Official websites use .gov

A .gov website belongs to an official government organization in the United States.

Secure .gov websites use HTTPS

A lock ( ) or https:// means you've safely connected to the .gov website. Share sensitive information only on official, secure websites.

CDC provides national leadership for HIV prevention research, including the development and evaluation of HIV biomedical and behavioral interventions to prevent HIV transmission and reduce HIV disease progression in the United States and internationally. CDC’s research efforts also include identifying those scientifically proven, cost-effective, and scalable interventions and prevention strategies to be implemented as part of a high-impact prevention approach for maximal impact on the HIV epidemic.

The AIDS epidemic, although first recognized only 20 years ago, has had a profound impact in communities throughout the United States.

The Serostatus Approach to Fighting the HIV Epidemic: Prevention Strategies for Infected Individuals R. S. Janssen, D. R. Holtgrave, and K. M. De Cock led the writing of this commentary. R. O. Valdiserri, M. Shepherd, and H. D. Gayle contributed ideas and helped with writing and reviewing the manuscript.

CDC has provided funding to HIV partners to help implement programs that will help curb the increase of HIV infections. These programs facilitated with our partners and grantees are critical in the goal of eliminating HIV infection in the United States.

CDC has researched several HIV prevention interventions that have proven effective in helping to prevent HIV infection in certain populations and communities.

CDC has worked with key cities to create effective policies and programs to curb the tide of HIV infections in those cities. These cities have higher rates of HIV due to a number of factors therefore making them key locations for studies.

The Medical Monitoring Project (MMP) is a surveillance system designed to learn more about the experiences and needs of people who are living with HIV. It is supported by several government agencies and conducted by state and local health departments along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Assessment of 2010 CDC-funded Health Department HIV Testing Spending and Outcomes [PDF – 359 KB]

- HIV Testing Trends in the United States, 2000-2011 [PDF – 1 MB]

- HIV Testing at CDC-Funded Sites, United States, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands, 2010 [PDF – 691 KB]

- HIV Prevention Funding Allocations at CDC-Funded State and Local Health Departments, 2010 [PDF – 792 KB]

Cost-effectiveness of HIV Prevention

- The cost-effectiveness of HIV prevention efforts has long been a criterion in setting program priorities. The basic principle is straightforward: choose those options that provide the greatest outcome for the least cost.

- The fact sheet Projecting Possible Future Courses of the HIV Epidemic in the United States compares the cost-effectiveness of three different prevention investment scenarios.

The HIV/AIDS Prevention Research Synthesis (PRS) Project identifies evidence-based HIV behavioral interventions (EBIs) listed in the Compendium of Evidence-Based HIV Behavioral Interventions to help HIV prevention planners and providers in the United States choose the interventions most appropriate for their communities.

- On January 1, 2012, CDC began a new 5-year HIV prevention funding cycle with health departments, awarding $339 million annually.

- The STD/HIV National Network of Prevention Training Centers provides training for health departments and CBOs on the HIV prevention interventions.

- HIV Nexus: Resources for Clinicians

- Ending the HIV Epidemic (EHE)

- Public Health Partners

- Let’s Stop HIV Together

- @StopHIVTogether

- Get Email Updates

- Send Feedback

- Fact sheets

Facts in pictures

- Publications

- Questions and answers

- Tools and toolkits

- Endometriosis

- Excessive heat

- Mental disorders

- Polycystic ovary syndrome

- All countries

- Eastern Mediterranean

- South-East Asia

- Western Pacific

- Data by country

- Country presence

- Country strengthening

- Country cooperation strategies

- News releases

- Feature stories

- Press conferences

- Commentaries

- Photo library

- Afghanistan

- Cholera

- Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)

- Greater Horn of Africa

- Israel and occupied Palestinian territory

- Disease Outbreak News

- Situation reports

- Weekly Epidemiological Record

- Surveillance

- Health emergency appeal

- International Health Regulations

- Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee

- Classifications

- Data collections

- Global Health Observatory

- Global Health Estimates

- Mortality Database

- Sustainable Development Goals

- Health Inequality Monitor

- Global Progress

- World Health Statistics

- Partnerships

- Committees and advisory groups

- Collaborating centres

- Technical teams

- Organizational structure

- Initiatives

- General Programme of Work

- WHO Academy

- Investment in WHO

- WHO Foundation

- External audit

- Financial statements

- Internal audit and investigations

- Programme Budget

- Results reports

- Governing bodies

- World Health Assembly

- Executive Board

- Member States Portal

- Fact sheets /

HIV and AIDS

- HIV remains a major global public health issue, having claimed an estimated 42.3 million lives to date. Transmission is ongoing in all countries globally.

- There were an estimated 39.9 million people living with HIV at the end of 2023, 65% of whom are in the WHO African Region.

- In 2023, an estimated 630 000 people died from HIV-related causes and an estimated 1.3 million people acquired HIV.

- There is no cure for HIV infection. However, with access to effective HIV prevention, diagnosis, treatment and care, including for opportunistic infections, HIV infection has become a manageable chronic health condition, enabling people living with HIV to lead long and healthy lives.

- WHO, the Global Fund and UNAIDS all have global HIV strategies that are aligned with the SDG target 3.3 of ending the HIV epidemic by 2030.

- By 2025, 95% of all people living with HIV should have a diagnosis, 95% of whom should be taking lifesaving antiretroviral treatment, and 95% of people living with HIV on treatment should achieve a suppressed viral load for the benefit of the person’s health and for reducing onward HIV transmission. In 2023, these percentages were 86%, 89%, and 93% respectively.

- In 2023, of all people living with HIV, 86% knew their status, 77% were receiving antiretroviral therapy and 72% had suppressed viral loads.

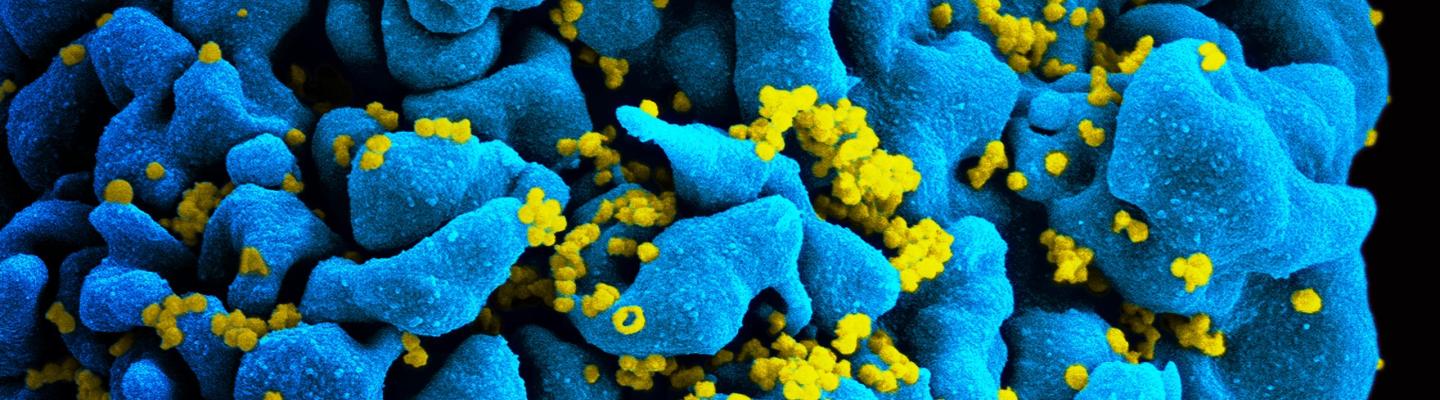

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) occurs at the most advanced stage of infection.

HIV targets the body’s white blood cells, weakening the immune system. This makes it easier to get sick with diseases like tuberculosis, infections and some cancers.

HIV is spread from the body fluids of an infected person, including blood, breast milk, semen and vaginal fluids. It is not spread by kisses, hugs or sharing food. It can also spread from a mother to her baby.

HIV can be prevented and treated with antiretroviral therapy (ART). Untreated HIV can progress to AIDS, often after many years.

WHO now defines Advanced HIV Disease (AHD) as CD4 cell count less than 200 cells/mm3 or WHO stage 3 or 4 in adults and adolescents. All children younger than 5 years of age living with HIV are considered to have advanced HIV disease.

Signs and symptoms

The symptoms of HIV vary depending on the stage of infection.

HIV spreads more easily in the first few months after a person is infected, but many are unaware of their status until the later stages. In the first few weeks after being infected people may not experience symptoms. Others may have an influenza-like illness including:

- sore throat.

