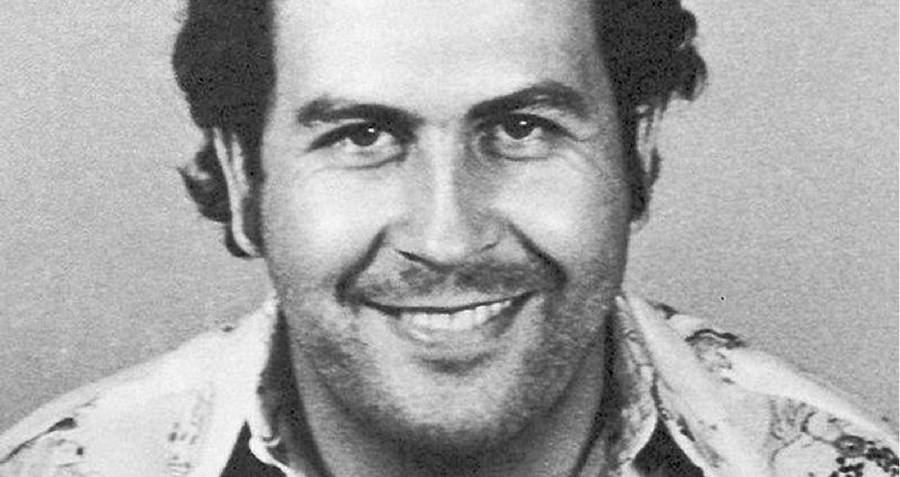

Pablo Escobar

Colombian drug lord Pablo Escobar helped create and run the notorious Medellín cartel and was responsible for killing thousands of people.

We may earn commission from links on this page, but we only recommend products we back.

Quick Facts

Establishing the medellín cartel, rapid rise in power, escobar’s short-lived stint in politics, a large body count, escobar’s luxury prison, wife and children, pop culture portrayals, who was pablo escobar.

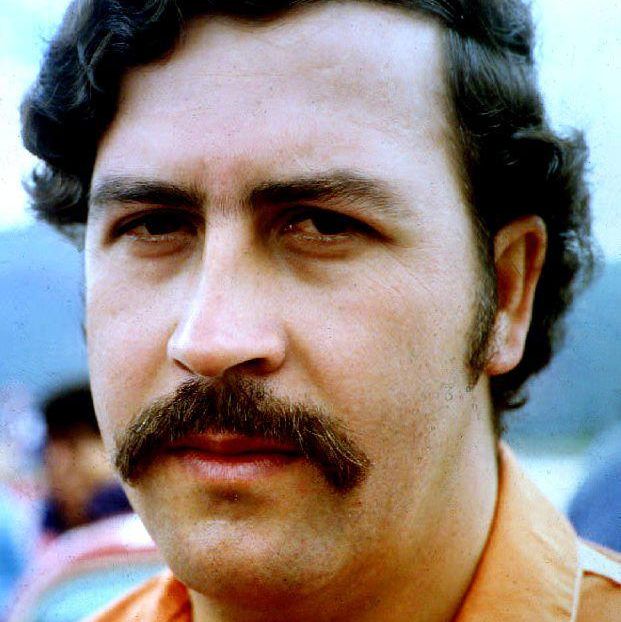

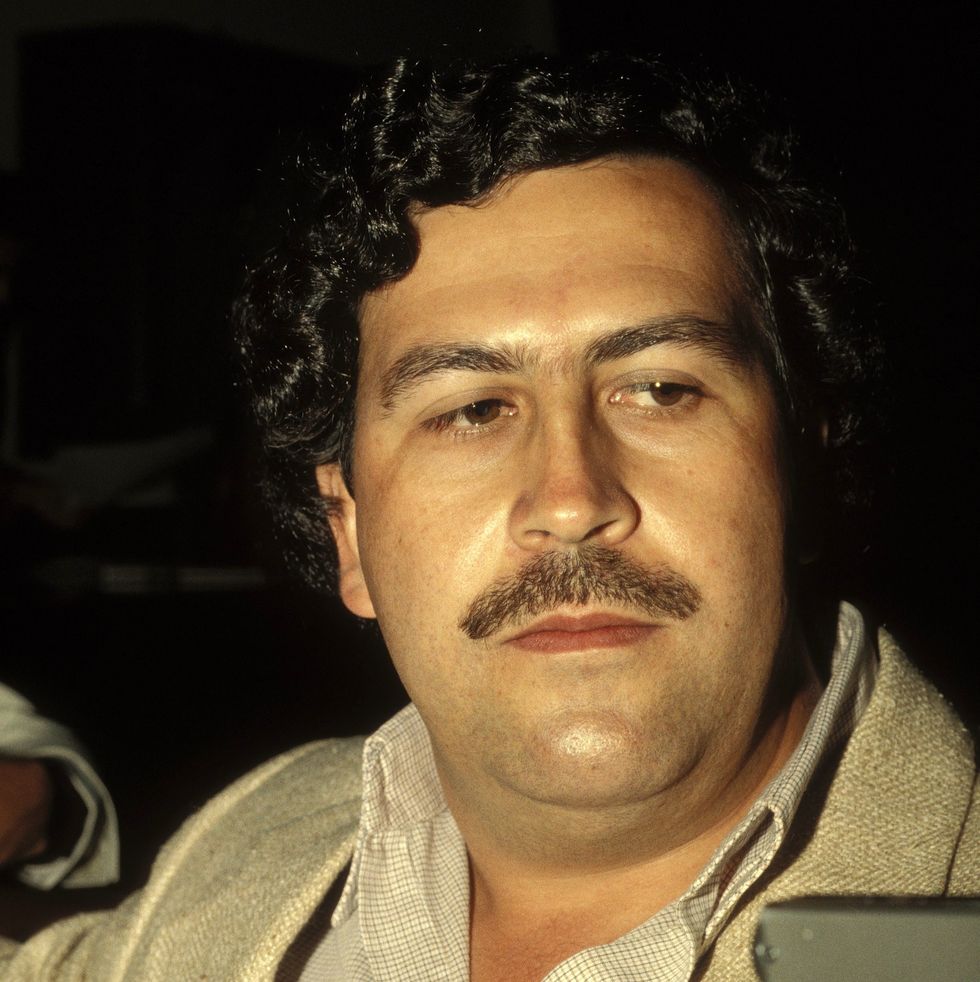

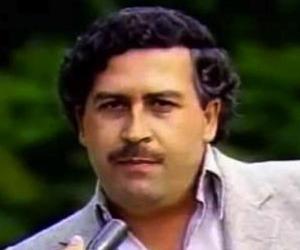

Pablo Escobar was a Colombian drug trafficker who collaborated with other criminals to form the Medellín cartel in the early 1970s. Eventually, he controlled over 80 percent of the cocaine shipped to the United States, earning the nickname “The King of Cocaine.” He amassed an estimated net worth of $30 billion and was named one of the 10 richest people on Earth by Forbes . He earned popularity by sponsoring charity projects and soccer clubs, but later, terror campaigns that resulted in the murder of thousands turned public opinion against him. After surrendering to the Colombian authorities in 1991, Escobar escaped detainment in 1992 and was a fugitive until his dramatic death in December 1993.

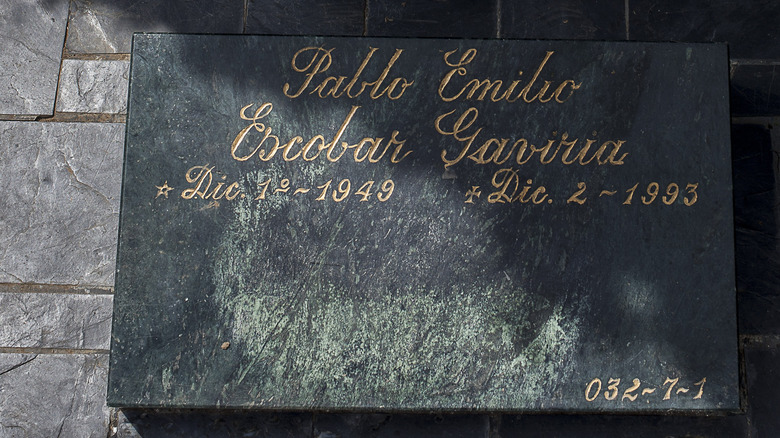

FULL NAME: Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria BORN: December 1, 1949 DIED: December 2, 1993 BIRTHPLACE: Rionegro, Antioquia, Colombia SPOUSE: Maria Victoria Henao (1976-1993) CHILDREN: Juan Pablo and Manuela ASTROLOGICAL SIGN: Sagittarius

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria was born on December 1, 1949, in the Colombian city of Rionegro, Antioquia. His family later moved to the suburb of Envigado. He was the third of seven children born in poverty to a schoolteacher mother and a peasant farmer father. From an early age, Escobar packed a unique ambition to raise himself up from his humble beginnings and dreamed of becoming the president of Colombia one day.

Escobar reportedly began his life of crime early, stealing tombstones and selling phony diplomas. It wasn’t long before he started stealing cars, then moving into the smuggling business. Escobar’s early prominence came during the “Marlboro Wars,” in which he played a high-profile role in the control of Colombia’s smuggled cigarette market. This episode proved to be a valuable training ground for the future narcotics kingpin.

It wasn’t by chance that Colombia came to dominate the cocaine trade. Beginning in the early 1970s, the country became a prime smuggling ground for marijuana. But as the cocaine market flourished, Colombia’s geographical location proved to be its biggest asset. Situated at the northern tip of South America between the thriving coca cultivation epicenters of Peru and Bolivia, the country came to dominate the global cocaine trade with the United States, the biggest market for the drug and just a short trip to the north.

Escobar, who had already been involved in organized crime for a decade at this point, moved quickly to grab control of the cocaine trade. In 1975, the drug trafficker Fabio Restrepo from the city of Medellín, Colombia, was murdered. It was widely believed his death came at the orders of Escobar, who immediately seized power and expanded Restrepo’s operation into something the world had never seen. Under Escobar’s leadership, large amounts of coca paste were purchased in Bolivia and Peru then processed and transported to America. Escobar worked with a small group to form the infamous Medellín cartel.

