- All Articles

- Books & Reviews

- Anthologies

- Audio Content

- Author Directory

- This Day in History

- War in Ukraine

- Israeli-Palestinian Conflict

- Artificial Intelligence

- Climate Change

- Biden Administration

- Geopolitics

- Benjamin Netanyahu

- Vladimir Putin

- Volodymyr Zelensky

- Nationalism

- Authoritarianism

- Propaganda & Disinformation

- West Africa

- North Korea

- Middle East

- United States

- View All Regions

Article Types

- Capsule Reviews

- Review Essays

- Ask the Experts

- Reading Lists

- Newsletters

- Customer Service

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Subscriber Resources

- Group Subscriptions

- Gift a Subscription

China’s Growing Water Crisis

A chinese drought would be a global catastrophe, by gabriel collins and gopal reddy.

China is on the brink of a water catastrophe. A multiyear drought could push the country into an outright water crisis. Such an outcome would not only have a significant effect on China’s grain and electricity production; it could also induce global food and industrial materials shortages on a far greater scale than those wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine. Given the country’s overriding importance to the global economy, potential water-driven disruptions beginning in China would rapidly reverberate through food, energy, and materials markets around the world and create economic and political turbulence for years to come.

Unlike other commodities, water does not have any viable substitutes. It is essential for growing food, generating energy, and sustaining humanity. For China, water has also been crucial to the country’s rapid development: currently, China consumes ten billion barrels of water per day—about 700 times its daily oil consumption. Four decades of explosive economic growth, combined with food security policies that aim at national self-sufficiency, have pushed northern China’s water system beyond a sustainable level, and they threaten to do the same in parts of southern China as well. As of 2020, the per capita available water supply around the North China Plain was 253 cubic meters or nearly 50 percent below the UN definition of acute water scarcity. Beijing, Shanghai, Tianjin, and other major cities are at similar—or lower—levels. So scarce are Hong Kong’s freshwater resources that the city has for decades used seawater to flush toilets. For reference, as of 2019, even severely water-stressed Egypt had per capita freshwater resources of 570 cubic meters per capita, and it does not have to support a large manufacturing base like China’s.

Moreover, a significant portion of China’s water supply is not fit for human consumption. A 2018 analysis of surface water by China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment found that although the quality had improved from previous years, 19 percent was still classified as unfit for human consumption and roughly seven percent was unfit for any use at all. The quality of groundwater—which is critical for ensuring water supplies during drought—was worse, with approximately 30 percent being deemed unfit for human consumption and 16 percent deemed unfit for any use. China may be able to use impaired water resources in the future, but only with major additional investment in treatment infrastructure and a significant increase in electricity use to power water treatment processes. Meanwhile, farm and industrial chemicals continue to contaminate the country’s groundwater, setting the stage for potentially decades of additional water supply impairments. Data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization indicate that China uses nearly two and a half times as much fertilizer and four times as much pesticide as the United States does despite having 25 percent less arable land.

For decades, Beijing has generally chosen to conceal the full extent of China’s environmental problems to limit potential public backlash and to avoid questions about the competence and capacity of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). This lack of transparency suggests that an escalation to acute water distress could be far closer than most outside observers realize— increasing the chances that the world will be ill prepared for such a calamity.

NORTHERN CRISIS

The overpumping of aquifers under the Northern China Plain is a core driver of China’s looming water crisis. According to data from NASA GRACE satellites, the North China Plain’s groundwater reserves are even more overdrawn than those of the Ogallala Aquifer under the Great Plains of the United States, one of the world’s most imperiled critical agricultural water sources. These data further suggest that the most populous portion of China north of the Yangtze River—an area from eastern Sichuan to southern Jilin that is home to more than a billion people—has for much of the past 15 years seen steady declines in the amount of water in the region’s lakes, rivers, and aquifers.

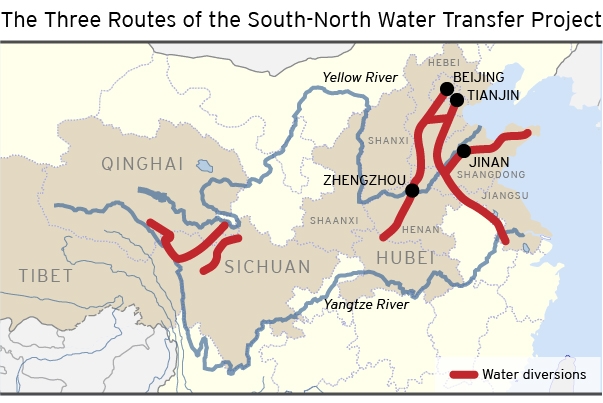

In parts of North China, groundwater levels have declined by a meter per year, causing naturally occurring underground water storage aquifers to collapse, which has triggered land subsidence and compromised the aquifers’ potential for future recharge. Recognizing the urgency of the problem, China’s government in 2003 launched the $60 billion South-to-North Water Transfer Project, which draws water from tributaries of the Yangtze River to replenish the dry north. To boost rainfall (and sometimes engineer better weather, for example, for Olympics ceremonies and party anniversary events), China has also deployed aircraft and rockets to lace clouds with silver iodide or liquid nitrogen, a process known as cloud seeding. It has also relocated heavy industry away from the most water-stressed regions and is investing massively in water management infrastructure, with Vice Minister of Water Resources Wei Shanzhong estimating in April 2022 that annual investment in water-related projects could hit $100 billion annually.

Still, these efforts may be insufficient to forestall a crisis. Despite highly innovative programs to improve water availability, some scholars estimate that water supply could fall short of demand by 25 percent by 2030—a situation that would by definition force major adjustments in society. Experiences to date on the North China Plain enhance concern and illustrate the scale of additional needed hydraulic intervention. Despite nearly a decade of importing Yangtze valley water supplies to high-stress areas such as Beijing, large-scale depletion of stored groundwater continues in other nearby areas, such as Hebei and Tianjin.

LESS WATER, LESS FOOD

China’s leadership is keenly aware that famines precipitated by drought helped topple at least five of China’s 17 dynasties. Thus, for centuries, the country’s leaders have emphasized maximizing grain production to ensure food security, a policy that the CCP’s development agenda has continued. The policy has become especially important since the early years of the twenty-first century as strategic competition between China and the United States intensifies . For the past 20 years, Chinese government policy has offered incentives to farmers to maximize production of corn, rice, and wheat to achieve “self-sufficiency” levels (production levels determined as a percentage of consumption) that generally exceed 90 percent. Groundwater extraction played an outsize role in this achievement and transformed the dry North China Plain into the country’s breadbasket. Farms on the North China Plain produce approximately 60 percent of China’s wheat, 45 percent of its corn, 35 percent of its cotton, and 64 percent of its peanuts. The region’s production of more than 80 million tons of wheat is on par with Russia’s annual output, and its nearly 125 million tons of corn is almost three times Ukraine’s prewar production.

But to sustain these harvests, farms and cities are pumping water far faster than nature can replenish it. Satellite data suggest that each year between 2003 and 2010, North China lost an amount of groundwater equal to more than twice what Beijing consumes annually. As groundwater levels fall, many farmers are struggling to find new sources. Some are digging larger, deeper wells, often at great cost; but continual overdraws may render water physically inaccessible regardless of pumpers’ willingness to spend on deeper wells and new pumping technology.

If the North China Plain were to suffer a 33 percent crop loss because of water insufficiency, China would potentially need to compensate by importing approximately 20 percent of the world’s internationally traded corn and 13 percent of its traded wheat. Such a scenario is not out of the realm of possibility. Consider that a drought in early 2022 slashed Argentina’s expected corn crop by 33 percent. Further, if a drought were to curtail rice yields in southern China or Heilongjiang (in China’s fertile Northeast), that could create even larger market shocks given China’s disproportionate share of rice consumption. All three major staple grains are critical for hundreds of millions of lower-income consumers worldwide, with corn as a staple in Latin America, wheat vital in the Middle East and North Africa, and rice essential across Asia.

