Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) for PTSD: A Case Study

Information & authors, metrics & citations, view options, introduction, empirical support, trauma history, presenting complaints, hyperarousal symptoms, avoidance/numbing symptoms, intrusive symptoms, other symptoms, previous treatments, treatment overview, sessions 1 to 3: initial phase, ipt case formulation.

I understand from our initial meeting that your interpersonal goals are to be closer to Chloe and to reduce disputes with Diane. I also understand that you’ve always experienced interpersonal difficulties, but that they grew much worse after your daughter’s abduction-triggered PTSD. You have clearly worked hard over the years to overcome problems you’ve had in social arenas, and you’ve tried numerous times to address the painful memories of past traumas that still live with you today . Your PTSD symptoms still overshadow your feelings and actions. You feel overwhelmed by both your emotions and your environment. Your symptoms are also coupled with an important current life issue you say has you’ve never discussed in past treatments: your sexual identity. Through understanding yourself in relationship to others, you cam mend your social conflicts and reduce your symptoms . You’ve discussed how hard it is to trust people, and how that has limited your social network for years. Your wife’s abduction of Chloe took away the person closest in the world to you, and has made it extremely difficult—to this day—for you to trust others, to take the risk to connect with those around you. This mistrust is very common in PTSD. Avoidance, numbing, intrusive thoughts are all symptoms of the illness. Although you say that you always had difficulty in social situations, these symptoms are not necessarily part of your character; they’re indication of an illness that you suffer from—an illness that’s treatable and not your fault. The symptoms can improve . Your mistrust has led you to minimize social contact. You’ve discussed feeling “betrayed ” or “deceived ” after trying to help others many times over . So you’ve been keeping your distance through “ electronic relationships ” that are more comfortable. Yet, you say you “yearn for closer, more real relationships!” You are going through a role transition: Uncomfortable feelings about your relationships and your own sexuality have made life extremely confusing, and it’s hard for you to know what you want from whom. What we can work on in the remaining weeks of treatment is how to navigate this transition: Do you want to stay with Diane, deepen a relationship with Jane, or what? If you can understand your feelings and use them to resolve this uncertainty, not only will your life feel better, but you symptoms are likely to subside. Does that make sense to you?

Session 4 to 10: Middle Phase

Session 11-14: termination phase, assessment of progress, complicating factors during the course of treatment, treatment implications, acknowledgments, information, published in.

- Posttraumatic stress disorder

- interpersonal psychotherapy

- affect dysregulation

- interpersonal difficulties

Affiliations

Export citations.

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download. For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu .

| Format | |

|---|---|

| Citation style | |

| Style | |

To download the citation to this article, select your reference manager software.

There are no citations for this item

View options

Login options.

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Purchase Options

Purchase this article to access the full text.

PPV Articles - APT - American Journal of Psychotherapy

Not a subscriber?

Subscribe Now / Learn More

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR ® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).

Share article link

Copying failed.

PREVIOUS ARTICLE

Next article, request username.

Can't sign in? Forgot your username? Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

Create a new account

Change password, password changed successfully.

Your password has been changed

Reset password

Can't sign in? Forgot your password?

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password.

Your Phone has been verified

As described within the American Psychiatric Association (APA)'s Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences. Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Published: 29 March 2022

Post-traumatic stress disorder: clinical and translational neuroscience from cells to circuits

- Kerry. J. Ressler ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5158-1103 1 ,

- Sabina Berretta 1 ,

- Vadim Y. Bolshakov 1 ,

- Isabelle M. Rosso 1 ,

- Edward G. Meloni 1 ,

- Scott L. Rauch 1 &

- William A. Carlezon Jr 1

Nature Reviews Neurology volume 18 , pages 273–288 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

10k Accesses

130 Citations

170 Altmetric

Metrics details

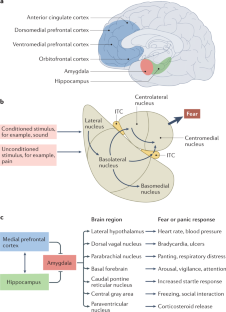

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a maladaptive and debilitating psychiatric disorder, characterized by re-experiencing, avoidance, negative emotions and thoughts, and hyperarousal in the months and years following exposure to severe trauma. PTSD has a prevalence of approximately 6–8% in the general population, although this can increase to 25% among groups who have experienced severe psychological trauma, such as combat veterans, refugees and victims of assault. The risk of developing PTSD in the aftermath of severe trauma is determined by multiple factors, including genetics — at least 30–40% of the risk of PTSD is heritable — and past history, for example, prior adult and childhood trauma. Many of the primary symptoms of PTSD, including hyperarousal and sleep dysregulation, are increasingly understood through translational neuroscience. In addition, a large amount of evidence suggests that PTSD can be viewed, at least in part, as a disorder that involves dysregulation of normal fear processes. The neural circuitry underlying fear and threat-related behaviour and learning in mammals, including the amygdala–hippocampus–medial prefrontal cortex circuit, is among the most well-understood in behavioural neuroscience. Furthermore, the study of threat-responding and its underlying circuitry has led to rapid progress in understanding learning and memory processes. By combining molecular–genetic approaches with a translational, mechanistic knowledge of fear circuitry, transformational advances in the conceptual framework, diagnosis and treatment of PTSD are possible. In this Review, we describe the clinical features and current treatments for PTSD, examine the neurobiology of symptom domains, highlight genomic advances and discuss translational approaches to understanding mechanisms and identifying new treatments and interventions for this devastating syndrome.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a debilitating neuropsychiatric disorder, characterized by re-experiencing, avoidance, negative emotions and thoughts, and hyperarousal.

PTSD is frequently comorbid with neurological conditions such as traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic epilepsy and chronic headaches.

PTSD has a prevalence of approximately 6–8% in the general population and up to 25% among individuals who have experienced severe trauma.

Many of the neural circuit mechanisms that underlie the PTSD symptoms of fear-related and threat-related behaviour, hyperarousal and sleep dysregulation are becoming increasingly clear.

Key brain regions involved in PTSD include the amygdala–hippocampus–prefrontal cortex circuit, which is among the most well-understood networks in behavioural neuroscience.

Combining molecular–genetic approaches with a mechanistic knowledge of fear circuitry will enable transformational advances in the conceptual framework, diagnosis and treatment of PTSD.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 print issues and online access

195,33 € per year

only 16,28 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Neurobiology of BDNF in fear memory, sensitivity to stress, and stress-related disorders

Impaired learning, memory, and extinction in posttraumatic stress disorder: translational meta-analysis of clinical and preclinical studies

Prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and threat processing: implications for PTSD

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edn (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013).

Breslau, N. et al. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit area survey of trauma. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 55 , 626–632 (1998).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Breslau, N., Peterson, E. L., Poisson, L. M., Schultz, L. R. & Lucia, V. C. Estimating post-traumatic stress disorder in the community: lifetime perspective and the impact of typical traumatic events. Psychol. Med. 34 , 889–898 (2004).

Bromet, E., Sonnega, A. & Kessler, R. C. Risk factors for DSM-III-R posttraumatic stress disorder: findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Am. J. Epidemiol. 147 , 353–361 (1998).

McLaughlin, K. A. et al. Subthreshold posttraumatic stress disorder in the world health organization world mental health surveys. Biol. Psychiatry 77 , 375–384 (2015).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Jovanovic, T., Kazama, A., Bachevalier, J. & Davis, M. Impaired safety signal learning may be a biomarker of PTSD. Neuropharmacology 62 , 695–704 (2011).

Article PubMed PubMed Central CAS Google Scholar

Jovanovic, T. & Ressler, K. J. How the neurocircuitry and genetics of fear inhibition may inform our understanding of PTSD. Am. J. Psychiatry 167 , 648–662 (2010).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Morgan, C. A., Grillon, C., Southwick, S. M., Davis, M. & Charney, D. S. Fear-potentiated startle in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 38 , 378–385 (1995).

Rauch, S. L. et al. Exaggerated amygdala response to masked facial stimuli in posttraumatic stress disorder: a functional MRI study. Biol. Psychiatry 47 , 769–776 (2000).

Shin, L. M. et al. A functional magnetic resonance imaging study of amygdala and medial prefrontal cortex responses to overtly presented fearful faces in posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 62 , 273–281 (2005).

Mellman, T. A., Pigeon, W. R., Nowell, P. D. & Nolan, B. Relationships between REM sleep findings and PTSD symptoms during the early aftermath of trauma. J. Trauma. Stress 20 , 893–901 (2007).

Yehuda, R. & LeDoux, J. Response variation following trauma: a translational neuroscience approach to understanding PTSD. Neuron 56 , 19–32 (2007).

Koenen, K. C., Goodwin, R., Struening, E., Hellman, F. & Guardino, M. Posttraumatic stress disorder and treatment seeking in a national screening sample. J. Trauma. Stress 16 , 5–16 (2003).

Koenen, K. C. et al. A high risk twin study of combat-related PTSD comorbidity. Twin Res. 6 , 218–226 (2003).

True, W. R. et al. A twin study of genetic and environmental contributions to liability for posttraumatic stress symptoms. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 50 , 257–264 (1993).

Stein, M. B. et al. Genome-wide association studies of posttraumatic stress disorder in 2 cohorts of US Army soldiers. JAMA Psychiatry 73 , 695–704 (2016).

Stein, M. B., Jang, K. L., Taylor, S., Vernon, P. A. & Livesley, W. J. Genetic and environmental influences on trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: a twin study. Am. J. Psychiatry 159 , 1675–1681 (2002).

Duncan, L. E. et al. Largest GWAS of PTSD ( N =20 070) yields genetic overlap with schizophrenia and sex differences in heritability. Mol. Psychiatry 23 , 666–673 (2018).