The infection progressively weakens the immune system. This can cause other signs and symptoms:

- swollen lymph nodes

- weight loss

Without treatment, people living with HIV infection can also develop severe illnesses:

- tuberculosis (TB)

- cryptococcal meningitis

- severe bacterial infections

- cancers such as lymphomas and Kaposi's sarcoma.

HIV causes other infections to get worse, such as hepatitis C, hepatitis B and mpox.

Transmission

HIV can be transmitted via the exchange of body fluids from people living with HIV, including blood, breast milk, semen, and vaginal secretions. HIV can also be transmitted to a child during pregnancy and delivery. People cannot become infected with HIV through ordinary day-to-day contact such as kissing, hugging, shaking hands, or sharing personal objects, food or water.

People living with HIV who are taking ART and have an undetectable viral load will not transmit HIV to their sexual partners. Early access to ART and support to remain on treatment is therefore critical not only to improve the health of people living with HIV but also to prevent HIV transmission.

Risk factors

Behaviours and conditions that put people at greater risk of contracting HIV include:

- having anal or vaginal sex without a condom;

- having another sexually transmitted infection (STI) such as syphilis, herpes, chlamydia, gonorrhoea and bacterial vaginosis;

- harmful use of alcohol or drugs in the context of sexual behaviour;

- sharing contaminated needles, syringes and other injecting equipment, or drug solutions when injecting drugs;

- receiving unsafe injections, blood transfusions, or tissue transplantation; and

- medical procedures that involve unsterile cutting or piercing; or accidental needle stick injuries, including among health workers.

HIV can be diagnosed through rapid diagnostic tests that provide same-day results. This greatly facilitates early diagnosis and linkage with treatment and prevention. People can also use HIV self-tests to test themselves. However, no single test can provide a full HIV positive diagnosis; confirmatory testing is required, conducted by a qualified and trained health worker or community worker. HIV infection can be detected with great accuracy using WHO prequalified tests within a nationally approved testing strategy and algorithm.

Most widely used HIV diagnostic tests detect antibodies produced by a person as part of their immune response to fight HIV. In most cases, people develop antibodies to HIV within 28 days of infection. During this time, people are in the so-called “window period” when they have low levels of antibodies which cannot be detected by many rapid tests, but they may still transmit HIV to others. People who have had a recent high-risk exposure and test negative can have a further test after 28 days.

Following a positive diagnosis, people should be retested before they are enrolled in treatment and care to rule out any potential testing or reporting error. While testing for adolescents and adults has been made simple and efficient, this is not the case for babies born to HIV-positive mothers. For children less than 18 months of age, rapid antibody testing is not sufficient to identify HIV infection – virological testing must be provided as early as birth or at 6 weeks of age. New technologies are now available to perform this test at the point of care and enable same-day results, which will accelerate appropriate linkage with treatment and care.

HIV is a preventable disease. Reduce the risk of HIV infection by:

- using a male or female condom during sex

- being tested for HIV and sexually transmitted infections

- having a voluntary medical male circumcision

- using harm reduction services for people who inject and use drugs.

Doctors may suggest medicines and medical devices to help prevent HIV infection, including:

- antiretroviral drugs (ARVs), including oral Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and long acting products

- dapivirine vaginal rings

- injectable long acting cabotegravir.

ARVs can also be used to prevent mothers from passing HIV to their children.

People taking antiretroviral therapy (ART) and who have no evidence of virus in the blood will not pass HIV to their sexual partners. Access to testing and ART is an important part of preventing HIV.

Antiretroviral drugs given to people without HIV can prevent infection

When given before possible exposures to HIV it is called pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and when given after an exposure it is called post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). People can use PrEP or PEP when the risk of contracting HIV is high; people should seek advice from a clinician when thinking about using PrEP or PEP.

There is no cure for HIV infection. It is treated with antiretroviral drugs, which stop the virus from replicating in the body.

Current antiretroviral therapy (ART) does not cure HIV infection but allows a person’s immune system to get stronger. This helps them to fight other infections.

Currently, ART must be taken every day for the rest of a person’s life.

ART lowers the amount of the virus in a person’s body. This stops symptoms and allows people to live full and healthy lives. People living with HIV who are taking ART and who have no evidence of virus in the blood will not spread the virus to their sexual partners.

Pregnant women with HIV should have access to, and take, ART as soon as possible. This protects the health of the mother and will help prevent HIV transmission to the fetus before birth, or through breast milk.

Advanced HIV disease remains a persistent problem in the HIV response. WHO is supporting countries to implement the advanced HIV disease package of care to reduce illness and death. Newer HIV medicines and short course treatments for opportunistic infections like cryptococcal meningitis are being developed that may change the way people take ART and prevention medicines, including access to injectable formulations, in the future.

More information on HIV treatments

WHO response

Global health sector strategies on HIV, viral hepatitis, and sexually transmitted infections for the period 2022–2030 ( GHSSs ) guide strategic responses to achieve the goals of ending AIDS, viral hepatitis B and C, and sexually transmitted infections by 2030.

WHO’s Global HIV, Hepatitis and STIs Programmes recommend shared and disease-specific country actions supported by WHO and partners. They consider the epidemiological, technological, and contextual shifts of previous years, foster learning, and create opportunities to leverage innovation and new knowledge.

WHO’s programmes call to reach the people most affected and most at risk for each disease, and to address inequities. Under a framework of universal health coverage and primary health care, WHO’s programmes contribute to achieving the goals of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

- Global HIV, Hepatitis and STIs Programmes

- Global Health Sector Strategies on, respectively, HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmitted infections for the period 2022–2030 (GHSS)

- GHSS report on progress and gaps 2024

- HIV country profiles

- HIV statistics, globally and by WHO region, 2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

A Review of Recent HIV Prevention Interventions and Future Considerations for Nursing Science

Author Contributions

As our knowledge of HIV evolved over the decades, so have the approaches taken to prevent its transmission. Public health scholars and practitioners have engaged in four key strategies for HIV prevention: behavioral-, technological-, biomedical-, and structural/community-level interventions. We reviewed recent literature in these areas to provide an overview of current advances in HIV prevention science in the United States. Building on classical approaches, current HIV prevention models leverage intimate partners, families, social media, emerging technologies, medication therapy, and policy modifications to effect change. Although much progress has been made, additional work is needed to achieve the national goal of ending the HIV epidemic by 2030. Nurses are in a prime position to advance HIV prevention science in partnership with transdisciplinary experts from other fields (e.g., psychology, informatics, and social work). Future considerations for nursing science include leveraging transdisciplinary collaborations and consider social and structural challenges for individual-level interventions.

Approximately 1.2 million people in the United States are currently living with HIV, and an estimated 14% are infected, yet unaware of their status ( Office of Infectious Disease and HIV/AIDS Policy, 2020 ). HIV and AIDS continue to have a disproportionate impact on certain populations, including youth—gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men (MSM)—racial and ethnic minorities, people who inject drugs, and residents of highly affected geographic regions such as the Southeastern United States ( Aral et al., 2020 ; Hill et al., 2018 ; Lanier & Sutton, 2013 ). Ending the HIV epidemic requires increasing engagement along the HIV prevention and care continua ( Kay et al., 2016 ; McNairy & El-Sadr, 2014 ). Early and repeat HIV testing are recommended strategies for early entry into HIV care and improved HIV-related outcomes ( DiNenno et al., 2017 ). Late and infrequent HIV testing may result in receiving an initial HIV diagnosis late in the disease trajectory, and individuals unaware they are living with HIV may be more likely to transmit HIV to others. It is essential for people living with HIV (PLWH) to receive a timely diagnosis so that they can begin combination antiretroviral therapy with the goal of achieving an undetectable viral load, a key HIV prevention strategy ( Cohen et al., 2016 ). To improve linkage and retention along the prevention and care continua, researchers have developed HIV prevention interventions in four key areas: behavioral-, technological-, biomedical-, and structural/community-level interventions.

