Tragic Tales and Epic Adventures: Essay Topics in Greek Mythology

Table of contents

- 1 Tips on Writing an Informative Essay on a Greek Mythical Character

- 2.1 Titles for Hero Essays

- 2.2 Ancient Greece Research Topics

- 2.3 Common Myth Ideas for Essays

- 2.4 Topics about Greek Gods

- 2.5 Love Topics in the Essay about Greek Mythology

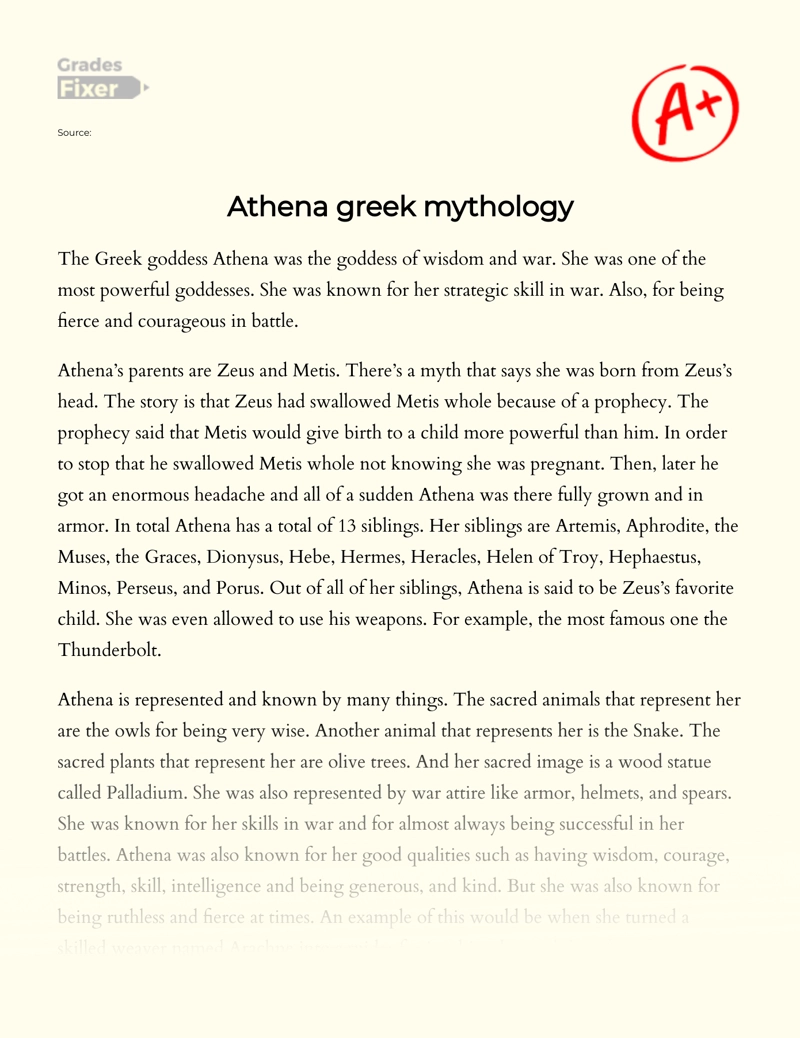

With its rich pantheon of gods, heroes, and timeless tales, Greek mythology has been a source of inspiration and fascination for centuries. From the mighty exploits of Hercules to the cunning of Odysseus, these myths offer a window into ancient Greek culture, values, and understanding of the world. This exploration delves into various aspects of Greek mythology topics, providing a wealth of ideas for a captivating essay. How do myths impact today’s society? Whether you’re drawn to the legendary heroes, the powerful gods, or the intricate relationships within these stories, there’s a trove of ideas to explore in Greek mythology research topics.

Tips on Writing an Informative Essay on a Greek Mythical Character

Crafting an informative essay on a Greek mythical character requires a blend of passionate storytelling, rigorous research, and insightful analysis. Yet, there are some tips you can follow to reach the best result. Read this student essay written about the Greek mythology guide.

- Select a Fascinating Character. Choose a Greek mythical character that genuinely interests you. Your passion for the character will enhance your writing and engage your readers.

- Conduct Thorough Research. Dive into the character’s background, roles in various myths, and their significance in Greek mythology. Use reliable sources such as academic papers, respected mythology books, and scholarly articles to gather comprehensive and accurate information.

- Analyze Characteristics and Symbolism. Explore the deeper meanings behind your character’s actions and traits. Discuss what they symbolize in Greek culture and mythology.

- Use a Clear Structure. Organize your essay logically. Ensure each paragraph flows smoothly to the next, maintaining a coherent and compelling narrative.

- Incorporate Quotes and References. Use quotes from primary sources and reference key scholars to support your points. This adds credibility and depth to your essay.

- Edit and Revise. Finally, thoroughly revise your essay for clarity, coherence, and grammatical accuracy. A well-edited essay ensures your ideas are conveyed effectively.

By following these tips, you can create a compelling essay that recounts famous myths and explores the rich symbolic and cultural significance of these timeless tales.

Greek Mythology Topics for an Essay

Explore the rich tapestry of Greek mythology ideas with these intriguing essay topics, encompassing legendary heroes, ancient gods, and the timeless themes that have captivated humanity for millennia. Dive into the stories of Hercules, the wisdom of Athena, the complexities of Olympian deities, and the profound lessons embedded in these ancient tales. Each topic offers a unique window into the world of Greek myths, inviting a deep exploration of its cultural and historical significance.

Titles for Hero Essays

- Hercules: Heroism and Humanity

- Achilles: The Warrior’s Tragedy

- Odysseus: Cunning over Strength

- Theseus and the Minotaur: Symbolism and Society

- Perseus and Medusa: A Tale of Courage

- Jason and the Argonauts: The Quest for the Golden Fleece

- Atalanta: Challenging Gender Roles

- Ajax: The Unsung Hero of the Trojan War

- Bellerophon and Pegasus: Conquest of the Skies

- Hector: The Trojan Hero

- Diomedes: The Underrated Warrior of the Iliad

- Heracles and the Twelve Labors: A Journey of Redemption

- Orpheus: The Power of Music and Love

- Castor and Pollux: The Gemini Twins

- Philoctetes: The Isolated Warrior

Ancient Greece Research Topics

- The Trojan War: Myth and History. Examining the blending of mythological and historical elements in the story of the Trojan War.

- The Role of Oracles in Ancient Greek Society. Exploring how oracles influenced decision-making and everyday life in Ancient Greece.

- Greek Mythology in Classical Art and Literature. Analyzing the representation and influence of Greek myths in classical art forms and literary works.

- The Historical Impact of Greek Gods on Ancient Civilizations. Investigating how the worship of Greek gods shaped the societal, cultural, and political landscapes of ancient civilizations.

- Mythology’s Influence on Ancient Greek Architecture. Studying the impact of mythological themes and figures on the architectural designs of Ancient Greece.

- Athenian Democracy and Mythology. Exploring the connections between the development of democracy in Athens and the city’s rich mythological traditions.

- Minoan Civilization and Greek Mythology. Delving into the influence of Greek mythology on the Minoan civilization, particularly in their art and religious practices.

- The Mycenaean Origins of Greek Myths. Tracing the roots of Greek mythology back to the Mycenaean civilization and its culture.

- Greek Mythology and the Development of Theater. Discuss how mythological stories and characters heavily influenced ancient Greek plays.

- Olympic Games and Mythological Foundations. Examining the mythological origins of the ancient Olympic Games and their cultural significance.

- Maritime Myths and Ancient Greek Navigation. Investigating how Greek myths reflected and influenced ancient Greek seafaring and exploration.

- The Impact of Hellenistic Culture on Mythology. Analyzing how Greek mythology evolved and spread during the Hellenistic period.

- Alexander the Great and Mythological Imagery. Studying the use of mythological symbolism and imagery in portraying Alexander the Great.

- Greek Gods in Roman Culture. Exploring how Greek mythology was adopted and adapted by the Romans.

- Spartan Society and Mythological Ideals. Examining Greek myths’ role in shaping ancient Sparta’s values and lifestyle.

Common Myth Ideas for Essays

- The Concept of Fate and Free Will in Greek Myths. Exploring how Greek mythology addresses the tension between destiny and personal choice.

- Mythological Creatures and Their Meanings. Analyzing the symbolism and cultural significance of creatures like the Minotaur, Centaurs, and the Hydra.

- The Underworld in Greek Mythology: A Journey Beyond. Delving into the Greek concept of the afterlife and the role of Hades.

- The Role of Women in Greek Myths. Examining the portrayal of female characters, goddesses, and heroines in Greek mythology.

- The Transformation Myths in Greek Lore. Investigating stories of metamorphosis and their symbolic meanings, such as Daphne and Narcissus.

- The Power of Prophecies in Greek Myths. Discussing the role and impact of prophetic declarations in Greek mythological narratives.

- Heroism and Hubris in Greek Mythology. Analyzing how pride and arrogance are depicted and punished in various myths.

- The Influence of Greek Gods in Human Affairs. Exploring stories where gods intervene in the lives of mortals, shaping their destinies.

