- Linguistics

- Join Newsletter

Our Promise to you

Founded in 2002, our company has been a trusted resource for readers seeking informative and engaging content. Our dedication to quality remains unwavering—and will never change. We follow a strict editorial policy , ensuring that our content is authored by highly qualified professionals and edited by subject matter experts. This guarantees that everything we publish is objective, accurate, and trustworthy.

Over the years, we've refined our approach to cover a wide range of topics, providing readers with reliable and practical advice to enhance their knowledge and skills. That's why millions of readers turn to us each year. Join us in celebrating the joy of learning, guided by standards you can trust.

What Is the Critical Period Hypothesis?

The critical period hypothesis is a theory in the study of language acquisition which posits that there is a critical period of time in which the human mind can most easily acquire language. This idea is often considered with regard to primary language acquisition, and those who agree with this hypothesis argue that language must be learned in the first few years of life or else the ability to acquire language is greatly hindered. The critical period hypothesis is also used in secondary language acquisition, regarding the idea of a time period in which a secondary language can be most easily acquired.

With regard to primary language acquisition, which refers to the process by which a person learns his or her first language , the critical period hypothesis is quite dramatic. This idea indicates that a person has only a set period of time in which he or she can learn a first language, usually the first three to ten years of development. During this time, language can be learned and acquired through exposure to language; simply hearing others talking on an ongoing and regular basis is sufficient. Once this time period is over, however, those who agree with the critical period hypothesis argue that primary language acquisition may be impossible or greatly impaired.

There is a great deal of research into human brain development that supports this hypothesis, but it is still difficult to prove. One of the only conclusive ways to prove this hypothesis would be to have a person isolated from infancy until about the age of ten, without exposure to human speech. Such upbringing would be unthinkable, however, so this type of experiment cannot be conducted and the hypothesis remains largely unproven.

Unfortunate situations in which a child has been abused and isolated by his or her caregivers have provided opportunities to support the critical period hypothesis. In at least one instance, medical care and study of the child did demonstrate that full language acquisition was nearly impossible. Though this occurrence did support the hypothesis, secondary factors such as possible brain damage make the evidence flawed.

The critical period hypothesis is also frequently applied to secondary language acquisition, though in a somewhat less dramatic way. With regard to secondary language, many linguists and speech therapists agree that a second language can be acquired more easily when someone is young. Studies of the brain indicate that in youth the brain is still developing more quickly and new linguistic information can be processed and incorporated into the brain more easily. Once this period is over, however, secondary language acquisition is still certainly possible, though it can be more difficult.

- https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/transcripts/2112gchild.html

Editors' Picks

Related Articles

- What Is Language Acquisition?

- What Is a Second Language?

- What Are the Different Types of Second Language Acquisition Theories?

Our latest articles, guides, and more, delivered daily.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

The Critical Period Hypothesis in Second Language Acquisition: A Statistical Critique and a Reanalysis

Jan vanhove.

Department of Multilingualism, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland

Analyzed the data: JV. Wrote the paper: JV.

Associated Data

In second language acquisition research, the critical period hypothesis ( cph ) holds that the function between learners' age and their susceptibility to second language input is non-linear. This paper revisits the indistinctness found in the literature with regard to this hypothesis's scope and predictions. Even when its scope is clearly delineated and its predictions are spelt out, however, empirical studies–with few exceptions–use analytical (statistical) tools that are irrelevant with respect to the predictions made. This paper discusses statistical fallacies common in cph research and illustrates an alternative analytical method (piecewise regression) by means of a reanalysis of two datasets from a 2010 paper purporting to have found cross-linguistic evidence in favour of the cph . This reanalysis reveals that the specific age patterns predicted by the cph are not cross-linguistically robust. Applying the principle of parsimony, it is concluded that age patterns in second language acquisition are not governed by a critical period. To conclude, this paper highlights the role of confirmation bias in the scientific enterprise and appeals to second language acquisition researchers to reanalyse their old datasets using the methods discussed in this paper. The data and R commands that were used for the reanalysis are provided as supplementary materials.

Introduction

In the long term and in immersion contexts, second-language (L2) learners starting acquisition early in life – and staying exposed to input and thus learning over several years or decades – undisputedly tend to outperform later learners. Apart from being misinterpreted as an argument in favour of early foreign language instruction, which takes place in wholly different circumstances, this general age effect is also sometimes taken as evidence for a so-called ‘critical period’ ( cp ) for second-language acquisition ( sla ). Derived from biology, the cp concept was famously introduced into the field of language acquisition by Penfield and Roberts in 1959 [1] and was refined by Lenneberg eight years later [2] . Lenneberg argued that language acquisition needed to take place between age two and puberty – a period which he believed to coincide with the lateralisation process of the brain. (More recent neurological research suggests that different time frames exist for the lateralisation process of different language functions. Most, however, close before puberty [3] .) However, Lenneberg mostly drew on findings pertaining to first language development in deaf children, feral children or children with serious cognitive impairments in order to back up his claims. For him, the critical period concept was concerned with the implicit “automatic acquisition” [2, p. 176] in immersion contexts and does not preclude the possibility of learning a foreign language after puberty, albeit with much conscious effort and typically less success.

sla research adopted the critical period hypothesis ( cph ) and applied it to second and foreign language learning, resulting in a host of studies. In its most general version, the cph for sla states that the ‘susceptibility’ or ‘sensitivity’ to language input varies as a function of age, with adult L2 learners being less susceptible to input than child L2 learners. Importantly, the age–susceptibility function is hypothesised to be non-linear. Moving beyond this general version, we find that the cph is conceptualised in a multitude of ways [4] . This state of affairs requires scholars to make explicit their theoretical stance and assumptions [5] , but has the obvious downside that critical findings risk being mitigated as posing a problem to only one aspect of one particular conceptualisation of the cph , whereas other conceptualisations remain unscathed. This overall vagueness concerns two areas in particular, viz. the delineation of the cph 's scope and the formulation of testable predictions. Delineating the scope and formulating falsifiable predictions are, needless to say, fundamental stages in the scientific evaluation of any hypothesis or theory, but the lack of scholarly consensus on these points seems to be particularly pronounced in the case of the cph . This article therefore first presents a brief overview of differing views on these two stages. Then, once the scope of their cph version has been duly identified and empirical data have been collected using solid methods, it is essential that researchers analyse the data patterns soundly in order to assess the predictions made and that they draw justifiable conclusions from the results. As I will argue in great detail, however, the statistical analysis of data patterns as well as their interpretation in cph research – and this includes both critical and supportive studies and overviews – leaves a great deal to be desired. Reanalysing data from a recent cph -supportive study, I illustrate some common statistical fallacies in cph research and demonstrate how one particular cph prediction can be evaluated.

Delineating the scope of the critical period hypothesis

First, the age span for a putative critical period for language acquisition has been delimited in different ways in the literature [4] . Lenneberg's critical period stretched from two years of age to puberty (which he posits at about 14 years of age) [2] , whereas other scholars have drawn the cutoff point at 12, 15, 16 or 18 years of age [6] . Unlike Lenneberg, most researchers today do not define a starting age for the critical period for language learning. Some, however, consider the possibility of the critical period (or a critical period for a specific language area, e.g. phonology) ending much earlier than puberty (e.g. age 9 years [1] , or as early as 12 months in the case of phonology [7] ).

Second, some vagueness remains as to the setting that is relevant to the cph . Does the critical period constrain implicit learning processes only, i.e. only the untutored language acquisition in immersion contexts or does it also apply to (at least partly) instructed learning? Most researchers agree on the former [8] , but much research has included subjects who have had at least some instruction in the L2.

Third, there is no consensus on what the scope of the cp is as far as the areas of language that are concerned. Most researchers agree that a cp is most likely to constrain the acquisition of pronunciation and grammar and, consequently, these are the areas primarily looked into in studies on the cph [9] . Some researchers have also tried to define distinguishable cp s for the different language areas of phonetics, morphology and syntax and even for lexis (see [10] for an overview).

Fourth and last, research into the cph has focused on ‘ultimate attainment’ ( ua ) or the ‘final’ state of L2 proficiency rather than on the rate of learning. From research into the rate of acquisition (e.g. [11] – [13] ), it has become clear that the cph cannot hold for the rate variable. In fact, it has been observed that adult learners proceed faster than child learners at the beginning stages of L2 acquisition. Though theoretical reasons for excluding the rate can be posited (the initial faster rate of learning in adults may be the result of more conscious cognitive strategies rather than to less conscious implicit learning, for instance), rate of learning might from a different perspective also be considered an indicator of ‘susceptibility’ or ‘sensitivity’ to language input. Nevertheless, contemporary sla scholars generally seem to concur that ua and not rate of learning is the dependent variable of primary interest in cph research. These and further scope delineation problems relevant to cph research are discussed in more detail by, among others, Birdsong [9] , DeKeyser and Larson-Hall [14] , Long [10] and Muñoz and Singleton [6] .

