COPD Case Study: Patient Diagnosis and Treatment (2024)

by John Landry, BS, RRT | Updated: Oct 15, 2024

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a progressive lung condition affecting millions worldwide, primarily linked to smoking. It is marked by a persistent reduction in airflow that gradually worsens, making it increasingly difficult to breathe.

Common symptoms of COPD include chronic coughing, wheezing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness, all of which can severely affect an individual’s daily life and overall well-being .

This case study explores the diagnosis and treatment of an adult patient presenting with classic signs and symptoms of COPD, providing insight into effective management strategies for this challenging condition.

25+ RRT Cheat Sheets and Quizzes

Get instant access to 25+ premium quizzes, mini-courses, and downloadable cheat sheets for FREE.

COPD Clinical Scenario

A 56-year-old male presents to the ER with increased work of breathing. He reported feeling mildly short of breath upon waking, which worsened significantly after climbing several flights of stairs. Upon arrival, the patient was unable to speak in full sentences due to severe dyspnea. His wife, accompanying him, disclosed that he has a history of liver failure, is allergic to penicillin, and has a 15-pack-year smoking history. She also mentioned that he works as a cabinet maker, frequently exposed to fine dust and debris in his workplace.

Physical Findings

- Pupils equal and reactive to light

- Alert and oriented

- Breathing through pursed lips

- Trachea midline, no jugular venous distention

Vital Signs

- Heart rate: 92 beats/min

- Respiratory rate: 22 breaths/min

Chest Assessment

- Increased anterior-posterior chest diameter (barrel chest)

- Bilateral chest expansion present

- Prolonged expiratory phase with diminished breath sounds upon auscultation

- Subcostal retractions observed

- No tactile fremitus on chest palpation

- Chest percussion reveals increased resonance

- Abdomen soft and non-tender

- No distention

Extremities

- Capillary refill time: 2 seconds

- Digital clubbing observed in fingertips

- No pedal edema

- Skin appears jaundiced

ABG Results

- PaCO2: 59 mmHg

- HCO3: 30 mEq/L

- PaO2: 64 mmHg

Chest X-ray

- Flattened diaphragm

- Increased retrosternal air space

- Dark lung fields

- Slight right ventricular hypertrophy

- Narrow heart silhouette

- RBC: 6.5 million/mm³

- Hb: 19 g/dL

Based on the clinical presentation, lab results, and radiology findings, the patient is highly likely to have chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Key indicators supporting this diagnosis include:

- Barrel-shaped chest

- Tachypnea with prolonged expiratory time

- Diminished breath sounds

- Use of accessory muscles during breathing

- Digital clubbing

- Pursed-lip breathing

- History of significant smoking exposure

- Occupational exposure to dust

Note: These findings are consistent with advanced COPD, requiring immediate intervention to manage symptoms and prevent further progression.

The primary goal of initial treatment for this patient is to correct hypoxemia while minimizing the risk of oxygen-induced hypercapnia, a concern in patients with COPD. The use of low-flow oxygen is recommended to carefully manage oxygen levels.

It’s acceptable to begin with a nasal cannula at 1–2 L/min, but it’s often more precise to use an air-entrainment mask for COPD patients, as it delivers an exact FiO2.

Regardless of the method, oxygen therapy should always start with the lowest possible FiO2 that maintains adequate oxygenation, adjusting as needed based on the patient’s response.

Example Scenario

Suppose you initiate oxygen therapy with an FiO2 of 28% using an air-entrainment mask, but after no improvement, you increase it to 32%. Initially, the patient’s SpO2 was 84%, but it has now dropped to 80%, with worsening retractions. The patient remains in a tripod position, showing signs of increased respiratory effort, including pursed-lip breathing. A repeat arterial blood gas (ABG) reveals a PaCO2 of 65 mmHg and a PaO2 of 59 mmHg.

Recommended Next Steps

The patient is exhibiting increasing signs of respiratory distress, with a rising PaCO2 and worsening hypoxemia despite supplemental oxygen. These ABG results confirm that the patient requires additional support for both ventilation and oxygenation .

Although mechanical ventilation is generally avoided in COPD patients due to the difficulty of weaning them off, noninvasive ventilation (NIV) , such as BiPAP, is the most appropriate intervention at this point.

BiPAP provides ventilatory assistance while avoiding the need for intubation , helping to improve both oxygenation and carbon dioxide removal.

Note: By applying noninvasive ventilation, you can reduce the patient’s work of breathing, improve gas exchange, and hopefully prevent further deterioration without the complications associated with mechanical ventilation.

Initial BiPAP Settings

For adult patients, the most commonly recommended initial BiPAP settings are as follows:

- IPAP (Inspiratory Positive Airway Pressure): 8–12 cmH2O

- EPAP (Expiratory Positive Airway Pressure): 5–8 cmH2O

- Rate: 10–12 breaths per minute

- FiO2: Based on the patient’s previous oxygen requirements

For instance, in this case, you could initiate BiPAP with the following settings:

- IPAP: 10 cmH2O

- EPAP: 5 cmH2O

- Rate: 12 breaths/min

- FiO2: 32%, matching the previous oxygen level.

Adjusting BiPAP Based on ABG Results

After 30 minutes on BiPAP, an arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis shows acute respiratory acidosis with mild hypoxemia.

This indicates two issues:

- Elevated PaCO2 (carbon dioxide retention)

- Decreased PaO2 (low oxygen levels)

Recommended BiPAP Adjustments

Improving oxygenation.

To increase the patient’s PaO2, you can adjust either the FiO2 or EPAP. Since EPAP functions like PEEP (positive end-expiratory pressure), increasing it will improve oxygenation by preventing alveolar collapse.

Recommendation: Increase the EPAP from 5 cmH2O to 7 cmH2O, which will help boost oxygenation.

Since EPAP and IPAP together determine pressure support (the difference between them), increasing EPAP without changing IPAP will reduce the pressure support, which could affect ventilation.

To maintain the same pressure support, it’s important to increase IPAP by the same amount as EPAP.

Improving Ventilation

To address the high PaCO2, the focus should be on increasing IPAP. This will enhance the patient’s tidal volume and, in turn, help to blow off more CO2.

Recommendation: Increase the IPAP to 14 cmH2O. This adjustment will improve ventilation, allowing the patient to exhale more CO2 and bring the PaCO2 down.

Final BiPAP Settings After Adjustment:

- IPAP: 14 cmH2O

- EPAP: 7 cmH2O

After making these changes, reassess the patient’s condition . In this scenario, the patient’s ABG and clinical signs should improve, indicating more effective ventilation and oxygenation.

Patient Outcome and Discharge

Two days later, the patient’s condition has improved significantly, and they have successfully been weaned off BiPAP.

Their oxygenation has stabilized, and they no longer require supplemental oxygen. The patient is now ready for discharge.

Home Therapy and Treatment Recommendations

For patients with COPD, home oxygen therapy may be recommended if their PaO2 falls below 55 mmHg or if their SpO2 drops below 88% on more than two occasions within a three-week period.

However, it’s essential to take a conservative approach when administering oxygen therapy to COPD patients to avoid oxygen-induced hypercapnia.

Pharmacological Recommendations

The following pharmacological agents can be considered for long-term management of COPD:

- Short-acting bronchodilators (e.g., Albuterol): Useful for quick relief of acute symptoms.

- Long-acting bronchodilators (e.g., Formoterol): Help maintain airway patency over time, reducing the frequency of exacerbations.

- Anticholinergic agents (e.g., Ipratropium bromide): These provide sustained bronchodilation, especially useful in combination with bronchodilators.

- Inhaled corticosteroids (e.g., Budesonide): Help reduce airway inflammation and decrease the frequency of flare-ups.

- Methylxanthine agents (e.g., Theophylline): Can be used in cases where other therapies are insufficient, though close monitoring is needed due to potential side effects.

Additional Recommendations

- Smoking cessation support : For patients who smoke, quitting is critical. Smoking cessation programs and nicotine replacement therapy can be very effective.

- Bronchial hygiene therapy : To help with secretion clearance, recommend therapies such as positive expiratory pressure (PEP) therapy or other airway clearance techniques.

