The history of women’s work and wages and how it has created success for us all

As we celebrate the centennial of the 19th Amendment, giving women the right to vote, we should also celebrate the major strides women have made in the labor market. Their entry into paid work has been a major factor in America’s prosperity over the past century and a quarter.

Despite this progress, evidence suggests that many women remain unable to achieve their goals. The gap in earnings between women and men, although smaller than it was years ago, is still significant; women continue to be underrepresented in certain industries and occupations; and too many women struggle to combine aspirations for work and family. Further advancement has been hampered by barriers to equal opportunity and workplace rules and norms that fail to support a reasonable work-life balance. If these obstacles persist, we will squander the potential of many of our citizens and incur a substantial loss to the productive capacity of our economy at a time when the aging of the population and weak productivity growth are already weighing on economic growth.

A historical perspective on women in the labor force

In the early 20th century, most women in the United States did not work outside the home, and those who did were primarily young and unmarried. In that era, just 20 percent of all women were “gainful workers,” as the Census Bureau then categorized labor force participation outside the home, and only 5 percent of those married were categorized as such. Of course, these statistics somewhat understate the contributions of married women to the economy beyond housekeeping and childrearing, since women’s work in the home often included work in family businesses and the home production of goods, such as agricultural products, for sale. Also, the aggregate statistics obscure the differential experience of women by race. African American women were about twice as likely to participate in the labor force as were white women at the time, largely because they were more likely to remain in the labor force after marriage.

If these obstacles persist, we will squander the potential of many of our citizens and incur a substantial loss to the productive capacity of our economy at a time when the aging of the population and weak productivity growth are already weighing on economic growth.

The fact that many women left work upon marriage reflected cultural norms, the nature of the work available to them, and legal strictures. The occupational choices of those young women who did work were severely circumscribed. Most women lacked significant education—and women with little education mostly toiled as piece workers in factories or as domestic workers, jobs that were dirty and often unsafe. Educated women were scarce. Fewer than 2 percent of all 18- to 24-year-olds were enrolled in an institution of higher education, and just one-third of those were women. Such women did not have to perform manual labor, but their choices were likewise constrained.

Despite the widespread sentiment against women, particularly married women, working outside the home and with the limited opportunities available to them, women did enter the labor force in greater numbers over this period, with participation rates reaching nearly 50 percent for single women by 1930 and nearly 12 percent for married women. This rise suggests that while the incentive—and in many cases the imperative—remained for women to drop out of the labor market at marriage when they could rely on their husband’s income, mores were changing. Indeed, these years overlapped with the so-called first wave of the women’s movement, when women came together to agitate for change on a variety of social issues, including suffrage and temperance, and which culminated in the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920 guaranteeing women the right to vote.

Between the 1930s and mid-1970s, women’s participation in the economy continued to rise, with the gains primarily owing to an increase in work among married women. By 1970, 50 percent of single women and 40 percent of married women were participating in the labor force. Several factors contributed to this rise. First, with the advent of mass high school education, graduation rates rose substantially. At the same time, new technologies contributed to an increased demand for clerical workers, and these jobs were increasingly taken on by women. Moreover, because these jobs tended to be cleaner and safer, the stigma attached to work for a married woman diminished. And while there were still marriage bars that forced women out of the labor force, these formal barriers were gradually removed over the period following World War II.

Over the decades from 1930 to 1970, increasing opportunities also arose for highly educated women. That said, early in that period, most women still expected to have short careers, and women were still largely viewed as secondary earners whose husbands’ careers came first.

As time progressed, attitudes about women working and their employment prospects changed. As women gained experience in the labor force, they increasingly saw that they could balance work and family. A new model of the two-income family emerged. Some women began to attend college and graduate school with the expectation of working, whether or not they planned to marry and have families.

By the 1970s, a dramatic change in women’s work lives was under way. In the period after World War II, many women had not expected that they would spend as much of their adult lives working as turned out to be the case. By contrast, in the 1970s young women more commonly expected that they would spend a substantial portion of their lives in the labor force, and they prepared for it, increasing their educational attainment and taking courses and college majors that better equipped them for careers as opposed to just jobs.

These changes in attitudes and expectations were supported by other changes under way in society. Workplace protections were enhanced through the passage of the Pregnancy Discrimination Act in 1978 and the recognition of sexual harassment in the workplace. Access to birth control increased, which allowed married couples greater control over the size of their families and young women the ability to delay marriage and to plan children around their educational and work choices. And in 1974, women gained, for the first time, the right to apply for credit in their own name without a male co-signer.

By the early 1990s, the labor force participation rate of prime working-age women—those between the ages of 25 and 54—reached just over 74 percent, compared with roughly 93 percent for prime working-age men. By then, the share of women going into the traditional fields of teaching, nursing, social work, and clerical work declined, and more women were becoming doctors, lawyers, managers, and professors. As women increased their education and joined industries and occupations formerly dominated by men, the gap in earnings between women and men began to close significantly.

Remaining challenges and some possible solutions

We, as a country, have reaped great benefits from the increasing role that women have played in the economy. But evidence suggests that barriers to women’s continued progress remain. The participation rate for prime working-age women peaked in the late 1990s and currently stands at about 76 percent. Of course, women, particularly those with lower levels of education, have been affected by the same economic forces that have been pushing down participation among men, including technical change and globalization. However, women’s participation plateaued at a level well below that of prime working-age men, which stands at about 89 percent. While some married women choose not to work, the size of this disparity should lead us to examine the extent to which structural problems, such as a lack of equal opportunity and challenges to combining work and family, are holding back women’s advancement.

Recent research has shown that although women now enter professional schools in numbers nearly equal to men, they are still substantially less likely to reach the highest echelons of their professions.

The gap in earnings between men and women has narrowed substantially, but progress has slowed lately, and women working full time still earn about 17 percent less than men, on average, each week. Even when we compare men and women in the same or similar occupations who appear nearly identical in background and experience, a gap of about 10 percent typically remains. As such, we cannot rule out that gender-related impediments hold back women, including outright discrimination, attitudes that reduce women’s success in the workplace, and an absence of mentors.

Recent research has shown that although women now enter professional schools in numbers nearly equal to men, they are still substantially less likely to reach the highest echelons of their professions. Even in my own field of economics, women constitute only about one-third of Ph.D. recipients, a number that has barely budged in two decades. This lack of success in climbing the professional ladder would seem to explain why the wage gap actually remains largest for those at the top of the earnings distribution.

One of the primary factors contributing to the failure of these highly skilled women to reach the tops of their professions and earn equal pay is that top jobs in fields such as law and business require longer workweeks and penalize taking time off. This would have a disproportionately large effect on women who continue to bear the lion’s share of domestic and child-rearing responsibilities.

But it can be difficult for women to meet the demands in these fields once they have children. The very fact that these types of jobs require such long hours likely discourages some women—as well as men—from pursuing these career tracks. Advances in technology have facilitated greater work-sharing and flexibility in scheduling, and there are further opportunities in this direction. Economic models also suggest that while it can be difficult for any one employer to move to a model with shorter hours, if many firms were to change their model, they and their workers could all be better off.

