Health Thesis Statemen

Ai generator.

Navigating the intricate landscape of health topics requires a well-structured thesis statement to anchor your essay. Whether delving into public health policies or examining medical advancements, crafting a compelling health thesis statement is crucial. This guide delves into exemplary health thesis statement examples, providing insights into their composition. Additionally, it offers practical tips on constructing powerful statements that not only capture the essence of your research but also engage readers from the outset.

What is the Health Thesis Statement? – Definition

A health thesis statement is a concise declaration that outlines the main argument or purpose of an essay or research paper thesis statement focused on health-related topics. It serves as a roadmap for the reader, indicating the central idea that the paper will explore, discuss, or analyze within the realm of health, medicine, wellness, or related fields.

What is an Example of a Medical/Health Thesis Statement?

Example: “The implementation of comprehensive public health campaigns is imperative in curbing the escalating rates of obesity and promoting healthier lifestyle choices among children and adolescents.”

In this example, the final thesis statement succinctly highlights the importance of public health initiatives as a means to address a specific health issue (obesity) and advocate for healthier behaviors among a targeted demographic (children and adolescents).

100 Health Thesis Statement Examples

Size: 191 KB

Discover a comprehensive collection of 100 distinct health thesis statement examples across various healthcare realms. From telemedicine’s impact on accessibility to genetic research’s potential for personalized medicine, delve into obesity, mental health, antibiotic resistance, opioid epidemic solutions, and more. Explore these examples that shed light on pressing health concerns, innovative strategies, and crucial policy considerations. You may also be interested to browse through our other speech thesis statement .

- Childhood Obesity : “Effective school-based nutrition programs are pivotal in combating childhood obesity, fostering healthy habits, and reducing the risk of long-term health complications.”

- Mental Health Stigma : “Raising awareness through media campaigns and educational initiatives is paramount in eradicating mental health stigma, promoting early intervention, and improving overall well-being.”

- Universal Healthcare : “The implementation of universal healthcare systems positively impacts population health, ensuring access to necessary medical services for all citizens.”

- Elderly Care : “Creating comprehensive elderly care programs that encompass medical, social, and emotional support enhances the quality of life for aging populations.”

- Cancer Research : “Increased funding and collaboration in cancer research expedite advancements in treatment options and improve survival rates for patients.”

- Maternal Health : “Elevating maternal health through accessible prenatal care, education, and support systems reduces maternal mortality rates and improves neonatal outcomes.”

- Vaccination Policies : “Mandatory vaccination policies safeguard public health by curbing preventable diseases and maintaining herd immunity.”

- Epidemic Preparedness : “Developing robust epidemic preparedness plans and international cooperation mechanisms is crucial for timely responses to emerging health threats.”

- Access to Medications : “Ensuring equitable access to essential medications, especially in low-income regions, is pivotal for preventing unnecessary deaths and improving overall health outcomes.”

- Healthy Lifestyle Promotion : “Educational campaigns promoting exercise, balanced nutrition, and stress management play a key role in fostering healthier lifestyles and preventing chronic diseases.”

- Health Disparities : “Addressing health disparities through community-based interventions and equitable healthcare access contributes to a fairer distribution of health resources.”

- Elderly Mental Health : “Prioritizing mental health services for the elderly population reduces depression, anxiety, and cognitive decline, enhancing their overall quality of life.”

- Genetic Counseling : “Accessible genetic counseling services empower individuals to make informed decisions about their health, family planning, and potential genetic risks.”

- Substance Abuse Treatment : “Expanding availability and affordability of substance abuse treatment facilities and programs is pivotal in combating addiction and reducing its societal impact.”

- Patient Empowerment : “Empowering patients through health literacy initiatives fosters informed decision-making, improving treatment adherence and overall health outcomes.”

- Environmental Health : “Implementing stricter environmental regulations reduces exposure to pollutants, protecting public health and mitigating the risk of respiratory illnesses.”

- Digital Health Records : “The widespread adoption of digital health records streamlines patient information management, enhancing communication among healthcare providers and improving patient care.”

- Healthy Aging : “Promoting active lifestyles, social engagement, and cognitive stimulation among the elderly population contributes to healthier aging and reduced age-related health issues.”

- Telehealth Ethics : “Ethical considerations in telehealth services include patient privacy, data security, and maintaining the quality of remote medical consultations.”

- Public Health Campaigns : “Strategically designed public health campaigns raise awareness about prevalent health issues, motivating individuals to adopt healthier behaviors and seek preventive care.”

- Nutrition Education : “Integrating nutrition education into school curricula equips students with essential dietary knowledge, reducing the risk of nutrition-related health problems.”

- Healthcare Infrastructure : “Investments in healthcare infrastructure, including medical facilities and trained personnel, enhance healthcare access and quality, particularly in underserved regions.”

- Mental Health Support in Schools : “Introducing comprehensive mental health support systems in schools nurtures emotional well-being, reduces academic stress, and promotes healthy student development.”

- Antibiotic Stewardship : “Implementing antibiotic stewardship programs in healthcare facilities preserves the effectiveness of antibiotics, curbing the rise of antibiotic-resistant infections.”

- Health Education in Rural Areas : “Expanding health education initiatives in rural communities bridges the information gap, enabling residents to make informed health choices.”

- Global Health Initiatives : “International collaboration on global health initiatives bolsters disease surveillance, preparedness, and response to protect global populations from health threats.”

- Access to Clean Water : “Ensuring access to clean water and sanitation facilities improves public health by preventing waterborne diseases and enhancing overall hygiene.”

- Telemedicine and Mental Health : “Leveraging telemedicine for mental health services increases access to therapy and counseling, particularly for individuals in remote areas.”

- Chronic Disease Management : “Comprehensive chronic disease management programs enhance patients’ quality of life by providing personalized care plans and consistent medical support.”

- Healthcare Workforce Diversity : “Promoting diversity within the healthcare workforce enhances cultural competence, patient-provider communication, and overall healthcare quality.”

- Community Health Centers : “Establishing community health centers in underserved neighborhoods ensures accessible primary care services, reducing health disparities and emergency room utilization.”

- Youth Health Education : “Incorporating comprehensive health education in schools equips young people with knowledge about reproductive health, substance abuse prevention, and mental well-being.”

- Dietary Guidelines : “Implementing evidence-based dietary guidelines and promoting healthy eating habits contribute to reducing obesity rates and preventing chronic diseases.”

- Healthcare Innovation : “Investing in healthcare innovation, such as telemedicine platforms and wearable health technologies, transforms patient care delivery and monitoring.”

- Pandemic Preparedness : “Effective pandemic preparedness plans involve cross-sector coordination, rapid response strategies, and transparent communication to protect global health security.”

- Maternal and Child Nutrition : “Prioritizing maternal and child nutrition through government programs and community initiatives leads to healthier pregnancies and better child development.”

- Health Literacy : “Improving health literacy through accessible health information and education empowers individuals to make informed decisions about their well-being.”

- Medical Research Funding : “Increased funding for medical research accelerates scientific discoveries, leading to breakthroughs in treatments and advancements in healthcare.”

- Reproductive Health Services : “Accessible reproductive health services, including family planning and maternal care, improve women’s health outcomes and support family well-being.”

- Obesity Prevention in Schools : “Introducing physical activity programs and nutritional education in schools prevents childhood obesity, laying the foundation for healthier lifestyles.”

- Global Vaccine Distribution : “Ensuring equitable global vaccine distribution addresses health disparities, protects vulnerable populations, and fosters international cooperation.”

- Healthcare Ethics : “Ethical considerations in healthcare decision-making encompass patient autonomy, informed consent, and equitable resource allocation.”