Although China has stockpiled the world’s largest grain reserves, the country is not immune to a multiyear yield shortfall. This would likely force China’s food traders, including large state-owned enterprises such as COFCO and Sinograin, into global markets on an emergency basis to secure additional supplies. This in turn could trigger food price spikes in high-income countries, while rendering key food items economically inaccessible to hundreds of millions of people in poorer countries. The impacts of this water-driven food shortage could be far worse than the food-related unrest that swept across lower- and middle-income countries in 2007 and 2008 and would drive migration and exacerbate political polarization already present in Europe and the United States.

THE POWER PROBLEM

China’s water problems go well beyond its agricultural sector. China’s energy sector—the world’s largest—also faces significant water risks. Despite major investments in renewable energy, nearly 90 percent of China’s electricity supply still requires extensive water resources, particularly hydro, coal, and even nuclear generation, which needs large and steady water supplies for steam condensers and to cool reactor cores and used fuel rods. (It is worth noting that all Chinese power reactors currently operating or under active construction are sited near the coast and can use seawater for cooling.)

Managing the cascading effects of a shortfall from any given power source is daunting. If China lost 15 percent of its hydropower production in a year because of low water levels behind dams—a plausible scenario based on real-world experiences in Brazil—it would have to increase electricity output by an amount equal to what Egypt generates in a year. In China’s energy system, only coal-fired plants could potentially boost output by hundreds of terawatt-hours on short notice.

Unfortunately, the coal mining and preparation process is often highly water intensive, and if China were compelled to ramp up coal production, it would further strain local groundwater supplies. Moreover, while seawater can be used for cooling in coastal regions, many of China’s coal-fired plants are located inland and rely on rivers, lakes, or groundwater. Power plants could be forced to curtail operations if cooling water runs short or if farmers and cities are given priority access to remaining supplies. Our analysis of approximately 2,000 utility-scale (300 megawatts or larger capacity) Chinese coal-fired power generation units and their known or likely modes of cooling suggests that about 500 gigawatts of capacity —more than the combined coal power capacity of India and the United States—face elevated risks from a prolonged drought.

China’s energy sector—the world’s largest—faces significant water risks.

Reduced river-borne coal transport capacity could also limit electricity production. In the United States’ Ohio and Mississippi River systems, losing even an inch of river level can reduce a barge convoy’s carrying capacity by hundreds of tons. China’s water systems likely suffer from similar limitations. Multiplied over a region with hundreds of coal plants and thousands of waterway miles, lower water levels could rapidly strain coal availability. If plants along some of these waterways needed to increase their electricity output to compensate for hydro output losses elsewhere, there is a real risk that coal could not reach where it was needed in time, and in sufficient quantity, to maintain stable electricity supplies.

China’s power shortfalls would directly affect global supply chains, as industrial facilities account for over 65 percent of electricity use in China. To minimize the immediate human impact of broad, uncontrolled blackouts, party officials would likely have to shut down industrial facilities to ease the grid load—as they did during power shortfalls in 2021.

Blackouts by decree would disrupt a number of key materials supplies. China is by far the world’s largest producer of aluminum, ferro-silicon, lead, manganese, magnesium, zinc, most rare earth metals, and many other specialty metals and materials. Power outages in even a single region can move global markets—as European carmakers discovered in late 2021 when power shortages curtailed magnesium smelter operations in Shaanxi Province, responsible for about 50 percent of global output. As magnesium inventories plummeted, prices spiked to seven times their level at the beginning of the year and European industrial consumers called for government action to ensure supplies.

Sustained water and electricity problems in China could also impede the global transition to clean energy. China produces an overwhelming portion of the polysilicon used for solar cells and the rare earth metals used in wind turbines around the world. The country also dominates raw materials refining and cell production for electric vehicle batteries.

RUNNING OUT OF OPTIONS

As former British diplomat and China expert Charlie Parton noted in 2018: “China can print money, but it cannot print water.” China’s potential way out of this predicament is bounded by harsh economic, physical, and political realities. Perhaps the most dramatic and comprehensive reform would be to encourage efficiency by making water more expensive. But this will not be easy, as China’s input-intensive heavy industrial base and its rural farmers are accustomed to cheap water. Although agriculture accounts for over 60 percent of China’s water consumption, the vast majority of farms are under three acres. Small and midsize farms operating on thin margins may not be able to afford water-saving equipment such as drip irrigation. Moreover, consolidation of farm holdings is politically sensitive and would likely still prove insufficient; the default response of northern Chinese farmers faced with declining water tables has been to simply dig deeper wells and install more powerful pumps—responses that would only accelerate a crisis.

The government could also work to shift consumer habits through persuasion. As far back as 2016, Beijing was encouraging citizens to switch from eating water-intensive rice, the country’s traditional staple, to potatoes, which require less water to produce. But officials have done little to enforce such campaigns, which belie the CCP’s preferred narrative of economic progress and increasing living standards reflected through rising consumption of goods and services. It is also true that it is easier for the government to prevent citizens from doing things it deems undesirable than to compel them to do things it wants, such as having more children , pursuing consumerist ambitions, and eating more water-efficient potatoes.

China can print money, but it cannot print water.

China’s central and local leaders may gravitate toward supply-side solutions, but these may be insufficient to tackle the country’s daunting water challenge. The still functioning 2,200-year-old Dujiangyan Irrigation Works in Sichuan is a testament to China’s long history as a global hydraulic engineering superpower and suggests a likely focus on supply-side measures to address structural water shortages. The South-to-North Water Diversion Project aims to transfer up to 21 billion cubic meters of water annually from the Yangtze River Basin by 2030 and is projected to ultimately move over twice that volume. Yet this project does not come close to resolving the supply gap in northern China, as evidenced by recent announced plans to divert water from the Three Gorges Dam in Hubei province to Beijing. Likewise, shifting water from farther afield, such as the Tibetan Plateau or Lake Baikal in Russia , appears to be geologically difficult, prohibitively costly, and politically infeasible.

Desalination is another potential supply-side solution. But scaling desalination up to the level needed to close China’s water supply gap would be a gargantuan task. The roughly 20,000 desalination plants in operation worldwide can produce about 36.5 billion cubic meters of water per year. This amounts to merely six percent of China’s annual water consumption, highlighting the difficulty of relying on desalination to close China’s estimated 25 percent water supply gap. Moreover, desalination is highly energy intensive—at a time when China’s electric grid is already straining to maintain output. The high energy intensity of desalination also means that desalinated water would be far more expensive than other supplies, potentially by a factor of 10. Party officials would then face a choice of either subsidizing water rates or accepting major (and likely, politically disruptive) adjustments to decades-old industrial and consumer expectations founded on access to low-cost water.

China-centric supply chains took decades to build and cannot be easily or quickly moved elsewhere. This is all the more reason for governments to act now to prepare key global markets for an extended water crisis in China. Nor is past experience much of a guide: when China suffered widespread multiyear droughts in 1876 and 1928, it was not the “factory floor of the world.” Today’s global supply chains are woefully unprepared for a Chinese drought that could disrupt grain trade patterns and key industrial materials production across multiple continents. As China continues overexploiting groundwater amid intensified weather volatility, it moves closer each year to a catastrophic water event, and forceful steps must be taken while there is still time.

You are reading a free article.

Subscribe to foreign affairs to get unlimited access..

- Paywall-free reading of new articles and over a century of archives

- Unlock access to iOS/Android apps to save editions for offline reading

- Six issues a year in print and online, plus audio articles

- GABRIEL COLLINS is the Baker Botts Fellow in Energy and Environmental Regulatory Affairs at Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy and a Senior Visiting Research Fellow at the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies.

- GOPAL REDDY is the founder of Ready for Climate, a research platform focused on the national security and economic risks stemming from climate change. He was also the founder of Chakra Capital Partners.

- More By Gabriel Collins

- More By Gopal Reddy

Most-Read Articles

The undoing of israel.

The Dark Futures That Await After the War in Gaza

Ilan Z. Baron and Ilai Z. Saltzman

How everything became national security.

And National Security Became Everything

Daniel W. Drezner

China’s real economic crisis.

