Why is it important to do a literature review in research?

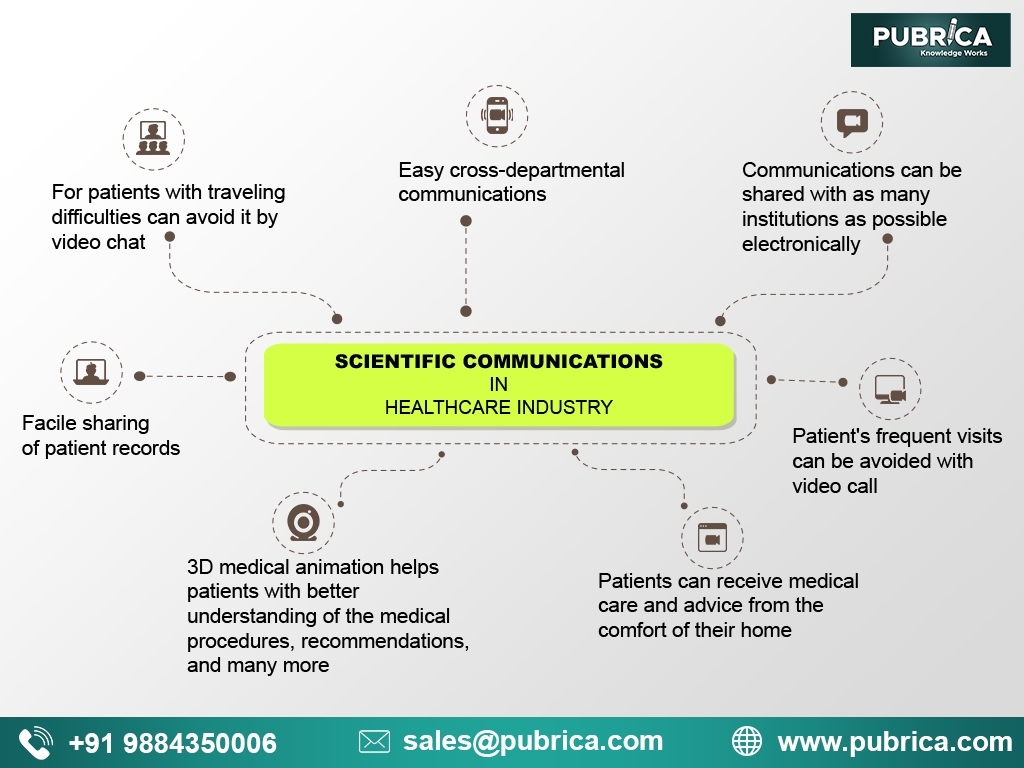

The importance of scientific communication in the healthcare industry

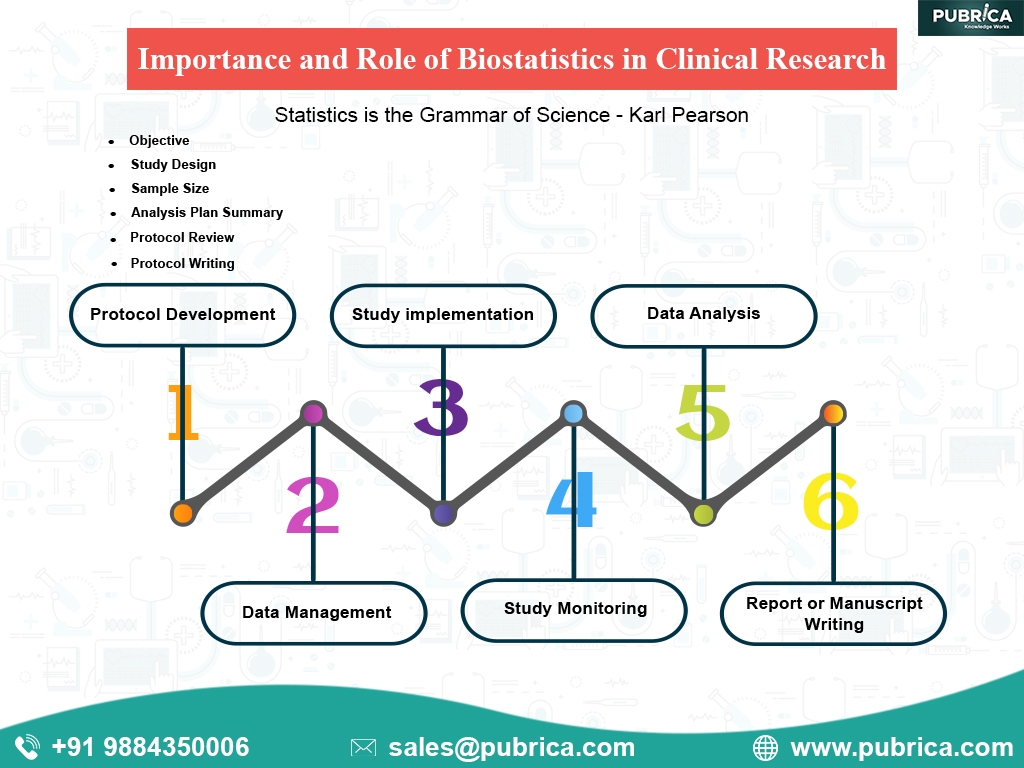

The Importance and Role of Biostatistics in Clinical Research

“A substantive, thorough, sophisticated literature review is a precondition for doing substantive, thorough, sophisticated research”. Boote and Baile 2005

Authors of manuscripts treat writing a literature review as a routine work or a mere formality. But a seasoned one knows the purpose and importance of a well-written literature review. Since it is one of the basic needs for researches at any level, they have to be done vigilantly. Only then the reader will know that the basics of research have not been neglected.

The aim of any literature review is to summarize and synthesize the arguments and ideas of existing knowledge in a particular field without adding any new contributions. Being built on existing knowledge they help the researcher to even turn the wheels of the topic of research. It is possible only with profound knowledge of what is wrong in the existing findings in detail to overpower them. For other researches, the literature review gives the direction to be headed for its success.

The common perception of literature review and reality:

As per the common belief, literature reviews are only a summary of the sources related to the research. And many authors of scientific manuscripts believe that they are only surveys of what are the researches are done on the chosen topic. But on the contrary, it uses published information from pertinent and relevant sources like

- Scholarly books

- Scientific papers

- Latest studies in the field

- Established school of thoughts

- Relevant articles from renowned scientific journals

and many more for a field of study or theory or a particular problem to do the following:

- Summarize into a brief account of all information

- Synthesize the information by restructuring and reorganizing

- Critical evaluation of a concept or a school of thought or ideas

- Familiarize the authors to the extent of knowledge in the particular field

- Encapsulate

- Compare & contrast

By doing the above on the relevant information, it provides the reader of the scientific manuscript with the following for a better understanding of it:

- It establishes the authors’ in-depth understanding and knowledge of their field subject

- It gives the background of the research

- Portrays the scientific manuscript plan of examining the research result

- Illuminates on how the knowledge has changed within the field

- Highlights what has already been done in a particular field

- Information of the generally accepted facts, emerging and current state of the topic of research

- Identifies the research gap that is still unexplored or under-researched fields

- Demonstrates how the research fits within a larger field of study

- Provides an overview of the sources explored during the research of a particular topic