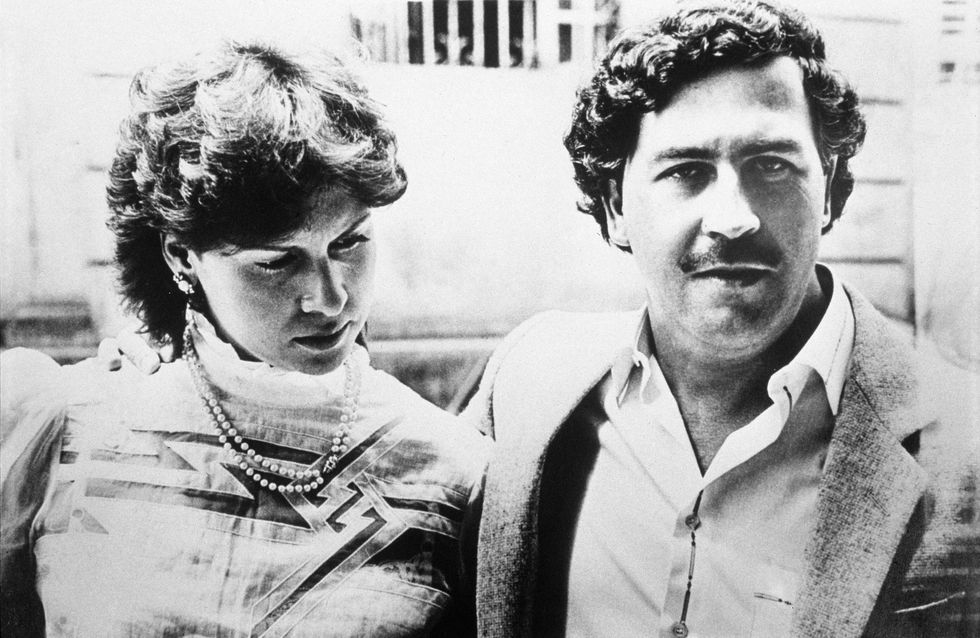

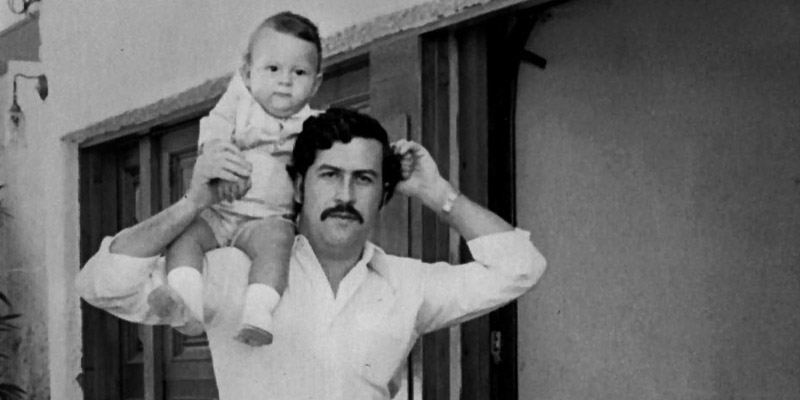

Also around this time, Escobar started a family with his marriage to Maria Victoria Henao, who was 11 years his junior and still a teenager at the time of their 1976 wedding. They went on to have two children.

Killing Pablo: The Hunt for the World's Greatest Outlaw

Escobar’s rapid rise brought him to the attention of the Departamento Administrativo de Seguridad (DAS), who arrested him in May 1976 upon his return from a drug trafficking trip in Ecuador. Authorities found 39 kilograms of cocaine hidden in the spare tire of his truck. Escobar escaped the charges by bribing a judge, and the two DAS agents responsible for his arrest were killed the next year, according to Mark Bowden book Killing Pablo . Around this time, Escobar developed his signature pattern of dealing with authorities called plata o plomo , Spanish for “silver or lead,” in which they could accept bribes or be assassinated, according to Bowden.

In 1978, Escobar spent millions to purchase 20 square kilometers of land in Antioquia, Colombia, where he built his luxury estate Hacienda Nápoles . It contained a sculpture garden, lake, private bullring, and other amenities for his family and members of the cartel. It also featured a collection of luxury cars and bikes, as well as a zoo with antelope, elephants, giraffes, hippos, ponies, ostriches, and exotic birds. After Escobar’s death, it was turned into a theme park. (Today, the hippo population—which traces back to Escobar’s original transplants—has swelled in the country , causing environmental destruction and providing tourism opportunities.)

As the demand for cocaine grew in the United States, Escobar established additional smuggling shipments and distribution networks in various locations. That included establishing a shipment base on a private island in the Bahamas with the help of cartel cofounder Carlos Lehder. By the mid-1980s, Escobar had an estimated net worth of $30 billion and was named one of the 10 richest people on Earth by Forbes . Cash was so prevalent that Escobar purchased a Learjet for the sole purpose of flying his money. At the time, Escobar controlled more than 80 percent of the cocaine smuggled into the United States; more than 15 tons were reportedly smuggled each day, netting the Medellín cartel as much as $420 million a week.

As Escobar’s fortune and fame grew, he dreamed to be seen as a leader. In some ways, he positioned himself as a Robin Hood–like figure, a description was echoed by many locals, by spending money to expand social programs for the poor. He spent millions to develop Medellín’s poor neighborhoods, where its residents felt he helped them far more than the government ever had. He built roads, electric lines, soccer fields, roller-skating rinks, and more, and paid the workers in his cocaine labs enough money that they could afford houses and cars, according to Bowden.

Still harboring his youthful ambition to become the nation’s president, Escobar entered politics and supported the formation of the Liberal Party of Colombia. In 1982, he was elected as an alternate member of Colombia’s Congress, but Minister of Justice Rodrigo Lara-Bonilla investigated him and highlighted the illegal means by which he had obtained his wealth, forcing Escobar to resign two years after his election. A few months later, Lara-Bonilla was murdered, according to the book Kings of Cocaine , by Guy Gugliotta and Jeff Leen.

Escobar was responsible for the killing of thousands of people, including politicians, civil servants, journalists, and ordinary citizens. When he realized that he had no shot of becoming Colombia’s president, and with the United States pushing for his capture and extradition, Escobar unleashed his fury on his enemies in the hopes of influencing Colombian politics. His goal was a no-extradition clause and amnesty for drug barons in exchange for giving up the trade.

Escobar’s terror campaign claimed the lives of three Colombian presidential candidates, an attorney general, scores of judges, and more than 1,000 police officers. In addition, Escobar was implicated as the mastermind behind the bombing of a Colombian jetliner. In November 1989, Escobar arranged for a bomb to be planted on Avianca Flight 203, a domestic passenger flight, as part of an assassination attempt against one of his political enemies, presidential candidate César Gaviria Trujillo. He missed the flight and avoided injury, but the bomb detonated and killed all 107 people on board.

Nine days after the airplane bombing, more than 50 people were killed and more than 2,200 were injured when a truck bomb detonated outside a DAS building in Bogotá, Colombia. The Medellín cartel was also believed to be responsible for this attack. Escobar’s terror eventually turned public opinion against him.

By the 1990s, Escobar was facing increasing pressure from the administration of President César Gaviria, particularly after Escobar’s alleged assassination of presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán in 1989. In June 1991, Escobar negotiated a surrendered to Gaviria’s government in exchange for a reduced sentence and preferential treatment during his captivity. A law at the time prevented his extradition to the United States.

Escobar built his own luxury prison called La Catedral , which was guarded by men he handpicked from among his employees. Often called “Hotel Escobar,” the prison came with a casino, spa, nightclub, football field, jacuzzi, waterfall, and giant doll house.

In June 1992, however, Escobar escaped when authorities attempted to move him to a more standard holding facility. A manhunt for the drug lord, with help from the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration, was launched that would last 16 months. During that time, the monopoly of the Medellín cartel, which had begun to crumble during Escobar’s imprisonment as police raided offices and killed its leaders, rapidly deteriorated.

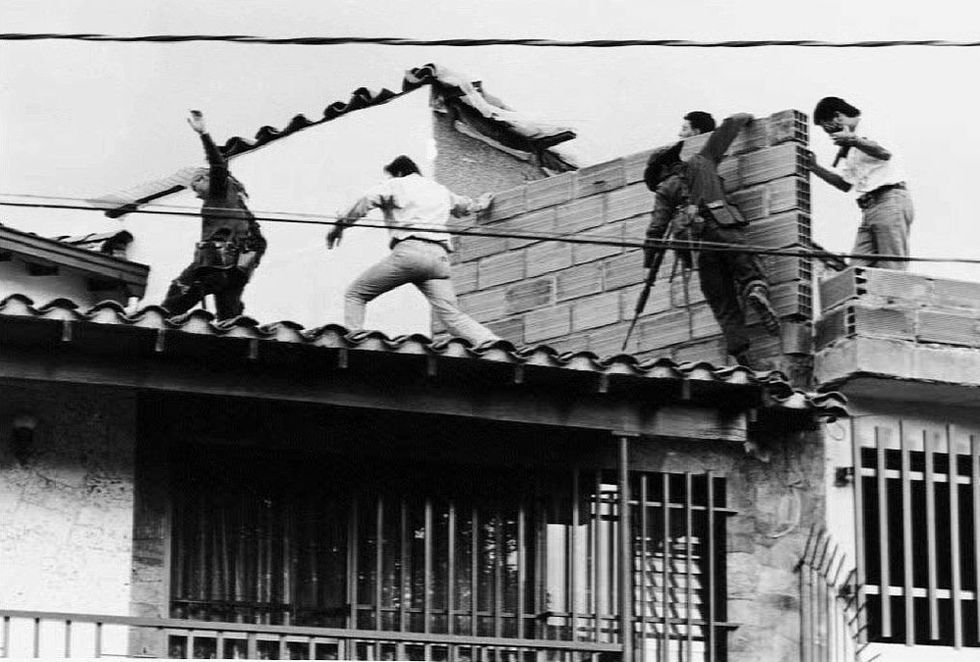

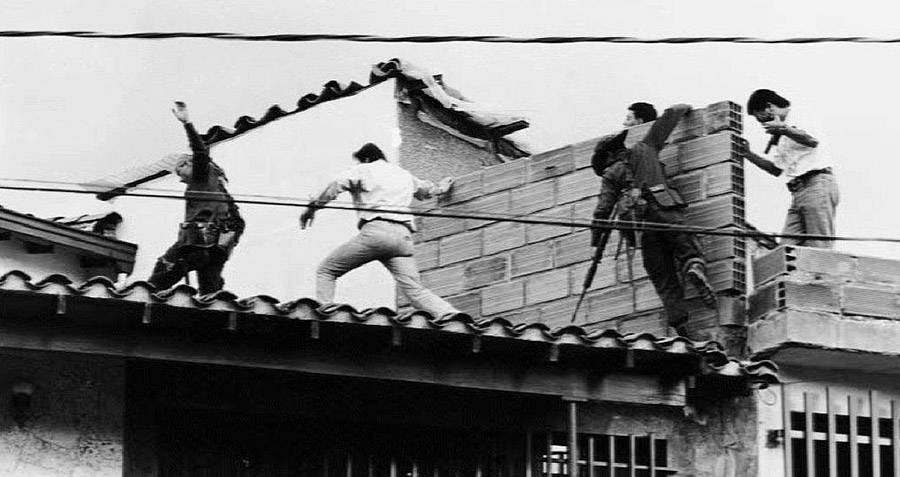

Escobar’s family unsuccessfully sought asylum in Germany and eventually found refuge in a Bogotá hotel. Escobar was not so lucky: Colombian law enforcement finally caught up to the fugitive Escobar on December 2, 1993, in a middle-class neighborhood in Medellín. A firefight ensued, and as Escobar tried to escape across a series of rooftops, he and his bodyguard were shot and killed. Escobar had just turned 44 years old the previous day.

