Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

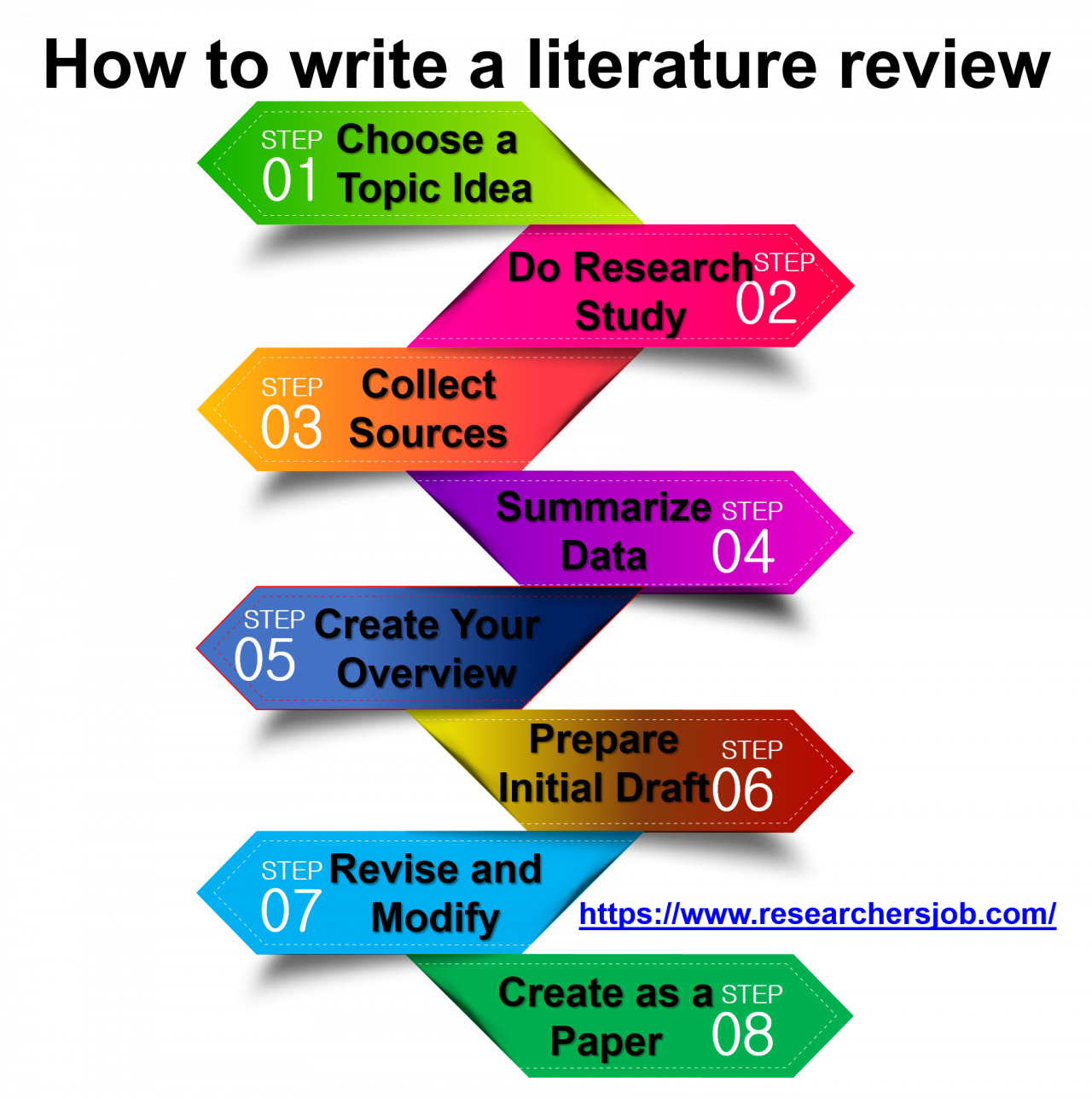

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved August 5, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, get unlimited documents corrected.

✔ Free APA citation check included ✔ Unlimited document corrections ✔ Specialized in correcting academic texts

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).

- Thematic : If you have found some recurring central themes that you will continue working with throughout your piece, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic. For example, if you are reviewing literature about women and religion, key themes can include the role of women in churches and the religious attitude towards women.

- Qualitative versus quantitative research

- Empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the research by sociological, historical, or cultural sources

- Theoretical : In many humanities articles, the literature review is the foundation for the theoretical framework. You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts. You can argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach or combine various theorical concepts to create a framework for your research.

What are some strategies or tips I can use while writing my lit review?

Any lit review is only as good as the research it discusses; make sure your sources are well-chosen and your research is thorough. Don’t be afraid to do more research if you discover a new thread as you’re writing. More info on the research process is available in our "Conducting Research" resources .

As you’re doing your research, create an annotated bibliography ( see our page on the this type of document ). Much of the information used in an annotated bibliography can be used also in a literature review, so you’ll be not only partially drafting your lit review as you research, but also developing your sense of the larger conversation going on among scholars, professionals, and any other stakeholders in your topic.

Usually you will need to synthesize research rather than just summarizing it. This means drawing connections between sources to create a picture of the scholarly conversation on a topic over time. Many student writers struggle to synthesize because they feel they don’t have anything to add to the scholars they are citing; here are some strategies to help you:

- It often helps to remember that the point of these kinds of syntheses is to show your readers how you understand your research, to help them read the rest of your paper.