Formulating testable hypotheses

Once the relevant cph 's scope has satisfactorily been identified, clear and testable predictions need to be drawn from it. At this stage, the lack of consensus on what the consequences or the actual observable outcome of a cp would have to look like becomes evident. As touched upon earlier, cph research is interested in the end state or ‘ultimate attainment’ ( ua ) in L2 acquisition because this “determines the upper limits of L2 attainment” [9, p. 10]. The range of possible ultimate attainment states thus helps researchers to explore the potential maximum outcome of L2 proficiency before and after the putative critical period.

One strong prediction made by some cph exponents holds that post- cp learners cannot reach native-like L2 competences. Identifying a single native-like post- cp L2 learner would then suffice to falsify all cph s making this prediction. Assessing this prediction is difficult, however, since it is not clear what exactly constitutes sufficient nativelikeness, as illustrated by the discussion on the actual nativelikeness of highly accomplished L2 speakers [15] , [16] . Indeed, there exists a real danger that, in a quest to vindicate the cph , scholars set the bar for L2 learners to match monolinguals increasingly higher – up to Swiftian extremes. Furthermore, the usefulness of comparing the linguistic performance in mono- and bilinguals has been called into question [6] , [17] , [18] . Put simply, the linguistic repertoires of mono- and bilinguals differ by definition and differences in the behavioural outcome will necessarily be found, if only one digs deep enough.

A second strong prediction made by cph proponents is that the function linking age of acquisition and ultimate attainment will not be linear throughout the whole lifespan. Before discussing how this function would have to look like in order for it to constitute cph -consistent evidence, I point out that the ultimate attainment variable can essentially be considered a cumulative measure dependent on the actual variable of interest in cph research, i.e. susceptibility to language input, as well as on such other factors like duration and intensity of learning (within and outside a putative cp ) and possibly a number of other influencing factors. To elaborate, the behavioural outcome, i.e. ultimate attainment, can be assumed to be integrative to the susceptibility function, as Newport [19] correctly points out. Other things being equal, ultimate attainment will therefore decrease as susceptibility decreases. However, decreasing ultimate attainment levels in and by themselves represent no compelling evidence in favour of a cph . The form of the integrative curve must therefore be predicted clearly from the susceptibility function. Additionally, the age of acquisition–ultimate attainment function can take just about any form when other things are not equal, e.g. duration of learning (Does learning last up until time of testing or only for a more or less constant number of years or is it dependent on age itself?) or intensity of learning (Do learners always learn at their maximum susceptibility level or does this intensity vary as a function of age, duration, present attainment and motivation?). The integral of the susceptibility function could therefore be of virtually unlimited complexity and its parameters could be adjusted to fit any age of acquisition–ultimate attainment pattern. It seems therefore astonishing that the distinction between level of sensitivity to language input and level of ultimate attainment is rarely made in the literature. Implicitly or explicitly [20] , the two are more or less equated and the same mathematical functions are expected to describe the two variables if observed across a range of starting ages of acquisition.