- Aging-in-Place Initiatives : “Aging-in-place programs that provide home modifications and community support enable elderly individuals to maintain independence and well-being.”

- E-Health Records Privacy : “Balancing the benefits of electronic health records with patients’ privacy concerns necessitates robust data security measures and patient consent protocols.”

- Tobacco Control : “Comprehensive tobacco control measures, including high taxation and anti-smoking campaigns, reduce tobacco consumption and related health risks.”

- Epidemiological Studies : “Conducting rigorous epidemiological studies informs public health policies, identifies risk factors, and guides disease prevention strategies.”

- Organ Transplant Policies : “Ethical organ transplant policies prioritize equitable organ allocation, ensuring fair access to life-saving treatments.”

- Workplace Wellness Programs : “Implementing workplace wellness programs promotes employee health, reduces absenteeism, and enhances productivity.”

- Emergency Medical Services : “Strengthening emergency medical services infrastructure ensures timely responses to medical crises, saving lives and reducing complications.”

- Healthcare Access for Undocumented Immigrants : “Expanding healthcare access for undocumented immigrants improves overall community health and prevents communicable disease outbreaks.”

- Primary Care Shortage Solutions : “Addressing primary care shortages through incentives for healthcare professionals and expanded training programs enhances access to basic medical services.”

- Patient-Centered Care : “Prioritizing patient-centered care emphasizes communication, shared decision-making, and respecting patients’ preferences in medical treatments.”

- Nutrition Labels Impact : “The effectiveness of clear and informative nutrition labels on packaged foods contributes to healthier dietary choices and reduced obesity rates.”

- Stress Management Strategies : “Promoting stress management techniques, such as mindfulness and relaxation, improves mental health and reduces the risk of stress-related illnesses.”

- Access to Reproductive Health Education : “Ensuring access to comprehensive reproductive health education empowers individuals to make informed decisions about their sexual and reproductive well-being.”

- Medical Waste Management : “Effective medical waste management practices protect both public health and the environment by preventing contamination and pollution.”

- Preventive Dental Care : “Prioritizing preventive dental care through community programs and education reduces oral health issues and associated healthcare costs.”

- Pharmaceutical Pricing Reform : “Addressing pharmaceutical pricing reform enhances medication affordability and ensures access to life-saving treatments for all.”

- Community Health Worker Role : “Empowering community health workers to provide education, support, and basic medical services improves healthcare access in underserved areas.”

- Healthcare Technology Adoption : “Adopting innovative healthcare technologies, such as AI-assisted diagnostics, enhances accuracy, efficiency, and patient outcomes in medical practices.”

- Elderly Falls Prevention : “Implementing falls prevention programs for the elderly population reduces injuries, hospitalizations, and healthcare costs, enhancing their overall well-being.”

- Healthcare Data Privacy Laws : “Stricter healthcare data privacy laws protect patients’ sensitive information, maintaining their trust and promoting transparent data management practices.”

- School Health Clinics : “Establishing health clinics in schools provides easy access to medical services for students, promoting early detection and timely treatment of health issues.”

- Healthcare Cultural Competence : “Cultivating cultural competence among healthcare professionals improves patient-provider communication, enhances trust, and reduces healthcare disparities.”

- Health Equity in Clinical Trials : “Ensuring health equity in clinical trials by diverse participant representation enhances the generalizability of research findings to different populations.”

- Digital Mental Health Interventions : “Utilizing digital mental health interventions, such as therapy apps, expands access to mental health services and reduces stigma surrounding seeking help.”

- Aging and Neurodegenerative Diseases : “Exploring the connection between aging and neurodegenerative diseases informs early interventions and treatment strategies to mitigate cognitive decline.”

- Healthcare Waste Reduction : “Implementing sustainable healthcare waste reduction measures decreases environmental impact and contributes to a greener healthcare industry.”

- Medical Ethics in End-of-Life Care : “Ethical considerations in end-of-life care decision-making ensure patient autonomy, quality of life, and respectful treatment choices.”

- Healthcare Interoperability : “Enhancing healthcare data interoperability between different medical systems and providers improves patient care coordination and information sharing.”

- Healthcare Disparities in Indigenous Communities : “Addressing healthcare disparities in Indigenous communities through culturally sensitive care and community engagement improves health outcomes.”

- Music Therapy in Healthcare : “Exploring the role of music therapy in healthcare settings reveals its positive effects on reducing pain, anxiety, and enhancing emotional well-being.”

- Healthcare Waste Management Policies : “Effective healthcare waste management policies regulate the disposal of medical waste, protecting both public health and the environment.”

- Agricultural Practices and Public Health : “Analyzing the impact of agricultural practices on public health highlights the connections between food production, environmental health, and nutrition.”

- Online Health Information Reliability : “Promoting the reliability of online health information through credible sources and fact-checking guides empowers individuals to make informed health decisions.”

- Neonatal Intensive Care : “Advancements in neonatal intensive care technology enhance premature infants’ chances of survival and long-term health.”

- Fitness Technology : “The integration of fitness technology in daily routines motivates individuals to engage in physical activity, promoting better cardiovascular health.”

- Climate Change and Health : “Examining the health effects of climate change emphasizes the need for mitigation strategies to protect communities from heat-related illnesses, vector-borne diseases, and other climate-related health risks.”

- Healthcare Cybersecurity : “Robust cybersecurity measures in healthcare systems safeguard patient data and protect against cyberattacks that can compromise medical records.”

- Healthcare Quality Metrics : “Evaluating healthcare quality through metrics such as patient satisfaction, outcomes, and safety indicators informs continuous improvement efforts in medical facilities.”

- Maternal Health Disparities : “Addressing maternal health disparities among different racial and socioeconomic groups through accessible prenatal care and support reduces maternal mortality rates.”

- Disaster Preparedness : “Effective disaster preparedness plans in healthcare facilities ensure timely responses during emergencies, minimizing casualties and maintaining patient care.”

- Sleep Health : “Promoting sleep health education emphasizes the importance of quality sleep in overall well-being, preventing sleep-related disorders and associated health issues.”

- Healthcare AI Ethics : “Navigating the ethical implications of using artificial intelligence in healthcare, such as diagnosis algorithms, safeguards patient privacy and accuracy.”

- Pediatric Nutrition : “Prioritizing pediatric nutrition education encourages healthy eating habits from a young age, reducing the risk of childhood obesity and related health concerns.”

- Mental Health in First Responders : “Providing mental health support for first responders acknowledges the psychological toll of their work, preventing burnout and trauma-related issues.”

- Healthcare Workforce Burnout : “Addressing healthcare workforce burnout through organizational support, manageable workloads, and mental health resources improves patient care quality.”

- Vaccine Hesitancy : “Effective strategies to address vaccine hesitancy involve transparent communication, education, and addressing concerns to maintain vaccination rates and community immunity.”

- Climate-Resilient Healthcare Facilities : “Designing climate-resilient healthcare facilities prepares medical centers to withstand extreme weather events and ensure continuous patient care.”

- Nutrition in Aging : “Emphasizing balanced nutrition among the elderly population supports healthy aging, preventing malnutrition-related health complications.”

- Medication Adherence Strategies : “Implementing medication adherence strategies, such as reminder systems and simplified regimens, improves treatment outcomes and reduces hospitalizations.”

- Crisis Intervention : “Effective crisis intervention strategies in mental health care prevent escalations, promote de-escalation techniques, and improve patient safety.”

- Healthcare Waste Recycling : “Promoting healthcare waste recycling initiatives reduces landfill waste, conserves resources, and minimizes the environmental impact of medical facilities.”