- Writing teachers often say synthesis is like hosting a dinner party: imagine all your sources are together in a room, discussing your topic. What are they saying to each other?

- Look at the in-text citations in each paragraph. Are you citing just one source for each paragraph? This usually indicates summary only. When you have multiple sources cited in a paragraph, you are more likely to be synthesizing them (not always, but often

- Read more about synthesis here.

The most interesting literature reviews are often written as arguments (again, as mentioned at the beginning of the page, this is discipline-specific and doesn’t work for all situations). Often, the literature review is where you can establish your research as filling a particular gap or as relevant in a particular way. You have some chance to do this in your introduction in an article, but the literature review section gives a more extended opportunity to establish the conversation in the way you would like your readers to see it. You can choose the intellectual lineage you would like to be part of and whose definitions matter most to your thinking (mostly humanities-specific, but this goes for sciences as well). In addressing these points, you argue for your place in the conversation, which tends to make the lit review more compelling than a simple reporting of other sources.

- Resources Home 🏠

- Try SciSpace Copilot

- Search research papers

- Add Copilot Extension

- Try AI Detector

- Try Paraphraser

- Try Citation Generator

- April Papers

- June Papers

- July Papers

How To Write A Literature Review - A Complete Guide

Table of Contents

A literature review is much more than just another section in your research paper. It forms the very foundation of your research. It is a formal piece of writing where you analyze the existing theoretical framework, principles, and assumptions and use that as a base to shape your approach to the research question.

Curating and drafting a solid literature review section not only lends more credibility to your research paper but also makes your research tighter and better focused. But, writing literature reviews is a difficult task. It requires extensive reading, plus you have to consider market trends and technological and political changes, which tend to change in the blink of an eye.

Now streamline your literature review process with the help of SciSpace Copilot. With this AI research assistant, you can efficiently synthesize and analyze a vast amount of information, identify key themes and trends, and uncover gaps in the existing research. Get real-time explanations, summaries, and answers to your questions for the paper you're reviewing, making navigating and understanding the complex literature landscape easier.

In this comprehensive guide, we will explore everything from the definition of a literature review, its appropriate length, various types of literature reviews, and how to write one.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a collation of survey, research, critical evaluation, and assessment of the existing literature in a preferred domain.

Eminent researcher and academic Arlene Fink, in her book Conducting Research Literature Reviews , defines it as the following:

“A literature review surveys books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated.

Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have explored while researching a particular topic, and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within a larger field of study.”

Simply put, a literature review can be defined as a critical discussion of relevant pre-existing research around your research question and carving out a definitive place for your study in the existing body of knowledge. Literature reviews can be presented in multiple ways: a section of an article, the whole research paper itself, or a chapter of your thesis.

A literature review does function as a summary of sources, but it also allows you to analyze further, interpret, and examine the stated theories, methods, viewpoints, and, of course, the gaps in the existing content.

As an author, you can discuss and interpret the research question and its various aspects and debate your adopted methods to support the claim.

What is the purpose of a literature review?

A literature review is meant to help your readers understand the relevance of your research question and where it fits within the existing body of knowledge. As a researcher, you should use it to set the context, build your argument, and establish the need for your study.

What is the importance of a literature review?

The literature review is a critical part of research papers because it helps you:

- Gain an in-depth understanding of your research question and the surrounding area

- Convey that you have a thorough understanding of your research area and are up-to-date with the latest changes and advancements

- Establish how your research is connected or builds on the existing body of knowledge and how it could contribute to further research

- Elaborate on the validity and suitability of your theoretical framework and research methodology

- Identify and highlight gaps and shortcomings in the existing body of knowledge and how things need to change

- Convey to readers how your study is different or how it contributes to the research area

How long should a literature review be?

Ideally, the literature review should take up 15%-40% of the total length of your manuscript. So, if you have a 10,000-word research paper, the minimum word count could be 1500.

Your literature review format depends heavily on the kind of manuscript you are writing — an entire chapter in case of doctoral theses, a part of the introductory section in a research article, to a full-fledged review article that examines the previously published research on a topic.

Another determining factor is the type of research you are doing. The literature review section tends to be longer for secondary research projects than primary research projects.

What are the different types of literature reviews?

All literature reviews are not the same. There are a variety of possible approaches that you can take. It all depends on the type of research you are pursuing.

Here are the different types of literature reviews:

Argumentative review

It is called an argumentative review when you carefully present literature that only supports or counters a specific argument or premise to establish a viewpoint.

Integrative review

It is a type of literature review focused on building a comprehensive understanding of a topic by combining available theoretical frameworks and empirical evidence.

Methodological review

This approach delves into the ''how'' and the ''what" of the research question — you cannot look at the outcome in isolation; you should also review the methodology used.

Systematic review

This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research and collect, report, and analyze data from the studies included in the review.

Meta-analysis review

Meta-analysis uses statistical methods to summarize the results of independent studies. By combining information from all relevant studies, meta-analysis can provide more precise estimates of the effects than those derived from the individual studies included within a review.

Historical review

Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, or phenomenon emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and identify future research's likely directions.

Theoretical Review

This form aims to examine the corpus of theory accumulated regarding an issue, concept, theory, and phenomenon. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories exist, the relationships between them, the degree the existing approaches have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested.

Scoping Review

The Scoping Review is often used at the beginning of an article, dissertation, or research proposal. It is conducted before the research to highlight gaps in the existing body of knowledge and explains why the project should be greenlit.