- Nature and the Gods: Depictions of the Natural World. Examining how natural elements and phenomena are personified through gods and myths.

- The Significance of Sacrifice in Greek Myths. Investigating the theme of voluntary and forced sacrifice in mythological tales.

- Greek Mythology as a Reflection of Ancient Society. Analyzing how Greek myths mirror ancient Greek society’s social, political, and moral values.

- Mythical Quests and Adventures. Exploring the journeys and challenges heroes like Jason, Perseus, and Theseus face.

- The Origins of the Gods in Greek Mythology. Tracing the creation stories and familial relationships among the Olympian gods.

- Lessons in Morality from Greek Myths. Discussing the moral lessons and ethical dilemmas presented in Greek mythology.

- The Influence of Greek Myths on Modern Culture. Examining how elements of Greek mythology continue to influence contemporary literature, film, and art.

Topics about Greek Gods

- Zeus: King of Gods. Exploring Zeus’s leadership in Olympus, his divine relationships, and mortal interactions.

- Athena: Goddess of Wisdom and War. Analyzing Athena’s embodiment of intellect and battle strategy in myths.

- Apollo vs. Dionysus: Contrast of Sun and Ecstasy. Comparing Apollo’s rationality with Dionysus’s chaotic joy.

- Hera: Marriage and Jealousy. Examining Hera’s multifaceted nature, focusing on her matrimonial role and jealous tendencies.

- Poseidon: Ruler of Seas and Quakes. Investigating Poseidon’s dominion over the oceans and seismic events.

- Hades: Lord of the Underworld. Delving into Hades’s reign in the afterlife and associated myths.

- Aphrodite: Essence of Love and Charm. Exploring Aphrodite’s origins, romantic tales, and divine allure.

- Artemis: Protector of Wilderness. Discussing Artemis’s guardianship over nature and young maidens.

- Hephaestus: Craftsmanship and Fire. Analyzing Hephaestus’s skills in metallurgy and his divine role.

- Demeter: Goddess of Harvest and Seasons. Investigating Demeter’s influence on agriculture and seasonal cycles.

- Ares: Embodiment of Warfare. Delving into Ares’s aggressive aspects and divine relations.

- Hermes: Divine Messenger and Trickster. Exploring Hermes’s multifaceted roles in Olympian affairs.

- Dionysus: Deity of Revelry and Wine. Analyzing Dionysus’s cultural impact and festive nature.

- Persephone: Underworld’s Queen. Discussing Persephone’s underworld journey and dual existence.

- Hercules: From Hero to God. Examining Hercules’s legendary labors and deification.

Love Topics in the Essay about Greek Mythology

- Orpheus and Eurydice’s Tragedy. Analyzing their poignant tale of love, loss, and music.

- Aphrodite’s Influence. Exploring her role as the embodiment of love and beauty.

- Zeus’s Love Affairs. Investigating Zeus’s romantic escapades and their effects.

- Eros and Psyche’s Journey. Delving into their story of trust, betrayal, and love’s victory.

- Love and Desire in Myths. Discussing the portrayal and impact of love in Greek myths.

- Hades and Persephone’s Love. Analyzing their complex underworld relationship.

- Paris and Helen’s Romance. Examining their affair’s role in sparking the Trojan War.

- Pygmalion and Galatea’s Tale. Exploring the theme of transcendent artistic love.

- Alcestis and Admetus’s Sacrifice. Investigating the implications of Alcestis’s self-sacrifice.

- Apollo’s Unrequited Love for Daphne. Discussing unreciprocated love and transformation.

- Hercules and Deianira’s Tragic Love. Exploring their love story and its tragic conclusion.

- Jason and Medea’s Turmoil. Analyzing their intense, betrayal-marred relationship.

- Cupid and Psyche’s Resilience. Delving into the strength of their love.

- Baucis and Philemon’s Reward. Exploring their love’s reward by the gods.

- Achilles and Patroclus’s Bond. Discussing their deep connection and its wartime impact.

Readers also enjoyed

WHY WAIT? PLACE AN ORDER RIGHT NOW!

Just fill out the form, press the button, and have no worries!

We use cookies to give you the best experience possible. By continuing we’ll assume you board with our cookie policy.

The Traditional and Modern Myths Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

The biblical myth, myth as a metaphor, cultural identity, works cited.

The concept of mythology has preoccupied human life for many decades. Myths may refer to sacred narratives or stories that try to explain how human beings and other world phenomenon came into being as seen in their present form or state.

Although many scholars of mythology have used this terminology in many different ways, the fundamental element of myths is that they all tend to resemble stories with traditional origins.

The analysis of both traditional and modern mythology shows that the main myths are characterized by gods, fictional heroes and supernatural beings or powers all shaping the human mind. Myths have served to shape human kind through establishing models of behavior.

Through storytelling, individuals develop tendencies of retrogressing into the mythical past, thus drawing closer to the divine truths. This paper seeks to analyze the traditional and modern myths with a view to demonstrated similarities as well as differences. In the next phase of the discussion, the paper will enumerate the symbolic imperativeness of myths, and their influence to my perceptions about the world.

A private and unrecognized dream exists as a myth within the absence of an effective mythology. The Biblical conceptualizations of the origin of man provide an excellent form of a myth in the antiquity while the relatively new myth of the Superman offers the best illustration of a myth in the contemporary society. The representations of the origin of man from a religious standpoint offer me a unique opportunity to understand how humanity and its related facets came to be.

The Biblical story of the origin of man is perhaps the most upheld belief appealing to the universal conceptualization of humankind and its origin. Although religious dogmas and beliefs vary in a number of ways, there is a consensus about the origin and existence of humanity. The Superman myth portrayed by the comical superhero appeals to me because while as a kid, I believed in its existence and, in my dreams, wished to meet him.

According to the Bible, God created man after he had created the heavens and the earth. The book of Genesis takes us through the process that took God to create human beings and the world in general. We are later taken into the Garden of Eden where we are told that God placed Adam and Eve the supposed first human beings.

In the book of Genesis, we are told of the man who has to discover his origin and the origin of some fundamental elements of suffering and happiness as portrayed by the sinful nature of man and the potential redemption through salvation (New International Bible, Gen.2.1-2)

Like every other myth that has passed down through generations, the myth surrounding the origin of humankind in the Bible caries with it many inconsistencies. The order of creation in the Bible is broken and unexplained and uses unnatural means to achieve its goals. We are told, “Let there be light” ‘and there was light.”

The symbolic element of creating Adam and Eve as contrasted to declaring their being serves to demonstrated the innate significance of our existence as unique objects within the mythical realms. Therefore, through these representations, we come to appreciate the intrinsic importance of man in the universe. This draws from the elements of his creation as the last creature in order to watch over the rest of God’s creation.

The tales of the Bible try to explain common phenomenon, which remain unexplained in the contemporary world. According to Bible, the painfulness of child bearing is a punishment from God for defying his order not to eat from the fruit tree, which was at the centre of the Garden. One can conclude that this myth tries to explain why child bearing is so painful for women. However, in my view, it might seem unreasonable to justify the pains experienced by women due to sins committed by their ancestors.

To explain the conflict that exists between snakes and man, the Bible attributes this to God’s curse for man to toil in search for food. Man has never stopped seeking the explanations of metaphysical aspects such as death, beginning of life and many others. Humanity has always dreamt and remained committed of coming up with an answer through mythology and scientific discoveries and theory.

Renowned scientists like Charles Darwin have conducted numerous researches to explain and dispute the Bible’s theory of the origin of man. For instance, Charles Darwin concluded that man exists because of evolution process through change over a long period. Although this elementary theory may provide an insight into the question of origin, it may fail to offer best explanations surrounding the metaphysical world.

In trying to lend explanations to the origin of man, the most famous myths of the ancient Greek, myths of Oedipus, Odyssey, Zeus and many others may perhaps provide a substantial amount of light into the very question of existence. It is undisputed that myths form a very important part of our religions from Europe, Africa and all over the world.

Myths inform many aspects of our life, for example, many company names originate from Greek myths; very interesting though is the effect and influence that myths have on religions all over the world, for example, the Yoruba of Nigeria believe that their God originated from a reed.

Still in Africa, the Kikuyu, a tribe in Kenya, believed that their God came from mount Kirinyaga, which was his dwelling place. Explanations about the mythological formulations vary in approach and thought, thus serve to explain the conflicting nature of myths held by various traditions.

The Superman Myth. The comic character of Superman has come up as a strong mythological figure especially in the urban areas; it is common to hear kids saying, “That car is as fast as Superman.” to convince a seven year old kid that Superman does not exist may be a challenging task. It is attributed to numerous representation of the Superman through comic books and movies and in real life.

Siegel and Shuster created the first mythical characteristics of the Superman via images and symbols of rough and aggressive person renown for terrorizing criminals and gangsters especially in the 1920s.

No doubt exists in the fact that a similarity exist between the Bible, comic book hero, superman, and other myths.

In most cases myths provide perfect metaphors for applicable in real life situations. For example, the mythical Garden of Eden acts as a representation of aspects of life. Although this contradicts the Biblical essence, critics have commented that the Garden of Eden represents sexuality in human beings where the human body is represented as holy just like the Garden of Eden.