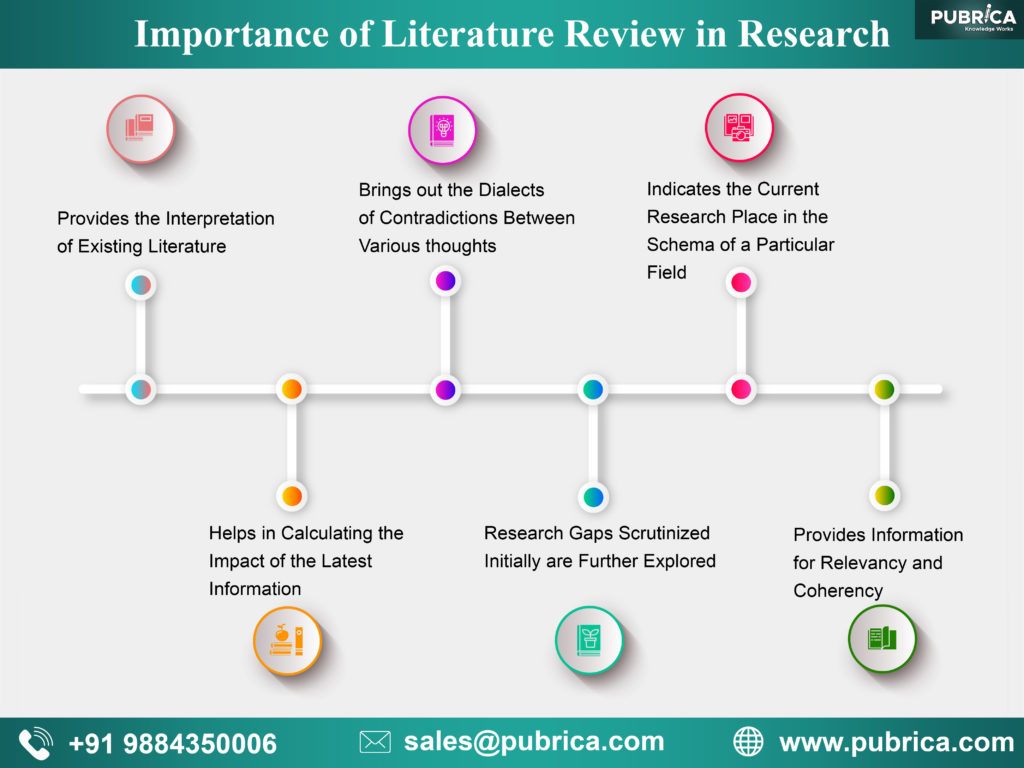

Importance of literature review in research:

The importance of literature review in scientific manuscripts can be condensed into an analytical feature to enable the multifold reach of its significance. It adds value to the legitimacy of the research in many ways:

- Provides the interpretation of existing literature in light of updated developments in the field to help in establishing the consistency in knowledge and relevancy of existing materials

- It helps in calculating the impact of the latest information in the field by mapping their progress of knowledge.

- It brings out the dialects of contradictions between various thoughts within the field to establish facts

- The research gaps scrutinized initially are further explored to establish the latest facts of theories to add value to the field

- Indicates the current research place in the schema of a particular field

- Provides information for relevancy and coherency to check the research

- Apart from elucidating the continuance of knowledge, it also points out areas that require further investigation and thus aid as a starting point of any future research

- Justifies the research and sets up the research question

- Sets up a theoretical framework comprising the concepts and theories of the research upon which its success can be judged

- Helps to adopt a more appropriate methodology for the research by examining the strengths and weaknesses of existing research in the same field

- Increases the significance of the results by comparing it with the existing literature

- Provides a point of reference by writing the findings in the scientific manuscript

- Helps to get the due credit from the audience for having done the fact-finding and fact-checking mission in the scientific manuscripts

- The more the reference of relevant sources of it could increase more of its trustworthiness with the readers

- Helps to prevent plagiarism by tailoring and uniquely tweaking the scientific manuscript not to repeat other’s original idea

- By preventing plagiarism , it saves the scientific manuscript from rejection and thus also saves a lot of time and money

- Helps to evaluate, condense and synthesize gist in the author’s own words to sharpen the research focus

- Helps to compare and contrast to show the originality and uniqueness of the research than that of the existing other researches

- Rationalizes the need for conducting the particular research in a specified field

- Helps to collect data accurately for allowing any new methodology of research than the existing ones

- Enables the readers of the manuscript to answer the following questions of its readers for its better chances for publication

- What do the researchers know?

- What do they not know?

- Is the scientific manuscript reliable and trustworthy?

- What are the knowledge gaps of the researcher?

22. It helps the readers to identify the following for further reading of the scientific manuscript:

- What has been already established, discredited and accepted in the particular field of research

- Areas of controversy and conflicts among different schools of thought

- Unsolved problems and issues in the connected field of research

- The emerging trends and approaches

- How the research extends, builds upon and leaves behind from the previous research

A profound literature review with many relevant sources of reference will enhance the chances of the scientific manuscript publication in renowned and reputed scientific journals .

References:

http://www.math.montana.edu/jobo/phdprep/phd6.pdf

journal Publishing services | Scientific Editing Services | Medical Writing Services | scientific research writing service | Scientific communication services

Related Topics:

Meta Analysis

Scientific Research Paper Writing

Medical Research Paper Writing

Scientific Communication in healthcare

pubrica academy

Related posts.

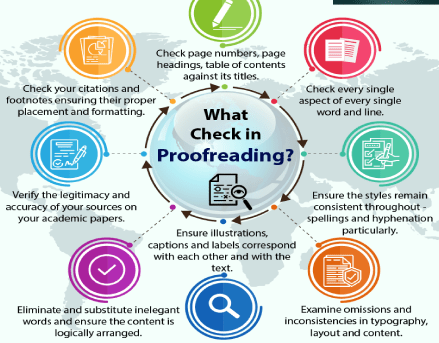

Importance Of Proofreading For Scientific Writing Methods and Significance

Statistical analyses of case-control studies

Selecting material (e.g. excipient, active pharmaceutical ingredient, packaging material) for drug development

Comments are closed.

Literature Review - what is a Literature Review, why it is important and how it is done

What are literature reviews, goals of literature reviews, types of literature reviews, about this guide/licence.

- Strategies to Find Sources

- Evaluating Literature Reviews and Sources

- Tips for Writing Literature Reviews

- Writing Literature Review: Useful Sites

- Citation Resources

- Other Academic Writings

- Useful Resources

Help is Just a Click Away

Search our FAQ Knowledge base, ask a question, chat, send comments...

Go to LibAnswers

What is a literature review? "A literature review is an account of what has been published on a topic by accredited scholars and researchers. In writing the literature review, your purpose is to convey to your reader what knowledge and ideas have been established on a topic, and what their strengths and weaknesses are. As a piece of writing, the literature review must be defined by a guiding concept (e.g., your research objective, the problem or issue you are discussing, or your argumentative thesis). It is not just a descriptive list of the material available, or a set of summaries. " - Quote from Taylor, D. (n.d) "The literature review: A few tips on conducting it"

Source NC State University Libraries. This video is published under a Creative Commons 3.0 BY-NC-SA US license.

What are the goals of creating a Literature Review?

- To develop a theory or evaluate an existing theory

- To summarize the historical or existing state of a research topic

- Identify a problem in a field of research

- Baumeister, R.F. & Leary, M.R. (1997). "Writing narrative literature reviews," Review of General Psychology , 1(3), 311-320.

When do you need to write a Literature Review?

- When writing a prospectus or a thesis/dissertation

- When writing a research paper

- When writing a grant proposal

In all these cases you need to dedicate a chapter in these works to showcase what have been written about your research topic and to point out how your own research will shed a new light into these body of scholarship.

Literature reviews are also written as standalone articles as a way to survey a particular research topic in-depth. This type of literature reviews look at a topic from a historical perspective to see how the understanding of the topic have change through time.

What kinds of literature reviews are written?

- Narrative Review: The purpose of this type of review is to describe the current state of the research on a specific topic/research and to offer a critical analysis of the literature reviewed. Studies are grouped by research/theoretical categories, and themes and trends, strengths and weakness, and gaps are identified. The review ends with a conclusion section which summarizes the findings regarding the state of the research of the specific study, the gaps identify and if applicable, explains how the author's research will address gaps identify in the review and expand the knowledge on the topic reviewed.

- Book review essays/ Historiographical review essays : This is a type of review that focus on a small set of research books on a particular topic " to locate these books within current scholarship, critical methodologies, and approaches" in the field. - LARR

- Systematic review : "The authors of a systematic review use a specific procedure to search the research literature, select the studies to include in their review, and critically evaluate the studies they find." (p. 139). Nelson, L.K. (2013). Research in Communication Sciences and Disorders . San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing.