- Healthcare Financial Accessibility : “Strategies to enhance healthcare financial accessibility, such as sliding scale fees and insurance coverage expansion, ensure equitable care for all.”

- Palliative Care : “Prioritizing palliative care services improves patients’ quality of life by addressing pain management, symptom relief, and emotional support.”

- Healthcare and Artificial Intelligence : “Exploring the integration of artificial intelligence in diagnostics and treatment planning enhances medical accuracy and reduces human error.”

- Personalized Medicine : “Advancements in personalized medicine tailor treatments based on individual genetics and characteristics, leading to more precise and effective healthcare.”

- Patient Advocacy : “Empowering patients through education and advocacy training enables them to navigate the healthcare system and actively participate in their treatment decisions.”

- Healthcare Waste Reduction : “Promoting the reduction of healthcare waste through sustainable practices and responsible disposal methods minimizes environmental and health risks.”

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine : “Examining the efficacy and safety of complementary and alternative medicine approaches provides insights into their potential role in enhancing overall health and well-being.”

Thesis Statement Examples for Physical Health

Discover 10 unique good thesis statement examples that delve into physical health, from the impact of fitness technology on exercise motivation to the importance of nutrition education in preventing chronic illnesses. Explore these examples shedding light on the pivotal role of physical well-being in disease prevention and overall quality of life.

- Fitness Technology’s Influence : “The integration of fitness technology like wearable devices enhances physical health by fostering exercise adherence, tracking progress, and promoting active lifestyles.”

- Nutrition Education’s Role : “Incorporating comprehensive nutrition education in schools equips students with essential dietary knowledge, reducing the risk of nutrition-related health issues.”

- Active Lifestyle Promotion : “Public spaces and urban planning strategies that encourage physical activity contribute to community health and well-being, reducing sedentary behavior.”

- Sports Injuries Prevention : “Strategic implementation of sports injury prevention programs and adequate athlete conditioning minimizes the incidence of sports-related injuries, preserving physical well-being.”

- Physical Health in Workplace : “Prioritizing ergonomic design and promoting workplace physical activity positively impact employees’ physical health, reducing musculoskeletal issues and stress-related ailments.”

- Childhood Obesity Mitigation : “School-based interventions, including physical education and health education, play a pivotal role in mitigating childhood obesity and promoting lifelong physical health.”

- Outdoor Activity and Wellness : “Unstructured outdoor play, especially in natural settings, fosters children’s physical health, cognitive development, and emotional well-being.”

- Senior Nutrition and Mobility : “Tailored nutrition plans and physical activity interventions for seniors support physical health, mobility, and independence during the aging process.”

- Health Benefits of Active Commuting : “Promotion of active commuting modes such as walking and cycling improves cardiovascular health, reduces pollution, and enhances overall well-being.”

- Physical Health’s Longevity Impact : “Sustaining physical health through regular exercise, balanced nutrition, and preventive measures positively influences longevity, ensuring a higher quality of life.”

Thesis Statement Examples for Health Protocols

Explore 10 thesis statement examples that highlight the significance of health protocols, encompassing infection control in medical settings to the ethical guidelines for telemedicine practices. These examples underscore the pivotal role of health protocols in ensuring patient safety, maintaining effective healthcare practices, and preventing the spread of illnesses across various contexts. You should also take a look at our thesis statement for report .

- Infection Control and Patient Safety : “Rigorous infection control protocols in healthcare settings are paramount to patient safety, curbing healthcare-associated infections and maintaining quality care standards.”

- Evidence-Based Treatment Guidelines : “Adhering to evidence-based treatment guidelines enhances medical decision-making, improves patient outcomes, and promotes standardized, effective healthcare practices.”

- Ethics in Telemedicine : “Establishing ethical guidelines for telemedicine practices is crucial to ensure patient confidentiality, quality of care, and responsible remote medical consultations.”

- Emergency Response Preparedness : “Effective emergency response protocols in healthcare facilities ensure timely and coordinated actions, optimizing patient care, and minimizing potential harm.”

- Clinical Trial Integrity : “Stringent adherence to health protocols in clinical trials preserves data integrity, ensures participant safety, and upholds ethical principles in medical research.”

- Safety in Daycare Settings : “Implementing robust infection prevention protocols in daycare settings is vital to curb disease transmission, safeguarding the health of children and staff.”

- Privacy and E-Health : “Upholding stringent patient privacy protocols in electronic health records is paramount for data security, fostering trust, and maintaining confidentiality.”

- Hand Hygiene and Infection Prevention : “Promoting proper hand hygiene protocols among healthcare providers significantly reduces infection transmission risks, protecting both patients and medical personnel.”

- Food Safety in Restaurants : “Strict adherence to comprehensive food safety protocols within the restaurant industry is essential to prevent foodborne illnesses and ensure public health.”

- Pandemic Preparedness and Response : “Developing robust pandemic preparedness protocols, encompassing risk assessment and response strategies, is essential to effectively manage disease outbreaks and protect public health.”

Thesis Statement Examples on Health Benefits

Uncover 10 illuminating thesis statement examples exploring the diverse spectrum of health benefits, from the positive impact of green spaces on mental well-being to the advantages of mindfulness practices in stress reduction. Delve into these examples that underscore the profound influence of health-promoting activities on overall physical, mental, and emotional well-being.

- Nature’s Impact on Mental Health : “The presence of green spaces in urban environments positively influences mental health by reducing stress, enhancing mood, and fostering relaxation.”

- Mindfulness for Stress Reduction : “Incorporating mindfulness practices into daily routines promotes mental clarity, reduces stress, and improves overall emotional well-being.”

- Social Interaction’s Role : “Engaging in regular social interactions and fostering strong social connections contributes to mental well-being, combating feelings of loneliness and isolation.”

- Physical Activity’s Cognitive Benefits : “Participation in regular physical activity enhances cognitive function, memory retention, and overall brain health, promoting lifelong mental well-being.”

- Positive Effects of Laughter : “Laughter’s physiological and psychological benefits, including stress reduction and improved mood, have a direct impact on overall mental well-being.”

- Nutrition’s Impact on Mood : “Balanced nutrition and consumption of mood-enhancing nutrients play a pivotal role in regulating mood and promoting positive mental health.”

- Creative Expression and Emotional Well-Being : “Engaging in creative activities, such as art and music, provides an outlet for emotional expression and fosters psychological well-being.”

- Cultural Engagement’s Influence : “Participating in cultural and artistic activities enriches emotional well-being, promoting a sense of identity, belonging, and purpose.”

- Volunteering and Mental Health : “Volunteering contributes to improved mental well-being by fostering a sense of purpose, social connection, and positive self-esteem.”

- Emotional Benefits of Pet Ownership : “The companionship of pets provides emotional support, reduces stress, and positively impacts overall mental well-being.”

Thesis Statement Examples on Mental Health

Explore 10 thought-provoking thesis statement examples delving into various facets of mental health, from addressing stigma surrounding mental illnesses to advocating for increased mental health support in schools. These examples shed light on the importance of understanding, promoting, and prioritizing mental health to achieve holistic well-being.

- Stigma Reduction for Mental Health : “Challenging societal stigma surrounding mental health encourages open dialogue, fostering acceptance, and creating a supportive environment for individuals seeking help.”

- Mental Health Education in Schools : “Incorporating comprehensive mental health education in school curricula equips students with emotional coping skills, destigmatizes mental health discussions, and supports overall well-being.”

- Mental Health Awareness Campaigns : “Strategically designed mental health awareness campaigns raise public consciousness, reduce stigma, and promote early intervention and access to support.”