However, Adam and his wife go against this order and eat the fruit meaning that they slept together. Today, the story in the Bible provides a metaphorical account of human life the story of Cain and Abel’s sibling rivalry symbolizes the conflict that exists among humans, between racism to tribalism, the rich and the poor and many other differences that exist nowadays. (Genesis, 4.1-10).

On its part, the mythical hero superman represents a conflict between the law-abiding citizens and the criminals in the society or a war between the right and wrong.

Although held in separate ways, my choice of my myths conforms to the universal conception of most cultures around the world in a number of respects.

American culture is the one that is technologically advanced as more and more people tend to believe in science, a good example are many Hollywood movies which have been created predicting the end of this world due to a calamity arising out of a scientific experiment or the future based on scientific discovery. A new religion based on a science fiction, and science on the rise. In my view, this religion bases its roots in the recent technological and scientific discoveries as evidenced by the abundant literature.

The American society is a highly religious society where freedom of religion freely thrives. It is for this reason that many religions have their home in America. However, the Christianity has the highest following and for this reason, most Americans identify themselves with the theoretical stories in the Bible set at the Garden of Eden.

This analysis has adopted the comparative mythology in which two different myths have been compared on a number of aspects. The analysis of the concept o mythology in both traditional and modern perspectives reveals the attachment between humanity and the world. The link that manages to connect the world phenomena that remain unchallenged is filled by the formulations of myths. The concept of myth has evolved since pre-historical and Biblical times and that these elements have penetrated the modern society.

Studies have shown that the tendencies of traditions to get back to their traditional form of thinking have been facilitated through the creation of myth. Different traditions have held that myths are significant in shaping human behavior through drawing near to the divine nature of the ancient moments.

As indicated by Campbell in his book the “ Heroes Journey,” these myths follow the same pattern and form, thus form a platform for behavior change. Similarly, in the comic hero’s myths, superman lives in a perfect world in Krypton where he soon discovers that there are other Kryptonians living on the planet, when he comes to rescue them they are defeated and he is forced to remain on the earth where he experiences struggles but at the end, he triumphs.

The symbolic elements of myths remain instrumental in illustrating the meaning of some traditional and modern beliefs in order to inform their users. In demonstrating the essence of myths, the Superman serves as the critical example of how mythical components transform the mind and behavior through belief. Using this example, I have come to learn that characters and personality of most people are controlled by acceptance to subscribe to some particular myths.

Although a strong relationship exists between the traditional and modern conceptualizations of myths, these two groups of myths have vast differences and perhaps opposing features of each other. For instance, the 21 st century mythical representations attempt to reject the 19 th century mythical theories and science.

In this process of varying views, the modern mythology has developed a tendency to observe the traditional facets as obsolete and inconsequential to the development of the world’s ideologies. However, some studies document that different myths work in almost similar ways in order to achieve specific though different cultural and traditional goals. They argue that traditions are the regenerate functional subsets of the entire package of myths guiding the development of that given society.

Myths act to give meaning to life through transformations in modes of thinking toward the world into which our deities connect with the human beings. This element enables us to understand that the existence of things such as sufferings happen for a higher cause and reason.

Based on this significant element, the Biblical myth of the origin abd existence of man has enabled me to develop a general feeling that we are unique beings intended for better things in the world. This follows the punishments aspects of the Garden of Eden where our ancestors suffered because of their wickedness.

In addition, besides acting to inform our understanding, the two myths have offered themselves as lessons from which we model our behavior through taking the Superman and God as role models in our social and spiritual lives respectively. For instance, the Biblical story of the origin of man is perhaps the most upheld belief appealing to the universal conceptualization of humankind and its origin. Although religious dogmas and beliefs vary in a number of ways, there is a consensus about the origin and existence of humanity.

The Superman myth portrayed by the comical superhero appeals to me because while as a kid, I believed in its existence and, in my dreams, wished to meet him. On the other hand, myths have throughout history served to justify the cultural activities through the authoritative nature of mythical elements and characters. Man has never stopped seeking the explanations of metaphysical aspects such as death, beginning of life and many others.

Humanity has always dreamt and remained committed of coming up with an answer through mythology and scientific discoveries and theory. Through these aspects, myths attempt to establish events, customs, religious facets, laws, social and political structure, crafts and many recurring elements in the daily human life.

Myths represent the consensus of ideologies and cultural identity of varied traditions. There has been a general notion that some myths are outdated while others were current and able to address the phenomenal events happening in the world today. However, according to the evaluation of myths through a comparative study, analyses show that myths share some universal elements

Campbell, Joseph. The Hero with a Thousand Faces. Princeton: Princeton University Press,1949. Print.

Cousineau, Phil. The Hero’s Journey: Joseph Campbell on His Life and Work. Ed. Stuart L. Brown, New York: Harper and Row, 1990. Print.

Foley, Kevin D. African Oral Narrative Traditions: Teaching Oral Traditions. New York: Modern Language Association, 1998. Print.

New International Bible Version. London: Clays,1984. Print.

Rollo, May. The Cry For Myth . New York: Delta, 1992. Print.

Petrou, David M. The Making of Superman the Movie . New York: Warner Books,1978. Print.

- Mythology as a means to understand the Power Relations between Men and Women

- The Roman Creation Myth

- Mythology: The Garden of Eden Theory

- Jack London's Martin Eden in the Context of American Realism

- Utilitarianists’ Ideology in "Crime and Punishment" by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

- Achilles as a Classical Hero

- Mythological and Modern-Day Heroes

- Norse Cosmogony: “The Creation, Death, and Rebirth of the Universe” Summary

- The Circular Ruins

- Life of Nicias, Life of Crassus, Comparison of Crassus with Nicias

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2018, October 19). The Traditional and Modern Myths. https://ivypanda.com/essays/myth/

"The Traditional and Modern Myths." IvyPanda , 19 Oct. 2018, ivypanda.com/essays/myth/.

IvyPanda . (2018) 'The Traditional and Modern Myths'. 19 October.

IvyPanda . 2018. "The Traditional and Modern Myths." October 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/myth/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Traditional and Modern Myths." October 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/myth/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Traditional and Modern Myths." October 19, 2018. https://ivypanda.com/essays/myth/.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Plato’s Myths

What the ancient Greeks—at least in the archaic phase of their civilization—called muthos was quite different from what we and the media nowadays call “myth”. For them a muthos was a true story, a story that unveils the true origin of the world and human beings. For us a myth is something to be “debunked”: a widespread, popular belief that is in fact false. In archaic Greece the memorable was transmitted orally through poetry, which often relied on myth. However, starting with the beginning of the seventh century BC two types of discourse emerged that were set in opposition to poetry: history (as shaped by, most notably, Thucydides) and philosophy (as shaped by the peri phuseōs tradition of the sixth and fifth centuries BC). These two types of discourse were naturalistic alternatives to the poetic accounts of things. Plato broke to some extent from the philosophical tradition of the sixth and fifth centuries in that he uses both traditional myths and myths he invents and gives them some role to play in his philosophical endeavor. He thus seems to attempt to overcome the traditional opposition between muthos and logos .

There are many myths in Plato’s dialogues: traditional myths, which he sometimes modifies, as well as myths that he invents, although many of these contain mythical elements from various traditions. Plato is both a myth teller and a myth maker. In general, he uses myth to inculcate in his less philosophical readers noble beliefs and/or teach them various philosophical matters that may be too difficult for them to follow if expounded in a blunt, philosophical discourse. More and more scholars have argued in recent years that in Plato myth and philosophy are tightly bound together, in spite of his occasional claim that they are opposed modes of discourse.

1. Plato’s reading audience

2. plato’s myths, 3. myth as a means of persuasion, 4. myth as a teaching tool, 5. myth in the timaeus, 6. myth and philosophy, 7. plato’s myths in the platonist tradition, 8. renaissance illustrations of plato’s myths, anthologies of plato’s myths, short introductions to plato’s myths, articles and books on plato’s myths, plato’s myths in the platonist tradition, references cited, other internet resources, related entries.

For whom did Plato write? Who was his readership? A very good survey of this topic is Yunis 2007 from which I would like to quote the following illuminating passage: “before Plato, philosophers treated arcane subjects in technical treatises that had no appeal outside small circles of experts. These writings, ‘on nature’, ‘on truth’, ‘on being’ and so on, mostly in prose, some in verse, were demonstrative, not protreptic. Plato, on the other hand, broke away from the experts and sought to treat ethical problems of universal relevance and to make philosophy accessible to the public” (13). Other scholars, such as Morgan (2003), have also argued that Plato addressed in his writings both philosophical and non-philosophical audiences.

