- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- Diet & Nutrition

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

What Is Breech?

When a fetus is delivered buttocks or feet first

- Types of Presentation

Risk Factors

Complications.

Breech concerns the position of the fetus before labor . Typically, the fetus comes out headfirst, but in a breech delivery, the buttocks or feet come out first. This type of delivery is risky for both the pregnant person and the fetus.

This article discusses the different types of breech presentations, risk factors that might make a breech presentation more likely, treatment options, and complications associated with a breech delivery.

Verywell / Jessica Olah

Types of Breech Presentation

During the last few weeks of pregnancy, a fetus usually rotates so that the head is positioned downward to come out of the vagina first. This is called the vertex position.

In a breech presentation, the fetus does not turn to lie in the correct position. Instead, the fetus’s buttocks or feet are positioned to come out of the vagina first.

At 28 weeks of gestation, approximately 20% of fetuses are in a breech position. However, the majority of these rotate to the proper vertex position. At full term, around 3%–4% of births are breech.

The different types of breech presentations include:

- Complete : The fetus’s knees are bent, and the buttocks are presenting first.

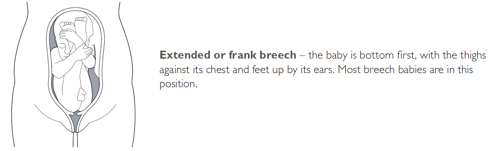

- Frank : The fetus’s legs are stretched upward toward the head, and the buttocks are presenting first.

- Footling : The fetus’s foot is showing first.

Signs of Breech

There are no specific symptoms associated with a breech presentation.

Diagnosing breech before the last few weeks of pregnancy is not helpful, since the fetus is likely to turn to the proper vertex position before 35 weeks gestation.

A healthcare provider may be able to tell which direction the fetus is facing by touching a pregnant person’s abdomen. However, an ultrasound examination is the best way to determine how the fetus is lying in the uterus.

Most breech presentations are not related to any specific risk factor. However, certain circumstances can increase the risk for breech presentation.

These can include:

- Previous pregnancies

- Multiple fetuses in the uterus

- An abnormally shaped uterus

- Uterine fibroids , which are noncancerous growths of the uterus that usually appear during the childbearing years

- Placenta previa, a condition in which the placenta covers the opening to the uterus

- Preterm labor or prematurity of the fetus

- Too much or too little amniotic fluid (the liquid that surrounds the fetus during pregnancy)

- Fetal congenital abnormalities

Most fetuses that are breech are born by cesarean delivery (cesarean section or C-section), a surgical procedure in which the baby is born through an incision in the pregnant person’s abdomen.

In rare instances, a healthcare provider may plan a vaginal birth of a breech fetus. However, there are more risks associated with this type of delivery than there are with cesarean delivery.

Before cesarean delivery, a healthcare provider might utilize the external cephalic version (ECV) procedure to turn the fetus so that the head is down and in the vertex position. This procedure involves pushing on the pregnant person’s belly to turn the fetus while viewing the maneuvers on an ultrasound. This can be an uncomfortable procedure, and it is usually done around 37 weeks gestation.

ECV reduces the risks associated with having a cesarean delivery. It is successful approximately 40%–60% of the time. The procedure cannot be done once a pregnant person is in active labor.

Complications related to ECV are low and include the placenta tearing away from the uterine lining, changes in the fetus’s heart rate, and preterm labor.

ECV is usually not recommended if the:

- Pregnant person is carrying more than one fetus

- Placenta is in the wrong place

- Healthcare provider has concerns about the health of the fetus

- Pregnant person has specific abnormalities of the reproductive system

Recommendations for Previous C-Sections

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) says that ECV can be considered if a person has had a previous cesarean delivery.

During a breech delivery, the umbilical cord might come out first and be pinched by the exiting fetus. This is called cord prolapse and puts the fetus at risk for decreased oxygen and blood flow. There’s also a risk that the fetus’s head or shoulders will get stuck inside the mother’s pelvis, leading to suffocation.

Complications associated with cesarean delivery include infection, bleeding, injury to other internal organs, and problems with future pregnancies.

A healthcare provider needs to weigh the risks and benefits of ECV, delivering a breech fetus vaginally, and cesarean delivery.

In a breech delivery, the fetus comes out buttocks or feet first rather than headfirst (vertex), the preferred and usual method. This type of delivery can be more dangerous than a vertex delivery and lead to complications. If your baby is in breech, your healthcare provider will likely recommend a C-section.

A Word From Verywell

Knowing that your baby is in the wrong position and that you may be facing a breech delivery can be extremely stressful. However, most fetuses turn to have their head down before a person goes into labor. It is not a cause for concern if your fetus is breech before 36 weeks. It is common for the fetus to move around in many different positions before that time.

At the end of your pregnancy, if your fetus is in a breech position, your healthcare provider can perform maneuvers to turn the fetus around. If these maneuvers are unsuccessful or not appropriate for your situation, cesarean delivery is most often recommended. Discussing all of these options in advance can help you feel prepared should you be faced with a breech delivery.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. If your baby is breech .

TeachMeObGyn. Breech presentation .

MedlinePlus. Breech birth .

Hofmeyr GJ, Kulier R, West HM. External cephalic version for breech presentation at term . Cochrane Database Syst Rev . 2015 Apr 1;2015(4):CD000083. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000083.pub3

By Christine Zink, MD Dr. Zink is a board-certified emergency medicine physician with expertise in the wilderness and global medicine.

- Screening & Prevention

- Sexual Health & Relationships

- Birth Control

- Preparing for Surgery Checklist

- Healthy Teens

- Getting Pregnant

- During Pregnancy

- Labor and Delivery

- After Pregnancy

- Pregnancy Book

- Mental Health

- Prenatal Testing

- Menstrual Health

- Heart Health

- Special Procedures

- Diseases and Conditions

- Browse All Topics

- View All Frequently Asked Questions

Read common questions on the coronavirus and ACOG’s evidence-based answers.

If Your Baby Is Breech

URL has been copied to the clipboard

Frequently Asked Questions Expand All

In the last weeks of pregnancy, a fetus usually moves so his or her head is positioned to come out of the vagina first during birth. This is called a vertex presentation . A breech presentation occurs when the fetus’s buttocks, feet, or both are in place to come out first during birth. This happens in 3–4% of full-term births.

It is not always known why a fetus is breech. Some factors that may contribute to a fetus being in a breech presentation include the following:

You have been pregnant before.

There is more than one fetus in the uterus (twins or more).

There is too much or too little amniotic fluid .

The uterus is not normal in shape or has abnormal growths such as fibroids .

The placenta covers all or part of the opening of the uterus ( placenta previa )

The fetus is preterm .

Occasionally fetuses with certain birth defects will not turn into the head-down position before birth. However, most fetuses in a breech presentation are otherwise normal.

Your health care professional may be able to tell which way your fetus is facing by placing his or her hands at certain points on your abdomen. By feeling where the fetus's head, back, and buttocks are, it may be possible to find out what part of the fetus is presenting first. An ultrasound exam or pelvic exam may be used to confirm it.

External cephalic version (ECV) is an attempt to turn the fetus so that he or she is head down. ECV can improve your chance of having a vaginal birth. If the fetus is breech and your pregnancy is greater than 36 weeks your health care professional may suggest ECV.

ECV will not be tried if:

You are carrying more than one fetus

There are concerns about the health of the fetus

You have certain abnormalities of the reproductive system

The placenta is in the wrong place

The placenta has come away from the wall of the uterus ( placental abruption )

ECV can be considered if you have had a previous cesarean delivery .

The health care professional performs ECV by placing his or her hands on your abdomen. Firm pressure is applied to the abdomen so that the fetus rolls into a head-down position. Two people may be needed to perform ECV. Ultrasound also may be used to help guide the turning.

The fetus's heart rate is checked with fetal monitoring before and after ECV. If any problems arise with you or the fetus, ECV will be stopped right away. ECV usually is done near a delivery room. If a problem occurs, a cesarean delivery can be performed quickly, if necessary.