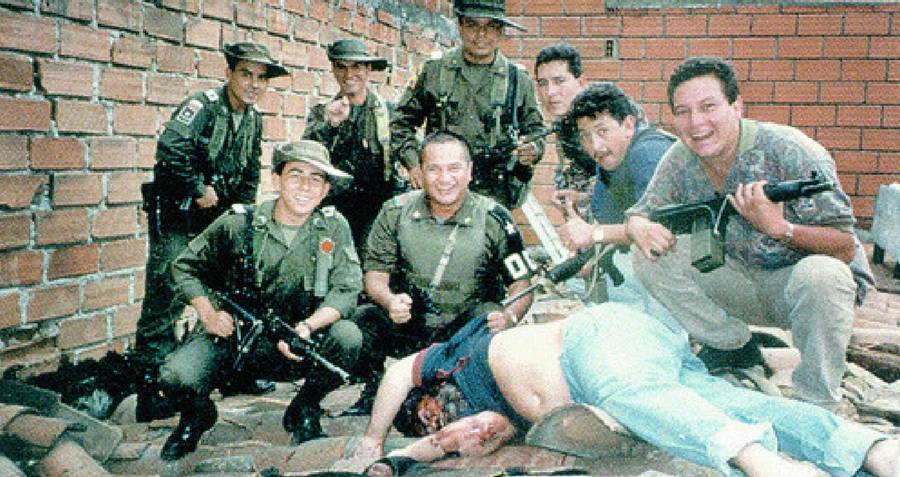

Escobar’s death accelerated the demise of the Medellín cartel and Colombia’s central role in the cocaine trade. His end was celebrated by the country’s government and other parts of the world, and his family was placed under police protection. Still, many Colombians mourned his killing. More than 25,000 people attended Escobar’s burial. “He built houses and cared about the poor,” one funeral-goer said at his funeral, according to The New York Times . “In the future, people will go to his tomb to pray, the way they would to a saint.”

In 1976, when he was 26, Escobar married 15-year-old Maria Victoria Henao. She was so young that before marrying her, Escobar had to get a special dispensation from the bishop, which was obtainable for a fee, according to Bowden. They were married until Escobar’s death. The couple had two children together: a son, Juan Pablo, and a daughter, Manuela.

Pablo Escobar: My Father

Today Escobar’s son is a motivational speaker who goes by the name Sebastian Marroquin. Marroquin studied architecture and published a book in 2015, Pablo Escobar: My Father , which tells the story of growing up with the world’s most notorious drug kingpin. He also asserts that his father was not shot and killed, but rather committed suicide.

“My father’s not a person to be imitated,” Marroquin said in an interview. “He showed us the path we must never take as a society because it’s the path to self-destruction, the loss of values, and a place where life ceases to have importance.”

Escobar has been the subject of several books, films, and television programs. Among them was the popular 2012 Colombian television mini-series Pablo Escobar: El Patron del Mal , which was produced by Camilo Cano and Juana Uribe, both of whom had family members who were murdered by Escobar or his assistants.

Escobar was also portrayed by Academy Award-winning actor Javier Bardem in the film Loving Pablo (2017), which also starred Penelope Cruz as his girlfriend Virginia Vallejo.

The 2015 Netflix television series Narcos was based upon the Escobar’s life, told largely from the perspective of Steve Murphy and Javier Peña , two American drug enforcement agents who worked on the Escobar case for years. In 2016, Escobar’s brother Roberto announced he was prepared to sue Netflix for $1 billion for its portrayal of his family in Narcos . He later abandoned those efforts.

- What is worth most in life are friends, of that I am sure. Unfortunately, along life’s paths one also meets people who are disloyal.

- In Colombia, people enter [drug trafficking] as a form of protest. Others enter it because of ambition.

- I want to be big.

- Better a tomb in Colombia than a prison cell in the United States.

- There have been many accusations, but I’ve never been convicted of a crime in Colombia.

- [Terrorism is] the atomic bomb for poor people. It is the only way for the poor to strike back.

Fact Check: We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn’t look right, contact us !

The Biography.com staff is a team of people-obsessed and news-hungry editors with decades of collective experience. We have worked as daily newspaper reporters, major national magazine editors, and as editors-in-chief of regional media publications. Among our ranks are book authors and award-winning journalists. Our staff also works with freelance writers, researchers, and other contributors to produce the smart, compelling profiles and articles you see on our site. To meet the team, visit our About Us page: https://www.biography.com/about/a43602329/about-us

Colin McEvoy joined the Biography.com staff in 2023, and before that had spent 16 years as a journalist, writer, and communications professional. He is the author of two true crime books: Love Me or Else and Fatal Jealousy . He is also an avid film buff, reader, and lover of great stories.

Watch Next .css-16toot1:after{background-color:#262626;color:#fff;margin-left:1.8rem;margin-top:1.25rem;width:1.5rem;height:0.063rem;content:'';display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;}

Gangsters, Mobsters, and Mafia Members

The “Cocaine Bear” Drug Smuggler Was a Real Person

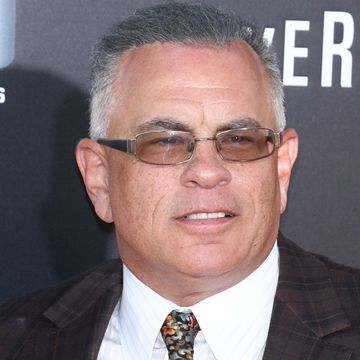

Junior Gotti

Donnie Brasco

Arnold Rothstein

Frank Lucas

Ronnie Kray

Sam Giancana

Meyer Lansky

Lucky Luciano

Bugsy Siegel

Biography of Pablo Escobar, Colombian Drug Kingpin

Colombian National Police/Wikimedia Commons/Public domain

- People & Events

- Fads & Fashions

- Early 20th Century

- American History

- African American History

- African History

- Ancient History and Culture

- Asian History

- European History

- Latin American History

- Medieval & Renaissance History

- Military History

- Women's History

- Ph.D., Spanish, Ohio State University

- M.A., Spanish, University of Montana

- B.A., Spanish, Penn State University

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria (December 1, 1949–December 2, 1993) was a Colombian drug lord and the leader of one of the most powerful criminal organizations ever assembled. He was also known as "The King of Cocaine." Over the course of his career, Escobar made billions of dollars, ordered the murders of hundreds of people, and ruled over a personal empire of mansions, airplanes, a private zoo, and his own army of soldiers and hardened criminals.

Fast Facts: Pablo Escobar

- Known For: Escobar ran the Medellín drug cartel, one of the largest criminal organizations in the world.

- Also Known As: Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria, "The King of Cocaine"

- Born: December 1, 1949 in Rionegro, Colombia

- Parents: Abel de Jesús Dari Escobar Echeverri and Hemilda de los Dolores Gaviria Berrío

- Died: December 2, 1993 in Medellín, Colombia

- Spouse: Maria Victoria Henao (m. 1976)

- Children: Sebastián Marroquín (born Juan Pablo Escobar Henao), Manuela Escobar

Watch Now: 8 Fascinating Facts About Pablo Escobar

Escobar was born on December 1, 1949, into a lower-middle-class family and grew up in Medellín, Colombia. As a young man, he was driven and ambitious, telling friends and family that he wanted to be the president of Colombia someday. He got his start as a street criminal. According to legend, Escobar would steal tombstones, sandblast the names off of them, and resell them to crooked Panamanians. Later, he moved up to stealing cars. It was in the 1970s that he found his path to wealth and power: drugs. He would buy coca paste in Bolivia and Peru , refine it, and transport it for sale in the United States.

Rise to Power

In 1975, a local Medellín drug lord named Fabio Restrepo was murdered, reportedly on the orders of Escobar himself. Stepping into the power vacuum, Escobar took over Restrepo’s organization and expanded his operations. Before long, Escobar controlled all organized crime in Medellín and was responsible for as much as 80 percent of the cocaine transported into the United States. In 1982, he was elected to Colombia’s Congress. With economic, criminal, and political power, Escobar’s rise was complete.

In 1976, Escobar married 15-year-old Maria Victoria Henao Vellejo, and they would later have two children, Juan Pablo and Manuela. Escobar was famous for his extramarital affairs and tended to prefer underage girls. One of his girlfriends, Virginia Vallejo, went on to become a famous Colombian television personality. In spite of his affairs, he remained married to María Victoria until his death.

Narcoterrorism

As the leader of the Medellín Cartel, Escobar quickly became legendary for his ruthlessness, and an increasing number of politicians, judges, and policemen publicly opposed him. Escobar had a way of dealing with his enemies: he called it plata o plomo (silver or lead). If a politician, judge, or policeman got in his way, he would almost always first attempt to bribe him or her. If that didn’t work, he would order the person killed, occasionally including the victim's family in the hit. The exact number of men and women killed by Escobar is unknown, but it certainly goes well into the hundreds and possibly into the thousands.

Social status did not matter to Escobar; if he wanted you out of the way, he'd get you out of the way. He ordered the assassination of presidential candidates and was even rumored to be behind the 1985 attack on the Supreme Court, carried out by the 19th of April insurrectionist movement, in which several Supreme Court justices were killed. On November 27, 1989, Escobar’s cartel planted a bomb on Avianca flight 203, killing 110 people. The target, a presidential candidate, was not actually on board. In addition to these high-profile assassinations, Escobar and his organization were responsible for the deaths of countless magistrates, journalists, policemen, and even criminals inside his own organization.

Height of His Power

By the mid-1980s, Escobar was one of the most powerful men in the world, and Forbes magazine listed him as the seventh richest. His empire included an army of soldiers and criminals, a private zoo, mansions and apartments all over Colombia, private airstrips and planes for drug transport, and personal wealth reported to be in the neighborhood of $24 billion. Escobar could order the murder of anyone, anywhere, anytime.

He was a brilliant criminal, and he knew that he would be safer if the common people of Medellín loved him. Therefore, he spent millions on parks, schools, stadiums, churches, and even housing for the poorest of Medellín’s inhabitants. His strategy worked—Escobar was beloved by the common people, who saw him as a local boy who had done well and was giving back to his community.

Legal Troubles

Escobar’s first serious run-in with the law came in 1976 when he and some of his associates were caught returning from a drug run to Ecuador . Escobar ordered the killing of the arresting officers, and the case was soon dropped. Later, at the height of his power, Escobar’s wealth and ruthlessness made it almost impossible for Colombian authorities to bring him to justice. Any time an attempt was made to limit his power, those responsible were bribed, killed, or otherwise neutralized. The pressure was mounting, however, from the United States government, which wanted Escobar extradited to face drug charges. He had to use all of his power to prevent extradition.

