VCE Study Tips

English Language

Private Tutoring

Only one more step to getting your FREE text response mini-guide!

Simply fill in the form below, and the download will start straight away

English & EAL

June 26, 2019

Want insider tips? Sign up here!

Go ahead and tilt your mobile the right way (portrait). the kool kids don't use landscape....

Updated on 11/12/2020

Nine Days by Toni Jordan is currently studied in VCE English under Area of Study 1 - Text Response. For a detailed guide on Text Response, check out our Ultimate Guide to VCE Text Response .

- Main Characters

- Themes, Ideas and Values

- Literary Devices

- Essay Topics

Essay Topic Breakdown

1. summary .

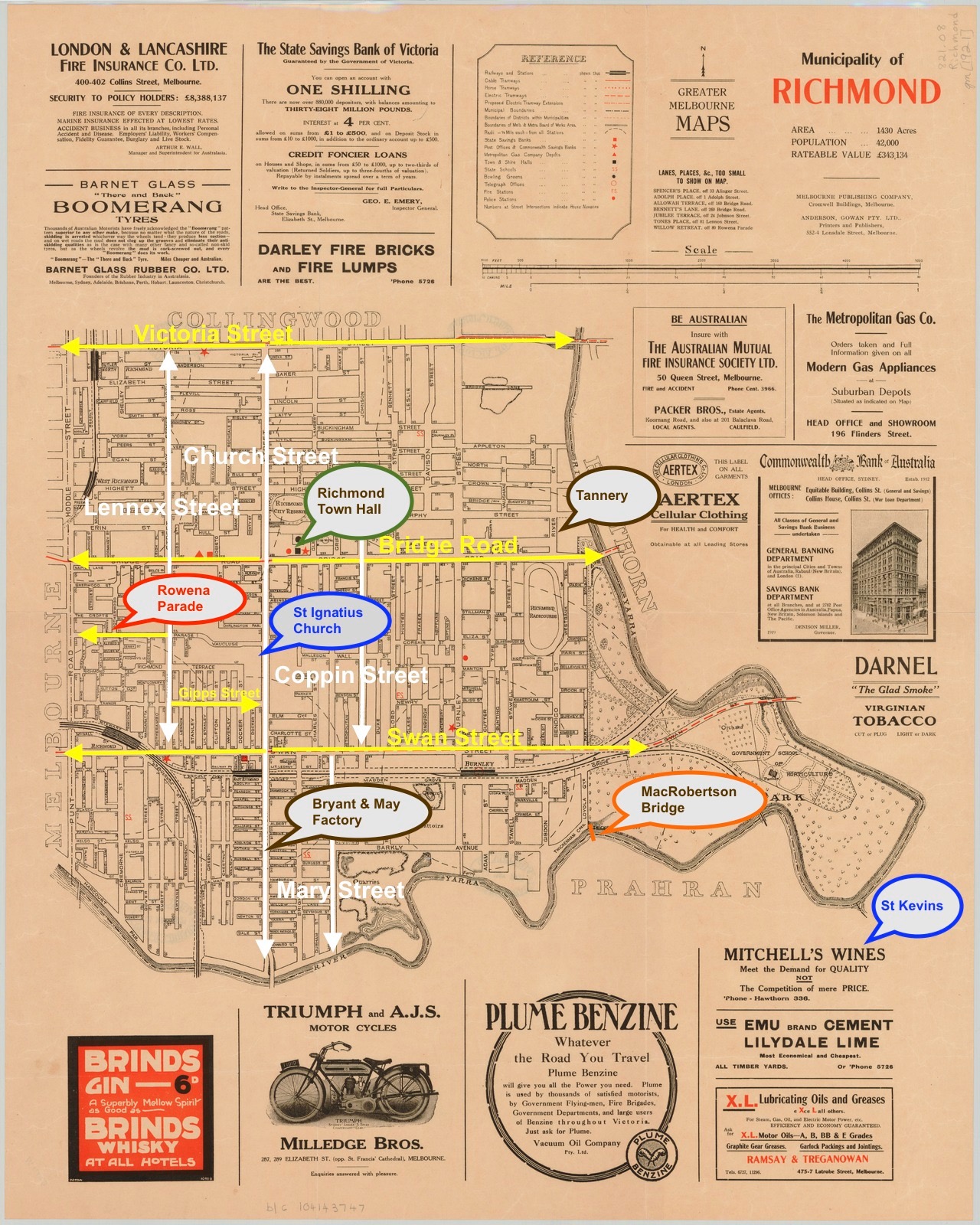

Jordan’s novel traces the tumultuous lives of the Westaway family and their neighbours through four generations as they struggle through World War II (1939-45), the postwar period of the late 1940s and 50s, the 1990s and the early 2000s. Composed of nine chapters and subsequently nine unique perspectives of life, their family home in Rowena Parade, Richmond, becomes the focal point for Jordan’s exploration of femininity, masculinity, family and Australian society.

2. Main Characters

Kip westaway.

'Mr. Husting always says first impressions count' (p. 5)

'Mr. Husting holds his other hand out flat and instead of an apple there’s a shilling.' (p. 6)

'I own the lanes, mostly. I know the web of them, every lane in Richmond.' (p. 21)

'When they put me in the grave, I know what it’ll say on the stone, if I get a stone, if they don’t bury me like a stray cat at the tip' (p. 29)

'I didn’t say goodbye to Dad! On account of a book' (p. 158)

'This photo won’t be out of my sight from now on. You’ve given me my sister back, Alec.' (p. 260)

Francis Westaway

'THE SHADOW CANNOT BE DEFEATED!' (p. 145)

'The toughest gang in Richmond! And they want me, Francis Westaway!' (p. 155)

'I see a purple jewel hanging on a gold chain. It’s a beaut, the prettiest thing I’ve ever seen…There’s no way I’m sharing this. It’s mine.' (p. 174)

'Do you understand how sensitive a reputation is? It’s up to me to be respectable. I’m the eldest. It’s my responsibility.' (p. 200)

Connie Westaway

'Ma sitting with her dress lifted up to her face, Connie on her knees beside her, holding her arms, cooing soft like Ma is a baby.' (Kip, p. 35)

'We women do what’s expected. You [men] can do almost anything you care to think of.' (p. 280)

'It seems that all my life I’ve had nothing I’ve desired and I’ve given up having desire at all. Now I know what it feels like to want and I will give anything to have it' (p. 285)

'I thought we’d have more time than this. We’ve only just made it.' (p. 290)

Jean Westaway

'Those moments, when [Kip] reminds me of Tom. I have to leave the room. The fury rises up my legs and up my body like a scream and it’s all I can do not to let it out.' (p. 212)

'We all die alone' (p. 212)

'This is not how I imagined it to be. Children. Mothering.' (p. 212)

'And for things like this, for girls like Connie and saving her future, there is a respectable woman who runs a business in Victoria Street' (pp. 221-222)

'I’d never of done it with boys but Connie, she was different.' (p. 239)

'we’re respectable people.' (p. 218)

Tom Westaway

‘Kipper’s old man…dropped off the tram in Swan Street somewhat worse for a whiskey or three and hit his head. Blam, splashed his brains all over the road. A sad end.’ (Pike, p. 24)

‘As a girl I had plenty of suitors, but none like Tom. Best behaviour in front of my father, children all brought up in the church by him.’ (p. 212)

Stanzi Westaway

‘The parcel is for Stanzi: inside is an old-fashioned coin, dull silver, with a king’s head on one side. It has a silver chain threaded through a hole in the middle. Stanzi looks like she’s about to cry.’ (Alec, p. 254)

‘She doesn’t mean to be hurtful. She is worries for me, that’s all…if she really thought I was in terrible trouble, she would be gentler.’ (Charlotte about Stanzi, p. 126)