- Workplace Mental Health Initiatives : “Implementing workplace mental health programs, including stress management and emotional support, enhances employee well-being and job satisfaction.”

- Digital Mental Health Interventions : “Leveraging digital platforms for mental health interventions, such as therapy apps and online support groups, increases accessibility and reduces barriers to seeking help.”

- Impact of Social Media on Mental Health : “Examining the influence of social media on mental health highlights both positive and negative effects, guiding responsible usage and promoting well-being.”

- Mental Health Disparities : “Addressing mental health disparities among different demographics through culturally sensitive care and accessible services is crucial for equitable well-being.”

- Trauma-Informed Care : “Adopting trauma-informed care approaches in mental health settings acknowledges the impact of past trauma, ensuring respectful and effective treatment.”

- Positive Psychology Interventions : “Incorporating positive psychology interventions, such as gratitude practices and resilience training, enhances mental well-being and emotional resilience.”

- Mental Health Support for First Responders : “Recognizing the unique mental health challenges faced by first responders and providing tailored support services is essential for maintaining their well-being.”

Thesis Statement Examples on Covid-19

Explore 10 illuminating thesis statement examples focusing on various aspects of the Covid-19 pandemic, from the impact on mental health to the role of public health measures. Delve into these examples that highlight the interdisciplinary nature of addressing the pandemic’s challenges and implications on global health.

- Mental Health Crisis Amid Covid-19 : “The Covid-19 pandemic’s psychological toll underscores the urgency of implementing mental health support services and destigmatizing seeking help.”

- Role of Public Health Measures : “Analyzing the effectiveness of public health measures, including lockdowns and vaccination campaigns, in curbing the spread of Covid-19 highlights their pivotal role in pandemic control.”

- Equitable Access to Vaccines : “Ensuring equitable access to Covid-19 vaccines globally is vital to achieving widespread immunity, preventing new variants, and ending the pandemic.”

- Online Education’s Impact : “Exploring the challenges and opportunities of online education during the Covid-19 pandemic provides insights into its effects on students’ academic progress and mental well-being.”

- Economic Implications and Mental Health : “Investigating the economic consequences of the Covid-19 pandemic on mental health highlights the need for comprehensive social support systems and mental health resources.”

- Crisis Communication Strategies : “Evaluating effective crisis communication strategies during the Covid-19 pandemic underscores the importance of transparent information dissemination, fostering public trust.”

- Long-Term Health Effects : “Understanding the potential long-term health effects of Covid-19 on recovered individuals guides healthcare planning and underscores the importance of ongoing monitoring.”

- Digital Health Solutions : “Leveraging digital health solutions, such as telemedicine and contact tracing apps, plays a pivotal role in tracking and managing Covid-19 transmission.”

- Resilience Amid Adversity : “Exploring individual and community resilience strategies during the Covid-19 pandemic sheds light on coping mechanisms and adaptive behaviors in times of crisis.”

- Global Cooperation in Pandemic Response : “Assessing global cooperation and collaboration in pandemic response highlights the significance of international solidarity and coordination in managing global health crises.”

Nursing Thesis Statement Examples

Explore 10 insightful thesis statement examples that delve into the dynamic realm of nursing, from advocating for improved nurse-patient communication to addressing challenges in healthcare staffing. These examples emphasize the critical role of nursing professionals in patient care, healthcare systems, and the continuous pursuit of excellence in the field.

- Nurse-Patient Communication Enhancement : “Elevating nurse-patient communication through effective communication training programs improves patient satisfaction, treatment adherence, and overall healthcare outcomes.”

- Nursing Leadership Impact : “Empowering nursing leadership in healthcare institutions fosters improved patient care, interdisciplinary collaboration, and the cultivation of a positive work environment.”

- Challenges in Nursing Shortages : “Addressing nursing shortages through recruitment strategies, retention programs, and educational support enhances patient safety and healthcare system stability.”

- Evidence-Based Nursing Practices : “Promoting evidence-based nursing practices enhances patient care quality, ensuring that interventions are rooted in current research and best practices.”

- Nursing Role in Preventive Care : “Harnessing the nursing profession’s expertise in preventive care and patient education reduces disease burden and healthcare costs, emphasizing a proactive approach.”

- Nursing Advocacy and Patient Rights : “Nurse advocacy for patients’ rights and informed decision-making ensures ethical treatment, patient autonomy, and respectful healthcare experiences.”

- Nursing Ethics and Dilemmas : “Navigating ethical dilemmas in nursing, such as end-of-life care decisions, highlights the importance of ethical frameworks and interdisciplinary collaboration.”

- Telehealth Nursing Adaptation : “Adapting nursing practices to telehealth platforms requires specialized training and protocols to ensure safe, effective, and patient-centered remote care.”

- Nurse Educators’ Impact : “Nurse educators play a pivotal role in shaping the future of nursing by providing comprehensive education, fostering critical thinking, and promoting continuous learning.”

- Mental Health Nursing Expertise : “The specialized skills of mental health nurses in assessment, intervention, and patient support contribute significantly to addressing the growing mental health crisis.”

Thesis Statement Examples for Health and Wellness

Delve into 10 thesis statement examples that explore the interconnectedness of health and wellness, ranging from the integration of holistic well-being practices in healthcare to the significance of self-care in preventing burnout. These examples highlight the importance of fostering balance and proactive health measures for individuals and communities.

- Holistic Health Integration : “Incorporating holistic health practices, such as mindfulness and nutrition, within conventional healthcare models supports comprehensive well-being and disease prevention.”

- Self-Care’s Impact on Burnout : “Prioritizing self-care among healthcare professionals reduces burnout, enhances job satisfaction, and ensures high-quality patient care delivery.”

- Community Wellness Initiatives : “Community wellness programs that address physical, mental, and social well-being contribute to healthier populations and reduced healthcare burdens.”

- Wellness in Aging Populations : “Tailored wellness programs for the elderly population encompass physical activity, cognitive stimulation, and social engagement, promoting healthier aging.”

- Corporate Wellness Benefits : “Implementing corporate wellness programs enhances employee health, morale, and productivity, translating into lower healthcare costs and higher job satisfaction.”

- Nutrition’s Role in Wellness : “Prioritizing balanced nutrition through education and accessible food options plays a pivotal role in overall wellness and chronic disease prevention.”

- Mental and Emotional Well-Being : “Fostering mental and emotional well-being through therapy, support networks, and stress management positively impacts overall health and life satisfaction.”

- Wellness Tourism’s Rise : “Exploring the growth of wellness tourism underscores the demand for travel experiences that prioritize rejuvenation, relaxation, and holistic well-being.”

- Digital Health for Wellness : “Leveraging digital health platforms for wellness, such as wellness apps and wearable devices, empowers individuals to monitor and enhance their well-being.”

- Equitable Access to Wellness : “Promoting equitable access to wellness resources and facilities ensures that all individuals, regardless of socioeconomic status, can prioritize their health and well-being.”

What is a good thesis statement about mental health?

A thesis statement about mental health is a concise and clear declaration that encapsulates the main point or argument you’re making in your essay or research paper related to mental health. It serves as a roadmap for your readers, guiding them through the content and focus of your work. Crafting a strong thesis statement about mental health involves careful consideration of the topic and a clear understanding of the points you’ll discuss. Here’s how you can create a good thesis statement about mental health:

- Choose a Specific Focus : Mental health is a broad topic. Determine the specific aspect of mental health you want to explore, whether it’s the impact of stigma, the importance of access to treatment, the role of mental health in overall well-being, or another angle.