In 1991, due to increasing pressure from the U.S., the Colombian government and Escobar’s lawyers came up with an interesting arrangement. Escobar would turn himself in and serve a five-year jail term. In return, he would build his own prison and would not be extradited to the United States or anywhere else. The prison, La Catedral, was an elegant fortress which featured a Jacuzzi, a waterfall, a full bar, and a soccer field. In addition, Escobar had negotiated the right to select his own “guards.” He ran his empire from inside La Catedral, giving orders by telephone. There were no other prisoners in La Catedral. Today, La Catedral is in ruins, having been hacked to pieces by treasure hunters looking for hidden Escobar loot.

Everyone knew that Escobar was still running his operation from La Catedral, but in July 1992 it became known that the drug kingpin had ordered some disloyal underlings brought to his “prison,” where they were tortured and killed. This was too much for even the Colombian government, and plans were made to transfer Escobar to a standard prison. Fearing he might be extradited, Escobar escaped and went into hiding. The U.S. government and local police ordered a massive manhunt. By late 1992, there were two organizations searching for him: the Search Bloc, a special, U.S.-trained Colombian task force, and “Los Pepes,” a shadowy organization of Escobar’s enemies made up of family members of his victims and financed by Escobar’s main business rival, the Cali Cartel.

On December 2, 1993, Colombian security forces—using U.S. technology—located Escobar hiding in a home in a middle-class section of Medellín. The Search Bloc moved in, triangulated his position, and attempted to bring him into custody. Escobar fought back, however, and there was a shootout. Escobar was eventually gunned down as he attempted to escape on the rooftop. Although he was also shot in the torso and leg, the fatal wound passed through his ear, leading many to believe that Escobar committed suicide. Others believe one of the Colombian policemen fired the bullet.

With Escobar gone, the Medellín Cartel quickly lost power to its rival, the Cali Cartel, which remained dominant until the Colombian government shut it down in the mid-1990s. Escobar is still remembered by the poor of Medellín as a benefactor. He has been the subject of numerous books, movies, and television series, including "Narcos" and "Escobar: Paradise Lost." Many people remain fascinated by the master criminal, who once ruled one of the largest drug empires in history.

- Gaviria, Roberto Escobar, and David Fisher. "The Accountant's Story: inside the Violent World of the Medellin Cartel." Grand Central Pub., 2010.

- Vallejo, Virginia, and Megan McDowell. "Loving Pablo, Hating Escobar." Vintage Books, 2018.

- Why Did the Soviet Union Collapse?

- Fun Facts About the Channel Tunnel

- How the Channel Tunnel Was Built and Designed

- Otzi the Iceman

- Pakistani Martyr Iqbal Masih

- Chunnel Timeline

- Y2K and the New Millenium

- The Victims of the Columbine Massacre

- Nelson Rockefeller, Last of the Liberal Republicans

- History of the 1976 Olympics in Montreal

- How Alexander Fleming Discovered Penicillin

- The Story of Henri Charrière, Author of Papillon

- Biography of Lenny Bruce

- Biography of Saddam Hussein, Dictator of Iraq

- The Life of Zelda Fitzgerald, the Other Fitzgerald Writer

- Biography of Elvis Presley, the King of Rock 'n' Roll

Pablo Escobar Biography

Birthday: December 1 , 1949 ( Sagittarius )

Born In: Rionegro

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria often referred as the ‘King of coke’ was a notorious Colombian drug lord. He was considered as the most flagrant, influential and wealthiest criminal in the history of cocaine trafficking. The ‘Medellin Cartel’ was formed by him in collaboration with other criminals to ship cocaine to the American market. The 1970s and 1980s saw Pablo Escobar and the ‘Medellin Cartel’ enjoying near monopoly in the cocaine smuggling business in the U.S. shipping over 80% of the total drug smuggled in the country. He earned billions of dollars and by the early 90s his known estimated net worth was $30 billion. The earnings sum up to around $100 billion when money buried in various parts of Colombia are included. In 1989 Forbes mentioned him as the seventh wealthiest person in the world. He led an extravagant life with the fortune he made. His empire included four hundred luxury mansions across the world, private aircrafts and a private zoo that housed various exotic animals. He also had his own army of soldiers and seasoned criminals. While his vast empire was built on murders and crimes, he was known for sponsoring soccer clubs and charity projects.

Recommended For You

Nick Name: El Doctor, El Patrón, Don Pablo, El Señor

Also Known As: Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria

Died At Age: 44

Spouse/Ex-: Maria Victoria Henao

father: Abel de Jesús Dari Escobar

mother: Hemilda Gaviria

siblings: Roberto Escobar

children: Juan Pablo Escobar, Manuela Escobar

Born Country: Colombia

Gangsters Drug Lords

Height: 1.67 m

Died on: December 2 , 1993

place of death: Medellín, Colombia

education: University of Antioquia

You wanted to know

Who shot pablo escobar.

It is still not clear who actually fired the final shot into Pablo Escobar’s ear. There are various theories regarding this. Some believe that he was shot during the gunfight with the Colombian National Police or was possibly executed by them. But, Pablo Escobar’s brothers Roberto Escobar and Fernando Sánchez Arellano are of the view that Pablo Escobar committed suicide and he shot himself through the ear. They have said that Pablo Escobar had repeatedly told them that if ever he was cornered, he would 'shoot himself through the ear'.

Recommended Lists:

In ‘The Accountant's Story: Inside the Violent World of the Medellín Cartel’ Roberto Escobar discussed how an obscure and simple middleclass person like Pablo Escobar rose to become one of the richest men under the Sun.

Roberto Escobar used to keep track of all the money earned by Pablo Escobar as his accountant. At its peak when ‘Medellin Cartel’ smuggled 15 tons of cocaine daily to the U.S. worth over half a billion dollars, Pablo and his brother purchased rubber bands worth $1000 per week to wrap the cash bundles. About 10% of the money stored in their warehouses was lost every year due to spoilage by rats.

Pablo Escobar entered the drug trade in the 1970s and developed his cocaine operation in 1975. He himself used to fly a plane between Colombia and Panama for smuggling the drug to the U.S.

In 1975, after he returned to Medellin from Ecuador with a heavy load, he was arrested along with his men. Thirty-nine pounds of white paste was found in their possession. He failed in an attempt to bribe the judges of his case and later killed the two arresting officers resulting in dropping of his case. Soon he started applying his tactics of either bribing or killing to deal with the authorities.

Earlier, he used to smuggle cocaine in old tyres of planes and a pilot would receive $500,000 per flight. Later when its demand in the U.S. escalated, he arranged for additional shipments and alternative routes and networks including California and South Florida.

In collaboration with Carlos Lehder he developed Norman’s Clay in the Bahamas as the new island trans-shipment point. Between 1978 and 1982, this point remained the main route of smuggling for the Medellin Cartel’.

Pablo Escobar shelled out several million dollars and purchased 7.7 square miles of land which includes his estate ‘Hacienda Napoles’.

The mid-1980s saw him at the peak of his power smuggling about 11 tons of cocaine per flight to the U.S. According to Roberto Escobar, Pablo Escobar also employed two remote controlled submarines to smuggle cocaine.

In 1982, the ‘Colombian Liberal Party’ elected him to the ‘Chamber of Representatives of Colombia’ as an alternate member. He represented the Colombian government officially at the swearing ceremony of Felipe Gonzalez in Spain.

Another allegation against Escobar was that he backed the left-wing guerrillas of the ‘19th April Movement’ (M-19) who stormed the Colombian Supreme Court in 1985. Many of the judges on the court were murdered and files and papers were destroyed at a time when the court was considering Colombia’s extradition treaty with the United States The treaty would have allowed the country to extradite drug lords to the United States for prosecution.

As his network expanded and gained notoriety, he became infamous worldwide. By that time the ‘Medellin Cartel’ controlled a major portion of drug trafficking covering the United States, Spain, Mexico, Dominic Republic, Venezuela, Puerto Rico and other countries of Europe and America. Rumours that his network reached Asia were also doing the rounds.

His policy to deal with the Colombian system that encompassed intimidation and corruption was referred as ‘plata o plomo’. Though literally it means ‘silver or lead’ in his dictionary, it meant either accept ‘money’ or face ‘bullets’. His criminal activities included killings of hundreds of state officials, civilians and policemen and bribing politicians, judges and government officials.

By 1989 his ‘Medellin Cartel’ was in control of 80% of cocaine market in the world. It was generally believed that he was the chief financier of the Colombian football team ‘Medellín's Atlético Nacional’. He was also credited for developing multi-sports courts, football fields and aiding children’s football team.

Although he was considered an enemy of the Colombian government and the U.S., he was successful in creating goodwill among the poor people. He was instrumental in building schools, churches and hospitals in western Colombia and also donated money for housing projects of the poor. He was quite popular in the local Roman Catholic Church and the locals of Medellin often helped and protected him including hiding him from authorities.

His empire became so powerful that other drug smugglers gave away 20% to 35% of their profit to him for smooth shipment of their cocaine to the U.S.

In 1989, he was accused of getting Luis Carlos Galan, a Colombian presidential candidate, assassinated. He was also accused of the bombings at the ‘DAS Building’ in Bogota and at the Avianca Flight 203.

After the murder of Luis Carlos Galan the Cesar Gavitis led administration acted against him. The government negotiated with him to surrender on condition of a lesser sentence along with favourable treatment during his imprisonment.

In 1991, he surrendered to the Colombian government and was kept in La Catedral that was converted into a private luxurious prison. Before he surrendered the newly approved Colombian Constitution prohibited extradition of Colombian citizens which was suspected to be influenced by Escobar and other drug mafias.

On July, 1992, after finding that Pablo Escobar was operating his criminal activities from La Catedral, the government tried to shift him to a more conventional jail. However, he came to know of such plan through his influence and made a timely escape.

The U.S. ‘Joint Special Operations Command’ and ‘Centra Spike’ jointly started hunting him in 1992. ‘Search Bloc’ a special Colombian task force was trained by them for this purpose.

The ‘Los Pepes’ (Los Perseguidos por Pablo Escobar, "People Persecuted by Pablo Escobar") a vigilante group aided by rivals and former associates of Pablo Escobar executed a bloody carnage. This resulted in killing of around 300 relatives and associates of Escobar and destruction of huge amount of property of his cartel.

There was Co-ordination among ‘Search Bloc’, the Colombian and U.S. intelligence agencies and ‘Los Pepes’ through intelligence sharing so that ‘Los Pepes’ could bring down Escobar and his remaining few allies.

Pablo Escobar married Maria Victoria in March 1976. The couple had two children - Juan now known as Juan Sebastián Marroquín Santos and Manuela Escobar .

On December 2, 1993, after a fifteen month manhunt by ‘Search Bloc’, the Colombian and the U.S. intelligence agencies and the ‘Los Pepes’, he was found from his hiding and shot by the ‘Colombian National Police’. It still remains a mystery as to who shot him in his head as the relatives of Escobar believe that he shot himself to death.