- Physical activity and diet: Encourage the patient to stay active, as regular exercise improves lung function and overall health. A balanced, healthy diet can also support their recovery and energy levels.

- Infection prevention: Stress the importance of avoiding infections, particularly respiratory infections. The patient should get an annual flu vaccine and possibly a pneumonia vaccine.

- Cardiopulmonary rehabilitation : Some patients may benefit from a structured rehabilitation program that includes supervised exercise and education to improve breathing techniques and physical endurance.

Note: By incorporating these home therapies and lifestyle modifications, the patient’s COPD can be better managed, helping to prevent exacerbations and significantly improve their quality of life.

Final Thoughts

When treating a patient with COPD, there are two essential principles to keep in mind:

- Oxygen management: Always be cautious with the amount of oxygen administered, aiming to keep the FiO2 as low as possible to maintain adequate oxygenation without suppressing the patient’s drive to breathe.

- Noninvasive ventilation preference: Whenever feasible, opt for noninvasive ventilation (e.g., BiPAP) before resorting to intubation and conventional mechanical ventilation. Intubation can lead to prolonged ventilator dependence, making it more challenging to wean COPD patients .

Additionally, as the patient approaches discharge, it’s crucial to ensure they leave with the appropriate medications and home treatments to minimize the risk of readmission.

Proper management at home—including oxygen therapy, bronchodilators , and pulmonary rehabilitation—can greatly improve outcomes. By considering these key points, you can effectively manage COPD and help improve your patient’s quality of life.

Written by:

John Landry is a registered respiratory therapist from Memphis, TN, and has a bachelor's degree in kinesiology. He enjoys using evidence-based research to help others breathe easier and live a healthier life.

- Agarwal AK, Raja A, Brown BD. Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. [Updated 2023 Aug 7]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024.

- Faarc, Kacmarek Robert PhD Rrt, et al. Egan’s Fundamentals of Respiratory Care. 12th ed., Mosby, 2020.

- Rrt, Cairo J. PhD. Pilbeam’s Mechanical Ventilation: Physiological and Clinical Applications. 7th ed., Mosby, 2019.

- Faarc, Gardenhire Douglas EdD Rrt-Nps. Rau’s Respiratory Care Pharmacology. 10th ed., Mosby, 2019.

- Faarc, Heuer Al PhD Mba Rrt Rpft. Wilkins’ Clinical Assessment in Respiratory Care. 8th ed., Mosby, 2017.

- Rrt, Des Terry Jardins MEd, and Burton George Md Facp Fccp Faarc. Clinical Manifestations and Assessment of Respiratory Disease. 8th ed., Mosby, 2019.

Recommended Reading

Epiglottitis scenario: clinical simulation exam (practice problem), guillain barré syndrome case study: clinical simulation scenario, how to prepare for the clinical simulations exam (cse), faqs about the clinical simulation exam (cse), drugs and medications to avoid if you have copd, 7+ mistakes to avoid on the clinical simulation exam (cse), the 50+ diseases to learn for the clinical sims exam (cse).

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Overview

- Theory

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Follow up

- Resources

Case history

Case history #1.

A 66-year-old man with a smoking history of one pack per day for the past 47 years presents with progressive shortness of breath and chronic cough, productive of yellowish sputum, for the past 2 years. On examination he appears cachectic and in moderate respiratory distress, especially after walking to the examination room, and has pursed-lip breathing. His neck veins are mildly distended. Lung examination reveals a barrel chest and poor air entry bilaterally, with moderate inspiratory and expiratory wheezing. Heart and abdominal examination are within normal limits. Lower extremities exhibit scant pitting edema.

Case history #2

A 56-year-old woman with a history of smoking presents to her primary care physician with shortness of breath and cough for several days. Her symptoms began 3 days ago with rhinorrhea. She reports a chronic morning cough productive of white sputum, which has increased over the past 2 days. She has had similar episodes each winter for the past 4 years. She has smoked 1 to 2 packs of cigarettes per day for 40 years and continues to smoke. She denies hemoptysis, chills, or weight loss and has not received any relief from over-the-counter cough preparations.

Other presentations

Some patients report chest tightness, which often follows exertion and may arise from intercostal muscle contraction. Weight loss, muscle loss, and anorexia are common in patients with severe and very severe COPD. [1] Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2024 report. 2024 [internet publication]. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report Other presentations include fatigue, hemoptysis, cyanosis, and morning headaches secondary to hypercapnia. Chest pain and hemoptysis are uncommon symptoms of COPD and raise the possibility of alternative diagnoses. [2] National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in over 16s: diagnosis and management. Jul 2019 [internet publication]. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng115

Physical examination may demonstrate hypoxia, use of accessory muscles, paradoxical rib movements, distant heart sounds, lower-extremity edema and hepatomegaly secondary to cor pulmonale, and asterixis secondary to hypercapnia.

Patients may also present with signs and symptoms of COPD complications. These include severe shortness of breath, severely decreased air entry, and chest pain secondary to an acute COPD exacerbation or spontaneous pneumothorax. [1] Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2024 report. 2024 [internet publication]. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report [3] Garcia-Pachon E. Paradoxical movement of the lateral rib margin (Hoover sign) for detecting obstructive airway disease. Chest. 2002 Aug;122(2):651-5. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12171846?tool=bestpractice.com Patients with COPD often have other comorbidities, including cardiovascular disease, skeletal muscle dysfunction, metabolic syndrome and diabetes, osteoporosis, depression, anxiety, lung cancer, gastroesophageal reflux disease, bronchiectasis, obstructive sleep apnea, and cognitive impairment. [1] Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: 2024 report. 2024 [internet publication]. https://goldcopd.org/2024-gold-report [4] Morgan AD, Rothnie KJ, Bhaskaran K, et al. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk of 12 cardiovascular diseases: a population-based study using UK primary care data. Thorax. 2018 Sep;73(9):877-9. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29438071?tool=bestpractice.com [5] Maltais F, Decramer M, Casaburi R, et al; ATS/ERS Ad Hoc Committee on Limb Muscle Dysfunction in COPD. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update on limb muscle dysfunction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014 May 1;189(9):e15-62. https://www.atsjournals.org/doi/10.1164/rccm.201402-0373ST http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24787074?tool=bestpractice.com

One UK study found that 14.5% of patients with COPD had a concomitant diagnosis of asthma, whereas a global meta-analysis estimated the pooled prevalence of asthma in patients with COPD to be 29.6% (range: 12.6% to 55.5%). [6] Nissen F, Morales DR, Mullerova H, et al. Concomitant diagnosis of asthma and COPD: a quantitative study in UK primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2018 Nov;68(676):e775-82. https://bjgp.org/content/68/676/e775 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30249612?tool=bestpractice.com [7] Hosseini M, Almasi-Hashiani A, Sepidarkish M, et al. Global prevalence of asthma-COPD overlap (ACO) in the general population: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Res. 2019 Oct 23;20(1):229. https://respiratory-research.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12931-019-1198-4 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/31647021?tool=bestpractice.com

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer

Log in or subscribe to access all of BMJ Best Practice

Log in to access all of bmj best practice, help us improve bmj best practice.

Please complete all fields.

I have some feedback on:

We will respond to all feedback.

For any urgent enquiries please contact our customer services team who are ready to help with any problems.

Phone: +44 (0) 207 111 1105

Email: [email protected]

Your feedback has been submitted successfully.

LOGIN

Annual Report

- Board of Directors

- Nomination Process

- Organizational Structure

- ATS Policies

- ATS Website

- MyATS Tutorial

- ATS Experts

- Press Releases

Member Newsletters

- ATS in the News

- ATS Conference News

- Embargo Policy

ATS Social Media

Breathe easy podcasts, ethics & coi, health equity, industry resources.

- Value of Collaboration

- Corporate Members

- Advertising Opportunities

- Clinical Trials

- Financial Disclosure

In Memoriam

Global health.

- International Trainee Scholarships (ITS)

- MECOR Program

- Forum of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS)

- 2019 Latin American Critical Care Conference

Peer Organizations

Careers at ats, affordable care act, ats comments and testimony, forum of international respiratory societies, tobacco control, tuberculosis, washington letter.