Reuveni, I. et al. Anatomical and functional connectivity in the default mode network of post-traumatic stress disorder patients after civilian and military-related trauma. Hum. Brain Mapp. 37 , 589–599 (2015).

Porter, B., Bonanno, G. A., Frasco, M. A., Dursa, E. K. & Boyko, E. J. Prospective post-traumatic stress disorder symptom trajectories in active duty and separated military personnel. J. Psychiatr. Res. 89 , 55–64 (2017).

Ballenger, J. C. et al. Consensus statement update on posttraumatic stress disorder from the international consensus group on depression and anxiety. J. Clin. Psychiatry 65 (Suppl. 1), 55–62 (2004).

PubMed Google Scholar

Heim, C. & Nemeroff, C. B. The role of childhood trauma in the neurobiology of mood and anxiety disorders: preclinical and clinical studies. Biol. Psychiatry 49 , 1023–1039 (2001).

Kessler, R. C. et al. Trauma and PTSD in the WHO world mental health surveys. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 8 , 1353383 (2017).

Huckins, L. M. et al. Analysis of genetically regulated gene expression identifies a prefrontal PTSD gene, SNRNP35, specific to military cohorts. Cell Rep. 31 , 107716 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Koenen, K. C. et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the World Mental Health Surveys. Psychol. Med. 47 , 2260–2274 (2017).

Kornfield, S. L., Hantsoo, L. & Epperson, C. N. What does sex have to do with it? The role of sex as a biological variable in the development of posttraumatic stress disorder. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 20 , 39 (2018).

Kessler, R. C., Sonnega, A., Bromet, E., Hughes, M. & Nelson, C. B. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 52 , 1048–1060 (1995).

Davis, M. The role of the amygdala in fear and anxiety. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 15 , 353–375 (1992).

Davis, M. in The Amygdala , Second Edition: A Functional Analysis (ed. Aggleton, J. P.) 213–287 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2000).

LeDoux, J. E., Cicchetti, P., Xagoraris, A. & Romanski, L. M. The lateral amygdaloid nucleus: sensory interface of the amygdala in fear conditioning. J. Neurosci. 10 , 1062–1069 (1990).

Maren, S. The amygdala, synaptic plasticity, and fear memory. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 985 , 106–113 (2003).

Pitkanen, A. in The Amygdala, Second Edition: A Functional Analysis (ed. Aggleton, J. P.) 31–116 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2000).

Milad, M. R. & Quirk, G. J. Neurons in medial prefrontal cortex signal memory for fear extinction. Nature 420 , 70–74 (2002).

McCullough, K. M., Morrison, F. G. & Ressler, K. J. Bridging the gap: towards a cell-type specific understanding of neural circuits underlying fear behaviors. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 135 , 27–39 (2016).

Mobbs, D. et al. Viewpoints: approaches to defining and investigating fear. Nat. Neurosci. 22 , 1205–1216 (2019).

Ressler, K. J. Translating across circuits and genetics toward progress in fear- and anxiety-related disorders. Am. J. Psychiatry 177 , 214–222 (2020).

Fenster, R. J., Lebois, L. A. M., Ressler, K. J. & Suh, J. Brain circuit dysfunction in post-traumatic stress disorder: from mouse to man. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 19 , 535–551 (2018).

McAllister, T. W. Psychopharmacological issues in the treatment of TBI and PTSD. Clin. Neuropsychol. 23 , 1338–1367 (2009).

Strawn, J. R., Keeshin, B. R., DelBello, M. P., Geracioti, T. D. Jr. & Putnam, F. W. Psychopharmacologic treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: a review. J. Clin. Psychiatry 71 , 932–941 (2010).

Abdallah, C. G., Southwick, S. M. & Krystal, J. H. Neurobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a path from novel pathophysiology to innovative therapeutics. Neurosci. Lett. 649 , 130–132 (2017).

Stojek, M. M., McSweeney, L. B. & Rauch, S. A. M. Neuroscience informed prolonged exposure practice: increasing efficiency and efficacy through mechanisms. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 12 , 281 (2018).

Kelmendi, B., Adams, T. G., Soutwick, S., Abdallah, C. G. & Krystal, J. H. Posttraumatic stress disorder: an integrated overview and neurobiological rationale for pharmacology. Clin. Psychol. 24 , 281–297 (2017).

Google Scholar

Krystal, J. H. et al. It is time to address the crisis in the pharmacotherapy of posttraumatic stress disorder: a consensus statement of the PTSD Psychopharmacology Working Group. Biol. Psychiatry 82 , e51–e59 (2017).

Stein, D. J. et al. Dissociation in posttraumatic stress disorder: evidence from the world mental health surveys. Biol. Psyhiatry 73 , 302–312 (2013).

Article Google Scholar

Lebois, L. A. M. et al. Large-scale functional brain network architecture changes associated with trauma-related dissociation. Am. J. Psychiatry 178 , 165–173 (2021).

Nicholson, A. A. et al. Dynamic causal modeling in PTSD and its dissociative subtype: bottom-up versus top-down processing within fear and emotion regulation circuitry. Hum. Brain Mapp. 38 , 5551–5561 (2017).

Stein, M. B. et al. Genome-wide analyses of psychological resilience in U.S. Army soldiers. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 180 , 310–319 (2019).

Nievergelt, C. M. et al. Genomic predictors of combat stress vulnerability and resilience in U.S. Marines: a genome-wide association study across multiple ancestries implicates PRTFDC1 as a potential PTSD gene. Psychoneuroendocrinology 51 , 459–471 (2015).

Thompson, N. J., Fiorillo, D., Rothbaum, B. O., Ressler, K. J. & Michopoulos, V. Coping strategies as mediators in relation to resilience and posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Affect. Disord. 225 , 153–159 (2018).

van Rooij, S. J. H. et al. Hippocampal activation during contextual fear inhibition related to resilience in the early aftermath of trauma. Behav. Brain Res. 408 , 113282 (2021).

Wingo, A. P., Ressler, K. J. & Bradley, B. Resilience characteristics mitigate tendency for harmful alcohol and illicit drug use in adults with a history of childhood abuse: a cross-sectional study of 2024 inner-city men and women. J. Psychiatr. Res. 51 , 93–99 (2014).

Wrenn, G. L. et al. The effect of resilience on posttraumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed inner-city primary care patients. J. Natl Med. Assoc. 103 , 560–566 (2011).

Astill Wright, L., Horstmann, L., Holmes, E. A. & Bisson, J. I. Consolidation/reconsolidation therapies for the prevention and treatment of PTSD and re-experiencing: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Transl. Psychiatry 11 , 453 (2021).

Linnstaedt, S. D., Zannas, A. S., McLean, S. A., Koenen, K. C. & Ressler, K. J. Literature review and methodological considerations for understanding circulating risk biomarkers following trauma exposure. Mol. Psychiatry 25 , 1986–1999 (2020).

McLean, S. A. et al. The AURORA Study: a longitudinal, multimodal library of brain biology and function after traumatic stress exposure. Mol. Psychiatry 25 , 283–296 (2020).

Iyadurai, L. et al. Preventing intrusive memories after trauma via a brief intervention involving Tetris computer game play in the emergency department: a proof-of-concept randomized controlled trial. Mol. Psychiatry 23 , 674–682 (2018).

Rothbaum, B. O. et al. Early intervention following trauma may mitigate genetic risk for PTSD in civilians: a pilot prospective emergency department study. J. Clin. Psychiatry 75 , 1380–1387 (2014).

Seal, K. H. & Stein, M. B. Preventing the pain of PTSD. Sci. Transl Med. 5 , 188fs122 (2013).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Zohar, J. et al. Secondary prevention of chronic PTSD by early and short-term administration of escitalopram: a prospective randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. J. Clin. Psychiatry 79 , 16m10730 (2018).

Zohar, J. et al. High dose hydrocortisone immediately after trauma may alter the trajectory of PTSD: interplay between clinical and animal studies. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 21 , 796–809 (2011).

Myers, K. M. & Davis, M. Mechanisms of fear extinction. Mol. Psychiatry 12 , 120–150 (2007).

Ross, D. A. et al. An integrated neuroscience perspective on formulation and treatment planning for posttraumatic stress disorder: an educational review. JAMA Psychiatry 74 , 407–415 (2017).

LaBar, K. S., Gatenby, J. C., Gore, J. C., LeDoux, J. E. & Phelps, E. A. Human amygdala activation during conditioned fear acquisition and extinction: a mixed-trial fMRI study. Neuron 20 , 937–945 (1998).

LeDoux, J. The amygdala. Curr. Biol. 17 , R868–R874 (2007).

Rogan, M. T., Staubli, U. V. & LeDoux, J. E. Fear conditioning induces associative long-term potentiation in the amygdala. Nature 390 , 604–607 (1997).

Myers, K. M. & Davis, M. Behavioral and neural analysis of extinction. Neuron 36 , 567–584 (2002).

Chhatwal, J. P., Myers, K. M., Ressler, K. J. & Davis, M. Regulation of gephyrin and GABAA receptor binding within the amygdala after fear acquisition and extinction. J. Neurosci. 25 , 502–506 (2005).

Herry, C. et al. Switching on and off fear by distinct neuronal circuits. Nature 454 , 600–606 (2008).

Lee, J., An, B. & Choi, S. Longitudinal recordings of single units in the basal amygdala during fear conditioning and extinction. Sci. Rep. 11 , 11177 (2021).

McCullough, K. M. et al. Molecular characterization of Thy1 expressing fear-inhibiting neurons within the basolateral amygdala. Nat. Commun. 7 , 13149 (2016).

Jasnow, A. M. et al. Thy1-expressing neurons in the basolateral amygdala may mediate fear inhibition. J. Neurosci. 33 , 10396–10404 (2013).