Complications may include the following:

Prelabor rupture of membranes

Changes in the fetus's heart rate

Placental abruption

Preterm labor

More than one half of attempts at ECV succeed. However, some fetuses who are successfully turned with ECV move back into a breech presentation. If this happens, ECV may be tried again. ECV tends to be harder to do as the time for birth gets closer. As the fetus grows bigger, there is less room for him or her to move.

Most fetuses that are breech are born by planned cesarean delivery. A planned vaginal birth of a single breech fetus may be considered in some situations. Both vaginal birth and cesarean birth carry certain risks when a fetus is breech. However, the risk of complications is higher with a planned vaginal delivery than with a planned cesarean delivery.

In a breech presentation, the body comes out first, leaving the baby’s head to be delivered last. The baby’s body may not stretch the cervix enough to allow room for the baby’s head to come out easily. There is a risk that the baby’s head or shoulders may become wedged against the bones of the mother’s pelvis. Another problem that can happen during a vaginal breech birth is a prolapsed umbilical cord . It can slip into the vagina before the baby is delivered. If there is pressure put on the cord or it becomes pinched, it can decrease the flow of blood and oxygen through the cord to the baby.

Although a planned cesarean birth is the most common way that breech fetuses are born, there may be reasons to try to avoid a cesarean birth.

A cesarean delivery is major surgery. Complications may include infection, bleeding, or injury to internal organs.

The type of anesthesia used sometimes causes problems.

Having a cesarean delivery also can lead to serious problems in future pregnancies, such as rupture of the uterus and complications with the placenta.

With each cesarean delivery, these risks increase.

If you are thinking about having a vaginal birth and your fetus is breech, your health care professional will review the risks and benefits of vaginal birth and cesarean birth in detail. You usually need to meet certain guidelines specific to your hospital. The experience of your health care professional in delivering breech babies vaginally also is an important factor.

Amniotic Fluid : Fluid in the sac that holds the fetus.

Anesthesia : Relief of pain by loss of sensation.

Breech Presentation : A position in which the feet or buttocks of the fetus would appear first during birth.

Cervix : The lower, narrow end of the uterus at the top of the vagina.

Cesarean Delivery : Delivery of a fetus from the uterus through an incision made in the woman’s abdomen.

External Cephalic Version (ECV) : A technique, performed late in pregnancy, in which the doctor attempts to manually move a breech baby into the head-down position.

Fetus : The stage of human development beyond 8 completed weeks after fertilization.

Fibroids : Growths that form in the muscle of the uterus. Fibroids usually are noncancerous.

Oxygen : An element that we breathe in to sustain life.

Pelvic Exam : A physical examination of a woman’s pelvic organs.

Placenta : Tissue that provides nourishment to and takes waste away from the fetus.

Placenta Previa : A condition in which the placenta covers the opening of the uterus.

Placental Abruption : A condition in which the placenta has begun to separate from the uterus before the fetus is born.

Prelabor Rupture of Membranes : Rupture of the amniotic membranes that happens before labor begins. Also called premature rupture of membranes (PROM).

Preterm : Less than 37 weeks of pregnancy.

Ultrasound Exam : A test in which sound waves are used to examine inner parts of the body. During pregnancy, ultrasound can be used to check the fetus.

Umbilical Cord : A cord-like structure containing blood vessels. It connects the fetus to the placenta.

Uterus : A muscular organ in the female pelvis. During pregnancy, this organ holds and nourishes the fetus.

Vagina : A tube-like structure surrounded by muscles. The vagina leads from the uterus to the outside of the body.

Vertex Presentation : A presentation of the fetus where the head is positioned down.

Article continues below

Advertisement

If you have further questions, contact your ob-gyn.

Don't have an ob-gyn? Learn how to find a doctor near you .

Published: January 2019

Last reviewed: August 2022

Copyright 2024 by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. All rights reserved. Read copyright and permissions information . This information is designed as an educational aid for the public. It offers current information and opinions related to women's health. It is not intended as a statement of the standard of care. It does not explain all of the proper treatments or methods of care. It is not a substitute for the advice of a physician. Read ACOG’s complete disclaimer .

Clinicians: Subscribe to Digital Pamphlets

Explore ACOG's library of patient education pamphlets.

A Guide to Pregnancy from Ob-Gyns

For trusted, in-depth advice from ob-gyns, turn to Your Pregnancy and Childbirth: Month to Month.

ACOG Explains

A quick and easy way to learn more about your health.

What to Read Next

Cesarean Birth

Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring During Labor

What is back labor?

What is delayed cord clamping?

- Search Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Sweepstakes

- Labor & Delivery

What Causes Breech Presentation?

Learn more about the types, causes, and risks of breech presentation, along with how breech babies are typically delivered.

What Is Breech Presentation?

Types of breech presentation, what causes a breech baby, can you turn a breech baby, how are breech babies delivered.

FatCamera/Getty Images

Toward the end of pregnancy, your baby will start to get into position for delivery, with their head pointed down toward the vagina. This is otherwise known as vertex presentation. However, some babies turn inside the womb so that their feet or buttocks are poised to be delivered first, which is commonly referred to as breech presentation, or a breech baby.

As you near the end of your pregnancy journey, an OB-GYN or health care provider will check your baby's positioning. You might find yourself wondering: What causes breech presentation? Are there risks involved? And how are breech babies delivered? We turned to experts and research to answer some of the most common questions surrounding breech presentation, along with what causes this positioning in the first place.

During your pregnancy, your baby constantly moves around the uterus. Indeed, most babies do somersaults up until the 36th week of pregnancy , when they pick their final position in the womb, says Laura Riley , MD, an OB-GYN in New York City. Approximately 3-4% of babies end up “upside-down” in breech presentation, with their feet or buttocks near the cervix.

Breech presentation is typically diagnosed during a visit to an OB-GYN, midwife, or health care provider. Your physician can feel the position of your baby's head through your abdominal wall—or they can conduct a vaginal exam if your cervix is open. A suspected breech presentation should ultimately be confirmed via an ultrasound, after which you and your provider would have a discussion about delivery options, potential issues, and risks.

There are three types of breech babies: frank, footling, and complete. Learn about the differences between these breech presentations.

Frank Breech

With frank breech presentation, your baby’s bottom faces the cervix and their legs are straight up. This is the most common type of breech presentation.

Footling Breech

Like its name suggests, a footling breech is when one (single footling) or both (double footling) of the baby's feet are in the birth canal, where they’re positioned to be delivered first .

Complete Breech

In a complete breech presentation, baby’s bottom faces the cervix. Their legs are bent at the knees, and their feet are near their bottom. A complete breech is the least common type of breech presentation.

Other Types of Mal Presentations

The baby can also be in a transverse position, meaning that they're sideways in the uterus. Another type is called oblique presentation, which means they're pointing toward one of the pregnant person’s hips.

Typically, your baby's positioning is determined by the fetus itself and the shape of your uterus. Because you can't can’t control either of these factors, breech presentation typically isn’t considered preventable. And while the cause often isn't known, there are certain risk factors that may increase your risk of a breech baby, including the following:

- The fetus may have abnormalities involving the muscular or central nervous system

- The uterus may have abnormal growths or fibroids

- There might be insufficient amniotic fluid in the uterus (too much or too little)

- This isn’t your first pregnancy

- You have a history of premature delivery

- You have placenta previa (the placenta partially or fully covers the cervix)

- You’re pregnant with multiples

- You’ve had a previous breech baby

In some cases, your health care provider may attempt to help turn a baby in breech presentation through a procedure known as external cephalic version (ECV). This is when a health care professional applies gentle pressure on your lower abdomen to try and coax your baby into a head-down position. During the entire procedure, the fetus's health will be monitored, and an ECV is often performed near a delivery room, in the event of any potential issues or complications.

However, it's important to note that ECVs aren't for everyone. If you're carrying multiples, there's health concerns about you or the baby, or you've experienced certain complications with your placenta or based on placental location, a health care provider will not attempt an ECV.

The majority of breech babies are born through C-sections . These are usually scheduled between 38 and 39 weeks of pregnancy, before labor can begin naturally. However, with a health care provider experienced in delivering breech babies vaginally, a natural delivery might be a safe option for some people. In fact, a 2017 study showed similar complication and success rates with vaginal and C-section deliveries of breech babies.