- Clinical Resources

- ATS Quick Hits

- Asthma Center

Best of ATS Video Lecture Series

- Coronavirus

- Critical Care

- Disaster Related Resources

- Disease Related Resources

- Resources for Patients

- Resources for Practices

- Vaccine Resource Center

- Career Development

- Resident & Medical Students

- Junior Faculty

- Training Program Directors

- ATS Reading List

- ATS Scholarships

- ATS Virtual Network

ATS Podcasts

- ATS Webinars

- Professional Accreditation

Pulmonary Function Testing (PFT)

- Calendar of Events

Patient Resources

- Asthma Today

- Breathing in America

- Fact Sheets: A-Z

- Fact Sheets: Topic Specific

- Patient Videos

- Other Patient Resources

Lung Disease Week

Public advisory roundtable.

- PAR Publications

- PAR at the ATS Conference

Assemblies & Sections

- Abstract Scholarships

- ATS Mentoring Programs

- ATS Official Documents

- ATS Interest Groups

- Genetics and Genomics

- Medical Education

- Terrorism and Inhalation Disasters

- Allergy, Immunology & Inflammation

- Behavioral Science and Health Services Research

- Clinical Problems

- Environmental, Occupational & Population Health

- Pulmonary Circulation

- Pulmonary Infections and Tuberculosis

- Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Respiratory Cell & Molecular Biology

- Respiratory Structure & Function

- Sleep & Respiratory Neurobiology

- Thoracic Oncology

- Joint ATS/CHEST Clinical Practice Committee

- Clinicians Advisory

- Council of Chapter Representatives

- Documents Development and Implementation

- Drug/Device Discovery and Development

- Environmental Health Policy

- Ethics and Conflict of Interest

- Health Equity and Diversity Committee

- Health Policy

- International Conference Committee

- International Health

- Members In Transition and Training

- View more...

- Membership Benefits

- Categories & Fees

- Special Membership Programs

- Renew Your Membership

- Update Your Profile

- ATS DocMatter Community

- Respiratory Medicine Book Series

- Elizabeth A. Rich, MD Award

- Member Directory

- ATS Career Center

- Welcome Trainees

- ATS Wellness

- Thoracic Society Chapters

- Chapter Publications

- CME Sponsorship

Corporate Membership

Clinical cases, professionals.

- Respiratory Health Awards

- Clinicians Chat

- Ethics and COI

- Pulmonary Function Testing

- ATS Resources

The ATS Clinical Cases are a series of cases devoted to interactive clinical case presentations on all aspects of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine. They are designed to provide education to practitioners, faculty, fellows, residents, and medical students in the areas of pulmonary, critical care and sleep medicine.

Currently, we are not accepting new cases for this series, as there are several other venues for publishing cases. For cases that can be written as brief, image-based quesitons, consider submitting them as to Quick Hits . For other cases, please contact your assembly web director regarding other opportunities to publish or highlight cases.

ATS Clinical Cases Designated by the Assemblies

Assembly on Allergy, Immunology, and Inflammation

- A Case Of Diffuse Miliary Pulmonary Infiltrates In A 35 Year-Old Man

- The Mighty Eosinophil

- Persistent Dyspnea in a Patient with Down’s Syndrome

- A 20 Year-Old with a Mediastinal Mass

- A Transsexual with Acute Dyspnea and Diffuse Infiltrates

- Use of Endobronchial Ultrasound to Diagnose an Incidental Lung Nodule

- Persistent Dyspnea Despite Maximal Medical Therapy in COPD

- Uncontrolled asthma, recurrent rhinosinusitis, and infertility in a young woman

- A case of progressive dyspnea and abnormal chest x-ray

- A 27 year old with a non resolving cavitary lung lesion

- ARDS Following Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Multiple Myeloma

- Sudden Onset of Wheezing at Work

- Difficult-to-Control Asthma in a 49-Year-Old Man

- Dyspnea and wheezing in a pregnant patient

- Mediastinal Lymphadenopathy and Interstitial Lung Disease in a Cancer Patient

- Diffuse Infiltrates Following Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation

- Difficult-to-control asthma in 13-year-old boy

- Stable Mild Persistent Asthma in a Young Adult

- Dyspnea in a college athlete

Assembly on Behavioral Science and Health Services Research

- Challenges in Caring for the Child with Asthma: Enlisting Community Services

- A 60-Year-Old Man with Acute Respiratory Failure and Mental Status Changes

- Young Man with Recent Onset Hypertension and Acute Onset Dyspnea

- Hoarseness and Hemoptysis in a 28-Year-Old Pregnant Woman

Assembly on Critical Care

- 60-Year-Old Man with Non-resolving Pneumonia

- Egg Shell Calcifications in a 69 Year Old Woman

- Cavitating Lung Lesion in a 59 year-old man.

- Intracerebral Hemorrhage in a Young Adult Male Patient

- A 39 Year Old Woman with Fever and Myalgia

- Septic Shock Following an Ulcerative Colitis Flare

- A 67-Year-Old Man with Massive Hemoptysis

- Chest Pain After Sexual Intercourse

- Liver dysfunction and severe lactic acidosis in a previously healthy man

Assembly on Clinical Problems

- Clinical Considerations for Individuals with Cystic Fibrosis

- An Unusual Cause of Chest Pain

- A 5 year old girl with Prader-Willi syndrome and worsening snoring during growth hormone therapy

- Dry Cough and Clubbing in a 45-Year-Old Woman

- Near-Complete Opacification of the Right Hemithorax

- Sudden Onset Chest Pain in a Young Man

- Intrapulmonary Shunting Through Tumor Causing Refractory Hypoxemia

Assembly on Environmental, Occupational and Population Health

- Progressive Dyspnea in an Appalachian Coal Miner

- Workplace Spirometry: Early Detection Benefits Individuals, Worker Groups and Employers

- “Horse play and the Lung” – a possible cobalt effect?

- Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonitis or Hypersensitivity Pneumonitis?

Assembly on Microbiology, Tuberculosis and Pulmonary Infections

- Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Secondary to an Unusual Infection

- A Pregnant Woman with Fever and Respiratory Failure

- Cavitating Lung Lesion and Recurrent Chest Infections

- Bronchiectasis and recurrent pulmonary infections

Assembly on Pediatrics

- A six year-old child with cough and facial swelling

Assembly on Pulmonary Circulation

- A Cystic Fibrosis Patient with Hemoptysis From an Unusual Cause

- A 57 Year Old Woman with Pulmonary Hypertension Suffering Worsening Dyspnea on Endothelin Receptor Antagonist Therapy

- 70- Year-Old Woman with Progressive Dyspnea and Dilated Pulmonary Arteries

- An 18-year-old woman with severe dyspnea, hypoxia and abnormal chest findings

Assembly on Pulmonary Rehabilitation

- Pre- and Postoperative Pulmonary Rehabilitation for a COPD Patient Undergoing Bilateral Lung Transplant

Assembly on Sleep and Respiratory Neurobiology

- Central Hypersomnolence: History is the Key

- Persistent Sleepiness in Obstructive Sleep Apnea

- A case of Sleep Disordered Breathing after Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery.

- Postoperative Respiratory Failure in a Child — A Diagnostic Dilemma

- A Case of “Complex” Sleep Apnea?

- Hypersomnolent, Hypercapnic, and Morbidly Obese

- Sleepy Since Adolescence

The American Thoracic Society improves global health by advancing research, patient care, and public health in pulmonary disease, critical illness, and sleep disorders. Founded in 1905 to combat TB, the ATS has grown to tackle asthma, COPD, lung cancer, sepsis, acute respiratory distress, and sleep apnea, among other diseases.

AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY 25 Broadway New York, NY 10004 United States of America Phone: +1 (212) 315-8600 Fax: +1 (212) 315-6498 Email: [email protected]

Privacy Statement | Term of Use | COI Conference Code of Conduct

Clinical Simulation Exam Scenario: COPD Patient Case Study

Here is a case study for students and medical practitioners aimed at providing a clinical simulation exam scenario in patients with COPD.