Hinrichs, R. et al. Increased skin conductance response in the immediate aftermath of trauma predicts PTSD risk. Chronic Stress 3 , 1–11 (2019).

Milad, M. R. et al. Neurobiological basis of failure to recall extinction memory in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 66 , 1075–1082 (2009).

Etkin, A. & Wager, T. D. Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: a meta-analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. Am. J. Psychiatry 164 , 1476–1488 (2007).

Steuber, E. R. et al. Thalamic volume and fear extinction interact to predict acute posttraumatic stress severity. Psychiatry Res. 141 , 325–332 (2021).

Kredlow, M. A., Fenster, R. J., Laurent, E. S., Ressler, K. J. & Phelps, E. A. Prefrontal cortex, amygdala and threat processing: implications for PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology 47 , 247–259 (2022).

Maddox, S. A., Hartmann, J., Ross, R. A. & Ressler, K. J. Deconstructing the gestalt: mechanisms of fear, threat, and trauma memory encoding. Neuron 102 , 60–74 (2019).

Tsvetkov, E., Carlezon, W. A., Benes, F. M., Kandel, E. R. & Bolshakov, V. Y. Fear conditioning occludes LTP-induced presynaptic enhancement of synaptic transmission in the cortical pathway to the lateral amygdala. Neuron 34 , 289–300 (2002).

Josselyn, S. A. et al. Long-term memory is facilitated by cAMP response element-binding protein overexpression in the amygdala. J. Neurosci. 21 , 2404–2412 (2001).

Bremner, J. D. et al. MRI-based measurement of hippocampal volume in patients with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 152 , 973–981 (1995).

Bremner, J. D. et al. The environment contributes more than genetics to smaller hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). J. Psychiatr. Res. 137 , 579–588 (2021).

Logue, M. W. et al. Smaller hippocampal volume in posttraumatic stress disorder: a multisite ENIGMA-PGC study: subcortical volumetry results from posttraumatic stress disorder consortia. Biol. Psychiatry 83 , 244–253 (2018).

Heldt, S. A., Stanek, L., Chhatwal, J. P. & Ressler, K. J. Hippocampus-specific deletion of BDNF in adult mice impairs spatial memory and extinction of aversive memories. Mol. Psychiatry 12 , 656–670 (2007).

Ji, J. & Maren, S. Electrolytic lesions of the dorsal hippocampus disrupt renewal of conditional fear after extinction. Learn. Mem. 12 , 270–276 (2005).

Parsons, R. G. & Ressler, K. J. Implications of memory modulation for post-traumatic stress and fear disorders. Nat. Neurosci. 16 , 146–153 (2013).

Brown, E. S., Rush, A. J. & McEwen, B. S. Hippocampal remodeling and damage by corticosteroids: implications for mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 21 , 474–484 (1999).

Herrmann, L. et al. Long-lasting hippocampal synaptic protein loss in a mouse model of posttraumatic stress disorder. PLoS ONE 7 , e42603 (2012).

Hobin, J. A., Goosens, K. A. & Maren, S. Context-dependent neuronal activity in the lateral amygdala represents fear memories after extinction. J. Neurosci. 23 , 8410–8416 (2003).

Peters, J., Dieppa-Perea, L. M., Melendez, L. M. & Quirk, G. J. Induction of fear extinction with hippocampal-infralimbic BDNF. Science 328 , 1288–1290 (2010).

Milad, M. R. et al. Recall of fear extinction in humans activates the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus in concert. Biol. Psychiatry 62 , 446–454 (2007).

Milad, M. R. et al. Thickness of ventromedial prefrontal cortex in humans is correlated with extinction memory. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102 , 10706–10711 (2005).

Santhanam, P. et al. Decreases in white matter integrity of ventro-limbic pathway linked to post-traumatic stress disorder in mild traumatic brain injury. J. Neurotrauma 36 , 1093–1098 (2019).

Koch, S. B. J. et al. Decreased uncinate fasciculus tract integrity in male and female patients with PTSD: a diffusion tensor imaging study. J. Psychiatry Neurosci. 42 , 331–342 (2017).

Kennis, M., van Rooij, S. J. H., Reijnen, A. & Geuze, E. The predictive value of dorsal cingulate activity and fractional anisotropy on long-term PTSD symptom severity. Depress. Anxiety 34 , 410–418 (2017).

Sotres-Bayon, F., Sierra-Mercado, D., Pardilla-Delgado, E. & Quirk, G. J. Gating of fear in prelimbic cortex by hippocampal and amygdala inputs. Neuron 76 , 804–812 (2012).

Lanius, R. A., Brand, B., Vermetten, E., Frewen, P. A. & Spiegel, D. The dissociative subtype of posttraumatic stress disorder: rationale, clinical and neurobiological evidence, and implications. Depress. Anxiety 29 , 701–708 (2012).

Mellman, T. A. & Hipolito, M. M. Sleep disturbances in the aftermath of trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder. CNS Spectr. 11 , 611–615 (2006).

Neylan, T. C. et al. Prior sleep problems and adverse post-traumatic neuropsychiatric sequelae of motor vehicle collision in the AURORA study. Sleep 44 , zsaa200 (2021).

van Liempt, S., van Zuiden, M., Westenberg, H., Super, A. & Vermetten, E. Impact of impaired sleep on the development of PTSD symptoms in combat veterans: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. Depress Anxiety 30 , 469–474 (2013).

Pruiksma, K. E. et al. Residual sleep disturbances following PTSD treatment in active duty military personnel. Psychol. Trauma. 8 , 697–701 (2016).

Bryant, R. A., O’Donnell, M. L., Creamer, M., McFarlane, A. C. & Silove, D. Posttraumatic intrusive symptoms across psychiatric disorders. J. Psychiatr. Res. 45 , 842–847 (2011).

Phelps, A. J. et al. Polysomnography study of the post-traumatic nightmares of post-traumatic stress disorder. Sleep 41 , zsx188 (2018).

Harb, G. C. et al. A critical review of the evidence base of imagery rehearsal for posttraumatic nightmares: pointing the way for future research. J. Trauma. Stress 26 , 570–579 (2013).

Norrholm, S. D. et al. Fear load: the psychophysiological over-expression of fear as an intermediate phenotype associated with trauma reactions. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 98 , 270–275 (2015).

Fani, N. et al. Attention bias toward threat is associated with exaggerated fear expression and impaired extinction in PTSD. Psychol. Med. 42 , 533–543 (2012).

Norrholm, S. D. et al. Fear extinction in traumatized civilians with posttraumatic stress disorder: relation to symptom severity. Biol. Psychiatry 69 , 556–563 (2011).

Colvonen, P. J., Straus, L. D., Acheson, D. & Gehrman, P. A review of the relationship between emotional learning and memory, sleep, and PTSD. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 21 , 2 (2019).

van Liempt, S. et al. Sympathetic activity and hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis activity during sleep in post-traumatic stress disorder: a study assessing polysomnography with simultaneous blood sampling. Psychoneuroendocrinology 38 , 155–165 (2013).

Article PubMed CAS Google Scholar

Lipinska, G. & Thomas, K. J. F. Rapid eye movement fragmentation, not slow-wave sleep, predicts neutral declarative memory consolidation in posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Sleep. Res. 28 , e12846 (2019).

Onton, J. A., Matthews, S. C., Kang, D. Y. & Coleman, T. P. In-home sleep recordings in military veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder reveal less REM and deep sleep <1 Hz. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 12 , 196 (2018).

Wells, A. M. et al. Effects of chronic social defeat stress on sleep and circadian rhythms are mitigated by kappa-opioid receptor antagonism. J. Neurosci. 37 , 7656–7668 (2017).

Hasler, B. P., Insana, S. P., James, J. A. & Germain, A. Evening-type military veterans report worse lifetime posttraumatic stress symptoms and greater brainstem activity across wakefulness and REM sleep. Biol. Psychol. 94 , 255–262 (2013).

Nestler, E. J. & Carlezon, W. A. Jr. The mesolimbic dopamine reward circuit in depression. Biol. Psychiatry 59 , 1151–1159 (2006).

McCullough, K. M. et al. Nucleus accumbens medium spiny neuron subtypes differentially regulate stress-associated alterations in sleep architecture. Biol. Psychiatry 89 , 1138–1149 (2021).

Sijbrandij, M., Engelhard, I. M., Lommen, M. J., Leer, A. & Baas, J. M. Impaired fear inhibition learning predicts the persistence of symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). J. Psychiatr. Res. 47 , 1991–1997 (2013).

Rothbaum, B. O. & Davis, M. Applying learning principles to the treatment of post-trauma reactions. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1008 , 112–121 (2003).

Ressler, K. J. et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder is associated with PACAP and the PAC1 receptor. Nature 470 , 492–497 (2011).

Ladd, C. O., Plotsky, P. M., Davis, M. in Encyclopedia of Stress 2nd edn (ed. George Fink) 561–568 (Academic, 2007).

Davis, M. Sensitization of the acoustic startle reflex by footshock. Behav. Neurosci. 103 , 495–503 (1989).

Grillon, C., Ameli, R., Woods, S. W., Merikangas, K. & Davis, M. Fear-potentiated startle in humans: effects of anticipatory anxiety on the acoustic blink reflex. Psychophysiology 28 , 588–595 (1991).

Giardino, W. J. & Pomrenze, M. B. Extended amygdala neuropeptide circuitry of emotional arousal: waking up on the wrong side of the bed nuclei of stria terminalis. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 15 , 613025 (2021).

Hinrichs, R. et al. Mobile assessment of heightened skin conductance in posttraumatic stress disorder. Depress Anxiety 34 , 502–507 (2017).

