- Psychology Programs

How to Become a Research Psychologist – Schooling and Degree Guide [2024 Guide]

In contemplating psychology as an occupation, thoughts wander to hands-on professions such as counseling and therapy. However, a sizable segment of the field involves little practical work, and is more concerned with theoretical aspects of psychology.

Do you prefer fixed numbers to subjective diagnoses? Scientific observations to patient treatment? If so, perhaps a career in research psychology is for you.

Are You an Analytical Person?

Before jumping on the research psychology bandwagon, ask yourself if you’re truly an analytical person. An indispensable prerequisite for a career in research psychology is having a firm grasp of – and perhaps a natural inclination toward –working with numbers and data. Dictionary.com defines the term analytic thinking as “the abstract separation of a whole into its constituent parts in order to study the parts and their relations,” and that’s exactly what research entails.

Hence, questions it would behoove you to ask are: How did I cope with math in school? Did I do well in my college statistics class? If the answer is negative, could you learn to enjoy it? Are you prepared to make the sacrifices necessary to become a resourceful statistician? In going forward with this profession, a resounding “yes” should be your only answer.

What is a Research Psychologist?

Research psychologists are found in every branch of psychology. It is often not a specific job title, but rather represents an area of emphasis for psychologists when undertaking research in their specific field, such as developmental psychology , industrial-organizational psychology , biological psychology , social psychology , and the like.

For example, a social psychologist might undertake research on the manner in which children are socialized in rural, highly religious communities and compare that to the way children in urban, non-religious communities are socialized.

Another example might be a health psychologist conducting research on nutrition and wellness for a government agency.

Research psychologists are trained in experimental methods and statistics. They utilize the scientific method to formulate and test hypotheses, develop experiments, collect and analyze data, and use that information to develop conclusions and report on their findings.

Two common types of studies research psychologists undertake are:

- Experiments – research psychologists conduct experiments both in controlled lab settings and out in the field. An example might be examining the social behaviors of small groups in a rural town.

- Case studies – psychologists conducting research often utilize this method when studying an individual or small group. Observing how a particular family overcomes the trauma of a natural disaster is an example of a case study.

Despite the significant differences in the ways that research psychologists conduct their studies, the tie that binds research psychologists together across disciplines is that at the heart of their research, they are seeking to understand better how humans and non-human animals feel, think, learn, and act.

What Does a Research Psychologist Do?

A research psychologist carries out many duties as it pertains to studying human behavior. Many research psychologists work for private companies or organizations conducting studies pertinent to the purpose of their employer. For example, a university might employ a research psychologist to explore methods to improve teaching and learning.

Alternatively, a research psychologist working for a non-profit human services organization might study ways to improve the bonding experience between adopted children and their adopted parents.

Research psychologists also conduct much research on behalf of governmental agencies. For example, a psychologist may research the efficacy of psycho-social intervention programs implemented by the Bureau of Prisons, looking for positive outcomes for participants in the program.

Likewise, a research psychologist working for the National Institute of Mental Health may investigate current rates of certain psychological disorders among the general population.

Other psychologists with training in research work in academic settings. Colleges and universities employ research specialists to conduct research or even assist with the development of on-campus policies and procedures regarding psychological research. For example, a research psychologist might devise rules and regulations pertaining to human or animal-based research in the psychology department.

Many research psychologists also teach. Again, colleges and universities – both public and private – might hire a psychologist with training in research to teach undergraduate courses in various genres of psychology.

There would also be opportunity for more specialized teaching assignments, such as those that train graduate or doctoral students to conduct research of their own. Typical course assignments for research psychologists include research psychology, statistics, and ethics.

Yet other research psychologists are employed by private businesses to help them create improved working environments. Research psychologists might be employed to investigate issues like low employee morale or low production rates. They may also seek to improve workplace safety by examining the types of accidents that occur, when and where they occur, and the conditions under which they occur as well.

What are the Degree and Schooling Requirements to Become a Research Psychologist?

A career in psychology usually requires a graduate degree, and the sub-field of research psychology is certainly no different.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, most research psychologists need not just a Master’s degree, but a full-out Ph.D. or PsyD, to land a job of pleasing stature. Hence, normally expect 5-6 years of study even after graduating college.

Having completed coursework in experimental psychology and statistics will be of great importance, probably more so than for you than any other type of psychologist.

Obtaining psychology license generally require pre-doctoral and postdoctoral supervised experience, an internship, or a residency program, which may span 12 months or more. Sometimes more than one of them is needed.

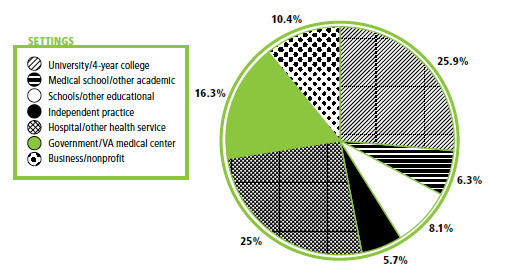

Where Does a Research Psychologist Work?

Research psychologists typically work in the following environments:

- Colleges and universities

- Law enforcement agencies

- Consulting and private research firms

- Government research groups

- Government and Private businesses

- War veterans and disaster post-traumatic counseling

What Skills are Required for a Research Psychologist?

Successful research psychologists have the following skills :

- Research skills – It goes without saying that research psychologist must be highly trained in research methodologies, including experimental design, observational techniques, and sampling methods.

- Math and statistics skills – Research psychologists must also have a strong grasp on the statistical methods used to analyze research, including qualitative and quantitative methods of analyzing and interpreting data.

- Computer literacy – Psychologists in this field are required to be highly computer literate. Computers and computer programs are used for all phases of research, from designing research studies to analyzing data to reporting data for publication.

- Speaking and writing skills – Research psychologists must be able to clearly and accurately summarize their findings both in verbal and written forms. Good linguistic skills are also necessary for interacting with other members of the research team and with subjects participating in the study.

- Analytical skills – Analytical skills are necessary because they need to be able to see both the fine details and the bigger picture. Higher-ordered analytical skills assist researchers in identifying patterns, highlighting anomalies, and sifting through mountains of data to come to a logical conclusion.

- Skepticism – It can be difficult for researchers to avoid seeing what they want to see in their research. As a result, research psychologists need to have the ability to critically evaluate their work and the work of others.

What is the Employment Outlook for Research Psychologists?

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the job outlook for psychologists as a whole is 6 percent.

Unfortunately, the BLS does not offer details regarding the employment outlook specifically for research psychology. While the field will most likely not grow as quickly as other psychology disciplines, it’s still reasonable to assume that strong growth will occur. This is due in large part to an increased interest in the underlying mechanisms of behavior, such as genetics and environmental factors.

Because research psychologists specialize in conducting studies on popular topics like drug and alcohol addiction, there should be plenty of job opportunities in the coming years. This is especially true of research psychologists that have an advanced degree, like a doctorate, or have additional training in psychological research methods.

What is the Salary of a Research Psychologist?

