- Bookfox Academy (All Courses)

- Write Your Best Novel

- How to Write a Splendid Sentence

- Two Weeks to Your Best Children’s Book

- Revision Genius

- The Ultimate Guide to Writing Dialogue

- Your First Bestseller

- Master Your Writing Habits

- Writing Techniques to Transform Your Fiction

- Triangle Method of Character Development

- Children’s Book Editing

- Copy Editing

- Novel Editing

- Short Story Editing

- General Books

- Children’s Books

100 Ways to End a Story (with examples)

But where do you stop? Which sentences are the last sentences?

In this post, we’ll look at 100 ending lines from a diverse group of authors, both novelists and short story writers. We’ll identify how different types of endings contribute to a story. And, ultimately, we’ll determine how the author crafts a sense of satisfaction in their closing phrases.

After collecting many, many endings, the following categories emerged:

Cliffhanger

Normally, writers think of using a cliffhanger at the end of a chapter. But they absolutely can be used at the end of a story or book, for a few reasons:

- Pique the reader’s interest for the next book in the series

- Uses the “in media res” technique to go out on a high point, rather than dribble to a conclusion

- Extend the reader’s imagination beyond the story, so they finish hungry for more, and curious about the future of the storyline. It keeps the story alive, rather than closing it off.

“Lie back, Michael, my sweet.” She nodded briskly at Pauline. “If you’ll secure the strap, Nurse Shepherd, then I think we can begin.”

— Ian McEwan, “Pornography”

“I turned and looked past the neighborhood kids — my playmates — at the two men, the strangers. They were lean and seedy, unshaven, slouching behind the brims of their hats. One of them was chewing a toothpick. I caught their eyes: they’d seen it too.

I threw the first stone.”

— T. C. Boyle, “Rara Avis”

“Then his father walks toward the door stooping slightly and B stands aside to give him room to move. Tomorrow we’ll leave, tomorrow we’ll go back to Mexico City, thinks B joyfully. And then the fight begins.”

– Roberto Bolano, “Last Evenings on Earth”

Whatever you’re ending on, it’s something you want to emphasize, right? So heighten that emphasis with repetition.

Here’s an exercise: take all the examples below and try rewriting them without any repetition. Just say the key word once. Doesn’t have the same ring, does it? In fact, it makes it seem like the middle of the story, just another unremarkable line.

It takes two or three repetitions before there’s a finality to it, like a bell tolling for the conclusion of the story.

“His feet are light and nimble. He never sleeps. He says that he will never die. He dances in light and in shadow and he is a great favorite. He never sleeps, the judge. He is dancing, dancing. He says that he will never die.”

— Cormac McCarthy, Blood Meridian

“Big flakes not falling in orderly rows, a dervishing mob that swirls, lifts, goes limp, noiselessly spatters the glass. Snow obscuring the usual view greeting me when I’m up at crazy hours to relieve an old man’s panicked kidneys or just up, up and wondering why, staring at blank, black windows of a hulking building that mirrors the twenty-story bulk of ours, up prowling instead of asleep in the peace. I hope you’re still enjoying, peace I wish upon the entire world, peace I should know better by now than to look for through a window, the peace I listen for beside you in the whispering of our tangled breaths.”

— John Edgar Wideman, “Microstories”

“I imagined the story of a girl made human. I imagined Tallie’s grave, forsaken and remote. I imagined banishing forever those sentiments that she chastened and refined. I imagined everyone I knew sick to the point of death. I imagined a creature even more slow-hearted than myself. I imagined continuing to write in this ledger, here; as though that were life; as though life were not elsewhere.”

— Jim Shepard, “The World to Come”

“Sometimes all humanity strikes me as lovely. I just want to reach out and stroke someone, and say, ‘There, there, it’s all right honey. There, there, there.’”

— Sandra Cisneros, “Never Marry a Mexican”

“That would be the man we’d spare. That would be the man who’d drop to his knees in the mud and, in the cloud of gun smoke, raise his hands in surrender. That would be the man who’d tell us who he was, where he’d come from and why.”

— Will Mackin, “Crossing the River No Name”

“In the desert, in the lightning, in his crumbling duplex, in the field, in the many rooms of night, Wild Turkey wakes up, he wakes up, he wakes up.”

— Arna Bontemps Hemenway “The Fugue”

“Then sometimes I get up and don my robe and go out into our quiet neighborhood looking for a magic thread, a magic sword, a magic horse.”

— Denis Johnson, “The Largesse of the Sea Maiden”

“Your time’s not up. Your time’s not even close to being up.”

— David Means, “The Chair “

Sense of Sound

Good writers understand that sensory details are the lifeblood of fiction. And just as images are crucial ways to end a story (that’s the next section), you can also use sound as a way to dial up or dial down the end of your story.

A crescendo ends a story well because it makes the story’s end feel climatic. While a decrescendo eases you out of the story, giving a sense of closure to the reader.

If you look at the examples below, especially Jones and Bausch, you see how they use sound as a stand-in for a character — a deceased mother’s footsteps echoing through time, a wife’s domestic duties that make the husband feel estranged from her.

So sound can often a way to wrestle with complex character conflicts.

“And even when the teacher turns me toward the classrooms and I hear what must be the singing and talking of all the children in the world, I can still hear my mother’s footsteps above it all.”

— Edward P. Jones, “The First Day”

“The mastiff’s howl tears through the estate, setting off the usual thousand and twelve strange little circuses that disrupt the science of slavery.”

— Patrick Chamoiseau, “The Old Man Slave and the Mastiff”

“A long silence and then, slowly, applause, soft at first, then waves of it, which on this old recording came across like a pounding rain. I was shivering. There was no question we were under water.”

— Daniel Alarcón, “The Bridge”

“She heard the barking of an old dog that was chained to the sycamore tree. The spurs of a cavalry officer clanged as he walked across the porch. There was the hum of bees, the musky odor of pinks filled the air.”

— Kate Chopin, The Awakening

“He shut his eyes. Listened to the small sounds she made in the kitchen, arranging her flowers, running the tap. Mary, he had said. But he could not imagine what he might have found to say if his voice had reached her.”

— Richard Bausch, “Aren’t You Happy for Me?”

Descriptions

When you end a story, you’re helping the reader transition from the world of the story back into the real world. Sometimes that transition is easier if the last lines of the story don’t deal with the main characters, or plot, or themes, but instead talk about the universe of the story.

Namely: description. Try to describe a particular thing in the story which resonates with the main themes of your story. If you’re writing about father/son relationships, then end on the description of your character seeing a father walk with his son.

If you have a character sacrificing everything in the hopes of a big payday, then show that same idea in the animal world, for instance, pelicans divebombing for fish, like the Taylor Antrim example below.

“They’ve forgotten, or left on purpose, a few things they don’t need, things I hold on to. Pictures the girls drew, shells they picked up at the beach, the last drops of a perfumed shower gel. Shopping lists in the faint, small script that the mother used, on other sheets of paper, to write all about us.”

— Jhumpa Lahiri, “The Boundary”

“His eyes went upward, looking again for some civilizing sign — better yet, for the rectangular peak of his building, like the needle of a compass, the darkness down here, the shadow of his life up there. Friedrich and Lana resting up for tomorrow. Paulette waiting for him posed on all fours in bed. They were trying. He was trying. But above him there was just sky and trees in all directions.”

— David Gilbert, “The Sightseers”

“And in the morning when the sun came up and the colors of the hill and its valley accelerated from gray and brown to red and green to white, the company agent gathered stones for his family and they breakfasted on snow.”

— Jim Crace, “The Prospect from Silver Hills”

“Boom-splash. The pelicans take these kamikaze plunges into the water. The way they hit, not one should survive — but of course they all do. They come up with their beaks full of fish.”

— Taylor Antrim, “Pilgrim Life”

Unspoken Dialogue

Unspoken Dialogue is very similar to a cliffhanger. While a cliffhanger refuses to resolve plot , this Unspoken Dialogue technique refuses to resolve the dialogue .

There’s tension when a character wants to say something, but doesn’t.

If you’re trying to learn how to write good dialogue, it’s always important to remember that characters don’t often say exactly what they’re thinking, or even what they want to say.

Why does this work to conclude a story? Well, it highlights the weakness of the character, how they are not doing what they want to be doing. They are holding back, and perhaps they will regret it later.

“I wanted to say she’d lied to us all, she’d faked it about the dog, as if it mattered whether the animal spoke, as if love were about the truth, as if he would love her less — and not more — for pretending to talk to a dog.”

— Francine Prose, “Talking Dog”

“Tell more, more, I want to say to Eduardo but do not say because he seems ready to leave. Tell me about Garcilaso and about how things went well for him.”

— Joseph O’Neill, “The Sinking of the Houston”

“They are always very interested to hear that you don’t read music. Once, you almost said— to a sneaky fellow from the Daily News, who was inquiring— you almost turned to him and said Motherfucker I AM music. But a lady does not speak like that, however, and so you did not.”

— Zadie Smith, “Crazy They Call Me”

“She begins to scream, her face turning even redder, you cannot hear or understand what she is saying but you know she hates your father, hates you, hates many, many people. You want to help your father, the man who has only recently come back into your life, clean-shaven and speaking of God, you want to run toward him and defend him and protect him, but now he is holding out his hand to the man again, he has taken off his hat and is holding it out toward the man. The woman is now silent. The man takes the hat, a brand-new fedora with a feather, and puts it on his head. And looks at you, as if for the first time.”