A COPD case study

The 56-year-old patient presents with a difficulty in breathing. The patient complained of feeling short of breath in the morning upon waking up. The breathlessness became worse after climbing just a few steps. He is too short of breath even while talking and has difficulty in finishing sentences.

His wife has revealed that the patient has a history of hepatic failure and allergy to penicillin. He also has a smoking history of 15 pack-year. His occupation involves building cabinets for which he is constantly required to work around fine dust and debris.

Physical examination

The patient's pupils are equal and reactive and he appears alert and oriented. He also has a pursed-lip pattern of breathing. His trachea is in the midline and there is no jugular venous distension.

The vital parameters of the patient are as follows:

- Heart rate: 92 beats per min

- Respiratory rate: 22 breaths per min

Chest assessment:

- The patient presents with a larger than the normal anterior-posterior (AP) diameter of the chest.

- An equal and bilateral chest expansion is noted.

- The chest auscultation reveals diminished breath sounds and a prolonged expiratory phase

- Palpation does not reveal any tactile fremitus

- Percussion of the chest reveals increased resonance

- Subcostal retractions are need

Per abdomen examination

- The abdomen is soft and tender

- Distension: Not present

Extremities:

- The skin appears to be slightly yellowish

- There is no pitting edema in the legs

- Digital clubbing is noted in the fingertips

Laboratory and radiology findings

- ABG Results: PaCO2 59 mm of Hg, pH 7.35 mm of Hg, PaO2 64 mm of Hg, and HCO3 30 mEq/L

- Chest X-ray: Revealed a flat diaphragm, dark lung fields, increase in the retrosternal space, a narrow heart, and mild hypertrophy of the right ventricle

- Blood tests: Hemoglobin 19 gm per 100 mL, RBC 6.5 mill per m3, and hematocrit value 57%

Based on the medical history of the patient, his symptoms, and physical examination, he is suspected to have Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD).

What are the key findings from the patient’s medical history and assessment in view of the diagnosis?

Here are some important signs and symptoms the patient has complained of that are common in those suffering from COPD:

- A prolonged expiratory time

- Barrel-shaped chest

- Use of accessory muscles of breathing

- Diminished breath sounds

- Pursed lip breathing

- Digital clubbing

- Exposure to dust at the workplace

- History of smoking

How do the abnormal laboratory findings and radiology results justify the diagnosis of COPD in this patient?

The chest x-ray of the patient has revealed the classic signs of COPD such as hyperextension, a narrow heart, and dark lung fields.

It is important to note that though the patient does not have a history of cor pulmonale, congestive heart failure is very common in patients with COPD. Also, the right ventricle of the patient is hypertrophied. It needs to be brought to the attention of the cardiologist for further investigation and assessment of the heart functions.

The laboratory values such as the increased RBC, hematocrit, and hemoglobin levels also point to the diagnosis of COPD. These levels often increase in response to chronic hypoxemia experienced commonly by COPD patients.

The ABG results of the patient also indicate the possibility of COPD as the interpretation suggests compensated respiratory acidosis with hypoxemia. Compensated blood gas levels indicate an issue that could have existed for an extended duration of time.

Which other tests could be helpful in confirming the diagnosis of COPD?

A series of PFT (pulmonary function tests) can be recommended to assess the lung volumes, functions, and capacities of the patient. This would help to confirm or rule out the diagnosis of COPD and provide insights into the severity of the condition.

Generally, the PFT of COPD patients shows the FEV1:FVC ratio to be lower than 70% and an FEV1 value to be less than 80%.

Treatment of COPD

What is the initial treatment for the patient.

As this patient has COPD, the initial line of treatment could be low-flow oxygen to manage hypoxemia. A nasal cannula at 1 to 2 L/min is often recommended along with the air-entrainment mask to ensure the exact FiO2 supply to the lungs.

The patient may be treated with the lowest possible FiO2. The FiO2 can be titrated later based on how he responds to the oxygen being delivered.

What is the next treatment recommendation?

The recent ABG results have revealed a rise in the PaCO2 levels and a decline in the PaO2 levels. This suggests that the patient needs further treatment with ventilation and oxygenation.

Mechanical ventilation needs to be avoided in COPD patients as much as possible as they often have a difficulty in weaning from the device. So, the most appropriate treatment for this patient could be BiPAP (Bilevel Positive Airway Pressure).

Which drug therapies are recommended?

Home oxygen therapy can be recommended if the PaO2 reduces below 55 mm of Hg or the SpO2 reduces below 88% more than twice in a 3-week period.

Other than these, the patient may be prescribed a short-acting or long-acting bronchodilator, an anticholinergic agent, inhaled corticosteroids, and methylxanthines.

Smoking cessation is critical for all patients who smoke. Nicotine replacement therapy could also be indicated in this case.

During the treatment of a patient with COLD, the amount of oxygen being delivered needs to be kept at the lowest possible for maintaining the correct levels of FiO2. Non-invasive ventilation before conventional mechanical ventilation or intubation may also be helpful in emergency situations.

Medical students and doctors can attend our AARC Approved Live Respiratory CEUs to learn more about similar cases. Our Respiratory Therapy Continuing Education CEUs are aimed at providing a clinical simulation of a range of pulmonary conditions to help you improve your knowledge and skills needed for the management of acute and chronic lung diseases.

If you already created an account with us. Please just sign in. If you need to create an account with us just follow the instructions.

Please enter your email to forgot password.

Already a member? Login

An official website of the United States government

Official websites use .gov A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS A lock ( Lock Locked padlock icon ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

Understanding of COPD among final-year medical students

Javier mohigefer, carmen calero-acuña, eduardo marquez-martin, francisco ortega-ruiz, jose luis lopez-campos.

- Author information

- Article notes

- Copyright and License information

Correspondence: Javier Mohigefer, Hospital Universitario Virgen del Rocío, Universidad de Sevilla, Avenida Manuel Siurot, s/n, 41013 Seville, Spain, Email [email protected]

Collection date 2018.

The full terms of this license are available at https://www.dovepress.com/terms.php and incorporate the Creative Commons Attribution – Non Commercial (unported, v3.0) License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/ ). By accessing the work you hereby accept the Terms. Non-commercial uses of the work are permitted without any further permission from Dove Medical Press Limited, provided the work is properly attributed.

Several previous studies have shown a suboptimal level of understanding of COPD among different population groups. Students in their final year of Medicine constitute a population that has yet to be explored. The evaluation of their understanding provides an opportunity to establish strategies to improve teaching processes. The objective of the present study is to determine the current level of understanding of COPD among said population.

A cross-sectional observational study was done using digital surveys given to medical students in their final year at the Universidad de Sevilla. Those surveyed were asked about demographic data, smoking habits as well as the clinical manifestation, diagnosis and treatment of COPD.

Of the 338 students contacted, responses were collected from 211 of them (62.4%). Only 25.2% had an accurate idea about the concept of the disease. The study found that 24.0% of students were familiar with the three main symptoms of COPD. Tobacco use was not considered a main risk factor for COPD by 1.5% of students. Of those surveyed, 22.8% did not know how to spirometrically diagnose COPD. Inhaled corticosteroids were believed to be part of the main treatment for this disease among 51.0% of the students. Results show that 36.4% of respondents believed that home oxygen therapy does not help COPD patients live longer. Only 15.0% considered the Body-mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise (BODE) index to be an important parameter for measuring the severity of COPD. Giving up smoking was not believed to prevent worsening COPD among 3.4% of students surveyed. Almost half of students (47.1%) did not recommend that those suffering from COPD undertake exercise.

The moderate level of understanding among the population of medical students in their final year shows some strengths and some shortcomings. Teaching intervention is required to reinforce solid knowledge among this population.