Around 25,000 people attended his burial including most of the Medellin’s poor who were extensively aided by him. His grave rests at Itagui’s ‘Cemetario Jardins Montesacro’.

During 1990s, the government expropriated his luxurious estate ‘Hacienda Napoles’, the unfinished Greek-style citadel and the zoo under the law ‘extinción de dominio’ and handed them over to the low-income families. The property was reformed to a theme park encompassed by four luxury hotels alongside the zoo and a tropical park.

Pablo Escobar has remained a subject of several books, films, television shows, documentaries, music and even games.

See the events in life of Pablo Escobar in Chronological Order

How To Cite

People Also Viewed

Also Listed In

© Famous People All Rights Reserved

Sign Up Today

Start your 14 day free trial today

The History Hit Miscellany of Facts, Figures and Fascinating Finds

- 20th Century

Pablo Escobar: The Rise and Fall of the ‘King of Cocaine’

06 Nov 2023

In the annals of criminal history, the name Pablo Escobar looms large. A charismatic and ruthless Colombian drug lord, Escobar rose from humble beginnings to become the world’s most powerful and feared criminal. Yet, his meteoric rise was matched only by his cataclysmic fall.

Here we delve into the life and death of the infamous Pablo Escobar.

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria was born on 1 December 1949, in Rionegro, Antioquia in Colombia and came from a humble background. Raised in Medellín as the third of seven children, his father was a farmer and his mother worked as a teacher.

Early on, Escobar demonstrated his entrepreneurial spirit (and criminal tendencies), engaging in various schemes like selling fake diplomas, smuggling stereo equipment and selling stolen tombstones.

He left school in 1966 just before he turned 17, but returned two years later. His hard life on the streets of Medellín had shaped his teachers’ view of him, and a year later, Escobar dropped out of school again. Nevertheless, having forged a high school diploma, Escobar briefly studied in college with dreams of becoming a criminal lawyer, politician and even president, but gave up due to financial constraints.

Before long, he started stealing cars (resulting in his first arrest in 1974), and played a prominent role in controlling the smuggled cigarette market.

In the 1970’s, Colombia emerged as a key location for marijuana smuggling, and Escobar initially worked as a small-time marijuana dealer for various drug smugglers. (During this time, Escobar notably kidnapped businessman Diego Echavarria, later killing him in 1971, despite having received the $50,000 ransom.)

He gradually transitioned to the cocaine trade, recognising the immense profit potential due to Colombia’s strategic position between coca cultivation centres in the south, and the lucrative North American market.

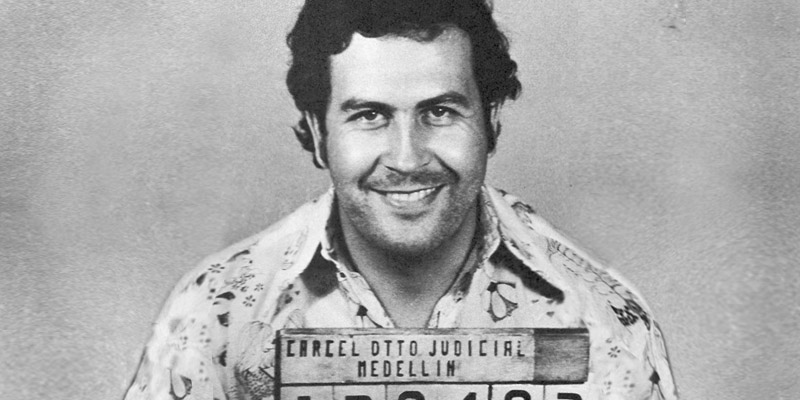

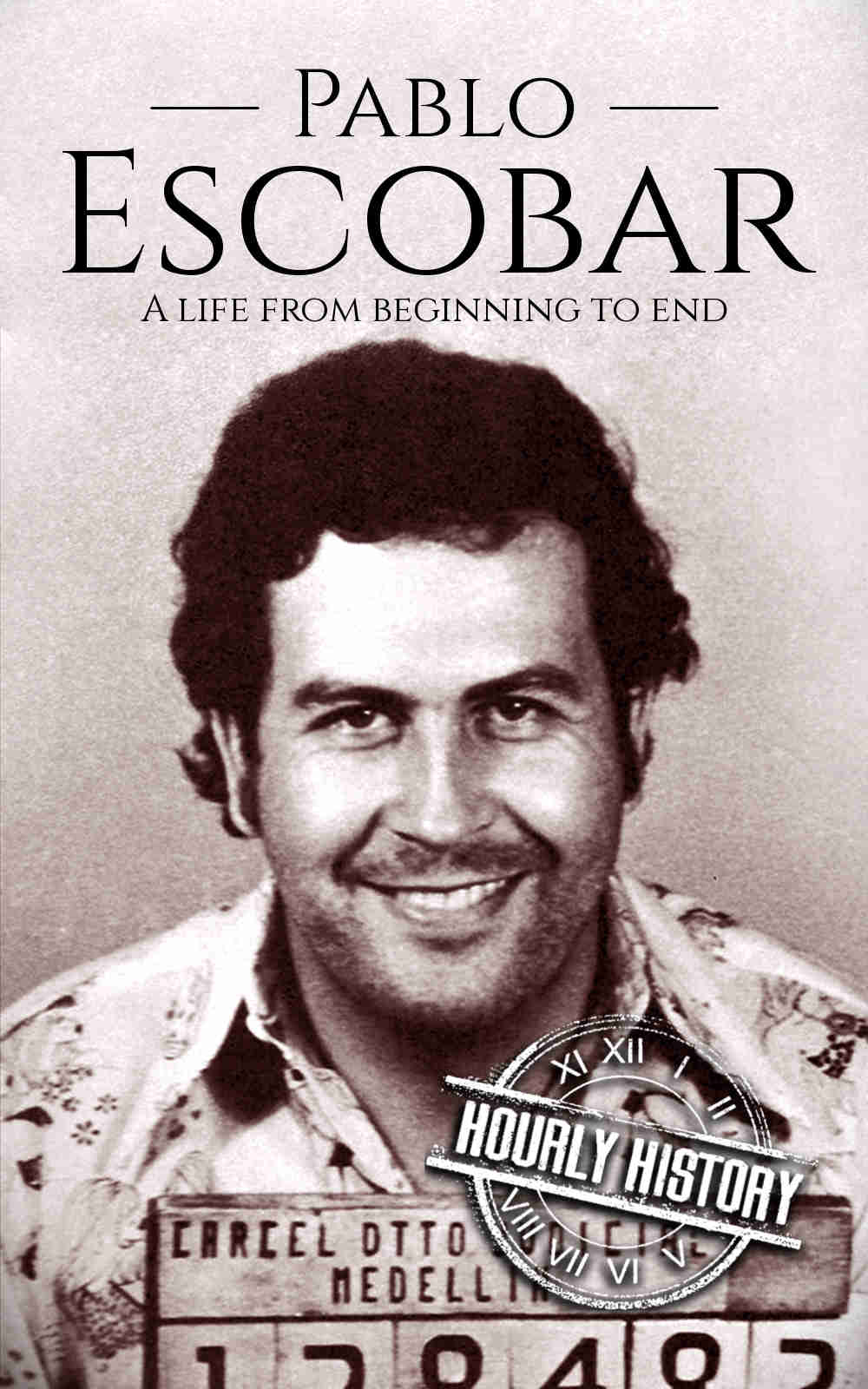

Pablo Escobar’s mugshot, taken by the regional Colombia control agency in Medellín in 1976

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons / Colombian National Police / Public Domain

Cocaine empire

Escobar’s ascent in the world of narcotics was spectacular. In 1976, he founded a criminal organisation that evolved into the infamous Medellín Cartel, a drug trafficking organisation based in Medellín, Colombia, which would go on to become one of the most powerful and influential criminal groups in history.

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, Escobar played a pivotal role in the ‘cocaine cowboy’ era in Miami. H is network of smugglers used ingenious methods to establish the first smuggling routes, transporting vast quantities of cocaine from Peru, Bolivia and Ecuador through Colombia and into America. This operation involved various means, from submarines to small aircraft landing in remote fields.

Escobar’s meteoric rise caught the attention of the Colombian Security Service, leading to his arrest in May 1976 when a significant amount of cocaine was discovered in his car. Managing to influence the legal process, he was released; the following year the agent who had arrested him was assassinated.

Escobar’s infiltration of the drug market created unprecedented demand for cocaine in America. Under his leadership, the Medellín Cartel came to dominate the global cocaine trade, controlling over 80% of the cocaine shipped to America. This immense operation earned him an estimated $420 million a week, and the nickname ‘The King of Cocaine’. By the 1980’s, the sheer volume of cocaine entering the US (approximately 70-80 tonnes per month) made Escobar one of the ten wealthiest people on the planet, with an estimated net worth of around $30 billion, according to Forbes .

Escobar’s vast wealth afforded him a lavish lifestyle, including private planes, a Caribbean getaway on Isla Grande, and numerous luxurious homes and safe-houses, including a 7,000 acre estate in Antioquia which he bought for $63 million. It was here he built his luxurious ranch, Hacienda Nápoles , which included a zoo featuring around 200 animals (including elephants, giraffes, and hippos), a lake, sculpture garden, air-strip, private bullring, football pitch, tennis court, artificial lakes, and numerous other amenities for his family and the cartel.

Escobar paid his staff generously, and gained a reputation for philanthropic efforts, spending millions developing some of Medellín’s most impoverished neighbourhoods, building housing, parks, football stadiums, hospitals, schools, and churches, leaving a complex legacy of both criminality and social investment.

By the late 1980s, Escobar’s wealth was such that he reportedly offered to pay off Colombia’s $10 billion debt in exchange for exemption from any extradition treaty. During his final years on the run, he famously reportedly burned $2 million to keep his daughter warm.

Entrance to Hacienda Nápoles, the luxurious estate built and owned by Pablo Escobar in Puerto Triunfo, Antioquia Department, Colombia

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons / XalD / CC BY 3.0

‘Plata o plomo’

Escobar’s dominance of the cocaine trade was characterised by corruption, intimidation, and violence. His guiding principle was ‘plata o plomo’ (‘silver or lead’) – effectively meaning ‘bribes or bullets’. Throughout his reign, he systematically bribed and intimidated Colombian law enforcement agencies, public officials and political candidates.

The financial backing provided by both the Medellín Cartel and its rival, the Cali Cartel, to political candidates had a profound impact on Colombian politics. These cartels were able to exert influence at every level of government, enabling them to manipulate political processes, bribe politicians, and effectively control the political landscape.

The Medellín Cartel was not only engaged in a battle against rival drug cartels, but also resorted to a reign of terror when Escobar introduced the concept of ‘narco-terrorism’, employing tactics such as bombings, assassinations, and extortion to maintain control over Colombia and to intimidate rivals and enemies. The Medellín Cartel’s ruthlessness knew no bounds, operating with total impunity.