- Make a Debatable Assertion : A thesis statement should present an argument or perspective that can be debated or discussed. Avoid statements that are overly broad or universally accepted.

- Be Clear and Concise : Keep your thesis statement concise while conveying your main idea. It’s usually a single sentence that provides insight into the content of your paper.

- Provide Direction : Your thesis statement should indicate the direction your paper will take. It’s like a roadmap that tells your readers what to expect.

- Make it Strong : Strong thesis statements are specific, assertive, and supported by evidence. Don’t shy away from taking a clear stance on the topic.

- Revise and Refine : As you draft your paper, your understanding of the topic might evolve. Your thesis statement may need revision to accurately reflect your arguments.

How do you write a Health Thesis Statement? – Step by Step Guide

Crafting a strong health thesis statement requires a systematic approach. Follow these steps to create an effective health thesis statement:

- Choose a Health Topic : Select a specific health-related topic that interests you and aligns with your assignment or research objective.

- Narrow Down the Focus : Refine the topic to a specific aspect. Avoid overly broad statements; instead, zoom in on a particular issue.

- Identify Your Stance : Determine your perspective on the topic. Are you advocating for a particular solution, analyzing causes and effects, or comparing different viewpoints?

- Formulate a Debatable Assertion : Develop a clear and arguable statement that captures the essence of your position on the topic.

- Consider Counterarguments : Anticipate counterarguments and incorporate them into your thesis statement. This adds depth and acknowledges opposing views.

- Be Concise and Specific : Keep your thesis statement succinct while conveying the main point. Avoid vague language or generalities.

- Test for Clarity : Share your thesis statement with someone else to ensure it’s clear and understandable to an audience unfamiliar with the topic.

- Refine and Revise : Your thesis statement is not set in stone. As you research and write, you might find it necessary to revise and refine it to accurately reflect your evolving arguments.

Tips for Writing a Thesis Statement on Health Topics

Writing a thesis statement on health topics requires precision and careful consideration. Here are some tips to help you craft an effective thesis statement:

- Be Specific : Address a specific aspect of health rather than a broad topic. This allows for a more focused and insightful thesis statement.

- Take a Stance : Your thesis statement should present a clear perspective or argument. Avoid vague statements that don’t express a stance.

- Avoid Absolute Statements : Be cautious of using words like “always” or “never.” Instead, use language that acknowledges complexity and nuance.

- Incorporate Keywords : Include keywords that indicate the subject of your research, such as “nutrition,” “mental health,” “public health,” or other relevant terms.

- Preview Supporting Points : Your thesis statement can preview the main points or arguments you’ll discuss in your paper, providing readers with a roadmap.

- Revise as Necessary : Your thesis statement may evolve as you research and write. Don’t hesitate to revise it to accurately reflect your findings.

- Stay Focused : Ensure that your thesis statement remains directly relevant to your topic throughout your writing.

Remember that your thesis statement is the foundation of your paper. It guides your research and writing process, helping you stay on track and deliver a coherent argument.

Text prompt

- Instructive

- Professional

10 Examples of Public speaking

20 Examples of Gas lighting

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- BMJ Journals

You are here

- Volume 59, Issue 7

- Wealth and health: the need for more strategic public health research

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Correspondence to: Professor F Baum Department of Public Health, Flinders University, GPO Box 2100, Adelaide 5001, Australia; fran.baumflinders.edu.au

This article argues that public health researchers have often ignored the analysis of wealth in the quest to understand the social determinants of health. Wealth concentration and the inequities in wealth between and within countries are increasing. Despite this scare accurate data are available to assist the analysis of the health impact of this trend. Improved data collection on wealth distribution should be encouraged. Epidemiologists and political economy of health researchers should pay more attention to understanding the dynamics of wealth and its consequences for population health. Policy research to underpin policies designed to reduce inequities in wealth distribution should be intensified.

- inequalities

- health status

- political economy

https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.021147

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

↵ * Inequality is concerned with difference so that equality is about sameness. Inequity is concerned with fairness and ethical considerations stemming from inequalities. The terms are often used interchangeably in the literature on disparities in health status.

Funding: none.

Conflicts of interest: none declared.

Linked Articles

- In this issue Complexity, ecology, the environment, and isn't it time to study the wealthy? Carlos Alvarez-Dardet John R Ashton Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health 2005; 59 533-533 Published Online First: 17 Jun 2005.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

The Aspen Institute

©2024 The Aspen Institute. All Rights Reserved

- 0 Comments Add Your Comment

Exploring the Important Link Between Health and Wealth

November 5, 2019 • Rhett Buttle & Financial Security Program

Over the past several months, the Aspen Institute’s prestigious programs, the Financial Security Program and the Health, Medicine and Society Program, embarked on a unique collaboration to explore the link between good health and financial wellbeing.

The connection between financial wellness and health is significant, with evidence showing that increased financial security is linked to improved health outcomes and improved quality of life. What’s more, finance and health are among the fastest-growing sectors of the economy — in the US, they comprise more than 40 percent of GDP — and both are targets of innovation.

Research has found that more than half of an individual’s life expectancy in the DC region could be explained by education and economic factors. According to another report, income growth not only correlates to life expectancy increases, but also to a decrease in the risk of chronic illness and an increase in access to resources that promote longevity and health. Other research has shown that financial insecurity is a serious source of mental stress, reducing an individual’s productivity and job performance. And yet more research notes that poor physical health directly impacts financial stability, increasing the likelihood of personal bankruptcy from medical debt.

Stakeholders across public, private, and philanthropic sectors are increasingly convinced of the necessity of a multidisciplinary approach that would result in solutions designed to tackle issues related to both economic and health inequality. Some of these efforts are being driven by the changes we are seeing in our economy — for example, the growth of the “gig” economy, high levels of debt, record income disparities, and challenges to retirement security that are all leaving their mark on an individual’s health. With economic structures in transition, entrepreneurs are beginning to link up with care providers and health advocates are promoting microenterprise. So, what does the link between health and wealth mean in this evolving economy?

Given these developments and questions, our collaboration sought to explore the connection between these two fields. Our work has manifested itself in two ways.

A Set of Exploratory Roundtables

First, the programs co-hosted a set of roundtables — one in Washington, DC, and one in San Francisco, CA — with key stakeholders from both fields. Each roundtable included approximately 20 to 30 sharp minds, including public health, healthcare, and financial security leaders from across academia, business, community-based and advocacy organizations, and other appropriate experts. The roundtables began a necessary dialogue, promoted an open space, and fostered trust in order to identify and discover areas of partnership.

Integrating Health & Wealth into the Aspen Ideas Festival

In addition to the roundtables, we brought the conversation to Aspen Ideas: Health (the three-day opening event of the Aspen Ideas Festival). There, we produced a track (or “theme”) focused exclusively on Health & Wealth. Content included a conversation with the US Surgeon General and the President of the Federal Reserve of Philadelphia, who explored ways that their jobs and missions are both fundamentally geared toward advancing the health of America’s families, communities, and economy. We also featured several business leaders who spoke to the business case for thinking about health and wealth together, and how both sectors can do more to ensure that the end goal of business aligns with helping households experience greater wellbeing. Another panel looked at how a living wage can create better health outcomes, and another explored how the growing burden of medical debt is one of the most common financial burdens for Americans. Attendees left increasingly aware that health and financial wellness are fundamentally linked.

What’s Next

These times require an authentic conversation about the substantial financial challenges facing our families — and increasing financial insecurity more broadly. Examining the connection between health and financial security is at the heart of this — and, we believe, the right place to start.