Of course, most women are not employed in fields that require such long hours or that impose such severe penalties for taking time off. But the difficulty of balancing work and family is a widespread problem. In fact, the recent trend in many occupations is to demand complete scheduling flexibility, which can result in too few hours of work for those with family demands and can make it difficult to schedule childcare. Reforms that encourage companies to provide some predictability in schedules, cross-train workers to perform different tasks, or require a minimum guaranteed number of hours in exchange for flexibility could improve the lives of workers holding such jobs. Another problem is that in most states, childcare is affordable for fewer than half of all families. And just 5 percent of workers with wages in the bottom quarter of the wage distribution have jobs that provide them with paid family leave. This circumstance puts many women in the position of having to choose between caring for a sick family member and keeping their jobs.

This possibility should inform our own thinking about policies to make it easier for women and men to combine their family and career aspirations. For instance, improving access to affordable and good quality childcare would appear to fit the bill, as it has been shown to support full-time employment. Recently, there also seems to be some momentum for providing families with paid leave at the time of childbirth. The experience in Europe suggests picking policies that do not narrowly target childbirth, but instead can be used to meet a variety of health and caregiving responsibilities.

The United States faces a number of longer-term economic challenges, including the aging of the population and the low growth rate of productivity. One recent study estimates that increasing the female participation rate to that of men would raise our gross domestic product by 5 percent. Our workplaces and families, as well as women themselves, would benefit from continued progress. However, a number of factors appear to be holding women back, including the difficulty women currently have in trying to combine their careers with other aspects of their lives, including caregiving. In looking to solutions, we should consider improvements to work environments and policies that benefit not only women, but all workers. Pursuing such a strategy would be in keeping with the story of the rise in women’s involvement in the workforce, which has contributed not only to their own well-being but more broadly to the welfare and prosperity of our country.

This essay is a revised version of a speech that Janet Yellen, then chair of the Federal Reserve, delivered on May 5, 2017 at the “125 Years of Women at Brown Conference,” sponsored by Brown University in Providence, Rhode Island. Yellen would like to thank Stephanie Aaronson, now vice president and director of Economic Studies at the Brookings Institution, for her assistance in the preparation of the original remarks. Read the full text of the speech here »

About the Author

Janet l. yellen, distinguished fellow in residence – economic studies, the hutchins center on fiscal and monetary policy, more from janet yellen.

Former Fed chair Janet Yellen on gender and racial diversity of the federal government’s economists

Janet Yellen delivered this remark at the public event, “The gender and racial diversity of the federal government’s economists” by Hutchins Center on Fiscal & Monetary Policy at Brookings on September 23, 2019.

The gender and racial diversity of the federal government’s economists

The lack of diversity in the field of economics – in addition to the lack of progress relative to other STEM fields – is drawing increasing attention in the profession, but nearly all the focus has been on economists at academic institutions, and little attention has been devoted to the diversity of the economists employed […]

MORE FROM THE 19A SERIES

Leaving all to younger hands: Why the history of the women’s suffragist movement matters

Dr. Susan Ware places the passage of the 19th Amendment in its appropriate historical context, highlights its shortfalls, and explains why celebrating the Amendment’s complex history matters.

Women warriors: The ongoing story of integrating and diversifying the American armed forces

General (ret.) Lori J. Robinson and Michael O’Hanlon discuss the strides made toward greater participation of women in the U.S. military, and the work still to be done to ensure equitable experiences for all service members.

Women’s work boosts middle class incomes but creates a family time squeeze that needs to be eased

Middle-class incomes have risen modestly in recent decades, and most of any gains in their incomes are the result of more working women. Isabel Sawhill and Katherine Guyot explain the important role women play in middle class households and the challenges they face, including family “time squeeze.”

- Media Relations

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

Report | Wages, Incomes, and Wealth

“Women’s work” and the gender pay gap : How discrimination, societal norms, and other forces affect women’s occupational choices—and their pay

Report • By Jessica Schieder and Elise Gould • July 20, 2016

Download PDF

Press release

Share this page:

What this report finds: Women are paid 79 cents for every dollar paid to men—despite the fact that over the last several decades millions more women have joined the workforce and made huge gains in their educational attainment. Too often it is assumed that this pay gap is not evidence of discrimination, but is instead a statistical artifact of failing to adjust for factors that could drive earnings differences between men and women. However, these factors—particularly occupational differences between women and men—are themselves often affected by gender bias. For example, by the time a woman earns her first dollar, her occupational choice is the culmination of years of education, guidance by mentors, expectations set by those who raised her, hiring practices of firms, and widespread norms and expectations about work–family balance held by employers, co-workers, and society. In other words, even though women disproportionately enter lower-paid, female-dominated occupations, this decision is shaped by discrimination, societal norms, and other forces beyond women’s control.

Why it matters, and how to fix it: The gender wage gap is real—and hurts women across the board by suppressing their earnings and making it harder to balance work and family. Serious attempts to understand the gender wage gap should not include shifting the blame to women for not earning more. Rather, these attempts should examine where our economy provides unequal opportunities for women at every point of their education, training, and career choices.

Introduction and key findings

Women are paid 79 cents for every dollar paid to men (Hegewisch and DuMonthier 2016). This is despite the fact that over the last several decades millions more women have joined the workforce and made huge gains in their educational attainment.

Critics of this widely cited statistic claim it is not solid evidence of economic discrimination against women because it is unadjusted for characteristics other than gender that can affect earnings, such as years of education, work experience, and location. Many of these skeptics contend that the gender wage gap is driven not by discrimination, but instead by voluntary choices made by men and women—particularly the choice of occupation in which they work. And occupational differences certainly do matter—occupation and industry account for about half of the overall gender wage gap (Blau and Kahn 2016).

To isolate the impact of overt gender discrimination—such as a woman being paid less than her male coworker for doing the exact same job—it is typical to adjust for such characteristics. But these adjusted statistics can radically understate the potential for gender discrimination to suppress women’s earnings. This is because gender discrimination does not occur only in employers’ pay-setting practices. It can happen at every stage leading to women’s labor market outcomes.

Take one key example: occupation of employment. While controlling for occupation does indeed reduce the measured gender wage gap, the sorting of genders into different occupations can itself be driven (at least in part) by discrimination. By the time a woman earns her first dollar, her occupational choice is the culmination of years of education, guidance by mentors, expectations set by those who raised her, hiring practices of firms, and widespread norms and expectations about work–family balance held by employers, co-workers, and society. In other words, even though women disproportionately enter lower-paid, female-dominated occupations, this decision is shaped by discrimination, societal norms, and other forces beyond women’s control.

This paper explains why gender occupational sorting is itself part of the discrimination women face, examines how this sorting is shaped by societal and economic forces, and explains that gender pay gaps are present even within occupations.

Key points include:

- Gender pay gaps within occupations persist, even after accounting for years of experience, hours worked, and education.

- Decisions women make about their occupation and career do not happen in a vacuum—they are also shaped by society.

- The long hours required by the highest-paid occupations can make it difficult for women to succeed, since women tend to shoulder the majority of family caretaking duties.

- Many professions dominated by women are low paid, and professions that have become female-dominated have become lower paid.

This report examines wages on an hourly basis. Technically, this is an adjusted gender wage gap measure. As opposed to weekly or annual earnings, hourly earnings ignore the fact that men work more hours on average throughout a week or year. Thus, the hourly gender wage gap is a bit smaller than the 79 percent figure cited earlier. This minor adjustment allows for a comparison of women’s and men’s wages without assuming that women, who still shoulder a disproportionate amount of responsibilities at home, would be able or willing to work as many hours as their male counterparts. Examining the hourly gender wage gap allows for a more thorough conversation about how many factors create the wage gap women experience when they cash their paychecks.