It is true that in the Republic Plato has the following advice for philosophers: “like someone who takes refuge under a little wall from a storm of dust or hail driven by the wind, the philosopher—seeing others filled with lawlessness—is satisfied if he can somehow lead his present life free from injustice and impious acts and depart from it with good hope, blameless and content” (496d–e) (unless otherwise noted, all quotations from Plato are from the translations included in Plato (1997)). He was certainly very bitter about Socrates’ fate. In his controversial interpretation Strauss (1964) argues that in Plato’s view the philosopher should stay disconnected from society. This interpretation is too extreme. Plato did not abandon Socrates’ credo, that the philosopher has a duty towards his fellow-citizens who do not devote their lives to philosophy. For him philosophy has a civic dimension. The one who makes it outside the cave should not forget about those who are still down there and believe that the shadows they see there are real beings. The philosopher should try to transmit his knowledge and his wisdom to the others, and he knows that he has a difficult mission. But Plato was not willing to go as far as Socrates did. He preferred to address the public at large through his written dialogues rather than conducting dialogues in the agora. He did not write abstruse philosophical treatises but engaging philosophical dialogues meant to appeal to a less philosophically inclined audience. The dialogues are, most of the time, prefaced by a sort of mise en scène in which the reader learns who the participants to the dialogue are, when, where and how they presently met, and what made them start their dialogue. The participants are historical and fictional characters. Whether historical or fictional, they meet in historical or plausible settings, and the prefatory mises en scène contain only some incidental anachronisms. Plato wanted his dialogues to look like genuine, spontaneous dialogues accurately preserved. How much of these stories and dialogues is fictional? It is hard to tell, but he surely invented a great deal of them. References to traditional myths and mythical characters occur throughout the dialogues. However, starting with the Protagoras and Gorgias , which are usually regarded as the last of his early writings, Plato begins to season his dialogues with self-contained, fantastical narratives that we usually label his ‘myths’. His myths are meant, among other things, to make philosophy more accessible.

There are in Plato identifiable traditional myths, such as the story of Gyges ( Republic 359d–360b), the myth of Phaethon ( Timaeus 22c7) or that of the Amazons ( Laws 804e4). Sometimes he modifies them, to a greater or lesser extent, while other times he combines them—this is the case, for instance, of the Noble Lie ( Republic 414b–415d), which is a combination of the Cadmeian myth of autochthony and the Hesiodic myth of ages. There are also in Plato myths that are his own, such as the myth of Er ( Republic 621b8) or the myth of Atlantis ( Timaeus 26e4). Many of the myths Plato invented feature characters and motifs taken from traditional mythology (such as the Isles of the Blessed or the judgment after death), and sometimes it is difficult to distinguish his own mythological motifs from the traditional ones. The majority of the myths he invents preface or follow a philosophical argument: the Gorgias myth (523a–527a), the myth of the androgyne ( Symposium 189d–193d), the Phaedo myth (107c–115a), the myth of Er ( Republic 614a–621d), the myth of the winged soul ( Phaedrus 246a–249d), the myth of Theuth ( Phaedrus 274c–275e), the cosmological myth of the Statesman (268–274e), the Atlantis myth ( Timaeus 21e–26d, Critias ), the Laws myth (903b–905b).

Plato refers sometimes to the myths he uses, whether traditional or his own, as muthoi (for an overview of all the loci where the word muthos occurs in Plato see Brisson 1998 (141ff.)). However, muthos is not an exclusive label. For instance: the myth of Theuth in the Phaedrus (274c1) is called an akoē (a “thing heard”, “report”, “story”); the myth of Cronus is called a phēmē (“oracle”, “tradition”, “rumour”) in the Laws (713c2) and a muthos in the Statesman (272d5, 274e1, 275b1); and the myth of Boreas at the beginning of the Phaedrus is called both muthologēma (229c5) and logos (d2).

The myths Plato invents, as well as the traditional myths he uses, are narratives that are non-falsifiable, for they depict particular beings, deeds, places or events that are beyond our experience: the gods, the daemons, the heroes, the life of soul after death, the distant past, etc. Myths are also fantastical, but they are not inherently irrational and they are not targeted at the irrational parts of the soul. Kahn (1996, 66–7) argues that between Plato’s “otherworldly vision” and “the values of Greek society in the fifth and fourth centuries BC” was a “radical discrepancy”. In that society, Plato’s metaphysical vision seemed “almost grotesquely out of place”. This discrepancy, claims Kahn, “is one explanation for Plato’s use of myth: myth provides the necessary literary distancing that permits Plato to articulate his out–of–place vision of meaning and truth.”

The discussion of the Symposium ends with Aristophanes and Agathon falling asleep while Socrates is trying to prove that “the skilful tragic dramatist should also be a comic poet” (223d). Plato himself seems to be such an author, as some of his dialogues read like tragedies (e.g. the Phaedo ), while others mix arguments with irony and humour (e.g. the Euthydemus , Lesser Hippias , or Ion ). For the link between drama and philosophy in Plato’s dialogues see Puchner (2010), Folch (2015), Zimmermann (2018), and Fossheim, Songe-Møller and Ågotnes (2019); for the importance of comedy and laughter in the dialogues see Tanner (2017) and Naas (2018b); and for the theory and practice of narrative in Plato see Halliwell (2009). And now to go back to Kahn’s claim (see the above paragraph) that in Plato “myth provides the necessary literary distancing that permits Plato to articulate his out–of–place vision of meaning and truth.” This may well be the case. But we have to keep in mind that Plato’s dialogues are a mix of various literary genres (philosophy, comedy, tragedy, poetry, mythology, rhetoric), and that this mix is also (to use Kahn’s expression) out-of-place. In other words, both the content and the form of Plato’s dialogues were, and still are, rather extraordinary—and that, I reckon, was meant to free his readers from conventions and encourage them to think for themselves about the issues that, he, Plato, discusses in his dialogues.

The Cave, the narrative that occurs in the Republic (514a–517a), is a fantastical story, but it does not deal explicitly with the beyond (the distant past, life after death etc.), and is thus different from the traditional myths Plato uses and the myths he invents. Strictly speaking, the Cave is an analogy, not a myth. Also in the Republic , Socrates says that until philosophers take control of a city “the politeia whose story we are telling in words ( muthologein ) will not achieve its fulfillment in practice” (501e2–5; translated by Rowe (1999, 268)). The construction of the ideal city may be called a “myth” in the sense that it depicts an imaginary polis (cf. 420c2: “We imagine the happy state”). In the Phaedrus (237a9, 241e8) the word muthos is used to name “the rhetorical exercise which Socrates carries out” (Brisson 1998, 144), but this seems to be a loose usage of the word.

Most (2012) argues that there are eight main features of the Platonic myth. (a) Myths are a monologue, which those listening do not interrupt; (b) they are told by an older speaker to younger listeners; (c) they “go back to older, explicitly indicated or implied, real or fictional oral sources” (17); (d) they cannot be empirically verified; (e) their authority derive from tradition, and “for this reason they are not subject to rational examination by the audience” (18); (f) they have a psychologic effect: pleasure, or a motivating impulse to perform an action “capable of surpassing any form of rational persuasion” (18); (g) they are descriptive or narrative; (h) they precede or follow a dialectical exposition. Most acknowledges that these eight features are not completely uncontroversial, and that there are occasional exceptions; but applied flexibly, they allow us to establish a corpus of at least fourteen Platonic myths in the Phaedo , Gorgias , Protagoras , Meno , Phaedrus , Symposium , Republic X, Statesman , Timaeus , Critias and Laws IV. The first seven features “are thoroughly typical of the traditional myths which were found in the oral culture of ancient Greece and which Plato himself often describes and indeed vigorously criticizes” (19).

Dorion (2012) argues that the Oracle story in Plato’s Apology has all these eight features of the Platonic myth discussed by Most (2012). Dorion concludes that the Oracle story is not only a Platonic fiction, but also a Platonic myth, more specifically: a myth of origin. Who invented the examination of the opinions of others by the means of elenchus ? Aristotle (see Sophistical Refutations 172a30–35 and Rhetoric 1354a3–7) thought that the practice of refutation is, as Dorion puts it, “lost in the mists of time and that it is hence vain to seek an exact origin of it” (433). Plato, however, attempts to convince us that the dialectical elenchus “were a form of argumentation that Socrates began to practice spontaneously as soon as he learned of the Oracle” (433); thus, Plato confers to it a divine origin; in the Charmides he does the same when he makes Socrates say that he learned an incantation (a metaphor for the elenchus ) from Zalmoxis; see also the Philebus 16c (on Socrates mythologikos see also Miller (2011)).

We have a comprehensive book about the people of Plato: Nails (2002); now we also have one about the animals of Plato: Bell and Naas (2015). Anyone interested in myth, metaphor, and on how people and animals are intertwined in Plato would be rewarded by consulting it. Here is a quotation from the editors’ introduction, “Plato’s Menagerie”:

Animal images, examples, analogies, myths, or fables are used in almost every one of Plato’s dialogues to help characterize, delimit, and define many of the dialogues’ most important figures and themes. They are used to portray not just Socrates [compared to a gadfly, horse, swan, snake, stork, fawn, and torpedo ray] but many other characters in the dialogues, from the wolfish Thrasymachus of the Republic to the venerable racehorse Parmenides of the Parmenides . Even more, animals are used throughout the dialogues to develop some of Plato’s most important political or philosophical ideas. […] By our reckoning, there is but a single dialogue (the Crito ) that does not contain any obvious reference to animals, while most dialogues have many. What is more, throughout Plato’s dialogues the activity or enterprise of philosophy itself is often compared to a hunt, where the interlocutors are the hunters and the object of the dialogue’s search—ideas of justice, beauty, courage, piety, or friendship—their elusive animal prey. (Bell and Naas 2015, 1–2)

For Plato we should live according to what reason is able to deduce from what we regard as reliable evidence. This is what real philosophers, like Socrates, do. But the non-philosophers are reluctant to ground their lives on logic and arguments. They have to be persuaded. One means of persuasion is myth. Myth inculcates beliefs. It is efficient in making the less philosophically inclined, as well as children (cf. Republic 377a ff.), believe noble things.