Keywords: COPD, knowledge, surveys and questionnaires, students, medical

Introduction

COPD, a disease characterized by persistent respiratory symptoms and airflow limitation due to airway and/or alveolar abnormalities usually caused by significant exposure to noxious particles or gases, 1 is one of the diseases with the greatest impact on world health. There are currently an estimated 328 million people suffering from COPD around the world. 2 The Global Burden of Disease Study underscores that COPD was the sixth leading cause of death in 1990, has been the fourth since 2000 and is expected to be the third by 2020. 3 Furthermore, the underdiagnosis of COPD poses a major challenge. In the EPI-SCAN study, 73% of individuals with irreversible airflow obstruction compatible with COPD were not diagnosed. 4

In this context, it is important for both the population and health professionals to have a good knowledge about this disease as a necessary step to avoiding such high underdiagnostic percentages. Unfortunately, the available evidence suggests that the lack of knowledge about the disease is high among a variety of populations. Studies have been done among patients with varying conditions, 5 among patients with COPD, 6 , 7 among doctors 8 and among the general population, 9 demonstrating suboptimal knowledge about COPD.

Studying disease understanding among final-year medical student population constitutes an especially relevant line of research for public health as it allows us to understand this population’s notions about the disease, which will help to identify weaknesses and, at the same time, allow us to design strategies for health education among this population. In the case of COPD, this information is especially relevant given its importance in epidemiology, clinical manifestation and health management. 10 Furthermore, the study of the medical student population represents an especially relevant niche since they have recently studied the disease and are close to receiving a license to practice medicine in society. 11

The benefits of the population having appropriate knowledge about the disease are clear. On one hand, for the general population, doctor–patient contact is made sooner, increasing the likelihood of earlier treatment with a potential impact on disease prognosis. 12 On the other hand, for students, better education implies lower underdiagnosis, better control and better information for the patients about their disease.

One population that has yet to be explored in this sense is that of medical students. Specifically, students in the final year of Medicine constitute an especially interesting population in the study of knowledge about the disease as they have recently studied the disease and will receive a license to practice medicine in society in a few months. However, until now, medical students’ knowledge about COPD has never been evaluated. Consequently, the objective of this study is to analyze the knowledge final-year medical students have about this disease.

The results of this study will give us the opportunity to take a closer look at the level of knowledge the students have regarding this disease and help to identify areas of improvement and to establish strategies to improve teaching for this disease.

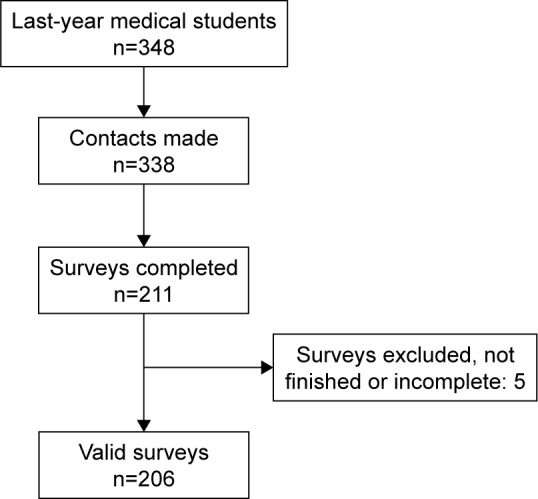

This is a cross-sectional observational study which was done using a survey about the understanding of COPD among a population of medical students in their final year at the Universidad de Sevilla (348 students). Per protocol, we set 200 surveys (58% of the total number of students) as the appropriate limit to obtain an adequate number of surveys to allow us to explore the current situation, keeping in mind an estimated loss of 8% due to surveys which were incorrectly completed or considered incomplete.

Survey content

The questions included on the survey were selected based on previous papers published about knowledge surveys 5 , 9 , 13 and based on the research team’s experience and knowledge about the disease ( Supplementary material ). The format of the questions differed according to the objective of each item. The survey included the following types of questions: multiple choice, true/false, Likert-type scales from 0 to 10 and open questions. The questions were divided into six sections: sociodemographic data about the respondent, the concept of COPD, clinical manifestation, diagnosis, non-pharmacological treatment, and pharmacological treatment. Among the sociodemographic data, respondents were asked about their degree of affinity for Pneumology, being asked to rate it on a scale of 0–10 with 10 being the greatest affinity. The questions about diagnosis were aimed at covering three concepts: the need for the spirometric criterion forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV 1 )/forced vital capacity <0.7 to diagnose obstruction, evaluating the severity of the obstruction with spirometry, and evaluating the severity according to the Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) 1 and the national Spanish guidelines for COPD management (GesEPOC) documents. 14

For true/false and multiple-choice questions, 80% correct or higher was considered a suitable result. There were three open questions: briefly define what COPD is, list the main risk factors for COPD, and list the primary symptoms of COPD. To analyze the first, the minimum elements that should appear in the answer were identified in order to consider it valid. In this way, respondents were required to identify three ideas: tobacco exposure, irreversible bronchial obstruction, and pulmonary disease. Expressing the meaning of the acronym COPD, was also evaluated. The definition was considered correct if the three concepts appeared and incorrect if one was missing, and it was noted if the answer was missing two or more concepts but the meaning of the acronym COPD was correctly defined. In the case of the second question, which requires a list, a weighted description of the different indicated answers was made. For the last question, we evaluated whether the three main symptoms (cough, expectoration and dyspnea) were identified and, at the same time, we studied what symptom was described most frequently.

Data collection

The survey was done using the Google Forms tool (Google, Mountain View, CA, USA). Once the survey was created, the URL to access it was sent to the target population using the messaging application WhatsApp (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA). The period for data collection was December 26, 2015, through February 26, 2016. During this time, a reminder was sent to those students who had not yet responded every two weeks. Participation was voluntary, confidential and anonymous.

This study was carried out in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki for research involving human subjects. During the study, no personal data were collected about the participants in the study which would allow them to be identified. The data obtained was kept strictly confidential (Spanish Organic Law 15/1999 on the protection of personal data), and only the principal investigator for the project had access to it. Each case was anonymized and numbered with a code to guarantee data confidentiality. Ethical approval was granted by the Research Ethics Committee of the University Hospitals Virgen Macarena-Virgen del Rocío. Before initially completing the survey, students accessed an information sheet ( Supplementary material ) which specified that the survey was being done in the context of a research project and the answers would not influence their final grade as students. Accordingly, the participants provided informed consent for participation in the survey.

Statistical analysis

The quality of the data was evaluated before completing a statistical analysis. To do so, we transferred the data to the program IBM SPSS Statistics version 24.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The quality analysis of data was done variable by variable, searching for missing, extreme and inconsistent values. Those surveys which were considered to be of insufficient quality were excluded from the analysis. Once the final database was obtained, a descriptive analysis of data was done using the absolute and relative frequencies for the categorical variables and the mean and standard variation in parentheses for the continuous variables. Comparison between groups (gender, tobacco use and affinity) for the subject was done using the chi-square test. In cases of 2×2 tables, the Fisher exact test was applied when the expected frequencies were less than 5 in one of the categories. To study the influence of active tobacco use on the results, habitual and occasional smokers were categorized as active smokers. Comparisons on the importance of the different diseases were done by using the unpaired t -test. The α error was set at 0.05.

Sociodemographic data

The selection of completed surveys is shown in Figure 1 . The study population comprised 348 medical students, of whom 211 (60.6%) completed the survey. After evaluating the quality of the surveys, five were discarded. Consequently, there remained 206 surveys. Participants were students, primarily females (62.6%), and had an average age of 23.3 (0.7) years. With regard to habitual tobacco use, the sample included 167 (81.1%) participants who had never smoked, nine (4.4%) former smokers, 19 (9.2%) occasional smokers and 11 (5.3%) habitual smokers. In terms of affinity for the subject, the sample comprised 30 (14.6%) respondents with a high affinity, 112 (54.4%) with an intermediate affinity, and 64 (31.1%) with a low affinity.

Selection of surveys.

Concept of COPD

The results for the survey items referring to the concept of COPD are summarized in Table 1 . Only 25.2% were able to correctly define the disease. Although before beginning the degree 72.9% had heard of the disease through different means (primarily the media, doctors and the Internet), only 17% admitted they were familiar with it before beginning their studies.

Survey results regarding understanding of COPD

Results are expressed as absolute (relative) frequency or mean (standard deviation), according to the nature of the variable.

p <0.05 for comparison between groups.

p <0.05 for comparison between diseases.