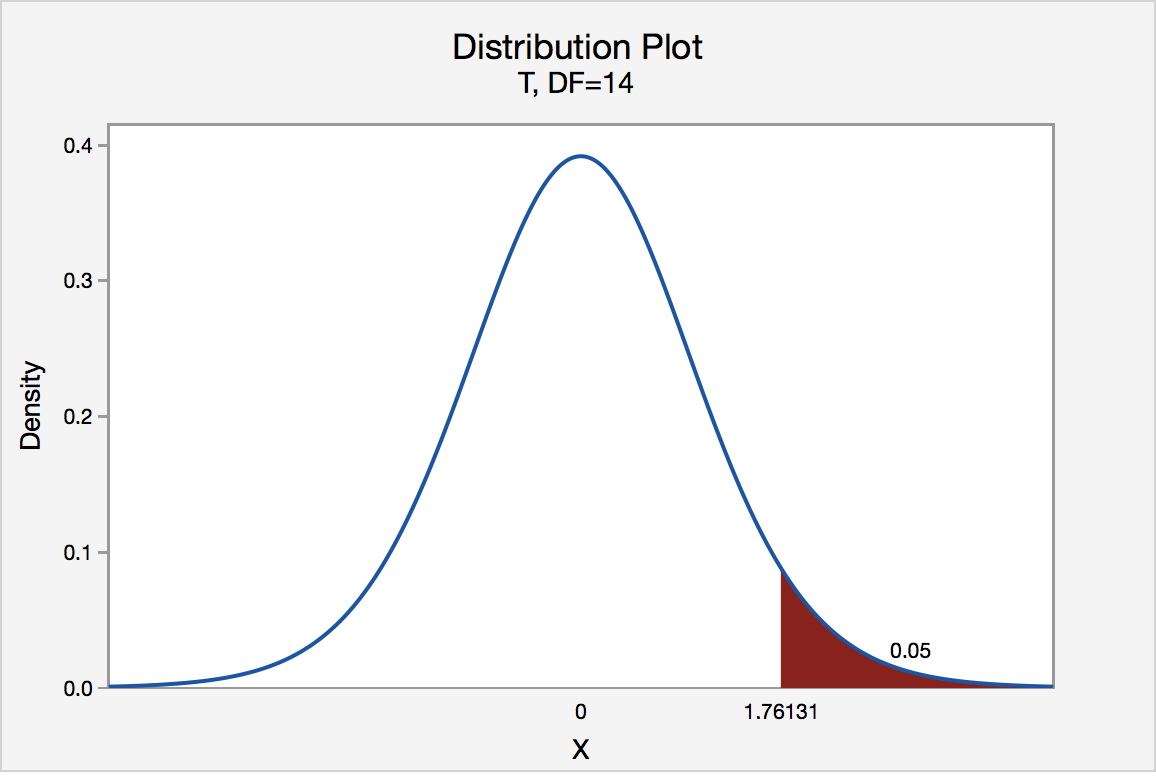

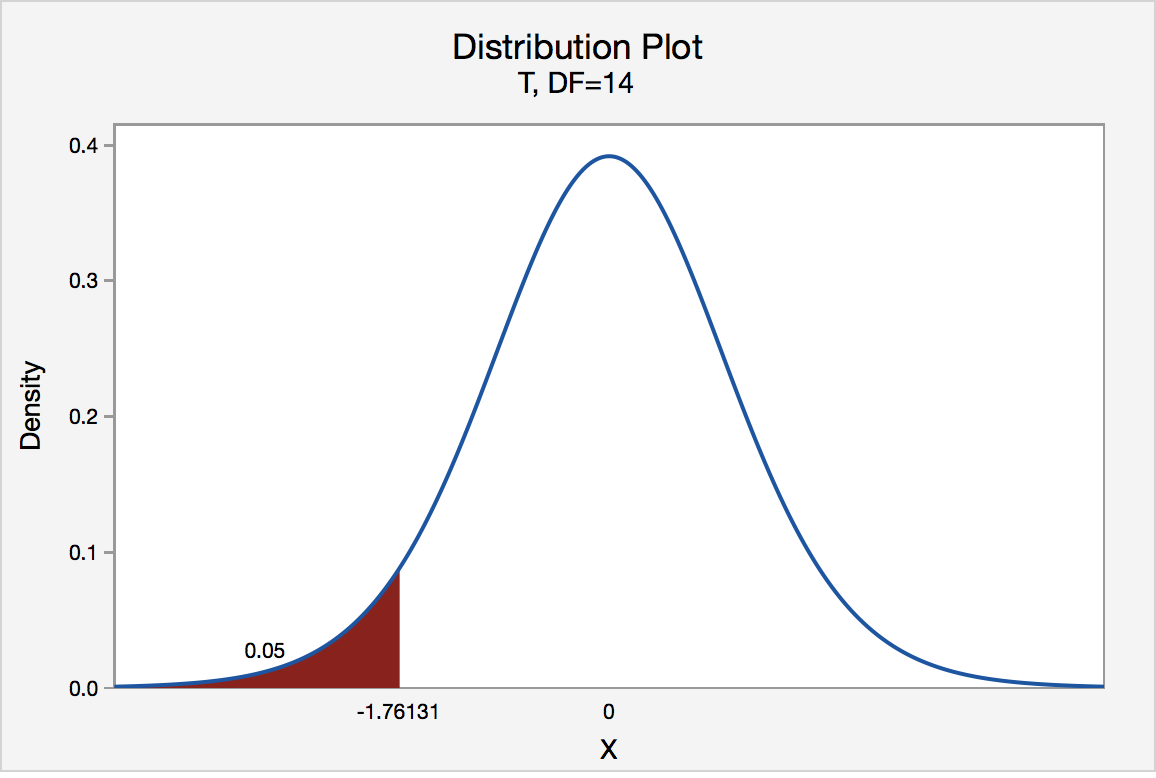

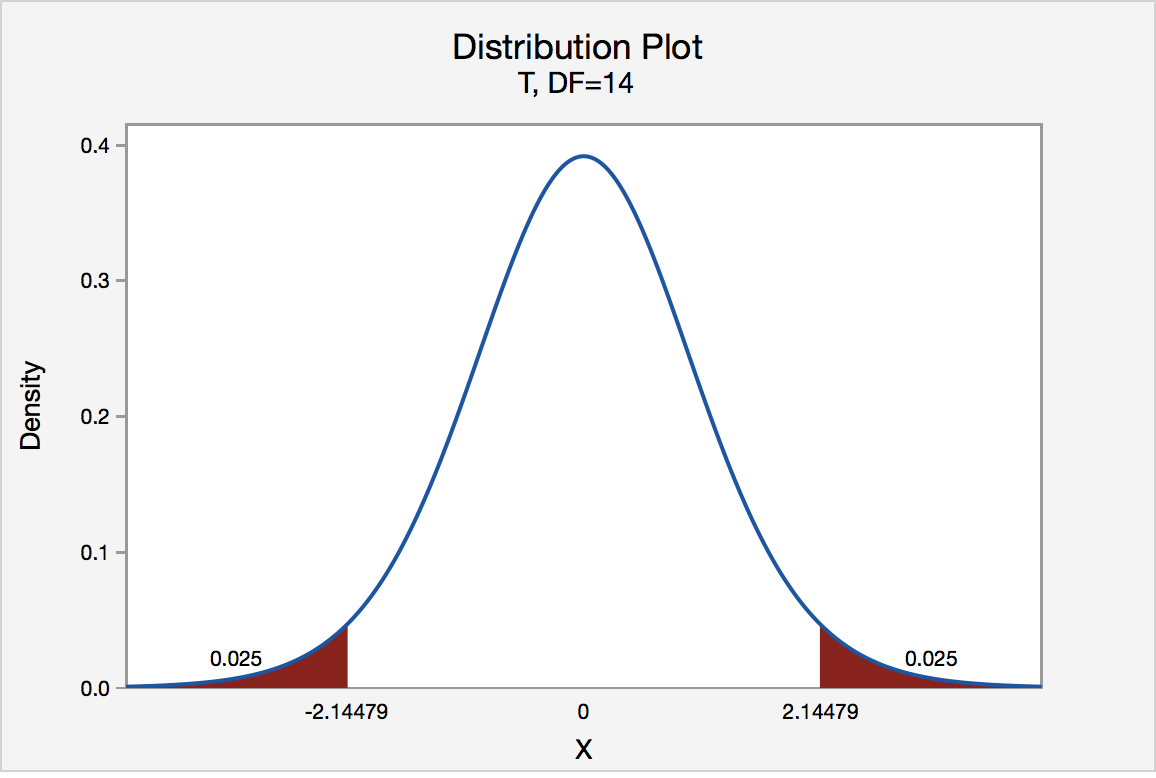

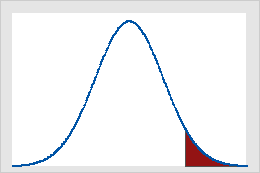

But even when the susceptibility and ultimate attainment variables are equated, there remains controversy as to what function linking age of onset of acquisition and ultimate attainment would actually constitute evidence for a critical period. Most scholars agree that not any kind of age effect constitutes such evidence. More specifically, the age of acquisition–ultimate attainment function would need to be different before and after the end of the cp [9] . According to Birdsong [9] , three basic possible patterns proposed in the literature meet this condition. These patterns are presented in Figure 1 . The first pattern describes a steep decline of the age of onset of acquisition ( aoa )–ultimate attainment ( ua ) function up to the end of the cp and a practically non-existent age effect thereafter. Pattern 2 is an “unconventional, although often implicitly invoked” [9, p. 17] notion of the cp function which contains a period of peak attainment (or performance at ceiling), i.e. performance does not vary as a function of age, which is often referred to as a ‘window of opportunity’. This time span is followed by an unbounded decline in ua depending on aoa . Pattern 3 includes characteristics of patterns 1 and 2. At the beginning of the aoa range, performance is at ceiling. The next segment is a downward slope in the age function which ends when performance reaches its floor. Birdsong points out that all of these patterns have been reported in the literature. On closer inspection, however, he concludes that the most convincing function describing these age effects is a simple linear one. Hakuta et al. [21] sketch further theoretically possible predictions of the cph in which the mean performance drops drastically and/or the slope of the aoa – ua proficiency function changes at a certain point.

The graphs are based on based on Figure 2 in [9] .

Although several patterns have been proposed in the literature, it bears pointing out that the most common explicit prediction corresponds to Birdsong's first pattern, as exemplified by the following crystal-clear statement by DeKeyser, one of the foremost cph proponents:

[A] strong negative correlation between age of acquisition and ultimate attainment throughout the lifespan (or even from birth through middle age), the only age effect documented in many earlier studies, is not evidence for a critical period…[T]he critical period concept implies a break in the AoA–proficiency function, i.e., an age (somewhat variable from individual to individual, of course, and therefore an age range in the aggregate) after which the decline of success rate in one or more areas of language is much less pronounced and/or clearly due to different reasons. [22, p. 445].

DeKeyser and before him among others Johnson and Newport [23] thus conceptualise only one possible pattern which would speak in favour of a critical period: a clear negative age effect before the end of the critical period and a much weaker (if any) negative correlation between age and ultimate attainment after it. This ‘flattened slope’ prediction has the virtue of being much more tangible than the ‘potential nativelikeness’ prediction: Testing it does not necessarily require comparing the L2-learners to a native control group and thus effectively comparing apples and oranges. Rather, L2-learners with different aoa s can be compared amongst themselves without the need to categorise them by means of a native-speaker yardstick, the validity of which is inevitably going to be controversial [15] . In what follows, I will concern myself solely with the ‘flattened slope’ prediction, arguing that, despite its clarity of formulation, cph research has generally used analytical methods that are irrelevant for the purposes of actually testing it.

Inferring non-linearities in critical period research: An overview

Group mean or proportion comparisons

[T]he main differences can be found between the native group and all other groups – including the earliest learner group – and between the adolescence group and all other groups. However, neither the difference between the two childhood groups nor the one between the two adulthood groups reached significance, which indicates that the major changes in eventual perceived nativelikeness of L2 learners can be associated with adolescence. [15, p. 270].

Similar group comparisons aimed at investigating the effect of aoa on ua have been carried out by both cph advocates and sceptics (among whom Bialystok and Miller [25, pp. 136–139], Birdsong and Molis [26, p. 240], Flege [27, pp. 120–121], Flege et al. [28, pp. 85–86], Johnson [29, p. 229], Johnson and Newport [23, p. 78], McDonald [30, pp. 408–410] and Patowski [31, pp. 456–458]). To be clear, not all of these authors drew direct conclusions about the aoa – ua function on the basis of these groups comparisons, but their group comparisons have been cited as indicative of a cph -consistent non-continuous age effect, as exemplified by the following quote by DeKeyser [22] :

Where group comparisons are made, younger learners always do significantly better than the older learners. The behavioral evidence, then, suggests a non-continuous age effect with a “bend” in the AoA–proficiency function somewhere between ages 12 and 16. [22, p. 448].

The first problem with group comparisons like these and drawing inferences on the basis thereof is that they require that a continuous variable, aoa , be split up into discrete bins. More often than not, the boundaries between these bins are drawn in an arbitrary fashion, but what is more troublesome is the loss of information and statistical power that such discretisation entails (see [32] for the extreme case of dichotomisation). If we want to find out more about the relationship between aoa and ua , why throw away most of the aoa information and effectively reduce the ua data to group means and the variance in those groups?

Comparison of correlation coefficients

Correlation-based inferences about slope discontinuities have similarly explicitly been made by cph advocates and skeptics alike, e.g. Bialystok and Miller [25, pp. 136 and 140], DeKeyser and colleagues [22] , [44] and Flege et al. [45, pp. 166 and 169]. Others did not explicitly infer the presence or absence of slope differences from the subset correlations they computed (among others Birdsong and Molis [26] , DeKeyser [8] , Flege et al. [28] and Johnson [29] ), but their studies nevertheless featured in overviews discussing discontinuities [14] , [22] . Indeed, the most recent overview draws a strong conclusion about the validity of the cph 's ‘flattened slope’ prediction on the basis of these subset correlations:

In those studies where the two groups are described separately, the correlation is much higher for the younger than for the older group, except in Birdsong and Molis (2001) [ = [26] , JV], where there was a ceiling effect for the younger group. This global picture from more than a dozen studies provides support for the non-continuity of the decline in the AoA–proficiency function, which all researchers agree is a hallmark of a critical period phenomenon. [22, p. 448].