Why Beijing Won’t Give Up on a Failing Model

Zongyuan Zoe Liu

The forgotten history of the financial crisis.

What the World Should Have Learned in 2008

Recommended Articles

The global food crisis shouldn’t have come as a surprise.

How to Finally Fix the Broken System for Alleviating Hunger

Christopher B. Barrett

How to solve the global water crisis.

The Real Challenges Are Not Technical, but Political

Scott Moore

- Economics & Finance

- Foreign Policy

- Domestic Policy

- Health & Science

- All Publications

How China’s Water Challenges Could Lead to a Global Food and Supply Chain Crisis

Table of Contents

Gabriel collins, gopal reddy, share this publication.

- Print This Publication

Gabriel Collins and Gopal Reddy, "How China’s Water Challenges Could Lead to a Global Food and Supply Chain Crisis" (Houston: Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, November 14, 2022), https://doi.org/10.25613/526F-MR68 .

Note: This report is based on Gabriel Collins and Gopal Reddy’s “China’s Growing Water Crisis,” published in Foreign Affairs on August 23, 2022.

Following a record-breaking drought this summer, China is on the brink of a water catastrophe that could have devastating consequences for global food security, energy markets and supply chains. The 2022 drought, which mainly impacted China’s Sichuan province, offered an uncomfortable preview of what the future could bring if water supplies continue to run dry: Low reservoir levels slashed hydroelectricity output, which in turn forced power rationing to major industrial consumers such as metals and battery producers and electronics assemblers. [1] A prolonged multi-year drought would have exponentially larger impacts across global grain, energy and industrial materials markets due to water-driven and electricity-caused supply chain disruptions within China. Billions of people worldwide would be affected in ways worse and potentially longer-lasting than the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing war in Ukraine.

This essay aims to bring the criticality of China’s water challenge onto policymaker radar screens around the world. Policy discussions of China-driven risks so far have mostly centered on the nation’s slowing growth, real estate bubbles, high debt and potential military conflict over Taiwan. These factors are significant, but China’s incipient water crisis, which receives far less attention from policymakers, could plausibly overwhelm such issues. An unsettling question emerges: What happens if China suffers a multi-year water crisis that significantly reduces its grain production and electricity supplies?

China Is Already Seriously Water-Stressed

Aside from its use for basic human needs, water is an often-unseen input (for example, it takes roughly 500 gallons of water to produce a single hamburger [2] ), and its ubiquity and underpricing often cause consumers and policymakers to overlook its importance. The scale of human water consumption is massive compared to all other commodities. For reference, China’s economy consumes 14 million barrels per day of crude oil, while its daily average water consumption is 10 billion barrels, a quantity 700 times larger. Unlike many energy commodities, water also does not have viable substitutes. It is especially critical for growing food and generating energy, two of humanity’s most life-critical activities.

Beijing has the dubious distinction of being the capital of the world’s second-largest economy, while having per capita water supplies that have fallen to a level on par with those of cities near Chile’s Atacama Desert — the driest place on Earth. [3] Under UNICEF’s standards, [4] Beijing’s per capita water availability of approximately 120 cubic meters would qualify as “extreme water scarcity.” Water availability in Beijing was nearly 10 times higher when the People’s Republic was founded in 1949; Beijing’s water challenges reflect China’s plight more broadly.

Four decades of explosive economic growth, combined with food security policies that emphasize self-sufficiency, have pushed northern China’s water system beyond sustainability and threaten to do so in parts of southern China as well. As of 2013, average water resource availability in northern China (the 12 provinces north of the Yangtze River) was 300 cubic meters (m3), or 40% below the UN definition of acute water scarcity. Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, Hong Kong and many other major cities suffer from freshwater levels well below the UN’s definition of acute scarcity. For reference, Egypt had per capita water resources of 570 m3 as of 2019 and does not have a large manufacturing base to support.

Independent data on water availability in China are sparse, but another decade of rapid economic growth and shifting precipitation patterns have likely further stressed water supplies throughout the country. Official water data from the PRC government should also be assumed to understate the magnitude and urgency of water problems. For decades, Beijing has generally chosen to conceal the full extent of its environmental problems and has especially strong incentives to do so for something as systemically important as water supply.

Empirical data show the strain. NASA GRACE satellites that measure gravitational anomalies now suggest that northern China has some of the world’s most overdrawn aquifers. Monthly data from the same satellite initiative further show that the most populous portion of China north of the Yangtze River — a band from western Sichuan to southern Jilin — has seen steady declines in water storage for much of the past 15 years.

Figure 1 — The North China Plain (NCP) — China’s Breadbasket — Often Exceeds Water Stress of the American Ogallala Aquifer Region, Itself in Serious Crisis Change in Water Equivalent Thickness, Centimeters. 0=Neutral

Figure 2 — Approximate Geographical Extent of “North China” and North China Plain Zones GRACE Data Come From

Groundwater levels are falling by a meter or more annually in parts of northern China, causing subsidence and locking in intensified water stress as underground pore spaces collapse and compromise the aquifer’s potential for future recharge. Large-scale depletion of groundwater resources across China — potentially to the tune of 60 billion cubic meters annually, according to one team of local and foreign scholars [5] — continues, despite attempts to shift water resources to high-stress areas like the North China Plain.

Moreover, official data — which again likely understate the true extent of the problem — indicate that close to a fifth of China’s water resources are polluted to the point of being unusable. A 2018 analysis of surface water by China’s Ministry of Ecology and Environment [6] found that although the quality had improved from previous years, 19% was still classified as unfit for human consumption, and roughly 7% was unfit for any use at all. The quality of groundwater — which is critical for ensuring water supplies during drought — was worse, with approximately 30% deemed unfit for human consumption and 16% deemed unfit for any use. China may be able to use impaired water resources in the future, but only with major additional investment in treatment infrastructure and a significant increase in electricity use to power water treatment processes.

Groundwater pollution is also likely to worsen as farm (and other) chemicals continue to percolate downward into shallow, and eventually, deep aquifers, a decades-long process. Data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization show just how chemical-intensive China’s farming model is, currently using nearly 2.5 times more fertilizer and four times as many pesticides as the United States, despite having 30% less arable land. [7]

China’s Water Geography Problem

Much of China’s water problem arises from the spatial distribution of its water resources and that its meteorology poorly matches the locations of agricultural activity and population. Many areas south of the Yangtze River receive annual precipitation substantially greater than Munich or New York City. Meanwhile, in a good year, much of the California-sized North China Plain gets only about as much rain as Sacramento or San Francisco — yet it serves as China’s breadbasket and is one of the most densely-populated regions on Earth. Mao Zedong acknowledged these realities 70 years ago when the pressure was palpable but less acute than today, noting, “The South has plenty of water and the North lacks it, so, if possible, why not borrow some?” [8]

China’s government has taken drastic steps along such lines to try to increase local water supplies where possible. This includes the $60 billion South-to-North Water Diversion Project, widescale atmospheric interventions to boost rainfall and the relocation of heavy industry away from water-stressed regions. Current plans call for a further $500 billion of investment in water infrastructure. [9]

Despite its efforts to increase water availability, China still faces a water supply gap that some domestic scholars estimate could reach 25% by 2030. [10] There are many unknown variables in this equation. These include hydrological factors like accelerated groundwater depletion, possible changes to precipitation due to climate change and the potential for glacially-fed rivers to see a sudden drop in flows. Water transfer schemes also offer a potential solution. Yet erratic precipitation and frequent droughts in southern China suggest that simply shifting water from south to north will not be a viable long-term solution. Southern cities that have historically received abundant rainfall — like Guangzhou and Hong Kong — have, in recent years, faced water-use restrictions amid serious drought conditions. [11]

Other countries have proven it is possible to manage demand and incentivize efficiency by raising the cost of water. But this will be a tough sell in China given that the global competitiveness of so much of its industrial model is predicated upon purposely depressed input costs, including both energy (coal) and water.