Behavioral interventions are approaches that promote protective or risk-reduction behavior in individuals and social groups via informational, motivational, skill-building, and community-normative strategies ( Coates et al., 2008 ). HIV-specific examples include, but are not limited to, interventions promoting abstinence, condom use, sex communication, condom negotiation, HIV testing, reduction in number of sexual partners, stigma reduction, and use of clean needles among people who inject drugs. Behavioral interventions target various HIV risk behavior mediators and moderators, including symptoms of mental illness and emotion regulation ( Brawner et al., 2019 ), attitudes, beliefs, subjective norms, intentions ( Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975 ), and self-efficacy ( Bandura, 2001 ). The effectiveness of behavior-change interventions in reducing risk for HIV during the early stages of the HIV pandemic demonstrated the importance and utility of this approach ( Bekker et al., 2012 ). Classic approaches to behavioral interventions established in the early 1990s and 2000s paved the way for future research to build on, replicate, adapt, tailor, and disseminate a multitude of programs to meet the needs of various populations, such as women ( Jemmott et al., 2007 ; Wingood et al., 2004 ), MSM ( Crosby et al., 2009 ), and adolescents ( DiClemente et al., 2009 ; Jemmott et al, 1992 , 1998 , 1999 , 2010 ; Villarruel et al., 2007 ). To extend the reach of behavioral interventions, in recent years, researchers have begun leveraging technologies to promote protective and risk reduction behaviors.

The rapid expansion of the internet, mobile, and social computing technologies (e.g., text messaging, e-mail, chat, mobile phones, social media, video games, and geospatial networking applications) has provided new strategies for engaging populations who may be harder to reach through traditional venue-based HIV prevention interventions. Electronic health (eHealth) and mobile health (mHealth) have become especially popular for the delivery of technology-enabled HIV prevention interventions among populations reporting high technology ownership and use ( Barry et al., 2018 ; Conserve et al., 2016 ; Duarte et al., 2019 ; Henny et al., 2018; Hightow-Weidman & Bauermeister, 2020 ; Jongbloed et al., 2015 ; Maloney et al., 2020 ; Nadarzynski et al., 2017 ). In recent years, gamification, serious games, and virtual reality have been used in HIV prevention interventions to deliver highly engaged content and bolster interactions/behaviors in and outside of planned interventions ( Enah et al., 2013 ; Hightow-Weidman et al., 2017 , 2018 ; Liran et al., 2019 ; Muessig et al., 2015 , 2018 ). The potential role that technologies can play in increasing the scale of HIV prevention interventions, including those that aim to increase the adoption of biomedical HIV prevention methods, add to the appeal of these strategies ( Hightow-Weidman et al., 2020 ; Horvath et al., 2020 ; Maloney et al., 2020 ; Marcus et al., 2019 ; Muessig et al., 2015 ; Ramos et al., 2019 ; Threats & Bond 2021 ).

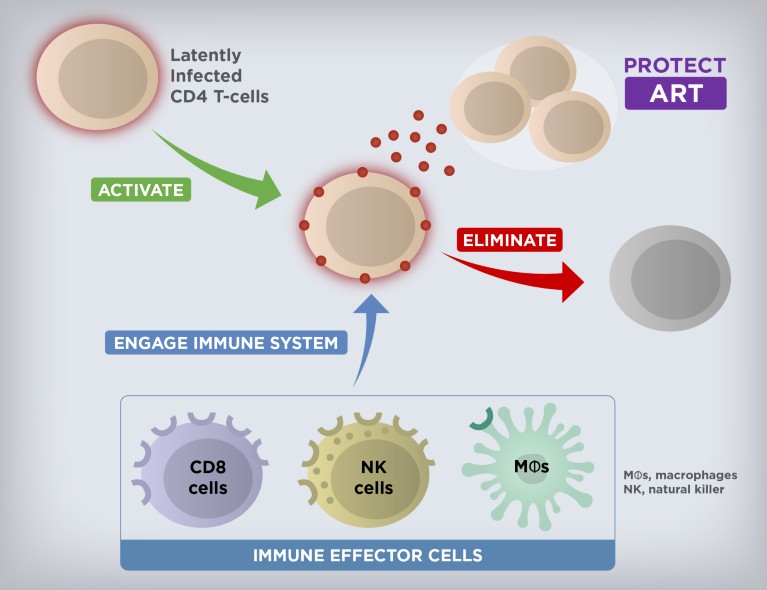

Efficacious biomedical advancements in HIV prevention, such as treatment as prevention (TasP) and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), remain underutilized because of structural barriers and social determinants of health ( Cahill et al., 2017 ; Jaiswal et al., 2018 ; Kuhns et al., 2019 ). TasP, postexposure prophylaxis (PEP), PrEP, and pharmacologic therapy for substance abuse treatment have proven to be effective for reducing the transmission of HIV and minimizing the risk of new HIV infection ( Coffin et al., 2015 ; El-Bassel & Strathdee, 2015 ; Hosek, Green, et al., 2013 ; Page et al., 2015 ; Springer et al., 2018 ). Although biomedical prevention methods such as PEP and TasP are highly effective, we explicitly focus on PrEP because of its status as the premiere user-controlled HIV prevention medication regimen and its ability to be taken without disclosure to sexual partner(s).

In addition to behavioral, technological, and biomedical strategies that help to mitigate risk at the individual-, structural-, and community-levels, additional intervention strategies are needed to address broader social and structural factors that contribute to inequitable geobehavioral vulnerability to HIV ( Brawner, 2014 ). Such HIV prevention interventions target contextual factors (e.g., social, political–economic, policy–legal, and cultural factors) that influence transmission of and infection with HIV ( Blankenship et al., 2015 ), with an effect that diffuses out to members of key populations. Where individual-level interventions are designed to change individual beliefs, norms, and behaviors, community-level interventions aim to change the social environment (e.g., community-level norms and collective self-efficacy) and behaviors of entire populations ( Underwood et al., 2014 ). Structural- and community-level interventions are crucial to a comprehensive HIV prevention plan because they are designed to target macrolevel contextual factors (e.g., concentrated disadvantage in neighborhoods, syringe exchange policies, community-level stigma, and limited PrEP accessibility) that shape individual risk or hamper adoption of risk reduction strategies and therapeutics ( Allen et al., 2016 ; Colarossi et al., 2016 ; Gamble et al., 2017 ; Hoth et al., 2019 ; Kerr et al., 2015 ). Researchers in this space have successfully partnered with churches to decrease stigma and increase HIV testing ( Berkley-Patton et al., 2016 ; Payne-Foster et al., 2018 ), expand access to screening and prevention resources and change provider behavior ( Bagchi, 2020 ; Bernstein et al., 2017 ; Wood et al., 2018 ), and increase HIV testing in correctional facilities ( Belenko et al., 2017 ).

In this review of the literature, we explore the evolution of HIV prevention science over the past 5 years, presenting an overview of recent advances in the United States. We focused on four intervention categories—behavioral-, technological-, biomedical- (PrEP), and structural-/community-level—given the advancement of HIV prevention approaches over time. The findings highlight areas where nurses and others can advance the science of strategies to reach the national goal of ending the HIV epidemic by 2030 ( Fauci et al., 2019 ).

In our review of recent randomized controlled trials testing the efficacy of condom use and/or abstinence interventions, most targeted vulnerable populations included MSM ( Arnold et al., 2019 ; Crosby et al., 2018 ; Rhodes et al., 2017 ), adolescents ( Donenberg et al., 2018 ; Houck et al., 2016 ; Peskin et al., 2019 ), and adolescent/caregiver dyads ( Hadley et al., 2016 ; Jemmott et al., 2019 , 2020 ). Other interventions targeted incarcerated women ( Fogel et al., 2015 ) and illicit drug users ( Tobin et al., 2017 ). Many interventions were delivered in a health care or school setting, where multiple 60- to 120-min group sessions were presented. However, some interventions used a variation of frequencies and durations, such as a single 60-min one-to-one session ( Crosby et al., 2018 ) or multiple 4-hour group sessions ( Rhodes et al., 2017 ). One intervention allowed participants to attend one or two independent learning sessions, totaling 3 hours ( Hadley et al., 2016 ). About half of the reviewed studies tested the efficacy of new interventions, whereas the other half adapted previously established behavioral interventions. Crosby et al. (2018) , Fogel et al. (2015) , and Hadley et al. (2016) each adapted a different sexual health intervention. Conversely, Donenberg et al. (2018) adapted an intervention from a combination of three evidence-based programs. Instead of adapting an intervention, Peskin et al. (2019) replicated an evidence-based intervention. All interventions, except one ( Rhodes et al., 2017 ), were delivered in English.

Although several behavioral interventions led to significant increases in condom use and/or abstinence, compared with control conditions, others found no indication of intervention efficacy. For instance, Hadley et al. (2016) reported no significant group by time differences for condom use at the 3-month follow-up. These findings may be the result of delayed effects, as seen in the Fogel et al. (2015) intervention where significant group differences in condom use occurred at the 6-month follow-up, but not at the 3-month follow-up. Conversely, neither Arnold et al. (2019) nor Donenberg et al. (2018) found significant group by time differences in condom use at or beyond the 6-month follow-up, and Peskin et al. (2019) did not find differences in sexual initiation at the 24-month follow-up. These findings show that longer follow-up periods do not always have better results compared with short (i.e., 3 months) follow-up periods.