State-of-the-Art Review

The State-of-the-Art review is conducted periodically, focusing on the most recent research. It describes what is currently known, understood, or agreed upon regarding the research topic and highlights where there are still disagreements.

Can you use the first person in a literature review?

When writing literature reviews, you should avoid the usage of first-person pronouns. It means that instead of "I argue that" or "we argue that," the appropriate expression would be "this research paper argues that."

Do you need an abstract for a literature review?

Ideally, yes. It is always good to have a condensed summary that is self-contained and independent of the rest of your review. As for how to draft one, you can follow the same fundamental idea when preparing an abstract for a literature review. It should also include:

- The research topic and your motivation behind selecting it

- A one-sentence thesis statement

- An explanation of the kinds of literature featured in the review

- Summary of what you've learned

- Conclusions you drew from the literature you reviewed

- Potential implications and future scope for research

Here's an example of the abstract of a literature review

Is a literature review written in the past tense?

Yes, the literature review should ideally be written in the past tense. You should not use the present or future tense when writing one. The exceptions are when you have statements describing events that happened earlier than the literature you are reviewing or events that are currently occurring; then, you can use the past perfect or present perfect tenses.

How many sources for a literature review?

There are multiple approaches to deciding how many sources to include in a literature review section. The first approach would be to look level you are at as a researcher. For instance, a doctoral thesis might need 60+ sources. In contrast, you might only need to refer to 5-15 sources at the undergraduate level.

The second approach is based on the kind of literature review you are doing — whether it is merely a chapter of your paper or if it is a self-contained paper in itself. When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. In the second scenario, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

Quick tips on how to write a literature review

To know how to write a literature review, you must clearly understand its impact and role in establishing your work as substantive research material.

You need to follow the below-mentioned steps, to write a literature review:

- Outline the purpose behind the literature review

- Search relevant literature

- Examine and assess the relevant resources

- Discover connections by drawing deep insights from the resources

- Structure planning to write a good literature review

1. Outline and identify the purpose of a literature review

As a first step on how to write a literature review, you must know what the research question or topic is and what shape you want your literature review to take. Ensure you understand the research topic inside out, or else seek clarifications. You must be able to the answer below questions before you start:

- How many sources do I need to include?

- What kind of sources should I analyze?

- How much should I critically evaluate each source?

- Should I summarize, synthesize or offer a critique of the sources?

- Do I need to include any background information or definitions?

Additionally, you should know that the narrower your research topic is, the swifter it will be for you to restrict the number of sources to be analyzed.

2. Search relevant literature

Dig deeper into search engines to discover what has already been published around your chosen topic. Make sure you thoroughly go through appropriate reference sources like books, reports, journal articles, government docs, and web-based resources.

You must prepare a list of keywords and their different variations. You can start your search from any library’s catalog, provided you are an active member of that institution. The exact keywords can be extended to widen your research over other databases and academic search engines like:

- Google Scholar

- Microsoft Academic

- Science.gov

Besides, it is not advisable to go through every resource word by word. Alternatively, what you can do is you can start by reading the abstract and then decide whether that source is relevant to your research or not.

Additionally, you must spend surplus time assessing the quality and relevance of resources. It would help if you tried preparing a list of citations to ensure that there lies no repetition of authors, publications, or articles in the literature review.

3. Examine and assess the sources

It is nearly impossible for you to go through every detail in the research article. So rather than trying to fetch every detail, you have to analyze and decide which research sources resemble closest and appear relevant to your chosen domain.

While analyzing the sources, you should look to find out answers to questions like:

- What question or problem has the author been describing and debating?

- What is the definition of critical aspects?

- How well the theories, approach, and methodology have been explained?

- Whether the research theory used some conventional or new innovative approach?

- How relevant are the key findings of the work?

- In what ways does it relate to other sources on the same topic?

- What challenges does this research paper pose to the existing theory

- What are the possible contributions or benefits it adds to the subject domain?

Be always mindful that you refer only to credible and authentic resources. It would be best if you always take references from different publications to validate your theory.

Always keep track of important information or data you can present in your literature review right from the beginning. It will help steer your path from any threats of plagiarism and also make it easier to curate an annotated bibliography or reference section.

4. Discover connections

At this stage, you must start deciding on the argument and structure of your literature review. To accomplish this, you must discover and identify the relations and connections between various resources while drafting your abstract.

A few aspects that you should be aware of while writing a literature review include:

- Rise to prominence: Theories and methods that have gained reputation and supporters over time.

- Constant scrutiny: Concepts or theories that repeatedly went under examination.

- Contradictions and conflicts: Theories, both the supporting and the contradictory ones, for the research topic.

- Knowledge gaps: What exactly does it fail to address, and how to bridge them with further research?

- Influential resources: Significant research projects available that have been upheld as milestones or perhaps, something that can modify the current trends

Once you join the dots between various past research works, it will be easier for you to draw a conclusion and identify your contribution to the existing knowledge base.

5. Structure planning to write a good literature review

There exist different ways towards planning and executing the structure of a literature review. The format of a literature review varies and depends upon the length of the research.

Like any other research paper, the literature review format must contain three sections: introduction, body, and conclusion. The goals and objectives of the research question determine what goes inside these three sections.

Nevertheless, a good literature review can be structured according to the chronological, thematic, methodological, or theoretical framework approach.

Literature review samples

1. Standalone

2. As a section of a research paper

How SciSpace Discover makes literature review a breeze?