In Johnson and Newport's specific case [23] , their correlation-based inference that ua levels off after puberty happened to be largely correct: the gjt scores are more or less randomly distributed around a near-horizontal trend line [26] . Ultimately, however, it rests on the fallacy of confusing correlation coefficients with slopes, which seriously calls into question conclusions such as DeKeyser's (cf. the quote above).

It can then straightforwardly be deduced that, other things equal, the aoa – ua correlation in the older group decreases as the ua variance in the older group increases relative to the ua variance in the younger group (Eq. 3).

Lower correlation coefficients in older aoa groups may therefore be largely due to differences in ua variance, which have been reported in several studies [23] , [26] , [28] , [29] (see [46] for additional references). Greater variability in ua with increasing age is likely due to factors other than age proper [47] , such as the concomitant greater variability in exposure to literacy, degree of education, motivation and opportunity for language use, and by itself represents evidence neither in favour of nor against the cph .

Regression approaches

Having demonstrated that neither group mean or proportion comparisons nor correlation coefficient comparisons can directly address the ‘flattened slope’ prediction, I now turn to the studies in which regression models were computed with aoa as a predictor variable and ua as the outcome variable. Once again, this category of studies is not mutually exclusive with the two categories discussed above.

In a large-scale study using self-reports and approximate aoa s derived from a sample of the 1990 U.S. Census, Stevens found that the probability with which immigrants from various countries stated that they spoke English ‘very well’ decreased curvilinearly as a function of aoa [48] . She noted that this development is similar to the pattern found by Johnson and Newport [23] but that it contains no indication of an “abruptly defined ‘critical’ or sensitive period in L2 learning” [48, p. 569]. However, she modelled the self-ratings using an ordinal logistic regression model in which the aoa variable was logarithmically transformed. Technically, this is perfectly fine, but one should be careful not to read too much into the non-linear curves found. In logistic models, the outcome variable itself is modelled linearly as a function of the predictor variables and is expressed in log-odds. In order to compute the corresponding probabilities, these log-odds are transformed using the logistic function. Consequently, even if the model is specified linearly, the predicted probabilities will not lie on a perfectly straight line when plotted as a function of any one continuous predictor variable. Similarly, when the predictor variable is first logarithmically transformed and then used to linearly predict an outcome variable, the function linking the predicted outcome variables and the untransformed predictor variable is necessarily non-linear. Thus, non-linearities follow naturally from Stevens's model specifications. Moreover, cph -consistent discontinuities in the aoa – ua function cannot be found using her model specifications as they did not contain any parameters allowing for this.

Using data similar to Stevens's, Bialystok and Hakuta found that the link between the self-rated English competences of Chinese- and Spanish-speaking immigrants and their aoa could be described by a straight line [49] . In contrast to Stevens, Bialystok and Hakuta used a regression-based method allowing for changes in the function's slope, viz. locally weighted scatterplot smoothing ( lowess ). Informally, lowess is a non-parametrical method that relies on an algorithm that fits the dependent variable for small parts of the range of the independent variable whilst guaranteeing that the overall curve does not contain sudden jumps (for technical details, see [50] ). Hakuta et al. used an even larger sample from the same 1990 U.S. Census data on Chinese- and Spanish-speaking immigrants (2.3 million observations) [21] . Fitting lowess curves, no discontinuities in the aoa – ua slope could be detected. Moreover, the authors found that piecewise linear regression models, i.e. regression models containing a parameter that allows a sudden drop in the curve or a change of its slope, did not provide a better fit to the data than did an ordinary regression model without such a parameter.

To sum up, I have argued at length that regression approaches are superior to group mean and correlation coefficient comparisons for the purposes of testing the ‘flattened slope’ prediction. Acknowledging the reservations vis-à-vis self-estimated ua s, we still find that while the relationship between aoa and ua is not necessarily perfectly linear in the studies discussed, the data do not lend unequivocal support to this prediction. In the following section, I will reanalyse data from a recent empirical paper on the cph by DeKeyser et al. [44] . The first goal of this reanalysis is to further illustrate some of the statistical fallacies encountered in cph studies. Second, by making the computer code available I hope to demonstrate how the relevant regression models, viz. piecewise regression models, can be fitted and how the aoa representing the optimal breakpoint can be identified. Lastly, the findings of this reanalysis will contribute to our understanding of how aoa affects ua as measured using a gjt .

Summary of DeKeyser et al. (2010)

I chose to reanalyse a recent empirical paper on the cph by DeKeyser et al. [44] (henceforth DK et al.). This paper lends itself well to a reanalysis since it exhibits two highly commendable qualities: the authors spell out their hypotheses lucidly and provide detailed numerical and graphical data descriptions. Moreover, the paper's lead author is very clear on what constitutes a necessary condition for accepting the cph : a non-linearity in the age of onset of acquisition ( aoa )–ultimate attainment ( ua ) function, with ua declining less strongly as a function of aoa in older, post- cp arrivals compared to younger arrivals [14] , [22] . Lastly, it claims to have found cross-linguistic evidence from two parallel studies backing the cph and should therefore be an unsuspected source to cph proponents.

The authors set out to test the following hypotheses:

- Hypothesis 1: For both the L2 English and the L2 Hebrew group, the slope of the age of arrival–ultimate attainment function will not be linear throughout the lifespan, but will instead show a marked flattening between adolescence and adulthood.

- Hypothesis 2: The relationship between aptitude and ultimate attainment will differ markedly for the young and older arrivals, with significance only for the latter. (DK et al., p. 417)

Both hypotheses were purportedly confirmed, which in the authors' view provides evidence in favour of cph . The problem with this conclusion, however, is that it is based on a comparison of correlation coefficients. As I have argued above, correlation coefficients are not to be confused with regression coefficients and cannot be used to directly address research hypotheses concerning slopes, such as Hypothesis 1. In what follows, I will reanalyse the relationship between DK et al.'s aoa and gjt data in order to address Hypothesis 1. Additionally, I will lay bare a problem with the way in which Hypothesis 2 was addressed. The extracted data and the computer code used for the reanalysis are provided as supplementary materials, allowing anyone interested to scrutinise and easily reproduce my whole analysis and carry out their own computations (see ‘supporting information’).

Data extraction

In order to verify whether we did in fact extract the data points to a satisfactory degree of accuracy, I computed summary statistics for the extracted aoa and gjt data and checked these against the descriptive statistics provided by DK et al. (pp. 421 and 427). These summary statistics for the extracted data are presented in Table 1 . In addition, I computed the correlation coefficients for the aoa – gjt relationship for the whole aoa range and for aoa -defined subgroups and checked these coefficients against those reported by DK et al. (pp. 423 and 428). The correlation coefficients computed using the extracted data are presented in Table 2 . Both checks strongly suggest the extracted data to be virtually identical to the original data, and Dr DeKeyser confirmed this to be the case in response to an earlier draft of the present paper (personal communication, 6 May 2013).

| Range | Mean | SD | ||

| North America | aoa | 5–71 | 32.54 | 18.01 |

| gjt | 104–198 | 150.76 | 27.32 | |

| Israel | aoa | 4–65 | 30.55 | 16.95 |

| gjt | 101–196 | 149.58 | 26.33 |

| Overall | Young | Middle | Old | |

| North America | −0.80 (76) | −069 (20) | −0.45 (26) | −0.27 (30) |

| Israel | −0.79 (62) | −0.46 (17) | −0.37 (32) | −0.54 (13) |

Results and Discussion

Modelling the link between age of onset of acquisition and ultimate attainment.

I first replotted the aoa and gjt data we extracted from DK et al.'s scatterplots and added non-parametric scatterplot smoothers in order to investigate whether any changes in slope in the aoa – gjt function could be revealed, as per Hypothesis 1. Figures 3 and and4 4 show this not to be the case. Indeed, simple linear regression models that model gjt as a function of aoa provide decent fits for both the North America and the Israel data, explaining 65% and 63% of the variance in gjt scores, respectively. The parameters of these models are given in Table 3 .

The trend line is a non-parametric scatterplot smoother. The scatterplot itself is a near-perfect replication of DK et al.'s Fig. 1.

The trend line is a non-parametric scatterplot smoother. The scatterplot itself is a near-perfect replication of DK et al.'s Fig. 5.

| Intercept ± SE | Slope ± SE | -test of model fit | ||

| North America | 168.50±2.42 | −1.22±0.10 | 0.65 | (1.74) = 135.3, <0.001 |

| Israel | 164.00±2.57 | −1.23±0.12 | 0.63 | (1.60) = 100.4, <0.001 |

To ensure that both segments are joined at the breakpoint, the predictor variable is first centred at the breakpoint value, i.e. the breakpoint value is subtracted from the original predictor variable values. For a blow-by-blow account of how such models can be fitted in r , I refer to an example analysis by Baayen [55, pp. 214–222].

Solid: regression with breakpoint at aoa 18 (dashed lines represent its 95% confidence interval); dot-dash: regression without breakpoint.