It is likely that Beijing has harvested the lowest-hanging fruit in terms of increasing water efficiency. For instance, World Bank data show that the share of water used by agriculture in China declined from 88% in 1982 to 63% in 2007 — a proportion that has since remained stable. [12] The plateau suggests that further water efficiency gains in the farming sector would require more dramatic measures, such as significant increases in water prices. Typically, such frontier breakthrough events come only when crisis forces policymakers to act, meaning that disruptive shockwaves would already, by definition, have been injected into key local and global markets. Such a water crisis in China and its aftershocks could reverberate through global markets for years, with food markets among the most directly and intensely impacted.

China’s High-Stakes Food-Energy-Water Nexus

At the heart of China’s (and all other) modern economic systems is the food-energy-water nexus — the three-legged stool of tradeoffs upon which civilization rests. A given molecule of water can nourish a wheat or rice stalk, turn a hydroelectric turbine, cool a thermal power plant’s condenser, or slake a human being’s thirst. But it cannot do more than one of these simultaneously, meaning that one leg of the nexus generally competes with the others.

As a global rule of thumb, producing two tonnes of wheat requires enough water [13] to fill an Olympic-size swimming pool. [14] Electricity generation, especially that from coal, also requires massive volumes of water. The annual electricity use of a single urban Chinese household — about 2 megawatt-hours — could require anywhere from 1,200 to as much as 120,000 gallons of water, depending on power plant cooling methodology. Agriculture accounts for approximately 65% of China’s water consumption with power generation and manufacturing consuming another 22%; household consumption accounts for most of the remainder. [15] Growth reinforces growth, and rapid economic expansion over the past three decades has had a commensurate impact on water consumption.

China’s leadership is keenly aware that famines precipitated by drought helped topple at least five of China’s 17 dynasties. [16] Chinese leaderships have thus for centuries emphasized maximizing domestic grain production to ensure food security. The policy has become especially important for the last two generations of Communist Party leaders as strategic competition between China and the United States intensifies. For the past 20 years, Chinese farmers have been able to maintain “self-sufficiency” levels (defined as total consumption divided by domestic production) of 80% or higher for corn, rice and wheat — three of the four staple grains.

Intensive water usage played an outsized role in this achievement. Data from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) show that between 1985 and 2019, China’s stock of farmable land actually shrank slightly, while the portion of those lands equipped for irrigation rose from 41% to 63%. [17] Better technology and farming practices, combined with increasingly intensive use of key inputs — namely, fertilizers and pesticides — drove some of the gains, but their contributions were heavily contingent on increased local availability of irrigation water. Other grain superpowers such as Brazil, Canada, Russia and the U.S. are far less dependent on irrigation (with 17% of farmable land equipped for irrigation in the U.S., 15% in Canada, and far less in Brazil and Russia). [18] These nations expanded production by both boosting the cultivable land base and better applying inputs. By contrast, China’s calculus made the water variable disproportionally important — evidenced by the fact that much of the growth in land equipped for irrigation took place in the last 20 years. Indeed, China’s overall freshwater withdrawals rose by 28% between 1982 and 2017, according to the FAO. Groundwater use in particular has increased rapidly, growing by 66% during that time.

In northern China, the likely ground zero for the first impacts of a water crisis, significant use of groundwater commenced in the 1950s. Users have since drilled more than 7.5 million wells that now support crops on an area nearly the size of Oklahoma. [19] The benefits to crop production have been spectacular; farms on the North China Plain produce approximately 60% of China’s wheat, 45% of its corn, 35% of its cotton and 64% of its peanuts. In contemporary tonnage terms, this means annual wheat production of more than 80 million tonnes (more than all of Russia’s annual production) and corn output of nearly 125 million tonnes (three times Ukraine’s annual production).

The millions of wells now draining the North China Plain Aquifer and other subsurface water-bearing strata are proving unsustainable. Across the North China Plain, the water table now declines approximately a meter per year as farms and cities compete to pump water far faster than nature can replenish it. [20] Data from NASA satellites that measure anomalies in Earth’s gravity field suggest that between 2003 and 2010, North China lost an amount of groundwater equal to about 143 million barrels per day each year — 10 times China’s present daily oil demand.

Once groundwater resources are sufficiently overdrawn, water can become economically inaccessible to agricultural users if the cost of obtaining it through larger, deeper wells exceeds the market value of crops produced. [21] The transition to economic inaccessibility can happen far before reservoirs are physically “pumped out.” In practice, this means the transition from “stressed but sufficient” water supplies to an acute lack of supply can happen very quickly, particularly for the critical agricultural sector.

A Sustained China Water Crisis Would Spark a Global Food Crisis

If the North China Plain suffered a 33% crop loss due to drought, China would potentially need to import approximately 20% of “tradable” corn production worldwide and more than 13% of global tradable wheat. [22] If losing a third of a crop seems like a pessimistic scenario, consider that in spring 2022, drought slashed Argentina’s expected corn crop by precisely that proportion. [23] A drought that curtailed rice yields in southern China would create even larger market shocks due to China’s high share of global rice consumption. All three major staple grains are critical for a mass of lower-income consumers worldwide that collectively number in the billions, with corn as a staple in Latin America, wheat vital in the Middle East and North Africa, and rice essential across Asia.

China has compensated for this potential weakness by building far and away the largest grain stockpile in the world. [24] For the staple “starch” grains — corn, rice and wheat — China has consistently stored close to a year of supplies in recent years. It has also held significantly higher soybean stocks, albeit with fewer months of forward demand coverage than are held for the three grains directly consumed by humans. Yet any event that lasted for more than a single growing season would substantially increase the probability of Chinese entities taking aggressive action to secure additional supplies — which would likely trigger price spikes that inflate food costs in the OECD world and potentially render key food items economically inaccessible to hundreds of millions of people in non-OECD countries.

A China Water Crisis Would Also Likely Spawn an Electricity Crisis

Despite significant investment in renewable energy, China still generates approximately 60% of its electricity from coal and nearly 20% from hydroelectric sources. Coal-fired power plants require substantial amounts of water for cooling, while coal mining requires substantial amounts of water for dust suppression and much larger volumes beyond that to wash coal and prepare it for sale. The electricity-water connection is more obvious for hydropower, where the force of descending water turns turbogenerators that produce electricity.

Quantifying plausible drought impacts on China’s electricity system helps illustrate the issue’s global importance. While China has suffered recent droughts that caused localized hydropower curtailments, the country’s electricity system has become accustomed over the past two decades to hydropower supplies that either rise year-on-year or else do not decline by more than 3.5% in a given calendar year. The PRC has never faced the stress test of losing 10% of its expected national hydro output over the course of a year, much less for a longer period of time.

Brazil offers a useful case study in both the magnitude of climate-driven hydro disruptions in a continent-sized country (Brazil’s physical area is 90% the size of China’s), as well as the downstream economic and social impacts. In 2001, Brazil suffered blackouts when hydro output declined nearly 15% from the previous year amid a multi-region drought. [25] The country’s power system again experienced severe strain between 2012 and 2015, when hydro output fell for four consecutive years due to drought. Then, 2021 saw renewed energy shortages as drought reduced national hydropower production by nearly 10% relative to 2020 levels. [26] Other energy sources were impacted as a result, particularly natural gas, with PetroBras (Brazil’s state champion oil and gas firm) forced to triple its imports of liquefied natural gas to compensate for the loss of hydro energy. [27]

It is worth noting that on average, much of Brazil is as wet — and sometimes far wetter — than the areas of southwest China where much of the PRC’s hydropower facilities are located. This suggests that the actual losses experienced by Brazilian hydro generators could plausibly occur if south/central China suffered a prolonged drought. Accordingly, it is defensible to assume a 15% annual loss of hydro capacity as the benchmark crisis level, which under current circumstances would mean losing nearly 200 terawatt-hours (TWh) of electricity output — roughly what Egypt generates in a year. Worse hydro scenarios could see the loss of 330 TWh — approximately the annual power production of Iran or Mexico.