‘the oblivious insouciance of the entitled’ (p. 51)

Charlotte Westaway

‘I say the question over and over: should I keep the baby?’ (p. 142)

‘The herbs are evidence of an understanding of our place in the universe…an acknowledgement of the delicate balance in our bodies…’ (p. 116)

‘There was only one place I could go: my sister’s’ (p. 124)

‘They contain all the hopes of the human spirit, all the refusal to quit, to keep believing people can feel better’ (p. 116)

Alec Westaway

‘Yet here I am. Away from home in a world of strangers. Alone. Forgotten.’ (p. 241)

‘This waiting for my life to start, it’s driving me mental.’ (p. 244)

‘I don’t sketch. Instead I concentrate on the scene the scene in front of me so I can remember it later.’ (p. 251)

Libby Westaway

‘All the things I remember, everything about my life, our family, my childhood: it’s all real because Libby knows it too.’ (Alec, p. 273)

Jack Husting

‘I can see both sides.’ (p. 80)

‘Just let me kiss you, Connie. I’d die a happy man.’ (p. 284)

Ava and Sylvester Husting

‘If we have to send boys to fight…it’s layabout boys with no responsibilities, the Kip Westaways of the world, who ought to be going.’ (Ava, p. 102)

‘That shilling. Our little secret. Gentlemen’s honour.’ (Sylvester, p. 8)

Annabel Crouch

‘You’re a good girl, Annabel.’ (Mr. Crouch, p. 177)

‘I’d like to compliment their dresses, but I don’t know what to say.’ (p. 190)

‘He is killing himself, I know that. I won’t have him for much longer.’ (Annabel, p. 207)

‘No mother, no brothers. Working your youth away, looking after an old man.’ (p. 179)

3. Themes, Ideas and Values

‘Family house, family suburb, family man’ (Charlotte about Kip, p. 140)

‘Stuck here…looking after your old man. You should have a family of your own by now.’ (Mr. crouch to Annabel, pp. 178-179)

The theme of family is a recurring one that develops over time. Jordan’s inclusion of other families such as the Crouches, the Churches, the McCarthys and the Stewarts stands in contrast to the Westaways. The juxtaposition of family life in this way allows the reader to see how such factors like wealth, class and reputation can affect the family dynamic especially within the war period. The idea of family is strained by the pressures of war because with many families' sons and husbands away it left the other family members to adopt other roles - not only physically, but the conventional emotional roles of traditional families of the time are redistributed, specifically within the Westaway household. Jordan postulates that the role family plays in providing emotional/physical support is of far greater importance than the necessity to abide by society's idea of what family should look like.

Women and Reproductive Rights

‘I tell her about shame and the way it’s always the women who wear it. I spare her nothing. I say loose women and no morals and I say bastard and I say slut.’ (Jean, p. 220)

‘You don’t have to have it, you know.’ (Stanzi, p. 132)

‘Your body, your choice…That’s what our feminist foremothers fought for’ (p. 134)

‘What if he wanted to know his child, doesn’t he have the right?’ (pp. 133-134)

Jordan highlights the controversial issues of premarital sex, abortion and the rights of women within the mid 20th and early 21st century. Indeed, it is this theme of women that becomes inextricably linked with the effect of a damaged reputation. When Connie falls pregnant, Jean implores that she has an abortion, in secret of course, in order to preserve her and her family’s reputation within the small community. The issue of abortion is later revisited when Charlotte becomes pregnant in the 1990s, where the contrast between the time periods becomes evident; while unplanned pregnancy is greatly stigmatised in the 1940s, the 1990s offers Charlotte a far wider array of options. It is through Jordan’s depiction of the two cases – Connie’s horrific backyard abortion, and Charlotte’s adjustment to parenthood – that she suggests the perceptions and attitudes towards morality, reputation and women have shifted over time, emphasising the importance of reproductive rights in the development of women.

Masculinity

‘I remember coming home from school once, crying. I would have been around six or seven. I was picked last for some team. That was me, the kid without a father.’ (Alec, p. 262)

‘”Westaway,” Cooper says. “Get in. For once in your life, do not be a pussy.”’ (p. 267)

Within the parameters of her text, Jordan articulates how men conform or reject masculine tropes in an effort to fit into society. Toughness, bulling and unsavory activity are presented as the characteristics of a man through such depictions of Mac and his gang. In its connection to the war period, the novel partly focuses on the notion that in order to be classified as a man he must first go through struggle and hardship as presented in the group of strangers taunting Jack, ultimately bullying him into certain ideals of masculinity which prove toxic and consequential - Jack dies as a result. It is Jordan who advocates for a balanced personality of both ‘masculine’ and 'feminine’ characteristics as suggested in the character development of Kip; evolving, learning and devising a true meaning of what it means to be a man outside of its conventional brutality.

Attitudes Towards Asia

‘She is with a customer or sweeping the floor with a broom made from free-range straw that died of natural causes or singing Kumbaya to the wheatgrass so it is karmically aligned.’ (Stanzi, p. 50)

‘The fear of the Nips coming made him a better man.’ (Annabel, p. 178)

‘always wanted to go to India [to study yoga] at a proper ashram.’ (pp. 132-133)

‘She makes her eyes go big and round like some manga puppy’ (p. 264)

Through both overt and subtle language, Jordan makes reference to the attitudes towards Asia which were prevalent at the time, specifically within the war period that saw many Australians ‘[fearing] the nip’. The derogative slang used for the Japanese represents a lack of understanding and fear (the bombing of Darwin and attack on Sydney left many feeling particularly vulnerable to the Japanese). Exacerbated by the fact that Japanese culture was not widely understood and was often misrepresented, the Japanese were stereotyped as brutal and inhuman. Over the course of the novel, attitudes towards Asia dramatically shift especially within the early 1990s of Stanzi and Charlotte's generation. The philosophical ideas of the east are often referenced by characters like Charlotte as she draws on them to make sense of her own complex life. The novel sees another shift in ideology represented through Alec as his generation's perception turns to a more commercial view. Asian culture has earned a place in mainstream media and western life without such gruesome and violent connotations as were previously held during the time of World War II.

By the way, to download a PDF version of this blog for printing or offline use, click here !

4. Literary Devices

- Throughout her perspective driven text, Jordan makes many references to classic novels which help create a literary context for the narrative and lend themselves to the evolution of the characters throughout the course of the text.

- Alexandre Dumas’ The Three Musketeers – Kip’s characteristic trait of heroism when he sees the gang waiting for him and says ‘on-bloody-guard, d’Artagnan’ (p. 22)

- Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations and Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn – both coming-of-age stories about young men struggling within a tough world, only getting by on their wits and strength.

- Brontë sisters' Jane Eyre and Wuthering Heights – their reference is used in discerning a customer’s knowledge on the texts, but reveals only a surface level understanding due to the novels carrying a certain cultural value.

- Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels – referenced by Jack Husting in relation to his adventures in the country. Its use pertains to how Jack feels out of place in his home town after leaving a boy and returning a grown man.

- A historical novel that plays with ideas of placing invented characters into a reconstructed world of the past.

- Uses elements of both realism and impressionism to create the text.

Realist Elements:

- A strong focus on everyday life within a particular society with reference to real historical detail.

- Incorporates a logical and strong foundation of context that can be easily digested and believed by the reader.

- Can use an omniscient narrator (all-knowing).

Impressionist Elements:

- Each chapter offers detail and presents a vivid interpretation of specific events.

- Sensory experiences are emphasised by the use of descriptive and poetic language.

- The linear flow of the narrative is disrupted by its construction in a non-chronological order, thereby forcing the reader to piece the whole narrative together at the end.

- Varied depending on the character’s perspective and time of perspective.

- Language is used to historicise each chapter through use of slang, colloquialisms, formal and proper English.