SciSpace Discover is a one-stop solution to do an effective literature search and get barrier-free access to scientific knowledge. It is an excellent repository where you can find millions of only peer-reviewed articles and full-text PDF files. Here’s more on how you can use it:

Find the right information

Find what you want quickly and easily with comprehensive search filters that let you narrow down papers according to PDF availability, year of publishing, document type, and affiliated institution. Moreover, you can sort the results based on the publishing date, citation count, and relevance.

Assess credibility of papers quickly

When doing the literature review, it is critical to establish the quality of your sources. They form the foundation of your research. SciSpace Discover helps you assess the quality of a source by providing an overview of its references, citations, and performance metrics.

Get the complete picture in no time

SciSpace Discover’s personalized suggestion engine helps you stay on course and get the complete picture of the topic from one place. Every time you visit an article page, it provides you links to related papers. Besides that, it helps you understand what’s trending, who are the top authors, and who are the leading publishers on a topic.

Make referring sources super easy

To ensure you don't lose track of your sources, you must start noting down your references when doing the literature review. SciSpace Discover makes this step effortless. Click the 'cite' button on an article page, and you will receive preloaded citation text in multiple styles — all you've to do is copy-paste it into your manuscript.

Final tips on how to write a literature review

A massive chunk of time and effort is required to write a good literature review. But, if you go about it systematically, you'll be able to save a ton of time and build a solid foundation for your research.

We hope this guide has helped you answer several key questions you have about writing literature reviews.

Would you like to explore SciSpace Discover and kick off your literature search right away? You can get started here .

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. how to start a literature review.

• What questions do you want to answer?

• What sources do you need to answer these questions?

• What information do these sources contain?

• How can you use this information to answer your questions?

2. What to include in a literature review?

• A brief background of the problem or issue

• What has previously been done to address the problem or issue

• A description of what you will do in your project

• How this study will contribute to research on the subject

3. Why literature review is important?

The literature review is an important part of any research project because it allows the writer to look at previous studies on a topic and determine existing gaps in the literature, as well as what has already been done. It will also help them to choose the most appropriate method for their own study.

4. How to cite a literature review in APA format?

To cite a literature review in APA style, you need to provide the author's name, the title of the article, and the year of publication. For example: Patel, A. B., & Stokes, G. S. (2012). The relationship between personality and intelligence: A meta-analysis of longitudinal research. Personality and Individual Differences, 53(1), 16-21

5. What are the components of a literature review?

• A brief introduction to the topic, including its background and context. The introduction should also include a rationale for why the study is being conducted and what it will accomplish.

• A description of the methodologies used in the study. This can include information about data collection methods, sample size, and statistical analyses.

• A presentation of the findings in an organized format that helps readers follow along with the author's conclusions.

6. What are common errors in writing literature review?

• Not spending enough time to critically evaluate the relevance of resources, observations and conclusions.

• Totally relying on secondary data while ignoring primary data.

• Letting your personal bias seep into your interpretation of existing literature.

• No detailed explanation of the procedure to discover and identify an appropriate literature review.

7. What are the 5 C's of writing literature review?

• Cite - the sources you utilized and referenced in your research.

• Compare - existing arguments, hypotheses, methodologies, and conclusions found in the knowledge base.

• Contrast - the arguments, topics, methodologies, approaches, and disputes that may be found in the literature.

• Critique - the literature and describe the ideas and opinions you find more convincing and why.

• Connect - the various studies you reviewed in your research.

8. How many sources should a literature review have?

When it is just a chapter, sources should equal the total number of pages in your article's body. if it is a self-contained paper in itself, you need at least three times as many sources as there are pages in your work.

9. Can literature review have diagrams?

• To represent an abstract idea or concept

• To explain the steps of a process or procedure

• To help readers understand the relationships between different concepts

10. How old should sources be in a literature review?

Sources for a literature review should be as current as possible or not older than ten years. The only exception to this rule is if you are reviewing a historical topic and need to use older sources.

11. What are the types of literature review?

• Argumentative review

• Integrative review

• Methodological review

• Systematic review

• Meta-analysis review

• Historical review

• Theoretical review

• Scoping review

• State-of-the-Art review

12. Is a literature review mandatory?

Yes. Literature review is a mandatory part of any research project. It is a critical step in the process that allows you to establish the scope of your research, and provide a background for the rest of your work.

But before you go,

- Six Online Tools for Easy Literature Review

- Evaluating literature review: systematic vs. scoping reviews

- Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review

- Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples

You might also like

Consensus GPT vs. SciSpace GPT: Choose the Best GPT for Research

Literature Review and Theoretical Framework: Understanding the Differences

Types of Essays in Academic Writing - Quick Guide (2024)

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- CAREER FEATURE

- 04 December 2020

- Correction 09 December 2020

How to write a superb literature review

Andy Tay is a freelance writer based in Singapore.

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Credit: Getty

Literature reviews are important resources for scientists. They provide historical context for a field while offering opinions on its future trajectory. Creating them can provide inspiration for one’s own research, as well as some practice in writing. But few scientists are trained in how to write a review — or in what constitutes an excellent one. Even picking the appropriate software to use can be an involved decision (see ‘Tools and techniques’). So Nature asked editors and working scientists with well-cited reviews for their tips.

WENTING ZHAO: Be focused and avoid jargon

Assistant professor of chemical and biomedical engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore.

When I was a research student, review writing improved my understanding of the history of my field. I also learnt about unmet challenges in the field that triggered ideas.