Escobar’s criminal empire resulted in the deaths of around 4,000 people who dared to challenge his reign, including police officers, government officials, journalists, and judges. Under his influence, Colombia became the murder capital of the world, marked by unimaginable violence and corruption.

In the 1980s, Escobar’s influence and popularity amongst many Colombians prompted him to enter politics, where he played a significant role in the formation of the Liberal Party of Colombia. He was elected to an alternate sea in the country’s Congress in 1982, and in this capacity, further developed community projects, earning him popularity and support among the local population in the areas he frequented. Now a public figure, his philanthropic efforts led to his nickname as a modern-day ‘ Robin Hood Paisa’ .

Escobar’s political position granted him parliamentary immunity and a diplomatic passport. However, his political career faced opposition when t he new Minister of Justice, Rodrigo Lara-Bonilla, accused him of criminal activities. Lara-Bonilla launched an investigation into Escobar’s 1976 arrest, and a few months later, Liberal leader Luis Carlos Galán expelled Escobar from the party.

Although Escobar fought back, after a campaign to expose his criminal activities he announced his retirement from politics in January 1984. Three months later, Lara-Bonilla was assassinated. Escobar’s political ambitions were further thwarted by the Colombian and America governments, who continually pushed for his arrest and extradition to America.

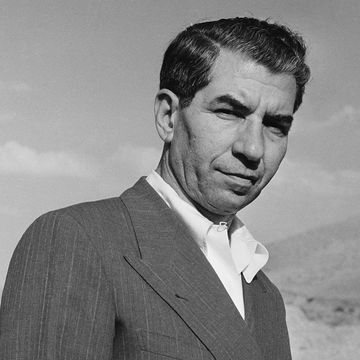

Left: Pablo Escobar Gaviria, circa (1984). Right: Justice Minister Rodrigo Lara (centre) and presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán (left) were both assassinated by orders of Escobar

Image Credit: Left: Alamy / The Hollywood Archive. Right: Wikimedia Commons / Flickr.com/people/ivanmarulanda/ CC BY 2.0

Fight against extradition and ‘narco-terrorism’

In the mid-1980s, Escobar waged a campaign against the Colombian judiciary, bribing and murdering several judges to further his objectives. In 1985, Escobar requested the Colombian government allow his conditional surrender without extradition to America.

When this was denied, Escobar founded the Los Extraditable Organisation to fight extradition policies. This organisation was subsequently implicated in obstructing the Colombian Supreme Court from studying the constitutionality of Colombia’s extradition treaty with America.

In retaliation, the Colombian Judiciary Building was attacked, resulting in the deaths of half of the Supreme Court’s justices. The violence escalated, leading the Supreme Court to subsequently declare that the previous extradition treaty was illegal in late 1986 because it had been signed by a presidential delegation, not the president.

However, Escobar’s victory over the judiciary was short-lived, as the new Colombian president, Virgilio Barco Vargas, promptly renewed the extradition agreement with America.

Escobar’s grudge against Luis Carlos Galán, who had removed him from politics, led to Galán’s assassination in August 1989. In further retaliation, one of Escobar’s most notorious acts of narco-terrorism included his alleged orchestration of the bombing of Avianca Flight 203 in 1989, which killed all 107 people on board in an attempt to assassinate Galán’s successor, César Gaviria Trujillo. Gaviria missed the plane and survived. Escobar’s involvement in this, as well as the bombings of DAS (Department of Security) buildings, prompted direct US government intervention due to the killing of two Americans in the Avianca bombing.

La Catedral

The US government recognised the grave threat posed by the Medellín Cartel and initiated a massive effort to apprehend Escobar and dismantle his cartel empire. American and Colombian authorities cooperated extensively in an unprecedented manhunt, spanning years and involving multiple countries.

The newly approved Colombian Constitution of 1991 prohibited the extradition of Colombian citizens to America. However, this was a controversial act, as it was suspected that Escobar and other drug lords had exerted influence over members of the Constituent Assembly to pass the legislation.

Nevertheless, later that year , Escobar negotiated with the government, offering to turn himself in to authorities and cease all criminal activity in exchange for a reduced sentence of five years’ imprisonment, and preferential treatment during this captivity. Colombian officials agreed to the terms, and Escobar was housed in his own, luxurious, self-built private prison, La Catedral . This ‘prison’ featured a football pitch, giant dollhouse, nightclub, bar, jacuzzi, sauna, and even a waterfall.

The bedroom of the luxurious private prison, La Catedral, where Pablo Escobar was confined

The kingpin’s fall

Despite this highly reasonable deal, reports emerged that Escobar had tortured and killed two cartel members while at La Catedral , prompting the government’s decision to move him to a more conventional jail on 22 July 1992. However, Escobar’s influence had enabled him to discover the plan in advance, and he successfully escaped, abandoning his opulent lifestyle and living in hiding while on the run as a fugitive.

This led to a nationwide manhunt; Escobar faced threats from the Colombian police, the US government, and the rival Cali Cartel – leading to the Medellín Cartel’s downfall. A period of intense surveillance and tracking culminated in a large-scale operation on 2 December 1993 when Colombian special forces, with technological assistance from America, located Escobar’s hideout in a middle-class neighbourhood in Medellín.

An attempt to arrest Escobar quickly escalated, leading to gunfire exchanges. In the end, authorities stormed the building, resulting in the death of Pablo Escobar and his bodyguard as they tried to escape from the rooftop. Escobar sustained multiple gunshot wounds, including one to the head. This prompted speculation that Escobar had killed himself, especially as he had once expressed a preference for a grave in Colombia over a jail cell in America.

Nevertheless, his death, one day after his 44th birthday, marked the end of an era.

Pablo Escobar’s legacy continues to loom large – not only as a notorious criminal but as a cultural phenomenon.

While many decried the heinous nature of his crimes, in Colombia, he was perceived by some as a Robin Hood-like figure, particularly in Medellín, where he was credited with providing amenities to the city’s poor that the government had not. Indeed Escobar’s funeral drew over 25,000 people, and his memory remains influential.

His former private estate, Hacienda Nápoles , was given to low-income families by the government, and also converted into a theme park surrounded by four luxury hotels overlooking Escobar’s zoo. (Most of the zoo’s animals were transferred to other zoos, yet 4 hippos were left behind. By 2014, 40 hippos were reported to exist in the area, and by 2021, Colombian authorities began a chemical sterilisation program to control the hippo population.)

The city of Medellín, Colombia, where Escobar grew up and began his criminal career

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons / seth pipkin 2007 / CC BY-SA 2.0

Escobar’s life story has been the subject of numerous books, films, and television series, most notably Narcos , serving as a cautionary tale about the immense power organised crime can amass, the devastating consequences and effects of the drug trade, the corruption it breeds, and its tragic human cost.

Although Escobar’s death marked the end of his reign, it did not signal the end of the drug trade, or its challenges. The Cali Cartel dominated the cocaine market in the years following Escobar’s demise. In Colombia, memories of Escobar’s reign of terror remain vivid. While Colombia has made significant progress in curbing drug violence and improving security since his death, the drug trade and associated violence have not been entirely eradicated, and challenges persist.

In America, the pursuit and eventual downfall of Pablo Escobar represented a turning point in the fight against drug cartels, underscoring the importance of international cooperation in addressing transnational crime, and laying the groundwork for further efforts to combat the drug trade .

You May Also Like

3 Things We Learned from Meet the Normans with Eleanor Janega

Reintroducing ‘Dan Snow’s History Hit’ Podcast with a Rebrand and Refresh

Don’t Try This Tudor Health Hack: Bathing in Distilled Puppy Juice

Coming to History Hit in August

Coming to History Hit in September

Coming to History Hit in October

The Plimsoll Line: How Samuel Plimsoll Made Sailing Safer

How Polluting Shipwrecks Imperil the Oceans

How Cutty Sark Became the Fastest Sail-Powered Cargo Ship Ever Built

Why Did Elizabethan Merchants Start Weighing Their Coins?

‘Old Coppernose’: Henry VIII and the Great Debasement

The Royal Mint: Isaac Newton and the Trial of the Pyx Plate

Encyclopedia of Humanities

The most comprehensive and reliable Encyclopedia of Humanities

Pablo Escobar

We discuss the life of Pablo Escobar and his initiation into crime. In addition, we explain why he is considered one of the greatest criminals in history.

Who was Pablo Escobar?

Pablo Escobar was a Colombian criminal and drug trafficker, founder and leader of the criminal organization known as the Medellín Cartel. Dubbed the "King of Cocaine", in his short lifespan of just 44 years, he was the world's leading drug trafficker during the 1980s, managing to amass a fortune estimated at 30 billion dollars .

At the height of his criminal empire, Escobar led an extravagant lifestyle, owning a 2,800-hectare estate called " Hacienda Nápoles " ("Naples Estate" in Spanish), on which he had artificial lakes, a landing strip, a zoo, a bullring, and life-sized dinosaur statues.

He also established various philanthropic and social assistance organizations that earned him a Robin Hood-like image , so much so that he managed to secure a seat in the nation's congress in 1982.

However, Escobar's infamous ruthlessness was widely widespread among his acquaintances and collaborators: he was known for solving problems with " plata o plomo " (literally "silver or lead", meaning money or death). In 1989, he was the mastermind behind the bombing of an airplane, which killed around 100 people.

Killed by the police in 1993, his figure has become part of contemporary urban mythology and has been a source of inspiration for literature works and film.

- See also: Fidel Castro

Early life of Pablo Escobar

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria was born on December 1, 1949, in the town of Rionegro, in the Colombian state of Antioquia. He was the second of seven children of a humble household born to farmer Abel de Jesús Escobar Echeverri and schoolteacher Hermilda de los Dolores Gaviria Berrío.

Shortly after Pablo's birth, the family moved to Envigado, in the suburbs of Medellín, Colombia's second largest city. There, Pablo grew up and soon his leadership skills and his knack for business became evident: together with his cousin Gustavo Gaviria, they organized raffles, traded magazines, and made low-interest money loans.

Eventually, Pablo was elected as president of the Student Welfare Council, managing to gain access to school information, such as exams. Teachers recall him as a quiet boy, obsessed with his appearance and with a complex about his height . During this period, Pablo came into contact with the revolutionary left. Many of his former peers took up armed struggle. According to them, Pablo sympathized with the leftist imaginary, while at the same time he dreamed of amassing a true fortune .

In 1969, he completed his high school education at the Lucrecio Jaramillo Vélez high school and was admitted to the Economics program at the Universidad Autónoma Latinoamericana of Medellín. However, he soon lost interest in university studies and preferred to engage in illicit businesses. He would allegedly have sworn to commit suicide if he did not have a million pesos at his disposal by the age of 25 .

Beginnings in the drug trafficking

Since he moved to Medellín, Pablo had been in contact with other young people from the poorest neighborhoods. Among them were the sons of the wealthy Henao family: Mario, Carlos and Fernando, and his own cousin Gustavo. As teenagers, Pablo, Mario and Gustavo became friends and partners in crime , including the forgery of diplomas, the smuggling of sound equipment, and the theft of aluminum tombstones.