That said, there are certain known risks and complications that can arise with an attempt to deliver a breech baby vaginally, many of which relate to problems with the umbilical cord. If you and your medical team decide on a vaginal delivery, your baby will be monitored closely for any potential signs of distress.

Ultimately, it's important to know that most breech babies are born healthy. Your provider will consider your specific medical condition and the position of your baby to determine which type of delivery will be the safest option for a healthy and successful birth.

ACOG. If Your Baby Is Breech .

American Pregnancy Association. Breech Presentation .

Gray CJ, Shanahan MM. Breech Presentation . [Updated 2022 Nov 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

Mount Sinai. Breech Babies .

Takeda J, Ishikawa G, Takeda S. Clinical Tips of Cesarean Section in Case of Breech, Transverse Presentation, and Incarcerated Uterus . Surg J (N Y). 2020 Mar 18;6(Suppl 2):S81-S91. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1702985. PMID: 32760790; PMCID: PMC7396468.

Shanahan MM, Gray CJ. External Cephalic Version . [Updated 2022 Nov 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

Fonseca A, Silva R, Rato I, Neves AR, Peixoto C, Ferraz Z, Ramalho I, Carocha A, Félix N, Valdoleiros S, Galvão A, Gonçalves D, Curado J, Palma MJ, Antunes IL, Clode N, Graça LM. Breech Presentation: Vaginal Versus Cesarean Delivery, Which Intervention Leads to the Best Outcomes? Acta Med Port. 2017 Jun 30;30(6):479-484. doi: 10.20344/amp.7920. Epub 2017 Jun 30. PMID: 28898615.

Related Articles

When viewing this topic in a different language, you may notice some differences in the way the content is structured, but it still reflects the latest evidence-based guidance.

Breech presentation

- Overview

- Theory

- Diagnosis

- Management

- Follow up

- Resources

Breech presentation refers to the baby presenting for delivery with the buttocks or feet first rather than head.

Associated with increased morbidity and mortality for the mother in terms of emergency cesarean section and placenta previa; and for the baby in terms of preterm birth, small fetal size, congenital anomalies, and perinatal mortality.

Incidence decreases as pregnancy progresses and by term occurs in 3% to 4% of singleton term pregnancies.

Treatment options include external cephalic version to increase the likelihood of vaginal birth or a planned cesarean section, the optimal gestation being 37 and 39 weeks, respectively.

Planned cesarean section is considered the safest form of delivery for infants with a persisting breech presentation at term.

Breech presentation in pregnancy occurs when a baby presents with the buttocks or feet rather than the head first (cephalic presentation) and is associated with increased morbidity and mortality for both the mother and the baby. [1] Cunningham F, Gant N, Leveno K, et al. Williams obstetrics. 21st ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1997. [2] Kish K, Collea JV. Malpresentation and cord prolapse. In: DeCherney AH, Nathan L, eds. Current obstetric and gynecologic diagnosis and treatment. New York: McGraw-Hill Professional; 2002. There is good current evidence regarding effective management of breech presentation in late pregnancy using external cephalic version and/or planned cesarean section.

History and exam

Key diagnostic factors.

- buttocks or feet as the presenting part

- fetal head under costal margin

- fetal heartbeat above the maternal umbilicus

Other diagnostic factors

- subcostal tenderness

- pelvic or bladder pain

Risk factors

- premature fetus

- small for gestational age fetus

- nulliparity

- fetal congenital anomalies

- previous breech delivery

- uterine abnormalities

- abnormal amniotic fluid volume

- placental abnormalities

- female fetus

Diagnostic tests

1st tests to order.

- transabdominal/transvaginal ultrasound

Treatment algorithm

<37 weeks' gestation and in labor, ≥37 weeks' gestation not in labor, ≥37 weeks' gestation in labor: no imminent delivery, ≥37 weeks' gestation in labor: imminent delivery, contributors, natasha nassar, phd.

Associate Professor

Menzies Centre for Health Policy

Sydney School of Public Health

University of Sydney

Disclosures

NN has received salary support from Australian National Health and a Medical Research Council Career Development Fellowship; she is an author of a number of references cited in this topic.

Christine L. Roberts, MBBS, FAFPHM, DrPH

Research Director

Clinical and Population Health Division

Perinatal Medicine Group

Kolling Institute of Medical Research

CLR declares that she has no competing interests.

Jonathan Morris, MBChB, FRANZCOG, PhD

Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology and Head of Department

JM declares that he has no competing interests.

Peer reviewers

John w. bachman, md.

Consultant in Family Medicine

Department of Family Medicine

Mayo Clinic

JWB declares that he has no competing interests.

Rhona Hughes, MBChB

Lead Obstetrician

Lothian Simpson Centre for Reproductive Health

The Royal Infirmary

RH declares that she has no competing interests.

Brian Peat, MD

Director of Obstetrics

Women's and Children's Hospital

North Adelaide

South Australia

BP declares that he has no competing interests.

Lelia Duley, MBChB

Professor of Obstetric Epidemiology

University of Leeds

Bradford Institute of Health Research

Temple Bank House

Bradford Royal Infirmary

LD declares that she has no competing interests.

Justus Hofmeyr, MD

Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology

East London Private Hospital

East London

South Africa

JH is an author of a number of references cited in this topic.

Differentials

- Transverse lie

- Caesarean birth

- Mode of term singleton breech delivery

Use of this content is subject to our disclaimer

Log in or subscribe to access all of BMJ Best Practice

Log in to access all of bmj best practice, help us improve bmj best practice.

Please complete all fields.

I have some feedback on:

We will respond to all feedback.

For any urgent enquiries please contact our customer services team who are ready to help with any problems.

Phone: +44 (0) 207 111 1105

Email: [email protected]

Your feedback has been submitted successfully.

- Pregnancy Classes

Breech Births

In the last weeks of pregnancy, a baby usually moves so his or her head is positioned to come out of the vagina first during birth. This is called a vertex presentation. A breech presentation occurs when the baby’s buttocks, feet, or both are positioned to come out first during birth. This happens in 3–4% of full-term births.

What are the different types of breech birth presentations?

- Complete breech: Here, the buttocks are pointing downward with the legs folded at the knees and feet near the buttocks.

- Frank breech: In this position, the baby’s buttocks are aimed at the birth canal with its legs sticking straight up in front of his or her body and the feet near the head.

- Footling breech: In this position, one or both of the baby’s feet point downward and will deliver before the rest of the body.

What causes a breech presentation?

The causes of breech presentations are not fully understood. However, the data show that breech birth is more common when:

- You have been pregnant before

- In pregnancies of multiples

- When there is a history of premature delivery

- When the uterus has too much or too little amniotic fluid

- When there is an abnormally shaped uterus or a uterus with abnormal growths, such as fibroids

- The placenta covers all or part of the opening of the uterus placenta previa

How is a breech presentation diagnosed?

A few weeks prior to the due date, the health care provider will place her hands on the mother’s lower abdomen to locate the baby’s head, back, and buttocks. If it appears that the baby might be in a breech position, they can use ultrasound or pelvic exam to confirm the position. Special x-rays can also be used to determine the baby’s position and the size of the pelvis to determine if a vaginal delivery of a breech baby can be safely attempted.

Can a breech presentation mean something is wrong?

Even though most breech babies are born healthy, there is a slightly elevated risk for certain problems. Birth defects are slightly more common in breech babies and the defect might be the reason that the baby failed to move into the right position prior to delivery.

Can a breech presentation be changed?

It is preferable to try to turn a breech baby between the 32nd and 37th weeks of pregnancy . The methods of turning a baby will vary and the success rate for each method can also vary. It is best to discuss the options with the health care provider to see which method she recommends.

Medical Techniques

External Cephalic Version (EVC) is a non-surgical technique to move the baby in the uterus. In this procedure, a medication is given to help relax the uterus. There might also be the use of an ultrasound to determine the position of the baby, the location of the placenta and the amount of amniotic fluid in the uterus.

Gentle pushing on the lower abdomen can turn the baby into the head-down position. Throughout the external version the baby’s heartbeat will be closely monitored so that if a problem develops, the health care provider will immediately stop the procedure. ECV usually is done near a delivery room so if a problem occurs, a cesarean delivery can be performed quickly. The external version has a high success rate and can be considered if you have had a previous cesarean delivery.