It is our hope that in partnership with several of the Institute’s policy programs — the Financial Security Program and the Health, Medicine and Society Program — we can explore an effort that combines each program’s networks, learnings, and expertise. Working together, the programs can move forward with the opportunity to examine the common essential building blocks of healthcare, medicine, wellness, and financial well-being. The true power in this effort comes from the ability to examine problems in new ways, integrate networks, and explore innovative solutions that stem from real collaboration. Through public convenings — and intensive, off-the-record dialogues with leaders from a wide cross-section of private, public, and nonprofit institutions — the Aspen Institute can play a lead role in advancing a conversation on how to improve health and wealth in tandem.

Long-lasting improvement on the issues of financial and health inequality requires multidisciplinary solutions that embrace the inter-relatedness of these issues. Improving health outcomes will allow people to live longer and healthier lives, and participate more fully in the economy. Coming together with a diverse set of committed leaders, we can effect change and improve the lives of millions.

Related Posts

August 13, 2024 Kate Griffin & 1 more

July 18, 2024 Financial Security Program

The best of the Institute, right in your inbox.

Sign up for our email newsletter

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Cambridge Open

IS THE LINK BETWEEN HEALTH AND WEALTH CONSIDERED IN DECISION MAKING? RESULTS FROM A QUALITATIVE STUDY

Martina garau.

Office of Health Economics, Email: gro.eho@uaragm

Koonal Kirit Shah

Office of Health Economics

Priya Sharma

United States Agency for International Development

Adrian Towse

Associated data.

For supplementary material accompanying this paper visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0266462315000616.

Objectives: The aim of this study was to explore whether wealth effects of health interventions, including productivity gains and savings in other sectors, are considered in resource allocations by health technology assessment (HTA) agencies and government departments. To analyze reasons for including, or not including, wealth effects.

Methods: Semi-structured interviews with decision makers and academic experts in eight countries (Australia, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, South Korea, Sweden, and the United Kingdom).

Results: There is evidence suggesting that health interventions can produce economic gains for patients and national economies. However, we found that the link between health and wealth does not influence decision making in any country with the exception of Sweden. This is due to a combination of factors, including system fragmentation, methodological issues, and the economic recession forcing national governments to focus on short-term measures.

Conclusions: In countries with established HTA processes and methods allowing, in principle, the inclusion of wider effects in exceptional cases or secondary analyses, it might be possible to overcome the methodological and practical barriers and see a more systematic consideration of wealth effect in decision making. This would be consistent with principles of efficient priority setting. Barriers for the consideration of wealth effects in government decision making are more fundamental, due to an enduring separation of budgets within the public sector and current financial pressures. However, governments should consider all relevant effects from public investments, including healthcare, even when benefits can only be captured in the medium- and long-term. This will ensure that resources are allocated where they bring the best returns.

AIM OF THE STUDY

Traditionally, the primary outcome of health interventions considered by decision makers is the impact on patients’ health in terms of reduced morbidity or mortality. Additionally, interventions can generate “wealth effects” (also referred to as indirect costs, nonhealth benefits, or wider societal effects) which extend beyond the health gains accruing to patients. Wealth effects include: improvements in the labor productivity of patients and of their caregivers; cost savings to healthcare, social care, and other sectors; and increases in national income.

In 2003, David Byrne, the then European Commissioner for Health and Consumer Protection, delivered a speech that focused on the importance of health as a “driver of economic prosperity” for European Union (EU) Member States ( 1 ). There is a growing body of research aimed at demonstrating the interdependencies between health and wealth ( 2 – 4 ). However, we are not aware of any published studies of whether the consideration of wealth effects, as defined above, has had an impact on resource allocation decisions in practice. This study examines the extent to which the link between health and wealth has influenced national decision making in a sample of eight countries.

We focused on three types of decision makers: health technology assessment (HTA) agencies which make recommendations about the use and/or public reimbursement of health interventions; Health Ministries that run national health systems and in some cases allocate resources across separate health system components; and Finance Ministries/Treasuries that control the budgets of government departments.

CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

We began by developing a categorization of potential wealth effects based on the published literature. We identified relevant articles by following up the references in recent reviews and comprehensive analyses of the impact of health on economic growth in high-income countries, labor productivity and other indirect costs in economic evaluations ( 5 – 9 ). We identified further publications by conducting searches of Google Scholar using the keywords and abstract terms from these studies.

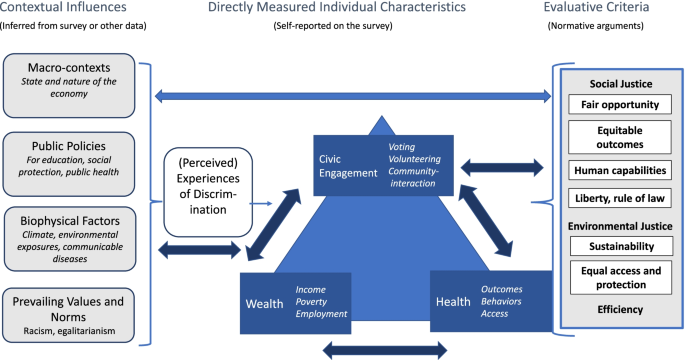

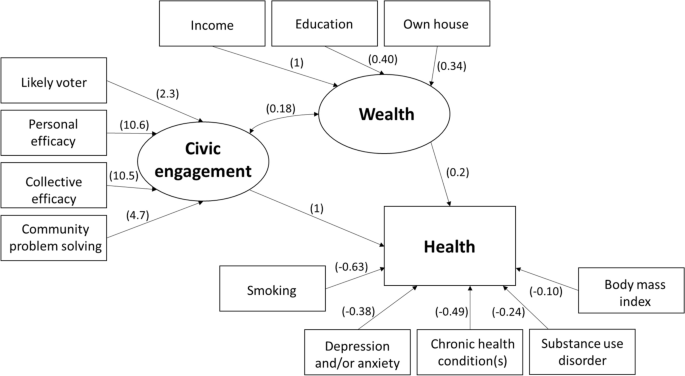

Figure 1 presents our conceptual framework. It illustrates that in addition to health effects such as reducing morbidity or mortality ( Figure 1 , box A), health interventions can also produce a variety of wealth effects.

Conceptual framework of the link between health and economic outcomes.

The economic costs of illness often fall on sectors other than the healthcare sector; the use of health interventions can lead to important cost savings to those sectors ( Figure 1 , box B). The resources freed up could then be used to provide additional services within the sector. For example, it has been shown that one of the key drivers of the cost of Alzheimer's disease (almost 40 percent) is the cost of social care provided in patients’ homes or in other community settings ( 10 ).

Despite evidence showing that indirect costs can constitute a significant proportion of the total cost of illness to society, the inclusion of those costs in economic evaluations remains limited. Stone et al. ( 11 ) found that productivity costs were considered in less than 10 percent of published cost-utility analyses.

Figure 1 also shows that at the macroeconomic level, a positive link may exist between the health of a population and the level of national income ( Figure 1 , box C). At the microeconomic level, healthcare interventions can have an impact on individuals or households by improving patients’ productivity at work (if they are of working age) and by reducing patients’ and carers’ absences from work due to ill health ( Figure 1 , box D). The arrow linking macro and micro effects indicates that some micro effects are captured at the macro level, for example, reducing sickness absence can improve individual firms’ production which can also contribute to national income growth. Some effects, however, such as time spent doing unpaid work (e.g., housework), tend only to be captured at the micro level.