This trio of young criminals attracted the attention of local organized gangs, among them that of Diego Echavarría Misas, a famous smuggler, and later Alfredo Gámez López, dubbed the "Padrino" (the "Godfather"), the country's leading smuggler. By then, Pablo and his accomplices had already become skilled car thieves .

Initially acting as bodyguards and hit men, soon the "Godfather" Gámez López sent them on a trip to buy coca paste in Peru and Ecuador, for later processing in Colombia. This was how they entered drug trafficking. Those were the years of the "Marimba Bonanza" , and thousands of dollars were flowing into Colombia from the export of marijuana to the US.

Around that time, they also became acquainted with smugglers Elkin Correa and Jorge Gonzalez. From them, Pablo learned the smuggling routes and established important connections in the drug world , which would later prove very useful in founding the Medellín Cartel. Pablo's steely resolve, his ruthless personality, and the fact that he did not consume cocaine made him very popular within the organization.

On June 9, 1976, Pablo and Gustavo were arrested for the first time near Medellín, transporting a shipment of 20 kilograms of cocaine hidden in the wheels of their car. They were released after a few months in prison.

The " bonanza marimbera " ("marimba bonanza") was the name given to the influx of millions of dollars from drug trafficking into Colombia between 1974 and 1985 from the illegal export of marijuana to the United States. This "bonanza" proved of great importance for the growth of local drug cartels, ending in the mid-1980s, when marijuana cultivation in Colombia was largely replaced by cocaine.

Marriage to "La Tata"

At the age of 24, Pablo met Victoria Henao Vallejo, a sister of his associate Mario, and declared his love for her . At that time, the young woman was 13 years old. Despite her family's opposition, Pablo and Victoria got married two years later . In 1977, Juan Pablo was born, and in 1984, Manuela. The couple remained together until Pablo's death.

Following Pablo's death, Victoria and her children had to flee Colombia. Since almost no country accepted them, they emigrated to Mozambique, where they lived in very harsh conditions.

Eventually, they legally changed their names and emigrated to Buenos Aires, where they were victims of extortion by an accountant who knew their real identities. They were imprisoned, being released eighteen months later, thanks to the mediation of Nobel Peace Prize winner Adolfo Pérez Esquivel.

Shortly after Pablo's marriage, "Padrino" Gámez López was denounced and investigated by the Colombian state, and ended up in jail on two occasions. His contacts in politics, however, helped him serve just one year in prison before retiring to the Caribbean city of Cartagena.

From then on, many minor players were in charge of the drug business. In 1977, they all came together in a single organization, which in 1982 was given the name of the cartel de Medellín (Medellín Cartel). Pablo Escobar was among its founders and became the head of the organization , which was responsible for the production, distribution, and sale of 80% of the cocaine consumed in the United States.

Medellín Cartel

Since its origin, the Medellín Cartel had a hierarchical and well-organized structure, which allowed its associates to share resources , carry out operations, and yet maintain their production centers and business separate.

"Medellín Cartel" was named by the United States Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), since it was based in the city of Medellín. The cartel's boom took place in the 1980s, as cocaine consumption took hold in the United States, with Colombia becoming its major supplier .

To establish its dominance, the cartel resorted to murder, corruption, and bribery. Escobar, at the head of this criminal organization, imposed the so-called "silver or lead law" , according to which the cartel offered government officials money in exchange for their favors, or else their lives and their families were under threat if they refused the bribe.

Eventually, the cartel resorted to terrorism and armed confrontation, both with state forces and with the rival cartel, based in Cali. This sparked a bloody "cartel war" that lasted from 1986 to 1993 .

The "Cali Cartel," so named by the DEA, was led by brothers Gilberto and Miguel Rodriguez Orejuela, as well as José Santacruz Londoño and Hélmer Herrera Buitrago. It was also known as "The Cocaine Inc.", "The lords of Cali", or "The Cali KGB".

Pablo Escobar and politics

By the age of 29, Pablo Escobar had already amassed a considerable fortune . He was dubbed " El Patrón " (The Boss) by members of the cartel. It was then that he decided it was time to have a front, or as he called it, "a screen," which would allow him to appear openly in public. And so it was that Pablo Escobar entered the world of politics .

Presenting himself as a philanthropist, he began to show himself publicly with lawyers, financiers, politicians, and to cultivate an image of a successful man . He soon began the construction of facilities intended for the lower classes of Medellín, such as sports stadiums and even an entire neighborhood called " Medellín sin tugurios " (Medellín without slums), which later became known as " Barrio Escobar ". These types of actions earned him the affection of the popular classes, while also the accusation of populism.

At the same time, Escobar embarked on a life of excess and eccentricities. He invested 62 million dollars to buy and develop a plot of land in Puerto Triunfo, 112 miles (180 km) from Medellín . There, he established his luxurious " Hacienda Nápoles ", which featured a private landing strip and a hangar for airplanes, motorcycles, vans and other vehicles, a gas station, a bullring, a stable, a medical center, dinosaur statues, and a zoo with exotic animals like camels, elephants, rhinoceroses, moose, and hippos.

"Nápoles" was open to visitors during the weekend, as Escobar considered that it also belonged to the Colombian people. The estate also hosted large celebrations.

Through corruption, extortion and hired killings, Escobar managed to gain a significant amount of political, economic, military, and even religious influence, as despite his criminal record, he never ceased to be a devout Catholic .

In this way, Escobar managed to register in the Nuevo Liberalismo (New Liberalism) party, from which he was later expelled. Later, he managed to get himself elected, through various ruses, as an alternate senator to the Senate for Alternativa Liberal (Liberal Alternative movement) in the 1982 parliamentary elections.

However, Escobar's "screen" began to fracture around 1983 when investigations into his fortune began under Justice Minister Rodrigo Lara Bonilla (1946-1984), who was part of the Belisario Betancur administration. The investigation of dirty money in Colombian soccer and politics, as well as the reopening of old legal cases against Escobar, allowed Lara to seize planes and properties used in drug trafficking, and to expose jungle labs dedicated to cocaine production. Thus, not only was Escobar's election to parliament questioned, but the origin of the money that financed him was exposed , and the truth was spread by the El Espectador newspaper.

Escobar and his allies attempted to tarnish the minister's reputation by fabricating evidence incriminating him in corruption, but to little avail. In the end, on April 30, 1984, Lara Bonilla was gunned down by Escobar's hit men as he was driving through the streets of Bogotá . This assassination prompted the president to pass an Extradition Law to the United States and declare martial law, which marked the beginning of the war against narcoterrorism in Colombia.

War against narcoterrorism

By 1984, Escobar's political career was over. The revelations in El Espectador had cost him his seat in parliament and his US visa, prompting him to retire from public life. Shortly after, arrest warrants were issued for the leaders of the Medellín Cartel, and Escobar was forced into hiding .

That same year, police forces, in conjunction with the US DEA, discovered and raided a complex of cocaine processing laboratories near the Yari River, known as Tranquilandia . It was a major blow to Escobar's operations , and the cartel responded by unleashing a wave of terror: car bombs, assassinated journalists, and shot judges became daily news.

Many politicians and officials, bought or threatened by Escobar, allowed the organization to act with impunity, even though its leaders, then dubbed " los extraditables " (the extraditable ones), were already publicly known. At the same time, the Medellín Cartel secured international allies. They already had the support of similar organizations in Mexico, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Cuba .

Until then, Escobar and his allies controlled 90% of Colombia's drug trade but had good relations with rival cartels. However, after the assassination of Minister Lara, a crime the Cali Cartel considered counterproductive, starting in 1986 tensions between the two cartels led to a new escalation of violence: the cartel war .

War between cartels

The break between the two major Colombian drug cartels occurred under circumstances that remain unknown . According to Jhon Jairo Velásquez "Popeye," one of the most notorious hit men for the Medellín Cartel, tensions flared when one of Escobar's most loyal men asked him to carry out a personal vendetta against a member of the Cali Cartel, known as "Piña."

"Piña" was protected by Helmer "Pacho" Herrera, the fourth in command of the Cali Cartel, who did not take kindly to Escobar's request to hand over his subordinate. When Escobar's request was ignored, the boss ordered the kidnapping and execution of "Piña," triggering the break between the two organizations .

In addition to fighting each other, the cartels contributed to the capture of rival leaders at the hands of the police. In this context, in 1987, Escobar lost two of his closest associates . In February Carlos Lehder was arrested, and in November, Jorge Luis Ochoa. Ochoa, however, was released after a riot in La Modelo prison.

Early the following year, a car carrying 154 pounds (70 kg) of dynamite exploded in front of the Monaco building, where the Escobar family lived . There were no fatalities, but the building was severely damaged, and although the Cali Cartel denied involvement, Escobar considered this event a formal declaration of war.

From then on, Escobar launched an offensive against the operations of his Cali rivals . In 1988, he set fire to and dynamited dozens of properties owned by the Rodríguez Orejuela family and began an espionage operation against them.

Terror years

The year 1989 was one of the bloodiest in the conflict between the cartels and the state.

At the end of 1988, the secretary general of the Colombian presidency, Germán Montoya, had attempted to approach the group of " los Extraditables ", opening the possibility of dialogue. The Medellín Cartel then proposed to the state to grant them legal pardon and a demobilization plan to put an end to the conflict . The initiative was unsuccessful, largely due to the United States' refusal to negotiate with the criminals.

The Medellín Cartel was quick to respond, assassinating judges, government officials, and Colombian public figures. The bloodshed included the bombing of the Mundo Visión television station and the murder of presidential candidate Luis Carlos Galán , an enemy of drug trafficking and the person who had the best chance of being elected.

Galán's assassination spurred the Colombian state to declare war on narcoterrorism. Through new decrees, President Virgilio Barco Vargas approved special measures (some even contrary to the National Constitution) for the persecution and treatment of drug traffickers.

These measures included expedited extradition to the United States, the confiscation of drug traffickers' personal assets, and the creation of the Elite Group, composed of 500 specially trained agents to deal with " Los Extraditables " . In the days that followed, the government carried out about 450 raids and arrested nearly 13,000 people linked to drug trafficking.

The Medellín Cartel responded with a declaration of total war. Between September and December of 1989, more than 100 explosive devices detonated in the cities of Bogotá, Medellín, Cali, Bucaramanga, Cartagena, Barranquilla, and Pereira. In addition to the acts of hired assassination, there were an estimated 300 terrorist attacks during those three months , resulting in a toll of nearly 300 civilian deaths and over 1,500 wounded.

However, the Colombian state did not give in. In November 1989, Escobar was close to being captured in an operation at the El Oro estate in Antioquia , where his brother-in-law Fabio Henao was killed and 55 of his men were captured. Later, on December 15, 1989, the second in command of the Medellín Cartel, the "Mexican" Rodríguez Hacha, was shot by the police on the country's north coast , along with his son and bodyguards.