ECV will not be tried if:

- You are carrying more than one fetus

- There are concerns about the health of the fetus

- You have certain abnormalities of the reproductive system

- The placenta is in the wrong place

- The placenta has come away from the wall of the uterus ( placental abruption )

Complications of EVC include:

- Prelabor rupture of membranes

- Changes in the fetus’s heart rate

- Placental abruption

- Preterm labor

Vaginal delivery versus cesarean for breech birth?

Most health care providers do not believe in attempting a vaginal delivery for a breech position. However, some will delay making a final decision until the woman is in labor. The following conditions are considered necessary in order to attempt a vaginal birth:

- The baby is full-term and in the frank breech presentation

- The baby does not show signs of distress while its heart rate is closely monitored.

- The process of labor is smooth and steady with the cervix widening as the baby descends.

- The health care provider estimates that the baby is not too big or the mother’s pelvis too narrow for the baby to pass safely through the birth canal.

- Anesthesia is available and a cesarean delivery possible on short notice

What are the risks and complications of a vaginal delivery?

In a breech birth, the baby’s head is the last part of its body to emerge making it more difficult to ease it through the birth canal. Sometimes forceps are used to guide the baby’s head out of the birth canal. Another potential problem is cord prolapse . In this situation the umbilical cord is squeezed as the baby moves toward the birth canal, thus slowing the baby’s supply of oxygen and blood. In a vaginal breech delivery, electronic fetal monitoring will be used to monitor the baby’s heartbeat throughout the course of labor. Cesarean delivery may be an option if signs develop that the baby may be in distress.

When is a cesarean delivery used with a breech presentation?

Most health care providers recommend a cesarean delivery for all babies in a breech position, especially babies that are premature. Since premature babies are small and more fragile, and because the head of a premature baby is relatively larger in proportion to its body, the baby is unlikely to stretch the cervix as much as a full-term baby. This means that there might be less room for the head to emerge.

Want to Know More?

- Creating Your Birth Plan

- Labor & Birth Terms to Know

- Cesarean Birth After Care

Compiled using information from the following sources:

- ACOG: If Your Baby is Breech

- William’s Obstetrics Twenty-Second Ed. Cunningham, F. Gary, et al, Ch. 24.

- Danforth’s Obstetrics and Gynecology Ninth Ed. Scott, James R., et al, Ch. 21.

BLOG CATEGORIES

- Pregnancy Symptoms 5

- Can I get pregnant if… ? 3

- Paternity Tests 2

- The Bumpy Truth Blog 7

- Multiple Births 10

- Pregnancy Complications 68

- Pregnancy Concerns 62

- Cord Blood 4

- Pregnancy Supplements & Medications 14

- Pregnancy Products & Tests 8

- Changes In Your Body 5

- Health & Nutrition 2

- Labor and Birth 65

- Planning and Preparing 24

- Breastfeeding 29

- Week by Week Newsletter 40

- Is it Safe While Pregnant 55

- The First Year 41

- Genetic Disorders & Birth Defects 17

- Pregnancy Health and Wellness 149

- Your Developing Baby 16

- Options for Unplanned Pregnancy 18

- Child Adoption 19

- Fertility 54

- Pregnancy Loss 11

- Uncategorized 4

- Women's Health 34

- Prenatal Testing 16

- Abstinence 3

- Birth Control Pills, Patches & Devices 21

- Thank You for Your Donation

- Unplanned Pregnancy

- Getting Pregnant

- Healthy Pregnancy

- Privacy Policy

- Pregnancy Questions Center

Share this post:

Similar post.

Episiotomy: Advantages & Complications

Retained Placenta

What is Dilation in Pregnancy?

Track your baby’s development, subscribe to our week-by-week pregnancy newsletter.

- The Bumpy Truth Blog

- Fertility Products Resource Guide

Pregnancy Tools

- Ovulation Calendar

- Baby Names Directory

- Pregnancy Due Date Calculator

- Pregnancy Quiz

Pregnancy Journeys

- Partner With Us

- Corporate Sponsors

Breech Presentation

- 📖 Geeky Medics OSCE Book

- ⚡ Geeky Medics Bundles

- ✨ 1300+ OSCE Stations

- ✅ OSCE Checklist PDF Booklet

- 🧠 UKMLA AKT Question Bank

- 💊 PSA Question Bank

- 💉 Clinical Skills App

- 🗂️ Flashcard Collections | OSCE , Medicine , Surgery , Anatomy

- 💬 SCA Cases for MRCGP

To be the first to know about our latest videos subscribe to our YouTube channel 🙌

Table of Contents

Suggest an improvement

- Hidden Post Title

- Hidden Post URL

- Hidden Post ID

- Type of issue * N/A Fix spelling/grammar issue Add or fix a link Add or fix an image Add more detail Improve the quality of the writing Fix a factual error

- Please provide as much detail as possible * You don't need to tell us which article this feedback relates to, as we automatically capture that information for you.

- Your Email (optional) This allows us to get in touch for more details if required.

- Which organ is responsible for pumping blood around the body? * Enter a five letter word in lowercase

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Introduction

Breech presentation is a type of malpresentation and occurs when the fetal head lies over the uterine fundus and fetal buttocks or feet present over the maternal pelvis (instead of cephalic/head presentation).

The incidence in the United Kingdom of breech presentation is 3-4% of all fetuses. 1

Breech presentation is most commonly idiopathic .

Types of breech presentation

The three types of breech presentation are:

- Complete (flexed) breech : one or both knees are flexed (Figure 1)

- Footling (incomplete) breech : one or both feet present below the fetal buttocks, with hips and knees extended (Figure 2)

- Frank (extended) breech : both hips flexed and both knees extended. Babies born in frank breech are more likely to have developmental dysplasia of the hip (Figure 3)

Risk factors

Risk factors for breech presentation can be divided into maternal , fetal and placental risk factors:

- Maternal : multiparity, fibroids, previous breech presentation, Mullerian duct abnormalities

- Fetal : preterm, macrosomia, fetal abnormalities (anencephaly, hydrocephalus, cystic hygroma), multiple pregnancy

- Placental : placenta praevia , polyhydramnios, oligohydramnios , amniotic bands

Clinical features

Before 36 weeks , breech presentation is not significant, as the fetus is likely to revert to a cephalic presentation. The mother will often be asymptomatic with the diagnosis being incidental.

The incidence of breech presentation is approximately 20% at 28 weeks gestation, 16% at 32 weeks gestation and 3-4% at term . Therefore, breech presentation is more common in preterm labour . Most fetuses with breech presentation in the early third trimester will turn spontaneously and be cephalic at term.

However, spontaneous version rates for nulliparous women with breech presentation at 36 weeks of gestation are less than 10% .

Clinical examination

Typical clinical findings of a breech presentation include:

- Longitudinal lie

- Head palpated at the fundus

- Irregular mass over pelvis (feet, legs and buttocks)

- Fetal heart auscultated higher on the maternal abdomen

- Palpation of feet or sacrum at the cervical os during vaginal examination

For more information, see the Geeky Medics guide to obstetric abdominal examination .

Positions in breech presentation

There are multiple fetal positions in breech presentation which are described according to the relation of the fetal sacrum to the maternal pelvis .

These are: direct sacroanterior, left sacroanterior, right sacroanterior, direct sacroposterior, right sacroposterior, left sacroposterior, left sacrotransverse and right sacrotranverse. 5

Investigations

An ultrasound scan is diagnostic for breech presentation. Growth, amniotic fluid volume and anatomy should be assessed to check for abnormalities.

There are three management options for breech presentation at term, with consideration of maternal choice: external cephalic version , vaginal delivery and Caesarean section .

External cephalic version

External cephalic version (ECV) involves manual rotation of the fetus into a cephalic presentation by applying pressure to the maternal abdomen under ultrasound guidance. Entonox and subcutaneous terbutaline are used to relax the uterus.

ECV has a 40% success rate in primiparous women and 60% in multiparous women . It should be offered to nulliparous women at 36 weeks and multiparous women at 37 weeks gestation.

If ECV is unsuccessful, then delivery options include elective caesarean section or vaginal delivery.