Within-occupation gender wage gaps are large—and persist after controlling for education and other factors

Those keen on downplaying the gender wage gap often claim women voluntarily choose lower pay by disproportionately going into stereotypically female professions or by seeking out lower-paid positions. But even when men and women work in the same occupation—whether as hairdressers, cosmetologists, nurses, teachers, computer engineers, mechanical engineers, or construction workers—men make more, on average, than women (CPS microdata 2011–2015).

As a thought experiment, imagine if women’s occupational distribution mirrored men’s. For example, if 2 percent of men are carpenters, suppose 2 percent of women become carpenters. What would this do to the wage gap? After controlling for differences in education and preferences for full-time work, Goldin (2014) finds that 32 percent of the gender pay gap would be closed.

However, leaving women in their current occupations and just closing the gaps between women and their male counterparts within occupations (e.g., if male and female civil engineers made the same per hour) would close 68 percent of the gap. This means examining why waiters and waitresses, for example, with the same education and work experience do not make the same amount per hour. To quote Goldin:

Another way to measure the effect of occupation is to ask what would happen to the aggregate gender gap if one equalized earnings by gender within each occupation or, instead, evened their proportions for each occupation. The answer is that equalizing earnings within each occupation matters far more than equalizing the proportions by each occupation. (Goldin 2014)

This phenomenon is not limited to low-skilled occupations, and women cannot educate themselves out of the gender wage gap (at least in terms of broad formal credentials). Indeed, women’s educational attainment outpaces men’s; 37.0 percent of women have a college or advanced degree, as compared with 32.5 percent of men (CPS ORG 2015). Furthermore, women earn less per hour at every education level, on average. As shown in Figure A , men with a college degree make more per hour than women with an advanced degree. Likewise, men with a high school degree make more per hour than women who attended college but did not graduate. Even straight out of college, women make $4 less per hour than men—a gap that has grown since 2000 (Kroeger, Cooke, and Gould 2016).

Women earn less than men at every education level : Average hourly wages, by gender and education, 2015

| Education level | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| Less than high school | $13.93 | $10.89 |

| High school | $18.61 | $14.57 |

| Some college | $20.95 | $16.59 |

| College | $35.23 | $26.51 |

| Advanced degree | $45.84 | $33.65 |

The data below can be saved or copied directly into Excel.

The data underlying the figure.

Source : EPI analysis of Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata

Copy the code below to embed this chart on your website.

Steering women to certain educational and professional career paths—as well as outright discrimination—can lead to different occupational outcomes

The gender pay gap is driven at least in part by the cumulative impact of many instances over the course of women’s lives when they are treated differently than their male peers. Girls can be steered toward gender-normative careers from a very early age. At a time when parental influence is key, parents are often more likely to expect their sons, rather than their daughters, to work in science, technology, engineering, or mathematics (STEM) fields, even when their daughters perform at the same level in mathematics (OECD 2015).

Expectations can become a self-fulfilling prophecy. A 2005 study found third-grade girls rated their math competency scores much lower than boys’, even when these girls’ performance did not lag behind that of their male counterparts (Herbert and Stipek 2005). Similarly, in states where people were more likely to say that “women [are] better suited for home” and “math is for boys,” girls were more likely to have lower math scores and higher reading scores (Pope and Sydnor 2010). While this only establishes a correlation, there is no reason to believe gender aptitude in reading and math would otherwise be related to geography. Parental expectations can impact performance by influencing their children’s self-confidence because self-confidence is associated with higher test scores (OECD 2015).

By the time young women graduate from high school and enter college, they already evaluate their career opportunities differently than young men do. Figure B shows college freshmen’s intended majors by gender. While women have increasingly gone into medical school and continue to dominate the nursing field, women are significantly less likely to arrive at college interested in engineering, computer science, or physics, as compared with their male counterparts.

Women arrive at college less interested in STEM fields as compared with their male counterparts : Intent of first-year college students to major in select STEM fields, by gender, 2014

| Intended major | Percentage of men | Percentage of women |

|---|---|---|

| Biological and life sciences | 11% | 16% |

| Engineering | 19% | 6% |

| Chemistry | 1% | 1% |

| Computer science | 6% | 1% |

| Mathematics/ statistics | 1% | 1% |

| Physics | 1% | 0.3% |

Source: EPI adaptation of Corbett and Hill (2015) analysis of Eagan et al. (2014)

These decisions to allow doors to lucrative job opportunities to close do not take place in a vacuum. Many factors might make it difficult for a young woman to see herself working in computer science or a similarly remunerative field. A particularly depressing example is the well-publicized evidence of sexism in the tech industry (Hewlett et al. 2008). Unfortunately, tech isn’t the only STEM field with this problem.

Young women may be discouraged from certain career paths because of industry culture. Even for women who go against the grain and pursue STEM careers, if employers in the industry foster an environment hostile to women’s participation, the share of women in these occupations will be limited. One 2008 study found that “52 percent of highly qualified females working for SET [science, technology, and engineering] companies quit their jobs, driven out by hostile work environments and extreme job pressures” (Hewlett et al. 2008). Extreme job pressures are defined as working more than 100 hours per week, needing to be available 24/7, working with or managing colleagues in multiple time zones, and feeling pressure to put in extensive face time (Hewlett et al. 2008). As compared with men, more than twice as many women engage in housework on a daily basis, and women spend twice as much time caring for other household members (BLS 2015). Because of these cultural norms, women are less likely to be able to handle these extreme work pressures. In addition, 63 percent of women in SET workplaces experience sexual harassment (Hewlett et al. 2008). To make matters worse, 51 percent abandon their SET training when they quit their job. All of these factors play a role in steering women away from highly paid occupations, particularly in STEM fields.

The long hours required for some of the highest-paid occupations are incompatible with historically gendered family responsibilities

Those seeking to downplay the gender wage gap often suggest that women who work hard enough and reach the apex of their field will see the full fruits of their labor. In reality, however, the gender wage gap is wider for those with higher earnings. Women in the top 95th percentile of the wage distribution experience a much larger gender pay gap than lower-paid women.

Again, this large gender pay gap between the highest earners is partially driven by gender bias. Harvard economist Claudia Goldin (2014) posits that high-wage firms have adopted pay-setting practices that disproportionately reward individuals who work very long and very particular hours. This means that even if men and women are equally productive per hour, individuals—disproportionately men—who are more likely to work excessive hours and be available at particular off-hours are paid more highly (Hersch and Stratton 2002; Goldin 2014; Landers, Rebitzer, and Taylor 1996).

It is clear why this disadvantages women. Social norms and expectations exert pressure on women to bear a disproportionate share of domestic work—particularly caring for children and elderly parents. This can make it particularly difficult for them (relative to their male peers) to be available at the drop of a hat on a Sunday evening after working a 60-hour week. To the extent that availability to work long and particular hours makes the difference between getting a promotion or seeing one’s career stagnate, women are disadvantaged.

And this disadvantage is reinforced in a vicious circle. Imagine a household where both members of a male–female couple have similarly demanding jobs. One partner’s career is likely to be prioritized if a grandparent is hospitalized or a child’s babysitter is sick. If the past history of employer pay-setting practices that disadvantage women has led to an already-existing gender wage gap for this couple, it can be seen as “rational” for this couple to prioritize the male’s career. This perpetuates the expectation that it always makes sense for women to shoulder the majority of domestic work, and further exacerbates the gender wage gap.