As the noose tightened around them, "Los Extraditables" announced another call for dialogue with the government, first kidnapping the son of the secretary of the presidency, Álvaro Diego Montoya, and two relatives of President Barco. A brief truce ensued, and in the early 1990, a committee of Colombian notables was formed to negotiate with the narcoterrorists .

Escobar and his associates responded by releasing the hostages to show a genuine willingness for dialogue . In addition, they handed over a bus full of explosives and revealed the location of one of their clandestine laboratories in the town of Chocó. But the dialogue was in fact a ploy to buy time while initiating a large-scale operation in Envigado, Antioquia.

On March 30, the cartel ended the truce. Escobar put a price on the life of every police officer the criminals killed , unleashing an urban war that by the end of July had left hundreds dead and injured, including Senator Federico Estrada Vélez.

Government forces also committed excesses: in retaliation for the murder of nearly 215 police officers between April and July of 1990, their death squads carried out clandestine executions in the slums every night .

That same year in June, Escobar's military leader, John Jairo Arias Tascón, alias "Pinilla", was assassinated. Following an operation in Magdalena from which Escobar miraculously managed to escape again, the cartel announced a new truce in combat, just in time for the election of the new government of César Gaviria .

Imprisonment of Pablo Escobar

The new Colombian administration seemed willing to end the conflict as soon as possible. On August 11, the Elite Group killed Gustavo Gaviria Rivero, " El León ," cousin and right-hand man of Pablo Escobar, in a shootout . The "patrón" began to lose his most reliable associates.

At the same time, Justice Minister Jaime Giraldo Ángel announced a legislative plan to facilitate the surrender of narcoterrorists, offering a reduction in their sentences and imprisonment in Colombia (the narcos feared extradition to the United States, above all) in exchange for voluntary surrender and confession of at least one crime committed.

The Ochoa brothers were the first of Escobar's high-level henchmen to accept the offer, between December 1990 and February 1991 . The patrón, distrusting the government's word, began a series of selective kidnappings.

Several of these captives died in rescue attempts or were executed in retaliation for the government's actions. Escobar's idea was to pressure the government to design a plan tailored to his needs. But in the absence of a response, he resumed his methods of terrorism: between December 1990 and the early months of 1991, at least 44 people were killed in bombings and shootings , including former Justice Minister Enrique Low Murtra.

Eventually, the government had no choice but to give in to Escobar's demands. In June 1991, the boss of the Medellín Cartel surrendered to justice, to be confined in La Catedral prison in Envigado . From there, he continued to control his illegal operations remotely, thanks to his two associates in hiding: Fernando " El Negro " Galeano and Gerardo "Kiko" Moncada.

During his imprisonment, Escobar was attended to by his wife, " La Tata ," and was in constant contact with his henchmen. He received many messages and documents in his room. At La Catedral he received visits from celebrities, beauty queens, and soccer players .

The room where Escobar was held at La Catedral was akin to a five-star hotel suite : a large bed, cozy decoration, TV sets, video and music players, imported furniture, a personal library, and carpeted floors. The prison also had pool rooms, a bar, and a soccer field. Parties, orgies, and business meetings were held nearby, as Escobar continued to lead his criminal operation from jail. The prison itself, as was later discovered, had been commissioned by Escobar himself on land that belonged to him.

In 1992, Escobar's actions became public knowledge, and the Gaviria government decided to transfer him to a "real prison" . Aware of the decision, Escobar planned his escape with the assistance of his henchmen, and on July 22, he escaped by breaking through a plaster wall at the back of the prison.

Escobar's escape was a serious blow to the Gaviria government and the Colombian justice system . The creation of a "Search Bloc" composed of the police, the army, and the US DEA was immediately announced, and a reward of 2.7 billion pesos was offered for information leading to the "patrón's" capture .

Death of Pablo Escobar

Pablo Escobar's return to freedom was marked by a reality that was very different from the one he had left before his surrender. A fracture was growing in the Medellín Cartel and sectors opposed to his leadership eventually allied with his enemies in Cali . This broad alliance against him ended in October 1992 with one of his last military leaders, Brances Alexander Muñoz, alias "Tyson".

The resources of the Medellín Cartel began to dwindle, and their actions became more desperate. Car bombs exploded in Bogotá, Barrancabermeja, and other cities, killing civilians and officers indiscriminately. Escobar sought to renegotiate his surrender and authorized the delivery of some of his most trusted associates , but in response, actions against him intensified.

On January 30, 1993, a new actor joined the conflict: the paramilitary gang of "Los pepes" (acronym for "Perseguidos Por Pablo Escobar"), dedicated to pursuing and killing Escobar's front men, collaborators and cover-ups.

By March 1993, around 100 hit men and 10 of the cartel's military leaders had been killed, and nearly 1,900 collaborators arrested. Meanwhile, 300 other " gatilleros " (hired gun thugs) had been gunned down by rival gangs.

Escobar's wife and children had unsuccessfully sought asylum in the United States and Germany and lived under police surveillance, so they were used as bait by the authorities. On December 2, 1993, after 17 months of intense search, Escobar was cornered by the police in the middle-class neighborhood of Los Olivos, in Medellín .

There, the last of his hit men, Jesús Agudelo, alias "Limón", was killed, and Escobar tried to escape through the roofs of the neighboring houses, but he was shot three times and died on the spot . His death marked the end of the Medellín Cartel and was photographically recorded by the Search Bloc. He was 44 years old.

The next day, his death was announced as a major victory in the fight against drug trafficking. His family mourned his death along with thousands of supporters from the lower classes, who still paradoxically expressed their gratitude. His coffin was accompanied to the Montesacro Gardens cemetery in Itagüí by a massive procession .

This duality of his image made him both an infamous criminal and a popular hero. His life of violence and eccentricities has served as inspiration for numerous newspaper reports and fiction series.

Explore next:

- Che Guevara

- Adolf Hitler

- Octavio Paz

- Palacios, R. (2022). “Celda cinco estrellas, reinas de belleza y orgías: la vida de Pablo Escobar en la cárcel que mandó a construir”. Infobae .

- Salazar, A. (2012). La parábola de Pablo . Penguin Random House.

- Rockefeller, J. D. (2015). Pablo Escobar: El auge y la caída del rey de la cocaína . Createspace.

- Tikkaken, A. (s. f.). Pablo Escobar (Colombian criminal). The Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/

- Villatoro, M. (2014). “La verdadera historia de Pablo Escobar, el narcotraficante que asesinó a 10.000 personas”. ABC cultural . https://www.abc.es/

Was this information useful to you?

Updates? Omissions? Article suggestions? Send us your comments and suggestions

Thank you for visiting us :)

Advertisement

Money, Drugs and Madness: The Life and Death of Pablo Escobar

- Share Content on Facebook

- Share Content on LinkedIn

- Share Content on Flipboard

- Share Content on Reddit

- Share Content via Email

Pablo Escobar, the notorious Colombian druglord, once blew up a plane filled with innocent people in a desperate attempt to kill one of his countless enemies. One hundred and seven people died that morning in 1989 when a bomb was detonated on Avianca Flight 203. Three more were killed by falling pieces of the aircraft. Escobar's target wasn't even on board.

Among his multitude of crimes, Escobar ordered (and had carried out) the assassination of a Colombian presidential candidate and the country's minister of justice . He placed a bounty on policemen; hundreds were killed. As many as 50,000 people — the death toll may be lower, though most figure the total is at least in the low five figures — were murdered under the reign of "The King of Cocaine ."

For all the gauzy remembrances that some lamely cling to — Escobar as the dedicated family man, the poor son of Colombia made good, a Latin American Robin Hood — the two men who finally brought Escobar to justice want you to remember: He was none of those.

"There's nothing to glamorize about this guy," says Steve Murphy, a former Drug Enforcement Agency agent whose work is dramatized in " Narcos ," the Netflix series that debuted in 2015. "He's nothing more than a mass murderer. People look up to him like he's some kind of a hero. Let me tell you, if he told you to do something, and he's your idol, and you didn't do it, he'd kill you. He didn't care that you liked him. It was all about him."

Who Was Pablo Escobar?

Was he really that bad, how did he come to his end, escobar's legacy lives on.

Pablo Emilio Escobar Gaviria was born in Rionegro, Colombia, in 1949. As a youngster, he and his family moved to a suburb of Medellin, and by the time he was in his teens, he was deep into the criminal world, stealing cars and reselling gravestones he pilfered from local cemeteries.

It wasn't until Escobar hit his 20s that he was introduced to big-time crime; taking coca, grown mostly in Peru and Bolivia, synthesising it into cocaine, and shipping it to sell in the United States. By his late 20s, Escobar had founded and assumed sole control of the Medellin cartel, maybe the most successful criminal operation ever. At its height, the cartel pulled in an estimated $420 million — million — a week , 80 percent of the cocaine business worldwide.

The Medellin cartel made so much money that it literally had to stuff cash in bags — billions of U.S. dollars — and bury it. Escobar became a millionaire in his 20s. His fortune soon soared into the billions. He hit the Forbes list of richest people in the world seven years running, from 1987 (when he was estimated to be worth $3 billion) through 1993.

Escobar spent his money on a personal zoo (complete with hippos that still run wild ) at a lavish estate in northwest Colombia, Hacienda Nápoles. He splurged on cars, on boats, on a fleet of airplanes, on at least one professional soccer team, and on dozens of houses throughout the country. Keenly aware of his public persona, he gave millions away, too, building housing and soccer fields in poor areas of Medellin.

But Escobar grew and maintained that wealth through the 1980s and early '90s, it should be remembered, by being a ruthless, cold-blooded killer.

In silencing politicians, police, journalists and anyone who threatened his empire, Escobar turned to a virtual army of sicarios . These poor, often hand-picked Colombians — mostly teenage boys — were paid to protect Escobar and carry out his wishes. Those wishes often included killing. (A sicario is a hitman or hired assassin.)

"Pablo just manipulated those people is all he did. He gave them things, which was good, but when he needed new sicarios , he went right back in [to the poor sections of town]," Murphy says. "They were willing to die for him. Fight and die for him. We hate to give him credit for anything, but he did have somewhat of a charismatic personality."

Murphy and his partner, Javier Peña, who also is portrayed in the Netflix series, often tangled with the people who would do Escobar's bidding.

"One of them, when I interviewed him," Peña says, "he was 15 years old, and he said, 'I love Pablo Escobar, I will die for him and I will kill for him. He gave me money, my mom now has shelter, has food, has a little house.' He said, 'I'll be dead by the time I'm 23 years old, but I will die and kill for Pablo Escobar. He has given me a life.'"

One of Escobar's main hitmen was Jhon Jairo Velásquez, known as "Popeye." He claims to have personally killed 300 people and ordered (on Escobar's behalf) the murders of 3,000 others.

In the early 1990s, Medellin was known as the most violent city in the world , with 380 homicides per 100,000 people every year.