Solid: regression with breakpoint at aoa 18 (dashed lines represent its 95% confidence interval); dot-dash (hardly visible due to near-complete overlap): regression without breakpoint.

| Intercept ± SE | Slope ± SE (aoa ≤18) | Slope ± SE (aoa >18) | -test of model fit | ||

| North America | 164.24±3.35 | −2.40±0.66 | −1.07±0.13 | 0.66 | (2.73) = 71.4, <0.001 |

| Israel | 165.07±3.90 | −1.21±0.62 | −1.23±0.17 | 0.63 | (2.59) = 49.4, <0.001 |

Solid: regression with breakpoint at aoa 16 (dashed lines represent its 95% confidence interval); dot-dash: regression without breakpoint.

Solid: regression with breakpoint at aoa 6 (dashed lines represent its 95% confidence interval); dot-dash (hardly visible due to near-complete overlap): regression without breakpoint.

| Intercept ± SE | Slope ± SE | -test of model fit | |

| 170.94±2.56 | −1.22±0.10 | 0.65 | (1,74) = 135.3, <0.001 |

| Intercept ± SE | Slope ± SE (aoa ≤16) | Slope ± SE (aoa >16) | -test of model fit | |

| 166.69±3.27 | −2.86±082 | −1.08±0.12 | 0.67 | (2,73 = 72.5), <0.001 |

| Intercept ± SE | Slope ± SE | -test of model fit | |

| 179.75±3.65 | −1.23±0.12 | 0.63 | (1,60) = 100.4, <0 001 |

| Intercept ± SE | slope ± SE (aoa <6) | Slope ± SE (aoa >6) | -test of model fit | |

| 180.37±3.87 | 2.62±7.67 | −1.25±0.13 | 0.63 | (2,59) = 49.7, <0.001 |

In sum, a regression model that allows for changes in the slope of the the aoa – gjt function to account for putative critical period effects provides a somewhat better fit to the North American data than does an everyday simple regression model. The improvement in model fit is marginal, however, and including a breakpoint does not result in any detectable improvement of model fit to the Israel data whatsoever. Breakpoint models therefore fail to provide solid cross-linguistic support in favour of critical period effects: across both data sets, gjt can satisfactorily be modelled as a linear function of aoa .

On partialling out ‘age at testing’

As I have argued above, correlation coefficients cannot be used to test hypotheses about slopes. When the correct procedure is carried out on DK et al.'s data, no cross-linguistically robust evidence for changes in the aoa – gjt function was found. In addition to comparing the zero-order correlations between aoa and gjt , however, DK et al. computed partial correlations in which the variance in aoa associated with the participants' age at testing ( aat ; a potentially confounding variable) was filtered out. They found that these partial correlations between aoa and gjt , which are given in Table 9 , differed between age groups in that they are stronger for younger than for older participants. This, DK et al. argue, constitutes additional evidence in favour of the cph . At this point, I can no longer provide my own analysis of DK et al.'s data seeing as the pertinent data points were not plotted. Nevertheless, the detailed descriptions by DK et al. strongly suggest that the use of these partial correlations is highly problematic. Most importantly, and to reiterate, correlations (whether zero-order or partial ones) are actually of no use when testing hypotheses concerning slopes. Still, one may wonder why the partial correlations differ across age groups. My surmise is that these differences are at least partly the by-product of an imbalance in the sampling procedure.

| Overall | Young | Middle | Old | |

| North America | −0.29 (76) | −0.71 (20) | −0.17 (26) | −0.12 (30) |

| Israel | −0.28 (62) | −0.51 (17) | −0.12 (32) | −0.33 (13) |

The upshot of this brief discussion is that the partial correlation differences reported by DK et al. are at least partly the result of an imbalance in the sampling procedure: aoa and aat were simply less intimately tied for the young arrivals in the North America study than for the older arrivals with L2 English or for all of the L2 Hebrew participants. In an ideal world, we would like to fix aat or ascertain that it at most only weakly correlates with aoa . This, however, would result in a strong correlation between aoa and another potential confound variable, length of residence in the L2 environment, bringing us back to square one. Allowing for only moderate correlations between aoa and aat might improve our predicament somewhat, but even in that case, we should tread lightly when making inferences on the basis of statistical control procedures [61] .

On estimating the role of aptitude

Having shown that Hypothesis 1 could not be confirmed, I now turn to Hypothesis 2, which predicts a differential role of aptitude for ua in sla in different aoa groups. More specifically, it states that the correlation between aptitude and gjt performance will be significant only for older arrivals. The correlation coefficients of the relationship between aptitude and gjt are presented in Table 10 .

| Overall | Young | Middle | Old | |

| North America | 0.210 (76) | 0.11 (20) | 0.44 (26) | 0.33 (30) |

| Israel | 0.00 (62) | −0.37 (17) | 0.45 (32) | 0.14 (13) |

The problem with both the wording of Hypothesis 2 and the way in which it is addressed is the following: it is assumed that a variable has a reliably different effect in different groups when the effect reaches significance in one group but not in the other. This logic is fairly widespread within several scientific disciplines (see e.g. [62] for a discussion). Nonetheless, it is demonstrably fallacious [63] . Here we will illustrate the fallacy for the specific case of comparing two correlation coefficients.

Apart from not being replicated in the North America study, does this difference actually show anything? I contend that it does not: what is of interest are not so much the correlation coefficients, but rather the interactions between aoa and aptitude in models predicting gjt . These interactions could be investigated by fitting a multiple regression model in which the postulated cp breakpoint governs the slope of both aoa and aptitude. If such a model provided a substantially better fit to the data than a model without a breakpoint for the aptitude slope and if the aptitude slope changes in the expected direction (i.e. a steeper slope for post- cp than for younger arrivals) for different L1–L2 pairings, only then would this particular prediction of the cph be borne out.

Using data extracted from a paper reporting on two recent studies that purport to provide evidence in favour of the cph and that, according to its authors, represent a major improvement over earlier studies (DK et al., p. 417), it was found that neither of its two hypotheses were actually confirmed when using the proper statistical tools. As a matter of fact, the gjt scores continue to decline at essentially the same rate even beyond the end of the putative critical period. According to the paper's lead author, such a finding represents a serious problem to his conceptualisation of the cph [14] ). Moreover, although modelling a breakpoint representing the end of a cp at aoa 16 may improve the statistical model slightly in study on learners of English in North America, the study on learners of Hebrew in Israel fails to confirm this finding. In fact, even if we were to accept the optimal breakpoint computed for the Israel study, it lies at aoa 6 and is associated with a different geometrical pattern.

Diverging age trends in parallel studies with participants with different L2s have similarly been reported by Birdsong and Molis [26] and are at odds with an L2-independent cph . One parsimonious explanation of such conflicting age trends may be that the overall, cross-linguistic age trend is in fact linear, but that fluctuations in the data (due to factors unaccounted for or randomness) may sometimes give rise to a ‘stretched L’-shaped pattern ( Figure 1, left panel ) and sometimes to a ‘stretched 7’-shaped pattern ( Figure 1 , middle panel; see also [66] for a similar comment).

Importantly, the criticism that DeKeyser and Larsson-Hall levy against two studies reporting findings similar to the present [48] , [49] , viz. that the data consisted of self-ratings of questionable validity [14] , does not apply to the present data set. In addition, DK et al. did not exclude any outliers from their analyses, so I assume that DeKeyser and Larsson-Hall's criticism [14] of Birdsong and Molis's study [26] , i.e. that the findings were due to the influence of outliers, is not applicable to the present data either. For good measure, however, I refitted the regression models with and without breakpoints after excluding one potentially problematic data point per model. The following data points had absolute standardised residuals larger than 2.5 in the original models without breakpoints as well as in those with breakpoints: the participant with aoa 17 and a gjt score of 125 in the North America study and the participant with aoa 12 and a gjt score of 117 in the Israel study. The resultant models were virtually identical to the original models (see Script S1 ). Furthermore, the aoa variable was sufficiently fine-grained and the aoa – gjt curve was not ‘presmoothed’ by the prior aggregation of gjt across parts of the aoa range (see [51] for such a criticism of another study). Lastly, seven of the nine “problems with supposed counter-evidence” to the cph discussed by Long [5] do not apply either, viz. (1) “[c]onfusion of rate and ultimate attainment”, (2) “[i]nappropriate choice of subjects”, (3) “[m]easurement of AO”, (4) “[l]eading instructions to raters”, (6) “[u]se of markedly non-native samples making near-native samples more likely to sound native to raters”, (7) “[u]nreliable or invalid measures”, and (8) “[i]nappropriate L1–L2 pairings”. Problem No. 5 (“Assessments based on limited samples and/or “language-like” behavior”) may be apropos given that only gjt data were used, leaving open the theoretical possibility that other measures might have yielded a different outcome. Finally, problem No. 9 (“Faulty interpretation of statistical patterns”) is, of course, precisely what I have turned the spotlights on.