Wind and solar farms cannot be surged to offset hydro losses, and China’s nuclear plants already run at high utilization levels. That leaves fossil-fueled thermal power, with only coal having the spare capacity and scale to potentially boost output by hundreds of terawatt-hours on short notice. Assuming engineering, logistical and operational challenges could be overcome, China’s coal use could increase by as much as 100 to 170 million tonnes per year, depending on the severity of hydropower shortfalls. The amount would be less if some sectors’ power demand was reduced by government order.

But those numbers assume coal plants can run unimpeded, which may not be accurate. Coal power itself is highly vulnerable to water risk, and depending on how geographically widespread a Chinese drought of record is, hydro and coal generation assets might be affected at the same time. Brazil’s 2001 drought affected multiple regions at once for an extended period. Similarly, the southwestern U.S. has suffered a decades-long drought that has brought Lake Mead to historically low levels and significantly reduced hydropower production by the Hoover Dam.

Significant Portion of China’s Coal Fleet at Risk

To assess the impacts of potential losses of coal power due to drought, the authors leveraged data from Global Energy Monitor’s Coal Plant Tracker [28] to build a database of approximately 2,000 utility-scale (300 megawatts or larger capacity) coal-fired power generation units located in China, including their known or likely mode of cooling. [29] Based on that information, we separated out coal units that were likely to be functionally “drought resistant,” in this case meaning power plants cooled by seawater or direct/indirect air cooling. These accounted for 158 gigawatts (GW) and 295 GW, respectively, out of a national total of approximately 963 GW. For reference, the next biggest coal power countries, India and the United States, each operate about 210 GW of capacity.

Geographically subdividing the remaining approximately 500 GW of potentially drought-exposed, utility-scale coal plant capacity suggests an “at-risk” capacity of 185 GW in the North China Plain region and a bit less than 175 GW in south-central China (east of Tibet and near and south of the Yangtze River). The nature of the risk and the timeframe in which it potentially manifests vary. Once-through power plants that take water from a river or lake, loop it through the plant, and discharge it a few degrees warmer back into the source waterbody are most vulnerable to lower water levels.

Plants that recirculate cooling water within a closed loop are less immediately exposed but must, over time, replace consumptive water losses caused by evaporation from their cooling towers. Unfortunately, the bulk of China’s coal plants are in regions considered water-stressed or highly water-stressed. [30] In addition, much of China’s coal capacity overlaps with key agricultural regions, which may force officials to make difficult decisions regarding water allocation to energy versus crop irrigation.

Figure 3 — China Utility-Scale Coal Plants By Cooling Type (Estimated using Google satellite imagery)

Prolonged drought also lowers water levels in rivers, which, in many parts of central and southern China, serve as key transport arteries for moving coal to power plants. Indeed, in provinces such as Hubei and Hunan, many power plants depend on river barges to deliver the coal they burn. Long-duration drought would reduce the safe water depth available for river traffic and shrink the load that barges can carry; a worst-case scenario would see some channels closed entirely.

Multiplied over a region with numerous coal plants and thousands of waterway kilometers, water level shifts could rapidly strain coal supplies to power plants. If plants along some of these waterways had to surge their electricity output to compensate for hydro output losses elsewhere, logistical pinch points would be significantly magnified. Recent water level challenges for the United States’ Mississippi River system are a case in point, with its barge traffic highly sensitive to even slight changes in water levels; similar physics likely apply in many waterways in China as well.

Taking all of these factors together, it is reasonable to assume that Chinese coal plants in affected areas could be forced to de-rate output by 5% to 10% during a prolonged drought. A drought emergency could thus potentially reduce thermal power supplies by about 80 TWh per year in the North China Plain region and by nearly that amount again in south-central China. If both regions were affected simultaneously, the aggregate thermal power production loss could nearly equal the loss of hydropower. Seasonality would likely exacerbate the impact, since China’s hydro generation typically peaks in late summer, and July and August are consistently two of the country’s highest electricity-use times.

A China Electricity Crisis Would Create a Global Supply Chain Crisis

Power supply problems in China extend far beyond flickering lights and sputtering air conditioners in Wuhan or Beijing. Industrial facilities, many of them very power-intensive, account for over 65% of electricity use in China. [31] This means that to minimize the immediate human impact of broad, uncontrolled blackouts, Party officials would force China’s industrial sector to curtail operations to ease the grid load — as they did during power shortfalls in 2021 and 2022.

Blackouts by decree disrupt key material supplies, raise prices and turbocharge inflationary pressures. China is, by a significant margin, the world’s largest producer of aluminum, ferro-silicon, lead, magnesium, manganese, zinc, and most rare earths and many other specialty metals and materials. Power outages in even a single key province could impact global markets — as European carmakers discovered in late 2021 when power shortages led local officials to curtail magnesium smelter operations in Shaanxi Province, home to about 50% of global output. [32] As inventories plummeted, prices spiked to seven times their level [33] at the beginning of the year, and European industrial consumers called for government action to ensure supplies.

Electricity problems in China would also destabilize energy transition efforts globally. In a cruel irony, many of the same energy technologies the world seeks to manage climate change and shift to less water-intensive electricity production come from coal and power-intensive supply chains centered in China. Polysilicon for solar cells and rare earth metals are just two of many industries that would very likely be disrupted by a sustained regional-level water and power crisis. The same is true for electric vehicle batteries, where China dominates raw material refining and cell production. [34]

China-centric supply chains took decades to build and, even under emergent conditions, would not be easily or quickly re-shored. But time is of the essence for crafting policies to prepare key global markets for an extended China water crisis event that is among the most important “grey rhino” (i.e., hiding in plain sight) macro risks currently facing the global economy. Global supply chains are not presently prepared for a major drought event in China that disrupts grain trade patterns and key industrial materials production, because the last time China had such a drought, it was not the “factory floor of the world.”

Policy Challenges Ahead — No Silver Bullets

The march toward water bankruptcy is, to quote Hemingway’s “The Sun Also Rises,” a process that unfolds “gradually, then suddenly.” There is still time for policy interventions to shift China onto a path of sustainable water consumption. However, the universe of potential solutions is bounded by harsh economic, physical and political realities. As former British diplomat and China expert Charlie Parton puts it, “China can print money but it cannot print water.” [35]

Rather than printing water, China faces choices between managing demand through price, convincing people and businesses to change their water use patterns, and building their way toward increased water supplies. None of these offer a “silver bullet.” Much like the energy transition, China’s water transition will require a “silver shotgun shell” incorporating multiple options that complement one another and are not mutually exclusive. Beijing and the broader world must grapple with the reality that most policy options require major tradeoffs on strategic issues such as food self-sufficiency, industrial development, energy and emissions, and relationships with hydrologically-connected neighboring countries. Internally, Chinese policymakers must face the reality that by nature water conflicts are zero-sum, often require redistributive solutions and have tangible impacts that show up quickly. The country’s past 40 years of growth have emphasized a “rising tide lifts all boats” mindset. Water is different, and multiple examples from other countries hint that redistributive solutions could arouse regionalist passions, a matter that, given China’s history of hinterland rebellions, the government would be keen to avoid.

Perhaps the most comprehensive reform would be to make water more expensive to encourage efficiency. Yet China’s input-intensive heavy industrial base, and, perhaps most of all, rural farmers, are accustomed to cheap water. While agriculture accounts for over 60% of China’s water consumption, the vast majority of China’s farms are under three acres in size. Small tracts operating on thin margins may not be able to afford water-saving equipment like drip irrigation. Consolidating them into larger operations would require comprehensive land ownership reform — a politically loaded subject. Moreover, land consolidation alone would likely be insufficient without repricing water; survey data [36] suggest that the default response of farmers in northern China to declining water tables is to simply drill deeper wells and install more powerful pumps — responses that only accelerate the crisis.

The government may also work to shift consumer habits through suasion. Since the early 2000s, the Chinese government has promoted potatoes as a substitute for grain given their lower water intensity. [37] However, such campaigns face deep-seated biases that potatoes are a food of the poor and have had little enforcement, as they belie the Party’s preferred narrative of economic progress. Persuasion campaigns also run afoul of the reality that while the government can use its policing powers to prevent people from doing things it deems undesirable, compelling citizens to do things Beijing wants — having more children, pursuing consumerist ambitions and eating more water-efficient potatoes — is a far harder task.