For example, while writing my first review 1 as a PhD student, I was frustrated by how poorly we understood how cells actively sense, interact with and adapt to nanoparticles used in drug delivery. This experience motivated me to study how the surface properties of nanoparticles can be modified to enhance biological sensing. When I transitioned to my postdoctoral research, this question led me to discover the role of cell-membrane curvature, which led to publications and my current research focus. I wouldn’t have started in this area without writing that review.

Collection: Careers toolkit

A common problem for students writing their first reviews is being overly ambitious. When I wrote mine, I imagined producing a comprehensive summary of every single type of nanomaterial used in biological applications. It ended up becoming a colossal piece of work, with too many papers discussed and without a clear way to categorize them. We published the work in the end, but decided to limit the discussion strictly to nanoparticles for biological sensing, rather than covering how different nanomaterials are used in biology.

My advice to students is to accept that a review is unlike a textbook: it should offer a more focused discussion, and it’s OK to skip some topics so that you do not distract your readers. Students should also consider editorial deadlines, especially for invited reviews: make sure that the review’s scope is not so extensive that it delays the writing.

A good review should also avoid jargon and explain the basic concepts for someone who is new to the field. Although I trained as an engineer, I’m interested in biology, and my research is about developing nanomaterials to manipulate proteins at the cell membrane and how this can affect ageing and cancer. As an ‘outsider’, the reviews that I find most useful for these biological topics are those that speak to me in accessible scientific language.

Bozhi Tian likes to get a variety of perspectives into a review. Credit: Aleksander Prominski

BOZHI TIAN: Have a process and develop your style

Associate professor of chemistry, University of Chicago, Illinois.

In my lab, we start by asking: what is the purpose of this review? My reasons for writing one can include the chance to contribute insights to the scientific community and identify opportunities for my research. I also see review writing as a way to train early-career researchers in soft skills such as project management and leadership. This is especially true for lead authors, because they will learn to work with their co-authors to integrate the various sections into a piece with smooth transitions and no overlaps.

After we have identified the need and purpose of a review article, I will form a team from the researchers in my lab. I try to include students with different areas of expertise, because it is useful to get a variety of perspectives. For example, in the review ‘An atlas of nano-enabled neural interfaces’ 2 , we had authors with backgrounds in biophysics, neuroengineering, neurobiology and materials sciences focusing on different sections of the review.

After this, I will discuss an outline with my team. We go through multiple iterations to make sure that we have scanned the literature sufficiently and do not repeat discussions that have appeared in other reviews. It is also important that the outline is not decided by me alone: students often have fresh ideas that they can bring to the table. Once this is done, we proceed with the writing.

I often remind my students to imagine themselves as ‘artists of science’ and encourage them to develop how they write and present information. Adding more words isn’t always the best way: for example, I enjoy using tables to summarize research progress and suggest future research trajectories. I’ve also considered including short videos in our review papers to highlight key aspects of the work. I think this can increase readership and accessibility because these videos can be easily shared on social-media platforms.

ANKITA ANIRBAN: Timeliness and figures make a huge difference

Editor, Nature Reviews Physics .

One of my roles as a journal editor is to evaluate proposals for reviews. The best proposals are timely and clearly explain why readers should pay attention to the proposed topic.

It is not enough for a review to be a summary of the latest growth in the literature: the most interesting reviews instead provide a discussion about disagreements in the field.

Careers Collection: Publishing

Scientists often centre the story of their primary research papers around their figures — but when it comes to reviews, figures often take a secondary role. In my opinion, review figures are more important than most people think. One of my favourite review-style articles 3 presents a plot bringing together data from multiple research papers (many of which directly contradict each other). This is then used to identify broad trends and suggest underlying mechanisms that could explain all of the different conclusions.

An important role of a review article is to introduce researchers to a field. For this, schematic figures can be useful to illustrate the science being discussed, in much the same way as the first slide of a talk should. That is why, at Nature Reviews, we have in-house illustrators to assist authors. However, simplicity is key, and even without support from professional illustrators, researchers can still make use of many free drawing tools to enhance the value of their review figures.

Yoojin Choi recommends that researchers be open to critiques when writing reviews. Credit: Yoojin Choi

YOOJIN CHOI: Stay updated and be open to suggestions

Research assistant professor, Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology, Daejeon.

I started writing the review ‘Biosynthesis of inorganic nanomaterials using microbial cells and bacteriophages’ 4 as a PhD student in 2018. It took me one year to write the first draft because I was working on the review alongside my PhD research and mostly on my own, with support from my adviser. It took a further year to complete the processes of peer review, revision and publication. During this time, many new papers and even competing reviews were published. To provide the most up-to-date and original review, I had to stay abreast of the literature. In my case, I made use of Google Scholar, which I set to send me daily updates of relevant literature based on key words.

Through my review-writing process, I also learnt to be more open to critiques to enhance the value and increase the readership of my work. Initially, my review was focused only on using microbial cells such as bacteria to produce nanomaterials, which was the subject of my PhD research. Bacteria such as these are known as biofactories: that is, organisms that produce biological material which can be modified to produce useful materials, such as magnetic nanoparticles for drug-delivery purposes.

Synchronized editing: the future of collaborative writing

However, when the first peer-review report came back, all three reviewers suggested expanding the review to cover another type of biofactory: bacteriophages. These are essentially viruses that infect bacteria, and they can also produce nanomaterials.

The feedback eventually led me to include a discussion of the differences between the various biofactories (bacteriophages, bacteria, fungi and microalgae) and their advantages and disadvantages. This turned out to be a great addition because it made the review more comprehensive.