Female-dominated professions pay less, but it’s a chicken-and-egg phenomenon

Many women do go into low-paying female-dominated industries. Home health aides, for example, are much more likely to be women. But research suggests that women are making a logical choice, given existing constraints . This is because they will likely not see a significant pay boost if they try to buck convention and enter male-dominated occupations. Exceptions certainly exist, particularly in the civil service or in unionized workplaces (Anderson, Hegewisch, and Hayes 2015). However, if women in female-dominated occupations were to go into male-dominated occupations, they would often have similar or lower expected wages as compared with their female counterparts in female-dominated occupations (Pitts 2002). Thus, many women going into female-dominated occupations are actually situating themselves to earn higher wages. These choices thereby maximize their wages (Pitts 2002). This holds true for all categories of women except for the most educated, who are more likely to earn more in a male profession than a female profession. There is also evidence that if it becomes more lucrative for women to move into male-dominated professions, women will do exactly this (Pitts 2002). In short, occupational choice is heavily influenced by existing constraints based on gender and pay-setting across occupations.

To make matters worse, when women increasingly enter a field, the average pay in that field tends to decline, relative to other fields. Levanon, England, and Allison (2009) found that when more women entered an industry, the relative pay of that industry 10 years later was lower. Specifically, they found evidence of devaluation—meaning the proportion of women in an occupation impacts the pay for that industry because work done by women is devalued.

Computer programming is an example of a field that has shifted from being a very mixed profession, often associated with secretarial work in the past, to being a lucrative, male-dominated profession (Miller 2016; Oldenziel 1999). While computer programming has evolved into a more technically demanding occupation in recent decades, there is no skills-based reason why the field needed to become such a male-dominated profession. When men flooded the field, pay went up. In contrast, when women became park rangers, pay in that field went down (Miller 2016).

Further compounding this problem is that many professions where pay is set too low by market forces, but which clearly provide enormous social benefits when done well, are female-dominated. Key examples range from home health workers who care for seniors, to teachers and child care workers who educate today’s children. If closing gender pay differences can help boost pay and professionalism in these key sectors, it would be a huge win for the economy and society.

The gender wage gap is real—and hurts women across the board. Too often it is assumed that this gap is not evidence of discrimination, but is instead a statistical artifact of failing to adjust for factors that could drive earnings differences between men and women. However, these factors—particularly occupational differences between women and men—are themselves affected by gender bias. Serious attempts to understand the gender wage gap should not include shifting the blame to women for not earning more. Rather, these attempts should examine where our economy provides unequal opportunities for women at every point of their education, training, and career choices.

— This paper was made possible by a grant from the Peter G. Peterson Foundation. The statements made and views expressed are solely the responsibility of the authors.

— The authors wish to thank Josh Bivens, Barbara Gault, and Heidi Hartman for their helpful comments.

About the authors

Jessica Schieder joined EPI in 2015. As a research assistant, she supports the research of EPI’s economists on topics such as the labor market, wage trends, executive compensation, and inequality. Prior to joining EPI, Jessica worked at the Center for Effective Government (formerly OMB Watch) as a revenue and spending policies analyst, where she examined how budget and tax policy decisions impact working families. She holds a bachelor’s degree in international political economy from Georgetown University.

Elise Gould , senior economist, joined EPI in 2003. Her research areas include wages, poverty, economic mobility, and health care. She is a co-author of The State of Working America, 12th Edition . In the past, she has authored a chapter on health in The State of Working America 2008/09; co-authored a book on health insurance coverage in retirement; published in venues such as The Chronicle of Higher Education , Challenge Magazine , and Tax Notes; and written for academic journals including Health Economics , Health Affairs, Journal of Aging and Social Policy, Risk Management & Insurance Review, Environmental Health Perspectives , and International Journal of Health Services . She holds a master’s in public affairs from the University of Texas at Austin and a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Wisconsin at Madison.

Anderson, Julie, Ariane Hegewisch, and Jeff Hayes 2015. The Union Advantage for Women . Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Blau, Francine D., and Lawrence M. Kahn 2016. The Gender Wage Gap: Extent, Trends, and Explanations . National Bureau of Economic Research, Working Paper No. 21913.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 2015. American Time Use Survey public data series. U.S. Census Bureau.

Corbett, Christianne, and Catherine Hill. 2015. Solving the Equation: The Variables for Women’s Success in Engineering and Computing . American Association of University Women (AAUW).

Current Population Survey Outgoing Rotation Group microdata (CPS ORG). 2011–2015. Survey conducted by the Bureau of the Census for the Bureau of Labor Statistics [ machine-readable microdata file ]. U.S. Census Bureau.

Goldin, Claudia. 2014. “ A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter .” American Economic Review, vol. 104, no. 4, 1091–1119.

Hegewisch, Ariane, and Asha DuMonthier. 2016. The Gender Wage Gap: 2015; Earnings Differences by Race and Ethnicity . Institute for Women’s Policy Research.

Herbert, Jennifer, and Deborah Stipek. 2005. “The Emergence of Gender Difference in Children’s Perceptions of Their Academic Competence.” Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology , vol. 26, no. 3, 276–295.

Hersch, Joni, and Leslie S. Stratton. 2002. “ Housework and Wages .” The Journal of Human Resources , vol. 37, no. 1, 217–229.

Hewlett, Sylvia Ann, Carolyn Buck Luce, Lisa J. Servon, Laura Sherbin, Peggy Shiller, Eytan Sosnovich, and Karen Sumberg. 2008. The Athena Factor: Reversing the Brain Drain in Science, Engineering, and Technology . Harvard Business Review.

Kroeger, Teresa, Tanyell Cooke, and Elise Gould. 2016. The Class of 2016: The Labor Market Is Still Far from Ideal for Young Graduates . Economic Policy Institute.

Landers, Renee M., James B. Rebitzer, and Lowell J. Taylor. 1996. “ Rat Race Redux: Adverse Selection in the Determination of Work Hours in Law Firms .” American Economic Review , vol. 86, no. 3, 329–348.

Levanon, Asaf, Paula England, and Paul Allison. 2009. “Occupational Feminization and Pay: Assessing Causal Dynamics Using 1950-2000 U.S. Census Data.” Social Forces, vol. 88, no. 2, 865–892.

Miller, Claire Cain. 2016. “As Women Take Over a Male-Dominated Field, the Pay Drops.” New York Times , March 18.

Oldenziel, Ruth. 1999. Making Technology Masculine: Men, Women, and Modern Machines in America, 1870-1945 . Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2015. The ABC of Gender Equality in Education: Aptitude, Behavior, Confidence .

Pitts, Melissa M. 2002. Why Choose Women’s Work If It Pays Less? A Structural Model of Occupational Choice. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Working Paper 2002-30.

Pope, Devin G., and Justin R. Sydnor. 2010. “ Geographic Variation in the Gender Differences in Test Scores .” Journal of Economic Perspectives , vol. 24, no. 2, 95–108.

See related work on Wages, Incomes, and Wealth | Women

See more work by Jessica Schieder and Elise Gould

Women in the Workplace 2023

Women in the Workplace

This is the ninth year of the Women in the Workplace report. Conducted in partnership with LeanIn.Org , this effort is the largest study of women in corporate America and Canada. This year, we collected information from 276 participating organizations employing more than ten million people. At these organizations, we surveyed more than 27,000 employees and 270 senior HR leaders, who shared insights on their policies and practices. The report provides an intersectional look at the specific biases and barriers faced by Asian, Black, Latina, and LGBTQ+ women and women with disabilities.