— Justin Bigos, “Fingerprints”

Asking Questions

A question is one of the most popular ways to end a story (look at all the examples below!). I could even add more quite easily, like the question to conclude Margaret Atwood’s book, “Handmaid’s Tale”: “Are there any questions?”

But if you use this technique, I would recommend following these three guidelines:

- Must not have an easy answer

- Must resonate with the main themes of your book

- Must strike an emotional chord (look at the Russel Banks example).

“But why are you invested in other people’s stories? You too must be unable to fill in the gaps. Can’t you be satisfied with your own dreams?”

— Antonio Tabucchi, “A Riddle”

“And who would she tell her stories to while he was gone? Who would listen?”

— Russel Banks, “My Mother’s Memoirs, My Father’s Lie, and Other True Stories”

“Then in the space of a wet blink, the gap between the trees would close and the mown grass disappear, a violent indigo cloud would cover the sun and history, gross history, daily history, would forget. Is this how it would be?”

— Julian Barnes, “Evermore”

“I imagined John-Jin’s girder underneath me. I wondered, in my rage, if you took that one piece away, would everything fall?”

— Rose Tremain, “John-Jin”

If a blind man could play basketball, surely we…If he had known Doc’s story would it have saved them? He hears himself saying the words. The ball arches from Doc’s fingertips, the miracle of it sinking. Would she have believed any of it?”

— John Edgar Wideman, “Doc’s Story”

“Safer and better to have no freedom, maybe, but no, you wouldn’t say that. The humming stopped when he flicked the light switch by the door. No you wouldn’t say that, would you? In the dark of the hall he could not see his way; he went toward the vague light of the front window with one hand on the wall. No you wouldn’t but what would you say?”

— Madison Smartt Bell, “Witness”

“Who was it that thought up that idea, the idea that had made today better than yesterday? Who loved him enough to think that up? Who loved him more than anyone else in the world loved him?

— George Saunders, “Puppy”

“Where was she now, this Clara? What had become of her, this ardent, hopeful girl in her white dress, surrounded by her family, godparents, friends, that her Bible should end up in a Goodwill bin? Even if she no longer read it, or believed it, she wouldn’t have thrown it away, would she? Had something happened? Ah, girl, where were you?”

— Tobias Wolff, “Bible”

“He reached for the telephone and dialed his home number. ‘Rhona,’ he said in the quaking receiver. ‘Would you like to see the juvenile tuataras? The babies?’”

— Barbara Anderson, “Tuataras”

“But for the other man, who would be watching the night fall around the orange halo of the street lamps with neither longing nor dread, what did the future offer but the comfort of knowing that he would, when it was time for his daughter to carry out her plan of revenge, cooperate with a gentle willingness?”

— Yiyun Li, “A Man Like Him”

You can’t write good fiction without making your characters feel things (and your reader feel things). So here, we see authors ending stories by showing the final arc of their character’s emotions.

Some of these characters have emotional epiphanies, feeling something for the first time. Others have felt it all along but perhaps only now have been able to admit it to themselves.

But if character arc and character change are essential for stories, it makes sense that their emotional journey would conclude the narrative.

“Even so, I sat there gazing up at the granite outcrops of Spruce Clove streaked in evening gold, I had an almost overpowering sense of being looked at myself, stared at in uncomprehending astonishment by some wild creature standing in the doorway.”

— James Lasdun, “Oh Death”

“I stand here shameless in ways he has never seen me. I am free, afloat, watching somebody else.”

— Bharati Mukherjee, “A Wife’s Story”

“She has done an outrageous thing, but she doesn’t feel guilty. She feels light and peaceful and filled with charity and temporarily without a name.”

— Margaret Atwood, “Hairball”

Paul Harding, who won the Pulitzer Prize for “Tinkers,” said that contrast is the essential technique of music, painting, and storytelling.

Below, we see contrasts between:

- chill cats and stressed-out humans

- the busyness of day with the solitude of night

- the flowers of love with the chants for the dead.

When you contrast something, you throw it into higher relief. A happy person doesn’t seem exceptionally happy until you see her side by side with a depressed person.

Contrast offers that extra emphasis — much like repetition — to make the reader feel satisfied that this ending resolves the story.

“She hears a distant siren, the wind in the trees, the bass beat from a passing car. Please, she thinks. Please. She is about to go inside for a flashlight when she hears the familiar bell and then sees the cat slinking up from the dark woods, her manner cool and unaffected.”

— Jill McCorkle, “Magic Words”

“Susanne sat on the couch, surrounded by her family while out in the night, partner to the extraordinary, Roy held a shovel made for digging deeper in the dirt.”

— Samantha Hunt, “The Yellow”

“By day she entertained a constant stream of visitors. At night her father kept vigil beside her bed.”

— Jennifer Haigh, “Paramour”

“Violins and lit candles revolved in the sky. Leo ran forward with flowers outthrust. Around the corner, Salzman, leaning against a wall, chanted prayers for the dead.”

— Bernard Malamud, “The Magic Barrel”

Marcel Proust’s memories brought back by the taste of a madeleine are probably the most famous memories in literature, but stories have always used memory to make readers nostalgic, evoke the senses, and make us feel the bite of time.

When you end a story with memory, it ties the whole story together — past is united with the present.

In some ways, ending a story with a memory is the opposite of a cliffhanger — memory looks at the past, while a cliffhanger anticipates the future.

Memory allows the writer to skip around in time to find the perfect character moment to end the story — which could be much, much earlier in their life, or only a few years back, or only last week.

Perhaps in the character’s current life, there’s no event that perfectly captures the emotion you’re going for, so mine the past for it.

“I no longer remembered the day we married. Only the day I knew we would, those moments with my heart warm and rapt, the silent promise of the frozen world, the elm chafing in its coat of ice.”

— Karen Brown, “Galatea”

“…She will be secretly glad, relieved that time is passing, that Paris is again becoming nothing more than a word she might see on the cover of a glossy magazine or on a cable travel channel, certainly not a place where she once spent a few breaths of her life, and she will hardly remember the way the Seine sliced the city in half, a radiant curving knife, merciless and perfect.”

— Victoria Lancelotta, “The Anniversary Trip”

“He remembers waking up the morning after they bought the car, seeing it, there in the drive, in the sun, gleaming.”

— Raymond Carver, “Are These Actual Miles”

“Who will remember?”

— Alex Rose, “Ostracon”

“She will see the garden that day and the tears shining in her sister’s large blue eyes and remember her unanswered cry for help.”

— Sheila Kohler, “Magic Man”

“And as for the scar, I’m glad it is not on Nyamekye. Any time I see it I only recall one afternoon when I sat with my chin in my breast before a Mallam came, and after a Mallam went out.”

— Ama Ata Aidoo, “A Gift from Somewhere”

The Epiphany

The epiphany ending is the classic story ending. After everything the character has gone through, what have they learned?

This is the chance to show that the journey has not been in vain, that your characters have changed and learned and grown because of this journey.

Epiphanies are particularly useful for short stories, rather than novels, because short stories have less runway for plot. So you can’t have a huge murder or birth or world catastrophe solved at the end of a short story (the way most novels do), but you can show the character realizing something about themselves, others, or the world.

“He closed the door carefully, not slamming it. Clea and I waited an appropriate interval, then turned and clung to each other in a kind of rapture. Understanding, abruptly and at last, just what it takes to be a King. How much, in the end it actually costs.”

— Jonathan Lethem, “The King of Sentences”

“He was shot five or six times, but being such a big man and such a strong man, he lived long enough to recognize the crack of the guns and know that he was dead.”

— Nathan Englander, “The Twenty-Seventh Man”

“Years later, as an adult, I realized that what my little sister had confided to me in a quiet voice in the wind cave was indeed true. Alice really does exist in the world. The March hare, the Mad Hatter, the Cheshire Cat— they all really exist.”

— Haruki Murakami, “The Wind Cave”

“— How d’you like my lion? Isn’t he beautiful? He’s made by a Zimbabwean artist, I think the name’s Dube.

— But the foolish interruption becomes revelation. Dumile, in his gaze — distant, lingering, speechless this time — reveals what has overwhelmed them. In this room. The space, the expensive antique chandelier, the consciously simple choice of reed blinds, the carved lion: all are on the same level of impact phenomena undifferentiated, undecipherable. Only the food that fed their hunger was real.”

— Nadine Gordimer, “Comrades”

“Sarah looked at him with an intent, halted expression, as though she were listening to a dialogue no one present was engaged in. Finally she said, “There are robbers. Everything has changed.”

— Joy Williams, “The Farm”

“And that was it. Somehow it didn’t really matter, finding out. Two years earlier, it would have changed my life. But on that day, I suppose the only thing I felt was some small measure of contentment for her: that he had, indeed, come back for her, just like she always said he would. They were different after all, destined to be together. I thanked Allen for bringing her things, watched him ride away on his motorcycle, and went inside to have dinner with my father.”

— Jess Walter, “Mr. Voice”

“And then, as if he had forgotten that she had already moved on to other things, as if we were still sitting across from each other, deep in one of our conversations without beginning, middle, or end, Room wrote that the last thing that had surprised her was that when Ershadi is lying in the grave he’s dug and his eyes finally drift closed and the screen goes black, it isn’t really black at all. If you look closely, you can see the rain falling.”