Conclusions

The critical period hypothesis remains a hotly contested issue in the psycholinguistics of second-language acquisition. Discussions about the impact of empirical findings on the tenability of the cph generally revolve around the reliability of the data gathered (e.g. [5] , [14] , [22] , [52] , [67] , [68] ) and such methodological critiques are of course highly desirable. Furthermore, the debate often centres on the question of exactly what version of the cph is being vindicated or debunked. These versions differ mainly in terms of its scope, specifically with regard to the relevant age span, setting and language area, and the testable predictions they make. But even when the cph 's scope is clearly demarcated and its main prediction is spelt out lucidly, the issue remains to what extent the empirical findings can actually be marshalled in support of the relevant cph version. As I have shown in this paper, empirical data have often been taken to support cph versions predicting that the relationship between age of acquisition and ultimate attainment is not strictly linear, even though the statistical tools most commonly used (notably group mean and correlation coefficient comparisons) were, crudely put, irrelevant to this prediction. Methods that are arguably valid, e.g. piecewise regression and scatterplot smoothing, have been used in some studies [21] , [26] , [49] , but these studies have been criticised on other grounds. To my knowledge, such methods have never been used by scholars who explicitly subscribe to the cph .

I suspect that what may be going on is a form of ‘confirmation bias’ [69] , a cognitive bias at play in diverse branches of human knowledge seeking: Findings judged to be consistent with one's own hypothesis are hardly questioned, whereas findings inconsistent with one's own hypothesis are scrutinised much more strongly and criticised on all sorts of points [70] – [73] . My reanalysis of DK et al.'s recent paper may be a case in point. cph exponents used correlation coefficients to address their prediction about the slope of a function, as had been done in a host of earlier studies. Finding a result that squared with their expectations, they did not question the technical validity of their results, or at least they did not report this. (In fact, my reanalysis is actually a case in point in two respects: for an earlier draft of this paper, I had computed the optimal position of the breakpoints incorrectly, resulting in an insignificant improvement of model fit for the North American data rather than a borderline significant one. Finding a result that squared with my expectations, I did not question the technical validity of my results – until this error was kindly pointed out to me by Martijn Wieling (University of Tübingen).) That said, I am keen to point out that the statistical analyses in this particular paper, though suboptimal, are, as far as I could gather, reported correctly, i.e. the confirmation bias does not seem to have resulted in the blatant misreportings found elsewhere (see [74] for empirical evidence and discussion). An additional point to these authors' credit is that, apart from explicitly identifying their cph version's scope and making crystal-clear predictions, they present data descriptions that actually permit quantitative reassessments and have a history of doing so (e.g. the appendix in [8] ). This leads me to believe that they analysed their data all in good conscience and to hope that they, too, will conclude that their own data do not, in fact, support their hypothesis.

I end this paper on an upbeat note. Even though I have argued that the analytical tools employed in cph research generally leave much to be desired, the original data are, so I hope, still available. This provides researchers, cph supporters and sceptics alike, with an exciting opportunity to reanalyse their data sets using the tools outlined in the present paper and publish their findings at minimal cost of time and resources (for instance, as a comment to this paper). I would therefore encourage scholars to engage their old data sets and to communicate their analyses openly, e.g. by voluntarily publishing their data and computer code alongside their articles or comments. Ideally, cph supporters and sceptics would join forces to agree on a protocol for a high-powered study in order to provide a truly convincing answer to a core issue in sla .

Supporting Information

aoa and gjt data extracted from DeKeyser et al.'s North America study.

aoa and gjt data extracted from DeKeyser et al.'s Israel study.

Script with annotated R code used for the reanalysis. All add-on packages used can be installed from within R.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Irmtraud Kaiser (University of Fribourg) for helping me to get an overview of the literature on the critical period hypothesis in second language acquisition. Thanks are also due to Martijn Wieling (currently University of Tübingen) for pointing out an error in the R code accompanying an earlier draft of this paper.

Funding Statement

No current external funding sources for this study.

Stack Exchange Network

Stack Exchange network consists of 183 Q&A communities including Stack Overflow , the largest, most trusted online community for developers to learn, share their knowledge, and build their careers.

Q&A for work

Connect and share knowledge within a single location that is structured and easy to search.

What are the main arguments for and against the critical period hypothesis, and what are alternative explanations?

Why is the critical period hypothesis so heavily disputed, yet widely accepted; what are its major strengths and weaknesses; what other explanations exist for the perceived "critical period", if it does not exist?

- critical-period

Let us start with a simple, relatively informal statement: “in most cases, those who start learning a language as children become ultimately become more proficient in a language than those who start learning it later”. This is uncontroversial, and something I think the vast majority of second-language acquisition researchers would agree on. However, this is not how the Critical Period Hypothesis (CPH) is understood within the field of Second Language Acquisition (SLA). CPH is a large subject, and your question is hard to answer in a few paragraphs. Therefore, I am reusing large fragments of an assignment I wrote on this very topic for an SLA course a few years ago. Let me know if something is unclear or the style is too terse at some points.

Summary (TL;DR)

There is no universally accepted definition of a critical period within linguistics and some of the controversies are caused by the fact that different researchers use different definitions.

There are a few key findings that are not controversial:

- early learners perform consistently well in all aspects of language use,

- as we move the starting age, they perform statistically worse and worse until puberty,

- however, the decrease in performance is not uniform.

An explanation, provided by Bialystok (1997) as an alternative to CPH, is the different learning style of children, compared to late learners.

Paradoxically, the differences (or lack thereof) between those who learn a foreign language as adults is the key factor in deciding whether CPH is true or not, and a controversial one:

- Some studies found correlations between the age adult learners started learning a language and their ultimate attainment. In other words, these studies suggest that if we compare people who have been learning a language for a very long time, the ultimate attainment of those who started at the age of 20 is statistically higher than the ultimate attainment of those who started at the age of 40. These studies argue that there is no CPH in the childhood, but rather that our abilities in learning a new language consistently decrease throughout our whole lives.

- Other studies found no clear correlations between the starting age and the ultimate attainment among adult language learners. They point out that the correlation between the starting age and ultimate attainment is clear for those who started before puberty. Based on that, they argue that there is something qualitatively different about starting to learn in an early age, and therefore conclude that it is an argument for CPH.

Definitions of the critical period used by those who argue against CPH

Controversies with the Critical Period Hypothesis (CPH) are related to the issue of ultimate attainment of early and late language learners, that is, the highest language proficiency level they can attain. The patterns in ultimate attainment may be explained by CPH, but they may also have different explanations. Some researchers support some form of the Critical Period Hypothesis (Johnson and Newport 1989, DeKeyser and Larson-Hall 2005, Patkowsky 1994, Scovel 1988), while others argue against it (Bialystok 1997).

A major problem with the Critical Period Hypothesis is that there appears to be no universally accepted definition of a critical period within linguistics . Bialystok (1997) bases her discussion of the critical/sensitive period (which she takes to be synonymous 1 ) on a specific technical definition used in ethology, which includes 14 essential structural characteristics that describe such a period (Bornstein 1989). She argues that one of these characteristics is especially problematic – the system: “structure or function altered in the sensitive period” (Bornstein 1989:184). In other words, she argues that there is no period where a structure in the brain is modified in a way that makes subsequent language learning harder or impossible. Bialystok does, however, agree that there is an optimal period for language learning – something that can be characterised by the statement “ On average, children are more successful than adults when faced with the task of learning a second language ” (Bialystok 1997:117). Despite the controversy around other issues, this fact is uncontested and has been verified by numerous studies .

Bialystok (1997) rejects the existence of a critical period, because of lack of postulated structure that is modified when the period is over. She postulates that an important factor that causes differences in ultimate attainment between early and late starters is learning style: children prefer accommodation (creating new concepts) over assimilation (extending existing concepts). The question remains: why do they prefer accommodation? She suggests that “[t]his may be because children are in the process of creating new categories all the time as they are learning new information” (Bialystok 1997:132).

Definitions of the critical period used by supporters of CPH

The researchers who support some form of the Critical Period Hypothesis (Johnson and Newport 1989, DeKeyser and Larson-Hall 2005), formulate it in a form that is much weaker than Bialystok's (1997) formulation. What they postulate often resembles what Bialystok calls the optimal age.

Johnson and Newport (1989) reformulated CPH into two alternative hypotheses, in order to fit second language acquisition into the picture:

The exercise hypothesis : “Early in life, humans have a superior capacity for acquiring languages. If the capacity is not exercised during this time, it will disappear or decline with maturation. If the capacity is exercised, however, further language learning abilities will remain intact throughout life.” (Johnson and Newport 1989:64)

The maturational state hypothesis : “Early in life, humans have a superior capacity for acquiring languages. This capacity disappears or declines with maturation.” (Johnson and Newport 1989:64)

We can see that if a critical period was found for second language acquisition, we could be almost sure that it exists for L1 acquisition as well (the maturational state hypothesis). However, we cannot deduce in this way in case of the exercise hypothesis – non-existence of a critical period for L2 acquisition does not exclude in any way a possibility of such period for the first language (Bialystok 1997).