About the authors

This year’s research reveals some hard-fought gains at the top, with women’s representation in the C-suite at the highest it has ever been. However, with lagging progress in the middle of the pipeline—and a persistent underrepresentation of women of color 1 Women of color include women who are Asian, Black, Latina, Middle Eastern, mixed race, Native American/American Indian/Indigenous/Alaskan Native, and Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. Due to small sample sizes for other racial and ethnic groups, reported findings on individual racial and ethnic groups are restricted to Asian women, Black women, and Latinas. —true parity remains painfully out of reach.

The survey debunks four myths about women’s workplace experiences and career advancement. A few of these myths cover old ground, but given the notable lack of progress, they warrant repeating. These include women’s career ambitions, the greatest barrier to their ascent to senior leadership, the effect and extent of microaggressions in the workplace, and women’s appetite for flexible work. We hope highlighting these myths will help companies find a path forward that casts aside outdated thinking once and for all and accelerates progress for women.

The rest of this article summarizes the main findings from the Women in the Workplace 2023 report and provides clear solutions that organizations can implement to make meaningful progress toward gender equality.

State of the pipeline

Over the past nine years, women—and especially women of color—have remained underrepresented across the corporate pipeline (Exhibit 1). However, we see a growing bright spot in senior leadership. Since 2015, the number of women in the C-suite has increased from 17 to 28 percent, and the representation of women at the vice president and senior vice president levels has also improved significantly.

These hard-earned gains are encouraging yet fragile: slow progress for women at the manager and director levels—representation has grown only three and four percentage points, respectively—creates a weak middle in the pipeline for employees who represent the vast majority of women in corporate America. And the “Great Breakup” trend we discovered in last year’s survey continues for women at the director level, the group next in line for senior-leadership positions. That is, director-level women are leaving at a higher rate than in past years—and at a notably higher rate than men at the same level. As a result of these two dynamics, there are fewer women in line for top positions.

To view previous reports, please visit the Women in the Workplace archive

Moreover, progress for women of color is lagging behind their peers’ progress. At nearly every step in the pipeline, the representation of women of color falls relative to White women and men of the same race and ethnicity. Until companies address this inequity head-on, women of color will remain severely underrepresented in leadership positions—and mostly absent from the C-suite.

“It’s disheartening to be part of an organization for as many years as I have been and still not see a person like me in senior leadership. Until I see somebody like me in the C-suite, I’m never going to really feel like I belong.”

—Latina, manager, former executive director

Four myths about the state of women at work

This year’s survey reveals the truth about four common myths related to women in the workplace.

Myth: Women are becoming less ambitious Reality: Women are more ambitious than before the pandemic—and flexibility is fueling that ambition

At every stage of the pipeline, women are as committed to their careers and as interested in being promoted as men. Women and men at the director level—when the C-suite is in closer view—are also equally interested in senior-leadership roles. And young women are especially ambitious. Nine in ten women under the age of 30 want to be promoted to the next level, and three in four aspire to become senior leaders.

Women represent roughly one in four C-suite leaders, and women of color just one in 16.

Moreover, the pandemic and increased flexibility did not dampen women’s ambitions. Roughly 80 percent of women want to be promoted to the next level, compared with 70 percent in 2019. And the same holds true for men. Women of color are even more ambitious than White women: 88 percent want to be promoted to the next level. Flexibility is allowing women to pursue their ambitions: overall, one in five women say flexibility has helped them stay in their job or avoid reducing their hours. A large number of women who work hybrid or remotely point to feeling less fatigued and burned out as a primary benefit. And a majority of women report having more focused time to get their work done when they work remotely.

The pandemic showed women that a new model of balancing work and life was possible. Now, few want to return to the way things were. Most women are taking more steps to prioritize their personal lives—but at no cost to their ambition. They remain just as committed to their careers and just as interested in advancing as women who aren’t taking more steps. These women are defying the outdated notion that work and life are incompatible, and that one comes at the expense of the other.

Myth: The biggest barrier to women’s advancement is the ‘glass ceiling’ Reality: The ‘broken rung’ is the greatest obstacle women face on the path to senior leadership

For the ninth consecutive year, women face their biggest hurdle at the first critical step up to manager. This year, for every 100 men promoted from entry level to manager, 87 women were promoted (Exhibit 2). And this gap is trending the wrong way for women of color: this year, 73 women of color were promoted to manager for every 100 men, down from 82 women of color last year. As a result of this “broken rung,” women fall behind and can’t catch up.

Progress for early-career Black women remains the furthest behind. After rising in 2020 and 2021 to a high of 96 Black women promoted for every 100 men—likely because of heightened focus across corporate America—Black women’s promotion rates have fallen to 2018 levels, with only 54 Black women promoted for every 100 men this year.

While companies are modestly increasing women’s representation at the top, doing so without addressing the broken rung offers only a temporary stopgap. Because of the gender disparity in early promotions, men end up holding 60 percent of manager-level positions in a typical company, while women occupy 40 percent. Since men significantly outnumber women, there are fewer women to promote to senior managers, and the number of women decreases at every subsequent level.

Myth: Microaggressions have a ‘micro’ impact Reality: Microaggressions have a large and lasting impact on women

Microaggressions are a form of everyday discrimination that is often rooted in bias. They include comments and actions—even subtle ones that are not overtly harmful—that demean or dismiss someone based on their gender, race, or other aspects of their identity. They signal disrespect, cause acute stress, and can negatively impact women’s careers and health.

Years of data show that women experience microaggressions at a significantly higher rate than men: they are twice as likely to be mistaken for someone junior and hear comments on their emotional state (Exhibit 3). For women with traditionally marginalized identities, these slights happen more often and are even more demeaning. As just one example, Asian and Black women are seven times more likely than White women to be confused with someone of the same race and ethnicity.

As a result, the workplace is a mental minefield for many women, particularly those with traditionally marginalized identities. Women who experience microaggressions are much less likely to feel psychologically safe, which makes it harder to take risks, propose new ideas, or raise concerns. The stakes feel just too high. On top of this, 78 percent of women who face microaggressions self-shield at work, or adjust the way they look or act in an effort to protect themselves. For example, many women code-switch—or tone down what they say or do—to try to blend in and avoid a negative reaction at work. Black women are more than twice as likely as women overall to code-switch. And LGBTQ+ women are 2.5 times as likely to feel pressure to change their appearance to be perceived as more professional. The stress caused by these dynamics cuts deep.

Women who experience microaggressions—and self-shield to deflect them—are three times more likely to think about quitting their jobs and four times more likely to almost always be burned out. By leaving microaggressions unchecked, companies miss out on everything women have to offer and risk losing talented employees.

“It’s like I have to act extra happy so I’m not looked at as bitter because I’m a Black woman. And a disabled Black woman at that. If someone says something offensive to me, I have to think about how to respond in a way that does not make me seem like an angry Black woman.”

—Black woman with a physical disability, entry-level role

Myth: It’s mostly women who want—and benefit from—flexible work Reality: Men and women see flexibility as a ‘top 3’ employee benefit and critical to their company’s success

Most employees say that opportunities to work remotely and have control over their schedules are top company benefits, second only to healthcare (Exhibit 4). Workplace flexibility even ranks above tried-and-true benefits such as parental leave and childcare.