- Meta-analysis : "Meta-analysis is a method of reviewing research findings in a quantitative fashion by transforming the data from individual studies into what is called an effect size and then pooling and analyzing this information. The basic goal in meta-analysis is to explain why different outcomes have occurred in different studies." (p. 197). Roberts, M.C. & Ilardi, S.S. (2003). Handbook of Research Methods in Clinical Psychology . Malden, MA: Blackwell Pub.

- Meta-synthesis : "Qualitative meta-synthesis is a type of qualitative study that uses as data the findings from other qualitative studies linked by the same or related topic." (p.312). Zimmer, L. (2006). "Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts," Journal of Advanced Nursing , 53(3), 311-318.

Guide adapted from "Literature Review" , a guide developed by Marisol Ramos used under CC BY 4.0 /modified from original.

- Next: Strategies to Find Sources >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 10:56 AM

- URL: https://lit.libguides.com/Literature-Review

The Library, Technological University of the Shannon: Midwest

What is a Literature Review? How to Write It (with Examples)

A literature review is a critical analysis and synthesis of existing research on a particular topic. It provides an overview of the current state of knowledge, identifies gaps, and highlights key findings in the literature. 1 The purpose of a literature review is to situate your own research within the context of existing scholarship, demonstrating your understanding of the topic and showing how your work contributes to the ongoing conversation in the field. Learning how to write a literature review is a critical tool for successful research. Your ability to summarize and synthesize prior research pertaining to a certain topic demonstrates your grasp on the topic of study, and assists in the learning process.

Table of Contents

- What is the purpose of literature review?

- a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

- b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

- c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

- d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

How to write a good literature review

- Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Select Databases for Searches:

- Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Review the Literature:

- Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

- Frequently asked questions

What is a literature review?

A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with the existing literature, establishes the context for their own research, and contributes to scholarly conversations on the topic. One of the purposes of a literature review is also to help researchers avoid duplicating previous work and ensure that their research is informed by and builds upon the existing body of knowledge.

What is the purpose of literature review?

A literature review serves several important purposes within academic and research contexts. Here are some key objectives and functions of a literature review: 2

1. Contextualizing the Research Problem: The literature review provides a background and context for the research problem under investigation. It helps to situate the study within the existing body of knowledge.

2. Identifying Gaps in Knowledge: By identifying gaps, contradictions, or areas requiring further research, the researcher can shape the research question and justify the significance of the study. This is crucial for ensuring that the new research contributes something novel to the field.

Find academic papers related to your research topic faster. Try Research on Paperpal

3. Understanding Theoretical and Conceptual Frameworks: Literature reviews help researchers gain an understanding of the theoretical and conceptual frameworks used in previous studies. This aids in the development of a theoretical framework for the current research.

4. Providing Methodological Insights: Another purpose of literature reviews is that it allows researchers to learn about the methodologies employed in previous studies. This can help in choosing appropriate research methods for the current study and avoiding pitfalls that others may have encountered.

5. Establishing Credibility: A well-conducted literature review demonstrates the researcher’s familiarity with existing scholarship, establishing their credibility and expertise in the field. It also helps in building a solid foundation for the new research.

6. Informing Hypotheses or Research Questions: The literature review guides the formulation of hypotheses or research questions by highlighting relevant findings and areas of uncertainty in existing literature.

Literature review example

Let’s delve deeper with a literature review example: Let’s say your literature review is about the impact of climate change on biodiversity. You might format your literature review into sections such as the effects of climate change on habitat loss and species extinction, phenological changes, and marine biodiversity. Each section would then summarize and analyze relevant studies in those areas, highlighting key findings and identifying gaps in the research. The review would conclude by emphasizing the need for further research on specific aspects of the relationship between climate change and biodiversity. The following literature review template provides a glimpse into the recommended literature review structure and content, demonstrating how research findings are organized around specific themes within a broader topic.

Literature Review on Climate Change Impacts on Biodiversity:

Climate change is a global phenomenon with far-reaching consequences, including significant impacts on biodiversity. This literature review synthesizes key findings from various studies:

a. Habitat Loss and Species Extinction:

Climate change-induced alterations in temperature and precipitation patterns contribute to habitat loss, affecting numerous species (Thomas et al., 2004). The review discusses how these changes increase the risk of extinction, particularly for species with specific habitat requirements.

b. Range Shifts and Phenological Changes:

Observations of range shifts and changes in the timing of biological events (phenology) are documented in response to changing climatic conditions (Parmesan & Yohe, 2003). These shifts affect ecosystems and may lead to mismatches between species and their resources.

c. Ocean Acidification and Coral Reefs:

The review explores the impact of climate change on marine biodiversity, emphasizing ocean acidification’s threat to coral reefs (Hoegh-Guldberg et al., 2007). Changes in pH levels negatively affect coral calcification, disrupting the delicate balance of marine ecosystems.

d. Adaptive Strategies and Conservation Efforts:

Recognizing the urgency of the situation, the literature review discusses various adaptive strategies adopted by species and conservation efforts aimed at mitigating the impacts of climate change on biodiversity (Hannah et al., 2007). It emphasizes the importance of interdisciplinary approaches for effective conservation planning.

Strengthen your literature review with factual insights. Try Research on Paperpal for free!

Writing a literature review involves summarizing and synthesizing existing research on a particular topic. A good literature review format should include the following elements.

Introduction: The introduction sets the stage for your literature review, providing context and introducing the main focus of your review.

- Opening Statement: Begin with a general statement about the broader topic and its significance in the field.

- Scope and Purpose: Clearly define the scope of your literature review. Explain the specific research question or objective you aim to address.

- Organizational Framework: Briefly outline the structure of your literature review, indicating how you will categorize and discuss the existing research.

- Significance of the Study: Highlight why your literature review is important and how it contributes to the understanding of the chosen topic.

- Thesis Statement: Conclude the introduction with a concise thesis statement that outlines the main argument or perspective you will develop in the body of the literature review.

Body: The body of the literature review is where you provide a comprehensive analysis of existing literature, grouping studies based on themes, methodologies, or other relevant criteria.

- Organize by Theme or Concept: Group studies that share common themes, concepts, or methodologies. Discuss each theme or concept in detail, summarizing key findings and identifying gaps or areas of disagreement.

- Critical Analysis: Evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of each study. Discuss the methodologies used, the quality of evidence, and the overall contribution of each work to the understanding of the topic.

- Synthesis of Findings: Synthesize the information from different studies to highlight trends, patterns, or areas of consensus in the literature.

- Identification of Gaps: Discuss any gaps or limitations in the existing research and explain how your review contributes to filling these gaps.

- Transition between Sections: Provide smooth transitions between different themes or concepts to maintain the flow of your literature review.

Write and Cite as you go with Paperpal Research. Start now for free.

Conclusion: The conclusion of your literature review should summarize the main findings, highlight the contributions of the review, and suggest avenues for future research.

- Summary of Key Findings: Recap the main findings from the literature and restate how they contribute to your research question or objective.

- Contributions to the Field: Discuss the overall contribution of your literature review to the existing knowledge in the field.

- Implications and Applications: Explore the practical implications of the findings and suggest how they might impact future research or practice.

- Recommendations for Future Research: Identify areas that require further investigation and propose potential directions for future research in the field.

- Final Thoughts: Conclude with a final reflection on the importance of your literature review and its relevance to the broader academic community.

Conducting a literature review

Conducting a literature review is an essential step in research that involves reviewing and analyzing existing literature on a specific topic. It’s important to know how to do a literature review effectively, so here are the steps to follow: 1

Choose a Topic and Define the Research Question:

- Select a topic that is relevant to your field of study.

- Clearly define your research question or objective. Determine what specific aspect of the topic do you want to explore?

Decide on the Scope of Your Review:

- Determine the timeframe for your literature review. Are you focusing on recent developments, or do you want a historical overview?

- Consider the geographical scope. Is your review global, or are you focusing on a specific region?

- Define the inclusion and exclusion criteria. What types of sources will you include? Are there specific types of studies or publications you will exclude?

Select Databases for Searches:

- Identify relevant databases for your field. Examples include PubMed, IEEE Xplore, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar.