China’s long history as a global hydraulic engineering superpower — exemplified by the still-operational 2,200-year-old Dujiangyan Irrigation Works in Sichuan [38] — suggests central and local leaders alike may gravitate toward supply-side solutions. The Grand Canal and other internal waterways that have operated for centuries attest to China’s ability to use capital, labor and technical skill to combat hydrological disadvantages. Ongoing work on the $60 billion South-to-North Water Diversion Project represents the modern incarnation of such projects. The scheme’s canals and pumps are now reportedly able to transfer up to 25 billion cubic meters annually of water from the Yangtze River [39] and could ultimately move nearly twice that volume, which would amount to approximately 5% of the river’s current annual discharge. [40] At such scale, the project would become a potential liability if the system intensified water stress in southern China while failing to fully alleviate supply constraints in the North.

Desalination is another potential supply-side solution. Unfortunately, scaling it up to the level needed to materially close northern China’s water supply gap would be a gargantuan task. The roughly 20,000 plants in operation worldwide can produce about 36.5 billion cubic meters of water per year — or roughly 6% of China’s annual water consumption. This highlights the difficulty in relying on desalination to make a meaningful dent in the estimated 25% water supply gap facing the nation.

Desalinated water is also likely unsustainable in energy terms. Academic studies [41] suggest that at the low end, desalination via reverse osmosis requires about 4 kilowatt-hours of energy per cubic meter of water produced — enough to run a typical LED lightbulb for nearly two weeks. Thermal distillation can be five times as energy intensive. [42] As such, producing and transporting enough desalinated seawater to allow the 150 million-odd residents of the North China Plain to each have 1,700 cubic meters of water annually (the baseline below which water stress commences) would potentially consume as much energy each year as the entire country of Japan. This would be nearly 12% of China’s entire current primary energy consumption. Even much lower levels of desalination would still materially impact regional energy demands.

Finally, perhaps the greatest long-term opportunity for China is for the widespread use of drought-resistant seeds and farming techniques, especially given the agricultural sector’s disproportionate share of water consumption. If advanced seed breeding and biotechnology enhancement could drive a 30% reduction in water use for the agricultural sector — which is within the realm of possibility — much of the structural shortfall could be addressed. It is important to note that this does not factor in the risk of further water availability reduction driven by climate change, such as the potential for glacially fed rivers to see large volume declines over the coming decades; in such an outcome, even a 30% reduction in agricultural water use would be insufficient.

“Virtual Water” Fraught with Challenges

“Virtual water,” in the form of agricultural imports such as soybeans, offers another option. China already imports approximately 100 million tonnes per year of soybeans but, as a matter of policy, seeks to maintain a high degree of self-sufficiency in supplies of corn, rice and wheat. Saudi Arabia offers a precedent in using grain imports to rebalance an unsustainable domestic water system. Local agricultural policies had, at one point, made Saudi Arabia a net exporter of wheat, but the drawdown of local groundwater supplies proved unsustainable, and by the mid-2000s the kingdom had taken the strategic decision to import wheat from the global market to reduce local water scarcity. [43]

Iran offers a more cautionary tale on the consequences of defying hydrological realities. Unlike Saudi Arabia, officials in Tehran chose to continue emphasizing grain self-sufficiency at the cost of scarce local water resources. [44] The result has been a compounding water bankruptcy that now sparks violent unrest, [45] exacerbates pre-existing social fault lines and has reached a point of being un-fixable without radical policy shifts — precisely the type of situation China presumably seeks to avoid. While the Saudi example is positive, a Chinese decision to rely more heavily on grain imports would be an unprecedented event for global markets, given that its total grain needs are more than 70 times larger than Saudi Arabia’s. Production in places like Brazil, the U.S. and Russia would take years to materially respond, and sudden large-demand increases from China would likely challenge the stability of the food-energy-water nexus for many grain exporters.

The same law of large numbers would apply to Chinese attempts to further expand farmholdings abroad. Political shifts in breadbaskets like North America and Australia likely foreclose PRC firms’ access to the millions of hectares of farmland it needs to offset domestic water shortfalls. Argentina and Brazil remain question marks. In Eurasia, Russia would be a mercurial partner, and farming operations in Kazakhstan would potentially be subject to Russian veto. Africa, the remaining location with ample land and water, would require massive additional investments in infrastructure to irrigate fields and reliably move grain to ports. As Saudi firms have learned in Ethiopia, foreign farmholdings can rapidly become lightning rods in areas that, in many instances, are already cleft by political instability and physical violence. [46]

China could also seek to import water from further afield in either “wet” or virtual form, such as diverting water from Lake Baikal and other adjacent resource bases. However, such efforts are likely to prove economically infeasible, volumetrically insufficient relative to China’s growing water shortage, too slow to construct or, most likely, all three. Some transboundary water resources are accessible, but at extremely high cost to downstream countries. In the most prominent example, satellite data reveal that China used 10 large dams on the upper reaches of the Mekong River to capture water from the river’s normal wet season flow peaks and retain it for producing hydropower. [47] More low-carbon electrons benefit China’s emissions control efforts, but as Beijing uses the dams to try to reinforce its domestic food-energy-water nexus, it jeopardizes the food and water security of millions downstream in Laos, Cambodia and Thailand.

When the Wells Run Dry

Without urgent action, the impact of China’s water shortages will ripple across the globe and dramatically perturb global markets for food, energy and industrial goods. Sustained water shortages will also force wrenching changes in China’s economy as officials allocate an increasingly scarce, vital resource between agriculture, industry and household usage. The net effect is likely to be further headwinds restraining economic activity in China, which would result in a supply-side shock with few easy avenues of resolution.

A water crisis that curtailed activity in China’s real economy would rapidly morph from a domestic issue to a global macroeconomic crisis. Given the world’s high reliance on China for a wide array of economically critical goods, forced production shutdowns due to water shortages would cripple supply chains across the globe. Further, the disruption to agricultural markets would place enormous stress on countries that rely on large quantities of imported food — many of which already suffer from political instability.

China’s water crisis presents a policy challenge that is “too big to let fail” but also “not too big to fix” if decisive actions are taken now. Much of the work will, by necessity, be conducted in China under Beijing’s political mandates, but to the extent the U.S. and its allies can assist, it is in their interest to do so. Addressing China’s water crisis and its pressure on the food-energy-water nexus is one of the precious few areas where bilateral cooperation may still be possible.

The U.S. must also take urgent action to decouple its most critical supply chains from China as quickly and comprehensively as possible. Time is of the essence, and policymakers should treat this as one of their most urgent tasks, assuming a three to five-year timetable for substantial completion. Likewise, water and climate experts in places like Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Kazakhstan, Russia, Ukraine and the U.S. should urgently consider how their agricultural and water systems could — or could not — respond if asked to meet the call triggered by a sustained failure of grain harvests in China.

The world faces an energy transition challenge of unprecedented scale that dominates the headlines, but the food-energy-water nexus deserves equal, if not more, attention. As China’s water clock relentlessly ticks toward a global crisis, decisive steps must be taken while there is still time to act.

[1] “Explainer: The power crunch in China's Sichuan and why it matters,” Reuters, August 26, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/china/power-crunch-chinas-sichuan-why-it-matters-2022-08-26/ .

[2] Water Footprint Network, “Product Gallery,” n.d., https://waterfootprint.org/en/resources/interactive-tools/product-gallery/ .

[3] Javier Lozano Parra, Manuel Pulido Fernández, and Jacinto Garrido Velarde, “The Availability of Water in Chile: A Regional View from a Geographical Perspective,” in Resources of Water, eds. Prathna Thanjavur Chandrasekaran, Muhammad Salik Javaid, and Aftab Sadiq (IntechOpen, 2020) http://dx.doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.92169 .

[4] “Reimagining WASH: Water Security for All,” UNICEF, March 2021, https://www.unicef.org/media/95241/file/water-security-for-all.pdf .

[5] Siao Sun et al., “Domestic groundwater depletion supports China's full supply chains,” Water Resources Research 58, no. 5 (May 2022), https://doi.org/10.1029/2021WR030695 .