— Nicole Krauss, “Seeing Ershadi”

“‘No problem,’ the waitress sang, ‘no problem at all,’ replacing the girl’s fork, bending to snatch the soiled one off the floor. Smiling hard but not making eye contact with anyone. When she retreated leaving Richard alone with his son and the crying girl, it occurred to him, with the delayed logic of a dream, that the waitress must have thought he was the bad guy in all this.”

– Emma Cline, “Northeast Regional”

“But I remember you. I remember when we were so close that people couldn’t tell us apart. I remember your parents’ phone number, your neatly folded cutoffs and your constant fear of not being special. I remember when you started claiming that fictive characters are way better than friends, since they are less annoying, more interesting and never die. You stopped returning my calls. When I needed you the most you were nowhere to be found and when I died you started seeing me everywhere. On sidewalks, in shop windows, on balconies. So you decided to write my story. You dress me in cutoffs. You force extreme amounts of apple juice into me. You retell the most painful week of my life as it were a never-ending bachelor party. And it is not until the end. About. Here. That you realize what you’ve done. I’m not bitter, Miro. I’m just dead.”

— Jonas Hassen Khemiri, “As You Would Have Told It to Me (Sort Of) If We Had Known Each other Before You Died”

“It took some time for me to understand that Elida’s body had not been satiated on mine, that she wasn’t purring because she swallowed my heart.”

— Louise Erdrich, “The Big Cat”

“I used to think that all my emotions belonged in the past, to history, but I know that I yearn for the future just like everyone else. Even as life draws to close, I realize that I have never understood myself completely.

But now it certainly is too late to do more, to be more, in this lifetime.”

— Zhang Jie, “An Unfinished Record”

I am born at noon the next day. My mother tells me this is the first thing she did: she checked the clock. I am still attached to her when she looks. We are not yet two when she begins to keep track of me, the seconds I have been alive and then, after she cuts through the cord herself, cleaving my body from hers with a kitchen knife, the seconds I have been on my own.

This is what women do, she says.

By which she means she understands that one day I will leave her too. Lift off the ground, think myself beyond gravity.

—Aria Beth Sloss, “North”

The Unhappy Ending

The ending is one of your last chances to make the reader feel something. And while the happy ending is always a classic crowd-pleasing, I find that it’s often easier to make the reader feel sorrow.

Happiness is a tough sell, particularly when writing short stories. I think if you were going to survey 1000 short stories, a lot more would end sad than would end happy. Novels are probably the opposite — many more end happy than sad.

It’s mainly because of the length. When you’re writing short, you don’t have the time to acheive happiness without it feeling cheesy. While in the space of a novel, the happy ending feels earned.

“Now they were both dead, and the city was dirty and crumbling, and the man I was traveling with was sero-positive, and so was I. Mexico’s hopes seemed as dashed as mine, and all the goofy innocence of that first thrilling trip abroad had died, my boyhood hopes for love and romance faded, just as the blue in Kay’s lapis had lost its intensity year after year until it ended up as white and small as a blind eye. ”

— Edmund White, “Cinnamon Skin”

“Things are as they have always been. Whoever seeks a fixed point in the current of time and the seasons would do well to listen to the sounds of the night that never change. They come to us from out there.

— Amos Oz, “Where the Jackals Howl”

“She would be invisible, of course. No one would hear her. And nothing has happened, really that hasn’t happened before.”

— Margaret Atwood, “Wilderness Tips”

“There were women around Jesus when He died, the two Marys. They couldn’t do anything for Him. But neither could the men, who had all run away.”

— Robert Olen Butler, “Mr. Green”

“I think of the chimp, the one with the talking hands.

In the course of the experiment, that chimp had a baby. Imagine how her trainers must have thrilled when the mother, without prompting, began to sign to her newborn.

Baby, drink milk.

Baby, play ball.

And when the baby died, the mother stood over the body, her wrinkled hands moving with animal grace, forming again and again the words: Baby, come hug, Baby, come hug, fluent now in the language of grief.”

— Amy Hempel, In the Cemetery Where Al Jolson is Buried

“It was not a happy life, but it was all that was left to them, and they took it up without complaint, for they knew they were powerless against some Will infinitely stronger than their own.”

— Paul Laurence Dunbar, The Sport of the Gods

“What would burst forth? A monkey’s paw? A lady? A tiger?

But there was nothing at all.”

— Lorrie Monroe, “Referential”

The Waiting Ending

What does it mean when you have a character waiting at the end of a story? Well, they are expecting the future. But the reader can’t go to the future with them.

It signals a small break in the storyline: this current story has ended, but the future one has not begun. It’s like the character is about to step into narrative limbo.

A “waiting” ending is definitely a quiet ending. It takes advantage in a lull in the storyline to bow out and conclude.

If you write a waiting ending, pay careful attention to subtext:

- Perhaps this character will be waiting a long time.

- Perhaps they are the waiting type of character — a passive character.

- Perhaps waiting signals a sad ending — what they wanted most didn’t arrive by the end

“I measured the passing of time by the progress of the fires in the distant north. My old man gave me daily updates, and I pretended to listen. Five hundred, a thousand, two thousand fires. After a month they had burned out, and I was still waiting.”

— Daniel Alarcón, “The Idiot President”

“He looked toward the eastern sky. It seemed he’d been running a week’s worth of nights, but he saw the stars hadn’t begun to pale. The first pink smudges on the far Ridgeline were a while away, perhaps hours. The night would linger long enough for what would come or not come. He waited.”

— Ron Rash, “Into the Gorge”

“The ice plant was watery-looking and fat, and at the edge of my vision I could see the tips of my father’s shoes. I was sixteen years old and waiting for the next thing he would tell me.”

— Ethan Canin, “The Year of Getting to Know Us”

“Wait here, wait here!” he cried and jumped up and began to run for help toward a cluster of light she saw in the distance ahead of him. “Help! Help!” he shouted, but his voice was thin, scarcely a thread of sound. The lights drifted farther away the faster he ran and his feet moved numbly as if they carried him nowhere. The tide of darkness seemed to sweep him back to her, postponing from moment to moment his entry into the world of guilt and sorrow.”

— Flannery O’Connor, “Everything that Rises Must Converge”

“Walking to the end of the hallway by the kitchen, he seated himself against the wall. He sat there quietly, waiting for Case to emerge.”

— Bradford Tice, “Missionaries”

“Joshua wondered what they would do now. The need he felt was like when he stepped on the sliver of glass, and his mother pulled at the skin with her tweezers, and pushed them inside, until she found the glass. It was like when she told him to get ready, to squeeze his father’s hand. Clenching his teeth, closing his eyes, waiting.”

— Mike Meginnis, “Navigators”

Figurative Language & Poetic Devices

Aristotle said that comparison of two unlike things was the essence of genius. If so, the writers below are all geniuses.

Beauty has its own charm. The examples below use extended metaphors, multiple similes, and other examples of literary devices to cast a spell of beauty over the reader.

And these comparisons are often symbolic of the characters and the events of the story (for instance, the birds in the Ann Beattie story).

“She pulled in her horizon like a great fish-net. Pulled it from around the waist of the world and draped it over her shoulder. So much of life in its meshes! She called in her soul to come and see.”

— Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God

“Nettie lay there beside him, her breath blowing on his shoulder as they studied the stars far above the field — little pinpoint holes punched through the night sky like the needle holes around the tiny stitches in the quilting. Nettie. Nettie Slade. Her dress had self-covered buttons, hard like seed corn.”

— Bobbie Ann Mason, “Wish”

“Angela was remembering all this, and feeling such a strong surge of sorrowful loss, and at the same time she was studying with interest the miraculous rescue of St. Placidus from drowning, painted on the wall in the sacristy in San Miniato. St. Placidus was rolling fatalistically amid the blue waves of his pond while one of his comrades, endowed with special powers by St. Benedict, came walking across the water to save him. In the picture it looked like such a harmless little point, carved into the earth as neatly as a circle of stamped-out pastry, or a hole cut into the ice for fishing.”

— Tessa Hadley, “Cecilia Awakened”

“He looked at his wife, whom he loved, whom he looked forward to convincing, and felt as though he were diving headfirst into happiness. It was a circus act, a perilous one. Happiness was a narrow take. You had to make sure you cleared the lip.”

— Elizabeth McCracken, “Thunderstruck”

“In the flood of flame-colored light their flesh turned coral.”

— Helen Simpson, “Heavy Weather”

“Louisa sat, prayerfully numbering her days, like an uncloistered nun.”

— Mary E. Wilkins Freeman, “A New England Nun”

“When she turned back into the empty room she looked as though youth had touched her on the lips.”

— Edith Wharton, “The Angel at the Grave”

“In time, his breathing changed, and hers did. Calm sleep was now a missed breath — a small sound. They might have been two of the birds she so often thought of, flying separately between cliffs— birds whose movement, which might seem erratic, was always private, and so took them where they wanted to go.”

— Ann Beattie, “In Amalfi”

Brene Brown’s TED talk about vulnerability is one of the most watched TED talks of all time. Her thesis is simple: people respond to vulnerability.

It holds true in real life just as it does in fiction.

When a character keeps a secret, reveals a secret, or makes a confession, the reader feels closer to them. Even if we disagree with them, we feel like we know them.

“The secret died with him, for Pavageau’s lips were ever sealed.”