As workplace flexibility transforms from a nice-to-have for some employees to a crucial benefit for most, women continue to value it more. This is likely because they still carry out a disproportionate amount of childcare and household work. Indeed, 38 percent of mothers with young children say that without workplace flexibility, they would have had to leave their company or reduce their work hours.

But it’s not just women or mothers who benefit: hybrid and remote work are delivering important benefits to most employees. Most women and men point to better work–life balance as a primary benefit of hybrid and remote work, and a majority cite less fatigue and burnout (Exhibit 5). And research shows that good work–life balance and low burnout are key to organizational success. Moreover, 83 percent of employees cite the ability to work more efficiently and productively as a primary benefit of working remotely. However, it’s worth noting companies see this differently: only half of HR leaders say employee productivity is a primary benefit of working remotely.

For women, hybrid or remote work is about a lot more than flexibility. When women work remotely, they face fewer microaggressions and have higher levels of psychological safety.

Employees who work on-site also see tangible benefits. A majority point to an easier time collaborating and a stronger personal connection to coworkers as the biggest benefits of working on-site—two factors central to employee well-being and effectiveness. However, the culture of on-site work may be falling short. While 77 percent of companies believe a strong organizational culture is a key benefit of on-site work, most employees disagree: only 39 percent of men and 34 percent of women who work on-site say a key benefit is feeling more connected to their organization’s culture.

Not to mention that men benefit disproportionately from on-site work: compared with women who work on-site, men are seven to nine percentage points more likely to be “in the know,” receive the mentorship and sponsorships they need, and have their accomplishments noticed and rewarded.

A majority of organizations have started to formalize their return-to-office policies, motivated by the perceived benefits of on-site work (Exhibit 6). As they do so, they will need to work to ensure everyone can equally reap the benefits of on-site work.

Recommendations for companies

As companies work to support and advance women, they should focus on five core areas:

- tracking outcomes for women’s representation

- empowering managers to be effective people leaders

- addressing microaggressions head-on

- unlocking the full potential of flexible work

- fixing the broken rung, once and for all

Sixty percent of companies have increased their financial and staffing investments in diversity, equity, and inclusion over the past year. And nearly three in four HR leaders say DEI is critical to their companies’ future success.

1. Track outcomes to improve women’s experience and progression

Tracking outcomes is critical to any successful business initiative. Most companies do this consistently when it comes to achieving their financial objectives, but few apply the same rigor to women’s advancement. Here are three steps to get started:

Measure employees’ outcomes and experiences—and use the data to fix trouble spots. Outcomes for drivers of women’s advancement include hiring, promotions, and attrition. Visibility into other metrics—such as participation in career development programs, performance ratings, and employee sentiments—that influence career progression is also important, and data should be collected with appropriate data privacy protections in place. Then, it’s critically important that companies mine their data for insights that will improve women’s experiences and create equal opportunities for advancement. Ultimately, data tracking is only valuable if it leads to organizational change.

Take an intersectional approach to outcome tracking. Tracking metrics by race and gender combined should be table stakes. Yet, even now, fewer than half of companies do this, and far fewer track data by other self-reported identifiers, such as LGBTQ+ identity. Without this level of visibility, the experiences and career progression of women with traditionally marginalized identities can go overlooked.

Share internal goals and metrics with employees. Awareness is a valuable tool for driving change—when employees are able to see opportunities and challenges, they’re more invested in being part of the solution. In addition, transparency with diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) goals and metrics can send a powerful signal to employees with traditionally marginalized identities that they are supported within the organization.

2. Support and reward managers as key drivers of organizational change

Managers are on the front lines of employees’ experiences and central to driving organizational change. As companies more deeply invest in the culture of work, managers play an increasingly critical role in fostering DEI, ensuring employee well-being, and navigating the shift to flexible work. These are all important business priorities, but managers do not always get the direction and support they need to deliver on them. Here are three steps to get started:

Clarify managers’ priorities and reward results. Companies need to explicitly communicate to managers what is core to their roles and motivate them to take action. The most effective way to do this is to include responsibilities like career development, DEI, and employee well-being in managers’ job descriptions and performance reviews. Relatively few companies evaluate managers on metrics linked to people management. For example, although 61 percent of companies point to DEI as a top manager capability, only 28 percent of people managers say their company recognizes DEI in performance reviews. This discrepancy may partially explain why not enough employees say their manager treats DEI as a priority.

Equip managers with the skills they need to be successful. To effectively manage the new demands being placed on them, managers need ongoing education. This includes repeated, relevant, and high-quality training and nudges that emphasize specific examples of core concepts, as well as concrete actions that managers can incorporate into their daily practices. Companies should adopt an “often and varied” approach to training and upskilling and create regular opportunities for coaching so that managers can continue to build the awareness and capabilities they need to be effective.

Make sure managers have the time and support to get it right. It requires significant intentionality and follow-through to be a good people and culture leader, and this is particularly true when it comes to fostering DEI. Companies need to make sure their managers have the time and resources to do these aspects of their job well. Additionally, companies should put policies and systems in place to make managers’ jobs easier.

3. Take steps to put an end to microaggressions

Microaggressions are pervasive, harmful to the employees who experience them, and result in missed ideas and lost talent. Companies need to tackle microaggressions head-on. Here are three steps to get started:

Make clear that microaggressions are not acceptable. To raise employee awareness and set the right tone, it’s crucial that senior leaders communicate that microaggressions and disrespectful behavior of any kind are not welcome. Companies can help with this by developing a code of conduct that articulates what supportive and respectful behavior looks like—as well as what’s unacceptable and uncivil behavior.

Teach employees to avoid and challenge microaggressions. Employees often don’t recognize microaggressions, let alone know what to say or do to be helpful. That’s why it’s so important that companies have employees participate in high-quality bias and allyship training and receive periodic refreshers to keep key learnings top of mind.

Create a culture where it’s normal to surface microaggressions. It’s important for companies to foster a culture that encourages employees to speak up when they see microaggressions or other disrespectful behavior. Although these conversations can be difficult, they often lead to valuable learning and growth. Senior leaders can play an important role in modeling that it is safe to surface and discuss these behaviors.

4. Finetune flexible working models

The past few years have seen a transformation in how we work. Flexibility is now the norm in most companies; the next step is unlocking its full potential and bringing out the best of the benefits that different work arrangements have to offer. Here are three steps to get started:

Establish clear expectations and norms around working flexibly. Without this clarity, employees may have very different and conflicting interpretations of what’s expected of them. It starts with redefining the work best done in person, versus remotely, and injecting flexibility into the work model to meet personal demands. As part of this process, companies need to find the right balance between setting organization-wide guidelines and allowing managers to work with their teams to determine an approach that unlocks benefits for men and women equally.

Measure the impact of new initiatives to support flexibility and adjust them as needed. The last thing companies want to do is fly in the dark as they navigate the transition to flexible work. As organizations roll out new working models and programs to support flexibility, they should carefully track what’s working, and what’s not, and adjust their approach accordingly—a test-and-learn mentality and a spirit of co-creation with employees are critical to getting these changes right.

Few companies currently track outcomes across work arrangements. For example, only 30 percent have tracked the impact of their return-to-office policies on key DEI outcomes.

Put safeguards in place to ensure a level playing field across work arrangements. Companies should take steps to ensure that employees aren’t penalized for working flexibly. This includes putting systems in place to make sure that employees are evaluated fairly, such as redesigning performance reviews to focus on results rather than when and where work gets done. Managers should also be equipped to be part of the solution. This requires educating managers on proximity bias. Managers need to ensure their team members get equal recognition for their contributions and equal opportunities to advance regardless of working model.