- The novel revolves around the Westaway’s family home in Rowena Parade, Richmond over the course of four generations.

- Rather than them move or the location change it evolves, paralleling the growth and evolution undergone by each of the Westaway family members.

- Inspired by a photograph in the collection of Argus war photos held at the State Library of Victoria, Jordan uses this image capturing a private and intimate moment to establish the premise for each of the book's chapters.

- Titled Nine Days and composed of nine unique perspectives on life at a given time, Jordan offers insight into the emotional livelihood of each narrator and attaches both intimate and historical significance to their stories.

5. Essay Topics

- Toni Jordan’s Nine Days describes a world in which life in the 1930s and 40s was much harder than life in the 21st century. Do you agree?

- In Nine Days , older Kip’s point of view is very unrealistic. To what extent do you agree?

- Toni Jordan’s Nine Days shows us people can choose whether they end up happy or not. Discuss.

- The mood by the end of Nine Days is ultimately uplifting and positive. Do you agree?

- There is more tragedy in Nine Days than there is joy. To what extent do you agree?

- Nine Days , by Toni Jordan, shows the best and worst of Australian culture. Discuss

- Jordan suggests that appreciation of family is integral to personal happiness. Discuss.

- 'Your body, your choice.' What do the different experiences of Connie and Charlotte reveal about changing societal attitudes towards women?

- There are many characters who are largely hidden figures within the text. What significance is produced by including and excluding different perspectives?

6. Essay Topic Breakdown

Whenever you get a new essay topic, you can use LSG’s THINK and EXECUTE strategy - a technique to help you write better VCE essays. This essay topic breakdown will focus on the THINK part of the strategy. If you’re unfamiliar with this strategy, then check it out in How To Write A Killer Text Response because it’ll dramatically enhance how much you can take away from the following essays and more importantly, your ability to apply this strategy in your own writing.

Within the THINK strategy, we have 3 steps, or ABC. These ABC components are: Step 1: A nalyse Step 2: B rainstorm Step 3: C reate a Plan

THINK How-based prompt: How does Nine Days explore the relationship between the past and the present ?

Step 1: Analyse

This is a ‘how’ essay prompt, so in our planning, we need to identify the ways in which the author accomplishes their task. When analysing your question it is important to know what the question is asking of you, so make sure you highlight the keywords and understand their meaning by themselves and in the context of the question. For example, this question is not just asking about the past and present, but rather the connection between the two - so if you discussed the past and the present separately you wouldn’t be answering the question.

Step 2: Brainstorm

Brainstorming is different for everyone, but what works for me is focusing on the key idea, which here would be the relationship between the past and the present, and listing my thoughts out. Not all the ideas will be as equally relevant/good, but I like to have things written down to then improve or simply not use in favour of other ideas.

Past → Present: Westaway family home, the house changes as the family grows Past → Present: Connie’s tragic abortion compared to Charlotte’s options in the 1990s, women’s rights evolving over time Past → Present: Melbourne becoming more multicultural, Alec’s chapter reveals how Melbourne has changed compared to chapters set in earlier times Past → Present: Kip teaching Alec to cherish those in front of us after seeing Connie’s picture Past → Present: Second World War contrast to 9/11 and war in Afghanistan

Now that I have all my ideas listed out I choose my strongest three to flesh out. There are different things that make an idea strong, but the things I consider are: - Do I have enough evidence to support this idea? - Is the idea substantial enough to turn into a whole paragraph? - Do I have an author’s views and values statement? - Can I include context or metalanguage into this idea?

Using the questions above, I decided to use the following ideas: - Westaway family home, the house changes as the family grows (symbolism) - Kip teaching Alec to cherish those in front of them (focus on characterisation) - Melbourne becoming more multicultural (can talk about historical context)

Step 3: Create a Plan

Contention: Through the use of setting and characterisation, Jordan’s Nine Days reveals how the past and present are interconnected. P1: Westaway home embodying the familial connection P2: The past is not completely separate from the present, it teaches us lessons that are pertinent to contemporary life (Alec) P3: Melbourne becoming more multicultural

If you found this helpful, then you might want to check out our A Killer Text Guide: Nine Days ebook which has an A+ sample essay in response to this prompt, complete with annotations on HOW and WHY the essay achieved A+! The study guide also includes 4 more essay topic breakdowns and sample A+ essays, detailed analysis AND a comprehensive explanation of LSG’s unique BBT strategy to elevate your writing!

Download a PDF version of this blog for printing or offline use

Get our FREE VCE English Text Response mini-guide

Now quite sure how to nail your text response essays? Then download our free mini-guide, where we break down the art of writing the perfect text-response essay into three comprehensive steps. Click below to get your own copy today!

Access a FREE sample of our Nine Days study guide

- Learn how to brainstorm ANY essay topic and plan your essay so you answer the topic accurately

- Apply LSG's THINK and EXECUTE strategy - a clear and proven method to elevate the quality of your Text Response writing

- Includes 5 sample A+ essays with EVERY essay annotated and broken down on HOW and WHY these essays achieved A+

- Think like a 45+ study scorer through advanced discussions like symbols & motifs, views & values and character analysis.

When it comes to studying a text for the text response section of Year 12 English, what may seem like an obvious point is often overlooked: it is essential to know your text . This doesn’t just mean having read it a few times either – in order to write well on it, a high level of familiarity with the text’s structure, context, themes, and characters is paramount. To read a detailed guide on Text Response, head over to our Ultimate Guide to VCE Text Response .

Authors structure their texts in a certain way for a reason, so it’s important to pick up on how they’ve used this to impart a message or emphasise a point. Additionally, being highly familiar with the plot or order of events will give you a better grasp of narrative and character development.

It’s also a good idea to research the life of the author , as this can sometimes explain why certain elements or events were included in the text. Researching the social and historical setting of your text will further help you to understand characters’ behaviour, and generally gives you a clearer ‘image’ of the text in your mind.

The overarching themes of a text usually only become apparent once you know the text as a whole. Moreover, once you are very familiar with a text, you will find that you can link up events or ideas that seemed unrelated at first, and use them to support your views on the text.

For each character , it is important to understand how they developed, what their key characteristics are and the nature of their relationships with other characters in the text. This is especially crucial since many essay questions are based solely on characters.

With all this said, what methods can you use to get to know your text?

Reading the text itself: while this may seem obvious, it’s important to do it right! Read it for the first time as you would a normal book, then increase the level of detail and intricacy you look for on each consecutive re-read. Making notes , annotating and highlighting as you go is also highly important. If you find reading challenging, try breaking the text down into small sections to read at a time.

Discussion: talk about the text! Nothing develops opinions better than arguing your point with teachers, friends, or parents – whoever is around. Not only does this introduce you to other ways of looking at the text, it helps you to cement your ideas, which will in turn greatly improve your essay writing.

External resources : it’s a good idea to read widely about your text, through other people’s essays, study guides, articles, and reviews. Your teacher may provide you with some of these, but don’t be afraid to search for your own material!

Alfred Hitchcock’s classic thriller Rear Window was released nearly 65 years ago. Back then, Hitchcock was a controversial filmmaker just starting to make waves and build his influence in Hollywood; now, he is one of the most widely celebrated directors of the 20th century. At the time of its 1954 release, Rear Window emerged into a world freshly shaken by World War II. The fear of communism riddled American society and Cold War tensions were escalating between the two global superpowers, the USSR and USA. Traditional gender stereotypes and marital roles were beginning to be challenged, yet the ‘old way’ continued to prevail. The culture of the 1950s could hardly be more different to what it is today. Within the Western world, the birth of the 21st century has marked the decline of cemented expectations and since been replaced by social equality regardless of gender, sexual preference and age. So why , six decades after its original release and in a world where much of its content appears superficially outdated , do we still analyse the film Rear Window ?