In the Republic the Noble Lie is supposed to make the citizens of Callipolis care more for their city. Schofield (2009) argues that the guards, having to do philosophy from their youth, may eventually find philosophizing “more attractive than doing their patriotic duty” (115). Philosophy, claims Schofield, provides the guards with knowledge, not with love and devotion for their city. The Noble Lie is supposed to engender in them devotion for their city and instill in them the belief that they should “invest their best energies into promoting what they judge to be the city’s best interests” (113). The preambles to a number of laws in the Laws that are meant to be taken as exhortations to the laws in question and that contain elements of traditional mythology (see 790c3, 812a2, 841c6) may also be taken as “noble lies”.

The following myths are eschatological: Gorgias 523a–527a, Meno 81a–d, Phaedo 107c–115a, Phaedrus 246a–257a, Republic 614b–621d, and Laws 903b–905d. The stories they tell differ—to a greater or lesser extent—although some themes occur in more than one of them: the judgement of souls for their earthly life, their subsequent punishment or reward, the contemplation of forms in the other world, and reincarnation (which, in the Phaedo 81d–e, is part of the soul’s punishment or reward; see also the Timaeus 42c–e and 90e–92c). These are Plato’s myths, but they feature many elements and deities of classical mythology (such as Zeus, Prometheus, Hestia, Necessity and the Fates). For good surveys of Plato’s eschatological myths see Annas (1982) and Inwood (2009); see also the entries on myth and eschatology in Press and Duque (2022). For the relationship between philosophy and religion in Plato see Nightingale (2021). O’Meara (2017, 114) argues that the Timaeus and the Statesman are “reformed Panathenaic” festivals—in which Zeus ( Timaeus ) and Athena ( Statesman ) are “reformed”—while the Laws is a “reformed Dionysian festival” (in which Dionysus is “reformed”).

Plato’s eschatological myths are not complete lies. There is some truth in them. In the Phaedo the statement “The soul is immortal” is presented as following logically from various premises Socrates and his interlocutors consider acceptable (cf. 106b–107a). After the final argument for immortality (102a–107b), Cebes admits that he has no further objections to, nor doubts about, Socrates’ arguments. But Simmias confesses that he still retains some doubt (107a–b), and then Socrates tells them an eschatological myth. The myth does not provide evidence that the soul is immortal. It assumes that the soul is immortal and so it may be said that it is not entirely false. The myth also claims that there is justice in the afterlife and Socrates hopes that the myth will convince one to believe that the soul is immortal and that there is justice in the afterlife. “I think”, says Socrates, that “it is fitting for a man to risk the belief—for the risk is a noble one—that this, or something like this, is true about our souls and their dwelling places” (114d–e). (Edmonds (2004) offers a interesting analysis of the final myth of Phaedo , Aristophanes’ Frogs and the funerary gold leaves, or “tablets”, that have been found in Greek tombs). At the end of the myth of Er (the eschatological myth of the Republic ) Socrates says that the myth “would save us, if we were persuaded by it” (621b). Myth represents a sort of back-up: if one fails to be persuaded by arguments to change one’s life, one may still be persuaded by a good myth. Myth, as it is claimed in the Laws , may be needed to “charm” one “into agreement” (903b) when philosophy fails to do so.

Sedley (2009) argues that the eschatological myth of the Gorgias is best taken as an allegory of “moral malaise and reform in our present life” (68) and Halliwell (2007) that the myth of Er may be read as an allegory of life in this world. Gonzales (2012) claims that the myth of Er offers a “spectacle [that] is, in the words of the myth itself, pitiful, comic and bewildering” (259). Thus, he argues, “what generally characterizes human life according to the myth is a fundamental opacity ” (272); which means that the myth is not actually a dramatization of the philosophical reasoning that unfolds in the Republic , as one might have expected, but of everything that “such reasoning cannot penetrate and master, everything that stubbornly remains dark and irrational: embodiment, chance, character, carelessness, and forgetfulness, as well as the inherent complexity and diversity of the factors that define a life and that must be balanced in order to achieve a good life” (272). The myth blurs the boundary between this world and the other. To believe that soul is immortal and that we should practice justice in all circumstances, Gonzales argues, we have to be persuaded by what Socrates says, not by the myth of Er. Unlike the eschatological myths of the Gorgias and Phaedo , the final myth of the Republic illustrates rather “everything in this world that opposes the realization of the philosophical ideal. If the other myths offer the philosopher a form of escapism, the myth of Er is his nightmare” (277, n. 36).

The philosopher should share his philosophy with others. But since others may sometimes not follow his arguments, Plato is ready to provide whatever it takes—an image, a simile, or a myth—that will help them grasp what the argument failed to tell them. The myth—just like an image, or analogy—may be a good teaching tool. Myth can embody in its narrative an abstract philosophical doctrine. In the Phaedo , Plato develops the so-called theory of recollection (72e–78b). The theory is there expounded in rather abstract terms. The eschatological myth of the Phaedo depicts the fate of souls in the other world, but it does not “dramatize” the theory of recollection. The Phaedrus myth of the winged soul, however, does. In it we are told how the soul travels in the heavens before reincarnation, attempts to gaze on true reality, forgets what it saw in the heavens once reincarnated, and then recalls the eternal forms it saw in the heavens when looking at their perceptible embodiments. The Phaedrus myth does not provide any proofs or evidence to support the theory of recollection. It simply assumes this theory to be true and provides (among other things) an “adaptation” of it. Since this theory the myth embodies is, for Plato, true, the myth has (pace Plato) a measure of truth in it, although its many fantastical details may lead one astray if taken literally. Among other things, the fantastical narrative of the myth helps the less philosophically inclined grasp the main point of Plato’s theory of recollection, namely that “knowledge is recollection”.

The cosmology of the Timaeus is a complex and ample construction, involving a divine maker (assisted by a group of less powerful gods), who creates the cosmos out of a given material (dominated by an inner impulse towards disorder) and according to an intelligible model. The cosmology as a whole is called both an eikōs muthos (29d, 59c, 68d) and an eikōs logos (30b, 48d, 53d, 55d, 56a, 57d, 90e). The expression eikōs muthos has been translated as ‘probable tale’ (Jowett), ‘likely story’ (Cornford), ‘likely tale’ (Zeyl). The standard interpretation is promoted by, among others, Cornford (1937, 31ff.). The Timaeus cosmology, Cornford argues, is a muthos because it is cast in the form of a narration, not as a piece-by-piece analysis. But also, and mainly, because its object, namely the universe, is always in a process of becoming and cannot be really known. Brisson (1998, ch. 13) offers a different solution, but along the same lines. The cosmology, Brisson argues, is a non-verifiable discourse about the perceptible universe before and during its creation. In other words: the cosmology is an eikōs muthos because it is about what happens to an eikōn before, and during, its creation, when everything is so fluid that it cannot be really known. The standard alternative is to say that the problem lies in the cosmologist, not in the object of his cosmology. It is not that the universe is so unstable so that it cannot be really known. It is that we fail to provide an exact and consistent description of it. A proponent of this view is Taylor (1928, 59). Rowe (2003) has argued that the emphasis at 29d2 is on the word eikōs , not muthos , and that here muthos is used primarily as a substitute for logos without its typical opposition to that term (a view also held by Vlastos (1939, 380–3)). Burnyeat (2009) argues that this cosmology is an attempt to disclose the rationality of the cosmos, namely the Demiurge’s reasons for making it thus and so. The word eikōs (a participial form of the verb eoika , “to be like”) is, argues Burnyeat, usually translated as “probable”; but—as textual evidence from Homer to Plato proves—it also means “appropriate”, “fitting”, “fair”, “natural”, “reasonable”. Since the cosmology reveals what is reasonable in the eikōn made by the Demiurge, it may rightly be called eikōs , “reasonable”. The Demiurge’s reasoning, however, is practical, not theoretical. The Demiurge, Burnyeat claims, works with given materials, and when he creates the cosmos, he does not have a free choice, but has to adjust his plans to them. Although we know that the Demiurge is supremely benevolent towards his creation, none of us could be certain of his practical reasons for framing the cosmos the way he did. That is why anyone aiming at disclosing them cannot but come up with “probable” answers. Plato’s cosmology is then eikōs in the two senses of the word, for it is both “reasonable” and “probable”. But why does Plato call it a muthos ? Because, Burnyeat argues, the Timaeus cosmology is also a theogony (for the created cosmos is for Plato a god), and this shows Plato’s intention to overcome the traditional opposition between muthos and logos .