Contraindications for undertaking external cephalic version include:

- Antepartum haemorrhage

- Ruptured membranes

- Previous caesarean section

- Major uterine abnormality

- Multiple pregnancy

- Abnormal cardiotocography (CTG)

Vaginal delivery

Vaginal delivery is an option but carries risks including head entrapment, birth asphyxia, intracranial haemorrhage, perinatal mortality, cord prolapse and fetal and/or maternal trauma.

The preference is to deliver the baby without traction and with an anterior sacrum during delivery to decrease the risk of fetal head entrapment .

The mother may be offered an epidural , as vaginal breech delivery can be very painful. 6

Contraindications for vaginal delivery in a breech presentation include:

- Footling breech: the baby’s head and trunk are more likely to be trapped if the feet pass through the dilated cervix too soon

- Macrosomia: usually defined as larger than 3800g

- Growth restricted baby: usually defined as smaller than 2000g

- Other complications of vaginal birth: for example, placenta praevia and fetal compromise

- Lack of clinical staff trained in vaginal breech delivery

Caesarean section

A caesarian section booked as an elective procedure at term is the most common management for breech presentation.

Caesarean section is preferred for preterm babies (due to an increased head to abdominal circumference ratio in preterm babies) and is used if the external cephalic version is unsuccessful or as a maternal preference. This option has fewer risks than a vaginal delivery.

Complications

Fetal complications of breech presentation include:

- Developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH)

- Cord prolapse

- Fetal head entrapment

- Birth asphyxia

- Intracranial haemorrhage

- Perinatal mortality

Complications of external cephalic version include:

- Transient fetal heart abnormalities (common)

- Fetomaternal haemorrhage

- Placental abruption (rare)

- There are three types of breech presentation: complete, incomplete and frank breech

- The most common clinical findings include: longitudinal lie, smooth fetal head-shape at the fundus, irregular masses over the pelvis and abnormal placement being required for fetal hear auscultation

- The diagnostic investigation is an ultrasound scan

- Breech presentation can be managed in three ways: external cephalic version , vaginal delivery or elective caesarean section

- Complications are more common in vaginal delivery , such as cord prolapse, fetal head entrapment, intracranial haemorrhage and birth asphyxia

Miss Saba Al Juboori

Consultant in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

Miss Neeraja Kuruba

Dr chris jefferies.

- Oxford Handbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Breech Presentation: Overview. Published in 2011.

- Jemimah Thomas. Image: Complete breech.

- Bonnie Urquhart Gruenberg. Footling breech. Licence: [ CC BY-SA ]

- Bonnie Urquhart Gruenberg. Frank breech . Licence: [ CC BY-SA ]

- A Comprehensive Textbook of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Chapter 50: Malpresentation and Malposition: Breech Presentation. Published in 2011.

- Diana Hamilton Fairley. Lecture Notes: Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Malpresentation, Breech Presentation. Published in 2009.

Other pages

- Product Bundles 🎉

- Join the Team 🙌

- Institutional Licence 📚

- OSCE Station Creator Tool 🩺

- Create and Share Flashcards 🗂️

- OSCE Group Chat 💬

- Newsletter 📰

- Advertise With Us

Join the community

Breech Presentation

- Author: Richard Fischer, MD; Chief Editor: Ronald M Ramus, MD more...

- Sections Breech Presentation

- Vaginal Breech Delivery

- Cesarean Delivery

- Comparative Studies

- External Cephalic Version

- Conclusions

- Media Gallery

Breech presentation is defined as a fetus in a longitudinal lie with the buttocks or feet closest to the cervix. This occurs in 3-4% of all deliveries. The percentage of breech deliveries decreases with advancing gestational age from 22-25% of births prior to 28 weeks' gestation to 7-15% of births at 32 weeks' gestation to 3-4% of births at term. [ 1 ]

Predisposing factors for breech presentation include prematurity , uterine malformations or fibroids, polyhydramnios , placenta previa , fetal abnormalities (eg, CNS malformations, neck masses, aneuploidy), and multiple gestations . Fetal abnormalities are observed in 17% of preterm breech deliveries and in 9% of term breech deliveries.

Perinatal mortality is increased 2- to 4-fold with breech presentation, regardless of the mode of delivery. Deaths are most often associated with malformations, prematurity, and intrauterine fetal demise .

Types of breeches

The types of breeches are as follows:

Frank breech (50-70%) - Hips flexed, knees extended (pike position)

Complete breech (5-10%) - Hips flexed, knees flexed (cannonball position)

Footling or incomplete (10-30%) - One or both hips extended, foot presenting

Historical considerations

Vaginal breech deliveries were previously the norm until 1959 when it was proposed that all breech presentations should be delivered abdominally to reduce perinatal morbidity and mortality. [ 2 ]

Vaginal breech delivery

Three types of vaginal breech deliveries are described, as follows:

Spontaneous breech delivery: No traction or manipulation of the infant is used. This occurs predominantly in very preterm, often previable, deliveries.

Assisted breech delivery: This is the most common type of vaginal breech delivery. The infant is allowed to spontaneously deliver up to the umbilicus, and then maneuvers are initiated to assist in the delivery of the remainder of the body, arms, and head.

Total breech extraction: The fetal feet are grasped, and the entire fetus is extracted. Total breech extraction should be used only for a noncephalic second twin; it should not be used for a singleton fetus because the cervix may not be adequately dilated to allow passage of the fetal head. Total breech extraction for the singleton breech is associated with a birth injury rate of 25% and a mortality rate of approximately 10%. Total breech extractions are sometimes performed by less experienced accoucheurs when a foot unexpectedly prolapses through the vagina. As long as the fetal heart rate is stable in this situation, it is permissible to manage expectantly to allow the cervix to completely dilate around the breech (see the image below).

Technique and tips for assisted vaginal breech delivery

The fetal membranes should be left intact as long as possible to act as a dilating wedge and to prevent overt cord prolapse .

Oxytocin induction and augmentation are controversial. In many previous studies, oxytocin was used for induction and augmentation, especially for hypotonic uterine dysfunction. However, others are concerned that nonphysiologic forceful contractions could result in an incompletely dilated cervix and an entrapped head.

An anesthesiologist and a pediatrician should be immediately available for all vaginal breech deliveries. A pediatrician is needed because of the higher prevalence of neonatal depression and the increased risk for unrecognized fetal anomalies. An anesthesiologist may be needed if intrapartum complications develop and the patient requires general anesthesia .

Some clinicians perform an episiotomy when the breech delivery is imminent, even in multiparas, as it may help prevent soft tissue dystocia for the aftercoming head (see the images below).

The Pinard maneuver may be needed with a frank breech to facilitate delivery of the legs but only after the fetal umbilicus has been reached. Pressure is exerted in the popliteal space of the knee. Flexion of the knee follows, and the lower leg is swept medially and out of the vagina.

No traction should be exerted on the infant until the fetal umbilicus is past the perineum, after which time maternal expulsive efforts should be used along with gentle downward and outward traction of the infant until the scapula and axilla are visible (see the image below).

Use a dry towel to wrap around the hips (not the abdomen) to help with gentle traction of the infant (see the image below).

An assistant should exert transfundal pressure from above to keep the fetal head flexed.

Once the scapula is visible, rotate the infant 90° and gently sweep the anterior arm out of the vagina by pressing on the inner aspect of the arm or elbow (see the image below).

Rotate the infant 180° in the reverse direction, and sweep the other arm out of the vagina. Once the arms are delivered, rotate the infant back 90° so that the back is anterior (see the image below).

The fetal head should be maintained in a flexed position during delivery to allow passage of the smallest diameter of the head. The flexed position can be accomplished by using the Mauriceau Smellie Veit maneuver, in which the operator's index and middle fingers lift up on the fetal maxillary prominences, while the assistant applies suprapubic pressure (see the image below).

Alternatively, Piper forceps can be used to maintain the head in a flexed position (see the image below).

In many early studies, routine use of Piper forceps was recommended to protect the head and to minimize traction on the fetal neck. Piper forceps are specialized forceps that are placed from below the infant and, unlike conventional forceps, are not tailored to the position of the fetal head (ie, it is a pelvic, not cephalic, application). The forceps are applied while the assistant supports the fetal body in a horizontal plane.