DeKeyser and Larson-Hall (2005) formulate the hypothesis as: “language acquisition from mere exposure (i.e. implicit learning) […] is severely limited in older adolescents and adults”. Their formulation is quite vague, as is the constatation that there is a “qualitative change in language learning capacities somewhere between 4 and 18 years”.

There are also definitions that restrict the Critical Period Hypothesis to specific subareas of the language faculty. The most commonly mentioned area is phonology, see e.g. Patkowsky (1994, cited in Bialystok 1997), Scovel (1988, cited in Bialystok 1997).

Age effects before and after puberty

The current consensus is that early learners perform consistently well in all aspects of language use. As we move the starting age, they perform statistically worse and worse until puberty. The decrease in performance is not uniform, and in some areas (such as phonology) it is particularly visible. Performance on the same level as early bilinguals is possible, but rare.

Probably the most controversial aspect is the performance of adult learners. After puberty there is much bigger variance in the performance, so data are more prone to different interpretations. The results obtained by Derwing and Munro (2013) suggest that comprehensibility and good accent are negatively correlated with the age of arrival, that is, the age when English language immersion started. Johnson and Newport (1989) found no correlation of starting age after puberty with ultimate language proficiency, while Bialystok (1997) re-analysed these data and found some negative correlation. A meta-analysis by DeKeyser and Larson-Hall (2005) downplays the role of post-adolescent correlations. As we can see, the jury is still out on this debate.

1 In neuroscience critical period and sensitive period are two separate concepts, see Knudsen (2004).

Bibliography

- Bialystok, E. 1997. The structure of age: in search of barriers to second language acquisition. Second Language Research 13(2): 116-137.

- Bornstein, M.H. 1989. Sensitive periods in development: structural characteristics and causal interpretations. Psychological Bulletin 105,179–97.

- DeKeyser, R. and J. Larson-Hall. 2005. What does the critical period really mean? In J. F. Kroll and A. M. B. de Groot. 2005. Handbook of bilingualism: Psycholinguistic approaches . Cary, NC: Oxford University Press. Pp. 109–27.

- Derwing, T. M., & Munro, M. J. 2013. The development of L2 oral language skills in two L1 groups: A 7-year study. Language Learning 63, 163-185.

- Johnson, J.S., & Newport, E.L. 1989. Critical period effects in second language learning: The influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cognitive Psychology , 21, 60-99.

- Knudsen, E. I. 2004. Sensitive periods in the development of the brain and behavior. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience , 16, 1412-25

- Newport, E. L., & Supalla, T. 1987. A critical period effect in the acquisition of a primary language .

- Patkowsky, M. 1980. The sensitive period for the acquisition of syntax in a second language. Language Learning 30, 449–72

- Scovel, T. 1988. A time to speak: a psycholinguistic inquiry into the critical period for human speech . New York: Newbury House

Your Answer

Sign up or log in, post as a guest.

Required, but never shown

By clicking “Post Your Answer”, you agree to our terms of service and acknowledge you have read our privacy policy .

Not the answer you're looking for? Browse other questions tagged critical-period or ask your own question .

- Featured on Meta

- Bringing clarity to status tag usage on meta sites

- Announcing a change to the data-dump process

Hot Network Questions

- Fundamental Question on Noise Figure

- Plausible orbit to have a visible object slowly circle over the night sky

- Humans are forbidden from using complex computers. But what defines a complex computer?

- "With" as a function word to specify an additional circumstance or condition

- Power of Toffoli vs T in quantum logic

- Python function to expand regex with ranges

- What is the least number of colours Peter could use to color the 3x3 square?

- Multiplicity of the smallest non-zero Laplacian eigenvalue for tree graphs

- Is reading sheet music difficult?

- What is the missing fifth of the missing fifths?

- Visual assessment of scatterplots acceptable?

- Could a lawyer agree not to take any further cases against a company?

- Circuit that turns two LEDs off/on depending on switch

- Colossians 1:16 New World Translation renders τα πάντα as “all other things” but why is this is not shown in their Kingdom Interlinear?

- How can we know how good a TRNG is?

- How to make my latex code to be continuously showing my big table in the next pages

- Is there a way to read lawyers arguments in various trials?

- Size of the functor category

- Is there a way to prove ownership of church land?

- Question about word (relationship between language and thought)

- Do you believe something to be the truth or do you know the truth?

- Beatles reference in parody story from the 1980s

- What is the translation of this quote by Plato?

- Has anyone returned from space in a different vehicle from the one they went up in? And if so who was the first?

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Critical Periods

Introduction, general overviews.

- Critical Periods in Language: Background Readings

- First-Language Acquisition (L1A)

- Age and Second-Language Acquisition (L2A)

- Controversy around the Critical Period Hypothesis for Second-Language Acquisition (CPH/L2A)

- Critical Period Geometry and Timing in L2A

- Brain-Based Studies of Critical Periods in L2A

- Bilingualism

- First-Language Attrition

- Sign Language

- Foreign Language Education

- Animal Models of Critical Periods

- Absolute Pitch

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Acceptability Judgments

- Acquisition of Possessives

- Acquisition of Pragmatics

- Bilingualism and Multilingualism

- Biology of Language

- Children’s Acquisition of Syntactic Knowledge

- Early Child Phonology

- Experimental Linguistics

- Genetics and Language

- Language Acquisition

- Language in Autism Spectrum Disorders

- Language Nests

- Learnability

- Psycholinguistic Perspectives on Second Language Acquisition and Bilingualism

- Roman Jakobson

- The Prague Linguistic Circle

- Variationist Sociolinguistics

- Visual Word Recognition

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Attention and Salience

- Edward Sapir

- Text Comprehension

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Critical Periods by David P. Birdsong LAST REVIEWED: 12 January 2023 LAST MODIFIED: 12 January 2023 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199772810-0139

A critical period is a bounded maturational span during which experiential factors interact with biological mechanisms to determine neurocognitive and behavioral outcomes. In humans, the construct of critical period (CP) is commonly applied to first-language (L1) and second-language (L2) development. Some language researchers hold that during a CP, various mechanisms are at work that result in successful language acquisition and language processing. Outside of the period, other factors and mechanisms are involved, resulting in deficits in acquisition and processing. Many researchers believe that L1 development is constrained by maturationally based CPs. However, this notion is more controversial in L2 acquisition research, where the Critical Period Hypothesis for L2 acquisition (CPH/L2A) is debated on empirical, theoretical, and methodological grounds. Bilingualism researchers study the possibility that CPs may govern the likelihood and degree of loss (attrition) of the L1 among bilinguals as they age. Studies of CPs in L1 acquisition and L2 acquisition have been conducted with learners of spoken languages, signed languages, and artificial languages. CP research is considered in educational policy, particularly in the context of foreign language instruction. On a terminological note, a distinction is sometimes drawn between “critical” and “sensitive” periods, the latter term denoting receptivity of the organism to shaping by experience (or, in certain studies, suggesting relatively mild effects). Some researchers use these terms interchangeably, while others use one but not the other. Here, “critical period” will be used as a cover term unless specific reference is being made to sensitive period.

Lillard and Erisir 2011 describes juvenile CPs in language, imprinting, and vision. The article includes an informative table covering seven levels of neural changes in the brain in juveniles versus adults, with notes on the time course of changes and affected brain areas in animal and human models. The authors observe that changes in neural architecture triggered by early versus late experiences differ in degree more than type, and that the variety of triggering experiences is reduced with age. A second table summarizes neuroanatomical, electrophysiological, and neuroimaging techniques for observing specific types of neuroplasticity. Knudsen 2004 is exceptionally informative with respect to: prerequisites for CPs; the properties, mechanisms, and timing of plasticity; reopening of critical periods; the roles of presence and absence of relevant stimulation; and sensitive periods versus critical periods. Knudsen points out that complex behaviors (which include language use) may be regulated by multiple CPs. Takesian and Hensch 2013 emphasizes the individual-level plasticity of the timing of CP onset, peak, and offset, which may vary according to excitatory/inhibitory circuit balance that is sensitive to drugs, sleep, trauma, and genetic perturbation (see also Werker and Hensch 2015 [cited under First-Language Acquisition (L1A) ). Reh, et al. 2020 examines how plasticity is regulated at multiple timescales during development and provides examples from language processing, mental illness, and recovery from brain injury. Gabard-Durnam and McLaughlin 2020 outlines a set of current approaches to the study of sensitive periods in humans. These approaches include environmental manipulations (deprivation, enrichment, substitution), plasticity manipulations via pharmacological intervention, and computational modeling. Frankenhuis and Walasek 2020 develops an evolutionary model that accounts for sensitive periods that occur beyond the early stages of ontogeny.