Among efficacious behavioral interventions, there was a single-session skill-building condom buffet activity ( Crosby et al., 2018 ) and multisession programs focusing on the costs and benefits of behavior change ( Fogel et al., 2015 ), emotion regulation ( Houck et al., 2016 ), cultural values ( Rhodes et al., 2017 ), environmental stressors ( Tobin et al., 2017 ), mother–son communication ( Jemmott et al., 2019 ), and scripture- and nonscripture-based abstinence ( Jemmott et al., 2020 ). Each was rooted in theoretical foundations, including those of the Theory of Planned Behavior, Social Cognitive Theory, cognitive behavioral techniques, and the AIDS Risk Reduction Model ( Azjen, 1991 ; Bandura, 1991 ; Catania et al., 1990 ). The Jemmott et al. (2019) intervention was unique in that intervention outcomes were assessed for both mothers and their sons, although the intervention was only implemented among the mothers. All other studies reported the findings of interventions that were implemented among the same participants for which outcomes were assessed.

We unexpectedly identified a nearly equal number of efficacious and nonefficacious behavioral interventions. Many studies reported increases in constructs leading to behavior change, such as self-efficacy, intentions, and attitudes, but did not find changes in actual condom use or abstinence behaviors ( Arnold et al., 2019 ; Donenberg et al., 2018 ; Hadley et al., 2016 ; Peskin et al., 2019 ). Interventions that were effective in increasing condom use and/or abstinence varied in characteristics, showing that single-session and multisession, short- and long-duration, newly created and adapted interventions can be efficacious.

Of the four interventions adapted from existing evidence-based programs, two were efficacious ( Crosby et al., 2018 ; Fogel et al., 2015 ). These interventions adapted the Focus on the Future ( Crosby et al., 2009 ) and Sexual Awareness for Everyone ( Shain et al., 1999 ) interventions. Adaptation has been long supported as an effective way to bring evidence-based interventions to new target populations and is often preferred over the creation of new interventions ( McKleroy et al., 2006 ; Solomon et al., 2006 ). However, with only half of the adapted interventions showing increased condom use among participants, it is critical that interventionists pay close attention to fidelity, proper use of theoretical foundations, and inclusion of core components during intervention adaptation and replication to maintain efficacy of the original intervention.

In accordance with previous research, the identified studies indicate the need to move away from interventions addressing a single behavior to those focusing on a combination of behavioral, biomedical, and structural approaches ( Belgrave & Abrams, 2016 ; Kurth et al., 2011 ) and those using popular technologically advanced delivery methods.

Technological Interventions

Most of the technological intervention literature we reviewed reported on studies that were at lower levels of the hierarchy of evidence ( Melnyk & Fineout-Overholt, 2011 ). Specifically, there was an imbalance in studies favoring more formative qualitative work or pilot studies compared with fewer studies reporting on randomized control trials or meta-analysis. Many studies reporting on randomized control trials also did not report on HIV-related outcomes but focused on content, protocols, or feasibility aspects of the randomized control trials. As a result, most studies reviewed were cross-sectional descriptive studies or qualitative descriptive studies using data collection strategies such as focus groups, interviews expert panels, surveys, and mixed methods ( Rodríguez Vargas et al., 2019 ; Velloza et al., 2019 ). Many of these formative studies ( Bauermeister et al., 2019 ; Cordova et al., 2018 ; Do et al., 2018 ; Enah et al., 2019 ; Erguera et al., 2019 ; Maloney et al., 2020 ; Sullivan et al., 2017 ) focused on the appeal, usability, acceptability, and feasibility of using mHealth and eHealth HIV prevention intervention across the continuum from primary prevention to disease management.

Reviewed studies show that technological interventions in HIV prevention have been studied in various target populations. These target populations include youth and young adults ( Cordova et al., 2018 ; Do et al., 2018 ; Erguera et al., 2019 ), MSM ( Alarcón Gutiérrez et al., 2018 ; Fan et al., 2020 ; Holloway et al., 2017 ), incarcerated women ( Kuo et al., 2019 ), couples ( Mitchell, 2015 ; Velloza et al., 2019 ), adults in drug recovery ( Liang et al., 2018 ), and PLWH ( Bauermeister et al., 2018 ; Schnall et al., 2019 ). These interventions vary in the technological innovations used, duration, language, format of delivery, and target outcomes.

The technology-enabled intervention studies reviewed used varying strategies to target different areas along the continuum of HIV prevention and care. In HIV testing, the focus was on synching home test results with phone counseling support ( Wray et al., 2017 ) and ordering, scheduling, and reminders associated with testing kits (e.g., Sullivan et al., 2017 ). Some studies focused on education using interactive web-based games and social media platforms ( Bauermeister et al., 2019 ; Bond & Ramos, 2019 ; Cordova et al., 2018 ; Gabarron & Wynn, 2016 ), behavioral change interventions ( Danielsonetal.,2014 ),or linkage to care and care support ( Bauermeister et al., 2018 ) targeting people who are living without HIV. Other studies focused on similar points along the care and prevention continuum targeting PLWH ( Maloney et al., 2020 ). Studies reviewed also focused on a wide range of interventions such as provision of information, self-assessments, adherence reminders, delivery of prevention information, referrals, and service from providers ( Boni et al., 2018 ; De Boni et al., 2018 ; Maloney et al., 2020 ). A number of studies included text messaging for health education, reminders, and assessments ( Dietrich et al., 2018 ; Njuguna et al., 2016 ; Ware et al., 2016 ), whereas others focused on primary behavioral preventions such as drug use ( Cordova et al., 2018 ) and engagement in care and disease management for PLWH ( Fan et al., 2020 ; Jongbloed et al., 2015 ). Reviewed studies targeting both persons living with and without HIV also used various technological-based approaches, such as interactive web-based content ( Bauermeister et al., 2019 ), smartphone geolocators near gay venues reinforcing safer sex practices ( Besoain et al., 2015 ), immersive adventure games ( Enah et al., 2019 ), and use of eye tracking technologies to monitor use ( Cho et al., 2018 , 2019 ).

Eight studies reviewed were narrative, scoping, and systematic reviews of the use and efficacy of technology-based interventions ( Bailey et al., 2015 ; Duarte et al., 2019 ; Gabarron & Wynn, 2016 ; Henny et al., 2018; Jongbloed et al., 2015 ; Maloney et al., 2020 ; Nadarzynski et al., 2017 ; Niakan et al., 2017 ). Scoping reviews of earlier digital STI prevention interventions revealed moderate effects on sexual health knowledge, small effect of behavior change, and no significant changes in biological outcomes ( Bailey et al., 2015 ; Gabarron & Wynn, 2016 ). These reviews examined studies that incorporated interventions using various designs, content, formats, target populations, and quality of content. Taken together, these reviews suggest that more research is needed to identify or develop components that can promote changes in biological outcomes. The most recent systematic review ( Maloney et al., 2020 ) found a wealth of published literature on technology-based interventions. However, findings from this systematic review suggest that most of the studies focus on educational and behavior change interventions, whereas relatively few focused on linkage to and retention in HIV prevention and care and adherence to HIV medicines, especially PrEP.

The drug combination of tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and emtricitabine (FTC), widely known by its brand name Truvada, used as oral PrEP in preventing HIV infections for MSM in the United States, is a well-documented, effective prevention strategy ( Grant et al., 2010 ; Mayer et al., 2020 ). However, many communities impacted by HIV are underrepresented in research trials in the United States, including transgender populations, cisgender women, and people who inject drugs. Most of the research in these groups has occurred internationally and has not had as strong an impact on HIV incidence as that of the MSM ( Baeten et al., 2012 ; Kibengo et al., 2013 ; MacLachlan & Cowie, 2015 ; Marrazzo et al., 2015 ; Martin et al., 2017 ; Mutua et al., 2012 ; Peterson et al., 2007 ; Thigpen et al., 2012 ; Van Damme et al., 2012 ).