During delivery of the head, avoid extreme elevation of the body, which may result in hyperextension of the cervical spine and potential neurologic injury (see the images below).

Lower Apgar scores, especially at 1 minute, are more common with vaginal breech deliveries. Many advocate obtaining an umbilical cord artery and venous pH for all vaginal breech deliveries to document that neonatal depression is not due to perinatal acidosis.

Fetal head entrapment may result from an incompletely dilated cervix and a head that lacks time to mold to the maternal pelvis. This occurs in 0-8.5% of vaginal breech deliveries. [ 3 ] This percentage is higher with preterm fetuses (< 32 wk), when the head is larger than the body. Dührssen incisions (ie, 1-3 cervical incisions made to facilitate delivery of the head) may be necessary to relieve cervical entrapment. However, extension of the incision can occur into the lower segment of the uterus, and the operator must be equipped to deal with this complication. The Zavanelli maneuver has been described, which involves replacement of the fetus into the abdominal cavity followed by cesarean delivery. While success has been reported with this maneuver, fetal injury and even fetal death have occurred.

Nuchal arms, in which one or both arms are wrapped around the back of the neck, are present in 0-5% of vaginal breech deliveries and in 9% of breech extractions. [ 3 ] Nuchal arms may result in neonatal trauma (including brachial plexus injuries) in 25% of cases. Risks may be reduced by avoiding rapid extraction of the infant during delivery of the body. To relieve nuchal arms when it is encountered, rotate the infant so that the fetal face turns toward the maternal symphysis pubis (in the direction of the impacted arm); this reduces the tension holding the arm around the back of the fetal head, allowing for delivery of the arm.

Cervical spine injury is predominantly observed when the fetus has a hyperextended head prior to delivery. Ballas and Toaff (1976) reported 20 cases of hyperextended necks, defined as an angle of extension greater than 90° ("star-gazing"), discovered on antepartum radiographs. [ 4 ] Of the 11 fetuses delivered vaginally, 8 (73%) sustained complete cervical spinal cord lesions, defined as either transection or nonfunction.

Cord prolapse may occur in 7.4% of all breech labors. This incidence varies with the type of breech: 0-2% with frank breech, 5-10% with complete breech, and 10-25% with footling breech. [ 3 ] Cord prolapse occurs twice as often in multiparas (6%) than in primigravidas (3%). Cord prolapse may not always result in severe fetal heart rate decelerations because of the lack of presenting parts to compress the umbilical cord (ie, that which predisposes also protects).

Prior to the 2001 recommendations by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), approximately 50% of breech presentations were considered candidates for vaginal delivery. Of these candidates, 60-82% were successfully delivered vaginally.

Candidates can be classified based on gestational age. For pregnancies prior to 26 weeks' gestation, prematurity, not mode of delivery, is the greatest risk factor. Unfortunately, no randomized clinical trials to help guide clinical management have been reported. Vaginal delivery can be considered, but a detailed discussion of the risks from prematurity and the lack of data regarding the ideal mode of delivery should take place with the parent(s). For example, intraventricular hemorrhage, which can occur in an infant of extremely low birth weight, should not be misinterpreted as proof of a traumatic vaginal breech delivery.

For pregnancies between 26 and 32 weeks, retrospective studies suggest an improved outcome with cesarean delivery, although these reports are subject to selection bias. In contrast, between 32 and 36 weeks' gestation, vaginal breech delivery may be considered after a discussion of risks and benefits with the parent(s).

After 37 weeks' gestation, parents should be informed of the results of a multicenter randomized clinical trial that demonstrated significantly increased perinatal mortality and short-term neonatal morbidity associated with vaginal breech delivery (see Comparative Studies). For those attempting vaginal delivery, if estimated fetal weight (EFW) is more than 4000 g, some recommend cesarean delivery because of concern for entrapment of the unmolded head in the maternal pelvis, although data to support this practice are limited.

A frank breech presentation is preferred when vaginal delivery is attempted. Complete breeches and footling breeches are still candidates, as long as the presenting part is well applied to the cervix and both obstetrical and anesthesia services are readily available in the event of a cord prolapse.

The fetus should show no neck hyperextension on antepartum ultrasound imaging (see the image below). Flexed or military position is acceptable.

Regarding prior cesarean delivery, a retrospective study by Ophir et al of 71 women with one prior low transverse cesarean delivery who subsequently delivered a breech fetus found that 24 women had an elective repeat cesarean and 47 women had a trial of labor. [ 5 ] In the 47 women with a trial of labor, 37 (78.7%) resulted in a vaginal delivery. Two infants in the trial of labor group had nuchal arms (1 with a transient brachial plexus injury) and 1 woman required a hysterectomy for hemorrhage due to a uterine dehiscence discovered after vaginal delivery. Vaginal breech delivery after one prior cesarean delivery is not contraindicated, though larger studies are needed.

Primigravida versus multiparous

It had been commonly believed that primigravidas with a breech presentation should have a cesarean delivery, although no data (prospective or retrospective) support this view. The only documented risk related to parity is cord prolapse, which is 2-fold higher in parous women than in primigravid women.

Radiographic and CT pelvimetry

Historically, radiograph pelvimetry was believed to be useful to quantitatively assess the inlet and mid pelvis. Recommended pelvimetry criteria included a transverse inlet diameter larger than 11.5 cm, anteroposterior inlet diameter larger than 10.5 cm, transverse midpelvic diameter (between the ischial spines) larger than 10 cm, and anteroposterior midpelvic diameter larger than 11.5 cm. However, radiographic pelvimetry is rarely, if ever, used in the United States.

CT pelvimetry , which is associated with less fetal radiation exposure than conventional radiographic pelvimetry, was more recently advocated by some investigators. It, too, is rarely used today.

Ultimately, if the obstetrical operator is not experienced or comfortable with vaginal breech deliveries, cesarean delivery may be the best choice. Unfortunately, with the dwindling number of experienced obstetricians who still perform vaginal breech deliveries and who can teach future generations of obstetricians, this technique may soon be lost due to attrition.

In 1970, approximately 14% of breeches were delivered by cesarean delivery. By 1986, that rate had increased to 86%. In 2003, based on data from the National Center for Health Statistics, the rate of cesarean delivery for all breech presentations was 87.2%. Most of the remaining breeches delivered vaginally were likely second twins, fetal demises, and precipitous deliveries. However, the rise in cesarean deliveries for breeches has not necessarily equated with an improvement in perinatal outcome. Green et al compared the outcome for term breeches prior to 1975 (595 infants, 22% cesarean delivery rate for breeches) with those from 1978-1979 (164 infants, 94% cesarean delivery rate for breeches). [ 6 ] Despite the increase in rates of cesarean delivery, the differences in rates of asphyxia, birth injury, and perinatal deaths were not significant.

Maneuvers for cesarean delivery are similar to those for vaginal breech delivery, including the Pinard maneuver, wrapping the hips with a towel for traction, head flexion during traction, rotation and sweeping out of the fetal arms, and the Mauriceau Smellie Veit maneuver.

An entrapped head can still occur during cesarean delivery as the uterus contracts after delivery of the body, even with a lower uterine segment that misleadingly appears adequate prior to uterine incision. Entrapped heads occur more commonly with preterm breeches, especially with a low transverse uterine incision. As a result, some practitioners opt to perform low vertical uterine incisions for preterm breeches prior to 32 weeks' gestation to avoid head entrapment and the kind of difficult delivery that cesarean delivery was meant to avoid. Low vertical incisions usually require extension into the corpus, resulting in cesarean delivery for all future deliveries.

If a low transverse incision is performed, the physician should move quickly once the breech is extracted in order to deliver the head before the uterus begins to contract. If any difficulty is encountered with delivery of the fetal head, the transverse incision can be extended vertically upward (T incision). Alternatively, the transverse incision can be extended laterally and upward, taking great care to avoid trauma to the uterine arteries. A third option is the use of a short-acting uterine relaxant (eg, nitroglycerin) in an attempt to facilitate delivery.

Only 3 randomized studies have evaluated the mode of delivery of the term breech. All other studies were nonrandomized or retrospective, which may be subject to selection bias.