Rear Window is a film primarily concerned with the events which L.B. (Jeff) Jefferies, a photographer incapacitated by an accident which broke his leg, observes from the window of his apartment. He spends his days watching the happenings of the Greenwich Village courtyard, which enables Jeff to peer into the apartments and lives of local residents. The curiosities which exist in such an intimate setting fulfil Jeff’s instinctual need to watch. The act of observing events from a secure distance is as tempting as reality television and magazines. To this day, these mediums provide entertainment tailored to popular culture. At its roots, Jeff’s role as a voyeur within Rear Window is designed to satisfy his intense boredom in a state of injury. As the film is seen through Jeff’s voyeuristic eyes, the audience become voyeurs within their own right. Until relations between Thorwald and his wife simmer into territory fraught with danger, Jeff’s actions are the harmless activities of a man searching for entertainment.

So, if Rear Window teaches us that voyeurism is a dangerous yet natural desire , does the film comment on the individuals who consent to being watched? Within Greenwich Village, Jeff’s chance to act as an observer is propelled by the indifference of those he observes. Almost without exception, his neighbours inadvertently permit Jeff’s eyes wandering into their apartments by leaving their blinds up. The private elements of others’ lives, including their domestic duties, marital relations and indecencies, are paraded before Jeff. Greenwich Village is his picture show and its residents willingly raise the stage’s curtains . This presentation of Hitchcock’s 1954 statement remains relevant today. Jeff’s neighbours’ consent to his intrusion into their lives bears striking similarities to current indifference. The prevalence of social media enables information to be gathered as soon as its users click the ‘Accept Terms & Conditions’ button. Rear Window is a commentary on social values and provokes its audience to examine habits of their own, especially in a world where sensitive information is at our fingertips. Just as Hitchcock’s 1954 characters invite perversive eyes to inspect their lives, society today is guilty of the same apathy .

The characters of Hitchcock’s thriller are a pivotal element of the film’s construction. They add layers of depth to the text and fulfil roles central to the plot’s development. One of Hitchcock’s fundamental directorial decisions was leaving multiple characters unnamed – within Greenwich Village alone, we meet Miss Lonelyhearts, Miss Torso and Miss Hearing Aid. The stereotypical nature of these labels, based on superficial traits that Jeff observes from his window, exemplifies the sexism prevalent in the 1950s. Jeff’s knowledge of these women is limited to such an extent that he does not know their names, yet considers himself qualified enough to develop labels for each of them. The historical background of stereotypes is imbedded within Rear Window and shares vast similarities with the stereotypes we recognise today.

Hitchcock’s 1954 thriller Rear Window portrays a little world that represents the larger one . Its themes, primarily voyeurism, and character profiles illustrate Hitchcock’s societal messages and provide a running commentary on issues which govern America during the 1950s. In the six decades since the film’s release, the Western world has undergone significant developments both socially and culturally. L.B (Jeff) Jefferies’ perception of women and married life is inconsistent with the relations between men and women that we observe today. Regardless, the timeless views that Hitchcock’s conveys through Rear Window continue to speak volumes about our society. Jeff’s voyeurism, which comprises much of the film’s major plotline, is a channel for Hitchcock to comment about the instinctual desire for individuals to observe others. Additionally, Hitchcock delves into the flip side of this matter, presenting the theory that those he watches are just as guilty of allowing his intrusion into their private lives. Apathetic mindsets in today’s digital world are responsible for the same indifference that Hitchcock explores within his film. Let’s not forget the sexist stereotypes that Jeff develops to label certain women within Greenwich Village. Miss Lonelyhearts, Miss Torso and Miss Hearing Aid are all victims of Jeff’s narrow mindset towards women, emphasised by these superficial and demeaning names. Stereotypes remain as apparent within society today as they were within the world of Rear Window and can be identified within the media’s diverse presentation of social issues. It is easy to assume that Hitchcock’s 1954 thriller, Rear Window , lacks the relevancy we expect from films. Contrary to this perception, its ingrained messages are fundamentally true to this day.

- Symbols and Analysis

- Discussion Questions

Sample Essay Topics

Go Went Gone revolves around an unlikely connection between a retired university professor , Richard, and a group of asylum seekers who come from all over the African continent . While he’s enjoyed a life of stability and privilege as a white male citizen, the lives of these asylum seekers could not be more different: no matter where they are in the world, uncertainty seems to follow. Richard initially sets out to learn their stories, but he is very quickly drawn into their histories of tragedy, as well as their dreams for the future.

However, the more he tries to help them, the more he realises what he’s up against: a potent mix of stringent legal bureaucracy and the ignorance of his peers . These obstacles are richly interwoven with the novel’s context in post-reunification Germany (more on this under Symbols: Borders ), but bureaucracy and ignorance are everywhere - Australia included . This novel, therefore, bears reflection on our own relationship with the refugees who seek protection and opportunity on our shores - refugees who are virtually imprisoned and cut off from the world .

Richard ultimately realises that these men are simply people , people who have the same complexities and inconsistencies as anyone else. They sometimes betray his trust; at other times, they help him in return despite their socio-economic standing. The end of the novel is thus neither perfect nor whole - while the asylum seekers develop a relationship with Richard and vice versa, neither is able to entirely solve the other’s problems, though both learn how to be there for each other in their own ways. We don’t get many solutions to everything the refugees are facing, but what we end up with is a lesson or two in human empathy.

The title of Jenny Erpenbeck’s novel Go Went Gone is a line she weaves into a couple of scenes. In one example, a group of asylum seekers in a repurposed nursing home learn to conjugate the verb in German. In another, a retired university professor reflects on this group, about to be relocated to another facility.

The various privileges Richard holds shape his identity in this text. It shapes how he approaches his retirement for example: now that “ he has time ”, he plans to spend it on highbrow pursuits like reading Proust and Dostoyevsky or listening to classical music. On the other hand, the asylum seekers sleep most of the time: “if you don’t sleep through half the morning, [a day] can be very long indeed.” Richard has the freedom to choose to spend his time on hobbies, but the asylum seekers face a daunting and seemingly-impossible array of tasks. After getting to know them more, he realises that while his to-do list includes menial things like “schedule repairman for dishwasher”, the refugees face daunting socio-political problems like needing to “eradicate corruption”.

Freedom in general is a useful way to think about privilege in this text, and besides freedom to choose how you spend your time, this can also look like the freedom to tell your story. While Richard helps the men with this to some degree, even he has a limited amount of power here (and power can be another useful way of thinking about privilege). Richard realises that “people with the freedom to choose…get to decide which stories to hold on to” - and those are the people who get to decide the future of the refugees, at least from a legal perspective.

Though Richard can’t necessarily help with these legal issues, he finds himself doing what he can for the refugees over time. He demonstrates a willingness to help them in quite substantial ways sometimes, for example buying a piece of land in Ghana for Karon and his family. In the end, we see him empathising with the refugees enough to offer them housing: though he is not a lawyer, he still finds ways to use his privilege for good and share what he can. He taps into his networks and finds housing for 147 refugees.

The tricky thing with empathy though is that it’s never one-sided, not in this book and not in real life either. It’s not simply a case of Richard taking pity on the refugees - we might think of this as sympathy rather than empathy - but he develops complex, reciprocal and ‘real’ friendships with all of them. This can challenge him, and us, and our assumptions about what is right. When Richard loses his wallet at the store, Rufu offers to pay for him. He initially insists he “can’t accept”, but when he does Rufu doesn’t let him pay him back in full. Erpenbeck challenges us to empathise without dehumanising, condescending or assuming anything in the process.

It’s an interesting way to think about social justice in general, particularly if you consider yourself an ‘ally’ of a marginalised group - how can we walk with people rather than speak for them and what they want?