Writing the review also led me to an idea about using nanomaterial-modified microorganisms to produce chemicals, which I’m still researching now.

PAULA MARTIN-GONZALEZ: Make good use of technology

PhD student, University of Cambridge, UK.

Just before the coronavirus lockdown, my PhD adviser and I decided to write a literature review discussing the integration of medical imaging with genomics to improve ovarian cancer management.

As I was researching the review, I noticed a trend in which some papers were consistently being cited by many other papers in the field. It was clear to me that those papers must be important, but as a new member of the field of integrated cancer biology, it was difficult to immediately find and read all of these ‘seminal papers’.

That was when I decided to code a small application to make my literature research more efficient. Using my code, users can enter a query, such as ‘ovarian cancer, computer tomography, radiomics’, and the application searches for all relevant literature archived in databases such as PubMed that feature these key words.

The code then identifies the relevant papers and creates a citation graph of all the references cited in the results of the search. The software highlights papers that have many citation relationships with other papers in the search, and could therefore be called seminal papers.

My code has substantially improved how I organize papers and has informed me of key publications and discoveries in my research field: something that would have taken more time and experience in the field otherwise. After I shared my code on GitHub, I received feedback that it can be daunting for researchers who are not used to coding. Consequently, I am hoping to build a more user-friendly interface in a form of a web page, akin to PubMed or Google Scholar, where users can simply input their queries to generate citation graphs.

Tools and techniques

Most reference managers on the market offer similar capabilities when it comes to providing a Microsoft Word plug-in and producing different citation styles. But depending on your working preferences, some might be more suitable than others.

Reference managers

Attribute | EndNote | Mendeley | Zotero | Paperpile |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Cost | A one-time cost of around US$340 but comes with discounts for academics; around $150 for students | Free version available | Free version available | Low and comes with academic discounts |

Level of user support | Extensive user tutorials available; dedicated help desk | Extensive user tutorials available; global network of 5,000 volunteers to advise users | Forum discussions to troubleshoot | Forum discussions to troubleshoot |

Desktop version available for offline use? | Available | Available | Available | Unavailable |

Document storage on cloud | Up to 2 GB (free version) | Up to 2 GB (free version) | Up to 300 MB (free version) | Storage linked to Google Drive |

Compatible with Google Docs? | No | No | Yes | Yes |

Supports collaborative working? | No group working | References can be shared or edited by a maximum of three other users (or more in the paid-for version) | No limit on the number of users | No limit on the number of users |

Here is a comparison of the more popular collaborative writing tools, but there are other options, including Fidus Writer, Manuscript.io, Authorea and Stencila.

Collaborative writing tools

Attribute | Manubot | Overleaf | Google Docs |

|---|---|---|---|

Cost | Free, open source | $15–30 per month, comes with academic discounts | Free, comes with a Google account |

Writing language | Type and write in Markdown* | Type and format in LaTex* | Standard word processor |

Can be used with a mobile device? | No | No | Yes |

References | Bibliographies are built using DOIs, circumventing reference managers | Citation styles can be imported from reference managers | Possible but requires additional referencing tools in a plug-in, such as Paperpile |

*Markdown and LaTex are code-based formatting languages favoured by physicists, mathematicians and computer scientists who code on a regular basis, and less popular in other disciplines such as biology and chemistry.

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-03422-x

Interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Updates & Corrections

Correction 09 December 2020 : An earlier version of the tables in this article included some incorrect details about the programs Zotero, Endnote and Manubot. These have now been corrected.

Hsing, I.-M., Xu, Y. & Zhao, W. Electroanalysis 19 , 755–768 (2007).

Article Google Scholar

Ledesma, H. A. et al. Nature Nanotechnol. 14 , 645–657 (2019).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Brahlek, M., Koirala, N., Bansal, N. & Oh, S. Solid State Commun. 215–216 , 54–62 (2015).

Choi, Y. & Lee, S. Y. Nature Rev. Chem . https://doi.org/10.1038/s41570-020-00221-w (2020).

Download references

Related Articles

- Research management

Why I’ve removed journal titles from the papers on my CV

Career Column 09 AUG 24

Why we quit: how ‘toxic management’ and pandemic pressures fuelled disillusionment in higher education

Career News 08 AUG 24

Scientists are falling victim to deepfake AI video scams — here’s how to fight back

Career Feature 07 AUG 24

Our local research project put us on the global stage — here’s how you can do it, too

Comment 06 AUG 24

Hybrid conferences should be the norm — optimize them so everyone benefits

Editorial 06 AUG 24

How a space physicist is shaking up China’s research funding

News Q&A 02 AUG 24

The UK launched a metascience unit. Will other countries follow suit?

Nature Index 07 AUG 24

Recruitment of Talent Positions at Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University

Call for top experts and scholars in the field of science and technology.

Shenyang, Liaoning, China

Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University

The Recruitment of Fuyao University of Science and Technology

This recruitment of Fuyao University Technologyof Science andUcovers 7 departments including the 6 Schools and the Faculty of Fundamental Disciplines.

Fuzhou, Fujian (CN)

Fuzhou FuYao Institute for Advanced Study

Educational Consultant

You will build and maintain strong relationships with local representatives, key distributors, schools, Ministries of Education, etc.

Riyadh - hybrid working model

Springer Nature Ltd

Senior Marketing Manager – Journal Awareness

Job Title: Senior Marketing Manager – Journal Awareness Location(s): London, UK - Hybrid Working Model Closing date: 25th August 2024 A...