As of February 2024, research psychologists earn a median salary of $127,818 per year. However, as in many other areas of psychology, salaries fluctuate considerably depending on the number of years of experience in the industry, as well as the sector of employment.

Individuals who go into industrial-organizational psychology average as much as $132,191 annually, which is more than any other area of psychology.

Related Reading

- What is the Difference Between Masters and PhD in Psychology?

- What Can You Do With a Bachelor of Arts Psychology Degree?

- Difference Between Applied Psychology and Experimental Psychology

- What are the Differences Between Research Psychology and Applied Psychology?

- What is the Difference Between Counseling and Clinical Psychology Graduate Programs?

Useful Resources

- Society of Experimental Social Psychology

- Society of Experimental Psychologists

- Division 3: Experimental Psychology

- Associate Degrees

- Bachelors Degrees

- Masters Degrees

- PhD Programs

- Addiction Counselor

- Criminal Psychologist

- Child Psychologist

- Family Therapist

- General Psychologist

- Health Psychologist

- Industrial-Organizational

- Sports Psychologist

- See More Careers

- Applied Psychology

- Business Psychology

- Child Psychology

- Counseling Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Industrial Psychology

- Sports Psychology

- See More Programs

- Clinical Psychology Degree

- Cognitive Psychology Degree

- Forensic Psychology Degree

- Health Psychology Degree

- Mental Counseling Degree

- Social Psychology Degree

- School Counseling Degree

- Behavioral Psychologist Career

- Clinical Psychologist Career

- Cognitive Psychologist Career

- Counseling Psychologist Career

- Forensic Psychologist Career

- School Psychologist Career

- Social Psychologist Career

Psychology Online Degrees

How to Become a Research Psychology

Key Takeaways:

- Educational background: To become a research psychologist, it is important to pursue undergraduate majors in research psychology and then enroll in graduate programs specifically designed for research psychology.

- Skills and qualities: Research psychologists need to possess analytical and communication skills, as well as soft skills such as the ability to teach and extensive knowledge of human behavior.

- Career opportunities: Research psychologists can pursue various career paths, including academic researcher, research psychologist, consulting services, government positions, and clinical therapists.

- Steps to become a research psychologist: The journey involves obtaining a bachelor’s degree, followed by a master’s degree and a doctorate degree. Relevant work experience, job training, and certifications are also important.

- Salaries and job outlook: Research psychologists can expect average salaries and a positive job outlook with growth opportunities in the field.

- Challenges and FAQs: Challenges in the field include job stability, geographic location impacting job opportunities, and maintaining work-life balance and job satisfaction. It is also helpful to learn from experienced professionals like Juhi Rathod.

- Conclusion: Becoming a research psychologist requires a specific education and skill set, but can lead to rewarding career opportunities and personal growth.

Research psychology plays a vital role in understanding the complexities of human behavior and the mind. In this article, we will explore the significance of research psychology and provide an overview of the topics covered. From uncovering new insights to driving evidence-based practices, this section sets the stage for an enlightening journey into the world of research psychology.

Some Facts About How to Become a Research Psychologist:

Overview of the article.

Education and training programs, undergraduate majors, and graduate programs. Requirements for a doctorate degree, skills, qualities, analytics, communication, and knowledge of human behavior. Job opportunities, academic research, government positions, clinical therapy—plus steps to get a bachelor’s , master’s , or doctorate . Work experience, job training, certifications, salaries, job outlook, earnings, and growth prospects. Challenges, precarious jobs, and geographic location also important. Learn all you can and make informed decisions.

Become a Research Psychologist

Importance of research psychology

Research psychology is crucial for understanding human behavior and mental processes. Scientists study data to create evidence-based practices in multiple areas. They provide insight into cognition, emotions, and behavior which can inform educational and therapeutic interventions.

Aspiring research psychologists learn research methods, statistics, and theoretical frameworks during undergraduate and graduate programs. Doctoral students complete courses, exams, and a dissertation based on original research. Additionally, they receive clinical training to apply their findings in the real world.

Research psychologists possess analytical skills, communication skills, and soft skills to evaluate research, explain findings, and build relationships. They also teach others about psychological concepts and research methodologies. With extensive knowledge of human behavior, they can identify patterns, trends, and individual differences.

The importance of research psychology is immense. It helps improve lives through evidence-based practices and interventions. Juhi Rathod , a renowned research psychologist, conducted a study which showed that research psychology has played a major role in advancements in many fields.

In the realm of research psychology, the mind is a playground and dark humor is the key to success.

Education and Training

When it comes to becoming a research psychologist, education and training play a crucial role. In this section, we will explore various aspects of the educational journey aspiring research psychologists undertake. From undergraduate majors that pave the way for research psychology to the rigorous requirements of doctoral degree programs, we’ll uncover the essential elements that shape the path to success. Additionally, we’ll touch upon research methods, coursework, and the integration of clinical techniques and therapy training, along with the essential clinical psychology internship experience.

Undergraduate majors for research psychology

Psychology: Learn about human behavior, cognitive processes, and research methodologies in a psychology major.

Cognitive Science: Interdisciplinary major combining psychology, computer science, linguistics, and philosophy to study the mind.

Neuroscience: Major in neuroscience focuses on the biological basis of behavior. Explore brain function, neural networks, and neuroimaging techniques.

Sociology: Sociology majors analyze social interactions and structures. Study social inequality, group dynamics, and social change.

Anthropology: Anthropology majors investigate human cultures, societies, and evolutionary history. Gaining insights into universal behaviors and cultural diversity.

Statistics: Statistics major is key for rigorous research. Train in data analysis and hypothesis testing.

These majors give aspiring research psychologists a foundation in psychology, cognitive science, neuroscience, sociology, anthropology, and statistics. Combining knowledge from these disciplines with specialized coursework in research methods and psychological theories prepares graduates for a career in research psychology.

Plus, students can minor or take elective courses in development psychology, abnormal psychology, social psychology, and industrial-organizational psychology .

Juhi Rathod’s journey is an example of the diverse educational paths of those in research psychology. She completed her anthropology degree with focus on cross-cultural studies, then got a Master’s in cognitive science and a doctoral program in clinical psychology. Her interdisciplinary background and research experience allow her to make significant contributions in studies relating cultural factors and mental health outcomes. Her educational trajectory shows the wide range of undergraduate majors leading to a research psychology career!

Graduate programs for research psychology

Graduate programs for research psychology offer specialized courses, such as those on research methodology, statistical analysis, experimental design, and data collection . These courses give students a strong base in quantitative and qualitative research methods.

Graduates have access to a lot of research opportunities throughout their studies. They can work with renowned faculty and collaborate with fellow students. This hands-on experience helps students to develop critical thinking and get practical research experience.

The collaborative environment of these programs further benefits students. They engage in discussions, present their findings, and get feedback from peers and faculty. This helps them to develop communication and presentation skills .

In addition, these programs provide extracurricular activities . Students can attend conferences, publish papers, or do community-based research projects.

Students can explore diverse research topics, including social behavior, neurological disorders, cognitive psychology, developmental psychology, clinical psychology, and industrial-organizational psychology .