— Alice Dunbar-Nelson, “The Stones of the Village”

“Very often I sold my blood to buy wine. Because I’d shared dirty needles with low companions, my blood was diseased. I can’t estimate how many people must have died from it. When I die myself, B.D. And Dundun, the angels of God I sneered at, will come to tally up my victims and tell me how many people I killed with my blood.”

— Denis Johnson, “Strangler Bob”

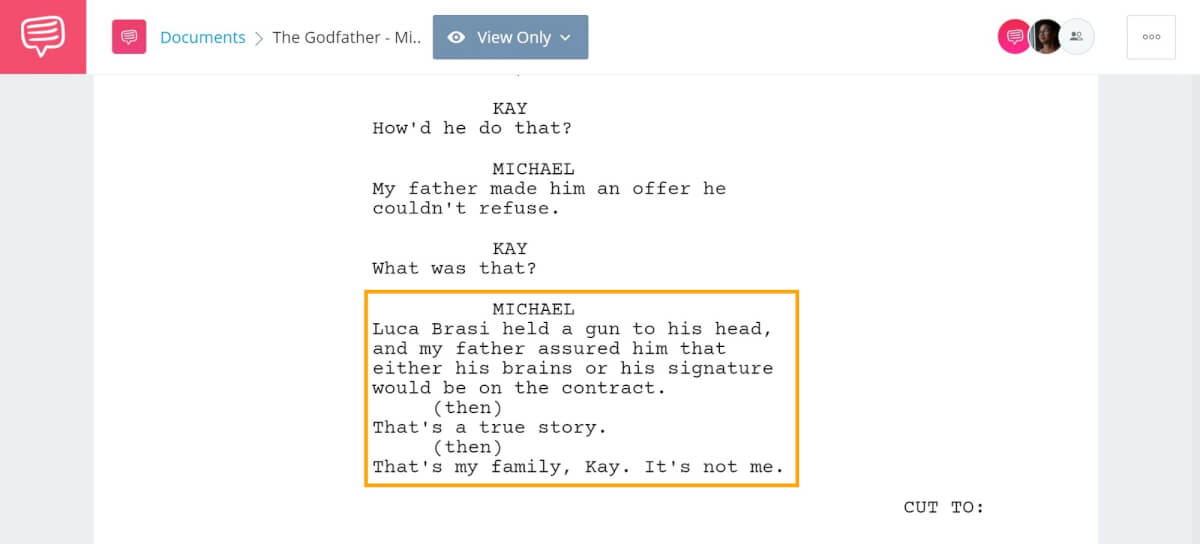

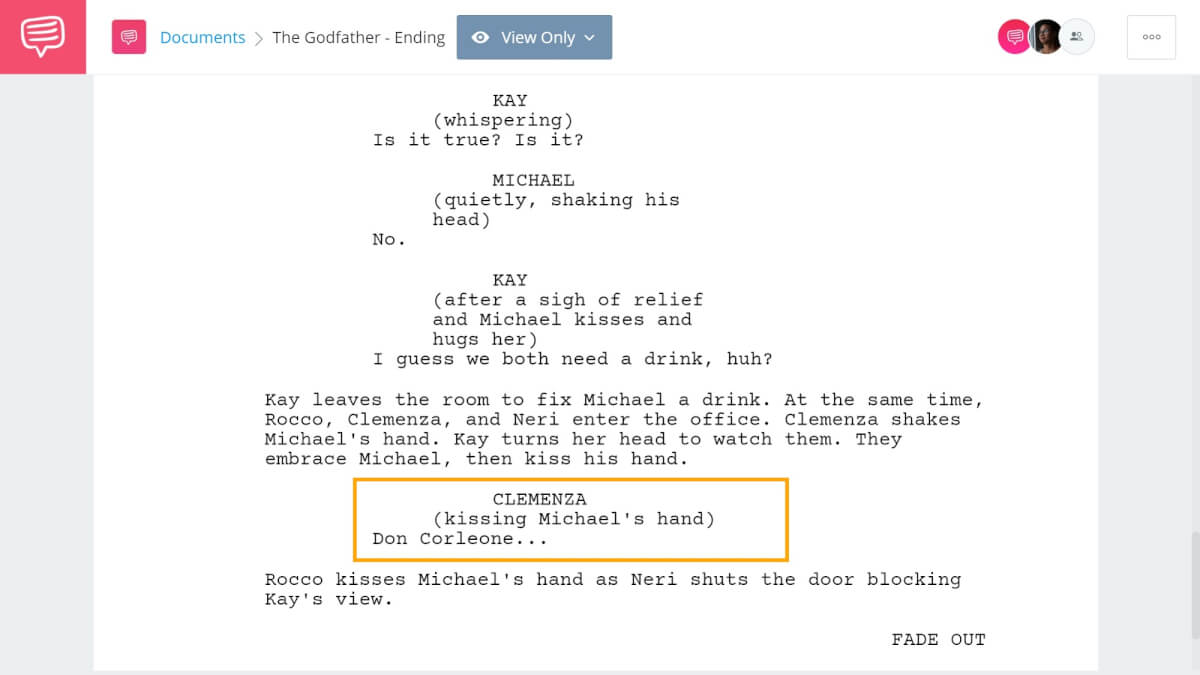

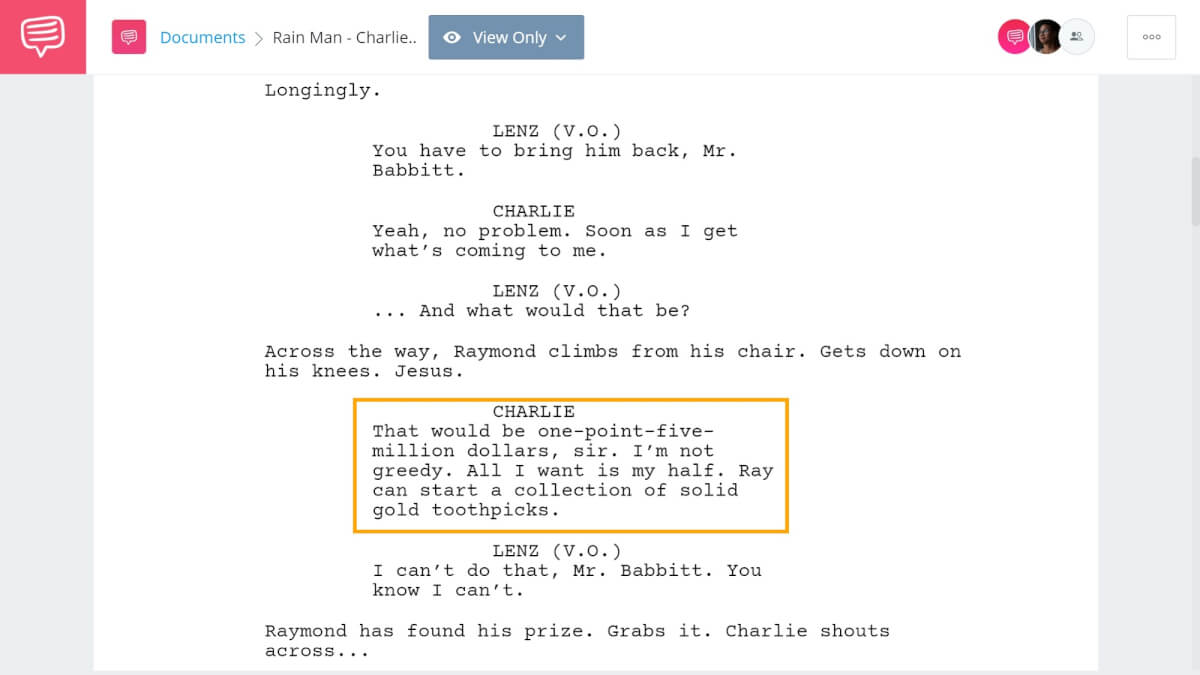

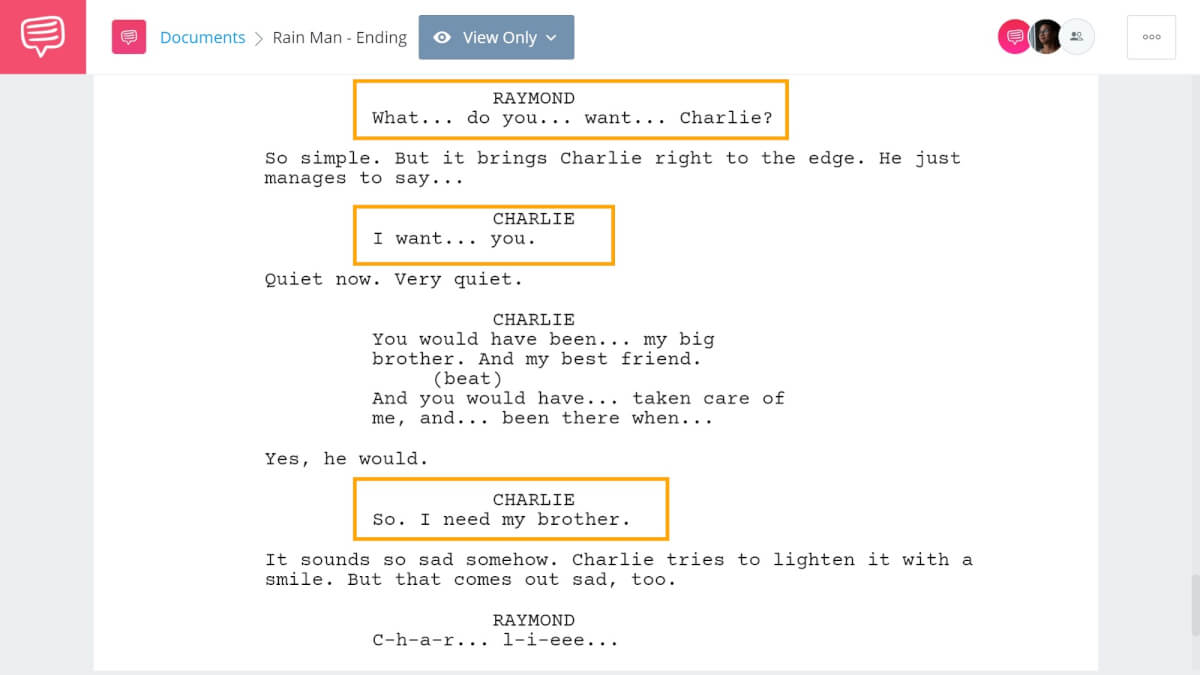

Powerful Dialogue

Here’s some advice on how to write a good dialogue ending:

- Pay attention to subtext . If any place in your story needs dialogue with a double meaning, it’s the ending. It should have a plain interpretation, but also resonate with some deeper issues of plot.