London (Central), London (Greater) (GB)

Faculty Positions& Postdoctoral Research Fellow, School of Optical and Electronic Information, HUST

Job Opportunities: Leading talents, young talents, overseas outstanding young scholars, postdoctoral researchers.

Wuhan, Hubei, China

School of Optical and Electronic Information, Huazhong University of Science and Technology

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Reference management. Clean and simple.

Literature review

How to write a literature review in 6 steps

How do you write a good literature review? This step-by-step guide on how to write an excellent literature review covers all aspects of planning and writing literature reviews for academic papers and theses.

How to write a systematic literature review [9 steps]

How do you write a systematic literature review? What types of systematic literature reviews exist and where do you use them? Learn everything you need to know about a systematic literature review in this guide

What is a literature review? [with examples]

Not sure what a literature review is? This guide covers the definition, purpose, and format of a literature review.

Literature Review Example/Sample

Detailed Walkthrough + Free Literature Review Template

If you’re working on a dissertation or thesis and are looking for an example of a strong literature review chapter , you’ve come to the right place.

In this video, we walk you through an A-grade literature review from a dissertation that earned full distinction . We start off by discussing the five core sections of a literature review chapter by unpacking our free literature review template . This includes:

- The literature review opening/ introduction section

- The theoretical framework (or foundation of theory)

- The empirical research

- The research gap

- The closing section

We then progress to the sample literature review (from an A-grade Master’s-level dissertation) to show how these concepts are applied in the literature review chapter. You can access the free resources mentioned in this video below.

PS – If you’re working on a dissertation, be sure to also check out our collection of dissertation and thesis examples here .

FAQ: Literature Review Example

Literature review example: frequently asked questions, is the sample literature review real.

Yes. The literature review example is an extract from a Master’s-level dissertation for an MBA program. It has not been edited in any way.

Can I replicate this literature review for my dissertation?

As we discuss in the video, every literature review will be slightly different, depending on the university’s unique requirements, as well as the nature of the research itself. Therefore, you’ll need to tailor your literature review to suit your specific context.

You can learn more about the basics of writing a literature review here .

Where can I find more examples of literature reviews?

The best place to find more examples of literature review chapters would be within dissertation/thesis databases. These databases include dissertations, theses and research projects that have successfully passed the assessment criteria for the respective university, meaning that you have at least some sort of quality assurance.

The Open Access Thesis Database (OATD) is a good starting point.

How do I get the literature review template?

You can access our free literature review chapter template here .

Is the template really free?

Yes. There is no cost for the template and you are free to use it as you wish.

Psst… there’s more!

This post is an extract from our bestselling short course, Literature Review Bootcamp . If you want to work smart, you don't want to miss this .

What will it take for you to guide me in my Ph.D research work?

Thank you so much for all this information. I am unable to download the literature review template and the excel worksheet. When I click the button it takes me to the top of the page. I would really love to use this template, thank you again!

Submit a Comment Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Print Friendly

How to Write a Literature Review: Writing a Literature Review in APA Format

- Writing a Literature Review in APA Format

- Chicago/Turabian Citation Style

- Primary and Secondary Sources

- Basic Research Strategies

- Evaluating Sources

- Using the Library's Ebooks

- Using the Library's Catalog

- Copyright Information

- Contact Information & Feedback

Writing a Literature Review in APA

- << Previous: Videos

- Next: APA/Chicago/Turabian/MLA Citation Style >>

- Last Updated: Sep 25, 2023 2:24 PM

- URL: https://tuskegee.libguides.com/c.php?g=692585

How to Write a Literature Review

What is a literature review.

- What Is the Literature

- Writing the Review

A literature review is much more than an annotated bibliography or a list of separate reviews of articles and books. It is a critical, analytical summary and synthesis of the current knowledge of a topic. Thus it should compare and relate different theories, findings, etc, rather than just summarize them individually. In addition, it should have a particular focus or theme to organize the review. It does not have to be an exhaustive account of everything published on the topic, but it should discuss all the significant academic literature and other relevant sources important for that focus.

This is meant to be a general guide to writing a literature review: ways to structure one, what to include, how it supplements other research. For more specific help on writing a review, and especially for help on finding the literature to review, sign up for a Personal Research Session .

The specific organization of a literature review depends on the type and purpose of the review, as well as on the specific field or topic being reviewed. But in general, it is a relatively brief but thorough exploration of past and current work on a topic. Rather than a chronological listing of previous work, though, literature reviews are usually organized thematically, such as different theoretical approaches, methodologies, or specific issues or concepts involved in the topic. A thematic organization makes it much easier to examine contrasting perspectives, theoretical approaches, methodologies, findings, etc, and to analyze the strengths and weaknesses of, and point out any gaps in, previous research. And this is the heart of what a literature review is about. A literature review may offer new interpretations, theoretical approaches, or other ideas; if it is part of a research proposal or report it should demonstrate the relationship of the proposed or reported research to others' work; but whatever else it does, it must provide a critical overview of the current state of research efforts.

Literature reviews are common and very important in the sciences and social sciences. They are less common and have a less important role in the humanities, but they do have a place, especially stand-alone reviews.