Graduate programs for research psychology have seen a shift over time. Earlier, the focus was on theoretical knowledge without much emphasis on practical application. However, due to advancements in technology and the need for evidence-based practices, these programs now prioritize hands-on experience and practical training. This has resulted in graduates who are well-prepared to tackle complex challenges and contribute to research.

Doctoral degree requirements

To earn a doctoral degree in research psychology , you must meet certain requirements , showcasing your expertise and commitment. You typically need comprehensive coursework, research methods training , and clinical techniques education. Plus, you’ll need strong analytical skills , effective communication, and the ability to teach. And, of course, extensive knowledge of human behavior .

You must first obtain a bachelor’s and master’s before starting the doctoral program. Plus, relevant work experience and job training are also necessary.

The doctoral degree requirements for research psychology are rigorous. Coursework is designed to give you the skills and knowledge to conduct advanced research. You must study statistical analysis, experimental design, data collection, and data interpretation. Clinical techniques and therapy training are also important.

To get the doctoral degree , you must finish a dissertation . You’ll do original research with the help of faculty advisors. This involves proposing a research topic, conducting literature reviews, collecting data via surveys or experiments, analyzing the findings, and presenting the results in writing.

So, if you have strong analytical skills , and understand human behavior , you might be a good fit for the program. On completion, you can pursue various career paths, like academic researcher, or roles in consulting services or government agencies.

Ready to explore the depths of research methods? Unlock the secrets of data and psychological gold!

Research methods and coursework

Gaining proficiency in research is key for aspiring psychologists. Coursework and hands-on experience help. Key aspects include:

- Research Design : Selecting experimental, correlational or qualitative approaches based on the research question.

- Data Collection : Surveys, interviews, observations, case studies, and experiments.

- Statistical Analysis : Descriptive stats, inferential stats (t-tests, ANOVA), and advanced analytical techniques (regression analysis).

- Ethical Considerations : Ensuring confidentiality, informed consent, fair treatment, and protocols.

These skills are vital for aspiring psychologists, as they prepare to explore the depths of the mind. Clinical techniques and therapy training take them on a wild ride.

Clinical techniques and therapy training

Research psychology students not only gain research methods and coursework knowledge, but also specialized training in clinical techniques. They learn how to assess, diagnose mental disorders, and apply therapeutic interventions. Through supervised practice experiences, they can refine their skills and gain confidence.

They acquire knowledge of different therapies, such as CBT, psychodynamic, humanistic, and family systems . They learn how to tailor these approaches to the needs of each client. Cultural competence is necessary, too, to be sensitive to diverse backgrounds and identities.

Analytical skills and communication skills are essential for aspiring research psychologists. Soft skills , like empathy, active listening, and compassion, help build a strong therapeutic alliance with clients. Extensive knowledge of human behavior is also vital to understand the root of mental health issues and create effective treatment plans.

Theoretical and practical experience both play a role in becoming a research psychologist. Comprehensive education programs help future researchers acquire the necessary skills to contribute to psychological phenomenon understanding and mental health improvement.

Clinical psychology internship

Interns gain practical experience in conducting psychological assessments and administering therapy sessions . They learn to collaborate with multidisciplinary teams , to develop comprehensive treatment plans for clients. Furthermore, they get to observe seasoned clinicians , deepening their understanding of clinical practices.

During the internship, students gain problem-solving, critical thinking, and communication skills . They are exposed to various therapeutic techniques and interventions, gaining knowledge of human behavior and mental health issues . Clinical psychology internships bridge academic learning and professional practice, offering crucial experiential training for future careers in research psychology.

Internships often require a significant time commitment. Full-time or part-time hours may be required, based on the program’s requirements. Additionally, interns must follow ethical guidelines and maintain client confidentiality . These experiences give interns an immersive learning environment in which they can refine skills and gain confidence.

The value of a clinical psychology internship is exemplified by Juhi Rathod’s experience. At a renowned mental health clinic, Juhi worked with clients and conducted assessments, under the supervision of experienced clinicians. She developed treatment plans and implemented evidence-based interventions. Through this direct experience, Juhi gained practical skills and a profound understanding of human behavior and mental health. This internship was instrumental in Juhi’s career as a research psychologist, equipping her with the necessary skills and knowledge.

Skills and Qualities

To become a research psychologist, it is vital to possess a range of essential skills and qualities. In this section, we will explore the different aspects that contribute to a successful career in this field. From analytical skills to communication proficiency , from the importance of soft skills to the ability to teach, and the necessity of extensive knowledge of human behavior, we’ll uncover the key components required to excel as a research psychologist.

Analytical skills

Research psychologists use analytical skills to examine vast amounts of data collected during experiments/studies. They use statistical software to organize, clean, and analyze data, so they can make accurate conclusions. Analytical skills are also necessary when conducting literature reviews and evaluating existing research. Research psychologists must assess the quality/validity of studies, and identify any potential biases/limitations.

Analytical skills are important during the design phase of studies/experiments. Research psychologists plan their methodologies, pick relevant variables to measure, decide on sample sizes, and devise suitable statistical analyses.

Analytical skills are needed for conducting research and disseminating findings. Research psychologists need to be able to explain complex info in a clear way. They must give oral presentations and written reports that people can understand.

To become a successful research psychologist, professionals must develop/improve their analytical skills. They can do this by taking courses/going to workshops/conferences on statistical analysis techniques, staying up to date with research methodologies, and working with other experts.

Communication skills

Research psychologists must have strong communication abilities to share details and swap info with colleagues, customers, and other key people. They have to be adept at various forms of communication, including verbal, written, and nonverbal. Being able to communicate clearly and concisely is vital for presenting research, partnering with team members, and conveying complex psychological ideas to a larger audience.

- Research psychologists must be able to express their thoughts and discoveries in written form, whether it be with academic papers, research reports, or grant proposals.

- Verbal communication skills are necessary when presenting research in a conference or in an academic setting. Research psychologists have to communicate their ideas well and present talks that fascinate and inform viewers.

- Active listening enables research psychologists to comprehend the needs and viewpoints of others. This ability is especially critical when dealing with customers or interviewing people as part of research.

- Nonverbal communication helps build a rapport and trust with clients or study participants. Research psychologists need to be aware of their body language, facial expressions, and hand gestures when interacting with others.

- Adapting one’s communication style is essential for talking with people from diverse backgrounds who may have different communication styles or cultural norms.

- Interpersonal skills are also important as they allow research psychologists to cooperate successfully with colleagues, work in teams, form professional connections, and solve potential issues that may arise during research projects.

Furthermore, research psychologists have to be good listeners. Being able to listen actively enables them to completely understand their client’s worries while providing the right help.

To improve their communication skills, research psychologists can join workshops or seminars on effective communication strategies. They can also request feedback from their peers or mentors about their communication style so they can recognize areas that require improvement. Additionally, staying up to date with advancements in communication technology and tools can help research psychologists effectively use new methods of communication in their work. All in all, great communication skills are essential for research psychologists to be successful in their field and have an impactful effect through their work.