Freedom of movement is sort of a form of privilege, but movement as a theme of its own is substantial enough to need a separate section. There are lots of different forms of movement in the novel, in particular movement between countries . In particular, it’s what brought the refugees to Germany at all, even though they didn’t necessarily have any control over that movement.

Contrast that with Richard’s friends, Jörg and Monika, who holiday in Italy and benefit from “freedom of movement [as] the right to travel”. Through this lens, we can see that this is really more of a luxury that the refugees simply do not have. Refugees experience something closer to forced displacement , rather than free travel, moving from one “temporary place” to the next often outside of their control. In this process, their lack of control often means they lose themselves in the rough-and-tumble of it all: “Becoming foreign. To yourself and others. So that’s what a transition looks like.”

3. Symbols & Analysis

Language and the law.

Many of the barriers faced by the refugees are reflected in their relationships with language; that is, their experiences learning German mirrors and sheds light on their relationship with other elements of German society. For example, there are times when they struggle to concentrate on learning: “It’s difficult to learn a language if you don’t know what it’s for”. This struggle reflects and symbolises the broader problems of uncertainty, unemployment and powerlessness in the men’s lives.

The symbol of language often intersects with the symbol of the “iron law”, so these are discussed together here. It’s hard on the one hand for these men to tell their stories in German, but it’s also hard for the German law to truly grapple with their stories. Indeed, Richard finds that the law doesn’t care if there are wars going on abroad or not: it only cares about “jurisdiction”, and about which country is technically responsible for the refugees. In this sense, the law mirrors and enables the callousness which runs through the halls of power - not to deter you from learning law if you want though! This might just be something to be aware of, and maybe something you’d want to change someday.

There’s one law mentioned in the novel stating that asylum seekers can simply be accepted “if a country, a government or a mayor so wishes”, but that one word in particular - “ if ” - puts all the power in lawyers and politicians who know the language and the law and how to navigate it all. These symbols thus reflect power and privilege.

Borders (+ Historical Context)

Throughout the novel, there’s a sense that borders between countries are somewhat arbitrary things. They can “suddenly become visible” and just as easily disappear; sometimes they’re easy to cross, sometimes they’re impossible to cross. Sometimes it’s easy physically, but harder in other ways - once you cross a border, you need housing, food, employment and so forth.

This complex understanding of borders draws on the history of Germany , and in particular of its capital Berlin, after World War II. After the war, Western powers (USA, UK, France) made a deal with the Soviet Union to each run half of Germany and half of Berlin. The Eastern half of Germany, and the Eastern half of Berlin, fell under Soviet control, and as East Germans started flocking to the West in search of better opportunities (sound familiar?), the Soviets built a wall around East Berlin. The Berlin Wall , built in 1961, became a border of its own, dividing a nation and a city and changing the citizenship of half of Germany overnight. Attempts to escape from the East continued for many years until the wall came down in 1989, changing all those citizenships right back, once again virtually overnight.

This history adds dimension to Erpenbeck’s novel. Refugees pass through many countries, but Erpenbeck draws on Germany’s history specifically as a once-divided nation itself. This helps to illustrate that national borders are just another arbitrary technicality that divides people, at the expense of these refugees.

Bodies of Water

One motif that comes back a few times in the novel is the drowned man in the lake by Richard’s house. This has a few layers of meaning.

Firstly, the man drowns despite the lake being a perfectly “placid” body of water, and for whatever reason, this bothers Richard immensely: “he can’t avoid seeing the lake”. There’s an interesting contrast here to be drawn between this one death in a still body of water and the hundreds of deaths at sea that are recounted in the novel. Rashid’s stories are particularly confronting: “Under the water I saw all the corpses”. Erpenbeck questions the limits of human empathy - whose deaths are we more affected by, and why - through contrasting these different bodies of water, and those who die within them. Richard is more affected than most, who visit the lake all summer leaving “just as happy as they came” - but even he has his limits with how much he can see and understand.

The next layer of meaning with this symbol then is more around the surface of the water itself: it is significant that in Rashid’s story, the casualties are below the surface. This reflects the common saying, “the tip of the iceberg” - the survivors who make it to Europe are really just the tip of the iceberg , only representing a fraction of the refugee experience. Often, that experience ends in death. Erpenbeck asks us to keep looking beneath the surface in order to empathise in full.

Music and the Piano

This symbol is specific to Richard’s relationship with Osarobo , to whom he teaches the piano. There’s one scene where this symbolism is particularly powerful, where they watch videos of pianists “us[ing] the black and white keys to tell stories that have nothing at all to do with the keys’ colours.”

It speaks to the power of music to bring people together, and also to the importance of storytelling in any form: Rosa Canales argues the keys’ colours, and the colour of the fingers playing them, “become irrelevant to the stories emanating from beneath them”.

- “What languages can you speak?”

- “The German language is my bridge into this country”

- “Empty phrases signify politeness in a language which neither of them is at home”

- “The things you’ve experienced become baggage you can’t get rid of, while others - people with the freedom to choose - get to decide which stories to hold on to”

- “He hears Apollo’s voice saying: They give us money, but what I really want is work. He hears Tristan’s voice saying: Poco lavoro . He hears the voice of Osaboro, the piano player, saying: Yes, I want to work but it is not allowed. The refugees’ protest has created half-time jobs for at least twelve Germans thus far”

- “Not so long ago, Richard thinks, this story of going abroad to find one's fortune was a German one”

- “Is it a rift between Black and White? Or Poor and Rich?”

- “Where can a person go when he doesn't know where to go?”

5. Discussion Questions

Here are some questions to think about before diving into essay-writing. There’s no right or wrong answer to any of these, and most will draw on your own experiences or reflections anyway. You may want to write some answers down, and brainstorm links between your responses and the novel. These reflections could be particularly useful if you’re writing a creative response to the text, but they’re also a really good way to get some personal perspective and apply the themes and lessons of this novel into your own life.

- Where do you ‘sit’ in the world? What privileges do you have or lack? What can you do that others cannot, and what can others do that you cannot?

- Think about the times you’ve travelled around the world - how many of those times were by choice? What might be the impact of moving across the world against your will?

- How do you show empathy to others? How do you receive empathy from others? What is that relationship ‘supposed’ to look like?

- What are some different names for where you live? How can you describe the same place in different languages or words? If you’re in Australia, what was your area called before 1788?

- Have you ever learned or spoken a language other than English? What language do you find easier to write, speak and think with? How might this impact someone’s ability to participate in different parts of life (school, work, friendships etc.)?

6. Sample Essay Topics

- Go Went Gone teaches us that anyone can be empathetic. Discuss.

- In Go Went Gone , Erpenbeck argues that storytelling can be powerful but only to an extent. Do you agree?

- How does Erpenbeck explore the different ways people see time?

- It’s possible to sympathise with Richard despite his relative privilege. Do you agree?

- Discuss the symbolic use of borders in Go Went Gone .

- Go Went Gone argues that the law is impartial. To what extent do you agree?

- “The German language is my bridge into this country.” How is language a privilege in Go Went Gone ?

- Who are the protagonists and antagonists of Go Went Gone ?

- Go Went Gone shows that it is impossible to truly understand another person’s experiences. To what extent do you agree?

In what ways do the people Richard meets challenge his assumptions about the world?

- Go Went Gone is less about borders between countries than it is about borders between people. Do you agree?

7. Essay Topic Breakdown

Whenever you get a new essay topic, you can use LSG’s THINK and EXECUTE strategy , a technique to help you write better VCE essays. This essay topic breakdown will focus on the THINK part of the strategy. If you’re unfamiliar with this strategy, then check it out in How To Write A Killer Text Response .