Timaeus speaks about the Demiurge’s practical reasoning for creating the cosmos as he did. No cosmologist can deduce these reasons from various premises commonly accepted. He has to imagine them, but they are neither fantastical, nor sophistic. The cosmologist exercises his imagination under some constraints. He has to come up with reasonable and coherent conjectures. And in good Socratic and Platonic tradition, he has to test them with others. This is what Timaeus does. He expounds his cosmology in front of other philosophers, whom he calls kritai , “judges” (29d1). They are highly skilled and experienced philosophers: Socrates, Critias and Hermocrates and at the beginning of the Critias , the sequel to the Timaeus , they express their admiration for Timaeus’ cosmological account (107a). One may say that Timaeus’ account has been peer-reviewed. The judges, however, says Plato, have to be tolerant, for in this field one cannot provide more than conjectures. Timaeus’ cosmological discourse is not aimed at persuading a less philosophically inclined audience to change their lives. It may be argued that its creationist scenario was meant to make the difficult topic of the genesis of the realm of becoming more accessible. In the Philebus , in a tight dialectical conversation, the genesis of the realm of becoming is explained in abstract terms (the unlimited, limit, being that is mixed and generated out of those two; and the cause of this mixture and generation, 27b–c). But the Timaeus aims at encompassing more than the Philebus . It aims not only at revealing the ultimate ontological principles (accessible to human reason, cf. 53d), and at explaining how their interaction brings forth the world of becoming, but also at disclosing, within a teleological framework, the reasons for which the cosmos was created the way it is. These reasons are to be imagined because imagination has to fill in the gaps that reason leaves in this attempt to disclose the reasons for which the cosmos was created the way it is.

In the Protagoras (324d) a distinction is made between muthos and logos , where muthos appears to refer to a story and logos to an argument. This distinction seems to be echoed in the Theaetetus and the Sophist. In the Theaetetus Socrates discusses Protagoras’ main doctrine and refers to it as “the muthos of Protagoras” (164d9) (in the same line Socrates also calls Theaetetus’ defence of the identity of knowledge and perception a muthos ). And later on, at 156c4, Socrates calls a muthos the teaching according to which active and passive motions generate perception and perceived objects. In the Sophist , the Visitor from Elea tells his interlocutors that Xenophanes, Parmenides and other Eleatic, Ionian (Heraclitus included) and Sicilian philosophers “appear to me to tell us a myth, as if we were children” (242c8; see also c–e). By calling all those philosophical doctrines muthoi Plato does not claim that they are myths proper, but that they are, or appear to be, non-argumentative. In the Republic Plato is fairly hostile to particular traditional myths (but he claims that there are two kinds of logoi , one true and the other false, and that the muthoi we tell children “are false, on the whole, though they have some truth in them”, 377a; for a discussion of allegory and myth in Plato’s Republic see Lear (2006)). Halliwell (2011) claims that Book X of the Republic “offers not a simple repudiation of the best poets but a complicated counterpoint in which resistance and attraction to their work are intertwined, a counterpoint which (among other things) explores the problem of whether, and in what sense, it might be possible to be a ‘philosophical lover’ of poetry” (244). For an illuminating article on the Republic and the Odyssey see Segal (1978); see also Howland (2006).

In many dialogues he condemns the use of images in knowing things and claims that true philosophical knowledge should avoid images. He would have had strong reasons for avoiding the use of myths: they are not argumentative and they are extremely visual (especially those he invented, which contain so many visual details as if he would have given instructions to an illustrator). But he didn’t. He wanted to persuade and/or teach a wider audience, so he had to make a compromise. Sometimes, however, he seems to interweave philosophy with myth to a degree that was not required by persuading and/or teaching a non-philosophical audience. The eschatological myths of the Gorgias , Phaedo and Republic , for instance, are tightly bound with the philosophical arguments of those dialogues (cf. Annas 1982); and the eschatological myth of the Phaedo “picks one by one the programmatic remarks about teleological science from earlier on in the dialogue, and sketches ways in which their proposals can be fulfilled” (Sedley 1990, 381). Some other times he uses myth as a supplement to philosophical discourse (cf. Kahn (2009) who argues that in the myth of the Statesman Plato makes a doctrinal contribution to his political philosophy; Naas (2018a, Chapter 2) offers an interesting interpretation of this myth, and (Chapter 3) discusses Michel Foucault’s reading of it. A number of chapters in Sallis (2017) and in Bossi and Robinson (2018) reassess the myth of the Statesman . One time, in the Timaeus , Plato appears to overcome the opposition between muthos and logos : human reason has limits, and when it reaches them it has to rely on myth (arguably, that also happen in the Symposium ; for a very close reading of how Diotima’s speech interacts with Aristophanes’ myth of the androgyne see Hyland (2015).

“On the less radical version, the idea will be that the telling of stories is a necessary adjunct to, or extension of, philosophical argument, one which recognizes our human limitations, and—perhaps—the fact that our natures combine irrational elements with the rational” (Rowe 1999, 265). On a more radical interpretation, “the distinction between ‘the philosophical’ and ‘the mythical’ will—at one level—virtually disappear” (265). If we take into account that Plato chose to express his thoughts through a narrative form, namely that of the dialogue (further enveloped in fictional mises en scène ), we may say that the “use of a fictional narrative form (the dialogue) will mean that any conclusions reached, by whatever method (including ‘rational argument’), may themselves be treated as having the status of a kind of ‘myth’” (265). If so, “a sense of the ‘fictionality’ of human utterance, as provisional, inadequate, and at best approximating to the truth, will infect Platonic writing at its deepest level, below other and more ordinary applications of the distinction between mythical and nonmythical forms of discourse” (265); if so, it is not only “that ‘myth’ will fill in the gaps that reason leaves (though it might do that too, as well as serving special purposes for particular audiences), but that human reason itself ineradicably displays some of the features we characteristically associate with story-telling” (265–6) (cf. also Fowler (2011, 64): “Just as the immortal, purely rational soul is tainted by the irrational body, so logos is tainted by mythos ”). It is difficult to say which one of these two readings is a better approximation of what Plato thought about the interplay between myth and philosophy. The interpreter seems bound to furnish only probable accounts about this matter.

Fowler (2011) surveys the muthos–logos dichotomy from Herodotus and the pre–Socratic philosophers to Plato, the Sophists, and the Hellenistic and Imperial writers, and provides many valuable references to works dealing with the notion of muthos , the Archaic uses of myth– words, and ancient Greek mythology; see also Wians (2009). For the muthos–logos dichotomy in Plato see also Miller (2011, 76–77).

Aristotle admits that the lover of myths is in a sense a lover of wisdom ( Metaphysics 982b18; cf. also 995a4 and 1074b1–10). He might have used a myth or two in his early dialogues, now lost. But in general he seems to have distanced himself from myth (cf. Metaphysics 1000a18–9).

On the philosophical use of myth before Plato there are a number of good studies, notably Morgan 2000. There is, however, little on the philosophical use of myth in the Platonist tradition. Of Plato’s immediate successors in the Academy, Speusippus, Xenocrates and Heraclides of Pontus composed both dialogues and philosophical treatises. But, with one exception, none of these seems to have used myths as Plato did. The exception is Heraclides, who wrote various dialogues—such as On the Things in Hades , Zoroastres and Abaris —involving mythical stories and mythical, or semi-mythical, figures. In the later Platonist tradition—with the exception of Cicero and Plutarch—there is not much evidence that Plato’s philosophical use of myths was an accepted practice. In the Neoplatonic tradition various Platonic myths became the subject of elaborate allegorization. Porphyry, Proclus, Damascius and Olympiodorus gave allegorical interpretations of a number of Platonic myths, such as the Phaedo and Gorgias eschatological myths, or the myth of Atlantis.

For the influence of Plato’s myths on various thinkers (Bacon, Leibniz, the German Idealists, Cassirer and others) see Keum (2020).

Plato was a celebrated figure in the Renaissance but only a few illustrations of Platonic mythical motifs can be found. Perhaps Plato’s attitude to visual representation—claiming so often that the highest philosophical knowledge is devoid of it, and attacking poets and artists in general more than once—inhibited and discouraged attempts to capture in painting, sculpture or prints, the mythical scenes Plato himself depicted so vividly in words. Perhaps artists simply felt themselves unequal to the task. McGrath (2009) reviews and analyzes the rare illustrations of Platonic mythical figures and landscapes in Renaissance iconography: the androgyne of the Symposium , the charioteer of the Phaedrus , the Cave , and the spindle of the universe handled by Necessity and the Fates of the Republic .

- Partenie, C. (ed.), 2004, Plato. Selected Myths , Oxford: Oxford University Press. Reissued 2009; Kindle edition 2012.

- Stewart, J. A., 1905, The Myths of Plato , translated with introductory and other observations, London & New York: Macmillan. 2 nd edition, London: Centaurus Press, 1960. 3 rd edition, New York: Barnes and Noble, 1970.