5. Fix the broken rung for women, with a focus on women of color

Fixing the broken rung is a tangible, achievable goal and will set off a positive chain reaction across the pipeline. After nine years of very little progress, there is no excuse for companies failing to take action. Here are three steps to get started:

Track inputs and outcomes. To uncover inequities in the promotions process, companies need to track who is put up for and who receives promotions—by race and gender combined. Tracking with this intersectional lens enables employers to identify and address the obstacles faced by women of color, and companies can use these data points to identify otherwise invisible gaps and refine their promotion processes.

Work to de-bias performance reviews and promotions. Leaders should put safeguards in place to ensure that evaluation criteria are applied fairly and bias doesn’t creep into decision making. Companies can take these actions:

- Send “bias” reminders before performance evaluations and promotion cycles, explaining how common biases can impact reviewers’ assessments.

- Appoint a “bias monitor” to keep performance evaluations and promotions discussions focused on the core criteria for the job and surface potentially biased decision making.

- Have reviewers explain the rationale behind their performance evaluations and promotion recommendations. When individuals have to justify their decisions, they are less likely to make snap judgments or rely on gut feelings, which are prone to bias.

Invest in career advancement for women of color. Companies should make sure their career development programs address the distinct biases and barriers that women of color experience. Yet only a fraction of companies tailor career program content for women of color. And given that women of color tend to get less career advice and have less access to senior leaders, formal mentorship and sponsorship programs can be particularly impactful. It’s also important that companies track the outcomes of their career development programs with an intersectional lens to ensure they are having the intended impact and not inadvertently perpetuating inequitable outcomes.

Practices of top-performing companies

Companies with strong women’s representation across the pipeline are more likely to have certain practices in place. The following data are based on an analysis of top performers—companies that have a higher representation of women and women of color than their industry peers (Exhibit 7).

This year’s survey brings to light important realities about women’s experience in the workplace today. Women, and particularly women of color, continue to lose the most ground in middle management, and microaggressions have a significant and enduring effect on many women—especially those with traditionally marginalized identities. Even still, women are as ambitious as ever, and flexibility is contributing to this, allowing all workers to be more productive while also achieving more balance in their lives. These insights can provide a backdrop for senior leaders as they plan for the future of their organizations.

Emily Field is a partner in McKinsey’s Seattle office; Alexis Krivkovich and Lareina Yee are senior partners in the Bay Area office, where Nicole Robinson is an associate partner; Sandra Kügele is a consultant in the Washington, D.C., office.

The authors wish to thank Zoha Bharwani, Quentin Bolton, Sara Callander, Katie Cox, Ping Chin, Robyn Freeman, James Gannon, Jenn Gao, Mar Grech, Alexis Howard, Isabelle Hughes, Sara Kaplan, Ananya Karanam, Sophia Lam, Nina Li, Steven Lee, Anthea Lyu, Tess Mandoli, Abena Mensah, Laura Padula, David Pinski, Jane Qu, Charlie Rixey, Sara Samir, Chanel Shum, Sofia Tam, Neha Verma, Monne Williams, Lily Xu, Yaz Yazar, and Shirley Zhao for their contributions to this article.

Explore a career with us

Related articles.

Women in the workplace: Breaking up to break through

Women in the Workplace 2022

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

‘Women’s Work’ Can No Longer Be Taken for Granted

New Zealand is pursuing a century-old idea to close the gender pay gap: not equal pay for equal work, but equal pay for work of equal value.

By Anna Louie Sussman

Ms. Sussman is a journalist.

Last week, as Americans were obsessing over the results of the presidential election, a New Zealand law aimed at eliminating pay discrimination against women in female-dominated occupations went into effect . The bill, which takes an approach known as “pay equity,” provides a road map for addressing the seemingly intractable gender pay gap .

Unlike “equal pay” — the concept most often used to address gender pay disparities in the United States — the concept of “pay equity” doesn’t just demand equal pay for women doing the same work as men, in the same positions. Such efforts, while worthwhile, ignore the role of occupational segregation in keeping women’s pay down: There are some jobs done mostly by women and others that are still largely the province of men. The latter are typically better paid.

But if the coronavirus has taught us anything, it is that what has traditionally been women’s work — caring, cleaning, the provision of food — can no longer be taken for granted. “It’s not the bankers and the hedge fund managers and the highest paid people” upon whose services we’ve come to rely, said Amy Ross, former national organizer for New Zealand ’s Public Service Association union. “It’s our supermarket workers, it’s our cleaners, it’s our nurses — and they’re all women!”

It has also taught us how poorly these jobs are compensated. Over half of workers designated essential in the United States are women; their jobs are typically paid well below the median hourly wage of a little over $19 an hour. ( Median hourly pay for cashiers is just $11.37; for child care workers it’s $11.65; health support workers such as home health aides and orderlies make $12.68.)

Instead of “equal pay for equal work,” supporters of pay equity call for “equal pay for work of equal value,” or “comparable worth.” They ask us to consider whether a female-dominated occupation such as nursing home aide, for instance, is really so different from a male-dominated one, such as corrections officer, when both are physically exhausting, emotionally demanding, and stressful — and if not, why is the nursing home aide paid so much less? In the words of New Zealand’s law, the pay scale for women should be “determined by reference to what men would be paid to do the same work abstracting from skills, responsibility, conditions and degrees of effort.”

What is at stake is not just a simple pay raise but a societywide reckoning with the value of “women’s work.” How much do we really think this work is worth? But also: How do we decide?

We are having trouble retrieving the article content.

Please enable JavaScript in your browser settings.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access. If you are in Reader mode please exit and log into your Times account, or subscribe for all of The Times.

Thank you for your patience while we verify access.

Already a subscriber? Log in .

Want all of The Times? Subscribe .

- SUGGESTED TOPICS

- The Magazine

- Newsletters

- Managing Yourself

- Managing Teams

- Work-life Balance

- The Big Idea

- Data & Visuals

- Reading Lists

- Case Selections

- HBR Learning

- Topic Feeds

- Account Settings

- Email Preferences

What’s Really Holding Women Back?

- Robin J. Ely

- Irene Padavic

Ask people to explain why women remain so dramatically underrepresented in the senior ranks of most companies, and you will hear from the vast majority a lament that goes something like this: High-level jobs require extremely long hours, women’s devotion to family makes it impossible to put in those hours, and so their careers inevitably suffer.

Not so, say the authors, who spent 18 months working with a global consulting firm that wanted to know why it had so few women in positions of power. Although virtually every employee the authors interviewed related a form of the standard explanation, the firm’s data told a different story. Women weren’t being held back because of trouble balancing work and family; men, too, suffered from that problem and nevertheless advanced. Women were held back because they were encouraged to take accommodations, such as going part-time and shifting to internally facing roles, which derailed their careers.

The real culprit in women’s stalled advancement, the authors conclude, is a general culture of overwork that hurts both sexes and locks gender equality in place. To solve this problem, they argue, we must reconsider what we’re willing to allow the workplace to demand of all employees.

It’s not what most people think.

Idea in Brief

The problem.

To explain why women are still having trouble accessing positions of power and authority in the workplace, many observers point to the challenge of managing the competing demands of work and family. But the data doesn’t support that narrative.