Soft skills

Psychologists need more than just great analytical and communication skills. They must also possess soft skills to effectively connect with clients. This includes being empathetic, patient, and understanding to create a safe environment. Listening skills are essential, as well as strong problem-solving abilities .

Apart from technical knowledge, soft skills are essential for success. Effective communication is vital to establishing trust and rapport. Strong interpersonal skills are needed to collaborate with others.

Empathy and compassion towards clients are essential. Psychologists must be sensitive to cultural differences, display emotional intelligence, and have a non-judgmental attitude. A person-centered approach allows for tailored treatment plans.

Soft skills support the core competencies of research psychology. They help psychologists communicate effectively , collaborate with colleagues , and provide personalized plans for clients . These skills are invaluable and lead to a positive impact on the well-being of others.

Ability to teach

Research psychologists must have the ability to teach. They often work in academia, both conducting research and teaching courses related to psychology. Being able to educate the next generation of psychologists is crucial for understanding human behavior.

They need strong communication skills to explain complex psychological concepts and theories to their students. Breaking down these difficult topics in an understandable way is important. They should also be able to engage students in interactive discussions. Plus, the patience and empathy to work with various backgrounds and learning styles is necessary.

Furthermore, research psychologists must stay informed on the latest research findings and advancements in the field. Incorporating this information into lectures and talks is vital. As educators, they have the chance to inspire their students and ignite a passion for psychology. By sharing their own experiences and insights in the field, they can motivate these individuals to pursue further studies or careers in psychology.

Overall, the capacity to teach is essential not only for knowledge transfer but also for preparing future professionals in the field of psychology. Research psychologists with strong teaching skills can have a great impact on student learning outcomes and the development of psychological knowledge.

Extensive knowledge of human behavior

Research psychologists gain knowledge of human behavior through education and training. Undergrad majors in psychology provide basic principles, while graduate programs enhance understanding via specialized courses. Doctoral degree requirements include research methods and coursework on human behavior.

In addition, knowledge is developed through hands-on experience. Research psychologists conduct studies, analyze data, and contribute to existing research. This practical experience allows them to gain a deeper insight into human behavior.

To further enhance their knowledge, research psychologists partake in professional development activities, such as attending conferences and workshops. They also stay updated with the latest research advancements. This continuous learning ensures they are aware of new findings and theories related to human behavior.

By expanding their knowledge base, research psychologists are better equipped to design and carry out high-quality studies. This enables them to make meaningful contributions to the field of psychology, whether it be investigating cognitive processes or exploring social behaviors.

Career Paths and Job Opportunities

When it comes to career paths and job opportunities in the field of research psychology , the options are diverse and exciting. From academic research and consulting services to government positions and clinical therapy, the possibilities are vast. Top universities offer excellent prospects for those aspiring to become research psychologists . Let’s explore these compelling avenues and the potential they hold for individuals passionate about the fascinating world of research psychology.

Academic researcher

Academic researchers are key to psychology. They design and run experiments to answer questions or hypotheses. This involves planning every part, from selecting participants to manipulating variables and measuring results. Through surveys, observations, or lab experiments, researchers collect and analyze data. Advanced stats help them make sense of the data.

To share their research findings, they publish articles in peer-reviewed journals . This allows experts to evaluate, replicate, and build on their work. Academic researchers also develop theoretical frameworks to explain human behavior. Through research, they refine existing theories or create new ones using empirical evidence.

Mentoring students is another part of their role. They guide undergrad and grad students wanting careers in research psychology. They help with research methods, literature reviews, and supervise student projects. They also teach critical thinking skills.

External funding supports their research projects. They seek grants from government agencies or private foundations, writing grant proposals and competing for funding.

Being an academic researcher comes with challenges. They must stay up-to-date with advancements in the field. This requires time to read scientific literature and attend conferences and seminars. Long hours, incl. evenings and weekends, are needed to meet deadlines and complete projects. Despite challenges, academic researchers find fulfillment in making meaningful contributions and expanding the knowledge base of psychology. They are like mind-readers, deciphering the complexities of human behavior.

Research psychologist

Research psychologists come with a strong educational background. They begin with an undergraduate degree in psychology or neuroscience . Then, they pursue a master’s and doctoral degree which provides specialized training in research methods, data analysis, and theoretical frameworks . Plus, they gain skills to communicate scientific findings through presentations, publications, and collaborations with other researchers .

These professionals have analytical capabilities to design experiments, construct research protocols, and decode complex data sets. Communication skills are vital to convey their results to both academic and public audiences. Further, they must have soft skills like critical thinking, problem-solving, and attention to detail .

Research psychologists must also teach others about psychological concepts and research methods . They usually serve as instructors at universities or present training sessions for those wanting to conduct research. This requires extensive understanding of human behavior theories and principles .

Careers in research psychology are found in academia, consulting, government, and clinical practice . Universities may have departments dedicated to research psychology which provide opportunities to work with other experts in the field.

To become a research psychologist, one needs education, training, and experience . With a strong foundation in psychology and research methods, they can pursue their passion to understand human behavior and improve people’s well-being.

Consulting services

Research Psychology Consulting Services

Consultants with backgrounds in research psychology are vital for interpreting psychological knowledge into useful strategies. They use their knowledge of human behavior, data analysis skills, and research processes to identify organizational needs, do surveys or experiments, interpret data, and make actionable outcomes. This expertise allows them to suggest evidence-based recommendations on things such as employee motivation, consumer behavior, organizational culture, leadership success, or marketing tactics.

Additionally, consulting services in research psychology cover a broad variety of specializations. Some consultants may focus on market research and give insights on consumer tastes and decision making. Others might be experts in organizational consulting and help businesses to optimize productivity and staff welfare. Furthermore, consultants can give expert advice on public policy, criminal justice systems, healthcare, and educational settings.

A Franco et al. (2019) study found that companies that used research psychology consulting services had improved decision-making processes and got valuable insights into consumer behaviors.

Research psychologists have important government positions – and there’s nothing scarier than a politician!

Government positions

Research psychologists who work in government roles collaborate with policymakers and other stakeholders. They identify research needs, develop plans, and conduct studies. To gather information, they use surveys, interviews, observations, or experiments . Government roles entail analyzing data using statistical methods and interpreting the findings. They also create intervention programs and assess their effectiveness in tackling social issues. Research psychologists often join interdisciplinary teams, working with economists, sociologists, educators, etc. Part of their job is to present research results in reports, talks, or publications .

Government positions give access to resources such as funds and large datasets. Research psychologists can use these to conduct studies that influence policy decisions. Their expertise is appreciated in government organizations due to their evidence-based knowledge . An example is Dr. Stanley Milgram . He conducted his obedience experiments at Yale University and later served as a consultant for various government agencies. His work revealed facts about human behavior and conformity, shaping both academic research and government policies. This emphasizes the power of research psychologists in government roles to shape our understanding of human behavior and inform policies that benefit individuals and society.