- Most, G. W., 2012, “Plato’s Exoteric Myths”, in C. Collobert, P. Destrée and F. J. Gonzales (eds.), Plato and Myth. Studies on the Use and Status of Platonic Myths ( Mnemosyne Supplements, 337), Leiden-Boston: Brill, 13–24.

- Murray, P., 1999, “What Is a Muthos for Plato?”, in R. Buxton (ed.), From Myth to Reason? Studies in the Development of Greek Thought , Oxford: Oxford University Press, 251–262.

- Partenie, C., L. Brisson, and J. Dillon, 2004, “Introduction”, in C. Partenie (ed.), Plato. Selected Myths , Oxford: Oxford University Press, xiii–xxx. Reissued 2009; Kindle edition 2012.

- Partenie, C., 2009, “Introduction”, in C. Partenie (ed.), Plato’s Myths , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1–27. Reprinted 2011.

- Annas, J., 1982, “Plato’s Myths of Judgement”, Phronesis , 27: 119–43.

- Brisson, L., 1998, Plato the Myth Maker [ Platon, les mots et les mythes ], translated, edited, and with an introduction by Gerard Naddaf, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- A. Capra, A., 2017, “Seeing through Plato’s Looking Glass. Mythos and Mimesis from Republic to Poetics ”, Aisthesis 1(1): 75–86.

- Collobert, C., Destrée, P., Gonzales, F. J. (eds.), 2012, Plato and Myth. Studies on the Use and Status of Platonic Myths ( Mnemosyne Supplements, 337), Leiden-Boston: Brill.

- Edmonds, III, R. G., 2004, Myths of the Underworld Journey. Plato, Aristophanes and the “Orphic” Gold Tablets , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fowler, R., 2011, “ Mythos and logos ”, Journal of Hellenic Studies , 131: 45–66.

- Frutiger, P., 1976, Les Mythes de Platon , New York: Arno Press. Originally published in 1930.

- Gill, Ch., 1993, “Plato on Falsehood—Not Fiction”, in Ch. Gill and T. P. Wiseman (eds.), Lies and Fiction in the Ancient World , Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 38–87.

- Griswold Jr., C. J., 1996, “Excursus: Myth in the Phaedrus and the Unity of the Dialogue”, in Self-Knowledge in Plato’s Phaedrus, University Park: Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 138–156.

- Howland, J., 2006. “The Mythology of Philosophy: Plato’s Republic and the Odyssey of the Soul”, Interpretation. A Journal of Political Philosophy , 33 (3): 219–242.

- Hyland, D., 2015, “The Animals That Therefore We Were? Aristophanes’s Double–Creatures and the Question of Origins”, in J. Bell, J. & M. Naas (eds.), Plato’s Animals: Gadflies, Horses, Swans, and Other Philosophical Beasts , Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 193–205.

- Janka, M., and Schäfer, C. (eds.), 2002, Platon als Mythologe. Neue Interpretationen zu den Mythen in Platons Dialogen , Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Lear, J., 2006, “Allegory and Myth in Plato’s Republic ”, in G. Santas (ed.), The Blackwell Guide to Plato’s Republic, Malden, MA: Blackwell, 25–43.

- Mattéi, J.F., 2002, Platon et le miroir du mythe: De l’âge d’or à l’Atlantide , Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- Mattéi, J.F., 1988, “The Theatre of Myth in Plato”, in C. J. Griswold Jr., (ed.), Platonic Writings, Platonic Readings , University Park: Pennsylvania: Penn State University Press, 66–83.

- Morgan, K., 2000, Myth and Philosophy from the pre-Socratics to Plato , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Naddaf, G., 2016, “Poetic Myths of the Afterlife: Plato’s Last Song”, in Rick Benitez and Keping Wang (eds.), Refelections on Plato’s Poetics , Berrima: Academic Printing and Publishing, 111–136.

- Partenie, C. (ed.), 2009, Plato’s Myths , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Reprinted 2011.

- Pieper, J., 2011, The Platonic Myths , with an introduction by James V. Schall, translated from the German by Dan Farrelly, South Bend, IN: St. Augustine’s Press. Originally published in 1965.

- Saunders, T.J., 1973, “Penology and Eschatology in Plato’s Timaeus and Laws ”, Classical Quarterly , n.s. 23(2): 232–44.

- Sedley, D., 1990, “Teleology and Myth in the Phaedo ”, Proceedings of the Boston Area Colloquium in Ancient Philosophy , 5: 359–83.

- Segal, C., 1978, “‘The Myth Was Saved’: Reflections on Homer and the Mythology of Plato’s Republic ”, Hermes 106 (2): 315–336.

- Werner, D., 2012, Myth and Philosophy in Plato’s Phaedrus, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- White, D. A., 2012, Myth, Metaphysics and Dialectic in Plato’s Statesman, Hampshire & Burlington: Ashgate.

- Wians, W. (ed.), Logos and Muthos. Philosophical Essays in Greek Literature , New York: SUNY Press.

- Dillon, John, 2004, “Plato’s Myths in the Later Platonist Tradition”, in C. Partenie (ed.), Plato. Selected Myths , Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. xxvi–xxx. Reissued 2009; Kindle edition 2012.

- Brisson, L., 2004, How Philosophers Saved Myths: Allegorical Interpretation and Classical Mythology [ Introduction à la philosophie du mythe, vol. I: Sauver les mythes ], Catherine Tihanyi (tr.), Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Renaissance illustrations of Plato’s myths

- Chastel, A., 1959, Art et humanisme à Florence au temps de Laurent le Magnifique , Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

- McGrath, E., 1983. “‘The Drunken Alcibiades’: Rubens’s Picture of Plato’s Symposium ”, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes , 46: 228–35.

- McGrath, E., 1994, “From Parnassus to Careggi. A Florentine Celebration of Renaissance Platonism”, in J. Onians (ed.), Sight and Insight: Essays on Art and Culture in Honour of E. H. Gombrich at 85 , London: Phaidon, 190–220.

- McGrath, E., 2009, “Platonic myths in Renaissance iconography”, in C. Partenie (ed.), Plato’s Myths , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 206–238.

- Vinken, P.J., 1960, “H.L. Spiegel’s Antrum Platonicum. A Contribution to the Iconology of the Heart”, Oud Holland , 75: 125–42.

- Allen, R.E. (ed.), 1965, Studies in Plato’s Metaphysics , London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Bell, J., Naas, M. (eds.), 2015, Plato’s Animals: Gadflies, Horses, Swans, and Other Philosophical Beasts , Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Bossi, B., and Robinson, T. M. (eds), 2018, Plato’s Statesman Revisited , Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter.

- Buxton, R. (ed.), 1999, From Myth to Reason? Studies in the Development of Greek Thought , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Burnyeat, M. F., 2009, “ Eikōs muthos ”, in C. Partenie (ed.), Plato’s Myths , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 167–186.

- Cornford, F.M., 1937, Plato’s Cosmology: The Timaeus of Plato , translated with a running commentary, London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Dorion, L.-A., 2012, “The Delphic Oracle on Socrates’ Wisdom: A Myth?”, in C. Collobert, P. Destrée and F. J. Gonzales (eds.), Plato and Myth. Studies on the Use and Status of Platonic Myths ( Mnemosyne Supplements, 337), Leiden-Boston: Brill, 419–434.

- Edmonds, III, R. G., 2004, Myths of the Underworld Journey. Plato, Aristophanes, and the “Orphic” Gold Tablets , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ferrari, G. R. F. (ed.), 2007, The Cambridge Companion to Plato’s Republic, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Folch, M., 2015, The City and the Stage: Performance, Genre, and Gender in Plato’s Laws, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fossheim, H., Songe-Møller, V., and Ågotnes, K. (eds.), 2019, Philosophy as Drama. Plato’s Thinking Through Dialogue , London and New York: Bloomsbury.

- Gonzalez, F. J., 2012, “Combating Oblivion: The Myth of Er as Both Philosophy’s Challenge and Inspiration”, in C. Collobert, P. Destrée and F. J. Gonzales (eds.), Plato and Myth. Studies on the Use and Status of Platonic Myths ( Mnemosyne Supplements, 337), Leiden-Boston: Brill, 259–278.

- Halliwell, S., 2007, “The Life-and-Death Journey of the Soul: Interpreting the Myth of Er”, in G. R. F. Ferrari (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Plato’s Republic, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 445–473.

- Halliwell, S., 2009, “The Theory and Practice of Narrative in Plato”, in Jonas Grethlein and Antonios Rengakos (eds.), Narratology and Interpretation. The Content of Narrative Form in Ancient Literature , Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, 15–42.

- Halliwell, S., 2011, “Antidotes and Incantations: Is There are a Cure for Poetry in Plato’s Republic ”, in P. Destrée and F.-G. Herrmann (eds.), Plato and the Poets ( Mnemosyne Supplements, 328), Leiden-Boston: Brill, 241–266.

- Inwood, M., 2009, “Plato’s eschatological myths”, in Catalin Partenie (ed.), Plato’s Myths , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 28–50.

- Kahn, C., 2009, “The myth of the Statesman ”, in C. Partenie (ed.), Plato’s Myths , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 148–166.