Within the THINK strategy, we have 3 steps, or ABC. These ABC components are:

Step 1: A nalyse

Step 2: B rainstorm

Step 3: C reate a Plan

This prompt alludes to certain assumptions that Richard might make about the world. If it’s hard to think of these off the top of your head, consider where our assumptions about the world come from: maybe from our jobs, our families and friends or our past experiences. Maybe there are some assumptions you’ve had in the past that you’ve since noticed or challenged.

Then it asks us how the people Richard meets challenges those assumptions. There’s no way to get out of this question without discussing the refugees, so this will inform our brainstorm.

I think some of Richard’s assumptions at the beginning come from his status: being a professor emeritus makes you pretty elite, and he can’t really empathise with the refugees because his experiences of life are so different. Part of the challenge with this prompt might be to break down what life experiences entail, and where those differences lie: particularly because it’s asking us ‘in what ways’. These experiences could be with language, employment, or personal relationships just to name a few ideas.

Because Richard’s life experiences are so vastly different, I’d contend that his assumptions are challenged in basically every way. However, I also think that his interest in the refugees exists because he knows they can challenge his assumptions. I want to use the motif of water surfaces to tie this argument together, particularly in the topic sentences, and this could look as follows:

Paragraph 1 : Richard realises that he only has a ‘surface-level’ appreciation of the refugees’ life experiences.

- He realises that he knows little about the African continent (“Nigeria has a coast?”)

- He suffers from a “poverty of experience” which means he hasn’t had to interact with this knowledge before

- His renaming of the refugees (Apollo, Tristan etc.) suggests that he still needs his own frame of reference to understand their experiences

- He learns about the hardships of migration through the tragic stories of those like Rashid

Paragraph 2 : He also realises that he has a ‘surface-level’ understanding of migration in general.

- This comes from the fact that he has never actually moved countries; he’s only been reclassified as an East German, and then again as a German. Neither happened because he wanted them to.

- On the other hand, the refugees want to settle in Europe: they want the right to work and make a living - it’s just that the “iron law” acts as a major barrier. Their powerlessness is different from Richard’s.

- Part of migration is also learning the language, and Richard is initially quite ignorant about this: he observes that the Ethiopian German teacher “for whatever reason speaks excellent German”, not realising this is necessary for any migrant to survive in the new country.

- We can think of this as the difference between migration and diaspora, the specific term for the dispersion of a people.

Paragraph 3 : Richard is more open than most people to looking beneath the surface though, meaning that his assumptions are challenged partly because he is willing for them to be.

- The symbol of the lake works well here to explain this: he is bothered by its still surface, and what lies underneath, while others aren’t

- We can also contrast this to characters like Monika and Jörg who remain quite ignorant the whole time: Richard’s views have departed from this throughout the course of the novel

- Ultimately, the novel is about visibility: Richard’s incorrect assumptions mean that he isn’t seeing reality, and his “research project” is all about making that reality visible.

Go Went Gone is usually studied in the Australian curriculum under Area of Study 1 - Text Response. For a detailed guide on Text Response, check out our Ultimate Guide to VCE Text Response .

Updated 19/01/2021

After Darkness is currently studied in VCE English under Area of Study 1 - Text Response. For a detailed guide on Text Response, check out our Ultimate Guide to VCE Text Response .

1. Introduction (Plot Summary) 2. Characters and Development 3. Themes 4. Narrative Conventions/Literary Devices 5. Sample Paragraphs 6. Additional Essay Prompts and Analysis Questions to Consider 7. Tips

1. Introduction (Plot Summary)

Christine Piper’s historical fiction, After Darkness deals with suppressed fragments of the past and silenced memories. The protagonist, Dr Ibaraki, attempts to move forward with life whilst also trying to hide past confrontations as well as any remnants of his past wrongdoings and memories. The text consists of three intertwined narrative strands – Ibaraki’s past in Tokyo in 1934, his arrival in Broome in 1938 to work in a hospital there, and his arrival in a detainment camp in Loveday (South Australia) in 1942 after the outbreak of war.

2. Characters and Development

.png)

4. Narrative Conventions/Literary Devices

- ‘a mallee tree’ - Aboriginal word for water which symbolises purity, source of life 'if it’s hit by bushfire it grows back from the root with lots of branches, like all the others here. It’s a tough tree. Drought, bushfire…it’ll survive almost anything…I was struck by the ingenuity of the tree in its ability to generate and create a new shape better suited to the environment.'

- The tag with 'the character ko…[with] its loop of yellowed string...The knot at the end had left an impression on the page behind it: a small indentation, like a scar.'

Simile/Imagery:

- 'Felt like hell on earth'

- 'The hollow trunks of dead trees haunted its edges like lost people' - Can also link to the landscape narrative convention

- 'The scene was like a photograph, preserving the strangeness of the moment.'

Description of the hospital atmosphere where the patient next to Hayashi laid

- 'Only the windows were missing, leaving dark holes like the eyes of an empty soul'

- 'The photos reached me first. I leafed through the black and white images: swollen fingers, blistered toes, blackened faces, and grotesque, rotting flesh that shrivelled and puckered to reveal bone. The final photo depicted a child’s chubby hands, the tips of the fingers all black.' - Also foreshadowing death of his and Kayoko’s child

Pathetic Fallacy:

- 'That afternoon, the sky darkened, and the wind picked up…making the world outside opaque.'

- Middlemarch (book) which symbolises Ibaraki and Sister Bernice’s friendship as Bernice was left behind

- Robinson Crusoe

- 'Being able to conduct research in this way has delivered unparalleled knowledge, which we’ve already passed on to the army to minimise further loss of life.'

- 'You haafu fools don’t deserve the Japanese blood in you!'

- 'You bloody racist!'

- 'You fucking Emperor-worshipping pig...!'

- 'Haafu' - Derogatory, racism term used to define those who are biracial (half Japanese):

An interpretation of the language use throughout the text could be Piper’s way of humanising the Japanese people to her readers and notifying them that they also have their own culture and form of communication

Another interpretation of the language use is to show that both the Australians and Japanese are just as cruel as each other because they show no respect to one another and use language in such a brutal way

Ibaraki represents that divide where he can speak both languages, yet still, cannot voice his own opinion or stand up for himself (link to theme of silence)

Personification:

- 'The void seemed to have a force of its own, drawing the meaning of the words into it.'

- 'The engine coughed into life.'

Foreshadowing:

- 'snow was falling as I walked home from the station – the first snow of the season.' - Foreshadowing the storm about to come in his life

- 'A black silhouette against the fallen snow.' - Foreshadowing Kayoko’s death

5. Sample Paragraphs

'But as soon as you show a part of yourself, almost at once you hide it away.' Ibaraki’s deepest flaw in After Darkness is his failure to reveal himself. Do you agree?

- Introduction

Christine Piper’s historical fiction, After Darkness explores the consequences that an individual will be forced to endure when they choose to conceal the truth from their loved ones. Piper reveals that when a person fails to reveal themselves, it can eventually become a great obstacle which keeps them from creating meaningful and successful relationships. Additionally, Piper asserts that it can be difficult for an individual to confront their past and move completely forward with their present, especially if they believed their actions were morally wrong. Furthermore, Piper highlights the importance of allowing people into one’s life as a means to eliminate the build-up the feelings of shame and guilt.