In 1980, Collea et al randomized 208 women in labor with term frank breech presentations to either elective cesarean delivery or attempted vaginal delivery after radiographic pelvimetry. [ 7 ] Oxytocin was allowed for dysfunctional labor. Of the 60 women with adequate pelves, 49 delivered vaginally. Two neonates had transient brachial plexus injuries. Women randomized to elective cesarean delivery had higher postpartum morbidity rates (49.3% vs 6.7%).

In 1983, Gimovsky et al randomized 105 women in labor with term nonfrank breech presentations to a trial of labor versus elective cesarean delivery. [ 8 ] In this group of women, 47 had complete breech presentations, 16 had incomplete breech presentations (hips flexed, 1 knee extended/1 knee flexed), 32 had double-footling presentations, and 10 had single-footling presentations. Oxytocin was allowed for dysfunctional labor. Of the labor group, 44% had successful vaginal delivery. Most cesarean deliveries were performed for inadequate pelvic dimensions on radiographic pelvimetry. The rate of neonatal morbidity did not differ between neonates delivered vaginally and those delivered by cesarean delivery, although a higher maternal morbidity rate was noted in the cesarean delivery group.

In 2000, Hannah and colleagues completed a large, multicenter, randomized clinical trial involving 2088 term singleton fetuses in frank or complete breech presentations at 121 institutions in 26 countries. [ 9 ] In this study, popularly known as the Term Breech Trial, subjects were randomized into a planned cesarean delivery group or a planned vaginal birth group. Exclusion criteria were estimated fetal weight (EFW) more than 4000 g, hyperextension of the fetal head, lethal fetal anomaly or anomaly that might result in difficulty with delivery, or contraindication to labor or vaginal delivery (eg, placenta previa ).

Subjects randomized to cesarean delivery were scheduled to deliver after 38 weeks' gestation unless conversion to cephalic presentation had occurred. Subjects randomized to vaginal delivery were treated expectantly until labor ensued. Electronic fetal monitoring was either continuous or intermittent. Inductions were allowed for standard obstetrical indications, such as postterm gestations. Augmentation with oxytocin was allowed in the absence of apparent fetopelvic disproportion, and epidural analgesia was permitted.

Adequate labor was defined as a cervical dilation rate of 0.5 cm/h in the active phase of labor and the descent of the breech fetus to the pelvic floor within 2 hours of achieving full dilation. Vaginal delivery was spontaneous or assisted and was attended by an experienced obstetrician. Cesarean deliveries were performed for inadequate progress of labor, nonreassuring fetal heart rate, or conversion to footling breech. Results were analyzed by intent-to-treat (ie, subjects were analyzed by randomization group, not by ultimate mode of delivery).

Of 1041 subjects in the planned cesarean delivery group, 941 (90.4%) had cesarean deliveries. Of 1042 subjects in the planned vaginal delivery group, 591 (56.7%) had vaginal deliveries. Indications for cesarean delivery included: fetopelvic disproportion or failure to progress in labor (226), nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracing (129), footling breech (69), request for cesarean delivery (61), obstetrical or medical indications (45), or cord prolapse (12).

The composite measurement of either perinatal mortality or serious neonatal morbidity by 6 weeks of life was significantly lower in the planned cesarean group than in the planned vaginal group (5% vs 1.6%, P < .0001). Six of 16 neonatal deaths were associated with difficult vaginal deliveries, and 4 deaths were associated with fetal heart rate abnormalities. The reduction in risk in the cesarean group was even greater in participating countries with overall low perinatal mortality rates as reported by the World Health Organization. The difference in perinatal outcome held after controlling for the experience level of the obstetrician. No significant difference was noted in maternal mortality or serious maternal morbidity between the 2 groups within the first 6 weeks of delivery (3.9% vs 3.2%, P = .35).

A separate analysis showed no difference in breastfeeding, sexual relations, or depression at 3 months postpartum, though the reported rate of urinary incontinence was higher in the planned vaginal group (7.3% vs 4.5%).

Based on the multicenter trial, the ACOG published a Committee Opinion in 2001 that stated "planned vaginal delivery of a singleton term breech may no longer be appropriate." This did not apply to those gravidas presenting in advanced labor with a term breech and imminent delivery or to a nonvertex second twin.

A follow-up study by Whyte et al was conducted in 2004 on 923 children who were part of the initial multicenter study. [ 10 ] The authors found no differences between the planned cesarean delivery and planned vaginal breech delivery groups with regards to infant death rates or neurodevelopmental delay by age 2 years. Similarly, among 917 participating mothers from the original trial, no substantive differences were apparent in maternal outcome between the 2 groups. [ 11 ] No longer-term maternal effects, such as the impact of a uterine scar on future pregnancies, have yet been reported.

A meta-analysis of the 3 above mentioned randomized trials was published in 2015. The findings included a reduction in perinatal/neonatal death, reduced composite short-term outcome of perinatal/neonatal death or serious neonatal morbidity with planned cesarean delivery versus planned vaginal delivery. [ 12 ] However, at 2 years of age, there was no significant difference in death or neurodevelopmental delay between the two groups. Maternal outcomes assessed at 2 years after delivery were not significantly different.

With regard to preterm breech deliveries, only one prospective randomized study has been performed, which included only 38 subjects (28-36 wk) with preterm labor and breech presentation. [ 13 ] Of these subjects, 20 were randomized to attempted vaginal delivery and 18 were randomized to immediate cesarean delivery. Of the attempted vaginal delivery group, 25% underwent cesarean delivery for nonreassuring fetal heart rate tracings. Five neonatal deaths occurred in the vaginal delivery group, and 1 neonatal death occurred in the cesarean delivery group. Two neonates died from fetal anomalies, 3 from respiratory distress, and 1 from sepsis.

Nonanomalous infants who died were not acidotic at delivery and did not have birth trauma. Differences in Apgar scores were not significant, although the vaginal delivery group had lower scores. The small number of enrolled subjects precluded any definitive conclusions regarding the safety of vaginal breech delivery for a preterm breech.

Retrospective analyses showed a higher mortality rate in vaginal breech neonates weighing 750-1500 g (26-32 wk), but less certain benefit was shown with cesarean delivery if the fetal weight was more than 1500 g (approximately 32 wk). Therefore, this subgroup of very preterm infants (26-32 wk) may benefit from cesarean delivery, although this recommendation is based on potentially biased retrospective data.

A large cohort study was published in 2015 from the Netherlands Perinatal Registry, which included 8356 women with a preterm (26-36 6/7 weeks) breech from 2000 to 2011, over three quarters of whom intended to deliver vaginally. In this overall cohort, there was no significant difference in perinatal mortality between the planned vaginal delivery and planned cesarean delivery groups (adjusted odds ratio 0.97, 95% confidence interval 0.60 – 1.57). However, the subgroup delivering at 28 to 32 weeks had a lower perinatal mortality with planned cesarean section (aOR 0.27, 95% CI 0.10 – 0.77). After adding a composite of perinatal morbidity, planned cesarean delivery was associated with a better outcome than a planned vaginal delivery (aOR 0.77, 95% CI 0.63 – 0.93. [ 14 ]

A Danish study found that nulliparous women with a singleton breech presentation who had a planned vaginal delivery were at significantly higher risk for postoperative complications, such as infection, compared with women who had a planned cesarean delivery. This increased risk was due to the likelihood of conversion to an emergency cesarean section, which occurred in over 69% of the planned vaginal deliveries in the study. [ 15 ]

The Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network of the US National Institute of Child Health and Human Development considered a multicenter randomized clinical trial of attempted vaginal delivery versus elective cesarean delivery for 24- to 28-week breech fetuses. [ 16 ] However, it was not initiated because of anticipated difficulty with recruitment, inadequate numbers to show statistically significant differences, and medicolegal concerns. Therefore, this study is not likely to be performed.

External cephalic version (ECV) is the transabdominal manual rotation of the fetus into a cephalic presentation.

Initially popular in the 1960s and 1970s, ECV virtually disappeared after reports of fetal deaths following the procedure. Reintroduced to the United States in the 1980s, it became increasingly popular in the 1990s.