Those surveyed classified COPD as the second most severe disease after ischemic heart disease. The stance on the anti-smoking law was appropriate with a very favorable stance among active smokers (63.3%) and nonsmokers (81.3%), this difference being significant. There was also an association between familiarity with the national strategy for COPD as well as its content and an affinity for the subject ( p =0.042 and p =0.003, respectively). None of those surveyed listed the five risk factors for COPD. A relationship was observed between smokers and nonsmokers with regard to identifying tobacco use as a risk factor for COPD ( Table 1 ).

Due to lack of knowledge, 15% decided not to respond to the question about the contributing biological pathways. The most commonly indicated biological pathway was the participation of inflammatory mediators (proteins) (46.6%), followed by an increase in inflammatory cells (46.1%) and respiratory infections (42.2%).

Clinical manifestation

The results for the survey items referring to the clinical manifestation of COPD are summarized in Table 2 . Of the students surveyed, 34% recognized the symptomatology of the disease (cough, expectoration and dyspnea). With regard to these three symptoms, dyspnea was the answer most frequently given by respondents (80.6%). Only 37.9% knew that expectoration is a symptom of COPD. The identification of chronic bronchitis as a clinical finding and emphysema as a morphological finding was correctly made by just over half of the respondents, mostly females. Interestingly, 76 (36.9%) of those surveyed responded that both chronic bronchitis and emphysema are clinical concepts.

Survey results regarding clinical manifestations of COPD

Results are expressed as absolute (relative) frequencies.

The results for the survey items referring to the diagnosis of COPD are summarized in Table 3 . Although the diagnostic criteria were identified by the majority of participants, the evaluation of obstruction severity with spirometry or according to current documents was fairly poor, being worse among men and active smokers. The questions about the degree of obstruction in spirometry were answered correctly by approximately 50%, and the questions about the GOLD document classification were answered correctly by 65%, while severity evaluation according to GesEPOC was correctly done by less than 20%. When a case of obstruction with FEV 1 >80% was presented, 83 (40.3%) respondents answered that the patient did not suffer from COPD as there was no obstruction. Furthermore, 102 (49.5) participants confused moderate and severe COPD. With regard to the clinical phenotypes of COPD, those surveyed identified more phenotypes than those recognized in the GesEPOC document. 14 As for the evaluation of severity, 141 (68.4%) respondents indicated that the severity according to GesEPOC is determined by the FEV 1 .

Survey results regarding the diagnosis of COPD

Abbreviations: BODE, Body-mass index, airflow Obstruction, Dyspnea, and Exercise; FEV 1 , forced expiratory volume in 1 second; FVC, forced vital capacity; MMEF, maximal mid-expiratory flow; GOLD, Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease; OSA, obstructive sleep apnea.

Non-pharmacological treatment

The results for the survey items referring to non-pharmacological treatment are summarized in Table 4 . With regard to non-pharmacological treatment, 80% of successful answers was only achieved in two questions: the importance of giving up smoking and pneumococcal vaccination. However, the recommendations regarding exercise and the indication for oxygen therapy had a lower response. The indication for oxygen therapy was confused with the concept of respiratory distress by 64 (31.1%) respondents.

Survey results regarding non-pharmacological treatment

Pharmacological treatment

The results for the survey items referring to pharmacological treatment are summarized in Table 5 . The exploratory questions about pharmacological treatment had a correct response rate far from 80%, with the exception of the question about not abandoning treatment when symptoms improve. A higher affinity for the subject correlates to the correct use of corticosteroids ( p =0.033) as well as the appropriate use of long-acting bronchodilators during exacerbations ( p =0.038). It is worrying that 105 (51.0%) of those surveyed thought a combination of inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) and long-acting β 2 -agonist was the primary pharmacological treatment for COPD.

Survey results regarding pharmacological treatment

Abbreviations: GOLD, Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease; LABA, long-acting β 2 -agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic agonist.

This study provides information regarding knowledge about COPD among the population of medical students in their final year of study. The results indicate a moderate level of understanding among this population with notable areas of improvement including aspects regarding diagnosis, characterization and the treatment of patients suffering from the disease. Additionally, this moderate level of understanding is slightly influenced by the respondents’ gender, tobacco use, and affinity for respiratory diseases in some of the aspects evaluated.

There are similar previous experiences in the general population. Specifically, two previous studies have been done in Spain at the national level, 9 , 15 both in the national sphere and among general population. Of these, the CONOCEPOC study 9 recently obtained a total of 6,528 surveys at a 13.1% response rate with representation from every region of the country. Although there is a similar percentage of active smokers (habitual and occasional) in both studies (19.4% in CONOCEPOC vs 14.5% in the present study) with a similar evaluation of COPD severity (8.3 points in CONOCEPOC vs 7.8 in the present study), some of the results differ. In the general population, the main means of hearing about the disease is through the media (39.8% in CONOCEPOC). However, in our sample, although still the main means, this percentage is considerably lower (19.9%) with a slight difference from other surveyed sources of information. The spontaneous knowledge about COPD evaluated by CONOCEPOC (17.0%) could not be verified in our case as spontaneous knowledge has not been analyzed. However, only 44.1% of respondents knew the correct concept or were able to identify the meaning of the acronym COPD. The identification of the respiratory symptoms associated with the disease (dyspnea, cough and expectoration) was similar to the general population in the CONOCEPOC study (81.1%, 29.0% and 10.6%, respectively). The fact that in a population like ours only 37.9% identified expectoration as part of the clinical manifestation of the disease stands out. Finally, the stance on the anti-smoking law was similar in both studies, with a considerable improvement in knowledge about the national strategy for COPD in our survey (4.7% vs 34.0%).

The results of subgroup analysis should be treated with caution. This study was not intended to evaluate the differences between groups, and the results are thus informative. With regard to the gender of respondents, men showed worse identification of the concepts of chronic bronchitis and emphysema and worse identification of mild COPD by spirometry. However, they tended to recommend triple therapy more frequently. The overprescription of triple therapy for COPD treatment currently constitutes a problem in managing the disease in diverse areas of health care. In this sense, this overuse of triple therapy has recently been described in all stages of the disease, 16 including as an initial treatment. 17 Given that ICSs are not innocuous and their side effects are dose-dependent, there is an international call for the rational use of these pharmaceuticals in COPD treatment. 18

In terms of tobacco use, active smokers (habitual and occasional) were less likely to be in favor of the anti-smoking law, less commonly identified tobacco use as a risk factor for COPD and less correctly identified severe COPD by spirometry. These data seem to suggest a different attitude toward the disease. These results reinforce the need to transmit the relationship between tobacco use and COPD to the population in order for tobacco users to be aware of the potential effects tobacco use has on respiratory health. Recently, the literature has indicated that even low-intensity smokers have a higher mortality risk than nonsmokers. 19 With regard to affinity for the subject, those surveyed who indicated a high affinity heard about the disease through the Internet more frequently and provided better answers to some of the survey questions; an expected result.

In the light of these findings, it follows that initiatives for improvement in undergraduate medical education are always welcome. Different initiatives including reinforcing concepts or problem-based learning can be alternatives available for this purpose. 20 , 21

To correctly interpret our results, some methodological considerations must be kept in mind. Participation in the survey was voluntary which may imply a selection bias. Although the study was not based on a study population sample to guarantee the representiveness of the selected sample, the response rate provides a sample size that suggests that the data presented may be a reflection of the reality for students at our university. On the other hand, given the intrinsic limitations in completing a survey, the number of evaluated concepts was limited. Finally, this survey was done at a specific university within a geographical framework and set time frame. It would be ideal for future studies to confirm our findings in other geographic areas and to be completed over time in order to identify teaching processes to improve knowledge about the disease among future doctors.

Our final-year medical students identify COPD as a serious disease, and the evaluation of their knowledge about COPD highlights some areas of improvement. This study identifies the main weaknesses in diagnosis, clinical characterization and treatment. We hope these results will be useful to improve university teaching which will help in appropriately preparing doctors to diagnose and treat COPD in the community.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the final-year students at the Faculty of Medicine, Universidad de Sevilla, during the academic year 2015–2016, for their generous participation in this study.