Body Paragraph

Piper acknowledges that some people will find it difficult to open up to others about their past due to them accumulating a large amount of regret and guilt over time. This is the case for Ibaraki as he was involved with the ‘experiments’ when he was working in the ‘Epidemic Prevention Laboratory', in which Major Kimura sternly told him to practise ‘discretion and not talk ‘about [his] work to anybody'. The inability to confide in his wife or mother after performing illegal and mentally disturbing actions causes him to possess a brusque conduct towards others, afraid that they will discover his truth and ‘not be able to look at [him] at all'. His failure to confess his past wrongdoings shapes the majority of his life, ruining his marriage and making him feel the need ‘to escape’ from his losses and ‘start afresh'. He eventually lies to his mother by making her believe that he ‘had gone to Kayoko’s parents’ house’ for the break, avoiding any questions from being raised about his job. As a consequence, he fails to tell his family about his horrid past suggesting that he has accepted that ‘[his] life had become one that others whispered about'. Juxtaposed to Ibaraki’s stress relieving methods, Kayoko confides in her mother after she receives news of her miscarriage, highlighting that when one willingly shares their pain with loved ones, it can release the burden as well as provide them with some assistance. In contrast to this, Ibaraki’s guilty conscience indicates that he will take ‘the secret to his grave', making it extremely difficult for people he encounters to understand him and form a meaningful connection with him. Nonetheless, Piper does not place blame on Ibaraki as he was ordered to keep the ‘specimen’ business hidden from society, thereby inviting her readers to keep in mind that some individuals are forced by others to not reveal their true colours for fear of ruining a specific reputation.

Throughout the journey in After Darkness , Piper engendered that remaining silent about one’s past events that shapes their future is one of the deepest flaws. She notes that for people to understand and form bonds with one another, it is extremely important to reveal their identity as masking it only arises suspicions. Piper postulates that for some, memories are nostalgic; whereas, for others it carries an unrelenting burden of guilt, forcing them to hide themselves which ultimately becomes the reason as to why they feel alone in their life.

6. Additional Essay Prompts and Analysis Questions to Consider

- Analyse the role of silence in After Darkness . Compare the ways in which the characters in the text utilise or handle silence. What is Piper suggesting about the notion of silence?

- Discuss the importance of friendship in the text. What is it about friends that make the characters appear more human? How can friendship bolster development in one’s character?

- Racism and nationalism are prominent themes in the text. How are the two interlinked? Explore the ways they are shown throughout the text and by different characters. Is Piper indicating that the two always lead to negative consequences?

- Analyse some of the narrative conventions (imagery, simile, metaphor, symbols, motifs, landscapes, language, etc.) in the novel and what they mean to certain characters and to the readers.

- Explore the ways in which the text emphasises that personal conscience can oftentimes hold people back from revealing their true thoughts and feelings.

- Character transformation (bildungsroman) is prevalent throughout the text. What is Piper suggesting through Ibaraki’s character in terms of the friendships and acquaintances he has formed and how have they impacted him? How have these relationships shaped him as a person in the past and present? Were such traits he developed over time beneficial for himself and those around him or have they caused the destruction of once healthy relationships?

If you'd like to see how to break down an essay topic, you might like to check out our After Darkness Essay Topic Breakdown blog post!

- Be sure to read as many academic articles as you can find in relation to the text in order to assist you with in-depth analysis when writing your essays. This will help you to stand out from the crowd and place you in a higher standing compared to your classmates as your ideas will appear much more sophisticated and thought-out.

- Being clear and concise with the language choices is such a crucial factor. Don’t over complicate the ideas you are trying to get across to your examiners by incorporating ‘big words’ you believe will make your writing appear of higher quality, because in most cases, it does the exact opposite (see Why Using Big Words in VCE Essays Can Make You Look Dumber ). Be careful! If it's a choice between using simpler language that your examiners will understand vs. using more complex vocabulary where it becomes difficult for the examiners to understand what you're trying to say, the first option is best! Ideally though, you want to find a balance between the two - a clearly written, easy to understand essay with more complex vocabulary and language woven into it.

- If there is a quote in the prompt, be sure to embed the quote into the analysis, rather than making the quote its own sentence. You only need to mention this quote once in the entire essay. How To Embed Quotes in Your Essay Like a Boss has everything you need to know for this!

If you'd like to see sample A+ essays complete with annotations on HOW and WHY the essays achieved A+, then you'll definitely want to check out our After Darkness Study Guide ! In it, we also cover advanced discussions on topics like structural features and context, completely broken down into easy-to-understand concepts so you can smash your next SAC or exam! Check it out here .

MAIN CHARACTERS

Margo Channing played by Bette Davis

As the protagonist of the movie, Margo Channing is a genuine and real actress raised by the theatre since the age of three. She is a vulnerable character who openly displays her strengths and weaknesses; Mankiewicz showcasing the life of a true actress through her. Initially, we see Margo as mercurial and witty, an actress with passion and desire (not motivated by fame but the true art of performing). She is the lead in successful plays and with friends like Karen and Lloyd to rely on and a loving partner, Bill, it seems that she has everything.

However, Margo’s insecurities haunt her; with growing concerns towards her identity, longevity in the theatre and most importantly her relationship with Bill. Eventually, in a pivotal monologue, Margo discusses the problems that have been plaguing her. She battles with the idea of reaching the end of her trajectory, the thought that ‘in ten years from now – Margo Channing will have ceased to exist. And what’s left will be… what?’ By the end of the movie, Margo accepts the conclusion of her time in the theatre and understands that family and friends are what matters most, not the fame and success that come with being an acclaimed actress.

Eve Harrington played by Anne Baxter

Antagonist of All About Eve , Eve Harrington (later known as Gertrude Slojinski) is an egotistical and ambitious theatre rookie. With a ‘do-whatever-it-takes’ attitude, Eve is first introduced to the audience as a timid and mousy fan (one with utmost dedication and devotion to Margo). However, as the plot unfolds, Eve’s motive becomes increasingly clear and her actions can be labelled as amoral and cynical, as she uses the people around her to climb the ladder to fame.

Margo is her idealised object of desire and from the subtle imitations of her actions to infiltrating and betraying her close circle of friends, Eve ultimately comes out from the darkness that she was found in and takes Margo’s place in the theatre. Mankiewicz uses Eve’s character to portray the shallow and back-stabbing nature of celebrity culture; Eve’s betrayal extending beyond people as she eventually turns her back on the world of theatre, leaving Broadway for the flashing lights of Hollywood.

Addison DeWitt played by George Sanders

The voice that first introduces the audience to the theatre, Addison DeWitt is a cynical and manipulative theatre critic. Despite being ambitious and acid-tongued, forming a controlling alliance with Eve, Addison is not the villain.

The critic is the mediator and forms a bridge between the audience, the theatre world, and us; he explains cultural codes and conventions whilst also being explicitly in charge of what we see. Ultimately, Addison is ‘essential to the theatre’ and a commentator who makes or breaks careers.

Bill Simpson played by Gary Merill

Bill Simpson is the director All About Eve does not focus on Bill’s professional work but rather places emphasis on his relationship with Margo. He is completely and utterly devoted to her and this is evident when he rejects Eve during an intimate encounter. Despite having a tumultuous relationship with Margo, Bill proves to be the rock; always remaining unchanged in how he feels towards her.

Karen Richards played by Celeste Holmes

Wife of Lloyd Richards and best friend and confidante to Margo Channing, Karen Richards is a character who supports those around her. During conversations she listens and shares her genuine advice, acting as a conciliator for her egocentric friends. Unfortunately, Karen is also betrayed by Eve, used as a stepping stone in her devious journey to fame.

Lloyd Richards played by Hugh Marlowe

Successful playwright and husband to Karen Richards, Lloyd Richards writes the plays that Margo makes so successful. However, as Margo grows older in age, she begins to become irrelevant to the plays that Lloyd writes. Subsequently, this causes friction between the two characters and Mankiewicz uses this to show the audience the struggles of being an actress in the theatre; whilst also adding to the Margo’s growing concern towards her age.

Lloyd is unwilling to change the part for Margo and thus Eve becomes a more attractive match for the part. An unconfirmed romance between the budding actress and Lloyd also adds to the drama within All About Eve .