Improved outcome may be related to the use of nonstress tests both before and after ECV, improved selection of low-risk fetuses, and Rh immune globulin to prevent isoimmunization.

Prepare for the possibility of cesarean delivery. Obtain a type and screen as well as an anesthesia consult. The patient should have nothing by mouth for at least 8 hours prior to the procedure. Recent ultrasonography should have been performed for fetal position, to check growth and amniotic fluid volume, to rule out a placenta previa, and to rule out anomalies associated with breech. Another sonogram should be performed on the day of the procedure to confirm that the fetus is still breech.

A nonstress test (biophysical profile as backup) should be performed prior to ECV to confirm fetal well-being.

Perform ECV in or near a delivery suite in the unlikely event of fetal compromise during or following the procedure, which may require emergent delivery.

ECV can be performed with 1 or 2 operators. Some prefer to have an assistant to help turn the fetus, elevate the breech out of the pelvis, or to monitor the position of the baby with ultrasonography. Others prefer a single operator approach, as there may be better coordination between the forces that are raising the breech and moving the head.

ECV is accomplished by judicious manipulation of the fetal head toward the pelvis while the breech is brought up toward the fundus. Attempt a forward roll first and then a backward roll if the initial attempts are unsuccessful. No consensus has been reached regarding how many ECV attempts are appropriate at one time. Excessive force should not be used at any time, as this may increase the risk of fetal trauma.

Following an ECV attempt, whether successful or not, repeat the nonstress test (biophysical profile if needed) prior to discharge. Also, administer Rh immune globulin to women who are Rh negative. Some physicians traditionally induce labor following successful ECV. However, as virtually all of these recently converted fetuses are unengaged, many practitioners will discharge the patient and wait for spontaneous labor to ensue, thereby avoiding the risk of a failed induction of labor. Additionally, as most ECV’s are attempted prior to 39 weeks, as long as there are no obstetrical or medical indications for induction, discharging the patient to await spontaneous labor would seem most prudent.

In those with an unsuccessful ECV, the practitioner has the option of sending the patient home or proceeding with a cesarean delivery. Expectant management allows for the possibility of spontaneous version. Alternatively, cesarean delivery may be performed at the time of the failed ECV, especially if regional anesthesia is used and the patient is already in the delivery room (see Regional anesthesia). This would minimize the risk of a second regional analgesia.

In those with an unsuccessful ECV, the practitioner may send the patient home, if less than 39 weeks, with plans for either a vaginal breech delivery or scheduled cesarean after 39 weeks. Expectant management allows for the possibility of a spontaneous version. Alternatively, if ECV is attempted after 39 weeks, cesarean delivery may be performed at the time of the failed ECV, especially if regional anesthesia is used and the patient is already in the delivery room (see Regional anesthesia). This would minimize the risk of a second regional analgesia.

Success rate

Success rates vary widely but range from 35% to 86% (average success rate in the 2004 National Vital Statistics was 58%). Improved success rates occur with multiparity, earlier gestational age, frank (versus complete or footling) breech presentation, transverse lie, and in African American patients.

Opinions differ regarding the influence of maternal weight, placental position, and amniotic fluid volume. Some practitioners find that thinner patients, posterior placentas, and adequate fluid volumes facilitate successful ECV. However, both patients and physicians need to be prepared for an unsuccessful ECV; version failure is not necessarily a reflection of the skill of the practitioner.

Zhang et al reviewed 25 studies of ECV in the United States, Europe, Africa, and Israel. [ 17 ] The average success rate in the United States was 65%. Of successful ECVs, 2.5% reverted back to breech presentation (other estimates range from 3% to 5%), while 2% of unsuccessful ECVs had spontaneous version to cephalic presentation prior to labor (other estimates range from 12% to 26%). Spontaneous version rates depend on the gestational age when the breech is discovered, with earlier breeches more likely to undergo spontaneous version.

A prospective study conducted in Germany by Zielbauer et al demonstrated an overall success rate of 22.4% for ECV among 353 patients with a singleton fetus in breech presentation. ECV was performed at 38 weeks of gestation. Factors found to increase the likelihood of success were a later week of gestation, abundant amniotic fluid, fundal and anterior placental location, and an oblique lie. [ 18 ]

A systematic review in 2015 looked at the effectiveness of ECV with eight randomized trials of ECV at term. Compared to women with no attempt at ECV, ECV reduced non-cephalic presentation at birth by 60% and reduced cesarean sections by 40% in the same group. [ 19 ] Although the rate of cesarean section is lower when ECV is performed than if not, the overall rate of cesarean section remains nearly twice as high after successful ECV due to both dystocia and non-reassuring fetal heart rate patterns. [ 20 ] Nulliparity was the only factor shown in follow-up to increase the risk of instrumental delivery following successful ECV. [ 21 ]

While most studies of ECV have been performed in university hospitals, Cook showed that ECV has also been effective in the private practice setting. [ 22 ] Of 65 patients with term breeches, 60 were offered ECV. ECV was successful in 32 (53%) of the 60 patients, with vaginal delivery in 23 (72%) of the 32 patients. Of the remaining breech fetuses believed to be candidates for vaginal delivery, 8 (80%) had successful vaginal delivery. The overall vaginal delivery rate was 48% (31 of 65 patients), with no significant morbidity.

Cost analysis

In 1995, Gifford et al performed a cost analysis of 4 options for breech presentations at term: (1) ECV attempt on all breeches, with attempted vaginal breech delivery for selected persistent breeches; (2) ECV on all breeches, with cesarean delivery for persistent breeches; (3) trial of labor for selected breeches, with scheduled cesarean delivery for all others; and (4) scheduled cesarean delivery for all breeches prior to labor. [ 23 ]

ECV attempt on all breeches with attempted vaginal breech delivery on selected persistent breeches was associated with the lowest cesarean delivery rate and was the most cost-effective approach. The second most cost-effective approach was ECV attempt on all breeches, with cesarean delivery for persistent breeches.

Uncommon risks of ECV include fractured fetal bones, precipitation of labor or premature rupture of membranes , abruptio placentae , fetomaternal hemorrhage (0-5%), and cord entanglement (< 1.5%). A more common risk of ECV is transient slowing of the fetal heart rate (in as many as 40% of cases). This risk is believed to be a vagal response to head compression with ECV. It usually resolves within a few minutes after cessation of the ECV attempt and is not usually associated with adverse sequelae for the fetus.

Trials have not been large enough to determine whether the overall risk of perinatal mortality is increased with ECV. The Cochrane review from 2015 reported perinatal death in 2 of 644 in ECV and 6 of 661 in the group that did not attempt ECV. [ 19 ]

A 2016 Practice Bulletin by ACOG recommended that all women who are near term with breech presentations should be offered an ECV attempt if there are no contraindications (see Contraindications below). [ 24 ] ACOG guidelines issued in 2020 recommend that ECV should be performed starting at 37+0 weeks, in order to reduce the likelihood of reversion and to increase the rate of spontaneous version. [ 25 ]

ACOG recommends that ECV be offered as an alternative to a planned cesarean section for a patient who has a term singleton breech fetus, wishes to have a planned vaginal delivery of a vertex-presenting fetus, and has no contraindications. ACOG also advises that ECV be attempted only in settings where cesarean delivery services are available. [ 26 ]

ECV is usually not performed on preterm breeches because they are more likely to undergo spontaneous version to cephalic presentation and are more likely to revert to breech after successful ECV (approximately 50%). Earlier studies of preterm ECV did not show a difference in the rates of breech presentations at term or overall rates of cesarean delivery. Additionally, if complications of ECV were to arise that warranted emergent delivery, it would result in a preterm neonate with its inherent risks. The Early External Cephalic Version (ECV) 2 trial was an international, multicentered, randomized clinical trial that compared ECV performed at 34-35 weeks’ gestation compared with 37 weeks’ gestation or more. [ 27 ] Early ECV increased the chance of cephalic presentation at birth; however, no difference in cesarean delivery rates was noted, along with a nonstatistical increase in preterm births.

A systematic review looked at 5 studies of ECV completed prior to 37 weeks and concluded that compared with no ECV attempt, ECV commenced before term reduces the non-cephalic presentation at birth, however early ECV may increase the risk of late preterm birth. [ 28 ]