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

- 1. Vogelmeier CF, Criner GJ, Martínez FJ, et al. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease 2017 report: GOLD executive summary. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53(3):128–149. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2017.02.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 2. Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2163–2196. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61729-2. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 3. Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Alternative projections of mortality and disability by cause 1990–2020: Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 1997;349(9064):1498–1504. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)07492-2. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 4. Miravitlles M, Soriano JB, García-Río F, et al. Prevalence of COPD in Spain: impact of undiagnosed COPD on quality of life and daily life activities. Thorax. 2009;64(10):863–868. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.115725. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 5. de Queiroz MC, Moreira MA, Jardim JR, et al. Knowledge about COPD among users of primary health care services. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;10:1–6. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S71152. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 6. Ray SM, Helmer RS, Stevens AB, Franks AS, Wallace LS. Clinical utility of the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease knowledge questionnaire. Fam Med. 2013;45(3):197–200. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 7. White R, Walker P, Roberts S, Kalisky S, White P. Bristol COPD Knowledge Questionnaire (BCKQ): testing what we teach patients about COPD. Chron Respir Dis. 2006;3(3):123–131. doi: 10.1191/1479972306cd117oa. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 8. Davis KJ, Landis SH, Oh YM, et al. Continuing to Confront COPD International Physician Survey: physician knowledge and application of COPD management guidelines in 12 countries. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2014;10:39–55. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S70162. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 9. Soriano JB, Calle M, Montemayor T, Álvarez-Sala JL, Ruiz-Manzano J, Miravitlles M. The general public’s knowledge of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and its determinants: current situation and recent changes. Arch Bronconeumol. 2012;48(9):308–315. doi: 10.1016/j.arbr.2012.07.001. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 10. López-Campos JL, Tan W, Soriano JB. Global burden of COPD. Respirology. 2016;21(1):14–23. doi: 10.1111/resp.12660. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 11. Griffin MF, Hindocha S. Publication practices of medical students at British medical schools: experience, attitudes and barriers to publish. Med Teach. 2011;33(1):e1–e8. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.530320. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 12. Welte T, Vogelmeier C, Papi A. COPD: early diagnosis and treatment to slow disease progression. Int J Clin Pract. 2015;69(3):336–349. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12522. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 13. Wong CK, Yu WC. Correlates of disease-specific knowledge in Chinese patients with COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;11:2221–2227. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S112176. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 14. Miravitlles M, Soler-Cataluña JJ, Calle M, et al. Spanish guidelines for management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (GesEPOC) 2017. Pharmacological treatment of stable phase. Arch Bronconeumol. 2017;53(6):324–335. doi: 10.1016/j.arbres.2017.03.018. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 15. Miravitlles M, de la Roza C, Morera J, et al. Chronic respiratory symptoms, spirometry and knowledge of COPD among general population. Respir Med. 2006;100(11):1973–1980. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2006.02.024. [ DOI ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 16. Brusselle G, Price D, Gruffydd-Jones K, et al. The inevitable drift to triple therapy in COPD: an analysis of prescribing pathways in the UK. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2207–2217. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S91694. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 17. Simeone JC, Luthra R, Kaila S, et al. Initiation of triple therapy maintenance treatment among patients with COPD in the US. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2016;12:73–83. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S122013. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 18. Hinds DR, DiSantostefano RL, Le HV, Pascoe S. Identification of responders to inhaled corticosteroids in a chronic obstructive pulmonary disease population using cluster analysis. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e010099. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010099. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 19. Inoue-Choi M, Liao LM, Reyes-Guzman C, Hartge P, Caporaso N, Freedman ND. Association of long-term, low-intensity smoking with all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the National Institutes of Health–AARP Diet and Health Study. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(1):87–95. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.7511. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- 20. Nendaz MR, Tekian A. Assessment in problem-based learning medical schools: a literature review. Teach Learn Med. 1999;11(4):232–243. [ Google Scholar ]

- 21. Dolmans DHJM, Loyens SMM, Marcq H, Gijbels D. Deep and surface learning in problem-based learning: a review of the literature. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2016;21(5):1087–1112. doi: 10.1007/s10459-015-9645-6. [ DOI ] [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- View on publisher site

- PDF (428.5 KB)

- Collections

Similar articles

Cited by other articles, links to ncbi databases.

- Download .nbib .nbib

- Format: AMA APA MLA NLM

Add to Collections

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Perspective

- Open access

- Published: 07 May 2015

Four patients with a history of acute exacerbations of COPD: implementing the CHEST/Canadian Thoracic Society guidelines for preventing exacerbations

- Ioanna Tsiligianni 1 , 2 ,

- Donna Goodridge 3 ,

- Darcy Marciniuk 4 ,

- Sally Hull 5 &

- Jean Bourbeau 6

npj Primary Care Respiratory Medicine volume 25 , Article number: 15023 ( 2015 ) Cite this article

61k Accesses

11 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Respiratory tract diseases

The American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society have jointly produced evidence-based guidelines for the prevention of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). This educational article gives four perspectives on how these guidelines apply to the practical management of people with COPD. A current smoker with frequent exacerbations will benefit from support to quit, and from optimisation of his inhaled treatment. For a man with very severe COPD and multiple co-morbidities living in a remote community, tele-health care may enable provision of multidisciplinary care. A woman who is admitted for the third time in a year needs a structured assessment of her care with a view to stepping up pharmacological and non-pharmacological treatment as required. The overlap between asthma and COPD challenges both diagnostic and management strategies for a lady smoker with a history of asthma since childhood. Common threads in all these cases are the importance of advising on smoking cessation, offering (and encouraging people to attend) pulmonary rehabilitation, and the importance of self-management, including an action plan supported by multidisciplinary teams.

Similar content being viewed by others

Diagnostic spirometry in COPD is increasing, a comparison of two Swedish cohorts

Phenotype and management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients in general population in China: a nationally cross-sectional study

Cardiovascular predictors of mortality and exacerbations in patients with COPD

Case study 1: a 63-year-old man with moderate/severe copd and a chest infection.

A 63-year-old self-employed plumber makes a same-day appointment for another ‘chest infection’. He caught an upper respiratory tract infection from his grandchildren 10 days ago, and he now has a productive cough with green sputum, and his breathlessness and fatigue has forced him to take time off work.

He has visited his general practitioner with similar symptoms two or three times every year in the last decade. A diagnosis of COPD was confirmed 6 years ago, and he was started on a short-acting β 2 -agonist. This helped with his day-to-day symptoms, although recently the symptoms of breathlessness have been interfering with his work and he has to pace himself to get through the day. Recovering from exacerbations takes longer than it used to—it is often 2 weeks before he is able to get back to work—and he feels bad about letting down customers. He cannot afford to retire, but is thinking about reducing his workload.

He last attended a COPD review 6 months ago when his FEV 1 was 52% predicted. He was advised to stop smoking and given a prescription for varenicline, but he relapsed after a few days and did not return for the follow-up appointment. He attends each year for his ‘flu vaccination’. His only other medication is an ACE inhibitor for hypertension.

Managing the presenting problem. Is it a COPD exacerbation?

A COPD exacerbation is defined as ‘an acute event characterised by a worsening of the patient’s respiratory symptoms that is beyond normal day-to-day variation and leads to change in medications’. 1 , 2 The worsening symptoms are usually increased dyspnoea, increased sputum volume and increased sputum purulence. 1 , 2 All these symptoms are present in our patient who experiences an exacerbation triggered by a viral upper respiratory tract infection—the most common cause of COPD exacerbations. Apart from the management of the acute exacerbation that could include antibiotics, oral steroids and increased use of short-acting bronchodilators, special attention should be given to his on-going treatment to prevent future exacerbations. 2 Short-term use of systemic corticosteroids and a course of antibiotics can shorten recovery time, improve lung function (forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV 1 )) and arterial hypoxaemia and reduce the risk of early relapse, treatment failure and length of hospital stay. 1 , 2 Short-acting inhaled β 2 -agonists with or without short-acting anti-muscarinics are usually the preferred bronchodilators for the treatment of an acute exacerbation. 1