- Make sure it’s the protagonist who gets the final word . In almost all cases, it’s the protagonist or one of the main characters who speak last. A minor character wouldn’t make sense.

“Please come back inside mom! Please get out of the street!”

— Antonya Nelson, “Chapter Two”

“Darling, the angels have themselves a lifetime to come to us.”

— Edwidge Danticat, “Night Women”

“Nemecia held a wineglass up to the window and turned it. “See how clear?” Shards of light moved across her face.”

— Kirstin Valdez Quade, “Nemecia”

“But I had my eyes closed. I thought I’d keep them that way for a little longer. I thought it was something I ought to do.

‘Well?’ He said, ‘Are you looking?’

My eyes are still closed. I was in my house. I knew that. But I didn’t feel like I was inside anything.

‘It’s really something,’ I said.”

— Raymond Carver, “Cathedral”

“My dear,” replied Valentine, “has not the Count just told us that all human wisdom is contained in the words ‘Wait and hope!”

— Alexandre Dumas, The Count of Monte Cristo

“There were lots of old people going around then with ideas in their heads that didn’t add up — though I suppose Old Annie had more than most. I recall her telling me another time that girl in the Home had a baby out of a big boil that burst on her stomach, and it was the size of a rat and had no life in it, but they put it in the oven and it puffed up the right size and baked to a good color and started to kick its legs (Ask an old woman to reminisce and you get the whole ragbag, is what you might be thinking by now.)

I told her that wasn’t possible, it must have been a dream.

‘Maybe so’ she said, agreeing with me for once. ‘I did used to have the terriblest dreams.’”

— Alice Munro, “A Wilderness Station”

A Character in Denial

The reader gets a sick sense of delight when final lines reveal something a character refuses to acknowledge.

“Maybe it wasn’t such a terrible idea. Maybe it could make them happy. He found a mark on Miriam’s shimmering pale dress and followed it through the trees.”

— Sarah Kokernot, “M & L”

“His gut told him that his mother-in-law knew what had happened that day in the car. Come to think of it, she had never once mentioned the day of the accident to him. She had never even asked about it. His mother-in-law turned her cold gaze back to the plant. To put his crazy thoughts to rest, Oghi told himself that he just really liked plants. He could not think why that might be.”

— Hye-young Pyun, “Caring for Plants”

The Unknown

These final lines endear readers as characters reveal what remains mysterious:

“But as I write this it occurs to me that I don’t know where I ever got that idea. In fact, I have no memory of whether the desk arrived to me with the drawer locked. It’s possible that I unknowingly pushed in the cylindrical lock years ago, and that whatever is in there belongs to me.”

— Nicole Krauss, “From the Desk of Daniel Varsky”

“’Listen to me,’ he said, expelling all his breath with the words. Two ragged breaths later he tried again, but Jill moved her hand from his forehead to his mouth. ‘Help me,’ he said into her fingers. But the words were whispered, and she mistook them for a kiss and smiled.”

— Angela Pneuman, “Occupational Hazard”

“He knew he was at the beginning of something, though just then he couldn’t say exactly what.”

— Bret Anthony Johnston, “Encounters with Unexpected Animals”

“I do not know where this voyage I have begun will end. I do not know which direction I will take. I dropped the package on a park bench and started walking.”

— Bharati Mukherjee, “The Management of Grief”

If anywhere it’s time to tell the truth, it’s the ending.

Have your characters spill their guts and reveal everything at the end. Or have the narrator offer wisdom or the naked truth.

“It’s the kind of impossible story that holds a family together. You tell it over and over again; and with the passage of time, the tale becomes more unbelievable and at the same time increasingly difficult to disprove, a myth about the life you carry.”

– Greg Hrbek, “Sagittarius”

“As the manual often states, it’s my future. And it’s the only one I get.”

— Diane Cook, “Moving On”

“I’ve begun to appreciate just how much work parents invest in their children, and wives in their husbands; it’s only fair for the investor to become the beneficiary.”

— Katie Chase, “Man and Wife”

“…I survive. It’s only one thing. But it’s also everything.

Pick yourself up.

Start over again.”

— Megan Miranda, All the Missing Girls

“She was knickerless. She was victorious. She was a truly modern female.”

— Nicola Barker, “G-string”

“I can stay. I can lie down. Let the snow fall on my face. Let its hands be tender.

Or I can walk, try to find my way in darkness.

I’m a grown woman, an orphan, I have these choices.”

— Melanie Rae Thon, “The Snow Thief”

Related posts:

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

One thought on “ 100 Ways to End a Story (with examples) ”

Excellent collection of endings, types… and quite clear and efficient comments. Thank you.

Every writer NEEDS this book.

It’s a guide to writing the pivotal moments of your novel.

Whether writing your book or revising it, this will be the most helpful book you’ll ever buy.

VIDEO COURSE

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Sign up now to watch a free lesson!

Learn How to Write a Novel

Finish your draft in our 3-month master class. Enroll now for daily lessons, weekly critique, and live events. Your first lesson is free!

Blog • Perfecting your Craft

Last updated on Mar 08, 2024

How to End a Story: The 6 Ways All Stories End

About the author.

Reedsy's editorial team is a diverse group of industry experts devoted to helping authors write and publish beautiful books.

About Martin Cavannagh

Head of Content at Reedsy, Martin has spent over eight years helping writers turn their ambitions into reality. As a voice in the indie publishing space, he has written for a number of outlets and spoken at conferences, including the 2024 Writers Summit at the London Book Fair.

When we first start to read books, we quickly understand that books have two types of ending: happy and sad. But as we develop our literary palate and read deeper, it soon becomes apparent that endings are somewhat more nuanced than that.

In the first part of this post, we will dive into the many types of endings that novelists have at their disposal — and reveal the impact they can have on the reader. In the second part, we'll give you some tried-and-true tips for writing an impactful ending for your own book.

The 6 types of story endings (with examples)

Let's dive into the most common types of story endings that you'll see over and over again in storytelling. Note that, as we provide some examples from novel endings, there will be... spoilers!

1. Resolved Ending

Wrap it up and put a bow on it. A resolved ending answers all the questions and ties up any loose plot threads. There is nothing more to tell because the characters’ fates are clearly presented to the reader.

Example: Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude provides a great example of a resolved ending. In his Nobel Prize-winning book, García Márquez intertwines the tale of the Buendia family and the small town where they live, from its creation until its destruction.

Before reaching the final line, however, he had already understood that he would never leave that room, for it was foreseen that the city of mirrors (or mirages) would be wiped out by the wind and exiled from the memory of men at the precise moment when Aureliano Babilonia would finish deciphering the parchments, and that everything written on them was unrepeatable since time immemorial and forever more, because races condemned to one hundred years of solitude did not have a second opportunity on earth.

With this ending, García Márquez effectively ends all hope of a sequel by destroying the entire town and killing off all the characters. Unlike a Deus Ex Machina ending, where everything is suddenly and abruptly resolved , this is an ending that fits with the central ideas and plot of this book. Though not exactly expected, it brings an appropriate closure to the Buendia family and the town of Macondo.

Why might you use a resolved ending? This sort of conclusion is common to standalone books — especially romance novels, which thrive on ‘happily ever afters’ — or the final installment in a series.

FREE COURSE

How to Write a Novel

Author and ghostwriter Tom Bromley will guide you from page 1 to the finish line.

2. Unresolved Ending

This type of ending asks more questions than answers and, ideally, leaves the reader wanting to know how the story will continue. It lets them reflect on what the hero has been through and pushes them to imagine what is still to happen. There will be some resolution, but it will, most likely, pose questions at the end and leave some doors open.

Example: Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince does exactly that. After years of confronting Voldemort, Harry finally knows the secret to bring him down once and for all. However, the road will only become more dangerous and will require more sacrifices than anybody thought.

His hand closed automatically around the fake Horcrux, but in spite of everything, in spite of the dark and twisting path he saw stretching ahead for himself, in spite of the final meeting with Voldemort he knew must come, whether in a month, in a year, or in ten, he felt his heart lift at the thought that there was still one last golden day of peace left to enjoy with Ron and Hermione.