The Research

The authors conducted a long-term study of beliefs and practices at a global consulting firm. The problem, they found, was not the work/family challenge itself but a general culture of overwork in which women were encouraged to take career-derailing accommodations to meet the demands of work and family.

The Way Forward

This culture of overwork punishes not just women but also men, although to a lesser degree. Only by recognizing and addressing the problem as one that affects all employees will we have a chance of achieving workplace equality.

As scholars of gender inequality in the workplace, we are routinely asked by companies to investigate why they are having trouble retaining women and promoting them to senior ranks. It’s a pervasive problem. Women made remarkable progress accessing positions of power and authority in the 1970s and 1980s, but that progress slowed considerably in the 1990s and has stalled completely in this century.

- RE Robin J. Ely is the Diane Doerge Wilson Professor of Business Administration at Harvard Business School and the faculty chair of the HBS Gender Initiative.

- IP Irene Padavic is the Mildred and Claude Pepper Distinguished Professor of Sociology at Florida State University.

Partner Center

A Historical View of Studies of Women’s Work

- Open access

- Published: 19 November 2020

- Volume 30 , pages 251–305, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Ellen Balka 1 &

- Ina Wagner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4416-6259 2

9252 Accesses

8 Citations

2 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

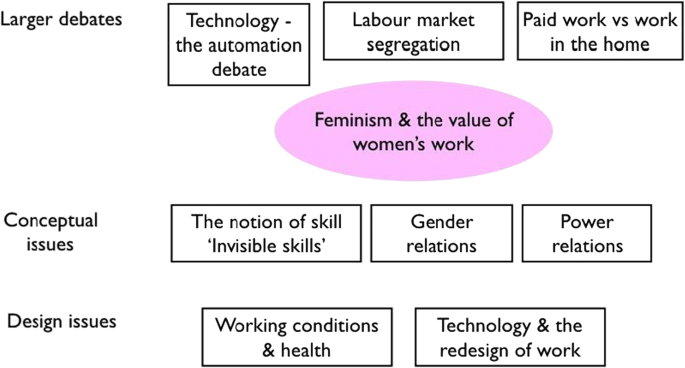

This paper places observational studies of women’s work in historical perspective. We present some of the very early studies (carried out in the period from 1900 to 1930), as well as several examples of fieldwork-based studies of women’s work, undertaken from different perspectives and in varied locations between the 1960s and the mid 1990s. We outline and discuss several areas of thought which have influenced studies of women’s work - the automation debate; the focus on the skills women need in their work; labour market segregation; women’s health; and technology and the redesign of work – and the research methods they used. Our main motivation in this paper is threefold: to demonstrate how fieldwork based studies which have focussed on women’s work have attempted to locate women’s work in a larger context that addresses its visibility and value; to provide a thematic historiography of studies of women’s work, thereby also demonstrating the value of an historical perspective, and a means through which to link it to contemporary themes; and to increase awareness of varied methodological perspectives on how to study work.

Similar content being viewed by others

Laying the Foundations to Build Ergonomic Indicators for Feminized Work in the Informal Sector

Women in the Workforce: A Global Snapshot

Work — In Progress

Explore related subjects.

- Artificial Intelligence

- Medical Ethics

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

In 2017, a group of (women) scholars held the 3rd of a series of workshops at the annual CSCW conference, in order to discuss feminist approaches to computer supported cooperative work (Fox et al. 2017 ). They viewed the workshop as an opportunity to develop feminist research and practice generally, and an intersectional feminist approach specifically - one that goes beyond understanding ‘women’ as a single monolithic category, and offers more than single axis frameworks for understanding oppression, and instead recognizes that the effects of oppression cannot be understood in isolation from one another. They suggested that ‘CSCW has come to embrace several forms of feminist thought’ (Fox et al. 2017 , p. 388).

At around the same time, based on our longstanding interest in studies of women’s work which dates back to the 1980’s, we thought about how to bring the large body of studies of women’s work to the attention of the CSCW community. There are long traditions of studying women’s work which remain little known in the CSCW community, yet rich in detail. As Star’s ( 1990 ) work so often illustrated, studying those who are ‘othered’ and invisible can lead to great insights about the nature of work and human interaction. Also, studying populations that have been neglected as subjects of study can yield insights from which the entire population can benefit. Finally, examining varied epistemological traditions which have informed fieldwork-based studies of women’s work serves as a rich backdrop through which we can explore often implicit assumptions about how people act and interact at work. Arguably, this can help us develop useful and meaningful CSCW systems.

Like Fox et al. ( 2017 ), we seek to contribute to the dialogue about feminist research and practice within CSCW. In contrast to their forward-looking efforts, here we look back. We seek to provide an historical, methodological and epistemological context which can help guide contemporary CSCW researchers as they explore the roots of their field of study. Additionally, through our historical account we hope to demonstrate to contemporary readers that while theory and method are sometimes treated separately in fieldwork, addressing both while exploring broader questions of context can lead to rich approaches and fresh insights. We are specifically interested in making varied intellectual traditions which have supported observationally based studies of women’s work in the past visible—particularly the work of non-anglophones, as these bodies of work have often remained invisible outside of the regions and language groups which have supported their development, yet they have much to contribute to CSCW practitioners.

1.1 Narrowing our focus

As CSCW as an area of inquiry has grown and evolved, so too have the topics it addresses, the methods of inquiry it has drawn on (which themselves have changed over time), and the theoretical insights which have informed research questions, research methods and analyses of results. Having both been engaged in early studies about women and computing, and observed changes over time in theory, methods, the topics explored within CSCW and of course the study of gender (which now includes, but is not limited to the study of women), we are compelled to both look back at past contributions which focus on women as subjects of study and what these contributed to CSCW, and to explore the context of those contributions in relation to what they can contribute to contemporary studies within CSCW.

Given this rich and varied body of research, we faced the challenge of deciding which of the many studies of women’s work to present in this paper and on which grounds. From the perspective of CSCW research, our main criterion was to focus on studies of women’s work which had a significant fieldwork component and on research that describes the work women engage with at some level of detail. We chose this focus largely because observational work undertaken from an anthropological perspective was a key element of the evolution of CSCW. However, (arguably), as observational methods gained acceptance within more mainstream computer science, the link between the theoretical bodies which gave rise to the use of these methods within CSCW have fallen from view, leaving more recent entrants to the field of CSCW lacking awareness of some of the rich traditions of the past, and how those traditions, when combined with a focus on women as subjects of study, led to insights within CSCW which remain salient today. Methodologically, this proved an interesting challenge, as norms of scholarship have evolved over time, and many early studies lacked details about methods used.

A second criterion in choosing studies to consider here was that work we have included provides insight into the wider context in which women’s work takes place. Our idea was to look for research that takes account of women’s waged work but also the reproductive work done in the family, and that, most importantly, addresses the key issues of the larger debates feminist scholars have contributed to with the intent to ‘document the importance of women workers while establishing women’s roles as active and autonomous agents in labor’s history’ (French and James 1997 , p. 3).

These two criteria—studies which were based on fieldwork, and which, through their focus on women’s paid and unpaid work documented women’s active roles, gave rise to the three aims of this paper:

to make this diversity of studies visible and with it the topics/issues researchers of women’s work engaged with in the past, and highlight the relevance of those topics for contemporary CSCW research;

to assume an historical perspective with the aim of providing a thematic historiography of studies of women’s work, thereby also demonstrating the value of an historical perspective, and offering a means through which to link it to contemporary themes; and

to increase awareness of varied methodological perspectives on how to study work.