Empirical evidence using a global sample of countries has shown that health, measured in terms of life expectancy, is a robust predictor of economic growth ( 12 – 15 ). However, the role of health seems to be stronger in the context of low- and medium-income countries compared with high-income countries, where evidence is limited and shows mixed results. For example, Knowles and Owen ( 16 ) found that life expectancy had a minor impact on the economic growth of a sample of high-income countries, while Bhargava et al. ( 17 ) found that above a certain level of income per capita in high-income countries, improvements in adult survival rates had a negative impact on growth rates.

The results of these types of studies should be interpreted with caution for two reasons. The first relates to the indicators used to measure population health, which in most studies is life expectancy or adult mortality. While there is wide variation in life expectancy between middle- and low-income countries, there is little variation among high-income countries. As a result, more relevant indicators of health are needed to capture the different levels of health in different high-income countries ( 4 ). An example of this is cardiovascular disease (CVD) mortality as used in a study by Suhrcke and Urban ( 18 ). They show that a 10 percent increase in CVD mortality among OECD countries reduces the per capita income growth rate by one percentage point. CVD mortality was used as a proxy for health for two reasons. The first was the large disease burden of noncommunicable diseases in OECD countries, CVD in particular. The second was the impact on labor productivity, as CVD affects individuals of working age.

The second reason relates to institutional factors that prevent countries from realizing the positive effects of health improvements. As life expectancy exceeds the retirement age by a growing margin, the old age dependency ratio increases, thus negatively impacting government fiscal stability and, indirectly, economic growth. One way to overcome this would be to increase the retirement age so that the improved health of older people can result in an increase of labor supply and productivity ( 19 ). Those policies have already been implemented or are under discussion in several countries.

The literature also explores the issue of casual effect between health and wealth and shows that higher income can increase consumption and provision of goods and services promoting health ( 6 ; 13 ). This effect will ultimately reinforce the importance of recognizing the role of improving health outcomes on national income, which can create a “virtual” cycle between health and wealth.

At the micro-economic level, ill health can affect individuals’ participation in the labor force in the short-term, long-term or permanently. This affects individuals’ ability to earn income for themselves and their family, to consume market goods and to engage in leisure activities. A body of literature estimates what are called “indirect costs” to society due to ill health. They include losses due to: (i) Reduced productivity at work (presenteeism): some illnesses, such as back pain and depression ( 9 ; 20 ), do not necessarily prevent individuals from attending work but may affect their on-the-job performance; (ii) Sickness absence (absenteeism): individuals who are suffering, recovering from illness, or who are undergoing treatment may require absence from work. For example, it is estimated that a major component of the cost of breast cancer is due to patients’ absence from work due to treatment-related symptoms ( 21 ); (iii) Non-employment / early retirement: illnesses that are particularly debilitating may result in individuals being unable to return to work (and, therefore, unable to produce output) on a permanent basis. For example, Kobelt ( 22 ) reported that 38 percent of the total cost of multiple sclerosis is due to lost productivity from early retirement.

The effects of ill health also apply to those providing informal (i.e., unpaid) care to patients ( 23 ). For example, when children attend hospital appointments, their parents often need to be absent from work to take them to their appointments.

We conducted semi-structured interviews with decision makers and academic experts in eight countries. The aim of the interviews was to explore whether the wealth effects of interventions identified in our conceptual framework represented in Figure 1 are considered by HTA agencies in their health technology evaluations, and by government departments in their budget setting decisions. We also asked about the reasons why these wealth effects were or were not considered. Wealth effects were defined as nonhealth, economic effects generated by the use of health interventions, including impacts on labor productivity and supply, and savings to other sectors.

The potential interviewees invited to participate included individuals representing one or more of the three categories of decision makers (HTA agencies, Health Ministries, Finance Ministries). All were either currently employed by the relevant body or ministry, or local academic experts directly involved in their country's HTA processes and/or in advising their country's Ministry of Health.

The initial geographical scope included countries with established or emerging HTA systems, and near universal health coverage: Australia, Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, South Korea, Sweden, Turkey, and the United Kingdom (UK). The final list of countries was based on whether invitees responded to our request for an interview. These were: Australia, France, Germany, Italy, Poland, South Korea, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

We developed two questionnaires, one to be used for the HTA or reimbursement decision makers and HTA experts (“Questionnaire for HTA decision makers/experts”; Supplementary Table 1 ); and the other to be used for the employees of Health and Finance Ministries who had little or no technical knowledge of HTA (“Questionnaire for Ministry of Health/Finance/experts”). The questionnaire for HTA decision makers/experts aimed at exploring whether effects on individuals/households (box D of Figure 1 ) generated by health interventions matter in the HTA processes of the interviewee's country; and if they are, which types of effects tend to be considered, in which diseases areas they are particularly important, what type of evidence is required to show their impact and what are the key issues encountered. Hypothetical interventions for three conditions were presented to illustrate those effects: Alzheimer's disease, breast cancer, and depression. The case studies were developed using data from recently published cost of illness studies ( 10 ; 21 ; 24 ). They focused on drug therapies, because many of the interviewees (particularly the HTA experts) were more familiar with the evaluation of drugs than of other types of health intervention, but it was emphasized to all interviewees that we were interested in the effects of all health interventions. In addition, the final question asked interviewees about the impact of new health interventions on national income (box C in Figure 1 ) and whether it mattered in the decision-making process they had experience of.

Categorization of Countries According to the Extent of Consideration of Wealth Effects in Resource Allocation Decisions

| Australia | France | Germany | Italy | Korea | Poland | Sweden | UK | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Considers wealth effects regularly | ✓ | |||||||

| Considers wealth effects in principle but rarely/never in practice | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Does not consider wealth effects within the HTA process or healthcare budget-setting decisions | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Does not currently consider any economic/cost data | ✓ |

The questionnaire for Ministry of Health/Finance/experts asked interviewees about how any effects of health interventions on nonhealth public sectors (box B of Figure 1 ) influence budget setting decisions, for example, whether resource transfers are possible when benefits from health spending are captured in other sectors. For the sake of simplicity, this questionnaire included only one case study (the hypothetical intervention for Alzheimer's disease).

Both questionnaires included open-ended questions. This enabled the interviewer to structure the interview by asking predefined questions, but also to pursue additional topics in more depth or to probe for information on themes emerging from the interviewers’ answers. The questionnaires were sent to the interviewees in advance of the hour-long telephone interview. Two researchers were present at all interviews. Summary notes of the interviews were sent to the interviewees for confirmation and correction (if necessary) to ensure that all points made in the discussion were appropriately captured.

The finalized notes from the full set of interviews were reviewed by three researchers (M.G., K.S., and P.S.) who, working independently, summarized the answers in a tabular form, proposed categorizations of countries based on their consideration of wealth effects, and grouped common barriers to the inclusion of wealth effects. In particular, based on answers to two key questions (Are wealth effects mentioned in HTA guidelines/methods guide? Are they considered by your HTA body in practice?), we developed a categorization of countries designed to summarize the impact of wealth effects on their decision-making processes. This categorization is presented in the next section.

Results from those analyses were then discussed and validated, and key themes were agreed, in a group discussion involving all four researchers.

INTERVIEW RESULTS

We interviewed thirteen individuals from eight countries: seven academic experts and six individuals working (either currently or formerly) for HTA agencies or the Ministries of Health; two individuals from each country were interviewed, with the exception of France, Italy, and South Korea. When the experts stated they had a direct experience or extensive knowledge of the processes of the HTA agencies and/or the Ministries of Health in their countries, we asked them questions related to those topics (suggesting that the HTA/Health Ministry perspectives were represented).

In two countries (Italy, Poland), a Ministry of Finance perspective was represented as the interviewees were able to answer the questions about the allocation of resources among different ministries. In all countries, the Health Ministry and HTA perspectives were represented.