[6] “How Does Water Security Affect China’s Development?” Center for Strategic and International Studies, China Power Project, n.d., https://chinapower.csis.org/china-water-security/ .

[7] View our data on China’s fertilizer use and pesticide use . (Data derived from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization).

[8] Carla Freeman, “Quenching the Thirsty Dragon: The South-North Water Transfer Project—Old Plumbing for New China?” Wilson Center, n.d., https://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/quenching-the-thirsty-dragon-the-south-north-water-transfer-project-old-plumbing-for-new .

[9] Zhang Wenjing, Jiang Hong, and Sarah Rogers, “The next phase of China’s water infrastructure: a national water grid,” China Dialogue, March 16, 2022, https://chinadialogue.net/en/cities/the-next-phase-of-chinas-water-infrastructure-a-national-water-grid/ .

[10] Changxin Xu, Lihua Yang, Bin Zhang, and Min Song, “Bargaining power and information asymmetry in China’s water market: an empirical two-tier stochastic frontier analysis,” Empirical Economics 61, no. 5 (2020): 2395-2418, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-020-01972-7 .

[11] “China's southern megacities warn of water shortages during East River drought,” Reuters, December 9, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/chinas-southern-megacities-warn-water-shortages-during-east-river-drought-2021-12-09/ .

[12] “Annual Freshwater Withdrawals, Total (Billion Cubic Meters),” The World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ER.H2O.FWTL.K3 ; “Annual Freshwater Withdrawals, Agriculture (% of Total Freshwater Withdrawal),” The World Bank, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ER.H2O.FWAG.ZS .

[13] “The Water Content of Things: How much water does it take to grow a hamburger?” United States Geological Survey, n.d., https://water.usgs.gov/edu/activity-watercontent.php .

[14] Gabriel Collins. 2017. Carbohydrates, H2O, and Hydrocarbons: Grain Supply Security and the Food-Water-Energy Nexus in the Arabian Gulf Region. Research paper no. 06.01.17. Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, Houston, Texas, published in conjunction with Qatar Leadership Centre. https://www.bakerinstitute.org/sites/default/files/2017-09/import/CES-pub-QLC_Nexus-061317.pdf .

[15] “Annual Freshwater Withdrawals, agriculture (% of total freshwater withdrawal),” The World Bank, n.d., https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/ER.H2O.FWAG.ZS?locations=CN .

[16] Gabriel B. Collins and Andrew S. Erickson, “Keeping the Mandate of Heaven: Why China’s Leaders Focus Heavily on Grain Prices and Security,” China SignPost™ (洞察中国), no. 22, February 17, 2011, https://www.chinasignpost.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/02/China-SignPost_22_Keeping-the-Mandate-of-Heaven_Grain-supply-problems-a-major-political-risk_20110217.pdf .

[17] View our data on China’s arable and irrigated lands .

[18] View our data on agricultural land use in Australia, Brazil, Canada, Russia, Ukraine and the United States , for comparison to China’s land use.

[19] Jinxia Wang, Jikun Huang, Qiuqiong Huang, and Scott Rozelle, “Privatization of tubewells in North China: Determinants and impacts on irrigated area, productivity and the water table,” Hydrogeology Journal 14 (2006): 275–285, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10040-005-0482-1 ; Wei Feng et al., “Evaluation of groundwater depletion in North China using the Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) data and ground-based measurements,” Water Resources Research 49, no. 4 (2013): 2110-2118, https://doi.org/10.1002/wrcr.20192 .

[20] Ujjayant Chakravorty et al., “A Tale of Two Roads: Groundwater Depletion in the North China Plain,” December 2019, https://www.aeaweb.org/conference/2020/preliminary/paper/rZe7Nd99 .

[21] Justin C. Thompson, Charles W. Kreitler, and Michael H. Young, “Exploring Groundwater Recoverability in Texas: Maximum Economically Recoverable Storage,” Texas Water Journal 11, no. 9 (2020): 152-171, https://journals.tdl.org/twj/index.php/twj/article/view/7113/6472 .

[22] We use 33% as a benchmark loss factor based on the recent real-world experience of a serious drought and its impact on grain crops in Argentina. See “Severe drought impacts on Argentine corn and soybean crop estimates,” MercoPress, March 9, 2022, https://en.mercopress.com/2022/03/09/severe-drought-impacts-on-argentine-corn-and-soybean-crop-estimates .

[23] “Severe drought impacts on Argentine corn and soybean crop estimates,” MercoPress.

[24] View our data on China’s global staple grain production share . (Data derived from a custom run of the USDA's PSD system https://apps.fas.usda.gov/psdonline/app/index.html#/app/advQuery ).

[25] Iracema F. A Cavalcanti and Vernon E. Kousky, “Drought In Brazil During Summer And Fall 2001 And Associated Atmospheric Circulation Features,” Center of Climate Prediction, National Centers Environmental Prediction, 2004, http://bit.ly/3Ep1UEL .

[26] “Brazil minister warns of deeper energy crisis amid worsening drought,” Reuters, August 31, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/world/americas/brazil-minister-warns-deeper-energy-crisis-amid-worsening-drought-2021-08-31/ .

[27] Jeff Fick, “Petrobras triples LNG imports in 2021 amid drought, pipeline work,” S&P Global Commodity Insights, January 13, 2022, https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/natural-gas/011322-petrobras-triples-lng-imports-in-2021-amid-drought-pipeline-work .

[28] “Global Coal Plant Tracker,” Global Energy Monitor, https://globalenergymonitor.org/projects/global-coal-plant-tracker/ .

[29] View our data on China’s utility-scale coal units .

[30] X. W. Liao et al., “Water shortage risks for China's coal power plants under climate change,” Environmental Research Letters 16 (2021), https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/abba52 .

[31] “Electricity consumption from January to December 2021,” China Electricity Council, January 18, 2022, https://cec.org.cn/detail/index.html?3-305885 .

[32] “Chinese magnesium supplies pick up as production resumes,” Shaanxi News, November 19, 2021, http://en.shaanxi.gov.cn/news/sn/202111/t20211119_2200973.html .

[33] Andy Home, “Column: Europe's magnesium crunch poses another carbon conundrum: Andy Home,” Reuters, October 26, 2021, https://www.reuters.com/business/energy/europes-magnesium-crunch-poses-another-carbon-conundrum-andy-home-2021-10-26/ .

[34] Ben Kilbey, “China continues to dominate global EV supply chain: BNEF,” S&P Global Commodity Insights, September 16, 2020, https://www.spglobal.com/commodityinsights/en/market-insights/latest-news/electric-power/091620-china-continues-to-dominate-global-ev-supply-chain-bnef .

[35] Charlie Parton, “China’s Looming Water Crisis,” China Dialogue, April 2018, http://bit.ly/3E0gX6r .

[36] Jinxia Wang et al., “Groundwater irrigation and management in northern China: status, trends, and challenges,” International Journal of Water Resources Development, 2019, https://doi.org/10.1080/07900627.2019.1584094 .

[37] Niu Shuping and David Stanway, “Chinese potatoes to chip in as water shortages hit staple crops,” Reuters, July 30, 2015, https://www.reuters.com/article/china-agriculture-potato/chinese-potatoes-to-chip-in-as-water-shortages-hit-staple-crops-idUSL3N10A1TO20150730 .

[38] “Mount Qingcheng and the Dujiangyan Irrigation System,” UNESCO, n.d., https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/1001/ .

[39] Jon Barnett et al., “Sustainability: Transfer project cannot meet China's water needs,” Nature 527 (2015): 295-297, https://doi.org/10.1038/527295a .

[40] S. L. Yang et al., “Trends in annual discharge from the Yangtze River to the sea (1865–2004),” Hydrological Sciences Journal 50, no. 5 (2009), https://doi.org/10.1623/hysj.2005.50.5.825 .

[41] Collins, Carbohydrates, H2O, and Hydrocarbons.

[42] Collins, Carbohydrates, H2O, and Hydrocarbons.