Like Harry, readers know that a final meeting between him and Voldemort is coming and that everything will change for him and his friends. As a stand-alone book, this ending would probably be unsatisfactory. But as the penultimate book in the series, it leaves the readers wanting more.

Why might you use an unresolved ending? Because it can create anticipation and excitement for what comes next, you may want to use an unresolved ending if you are writing several books in a series. Who doesn’t love (and hate) a good cliffhanger?

3. Ambiguous Ending

An ambiguous ending leaves the reader wondering about the “what ifs.” Instead of directly stating what happens to the characters after the book ends, it allows the reader to speculate about what might come next — without establishing a right or wrong answer. Things don't feel quite unresolved , more just open to interpretation.

Example: The first installment of The Giver series, by Lois Lowry, uses this ending. The Giver focuses on Jonas, a teenager living in a colorless yet seemingly ideal society, and on the way he uses his newly assigned position as the Receiver of Memories to unravel the truth about his community and forge a new path for himself.

Downward, downward, faster, faster. Suddenly he was aware with certainty and joy that below, ahead, they were waiting for him; and that they were waiting, too, for the baby. For the first time, he heard something that he knew to be music. He heard people singing. Behind him, across vast distances of space and time, from the place he had left, he thought he heard music too. But perhaps it was only an echo.

Readers will wonder what happens to Jonas once he finishes his journey and what happens to the town and people he left behind. There are three more companion books, but the story centering on Jonas is finished. Readers will see him again, but only as a side character, and will neither find out how he rebuilt his life nor how his old community fared. There might be speculation, but an answer is never clearly given: that is left to the imagination.

When might you use an ambiguous ending? If you want your readers to reflect on the meaning of your book, then this is the ending for you. While a resolved ending may satisfy readers, it probably won’t give them much pause at all. However, by trying to unpick an ambiguous ending, they get closer to what you, as the author, are trying to say.

4. Unexpected Ending

If you have led your readers to believe that your book will end one way, but at the last possible moment, you add a unexpected twist that they didn’t see coming, you’ve got yourself an unexpected ending! For an author, this type of ending can be a thrill to write, but it must be handled with care. Handled poorly, it will frustrate and infuriate your reader.

An unexpected ending must be done so that, while surprising, still makes sense and brings a satisfactory conclusion.

Example: A popular novel that makes use of this ending is And Then There Were None by Agatha Christie , where she tells the tale of ten murders without an obvious culprit that took place in an isolated island mansion. [Spoilers coming!] The last lines of the novel read:

When the sea goes down, there will come from the mainland boats and men. And they will find ten dead bodies and an unsolved problem on Soldier Island. Signed: Lawrence Wargrave

The ways in which the murders occur let the reader suspect the guilt of just about every character — and then, in an epic twist, they all die, leaving the murders unexplained. It is not until the message in the bottle arrives that the true culprit is revealed, as one of the victims no less! The ending is satisfactory to the reader because it brings the plot to a close in a way that, though surprising, invites them to think back on how the murderer set things up for the remaining deaths, and ultimately makes sense.

Why might you use an unexpected ending? These ‘twist endings’ are the bread and butter of mystery novels . Just be aware that while fans of the genre will expect a twist — they won't want one that comes entirely out of nowhere. To execute a flawless unexpected ending, you must lay groundwork throughout your book so that the reader can reflect on the plot and go, “ah, but of course!”

5. Tied Ending

Much of storytelling is cyclical. Sometimes it’s a metaphorical return home, such as in the classic story structure of The Hero’s Journey. In other cases, the cycle is quite literal — the story ends where it began.

Example: Erin Morgenstern uses this ending in her book The Night Circus , where she tells of a duel between two magicians that takes place within Le Cirque des Rêves , a traveling circus and, arguably, a character on its own.

Widget takes a sip of his wine and puts his glass down on the table. He sits back in his chair and steadily return the stare at him. Taking his time as though he has all of it in the world, in the universe, from the days when tales meant more than they do now, but perhaps less than they will someday, he draws a breath that releases the tangled knot of words in his heart, and they fall from his lips effortlessly. ‘The circus arrives without warning.’

With what may be the most famous lines of the book, “The circus arrives without warning,” this novel closes the characters’ storylines the same way the book begins. In both cases, the words are used to start telling a story; in the beginning, it serves as an introduction to the book, the words filled with wonder and expectation. In the end, it serves as a resolution, the words filled with hope for those who remain. Additionally, Morgenstern later uses a few more pages to finish the second-person narrative of the reader’s own visit to the circus, effectively ending the novel with the same POV that it began.

Why might you use a tied ending? More common in literary fiction, a tied ending can help give you a sense of direction when writing your book — after all, you are ending the same way you began. But don’t think that this makes writing your ending easier. On the contrary, it is up to you to give greater depth to those repeated actions and events so that, by the end, they have a completely different feel.

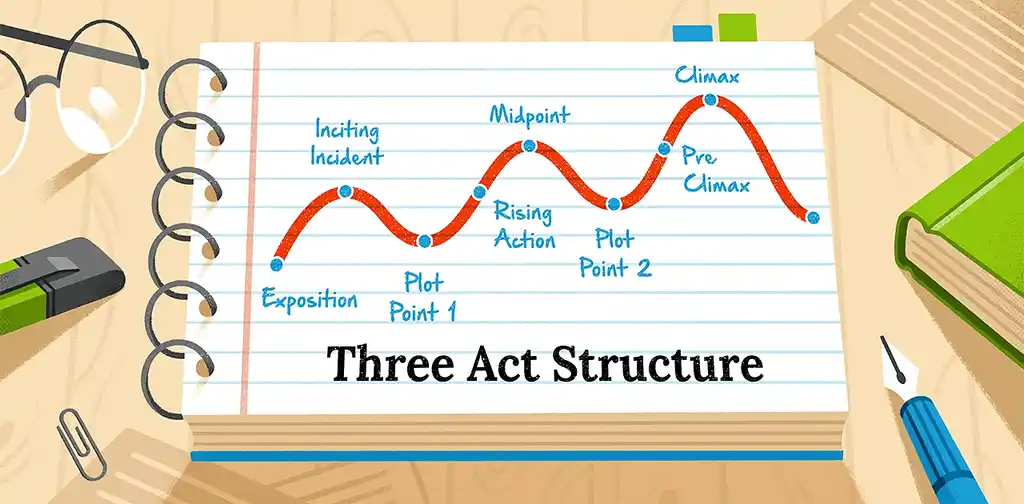

How to Plot a Novel in Three Acts

In 10 days, learn how to plot a novel that keeps readers hooked

6. Expanded Ending

Also known as an epilogue (find out more here ), this type of ending describes what happens to the world of the story afterward in a way that hints at the characters' fates at some point in the future.

Example: In Markus Zusak’s The Book Thief , Death himself narrates the story of a young girl living in Nazi Germany. In his four-part epilogue, Zusak gives the reader an insight into what happened to Liesel after the bombing, her adult life, and even her death.

All I was able to do was turn to Liesel Meminger and tell her the only truth I truly know. I said to the book thief and I say it now to you. *** A LAST NOTE FROM YOUR NARRATOR*** I am hunted by humans.

Instead of going into great detail, Zusak uses short chapters that feel more like sneak peeks into her life. Additionally, it serves the purpose of joining Liesel, the main character, with the narrator, Death, and allowing them to converse on more equal terms.

Why might you use an expanded ending? If you need to tie up loose ends but could not do it within the actual story, then this is the ending for you. However, it should not replace a traditional ending or be used to compensate for a weak ending. Instead, it should give further insight into the characters and give a resolution to the readers.

Now that you understand what kind of endings there are, let’s start thinking about how to create them for yourself.

How to end a story in 7 steps

To help you create a story ending that is unexpected and satisfying, we've turned to the professional editors on Reedsy and asked for their top tips on wrapping up your book.

How to end a story:

- Find your ending in the beginning

- Completion goes hand-in-hand with hope

- Keep things fresh

- Make sure it’s really finished

- Last impressions matter

- Come full circle

- Leave some things unsaid

1. Find your ending in the beginning

While your story may contain several different threads and subplots, all books are going to have a central question that’s raised by the opener. Who killed the boss? Will our star-crossed lovers end up together? Can a rag-tag group of heroes really save the world? Is there meaning to a middle-class existence? Can this family’s relationship be saved?

Your central question is the driving force of what will happen in the plot, so make sure you settle it by the time the book ends. Even if your hero's story continues in a sequel, you’ll want each book to have a central question and a resolution for them to feel complete.

2. Completion goes hand-in-hand with hope

Literary agent Estelle Laure explains that a great ending is one that gives the reader both a feeling of completion and hope.

“You have to assume the character has gone through hell, so let them see something beautiful about the world that allows them to take a breath and step into the next adventure. Even your ending should leave your reader dying for more. They should close the book with a sigh, and that’s the best way I know how to get there. This is, after all, a cruel but wondrous life.”

MEET EDITORS

Polish your book with expert help

Sign up, meet 1500+ experienced editors, and find your perfect match.