- Consider searching in library catalogs, institutional repositories, and specialized databases related to your topic.

Conduct Searches and Keep Track:

- Develop a systematic search strategy using keywords, Boolean operators (AND, OR, NOT), and other search techniques.

- Record and document your search strategy for transparency and replicability.

- Keep track of the articles, including publication details, abstracts, and links. Use citation management tools like EndNote, Zotero, or Mendeley to organize your references.

Review the Literature:

- Evaluate the relevance and quality of each source. Consider the methodology, sample size, and results of studies.

- Organize the literature by themes or key concepts. Identify patterns, trends, and gaps in the existing research.

- Summarize key findings and arguments from each source. Compare and contrast different perspectives.

- Identify areas where there is a consensus in the literature and where there are conflicting opinions.

- Provide critical analysis and synthesis of the literature. What are the strengths and weaknesses of existing research?

Organize and Write Your Literature Review:

- Literature review outline should be based on themes, chronological order, or methodological approaches.

- Write a clear and coherent narrative that synthesizes the information gathered.

- Use proper citations for each source and ensure consistency in your citation style (APA, MLA, Chicago, etc.).

- Conclude your literature review by summarizing key findings, identifying gaps, and suggesting areas for future research.

Whether you’re exploring a new research field or finding new angles to develop an existing topic, sifting through hundreds of papers can take more time than you have to spare. But what if you could find science-backed insights with verified citations in seconds? That’s the power of Paperpal’s new Research feature!

How to write a literature review faster with Paperpal?

Paperpal, an AI writing assistant, integrates powerful academic search capabilities within its writing platform. With the Research feature, you get 100% factual insights, with citations backed by 250M+ verified research articles, directly within your writing interface with the option to save relevant references in your Citation Library. By eliminating the need to switch tabs to find answers to all your research questions, Paperpal saves time and helps you stay focused on your writing.

Here’s how to use the Research feature:

- Ask a question: Get started with a new document on paperpal.com. Click on the “Research” feature and type your question in plain English. Paperpal will scour over 250 million research articles, including conference papers and preprints, to provide you with accurate insights and citations.

- Review and Save: Paperpal summarizes the information, while citing sources and listing relevant reads. You can quickly scan the results to identify relevant references and save these directly to your built-in citations library for later access.

- Cite with Confidence: Paperpal makes it easy to incorporate relevant citations and references into your writing, ensuring your arguments are well-supported by credible sources. This translates to a polished, well-researched literature review.

The literature review sample and detailed advice on writing and conducting a review will help you produce a well-structured report. But remember that a good literature review is an ongoing process, and it may be necessary to revisit and update it as your research progresses. By combining effortless research with an easy citation process, Paperpal Research streamlines the literature review process and empowers you to write faster and with more confidence. Try Paperpal Research now and see for yourself.

Frequently asked questions

A literature review is a critical and comprehensive analysis of existing literature (published and unpublished works) on a specific topic or research question and provides a synthesis of the current state of knowledge in a particular field. A well-conducted literature review is crucial for researchers to build upon existing knowledge, avoid duplication of efforts, and contribute to the advancement of their field. It also helps researchers situate their work within a broader context and facilitates the development of a sound theoretical and conceptual framework for their studies.

Literature review is a crucial component of research writing, providing a solid background for a research paper’s investigation. The aim is to keep professionals up to date by providing an understanding of ongoing developments within a specific field, including research methods, and experimental techniques used in that field, and present that knowledge in the form of a written report. Also, the depth and breadth of the literature review emphasizes the credibility of the scholar in his or her field.

Before writing a literature review, it’s essential to undertake several preparatory steps to ensure that your review is well-researched, organized, and focused. This includes choosing a topic of general interest to you and doing exploratory research on that topic, writing an annotated bibliography, and noting major points, especially those that relate to the position you have taken on the topic.

Literature reviews and academic research papers are essential components of scholarly work but serve different purposes within the academic realm. 3 A literature review aims to provide a foundation for understanding the current state of research on a particular topic, identify gaps or controversies, and lay the groundwork for future research. Therefore, it draws heavily from existing academic sources, including books, journal articles, and other scholarly publications. In contrast, an academic research paper aims to present new knowledge, contribute to the academic discourse, and advance the understanding of a specific research question. Therefore, it involves a mix of existing literature (in the introduction and literature review sections) and original data or findings obtained through research methods.

Literature reviews are essential components of academic and research papers, and various strategies can be employed to conduct them effectively. If you want to know how to write a literature review for a research paper, here are four common approaches that are often used by researchers. Chronological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the chronological order of publication. It helps to trace the development of a topic over time, showing how ideas, theories, and research have evolved. Thematic Review: Thematic reviews focus on identifying and analyzing themes or topics that cut across different studies. Instead of organizing the literature chronologically, it is grouped by key themes or concepts, allowing for a comprehensive exploration of various aspects of the topic. Methodological Review: This strategy involves organizing the literature based on the research methods employed in different studies. It helps to highlight the strengths and weaknesses of various methodologies and allows the reader to evaluate the reliability and validity of the research findings. Theoretical Review: A theoretical review examines the literature based on the theoretical frameworks used in different studies. This approach helps to identify the key theories that have been applied to the topic and assess their contributions to the understanding of the subject. It’s important to note that these strategies are not mutually exclusive, and a literature review may combine elements of more than one approach. The choice of strategy depends on the research question, the nature of the literature available, and the goals of the review. Additionally, other strategies, such as integrative reviews or systematic reviews, may be employed depending on the specific requirements of the research.

The literature review format can vary depending on the specific publication guidelines. However, there are some common elements and structures that are often followed. Here is a general guideline for the format of a literature review: Introduction: Provide an overview of the topic. Define the scope and purpose of the literature review. State the research question or objective. Body: Organize the literature by themes, concepts, or chronology. Critically analyze and evaluate each source. Discuss the strengths and weaknesses of the studies. Highlight any methodological limitations or biases. Identify patterns, connections, or contradictions in the existing research. Conclusion: Summarize the key points discussed in the literature review. Highlight the research gap. Address the research question or objective stated in the introduction. Highlight the contributions of the review and suggest directions for future research.

Both annotated bibliographies and literature reviews involve the examination of scholarly sources. While annotated bibliographies focus on individual sources with brief annotations, literature reviews provide a more in-depth, integrated, and comprehensive analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. The key differences are as follows:

| Annotated Bibliography | Literature Review | |

| Purpose | List of citations of books, articles, and other sources with a brief description (annotation) of each source. | Comprehensive and critical analysis of existing literature on a specific topic. |

| Focus | Summary and evaluation of each source, including its relevance, methodology, and key findings. | Provides an overview of the current state of knowledge on a particular subject and identifies gaps, trends, and patterns in existing literature. |

| Structure | Each citation is followed by a concise paragraph (annotation) that describes the source’s content, methodology, and its contribution to the topic. | The literature review is organized thematically or chronologically and involves a synthesis of the findings from different sources to build a narrative or argument. |

| Length | Typically 100-200 words | Length of literature review ranges from a few pages to several chapters |

| Independence | Each source is treated separately, with less emphasis on synthesizing the information across sources. | The writer synthesizes information from multiple sources to present a cohesive overview of the topic. |

References

- Denney, A. S., & Tewksbury, R. (2013). How to write a literature review. Journal of criminal justice education , 24 (2), 218-234.

- Pan, M. L. (2016). Preparing literature reviews: Qualitative and quantitative approaches . Taylor & Francis.

- Cantero, C. (2019). How to write a literature review. San José State University Writing Center .

Paperpal is an AI writing assistant that help academics write better, faster with real-time suggestions for in-depth language and grammar correction. Trained on millions of research manuscripts enhanced by professional academic editors, Paperpal delivers human precision at machine speed.

Try it for free or upgrade to Paperpal Prime , which unlocks unlimited access to premium features like academic translation, paraphrasing, contextual synonyms, consistency checks and more. It’s like always having a professional academic editor by your side! Go beyond limitations and experience the future of academic writing. Get Paperpal Prime now at just US$19 a month!