Frankenhuis, Willem E., and Nicole Walasek. 2020. Modeling the evolution of sensitive periods . Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience 41:100715.

DOI: 10.1016/j.dcn.2019.100715

Sensitive periods in mid-ontogeny are favored by natural selection as a function of the reliability of relevant environmental cues.

Gabard-Durnam, Laurel, and Katie A. McLaughlin. 2020. Sensitive periods in human development: Charting a course for the future. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 36:120–128.

DOI: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.09.003

Figures 1, 2 and 3 and their captions are particularly informative.

Knudsen, Eric I. 2004. Sensitive periods in the development of brain and behavior. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience 16.8: 1412–1425.

DOI: 10.1162/0898929042304796

Focuses on the role of experience in modifying neural circuits during periods of plasticity, leading to connectivity patterns that become stable and less energy intensive, and making up what Knudsen calls the “stability landscape.”

Lillard, Angeline S., and Alev Erisir. 2011. Old dogs learning new tricks: Neuroplasticity beyond the juvenile period. Developmental Review 31:207–239.

DOI: 10.1016/j.dr.2011.07.008

A largely uncritical review and synthesis of well-known studies.

Reh, Rebecca K., Brian G. Dias, Charles A. Nelson III, et al. 2020. Critical period regulation across multiple timescales . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117.38: 23242–23251.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.1820836117

A diverse group of specialists’ account of neurobiological CP mechanisms in animals and humans. Notes that “cortical plasticity is not only influenced by an animal’s life experiences but may also be modified by that of the parents. This occurs via parental behavior during the offspring’s early postnatal life, the in utero environment during gestation, or modification of the parental or fetal germ cells” (p. 23246).

Takesian, Anne E., and Takao K. Hensch. 2013. Balancing plasticity/stability across brain development. Progress in Brain Research 207:3–34.

DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-444-63327-9.00001-1

Illuminates the dynamic between the intrinsic plasticity of CP and the stabilization of neural networks, which limits maladaptive proliferation of circuit rewiring past the CP.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Linguistics »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Accessibility Theory in Linguistics

- Acquisition, Second Language, and Bilingualism, Psycholin...

- Adpositions

- African Linguistics

- Afroasiatic Languages

- Algonquian Linguistics

- Altaic Languages

- Ambiguity, Lexical

- Analogy in Language and Linguistics

- Animal Communication

- Applicatives

- Applied Linguistics, Critical

- Arawak Languages

- Argument Structure

- Artificial Languages

- Australian Languages

- Austronesian Linguistics

- Auxiliaries

- Balkans, The Languages of the

- Baudouin de Courtenay, Jan

- Berber Languages and Linguistics

- Borrowing, Structural

- Caddoan Languages

- Caucasian Languages

- Celtic Languages

- Celtic Mutations

- Chomsky, Noam

- Chumashan Languages

- Classifiers

- Clauses, Relative

- Clinical Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Colonial Place Names

- Comparative Reconstruction in Linguistics

- Comparative-Historical Linguistics

- Complementation

- Complexity, Linguistic

- Compositionality

- Compounding

- Comprehension, Sentence

- Computational Linguistics

- Conditionals

- Conjunctions

- Connectionism

- Consonant Epenthesis

- Constructions, Verb-Particle

- Contrastive Analysis in Linguistics

- Conversation Analysis

- Conversation, Maxims of

- Conversational Implicature

- Cooperative Principle

- Coordination

- Creoles, Grammatical Categories in

- Critical Periods

- Cross-Language Speech Perception and Production

- Cyberpragmatics

- Default Semantics

- Definiteness

- Dementia and Language

- Dene (Athabaskan) Languages

- Dené-Yeniseian Hypothesis, The

- Dependencies

- Dependencies, Long Distance

- Derivational Morphology

- Determiners

- Dialectology

- Distinctive Features

- Dravidian Languages

- Endangered Languages

- English as a Lingua Franca

- English, Early Modern

- English, Old

- Eskimo-Aleut

- Euphemisms and Dysphemisms

- Evidentials

- Exemplar-Based Models in Linguistics

- Existential

- Existential Wh-Constructions

- Fieldwork, Sociolinguistic

- Finite State Languages

- First Language Attrition

- Formulaic Language

- Francoprovençal

- French Grammars

- Gabelentz, Georg von der

- Genealogical Classification

- Generative Syntax

- Grammar, Categorial

- Grammar, Cognitive

- Grammar, Construction

- Grammar, Descriptive

- Grammar, Functional Discourse

- Grammars, Phrase Structure

- Grammaticalization

- Harris, Zellig

- Heritage Languages

- History of Linguistics

- History of the English Language

- Hmong-Mien Languages

- Hokan Languages

- Humor in Language

- Hungarian Vowel Harmony

- Idiom and Phraseology

- Imperatives

- Indefiniteness

- Indo-European Etymology

- Inflected Infinitives

- Information Structure

- Interface Between Phonology and Phonetics

- Interjections

- Iroquoian Languages

- Isolates, Language

- Jakobson, Roman

- Japanese Word Accent

- Jones, Daniel

- Juncture and Boundary

- Khoisan Languages

- Kiowa-Tanoan Languages

- Kra-Dai Languages

- Labov, William

- Language and Law

- Language Contact

- Language Documentation

- Language, Embodiment and

- Language for Specific Purposes/Specialized Communication

- Language, Gender, and Sexuality

- Language Geography

- Language Ideologies and Language Attitudes

- Language Revitalization

- Language Shift

- Language Standardization

- Language, Synesthesia and

- Languages of Africa

- Languages of the Americas, Indigenous

- Languages of the World

- Lexical Access, Cognitive Mechanisms for

- Lexical Semantics

- Lexical-Functional Grammar

- Lexicography

- Lexicography, Bilingual

- Linguistic Accommodation

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Areas

- Linguistic Landscapes

- Linguistic Prescriptivism

- Linguistic Profiling and Language-Based Discrimination

- Linguistic Relativity

- Linguistics, Educational

- Listening, Second Language

- Literature and Linguistics

- Machine Translation

- Maintenance, Language

- Mande Languages

- Mass-Count Distinction

- Mathematical Linguistics

- Mayan Languages

- Mental Health Disorders, Language in

- Mental Lexicon, The

- Mesoamerican Languages

- Minority Languages

- Mixed Languages

- Mixe-Zoquean Languages

- Modification

- Mon-Khmer Languages

- Morphological Change

- Morphology, Blending in

- Morphology, Subtractive

- Munda Languages

- Muskogean Languages

- Nasals and Nasalization

- Niger-Congo Languages

- Non-Pama-Nyungan Languages

- Northeast Caucasian Languages

- Oceanic Languages

- Papuan Languages

- Penutian Languages

- Philosophy of Language

- Phonetics, Acoustic

- Phonetics, Articulatory

- Phonological Research, Psycholinguistic Methodology in

- Phonology, Computational

- Phonology, Early Child

- Policy and Planning, Language

- Politeness in Language

- Positive Discourse Analysis

- Possessives, Acquisition of

- Pragmatics, Acquisition of

- Pragmatics, Cognitive

- Pragmatics, Computational

- Pragmatics, Cross-Cultural

- Pragmatics, Developmental

- Pragmatics, Experimental

- Pragmatics, Game Theory in

- Pragmatics, Historical

- Pragmatics, Institutional

- Pragmatics, Second Language

- Pragmatics, Teaching

- Prague Linguistic Circle, The

- Presupposition

- Psycholinguistics

- Quechuan and Aymaran Languages

- Reading, Second-Language

- Reciprocals

- Reduplication

- Reflexives and Reflexivity

- Register and Register Variation

- Relevance Theory

- Representation and Processing of Multi-Word Expressions in...

- Salish Languages

- Sapir, Edward

- Saussure, Ferdinand de

- Second Language Acquisition, Anaphora Resolution in

- Semantic Maps

- Semantic Roles

- Semantic-Pragmatic Change

- Semantics, Cognitive

- Sentence Processing in Monolingual and Bilingual Speakers

- Sign Language Linguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Sociolinguistics, Variationist

- Sociopragmatics

- Sound Change

- South American Indian Languages

- Specific Language Impairment

- Speech, Deceptive

- Speech Perception

- Speech Production

- Speech Synthesis

- Switch-Reference

- Syntactic Change

- Syntactic Knowledge, Children’s Acquisition of

- Tense, Aspect, and Mood

- Text Mining

- Tone Sandhi

- Transcription

- Transitivity and Voice

- Translanguaging

- Translation

- Trubetzkoy, Nikolai

- Tucanoan Languages

- Tupian Languages

- Usage-Based Linguistics

- Uto-Aztecan Languages

- Valency Theory

- Verbs, Serial

- Vocabulary, Second Language