Clinical therapists

Clinical therapists have expertise and analytical skills to meet individual’s needs. They also demonstrate excellent communication, empathy, patience, and compassion . These allow them to connect with clients and create a supportive environment.

These professionals also teach people about human behavior and therapy techniques. This makes them qualified to become academic researchers or pursue careers in research psychology.

Furthermore, they can get involved in consulting services or governmental positions dealing with mental health research.

To become a clinical therapist requires a bachelor’s degree in psychology, followed by a master’s degree and doctorate degree .

Their salaries depend on experience and location. Job prospects for clinical therapists are rising due to increasing need for mental health services.

Tip: Aspiring clinical therapists should gain experience by interning or volunteering at mental health clinics/facilities. They should also get certifications that match their areas of interest in clinical therapy.

Top universities

These top universities provide majors in research psychology . Graduate programs here focus on advanced coursework and specialized training in various areas of research psychology. Doctoral degrees emphasize research experience and call for students to contribute to the field.

The coursework prepares students to design, conduct empirical studies, analyze data, and draw meaningful conclusions. Clinical techniques and therapy training are also prioritized, with internships giving students real-world experience.

These institutions offer great opportunities for aspiring research psychologists . Graduates may choose to pursue careers as researchers, practitioners, or clinical therapists. Their reputations can help them get jobs in academia, industry, or government sectors. Education here gives individuals a strong foundation and opens up diverse career pathways.

Steps to Become a Research Psychologist

Embarking on a journey to become a research psychologist involves several key steps. From pursuing a bachelor’s degree to gaining relevant work experience, each sub-section in this section will illuminate the path towards achieving success in this field. With a comprehensive educational foundation and the necessary training, aspiring research psychologists can gain the expertise needed to make meaningful contributions to the field of psychology .

Bachelor’s degree

A Bachelor’s degree in research psychology is essential for those wanting to pursue a career in this field. The majors offered include psychology, neuroscience, and behavioral science. These courses explore human behavior and teach students research methods and statistics. They also cover psychological theories, ethics in research, and data analysis.

Communication skills are vital for a research psychologist. Bachelor’s programs help develop these by requiring students to present their findings orally or in writing. They also focus on soft skills such as critical thinking, problem-solving, collaboration, and time management.

A Bachelor’s degree in research psychology provides knowledge of human behavior across different populations and settings. This assists researchers in developing research questions that address real-world issues. Many Bachelor’s programs provide teaching experience through teaching assistant positions and student-led seminars. This helps aspiring research psychologists to effectively explain complex concepts.

Master’s degree

A Master’s degree is a major milestone for those seeking to become research psychologists . It provides the essential knowledge and abilities needed to delve into the field of psychology.

Building on the basics learned at the undergraduate level, this program offers specialized courses, research method training, and hands-on experience . Students can explore more specific topics such as cognitive, social, or developmental psychology. Research methods classes show how to design, data-collect, analyze, and interpret findings .

Practical experience can be gained through internships or assistantships, giving students real-world experience under expert mentorship . Group projects or research teams also give the chance to collaborate, stimulating critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

The Master’s program furthers knowledge of human behavior with advanced theories and concepts. It may even lead to a doctoral program , as some require an advanced degree before acceptance.

In total, a Master’s degree not only expands understanding, but it is also a pathway to greater career prospects in academia, research institutes, or consulting services.

Doctorate degree

A doctorate degree in research psychology is an essential step for those wishing to progress their career. This degree provides a deep understanding of research methods, theoretical concepts, and data analysis techniques . Through the doctoral program, students learn through coursework and practical research experiences.

Moreover, these are some of the key elements of a doctorate degree in research psychology:

- Comprehensive coursework – covering topics such as experimental design, statistical analysis, psychometric assessment, and qualitative research methods.

- Research-focused dissertation – students must complete an original research project leading to a dissertation.

- Collaborative mentorship – with experts in their respective fields, guiding students through conducting research.

- Professional development opportunities – like attending conferences, presenting research findings, publishing scholarly articles, and interdisciplinary collaborations.

- Skills for career advancement – opening up opportunities in academia, government, private organizations, and consulting firms.

- Relevant work experience – to truly understand human behavior.

In addition, students gain specialized knowledge in specific areas of psychology, allowing them to make meaningful contributions to the field. Achieving a doctorate degree in research psychology is a commitment to the scientific study of human behavior and establishes the individual as an expert in their field.

Relevant work experience

Hands-on Research: Working as a research assistant or intern is key for gaining relevant experience in research psychology. This grants the opportunity to take part in studies, collect data, and analyze results with guidance from experienced researchers.

Data Analysis: Knowing statistical software and data management is critical for research psychologists. Working in the field can give you proficiency in these areas, which are vital for interpreting research results correctly.

Collaborative Skills: Working with a team of researchers during relevant work experience helps build collaborative skills. This includes communicating ideas, sharing responsibilities, and contributing to group discussions and decision-making.

Ethical Considerations: Relevant work experience gives individuals knowledge on how to protect participants’ rights and ensure ethical studies.

Research Design: Learning about different research methodologies and study designs is part of relevant work experience. It helps to understand how to use different approaches to answer research questions.

Networking: Relevant work experience also gives the chance to network with professionals in the field. This could lead to collaborations, mentorships, and job prospects in the future.

In conclusion, gaining experience through relevant work opportunities is invaluable for aspiring research psychologists. It boosts their knowledge and skills, enabling them to pursue advanced degrees or enter the workforce as successful professionals in psychology.

Job training and certifications

Research psychologists need to go through rigorous training in various research methods and techniques. They need to learn how to design experiments, collect data, analyze findings, and draw meaningful conclusions. Additionally, gaining hands-on experience in clinical settings is crucial for understanding different therapeutic techniques and their practical applications.

Job training for research psychologists may also involve teaching opportunities to improve communication skills and effectively convey complex psychological concepts. Internships provide additional practical experience and the chance to apply theoretical knowledge in real-world scenarios.

Some specialization areas within research psychology require certifications. For example, to focus on neuropsychology or child psychology, additional certifications are necessary. Networking with other professionals in the field can lead to collaborations and future job prospects.

The journey to become a research psychologist starts with obtaining a bachelor’s degree in psychology or a related field. This is followed by a master’s degree specializing in research psychology and a doctorate degree that usually includes coursework and dissertation research.

Gaining relevant work experience alongside academic pursuits can help individuals develop practical skills and demonstrate their competency in the field. This can be achieved by working as a research assistant or participating in independent research projects.

According to a study (Smith et al., 2018), individuals who receive job training and certifications in research psychology are likely to secure higher-paying positions and experience increased job satisfaction.

Salaries and Job Outlook

Salaries and job outlook in the field of Research Psychology – uncover the average salaries and job growth opportunities that await aspiring research psychologists.

Average salaries

Research psychologists can anticipate an array of salaries based on their credentials and experience. The reference data suggests that professionals in this field can expect competitive remuneration for their knowledge and efforts. The next few paragraphs will provide more info about the average salaries for research psychologists.