Related Reads:

- Empirical Research: A Comprehensive Guide for Academics

- How to Write a Scientific Paper in 10 Steps

- How Long Should a Chapter Be?

- How to Use Paperpal to Generate Emails & Cover Letters?

6 Tips for Post-Doc Researchers to Take Their Career to the Next Level

Self-plagiarism in research: what it is and how to avoid it, you may also like, the ai revolution: authors’ role in upholding academic..., the future of academia: how ai tools are..., how to write a research proposal: (with examples..., how to write your research paper in apa..., how to choose a dissertation topic, how to write a phd research proposal, how to write an academic paragraph (step-by-step guide), five things authors need to know when using..., 7 best referencing tools and citation management software..., maintaining academic integrity with paperpal’s generative ai writing....

- University of Texas Libraries

Literature Reviews

- What is a literature review?

- Steps in the Literature Review Process

- Define your research question

- Determine inclusion and exclusion criteria

- Choose databases and search

- Review Results

- Synthesize Results

- Analyze Results

- Librarian Support

- Artificial Intelligence (AI) Tools

What is a Literature Review?

A literature or narrative review is a comprehensive review and analysis of the published literature on a specific topic or research question. The literature that is reviewed contains: books, articles, academic articles, conference proceedings, association papers, and dissertations. It contains the most pertinent studies and points to important past and current research and practices. It provides background and context, and shows how your research will contribute to the field.

A literature review should:

- Provide a comprehensive and updated review of the literature;

- Explain why this review has taken place;

- Articulate a position or hypothesis;

- Acknowledge and account for conflicting and corroborating points of view

From S age Research Methods

Purpose of a Literature Review

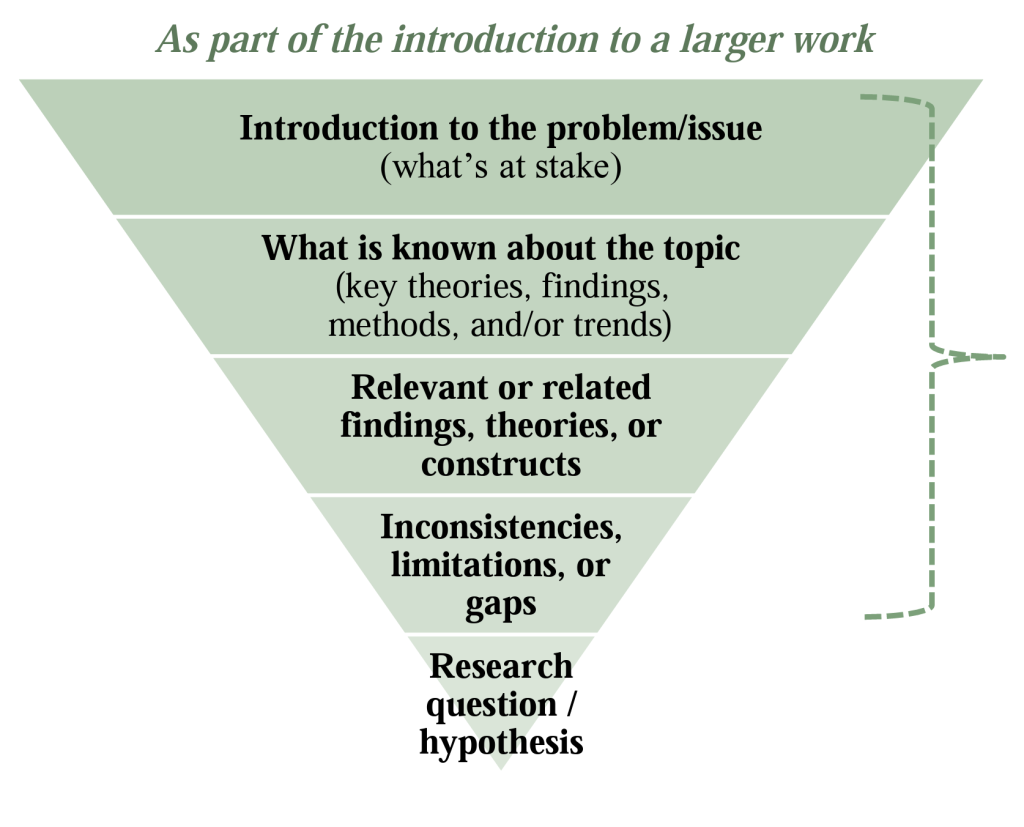

A literature review can be written as an introduction to a study to:

- Demonstrate how a study fills a gap in research

- Compare a study with other research that's been done

Or it can be a separate work (a research article on its own) which:

- Organizes or describes a topic

- Describes variables within a particular issue/problem

Limitations of a Literature Review

Some of the limitations of a literature review are:

- It's a snapshot in time. Unlike other reviews, this one has beginning, a middle and an end. There may be future developments that could make your work less relevant.

- It may be too focused. Some niche studies may miss the bigger picture.

- It can be difficult to be comprehensive. There is no way to make sure all the literature on a topic was considered.

- It is easy to be biased if you stick to top tier journals. There may be other places where people are publishing exemplary research. Look to open access publications and conferences to reflect a more inclusive collection. Also, make sure to include opposing views (and not just supporting evidence).

Source: Grant, Maria J., and Andrew Booth. “A Typology of Reviews: An Analysis of 14 Review Types and Associated Methodologies.” Health Information & Libraries Journal, vol. 26, no. 2, June 2009, pp. 91–108. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

Meryl Brodsky : Communication and Information Studies

Hannah Chapman Tripp : Biology, Neuroscience

Carolyn Cunningham : Human Development & Family Sciences, Psychology, Sociology

Larayne Dallas : Engineering

Janelle Hedstrom : Special Education, Curriculum & Instruction, Ed Leadership & Policy

Susan Macicak : Linguistics

Imelda Vetter : Dell Medical School

For help in other subject areas, please see the guide to library specialists by subject .

Periodically, UT Libraries runs a workshop covering the basics and library support for literature reviews. While we try to offer these once per academic year, we find providing the recording to be helpful to community members who have missed the session. Following is the most recent recording of the workshop, Conducting a Literature Review. To view the recording, a UT login is required.

- October 26, 2022 recording

- Last Updated: Jul 30, 2024 9:33 AM

- URL: https://guides.lib.utexas.edu/literaturereviews

A Guide to Literature Reviews

Importance of a good literature review.

- Conducting the Literature Review

- Structure and Writing Style

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Citation Management Software This link opens in a new window

- Acknowledgements

A literature review is not only a summary of key sources, but has an organizational pattern which combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

- << Previous: Definition

- Next: Conducting the Literature Review >>

- Last Updated: Jul 3, 2024 3:13 PM

- URL: https://libguides.mcmaster.ca/litreview

Essays, Literature Reviews and Reports - Skills Guide

Literature review.

- Downloadable Resources

- Further Reading

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a collection of literature that is analysed (reviewed) and compared against each other to demonstrate an understanding of a topic. In a literature review you identify relevant theories and previous research in the area. Bell states that "literature reviews should be succinct and.. give a picture of the state of knowledge and major questions in your topic area."

Literature reviews are usually a part of a dissertation, although some modules may require a standalone literature review.

Why are literature reviews important?

Literature reviews are important as they allow you to gain a thorough awareness and understanding of current work and perspectives in a research area to support and justify your research, as well as illustrating that there is a research gap and assisting in the analysis and interpretation of data.

What should I put into a literature review?

- The historical context.

- The contemporary context of your research.

- A discussion of the relevant underpinning concepts and theories.

- Definitions of the key terminology used in your own work.

- Current research in the field that can be challenged or extended by your own research.

- Justification of the significance of your research.

How do I structure a literature review?

Look carefully at what is expected from you for your literature review. Sometimes they might focus heavily on one piece of literature, while others may focus on two or three, and some would like a vast body of literature to be included. Whatever the expectation, they usually follow the same structure as an essay:

10% Introduction

80% Main Body

10% Conclusion

The introduction should explain how your literature review is organised.

The main body should be made up of headings and sub headings that map out your argument.