3. Keep things fresh

This is good advice for every stage of writing, but perhaps nowhere is it more important than the ending. While there are certain genres where a type of ending is expected (romances should end with a happily ever after, mysteries with identifying the killer), you don’t want people to be able to see everything coming from miles off. So even if the payoff from the big resolution is expected, as the writer, you’ll want to think hard to find ways to keep things fresh and interesting. To achieve this, try to dig deeper than your first impulse because chances are, that’s also going to be your audience’s first impulse as well. You don’t necessarily need to subvert that expectation, but it will give you some hints as to what most people think will happen.

4. Make sure it’s really finished

To create a satisfying ending, close your book with purpose.

As Publishing Director of Endeavor Media, Jasmin Kirkbride’s biggest tip is to make sure you follow the rule of Chekhov’s Gun.

“Every subplot and all the different strands of your main plot should reach satisfying, clear conclusions. If they are meant to be left ambiguously, ensure your reader knows this, and create something out of that uncertainty.”

FREE RESOURCE

Get our Book Editing Checklist

Resolve every error, from plot holes to misplaced punctuation.

5. Last impressions matter

In some ways, the final line of a story is even more important than the first one. It’s the last impression you’ll make in your reader’s mind, and the final takeaway of the whole book. Hone in on what kind of emotions you’d like your reader to feel as they close the book, and ask yourself what kind of image or concluding thought would best convey that. Not sure what that should be? Try looking at your book’s theme! Often the final image is the summation of everything your theme has been building.

6. Come full circle

Editor Jenn Bailey says that a good ending brings the book’s internal and external story arcs to a rational conclusion.

“You need to come full circle. You need to end where you began. You need to take the truth your main character believed in at the beginning of the story and expose it as the lie that it is by the end. In your ending, the main character doesn’t have to get what they want, but they do have to get what they need.”

For more about character arcs, check out this post !

7. Leave some things unsaid

There’s a balance to endings — too little resolution and your book will feel rushed and unsatisfying, but too much and the resolution (dénouement) starts to drag. In general, though, you want to keep things brief, especially if you want room for an epilogue. It’s okay to trust your readers to reach some conclusions on their own, rather than spending whole chapters making sure every question you raised is answered. But, if do you really want everything tied off, consider moving the resolution of some of your subplots to just before the climax . This avoids jamming everything into the last five pages, allowing your subplots space to breathe.

As we have seen, there are many methods for ending stories! However you decide to finish your novel, there is one thing that you should always keep in mind: take account of the story that came before and give it the ending that it needs, not the one you think readers want, and it will be satisfactory for all.

Continue reading

Recommended posts from the Reedsy Blog

100+ Character Ideas (and How to Come Up With Your Own)

Character creation can be challenging. To help spark your creativity, here’s a list of 100+ character ideas, along with tips on how to come up with your own.

How to Introduce a Character: 8 Tips To Hook Readers In

Introducing characters is an art, and these eight tips and examples will help you master it.

450+ Powerful Adjectives to Describe a Person (With Examples)

Want a handy list to help you bring your characters to life? Discover words that describe physical attributes, dispositions, and emotions.

How to Plot a Novel Like a NYT Bestselling Author

Need to plot your novel? Follow these 7 steps from New York Times bestselling author Caroline Leavitt.

How to Write an Autobiography: The Story of Your Life

Want to write your autobiography but aren’t sure where to start? This step-by-step guide will take you from opening lines to publishing it for everyone to read.

What is the Climax of a Story? Examples & Tips

The climax is perhaps a story's most crucial moment, but many writers struggle to stick the landing. Let's see what makes for a great story climax.

Join a community of over 1 million authors

Reedsy is more than just a blog. Become a member today to discover how we can help you publish a beautiful book.

How should you end your book?

Take our 1-minute quiz to find the perfect ending for your book.

1 million authors trust the professionals on Reedsy. Come meet them.

Enter your email or get started with a social account:

- Testimonials

How to end a narrative essay

One way to end a narrative is to look to the future . When J.K. Rolling ended her final Harry Potter book, she skipped forward 20 years to show a new generation of students—Harry’s, Ron’s and Hermione’s kids—heading off to Hogwarts School. This ending of the series reminds readers of the beginning of the series when Harry, Ron and Hermione first headed to Hogwarts. The author takes us full circle, back to the beginning, but not the same beginning.

Another way to end a narrative is to stay in the present time of the stories but have a final scenes which leave the reader with an important emotion . That emotion could come from a single image, the last image of the story. Maybe your babysitter has worked really hard to care for a cranky toddler. The babysitter leaves, exhausted and thinking she will never return. But as she looks back, she sees the toddler looking out the window, smiling and waving.

Still another way to end is with action , as if, on to the next adventure. Superman stories often end this way, with Superman solving a problem, and then flying off. We assume he is off to solve another problem, but his real reason for leaving is that the story is done, and the writer needs to find a way to end it.

I have had some students end their stories with cliff-hangers , scenes where something awful happens, and we, the readers, of course want to know how the disaster is resolved. But all we read is “To be continued.” This is really not an ending but a way of pausing when a student is tired or out of ideas. Don’t use this kind of ending or your audience will be disappointed.

If you have used dialog in your narrative, then ending with dialog (or the thoughts of a character ) makes sense. But the dialog should not be preachy or try to tie up loose ends. Instead, use dialog to create a mood. That mood becomes the lasting impression which the reader has.

Do you need to explain everything at the end? No. If the details are not important, let the reader guess at them. That’s part of the fun for the reader.

Think about what mood or question you want your audience to dwell on as they finish your narrative. Then figure out a good way to convey that idea. If you do, your ending will be satisfying.

Share this:

- Click to share on Facebook (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Twitter (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

What's your thinking on this topic? Cancel reply

One-on-one online writing improvement for students of all ages.

As a professional writer and former certified middle and high school educator, I now teach writing skills online. I coach students of all ages on the practices of writing. Click on my photo for more details.

You may think revising means finding grammar and spelling mistakes when it really means rewriting—moving ideas around, adding more details, using specific verbs, varying your sentence structures and adding figurative language. Learn how to improve your writing with these rewriting ideas and more. Click on the photo For more details.

Comical stories, repetitive phrasing, and expressive illustrations engage early readers and build reading confidence. Each story includes easy to pronounce two-, three-, and four-letter words which follow the rules of phonics. The result is a fun reading experience leading to comprehension, recall, and stimulating discussion. Each story is true children’s literature with a beginning, a middle and an end. Each book also contains a "fun and games" activity section to further develop the beginning reader's learning experience.

Mrs. K’s Store of home schooling/teaching resources

Furia--Quick Study Guide is a nine-page text with detailed information on the setting; 17 characters; 10 themes; 8 places, teams, and motifs; and 15 direct quotes from the text. Teachers who have read the novel can months later come up to speed in five minutes by reading the study guide.

Post Categories

Follow blog via email.

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address:

Peachtree Corners, GA

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

The Art of Narrative

Learn to write.

How to End a Story

Some people say the ending is the most important part of a story. I’m inclined to agree. Mess up the ending, and your reader will feel cheated. Like they’ve wasted their time. The greatest premise in the world won’t mean squat if you can’t stick the landing. That’s why we’re talking about how to end a story!

Listen to this article:

How you end your story is really, really important. But, I didn’t have to tell you that, did I? Because we’ve all experienced stories with bad endings- *cough* Game of Thrones- and we know that a bad ending can sour a reader’s entire experience of a story.

That’s why you need to start your writing process with a story ending in mind. Can the way you end your story change and evolve during the writing process- Sure! But, writing a story and expecting the perfect ending to pop out of your imagination at just the right time is a mistake.

And before you say it, I know a lot of famous and successful writers are also panters, or writers who don’t outline their story but develop it as they go. But, if your just starting out on your writer’s journey, writing by the seat of your pants may not be the best option.You need to know what makes a good story ending before you can intuitively write one without thinking. But, I’m getting to my first tip which is-

Start with the End in Mind

There are two kinds of writers: Plotters and Pantsers. Pantsers write stories “by the seat of their pants” without plotting or outlining. And plotters write stories with good endings… Okay, that’s not fair. There are some very successful pantsers out there like Stephen King and Margaret Atwood.

But, great pantsers are a rare breed, so it’s safer, for most of us, to plot.

There’s an inherit benefit to plotting. Having an ending in mind will keep your writing focused.

The ending and plot points may change along the way, and that’s fine. But a good outline is like a roadmap . You might not need it, but it’s sure nice to have when you’re lost!

Avoid Cliches

Does your story end with your hero out-skiing his rival, winning the girl and live happily ever after? Or worse, does they wake up and realize that it was all a dream ? Then you’ve got a problem, my friend. But, don’t worry! The problem isn’t that you’re an unimaginative writer. You just need some inspiration.

Cliched writing usually means you haven’t done enough research. But how do you research for a fictional story? Start by reading non-fiction. After all, the best stories are rooted in reality.

Writing a police procedural? A perfect ending could be in the pages of your local police blotter. Working on a story about time travel? Then it’s time to read up on black holes, quantum physics, and maybe a little history.

Or delve into your own life experience to find your stories perfect ending. How have the major conflicts of your life resolved? Maybe you’re thinking- allmy conflicts ended terribly . And, that’s okay. Conflict isn’t always resolved positively in reality, and the same can be true for your story.

Not every ending is required to be happy.

Go Back to the Beginning

Matthew McConaughey once said that “life is a flat circle.” Well, so are the best stories. Good endings will often take the reader back to where the story began . Good writers have a way of tying everything up with a nice bow.