Types of Literature Reviews

There are different types of literature reviews, and different purposes for writing a review, but the most common are:

- Stand-alone literature review articles . These provide an overview and analysis of the current state of research on a topic or question. The goal is to evaluate and compare previous research on a topic to provide an analysis of what is currently known, and also to reveal controversies, weaknesses, and gaps in current work, thus pointing to directions for future research. You can find examples published in any number of academic journals, but there is a series of Annual Reviews of *Subject* which are specifically devoted to literature review articles. Writing a stand-alone review is often an effective way to get a good handle on a topic and to develop ideas for your own research program. For example, contrasting theoretical approaches or conflicting interpretations of findings can be the basis of your research project: can you find evidence supporting one interpretation against another, or can you propose an alternative interpretation that overcomes their limitations?

- Part of a research proposal . This could be a proposal for a PhD dissertation, a senior thesis, or a class project. It could also be a submission for a grant. The literature review, by pointing out the current issues and questions concerning a topic, is a crucial part of demonstrating how your proposed research will contribute to the field, and thus of convincing your thesis committee to allow you to pursue the topic of your interest or a funding agency to pay for your research efforts.

- Part of a research report . When you finish your research and write your thesis or paper to present your findings, it should include a literature review to provide the context to which your work is a contribution. Your report, in addition to detailing the methods, results, etc. of your research, should show how your work relates to others' work.

A literature review for a research report is often a revision of the review for a research proposal, which can be a revision of a stand-alone review. Each revision should be a fairly extensive revision. With the increased knowledge of and experience in the topic as you proceed, your understanding of the topic will increase. Thus, you will be in a better position to analyze and critique the literature. In addition, your focus will change as you proceed in your research. Some areas of the literature you initially reviewed will be marginal or irrelevant for your eventual research, and you will need to explore other areas more thoroughly.

Examples of Literature Reviews

See the series of Annual Reviews of *Subject* which are specifically devoted to literature review articles to find many examples of stand-alone literature reviews in the biomedical, physical, and social sciences.

Research report articles vary in how they are organized, but a common general structure is to have sections such as:

- Abstract - Brief summary of the contents of the article

- Introduction - A explanation of the purpose of the study, a statement of the research question(s) the study intends to address

- Literature review - A critical assessment of the work done so far on this topic, to show how the current study relates to what has already been done

- Methods - How the study was carried out (e.g. instruments or equipment, procedures, methods to gather and analyze data)

- Results - What was found in the course of the study

- Discussion - What do the results mean

- Conclusion - State the conclusions and implications of the results, and discuss how it relates to the work reviewed in the literature review; also, point to directions for further work in the area

Here are some articles that illustrate variations on this theme. There is no need to read the entire articles (unless the contents interest you); just quickly browse through to see the sections, and see how each section is introduced and what is contained in them.

The Determinants of Undergraduate Grade Point Average: The Relative Importance of Family Background, High School Resources, and Peer Group Effects , in The Journal of Human Resources , v. 34 no. 2 (Spring 1999), p. 268-293.

This article has a standard breakdown of sections:

- Introduction

- Literature Review

- Some discussion sections

First Encounters of the Bureaucratic Kind: Early Freshman Experiences with a Campus Bureaucracy , in The Journal of Higher Education , v. 67 no. 6 (Nov-Dec 1996), p. 660-691.

This one does not have a section specifically labeled as a "literature review" or "review of the literature," but the first few sections cite a long list of other sources discussing previous research in the area before the authors present their own study they are reporting.

- Next: What Is the Literature >>

- Last Updated: Jan 11, 2024 9:48 AM

- URL: https://libguides.wesleyan.edu/litreview

- UWF Libraries

Literature Review: Conducting & Writing

- Sample Literature Reviews

- Steps for Conducting a Lit Review

- Finding "The Literature"

- Organizing/Writing

- APA Style This link opens in a new window

- Chicago: Notes Bibliography This link opens in a new window

- MLA Style This link opens in a new window

Sample Lit Reviews from Communication Arts

Have an exemplary literature review.

- Literature Review Sample 1

- Literature Review Sample 2

- Literature Review Sample 3

Have you written a stellar literature review you care to share for teaching purposes?

Are you an instructor who has received an exemplary literature review and have permission from the student to post?

Please contact Britt McGowan at [email protected] for inclusion in this guide. All disciplines welcome and encouraged.

- << Previous: MLA Style

- Next: Get Help! >>

- Last Updated: Aug 8, 2024 11:00 AM

- URL: https://libguides.uwf.edu/litreview

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Turk J Urol

- v.39(Suppl 1); 2013 Sep

How to write a review article?

In the medical sciences, the importance of review articles is rising. When clinicians want to update their knowledge and generate guidelines about a topic, they frequently use reviews as a starting point. The value of a review is associated with what has been done, what has been found and how these findings are presented. Before asking ‘how,’ the question of ‘why’ is more important when starting to write a review. The main and fundamental purpose of writing a review is to create a readable synthesis of the best resources available in the literature for an important research question or a current area of research. Although the idea of writing a review is attractive, it is important to spend time identifying the important questions. Good review methods are critical because they provide an unbiased point of view for the reader regarding the current literature. There is a consensus that a review should be written in a systematic fashion, a notion that is usually followed. In a systematic review with a focused question, the research methods must be clearly described. A ‘methodological filter’ is the best method for identifying the best working style for a research question, and this method reduces the workload when surveying the literature. An essential part of the review process is differentiating good research from bad and leaning on the results of the better studies. The ideal way to synthesize studies is to perform a meta-analysis. In conclusion, when writing a review, it is best to clearly focus on fixed ideas, to use a procedural and critical approach to the literature and to express your findings in an attractive way.