The conclusion should summarise the key arguments in a concise way.

When should I start writing my literature review?

Starting writing your literature review as early as possible can help you in understanding the research and understanding how it will be used. This will help in creating an overall structure when writing later versions of the literature review and in comparing and linking different pieces of research.

There are example essay extracts available on Do It Write ( click here ) to help you understand what they're asking from you.

- << Previous: Essay

- Next: Report >>

- Last Updated: Aug 23, 2023 3:50 PM

- URL: https://libguides.derby.ac.uk/essay-litreview-report

Literature Review: Purpose of a Literature Review

- Literature Review

- Purpose of a Literature Review

- Work in Progress

- Compiling & Writing

- Books, Articles, & Web Pages

- Types of Literature Reviews

- Departmental Differences

- Citation Styles & Plagiarism

- Know the Difference! Systematic Review vs. Literature Review

The purpose of a literature review is to:

- Provide a foundation of knowledge on a topic

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication and give credit to other researchers

- Identify inconstancies: gaps in research, conflicts in previous studies, open questions left from other research

- Identify the need for additional research (justifying your research)

- Identify the relationship of works in the context of their contribution to the topic and other works

- Place your own research within the context of existing literature, making a case for why further study is needed.

Videos & Tutorials

VIDEO: What is the role of a literature review in research? What's it mean to "review" the literature? Get the big picture of what to expect as part of the process. This video is published under a Creative Commons 3.0 BY-NC-SA US license. License, credits, and contact information can be found here: https://www.lib.ncsu.edu/tutorials/litreview/

Elements in a Literature Review

- Elements in a Literature Review txt of infographic

- << Previous: Literature Review

- Next: Searching >>

- Last Updated: Oct 19, 2023 12:07 PM

- URL: https://uscupstate.libguides.com/Literature_Review

Frequently asked questions

What is the purpose of a literature review.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

Frequently asked questions: Academic writing

A rhetorical tautology is the repetition of an idea of concept using different words.

Rhetorical tautologies occur when additional words are used to convey a meaning that has already been expressed or implied. For example, the phrase “armed gunman” is a tautology because a “gunman” is by definition “armed.”

A logical tautology is a statement that is always true because it includes all logical possibilities.

Logical tautologies often take the form of “either/or” statements (e.g., “It will rain, or it will not rain”) or employ circular reasoning (e.g., “she is untrustworthy because she can’t be trusted”).

You may have seen both “appendices” or “appendixes” as pluralizations of “ appendix .” Either spelling can be used, but “appendices” is more common (including in APA Style ). Consistency is key here: make sure you use the same spelling throughout your paper.

The purpose of a lab report is to demonstrate your understanding of the scientific method with a hands-on lab experiment. Course instructors will often provide you with an experimental design and procedure. Your task is to write up how you actually performed the experiment and evaluate the outcome.

In contrast, a research paper requires you to independently develop an original argument. It involves more in-depth research and interpretation of sources and data.

A lab report is usually shorter than a research paper.

The sections of a lab report can vary between scientific fields and course requirements, but it usually contains the following:

- Title: expresses the topic of your study

- Abstract: summarizes your research aims, methods, results, and conclusions

- Introduction: establishes the context needed to understand the topic

- Method: describes the materials and procedures used in the experiment

- Results: reports all descriptive and inferential statistical analyses

- Discussion: interprets and evaluates results and identifies limitations

- Conclusion: sums up the main findings of your experiment

- References: list of all sources cited using a specific style (e.g. APA)

- Appendices: contains lengthy materials, procedures, tables or figures

A lab report conveys the aim, methods, results, and conclusions of a scientific experiment . Lab reports are commonly assigned in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields.

The abstract is the very last thing you write. You should only write it after your research is complete, so that you can accurately summarize the entirety of your thesis , dissertation or research paper .

If you’ve gone over the word limit set for your assignment, shorten your sentences and cut repetition and redundancy during the editing process. If you use a lot of long quotes , consider shortening them to just the essentials.

If you need to remove a lot of words, you may have to cut certain passages. Remember that everything in the text should be there to support your argument; look for any information that’s not essential to your point and remove it.

To make this process easier and faster, you can use a paraphrasing tool . With this tool, you can rewrite your text to make it simpler and shorter. If that’s not enough, you can copy-paste your paraphrased text into the summarizer . This tool will distill your text to its core message.

Revising, proofreading, and editing are different stages of the writing process .

- Revising is making structural and logical changes to your text—reformulating arguments and reordering information.

- Editing refers to making more local changes to things like sentence structure and phrasing to make sure your meaning is conveyed clearly and concisely.

- Proofreading involves looking at the text closely, line by line, to spot any typos and issues with consistency and correct them.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

Avoid citing sources in your abstract . There are two reasons for this:

- The abstract should focus on your original research, not on the work of others.

- The abstract should be self-contained and fully understandable without reference to other sources.

There are some circumstances where you might need to mention other sources in an abstract: for example, if your research responds directly to another study or focuses on the work of a single theorist. In general, though, don’t include citations unless absolutely necessary.

An abstract is a concise summary of an academic text (such as a journal article or dissertation ). It serves two main purposes:

- To help potential readers determine the relevance of your paper for their own research.

- To communicate your key findings to those who don’t have time to read the whole paper.

Abstracts are often indexed along with keywords on academic databases, so they make your work more easily findable. Since the abstract is the first thing any reader sees, it’s important that it clearly and accurately summarizes the contents of your paper.

In a scientific paper, the methodology always comes after the introduction and before the results , discussion and conclusion . The same basic structure also applies to a thesis, dissertation , or research proposal .

Depending on the length and type of document, you might also include a literature review or theoretical framework before the methodology.

Whether you’re publishing a blog, submitting a research paper , or even just writing an important email, there are a few techniques you can use to make sure it’s error-free:

- Take a break : Set your work aside for at least a few hours so that you can look at it with fresh eyes.

- Proofread a printout : Staring at a screen for too long can cause fatigue – sit down with a pen and paper to check the final version.

- Use digital shortcuts : Take note of any recurring mistakes (for example, misspelling a particular word, switching between US and UK English , or inconsistently capitalizing a term), and use Find and Replace to fix it throughout the document.

If you want to be confident that an important text is error-free, it might be worth choosing a professional proofreading service instead.

Editing and proofreading are different steps in the process of revising a text.

Editing comes first, and can involve major changes to content, structure and language. The first stages of editing are often done by authors themselves, while a professional editor makes the final improvements to grammar and style (for example, by improving sentence structure and word choice ).

Proofreading is the final stage of checking a text before it is published or shared. It focuses on correcting minor errors and inconsistencies (for example, in punctuation and capitalization ). Proofreaders often also check for formatting issues, especially in print publishing.

The cost of proofreading depends on the type and length of text, the turnaround time, and the level of services required. Most proofreading companies charge per word or page, while freelancers sometimes charge an hourly rate.

For proofreading alone, which involves only basic corrections of typos and formatting mistakes, you might pay as little as $0.01 per word, but in many cases, your text will also require some level of editing , which costs slightly more.

It’s often possible to purchase combined proofreading and editing services and calculate the price in advance based on your requirements.

There are many different routes to becoming a professional proofreader or editor. The necessary qualifications depend on the field – to be an academic or scientific proofreader, for example, you will need at least a university degree in a relevant subject.

For most proofreading jobs, experience and demonstrated skills are more important than specific qualifications. Often your skills will be tested as part of the application process.

To learn practical proofreading skills, you can choose to take a course with a professional organization such as the Society for Editors and Proofreaders . Alternatively, you can apply to companies that offer specialized on-the-job training programmes, such as the Scribbr Academy .

Ask our team

Want to contact us directly? No problem. We are always here for you.