Take Peter Jackson’s movie adaptation Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. Our adventure begins in The Shire. Over the next three movies, we travel across Middle Earth, defeat Sauron, and destroy the One Ring. But in the end, we’re right back at The Shire where we started.

Or how about Citizen Kane, one of the greatest films of all time. Also a great example of a nonlinear narrative . We start with the cryptic whisper of a dying man- “Rosebud.” We don’t discover the meaning of “Rosebud,” until the movie’s final frame- a huge emotional payoff. Connecting your story’s ending to it’s beginning will give your reader a satisfying sense of closure.

Keep it Tight

The final act of your story is not the place to introduce new characters, plot threads, or story arcs. The final act is about ending your story, so wrap up those plots, and kill those characters.

Okay, you don’t have to kill all your characters. But remember final acts are like group therapy. They’re about one thing- resolving the conflict. A lot of new information will get in the way of that sweet, sweet resolution.

And another thing!

If your planning a startling revelation as a kind of stinger to end your novel on then you need to foreshadow that revelation early on in the book. Your character shouldn’t, out of nowhere, be really good at karate because that’s the only way you can imagine them defeating the Big Bad .

Let the Hero Take the Wheel

The final act of the story is about your protagonist finally taking charge of her situation. She may have been lost in the first act. Her friends may have saved her butt in the second act , but by the time of the climax, she needs to be kicking but and taking names (but make it too easy). Point is, she should be the one doing the saving!

Your hero should take the lead in the final act. Which brings me to my final tip…

Demonstrate Growth

Throughout a story, protagonists should transform into new, better versions of themselves. It’s not enough that they conquer the villian. They should also prove that they’ve earned their victory. So while they’re vanquishing that diabolical villain they should also defeat their inner demons as well! That’s how you make a dynamic character !

Okay, there are a few tips to help you write a perfect ending. Remember, the ending is the most important part of your story. Don’t screw it up. Otherwise, you’ve wasted everyone’s time. Don’t do that!

So, uh… That’s pretty much it.

If you like what you read, please scroll down and hit one of those share buttons at the bottom of the page. That’s the easiest and best way to support the blog. Thanks!

Continued Reading on Plot Structure

Story Engineering by Larry Brooks is a go-to resource when it comes to all things plot related. Larry Brooks gives you practical, actionable advice on how to structure your story. I can’t recommend it enough.

Plot & Structure has consistently been one of the top selling books on the craft of fiction writing. From story idea to strong plot line, this book will show you how to write a solid novel, every time out. You will never have a structural weakness again. These principles will free you to add your talent and voice in the most successful form possible.”

– JamesScottBell.com

The Third Act: How to Write a Climatic Sequence- Well-Storied

The Payoff- KM Allan

This post contains affiliate links to products. We may receive a commission for purchases made through these links

Published by John

View all posts by John

24 comments on “How to End a Story”

- Pingback: How to End a Story from the Maltese Tiger Blog | Author Don Massenzio

Excellent tips! 🙂 Sharing…

Thanks Bette! I appreciate it!

A pleasure. 🙂 Have a great week!

- Pingback: 30 Sites that Pay Writers - the maltese tiger

Many thanks – just what I needed to finish writing the final chapter of my first novel. Excellent advice and so helpful…

Amazing! Glad the article helped. That’s what I like to hear! Congratulations on your novel!

- Pingback: 30 Sites that Pay Writers | Nicholas C. Rossis

- Pingback: Creating a Subtext - the maltese tiger

- Pingback: Creating a Subtext – From the Maltese Tiger Blog | Author Don Massenzio

Love these tips and the movies you’ve chosen as the examples. Really brings the points home.

Thanks KM! Hope you don’t mind me dropping your link at the bottom. I wrote this a while ago, but wanted to update it. Now, the fonts are all messed up. I suck at web design. Whatever…

Not at all, John, link away 😊. I was going to say I like the new look/feel of your blog. It’s great! Doesn’t look messed up to me.

Thanks! Your redesign looks great as well!

- Pingback: How to End a Story - The Art of Narrative - Lacrecia’s books

- Pingback: How to Write a Plot Twist - The Art of Narrative

- Pingback: Best Websites and Resources for Writers 2020 - The Art of Narrative

- Pingback: 🖋 Writing Links Round Up 6/8 – B. Shaun Smith

Thank you for the information. Nice tips..have a good day.

- Pingback: 5 Storytelling Skills Every Writer Should Master - The Novel Smithy

- Pingback: How to Use Somebody Wanted But So Then - The Art of Narrative

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Copy and paste this code to display the image on your site

Discover more from The Art of Narrative

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing group!

How to End a Story: 7 Different Kinds of Endings

by Fija Callaghan

Fija Callaghan is an author, poet, and writing workshop leader. She has been recognized by a number of awards, including being shortlisting for the H. G. Wells Short Story Prize. She is the author of the short story collection Frail Little Embers , and her writing can be read in places like Seaside Gothic , Gingerbread House , and Howl: New Irish Writing . She is also a developmental editor with Fictive Pursuits. You can read more about her at fijacallaghan.com .

Imagine this: you’re reading a thrilling, breakneck story full of deep thematic resonance and memorable characters. The plot is powering towards its climax, and you’re clutching the pages as the clock beside your bed careens past one o’clock in the morning. And then—! The book suddenly grinds to a puzzling, disappointing, and ultimately unsatisfying halt because the writer didn’t know how to end a story the right way.

Don’t be that writer.

Knowing how to end a story is one of the most important, yet undervalued, skills in a writer’s toolbox. Let’s look at why a satisfactory ending matters and how to find the right ones for your own stories.

Why is the ending of a story important?

The ending of a story matters because it’s the final note that the reader will walk away with. Your story’s ending shows the reader what to feel as they leave your story world behind and return to the real one, what lessons to learn from and incorporate into their own lives, and what to expect from you, the author, as they wait impatiently for your next book.

Knowing how to write a good story ending is the key to “closing the deal” with your reader.

How are story endings connected to genre?

You might have noticed that some of your favourite books end in the same way. If you read a lot within the same genre, you might even be able to predict the ending before it happens! This is because certain literary genres come with predetermined expectations based on the patterns we see most often.

You don’t have to use the classic ending for your own story, but it’s good to have an idea of what your readers will be expecting when they open your book. Familiarising yourself with their expectations will also help you subvert them in new, creative ways.

Here are some of the classic literary genres you’ll see most often, and the endings that usually go with them.

1. Romance endings

In romance novels, we’ve been conditioned to look for happy endings. From the opening scene through all the clever plot twists and machinations, everything in the book is working towards a happily ever after for the two romantic leads.

The protagonists go through their own character arcs as they discover more about themselves and their relationship with the world, but ultimately they’ll end up doing pretty okay by the story’s conclusion.

This doesn’t mean you can’t challenge genre norms and give your main characters a bittersweet ending or leave their love story unresolved; however, in this case you might end up moving away from writing a traditional romance and towards something more like literary fiction (we’ll look at that below too).

2. Mystery endings

The golden rule of mystery novels is “expect the unexpected.” If the story you’re writing follows a clear, logical path from start to finish and lays everything out for the reader, they may come away with a frustrating experience. Mysteries and thrillers will be filled with plot twists that keep readers turning pages to find out who done it, or why.

These types of stories aren’t a great match for open or unresolved endings. Even though the reader wants to be surprised, they also want to know exactly what happened and what’s going to happen next. Did the murderer go to prison, escape, or die trying? Did the protagonist uncover the truth and bring the criminal to justice?

There is no right or wrong answer, but the answer does need to be a definitive conclusion rather than something left to interpretation.

3. Horror endings

Horror novels are more flexible than mysteries. They might have a happy or unhappy ending; they might answer all the remaining questions, or they might leave some open to keep the reader mulling things over after the book is closed.

Horror stories are particularly well-suited to ambiguous or unresolved endings. You’ll probably recognise this in some of your favourite horror films or TV series finales:

The heroes finally defeat the monster and celebrate with an extra-cheesy pizza and plans for the future they now have. In the corner of the screen, the dirt where the monster was buried begins to shift ominously. Roll credits.

By leaving a few lingering questions, you make a lasting impression on your reader.

4. Tragic endings

Tragedies are defined by their sad ending. Unlike mysteries, which are filled with twists and turns, the tragic ending should feel inevitable; the hero, through their own weaknesses or choices, brought it on themself.

Tragedies have fallen somewhat out of fashion in contemporary literature (probably because they’re kind of a downer to read), but Shakespeare loved writing them. These types of stories are designed to teach us something about human nature and what happens when we let our weaknesses control us.

Tragedies might use a resolved ending or an implied ending, leaving the final conclusion of the story to happen off the page.

5. Literary endings

Really, all fiction is “literary.” But when we say “literary fiction,” we usually mean books that are marketed as “contemporary,” “women’s fiction,” or realistic historical fiction. This type of story tends to be introspective and thematic, and is suited to both long-form novels and short stories.

In a short story, you generally won’t have the space to flesh out an ambiguous or unresolved ending. These are best suited to a circular ending—for instance, if your story begins and ends in the same location (we’ll take a closer look at circular endings below!)—or a clear ending that show how your main character has undergone some personal transformation.

If you’re writing a novel of literary fiction, you have more room to play with ambiguous, unresolved, or extended endings—so long as they support the broader theme you’re trying to communicate through the work.

We’ll look at all of these types of endings in more detail below!

What about sci-fi and fantasy?!