A table below displays details regarding the average salaries in research psychology. The data is based on the reference article and provides a summary of the payment that professionals in this field can anticipate. Remember that these figures are averages and can differ based on factors such as geographic area, years of experience, and level of education.

| Job Position | Average Salary Range |

|---|---|

| Academic Researcher | $60,000 – $90,000 per year |

| Research Psychologist | $80,000 – $120,000 per year |

| Consulting Services | $70,000 – $100,000 per year |

| Government Positions | $70,000 – $110,000 per year |

| Clinical Therapists | $50,000 – $80,000 per year |

It’s essential to bear in mind that these figures serve as a general guide and can vary based on various factors mentioned before. With more experience and high degrees such as a Ph.D., research psychologists usually have higher earning capacity within their profession.

Job outlook and growth

The job prospects for research psychologists are bright. Demand is growing as people recognize the significance of psychological research. Research psychologists help to uncover human behavior and devise effective interventions.

Moreover, there are many paths to take:

- Universities offer stability and advancement.

- New areas, like neuroscience and positive psychology , need exploration.

- Evidence-based practices are sought after in healthcare, education, and business .

Furthermore, research psychologists may also work in consulting, government, and clinical therapy roles. This breadth of opportunities allows people with diverse skills to contribute.

Research psychology offers fascinating chances to study human behavior. In addition to academia, there are chances to use research findings to make real changes. The field is rapidly developing, with technology and mental health awareness creating an increased demand for qualified research psychologists.

Challenges and FAQs

Balancing the demands of a research psychologist career comes with its fair share of challenges and common questions. From job stability in prekäre jobs to the impact of geographic location on job opportunities, and the delicate balance of work-life balance and job satisfaction, this section explores the hurdles that aspiring research psychologists may encounter. We will also gain insights from Juhi Rathod’s experience in navigating and overcoming these challenges throughout her career.

Jobs and job stability

Job insecurity and financial challenges are common in the field of research psychology . Contract-based work and short-term projects lead to job instability, which can make it difficult to plan for the future and meet financial obligations.

Career progression can also be tricky, as research psychologists have to move around a lot. This can provide valuable experiences, but it’s hard to establish a stable career trajectory.

Still, many find fulfillment and satisfaction in their work. Passion for advancing knowledge and understanding human behavior drives them forward. Networking and building strong professional connections can help mitigate some of the job stability challenges.

Geographic location and job opportunities

Geographical placement has a great effect on the job chances for research psychologists. This field is not restricted to a certain area, as there is a need for experts in several locations around the world.

For instance, research psychologists can find roles in academic institutions. They can do research and teach students in the field.

Additionally, they are able to take up government positions. These involve researching to provide data for policy making and decisions.

Consulting services also offer job openings for research psychologists. Here, they can give advice and guidance to customers in different industries.

These are just a few of the various job opportunities available to research psychologists, based on their geographical location.

Moreover, researchers may find special jobs related to their research interests or specific expertise. For example, they may take part in innovative projects or collaborate with teams in their area.

Location also has an effect on the funds and resources for research. Some areas may have more funding for psychological research than others, which can influence job opportunities for research psychologists.

Juhi Rathod’s experience (source name) shows that researchers in psychology frequently have to face problems regarding precarious working conditions and job stability. This implies that although there may be job opportunities based on geography, professionals in this field may still confront difficulties when it comes to career stability.

Research psychology may be interesting, but it can disrupt your work-life balance and job satisfaction.

Work-life balance and job satisfaction

Research psychologists must have a healthy work-life balance and job satisfaction. It’s essential to their productivity. They need strategies to manage their time; like prioritizing tasks, setting boundaries, and having a plan for personal time.

Practicing self-care like exercise, mindfulness, and socializing with friends and family – can help alleviate stress and boost job satisfaction.

It’s also important for research psychologists to have a supportive work environment. One that values employee well-being and offers flexible hours, breaks, and mental health support. Plus, professional growth opportunities can enhance job satisfaction too.

Achieving a good work-life balance is key to sustaining success for research psychologists. It helps them stay passionate and look after their personal lives. Join Juhi Rathod as she talks about the journey to becoming a research psychologist.

Juhi Rathod’s experience

Juhi Rathod’s experience as a research psychologist is unique. She has gained valuable knowledge and expertise in the field. Her analytical skills allow her to understand complex information and draw meaningful conclusions. Juhi can communicate these findings through written reports, presentations, and discussions.

Additionally, Juhi has soft skills such as empathy, patience, and adaptability. These help her to connect with people of different backgrounds. Her involvement in clinical therapy training gives her a perspective on psychology that combines research and practical applications. During her doctoral degree and other professional development activities, Juhi has gained hands-on experience in working directly with mental health clients. This further enhances her understanding of the human mind.

Overall, Juhi’s experience as a research psychologist is valuable. To follow in her footsteps, it is important to stay current with advancements in research methods and the psychology field. This will ensure success in this rewarding career.

Research psychology is an intriguing field. To pursue this career, one needs to have a strong educational background and do extensive research. The article “How to Become a Research Psychologist” offers valuable advice.

Getting a higher education is important. The article suggests at least a bachelor’s degree in psychology , and even more advanced degrees. These degrees not only bring knowledge of psychology, but also teach research methods and statistical analysis.

In addition, gaining research experience is key. Internships or working with psychologists help budding researchers develop skills in data collection, analysis, and interpretation. This lets them contribute to the existing body of knowledge.

Continuous professional development is also necessary. Attending conferences, workshops, and seminars keeps researchers up to date. This ensures they remain expert in psychological research.

To sum up, becoming a successful research psychologist requires a strong educational background, hands-on research experience, and a commitment to learning and professional development . Following the advice in the article is a good start.

FAQs about How To Become A Research Psychologist

What are the time requirements to become a research psychologist.

The time requirements to become a research psychologist include earning a bachelor’s degree in psychology, which typically takes around four years, followed by a doctoral degree, which can take an additional four to six years to complete. After completing the doctoral degree, there may be additional post-doctoral placements or internships that range in duration.

What is the scientific method used in research psychology?

The scientific method is a systematic approach used in research psychology to gather data, formulate hypotheses, conduct experiments, analyze results, and draw conclusions. It involves observing phenomena, forming a research question, designing and conducting experiments, analyzing data using statistical methods, and interpreting the findings.

What is the career outlook for research psychologists compared to psychologists in general?

The career outlook for research psychologists is generally positive, with job growth expected in the coming years. The demand for research psychologists is driven by the need for scientific advancements and evidence-based practices. However, it is important to note that job opportunities and salaries can vary based on factors such as experience, sector of employment, and geographical location.

What type of clinical work is required for licensure as a research psychologist?

The clinical work required for licensure as a research psychologist typically involves supervised practice hours. These hours can be fulfilled through internships or fellowships that provide hands-on experience in conducting research, working with patients or study participants, and applying psychological principles in a clinical setting. The specific requirements for clinical work may vary depending on the state’s licensure board.

What are some common job titles for research psychologists in academic or industrial settings?