Despite Black MSM bearing a disproportionate burden of HIV infection in comparison to MSM of other ethnicities, they are underrepresented in PrEP studies ( Hess et al., 2017 ). Most PrEP clinical trials, open-label studies, and observational studies included less than 10% Black MSM. ( Grant et al., 2010 ; Mayer et al., 2020 ). The few studies that included higher proportions of Black MSM had small numbers, including three community studies by Chan (49%, n = 109), Project PrEPare-ATN 082 (53%, n = 31), Project PrEPare-ATN 110 (47%, n = 93), and Project PrEPare-ATN 113 (29%, n = 23; Hosek et al., 2017 ; Hosek, Siberry, et al., 2013 ). Moreover, there are study gaps in sex, and the number of studies on high-risk cisgender women and transgender women is significantly smaller compared with MSM ( Kamitani et al., 2019 )

In 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved tenofovir alafenamide/emtricitabine (TAF/FTC), widely known as Descovy, as the first alternative medication for PrEP for MSM and transfeminine communities (FDA, 2019). TAF/FTC was shown to be noninferior to TDF/FTC. The side-effect profiles differ in that TDF/FTC has increases in renal and bone toxicities and TAF/FTC has increases in weight and lipids ( Mayer et al., 2020 ). TAF/FTC was not studied in other communities and did not gain an FDA indication for cisgender women and transmasculine communities. Some studies have found a potential link between the use of estradiol for gender-affirming care and lower tenofovir levels in the blood ( Hiransuthikul et al., 2019 ; Shieh et al., 2019 ; Yager & Anderson, 2020 ).There have been smaller studies to verify this interaction, but reported controlling for confounding variables was difficult. Further research is needed to understand whether there is effect on the efficacy of TDF and how this may impact nondaily dosing strategies.

Currently, daily oral PrEP is the only antiretroviral medication recommended for the prevention of HIV through sexual contact and drug injection use among people without HIV by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC; U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & U.S. Public Health Service, 2018 ). In 2015, Molina et al. (2015) published a placebo-controlled trial of an “On-Demand” or 2-1-1 dosing strategy for MSM and transfeminine communities where 2 TDF/FTC pills would be taken 2 to 24 hr before sex, followed by 1 pill every 24 hr while sex continues, and ending 2 doses after the last sex act. This study found high efficacy and acceptability with an 86% reduction in HIV incidence relative to placebo on an intention to treat basis; no one acquired HIV while using 2-1-1 dosing of this nondaily dosing strategy. Furthermore, additional prospective open-label studies also showed no HIV acquisition among study participants ( Hojilla et al., 2020 ; Siguier et al., 2019 ). Despite the lack of endorsement by the CDC, many local Departments of Public Health support PrEP 2-1-1 as a way to make PrEP more attainable for the MSM community ( Los Angeles County Department of Public Health, 2019 ; New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2019 ; San Francisco Department of Public Health, 2019 ).

Although effective, researchers and primary care providers note the need to simplify current PrEP delivery models. The CDC recommends a follow-up visit every 3 months while on PrEP, which can often be challenging for individuals to attend visits and pay laboratory costs ( U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention & U.S. Public Health Service, 2018 ). A new model of care that leverages mHealth (e.g., mobile and social computing technologies) to increase initiation, retention, and adherence to PrEP, such as electronic PrEP (ePrEP), has been introduced and found to be acceptable and effective among PrEP users ( Siegler et al., 2020 ). PrEPmate is one such multicomponent mHealth intervention that uses short-message service (SMS) and youth-tailored interactive online content to enhance PrEP adherence among at-risk young MSM ( Liu et al., 2019 ). Currently, it is the only PrEP study identified as an Evidence-Based Intervention by the CDC Prevention Research Synthesis project ( CDC, 2020 ). Siegler et al. implemented the PrEP at Home Study among 50 young Black MSM in a rural area. In the study, 42% of participants received PrEP via the ePrEP system, whereas 93% preferred to use ePrEP over standard provider visit and 67% were more likely to remain on PrEP if ePrEP were available ( Siegler et al., 2019 ).

Future biomedical HIV prevention modalities such as long-acting injectable agents have the potential to prevent HIV acquisition without relying on adherence to a daily or 2-1-1 oral dosing regimen. In MSM and transfeminine communities, an injectable form of cabotegravir given intramuscularly every 2 months had an estimated 66% lower incidence of HIV, compared with daily TDF/FTC ( Landovitz, 2020 ). Additional cabotegravir studies in cisgender women are being conducted under HPTN 084 to evaluate safety and efficacy (the LIFE Study; HIV Prevention Trials Network, 2020 ). The dapivirine (DAP) vaginal ring, for use by cis-women as a flexible silicone ring that continuously releases the antiretroviral HIV drug DAP in the vagina as a long-acting option for HIV prevention is another biomedical HIV prevention modality being studied ( Psomas et al., 2017 ). A phase 2a trial of a 25-mg DAP vaginal ring has been shown to be safe and acceptable among U.S. adolescents ages 15–17 ( Psomas et al., 2017 ). The DAP vaginal ring has been approved by the European Medicines Agency for women older than 25 years, and further studies are ongoing for women ages 15–25 years in the United States ( National Institutes of Health, 2020 ).

Although there are clear benefits to the aforementioned intervention strategies, structural- and community-level interventions are distinctly different, given their focus on macrolevel factors that influence risk versus individual beliefs and behaviors. This is imperative because in many highly affected demographics (e.g., Black women and young racial and ethnic minority MSM), broader social and structural factors drive HIV risk more than individual behavior ( Bauermeister et al., 2017 ; Brawner, 2014 ). With this wider focus, changes are seen in factors such as social diffusion of safer sex messages and comfort with being gay ( Eke et al., 2019 ), better viral suppression and continuity in care ( El-Sadr et al., 2017 ; Towe et al., 2019 ; Wohl et al., 2017 ), and increased HIV testing in populations that may not have otherwise been tested ( Belenko et al., 2017 ; Berkley-Patton et al., 2019 ; Frye et al., 2019 ).

Addressing structural barriers can reduce viral load, prevent HIV infection, and increase HIV testing. In homeless populations, researchers used a rapid rehousing intervention to place participants in stable housing faster (3 months earlier than usual service clients), doubling the likelihood of achieving or maintaining viral suppression ( Towe et al., 2019 ), and worked through primary care providers in Veterans Affairs to increase PrEP access ( Gregg et al., 2020 ). Community-level interventions that used financial incentives reduced viral load and decreased self-reported stimulant use among sexual minority men who use methamphetamine ( Carrico et al., 2016 ) and increased viral suppression and continuity in care in HIV-positive patients ( El-Sadr et al., 2017 ). The latter intervention, however, did not demonstrate an effect on increasing linkage to care.

Health care access remains a concern, and novel strategies can be used to get services to those in need. Pharmacies have also been promising locations for HIV prevention work. Persons who inject drugs were more likely to report always using a sterile syringe than not when they were connected to pharmacies that received in-depth harm reduction training and provided additional services (i.e., HIV prevention/medical/social service referrals and syringe disposal containers; Lewis et al., 2015 ). Providing a PEP informational video and direct pharmacy access to PEP also increased PEP knowledge and willingness; however, this did not translate to more PEP requests ( Lewis et al., 2020 ).

In correctional facilities, researchers have used strategies such as referral to care within 5 days after release, medication text reminders, and local change teams with external coaching to maintain viral suppression post-release and increase HIV testing among inmates ( Belenko et al., 2017 ; Wohl et al., 2017 ). High fidelity to the required institutional changes needed to improve HIV services was also noted ( Pankow et al., 2017 ). With the detrimental effects of mass incarceration, including disparate HIV outcomes while incarcerated and post-release, correctional settings are prime targets for future structural intervention work.

Success is tied to meeting people where they are—engaging them through existing programs, organizations, and institutions they are already connected to. Congregation-level interventions have demonstrated success in doubling HIV testing rates and reducing HIV stigma ( Berkley-Patton et al., 2019 ; Derose et al., 2016 ; Payne-Foster et al., 2018 ); however, effects on HIV stigma varied across studies. The studies demonstrating an effect on HIV stigma only achieved this at the individual—not congregation—level ( Payne-Foster et al., 2018 ), and in Latino—but not African American—churches ( Derose et al., 2016 ). Key to these interventions was the inclusion of multilevel activities (e.g., ministry group activities, HIV testing events during services, and pastors delivered sermons on HIV-related topics) and flexibility to accommodate church schedules and levels of comfort with covering different topics. Churches were not the only setting where addressing HIV stigma beyond the individual-level was a challenge. In a community-level intervention on HIV stigma, homophobia, and HIV testing, researchers used workshops, space-based events, and bus shelter ads in a high HIV prevalence area but did not have an effect on HIV stigma or homophobia ( Frye et al., 2019 ). They did, however, increase HIV testing by 350%.