- Kahn, Ch., 1996, Plato and the Socratic Dialogue. The Philosophical Use of a Literary Form , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Keum, T.-Y., 2020, Plato and the Mythic Tradition in Political Thought , Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Miller, F. D., 2011, “Socrates Mythologikos ”, in G. Anagnostopoulos (ed.), Socratic, Platonic and Aristotelian Studies: Essays in Honor of Gerasimos Santas , Dordrecht: Springer, 75–92.

- Morgan, K, 2000, Myth and Philosophy from the pre-Socratics to Plato , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Morgan, K., 2003, “The Tyranny of the Audience in Plato and Isocrates”, in K. Morgan (ed.), Popular Tyranny: Sovereignty and Its Discontents in Ancient Greece , Austin: University of Texas Press, 181–213.

- Naas, M., 2018a, Plato and the Invention of Life , New York: Fordham University Press.

- Naas, M., 2018b, “Plato and the Spectacle of Laughter”, in Russell Ford (ed.), Why So Serious: On Philosophy and Comedy , London: Routledge, 13–26.

- Nails, D. 2002, The People of Plato: A Prosopography of Plato and Other Socratics , Indianapolis and Cambridge: Hackett Publishing.

- Natali, C. and Maso, S. (eds.), 2003, Plato Physicus: Cosmologia e antropologia nel Timeo , Amsterdam: Adolf Hakkert.

- Nightingale, A., 2021, Philosophy and Religion in Plato’s Dialogues , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- O’Meara, D. J., 2017, Cosmology and Politics in Plato’s Later Works , Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Plato, 1997, Complete Works , edited with an Introduction and notes by J. M. Cooper, D. S. Hutchinson associate editor, Indianapolis: Hackett.

- Press, G., and Duque, M. (eds), 2022, The Bloomsbury Handbook of Plato , London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Puchner, M., 2010, The Drama of Ideas. Platonic Provocations in Theatre and Philosophy , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rowe, Ch., 1999, “Myth, History, and Dialectic in Plato’s Republic and Timaeus-Critias ”, in R. Buxton (ed.), From Myth to Reason? Studies in the Development of Greek Thought , Oxford: Oxford University Press, 251–262.

- Rowe, Ch., 2003, “The Status of the ‘Myth’ in Plato’s Timaeus ”, in C. Natali and S. Maso (eds.), Plato Physicus: Cosmologia e antropologia nel Timeo , Amsterdam: Adolf Hakkert, 21–31.

- Sallis, J. (ed.), 2017, Plato’s Statesman. Dialectic, Myth, and Politics , New York: SUNY Press.

- Schofield, M., 2009, “Fraternité, inégalité, la parole de Dieu: Plato’s authoritarian myth of political legitimation”, in C. Partenie (ed.), Plato’s Myths , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 101–115.

- Sedley, D., 2009, “Myth, Punishment and Politics in the Gorgias ”, in C. Partenie (ed.), Plato’s Myths , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 51–76.

- Strauss, L., 1964, The City and Man , Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Tanner, S. M., 2017, Plato’s Laughter , New York: State University of New York Press.

- Taylor, A.E., 1928, A Commentary on Plato’s Timaeus, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Vlastos, G., 1939, “The Disorderly Motion in the Timaeus ”, Classical Quarterly , 33: 71–83; cited from Studies in Plato’s Metaphysics , R.E. Allen (ed.), London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1965, 379–99.

- Yunis, H., 2007, “The Protreptic Rhetoric of the Republic ”, in G. R. F. Ferrari (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Plato’s Republic, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1–26.

- Zimmermann, B., 2018, “Theatre of the Mind: Plato and Attic Drama”, Ariadne , 22 (2015–16): 93–105.

How to cite this entry . Preview the PDF version of this entry at the Friends of the SEP Society . Look up topics and thinkers related to this entry at the Internet Philosophy Ontology Project (InPhO). Enhanced bibliography for this entry at PhilPapers , with links to its database.

- Last Judgments: Plato, Poetry and Myth , a short podcast by Peter Adamson (Philosophy, Kings College London).

Plato | Plato: middle period metaphysics and epistemology | Plato: rhetoric and poetry | Plato: Timaeus | Socrates

Acknowledgments

This entry is loosely based on my introduction to a volume I edited, Plato’s Myths , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009. There is some inevitable overlap, but this entry is sufficiently different from the above-mentioned introduction to be considered a new text. A version of this introduction was presented at the University of Neuchâtel. I am grateful to my audience for their critical remarks. Feedback on a first draft has come from Richard Kraut.

Copyright © 2022 by Catalin Partenie < cdpartenie @ politice . ro >

- Accessibility

Support SEP

Mirror sites.

View this site from another server:

- Info about mirror sites

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy is copyright © 2023 by The Metaphysics Research Lab , Department of Philosophy, Stanford University

Library of Congress Catalog Data: ISSN 1095-5054

Essay on Myths And Legends

Students are often asked to write an essay on Myths And Legends in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Myths And Legends

Understanding myths and legends.

Myths and legends are stories from long ago. They are full of adventure and often teach lessons. Myths usually explain how something in nature or human behavior began. Legends are tales about heroes and their brave deeds. Both are passed down through generations and are important in every culture.

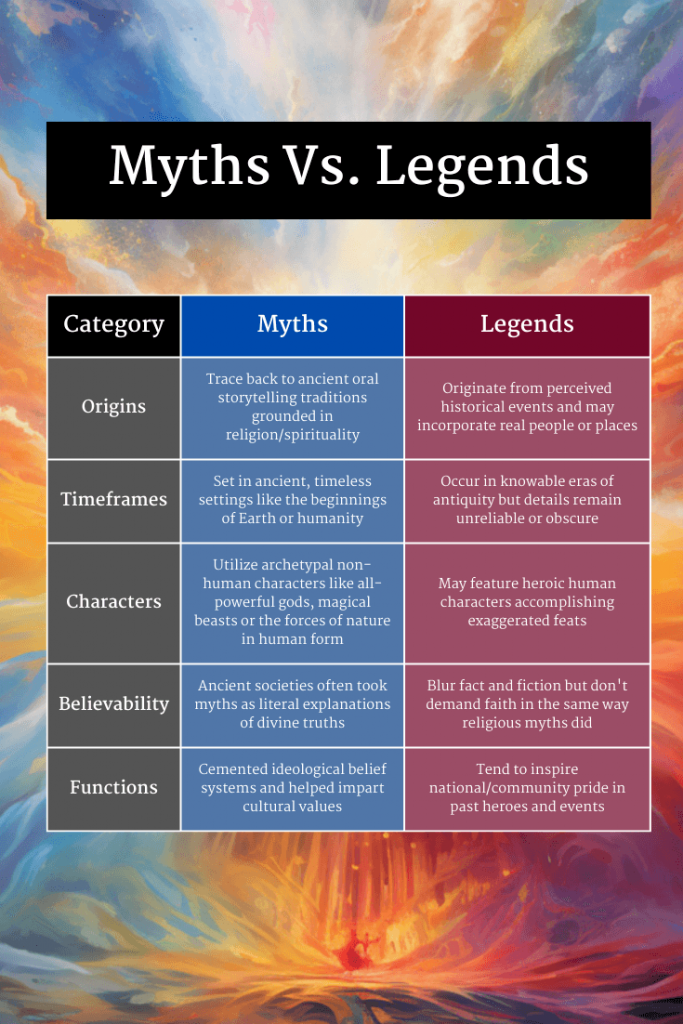

Differences Between Myths and Legends

Myths are often about gods and magic, and they explain mysteries of life. Legends are usually about people who might have lived. They tell about their courage and strength. While myths are more about belief, legends can be partly true.

Why Myths and Legends Matter

These stories are more than just tales. They give us morals and show us how to act. They connect us to our past and to people everywhere. Myths and legends help us understand different cultures and their values. They are a bridge to the world’s history.

250 Words Essay on Myths And Legends

What are myths and legends.

Myths and legends are stories that have been told for a very long time. They are like a bridge that connects us to the past. Myths are often about gods, goddesses, and supernatural beings. They try to explain how the world was made and why things happen. Legends are a bit different. They are usually about heroes and famous people. Both myths and legends teach us lessons and share the values of the culture they come from.

The Purpose of Myths and Legends

It’s important to know that myths and legends are not the same as fairy tales or fables. Myths are mostly about gods and are sacred to the people who believe in them. Legends are often based on real events or people but are exaggerated over time. Unlike fairy tales, legends can sometimes be true.

Why We Still Love These Stories

Even today, we love these old stories. They are exciting and full of adventure. They help us dream and imagine. Plus, they bring people together because they are stories everyone can share. Myths and legends are like treasures from long ago that still sparkle and shine for us to enjoy.

500 Words Essay on Myths And Legends

Long ago, before science could explain the mysteries of the world, people used stories to make sense of things. These stories are what we call myths and legends. Myths are tales that were told to explain natural events, like thunder and lightning, or the changing of the seasons. Legends are a bit different; they are stories that are told about people and their actions or great events, and sometimes they are based on real historical figures, but they are often exaggerated.