- Email [email protected]

- Start live chat

- Call +1 (510) 822-8066

- WhatsApp +31 20 261 6040

Our team helps students graduate by offering:

- A world-class citation generator

- Plagiarism Checker software powered by Turnitin

- Innovative Citation Checker software

- Professional proofreading services

- Over 300 helpful articles about academic writing, citing sources, plagiarism, and more

Scribbr specializes in editing study-related documents . We proofread:

- PhD dissertations

- Research proposals

- Personal statements

- Admission essays

- Motivation letters

- Reflection papers

- Journal articles

- Capstone projects

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker is powered by elements of Turnitin’s Similarity Checker , namely the plagiarism detection software and the Internet Archive and Premium Scholarly Publications content databases .

The add-on AI detector is powered by Scribbr’s proprietary software.

The Scribbr Citation Generator is developed using the open-source Citation Style Language (CSL) project and Frank Bennett’s citeproc-js . It’s the same technology used by dozens of other popular citation tools, including Mendeley and Zotero.

You can find all the citation styles and locales used in the Scribbr Citation Generator in our publicly accessible repository on Github .

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Grad Med Educ

- v.8(3); 2016 Jul

The Literature Review: A Foundation for High-Quality Medical Education Research

a These are subscription resources. Researchers should check with their librarian to determine their access rights.

Despite a surge in published scholarship in medical education 1 and rapid growth in journals that publish educational research, manuscript acceptance rates continue to fall. 2 Failure to conduct a thorough, accurate, and up-to-date literature review identifying an important problem and placing the study in context is consistently identified as one of the top reasons for rejection. 3 , 4 The purpose of this editorial is to provide a road map and practical recommendations for planning a literature review. By understanding the goals of a literature review and following a few basic processes, authors can enhance both the quality of their educational research and the likelihood of publication in the Journal of Graduate Medical Education ( JGME ) and in other journals.

The Literature Review Defined

In medical education, no organization has articulated a formal definition of a literature review for a research paper; thus, a literature review can take a number of forms. Depending on the type of article, target journal, and specific topic, these forms will vary in methodology, rigor, and depth. Several organizations have published guidelines for conducting an intensive literature search intended for formal systematic reviews, both broadly (eg, PRISMA) 5 and within medical education, 6 and there are excellent commentaries to guide authors of systematic reviews. 7 , 8

- A literature review forms the basis for high-quality medical education research and helps maximize relevance, originality, generalizability, and impact.

- A literature review provides context, informs methodology, maximizes innovation, avoids duplicative research, and ensures that professional standards are met.

- Literature reviews take time, are iterative, and should continue throughout the research process.

- Researchers should maximize the use of human resources (librarians, colleagues), search tools (databases/search engines), and existing literature (related articles).

- Keeping organized is critical.

Such work is outside the scope of this article, which focuses on literature reviews to inform reports of original medical education research. We define such a literature review as a synthetic review and summary of what is known and unknown regarding the topic of a scholarly body of work, including the current work's place within the existing knowledge . While this type of literature review may not require the intensive search processes mandated by systematic reviews, it merits a thoughtful and rigorous approach.

Purpose and Importance of the Literature Review

An understanding of the current literature is critical for all phases of a research study. Lingard 9 recently invoked the “journal-as-conversation” metaphor as a way of understanding how one's research fits into the larger medical education conversation. As she described it: “Imagine yourself joining a conversation at a social event. After you hang about eavesdropping to get the drift of what's being said (the conversational equivalent of the literature review), you join the conversation with a contribution that signals your shared interest in the topic, your knowledge of what's already been said, and your intention.” 9

The literature review helps any researcher “join the conversation” by providing context, informing methodology, identifying innovation, minimizing duplicative research, and ensuring that professional standards are met. Understanding the current literature also promotes scholarship, as proposed by Boyer, 10 by contributing to 5 of the 6 standards by which scholarly work should be evaluated. 11 Specifically, the review helps the researcher (1) articulate clear goals, (2) show evidence of adequate preparation, (3) select appropriate methods, (4) communicate relevant results, and (5) engage in reflective critique.

Failure to conduct a high-quality literature review is associated with several problems identified in the medical education literature, including studies that are repetitive, not grounded in theory, methodologically weak, and fail to expand knowledge beyond a single setting. 12 Indeed, medical education scholars complain that many studies repeat work already published and contribute little new knowledge—a likely cause of which is failure to conduct a proper literature review. 3 , 4

Likewise, studies that lack theoretical grounding or a conceptual framework make study design and interpretation difficult. 13 When theory is used in medical education studies, it is often invoked at a superficial level. As Norman 14 noted, when theory is used appropriately, it helps articulate variables that might be linked together and why, and it allows the researcher to make hypotheses and define a study's context and scope. Ultimately, a proper literature review is a first critical step toward identifying relevant conceptual frameworks.

Another problem is that many medical education studies are methodologically weak. 12 Good research requires trained investigators who can articulate relevant research questions, operationally define variables of interest, and choose the best method for specific research questions. Conducting a proper literature review helps both novice and experienced researchers select rigorous research methodologies.

Finally, many studies in medical education are “one-offs,” that is, single studies undertaken because the opportunity presented itself locally. Such studies frequently are not oriented toward progressive knowledge building and generalization to other settings. A firm grasp of the literature can encourage a programmatic approach to research.

Approaching the Literature Review

Considering these issues, journals have a responsibility to demand from authors a thoughtful synthesis of their study's position within the field, and it is the authors' responsibility to provide such a synthesis, based on a literature review. The aforementioned purposes of the literature review mandate that the review occurs throughout all phases of a study, from conception and design, to implementation and analysis, to manuscript preparation and submission.

Planning the literature review requires understanding of journal requirements, which vary greatly by journal ( table 1 ). Authors are advised to take note of common problems with reporting results of the literature review. Table 2 lists the most common problems that we have encountered as authors, reviewers, and editors.

Sample of Journals' Author Instructions for Literature Reviews Conducted as Part of Original Research Article a

Common Problem Areas for Reporting Literature Reviews in the Context of Scholarly Articles

Locating and Organizing the Literature

Three resources may facilitate identifying relevant literature: human resources, search tools, and related literature. As the process requires time, it is important to begin searching for literature early in the process (ie, the study design phase). Identifying and understanding relevant studies will increase the likelihood of designing a relevant, adaptable, generalizable, and novel study that is based on educational or learning theory and can maximize impact.

Human Resources

A medical librarian can help translate research interests into an effective search strategy, familiarize researchers with available information resources, provide information on organizing information, and introduce strategies for keeping current with emerging research. Often, librarians are also aware of research across their institutions and may be able to connect researchers with similar interests. Reaching out to colleagues for suggestions may help researchers quickly locate resources that would not otherwise be on their radar.

During this process, researchers will likely identify other researchers writing on aspects of their topic. Researchers should consider searching for the publications of these relevant researchers (see table 3 for search strategies). Additionally, institutional websites may include curriculum vitae of such relevant faculty with access to their entire publication record, including difficult to locate publications, such as book chapters, dissertations, and technical reports.

Strategies for Finding Related Researcher Publications in Databases and Search Engines

Search Tools and Related Literature

Researchers will locate the majority of needed information using databases and search engines. Excellent resources are available to guide researchers in the mechanics of literature searches. 15 , 16

Because medical education research draws on a variety of disciplines, researchers should include search tools with coverage beyond medicine (eg, psychology, nursing, education, and anthropology) and that cover several publication types, such as reports, standards, conference abstracts, and book chapters (see the box for several information resources). Many search tools include options for viewing citations of selected articles. Examining cited references provides additional articles for review and a sense of the influence of the selected article on its field.

Box Information Resources

- Web of Science a

- Education Resource Information Center (ERIC)

- Cumulative Index of Nursing & Allied Health (CINAHL) a

- Google Scholar

Once relevant articles are located, it is useful to mine those articles for additional citations. One strategy is to examine references of key articles, especially review articles, for relevant citations.

Getting Organized

As the aforementioned resources will likely provide a tremendous amount of information, organization is crucial. Researchers should determine which details are most important to their study (eg, participants, setting, methods, and outcomes) and generate a strategy for keeping those details organized and accessible. Increasingly, researchers utilize digital tools, such as Evernote, to capture such information, which enables accessibility across digital workspaces and search capabilities. Use of citation managers can also be helpful as they store citations and, in some cases, can generate bibliographies ( table 4 ).