MINOR CHARACTERS

Birdie played by Thelma Ritter

A former vaudeville actress (which means that she acted in comic stage play which included song and dance), Margo’s dresser and close friend, Birdie is not afraid to speak the truth. Initially she sees right through Eve’s story and she warns Margo to watch her back. Despite not being in much of the movie, Birdie’s critical eye is a foreshadowing for the audience towards what is to come.

Max Fabian played by Gregory Ratoff

Producer in the theatre, Max Fabian is involved in theatre just to ‘make a buck’. He is a hearty character who adds comic relief to a dramatic plot.

Miss Claudia Caswell played by Marilyn Monroe

Aspiring actress, Miss Caswell is seen briefly throughout the movie to show the audience the shallow nature of the world of show business. Unlike Eve, she relies on her appearance to ‘make’ it rather than talent; as seen during her encounter with Max and the unsuccessful audition that followed.

Phoebe played by Barbara Bates

The next rising star to follow in Eve’s footsteps, Phoebe is featured at the end of the film. In this scene there is a foreshadowing of the future, which suggests a repeat of the past, thus, making Phoebe an interesting character to observe. She is a manufactured construction of an actress and illustrates how replaceable a character is in the world of theatre.

The Complete Maus by Art Spiegelman is usually studied in the Australian curriculum under Area of Study 1 - Text Response. For a detailed guide on Text Response, check out our Ultimate Guide to VCE Text Response .

- Analysing Techniques in Visual Texts

1. Introduction

The Complete Maus is a graphic novel that depicts the story of Vladek Spiegelman , a Polish Jewish Holocaust survivor who experienced living in the ghettos and concentration camps during the Nazi regime. Vladek’s son, Art has transformed his story into a comic book through his interviews and encounters which interweaves with Art’s own struggles as the son of a Holocaust survivor, as well as the complex and difficult relationship with his father.

Survival is a key theme that is explored during Vladek’s experience in concentration camps and his post-Holocaust life.

For example, Vladek reflects that “You have to struggle for life” and a means of survival was through learning to be resourceful at the concentration camps.

.png)

Resourcefulness is depicted through the physical items Vladek keeps or acquires, as well as through Vladek’s skills . For example, Vladek explains to Art that he was able to exploit his work constantly through undertaking the roles of a translator and a shoemaker in order to access extra food and clothing by being specially treated by the Polish Kapo .

%20(1)%20(1)%20(1).png)

He even wins over Anja’s Kapo to ensure that she would be treated well by not being forced to carry heavy objects. Vladek’s constant recounts and reflections symbolise survival, as Vladek was willing and able to use his skill set to navigate through the camp’s work system.

%20(1)%20(1)%20(1).png)

During the concentration camps, food and clothes also became a currency due to its scarcity and Vladek was insistent on being frugal and resourceful , which meant that he was able to buy Anja’s release from the Birkenau camp.

%20(1)%20(1)%20(1).png)

Although survival is a key theme, the graphic novel explores how Holocaust survivors in The Complete Maus grapple with their deep psychological scars.

%20(1)%20(1).png)

Many of those who survived the war suffered from depression and was burdened with ‘survivor’s guilt’. This can be seen through the character of Art’s mother, Anja, as 20 years after surviving the death camps, she commits suicide. After having lost so many of her friends, and families, she struggled to find a reason as to why she survived but others didn’t. Throughout the graphic novel, her depression is apparent. In a close-up shot, Anja appears harrowed and says that “I just don’t want to live”, lying on a striped sofa to convey a feeling of hopelessness as if she was in prison. Her ears are additionally drawn as drooped, with her hands positioned as if she was in prison in the context is that she must go to a sanatorium for her depression.

%20(1)%20(1)%20(1).png)

It is not only Anja’s guilt that is depicted, but also Art himself who feels partly responsible. Art feels that people think it is his fault as he says that “They think it’s MY fault!” and in one panel, Art is depicted behind bars and that “[He] has committed the perfect crime“ to illustrate that he feels a sense of guilt in that he never really was the perfect son. He believes he is partly responsible for her death, due to him neglecting their relationship. Spiegelman also gives insight to readers of a memory of his mother where she asks if he still loves her, he responds with a dismissive ‘sure’ which is a painful reminder of this disregard.

Intergenerational Gap

Art constantly ponders how he is supposed to “make any sense out of Auschwitz’ if he “can’t even make any sense out of [his] relationship with [his] father”. As a child of Jewish refugees, Art has not had the same first-hand horrific experiences as his parents and in many instances struggles to relate to Vladek’s stubborn and resourceful tendencies. Art reflects on this whilst talking to Mala about when he would not finish everything his mother served, he would “argue til I ran to my room crying”. This emphasises how he didn’t understand wastage or frugality even from a very young age, unlike Vladek.

.png)

Spiegelman also conveys to readers his sense of frustration with Vladek where he feels like he is being treated like a child, not as an adult. For example, Art is shocked that Vladek would throw out one of Art’s coats and instead buy a new coat, despite Vladek’s hoarding because he is reluctant and feels shameful to let his son wear his “old shabby coat”. This act could be conveyed to readers that Vladek is trying to give Art a life he never had and is reluctant to let his son wear clothes that are ‘inappropriate’ in his eyes. However, from Art’s perspective, he “just can’t believe it” and does not comprehend his behaviour.

Since we're talking about themes, we've broken down a theme-based essay prompt (one of five types of essay prompts ) for you in this video:

3. Analysing Techniques in Visual Texts

The Complete Maus is a graphic novel that may seem daunting to analyse compared to a traditional novel. However, with countless panels throughout the book, you have the freedom to interpret certain visuals so long as you give reasoning and justification, guiding the teacher or examiner on what you think these visuals mean. Here are some suggested tips:

Focus on the Depiction of Characters

%20(1).png)

Spiegelman may have purposely drawn the eyes of the Jewish mice as visible in contrast to the unapparent eyes of the Nazis to humanise and dehumanise characters. By allowing readers to see the eyes of Jewish mice, readers can see the expressions and feelings of the character such as anger and determination . Effectively, we can see them as human characters through their eyes. The Nazis’ eyes, on the other hand, are shaded by their helmets to signify how their humanity has been corrupted by the role they fulfill in the Holocaust.

%20(1).png)

When the readers see their eyes, they appear sinister , with little slits of light. By analysing the depictions and expressions of characters, readers can deduce how these characters are intended to be seen.

Look at the Background in Each Panel

Throughout the graphic novel, symbols of the Holocaust appear consistently in the background. In one panel, Art’s parents, Anja and Vladek have nowhere to go, a large Swastika looms over them to represent that their lives were dominated by the Holocaust.

%20(1).png)

Even in Art’s life, a panel depicts him as working on his desk with dead bodies surrounding him and piling up to convey to the reader that the Holocaust still haunts him to this day, and feels a sense of guilt at achieving fame and success at their expense.

%20(1)%20(1)%20(1)%20(1).png)

Thus, the constant representation of symbols from the Holocaust in Spiegelman’s life and his parents’ past in the panels’ background highlights how inescapable the Holocaust is emotionally and psychologically .

Size of Panels

.png)

Some of the panels in the graphic novel are of different sizes which Spiegelman may have intended to emphasise the significance of certain turning points, crises or feelings . For example, on page 34, there is a disproportionate panel of Vladek and Anja passing a town, seeing the first signs of the Nazi regime compared to the following panels. All the mice seem curious and concerned, peering at the Nazi flag behind them. This panel is significant as it marks the beginning of a tragic regime that would dominate for the rest of their lives.

You should also pay close attention to how some panels have a tendency to overlap with each other which could suggest a link between events, words or feelings.

Although not specifically targeted at Text Response, 10 Things to Look for in Cartoons is definitely worth a read for any student studying a graphic novel!

[Video Transcript]