Do Decision Makers Consider Wealth Effects?

Based on our analysis of the interviewees’ responses (following the approach described in the methods section), we assigned each country to one of four categories: countries that consider wealth effects regularly; countries that consider wealth effects in principle but rarely or never in practice; countries that do not consider wealth effects within HTA; and countries that apparently do not currently consider any economic or cost data when making reimbursement and healthcare budget-setting decisions.

As shown in Table 1 , with the exception of Sweden, no country considers wealth effects on a regular basis. In Australia, Poland, and the United Kingdom, although economic evaluations of individual drug interventions submitted to HTA agencies could include wealth effects as part of a secondary analysis, in practice this rarely happens. In Germany, Italy, and Poland there is no scope for including anything other than the direct costs to the healthcare sector and benefits of a new drug. In France, the HTA agency did not consider economic or cost data at the time of our analysis.

At the Finance Ministry level, our two interviewees (from Poland and Italy) emphasized that there is reluctance to consider wider effects of health interventions in their decisions about allocating resources across sectors. Two other interviewees (from the United Kingdom and Australia) referred to national policy reports emphasizing the importance of wealth effects ( 25 ; 26 ) but noted that these have not resulted in any specific policy changes to date.

Key Barriers for the Inclusion of Wealth Effects

Our interviews revealed several legislative, evidence, and policy barriers to incorporating wealth effects into decision making. We have grouped those into the following themes: (i) System fragmentation, including a persistent culture of silo budgets whereby interlinks between governmental departments’ expenditures are not considered regularly if at all and views that the healthcare system should concentrate on health; (ii) Methodological and data generation issues, such as difficulties in demonstrating with reliable data the impact of a specific treatment on productivity; (iii) Practical issues due to added complexity if those effects are included in decision making; (iv) Equity issues as the inclusion of productivity effects can favor interventions for working-age individuals; (v) Weakness of evidence on the relationship between health and economic growth at the macro level which is limited in relation to high-income countries.

System Fragmentation

The general view among decision makers is that the primary and often sole objective of health care is to improve citizens’ health. Thus healthcare budgets tend to be separate from budgets for other sectors even when they are closely related, such as social care. Any spill-overs that occur across sectors are not captured, for example, where spending on a healthcare intervention leads to lower social care costs that are paid out of a separate budget.

In Australia, Italy, and Poland we found that there are also silo budgets within the heathcare sector. In Australia for example, hospital and primary care are financed separately with no scope for transferring any cost savings between the different parts of the healthcare system.

In South Korea, the Government created a separate budget to cover the cost of care for dementia. However, this budget covers community care but not drug costs, which are funded by means of the health budget. Any savings that may result from a new dementia drug that delays the need for community care would, therefore, not be considered in a drug benefit assessment as they would accrue outside the healthcare sector.

In Sweden, even though the HTA body adopts a societal perspective when making reimbursement recommendations on new medicines (i.e., all relevant costs and benefits associated with a treatment and illness are considered), individual County Councils can restrict use of HTA-approved medicines to meet their own budget targets (the key criterion for their decisions is budget impact) ( 8 ).

A few examples of integrated decision making, where nonhealth programs recognize health benefits, were identified (for example, local authority-funded cycle lanes in the United Kingdom). However, our interviewees could not identify any cases where nonhealth benefits of medicine-based interventions were taken into account when allocating resources to the healthcare sector or more specifically to the budget for pharmaceuticals.

Methodological and Data Generation Issues

When incorporating wealth effects in economic evaluation, there are methodological issues around measuring, and providing evidence of, productivity effects. First, there is no methodology to disaggregate productivity gains and improvements in quality of life measured by the quality-adjusted life-years (QALY). Are changes in the individuals’ ability to earn income reflected in the QALY? If they are, there is a potential for double counting those effects.

Second, even when productivity effects are included in the cost-effectiveness estimation of drug interventions (as indirect costs), HTA bodies require evidence showing productivity effects which are directly attributable to the intervention, which is rarely available. For example, what is the proportion of patients that return to work due to the treatment?

In addition, it was noted that short-term absences from work do not necessarily lead to significant losses for the firm employing the patient as the returning employee might catch up on her/his work and be more productive.

Those concerns were highlighted by interviewees from Australia and the United Kingdom, where the HTA process rely on cost-effectiveness evidence. In Sweden, where wealth effects are considered on a regular basis, an interviewee raised concerns about the poor quality of the studies showing productivity benefits underpinning recent submissions to the HTA body. The reason identified was that other HTA bodies such as NICE do not ask for this evidence, hence it is not a priority for companies to collect it. Overall, it emerged that, if HTA bodies were to consider productivity effects and other wealth effects of health interventions, including savings falling to other public sectors, then robust data showing those effects would be demanded.

The interviewees from Poland and South Korea discussed the issue of transferability of the data on indirect effects across countries, as evidence collected in the United Kingdom or Sweden, for example, may not be applicable to them. Therefore, the lack of country-specific data was identified as a barrier to the incorporation of indirect costs in their HTA decisions.

Practical Issues

Some interviewees were skeptical of the impact that wealth effects, particularly productivity gains, can have on final decisions. As one interviewee stated, indirect costs are unlikely to be “the factor that tips the scale in favor of a treatment or not.”

Furthermore, adopting a wider perspective in economic evaluations would result in more work for HTA agencies and for the manufacturers collecting the evidence. Many of our interviewees questioned whether the inclusion of these wealth effects was worth the additional cost and effort.

In some countries, there are legislative barriers to taking wealth effects into consideration when evaluating health interventions. For example, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in the United Kingdom has until recently been required to adopt a narrow, healthcare sector perspective as specified in the legislation that defined its remit. The new legislation. Public health is already an exception, partly because many of the actions recommended in public health guidance relate to actors outside the health sector. This is reflected in NICE's public health activities where the Institute is more open to reflecting costs and benefits to other sectors. Similarly, in Poland the objective of the healthcare system is defined by law to be to improve the health of the Polish population with no mention of other nonhealth gains. Finally, German decision makers are guided by the statutory Social Code Book regulations, according to which drug benefit assessments should be based on patient relevant benefits identified using clinical endpoints.

Equity Issues

Including indirect effects in the assessment of health interventions can have distributive effects between different social groups. For example, including productivity effects will favor treatments aimed at working age individuals over those who are unable to work because of permanent disabilities, older/retired individuals (who tend to consume more resources than they produce, although they may have been net producers in the past), and children (who may eventually become net producers, but effects accruing over a life time are difficult to estimate). Importantly, this could result in situations where treatments which extend the lives of the older patients for a certain period of time will be found to be less cost-effective than treatments that extend the lives of working age patients for the same amount of time.

Interviewees from Australia and the United Kingdom had particularly strong concerns around the fact that including productivity effects of health interventions conflicted with the principles of equity and nondiscrimination that their health systems were founded upon. Some of the disadvantaged groups are already among the worst-off in society, so any reprioritization of resources away from them could be deemed to be inequitable.

This is in contrast with the approach in Sweden, which is the only country considering wealth effects on a regular basis, despite the fact that it is not an insurance-based system where, arguably, interventions increasing people's ability to work would be favored by employers contributing to insurance funds.

Weakness of Evidence on Health Impact on Economic Growth

We asked all interviewees whether the Suhrcke and Urban ( 18 ) study, which provides evidence on the impact of improved health outcomes in CVD on macroeconomic growth, had had any resonance in their country. Almost all interviewees said that the study, which was commissioned by the European Commission ( 4 ), has not had any impact on their national policy.