Citation Managers

Knowing When to Say When

Researchers often ask how to know when they have located enough citations. Unfortunately, there is no magic or ideal number of citations to collect. One strategy for checking coverage of the literature is to inspect references of relevant articles. As researchers review references they will start noticing a repetition of the same articles with few new articles appearing. This can indicate that the researcher has covered the literature base on a particular topic.

Putting It All Together

In preparing to write a research paper, it is important to consider which citations to include and how they will inform the introduction and discussion sections. The “Instructions to Authors” for the targeted journal will often provide guidance on structuring the literature review (or introduction) and the number of total citations permitted for each article category. Reviewing articles of similar type published in the targeted journal can also provide guidance regarding structure and average lengths of the introduction and discussion sections.

When selecting references for the introduction consider those that illustrate core background theoretical and methodological concepts, as well as recent relevant studies. The introduction should be brief and present references not as a laundry list or narrative of available literature, but rather as a synthesized summary to provide context for the current study and to identify the gap in the literature that the study intends to fill. For the discussion, citations should be thoughtfully selected to compare and contrast the present study's findings with the current literature and to indicate how the present study moves the field forward.

To facilitate writing a literature review, journals are increasingly providing helpful features to guide authors. For example, the resources available through JGME include several articles on writing. 17 The journal Perspectives on Medical Education recently launched “The Writer's Craft,” which is intended to help medical educators improve their writing. Additionally, many institutions have writing centers that provide web-based materials on writing a literature review, and some even have writing coaches.

The literature review is a vital part of medical education research and should occur throughout the research process to help researchers design a strong study and effectively communicate study results and importance. To achieve these goals, researchers are advised to plan and execute the literature review carefully. The guidance in this editorial provides considerations and recommendations that may improve the quality of literature reviews.

How to Write a Literature Review

As every student knows, writing informative essay and research papers is an integral part of the educational program. You create a thesis, support it using valid sources, and formulate systematic ideas surrounding it. However, not all students know that they will also have to face another type of paper known as a Literature Review in college. Let's take a closer look at this with our custom essay writer .

Literature Review Definition

As this is a less common academic writing type, students often ask: "What is a literature review?" According to the definition, a literature review is a body of work that explores various publications within a specific subject area and sometimes within a set timeframe.

This type of writing requires you to read and analyze various sources that relate to the main subject and present each unique comprehension of the publications. Lastly, a literature review should combine a summary with a synthesis of the documents used. A summary is a brief overview of the important information in the publication; a synthesis is a re-organization of the information that gives the writing a new and unique meaning.

Typically, a literature review is a part of a larger paper, such as a thesis or dissertation. However, you may also be given it as a stand-alone assignment.

The Purpose

The main purpose of a literature review is to summarize and synthesize the ideas created by previous authors without implementing personal opinions or other additional information.

However, a literature review objective is not just to list summaries of sources; rather, it is to notice a central trend or principle in all of the publications. Just like a research paper has a thesis that guides it on rails, a literature review has the main organizing principle (MOP). The goal of this type of academic writing is to identify the MOP and show how it exists in all of your supporting documents.

Why is a literature review important? The value of such work is explained by the following goals it pursues:

- Highlights the significance of the main topic within a specific subject area.

- Demonstrates and explains the background of research for a particular subject matter.

- Helps to find out the key themes, principles, concepts, and researchers that exist within a topic.

- Helps to reveal relationships between existing ideas/studies on a topic.

- Reveals the main points of controversy and gaps within a topic.

- Suggests questions to drive primary research based on previous studies.

Here are some example topics for writing literature reviews:

- Exploring racism in "To Kill a Mockingbird," "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn," and "Uncle Tom's Cabin."

- Isolationism in "The Catcher in the Rye," "Frankenstein," and "1984"

- Understanding Moral Dilemmas in "Crime and Punishment," "The Scarlet Letter," and "The Lifeboat"

- Corruption of Power in "Macbeth," "All the King's Men," and "Animal Farm"

- Emotional and Physical survival in "Lord of the Flies," "Hatchet," and "Congo."

How Long Is a Literature Review?

When facing the need to write a literature review, students tend to wonder, "how long should a literature review be?" In some cases, the length of your paper's body may be determined by your instructor. Be sure to read the guidelines carefully to learn what is expected from you.

Keeping your literature review around 15-30% of your entire paper is recommended if you haven't been provided with specific guidelines. To give you a rough idea, that is about 2-3 pages for a 15-page paper. In case you are writing a literature review as a stand-alone assignment, its length should be specified in the instructions provided.

Literature Review Format: APA, MLA, and Chicago

The essay format you use should adhere to the citation style preferred by your instructor. Seek clarification from your instructor for several other components as well to establish a desired literature review format:

- How many sources should you review, and what kind of sources should they be (published materials, journal articles, or websites)?

- What format should you use to cite the sources?

- How long should the review be?

- Should your review consist of a summary, synthesis, or a personal critique?

- Should your review include subheadings or background information for your sources?

If you want to format your paper in APA style, then follow these rules:

- Use 1-inch page margins.

- Unless provided with other instructions, use double-spacing throughout the whole text.

- Make sure you choose a readable font. The preferred font for APA papers is Times New Roman set to 12-point size.

- Include a header at the top of every page (in capital letters). The page header must be a shortened version of your essay title and limited to 50 characters, including spacing and punctuation.

- Put page numbers in the upper right corner of every page.

- When shaping your literature review outline in APA, don't forget to include a title page. This page should include the paper's name, the author's name, and the institutional affiliation. Your title must be typed with upper and lowercase letters and centered in the upper part of the page; use no more than 12 words, and avoid using abbreviations and useless words.

For MLA style text, apply the following guidelines:

- Double your spacing across the entire paper.

- Set ½-inch indents for each new paragraph.

- The preferred font for MLA papers is Times New Roman set to 12-point size.

- Include a header at the top of your paper's first page or on the title page (note that MLA style does not require you to have a title page, but you are allowed to decide to include one). A header in this format should include your full name; the name of your instructor; the name of the class, course, or section number; and the due date of the assignment.

- Include a running head in the top right corner of each page in your paper. Place it one inch from the page's right margin and half an inch from the top margin. Only include your last name and the page number separated by a space in the running head. Do not put the abbreviation p. before page numbers.

Finally, if you are required to write a literature review in Chicago style, here are the key rules to follow:

- Set page margins to no less than 1 inch.

- Use double spacing across the entire text, except when it comes to table titles, figure captions, notes, blockquotes, and entries within the bibliography or References.

- Do not put spaces between paragraphs.

- Make sure you choose a clear and easily-readable font. The preferred fonts for Chicago papers are Times New Roman and Courier, set to no less than 10-point size, but preferably to 12-point size.

- A cover (title) page should include your full name, class information, and the date. Center the cover page and place it one-third below the top of the page.

- Place page numbers in the upper right corner of each page, including the cover page.

Read also about harvard format - popular style used in papers.

Structure of a Literature Review

How to structure a literature review: Like many other types of academic writing, a literature review follows a typical intro-body-conclusion style with 5 paragraphs overall. Now, let’s look at each component of the basic literature review structure in detail:

- Introduction

You should direct your reader(s) towards the MOP (main organizing principle). This means that your information must start from a broad perspective and gradually narrow down until it reaches your focal point.

Start by presenting your general concept (Corruption, for example). After the initial presentation, narrow your introduction's focus towards the MOP by mentioning the criteria you used to select the literature sources you have chosen (Macbeth, All the King's Men, and Animal Farm). Finally, the introduction will end with the presentation of your MOP that should directly link it to all three literature sources.

Body Paragraphs

Generally, each body paragraph will focus on a specific source of literature laid out in the essay's introduction. As each source has its own frame of reference for the MOP, it is crucial to structure the review in the most logically consistent way possible. This means the writing should be structured chronologically, thematically or methodologically.

Chronologically

Breaking down your sources based on their publication date is a solid way to keep a correct historical timeline. If applied properly, it can present the development of a certain concept over time and provide examples in the form of literature. However, sometimes there are better alternatives we can use to structure the body.

Thematically