Neylan, T. C., Schadt, E. E. & Yehuda, R. Biomarkers for combat-related PTSD: focus on molecular networks from high-dimensional data. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 5 , 23938 (2014).

Yehuda, R., Giller, E. L., Southwick, S. M., Lowy, M. T. & Mason, J. W. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal dysfunction in posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 30 , 1031–1048 (1991).

Yehuda, R. et al. Enhanced suppression of cortisol following dexamethasone administration in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 150 , 83–86 (1993).

Han, X. & Boyden, E. S. Multiple-color optical activation, silencing, and desynchronization of neural activity, with single-spike temporal resolution. PLoS ONE 2 , e299 (2007).

Dunlop, B. W. et al. Corticotropin-releasing factor receptor 1 antagonism is ineffective for women with posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 82 , 866–874 (2017).

Jovanovic, T. et al. Psychophysiological treatment outcomes: corticotropin-releasing factor type 1 receptor antagonist increases inhibition of fear-potentiated startle in PTSD patients. Psychophysiology 57 , e13356 (2020).

Galatzer-Levy, I. R. & Bryant, R. A. 636,120 ways to have posttraumatic stress disorder. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 8 , 651–662 (2013).

Brewin, C. R. The nature and significance of memory disturbance in posttraumatic stress disorder. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 7 , 203–227 (2011).

Vasterling, J. J. & Arditte Hall, K. A. Neurocognitive and information processing biases in posttraumatic stress disorder. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 20 , 99 (2018).

Stevens, J. S. & Jovanovic, T. Role of social cognition in post-traumatic stress disorder: a review and meta-analysis. Genes Brain Behav. 18 , e12518 (2019).

Mathias, J. L. & Mansfield, K. M. Prospective and declarative memory problems following moderate and severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Inj. 19 , 271–282 (2005).

Acosta, S. A. et al. Influence of post-traumatic stress disorder on neuroinflammation and cell proliferation in a rat model of traumatic brain injury. PLoS ONE 8 , e81585 (2013).

Elzinga, B. M. & Bremner, J. D. Are the neural substrates of memory the final common pathway in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)? J. Affect. Disord. 70 , 1–17 (2002).

Germine, L. T. et al. Neurocognition after motor vehicle collision and adverse post-traumatic neuropsychiatric sequelae within 8 weeks: initial findings from the AURORA study. J. Affect. Disord. 298 , 57–67 (2022).

Ben-Zion, Z. et al. Neuroanatomical risk factors for posttraumatic stress disorder in recent trauma survivors. Biol. Psychiatry Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging 5 , 311–319 (2020).

Dark, H. E., Harnett, N. G., Knight, A. J. & Knight, D. C. Hippocampal volume varies with acute posttraumatic stress symptoms following medical trauma. Behav. Neurosci. 135 , 71–78 (2021).

van Rooij, S. J. H. et al. The role of the Hippocampus in predicting future posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in recently traumatized civilians. Biol. Psychiatry 84 , 106–115 (2018).

Girgenti, M. J. et al. Transcriptomic organization of the human brain in post-traumatic stress disorder. Nat. Neurosci. 24 , 24–33 (2021).

Wolf, E. J. et al. Klotho, PTSD, and advanced epigenetic age in cortical tissue. Neuropsychopharmacology 46 , 721–730 (2021).

Olive, I., Makris, N., Densmore, M., McKinnon, M. C. & Lanius, R. A. Altered basal forebrain BOLD signal variability at rest in posttraumatic stress disorder: a potential candidate vulnerability mechanism for neurodegeneration in PTSD. Hum. Brain Mapp. 42 , 3561–3575 (2021).

Mohlenhoff, B. S., O’Donovan, A., Weiner, M. W. & Neylan, T. C. Dementia risk in posttraumatic stress disorder: the relevance of sleep-related abnormalities in brain structure, amyloid, and inflammation. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 19 , 89 (2017).

Miller, M. W. & Sadeh, N. Traumatic stress, oxidative stress and post-traumatic stress disorder: neurodegeneration and the accelerated-aging hypothesis. Mol. Psychiatry 19 , 1156–1162 (2014).

Mohamed, A. Z., Cumming, P., Gotz, J. & Nasrallah, F., Department of Defense Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative. Tauopathy in veterans with long-term posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 46 , 1139–1151 (2019).

Kaplan, G. B., Vasterling, J. J. & Vedak, P. C. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in traumatic brain injury, post-traumatic stress disorder, and their comorbid conditions: role in pathogenesis and treatment. Behav. Pharmacol. 21 , 427–437 (2010).

Mojtabavi, H., Saghazadeh, A., van den Heuvel, L., Bucker, J. & Rezaei, N. Peripheral blood levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 15 , e0241928 (2020).

Licznerski, P. et al. Decreased SGK1 expression and function contributes to behavioral deficits induced by traumatic stress. PLoS Biol. 13 , e1002282 (2015).

de Kloet, C. S. et al. Assessment of HPA-axis function in posttraumatic stress disorder: pharmacological and non-pharmacological challenge tests, a review. J. Psychiatr. Res. 40 , 550–567 (2006).

Hawn, S. E. et al. GxE effects of FKBP5 and traumatic life events on PTSD: a meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 243 , 455–462 (2019).

Zannas, A. S. & Binder, E. B. Gene-environment interactions at the FKBP5 locus: sensitive periods, mechanisms and pleiotropism. Genes Brain Behav. 13 , 25–37 (2014).

Friend, S. F., Nachnani, R., Powell, S. B. & Risbrough, V. B. C-Reactive protein: marker of risk for post-traumatic stress disorder and its potential for a mechanistic role in trauma response and recovery. Eur. J. Neurosci. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejn.15031 (2020).

Michopoulos, V. et al. Association of prospective risk for chronic PTSD symptoms with low TNFα and IFNγ concentrations in the immediate aftermath of trauma exposure. Am. J. Psychiatry 177 , 58–65 (2020).

Michopoulos, V., Powers, A., Gillespie, C. F., Ressler, K. J. & Jovanovic, T. Inflammation in fear- and anxiety-based disorders: PTSD, GAD, and beyond. Neuropsychopharmacology 42 , 254–270 (2017).

Michopoulos, V. et al. Association of CRP genetic variation and CRP level with elevated PTSD symptoms and physiological responses in a civilian population with high levels of trauma. Am. J. Psychiatry 172 , 353–362 (2015).

Smith, A. K. et al. Differential immune system DNA methylation and cytokine regulation in post-traumatic stress disorder. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 156B , 700–708 (2011).

Siegel, C. E. et al. Utilization of machine learning for identifying symptom severity military-related PTSD subtypes and their biological correlates. Transl. Psychiatry 11 , 227 (2021).

Wuchty, S. et al. Integration of peripheral transcriptomics, genomics, and interactomics following trauma identifies causal genes for symptoms of post-traumatic stress and major depression. Mol. Psychiatry 26 , 3077–3092 (2021).

Kuan, P. F. et al. PTSD is associated with accelerated transcriptional aging in World Trade Center responders. Transl. Psychiatry 11 , 311 (2021).

Logue, M. W. et al. An epigenome-wide association study of posttraumatic stress disorder in US veterans implicates several new DNA methylation loci. Clin. Epigenetics 12 , 46 (2020).

Sheerin, C. M. et al. Epigenome-wide study of posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity in a treatment-seeking adolescent sample. J. Trauma. Stress 34 , 607–615 (2021).

Yang, R. et al. A DNA methylation clock associated with age-related illnesses and mortality is accelerated in men with combat PTSD. Mol. Psychiatry 26 , 4999–5009 (2020).

Smith, A. K. et al. DNA extracted from saliva for methylation studies of psychiatric traits: evidence tissue specificity and relatedness to brain. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 168B , 36–44 (2015).

Nievergelt, C. M. et al. International meta-analysis of PTSD genome-wide association studies identifies sex- and ancestry-specific genetic risk loci. Nat. Commun. 10 , 4558 (2019).

Gelernter, J. et al. Genome-wide association study of maximum habitual alcohol intake in >140,000 U.S. European and African American veterans yields novel risk loci. Biol. Psychiatry 86 , 365–376 (2019).

Stein, M. B. et al. Genome-wide association analyses of post-traumatic stress disorder and its symptom subdomains in the Million Veteran Program. Nat. Genet. 53 , 174–184 (2021).

Gelernter, J. et al. Genome-wide association study of post-traumatic stress disorder reexperiencing symptoms in >165,000 US veterans. Nat. Neurosci. 22 , 1394–1401 (2019).

Logue, M. W. et al. The Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Workgroup: posttraumatic stress disorder enters the age of large-scale genomic collaboration. Neuropsychopharmacology 40 , 2287–2297 (2015).

Pape, J. C. et al. DNA methylation levels are associated with CRF 1 receptor antagonist treatment outcome in women with post-traumatic stress disorder. Clin. Epigenetics 10 , 136 (2018).

Mizuno, Y. More than 20 years of the discovery of Park2. Neurosci. Res. 159 , 3–8 (2020).

Shaltouki, A. et al. Mitochondrial alterations by PARKIN in dopaminergic neurons using PARK2 patient-specific and PARK2 knockout isogenic iPSC lines. Stem Cell Rep. 4 , 847–859 (2015).

Binder, E. B. et al. Association of FKBP5 polymorphisms and childhood abuse with risk of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in adults. JAMA 299 , 1291–1305 (2008).

Heim, C., Owens, M. J., Plotsky, P. M. & Nemeroff, C. B. Persistent changes in corticotropin-releasing factor systems due to early life stress: relationship to the pathophysiology of major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychopharmacol. Bull. 33 , 185–192 (1997).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Bremner, J. D. et al. Elevated CSF corticotropin-releasing factor concentrations in posttraumatic stress disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry 154 , 624–629 (1997).