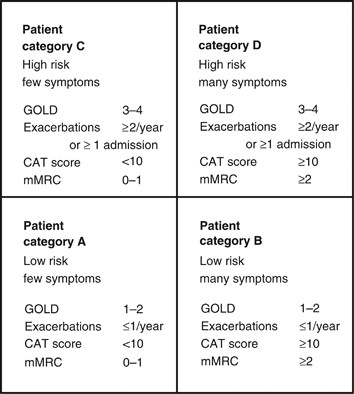

Reviewing his routine treatment

One of the concerns about this patient is that his COPD is inadequately treated. The Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) suggests that COPD management be based on a combined assessment of symptoms, GOLD classification of airflow limitation, and exacerbation rate. 1 The modified Medical Research Council (mMRC) dyspnoea score 3 or the COPD Assessment Tool (CAT) 4 could be used to evaluate the symptoms/health status. History suggests that his breathlessness has begun to interfere with his lifestyle, but this has not been formally asssessed since the diagnosis 6 years ago. Therefore, one would like to be certain that these elements are taken into consideration in future management by involving other members of the health care team. The fact that he had two to three exacerbations per year puts the patient into GOLD category C–D (see Figure 1 ) despite the moderate airflow limitation. 1 , 5 Our patient is only being treated with short-acting bronchodilators; however, this is only appropriate for patients who belong to category A. Treatment options for patients in category C or D should include long-acting muscarinic antagonists (LAMAs) or long-acting β 2 -agonists (LABAs), which will not only improve his symptoms but also help prevent future exacerbations. 2 Used in combination with LABA or LAMA, inhaled corticosteroids also contribute to preventing exacerbations. 2

The four categories of COPD based on assessment of symptoms and future risk of exacerbations (adapted by Gruffydd-Jones, 5 from the Global Strategy for Diagnosis, Management and Prevention of COPD). 1 CAT, COPD Assessment Tool; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; mMRC, modified Medical Research Council Dyspnoea Scale.

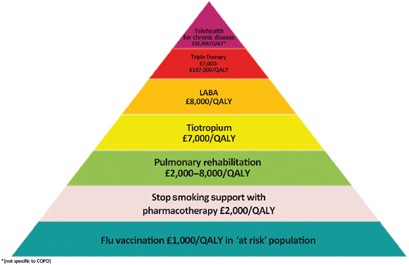

Prevention of future exacerbations

Exacerbations should be prevented as they have a negative impact on the quality of life; they adversely affect symptoms and lung function, increase economic cost, increase mortality and accelerate lung function decline. 1 , 2 Figure 2 summarises the recommendations and suggestions of the joint American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society (CHEST/CTS) Guidelines for the prevention of exacerbations in COPD. 2 The grades of recommendation from the CHEST/CTS guidelines are explained in Table 1 .

Decision tree for prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD (reproduced with permission from the CHEST/CTS Guidelines for the prevention of exacerbations in COPD). 2 This decision tree for prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD is arranged according to three key clinical questions using the PICO format: non-pharmacologic therapies, inhaled therapies and oral therapies. The wording used is ‘Recommended or Not recommended’ when the evidence was strong (Level 1) or ‘Suggested or Not suggested’ when the evidence was weak (Level 2). CHEST/CTS, American College of Chest Physicians and Canadian Thoracic Society; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; FEV 1 , forced expiratory volume in one second; FVC, forced vital capacity; LABA, long-acting β-agonist; LAMA, long-acting muscarinic antagonist; ICS, inhaled corticosteroids; SAMA, short-acting muscarinic antagonist; SABA, short-acting β-agonist; SM, self-management.

Pharmacological approach

In patients with moderate-to-severe COPD, the use of LABA or LAMA compared with placebo or short-acting bronchodilators is recommended to prevent acute exacerbations (Grades 1B and 1A, respectively). 2 , 6 , 7 LAMAs are associated with a lower rate of exacerbations compared with LABAs (Grade 1C). 2 , 6 The inhaler technique needs to be checked and a suitable device selected. If our patient does not respond to optimizing inhaled medication and continues to have two to three exacerbations per year, there are additional options that offer pulmonary rehabilitation and other forms of pharmacological therapy, such as a macrolide, theophylline, phosphodieseterase (PDE4) inhibitor or N -acetylocysteine/carbocysteine, 2 although there is no information about their relative effectiveness and the order in which they should be prescribed. The choice of prescription should be guided by the risk/benefit for a given individual, and drug availability and/or cost within the health care system.

Non-pharmacological approach

A comprehensive patient-centred approach based on the chronic care model could be of great value. 2 , 8

This should include the following elements

Vaccinations: the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine and annual influenza vaccine are suggested as part of the overall medical management in patients with COPD. 2 Although there is no clear COPD-specific evidence for the pneumococcal vaccine and the evidence is modest for influenza, the CHEST/CTS Guidelines concur with advice of the World Health Organization (WHO) 9 and national advisory bodies, 10 – 12 and supports their use in COPD patients who are at risk for serious infections. 2

Smoking cessation (including counselling and treatment) has low evidence for preventing exacerbations (Grade 2C). 2 However, the benefits from smoking cessation are outstanding as it improves COPD prognosis, slows lung function decline and improves the quality of life and symptoms. 1 , 2 , 13 , 14 Our patient has struggled to quit in the past; assessing current readiness to quit, and encouraging and supporting a future attempt is a priority in his care.

Pulmonary rehabilitation (based on exercise training, education and behaviour change) in people with moderate-to-very-severe COPD, provided within 4 weeks of an exacerbation, can prevent acute exacerbations (Grade 1C). 2 Pulmonary rehabilitation is also an effective strategy to improve symptoms, the quality of life and exercise tolerance, 15 , 16 and our patient should be encouraged to attend a course.

Self-management education with a written action plan and supported by case management providing regular direct access to a health care specialist reduces hospitalisations and prevents severe acute exacerbations (Grade 2C). 2 Some patients with good professional support can have an emergency course of steroids and antibiotics to start at the onset of an exacerbation in accordance with their plan.

Finally, close follow-up is needed for our patient as he was inadequately treated, relapsed from smoking cessation after a few days despite varenicline, and missed his follow-up appointment. A more alert health care team may have been able to identify these issues, avoid his relapse and take a timely approach to introducing additional measures to prevent his recurrent acute exacerbations.

Case study 2: A 74-year-old man with very severe COPD living alone in a remote community

A 74-year-old man has a routine telephone consultation with the respiratory team. He has very severe COPD (his FEV 1 2 years ago was 24% of predicted) and he copes with the help of his daughter who lives in the same remote community. He quit smoking the previous year after an admission to the hospital 50 miles away, which he found very stressful. He and his family managed another four exacerbations at home with courses of steroids and antibiotics, which he commenced in accordance with a self-management plan provided by the respiratory team.

His usual therapy consists of regular long-acting β 2 -agonist/inhaled steroid combination and a long-acting anti-muscarinic. He has a number of other health problems, including coronary heart disease and osteoarthritis and, in recent times, his daughter has become concerned that he is becoming forgetful. He manages at home by himself, steadfastly refusing social help and adamant that he does not want to move from the home he has lived in for 55 years.

This is a common clinical scenario, and a number of important issues require attention, with a view to optimising the management of this 74-year-old man suffering from COPD. He has very severe obstruction, is experiencing frequent acute flare-ups, is dependent and isolated and has a number of co-morbidities. To work towards preventing future exacerbations in this patient, a comprehensive plan addressing key medical and self-care issues needs to be developed that accounts for his particular context.

Optimising medical management

According to the CHEST/CTS Guidelines for prevention of acute exacerbations of COPD, 2 this patient should receive an annual influenza vaccination and may benefit from a 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine (Grades 1B and 2C, respectively). Influenza infection is associated with greater risk of mortality in COPD, as well as increased risk of hospitalisation and disease progression. 1 A diagnosis of COPD also increases the risk for pneumococcal disease and related complications, with hospitalisation rates for patients with COPD being higher than that in the general population. 10 , 17 Although existing evidence does not support the use of this vaccine specifically to prevent exacerbations of COPD, 1 administration of the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine is recommended as a component of overall medical management. 9 – 12

Long-term oxygen therapy has been demonstrated to improve survival in people with chronic hypoxaemia; 18 it would be helpful to obtain oxygen saturation levels and consider whether long-term oxygen therapy would be of benefit to this patient.