functions of Behavior and how they impact student's actions in the classroom along with interventions you can use for each one. While not specific to special education, the four functions of behavior are often discussed and used as the basis for intervention strategies.