Dias, B. G. & Ressler, K. J. PACAP and the PAC1 receptor in post-traumatic stress disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 38 , 245–246 (2013).

Ross, R. A. et al. Circulating PACAP peptide and PAC1R genotype as possible transdiagnostic biomarkers for anxiety disorders in women: a preliminary study. Neuropsychopharmacology 45 , 1125–1133 (2020).

Bangasser, D. A. et al. Sex differences in corticotropin-releasing factor receptor signaling and trafficking: potential role in female vulnerability to stress-related psychopathology. Mol. Psychiatry 15 , 896–904 (2010).

Jovanovic, T. et al. PAC1 receptor (ADCYAP1R1) genotype is associated with dark-enhanced startle in children. Mol. Psychiatry 18 , 742–743 (2013).

Miles, O. W. & Maren, S. Role of the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis in PTSD: insights from preclinical models. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 13 , 68 (2019).

Stroth, N., Holighaus, Y., Ait-Ali, D. & Eiden, L. E. PACAP: a master regulator of neuroendocrine stress circuits and the cellular stress response. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 1220 , 49–59 (2011).

Ramikie, T. S. & Ressler, K. J. Mechanisms of sex differences in fear and posttraumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 83 , 876–885 (2018).

Mercer, K. B. et al. Functional evaluation of a PTSD-associated genetic variant: estradiol regulation and ADCYAP1R1. Transl. Psychiatry 6 , e978 (2016).

Klengel, T. et al. Allele-specific FKBP5 DNA demethylation mediates gene-childhood trauma interactions. Nat. Neurosci. 16 , 33–41 (2013).

Fani, N. et al. FKBP5 and attention bias for threat: associations with hippocampal function and shape. JAMA Psychiatry 70 , 392–400 (2013).

Galatzer-Levy, I. R. et al. A cross species study of heterogeneity in fear extinction learning in relation to FKBP5 variation and expression: implications for the acute treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Neuropharmacology 116 , 188–195 (2017).

Yun, J. Y., Jin, M. J., Kim, S. & Lee, S. H. Stress-related cognitive style is related to volumetric change of the hippocampus and FK506 binding protein 5 polymorphism in post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychol. Med. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291720002949 (2020).

Hartmann, J. et al. Mineralocorticoid receptors dampen glucocorticoid receptor sensitivity to stress via regulation of FKBP5. Cell Rep. 35 , 109185 (2021).

Herrmann, L. et al. Analysis of the cerebellar molecular stress response led to first evidence of a role for FKBP51 in brain FKBP52 expression in mice and humans. Neurobiol. Stress 15 , 100401 (2021).

Young, K. A., Thompson, P. M., Cruz, D. A., Williamson, D. E. & Selemon, L. D. BA11 FKBP5 expression levels correlate with dendritic spine density in postmortem PTSD and controls. Neurobiol. Stress 2 , 67–72 (2015).

Abdallah, C. G. et al. The neurobiology and pharmacotherapy of posttraumatic stress disorder. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 59 , 171–189 (2019).

Watts, B. V. et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy of treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Clin. Psychiatry 74 , e541–e550 (2013).

Krystal, J. H. et al. Adjunctive risperidone treatment for antidepressant-resistant symptoms of chronic military service-related PTSD: a randomized trial. JAMA 306 , 493–502 (2011).

Han, C. et al. The potential role of atypical antipsychotics for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Psychiatr. Res. 56 , 72–81 (2014).

Cipriani, A. et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: a network meta-analysis. Psychol. Med. 48 , 1975–1984 (2018).

Adamou, M., Puchalska, S., Plummer, W. & Hale, A. S. Valproate in the treatment of PTSD: systematic review and meta analysis. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 23 , 1285–1291 (2007).

Andrus, M. R. & Gilbert, E. Treatment of civilian and combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder with topiramate. Ann. Pharmacother. 44 , 1810–1816 (2010).

Hertzberg, M. A. et al. A preliminary study of lamotrigine for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Boil. Psychiatry 45 , 1226–1229 (1999).

Wang, H. R., Woo, Y. S. & Bahk, W. M. Anticonvulsants to treat post-traumatic stress disorder. Hum. Psychopharmacol. 29 , 427–433 (2014).

Davis, L. L. et al. Divalproex in the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in a veteran population. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 28 , 84–88 (2008).

Lindley, S. E., Carlson, E. B. & Hill, K. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of augmentation topiramate for chronic combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 27 , 677–681 (2007).

Taylor, F. B. et al. Prazosin effects on objective sleep measures and clinical symptoms in civilian trauma posttraumatic stress disorder: a placebo-controlled study. Biol. Psychiatry 63 , 629–632 (2008).

Raskind, M. A. et al. A parallel group placebo controlled study of prazosin for trauma nightmares and sleep disturbance in combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Biol. Psychiatry 61 , 928–934 (2007).

Khachatryan, D., Groll, D., Booij, L., Sepehry, A. A. & Schütz, C. G. Prazosin for treating sleep disturbances in adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gen. Hosp. Psychiatry 39 , 46–52 (2016).

Brudey, C. et al. Autonomic and inflammatory consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder and the link to cardiovascular disease. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 309 , R315–R321 (2015).

Raskind, M. A. et al. The alpha1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin ameliorates combat trauma nightmares in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a report of 4 cases. J. Clin. Psychiatry 61 , 129–133 (2000).

Porter-Stransky, K. A. et al. Noradrenergic transmission at alpha1-adrenergic receptors in the ventral periaqueductal gray modulates arousal. Biol. Psychiatry 85 , 237–247 (2019).

Mallick, B. N., Singh, S. & Pal, D. Role of alpha and beta adrenoceptors in locus coeruleus stimulation-induced reduction in rapid eye movement sleep in freely moving rats. Behav. Brain Res. 158 , 9–21 (2005).

Germain, A. et al. Placebo-controlled comparison of prazosin and cognitive-behavioral treatments for sleep disturbances in US Military Veterans. J. Psychosom. Res. 72 , 89–96 (2012).

Raskind, M. A. et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am. J. Psychiatry 170 , 1003–1010 (2013).

Raskind, M. A. et al. Trial of prazosin for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N. Engl. J. Med. 378 , 507–517 (2018).

Dutkiewics, S. Efficacy and tolerability of drugs for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Int. Urol. Nephrol. 32 , 423–432 (2001).

Lewis, C., Roberts, N. P., Andrew, M., Starling, E. & Bisson, J. I. Psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder in adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Psychotraumatol. 11 , 1729633 (2020).

Powers, M. B., Halpern, J. M., Ferenschak, M. P., Gillihan, S. J. & Foa, E. B. A meta-analytic review of prolonged exposure for posttraumatic stress disorder. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 30 , 635–641 (2010).

Pavlov, I. P. & Anrep, G. V. Conditioned Reflexes; An Investigation of the Physiological Activity of the Cerebral Cortex (Oxford Univ. Press, 1927).

Singewald, N., Schmuckermair, C., Whittle, N., Holmes, A. & Ressler, K. J. Pharmacology of cognitive enhancers for exposure-based therapy of fear, anxiety and trauma-related disorders. Pharmacol. Ther. 149 , 150–190 (2015).

Keynan, J. N. et al. Electrical fingerprint of the amygdala guides neurofeedback training for stress resilience. Nat. Hum. Behav. 3 , 63–73 (2019).

Chen, B. K. et al. Sex-specific neurobiological actions of prophylactic (R,S)-ketamine, (2R,6R)-hydroxynorketamine, and (2S,6S)-hydroxynorketamine. Neuropsychopharmacology 45 , 1545–1556 (2020).

Van’t Veer, A. & Carlezon, W. A. Jr. Role of kappa-opioid receptors in stress and anxiety-related behavior. Psychopharmacology 229 , 435–452 (2013).

Smith, A. K. et al. Epigenome-wide meta-analysis of PTSD across 10 military and civilian cohorts identifies methylation changes in AHRR. Nat. Commun. 11 , 5965 (2020).

Mellon, S. H. et al. Metabolomic analysis of male combat veterans with post traumatic stress disorder. PLoS ONE 14 , e0213839 (2019).

Bremner, J. D. Neuroimaging in posttraumatic stress disorder and other stress-related disorders. Neuroimaging Clin. N. Am. 17 , 523–538 (2007).

Britton, J. C., Phan, K. L., Taylor, S. F., Fig, L. M. & Liberzon, I. Corticolimbic blood flow in posttraumatic stress disorder during script-driven imagery. Biol. Psychiatry 57 , 832–840 (2005).

Insel, T. R. The NIMH Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) Project: precision medicine for psychiatry. Am. J. Psychiatry 171 , 395–397 (2014).

Hyman, S. Mental health: depression needs large human-genetics studies. Nature 515 , 189–191 (2014).

Bale, T. L. et al. The critical importance of basic animal research for neuropsychiatric disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology 44 , 1349–1353 (2019).

Baker, J. T., Germine, L. T., Ressler, K. J., Rauch, S. L. & Carlezon, W. A. Jr. Digital devices and continuous telemetry: opportunities for aligning psychiatry and neuroscience. Neuropsychopharmacology 43 , 2499–2503 (2018).

Cakmak, A. S. et al. Classification and prediction of post-trauma outcomes related to PTSD using circadian rhythm changes measured via wrist-worn research watch in a large longitudinal cohort. IEEE J. Biomed. Health Inf. 25 , 2866–2876 (2021).

Tsanas, A., Woodward, E. & Ehlers, A. Objective characterization of activity, sleep, and circadian rhythm patterns using a wrist-worn actigraphy sensor: insights into posttraumatic stress disorder. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 8 , e14306 (2020).