Individuals within key systems and communities can also be pivotal to share HIV-related information and increase access to services. Integration of lay health advisors (“Navegantes”) into existing social networks (i.e., recreational soccer teams) among Hispanic/Latino men led to twice the likelihood of reporting consistent condom use in the past 30 days and HIV testing at the 18-month follow-up ( Rhodes, Leichliter, et al., 2016 ). A year after the intervention ended, 2 years after their training, 84% of the Navegantes (16 of 19) continued to conduct 9 of the 10 primary health promotion activities (e.g., talking about sexual health, describing where to get condoms, and showing segments of the intervention DVD; Sun et al., 2015 ). Furthermore, using a popular opinion leader model targeting alcohol-using social networks, researchers demonstrated a decline in composite sexual risk (e.g., having sex while high or with a partner who is high and exchanging sex for drugs or money) and an increase in HIV knowledge ( Theall et al., 2015 ). An intervention developed for college students and those in the surrounding area integrated HIV testing and education, mental health, and substance abuse services and referrals and noted a preliminary effect on social norms and sexual health messages on campus ( Ali et al., 2017 ).

Culturally situated marketing and other media approaches reach a broader audience to effect change. Successful social marketing campaigns to promote HIV testing should be performed in a way that enhances well-being (rather than fear-based messages), does not represent the target community in stigmatizing ways, and acknowledges barriers to HIV testing (e.g., stigma; Colarossi et al., 2016 ). One study evaluated a city-level, culturally-tailored media intervention combined with an individual risk reduction curriculum in comparison to no city-level media and a general health curriculum ( Kerr et al., 2015 ). Study findings suggested that all media-exposed participants had greater HIV-related knowledge at 6 months, and those who received the media intervention and risk reduction content had lower stigma scores at 3 and 12 months. A community-level intervention designed to decrease HIV risk among young MSM via persuasive media communication and peer-led networking outreach reduced anal sex risk among participants who reported binge drinking and/or marijuana use; the effect was not sustained for those who used other drugs ( Lauby et al., 2017 ). Another community mobilization intervention (e.g., publicity, groups, and outreach) addressed psychosocial factors at individual, interpersonal, social, and structural levels and documented an increase in HIV testing and a reduction in condom-less sex (although not sustained at 6 months; Shelley et al., 2017 ).

Interventions targeting providers and care delivery increase risk screening, HIV testing, timely linkage to care, and PrEP access for eligible individuals. Similar to the ways lay health workers are activated internationally, Health Promotion Advocates were employed in pediatric emergency departments to survey patients (e.g., health risks, stresses, and needs; Bernstein et al., 2017 ). Positive screens triggered critical resources (e.g., brief conversation on risks and needs and treatment as indicated), and, as a result, the intervention extended emergency services beyond the scope of the presenting complaint, engaging more than 800 youth in critical services such as mental health treatment and HIV testing. By pairing intensive medical case management with formalized relationships with local health departments and resources and addressing structural barriers (e.g., ability to access HIV prevention, testing, and medical care), researchers were able to decrease the average number of days to link to care and maintain the decline over a 6-year period ( Miller et al., 2019 ). Ninety percent of those linked to care had an initial medical visit in 42 or fewer days postdiagnosis. The integration of PrEP referrals into STI partner services led to 54% of PrEP eligible men accepting a PrEP referral and a 2.5-fold increase in PrEP use after partner services among MSM ( Katz et al., 2019 ).

Another group had health professional students (e.g., medicine and pharmacy) provide education about PrEP to public health providers, contributing to an increase in PrEP prescriptions, including for PrEP-eligible at-risk groups who previously were not given prescriptions ( Bunting et al., 2020 ). An underway pilot targets training primary care providers to better understand historical influences of structural factors, assess structural vulnerability among patients, create a more integrated system of care (e.g., opioid use and HIV risk) and empathy and nonjudgement in patient interactions ( Bagchi, 2020 ). There is strong precedent for this, given that significant effects were noted in creating affirming environments for sexual and sex minority youth, including improvements in providers’ and staff’s knowledge and attitudes, clinical practices, individual practices, and perceived environmental friendliness/safety ( Jadwin-Cakmak et al., 2020 ).

Policy changes can hinder or advance HIV prevention efforts, and modeling is an effective strategy to project outcomes and identify targeted prevention strategies. In an examination of Washington, DC’s buffer zone policy—prohibition of syringe exchange program operations within 1,000 feet of schools—researchers found that adherence to this 1,000 Foot Rule reduced syringe exchange program operational space by more than 50% a year ( Allen et al., 2016 ). These restrictions on the amount of legal syringe exchange program operational space have a significant impact on service delivery among injection drug users, which in turn affects HIV transmission through syringe sharing ( Allen et al., 2016 ). Analysis of a natural policy intervention indicated that removing a ban that prohibited the use of federal funds for syringe exchange programs potentially averted 120 HIV cases ( Ruiz et al., 2016 ).

In examining which prevention approach would achieve the greatest impact on HIV transmission, in light of available resources, study findings suggested that targeted testing by venue is more cost effective than routine emergency department testing ($31,507 vs. $59,435, respectively; Holtgrave et al., 2016 ). Modeling of interventions in 6 cities indicated that HIV incidence could be reduced by up to 50% by 2030, with cost savings of $95,416 per quality-adjusted life-year, by implementing combinations of evidence-based interventions (e.g., medication for opioid use disorder, HIV testing, ART initiation, and retention; Nosyk et al., 2020 ). Of note, nurse-initiated rapid testing was included in the optimal combination that produced that greatest health benefit while remaining cost effective across all cities. An ongoing microenterprise RCT will determine the effects of multiple strategies (e.g., weekly text on job openings, educational sessions on HIV prevention, and $11,000 start-up grant) on sexual risk behaviors, employment, and HIV preventive behaviors among economically vulnerable African American young adults ( Mayo-Wilson et al., 2019 ); a paucity of reviewed studies focus in this area. A comparable holistic health demonstration project, which engaged young Black MSM, successfully achieved viral suppression, connected participants to employment opportunities, and addressed housing discrimination ( Brewer et al., 2019 ).

Discussion and Future Considerations for Nursing Science

This review of current HIV prevention interventions provides a substantial contribution to the literature by synthesizing literature on four key areas of HIV prevention science. Nursing focuses on holistic care, assessing, diagnosing, and treating all areas that influence individual and population health. As we consider where and how to develop these programs, research indicates that more people may receive HIV prevention interventions in community-based clinics than in primary care or acute care settings ( Levy et al., 2016 ). Future nursing research should aim to address the needs of underserved populations who may benefit from robust HIV prevention strategies as outlined in this discussion section.

As we continue to generate knowledge about the multidimensional nature of HIV risk, especially for marginalized and vulnerable populations, there are increasing opportunities to learn from and use previous research to design multilevel and combination intervention strategies to better overcome barriers to HIV prevention ( Brawner, 2014 ; Frew et al., 2016 ). As suggested by the identified behavioral intervention studies, classic and current prevention programs have used useful strategies, but there remains room for improvement. These studies advance the science of HIV prevention, which helps fill gaps in the current literature and offer valuable insights that can contribute toward advancing the plan of Ending the HIV Epidemic ( U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2019 ; Treston, 2019 ).

As behavioral interventions continue to be created, replicated, and adapted, researchers should focus on implementing and testing these interventions in real-life settings. Implementation science strategies include planning, education, finance, restructuring, quality management, and policy strategies ( Powell et al., 2012 ). These strategies include various aspects of collecting data from stakeholders and community members, assessing setting readiness, determining realistic dosing, and assessing intervention acceptability and feasibility among target populations. The translation of science from research settings to real-life settings is imperative in the sustainability of efficacious behavioral interventions.

Technological

Although there is a plethora of technological-based HIV interventions with many in the pipeline, gaps persist in the current literature. There is a lack of precise knowledge regarding the content components of these interventions that are associated with improving clinical outcomes ( Dillingham et al., 2018 ; Ramos, 2017 ). There is also limited knowledge of optimal delivery approaches for these types of digital HIV interventions ( Côté et al., 2015 ; Schnall et al., 2015 ). In addition, there is a dearth of studies evaluating the efficacy, effectiveness, and cost effectiveness of using emerging technologies in HIV prevention interventions, such as gaming, gamification, social media, and virtual interventions ( Garett et al., 2016 ; Kemp & Velloza, 2018 ; LeGrand et al., 2018 ). Furthermore, there is a lack of resource-sharing platforms that would allow for new research to build on impactful elements of technology-based HIV prevention interventions without recreation of these components. Making these components available in an open platform would substantially reduce time and costs of developing new technological interventions and prevent wasteful use of resources on elements that do lead to desired outcomes.