[43] Collins, Carbohydrates, H2O, and Hydrocarbons.

[44] Gabriel Collins. 2017. Iran’s Looming Water Bankruptcy. Research Paper no. 04.04.17. Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy, Houston, Texas. https://www.bakerinstitute.org/research/irans-looming-water-bankruptcy .

[45] 'Give Isfahan Life!' Water Shortages Unleash Waves Of Protest In Iran,” RFE/RL's Radio Farda, November 24, 2021, https://www.rferl.org/a/iran-water-shortages-protests/31577306.html .

[46] Tom Burgis, “The great land rush — Ethiopia: The billionaire’s farm,” Financial Times Investigations, n.d., https://ig.ft.com/sites/land-rush-investment/ethiopia/ .

[47] Brian Eyler et al., “Mekong Dam Monitor at One Year: What Have We Learned?” Stimson Center, 2022, https://www.stimson.org/2022/mdm-one-year-findings/ .

This material may be quoted or reproduced without prior permission, provided appropriate credit is given to the author and Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy. The views expressed herein are those of the individual author(s), and do not necessarily represent the views of Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy.

Related Research

Baker Briefing: Lessons From Hurricane Beryl

Annexation of Taiwan: A Defeat From Which the US and Its Allies Could Not Retreat

Chile’s New Lithium Strategy: A Market Boost or Miss?

Stanford University

SPICE is a program of the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies.

Water Issues in China

As China’s population and economy have grown, so has its thirst for water. Today China is the world’s biggest water user, accounting for 13 percent of the world’s freshwater consumption. 26 Not only do humans use water for drinking; we use it to wash our clothes, bathe, cook, and clean. On a larger scale, water is heavily used for countless other purposes such as industrial manufacturing, household plumbing, raising agriculture and livestock, and even producing energy. All of these processes require good, clean water. Luckily, China is home to many sources of fresh water. People have relied on these sources—rivers, lakes, rain, and aquifers—for thousands of years. In a country that is experiencing such rapid urbanization and economic development, however, clean water is becoming more and more scarce. Aquifer levels are dropping, lakes are disappearing, rivers are drying up or becoming polluted, and air contaminants are producing acid rain. Water shortages plague over half of China’s cities. 27 Today, water is one of China’s Imost crucial issues.

China’s current water crisis is driven by two primary factors. The first of these is China’s uneven distribution of water. Because of its large and diverse geography, China has a wide spectrum of terrains and climate zones. While southern and eastern China enjoy abundant rainfall, the northern and western regions of the country receive very little. This weather pattern can lead to unfortunate and seemingly contradictory effects, with some provinces battling floods while others are suffering from months-long droughts. Between mid-April and the end of May 2006, southern and northeastern China endured three brutal rainstorms, bringing rainfall of 400 millimeters (15.7 inches) or more per day. This resulted in regional flooding, destruction of vast crop fields and thousands of homes, 60 to 70 human deaths, and economic losses of nearly $1.6 billion. At the same time, however, northern China was experiencing a severe drought that affected or threatened 182 million hectares (450 million acres) of farmland, 8.7 million livestock, and 95 million people. 28 Beijing, the nation’s capital in northern China, was suffering its worst drought in 50 years. It received only 17 millimeters (0.7 inches) of rain in four months—a fraction of a day’s rainfall in southern China. 29

Extremes in this climate pattern have led to problems for China. Although the floods in April and May 2006 were damaging to the cities and communities of southern China, they were not nearly as disastrous as others in China’s recent history. For example, one flood in 1998 caused the Yangtze River—China’s largest—to overflow, killing more than 3,500 people, damaging or destroying more than 21 million houses, and causing economic losses of $32 billion. 30 Another flood in 1954 was even worse, taking 30,000 lives. 31 To address the common flooding of the south, China has recently built the Three Gorges Dam, an ambitious and controversial project meant to monitor and control the Yangtze’s water levels to prevent future floods.

Northern China faces the opposite problem: it often receives far too little rainwater. In the north, the demand for water surpasses the available supply, largely because it has two-thirds of China’s total cropland and 43 percent of its population, but only 14 percent of its water supply. 32,33 Beijing and other northern cities and communities have had to rely on other sources of water to irrigate their crops, run their cities, and feed their people. Although northern China sits atop two large underground aquifers, so much water is being drained from them that their levels are dropping at an incredible rate. In Hebei Province next to Beijing, the water level of the deep aquifer falls three meters every year. 34 Rivers are also used for their water, but overuse has diminished even the Yellow River to a trickle. The Yellow River—northern China’s main river—has dried up every year since 1985. 35 With aquifers and rivers suffering from overuse, lakes are also being affected. Hebei has already lost 969 of its 1,052 lakes. 36 Yet with all of northern China’s water resources being tapped, water shortages still cost the Chinese economy a lot of money. According to one report, water shortages are responsible for direct economic losses of $35 billion annually, about 2.5 times the average annual losses due to floods. 37

Besides the disparity in water supply between the north and south, China’s water crisis has a second factor: pollution. Even in water-rich areas of China, pollution is decreasing the supply of clean, usable water. According to estimates, a full 70 percent of China’s rivers and lakes are currently contaminated, half of China’s cities have groundwater that is significantly polluted, and one-third of China’s landmass is affected by acid rain. 38,39,40 Today, most of the Yellow River is unfit even for swimming, and experts have called the Yangtze “cancerous.” 41 Because hundreds of cities—including large ones like Shanghai and Chongqing—rely on these rivers for their drinking water, people all over the country are suffering from China’s water pollution crisis. The central government has begun to fight the pollution problem by issuing stricter regulations on pollutants and spending billions of dollars on water projects, but water quality is generally still poor. In 2006, Chongqing’s tap water contained 80 of 101 banned pollutants. 42

Causes and Effects

China’s water crisis is both natural and man-made. For example, China’s northern regions are arid because of its natural geography and climate patterns, but humans have made these effects even worse. Rapid climate change, which most scientists consider largely human-influenced, is shortening China’s rainy seasons and melting important glaciers that feed the Yellow River. 43 Northern China’s rivers are drying up as they are strained by a growing population, more factories, and water-hungry crop fields. Overgrazing by livestock—which have become incredibly numerous—has turned grasslands into sandy deserts, which in turn has caused ecosystems to lose their natural water-trapping capabilities and become even dryer. 44 In this way, many of China’s water problems stem from both natural and human causes.

Although the water crisis affects the whole country, farmers experience a large part of its effects, simply because of economic reasons. Growing food is water intensive, but not highly profitable. A farmer needs 1,000 tons of water to produce a ton of wheat worth $150, whereas a factory needs only 14 tons of water to produce a ton of steel worth $550. In China, where the government is desperate to create jobs and grow the economy, it makes economic sense to prioritize a steel factory’s water needs over a farmer’s. Thus, farmers’ needs are often sacrificed. In Beijing, for example, water was diverted from the Juma River to supply a petrochemical company, while 120,000 villagers downstream watched the river dry up, no longer able to use the Juma for irrigation. 45 Episodes like this are not uncommon.

Farmers sometimes contribute to China’s water scarcity and pollution problems as well. The high water-cost of irrigation—which accounts for 70 percent of water use worldwide 46 —is often raised even higher in China by inefficient irrigation methods. In addition, the agricultural chemicals (like pesticides and fertilizers) that are used on crops sometimes turn into toxic runoff that can pollute groundwater. 47

Factories are even worse polluters, releasing untreated waste and chemicals into China’s rivers. Many times, the pollution happens by accident. According to authorities, one pollution accident occurs every two to three days in China. 48 In one case, in 2005, a chemical explosion at a petrochemical plant spilled 100 tons of pollutants into the Songhua River, forcing the downstream city of Harbin to shut down its entire water system, leaving 3.8 million residents without water for four days. 49 But most times, pollution is intentional; the same petrochemical plant has released more than 150 tons of mercury into the Songhua since it was built. 50 About 80 percent of China’s 7,500 dirtiest factories are located on rivers, lakes, or in heavily populated areas, so the potential for future pollution—accidental or not—is enormous. 51