Thompson, R. S. et al. Repeated fear-induced diurnal rhythm disruptions predict PTSD-like sensitized physiological acute stress responses in F344 rats. Acta Physiol. 211 , 447–465 (2014).

Phillips, A. G., Geyer, M. A. & Robbins, T. W. Effective use of animal models for therapeutic development in psychiatric and substance use disorders. Biol. Psychiatry 83 , 915–923 (2018).

Van’t Veer, A., Yano, J. M., Carroll, F. I., Cohen, B. M. & Carlezon, W. A. Jr. Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF)-induced disruption of attention in rats is blocked by the kappa-opioid receptor antagonist JDTic. Neuropsychopharmacology 37 , 2809–2816 (2012).

Vogel, S. C. et al. Childhood adversity and dimensional variations in adult sustained attention. Front. Psychol. 11 , 691 (2020).

White, S. F. et al. Increased cognitive control and reduced emotional interference is associated with reduced PTSD symptom severity in a trauma-exposed sample: a preliminary longitudinal study. Psychiatry Res. Neuroimaging 278 , 7–12 (2018).

Beard, C. et al. Abnormal error processing in depressive states: a translational examination in humans and rats. Transl. Psychiatry 5 , e564 (2015).

Robble, M. A. et al. Concordant neurophysiological signatures of cognitive control in humans and rats. Neuropsychopharmacology 46 , 1252–1262 (2021).

Der-Avakian, A. et al. Social defeat disrupts reward learning and potentiates striatal nociceptin/orphanin FQ mRNA in rats. Psychopharmacology 234 , 1603–1614 (2017).

Lokshina, Y., Nickelsen, T. & Liberzon, I. Reward processing and circuit dysregulation in posttraumatic stress disorder. Front. Psychiatry 12 , 559401 (2021).

Lori, A. et al. Transcriptome-wide association study of post-trauma symptom trajectories identified GRIN3B as a potential biomarker for PTSD development. Neuropsychopharmacology 46 , 1811–1820 (2021).

Pacella, M. L., Hruska, B., Steudte-Schmiedgen, S., George, R. L. & Delahanty, D. L. The utility of hair cortisol concentrations in the prediction of PTSD symptoms following traumatic physical injury. Soc. Sci. Med. 175 , 228–234 (2017).

McCullough, K. M. et al. Genome-wide translational profiling of amygdala Crh-expressing neurons reveals role for CREB in fear extinction learning. Nat. Commun. 11 , 5180 (2020).

Boyden, E. S., Zhang, F., Bamberg, E., Nagel, G. & Deisseroth, K. Millisecond-timescale, genetically targeted optical control of neural activity. Nat. Neurosci. 8 , 1263–1268 (2005).

Zhang, F. et al. Multimodal fast optical interrogation of neural circuitry. Nature 446 , 633–639 (2007).

Chow, B. Y. et al. High-performance genetically targetable optical neural silencing by light-driven proton pumps. Nature 463 , 98–102 (2010).

Han, X. et al. A high-light sensitivity optical neural silencer: development and application to optogenetic control of non-human primate cortex. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 5 , 18 (2011).

Luchkina, N. V. & Bolshakov, V. Y. Diminishing fear: optogenetic approach toward understanding neural circuits of fear control. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 174 , 64–79 (2018).

Gradinaru, V. et al. Molecular and cellular approaches for diversifying and extending optogenetics. Cell 141 , 154–165 (2010).

Coward, P. et al. Controlling signaling with a specifically designed Gi-coupled receptor. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95 , 352–357 (1998).

Dong, S., Rogan, S. C. & Roth, B. L. Directed molecular evolution of DREADDs: a generic approach to creating next-generation RASSLs. Nat. Protoc. 5 , 561–573 (2010).

Roth, B. L. DREADDs for neuroscientists. Neuron 89 , 683–694 (2016).

Lin, M. Z. & Schnitzer, M. J. Genetically encoded indicators of neuronal activity. Nat. Neurosci. 19 , 1142–1153 (2016).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NIH awards P50-MH115874 (to W.C./K.J.R.), R01-MH108665 (to K.J.R.), R01-MH063266 (to W.C.), R01-MH123993 (to V.Y.B.), and the Frazier Institute at McLean Hospital (to K.J.R.). I.R. was partially supported by (R01-MH120400).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

SPARED Center, Department of Psychiatry, McLean Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA

Kerry. J. Ressler, Sabina Berretta, Vadim Y. Bolshakov, Isabelle M. Rosso, Edward G. Meloni, Scott L. Rauch & William A. Carlezon Jr

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

The authors contributed equally to all aspects of the article.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Kerry. J. Ressler .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

K.J.R. has received consulting income from Alkermes, Bionomics, Bioxcel and Jazz Pharmaceuticals, and is on scientific advisory boards for the Army STARRS Project, Janssen, the National Center for PTSD, Sage Therapeutics and Verily. He has also received sponsored research support from Brainsway and Takeda. He also serves on the Boards of ACNP and Biological Psychiatry. W.C. has received consulting income from Psy Therapeutics and has a sponsored research agreement with Cerevel Therapeutics. He is the editor-in-chief for Neuropsychopharmacology and serves on the board of ACNP. None of this work is directly related to the work presented here. S.L.R. receives compensation as a Board member of Community Psychiatry and for his role as Secretary of SOBP. He also serves on the Boards of ADAA and NNDC. He has received royalties from Oxford University Press and APPI.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Reviews Neurology thanks Matthew Girgenti, Soraya Seedat and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

A core feature of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that includes irritability, panic and disruptions in sleep and cognitive function.

A reflex that occurs rapidly and unconsciously in response to an external stimulus such as a noise burst.

A core feature of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) characterized by a heightened state of active threat assessment.

A method of inducing alterations in gene expression involving the ability of the enzyme Cre-recombinase to induce site-specific recombination of genetic material.

A theoretical representation of a neural unit of memory storage.

A muscle located in the eyelid, activity of which is often an end point in human fear conditioning research.

Secondary phenotypes that reliably co-occur as a sub-feature of a broader primary phenotype.

Two or more biological processes that are modulated (activated, suppressed) in parallel by a common upstream factor.

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Ressler, K.J., Berretta, S., Bolshakov, V.Y. et al. Post-traumatic stress disorder: clinical and translational neuroscience from cells to circuits. Nat Rev Neurol 18 , 273–288 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-022-00635-8

Download citation

Accepted : 18 February 2022

Published : 29 March 2022

Issue Date : May 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-022-00635-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Spatiotemporal dynamics of hippocampal-cortical networks underlying the unique phenomenological properties of trauma-related intrusive memories.

- Kevin J. Clancy

- Quentin Devignes

- Isabelle M. Rosso

Molecular Psychiatry (2024)

Trauma-related intrusive memories and anterior hippocampus structural covariance: an ecological momentary assessment study in posttraumatic stress disorder

Translational Psychiatry (2024)

Advancing preclinical chronic stress models to promote therapeutic discovery for human stress disorders

- Trevonn M. Gyles

- Eric J. Nestler

- Eric M. Parise

Neuropsychopharmacology (2024)

Differential effects of the stress peptides PACAP and CRF on sleep architecture in mice

- Allison R. Foilb

- Elisa M. Taylor-Yeremeeva

- William A. Carlezon

NPP—Digital Psychiatry and Neuroscience (2024)

Memory persistence: from fundamental mechanisms to translational opportunities

- Santiago Abel Merlo

- Mariano Andrés Belluscio

- Emiliano Merlo

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Translational Research newsletter — top stories in biotechnology, drug discovery and pharma.

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

A brief treatment for veterans with ptsd: an open-label case-series study.

- 1 Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 2 Work Health Technology, The Netherlands Organization for Applied Scientific Research TNO, Leiden, Netherlands

Introduction: Despite the positive outcomes observed in numerous individuals undergoing trauma-focused psychotherapy for PTSD, veterans with this condition experience notably diminished advantages from such therapeutic interventions in comparison to non-military populations.