Some common job titles for research psychologists in academic or industrial settings include research psychologist, staff psychologist, clinical research psychologist, and medical psychologist. These professionals work in various research-focused roles, conducting studies, analyzing data, and contributing to the advancement of psychological knowledge in their respective fields.

What graduate coursework is important for aspiring research psychologists?

Graduate coursework for aspiring research psychologists often includes subjects such as experimental psychology, statistics, research methods, behavioral neuroscience, clinical psychology, and abnormal psychology. These courses provide students with a strong foundation in the scientific principles and research methodologies used in psychological research.

Research Psychology Further Reading and Resources

By exploring these resources, those interested in research psychology can gain a comprehensive understanding of the field’s methodologies, applications, and career prospects.

- The Association for Psychological Science – A leading international organization dedicated to advancing scientific psychology. Its website provides research, publications, and conferences related to the field.

- Research in Psychology: Methods and Design by C. James Goodwin – A textbook available for purchase online, it offers an in-depth look at research methods and ethical considerations in psychology.

- The Journal of Experimental Psychology – Published by the American Psychological Association, this peer-reviewed journal focuses on empirical research in experimental psychology.

- The Society for Research in Child Development – An organization promoting research, publications, and collaboration in the field of child development, which includes research psychology related to children.

- Psychological Research on the Net – A collection of online psychology studies across various subfields of psychology. It can be useful for those interested in current research trends.

We are psychologists, psychology professors, practicing MFCCs and psychology students providing career, degree and salary information for current and future psychologists.

Similar Posts

How to Become an Art Therapist?

How to Become an Environmental Psychologist

Become a Biopsychologist in 2024

How to Become a Traffic Psychologist 2024

How to Become a Mental Health Counselor

Become a Clinical Psychologist 2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.12(4); 2022

Original research

How the reduction of working hours could influence health outcomes: a systematic review of published studies, gianluca voglino.

1 Department of Public Health and Paediatric Sciences, University of Turin, Torino, Italy

Armando Savatteri

Maria rosaria gualano, dario catozzi, stefano rousset, edoardo boietti, fabrizio bert.

2 Health Direction, University Hospital City of Science and Health, Turin, Italy

Roberta Siliquini

Associated data.

bmjopen-2021-051131supp001.pdf

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as online supplemental information. Not applicable, this is a review.

The health effects of work-time arrangements have been largely studied for long working hours, whereas a lack of knowledge remains regarding the potential health impact of reduced work-time interventions. Therefore, we conducted this review in order to assess the relationships between work-time reduction and health outcomes.

Systematic review of published studies. Medline, PsycINFO, Embase and Web of Science databases were searched from January 2000 up to November 2019.

The primary outcome was the impact of reduced working time with retained salary on health effects, interventional and observational studies providing a quantitative analysis of any health-related outcome were included. Studies with qualitative research methods were excluded.

A total of 3876 published articles were identified and 7 studies were selected for the final analysis, all with a longitudinal interventional design. The sample size ranged from 63 participants to 580 workers, mostly from healthcare settings. Two studies assessed a work-time reduction to 6 hours per day; two studies evaluated a weekly work-time reduction of 25%; two studies evaluated simultaneously a reduced weekly work-time reduction proportionally to the amount of time worked and a 2.5 hours of physical activity programme per week instead of work time; one study assessed a reduced weekly work-time reduction from 39 to 30 hours per week. A positive relationship between reduced working hours and working life quality, sleep and stress was observed. It is unclear whether work time reduction determined an improvement in general health outcomes, such as self-perceived health and well-being.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that the reduction of working hours with retained salary could be an effective workplace intervention for the improvement of employees’ well-being, especially regarding stress and sleep. Further studies in different contexts are needed to better evaluate the impact of work-time reduction on other health outcomes.

Strengths and limitations of this study

- This is the first systematic review carried out in English to evaluate the impact of reduced working hours on both self-reported and measured health outcomes.

- All of the included studies had a longitudinal design, and in all studies except two the employment of extrapersonnel allowed to prevent a compensatory increase in workload, which may have limited the effectiveness of work-time reduction.

- The included studies were carried out in the Scandinavian setting, thus limiting the generalisability of the results in other contexts, different from a social, cultural and economic point of view.

- Three out of seven studies had a weak quality according to the authors, and most of the studies were carried out in the healthcare setting.

Introduction

In Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries, the average working week consists of 37 hours. 1 OECD data on annual average working hours show that, despite a declining trend in the amount of worked hours, many Countries still exceed the standard. 2 Working long hours is widely recognised as detrimental for employees’ health. Indeed, several studies investigating the health effects of working overtime reported concerning findings, including increased risk of stroke, coronary heart disease, anxiety, depression, sleep disorders and adverse pregnancy outcomes in women. 3–5 Furthermore, a systematic assessment of evidence in literature with meta-analyses conducted by Rivera et al found moderate-grade evidence linking long work-hours with stroke and low-grade evidence on the association between long work-hours with coronary disease, depression and pregnancy complications, including low birthweight babies and preterm delivery. 6 Long working hours have also been associated with reduced levels of work–life balance and increased work–family conflict. 7

Conversely, the effects of reduced work-hours (RWH) have not been extensively examined as for long work-hours so far. Indeed, several experiments of reducing working time have been conducted throughout the years, both in the public and private sector. One of the most notable examples was the adoption of the ‘35-hour workweek’ between 1998 and 2000 by the French Government, which allowed the reduction of weekly working hours from 39 to 35, with the aim of fighting the high unemployment rates. However, aside from two surveys examining employees’ satisfaction with modified work-hours and their work-family conflict, no other impacts on health and well-being have been evaluated. 8 9 The authors argue that the French 35-hour law increased overall dissatisfaction with modified work hours among employees, mainly because it did not take into account the heterogeneity of work organisation. It appears that employees increased workload to maintain high productivity. Indeed, reducing working time without employing extrapersonnel may compromise the fine balance between job demand and resources, which in turn would undermine employees’ wellbeing. 10 Further interventions have been carried out on a company level. In Germany, Volkswagen reduced the working week from 36 to 28.8 hours 11 and more recently, Microsoft Japan tested a 4 days work week. 12 Similarly, Perpetual Guardian, a New Zealand firm operating in the management of trusts, wills and estates, ran a 4-day work week trial for all its 240 employees. 13 Although companies reported successful results, they did not take into consideration the potential health impact of these experiences.

Besides, there are few studies even in scientific literature that investigate the role of RWH on workers’ health. To our knowledge, only one literature review was conducted in 2005 and authors concluded that no relevant effects on health were observed. 14 However, the review was published in Swedish, hence it may represent an issue due to language barriers. Furthermore, the studies included in their work were mostly reports from Swedish ministerial committees and critical reviews on work time arrangements. Indeed, in the studies published before 2000 authors were primarily interested in the economic consequences of reducing work-hours, exploring the feasibility of the project, and little attention was paid to the effects of work-time reduction on the health of employees. Since 2000, several interventional studies have been published. Therefore, we decided to conduct a review of the literature examining studies focusing on the relationship between RWH and health effects, published since 2000, in which employees retained their salary and proportionally decreased their work time and workload.