In all, because technology continues to evolve and potential users of these interventions gain more access and complex skills in the use of other applications in everyday life, the demand for more user-centric HIV prevention interventions will likely continue to grow. Current interventions will need to be updated to maintain relevance, and new interventions will need to be designed to be adaptable to continuing technological advances. Policymakers have a role to play in allowing for governmental sharable databases of impactful interventions so that limited resources can be used to design predictably effective components of technological interventions leading to better health outcomes.

The nurse plays a vital role in HIV prevention and PrEP care ( O’Byrne et al., 2014 ). The University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing, recently developed and validated a set of entry-level nurse practioner competencies to provide culturally appropriate comprehensive HIV care ( Portillo et al., 2016 ). Similar programs should be implemented to train nurses and further the delivery of nursing-led biomedical HIV interventions. Magnet is a nurse-led clinic in San Francisco that has successfully leveraged expanded scopes of practice to allow for nurses to practice to the full extent of their licensure and allow for the rapid expansion of PrEP services to the community ( Holjilla et al., 2018 ). Such a unique and successful community-based PrEP delivery intervention led to the development and implementation of pharmacist-led PrEP clinics ( Havens et al., 2019 ; Lopez et al., 2020 ; Tung et al., 2018 ). More community-based, nursing-led biomedical HIV interventions are needed. Furthermore, future research should explore the efficacy of biomedical HIV prevention among transmasculine and cis-women populations, especially those of color who are underrepresented in existing research efforts ( Bond & Gunn, 2016 ; Chandler et al., 2020 ; Deutsch et al., 2015 ; Golub et al., 2019 ; Rowniak et al., 2017 ; Willie et al., 2017 ). Community-based nursing-led HIV interventions may be opportune for reaching these populations.

Structural and Community

Most HIV prevention structural- and community-level interventions still focus on developing countries, with less attention in the United States ( Adimora & Auerbach, 2010 ). However, with several communities facing limited resources, large percentages of individuals living below the federal poverty level and high HIV incidence and prevalence rates, it is time to expand these international success stories to domestic work (e.g., microfinance, credit programs, and comprehensive sexual health education). There is also a paucity of these interventions targeted to women and youth. Relative to the other reviewed strategies, very few nurses are engaged in structural-/community-level interventions. If successful, the in-progress microenterprise RCT by Mayo-Wilson et al. (2019) has the potential to serve as a blueprint for integrating multiple structural approaches that have demonstrated effectiveness abroad into U.S. contexts. The work by Werb et al. (2016) can also transform approaches to structural approaches to prevent injection drug initiation—given nursing’s focus on prevention, initiation of, and/or partnership in such work could be pivotal.

An approach to consider moving forward is applying the multiphase optimization strategy (MOST) to HIV prevention strategies ( Collins et al., 2016 ). MOST uses randomized experimentation to assess the individual performance of each intervention component. This rigorous process, based on a priori optimization criteria (e.g., cost and time), identifies whether aspects of an intervention component (e.g., presence, absence, and setting) have an impact on the performance of other components. Ultimately, this knowledge is used to engineer an intervention that is effective, efficient, and readily scalable. Multilevel interventions that target more than one level can lead to the most sustainable behavior change and can be delivered in venues known to be associated with HIV risk (e.g., bars and nightclubs; Pitpitan & Kalichman, 2016 ). An ongoing study on neighborhood contexts (e.g., poverty, HIV prevalence, and access to care) and network characteristics (e.g., size and frequency of communication) among Black MSM in the deep south will generate rich data to inform interventions for this key demographic ( Duncan et al., 2019 ). There also remains a need for explicit research with transgender populations—versus only including them in other samples—to fill gaps and meet unique needs ( Mayer et al., 2016 ).

Nursing Advancements

Nurse scientists around the globe are contributing to the development of interventions along the care continuum. Jemmott et al. have created numerous behavioral interventions over the past 30 years, which have been adapted for use in new settings and with different populations ( Advancing Health Equity: ETR, 2019 ). Behavioral interventions have been implemented using technology. Nursing exemplars in technology include the development of an immersive adventure game for African American adolescents ( Enah et al., 2019 ; Enahet al., 2015). In a series of studies in the primary prevention end of the prevention and care continuum, Enah et al. studied relevant content and design elements, evaluated an existing web-based game for relevance, developed and qualitatively studied acceptability of an individually tailored adventure game, and evaluated the potential efficacy of the game among African American adolescents ( Enah et al., 2019 ; Enah, Piper & Moneyham, 2015 ). At the care end of the continuum, Schnall et al. adapted an existing intervention for MSM ( Schnall et al., 2016 ), addressing co-morbidities for PLWH using multimodal techniques ( Schnall et al., 2019 ).

Flores developed a novel sex communication video series to support parent–child communication for gay, bisexual, and queer male adolescents ( Flores et al., 2020 ). Nurses have also collaborated on telehealth interventions to identify barriers to HIV care access and adherence and address mental health, substance use, and other issues among youth and young adults living with HIV ( Wootton et al., 2019 ). Other researchers piloted HIV/STI prevention content curated from online resources (e.g., YouTube and public and private websites) and found that youth who received links to publicly accessible online prevention content had a significant improvement in HIV self-efficacy and a significant reduction in unprotected vaginal or anal sex ( Whiteley et al., 2018 ). Nurses can partner with public health experts, computer scientists, and others to leverage these resources for population health improvement because new technologies continue to emerge ( Rhodes, McCoy, et al., 2016 ; Stevens et al., 2017 ; Stevens et al., 2020 ). Nurses, including members of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, have also been instrumental in the All of Us Research Program, a National Institutes of Health initiative aiming to enroll one million people across the United States to increase accessibility to data on individual variability in factors including genetics, lifestyle, and socioeconomic determinants of health to speed up medical breakthroughs ( National Institutes of Health, 2020 ).

As experts in community-engaged HIV research, partnerships that are committed to engaging key communities will lead to the development of interventions—across levels—to help achieve national goals of ending the HIV epidemic by 2030 ( Fauci et al., 2019 ). Health departments, academia, and community partners can also collaborate on policy modeling to improve resource allocation and better address HIV prevention priority setting ( Holtgrave et al., 2016 ). Investigators have also called for legal reform to address state-level structural stigma (index including density of same-sex couples and state laws protecting sexual minorities) experienced by MSM, given linkages between decreased state-level stigma and reduced condomless anal intercourse and increased PEP and/or PrEP use ( Oldenburg et al., 2015 ). Geographic information systems mapping can also be used to identify areas of greatest need and allocate necessary resources ( Brawner et al., 2017 ; Brawner, Reason, Goodman, Schensul, & Guthrie, 2015 ; Eberhart et al., 2015 ).

Recommendations to Further Advance HIV Prevention Intervention Science

Based on the literature reviewed and gaps identified, we offer three recommendations to further advance HIV prevention intervention science. First, nurses should leverage transdisciplinary partnerships to lead the development and testing of comprehensive interventions. For example, nurses could develop and test a nurse-delivered intervention model that engages pharmacists for PrEP access, psychologists and social workers for mental health treatment, librarians and health communication scholars for improving health literacy, and health informaticists to program the content for virtual delivery. Second, nurse researchers are at the cutting edge of knowledge generation in multiple fields, including HIV science (as evidenced by this review), and should be highly sought after for research collaboration accordingly. Although nursing is one of the most trusted professions, nurses are often overlooked when researchers in other disciplines search for collaborators with advanced methodological skill sets, content-specific expertise, or additional perceived benefits to their research teams. Finally, regardless of the intervention type (e.g., behavioral and biomedical), future intervention work must account for social and structural challenges experienced by the intended intervention recipients (e.g., racism, homelessness, and concentrated poverty in neighborhoods). This could include activities such as adding social service linkages to research protocols (e.g., providing participants with information on stable housing programs) or implementing structural interventions to improve neighborhood conditions (e.g., hiring community members to green vacant lots).

Nurses have made tremendous strides in behavioral interventions; however, representation in biomedical-, technological-, and structural-/community-level interventions is limited. We believe this hinders possible advancements in HIV prevention science, given the uniqueness a nursing lens contributes to research endeavors. We encourage nurses to expand the scope of their intervention work, and for individuals working in fields of HIV prevention where nurses are underrepresented, to seek out nursing collaborators. Together, these transdisciplinary teams can curb the epidemic and achieve an AIDS-free generation.

Key Considerations

- Nurses should leverage transdisciplinary partnerships to lead the development and testing of comprehensive interventions.

- Future intervention work must account for social and structural challenges experienced by the intended intervention recipients.

- Nurse researchers should be used for their advanced methodological skill sets and expertise in HIV prevention science.