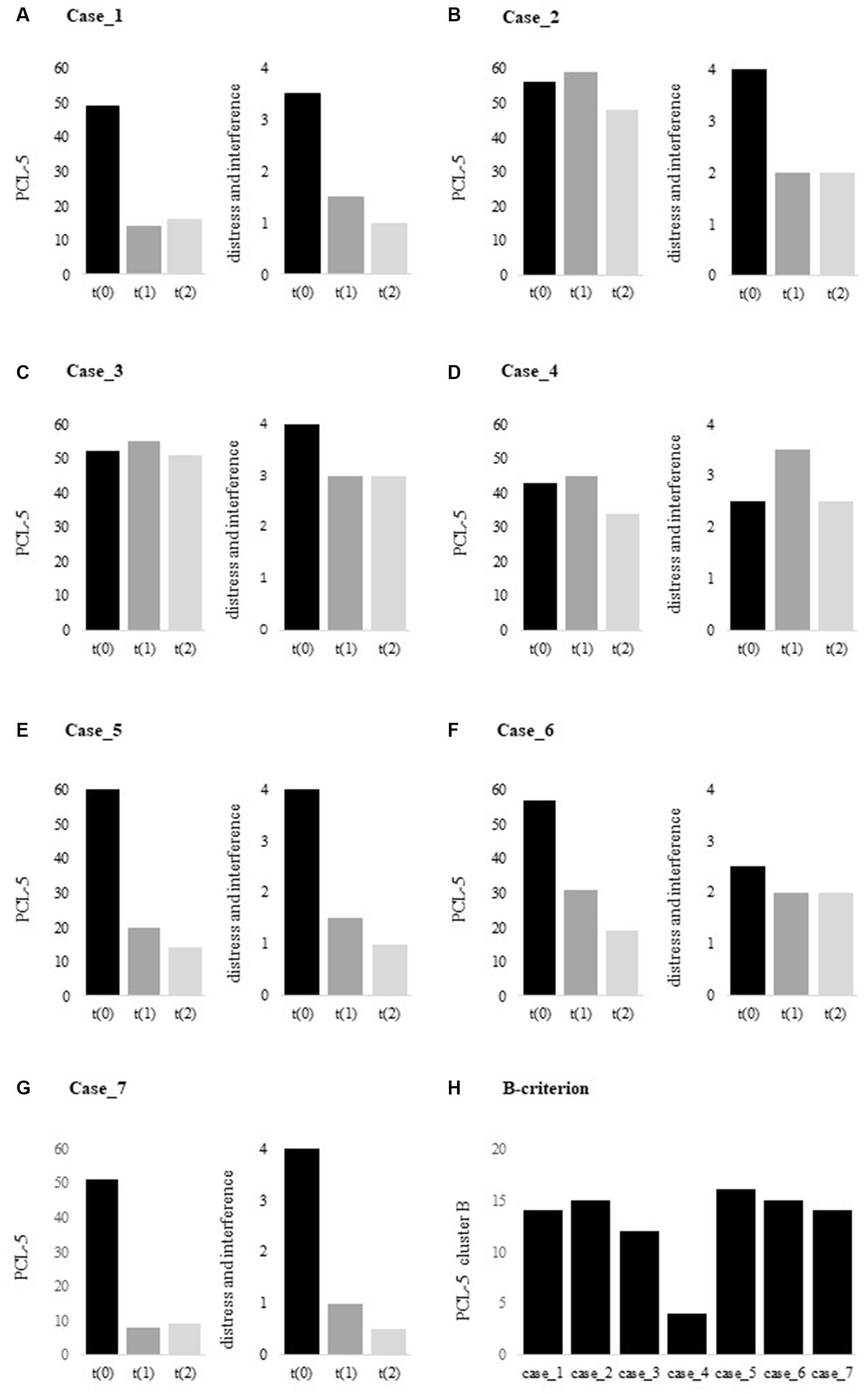

Methods: In a preliminary study we investigated the efficacy of an innovative treatment approach in a small sample of veterans ( n = 7). Recognizing that accessing and targeting trauma memory in veterans with PTSD may be more challenging compared to other patient populations, we employed unique and personalized retrieval cues that engaged multiple senses and were connected to the context of their trauma. This was followed by a session focused on memory reconsolidation, which incorporated both psychological techniques (i.e., imagery rescripting) and a pharmacological component (i.e., 40 mg of propranolol).

Results: The findings from this small-scale case series cautiously indicate that this brief intervention, typically consisting of only one or two treatment sessions, shows promise in producing significant effects on symptoms of PTSD, distress and quality of life.This is particularly noteworthy given the complex symptomatology experienced by the veterans in this study.

Conclusion: To summarize, there are grounds for optimism regarding this brief treatment of combat-related PTSD. It appears that the potential for positive outcomes is far greater than commonly believed, as demonstrated by the encouraging results of this pilot study.

1. Introduction

The concept that soldiers are tormented by the haunting memories of their wartime ordeals is a recurring theme that echoes through the ages, from the epic verses of Homer’s Iliad, the poetic prose of Shakespeare to the poignant pages of Tolstoy’s ‘war and peace’. Soldiers who were exposed to the trauma of war often experienced a range of symptoms, including anxiety, depression, nightmares, flashbacks, and physical symptoms such as shaking and trembling. Labeling these symptoms as the shell shock syndrome in military personnel during World War I was a significant milestone in the recognition of trauma and its effects on mental health. Initially, these symptoms were often dismissed as signs of weakness or cowardice, and soldiers were sometimes even accused of faking their symptoms to avoid combat. The recognition of shell shock and the subsequent establishment of PTSD as a diagnosis in 1980 (DSM-II) has spurred the creation of effective treatments that have helped many individuals attain recovery and lead satisfying lives. Still, PTSD in past and present members of the military tends to be a chronic condition with prevalence rates varying between 3 and 17% ( 1 – 3 ). Around 80% of those with a diagnosis of PTSD also meets criteria for another mental health condition such as depression, substance use disorder, or another anxiety disorder ( 4 ). While trauma-focused psychotherapy 1 may yield positive results for many individuals suffering from PTSD, veterans with PTSD benefit significantly less than non-military populations ( 5 – 8 ). After receiving trauma-focused psychotherapy for combat-related PTSD, approximately two-thirds of veterans still experience the lingering consequences of this disorder ( 7 , 9 ). Another challenge arises as a considerable number of veterans prematurely end their treatment with dropout rates ranging from 25 to 48% ( 9 , 10 ). Notwithstanding the advances in the field, it is increasingly evident that PTSD continues to be a complex and daunting condition for military personnel and veterans, posing formidable obstacles for traditional trauma-focused psychotherapies. Here, we examine the effectiveness of a novel treatment approach with the goal of mitigating the problem of treatment resistance and the high rates of dropout commonly observed in veterans.

Prior to delving into the details of our innovative treatment approach, we propose several plausible explanations that could clarify the relatively lower effectiveness of trauma-focused interventions in treating veterans with PTSD. Considering that PTSD is viewed as a disturbance of emotional memory (e.g., 11 , 12 ), most psychotherapeutic approaches concentrate on exploring and addressing the individual’s recollection of the traumatic event or its meaning. Regardless of the specific therapeutic approach employed, they all involve revisiting the most distressing and agonizing memories associated with the traumatic experience. These memories, commonly referred to as “hotspot memories” and identified through the intrusive symptoms they elicit, serve as the basis for therapy ( 13 – 17 ). Successful reliving of these memories requires a focus on the sensory details and emotional responses that are integral to the memory ( 12 , 18 , 19 ). While perceptual memory reactivation may not be essential for reducing symptoms, it may facilitate a shift in meaning that ultimately predicts improved treatment outcomes ( 20 ). The general procedure to reactivate trauma memory is to instruct patients to imagine or describe the most disturbing traumatic situations, or the situation that is related to their hotspot memories. Yet, deliberately reliving the battlefield within a therapeutic context does not always guarantee easy access to the emotional intensity of the experience. We must not overlook the fact that military personnel undergo extensive training to equip them with the necessary skills to withstand the arduous physical and mental challenges inherent in their duties. Since emotions such as fear, anger, and sadness can have a significant impact on decision-making and performance in high-stress situations, military training often includes instruction on how to regulate and control their emotions while on duty. Hence, the efficacy of established trauma-focused therapies in evoking a deeply moving emotional response when recalling trauma memories in veterans might pose greater challenges compared to non-military individuals with PTSD. Pinpointing the per-symptom effectiveness of treatments in uncontrolled clinical settings in Israel indeed showed that only a small number of veterans (15.8%, n = 709) experienced minimal relief from symptoms of intrusive traumatic reexperiencing, while two other mnemonic symptoms, namely flashbacks and inability to recall an important aspect of the trauma, exhibited no response to treatment at all in this group of veterans ( 21 ). It is important to mention that not all veterans received trauma-focused therapy in this study. Nonetheless, the failure to effectively address these mnemonic symptoms in veterans may perpetuate other features of the disorder as well ( 21 ).

Another potential limitation is that current therapies were originally designed to address the excessive fear responses to trauma reminders, rather than the multifaceted emotions that may be present in military-related PTSD. Feelings of sadness, anger, shame, guilt, a sense of powerlessness, and betrayal are all common experiences that people may experience when being exposed to trauma ( 22 ). These feelings are particularly intense for members of the military who are often confronted with demanding ethical or moral decisions during their service ( 23 ). While decision-making is often likely to be consistent with their military codes of conduct, substantial levels of psychological distress can still be experienced when they perpetrate, witness or fail to prevent actions that run counter to their core moral or ethical values ( 24 ). This elevated state of distress is identified as ‘moral injury’, a condition closely linked to feelings of guilt, anger and shame ( 25 , 26 ). As a result, individuals with combat-related trauma may not fully benefit from existing treatments, as their emotional needs remain unaddressed. When it comes to addressing the needs of military personnel dealing with PTSD, it’s also essential to consider the emotional toll that therapy can take on veterans. Most trauma-focused therapies require a prolonged course of treatment, which can be emotionally very taxing for military personnel. It is promising though that a recent study has shown a correlation between massed exposure therapy, which consists of delivering a full treatment program over a shorter duration, and a decrease in the number of veterans who discontinue the treatment ( 9 ). Hence, to truly develop more comprehensive and effective treatments for military-related PTSD, further research is necessary to better understand the emotional needs of veterans.

As an initial attempt to overcome the limitations of existing treatments for PTSD, we have developed a novel and concise intervention tailored to combat-related trauma. While most therapies rely on visual and verbal retrieval cues to access emotional memory, we believe that the use of multi-sensory and context-related stimuli as retrieval aids has been surprisingly underutilized. For instance, odors similar to the trauma context could be particularly powerful cues to spontaneously evoke autobiographical memories with a strong emotional resonance ( 27 – 31 ). One advantage of utilizing odors as retrieval cues is that the brain regions involved in olfaction have direct connections to the amygdala and entorhinal cortex ( 32 , 33 ), both of which are involved in emotion processing and memory. To enhance access to emotional memory, we developed idiosyncratic virtual reality worlds that incorporate multi-sensory retrieval cues, including 3D visual, auditory, olfactory, and bodily information, tailored as much as possible to everyone’s personal experiences. After this brief memory reactivation procedure (i.e., 2 min), the focus was shifted toward the idiosyncratic memory representation of the veteran. On the basis of information provided in the intake we had formulated hypothesized stuck points that we tried to directly target in treatment. This part consisted of imaginal exposure combined with rescripting with the rationale that new perspectives on what happened during trauma are most effectively achieved by experiencing new views and emotions which were not possible at the time of the trauma ( 17 , 34 , 35 ). In a previous randomized-controlled trial in nonmilitary-related PTSD, we demonstrated that the addition of imagery rescripting to imaginary exposure led to a significant reduction of treatment dropouts, and better effects on guilt, anger and shame as compared to exposure alone ( 34 ).