Search strategy

Following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses checklist, we carried out a literature search for articles published in Medline, PsycInfo, Embase and Web of Science databases from January 2000 up to November 2019. Search terms included terms like ‘work’, ‘health’, ‘well-being’, ‘mental-health’, ‘worktime reduction’, ‘reduced work hours’. Full search strings for each database are provided in online supplemental file 1 . First, duplicates were excluded. Next, AS, DC, EB and GV independently screened retrieved sources by title and abstract following inclusion criteria. The same authors, always in an independent fashion, performed a full text review. Finally, consensus was reached through discussion about uncertain cases between all reviewers. Authors chose Rayyan QCRI as a tool for selecting and extracting relevant records. 15

Supplementary data

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

We decided to include primary sources in any form, both interventional and observational studies, provided that quantitative analysis of any health-related outcome were performed. Hence, studies with qualitative research methods were excluded because we were interested on the effects of the interventions in terms of quantitatively measured outcomes. Articles had to investigate the association between reduced working time with retained salary and health effects, without excluding beforehand any category of workers. No salary reduction was considered crucial in order to avoid a selection bias possibly leading to exclude low-income workers. Another inclusion criterion was the replacement of working activity with any workplace-based intervention, provided that the amount of work hours was effectively reduced. Conversely, studies specifically focused on work-time reduction policies regarding activities with excessively long working hours, such as medical residency, were not consistent with the concept of RWH and retained salary and were therefore excluded from our work. No language restriction was set. Due to the heterogeneity in the outcomes evaluated by the studies selected, a meta-analysis of data could not be conducted. Data and information regarding study design, country, participant characteristics, observation period, intervention description, outcomes measured and results were extracted and synthesised in a systematic literature review.

Quality assessment

The quality of the included studies was assessed using the ‘Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies’ developed by the Effective Public Health Practice Project. 16 This quality appraisal tool provides a standardised means to assess study quality and develop recommendations for study findings considering eight components of study methodology: selection bias, study design, presence of confounders, blinding of participants and outcome assessors, validity and reliability of data collection methods and study dropouts and withdrawals. The overall quality of each study is then expressed as weak, moderate or strong. Previous evaluation of the tool has shown it to be valid and reliable. 17 Two reviewers, namely AS and SR, independently performed quality assessment. Discrepancies between the reviewers, such as differences in interpretation of criteria and studies, were resolved by discussion in order to reach consensus.

Patient and public involvement

No patient involved. Results will be disseminated throughout conferences and social media in order to enrich public debate on health outcomes of working hours rearrangements.

As results of the bibliographic search, a total of 3876 published articles were identified ( figure 1 ).

Systematic review: selection process. From: Moher D, et al . 31

Duplicates were excluded and remaining 2456 records were reviewed. A full-text review was conducted on 40 articles. Finally, after evaluating the inclusion criteria, seven articles were selected (one article was originally added by citation chasing). In total seven articles, with a longitudinal interventional design, were included in the final analysis. 18–24 A brief summary of included articles is provided in table 1 .

Characteristics of the studies included in systematic review

| Author | Study Design | Country and participants | Observation period | Intervention description | Outcome (measures) | Results | Quality assessment rating |

| Åkerstedt , 2001 | Longitudinal intervention study | Sweden, N=63, full-time workers in healthcare service. | 36 months | Intervention group (N=41): reduced WWH from 39 hrs/week to 30 hrs/week. Control group (N=22): unchanged working time. | Subjective sleep quality (SSQ), mental fatigue and heart/respiratory symptoms, time for social activity, time for family and friends improved significantly more in the experimental group than in the control group. No significant effects for sickness absence or self-rated health. | Weak | |

| Wergeland , 2003 | Longitudinal intervention study | Norway and Sweden, N=403. Workers in nursing homes, home care services and kindergartens | 12–22 months | Intervention group: reduced DWH to 6 hrs/day. Reference group: unchanged working time. | A significant interaction was found for neck-shoulder pain and for exhaustion after work in the intervention group. No significant effects were observed in the reference group. | Weak | |

| von Thiele Schwarz , 2008 | Longitudinal intervention study | Sweden, N=177 employees from six workplaces at public dental healthcare organisation | 12 months | PE group: 2.5 hrs/week of physical activity instead of work time. Reduced work hours group: reduced WWH proportionally to the amount of time worked. Reference group: unchanged working time. | Physical activity level increased in all three groups but significantly more in PE group. Glucose levels and upperextremity disorders were found to be significantly decreased in the exercise group, while a significant increase in HDL and waist-to-hip ratio was found among those working reduced hours. Participants working reduced hours also had significantly increased total cholesterol, while no changes in LDL-to-HDL ratio were recorded. | Strong | |

| von Thiele Schwarz , 2011 | Longitudinal intervention study | Sweden, N=177 employees from six workplaces at a public dental healthcare organisation | 12 months | PE group: 2.5 hrs/week of physical activity instead of work time. Reduced work hours group: reduced WWH proportionally to the amount of time worked. Reference group: unchanged working time. | Physical activity was significantly associated with an increase in self-rated productivity in terms of increased quantity of work and work-ability and decreased frequency and number of days of sickness absence. No effect was found in the work hours reduction group. In all three groups there was an increase in the number of treated patients per therapist, significantly greater in the reduced work hours group. | Strong | |

| Barck-Holst , 2017 | Longitudinal quasi-experimental trial | Sweden, N=204 A total of 125 participants were deemed as per protocol | 18 months | Intervention group: reduced work hours by 25%. Reference group: unchanged working time. | The intervention group significantly improved restorative sleep, stress, memory difficulties, negative emotion, sleepiness, fatigue and exhaustion on both work days and weekends. Improved demands, instrumental manager support and work intrusion on private life were observed to be significantly higher in the intervention group. | Moderate | |

| Lorentzon 2017 | Longitudinal intervention study | Sweden, N=124, nurses working in a centre for the elderly | 23 months | Intervention group: work-time reduction to 6 hours/day. Reference group: unchanged working time. | Good perceived health and alertness level, satisfactory level of perceived fatigue. Energy left at home, feeling calm, satisfactory levels of stress, average sleep time increased in intervention group. General symptoms, sleep and musculoskeletal symptoms improved in the intervention group, and dropped in the control group. Collaboration and personal development improved; improved sense of collaboration between nurses. Sick leave increased in the intervention group. No inferential statistics provided. | Weak | |

| Schiller , 2017 | Longitudinal controlled intervention study | Sweden, N=580, workers from 33 workplaces in the public sector | 18 months | Intervention group: reduced WWH by 25%. Reference group: unchanged working time. | On workdays, the intervention group displayed significantly improved SSQ, decreased sleepiness and perceived stress, less feelings of worries and stress at bedtime when work hours were reduced. Also, a significant 23 min extension of sleep duration was detected. The intervention showed similar positive effects on days off, except for sleep duration. | Strong |

HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; PE, physical exercise; WWH, weekly worked hours.