Disclosures

The authors report no real or perceived vested interests related to this article that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

- Adimora AA, & Auerbach JD (2010). Structural interventions for HIV prevention in the United States . Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes , 55 ( Suppl 2 ), S132–S135. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Advancing Health Equity: ETR. (2019). Be Proud! Be Responsible! An Evidence-Based Intervention to Empower Youth to Reduce Their Risk of HIV . Retrieved from https://www.etr.org/ebi/programs/be-proud-be-responsible/

- Alarcón Gutiérrez M, Fernández Quevedo M, Martín Valle S, Jacques-Aviñó C, Díez David E, Caylà JA, & García de Olalla P (2018). Acceptability and effectiveness of using mobile applications to promote HIV and other STI testing among men who have sex with men in Barcelona , Spain. Sexually Transmitted Infections , 94 ( 6 ), 443–448. 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053348 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ali S, Al Rawwad T, Leal RM, Wilson MI, Mancillas A, Keo-Meier B, & Torres LR (2017). SMART cougars: Development and feasibility of a campus-based HIV prevention intervention . Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved , 28 ( 2 ), 81–99. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Allen ST, Ruiz MS, & Jones J (2016). Quantifying syringe exchange program operational space in the District of Columbia . AIDS and Behavior , 20 ( 12 ), 2933–2940. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aral SO, O’Leary A, & Baker C (2020). Sexually transmitted infections and HIV in the southern United States: An overview . Sexually Transmitted Diseases , 33 ( 7 ), S1–S5. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000223249.04456.76 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Arnold EA, Kegeles SM, Pollack LM, Neilands TB, Cornwell SM, Stewart WR, Benjamin M, Weeks J, Lockett G, Smith CD, & Operario D (2019). A randomized controlled trial to reduce HIV-related risk in African American men who have sex with men and women: The Bruthas project . Prevention Science , 20 ( 1 ), 115–125. 10.1007/s11121-018-0965-7 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Azjen I (1991). The theory of planned behavior . Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes , 50 ( 2 ), 179–211. [ Google Scholar ]

- Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, Tappero JW, Bukusi EA, Cohen CR, Katabira E, Ronald A, Tumwesigye E, Were E, Fife KH, Kiarie J, Farquhar C, John-Stewart G, Kakia A, Odoyo J, Mucunguzi A, … & Celum C. (2012). Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women . New England Journal of Medicine , 367 ( 5 ), 399–410. 10.1056/NEJMoa1108524 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bagchi AD (2020). A structural competency curriculum for primary care providers to address the opioid use disorder, HIV, and hepatitis C syndemic . Frontiers in Public Health , 8 , 210. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bailey J, Mann S, Wayal S, Hunter R, Free C, Abraham C, & Murray E (2015). Sexual health promotion for young people delivered via digital media: A scoping review . 10.3310/phr03130 (Public Health Research) [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandura A (1991). Social cognitive theory of self-regulation . Organizational behavior and human decision processes , 50 ( 2 ), 248–287. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bandura A (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective . Annual Review of Psychology , 52 ( 1 ), 1–26. 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barry MC, Threats M, Blackburn NA, LeGrand S, Dong W, Pulley DV, Sallabank G, Harper GW, Hightow-Weidman LB, Bauermeister JA, & Muessig KE (2018). “Stay strong! Keep ya head up! Move on! It gets better!!!!”: Resilience processes in the healthMpowerment online intervention of young black gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men . AIDS Care , 30 ( Suppl 5 ), S27–S38. 10.1080/09540121.2018.1510106 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bauermeister JA, Connochie D, Eaton L, Demers M, & Stephenson R (2017). Geospatial indicators of space and place: A review of multilevel studies of HIV prevention and care outcomes among young men who have sex with men in the United States . The Journal of Sex Research , 54 ( 4–5 ), 446–464. 10.1080/00224499.2016.1271862 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bauermeister JA, Golinkoff JM, Horvath KJ, Hightow-Weidman LB, Sullivan PS, & Stephenson R (2018). A multilevel tailored web app-based intervention for linking young men who have sex with men to quality care (get connected): Protocol for a randomized controlled trial . Journal of Medical Internet Research , 20 ( 8 ), 77. 10.2196/10444 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bauermeister JA, Tingler RC, Demers M, Connochie D, Gillard G, Shaver J, Chavanduka T, & Harper GW (2019). Acceptability and preliminary efficacy of an online HIV prevention intervention for single young men who have sex with men seeking partners online: The myDEx Project . AIDS and Behavior , 23 ( 11 ), 3064–3077. 10.1007/s10461-019-02426-7 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bekker L-G, Beyrer C, & Quinn TC (2012). Behavioral and biomedical combination strategies for HIV prevention . Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine , 2 ( 8 ), a007435. 10.1101/cshperspect.a007435 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Belenko S, Visher C, Pearson F, Swan H, Pich M, O’Connell D, Dembo R, Frisman L, Hamilton L, & Willett J (2017). Efficacy of structured organizational change intervention on HIV testing in correctional facilities . AIDS Education and Prevention , 29 ( 3 ), 241–255. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Belgrave FZ, & Abrams JA (2016). Reducing disparities and achieving equity in African American women’s health . American Psychologist , 71 ( 8 ), 723–733. 10.1037/amp0000081 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berkley-Patton J, Thompson CB, Moore E, Hawes S, Simon S, Goggin K, Martinez D, Berman M, & Booker A (2016). An HIV testing intervention in African American churches: Pilot study findings . Annals of Behavioral Medicine , 50 ( 3 ), 480–485. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berkley-Patton JY, Thompson CB, Moore E, Hawes S, Berman M, Allsworth J, Williams E, Wainright C, Bradley-Ewing A, Bauer AG, Catley D, & Goggin K (2019). Feasibility and outcomes of an HIV testing intervention in African American churches . AIDS and Behavior , 23 ( 1 ), 76–90. 10.1007/s10461-018-2240-0 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bernstein J, Dorfman D, Lunstead J, Topp D, Mamata H, Jaffer S, & Bernstein E (2017). Reaching adolescents for prevention: The role of pediatric emergency department health promotion advocates . Pediatric Emergency Care , 33 ( 4 ), 223–229. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Besoain F, Perez-Navarro A, Cayl JA, Avi CJ, & de Olalla P. G. a. (2015). Prevention of sexually transmitted infections using mobile devices and ubiquitous computing [Report] . International Journal of Health Geographics . 10.1186/s12942-015-0010-z [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Blankenship KM, Reinhard E, Sherman SG, & El-Bassel N (2015). Structural interventions for HIV prevention among women who use drugs: A global perspective . JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes , 69 , S140–S145. 10.1097/qai.0000000000000638 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bond KT, & Gunn AJ (2016). Perceived advantages and disadvantages of using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among sexually active Black women: An exploratory study . Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships , 3 ( 1 ), 1–24. 10.1353/bsr.2016.0019 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Bond KT, & Ramos SR (2019). Utilization of an animated electronic health video to increase knowledge of post- and pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV among African American women: Nationwide cross-sectional survey . JMIR Formative Research , 3 ( 2 ), e9995. 10.2196/formative.9995 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Boni RB, Lentini N, Santelli C, Barbosa A, Cruz M, Bingham T, Cota V, Correa RG, Veloso VG, & Grinsztejn B (2018). Self-testing, communication and information technology to promote HIV diagnosis among young gay and other men who have sex with men (MSM) in Brazil . Journal of the International AIDS Society , 21 ( Suppl 5 ), e25116. 10.1002/jia2.25116 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brawner BM (2014). A multilevel understanding of HIV/AIDS disease burden among African American women . Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, and Neonatal Nursing , 43 ( 5 ), 633–643. 10.1111/1552-6909.12481 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brawner BM, Abboud S, Reason J, Wingood G, & Jemmott LS (2019). The development of an innovative, theory-driven, psychoeducational HIV/STI prevention intervention for heterosexually active black adolescents with mental illnesses . Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies , 14 ( 2 ), 151–165. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brawner BM, Guthrie B, Stevens R, Taylor L, Eberhart M, & Schensul JJ (2017). Place still matters: Racial/ethnic and geographic disparities in HIV transmission and disease burden . Journal of Urban Health , 94 , 716–729. 10.1007/s11524-017-0198-2 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brawner BM, Reason JL, Goodman BA, Schensul JJ, & Guthrie B (2015). Multilevel drivers of human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immune deficiency syndrome among Black Philadelphians: Exploration using community ethnography and geographic information systems . Nursing Research , 64 ( 2 ), 100–110. 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000076 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]