Finally, a pivotal modification in the current intervention was to utilize the process of memory reconsolidation as an alternative means of inducing change. Most trauma-focused therapies are rooted on extinction learning with the notable limitation that it can only eliminate the fearful responding while leaving the original trauma memory intact ( 36 , 37 ). As a consequence, the intact trauma memory may resurface thereby explaining the relatively high relapse rates even after initial treatment success ( 38 , 39 ). In contrast, the hypothesis of memory reconsolidation suggests that it may be possible to target the trauma memory directly, with the promise of an instantaneous and more persistent alleviation of symptoms. Memory reconsolidation refers to the process that upon memory retrieval, items in long-term memory may temporarily return into a labile state requiring de novo protein synthesis in order to persist ( 40 ). This cascade of neurobiological processes offers a window of opportunity for targeting fear memories with amnestic agents. The crucial role of central noradrenergic signaling in the process cascade ( 41 ) suggests that the β-adrenergic blocker propranolol is a viable option for effectively interfering with memory reconsolidation in humans. Indeed, preclinical research has compellingly shown that β-adrenergic blockade during reconsolidation can disrupt fear memories in healthy individuals (e.g., ( 42 ); see for a review ( 43 )) and in people with a fear of spiders (( 44 , 45 ); but (see 46 )). Even though these findings point to a revolutionary new treatment for emotional memory disorders, the success of reconsolidation interventions is not guaranteed ( 47 ). The effect of the intervention depends on whether memory retrieval effectively triggers reconsolidation. Only if the retrieval experience contains novel or unexpected information (i.e., prediction error), the memory engram will be destabilized ( 48 , 49 ). While clinical research in patients with PTSD initially revealed a reduction in fear responding following a reconsolidation intervention ( 17 , 50 – 52 ), these findings could not always be replicated in several follow-up trials (( 53 ); see for a review ( 54 )). It is worth highlighting that the design of these previous clinical trials raises several questions with respect to the necessary conditions for a reconsolidation intervention. The effectiveness of this intervention hinges on two key conditions: (i) the retrieval procedure should lead to the destabilization of the trauma memory, and (ii) the amnestic drug should interfere with the subsequent reconsolidation of that fear memory ( 43 ). In previous clinical trials, script-driven imagery was employed to reactivate traumatic memories, despite the fact that this method was explicitly designed to assess the passive retrieval of these memories, rather than their reconsolidation. Additionally, the timing of drug administration in these clinical trials (specifically, the use of long-acting propranolol after the reactivation of the traumatic memory) does not align with the reconsolidation hypothesis. We carried out a series of experiments aimed at exploring the optimal timing for administering propranolol. Our findings revealed a rather narrow temporal window, spanning less than four hours following memory reactivation, during which the β-adrenergic receptors assume a pivotal role in the reconsolidation of fear memories ( 47 , 55 ).In summary, unlike traditional trauma-focused interventions that require multiple sessions with gradual and often temporary improvements, the memory reconsolidation intervention (i.e., Memrec) offers an unique approach to treating combat-related PTSD by providing a single, possibly effective treatment session that results in a sudden reduction in emotional symptoms. This innovative treatment approach also represents a departure from the conventional use of pharmaceutical agents to alleviate PTSD symptoms, as it involves a one-time administration of a very common drug (i.e., 40 mg propranolol HCl) after reliving and rescripting the combat-related trauma memory. In the current case series involving seven veterans we tested the effectiveness of Memrec for trauma in which we aimed to address the unparalleled complexities that are typically associated with treating combat-related PTSD.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. participants.

Participants were combat-exposed Dutch military veterans referred for treatment at ARQ Centrum ‘45, the Dutch national center for diagnostics and treatment of patients with long-lasting trauma-related disorders. Inclusion criteria were (a) aged between 18–65 years, and (b) a diagnosis of PTSD based on the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS-5) ( 56 ). The exclusion criteria included (a) any other relevant treatment for PTSD within 3 months before the start of the study, (b) start of new psychotropic medication within 3 months before the start of the study – medication used for longer periods could be continued, (c) life-time psychosis, (d) acute suicide risk, and (e) any contra-indications for the use of propranolol. All participants gave written informed consent, and the protocol was approved by the Medical-Ethical Committee of the Amsterdam UMC.

2.2. Outcome measures

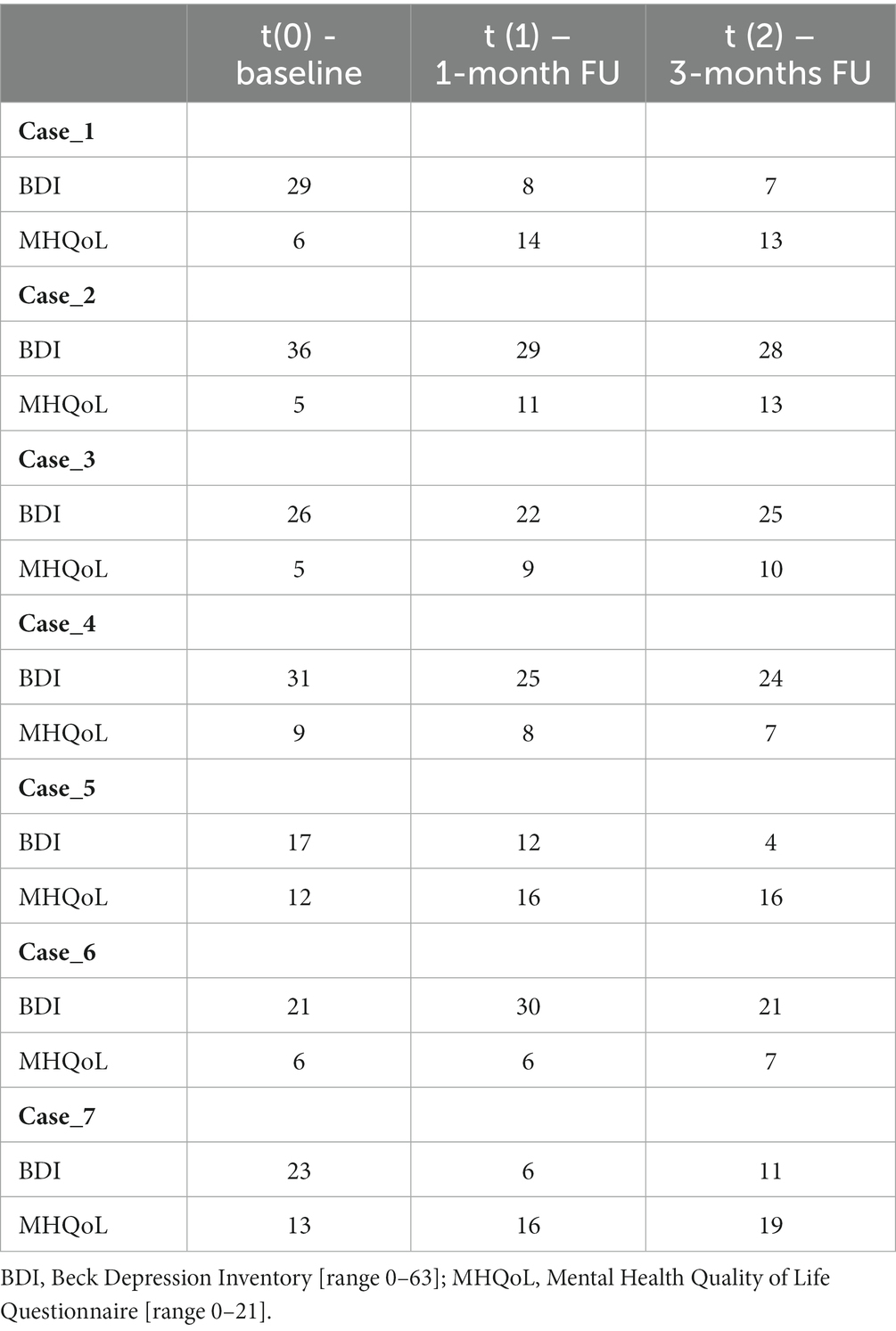

The following measures were completed pre-treatment, as well as 1-month and 3-months post-intervention.

2.2.1. PTSD checklist for DSM-5

The PCL-5 is a 20-item self-report measures that assesses the 20 DSM-5 symptoms of PTSD ( 57 ), and can be used to monitor symptom change, to screen for PTSD, or to make a provisional PTSD diagnosis. Respondents rate each item from 0 = “not at all” to 4 = “extremely” to indicate the degree to which they have been bothered by that particular symptom over the past month. A total symptom severity score can be obtained by summing the scores for each of the 20 items, range = 0–80. DSM-5 symptom cluster severity scores can be obtained by summing the scores for the items within a given cluster, i.e., cluster B = items 1–5, cluster C = items 6–7, cluster D = items 8–14, and cluster E = items 15–20. A PCL-5 cut-off score between 31–33 is considered indicative of PTSD ( 58 ). Evidence suggests that a 15–20 point change represents a clinically significant change ( 59 ). The PCL-5 is a psychometrically sound instrument that can be used effectively with veterans ( 58 , 60 ). An additional item was added to the PCL-5 to ask about distress and interference caused by PTSD symptoms on a 5-point scale of frequency and severity ranging from 0 = “not at all” to 4 = “6 or more times a week” ( 61 ).